Abstract

Introduction and study aims Accurate real-time endoscopic characterization of colorectal polyps is key to choosing the most appropriate treatment. Mastering the currently available classifications is challenging. We used validated criteria for these classifications to create a single table, named CONECCT, and evaluated the impact of a teaching program based on this tool.

Methods A prospective multicenter study involving GI fellows and attending physicians was conducted. During the first session, each trainee completed a pretest consisting in histological prediction and choice of treatment of 20 colorectal polyps still frames. This was followed by a 30-minute course on the CONECCT table, before taking a post-test using the same still frames reshuffled. During a second session at 3 – 6 months, a last test (T3 M) was performed, including these same still frames and 20 new ones.

Results A total 419 participants followed the teaching program between April 2017 and April 2018. The mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions improved significantly from pretest to post-test and to T3 M, from 51.0 % to 74.0 % and to 66.6 % respectively ( P < 0.001). Between pretest and post-test, 343 (86.6 %) trainees improved, and 153 (75.4 %) at T3 M. Significant improvement occurred for each subtype of polyp for fellows and attending physicians. Between the two sessions, trainees continued to progress in the histology prediction and treatment choice of polyps CONECCT IIA. Over-treatment decreased significantly from 30.1 % to 15.5 % at post-test and to 18.5 % at T3 M ( P < 0.001).

Conclusion The CONECCT teaching program is effective to improve the histology prediction and the treatment choice by gastroenterologists, for each subtype of colorectal polyp.

Introduction

Five subtypes of colorectal polyps have been described: hyperplastic polyps (HP), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), adenomas with a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma, adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinoma (intramucosal or submucosal invasion under 1000 microns (sm1), and invasive adenocarcinomas (submucosal involvement over 1000 microns).

In theory, therapeutic approach differs according to type of polyp. Whereas HP do not require resection when their diameter is less than 10 mm 1 2 , SSL and adenomas with a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma must be completely resected to avoid recurrence, and for these en bloc resection with free margins is preferable but not mandatory. In adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinomas, endoscopic en bloc resection with negative margins (R0 resection) is preferred to piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resections (EPMR), as it allows proper pathological assessment and avoids local recurrence, despite this being associated with higher risk of complication 3 . For invasive adenocarcinomas, surgery with lymphadenectomy and/or chemotherapy but not endoscopic treatment is recommended.

Accurate real-time characterization of colorectal polyps during colonoscopy is of paramount importance as it will allow the most appropriate treatment to be chosen. At least seven classifications are currently used to characterize colorectal polyps. The macroscopic pattern is described by the Paris Classification 4 and by the laterally spreading tumors (LST) classification 5 . The pit pattern is described by Kudo’s classification 6 (requiring use of indigo carmine with or without crystal violet dying), the NICE classification (NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic) 7 , and the JNET classification (Japan NBI Expert Team) 8 . The vascular pattern is described by Sano’s 9 , JNET 8 , and NICE 7 classifications. SSL are characterized by the WASP (Workgroup serrAted polypS and Polyposis) criteria 10 . All these classifications have limitations, and none is sufficiently comprehensive to describe and characterize alone all five subtypes of colorectal lesions. For instance, the NICE classification 7 is effective in differentiating HP (type 1) from invasive carcinoma (type 3) from adenomas and superficial carcinoma (type 2). This classification does not differentiate between adenomas with a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and those with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinomas, although their treatment responds to different constrains. The JNET Classification 8 differentiates low-risk adenomas from superficial invasive carcinoma with a good accuracy (77.1 % for type 2A and 78.1 % for type 2B). However, it does not take into account the macroscopic type of laterally spreading tumors, in which invasive adenocarcinoma may exist despite the lack of an irregular pattern, as demonstrated by Yamada et al. (21.1 % for LST NG, 15.0 % for LST G with large nodule or depression) 11 The SSLs are only described in WASP classification with a good accuracy 10 .

