Abstract

β-Blockers’ heart rate (HR)-lowering effect is an important determinant of the effectiveness for this class of drugs, yet it is variable among β-blocker–treated patients. To date, genetic studies have revealed several genetic signals associated with HR response to β-blockers. However, these genetic signals have not been consistently replicated across multiple independent cohorts. Here we sought to use data from 3 hypertension clinical trials to validate single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) previously associated with the HR response to β-blockers. Using linear regression analysis, we investigated the effects of 6 SNPs in 3 genes, including ADRB1, ADRB2, and GNB3, relative to the HR response following β-blocker used in the PEAR (n = 757), PEAR-2 (n = 368), and INVEST (n = 1401) trials, adjusting for baseline HR, age, sex, and ancestry. Atenolol was used in PEAR and INVEST, and metoprolol was used in PEAR-2. We found that rs1042714 and rs1042713 in ADRB2 were significantly associated with HR response to both β-blockers in whites (rs1042714 C-allele carriers, meta-analysis β = −0.95 beats per minute [bpm], meta-analysis P = 3×10−4; rs1042713 A-allele carriers, meta-analysis β = −1.15 bpm, meta-analysis P = 2×10−3). In conclusion,the results of our analyses provide strong evidence to support the hypothesis that rs1042714 and rs1042713 in the ADRB2 gene are important predictors of HR response to cardioselective β-blockade in hypertensive patient cohorts.

Keywords: Pharmacogenetics, β-blockers, atenolol, metoprolol, heart rate

Activation of the adrenergic nervous system is involved in the development and progression of multiple cardiovascular and related metabolic disorders.1,2 β-Adrenergic receptor blockers (β-blockers), which decrease activation of the adrenergic nervous system via antagonism of β-adrenergic receptors, are effective in reducing blood pressure (BP) and cardiovascular adverse outcomes among post–myocardial infarction and heart failure patients.3 Heart rate (HR)-lowering effects of β-blockers are also helpful for tachyarrhythmia management. For many years these agents have been the mainstay therapy for managing patients with angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and certain arrhythmias along with other cardiovascular diseases.4,5 Several studies have confirmed a substantial link between the HR-lowering effect of β-blockers and beneficial cardiovascular outcomes,3,6–8 which highlight the importance of HR-lowering effects for β-blockers’ efficacy.9,10

Despite the general effectiveness of β-blockers, there are interindividual differences in their HR-lowering response.11,12 This variability in HR response has been attributed, in part, to genetics.13 Although most studies to date focused on uncovering the genetic contributions of β-blocker–related phenotypes such as BP lowering and cardiovascular outcomes, few have focused on the pharmacogenetic determinants of the HR-lowering effect of β-blockers. Additionally, although several genetic signals have been suggested as predictors of HR response to β-blockers, consistent replication and validation of these genetic signals in large well-designed studies have been lacking. This lack of replication is considered 1 of the reasons behind the slow adoption of β-blockers pharmacogenomics in clinical practice. To address this knowledge gap, we investigated the association between HR response to cardio-selective β-blockade and genetic variants previously linked with HR response to β-blockers using data from 3 trials of different patients cohorts.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

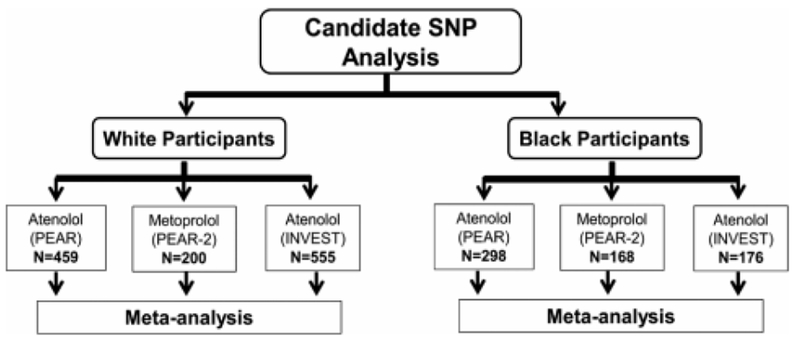

The clinical data and biological samples used in this study were obtained from the following 3 clinical trials. The protocol of each of the studies included in this analysis (see Figure 1) was approved by the institutional review board at each study site, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Figure 1.

The overall analysis framework of the study. INVEST indicates International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study; PEAR, Pharmacogenomics Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses; PEAR-2, Pharmacogenomics Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses-2.

PEAR Study.

