Gliomas represent the most common brain tumor type. Molecular and global omics are becoming powerful tools for tumor subclassification that will facilitate more subtype-specific treatment options for patients. Here, we demonstrate that proteomic-based subclassification of closely related gliomas, differentiated by IDH mutation and 1p19q chromosome codeletion status, is facilitated by tumor microdissections prior to mass spectrometry analysis. Identified protein modules are confirmed in tissue culture grown glioma stem cells and point to chloride transport and stress proteins as strong drivers of glioma molecular diversions.

Keywords: Tandem Mass Spectrometry, Glioblastoma, Subcellular Analysis, Cancer Biology, Cancer Biomarker(s)

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

LFQ-based protein patterns define glioma subgroups that correlate with genomic alterations.

Proteomic analysis resolves distinct pathway-level differences among glioma subtypes.

Distinct IDH subtype-specific tumor patterns are maintained in glioma stem cell cultures.

Abstract

Molecular characterization of diffuse gliomas has thus far largely focused on genomic and transcriptomic interrogations. Here, we utilized mass spectrometry and overlay protein-level information onto genomically defined cohorts of diffuse gliomas to improve our downstream molecular understanding of these lethal malignancies. Bulk and macrodissected tissues were utilized to quantitate 5,496 unique proteins over three glioma cohorts subclassified largely based on their IDH and 1p19q codeletion status (IDH wild type (IDHwt), n = 7; IDH mutated (IDHmt), 1p19q non-codeleted, n = 7; IDH mutated, 1p19q-codeleted, n = 10). Clustering analysis highlighted proteome and systems-level pathway differences in gliomas according to IDH and 1p19q-codeletion status, including 287 differentially abundant proteins in macrodissection-enriched tumor specimens. IDHwt tumors were enriched for proteins involved in invasiveness and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), while IDHmt gliomas had increased abundances of proteins involved in mRNA splicing. Finally, these abundance changes were compared with IDH-matched GBM stem-like cells (GSCs) to better pinpoint protein patterns enriched in putative cellular drivers of gliomas. Using this integrative approach, we outline specific proteins involved in chloride transport (e.g. chloride intracellular channel 1, CLIC1) and EMT (e.g. procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3, PLOD3, and serpin peptidase inhibitor clade H member 1, SERPINH1) that showed concordant IDH-status-dependent abundance differences in both primary tissue and purified GSC cultures. Given the downstream position proteins occupy in driving biology and phenotype, understanding the proteomic patterns operational in distinct glioma subtypes could help propose more specific, personalized, and effective targets for the management of patients with these aggressive malignancies.

Diffuse gliomas represent the most common intrinsic brain tumor type but, as a group, carry a remarkably variable clinical course (1–3). Some rapidly evolve, while others remain relatively stable for years before progression. Therefore, precise characterization of the unique biology of the different glioma subtypes is essential for personalized management. The current state-of-the-art classification system of adult gliomas relies on an integrated approach that incorporates histomorphologic and genomic features of malignancy. First, diffuse gliomas are subdivided into classes based on their microscopic resemblance to native astrocytes (astrocytomas) and/or oligodendrocytes (oligodendrogliomas). This is accompanied by quantifying features of aggressiveness including presence of nuclear atypia, proliferative activity, and necrosis and microvascular proliferation (World Health Organization (WHO)1 grades II-IV, respectively) (4). To combat subjective interobserver variability and more precisely resolve prognostically relevant subgroups, this microscopic exam is now supplemented with a handful of clinically relevant molecular alterations (5–8). Today, this primarily includes assessment of mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase genes (IDH1/2) and presence of 1p and 19q chromosomal arm codeletions (1p19q codel). Together, this integrated approach defines three major diffuse glioma subgroups: (i) IDH-wild-type (IDHwt) astrocytomas, (ii) IDH-mutated (IDHmt) astrocytomas, and (iii) IDHmt, 1p19q codeleted oligodendrogliomas (9–11). These distinct molecular groups are of tremendous clinical interest as they have both biological and prognostic significance. The vast majority of IDHwt astrocytomas represent glioblastomas (GBMs), that is, gliomas that show high-grade (WHO grade IV) features at presentation and arise de novo in older patients with no prior history of a lower-grade lesion. IDHmt gliomas, however, oftentimes arise as lower-grade tumors (WHO grades II-III) in younger individuals and eventually undergo secondary malignant transformation to higher-grade tumors (WHO grade III-IV) with time and eventually become GBM. While IDHmt gliomas share some clinical and biological similarities, such as arising in the frontal cortical brain regions of young adults, astrocytic lesions (1p19q non-codel) usually evolve into “secondary” GBM (WHO grade IV) and have an aggressive clinical course. IDHmt gliomas with 1p19q codeletions have distinct molecular drivers and follow a more indolent clinical course, even following transformation. Although more common in younger patients, circumscribed gliomas that lack brain infiltration, a key feature of WHO II-IV gliomas, also exist. One such entity, referred to as pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade I), is defined histomorphologically by piloid cytoplasmic processes, Rosenthal fibers, microvascular proliferation, and chronic inflammation. These tumors have quite distinct and recurring genomic alterations (BRAF duplications/fusions) that drive their distinct and more indolent biology.

Notwithstanding these significant milestones in our genome-level understanding and classification of diffuse gliomas, treatments between patients and even across molecular subgroups is relatively uniform, nonspecific, and ineffective (12, 13). The existing multiplatform genomic data (RNA, DNA-copy number, and DNA methylation), however, continue to support the hypothesis that diffuse glioma subtypes represent clinically and biologically nonoverlapping entities that could potentially benefit from more personalized management. For example, gliomas with concurrent alterations in IDH and 1p/19q appear to uniquely harbor inactivating mutations in CIC, FUBP1, and NOTCH1 and almost exclusively (95%) rely on TERT promoter mutations to regulate telomere lengthening. Conversely, almost all diffuse gliomas with IDH mutations that lack 1p/19q codeletion carry mutations in TP53 (94%) and depend on a distinct ATRX inactivation mechanism (86%) for telomere length maintenance. IDHwt gliomas also show unique biology with a high proportion of tumors relying on EGFR amplification, PTEN and CDKN2A inactivation, and TERT promoter mutations for their evolution (2).

Although proteomic patterns of tumors are often assumed to closely mirror their genomic landscapes, emerging studies now challenge this paradigm. Proteogenomic studies in colorectal (14), breast (15), and ovarian (16) cancer, which superimpose proteomic and genomic data, show that protein abundance cannot yet be accurately inferred from DNA or RNA measurements (r = 0.23–0.45). For example, although copy number alterations drive local (cis) mRNA changes, complex posttranscriptional regulation mechanisms do not guarantee these will translate to protein abundance changes. For example, in ovarian cancer, >200 protein aberrations were detected from genes at distant (trans) loci of copy number alterations and were shown to better predicted patient outcomes than their upstream mRNA levels. These discrepancies are further ominous, as KEGG pathway analysis implicates these protein-level differences in mediating important processes of malignancies such as invasion, cell migration, and immune regulation (16). In gliomas, Stetson and colleagues recently examined the levels of 171 proteins quantified by reverse-phase protein arrays across 203 IDHwt GBMs from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (17). Using these data, they developed a 13-protein signature that defined a novel cohort of patients with a significantly more favorable outcome not identified by TCGA's concurrent genomic efforts. These focused reverse-phase protein array-based panels are encouraging and suggest that additional important intra- and intersubtype-specific protein differences exist and await discovery. Studies using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) highlight a more global overview of proteins in GBM (4,576 proteins) but were derived from potentially heterogeneous bulk tissue samples and compared with control brain tissues rather than other glioma subtypes (18). Extension of such MS-based approaches to include macroscopically enriched tumor tissue from more diverse glioma subtypes offers an attractive avenue to carry out comparative proteomic studies and uncover targetable protein patterns and downstream pathway-level differences among molecular subtypes of gliomas.

Application of MS-based proteomic approaches to gliomas is not without its challenges. MS studies thus far have heavily relied on frozen tissue, which may often be limited from small GBM biopsy specimens. Similarly, the infiltrative nature of diffuse gliomas makes “bulk” expression-based profiling studies extremely difficult to interpret as they can be contaminated with large amounts of normal and necrotic tissue elements. Furthermore, laborious fractionation steps, to improve proteomic coverage, considerably compromises sample throughput and eventual clinical utility (15). To overcome these practical limitations and determine if and what proteome-level differences exist between diffuse glioma subtypes, we decided to use a recently validated FFPE-compatible LC-MS/MS workflow (19, 20). We previously showed that this approach can generate biologically relevant signatures from minute amounts of microscopically defined tissue, making it a useful tool to study regionally heterogeneous tissue types. Although this abbreviated approach is not designed to provide a comprehensive coverage of the proteome of profiled samples, it provides sufficient protein sequencing depth and more acceptable sample throughputs to resolve distinct pathways operational in different cellular compartments (19). Here, we extend this shotgun LC-MS/MS workflow to provide an overview of proteomic landscapes of genetically defined glioma subgroups. Importantly, we highlight pathway and individual protein-level differences in different glioma subtypes that are maintained in complementary glioma stem cell cultures, a larger publicly available genomic dataset, and by immunohistochemical staining. Together, our dataset, which helps nominate key macromolecules and processes that remain operational at multiple levels of glioma biology, provides a rich resource for hypothesis generation and in selection of robust therapeutic targets for these aggressive brain neoplasms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

