Abstract

Objective

To conduct a secondary data analysis detailing overweight prevalence and associations between key hypothesised determinants and overweight.

Design

This observational study used publicly available data from the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) (1993–2014). The IFLS is a home-based survey of adults and children that collected data on household characteristics (size, physical infrastructure, assets, food expenditures), as well as on individual-level educational attainment, occupation type, smoking status and marital status. These analyses used data on the self-reported consumption of ultra-processed foods and physical activity. Anthropometrics were measured.

Setting

Indonesia.

Primary outcome measures

We described the distribution of overweight by gender among adults (body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2) and by age among children, over time. Overweight was defined as weight-for-height z-score >2 among children aged 0–5 years and as BMI-for-age z-score >1 among children aged 6–18 years. We also described individuals who were overweight by selected characteristics over time. Finally, we employed multivariable logistic regression models to investigate risk factors in relation to overweight in 2014.

Results

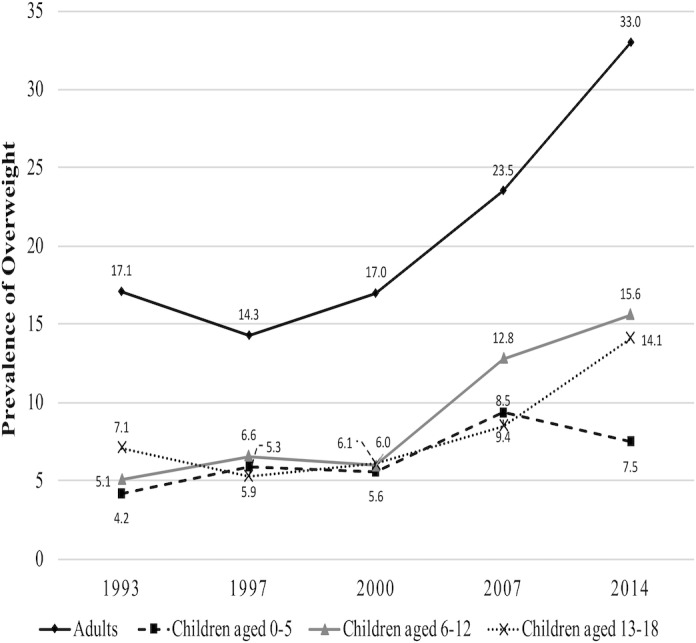

One-third of adults were overweight in 2014. Between 1993 and 2014, the prevalence of overweight among adults doubled from 17.1% to 33.0%. The prevalence of overweight among children under 5 years increased from 4.2% to 9.4% between 1993 and 2007, but then remained relatively stagnant between 2007 and 2014. Among children aged 6–12 years and 13–18 years, the prevalence of overweight increased from 5.1% to 15.6% and from 7.1% to 14.1% between 1993 and 2014, respectively. Although overweight prevalence remains higher in urban areas, the increase in overweight prevalence was larger among rural (vs urban) residents, and by 2014, the proportions of overweight adults were evenly distributed in each wealth quintile. Data suggest that the consumption of ultra-processed foods was common and levels of physical activity have decreased over the last decade. In multivariable models, urban area residence, higher wealth, higher education and consumption of ultra-processed foods were associated with higher odds of overweight among most adults and children.

Conclusion

Urgent programme and policy action is needed to reduce and prevent overweight among all ages.

Keywords: overweight, Indonesia, nutrition transition, Indonesian Family Life Survey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Key study strengthsare that we are able to compare overweight trends over time among all age groups, to explore the consumption of ultra-processed foods and physical activity and to investigate hypothesised risk factors for overweight, using regression-based methods.

We use a recent dataset that is nationally representative of Indonesia.

A key limitation is that we largely employ cross-sectional data, and therefore, we cannot infer any causal associations.

Data on the consumption of a select number of ultra-processed foods were only collected in 2014, which limits our ability to make conclusions about the association between ultra-processed foods and overweight over time.

Physical activity levels were based on respondent recall.

Introduction

Indonesia is undergoing a nutrition transition as one-third of adults are now overweight or obese. Nutrition transition theory suggests that economic development, urbanisation and globalisation result in an increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods and a decrease in physical activity,1 2 which subsequently lead to a higher prevalence of overweight and non-communicable diseases. Context-specific policy, food systems, sociocultural norms and socioeconomics are also thought to play a role.2 Mitigating the obesity pandemic through appropriate programmes and policies requires a better understanding of setting-specific trends and their underlying determinants. Yet, prior studies provide limited information on the changing prevalence and risk factors for overweight, by age group, in Indonesia. We aimed to fill this gap in the literature by detailing overweight prevalence over time and investigating the relation between key risk factors and overweight, among all age groups in Indonesia.

Several factors have likely contributed to the increasing prevalence of overweight in Indonesia. First, economic development, urbanisation and globalisation have altered the food environment in Indonesia,3 as these factors result in easier access to and demand for processed foods.4 5 In Indonesia, food availability per capita has increased by 40% over the last two decades, which is largely driven by an increase in the availability of fats (eg, palm oil).6 Subsequently, poor dietary habits are now common among Indonesians. Data from the 2013 National Basic Health Research Survey indicated inadequate consumption of fruits and vegetables among the majority of Indonesians, and one prior study reported that higher consumption of meat and dairy was associated with a higher prevalence of obesity in Indonesia.7 Prior evidence from Indonesia and the Southeast Asia region also suggests widespread consumption of ultra-processed foods and a positive association between consumption of processed foods, meat, dairy and ‘Western foods’ and overweight prevalence among children and adults.6–8 Second, economic development and urbanisation also result in decreased physical activity and the Indonesian population is increasingly adopting a more sedentary lifestyle.9–12 In part, this is due to changes in technology, which have led to more mechanised agricultural production and shifts away from agricultural-based employment. In addition, Indonesians perceive that increased motorised transport and rapid changes in the built environment have resulted in reduced physical activity.13 Limited data also suggest that there are few bike lanes, sidewalks or parks in Indonesia.6

The objectives of this study were twofold. First, we document the changes in overweight prevalence that have occurred in Indonesia, between 1993 and 2014, among adults (aged ≥19 years), adolescents (aged 13–18 years), school-aged children (aged 6–12 years) and young children (aged 0–5 years). Second, this study provides a comprehensive examination of risk factors for overweight, by age, using regression-based methods. We believe the evidence will be useful for future advocacy efforts on obesity prevention and to inform relevant policy dialogues and programme design.

Methods

Study context

Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country, home to approximately 260 million individuals, and is the largest economy in Southeast Asia.14 Indonesia’s gross domestic product per capita has steadily risen, from $807 in 2000 to $3877 in 2018.15 Over the last 40 years, Indonesia has experienced a process of rapid urbanisation and industrialisation, which have contributed to Indonesia’s changing infrastructure. More than half of the population now live in an urban area and urbanisation is increasing at a rate of 2.3% annually. Economic development and urbanisation are related to changes in diet and physical activity. At the same time, the demographic transition (ie, the shift from a pattern of high fertility and high mortality to one of low fertility and low mortality) affects and is affected by nutritional change. Indonesia is in the middle phase of their demographic transition, expecting to harness the peak of demographic dividend between 2020 and 2030.16

Survey design and study population

These analyses used the publicly available Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), which has previously been detailed elsewhere.17 18 The IFLS is a longitudinal, home-based survey that collected socioeconomic and health data on individual respondents including children aged 0–18 and adults ≥19 years, and their households over time. The survey was first fielded in 1993 and there have been four subsequent rounds of data collection (1997, 2000, 2007, 2014). Follow-up surveys were fielded on the full sample and split-off households. Therefore, new members were added to the panel during each subsequent survey wave.