The rationale, design, protocol, and safety procedures of the PEAR (Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses) study (ClinicalTrials.gov #) have been previously published in detail.14 PEAR was a prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial that was performed to investigate the effect of genetics on the BP response and adverse metabolic events of a β-blocker (ie, atenolol) and a thiazide diuretic (ie, hydrochlorothiazide). PEAR included 768 individuals with mild to moderate essential hypertension who had 4-6 weeks of washout period followed by the initiation of either 50 mg per day of atenolol or 12.5 mg of hydrochlorothiazide daily. After 3 weeks of monotherapy, participants with systolic BP (SBP) >120 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) >70 mm Hg had to double their dose (100 mg of atenolol or 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide) for 6 additional weeks. Of note, more than 85% of atenolol-treated participants had their dose increased to 100 mg per day (Table 1). Responses to each therapy were then evaluated after 6-9 weeks of monotherapy. For those who did not achieve their target BP goal, the alternate drug was added to their original therapy, with the same strategy for dose titration and assessment of HR response after 6-9 weeks of combined therapy. HR response was calculated for each participant and was used to guide dose adjustments in which participants with HR less than 55 beats/min (bpm) did not receive a higher dose of atenolol.

Table 1.

Baselineics Demographics of β-Blocker–Treated in PEAR and PEAR-2

| PEAR Atenolol (N = 757) |

PEAR-2 Metoprolol (N = 368) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Whites (n = 459) | Blacks (n = 298) | Whites (n = 200) | Blacks (n = 168) |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 49.8 ± 9.5 | 47.3 ± 8.7 | 51.0 ± 8.9 | 50.0 ± 9.2 |

| Women, N (%) | 198 (43.1) | 199 (66.8) | 90 (45.0) | 89 (53.0) |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 30.3 ± 5.2 | 31.6 ± 6.3 | 30.8 ± 5.1 | 30.8 ± 5.1 |

| β-blocker, N (%) | ||||

| 50 mg per day | 64 (14) | 30 (10) | … | … |

| 100 mg per day | 395 (86) | 268 (90) | 8 (4) | 9 (5.4) |

| 100 mg twice daily | … | … | 192 (96) | 159 (94.6) |

| Pretreatment HR, mean ± SD, bpm | 77.1 ± 9.5 | 79.9 ± 9.2 | 77.7 ± 9.6 | 79.8 ± 9.5 |

| Change in HR, mean ± SD, bpm | −13.1 ± 5.8 | −11.1 ± 7.1 | −12.3 ± 7.2 | −11.1 ± 7.0 |

BMI indicates body mass index; HR, heart rate; PEAR, Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses.

PEAR-2 Study.

PEAR-2 (Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses-2) was a prospective, multicenter, sequential monotherapy clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov #).15 After a 4-week washout period, mildly to moderately hypertensive participants (n = 368) started taking 50-mg doses of metoprolol tartrate twice daily for 2 weeks. BP response was calculated for each participant, and for those with a BP >120/70 mm Hg and HR >55 bpm after 2 weeks of therapy, dose was titrated to 100 mg twice daily for 6 more weeks. Importantly, more than 95% of metoprolol-treated participants had their doses increased to 100 mg twice daily (Table 1).

INVEST Study.

INVEST (International Verapamil and Trandolapril Study) was a multicenter trial that included >22,000 patients and investigated differences in cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease. Patients were randomized to either β-blocker strategy (β-blocker; atenolol) or calcium antagonist strategy (verapamil).16 In brief, patients received the study drug in each arm and were titrated to a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg according to the study protocol, as previously mentioned.17 Additional drugs included trandolapril, hydrochlorothiazide, and other antihypertensive medications if needed. Mean follow-up was 2.7 years. For the analysis of the current study, we included patients in the atenolol arm who received 50 mg/day or 100 mg/day of atenolol monotherapy. INVEST-GENES is a genetic substudy of INVEST in which genetic material was collected from 5979 patients in the United States.18 Of those, 1401 patients received atenolol monotherapy and were included in this study. More than 95% of INVEST-GENES patients included in this study received a 50-mg dose of atenolol per day (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics of Atenolol Therapy–Treated Participants in INVEST

| Characteristics | Whites (n = 555) | Blacks (n = 176) | Hispanics (n = 670) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 67.6 ± 9.1 | 62.8 ± 9.2 | 64.7 ± 9.8 |

| Women, N (%) | 236 (42.5) | 121 (68.8) | 433 (64.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29.0 (5.4) | 32.8 (6.7) | 29 (5.1) |

| Atenolol, N (%) | |||

| 50 mg per day | 532 (95.9) | 166 (94.9) | 645 (96.8) |

| 100 mg per day | 23 (4.1) | 9 (5.1) | 21 (3.2) |

| Pretreatment HR, mean ± SD, bpm | 75.0 ± 9.4 | 76.7 ± 9.3 | 73.6 ± 9.4 |

| Change in HR, mean ± SD, bpm | −6.9 ± 10.6 | −4.4 ± 10.9 | −3.9 ± 10.7 |

BMI indicates body mass index; HR, heart rate; INVEST, International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study.