We developed three unique glioma cohorts to interrogate protein-level differences of glioma biology (see supplemental Table 1 for clinical and molecular details). Briefly, our first cohort consisted exclusively of bulk fresh-frozen tissue of different glioma subtypes (n = 15, 14 of these were primary nonpreviously treated/recurring tumors). This included three pilocytic astrocytomas (pediatric, WHO grade I); two IDHwt astrocytomas (WHO grade IV); six IDHmt, 1p19q-codel oligodendrogliomas (WHO grade II-III); and four IDHmt, 1p19q non-codeleted astrocytomas (WHO grade II-IV). One of these later astrocytic cases (WHO grade III) was a recurrence of a previous lesion. Here, the pilocytic astrocytomas were meant to serve as neoplastic controls to avoid comparing protein profiles of the WHO II-III diffuse gliomas to non-neoplastic brain tissue. Our FFPE cohort similarly consisted of both glioma (e.g. three IDHmt, non-codel; four IDHmt, codel, and five IDHwt gliomas) and non-glioma control neoplastic specimens (e.g. meningioma and medulloblastoma). All gliomas in this cohort represented primary, nonrecurrent, untreated tumors. For statistical analyses, independent tumor samples were treated as biological replicates. Glioma samples were obtained from the Canadian Brain Tumor Foundation, international collaborators (Carlo Besta Neurological Institute) and in-house UHN tumor archive and were approved by UHN Research Ethics Board. In our experience, resected glioma tissue presents a unique challenge because it is often contaminated with vastly varying amounts of non-lesional tissue (whole slide tumor purity: 45%-95%; see supplemental Table 1). Therefore, while frozen tissue is often preferred for molecular analysis, the goal of the additional FFPE cohort was focused on assessing if potential glioma molecular subgroup differences are maintained in macrodissected-tumor-enriched regions free of large areas of potential confounding tissue elements between subgroups (e.g. necrosis, brain tissue). Careful macrodissection of these FFPE cases allowed us to reach more homogenous tumor purities (80%-95%; see supplemental Table 1 for pre- and postmacrodissection purity of each case). As it was impractical to remove all non-neoplastic tissue elements intermixed within the tumor tissue (vasculature and infiltrated brain), our final cohort consisted of GSC cultures and served to further validate if subtype-specific profiles identified in primary tumors were maintained in more purified populations of tumor cells. All cases were reviewed by at least two neuropathologists and additional ancillary molecular studies (e.g. immunostaining, sequencing, and cytogenetics) were used to appropriately group our cohort into the major genomically defined diffuse glioma subtypes for analysis (see supplemental Table 1; “Class for Analysis”).

GSC Culture Conditions

To study the protein patterns of more purified and controlled populations of glioma samples, we used three patient-derived cultures, either IDHwt (n = 2) and IDHmt (n = 1, recurrence) GSCs were grown in duplicate experiments as neurospheres in serum-free media containing EGF/FGF (21) (base media: DMEM/F12 media, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic, 1% l-glutamine, 0.2% B27) or as differentiated cells in serum-supplemented media (base media with 10% FBS) without growth factors for eight days. We reasoned this variable exposure to serum would help capture protein patterns of both precursor and more mature neoplastic cells known to heterogeneously comprise the tumor bulk. For sample collection (days 0 and 8), medium was withdrawn and cells washed twice with ice cold 1x PBS. Cells were either centrifuged (as undifferentiated) or scraped in lysis buffer (8 m urea, 0.05 m ammonium bicarbonate in ddH2O) and prepared for MS as described below.

Sample Preparation

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Plus high-resolution mass spectrometer as previously described (19). Briefly, for FFPE tissues, we prepared 10-μm thick sections on charged glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to highlight tumor regions free from contaminating surrounding brain tissue, hemorrhage, and tissue necrosis. Areas enriched in lesional tissue were carefully macrodissected off adjacent deeper slides with a scalpel, and proteins were prepared in MS-compatible cell lysis reagent (0.2% RapigestTM, Waters Corp.) by sonicating on ice for five cycles of 10 s each. Protein crosslinks were reversed by boiling (at 95 °C) in the presence of 5-μm DTT for 60 min followed by 80 °C for 90 min. Proteins were quantitated using Coomassie protein quantification assay (Pierce), and trypsin (Sigma) digestion was performed overnight at 37 °C. 15 μg of trypsin-digested peptides were cleaned in C18 tips for MS analysis. Fresh-frozen bulk tumors and tissue culture samples were processed identically but in 8 m urea lysis reagent without the 95 °C and 80 °C crosslink reversal step. Tissue lysates from each sample were processed in trypsin, and unfractionated digests were analyzed by LC-MS/MS to generate proteomic profiles. For all MS/MS experiments, LC and nanoelectrospray pump was used in a 120-min (fresh-frozen tumor and GSC samples) and 90-min (FFPE tumor samples) data-dependent acquisition program, and raw data files were searched using MaxQuant (version 1.5.5.1) Andromeda search engine (supplemental Table 11 describes sample identifiers used in raw MS files). Searches were performed against the Swiss-Prot database (www.uniprot.org July 2017 release, 41,345 protein entries). Search was performed for trypsin-digested peptides with two allowed missed cleavages permitted. Fixed modification of carbamidomethylation and variable modifications of oxidation (M) and acetylation (N-terminal) with precursor ion mass tolerance of 0.5 Da for precursor ions and 0.25 Da for fragment ions were defined for database searches. Peptide counts and peptide intensities are used to calculate total protein label-free quantification intensities for each protein group. PSM false discover rate (FDR), calculated by the target-decoy approach, was set at 0.01. Search output files have been uploaded to public repositories (see “Dataset Availability”), and tables of all identified proteins for the three datasets are included (supplemental Tables 2–4).

Label-Free Quantification MS

Each sample was concentrated using Omix C18 (Agilent Technologies) tips and eluted with 3 μl of buffer A (0.1% formic acid, 65% acetonitrile). To each sample, 57 μl of buffer B (0.1% formic acid) were added, of which 10 μl (1.5 μg of peptides) were loaded from a 96-well microplate autosampler onto a C18 trap column using the EASY-nLC1000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, California) and running Buffer C (0.1% formic acid). The trap column consisted of IntegraFrit capillary (inner diameter 75 μm, New Objective) cut to 3.2 cm in length and packed in-house with 5 μm Pursuit C18 (Agilent Technologies.). Peptides were eluted from the trap column at 300 nl/min with an increasing concentration of Buffer D (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) over a 120-min gradient onto a resolving 15-cm long PicoTip Emitter (75-μm inner diameter, 8-μm tip, New Objective) packed in-house with 3-μm Pursuit C18 (Agilent Technologies.). The liquid chromatography setup was coupled online to Q Exactive Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) mass spectrometer using a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with capillary temperature set to 275 °C and spray voltage of 2kV. A 120 or 90 min data-dependent acquisition method was run on the Q Exactive Plus. The full MS1 scan from 400–1,500 m/z was acquired in the Orbitrap at a resolution of 70,000 in profile mode with subsequent fragmentation of top 12 parent ions using the HCD cell and detection of fragment ions in the Orbitrap using centroid mode at a resolution of 17,500. The following MS method parameters were used: MS1 automatic gain control target was set to 3e6 with maximum injection time of 100 ms; MS2 automatic gain control was set to 5e4 with maximum injection time of 50 ms; isolation window was 1.6 Da; underfill ratio 2%; intensity threshold 2e4; normalized collision energy was set to 27; charge exclusion was set to fragment only 2+, 3+, and 4+ charge state ions; peptide match set to preferred; and dynamic exclusion set to 42 (for 90-min method) or 48 s (for 120-min method).

Biostatistical and Informatics Analysis

Raw data files were searched using MaxQuant Andromeda search engine (www.coxdocs.org) against the Human Swiss-Prot protein database (July 2017 version) using match between runs algorithm. Analysis of proteomic datasets was performed using biostatistics software platforms Perseus (www.coxdocs.org), R (www.r-project.org), and Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org). Label-free quantification intensity values were used to perform statistical analysis by filtering out protein IDs with less than 60% of samples containing a measurement and imputing the remaining missing values (width 0.42, downshift 1.78). Cellular components and biological processes were assessed by uploading gene names to DAVID functional annotation tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov). Pearson correlations were performed by omitting imputed values and using protein measurements found in 100% of the analyzed samples. For hierarchical clustering, protein measurements were Z-score transformed and plotted using complete Euclidean hierarchical clustering method with K-means preprocessing using either whole datasets or only statistically significant protein changes. Protein-level changes between glioma subgroups were determined by either modified Welch's Student's t test or multisample analysis of variance (ANOVA) using FDR adjustment of 0.1, as indicated. Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis was performed using the Fisher exact test with FDR cutoff of 0.02. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to define driver pathways within subgroups using the geneset permutation type with a weighted t test enrichment statistic of 0.1. Heatmaps and networks of the proteins in GSEA were visualized using Cytoscape.