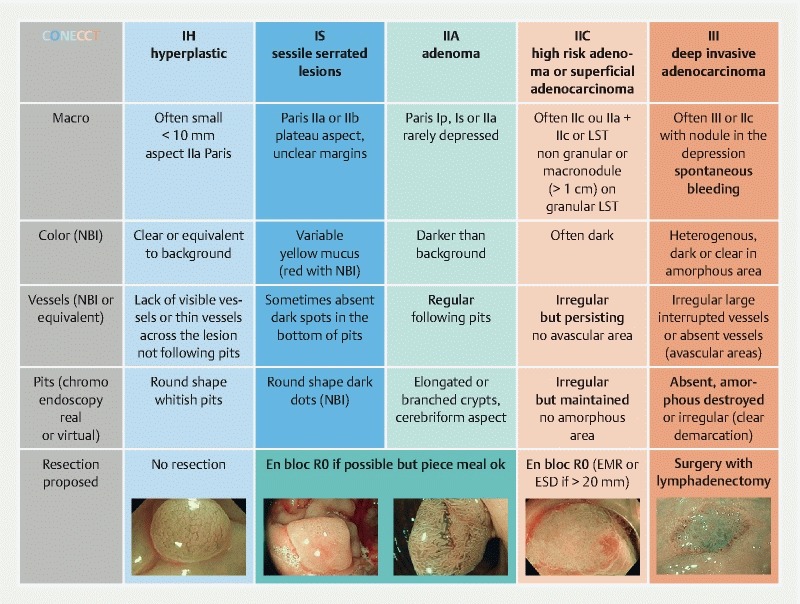

We therefore merged criteria for these seven validated classifications into a single table named COlorectal NEoplasia Endoscopic Classification to Choose the Treatment (CONECCT; Fig. 1 ) with a pragmatic proposal of the most appropriate treatment based on each subtype of colorectal polyp and on the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines (ESGE) 3 12 , The current study aimed to assess the impact of a teaching program, using this newly created table, in terms of accuracy of polyp characterization, and choice of appropriate treatment.

Fig. 1.

CONECCT table. The words in bold are the ones that require particular attention when analyzing lesions.

Methods

Design

We conducted a prospective multicenter study including trainees (gastroenterology fellows and attending physicians) who were evaluated before, and immediately and at 3 to 6 months after a teaching course on characterization and treatment of colorectal lesions using the CONECCT table.

CONECCT table

The CONECCT table was created using a combination of criteria used in the aforementioned classifications (Paris4, LST5, NICE7, Kudo6, WASP10, JNET8, Sano9), by physicians from the research and development committee of the Société Francaise d’Endoscopie Digestive (SFED; Fig. 1 ). Characterization of the lesions was based on the macroscopic aspect, the color on narrow band imaging (NBI), vascular pattern and pit pattern. To characterize a polyp using the CONECCT table, at least two imaging conditions are required. On the one hand, a white-light distant image of the polyp is required to analyze its macroscopic aspect. On the other hand, a virtual chromoendoscopy-ready image with magnification, if possible, is needed to analyze the microscopic structures of the polyps and identify diagnostic criteria associated with a risk of neoplasia. For each subtype of colorectal polyp, this table suggested a treatment, based on the latest guidelines from the ESGE 3 12 .

HP (CONECCT IH) are mostly seen in the rectum and the sigmoid. These lesions have the following features based on the NICE classification 7 : color is same or lighter than background, vessels are lacking or isolated lacy vessels coursing across the lesion that do not surround the pits and the surface pattern has dark or white spots of uniform size or homogeneous absence of pattern. IH are usually small and numerous. Risk of progression to cancer is null and guidelines do not recommend resection of these polyps after proper identification using virtual chromoendoscopy (NBI) if they are less than 5 mm 12 .

SSLs (CONECCT IS) are characterized using the WASP classification, 10 two of the following criteria are required: indistinctive border, clouded surface, irregular shape and dark spots inside the crypts. SSL are frequently covered by a yellowish mucus cap, and although not used in the WASP classification 10 as a diagnostic criterion, this was added to the table to aid recognition. For SSL, resection is recommended given the risk of cancer (via BRAF mutation). However, most of these lesions are not dysplastic and reports of transformed SSL are rare. Thus, low-risk endoscopic resection methods without aiming for completely free margins are recommended (preferably En Bloc) to reduce the risk of perforation 12 .

Adenomas CONECCT IIA have a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma (< 1 %). They present a various array of features. According to the Paris classification, the macroscopic shape can be sessile (Is), pedunculated (Ip), or flat (IIa or IIb) 4 . The vascular pattern is that of meshed regular vessels surrounding the pits (Sano II) 9 . The pit pattern based on Kudo’s classification can be of type IIIs, IIIL, or IV 6 . These lesions lack any of the criteria seen in adenomas with a high risk of undetected carcinoma (CONECCT IIC), superficial (CONECCT IIC) and invasive carcinomas (CONECCT III). As for SSL, these lesions should also be resected with low-risk endoscopic procedures. Of note, granular homogenous laterally spreading tumor (LST G) with no macro nodule are considered at very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma when smaller than 4 cm and can be resected with EPMR as recommended by the ESGE guidelines 12 .

Adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinomas (CONECCT IIC) constitute the fourth subtype of colorectal polyp. Adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma are lesions without clear evidence of adenocarcinoma, but with a high risk of invasive carcinoma because of their macroscopic aspect. Non-granular LST (LST NG) and LST G with large nodules (> 1 cm) for instance have a high risk of invasive carcinoma, over 15 % 5 . Given this risk, en bloc resection is recommended, as this allows correct pathological examination that, in turn, avoids underestimation of the depth of invasion. Superficial adenocarcinomas are lesions with evidence of neoplasia but no clear features of deep submucosal invasion. For instance, a slightly depressed lesion (Paris classification IIc) 4 , the lake of uniformity of the vessels and the high density of capillary vessels without avascular areas (Sano’s IIIa) 9 or presence of an irregular pit pattern (irregular mucosal pattern without any amorphous area and without demarcation line; Kudo’s type V) 6 are associated with a high risk of invasive components and should be resected en bloc with free margins, to allow pathological examination and curative resection 12 . (Irregular mucosal and vascular pattern also define type 2B of the JNET classification 8 .)

Invasive adenocarcinomas (CONECCT III) typically presents with features associated with a high risk of deep submucosal invasion such as an excavated shape (III Paris classification 4 ), nodule or pseudo mass within a depressed LST NG, avascular areas (Sano’s IIIB) 9 loss or decrease of pits with an amorphous structure (Kudo Vn) or an irregular pit pattern in a demarcated area (Vi invasive) 6 . These avascular and amorphous features are also used in the NICE (type 3) and JNET classifications (type 3) 8 . In such cases, endoscopic procedures are not indicated. Patients must be referred to an oncologist.

Trainees and teaching program

Fellows from the seven French districts (Paris region, Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, Southeast, West, and East) were invited to participate in the study as ‘trainees’ after signed consent. In France, gastroenterology fellows are postgraduate (post-medical school) students specializing in hepatology, gastroenterology, and endoscopy. Attending physicians were also invited to participate by the French society of digestive endoscopy ( Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive – SFED), via email, newsletter, website publications, and during nationwide meetings.

Teaching program was divided into two training sessions occurring at least 3 months apart (this design was chosen for feasibility reasons as well since gastroenterology fellows in France are available all together only twice a year). Each trainee created an identification number (ID) from his/her initials and date of birth. For each training session, the trainee was requested to indicate his/her ID on the reply form to match their identity with the test answers. Trainees were excluded from the first training session if they did not complete each of the two required tests (pretest and post-test) in the first training session, and from the second training session analysis at 3 to 6 months (T3 M) if their ID could not be matched with that used in the first training session.

For each training session, the different tests (pretest, post-test, and T3 M) were taken either in person on paper or online (Google Forms, Google Inc., California, United States). Images of the lesions were projected by a video projector if the training session was done in a classroom, otherwise they appeared on their computer screen if the participant answered online. Participants had as much time as they wanted to analyze the images.

First training session

The first training session was divided into five steps:

Step 1: Evaluation of awareness and clinical use of the seven classifications used in the CONECCT table (Paris 4 , LST 5 , NICE 7 , Kudo 6 , WASP 10 , JNET 8 , Sano 9 ).

Step 2 (pre-test): Histological prediction and treatment choice for 20 colorectal polyps. To predict histology, trainees were provided with one to five images per lesion, at least one of which was taken with NBI, the rest being taken in WL; lesions were not dyed. The location in the colon of the polyps were provided.

Step 3: Standardized 30-minute teaching course given by French endoscopy experts (endoscopists currently performing advanced endoscopic diagnosis and ESD) from the research and development committee of the SFED and describing the content of the CONECCT table, including the criteria for each of the five subtypes of colorectal polyps with several examples, as well as the recommended treatments.

Step 4 (post-test): Identical to pretest, but frames in a different order. Of note, regarding histological prediction, trainees had to reply using the CONECCT table that was provided to them. For both tests, the breakdown of lesions was as follows: three HP, four SSLs, five adenomas, four high-risk adenoma or superficial adenocarcinomas and four deep invasive adenocarcinomas.

Step 5: At the end of the first training session, the group of trainees were informed of the correct histological prediction and the treatment choice for each example but did not receive individual feedback as to potential errors.