Assessment of Heart Rate

For participants within PEAR and PEAR-2 studies, HR was measured using home BP monitors, as previously discussed.14 In brief, the HR of each participant was measured in triplicate in the morning and evening. During the assessment visit, a total of 5 morning and evening recordings measured in the 7 days before the assessment visit was needed. Therefore, at least 30 HR recordings were used for each participant to represent the HR values included in this study. Baseline HR represents HR measured at the end of the 4-week washout period. Atenolol HR response was measured 6-9 weeks after atenolol monotherapy (ie, atenolol monotherapy group) and 6-9 weeks following combination therapy (atenolol add-on therapy group). In PEAR-2, baseline HR was recorded after 4 weeks of washout, and HR response to metoprolol was recorded after 6-8 weeks of metoprolol therapy.

In INVEST, resting HR was measured in duplicate at baseline, before taking atenolol, and after 6 weeks of taking atenolol monotherapy.8 The average of the 2 HR readings was recorded, and the HR response to atenolol was calculated by subtracting baseline HR from postatenolol (monotherapy) HR.

Genetic Analyses

We conducted single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association analyses with HR response to β-blockade to validate 6 SNPs with previous literature documentation of effects on HR response to β-blockers (Table 3). These SNPs were selected from human genetic association studies published before May 2018, inclusive of studies that evaluated resting and exercise HRs as well as HR variability and recovery during β-blocker therapy. Surveyed databases included Pubmed, Web of Knowledge, and Embase. In both PEAR and PEAR-2, genome-wide genotyping data were available, and genotype information for these SNPs was extracted. In PEAR, participants underwent genotyping using Illumina Human Omni-1Million Quad BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, California). PEAR genotype and phenotype data have been made publicly available at the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000649.v1.p1; dbGaP study accession: phs000649.v1.p1). In PEAR-2, participants were genotyped using Human Omni2.5 S BeadChip (Illumina). SNP genotypes were called using GenTrain2 Illumina calling algorithm (Illumina). 1000 Genomes (phase I) imputed data from Minimac19 were used whenever directly genotyped data were not available. Quality control procedures were performed on both directly typed and imputed data before extracting the information for the evaluated SNPs, as previously described.20 The PEAR-2 genotype and phenotype data are currently in the process of being uploaded to dbGaP and will soon be available to other researchers under dbGaP accession phs000649.v2.p1.

Table 3.

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Previously Associated With Chronotropic Response to β-Blockers

| SNP | Gene | Variant Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs1801252 | ADRBI | Missense (A>G, Ser49Gly) | Cotarlan et al, 201312; Karlsson et al, 200434; Magnusson et al, 200535; Wilk et al, 200636 |

| rs1801253 | ADRBI | Missense (G>C, Arg389Gly) | Cotarlan et al, 201312; Kurnik et al, 200837; Liu et al, 200338 |

| rs1042714 | ADRB2 | Missense (C>G, Gln27Glu) | Cotarlan et al, 201312 |

| rs1042713 | ADRB2 | Missense (G>A, Arg16Gly) | Yang et al, 201139 |

| rs1800888 | ADRB2 | Missense (C>T, Thr16IIe) | Brodde et al, 200140; Turki et al, 199641 |

| rs5443 | GNB3 | Synonymous (C>T, Ser825Ser) | Dorr et al, 201042 |

SNP indicates single-nucleotide polymorphism.