Tissue Microarray and GBM Atlas RNAseq Database Analyses

In order to validate proteins expression patterns in an independent cohort of gliomas, we assembled and constructed a tissue microarray (TMA) of 22 nontreated primary glioma tissue samples (see supplemental Table 1 for clinical details). FFPE tissue arrays consisting of 3-mm cores (diameter) were sectioned to 5 μm in thickness, and slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Antigen retrieval was then performed in citrate dehydrate at pH of 6.0 by boiling in a pressure cooker for 20 min. Slides were then washed three times in PBS, and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min. Slides were then blocked for 1 h in 10% FBS, 0.1% Triton X-100. Antibody incubation was performed with Anti-PLOD3 antibody (Sigma, HPA001236) in the blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C followed by washing and incubation with anti-rabbit HRP secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. To further confirm our defined proteomic profiles, we leveraged the expansive glioma subtype cohorts of TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov) and Ivy GBM atlas project (http://glioblastoma.alleninstitute.org/) databases to validate our protein-based glioma signatures. These consisted of two independent datasets containing 421 glioma tumor samples (TCGA, oligodendroglioma (IDHmt, codel), astrocytomas (IDHmt, non-codel), and IDHwt GBMs) and laser capture microdissected intratumoral histologically defined features of 40 GBMs (Ivy GBM atlas). For this, we extracted RPKM RNAseq values for our differentially expressed proteins to perform hierarchical clustering and Spearman correlation coefficient calculations between our MS label-free quantification and RNAseq measurements.

RESULTS

Protein Patterns Define Glioma Subgroups That Correlate with Genomic Alterations

To determine if proteomic analysis can cluster gliomas into groups that correlate with established genomic subtypes, we first analyzed our developed FFPE (n = 15), frozen (n = 15), and GSC (n = 3) cohorts by LC-MS/MS (for full clinical details see supplemental Table 1) (Fig. 1A). Macrodissected FFPE tumor regions yielded ∼2,500 proteins comparable to ∼2,900 proteins per sample isolated from bulk fresh-frozen tumor and cultured precursor specimens, with significant overlaps in proteins IDs (Fig. 1B). Thus, we further confirmed that FFPE tissue proteomics, with slight technical modifications in sample preparations, can yield comparable MS-based proteomic datasets to their fresh-frozen tissue counterparts. In fact, the only distinguishing feature seemed to be the slightly larger percentage of proteins identified by single peptide hits (41% versus 32% in FFPE versus fresh-frozen tissue, respectively) (Fig. 1B). Altogether, we recovered 5,496 proteins from our integrated effort, producing the largest proteomic resource of gliomas to date and expanding on previous analysis of glioma tissues using MS (24) and MALDI MS (25) (Fig. 1B). Importantly, proteins derived from both biopsy sources had high degrees of similarity in molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

LC-MS/MS analysis of FFPE, bulk frozen tissues, and GSCs highlights subgroup-specific proteomic differences. (A) We profiled bulk frozen (n = 15) and macrodissected FFPE glioma tissues (n = 15) using Q Exactive LC-MS/MS. GSCs (n = 3), grown in duplicate, were profiled in the presence and absence of EGF/FGF (n = 12). (B) Raw MS datasets searched in Maxquant Andromeda search engine yielded on average ∼2,900, ∼2,400, and ∼2,950, quantified proteins per frozen, FFPE, and tissue culture samples, respectively. Bar graph illustrates quantified peptides/protein and Venn diagram illustrates overlaps of identified protein IDs, with 2,130 proteins measured across all three datasets. Venn diagram on the right indicates the overlap between our tissue datasets with previously published MS-based proteome characterizations. (C) DAVID analysis of the three datasets demonstrate an overall similarity in percentage of proteins localized to particular cellular components and involved in indicated biological processes. (D) Clustering based on global Pearson correlation coefficients demonstrate clustering of primary tumor samples largely based on WHO grade classification (grade I-IV) and IDH mutation status. Macrodissected FFPE tumors demonstrate slightly improved segregation of tumors according to IDH.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of Pearson correlations of protein intensities across samples in frozen and FFPE tumor cohorts found three major branches of proteomic patterns (Fig. 1D). In the frozen tissue cohort, pilocytic astrocytomas (WHO grade I) formed their own branch, with a separate branch of WHO grade II-IV IDHmt codel and non-codel gliomas. To validate and extend our findings, we performed a similar analysis using our macrodissected FFPE tissue cohort. In addition to a non-glioma cluster, IDHwt formed a distinct branch from IDHmt gliomas (1p19q-codel and non-codel). In both cohorts, this unsupervised analysis of the entire dataset highlighted that there are distinct protein pattern differences that closely reflect the well-understood histologic and molecular glioma subgroups.

Supervised Proteomic Analysis Resolves Distinct Pathway-Level Differences among Glioma Subtypes

To identify proteins and potential biological pathways driving clustering divergence between molecular subtypes of gliomas, we performed multisample ANOVA analysis in the two glioma datasets (Fig. 2A). In the bulk frozen tumor comparisons, major differences in protein abundance levels were due to highly distinct molecular landscape of pilocytic astrocytomas (486 proteins, FDR<0.1, supplemental Table 5). Hierarchical clustering of samples reinforced tumor-type-specific differences, where IDHwt gliomas clustered in their own node with a secondary bimodal node composed of pilocytic astrocytomas and an intermixed IDHmt branch of 1p19q codeleted and non-codeleted diffuse gliomas (Fig. 2A). Relative to the entire dataset of quantified proteins, these 486 protein groups are significantly enriched for the mitochondrion with biological functions of developmental growth, metabolism, and catabolic processes (Fisher exact test, FDR<0.1, supplemental Table 6). Biological processes enriched in each tumor molecular subgroups were investigated by defining four protein clusters: IDHwt diffuse glioma and pilocytic astrocytoma specific (cluster 1), IDHwt diffuse glioma exclusive (cluster 2), IDHmt (cluster 3), and IDHwt depleted (cluster 4). Only clusters 1 and 3 had statistically enriched GO biological processes (FDR<0.1, Table I). This analysis revealed that IDHwt tumors exhibit higher inflammatory response, whereas pilocytic astrocytomas were defined by elevated membrane invagination and endocytosis. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are a common and well-recognized phenomenon in lower-grade gliomas, highlighting the power of our analysis to capture heterogeneous biological elements and processes within profiled tissues. These pathway-level findings were further recapitulated when low-grade pilocytic astrocytomas (pilo) were compared with higher-grade tumors using the GSEA approach (supplemental Fig. 1). For example, pilocytic astrocytomas are represented by interferon proteins and, most notably, integrins and other proteins of the extracellular matrix and NABA matrisome pathway. In contrast, pilocytic astrocytomas had reduced levels of proteins involved in glutamate and other synaptic signaling proteins that were enriched in higher-grade tumors. Expression of neurotransmitter pathways is an emerging phenomenon in glioma biology with promising therapeutic potential (26–28). Conversely, it could represent intervening infiltrated brain tissue that would be overrepresented in diffuse gliomas. Notably, higher-grade tumors also demonstrated an enrichment of MYC target genes and mRNA processing.

Fig. 2.

Proteomic differences define distinct biological processes within glioma subtypes. (A) Hierarchical clustering based on 486 proteins identified by multiple sample ANOVA (permutation-based FDR<0.1) analysis of bulk frozen glioma tissues (for full protein list, see supplemental Table 5). Four row clusters identify IDHwt GBM and astrocytoma enriched (cluster 1), IDH-wt-specific (cluster 2), IDHmt-enriched (cluster 3), and IDHwt depleted (cluster 4). (B) PCA using abundances of significantly different proteins demonstrates distinguishing proteomes of pilocytic astrocytomas, IDHmt and -wt gliomas. (C) PCA loadings with significantly different proteins from ANOVA driving the spatial separation of tumor subgroups (shown in B) indicated by filled colored circles.

Table I. GO biological process terms enriched in proteomic analysis of frozen glioma cohort in clusters defined in Fig. 2, Enrichment score (Log2) >1, FDR<0.05).

| Cluster ID name | p value | Enrichment | Total | In cluster | Cluster size | Benjamini-Hochberg FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | ||||||

| Negative regulation of endopeptidase activity | 2.74E-06 | 5.4684 | 9 | 8 | 79 | 0.00099 |

| Protein activation cascade | 4.66E-08 | 4.9215 | 15 | 12 | 79 | 4.20E-05 |

| Humoral immune response | 4.66E-08 | 4.9215 | 15 | 12 | 79 | 5.61E-05 |

| Negative regulation of peptidase activity | 1.17E-05 | 4.9215 | 10 | 8 | 79 | 0.00301 |

| Complement activation, classical pathway | 2.59E-07 | 4.8336 | 14 | 11 | 79 | 0.000156 |

| Negative regulation of hydrolase activity | 3.64E-05 | 4.4741 | 11 | 8 | 79 | 0.007304 |

| Immune effector process | 2.68E-08 | 4.1945 | 22 | 15 | 79 | 4.84E-05 |

| Platelet degranulation | 0.000801 | 4.1013 | 9 | 6 | 79 | 0.060233 |

| Receptor-mediated endocytosis | 3.09E-07 | 3.9148 | 22 | 14 | 79 | 0.000159 |

| Membrane invagination | 2.00E-06 | 3.1752 | 31 | 16 | 79 | 0.000803 |

| Endocytosis | 2.00E-06 | 3.1752 | 31 | 16 | 79 | 0.000903 |

| Positive regulation of immune system process | 2.30E-05 | 2.7342 | 36 | 16 | 79 | 0.00554 |