Second training session (T3 M)

Three to 6 months after the first training session, the trainees took the T3 M test that consisted of still frames depicting a total of 40 colorectal polyps, including the 20 polyps used during the first training session and 20 new polyps. The questions were identical to those in the first training session and there was no additional teaching course. The breakdown of lesions was as follows: seven HP, eight SSLs, nine adenomas, eight high-risk adenomas or superficial adenocarcinomas and eight deep invasive adenocarcinomas.

Evaluation of the trainees’ answers

For each individual frame, the answer was considered correct if the trainee chose the correct histological prediction or treatment choice. Regarding histological prediction, trainees chose among the following possibilities: HP, SSL, adenomas with a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma, adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinomas and deep invasive adenocarcinomas. The correct histological prediction was defined by the histology report from a group of pathologists with expertise in digestive histology for HP (CONECCT IH), SSL (CONECCT IS), and deep invasive adenocarcinoma (CONECCT III). To differentiate adenomas with a very low risk of undetected adenocarcinoma (CONECCT IIA) from adenomas with a high risk of undetected adenocarcinoma and superficial adenocarcinomas (CONECCT IIC), the correct histological prediction was defined by an expert group of endoscopists from the SFED (JR, MP, JJ) who arrived at a consensus using the Delphi process, and for adenomas histology was used to detect presence of adenocarcinoma and therefore distinguish between risk of undetected adenocarcinoma. All resection pieces were fixed in buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin before being cut into 2-mm slices. Regarding treatment choice, trainees chose among the following: no resection, resection (preferably en bloc, but piecemeal acceptable), resection en bloc with free margins (R0) and surgery with lymphadenectomy. The correct treatment choice was in accordance with ESGE guidelines for each type of lesion. Overtreated lesions were defined as those for which a more invasive treatment than necessary was proposed and undertreated lesions as those for which a less invasive treatment than necessary was proposed.

Correctly predicted/treated lesions were those for which trainees chose both the correct histological prediction and treatment choice. At 3 to 6 months, trainees were also asked if they had used the CONECCT table on a daily basis since the first training session, and if they considered CONECCT useful for histological prediction and treatment choice in their routine practice.

Endpoints

The endpoints were:

histological prediction, treatment choice, and the mean of correctly predicted/treated lesions between pretest (step 2) and post-test (step 4), as well as between the first training session (pre-test and post-test) and the second training session 3 to 6 months later (T3 M)

Comparison between gastroenterology fellows and attending physicians

Overall number of overtreated, undertreated lesions, and unnecessary surgeries

Analysis by histological subtype (test results, over and undertreated)

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics and outcome variables were described by the mean and range for continuous variables, and by frequencies and percentages for categorical ones. Comparisons of proportions between time points were performed using a mixed logistic regression model to take into account the fact that an investigator classified multiple lesions, and that lesions were classified at different time points. Comparisons of proportions between investigators (fellows and attending physicians) were also performed by mixed logistic regression models to take into account the fact that the same investigator classified multiple lesions. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Excel software (Office, Microsoft, United States) or the R software (R Core Team 2018. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.)

Ethical concerns

All trainees received oral information about the study protocol and signed a written consent for participation. The protocol followed the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee (Comité d’éthique du Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire de Lyon).

Registration

The study was registered in the US National Clinical trial register under the number NCT03455595.