In INVEST; patients were genotyped for the SNPs using pyrosequencing and TaqMan allelic discrimination techniques. The accuracy of the genotypes was confirmed by genotyping 5% to 10% duplicate samples on the alternate platform.21

Of note, PEAR-2 participants were taking meto-prolol oral dose, which is predominantly metabolized by the CYP2D6 enzyme. CYP2D6 SNPs were not evaluated in this study because we have previously investigated their impact on HR response to metoprolol in participants within PEAR-2, where we found a significant association between CYP2D6 SNPs and HR response to metoprolol.15 Atenolol is largely eliminated unchanged in urine, and thus, CYP2D6 SNPs were not evaluated for this drug in PEAR and INVEST.22

Statistical Analyses

We determined the HR response to β-blocker therapy by subtracting baseline HR from post–β-blocker treatment HR. The statistical genetic analyses were performed based on an additive genetic model that includes a common allele genotype group, a heterozygous variant carrier, and a homozygous variant carrier. A multivariable linear regression was used to test the association between each of the selected SNPs (as an independent variable) and β-blocker HR response (as a dependent variable), adjusting for baseline HR, age, differences in β-blocker dose, sex, and ancestry. A chi-squared test or Fisher exact test was used to evaluate SNP deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in each race separately. We used a Bonferroni-corrected threshold to adjust for multiple testing. For instance, a 2-sided P-value <.0083 (.05/6 tested SNPs) was used to identify the significance of the tested SNPs. Of note, each racial group was tested separately to prevent any confounding based on population stratification, which is particularly important here for the differences in the SNP frequencies among different ancestral populations. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS Inc, IBM, Armonk, New York). Additionally, we used METAL software23 to perform a meta-analysis among the 6 selected SNPs using data from PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST, assuming fixed effects and using inverse-variance weighting.

Results

The characteristics for PEAR participants treated with atenolol and PEAR-2 participants treated with metoprolol are summarized in Table 1. Baseline demographic variables including age, sex, body mass index, and baseline HR were not different between whites treated with β-blocker therapy in PEAR and PEAR-2. Similarly, baseline demographic variables (age, sex, body mass index, and baseline HR) were similar between blacks treated with β-blocker therapy in PEAR and PEAR-2. Baseline demographic characteristics for the INVEST cohort receiving atenolol monotherapy are presented in Table 2. INVEST included an elderly patient population with hypertension and documented coronary artery disease. Therefore, not surprisingly, INVEST participants were older and had a higher cardiovascular risk profile than the participants in PEAR and PEAR-2 studies.

Genetic Association Analyses

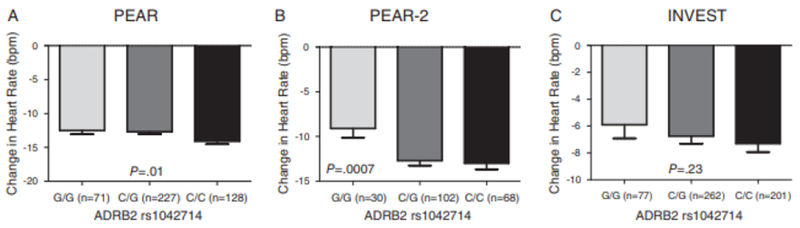

In whites, of the 6 SNPs previously associated with HR response to β-blockers (Table 3), only ADRB2 Gln27Glu (rs1042714) and ADRB2 Arg16Gly (rs1042713) were found to be significantly associated with the magnitude of HR reduction in participants treated with β-blockers, after adjusting for multiple comparisons. We found that participants who carry ADRB2 rs1042714 C-allele (allele that encodes the glutamine residue [Gln27]) had a better HR lowering response to atenolol (β = −0.83, P = .01, Figure 2A). This association was further confirmed in metoprolol-treated patients from PEAR-2, where C/C genotype had a better HR lowering response to metoprolol compared with C/G and G/G (β = −1.59, P = .0007, Figure 2B). The rs1042714 SNP had a consistent direction for HR lowering effect in INVEST patients treated with atenolol, as in PEAR and PEAR-2, which trended toward significance (β = −0.67, P = .23, Figure 2C). The association became stronger on meta-analyzing PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST (meta-analysis-P = .0003, Table 4).

Figure 2.

Effect of rs1042714 polymorphism on β-blockers’ heart rate response in whites within PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST studies. A, In PEAR atenolol-treated participants. B, In PEAR-2 metoprolol-treated participants. C, In INVEST atenolol-treated participants. HR response was adjusted for age,sex,and baseline HR. Two-sided P values represented are for contrast of adjusted means between different genotype groups. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. ADRB2 indicates β2-adrenergic receptor; HR, heart rate; INVEST, International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study; PEAR, Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses.

Table 4.