| Cellular membrane organization | 4.08E-06 | 2.4608 | 55 | 22 | 79 | 0.001337 |

| Defense response | 6.97E-05 | 2.2919 | 51 | 19 | 79 | 0.011967 |

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 9.07E-05 | 2.0822 | 65 | 22 | 79 | 0.012115 |

| Positive regulation of response to stimulus | 0.000694 | 2.0133 | 55 | 18 | 79 | 0.056916 |

| Membrane organization | 0.000193 | 1.9903 | 68 | 22 | 79 | 0.018843 |

| Positive regulation of biological process | 2.76E-05 | 1.6661 | 144 | 39 | 79 | 0.005862 |

| Cellular component organization or biogenesis | 0.000184 | 1.4512 | 195 | 46 | 79 | 0.01845 |

| Regulation of biological process | 7.65E-05 | 1.3325 | 277 | 60 | 79 | 0.011502 |

| Biological regulation | 0.000423 | 1.2678 | 296 | 61 | 79 | 0.038155 |

| Cluster 3 | ||||||

| Acetyl-CoA metabolic process | 0.000107 | 2.4888 | 12 | 11 | 179 | 0.04848 |

| DNA metabolic process | 4.87E-05 | 2.0112 | 27 | 20 | 179 | 0.029261 |

| Nucleic acid metabolic process | 5.85E-06 | 1.5838 | 84 | 49 | 179 | 0.007032 |

| Nucleobase-containing compound metabolic process | 2.32E-05 | 1.4581 | 108 | 58 | 179 | 0.016754 |

| Cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process | 3.82E-06 | 1.3832 | 159 | 81 | 179 | 0.006889 |

| Nitrogen compound metabolic process | 6.40E-06 | 1.3659 | 163 | 82 | 179 | 0.005776 |

| Cellular metabolic process | 1.62E-06 | 1.2324 | 282 | 128 | 179 | 0.005851 |

Principal component analysis (PCA) further revealed global proteomic landscape differences of IDHwt gliomas, pilocytic astrocytomas, and IDHmt gliomas (Fig. 2B). The loadings of the PCA revealed proteins responsible for this interesting pattern of spatial separation, including distinct structural (e.g. microtubule-associated protein tau) and signaling (e.g. neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2) proteins enriched in IDHmt glioma and various immune-, metabolism-, and structural-related proteins (i.e. AHNAK, PRPH, and microvascular proliferation) in pilocytic astrocytomas (Fig. 2C). Similarly, this analysis highlighted proteins (i.e. DNAJA2, CELSR2, and nucleoporin 160) with consistently higher levels in IDHwt GBMs. Some of these (e.g. nucleoporin 160), while still not well characterized in gliomas, are predictors of poor outcomes in other tumor types (e.g. renal/liver cancer) (29).

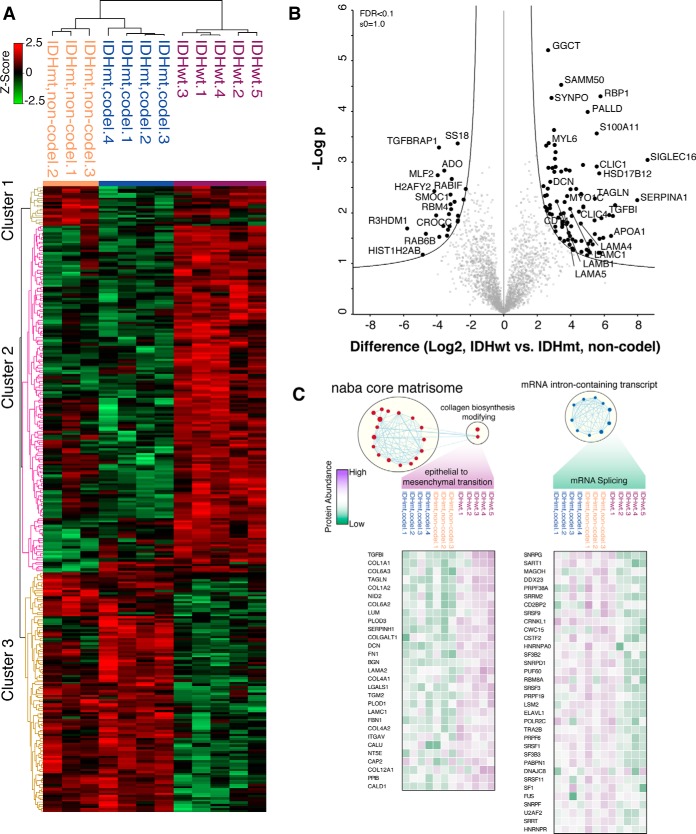

IDHmt Gliomas Bear Distinct Proteomic Signatures Relative to IDHwt GBMs

Although our analysis of frozen bulk tumor biopsies was successful at defining proteomic differences between different tumor grades, differentiation between 1p19q codeleted and non-codeleted diffuse gliomas was less pronounced. We reasoned this could be a result of contaminated normal and noninformative tumor elements (e.g. necrosis). Thus, to define proteomic differences between these more closely related tumors, we performed macrodissection of lesional tumor regions from normal brain and necrotic tumor tissue within FFPE surgical biopsies. By performing multiple sample ANOVA, we identified 287 proteins with significant level differences (permutation-based FDR<0.1) between the three glioma subtypes defined by their IDH and codeletion status (supplemental Table 7, Fig. 3A). This approach resulted in robust clustering of IDHmt, codeleted oligodendrogliomas, and non-codel astrocytomas with a separate cluster of IDHwt GBMs. Three clusters of protein abundance patterns are apparent by hierarchical clustering composed of astrocytoma-specific (cluster 1), IDHwt-specific (cluster 2), and IDHmt-specific (cluster 3) proteins. GO term enrichment analysis revealed that cluster 2 proteins largely belong to the extracellular matrix involved in exocytosis (supplemental Table 8). Distinct proteomic landscapes of macrodissected tumors were further demonstrated by PCA, where IDHmt, non-codel astrocytomas and IDHmt, codel oligodendrogliomas occupied a region distinct from IDHwt GBMs (supplemental Fig. 2). Direct comparison of IDHmt, non-codel to IDHwt astrocytomas revealed 116 significantly different proteins (supplemental Table 9, Fig. 3B). Among the most abundant IDHwt GBM proteins was retinol-binding protein 1, known to be frequently hypermethylated in IDHmt gliomas and negatively correlated with patient survival (30).

Fig. 3.

IDH mutation status-specific protein abundance patterns in macrodissected gliomas. (A) Sectioned FFPE tumor biopsies were macrodissected to deplete samples of necrotic and normal brain components. Hierarchical clustering based on 287 proteins identified by multiple sample ANOVA (permutation-based FDR<0.1) analysis of macrodissected IDHwt GBMs, IDHmt, codel and non-codel tissues (for full protein list, see supplemental Table 7). Three row clusters identify astrocytoma-specific (cluster 1), IDHwt-specific (cluster 2), and IDHmt-specific (cluster 3). (B) Volcano plot directly comparing IDHwt and mt GBMs identifies proteins with the most robust significant changes in abundance. (C) GSEA analysis of protein levels identifies enrichment of processes specific to IHDwt GBMs (epithelial to mesenchymal transition) or IDHmt astrocytomas (increased mRNA splicing). For full GSEA processes, see supplemental Fig. 3.

To more systemically interrogate proteins with abundance level differences between IDHmt and IDHwt tumor samples, we performed GSEA on our datasets (supplemental Fig. 3A). Consistent with the GO term enrichment analysis, proteins more abundant in IDHwt tumors belong to the extracellular matrix (i.e. NABA matrisome, and laminin interactions), BRAF signaling, and EMT processes. On the other hand, proteins enriched in the IDHmt tumors are involved in oxidative-induced senescence, noncoding RNA metabolism, class I HDACs, and cadherin signaling. Proteins belonging to the EMT are traditionally thought to be involved in increasing the stem cell pool of the proliferating tumor, increasing its likelihood of metastasis and radiotherapy resistance (31). Consequently, IDHwt GBMs exhibited high levels of EMT-related proteins such as TGFBI, TAGLN, DCN, and FN1 as well as several collagen chain proteins (i.e. COL1A2, COL6A2 and COL4A2) (Fig. 3C). Members of this group of genes were also detected in previous RNAseq analysis comparing GBMs to normal brain tissue (32). In our analysis, we demonstrated that these EMT genes are detectable at the protein level and are more specifically enriched in IDHwt GBMs. In contrast, IDHmt GBMs contain an enrichment of HDAC-mediated chromatin remodeling and mRNA posttranscriptional regulation in mRNA splicing (supplemental Fig. 3 and Fig. 3C).