Results

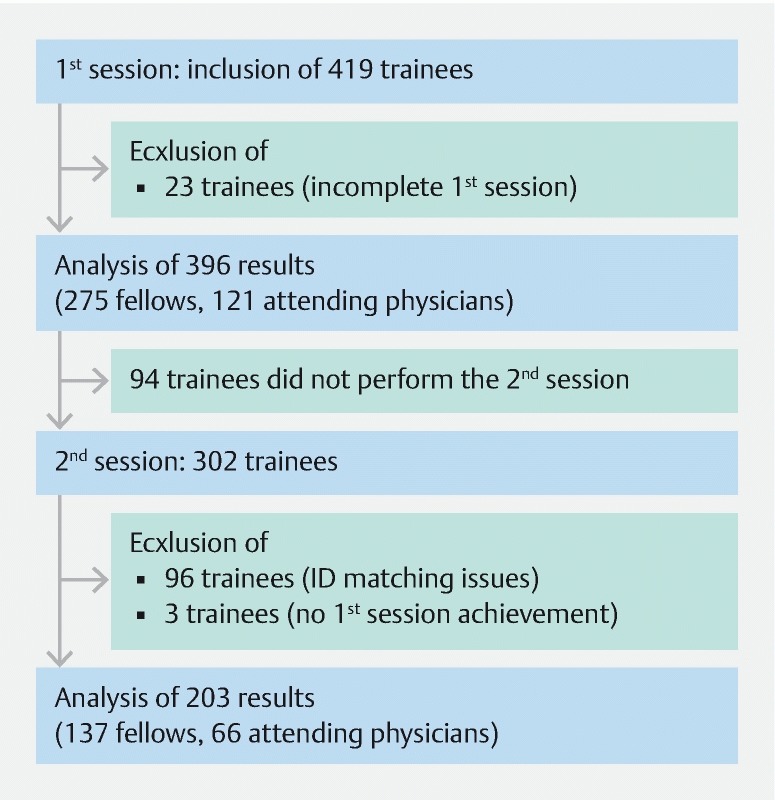

All training sessions took place between April 2017 and April 2018. A total of 419 gastroenterology fellows and attending physicians participated in the first training session; 23 were excluded because they had not performed the post-test, and therefore 396 trainees were analyzed (275 GI fellows, 121 attending physicians; Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the study.

A total of 302 gastroenterology fellows and attending physicians participated in the second training session; 99 were excluded because of ID matching issues (n = 96, either a failure to complete the ID or a change in the ID) or because the post-test during the first training session had not been performed (n = 3), and therefore 203 trainees were analyzed (137 GI fellows, 66 attending physicians; Fig. 2 ). Mean ± SD age of the gastroenterology fellows was 26.9 ± 1.9 years, and that of attending physicians 43.8 ± 11.9 years.

First training session, step 1 results

The Paris classification was used by 63.4 % of trainees, 28.5 % used the NICE classification, 36.8 % used the Kudo classification, 10.9 % used the Sano classification, and 7.6 % used the WASP classification. Overall, 1.5 % of the fellows and 9.9 % of the attending physicians used all classifications while 47.2 % and 13.2 % used any of them.

Results in the first training session (pretest and post-test)

At post-test compared to pretest, there was a statistically significant improvement in the mean proportion of correct histological prediction, from 60.5 to 76.2 % (+ 26.4 %, P < 0.001), and correct treatment choice, from 61.1 to 77.4 % (+ 26.8 %, P < 0.001). Mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions improved statistically significantly, from 51.0 % to 74.0 % (+ 45.1%, P < 0.001). Trainees improved their performances between pretest and post-test in 86.6 % of cases (343/396).

The pretest results of the attending physicians were statistically significantly better than those of gastroenterology fellows (73.9 % vs. 54.6 % for the histological prediction, 69.9 % vs. 57.2% for the treatment choice, both P < 0.001). Mean improvement in post-test results for gastroenterology fellows was statistically significantly higher than that for attending physicians (+ 34.8 % vs. + 11.1 % for the histological prediction, 31.6 % vs. 17.9 % for the treatment choice, both P < 0.001; Table 1 ).

Table 1. Overall results of histological prediction and treatment choice.

| Histological prediction | Treatment choice | Well-predicted and well-treated lesions | |||||||

| Pre-T | Post-T | T3 M | Pre-T | Post-T | T3 M | Pre-T | Post-T | T3 M | |

| Overall (%) | 60.5 | 76.2 | 70.3 | 61.1 | 77.4 | 70.9 | 51.0 | 74.0 | 66.6 |

| Fellows (%) | 54.6 | 73.6 | 65.5 | 57.2 | 75.3 | 66.4 | 45.0 | 71.5 | 59.1 |

| Attending physicians (%) | 73.9 | 82.1 | 80.4 | 69.9 | 82.4 | 80.3 | 63.9 | 79.9 | 78.9 |

Pre-T, pretest; Post-T, Post-test; T3 M, second training session

Results in the second training session (T3 M)

At T3 M compared to pretest, there was a statistically significant improvement in mean proportion of correct histological prediction, from 60.5 to 70.3 % ( + 16.2 %, P < 0.001), and correct treatment choice, from 61.1 to 70.9 % (+ 16.0 %, P < 0.001). The mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions improved statistically significantly, from 51.0 % (4040/7920) to 66.6 % (5408 /8120; + 30.6 %, P < 0.001; Table 1 ). Trainees improved their performances between pretest and T3 M in 75.4 % of cases (153 /203).

Mean proportion of correct answers for fellows and attending physicians were 73.6 % and 82.1 % for histological prediction, respectively, and 75.3 % and 82.4 % for treatment choice, respectively. Compared to the pretest results, a statistically difference in favor of the T3 M was seen for the fellows ( + 34.8 % and + 31.6 %, both with P < 0.001) and for the attending physicians (+ 11.1 % and + 17.9 %, both with P < 0.001).

