Abstract

Introduction

The adaptation of guidelines is an increasingly used methodology for the efficient development of contextualised recommendations. Nevertheless, there is no specific reporting guidance. The essential Reporting Items of Practice Guidelines in Healthcare (RIGHT) statement could be useful for reporting adapted guidelines, but it does not address all the important aspects of the adaptation process. The objective of our project is to develop an extension of the RIGHT statement for the reporting of adapted guidelines (RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist).

Methods and analysis

To develop the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist, we will use a multistep process that includes: (1) establishment of a Working Group; (2) generation of an initial checklist based on the RIGHT statement; (3) optimisation of the checklist (an initial assessment of adapted guidelines, semistructured interviews, a Delphi consensus survey, an external review by guideline developers and users and a final assessment of adapted guidelines); and (4) approval of the final checklist. At each step of the process, we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions, use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions, discuss the results, draft a report and refine the checklist.

Ethics and dissemination

We have obtained a waiver of approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). We will disseminate the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist by publishing into a peer-reviewed journal, presenting to relevant stakeholders and translating into different languages. We will continuously seek feedback from stakeholders, surveil new relevant evidence and, if necessary, update the checklist.

Keywords: Evidence-based medicine, guideline adaptation, guidelines as topic, practice guideline, quality, reporting standards

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There is no current tool for reporting adapted guidelines. The extension of the RIGHT statement for adapted practice guidelines (RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist) will fill this gap and provide a clear guidance for the reporting of guideline adaptation.

To develop the checklist, we will use the best available methodological research evidence, adopt a systematic and rigorous multistep process and collect and build on the views and experiences of international stakeholders including guideline methodologists, policymakers, journal editors and guideline users.

The RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist can be used within guideline adaptation to guide reporting, to improve the completeness of reporting, to evaluate publications and to inform implementation decisions of healthcare.

We will not conduct a complete formal validation of the checklist since our current process will not include an assessment of neither construction nor criterion validity.

Introduction

The WHO defines guidelines as ‘systematically developed evidence-based statements which assist providers, recipients and other stakeholders to make informed decisions about appropriate health interventions.’ Guidelines have been increasingly used to provide guidance for policies or public health interventions, changes in resource availability or access to services based on evidence.1 There is evidence that the methodological quality of guidelines has slowly improved over the last decades.2–4 However, most guideline developers do not have enough resources for developing high-quality de novo guidelines.5 Most low/middle-income countries still do not have formal organisations, technical capacity or collaborations to develop evidence-based guidelines.6 When guidelines are developed in those settings, their quality is typically poor.7–13 Adapting published high-quality evidence-informed guidelines becomes a more efficient option.14–16

Adaption of guidelines means the use of existing trustworthy guidelines, with (adapt) or without (adopt) modifications, to provide local, regional or national guidance.15–17 Schünemann et al defined adapted recommendations as recommendations with: (1) potential change in the specific population, intervention, or comparator with respect to the original recommendations; (2) potential change in the certainty of the evidence; and (3) information on ‘conditions’, monitoring, implementation and implications for research.16 Adopted recommendations were defined as recommendations with: (1) the same specific population, intervention and comparators as the original recommendations; (2) the same certainty of the evidence; and (3) information on implementation.16 Adaptation of guidelines is an increasingly used methodology for the efficient development of contextualised recommendations that are relevant for diverse health systems.16–18 Guideline adaptation takes into consideration local contextual factors such as language, availability and accessibility of services and resources, the healthcare setting and the relevant stakeholders’ cultural and ethical values.19 At the same time, it should be based on similar systematic and transparent approaches as the source guideline in order to benefit from its quality and validity.20 However, adaptation is not always possible. For example, when a trustworthy guideline is not available, a de novo guideline development process needs to be considered.16 21