As described in detail elsewhere,17 the original, multistage sampling frame was based on households from 13 out of 27 Indonesian provinces: North Sumatra, West Sumatra, South Sumatra, Lampung, DKI Jakarta, West Java, Central Java, Yogyakarta, East Java, Bali, West Nusa Tenggara, South Kalimantan and South Sulawesi. These provinces were selected to maximise representation of the population, capture the cultural and socioeconomic diversity of Indonesia and be cost-effective. The sample represented approximately 83% of the Indonesian population in 1993.17 Within each of the 13 provinces, 321 enumeration areas were randomly chosen from the nationally representative sample frame used in the 1993 National Socioeconomic Survey. Urban areas were oversampled in the original survey; 20 households were randomly selected from each urban enumeration area and 30 households were randomly selected from each rural enumeration area. Original and split-off households were recontacted in subsequent survey waves. Indonesia now has 34 provinces, as eight have been added since 1999. As individuals moved between provinces within Indonesia over time, additional provinces were represented in the survey. In 2014, 24 provinces were represented.

The IFLS was approved by institutional review boards in the USA at RAND Corporation and in Indonesia at the University of Gadjah Mada. Survey participants provided written informed consent. A parent or guardian (typically the mother) provided informed consent for children younger than 11 years.19 The data used for this study are retrospective and the authors did not have access to any identifying information. As such, ethical approval was not required.

Survey questions

Many questions were consistently asked during each survey wave, but some were added or eliminated over the 20-year survey period to reflect the changing economic context. The household questionnaire collected information on household characteristics such as its size, physical infrastructure, access to sanitation and water sources, assets and food expenditures (see online supplementary table 1). Each adult respondent was asked about characteristics related to demographics (eg, marital status, age), socioeconomic status (eg, educational attainment, occupation) and health history (eg, smoking). Beginning in 2000, adults were also asked about their food intake in the past week; specifically, respondents indicated whether they ate each food type (eg, in the last week, did you eat any […]) and the frequency of consumption (eg, how many days in a week did you eat […] in the last week). In 2000 and 2007, self-reported diet questions focused on staple foods (eg, rice, eggs, dairy) and iron- and vitamin-A rich foods (eg, meat, green leafy vegetables, carrots, sweet potatoes). Ultra-processed foods (instant noodles, fast food, soft drinks, fried snacks) were added in 2014. In addition, married women were asked about their reproductive history and breast feeding and complementary feeding practices for children born within the 5 years prior to the survey.

bmjopen-2019-031198supp001.pdf (368.3KB, pdf)

In 2007 and 2014, adults were asked about the type, duration (eg,<2 hours or ≥2 hours) and number of days of physical activities they engaged during the last week. Activity type included vigorous activity, moderate activity and walking, using a modified version of the International Survey on Physical Activities. Vigorous physical activity was defined as any activities that make you breathe much harder than normal (eg, heavy lifting, digging, cycling with loads). Moderate physical activity was defined as any activities that make you breathe somewhat harder than normal (eg, carrying light loads, bicycling or mopping the floor). Walking included at work and at home, walking from place to place and walking for recreation.

The child questionnaire paralleled the adult questionnaire, with age-appropriate modifications. Specifically, information was collected on age, gender, educational attainment, morbidities and food frequency. Physical activity was not collected among children. For children younger than 11 years, the mother, female guardian or household caretaker answered the questions. Children aged ≥11 years were allowed to respond for themselves.

Height and weight were measured for adults and children by trained interviewers, using a rigorous research protocol.17 Interviewers completed both didactic and hands-on anthropometric training and after completing each questionnaire and measurements in the field, interviewers checked for completeness and errors, using a computer-assisted programme. Supervisors randomly observed interviewers to ensure that measurements were being performed according to the training instructions. Height was measured to the nearest millimetre using a Seca plastic height board. Recumbent height was measured among children aged <24 months. Weight was measured to the nearest one-tenth of a kilogram using a Camry model EB1003 scale.

Statistical analysis

Overweight served as our a priori primary endpoint. Among adults (aged ≥19 years), overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2. Among children and adolescents aged 6–18 years, overweight was defined as BMI-for-age z-score >1 using the WHO reference.20 Among children aged 0–5 years, overweight was defined as weight-for-height z-score >2 using the Multicentre Growth Reference Study Standard.21

Appropriate cut-offs were applied to create dichotomous or categorical variables for age, educational attainment and occupation. Urban/rural residence, diet and physical activity data were modelled as binary variables. Household wealth quintiles were created using principal component analysis, using following variables: type of floor material, type of toilet, type of cooking fuel and ownership of assets including: land, livestock, vehicle(s), household appliances, furniture and utensils, jewellery and monetary savings. Dichotomous variables were created from these categorical variables and a frequency test was run for each of the new variables to ensure that those variables with a variance of zero were removed. The wealth score was then split into quintiles based on the distribution of the data.

Household food expenditures on rice and cooking oil represented the household-level expenditure on each item as a percentage of the households’ total expenditures on food. Food expenditures were then dichotomised as lower and higher based on the mean value in each survey year. Rice was selected as it is a key staple food in Indonesia. Cooking oil was also selected because it has been shown to perpetuate energy imbalance.

Descriptive statistics are presented as percentages for categorical variables or means for continuous variables. The distribution of overweight by gender (adult women and adult men aged ≥19 years) and age (0–5 years, 6–12 years, 13–18 years) was detailed for each survey year. Then, we described individuals who were overweight, by the aforementioned characteristics (eg, education, wealth), from 1993 to 2014. Finally, we described the distribution of the consumption of ultra-processed foods and of physical activity among adults in 2014.

Prior conceptual models,2 22 23 along with the availability of data in the IFLS were used to identify plausible determinants of the obesity endemic in Indonesia. To create a parsimonious model, univariate analyses first explored risk factors and their association with overweight, using cross-sectional logistic regression models, for five groups in 2014: adult women, adult men, children aged 0–5 years, children aged 6–12 years and children aged 13–18 years. Largely, variables were included in multivariable models if they were statistically significantly associated with the dependent variable in univariate models (defined as p<0.05). Age, gender, urban/rural residence and wealth were included in the multivariable logistic regression models irrespective of statistical significance. Pregnant women were excluded from analyses. We assessed multicollinearity in all models.

In sensitivity analyses, we explored the association between selected risk factors and overweight among adults, over time (1993–2014), using modified Poisson models.24 These longitudinal models were considered sensitivity analyses because individual-level consumption of ultra-processed foods and physical activity data were not available in prior years. Alpha was set to 0.05 to determine statistical significance. All analyses employed sampling weights, which account for the survey design and were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in this secondary data analysis.

Results

Between 1993 and 2014, the prevalence of overweight among adults doubled from 17.1% to 33.0% (figure 1). The prevalence of overweight among children under 5 years increased from 4.2% to 9.4% between 1993 and 2007, but since then, remained relatively stagnant. Among children aged 6–12 years and 13–18 years, the prevalence of overweight increased from 5.1% to 15.6% and from 7.1% to 14.1% between 1993 and 2014, respectively.

Figure 1.

Per cent distribution of overweight in Indonesia, 1993–2014. (1) Percentages are weighted to be representative of the population of Indonesia in the given survey year. (2) Adults: excludes women who are currently pregnant. Overweight defined as body mass index ≥25 kg/m2. (3) Children aged 0–5 years: overweightdefined as weight-for-height z-score >2 using the Multicentre Growth Reference Study Standard. (4) Children aged 6–18 years: overweight as body mass index-for-age z-score >1 using the WHO Reference.