To validate the generalizability of our proteomic signatures, we leveraged the large resource of RNA transcriptional profiles of brain tumors in TCGA consortium database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov). We extracted RNAseq values of 421 glioma tumor samples that included IDHwt and IDHmt GBMs, as well as IDHmt astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas. Correlating our MS-based measurements of 2,567 proteins to corresponding RNAseq values demonstrates that our shotgun MS strategy quantitates some of the highest expressing genes (supplemental Fig. 4A). Direct comparisons of RNAseq-to-protein abundance values from our datasets indicates some protein-level changes between molecular subtypes that could have been missed by previous transcriptome-level analysis. Spearman correlations between RNAseq and MS-based quantifications demonstrate that the highest levels of similarity of ∼0.5 are found in corresponding tumor types (supplemental Fig. 4B). This calculation supports the relatively low level of correlation between RNA and protein measurements, previously observed in other systems. Importantly and despite limitation of RNA-protein correlations, when we extracted RNAseq values of 260/287 proteins we defined as significantly different between anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and GBMs, hierarchical clustering correctly separates samples according to their IDH-mutation status (supplemental Fig. 4C). Thus, although our MS-based proteomic signatures of IDHwt GBMs were derived on a limited number of patient tissues, they hold true when extrapolated on an independently derived, sufficiently large, glioma cohort. Interestingly, although there is a low number of IDHmt GBMs (n = 10) in the TCGA cohort, 8/10 co-clustered with other IDHmt tumor samples, reflecting this subtype's distinct molecular landscapes compared with IDHwt neoplasms. Given that our proteomic profiles were generated from macrodissected FFPE tissues, we also utilized an independent RNAseq dataset of laser capture microdissected (LCM) GBM tissues from the Ivy GBM atlas resource (http://glioblastoma.alleninstitute.org/). This publicly available dataset includes carefully demarcated tumor regions from 40 GBMs, including regions of microvascular proliferation, pseudopalisading cells around necrosis, cellular tumor (CT), infiltrating tumor (IT) and the leading edge. Comparison of our MS-based proteomic profiles to the RNAseq measurements of LCM regions demonstrated that proteomic landscape of IDHwt GBMs are most similar to those of microvascular proliferation and pseudopalisading cells around necrosis, while IDHmt GBMs are more representative of infiltrating tumor, cellular tumor, and leading edge (supplemental Fig. 4B). These higher Spearman correlation levels of IDHmt GBMs to intratumoral regions lacking microvasculature and pseudopalisading cells, features of more aggressive GBMs, suggest that our proteomic signatures accurately reflect high-grade-specific cellular features. In fact, when RNAseq values of genes identified by our proteomic profiling are used for hierarchical clustering, there are modest levels of clustering of intratumoral regions, suggesting that our macrodissected proteomic profiles indeed capture subtumor-specific regional profiles (supplemental Fig. 4D).

Proteomes in GSC Lines Maintain IDH-Genotype-Specific Tumor Patterns

Our global proteomic analysis of primary FFPE GBM tissues revealed proteomic signatures that were specific to the IDH-mutation status of tumors. To more accurately define relevant proteins to tumor cells and perhaps even stem-like cells, we analyzed proteomes of established GSCs from the MD Anderson Cancer Center (33, 34). We reasoned that proteins identified in both primary tumor tissue cohorts and confirmed in GSC cultures could serve as tumor-cell-specific candidate proteins that could be prioritized for future functional studies. Toward this, we analyzed three GSC lines (IDHwt GSC1, IDHwt GSC-2, and IDHmt GSC1) in their undifferentiated state, in presence of EGF and FGF, or as differentiating cells in serum without growth factors for eight days (supplemental Fig. 5A). Hierarchical clustering yielded two main nodes of proteome patterns, separating the IDHmt and IDHwt samples irrespective of culture conditions (supplemental Fig. 5B). Multiple sample ANOVA identified 845 significantly different proteins that distinguish cell lines according to their IDH mutation status (supplemental Table 10 and supplemental Fig. 5C). While we detected some proteome-level changes after one week in serum-supplemented media, inter-GSC proteome differences and IDH-status were more dominant features driving clustering (supplemental Fig. 5D).

Importantly, of the 287 protein IDs with significantly different abundance levels in our primary GBM tumor analysis, we found 170 proteins were also detected in GSC cultures. When extrapolated, these 170 proteins accurately segregate the cell lines into hierarchical clusters of IDHwt and IDHmt GSCs (Fig. 4A). We found that IDHmt-GSCs contained relatively low levels of classic precursor markers such as nestin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and vimentin, compared with IDHwt-GSCs. Direct comparisons of primary glioma tumors to GSCs using these overlapping proteins by Spearman rank coefficients demonstrated that IDHwt GBMs more closely resemble IDHwt than IDHmt GSCs (Fig. 4B). Although overall correlation of fold changes in protein levels were modest (Spearman rank IDHwt versus IDHmt GSC/GBM = ∼0.56), a subset of 79 proteins had a remarkably similar level change in both primary tumors and cultured GSCs (Fig. 4C). These proteins encompass some previously discussed biological functions of EMT (e.g. PLOD3, SERPINH1, and COL4A2), interferon and integrin signaling (STAT1 and ITGB1), and the extracellular matrix (LMNB2, LAMA5, and ANXA1). GO term enrichment analysis of these proteins revealed that they are largely located to the endoplasmic reticulum and are involved in response to hormone stimulus and stress (Fig. 4D). To begin validating our identified candidates in a larger external cohort, we carried out orthogonal immunohistochemical staining of PLOD3, an endoplasmic-reticulum-localized protein we found to be enriched in both IDHwt tissues and GSCs, in an independent TMA of 22 additional glioma samples. This analysis revealed a variable expression pattern across the tissues ranging from being restricted to vessels to low, moderate, or high staining patterns within the tumor cells (Fig. 4E). We also used the available immunohistochemically stained cores of the online www.proteinatlas.org resource (containing a TMA of high- (n = 10) and low-grade (n = 2) gliomas) to validate our findings. Although both low-grade gliomas had undetectable PLOD3 in this dataset, 6/10 high-grade gliomas had moderate or high levels of PLOD3. A similar frequency patterns was observed in our own TMA, further validating the robust protein differences we identified in our discovery MS cohorts (Fig. 4F). Although this online resource does not contain comprehensive glioma molecular information, our genomically annotated TMA confirms that vigorous and diffuse staining of PLOD3 protein is a feature of IDHwt tumors (6/12) and found at much lower levels in IDHmt lesions (Fig 4F, supplemental Fig. 6). To further lend support for the biological relevance of our defined candidates in our cohort, we reasoned that proteins candidates such as PLOD3 or the chloride-signaling-related protein CLIC1, found to be elevated in our IDHwt versus IDHmt comparisons, could also correlate with clinical outcomes (survival) on larger clinical cohorts. Indeed, stratifying tumors based on the available RNA expression of CLIC1 and PLOD3 in the online www.proteinatlas.org dataset yielded three-year survivals of 10% and 19% for low-expressing tumors and 0% and 6% in the high expressing tumor samples, respectively (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

Cross referencing IDH mutation-specific GBM proteins in GBM cell lines. (A) Venn diagram indicates that 170 of 287 proteins that were identified through multiple sample statistical tests of FFPE GBMs were also quantitated in GSCs grown as undifferentiated stem-like cells in FGF/EGF or as differentiated cells in presence of FBS for eight days. Expression levels of this set of proteins correctly segregates wild-type GSCs and mGSC (mutant GSCs) independently of their differentiation status in hierarchical clustering (complete Euclidean distance). (B) Spearman rank correlation coefficients of the commonly shared 170 proteins demonstrates that wild-type GBMs are more similar in abundance levels to wild-type GSCs while mutant samples segregate in their own node, without low levels of similarity. (C) Scatterplot of fold changes of proteins in wild-type GSCs and GBMs relative to their mutant counterparts. Forty-seven proteins with positive correlation in both cellular models of GBM are highlighted in blue and EMT-related proteins are in red. (D) Enrichment analysis of positively correlated 47 of the 170 proteins identifies overrepresented GO terms and KEGG processes. (E) Representative cores of PLOD3 immunocytochemistry in a glioma tissue microarray demonstrates diverse protein abundance patterns, either vessel only and/or tumor cells (low, moderate, or high). Insets show high magnification of tissue cores. For the full TMA see supplemental Fig. 6. (F) Ratios of PLOD3 expression patterns in gliomas from www.proteinatlas.org pathology resource (left panel) and our own independently assembled TMA (right panel). In our TMA, gliomas were classified according to IDH and 1p19q co-deletion status. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of glioma patients according to PLOD3 and CLIC1 RNA expression values from 153 gliomas cataloged in the www.proteinatlas.org. P score signifies the log rank p value of the correlation between RNA expression and patient survival.