Despite the increasing need, there is no standard adaptation method implemented internationally.21 22 A systematic review of the literature identified eight published frameworks for adaptation of clinical, public health or health system guidelines, concluding that the ‘adaptation’ phases of the processes were notably different.23 Moreover, the process for adapting guidelines was usually poorly reported, including WHO guidelines.24 For example, Godah et al systematically assessed the processes employed in the adaptation of WHO guidelines for HIV and tuberculosis. Out of 170 eligible adapted guidelines, only 32 (32/170, 19%) reported the methods used in the adaptation process.24 Similarly, Abdul-Khalek et al assessed the methods used for adapting health-related guidelines published in peer-reviewed journals.25 Out of the 72 included adapted guidelines, 57 reported some degree of detail about the adaptation method used, and only 23 (23/57, 40%) reported using a specific adaptation method. These findings call for a need to optimise the methods used in guideline adaptation, and to improve the reporting of the adaptation process in adapted guidelines.24

Guidelines for reporting health research have been developed to enhance the accurate, complete and transparent reporting of health research publications (http://www.equator-network.org/). Moher et al defined a reporting guideline as ‘a checklist, flow diagram, or explicit text to guide authors in reporting a specific type of research, developed using explicit methodology.’26 Its aim is to indicate the minimum reporting standards, for readers to comprehend the design, conduct, analysis and interpretation of a study, and to assess the validity of results.26 27 A transparent reporting approach could help guideline developers frame the decision-making during the development process, and guideline users about the suitability for adapting, and consequently the adaptation process.

Currently, the main tools available for the reporting of guidelines development are: (1) the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument, including the AGREE Reporting Checklist28; and (2) the Reporting Items of Practice Guidelines in Healthcare (RIGHT) statement to improve the reporting of guidelines.29 The RIGHT statement was formally developed as a reporting checklist for de novo guidelines.29 Although it could be useful for the reporting of adapted guidelines,30 it does not cover some of the steps that are specific to guidelines adaptation (eg, description of methods used to search and identify guidelines).29 Therefore, to ensure rigour, transparency, clarity and reproducibility of reporting the adaptation process, we will develop an extension of the RIGHT statement for the reporting of adapted guidelines.

Objective

To develop the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist as an extension of the RIGHT statement tailored to adapted guidelines.