The characteristics of overweight individuals are presented in tables 1–4 and in online supplementary tables 2–4. More women and men over 40 years old (vs younger ages) were overweight over the study period (tables 1 and 2). Most overweight women and men had at least a primary school education, and more than half lived in urban areas. The distribution of wealth among overweight adults varied over time. In 1993, the largest percentage of overweight women (29.4%) was in the wealthiest households, whereas in 2014, wealth was evenly distributed (~20%). Trends were similar for men.

Table 1.

Per cent distribution of selected characteristics among overweight adult women aged 19+ years in Indonesia over time (1993-2014)

| 1993*† | 1997*† | 2000*† | 2007*† | 2014*† | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 19–29 | 97 | 18.9 | 248 | 18.7 | 423 | 14.7 | 848 | 15.6 | 1197 | 10.9 |

| 30–39 | 253 | 38.1 | 531 | 32.6 | 728 | 30.5 | 1167 | 24.8 | 1937 | 19.6 |

| 40–49 | 178 | 25.4 | 473 | 27.0 | 699 | 29.9 | 1044 | 31.1 | 1511 | 31.9 |

| 50–59 | 97 | 14.3 | 255 | 13.2 | 342 | 15.4 | 618 | 17.6 | 996 | 24.4 |

| ≥60 | 24 | 3.3 | 169 | 8.6 | 254 | 9.6 | 389 | 10.9 | 551 | 13.2 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| No education | 39 | 7.3 | 225 | 14.5 | 276 | 11.2 | 279 | 9.1 | 263 | 6.9 |

| Primary | 415 | 66.7 | 832 | 61.7 | 1232 | 54.6 | 1702 | 53.7 | 2198 | 50.4 |

| Junior or senior | 152 | 20.3 | 308 | 19.4 | 711 | 27.0 | 1109 | 28.6 | 2077 | 32.8 |

| University | 43 | 5.7 | 69 | 4.4 | 172 | 7.2 | 335 | 8.6 | 623 | 9.9 |

| Parity‡ | ||||||||||

| ≤2 | 16 | 15.2 | 20 | 43.1 | 71 | 20.1 | 56 | 20.1 | 428 | 35.8 |

| 3–4 | 19 | 17.7 | 8 | 14.2 | 72 | 18.4 | 76 | 24.9 | 230 | 29.9 |

| ≥5 | 84 | 67.1 | 20 | 42.7 | 254 | 61.5 | 191 | 55.0 | 306 | 34.4 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Non-smoker | 614 | 96.7 | 1553 | 95.6 | 2311 | 96.1 | 3889 | 97.5 | 6027 | 97.4 |

| Smoker | 25 | 3.3 | 73 | 4.4 | 99 | 3.9 | 101 | 2.5 | 134 | 2.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 10 | 2.8 | 85 | 5.0 | 146 | 4.8 | 237 | 4.9 | 291 | 3.1 |

| Married | 582 | 89.1 | 1336 | 82.7 | 1926 | 80.4 | 3298 | 81.9 | 5185 | 81.7 |

| Other | 49 | 8.1 | 220 | 12.3 | 351 | 14.8 | 475 | 13.2 | 714 | 15.2 |

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Not working | 362 | 57.0 | 803 | 50.8 | 969 | 39.8 | 1527 | 37.6 | 2178 | 35.2 |

| Agriculture | 27 | 5.5 | 135 | 8.8 | 260 | 11.6 | 517 | 14.5 | 816 | 15.6 |

| Skilled manual§ | 44 | 6.2 | 141 | 9.3 | 201 | 9.3 | 315 | 8.2 | 479 | 8.4 |

| Skilled¶ | 202 | 31.3 | 545 | 31.1 | 956 | 39.2 | 1616 | 39.7 | 2618 | 40.8 |

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Rural | 150 | 33.4 | 583 | 43.0 | 893 | 41.5 | 1604 | 47.3 | 2286 | 46.0 |

| Urban | 499 | 66.6 | 1093 | 57.0 | 1553 | 58.5 | 2462 | 52.7 | 3906 | 54.0 |

| Wealth | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 81 | 14.4 | 238 | 17.3 | 323 | 15.2 | 603 | 16.3 | 1095 | 23.0 |

| Second | 64 | 10.3 | 233 | 16.9 | 388 | 19.5 | 875 | 27.6 | 1087 | 22.7 |

| Middle | 163 | 21.0 | 312 | 23.4 | 430 | 20.9 | 521 | 15.8 | 781 | 17.3 |

| Fourth | 203 | 24.9 | 270 | 19.9 | 426 | 20.8 | 679 | 20.4 | 894 | 18.7 |

| Highest | 645 | 29.4 | 330 | 22.5 | 475 | 23.5 | 645 | 19.9 | 848 | 18.3 |

| Family size | ||||||||||

| ≤4 | 249 | 40.2 | 533 | 33.3 | 1161 | 48.8 | 1274 | 30.2 | 3898 | 65.3 |

| >4 | 400 | 59.8 | 1143 | 66.7 | 1285 | 51.2 | 2792 | 69.8 | 2294 | 34.7 |

| Province | ||||||||||

| Bali | 78 | 18.6 | 213 | 13.0 | 305 | 14.0 | 522 | 16.8 | 774 | 17.0 |

| Central Java | 107 | 26.0 | 243 | 22.7 | 369 | 24.2 | 576 | 24.3 | 885 | 25.1 |

| West Java | 92 | 20.4 | 272 | 23.5 | 416 | 25.6 | 606 | 19.4 | 955 | 19.8 |

| Other | 372 | 36.7 | 948 | 46.8 | 1353 | 40.2 | 2171 | 42.1 | 3232 | 40.8 |

| Food expenditures** | ||||||||||

| Rice | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 186 | 49.5 | 880 | 53.1 | 1242 | 51.6 | 2114 | 53.2 | 3137 | 53.0 |

| Highest | 205 | 50.5 | 790 | 46.9 | 1198 | 48.4 | 1951 | 46.8 | 3051 | 47.0 |

| Cooking oil | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 198 | 42.5 | 786 | 49.3 | 1174 | 48.6 | 1827 | 45.4 | 3562 | 58.6 |

| Highest | 340 | 57.5 | 882 | 50.7 | 1266 | 51.4 | 2238 | 54.6 | 2625 | 41.4 |

*Overweight is defined as body mass index ≥25 kg/m2. Percentages are weighted to be representative of the population of Indonesia in the given survey year.

†Excludes women who are currently pregnant.

‡Parity is only queried among ever-married women.

§Skilled manual labour combines the following employment sectors: mining, manufacturing, electric, gas, water maintenance and construction.

¶Skilled labour combines the following employment sectors: retail and service, transportation.

**Represents the household level expenditure on each item as a percentage of the households’ total expenditures on food.

Table 2.