Decrease in the mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions between the end of the first training session (post-test) and the second training session (T3 M) was more pronounced for the fellows than for the attending physicians (–17.3 % for the fellows vs –1.3 % for the attending physicians, P < 0.001; Table 1 ).

Overall number of over and undertreated lesions and unnecessary surgeries

At post-test compared to pretest, there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of overtreated lesions, from 30.1 % (2383/7920) to 15.5 % (1227/7920; – 48.8 %, P < 0.001) and in the number of undertreated lesions, from 8.0 % (633/7920) to 6.7 % (530/7920; – 16.3 %, P < 0.001). Also, colorectal lesions were statistically significantly more overtreated than undertreated (30.1 vs 8.0 %, P < 0.001).

At T3 M compared to pretest, there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of overtreated lesions, from 30.1 % to 18.5 % (1504 /8120; – 38.5 %, P < 0.001). There was a statistically significant improvement in the number of undertreated lesions, from 8.0 % to 9.7 % (787 /8120; + 21.1 %, P = 0.01).

The number of unnecessary surgeries was statistically significantly reduced, from 8.6 % (683/7920) at pretest to 6.3 % (496/7920) at post-test (–27.4 %, P < 0.001), to 5.7 % (467/8120) at T3 M (–33.7 %, P < 0.001).

Analysis by polyp subtype

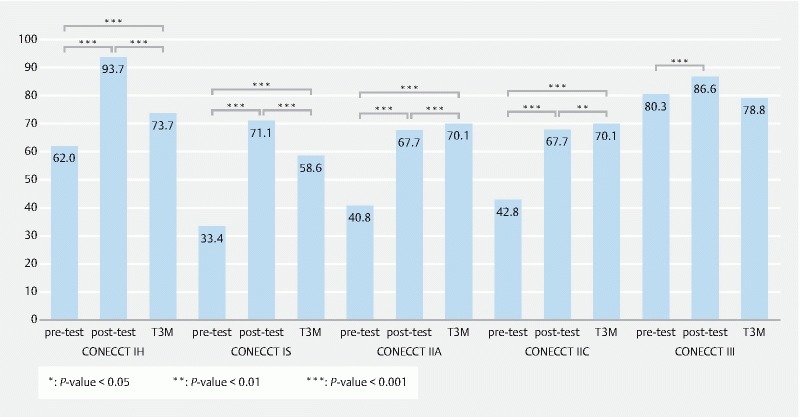

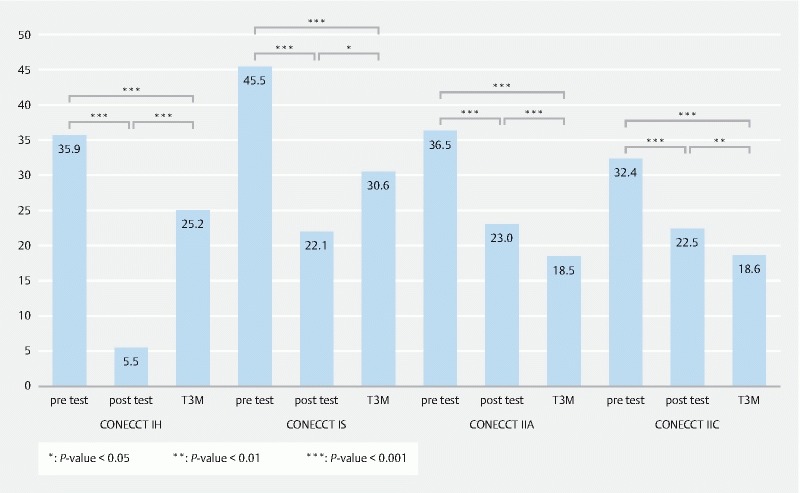

Regarding lesions CONECCT IH, mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions was 62.0 % at pretest, 93.7 % at post-test and 73.7 % at T3 M. The differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.001; Fig. 3 ). Mean proportion of overtreated lesions were 35.9 % at pretest, 5.5 % at post-test and 25.2 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.001; Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 3 .

Mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions by subtype of polyp.

Fig. 4.

Mean proportion of overtreated lesions by subtype of polyp.