Methods and analysis

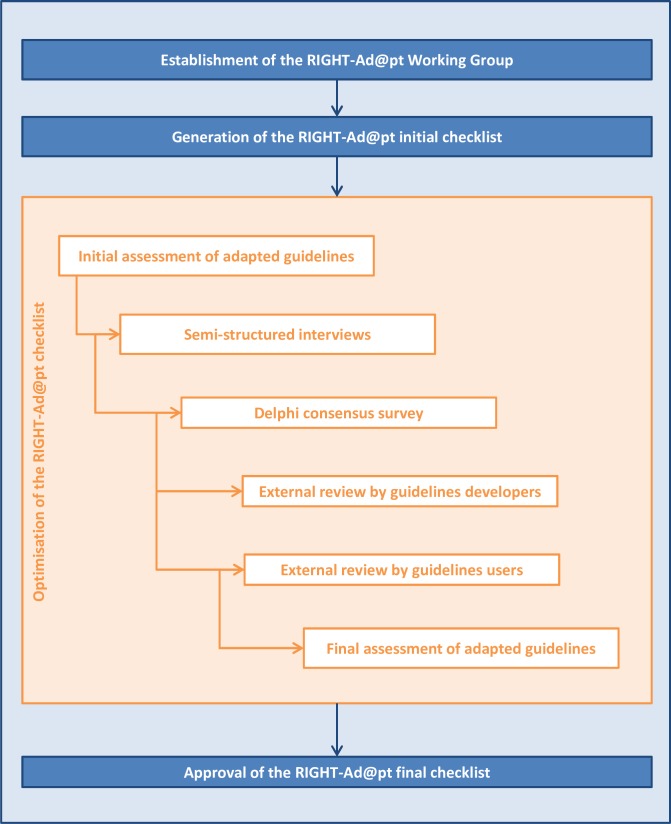

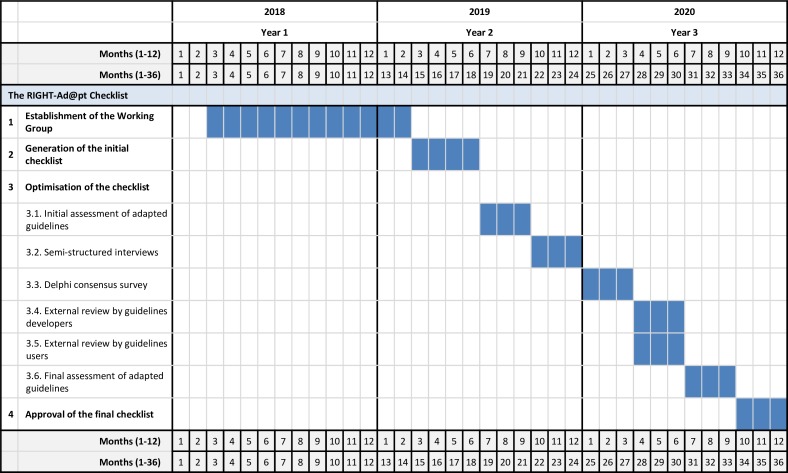

To develop the checklist, we will build on the RIGHT statement,29 review methodology research evidence on guidelines adaptation23–25 and adopt a multistep process we have successfully implemented in the development of similar tools.31 32 Table 1 describes the multistep development process of the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist, which includes: (1) establishment of a Working Group; (2) generation of an initial checklist; (3) optimisation of the checklist (an initial assessment of adapted guidelines, semistructured interviews, a Delphi consensus survey, an external review by guideline developers and users and a final assessment of adapted guidelines); and (4) approval of the final checklist. Figure 1 illustrates the development process, and figure 2 presents the timeline.

Table 1.

Description of the multistep development process

| Establishment of the Working Group | Generation of the initial checklist | Optimisation of the checklist | Approval of the final checklist | ||||||

| Initial assessment of adapted guidelines | Semistructured interviews | Delphi consensus survey | External review by guideline developers | External review by guideline users | Final assessment of adapted guidelines | ||||

| Main objective | To identify individuals who are relevant to participate in the project | To develop the initial version of the checklist | To assess the adequacy of each item of the checklist | To explore current practices in adaptation of guidelines | To define the list of items to be included in the checklist | To assess the usefulness of each item of the checklist | To assess the usefulness of each item of the checklist | To assess the adequacy of each item of the checklist | To approve the final version of the checklist |

| Study design | – | – | Methodological survey of adapted guidelines | Semistructured interviews | Delphi consensus survey | Survey | Semistructured interviews | Methodological survey of adapted guidelines | – |

| Participants |

|

|

Coordination Team (two reviewers) | Guideline developers | Delphi Panel Members | Guideline developers | Guideline users | Coordination Team (two reviewers) |

|

| Main outcome | – | – | Applicability rating of each item of the checklist | Participants’ views and experiences with process for adapting guidelines | Items considered relevant to report the adaptation of guidelines | Usefulness rating of each item of the checklist | Participants’ views and experiences with the checklist | Applicability rating of each item of the checklist | – |

| Study size | Convenience sample | – | Convenience sample of 10 adapted guidelines | Sampling saturation | 20–30 participants from GIN Adaptation Guidelines Working Group, WHO and authors of adapted guidelines | GIN community | Sampling saturation | Convenience sample of 10 adapted guidelines | – |

GIN, Guidelines International Network.

Figure 1.

Multistep development process of RIGHT-Ad@pt. RIGHT, Reporting Items of Practice Guidelines in Healthcare.

Figure 2.

Timeline of RIGHT-Ad@pt. RIGHT, Reporting Items of Practice Guidelines in Healthcare.