Association Among the 6 Candidate Polymorphisms Selected and β-Blocker HR-Lowering Response in PEAR and PEAR-2 White and Black Participants

| SNP | Gene | A1 | PEAR Atenolol | PEAR-2 Metoprolol | INVEST Atenolol | Meta-Analysis P-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | ||||||

| rs1801252 A>G | ADRBI | G | β = 0.01, P = .98 | β = 0.12, P = .89 | β = −0.87, P = .32 | β = −0.14, P = .73 |

| rs1801253 G>C | ADRBI | C | β = 0.57, P = .14 | β = 0.48, P = .94 | β = −0.09, P = .88 | β = 0.32, P = .28 |

| rs1042714 C>G | ADRB2 | C | β = −0.83, P = .01 | β = −1.59, P = 0.0007 | β = −0.67, P = .23 | β = −0.95, P = .0003 |

| rs1042713 G>A | ADRB2 | A | β = −0.70, P = .04 | β = −0.78, P = .19 | β = −1.15, P = .03 | β = −0.76, P = .002 |

| rs1800888 C>T | ADRB2 | T | β = −1.28, P = .65 | β = 1.43, P = 0.55 | β = 0.36, P = .91 | β = 0.33, P = .83 |

| rs5443 C>T | GNB3 | T | β = −0.48, P = .18 | β = −0.92, P = .12 | β = 0.96, P = .38 | β = 0.01, P = .95 |

| Blacks | ||||||

| rs1801252 A>G | ADRBI | G | β = 1.20, P = .06 | β = −0.11, P = .89 | β = 0.17, P = .89 | β = 0.63, P = .18 |

| rs1801253 G>C | ADRBI | C | β = −0.12, P = .84 | β = −0.57, P = .44 | β = −0.37, P = .73 | β = −0.31, P = .46 |

| rs1042714 C>G | ADRB2 | G | β = 0.38, P = .63 | β = 0.81, P = .39 | β = −0.27, P = .83 | β = 0.39, P = .47 |

| rs1042713 G>A | ADRB2 | A | β = 0.14, P = .81 | β = −0.07, P = .93 | β = 1.31, P = .20 | β = 0.26, P = .53 |

| rs1800888 C>T | ADRB2 | T | β = −0.04, P = .99 | β = −5.23, P = .24 | NA,b NAb | β = −0.15, P = .82 |

| rs5443 C>T | GNB3 | T | β = −0.75, P = .25 | β = −0.56, P = .50 | β = 2.69, P = .25 | β = −0.52, P = .30 |

A1 indicates coded allele; HR, heart rate; INVEST, International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study; PEAR, Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

A meta-analysis was performed among PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST, assuming fixed effects and using inverse-variance weighting.

NA indicates not available because the minor allele was absent in the tested population.

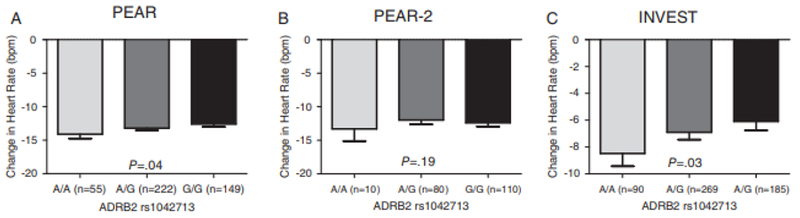

We also found a significant association in whites between ADRB2 rs1042713 and β-blocker HR response. PEAR participants carrying the A-allele (allele that encodes the arginine [Arg16] residue) had a better HR-lowering response to atenolol than the G-allele carriers (β = −0.7, P = .04; Figure 3). This association was further confirmed in INVEST, where the A/A genotype carriers had a better HR-lowering response to atenolol than A/G and G/G genotype carriers (β = −1.15, P = .03; Figure 3), consistent with an additive model. A trend toward significance was observed in metoprolol-treated participants in PEAR-2 in which rs1042713 A-allele carriers had a better HR-lowering response to metoprolol (β = −0.78, P = .19; Figure 3). The association became stronger on meta-analyzing PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST (meta-analysis P = .002; Table 4). Neither rs1042714 nor rs1042713 was significantly associated with the β-blocker’s HR-lowering response in blacks (Table 4) or Hispanics in INVEST (rs1042713, P = .17, rs1042714; P = .54). Additionally, none of the other evaluated SNPs met the significance threshold.

Figure 3.

Effect of rs1042713 polymorphism on β-blockers’ heart rate response in white participants within PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST studies. A, In PEAR atenolol-treated participants. B, In PEAR-2 metoprolol-treated participants. C, In INVEST atenolol-treated participants. HR response wasadjusted for age, sex, and baseline HR. Two-sided P values represented are for contrast of adjusted means between different genotype groups. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. ADRB2 indicates β2-adrenergic receptor; HR, heart rate; INVEST, International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study; PEAR, Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses.