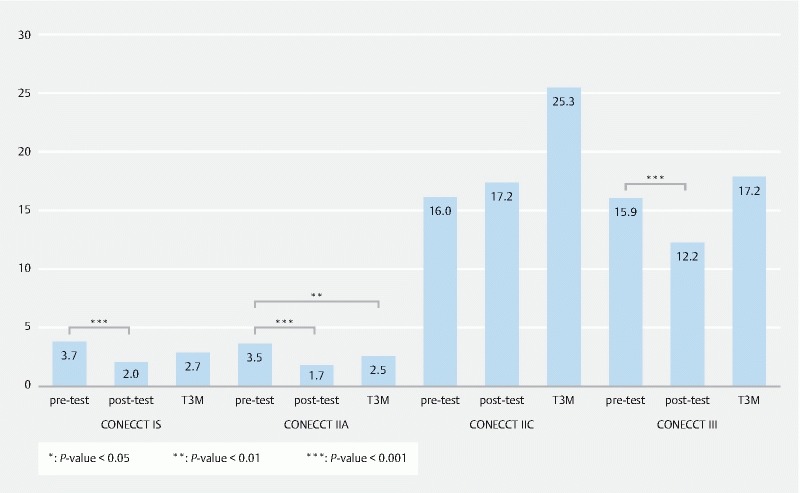

Regarding lesions CONECCT IS, mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions were 33.4 % at pretest, 71.1 % at post-test and 58.6 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.001; Fig. 3 ). Mean proportion of overtreated lesions were 45.5 % at pretest, 22.1 % at post-test and 30.6 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.05; Fig. 4 ). Mean proportion of undertreated lesions was 3.7 % at pretest, 2.0 % at post-test and 2.7 % at T3 M. Differences were only statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001; Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Mean proportion of undertreated lesions by subtype of polyp.

Regarding lesions CONECCT IIA, mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions were 42.8 % at pretest, 67.7 % at post-test and 70.1 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.001; Fig. 3 ). Mean proportion of overtreated lesions were 36.5 % at pretest, 23.0 % at post-test and 18.5 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.001; Fig. 4 ). Mean proportion of undertreated lesions was 3.5 % at pretest, 1.7 % at post-test and 2.5 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001) and between pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.01; Fig. 5 ).

Regarding lesions CONECCT IIC, mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions were 42.8 % at pretest, 57.6 % at post-test and 52.2 % at T3 M. Difference were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.01; Fig. 3 ). Mean proportion of overtreated lesions were 32.4 % at pretest, 22.5 % at post-test and 18.6 % at T3 M. Differences were statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001), pretest and T3 M ( P < 0.001) and post-test and T3 M ( P < 0.01; Fig. 4 ). Mean proportion of undertreated lesions was 16.0 % at pretest, 17.2 % at post-test and 25.3 % at T3 M. Differences were not statistically significant ( Fig. 5 ).

Regarding lesions CONECCT III, mean proportion of correctly predicted/treated lesions were 80.3 % at pretest, 86.6 % at post-test and 78.8 % at T3 M. Differences were only statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001; Fig. 3 ). Mean proportion of undertreated lesions were 15.9 % at pretest, 12.2 % at post-test and 17.2 % at T3 M. Difference was only statistically significant between pretest and post-test ( P < 0.001; Fig. 5 ).

Value of the CONECCT TABLE

At T3 M, 87.0 % of the trainees considered the CONECCT table to be a useful tool to predict histology of a colorectal polyp, and 89.0 % for choosing a treatment. At T3 M, 40.3 % of trainees routinely used CONECCT.

Discussion

The current study found that a teaching program of the CONECCT table is effective in improving histological prediction and treatment choice for colorectal polyps in both fellows and attending physicians specializing in gastroenterology. The benefits of this program were found regardless of the type of lesion and personal experience. In clinical practice, this improvement yielded a reduction of under- and overtreatment of colorectal polyps and could thus potentially impact treatment of these lesions. Furthermore, there was a persistent statistically significant improvement after 3 to 6 months.