Establishment of the RIGHT-Ad@pt Working Group

The RIGHT-Ad@pt Working Group will include: (1) a Coordination Team; (2) an Advisory Group; and (3) a Delphi Panel.26 31 32

Coordination Team

The Coordination Team (YS, MB, LMG, PAC, EAA) will lead and coordinate the RIGHT-Ad@pt development process and ensure its completion according to the established timeline. Specifically, the Coordination Team will be responsible for (1) generating the initial version of the checklist; (2) implementing each step of the process; and (3) reporting the findings of each step of the processes. We have collected the conflicts of interests (CoI) of all members of the Coordination Team (online supplementary file 1).

bmjopen-2019-031767supp001.pdf (57.3KB, pdf)

Advisory Group

The Advisory Group is a multidisciplinary group (8–10 people) including (1) guideline methodological experts (defined as having experience and expertise in guideline methods); (2) guideline developers (defined as having participated in guideline development groups and/or guideline adaptation groups at least once in the past year); (3) guideline users (defined as healthcare professionals that use guidelines on a regular basis); and (4) journal editors of guideline-related journals.26 Members of the Advisory Group will review and provide expert advice during the different steps of the RIGHT-Ad@pt development process. The Advisory Group will approve the final checklist and accompanying guidance. We have collected the CoIs of all members of the Advisory Group (online supplementary file 1).

Delphi Panel

The Delphi Panel will be comprising 20–30 members, with profiles similar to those of the members of the Advisory Group (guideline methodological experts, guideline developers, guideline users and journal editors of guideline-related journals).33 34 We will aim for country income, gender and profile representativeness of participants. We will identify participants from the Guidelines International Network (GIN) Adaptation Guidelines Working Group (http://www.g-i-n.net/working-groups/adaptation), WHO, authors of adapted guidelines25 and expert colleagues. The panel’s CoIs will be collected.

Generation of the initial checklist

The Coordination Team will generate the initial version of the checklist building on the RIGHT statement.29 We will conduct this step via monthly face-to-face and online meetings within the Coordination Team. The Coordination Team will review the results, draft a report with a proposal of the initial version for the Advisory Group to review and produce a final version taken into consideration their feedback.

Optimisation of the checklist

Initial assessment of adapted guidelines

We will survey published adapted guidelines using initial checklist. We will explore the adequacy of each item (defined as overall completeness of reporting as well as the quantity of example supporting the item35), and refine the checklist. We will also record the main characteristics of the adapted guidelines (eg, title, year or adaptation process), completeness of reporting process for adapting guidelines and suggestions to improve the checklist (table 2).

Table 2.

Research design steps relevant to the optimisation of the checklist and corresponding variables

| Initial assessment of adapted guidelines | Semistructured interviews | Delphi consensus survey | External review | Final assessment of adapted guidelines | ||

| Guideline developers | Guideline users | |||||

| Response rate | X | X | ||||

| Characteristics of participants and workplaces | X | X | X | X | ||

| Characteristics of adapted guidelines | X | X | ||||

| Completeness of reporting | X | X | ||||

| Participants’ views and experiences | XX | XX | ||||

| Assessment of each item | XX (adequacy and suggestions) |

X (understanding and suggestions) |

XX (inclusion, understanding and suggestions) |

XX (usefulness, understanding and suggestions) |

X (understanding and suggestions) |

XX (adequacy and suggestions) |

| Overall assessment of the checklist | X | X | X | X | ||

XX: main outcome; X: other outcomes.

We will assess a convenience sample of 10 adapted guidelines available in English and published in the last 5 years.36 We will also take into account country income level, type of organisation and region. Two reviewers from the Coordination Team will independently apply the initial version of the checklist to adapted guidelines. The two reviewers will resolve potential disagreements by discussion, and if necessary, by consulting a third reviewer.

For quantitative variables (characteristics of adapted guidelines, completeness of reporting and adequacy), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative variables (suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.36 The Coordination Team will review the results, draft a report, review and agree on the relevant checklist modifications. If members of the Coordination Team do not reach consensus on specific items, they will consult the Advisory Group.