Per cent distribution of selected characteristics among overweight men aged 19+ years in Indonesia over time (1993-2014)

| 1993* | 1997* | 2000* | 2007* | 2014* | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| 19–29 | 27 | 7.3 | 88 | 13.4 | 224 | 14.1 | 419 | 15.6 | 573 | 16.5 |

| 30–39 | 117 | 34.3 | 196 | 30.7 | 356 | 28.7 | 698 | 24.6 | 1048 | 21.7 |

| 40–49 | 121 | 33.4 | 215 | 32.0 | 336 | 31.8 | 549 | 30.6 | 885 | 25.4 |

| 50–59 | 52 | 14.4 | 123 | 16.1 | 184 | 17.2 | 326 | 20.7 | 514 | 25.0 |

| ≥60 | 35 | 10.6 | 62 | 7.8 | 99 | 8.2 | 164 | 8.5 | 262 | 11.4 |

| Education | ||||||||||

| No education | 6 | 2.0 | 24 | 3.8 | 32 | 2.5 | 32 | 1.8 | 39 | 1.8 |

| Primary | 153 | 44.6 | 227 | 40.8 | 385 | 34.2 | 553 | 34.5 | 725 | 32.4 |

| Junior or senior | 124 | 37.9 | 210 | 35.6 | 519 | 43.0 | 805 | 42.6 | 1288 | 45.0 |

| University | 68 | 15.5 | 112 | 19.8 | 247 | 20.3 | 386 | 21.1 | 612 | 20.8 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Non-smoker | 163 | 44.9 | 289 | 41.3 | 527 | 44.8 | 897 | 43.6 | 1481 | 46.5 |

| Smoker | 181 | 55.1 | 371 | 58.7 | 651 | 55.2 | 1212 | 56.4 | 1779 | 53.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Never married | 4 | 3.0 | 54 | 8.2 | 131 | 8.6 | 218 | 8.9 | 353 | 9.6 |

| Married | 342 | 96.8 | 605 | 90.4 | 1031 | 89.7 | 1850 | 88.2 | 2833 | 87.1 |

| Other | 1 | 0.2 | 11 | 1.4 | 22 | 1.7 | 56 | 2.9 | 95 | 3.3 |

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Not working | 34 | 12.4 | 70 | 9.8 | 84 | 7.4 | 165 | 8.7 | 248 | 8.7 |

| Agriculture | 27 | 9.9 | 100 | 15.2 | 179 | 15.8 | 328 | 16.1 | 500 | 16.7 |

| Skilled manual† | 87 | 25.8 | 123 | 19.7 | 199 | 17.5 | 377 | 17.7 | 598 | 18.8 |

| Skilled labour‡ | 185 | 51.9 | 366 | 55.4 | 687 | 59.4 | 1231 | 57.6 | 1874 | 55.9 |

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Rural | 73 | 33.5 | 211 | 35.7 | 381 | 36.0 | 717 | 39.0 | 987 | 37.4 |

| Urban | 279 | 66.5 | 473 | 64.3 | 818 | 64.0 | 1439 | 61.0 | 2294 | 62.6 |

| Wealth | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 22 | 7.3 | 82 | 11.8 | 130 | 10.9 | 324 | 15.6 | 547 | 19.9 |

| Second | 26 | 6.7 | 88 | 14.1 | 166 | 16.1 | 460 | 23.9 | 562 | 20.1 |

| Middle | 61 | 18.7 | 135 | 22.5 | 214 | 19.4 | 304 | 15.5 | 445 | 17.0 |

| Fourth | 72 | 20.6 | 118 | 19.7 | 267 | 23.8 | 418 | 22.1 | 554 | 19.9 |

| Highest | 169 | 46.6 | 205 | 31.9 | 315 | 29.8 | 418 | 22.9 | 661 | 23.1 |

| Family size | ||||||||||

| ≤4 | 128 | 36.9 | 218 | 32.7 | 579 | 50.0 | 712 | 30.9 | 2061 | 63.9 |

| >4 | 224 | 63.1 | 466 | 67.3 | 620 | 50.0 | 1444 | 69.1 | 1220 | 36.1 |

| Province | ||||||||||

| Bali | 38 | 16.5 | 70 | 9.7 | 116 | 10.8 | 227 | 14.4 | 369 | 14.0 |

| Central Java | 58 | 29.6 | 88 | 20.3 | 162 | 22.6 | 289 | 23.2 | 457 | 24.2 |

| West Java | 38 | 17.2 | 100 | 23.2 | 195 | 26.4 | 308 | 20.3 | 433 | 21.0 |

| Other | 141 | 36.7 | 313 | 46.8 | 540 | 40.2 | 980 | 42.1 | 1531 | 40.8 |

| Food expenditures§ | ||||||||||

| Rice | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 83 | 43.0 | 365 | 53.5 | 627 | 52.0 | 1135 | 53.5 | 1709 | 54.5 |

| Highest | 103 | 57.0 | 314 | 46.5 | 564 | 48.0 | 1016 | 46.5 | 1561 | 45.5 |

| Cooking oil | ||||||||||

| Lowest | 89 | 34.5 | 290 | 43.6 | 525 | 45.2 | 936 | 42.8 | 1811 | 56.6 |

| Highest | 203 | 65.5 | 388 | 56.4 | 665 | 54.8 | 1215 | 57.2 | 1459 | 43.4 |

*Overweight is defined as body mass index ≥25 kg/m2. Percentages are weighted to be representative of the population of Indonesia in the given survey year.

†Skilled manual labour combines the following employment sectors: mining, manufacturing, electric, gas, water maintenance and construction.

‡Skilled labour combines the following employment sectors: retail and service, transportation.

§Represents the household level expenditure on each item as a percentage of the households’ total expenditures on food.

Table 3.

Distribution and frequency of consumption of ultra-processed foods and physical activity in Indonesia, 2014

| Women | Men | Children aged 6 months–5 years | Children aged 6–12 years | Children aged 13–18 years | ||||||

| n | % or mean | n | % or mean | n | % or mean | n | % or mean | n | % or mean | |

| Instant noodles | ||||||||||

| Last week* | 9818 | 60.0 | 8703 | 63.7 | 2674 | 56.8 | 5467 | 77.5 | 2084 | 78.3 |

| Mean days† | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.9 | |||||

| Fast food | ||||||||||

| Last week* | 1718 | 9.0 | 1291 | 8.8 | 685 | 14.5 | 1357 | 18.8 | 450 | 16.3 |

| Mean days† | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | |||||

| Soda | ||||||||||

| Last week* | 1956 | 10.7 | 3281 | 22.6 | 278 | 5.0 | 1075 | 14.5 | 647 | 23.0 |

| Mean days† | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | |||||

| Fried snacks | ||||||||||

| Last week* | 9706 | 65.4 | 8668 | 68.8 | 2282 | 50.4 | 4530 | 66.4 | 1841 | 72.0 |

| Mean days† | 4.0 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.1 | |||||

| Vigorous activity‡ | ||||||||||

| Last week | 15 191 | 10.7 | 13 148 | 38.0 | na | na | na | |||

| Mean days | 3.9 | 4.2 | na | na | na | |||||

| Moderate activity‡ | ||||||||||

| Last week | 15 191 | 58.1 | 13 148 | 54.2 | na | na | na | |||

| Mean days | 4.8 | 4.4 | na | na | na | |||||

| Walking‡ | ||||||||||

| Last week | 15 191 | 68.8 | 13 148 | 72.4 | na | na | na | |||

| Mean days | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | na | na | na | ||||

*Per cent distribution, weighted to be representative of the population of Indonesia in the given survey year. n represents the number of respondents that consumed a particular item during the last week.

†The average number of days an individual consumed each food is queried only if the respondent reported that they consumed the item in the last week.