Discussion

β-blockers are among the most frequently used drug classes and have been prescribed for many years to treat various cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension, heart failure, and angina.4,24 The HR-lowering effect of β-blockers is important for their efficacy and contributes considerably toward their clinical benefit for several cardiovascular conditions including myocardial infarction, angina, and heart failure.9,10,25 However, considerable interpatient variability in HR response to β-blockers has been reported,11,12 which indicates that a considerable proportion of β-blocker–treated patients do not achieve the warranted cardioprotection with β-blockers. This highlights the importance of identifying biomarkers associated with variability in HR response to β-blockers to improve the current approach for β-blocker selection, which seems to be suboptimal.

Despite the growing literature evidence showing the significant influence of genetics on HR,26,27 the replication/validation of identified genetic associations is lacking, which has hindered adoption of β-blocker pharmacogenomics in clinical practice. Therefore, we sought to validate previously reported genetic signals for the negative chronotropic response to β-blockade, namely, common SNPs in genes coding for β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors (ie, ADRB1, ADRB2), and guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G protein) β polypeptide subtype 3 (GNB3), in 3 independent well-designed clinical trials (PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST) using selective β1-receptor blockade.

Our analyses, in multiple cohorts, confirmed the association with the negative chronotropic response for 2 of 6 SNPs evaluated in atenolol- or metoprolol-treated patients. The rs1042713 and rs1042714 SNPs in ADRB2 were consistently associated with HR reduction in response to β-blocker therapy in whites from PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST. We found that PEAR participants carrying the rs1042713 A/A genotype (Arg16Arg) had a better HR-lowering response to β-blocker therapy compared with A/G (Arg16Gly) and G/G (Gly16Gly) genotype carriers. We also found that individuals with the rs1042714 C/C genotype carriers (Gln27Gln) had a better HR-lowering response to β-blocker compared with those with the G/C (Glu27Gln) and G/G (Glu27Glu) genotypes. This latter finding is consistent with the results reported by Cotarlan et al in which the rs1042714 G-allele carriers were less responsive to the HR-lowering effect of metoprolol compared with noncarriers. The study by Cotarlan et al have also highlighted rs1042714 SNP as an independent predictor of suboptimal HR.12

Altogether, the significant associations between rs1042713 and rs1042714 with changes in HR response to atenolol and metoprolol highlight the influence of the ADRB2 gene on the HR-lowering mechanism of those drugs. Although both atenolol and metoprolol are considered ADRB1 selective, the observed association between HR response and ADRB2 in atenolol- and metoprolol-treated participants could be explained by the fact that this selectivity may be attenuated with high concentrations of these drugs, which may antagonize ADRB2.28 It is possible that the nonsignificant association of rs1042714 with HR reduction in INVEST could be attributed to differences in atenolol dose between PEAR and INVEST. It is important to note that the majority of INVEST patients (>90%) included in this analysis received an atenolol dose of 50 mg. This was likely related to the fact that INVEST was designed to test a multidrug strategy using 2-3 or more antihypertensive drugs to investigate clinical outcomes.

ADRB2 is highly expressed in a wide variety of tissues including cardiac, vascular smooth muscle, and respiratory smooth muscle cells. The ADRB2s have an important regulatory role in the cardiac, vascular, respiratory, and endocrine systems.5,29 Both rs1042713 and rs1042714 are common nonsynonymous SNPs that affect the protein expression of ADRB2.30 Previous in vitro studies have shown that rs1042713 G-allele (encodes for gly16 residue and was associated with worse HR in response to β-blockers in this study) enhanced the agonist-stimulated downregulation of β2-adrenergic receptor.31,32 This indicates that rs1042713 patients with the G-allele may already have down-regulated β2-adrenergic receptor compared with A-allele carriers, which may explain the reason for a better HR-reduction response to β-blockers among individuals carrying the A-allele. Data from previous studies have documented the association between the ADRB2 rs1042714 C-allele (encodes Gln27 and was associated with better HR-lowering effect in response to β-blockers in this study) and increases in systolic blood pressure.33