Semistructured interviews

We will survey guideline developers who were involved in guideline adaptation over the past 3 years. We will explore participants’ views and experiences on guidelines adaptation, and refine the checklist. We will also record the characteristics of participants and their workplaces, participants’ understanding of each item, suggestions to improve the checklist and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist (table 2). Each interview will last approximately 1 hour and will be recorded and transcribed with participant’s permission. The interview transcripts will be sent to interviewees for approval.

We will identify the participants with the support of the Advisory Group. We will contact via email and conduct online interviews. We will continue recruitment and collect data until information becomes repetitive and no new information emerges (sampling saturation).37 38

For quantitative variables (characteristics of participants and workplaces, participants’ understanding of each item and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative variables (participants’ views and experiences, and suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.39 The Coordination Team will review the results, draft a report, review and agree on the relevant checklist modifications. If members of the Coordination Team do not reach consensus on specific items, they will consult the Advisory Group.

Delphi consensus survey

We will conduct a Delphi consensus survey to reach a consensus with the Delphi Panel about the included items in the checklist. We will also record response rate, characteristics of participants and workplaces, participants’ understanding of each item, suggestions to improve the checklist and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist (table 2).

Before the first Delphi round, we will provide the Delphi Panel Members with a brief background material on the topic. In the first Delphi round, we will ask participants to rate whether each item should be included in the checklist using a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree and 7=strongly agree).31 32 40 We will calculate the median score for inclusion of each item and will classify them as (1) excluded (median score of 1–3 points); (2) review, modify and retest (median score of 4–5 points or with substantial comments); and (3) included (median score of 6–7 points and without substantial comments).31 32 After each Delphi round, we will provide feedback to Delphi Panel Members (data reported will be anonymised). We will conduct additional Delphi rounds until consensus regarding items inclusion is reached (median score of 6–7) and no more relevant comments on the items are provided (two or three rounds, as needed). We will use online software to design the survey and collect responses (http://www.clinapsis.com/). We will not invite non-responders or partial responders (questionnaires with no response for more than 20% of the items) to subsequent Delphi rounds.

For quantitative variables (response rate, characteristics of participants and workplaces, inclusion score, participants’ understanding of each item and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative data (suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.39 We will not consider questionnaires with no response for more than 20% of the items. The Coordination Team will review the results of the Delphi consensus survey, draft a report with a proposal for the Advisory Group to review and produce a final version taken into consideration their feedback.

External review

External review by guideline developers

We will survey guideline developers who were involved in guideline adaptation over the past 3 years. We will explore usefulness of each item (defined as provision of enough and clear information in order to be used with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction to check the reporting of adapted guidelines41) using a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree and 7=strongly agree),40 and refine the checklist. We will also record response rate, characteristics of participants and workplaces, participants’ understanding of each item, suggestions to improve the checklist and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist (table 2).

We will identify participants by contacting professionals associated with the GIN community (http://www.g-i-n.net) and WHO. We will use online software to design the survey and collect responses (http://www.clinapsis.com/).

For quantitative variables (response rate, characteristics of participants and workplaces, usefulness score, participants’ understanding of each item and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative data (suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.39 We will not consider questionnaires with no response for more than 20% of the items.

External review by guideline users

We will conduct external review semistructured interviews with guideline users who have used adapted guidelines over the past 3 years. We will explore participants’ views and experiences using the checklist, and refine the checklist. We will also record the characteristics of participants and workplaces, participants’ understanding of each item, suggestions to improve the checklist and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist (table 2). Each interview will last approximately 1 hour and will be recorded and transcribed with participant’s permission. The interview transcripts will be sent to interviewees for approval.

We will identify the participants with the support of the Advisory Group. We will contact via email and conduct online interviews. We will continue recruitment and collect data until information becomes repetitive and no new information emerges (sampling saturation).37 38

For quantitative variables (characteristics of participants and workplaces, usefulness score, participants’ understanding of each item and participants’ overall assessment of the checklist), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative data (participants’ views and experiences, and suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.39 The Coordination Team will review the results of the external review (guideline developers and users), draft a report with a proposal for the Advisory Group to review and produce a final version taken into consideration their feedback.