‡Defined using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Respondents are asked about each type of physical activity (ie, vigorous, moderate, walking) separately and therefore, these should be interpreted as mutually exclusive categories. The per cent distribution is weighted to be representative of the population of Indonesia in the given survey year.

na, not applicable.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression investigating the association between selected characteristics and overweight among adults aged 19+ years in Indonesia, 2014

| Women†‡ | Men†‡ | |||

| n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| N=9073 | N=5775 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 19–29 | 2403 | Reference | 1441 | Reference |

| 30–39 | 2630 | 2.03 (1.75 to 2.34)* | 1807 | 1.79 (1.40 to 2.30)* |

| 40–49 | 1943 | 2.83 (2.41 to 3.31)* | 1320 | 2.37 (1.83 to 3.08)* |

| 50–59 | 1357 | 2.36 (1.97 to 2.83)* | 719 | 2.37 (1.76 to 3.20)* |

| 60+ | 740 | 1.68 (1.34 to 2.12)* | 488 | 0.92 (0.62 to 1.36) |

| Education | ||||

| No education | 511 | Reference | 106 | Reference |

| Primary | 3562 | 2.04 (1.59 to 2.60)* | 2029 | 1.76 (0.87 to 3.57) |

| Junior or senior | 3809 | 1.89 (1.46 to 2.46)* | 2854 | 2.47 (1.21 to 5.04)* |

| University | 1191 | 1.67 (1.24 to 2.26)* | 786 | 3.66 (1.75 to 7.65)* |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Non-smoker | 8881 | Reference | 1849 | Reference |

| Smoker | 192 | 0.78 (0.55 to 1.10) | 3926 | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.60)* |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 683 | Reference | 774 | Reference |

| Married | 7909 | 2.39 (1.88 to 2.98)* | 4931 | 2.04 (1.48 to 2.82)* |

| Other | 481 | 1.54 (1.10 to 2.15)* | 70 | 1.59 (0.77 to 3.27) |

| Employment | ||||

| Not working | 3227 | Reference | 371 | Reference |

| Agriculture | 1585 | 0.66 (0.56 to 0.78)* | 1483 | 0.50 (0.35 to 0.73)* |

| Skilled manual§ | 794 | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.12) | 1290 | 0.73 (0.51 to 1.06) |

| Skilled¶ | 3467 | 1.17 (1.04 to 1.33)* | 2631 | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.61) |

| Physical activity**: | ||||

| No vigorous activity | na | 3624 | Reference | |

| Vigorous activity | na | 2151 | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.10) | |

| No moderate activity | 3663 | Reference | na | |

| Moderate activity | 5410 | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.22) | na | |

| Consumed last week: | ||||

| Instant noodles | ||||

| No | 3218 | Reference | na | |

| Yes | 5855 | 1.10 (0.98 to 1.25) | na | |

| Fast food | ||||

| No | 8116 | Reference | 5172 | Reference |

| Yes | 957 | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.27) | 603 | 1.34 (1.06 to 1.69)* |

| Soda | ||||

| No | na | 4196 | Reference | |

| Yes | na | 1579 | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.30) | |

| Fried snacks | ||||

| No | 3236 | Reference | 1782 | Reference |

| Yes | 5837 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.25)* | 3993 | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.25) |

| Mean number of days consumed in the last week††: | ||||

| Instant noodles | na | 5775 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | |

| Household level | ||||

| Food expenditures‡‡ | ||||

| Rice | ||||

| Lowest | 4408 | Reference | na | |

| Highest | 4665 | 1.02 (0.91 to 1.13) | na | |

| Cooking oil | ||||

| Lowest | 5256 | Reference | 3378 | Reference |

| Highest | 3817 | 1.24 (1.12 to 1.38)* | 2397 | 1.19 (1.02 to 1.39)* |

| Residence | ||||

| Rural | 3803 | Reference | 2401 | Reference |

| Urban | 5,270 | 1.21 (1.08 to 1.35)* | 3374 | 1.26 (1.06 to 1.50)* |

| Wealth | ||||

| Lowest | 2289 | Reference | 1354 | Reference |

| Second | 2017 | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.44)* | 1271 | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.20) |

| Middle | 1455 | 1.23 (1.03 to 1.45)* | 964 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.26) |

| Fourth | 1696 | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.25) | 1127 | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) |

| Highest | 1616 | 1.12 (0.95 to 1.32) | 1059 | 1.17 (0.92 to 1.48) |

*p<0.05.

†Overweight is defined as body mass index ≥25 kg/m2.

‡ORs and CIs are estimated using logistic regression and are weighted to account for the survey design. Pregnant women are excluded.

§Skilled manual labour combines the following employment sectors: mining, manufacturing, electric, gas, water maintenance and construction.

¶Skilled labour combines the following employment sectors: retail and service, transportation.

**Defined using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

††Modelled as a continuous variable, the average number of days consumed is queried if the respondent reported that they consumed item during the last week.

‡‡Indicates the household level expenditure on each item as a percentage of the households’ total expenditures on food.

na, not applicable, not included in multivariable model.

Nearly equal proportions of boys and girls aged 0–19 years were overweight and a majority had a parent with at least primary school education (online supplementary tables 2–4). Across all groups, the proportion of overweight children who had an overweight mother increased between 1993 and 2014. The distribution of urban/rural residence among overweight children also changed over time, with more overweight young and school-aged children residing in urban areas by 2014 (~60%) compared with 1993. The distribution of wealth among overweight children and adolescents also varied over time, but like adults, by 2014, there was an even distribution of overweight children in each wealth quintile (~20%).

Distribution of consumption of ultra-processed food and physical activity

In 2014, approximately 60% of adults reported consuming instant noodles during the last week (table 3). Likewise, about 65% of adults reported consuming fried snacks, for 4.0 days on average. Smaller proportions of adults regularly consumed fast food or soda.

Trends were similar among children. Nearly 60% of children aged 6–59 months consumed instant noodles during the last week, as did three-quarters of children aged 6–12 years (77.5%) and 13–18 years (78.3%). Half (50.4%) of children aged 6–59 months and about two-thirds of children aged 6–18 years regularly consumed fried snacks. Similar proportions of children regularly consumed fast food (~15%), irrespective of age. All age groups of children consumed soda an average of 2 days per week.

Higher proportions of men were engaged in vigorous physical activity (38.0%) compared with women (10.7%). More than half adults reported being engaged in moderate physical activity and approximately 70% reported walking during the last week. Physical activity levels decreased, among both women and men, between 2007 and 2014 (2007 data not shown).

Regression-based analyses among adults

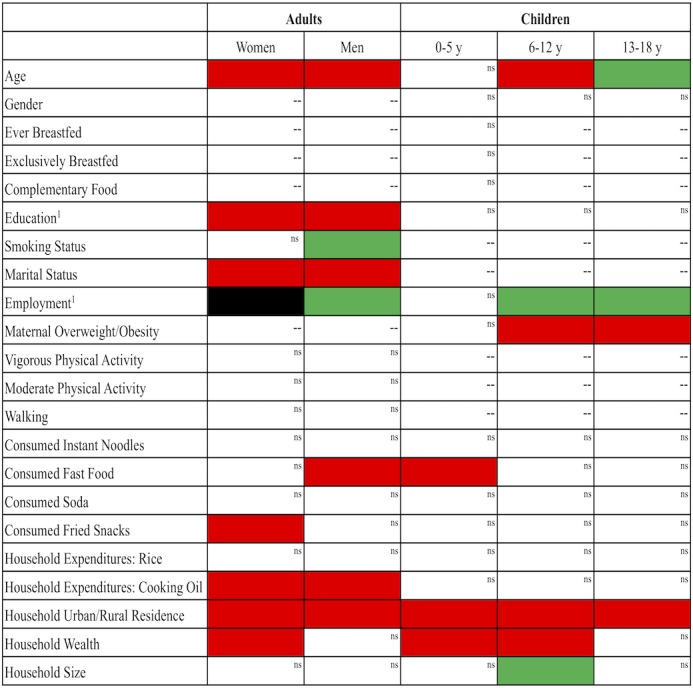

Figure 2 summarises all associations between hypothesised risk factors and overweight in multivariable models (see online supplementary tables 5 and 6 for univariable models). Among women, older age, higher education, living in an urban area and higher wealth were associated with higher odds of overweight in 2014 (table 4). Married women versus never married also had higher odds of overweight (OR=2.39; 95% CI: 1.88 to 2.98). Working in a skilled labour position, versus not working, was associated with 17% higher odds of overweight among women (OR=1.17; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.33), whereas working in agriculture-based labour, a physically demanding occupation, was associated with an approximately 30% lower odds of overweight (OR=0.66; 95% CI: 0.56 to 0.78). Household expenditures on cooking oil (OR=1.24; 95% CI: 1.12 to 1.38) and individual’s consumption of fried snacks (vs no consumption) (OR=1.12; 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.25) were associated with higher odds of overweight.