One of the strengths of this study is the consistent effect of the ADRB2 SNPs on changes in HR, across 3 independent cohorts, with 2 β-blockers (atenolol and metoprolol) being used for BP control (PEAR and PEAR-2) and other cardiovascular indications such as coronary artery disease (INVEST), emphasizing involvement of the ADRB2 gene in mechanisms underlying the HR-lowerung effect of β-blockers. Our study has some limitations that are worth mentioning. First, the small sample sizes used for genetic analyses may have limited our power to replicate some of our genetic signals. In addition to that, the resting HR was used as an end point for medication titration instead of the exercise HR. However, clinically, titration of the β-blocker dose is carried out based on resting HR and BP responses, which reveal that resting HR is the more clinically relevant phenotype. Moreover, we have previously found a significant association between CYP2D6 SNPs and HR response to metoprolol15; however, this study did not investigate the effect of CYP2D6 SNPs genotype on the ADRB2 rs1042714 and rs1042713 genetic association with HR response to metoprolol because we did not have CYP2D6 genotyping data on all the metoprolol-treated participants included in our analysis. Last, different β-blocker doses were used across the studies. For instance, more than 85% of PEAR participants included in the current study were taking 100 mg/day of atenolol compared with >95% of participants who were on 50 mg/day of atenolol in INVEST. Nevertheless, the consistent effect across 3 cohorts found for 2 SNPs in ADRB2, regardless of dose, is compelling. Of note, we adjusted for differences in β-blocker dose in our regression analyses to overcome any confounding effects that could have arisen from the use of different doses of atenolol in PEAR or INVEST.

Conclusions

The results of this study validate the association of the rs1042713 and rs1042714 SNPs, in ADRB2, with the negative chronotropic response to β-blockade (atenolol and metoprolol) by replicating their effects in 3 well-designed clinical trials. Perhaps in the future, as we move toward a personalized medicine approach, the genetic signals identified in this study may be of help in guiding the selection of β-blockers and optimizing their use.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants enrolled in the PEAR, PEAR-2, and INVEST studies. We also acknowledge the valuable support of the staff and study physicians in each of these studies.

Funding

PEAR and PEAR-2 were supported by the National Institutes of Health Pharmacogenetics Research Network grant U01 GM074492 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under the award numbers UL1 TR000064 (University of Florida), UL1 TR000454 (Emory University), and UL1 TR000135 (Mayo Clinic). Funds from the Mayo Foundation also supported the PEAR study. INVEST was supported by grants from the University of Florida Opportunity Fund and Abbott Pharmaceuticals. INVEST-GENES was supported by National Institutes of Health grants (U01 GM074492 and R01 HL074730). D.G. receives support for research from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD083465).

Footnotes

Data Sharing

PEAR and PEAR-2 genomics and phenotype data are publicly available at the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap)

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Ciccarelli M, Santulli G, Pascale V, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. Adrenergic receptors and metabolism: role in development of cardiovascular disease. Front Physiol. 2013;4:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lymperopoulos A, Rengo G, Koch WJ. Adrenergic nervous system in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2013;113(6):739–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAlister FA, Wiebe N, Ezekowitz JA, Leung AA, Armstrong PW. Meta-analysis: beta-blocker dose, heart rate reduction, and death in patients with heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(11):784–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollenberg NK. The role of β-blockers as a cornerstone of cardiovascular therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(12 Pt 2):165S–168S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin J, Johnson JA. β-Blocker pharmacogenetics in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;15(3):187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cucherat M Quantitative relationship between resting heart rate reduction and magnitude of clinical benefits in post-myocardial infarction: a meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(24):3012–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flannery G, Gehrig-Mills R, Billah B, Krum H. Analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of magnitude of heart rate reduction on clinical outcomes in patients with systolic chronic heart failure receiving beta-blockers. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(6):865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolloch R, Legler UF, Champion A, et al. Impact of resting heart rate on outcomes in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: findings from the INternational VErapamil-SR/trandolapril STudy (INVEST). Eur Heart J. 2008;29(10):1327–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okin PM, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Hille DA, Dahlof B, Devereux RB. Effect of changing heart rate during treatment of hypertension on incidence of heart failure. Am JCardiol. 2012;109(5):699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan JR, Manuck SB, Adams MR, Weingand KW, Clarkson TB. Inhibition of coronary atherosclerosis by propranolol in behaviorally predisposed monkeys fed an atherogenic diet. Circulation. 1987;76(6):1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotarlan V, Brofferio A, Gerhard GS, Chu X, Shirani J. Impact of β1- and β2-adrenergic receptor gene single nucleotide polymorphisms on heart rate response to metoprolol prior to coronary computed tomographic angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(5):661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrashevskaya NN, Koch SE, Bodi I, Schwartz A. Calcium cycling, historic overview and perspectives. Role for autonomic nervous system regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(8):885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JA, Boerwinkle E, Zineh I, et al. Pharmacogenomics of antihypertensive drugs: rationale and design of the Pharmacoge-nomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses (PEAR) study. Am Heart J. 2009;157(3):442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamadeh IS, Langaee TY, Dwivedi R, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on clinical efficacy and tolerability of metoprolol tartrate. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(2):175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(21):2805–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepine CJ, Handberg-Thurmond E, Marks RG, et al. Rationale and design of the International Verapamil SR/Trandolapril Study (INVEST): an internet-based randomized trial in coronary artery disease patients with hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(5):1228–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beitelshees AL, Gong Y, Wang D, et al. KCNMB1 genotype influences response to verapamil SR and adverse outcomes in the INternational VErapamil SR/Trandolapril STudy (INVEST). Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17(9):719–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):955–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahin MH, Conrado DJ, Gonzalez D, et al. Genome-wide association approach identified novel genetic predictors of heart rate response to β-blockers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pacanowski MA, Gong Y, Cooper-Dehoff RM, et al. β-Adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms and β-blocker treatment outcomes in hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(6):715–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bijl MJ, Visser LE, van Schaik RHN, et al. Genetic variation in the CYP2D6 gene is associated with a lower heart rate and blood pressure in β-blocker users. Clinical Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(1):45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.IMS Institute. Medicines use and spending in the U.S. A review of 2015 and outlook to 2020. http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/medicines-use-and-spending-in-the-us-a-review-of-2015-and-outlook-to-2020. Accessed February 7, 2017.