Final assessment of adapted guidelines

We will conduct a final assessment of the validity of each item in a set of adapted guidelines. We will also record the main characteristics of the adapted guidelines (eg, title, year or adaptation process), completeness of reporting process for adapting guidelines and suggestions to improve the checklist (table 2).

We will assess a convenience sample of 10 adapted guidelines available in English and published in the last 5 years.36 We will also take into account country income level, type of organisation and region. Two reviewers from the Coordination Team will independently apply the final version of the checklist to adapted guidelines. The two reviewers will resolve potential disagreements by discussion, and if necessary, by consulting a third reviewer.

For quantitative variables (characteristics of adapted guidelines, completeness of reporting and adequacy), we will calculate absolute frequencies and proportions. For qualitative variables (suggestions to improve the checklist), we will use content analysis to summarise and draw conclusions.39 The Coordination Team will review the results, draft a report, review and agree on the relevant checklist modifications. If members of the Coordination Team do not reach consensus on specific items, they will consult the Advisory Group.

Approval of the final checklist

The Coordination Team will generate the final version of the checklist. The final checklist will highlight the changes from the RIGHT statement,29 including (1) the items that remained unchanged, (2) the items that were modified, (3) the items that were added as part of the extension, and (4) the items that were omitted. All members of the Coordination Team and the Advisory Group will need to review and approve the final version of the checklist through consensus discussion.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public will not be involved in the study.

Discussion

Executive summary

The aim of this project is to develop the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist, as an extension of the RIGHT statement tailored for guideline adaptation, to improve the rigour and transparency of guideline adaptation reporting. To develop the checklist, we will build on the RIGHT statement, use the best available evidence from published methodological research on this topic and use a rigorous multistep process involving multiple stakeholders.

Our study in the context of previous research

Adaptation of high-quality guidelines is an alternative to developing de novo guidelines that saves both time and resources, and avoids duplication of effort. The ADAPTE framework is one of the earliest systematic approaches to adapt guidelines to local context.15 42 Building on work done for WHO in 2006, the ‘GRADE-ADOLOPMENT’ framework proposed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Evidence to Decision frameworks for the adaptation, adoption and de novo development of guidelines.16 Despite these advances, there is variability in the quality of reporting of adapted practice guidelines and no guidance for their reporting is available.23 25 The proposed checklist might help with reducing the variability of adaptation process and improving the quality of reporting. The checklist is not intended to support guideline development, which will be done through an extension of the GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist.43

Strengths and limitations

Our proposal has some limitations. For example, we will only include guidelines published in English in the assessment of adapted guidelines. The checklist will inform about the completeness of the reporting but not necessarily about the quality of the adaptation process. We will not conduct a complete formal validation of the checklist since our current process will not include an assessment of neither construction nor criterion validity44; however, our proposed approach will ensure both face and content validity.

Our proposal has several strengths. The development of the checklist will be comprehensive, including the use of previous methodological evidence23–25 29 31 32 and the engagement of the multidisciplinary international guideline community. We will collect views and experiences from different stakeholders, including methodologists, guideline developers, guideline users and journal editors. We will also ensure the diversity of participants in terms of country level of income, gender and field of expertise. This will allow us to incorporate the different stakeholders’ perspective about the adaptation of guidelines. We will address the risk of bias in each step of the development process. To minimise interviewer bias, semistructured interviews will be conducted using an interview guide. To minimise selection bias, we will invite all GIN Adaptation Guidelines Working Group members as well as other stakeholders to join the Delphi Panel and to participate in the external review survey. To minimise non-response bias, we will make the survey available online for 4 weeks and we will send two reminders prior to the round closing date.