Figure 2.

Summary of associations between selected characteristics and overweight in multivariable models. Red colour is associated with higher odds of overweight in multivariable models. Green colour is associated with lower odds of overweight in multivariable models. Black colour depicts that the direction of association with overweight is mixed in multivariable models. (1) Parental characteristic for child models. --, not applicable; ns, not significant.

Similarly, among men, older age, higher educational attainment and living in an urban area were associated with higher overweight (table 4). Wealth was not associated with overweight among men. Married men versus never married had twofold higher odds of overweight (OR=2.04; 95% CI: 1.48 to 2.82). Consuming fast food, compared with not consuming fast food, was associated with 34% higher odds of overweight among men (OR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.69). Current smokers (vs non-smokers) (OR=0.51; 95% CI: 0.43 to 0.60) and men who had an agriculture-based occupation (vs not working) (OR=0.50; 95% CI: 0.35 to 0.73) had 50% lower odds of overweight. Results were similar when investigating associations among adults in longitudinal models (online supplementary tables 7 and 8).

Regression-based analyses among children

In multivariable models for children aged 6 months to 5 years, consuming fast food (OR=1.48; 95% CI: 1.00 to 2.19), urban residence (OR=1.64; 95% CI: 1.14 to 2.35) and higher household wealth (OR=1.70; 95% CI: 1.03 to 2.81) were associated with higher odds of overweight (table 5). Among children aged 6–12 years, every 1 year increase in age was associated with 6% higher odds of overweight (OR=1.06; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.11). Having an overweight mother (OR=1.92; 95% CI: 1.59 to 2.32), living in an urban area (OR=1.55; 95% CI: 1.26 to 1.91) and higher household wealth were associated with higher odds of overweight. On the contrary, parental employment in agriculture-based (OR=0.61; 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.85) or skilled manual labour (OR=0.50; 95% CI: 0.33 to 0.74) and living in households with more than four people (OR=0.82; 95% CI: 0.68 to 0.99) were associated with lower odds of overweight.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression models investigating the association between selected characteristics and overweight among children in Indonesia, 2014

| 6 months–5 years† | 6–12 years‡ | 13–18 years‡ | ||||

| n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| N=3424 | N=4791 | N=3186 | ||||

| Mean age§ | 3424 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.16) | 4791 | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11)* | 3186 | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.91)* |

| Gender | ||||||

| Boys | 1767 | Reference | 2455 | Reference | 1648 | Reference |

| Girls | 1657 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.08) | 2336 | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.15) | 1538 | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.33) |

| Parental education¶ | ||||||

| No education | 188 | Reference | 313 | Reference | 264 | Reference |

| Primary | 1234 | 0.97 (0.40 to 2.36) | 1980 | 0.73 (0.48 to 1.11) | 1505 | 1.01 (0.62 to 1.66) |

| Junior or senior | 1568 | 1.12 (0.47 to 2.65) | 1997 | 0.84 (0.55 to 1.27) | 1173 | 1.18 (0.71 to 1.94) |

| University | 434 | 1.12 (0.44 to 2.87) | 501 | 1.34 (0.84 to 2.14) | 244 | 1.38 (0.76 to 2.49) |

| Parental employment¶ | ||||||

| Not working | 1780 | Reference | 1989 | Reference | 1239 | Reference |

| Agriculture | 433 | 0.61 (0.31 to 1.21) | 821 | 0.61 (0.44 to 0.85)* | 581 | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.96)* |

| Skilled manual** | 208 | 0.98 (0.52 to 1.84) | 371 | 0.50 (0.33 to 0.74)* | 264 | 0.52 (0.33 to 0.83)* |

| Skilled†† | 1003 | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.63) | 1610 | 0.91 (0.73 to 1.13) | 1102 | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.91)* |

| Maternal overweight | ||||||

| Not overweight | 2238 | Reference | 2894 | Reference | 1834 | Reference |

| Overweight | 1186 | 1.20 (0.89 to 1.62) | 1897 | 1.92 (1.59 to 2.32)* | 1352 | 1.92 (1.53 to 2.43)* |

| Consumed last week: | ||||||

| Instant noodles | ||||||

| No | 1525 | Reference | na | na | ||

| Yes | 1899 | 0.79 (0.57 to 1.11) | na | na | ||

| Fast food | ||||||

| No | 2952 | Reference | 3909 | Reference | na | |

| Yes | 472 | 1.48 (1.00 to 2.19)* | 882 | 1.16 (0.93 to 1.45) | na | |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 1478 | Reference | 2053 | Reference | 1323 | Reference |

| Urban | 1946 | 1.64 (1.14 to 2.35)* | 2738 | 1.55 (1.26 to 1.91)* | 1863 | 1.74 (1.33 to 2.27)* |

| Wealth | ||||||

| Lowest | 830 | Reference‡‡ | 1109 | Reference | 799 | Reference |

| Second | 807 | 1.54 (0.94 to 2.53) | 1056 | 1.43 (1.06 to 1.92)* | 735 | 1.11 (0.80 to 1.54) |

| Middle | 565 | 1.43 (0.83 to 2.48) | 812 | 1.73 (1.26 to 2.36)* | 513 | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.37) |

| Fourth | 671 | 1.70 (1.03 to 2.81)* | 931 | 1.45 (1.07 to 1.95)* | 574 | 0.95 (0.65 to 1.37) |

| Highest | 551 | 1.61 (0.96 to 2.70) | 883 | 1.55 (1.14 to 2.11)* | 565 | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.33) |

| Family size | ||||||

| ≤4 | na | 2105 | Reference | 1225 | Reference | |

| >4 | na | 2686 | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99)* | 1961 | 0.87 (0.69 to 1.10) | |

*p<0.05.

†Overweight is defined as weight-for-height z-score >2 using the MGRS/WHO Standard. Coefficients are estimated using logistic regression models and are weighted to account for the survey design.

‡Overweight is defined body mass index z-score >1 using the WHO reference. Coefficients are estimated using logistic regression models and weighted to account for the survey design.

§Modelled as a continuous variable.

¶Parental characteristics are of the mother, when available. When not available, the characteristic is based on the father’s data.

**Skilled manual labour combines the following employment sectors: mining, manufacturing, electric, gas, water maintenance and construction.

††Skilled labor combines the following employment sectors: retail and service, transportation.

‡‡Wealth was not statistically significant in the univariable model but is included in the multivariable model due to previously established associations.

MGRS, Multicentre Growth Reference Study; na, not applicable, not included in multivariable model.

Having an overweight mother was associated with 92% higher odds of being overweight among adolescents (OR=1.92; 95% CI: 1.53 to 2.43). Living in an urban area also predicted higher odds of overweight among this age group (OR=1.74; 95% CI: 1.33 to 2.27). On the contrary, having a parent employed in agriculture-based labour (OR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.43 to 0.96), skilled manual labour (OR=0.52; 95% CI: 0.33 to 0.83) or skilled labour (OR=0.70; 95% CI: 0.53 to 0.91), compared with not working was associated with lower odds of overweight among adolescents.