DISCUSSION

Our molecular understanding of brain tumors has been largely dominated by genomic tools and profiling approaches. Given the role proteins play in biological function, complementary approaches that overlay global, unbiased, translational readouts onto well-characterized genomic events stand to substantially improve our models of gliomas. While accumulating studies are now beginning to unravel the glioma proteome, our study offers distinguishing insights. First, we performed shotgun MS analysis on diverse gliomas spanning the common genetic subtypes, providing important insights into intertumoral differences and thus extending on previous comparisons to normal tissue. Specially, we demonstrate that pilocytic astrocytomas are proteomically distinct from higher-grade infiltrative tumors even when bulk frozen tumors are analyzed. Given that such shotgun LC-MS/MS workflows can be rapidly carried out on FFPE tissue, optimized proteomic assays (e.g. selected reaction monitoring) could provide an alternative molecular tool for rapidly differentiating between these clinically distinct glial neoplasms. While differences of these circumscribed lesions were easily resolved in bulk tissue, our analysis further highlighted the challenges of expression-based assays for more infiltrative tumors (35). Using our FFPE cohort, we show how this can be overcome by macrodissecting away large regions of normal brain and necrotic tissue that can sometimes dominate a biopsy or resection specimen. We use this approach to propose biological pathways operational in distinct glioma subtypes. For instance, more aggressive IDHwt tumors are represented by an overactive EMT and hypoxia, processes known to drive cellular dedifferentiation, tumor invasion, and treatment resistance. Conversely, IDHmt gliomas were enriched in oxidative-induced senescence, cadherin signaling, and mRNA-splicing proteins, known to have deleterious effects on cell proliferation. These pathways are particularly exciting because there is increasing awareness of their role in driving malignancy and, thus, as targets in drug development. For example, there are numerous small molecules (e.g. CX-4945, silmitasertib; LY2157299, galunisertib) and antagomirs/microRNA mimics (e.g. miR-655) being designed to target TGF-β-mediated EMT, some of which are already in preclinical and clinical trials for a variety of malignancies, including gliomas (36–42). Modulation of RNA-splicing defects using small molecules and splicing-switch oligonucleotides are also showing preclinical promise in regulating cancer biology (43). In GBM, Tang et al. showed that the common diuretic amiloride could alter the RNA-splicing forms of the apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 and increase the radiosensitivity of GBM (44). Similarly, using splicing-switch oligonucleotides that block aberrant splicing factor binding to pre-mRNA of Bcl-x, Li et al. could induce apoptosis in GSCs (45). Our findings can further position efforts of these emerging therapies to the appropriate molecular subtypes of gliomas.

By comparing proteins similarly enriched in patient tissue and GSCs derived from the sample molecular background, we further refine promising tumor-specific candidates for future subtype-specific mechanistic and therapeutic studies. For instance, our data show that CLIC1, a chloride intracellular channel protein, and PLOD3, a collagen-crosslinking protein of the endoplasmic reticulum that is involved in EMT, are enriched in IDHwt glioma cells. Building on other studies that demonstrate connect CLIC1 expression to poor survival in gliomas, we now specifically associated its activity within the GSC compartment (46, 47). This is exciting target as the biguanide drug family, which includes metformin and derivatives appears to have good CLIC1 inhibitory activity in GBM (48, 49). Similarly, additional ion dysregulation in glioma progression could also be mediated by the overabundance of the S100A11 protein we found to be enriched in IDHwt GBMs/GSCs and known to be overexpressed in a wide range of other cancers (50). Together, we believe these protein-based analyses may help explain the better outcomes of IDH-mutated gliomas and offer new precision-driven avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Our study is not without its own limitations. To allow us to cover a diverse cohort of glioma subtypes, we chose to accept somewhat modest protein depths and have small subgroups of gliomas. Although the distinct biology of the major glioma subtypes allowed us to capture meaningful protein-level differences within our relatively small cohorts, there are other fruitful opportunities to potentially define clinically relevant protein-level differences within glioma subtypes (e.g. long-term survivorship in IDHwt GBMs (3, 51, 52). In addition to large cohorts, these would likely require deeper proteomic coverage and investigation of posttranslational modifications, which was also outside the scope of this initial study. With those limitations in mind, we note that we detect substantial protein pattern differences between glioma subtypes and define pathway enrichments that are preserved between a variety of different datasets. Our generated dataset thus offers a reliable resource for hypothesis generation and more targeted novel biomarker development.

While diffuse gliomas are now understood to comprise of distinct genomically defined subgroups, the downstream phenotypic changes driven by their unique genetic alternations are largely unexplored. This study provides the first integrated overview of the proteomic landscape of glioma and identifies distinct and targetable pathways differentially operational in subtypes defined by their IDH status. Moreover, we highlight how challenges of expression-based readouts of samples with heterogeneous compositions can be overcome with careful microdissection and comparison to controlled and relatively purified glioma cultures. Assembly of larger, more clinically annotated cohorts and incorporation of advanced proteomic approaches such as deep phospho(proteomic) analysis could greatly expand our phenotypic understanding of this complex disease. Similarly, routine application of the presented FFPE-compatible workflows can help define patient-specific pathways driving individual tumors and better guide personalize glioma care.

Data Availability

The MS proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (22, 23) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD010099 (FFPE gliomas), PXD010133 (frozen gliomas), and PXD010098 (GSCs). Alternatively, MS spectra can be found at MS-viewer (http://msviewer.ucsf.edu/prospector/cgi-bin/msform.cgi?form=msviewer) using search keys: 5b6gqdcbcd (FFPE gliomas), rsw7e8lx39 (frozen gliomas), and 8qp89k3wlb (GSCs).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We also acknowledge all the anonymous brain tumor patients, Marcela White and The Brain Tumor Tissue Bank at the London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario, for providing precious tumor tissue used for this study. We acknowledge the Aldape/Zadeh lab for providing stocks of cell lines used in this study.

Footnotes

*U.D. is supported by the Richard Motyka Brain Tumor Research fellowship of the Brain Tumor Foundation of Canada. J.K. is supported by CIHR CGSM studentship. Research time and space for P.D. is provided by the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and University Health Network Department of Pathology. M.P. is supported through an Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Ontario Molecular Pathology Research Network (OICR-OMPRN) Research Grant. Experimental costs were provided by the Cancer Research Society and Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR, Institute of Cancer Research) through the CRS Operating Grant Funding Program. Additional funding was provided by the Canadian Cancer Society. The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

This article contains supplemental material Tables 1–11 and Figs. 1–6.

This article contains supplemental material Tables 1–11 and Figs. 1–6.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- WHO