Implications for practice and research

RIGHT-Ad@pt will help improve the completeness when reporting adapted guidelines, therefore contribute to improve their quality, and facilitate their implementation. The checklist will allow the guideline developers to guide their reporting, journal editors to improve the reporting of published adapted guidelines, policymakers to inform on implementation decisions and guideline users to evaluate the completeness of the reporting within adapted guidelines. Future research should focus on the performance of a complete formal validation of the checklist and its assessment in a representative sample of contemporary adapted guidelines. Surveillance on the use of the checklist and assessment of its impact could also be a topic of research.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol obtained a waiver of approval (did not involve patients, biological samples or clinical data) from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain). Nevertheless, we will request written informed consent from all participants and anonymise all data.

The dissemination activities will include: (1) publication of the RIGHT-Ad@pt Checklist in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) presentation of the project to relevant stakeholders (eg, via international conferences, electronic bulletins, related websites (http://www.right-statement.org/, http://www.equator-network.org/) and social media (eg, Twitter); and (3) translation of the checklist into different languages. The implementation activities will include: (1) engaging with journal editors to encourage the use of the checklist; and (2) evaluation of the impact of the checklist on the reporting of adapted guidelines. Finally, we will continuously seek feedback from stakeholders, surveil new relevant evidence and, if necessary, update the checklist.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Yang Song is a doctoral candidate at the Paediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Preventive Medicine Department, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. The authors thank Victoria Leo for her help in editing the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: YS, AD, LMG, PAC and EAA wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YS, MB, LMG, PAC and EAA form the coordination team and have day-to-day responsibility for the project. TA, SB, YC, FC, DG, PFP, EVL, HJS and RWMV are independent advisors of the project and provide methodological contributions for the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version.

Funding: YS is funded by China Scholarship Council (No 201707040103). LMG is funded by a Miguel Servet contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP18/00007).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: EAA and HJS have intellectual CoIs related to his contribution to the development of methods of guideline adaptation, the RIGHT statement and methodological studies in the field. SB is the Analyses Advisor for BMJ and Associate Editor at BMJ Global Health and BMC Systematic Reviews. All other members have nothing to declare.