Discussion

Several aspects of our results paint an alarming picture of obesity-related health in Indonesia. Increases in overweight prevalence were observed among all groups. Between 1993 and 2014, the prevalence of overweight increased by 100% and 88%, among women and men, respectively. Similarly, among school-aged children and adolescents, the prevalence of overweight increased by more than 100% between 1993 and 2014. Over the past two decades, more rural than urban residents became overweight, and in 2014, the proportions of overweight adults were evenly distributed among across wealth quintiles, suggesting that overweight is now prevalent among the poor. Moreover, consuming instant noodles (high in sodium) and fried snacks (high in fat) are now regularly consumed among adults and children in Indonesia and consuming fast food and fried snacks were associated with higher odds of overweight. At the same time, the rate of overweight has remained stagnant among young children, between 2007 and 2014, and being employed in a physically demanding job (ie, agriculture-based labour) remains protective against overweight.

More than half of Indonesians now live in an urban area and living in an urban area was associated with higher odds of overweight. Several other analyses have also reported higher rates of overweight in urban areas in lower-income countries25 26 and in Indonesia specifically.27–30 Urbanisation alters supply-side factors, such as the food system and the rapid spread of supermarkets in low/middle-income countries (LMICs), which makes low-cost, convenient and highly processed foods more available and accessible.31–33 Simulations suggest that a shift in the urban population from 25% to 75% is associated with a 4-percentage point increase of total energy from fat and an additional 12-percentage points of energy from sugar.34 In addition, urbanisation leads to lower physical activity, in part because the jobs that become available tend to be more sedentary.

Paralleling increased country-level economic development, the within-country socioeconomic context has changed in Indonesia. Poverty has dramatically decreased over the last 20 years, while educational attainment has increased; in 2016, approximately 34% of Indonesians had at least completed upper secondary school, compared with only 26% in 2006.14 35 Relatedly, we found that higher education was associated with higher odds of overweight among both men and women. Higher wealth was also associated with 25% higher odds of being overweight among women and a 70%, 55% and 74% higher odds of overweight among young children, school-age children and adolescents, respectively. Higher education7 and higher wealth or income7 27 have been shown to be associated with higher overweight among adults and children in prior studies conducted in Indonesia. But importantly, descriptive statistics in our study also show a growing prevalence of overweight among lower-wealth groups. For example, the per cent of overweight women in the poorest and second wealth quintiles grew by 60% and 120%, respectively. This is consistent with prior studies, which have documented an increasing burden of overweight among women with lower education and in poorer households in Indonesia and other LMICs.36–39

For both adults and children, consuming ultra-processed foods (instant noodles, fried snacks, fast food) was associated with higher odds of overweight. Prior literature on the consumption of ultra-processed foods in Indonesia is limited. But these results are generally consistent with prior findings that reported that the per cent of total energy coming from fat has increased in this context27 40 and one recent survey conducted in Asia, which suggested that the consumption of palm oil, ‘Western’ foods and processed foods are widespread.6

As Indonesia has continued to economically develop, more women are entering the labour force and less of the population is employed in agriculture-based labour. Currently, about 50% of Indonesia’s labour force is employed in the service sector, compared with 30% in agriculture and 20% in industry.14 Similar to prior literature, employment was associated with overweight in this sample.41 42 We found that skilled occupations were associated with higher odds of overweight, whereas agriculture-based employment was associated with lower odds of overweight. This is likely related to occupation-related physical activity; Monda and colleagues provide empirical evidence of a reduction in the intensity of occupational activity with economic development in China.43 In fact, reduced physical activity likely represents the most important cause of rapid overweight increases between 1990 and 2010 in most LMICs, with dietary factors playing the major role from 2010 to present.44

Similar to our results, Rachmi and colleagues report that overweight prevalence is higher among younger-aged boys versus girls in Indonesia.7 Finally, having an overweight mother was strongly associated with higher odds of overweight among school-age children and adolescents. Although the importance of intergenerational nutrition is often a concern for undernutrition, it warrants consideration for overnutrition as well. Prepregnancy maternal overweight puts infants at increased risk of being born large-for-gestational age and subsequently overweight during childhood.45–50 A child born to a mother who is overweight is twice as likely to be overweight as a child, compared with a child whose mother was normal weight.48 49

A recent report by the Economist Intelligence Unit reviewed obesity policies and interventions that are being/have been tested in Southeast Asian countries.6 Interventions that targeted food intake showed the most promise to reduce obesity. Traditionally, nutrition programmes have focused on women and young children. But our findings call for urgent action to mitigate overweight among all age groups in Indonesia and highlight the need for prevention strategies that also target men and boys, as well as individuals in rural areas. A multipronged strategy would include approaches that aim to enhance the food environment, improve the food system and provide effective social behavioural change communication.51 52 Fiscal measures, such as food-related and beverage-related taxes, to reduce the consumption of unhealthy items and subsidies for fruits and vegetables production and consumption, may be effective in improving the overall food environment and are a feasible approach for targeting most segments of the population in Indonesia.52–55 Regulatory measures to control warning labelling systems and marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages may also improve the obesogenic environment.52 56 57 It is also important to address overweight early, as child and adolescent obesity tracks into adulthood58 59; interventions aimed at improving nutrition literary and eating and physical activity behaviours through school-based nutrition education and effective social and behavioural change communication to mobilise the support of the entire community also warrant consideration.52 60 61 Using technology-based platforms, such as social media, to deliver obesity-prevention messages may be a promising strategy in Indonesia given that population is quite young. A multipronged strategy that uses a number of delivery platforms (eg, policy, healthcare system, schools) is needed to mitigate the obesity epidemic among all age groups in Indonesia.

These findings and recommendations should be interpreted while keeping in mind the limitations of our study. First, we largely employ cross-sectional data, therefore, we cannot infer any causal associations and there may be unmeasured confounding. Data on the consumption of a select number of ultra-processed foods were only collected in 2014, which limits our ability to make inferences about the association between ultra-processed foods and overweight over time. Physical activity levels were based on respondent recall. These limitations in the IFLS and the potential for unmeasured confounding with a cross-sectional study design may have attenuated some associations related to food consumption and physical activity. Finally, these findings may not be generalisable beyond Indonesia. Despite some limitations, we are able to compare overweight trends over time among all age groups, to explore the consumption of ultra-processed foods and physical activity and investigate hypothesised risk factors for overweight using regression-based methods in Indonesia.

Indonesia is undergoing nutrition transition, as evidenced by the increasing prevalence of overweight, the ubiquitous consumption of ultra-processed foods and decreasing levels of physical activity. These data suggest that urgent programme and policy action is needed to reduce and prevent overweight among all age groups. In addition, these data highlight the need for prevention strategies that also target males, as well as the increasing prevalence of overweight among rural and poorer populations. Multisectoral, multistakeholder actions and solutions are needed to improve the food environment in Indonesia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Paul Pronyk for his insightful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: VMO, MM and JHR conceptualised the research question and jointly developed the analytic plan. MM acquired the publicly available data. VMO took the primary role in data analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the manuscript. MM and JHR also provided critical input on the interpretation of the findings and provided input on all manuscript drafts. VMO, MM and JHR approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are publicly available and can be downloaded at https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/data/FLS/IFLS.html

References

- 1. Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev 2012;70:3–21. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. . The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. The Lancet 2011;378:804–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Natawidjaja R, Reardon T, Shetty S, et al. . Horticultural producers and supermarket development in Indonesia. UNPAD/MSU/World Bank World Bank Rep 2007:38543. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1181–8. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dangour AD, Hawkesworth S, Shankar B, et al. . Can nutrition be promoted through agriculture-led food price policies? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002937 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Economist Intelligence Unit Tackling obesity in ASEAN prevalence, impact, and guidance on interventions, 2017. Available: https://foodindustry.asia/documentdownload.axd?documentresourceid=30157