- World Health Organization

- BRAF

- B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- CIC

- capicua transcriptional repressor

- FUBP1

- far upstream element binding protein 1

- NOTCH1

- notch receptor 1

- TERT

- telomerase reverse transcriptase

- ATRX

- alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homolog

- CDKN2A

- cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A

- FFPE

- formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded

- UHN

- university health network

- PSM

- peptide/spectrum match

- ID

- identification

- DAVID

- DAVID Functional Annotation Bioinformatics Microarray Analysis

- AHNAK

- AHNAK Nucleoprotein

- PRPH

- peripherin

- DNAJA2

- DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member A2

- CELSR2

- Cadherin EGF LAG Seven-Pass G-Type Receptor 2

- HDACs

- histone deacetylases

- TGFBI

- transforming growth factor beta induced

- TAGLN

- transgelin

- DCN

- decorin

- FN1

- fibronectin 1

- COL

- collagen

- LCM

- laser capture microdissected

- CT

- cellular tumor

- IT

- infiltrating tumor

- SERPINH1

- Serpin Family H Member 1

- STAT1

- Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription 1

- CLIC1

- chloride intracellular channel 1

- ITGB1

- Integrin Subunit Beta 1

- LMNB2

- Lamin B2

- LAMA5

- Laminin Subunit Alpha 5

- ANXA1

- Annexin A1

- mGSC

- mutant GSCs.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parsons D. W., Jones S., Zhang X., Lin J. C., Leary R. J., Angenendt P., Mankoo P., Carter H., Siu I. M., Gallia G. L., Olivi A., McLendon R., Rasheed B. A., Keir S., Nikolskaya T., Nikolsky Y., Busam D. A., Tekleab H., Diaz L. A., Hartigan J., Smith D. R., Strausberg R. L., Marie S. K., Shinjo S. M., Yan H., Riggins G. J., Bigner D. D., Karchin R., Papadopoulos N., Parmigiani G., Vogelstein B., Velculescu V. E., and Kinzler K. W. (2008) An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 321, 1807–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brat D. J., Verhaak R. G., Aldape K. D., Yung W. K., Salama S. R., Cooper L. A., Rheinbay E., Miller C. R., Vitucci M., Morozova O., Robertson A. G., Noushmehr H., Laird P. W., Cherniack A. D., Akbani R., Huse J. T., Ciriello G., Poisson L. M., Barnholtz-Sloan J. S., Berger M. S., Brennan C., Colen R. R., Colman H., Flanders A. E., Giannini C., Grifford M., Iavarone A., Jain R., Joseph I., Kim J., Kasaian K., Mikkelsen T., Murray B. A., O'Neill B. P., Pachter L., Parsons D. W., Sougnez C., Sulman E. P., Vandenberg S. R., Van Meir E. G., von Deimling A., Zhang H., Crain D., Lau K., Mallery D., Morris S., Paulauskis J., Penny R., Shelton T., Sherman M., Yena P., Black A., Bowen J., Dicostanzo K., Gastier-Foster J., Leraas K. M., Lichtenberg T. M., Pierson C. R., Ramirez N. C., Taylor C., Weaver S., Wise L., Zmuda E., Davidsen T., Demchok J. A., Eley G., Ferguson M. L., Hutter C. M., Mills Shaw K. R., Ozenberger B. A., Sheth M., Sofia H. J., Tarnuzzer R., Wang Z., Yang L., Zenklusen J. C., Ayala B., Baboud J., Chudamani S., Jensen M. A., Liu J., Pihl T., Raman R., Wan Y., Wu Y., Ally A., Auman J. T., Balasundaram M., Balu S., Baylin S. B., Beroukhim R., Bootwalla M. S., Bowlby R., Bristow C. A., Brooks D., Butterfield Y., Carlsen R., Carter S., Chin L., Chu A., Chuah E., Cibulskis K., Clarke A., Coetzee S. G., Dhalla N., Fennell T., Fisher S., Gabriel S., Getz G., Gibbs R., Guin R., Hadjipanayis A., Hayes D. N., Hinoue T., Hoadley K., Holt R. A., Hoyle A. P., Jefferys S. R., Jones S., Jones C. D., Kucherlapati R., Lai P. H., Lander E., Lee S., Lichtenstein L., Ma Y., Maglinte D. T., Mahadeshwar H. S., Marra M. A., Mayo M., Meng S., Meyerson M. L., Mieczkowski P. A., Moore R. A., Mose L. E., Mungall A. J., Pantazi A., Parfenov M., Park P. J., Parker J. S., Perou C. M., Protopopov A., Ren X., Roach J., Sabedot T. S., Schein J., Schumacher S. E., Seidman J. G., Seth S., Shen H., Simons J. V., Sipahimalani P., Soloway M. G., Song X., Sun H., Tabak B., Tam A., Tan D., Tang J., Thiessen N., Triche T., Van Den Berg D. J., Veluvolu U., Waring S., Weisenberger D. J., Wilkerson M. D., Wong T., Wu J., Xi L., Xu A. W., Yang L., Zack T. I., Zhang J., Aksoy B. A., Arachchi H., Benz C., Bernard B., Carlin D., Cho J., DiCara D., Frazer S., Fuller G. N., Gao J., Gehlenborg N., Haussler D., Heiman D. I., Iype L., Jacobsen A., Ju Z., Katzman S., Kim H., Knijnenburg T., Kreisberg R. B., Lawrence M. S., Lee W., Leinonen K., Lin P., Ling S., Liu W., Liu Y., Liu Y., Lu Y., Mills G., Ng S., Noble M. S., Paull E., Rao A., Reynolds S., Saksena G., Sanborn Z., Sander C., Schultz N., Senbabaoglu Y., Shen R., Shmulevich I., Sinha R., Stuart J., Sumer S. O., Sun Y., Tasman N., Taylor B. S., Voet D., Weinhold N., Weinstein J. N., Yang D., Yoshihara K., Zheng S., Zhang W., Zou L., Abel T., Sadeghi S., Cohen M. L., Eschbacher J., Hattab E. M., Raghunathan A., Schniederjan M. J., Aziz D., Barnett G., Barrett W., Bigner D. D., Boice L., Brewer C., Calatozzolo C., Campos B., Carlotti C. G., Chan T. A., Cuppini L., Curley E., Cuzzubbo S., Devine K., DiMeco F., Duell R., Elder J. B., Fehrenbach A., Finocchiaro G., Friedman W., Fulop J., Gardner J., Hermes B., Herold-Mende C., Jungk C., Kendler A., Lehman N. L., Lipp E., Liu O., Mandt R., McGraw M., Mclendon R., McPherson C., Neder L., Nguyen P., Noss A., Nunziata R., Ostrom Q. T., Palmer C., Perin A., Pollo B., Potapov A., Potapova O., Rathmell W. K., Rotin D., Scarpace L., Schilero C., Senecal K., Shimmel K., Shurkhay V., Sifri S., Singh R., Sloan A. E., Smolenski K., Staugaitis S. M., Steele R., Thorne L., Tirapelli D. P., Unterberg A., Vallurupalli M., Wang Y., Warnick R., Williams F., Wolinsky Y., Bell S., Rosenberg M., Stewart C., Huang F., Grimsby J. L., Radenbaugh A. J., and Zhang J. (2015) Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2481–2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hartmann C., Hentschel B., Simon M., Westphal M., Schackert G., Tonn J. C., Loeffler M., Reifenberger G., Pietsch T., von Deimling A., Weller M., and German Glioma Network. (2013) Long-term survival in primary glioblastoma with versus without isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 5146–5157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ostrom Q. T., Gittleman H., Farah P., Ondracek A., Chen Y., Wolinsky Y., Stroup N. E., Kruchko C., and Barnholtz-Sloan J. S. (2013) CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006–2010. Neuro. Oncol. 15, ii1–ii56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van den Bent M. J. (2010) Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: A clinician's perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 120, 297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coons S. W., Johnson P. C., Scheithauer B. W., Yates A. J., and Pearl D. K. (1997) Improving diagnostic accuracy and interobserver concordance in the classification and grading of primary gliomas. Cancer 79, 1381–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sahm F., Reuss D., Koelsche C., Capper D., Schittenhelm J., Heim S., Jones D. T., Pfister S. M., Herold-Mende C., Wick W., Mueller W., Hartmann C., Paulus W., and von Deimling A. (2014) Farewell to oligoastrocytoma: In situ molecular genetics favor classification as either oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 551–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Louis D. N., Perry A., Reifenberger G., von Deimling A., Figarella-Branger D., Cavenee W. K., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O. D., Kleihues P., and Ellison D. W. (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 803–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith J. S., Perry A., Borell T. J., Lee H. K., O'Fallon J., Hosek S. M., Kimmel D., Yates A., Burger P. C., Scheithauer B. W., and Jenkins R. B. (2000) Alterations of chromosome arms 1p and 19q as predictors of survival in oligodendrogliomas, astrocytomas, and mixed oligoastrocytomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 636–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cairncross J. G., Ueki K., Zlatescu M. C., Lisle D. K., Finkelstein D. M., Hammond R. R., Silver J. S., Stark P. C., Macdonald D. R., Ino Y., Ramsay D. A., and Louis D. N. (1998) Specific genetic predictors of chemotherapeutic response and survival in patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 1473–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yan H., Parsons D. W., Jin G., McLendon R., Rasheed B. A., Yuan W., Kos I., Batinic-Haberle I., Jones S., Riggins G. J., Friedman H., Friedman A., Reardon D., Herndon J., Kinzler K. W., Velculescu V. E., Vogelstein B., and Bigner D. D. (2009) IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 765–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chinot O. L., Wick W., Mason W., Henriksson R., Saran F., Nishikawa R., Carpentier A. F., Hoang-Xuan K., Kavan P., Cernea D., Brandes A. A., Hilton M., Abrey L., and Cloughesy T. (2014) Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 709–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hegi M. E., Diserens A. C., Gorlia T., Hamou M. F., de Tribolet N., Weller M., Kros J. M., Hainfellner J. A., Mason W., Mariani L., Bromberg J. E., Hau P., Mirimanoff R. O., Cairncross J. G., Janzer R. C., and Stupp R. (2005) MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang B., Wang J., Wang X., Zhu J., Liu Q., Shi Z., Chambers M. C., Zimmerman L. J., Shaddox K. F., Kim S., Davies S. R., Wang S., Wang P., Kinsinger C. R., Rivers R. C., Rodriguez H., Townsend R. R., Ellis M. J., Carr S. A., Tabb D. L., Coffey R. J., Slebos R. J., and Liebler D. C. (2015) Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 513, 382–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mertins P., Mani D. R., Ruggles K. V., Gillette M. A., Clauser K. R., Wang P., Wang X., Qiao J. W., Cao S., Petralia F., Kawaler E., Mundt F., Krug K., Tu Z., Lei J. T., Gatza M. L., Wilkerson M., Perou C. M., Yellapantula V., Huang K. L., Lin C., McLellan M. D., Yan P., Davies S. R., Townsend R. R., Skates S. J., Wang J., Zhang B., Kinsinger C. R., Mesri M., Rodriguez H., Ding L., Paulovich A. G., Fenyö D., Ellis M. J., and Carr S. A. (2016) Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature 534, 55–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang H., Liu T., Zhang Z., Payne S. H., Zhang B., McDermott J. E., Zhou J. Y., Petyuk V. A., Chen L., Ray D., Sun S., Yang F., Chen L., Wang J., Shah P., Cha S. W., Aiyetan P., Woo S., Tian Y., Gritsenko M. A., Clauss T. R., Choi C., Monroe M. E., Thomas S., Nie S., Wu C., Moore R. J., Yu K. H., Tabb D. L., Fenyö D., Vineet V., Wang Y., Rodriguez H., Boja E. S., Hiltke T., Rivers R. C., Sokoll L., Zhu H., Shih I. M., Cope L., Pandey A., Zhang B., Snyder M. P., Levine D. A., Smith R. D., Chan D. W., Rodland K. D. and CPAC Investigators. (2016) Integrated proteogenomic characterization of human high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cell 166, 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stetson L. C., Dazard J. E., and Barnholtz-Sloan J. S. (2016) Protein markers predict survival in glioma patients. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 15, 2356–2365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heroux M. S., Chesnik M. a. Halligan B. D., Al-Gizawiy M., Connelly J. M., Mueller W. M., Rand S. D., Cochran E. J., LaViolette P. S., Malkin M. G., Schmainda K. M., and Mirza S. P. (2014) Comprehensive characterization of glioblastoma tumor tissues for biomarker identification using mass spectrometry-based label-free quantitative proteomics. Physiol. Genomics 46, 467–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Djuric U., Rodrigues D. C., Batruch I., Ellis J., Shannon P., and Diamandis P. (2017) Spatiotemporal proteomic profiling of human cerebral development. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16, 1548–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Papaioannou M.-D., Djuric U., Kao J., Karimi S., Zadeh G., Aldape K., and Diamandis P. (2019) Proteomic analysis of meningiomas reveals clinically-distinct molecular patterns. Neuro. Oncol. pii, noz084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee J., Kotliarova S., Kotliarov Y., Li A., Su Q., Donin N. M., Pastorino S., Purow B. W., Christopher N., Zhang W., Park J. K., and Fine H. A. (2006) Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell 9, 391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vizcaíno J. A., Csordas A., del-Toro N., Dianes J. A., Griss J., Lavidas I., Mayer G., Perez-Riverol Y., Reisinger F., Ternent T., Xu Q. W., Wang R., and Hermjakob H. (2016) 2016 update of the PRIDE database and its related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D447–D456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deutsch E. W., Csordas A., Sun Z., Jarnuczak A., Perez-Riverol Y., Ternent T., Campbell D. S., Bernal-Llinares M., Okuda S., Kawano S., Moritz R. L., Carver J. J., Wang M., Ishihama Y., Bandeira N., Hermjakob H., and Vizcaíno J. A. (2017) The ProteomeXchange consortium in 2017: Supporting the cultural change in proteomics public data deposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1100–D1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doll S., Urisman A., Oses-Prieto J. A., Arnott D., and Burlingame A. L. (2017) Quantitative proteomics reveals fundamental regulatory differences in oncogenic HRAS and isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1) driven astrocytoma. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 16, 39–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le Rhun E., Duhamel M., Wisztorski M., Gimeno J. P., Zairi F., Escande F., Reyns N., Kobeissy F., Maurage C. A., Salzet M., and Fournier I. (2017) Evaluation of non-supervised MALDI mass spectrometry imaging combined with microproteomics for glioma grade III classification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics 1865, 875–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diamandis P., Sacher A. G., Tyers M., and Dirks P. B. (2009) New drugs for brain tumors? Insights from chemical probing of neural stem cells. Med. Hypotheses 72, 683–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diamandis P., Wildenhain J., Clarke I. D., Sacher A. G., Graham J., Bellows D. S., Ling E. K., Ward R. J., Jamieson L. G., Tyers M., and Dirks P. B. (2007) Chemical genetics reveals a complex functional ground state of neural stem cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 268–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dolma S., Selvadurai H. J., Lan X., Lee L., Kushida M., Voisin V., Whetstone H., So M., Aviv T., Park N., Zhu X., Xu C., Head R., Rowland K. J., Bernstein M., Clarke I. D., Bader G., Harrington L., Brumell J. H., Tyers M., and Dirks P. B. (2016) Inhibition of dopamine receptor D4 impedes autophagic flux, proliferation, and survival of glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Cell 29, 859–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uhlen M., Zhang C., Lee S., Sjöstedt E., Fagerberg L., Bidkhori G., Benfeitas R., Arif M., Liu Z., Edfors F., Sanli K., von Feilitzen K., Oksvold P., Lundberg E., Hober S., Nilsson P., Mattsson J., Schwenk J. M., Brunnström H., Glimelius B., Sjöblom T., Edqvist P. H., Djureinovic D., Micke P., Lindskog C., Mardinoglu A., and Ponten F. (2017) A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science 357, eaan2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chou A. P., Chowdhury R., Li S., Chen W., Kim A. J., Piccioni D. E., Selfridge J. M., Mody R. R., Chang S., Lalezari S., Lin J., Sanchez D. E., Wilson R. W., Garrett M. C., Harry B., Mottahedeh J., Nghiemphu P. L., Kornblum H. I., Mischel P. S., Prins R. M., Yong W. H., Cloughesy T., Nelson S. F., Liau L. M., and Lai A. (2012) Identification of tetinol binding protein 1 promoter hypermethylation in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutant gliomas. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 104, 1458–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Iwadate Y. (2016) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma progression. Oncol. Lett. 11, 1615–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Long H., Liang C., Zhang X., Fang L., Wang G., Qi S., Huo H., and Song Y. (2017) Prediction and analysis of key genes in glioblastoma based on bioinformatics. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 7653101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Danussi C., Bose P., Parthasarathy P. T., Silberman P. C., Van Arnam J. S., Vitucci M., Tang O. Y., Heguy A., Wang Y., Chan T. A., Riggins G. J., Sulman E. P., Lang F., Creighton C. J., Deneen B., Miller C. R., Picketts D. J., Kannan K., and Huse J. T. (2018) Atrx inactivation drives disease-defining phenotypes in glioma cells of origin through global epigenomic remodeling. Nat. Commun. 9, 1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bhat K. P. L., Balasubramaniyan V., Vaillant B., Ezhilarasan R., Hummelink K., Hollingsworth F., Wani K., Heathcock L., James J. D., Goodman L. D., Conroy S., Long L., Lelic N., Wang S., Gumin J., Raj D., Kodama Y., Raghunathan A., Olar A., Joshi K., Pelloski C. E., Heimberger A., Kim S. H., Cahill D. P., Rao G., DenDunnen W. F. A., Boddeke H. W. G. M., Phillips H. S., Nakano I., Lang F. F., Colman H., Sulman E. P., and Aldape K. (2013) Mesenchymal differentiation mediated by NF-κB promotes radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 24, 331–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee J. K., Wang J., Sa J. K., Ladewig E., Lee H. O., Lee I. H., Kang H. J., Rosenbloom D. S., Camara P. G., Liu Z., Van Nieuwenhuizen P., Jung S. W., Choi S. W., Kim J., Chen A., Kim K. T., Shin S., Seo Y. J., Oh J. M., Shin Y. J., Park C. K., Kong D. S., Seol H. J., Blumberg A., Lee J., Il, Iavarone A., Park W. Y., Rabadan R., and Nam D. H. (2017) Spatiotemporal genomic architecture informs precision oncology in glioblastoma. Nat. Genet. 49, 594–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thiery J. P. (2002) Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 442–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yingling J. M., Blanchard K. L., and Sawyer J. S. (2004) Development of TGF-β signalling inhibitors for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 1011–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zou J., Luo H., Zeng Q., Dong Z., Wu D., and Liu L. (2011) Protein kinase CK2α is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and modulates cell proliferation and invasion via regulating EMT-related genes. J. Transl. Med. 9, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kothari A. N., Mi Z., Zapf M., and Kuo P. C. (2014) Novel clinical therapeutics targeting the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Clin. Transl. Med. 3, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harazono Y., Muramatsu T., Endo H., Uzawa N., Kawano T., Harada K., Inazawa J., and Kozaki K. (2013) miR-655 Is an EMT-suppressive microRNA targeting ZEB1 and TGFBR2. PLoS ONE 8, e62757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rupaimoole R., and Slack F. J. (2017) MicroRNA therapeutics: Towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 203–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Reka A. K., Kuick R., Kurapati H., Standiford T. J., Omenn G. S., and Keshamouni V. G. (2011) Identifying inhibitors of epithelial-mesenchymal transition by connectivity map-based systems approach. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 1784–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Di C., Syafrizayanti Zhang Q., Chen Y., Wang Y., Zhang X., Liu Y., Sun C., Zhang H., and Hoheisel J. D. (2019) Function, clinical application, and strategies of Pre-mRNA splicing in cancer. Cell Death Differ. 26, 1181–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tang J. Y., Chang H. W., and Chang J. G. (2013) Modulating roles of amiloride in irradiation-induced antiproliferative effects in glioblastoma multiforme cells involving Akt phosphorylation and the alternative splicing of apoptotic genes. DNA Cell Biol. 32, 504–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li Z., Li Q., Han L., Tian N., Liang Q., Li Y., Zhao X., Du C., and Tian Y. (2016) Pro-apoptotic effects of splice-switching oligonucleotides targeting Bcl-x pre-mRNA in human glioma cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 35, 1013–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang L., He S., Tu Y., Ji P., Zong J., Zhang J., Feng F., Zhao J., Zhang Y., and Gao G. (2012) Elevated expression of chloride intracellular channel 1 is correlated with poor prognosis in human gliomas. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 31, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Setti M., Savalli N., Osti D., Richichi C., Angelini M., Brescia P., Fornasari L., Carro M. S., Mazzanti M., and Pelicci G. (2013) Functional role of CLIC1 ion channel in glioblastoma-derived stem/progenitor cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 105, 1644–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barbieri F., Würth R., Pattarozzi A., Verduci I., Mazzola C., Cattaneo M. G., Tonelli M., Solari A., Bajetto A., Daga A., Vicentini L. M., Mazzanti M., and Florio T. (2018) Inhibition of chloride intracellular channel 1 (CLIC1) as biguanide class-effect to impair human glioblastoma stem cell viability. Front. Pharmacol. 9, 899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gritti M., Würth R., Angelini M., Barbieri F., Peretti M., Pizzi E., Pattarozzi A., Carra E., Sirito R., Daga A., Curmi P. M., Mazzanti M., and Florio T. (2014) Metformin repositioning as antitumoral agent: Selective antiproliferative effects in human glioblastoma stem cells, via inhibition of CLIC1-mediated ion current. Oncotarget 5, 11252–11268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cross S. S., Hamdy F. C., Deloulme J. C., and Rehman I. (2005) Expression of S100 proteins in normal human tissues and common cancers using tissue microarrays: S100A6, S100A8, S100A9 and S100A11 are all overexpressed in common cancers. Histopathology 46, 256–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]