Ethics approval: Clinical Research Ethics Committee at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona, Spain).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization WHO handbook for guideline development. WHO handbook for guideline development, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. BMJ Qual Saf 2010;19:e58 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armstrong JJ, Goldfarb AM, Instrum RS, et al. Improvement evident but still necessary in clinical practice guideline quality: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:13–21. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Institute of Medicine Clinical practice guideline we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. WHO Advisory Committee on health research. improving the use of research evidence in Guideline development: 1. guidelines for guidelines. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhaumik S. Use of evidence for clinical practice guideline development. Trop Parasitol 2017;7:65–71. 10.4103/tp.TP_6_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhaumik S, Jagadesh S, Ellatar M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines in India: quality appraisal and the use of evidence in their development. J Evid Based Med 2018;11:26–39. 10.1111/jebm.12285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canelo-Aybar C, Balbin G, Perez-Gomez Á, et al. [Clinical practice guidelines in Peru: evaluation of its quality using the AGREE II instrument]. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 2016;33:732–8. 10.17843/rpmesp.2016.334.2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kredo T, Gerritsen A, van Heerden J, et al. Clinical practice guidelines within the Southern African Development Community: a descriptive study of the quality of guideline development and concordance with best evidence for five priority diseases. Health Res Policy Syst 2012;10 10.1186/1478-4505-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Machingaidze S, Zani B, Abrams A, et al. Series: clinical epidemiology in South Africa. paper 2: quality and reporting standards of South African primary care clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;83:31–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Machingaidze S, Grimmer K, Louw Q, et al. Next generation clinical guidance for primary care in South Africa - credible, consistent and pragmatic. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195025 10.1371/journal.pone.0195025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molino CG, Romano-Lieber NS, Ribeiro E, et al. Non-Communicable disease clinical practice guidelines in Brazil: a systematic assessment of methodological quality and transparency. PLoS One 2016;11:e0166367 10.1371/journal.pone.0166367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Talagala IA, Samarakoon Y, Senanayake S, et al. Sri Lankan clinical practice guidelines: a methodological quality assessment utilizing the agree II instrument. J Eval Clin Pract 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fervers B, Burgers JS, Haugh MC, et al. Adaptation of clinical guidelines: literature review and proposition for a framework and procedure. Int J Qual Health Care 2006;18:167–76. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R, et al. Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:228–36. 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:101–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darzi A, Harfouche M, Arayssi T, et al. Adaptation of the 2015 American College of Rheumatology treatment guideline for rheumatoid arthritis for the Eastern Mediterranean Region: an exemplar of the GRADE Adolopment. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:183 10.1186/s12955-017-0754-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Okely AD, Ghersi D, Hesketh KD, et al. A collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines - The Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the early years (Birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. BMC Public Health 2017;17(S5):869 10.1186/s12889-017-4867-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgers JS, Anzueto A, Black PN, et al. Adaptation, evaluation, and updating of guidelines: article 14 in integrating and coordinating efforts in COPD Guideline development. An official ATS/ERS workshop report. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012;9:304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kristiansen A, Brandt L, Agoritsas T, et al. Applying new strategies for the national adaptation, updating, and dissemination of trustworthy guidelines: results from the Norwegian adaptation of the antithrombotic therapy and the prevention of thrombosis, 9th Ed: American College of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2014;146:735–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehndiratta A, Sharma S, Prakash N, et al. Adapting clinical guidelines in India—a pragmatic approach. BMJ 2017;359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kredo T, Bernhardsson S, Machingaidze S, et al. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:122–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Darzi A, Abou-Jaoude EA, Agarwal A, et al. A methodological survey identified eight proposed frameworks for the adaptation of health related guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;86:3–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Godah MW, Abdul Khalek RA, Kilzar L, et al. A very low number of national adaptations of the World Health Organization guidelines for HIV and tuberculosis reported their processes. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;80:50–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abdul–Khalek RA, Darzi AJ, Godah MW, et al. Methods used in adaptation of health–related guidelines: a systematic survey. J Glob Health 2017;7:020412 10.7189/jogh.07.020412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, et al. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000217 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K. Agree next steps Consortium. The agree reporting checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen Y, Yang K, Marušic A, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: the right statement. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:128–32. 10.7326/M16-1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tokalić R, Viđak M, Buljan I, et al. Reporting quality of European and Croatian health practice guidelines according to the RIGHT reporting checklist. Implement Sci 2018;13 10.1186/s13012-018-0828-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vernooij RWM, Alonso-Coello P, Brouwers M, et al. Reporting items for updated clinical guidelines: checklist for the reporting of updated guidelines (CheckUp). PLoS Med 2017;14:1002207 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martínez García L, Pardo-Hernandez H, Niño de Guzman E, et al. Development of a prioritisation tool for the updating of clinical guideline questions: the UpPriority tool protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017226 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:37 10.1186/1471-2288-5-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000393 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glenton C, Carlsen B, Lewin S, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings—paper 5: how to assess adequacy of data. Implement Sci 2018;13(S1). 10.1186/s13012-017-0692-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, et al. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:67 10.1186/1471-2288-10-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grossoehme DH. Overview of qualitative research. J Health Care Chaplain 2014;20:109–22. 10.1080/08854726.2014.925660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guetterman TC. Descriptions of sampling practices within five approaches to qualitative research in education and the health sciences. Forum Qual Soc Res 2015;16. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes In: Archives of psychology, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 41. van der Weegen, Verwey R, Tange H, et al. Usability testing of a monitoring and feedback tool to stimulate physical activity. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:311–22. 10.2147/PPA.S57961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 13. Applicability, transferability and adaptation. Health Res Policy Syst 2006;4 10.1186/1478-4505-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. Can Med Assoc J 2014;186:E123–42. 10.1503/cmaj.131237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. AGREE Collaboration Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:18–23. 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031767supp001.pdf (57.3KB, pdf)