- 7. Rachmi CN, Li M, Alison Baur L. Overweight and obesity in Indonesia: prevalence and risk factors-a literature review. Public Health 2017;147:20–9. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prihantini S, Jahari AB. Risk factors of obesity in school children age 6–18 years in DKI Jakarta. Penelit Dizi Dan Makanan 2007;30:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schröders J, Wall S, Hakimi M, et al. . How is Indonesia coping with its epidemic of chronic noncommunicable diseases? A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179186 10.1371/journal.pone.0179186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shrimpton R, Rokx C. The double burden of malnutrition in Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. Available: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/17007

- 11. The National Institute of Health Research and Development National report on basic health research, RISKESDAS 2013. Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Widjojo S, Rahardjo S, Ljungqvist B. Health sector review Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia: UNICEF Indonesia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reality Check Approach, UNICEF Indonesia Adolescents and their families: perspectives and experiences on nutrition and physical activities. Jakarta, Indonesia: The Palladium Group and UNICEF Indonesia, 2016. http://www.reality-check-approach.com/uploads/6/0/8/2/60824721/adol_nutrition_and_physical_activity_final_1307.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. Central Intelligence Agency The world Factbook: Indonesia, 2019. Available: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/id.html

- 15. The World Bank The world bank in Indonesia, 2019. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/indonesia/overview#3

- 16. UNFPA Indonesia population projection 2015-2045, 2018. Available: https://indonesia.unfpa.org/en/publications/indonesia-population-projection-2015-2045-0 [Accessed 17 September 2019].

- 17. Strauss J, Witoelar F, Sikoki B. The fifth wave of the Indonesia family life survey: overview and field report. CA, USA: RAND, 2016. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/working_papers/WR1100/WR1143z1/RAND_WR1143z1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18. RAND Coorperation IFLS data and documentation, 2019. Available: https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/data/FLS/IFLS/download.html [Accessed 31 Jul 2019].

- 19. Strauss J, Witoelar F, Sikoki B, et al. . User’s Guide for the Indonesia Family Life Survey, Wave 5. RAND, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Onis M, et al. Development of a who growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:660–7. 10.2471/BLT.07.043497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr 2006;450:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumanyika S, Jeffery RW, Morabia A, et al. . Obesity prevention: the case for action. Int J Obes 2002;26:425–36. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vandenbroeck P, Goossens J, Clemens M. Tackling obesities: future choices – building the obesity system map.. London, UK: UK Government Office for Science; 2007. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/295154/07-1179-obesity-building-system-map.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. 10.1093/aje/kwh090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mendez MA, Monteiro CA, Popkin BM. Overweight exceeds underweight among women in most developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:714–21 http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/81/3/714.full.pdf 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaacks LM, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Recent underweight and overweight trends by rural-urban residence among women in low- and middle-income countries. J Nutr 2015;145:352–7. 10.3945/jn.114.203562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roemling C, Qaim M. Obesity trends and determinants in Indonesia. Appetite 2012;58:1005–13. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Susilowati D. The relationship between overweight and socio demographic status among adolescent girls in Indonesia. Bul Penelit Sist Kesehat 2011;14. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sari K, Female MM. Live in urban, and the existence of a caregiver increased risk overnutrition in elderly: an Indonesian national study 2010. Heal Sci J Indones 2012;3:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Diana R, Yuliana I, Yasmin G, et al. . Risk factors of overweight among Indonesian women. J Gizi dan Pangan 2013;8:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kennedy G, Nantel G, Shetty P. Globalization of food systems in developing countries: a synthesis of country case studies. 83 Rome, Italy: FAO, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, et al. . Increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health: evidence from Brazil. Public Health Nutr 2010;14:5–13. 10.1017/S1368980010003241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popkin BM, Conde W, Hou N, et al. . Is there a lag globally in overweight trends for children compared with adults? Obesity 2006;14:1846–53. 10.1038/oby.2006.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Popkin BM. Urbanization, lifestyle changes and the nutrition transition. World Dev 1999;27:1905–16. 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00094-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. UNESCO Institute for Statistics Educational attainment, at least completed upper secondary, population 25+, 2016. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.CUAT.UP.FE.ZS [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones-Smith JC, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, et al. . Cross-National comparisons of time trends in overweight inequality by socioeconomic status among women using repeated cross-sectional surveys from 37 developing countries, 1989-2007. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:667–75. 10.1093/aje/kwq428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones-Smith JC, Gordon-Larsen P, Siddiqi A, et al. . Is the burden of overweight shifting to the poor across the globe? Time trends among women in 39 low-and middle-income countries (1991–2008). Int J Obes 2012;36:1114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Masood M, Reidpath DD. Effect of national wealth on BMI: an analysis of 206,266 individuals in 70 low-, middle- and high-income countries. PLoS One 2017;12:e0178928 10.1371/journal.pone.0178928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Monteiro CA, Moura EC, Conde WL, et al. . Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: a review. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:940–6. doi:/S0042-96862004001200011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lipoeto NI, Wattanapenpaiboon N, Malik A, et al. . Nutrition transition in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2004;13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oddo VM, Bleich SN, Pollack KM, et al. . The weight of work: the association between maternal employment and overweight in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14 10.1186/s12966-017-0522-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oddo VM, Mueller NT, Pollack KM, et al. . Maternal employment and childhood overweight in low- and middle-income countries. Public Health Nutr 2017;20:2523–36. 10.1017/S1368980017001720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Monda KL, Gordon-Larsen P, Stevens J, et al. . China's transition: the effect of rapid urbanization on adult occupational physical activity. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:858–70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. . Trends over 5 decades in U.S. Occupation-Related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS One 2011;6:e19657 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deierlein AL, Siega-Riz AM, Adair LS, et al. . Effects of pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on infant anthropometric outcomes. J Pediatr 2011;158:221–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Skilton MR, Siitonen N, Würtz P, et al. . High birth weight is associated with obesity and increased carotid wall thickness in young adults: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:1064–8. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yu Z, Han S, Zhu J, et al. . Pre-pregnancy body mass index in relation to infant birth weight and offspring overweight/obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e61627 10.1371/journal.pone.0061627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Whitaker KL, Jarvis MJ, Beeken RJ, et al. . Comparing maternal and paternal intergenerational transmission of obesity risk in a large population-based sample. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1560–7. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Murrin CM, Kelly GE, Tremblay RE, et al. . Body mass index and height over three generations: evidence from the Lifeways cross-generational cohort study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:81 10.1186/1471-2458-12-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM, Catalano PM. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:964–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev 2013;14:159–68. 10.1111/obr.12098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. World Cancer Research Fund International NOURISHING framework, 2018. Available: http://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-framework [Accessed 26 Mar 2019].

- 53. Grogger J. Soda taxes and the prices of sodas and other drinks: evidence from Mexico. Am J Agric Econ 2017;99:481–98. 10.1093/ajae/aax024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Colchero MA, Rivera-Dommarco J, Popkin BM, et al. . In Mexico, evidence of sustained consumer response two years after implementing a sugar-sweetened beverage Tax. Health Aff 2017;36:564–71. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. An R. Effectiveness of subsidies in promoting healthy food purchases and consumption: a review of field experiments. Public Health Nutr 2013;16:1215–28. 10.1017/S1368980012004715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee Y, Yoon J, Chung S-J, et al. . Effect of TV food advertising restriction on food environment for children in South Korea. Health Promot Int 2013;32:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mhurchu C, Eyles H, Choi Y-H. Effects of a voluntary front-of-pack nutrition labelling system on packaged food reformulation: the health StAR rating system in New Zealand. Nutrients 2017;9:918 10.3390/nu9080918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, et al. . Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17:95–107. 10.1111/obr.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, et al. . Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med 1997;337:869–73. 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Burford BJ, et al. . Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Libr 2011;165 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Salam RA, Hooda M, Das JK, et al. . Interventions to improve adolescent nutrition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:S29–S39. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031198supp001.pdf (368.3KB, pdf)