- 25.Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. β Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ. 1999;318(7200):1730–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eppinga RN, Hagemeijer Y, Burgess S, et al. Identification of genomic loci associated with resting heart rate and shared genetic predictors with all-cause mortality. Nat Genet. 2016;48(12):1557–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.den Hoed M, Eijgelsheim M, Esko T, et al. Identification of heart rate-associated loci and their effects on cardiac conduction and rhythm disorders. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):621–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zebrack JS, Munger M, Macgregor J, Lombardi WL, Stod-dard GP, Gilbert EM. β-receptor selectivity of carvedilol and metoprolol succinate in patients with heart failure (SELECT trial): a randomized dose-ranging trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor MR. Pharmacogenetics of the human beta-adrenergic receptors. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7(1):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litonjua AA, Gong L, Duan QL, et al. Very important pharmacogene summary ADRB2. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20(1):64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green SA, Turki J, Innis M, Liggett SB. Amino-terminal polymorphisms of the human beta 2-adrenergic receptor impart distinct agonist-promoted regulatory properties. Biochemistry. 1994;33(32):9414–9419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green SA, Turki J, Bejarano P, Hall IP, Liggett SB. Influence of beta 2-adrenergic receptor genotypes on signal transduction in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13(1):25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallerstedt SM, Eriksson AL, Ohlsson C, Hedner T. Hap-lotype association analysis of the polymorphisms Arg16Gly and Gln27Glu of the adrenergic β2 receptor in a Swedish hypertensive population. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19(9):705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson J, Lind L, Hallberg P, et al. Beta(1)-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms and response to betal(1)-adrenergic receptor blockade in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(6):347–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnusson Y, Levin MC, Eggertsen R, et al. Ser49Gly of beta(1)-adrenergic receptor is associated with effective beta-blocker dose in dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(3):221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilk JB, Myers RH, Pankow JS, et al. Adrenergic receptor polymorphisms associated with resting heart rate: the HyperGEN study. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurnik D, Li C, Sofowora GG, et al. Beta-1-adrenoceptor genetic variants and ethnicity independently affect response to beta-blockade. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18(10):895–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Liu ZQ, Tan ZR, et al. Gly389Arg polymorphism of beta(1)-adenergic receptor is associated with the cardiovascular response to metoprolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(4):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang AC, Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, et al. Clustering heart rate dynamics is associated with beta-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms: analysis by information-based similarity index. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodde OE, Buscher R, Tellkamp R, Radke J, Dhein S, Insel PA. Blunted cardiac responses to receptor activation in subjects with Thr164Ile beta(2)-adrenoceptors. Circulation. 2001;103(8):1048–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turki J, Lorenz JN, Green SA, Donnelly ET, Jacinto M, Liggett SB. Myocardial signaling defects and impaired cardiac function of a human beta 2-adrenergic receptor polymorphism expressed in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(19):10483–10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorr M, Schmidt CO, Spielhagen T, et al. beta-blocker therapy and heart rate control during exercise testing in the general population: role of a common G-protein beta-3 subunit variant. Pharmacogenomics.2010;11(9):1209–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]