For each subtype of polyps, there was a statistically significant improvement between pretest and post-test in histological prediction and treatment choice. These results are encouraging, particularly for CONECCT IH lesions, because the minimal 95 % threshold of correct characterization required for the “not-resect” strategy of the ESGE guidelines is almost reached in the post-test 12 . On the other hand, performance for characterization of the lesions CONECCT IIA are still far from the same 95% threshold of correct characterization using NBI to introduce the “Resect and Discard” strategy of the ESGE guidelines in routine practice 12 . SSL were the least correctly characterized before the teaching course and a minority of trainees reported using the recent WASP classification 10 . The teaching program CONECCT allowed them to make statistically significant progress in histology prediction of and treatment choice for these lesions. Endoscopic recognition of the landmarks of superficial and invasive carcinoma is crucial. In cases of invasive adenocarcinomas, potential resection is surgical to allow resection of both the invaded colon and the potentially metastatic lymph nodes. The participants already characterized and treated invasive cancers correctly before the program, but did improve at post-test. Conversely, superficial adenocarcinomas (invasion limited to the mucosa or the first 1000 microns of the submucosa) have no risk of lymph node metastasis and, therefore, overestimation of advancement of such cancerous lesions may lead to unnecessary surgery 12 13 that is associated with 24 % morbidity and 0.5 % mortality 14 . Superficial adenocarcinomas are best addressed by en bloc endoscopic resection with free margins, as it achieves a curative goal with organ preservation 3 15 and ESD is safer than surgery as it is associated with 5 % rate of perforation, but less than 1 % of subsequent salvage surgery 16 17 . Endoscopic recognition of superficial adenocarcinomas is therefore key to reduce the frequency of unnecessary surgery 14 .

In the current study, CONECCT teaching program led to an improvement in histology prediction and treatment choice for superficial adenocarcinomas. This diagnostic performance is far from sufficient in this setting despite being an encouraging first step. Based on all these considerations and also because participants regressed for each subtype of polyp outside the lesions CONECCT IIA for which there is indeed a statistically significantly progression, multiple training sessions with polyp recognition seem warranted to achieve better diagnostic rates.

The current study found that fewer than 5 % of participants use all the classifications necessary to predict histology of a polyp and thus choose the appropriate treatment. Merging all these classifications as does the CONECCT table therefore seems important even if having five types of lesions in one table may appear more complex. However, it allows characterization of all types of colorectal polyps frequently found in clinical practice.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the criteria gathered in the CONECCT table have been validated under different endoscopic conditions; certain criteria have been validated using a zoom and virtual chromoendosocopy (JNET 8 , NICE 7 ), while others have been validated with indigo carmine and crystal violet dye (Kudo Classification 6 ). To use the CONECCT table would therefore require access, in real-time, to all these conditions, which is not feasible, and in any case many of these modalities are not very widespread in common practice in France.

This study demonstrates the value of such a tool, but it does not validate a new classification. A prospective evaluation is ongoing to validate use of this table. Second, as mentioned above, still frames (taken by expert endoscopists) were used herein. This signifies that the detection process of colorectal lesions is bypassed. In clinical practice, detection rates vary among endoscopists. Performance of the trainees was probably overestimated given that certain lesions would potentially have been missed in real life. Furthermore, the still frames used were taken by different endoscopists, thus introducing variability regarding their quality, which in turn may have impacted characterization during the training sessions. Third, the CONECCT table was not compared to a validated classification (such as teaching tools). Lastly, we used the same still frames for the pretest and post-test, introducing memorization bias, but we chose this design to compare polyps with the same difficulty of histological prediction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the CONECCT teaching program is effective in improving histological prediction and treatment choice performance, regardless of the type of colorectal polyp considered, and for both gastroenterology fellows and attending physicians. Despite these encouraging results, further sessions are needed to maintain or improve the level of participants. A validation study for this table is currently underway.

Acknowledgements

This pedagogic work received the FARE grant from the national French society of gastroenterology (SNFGE) and the SFED-Norgine research grant delivered by the French society of digestive endoscopy (SFED).

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Atkin W S, Valori R, Kuipers E J et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition – Colonoscopic surveillance following adenoma removal. Endoscopy. 2012;44:SE151–SE163. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman D A, Rex D K, Winawer S J et al. Guidelines for Colonoscopy Surveillance After Screening and Polypectomy: A Consensus Update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–857. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:829–854. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3–S43. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oka S, Tanaka S, Kanao H et al. Therapeutic strategy for colorectal laterally spreading tumor. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2009;21:S43–S46. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T et al. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:8–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett D G et al. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: validation of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumimoto K, Tanaka S, Shigita K et al. Clinical impact and characteristics of the narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:816–821. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uraoka T, Saito Y, Ikematsu H et al. Sano’s capillary pattern classification for narrow-band imaging of early colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc Off J Jpn Gastroenterol Endosc Soc. 2011;23:112–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IJspeert J EG, Bastiaansen B AJ, van Leerdam M E et al. Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016;65:963–970. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada M, Saito Y, Sakamoto T et al. Endoscopic predictors of deep submucosal invasion in colorectal laterally spreading tumors. Endoscopy. 2016;48:456–464. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-100453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:270–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deprez P H, Bergman J J, Meisner S et al. Current practice with endoscopic submucosal dissection in Europe: position statement from a panel of experts. Endoscopy. 2010;42:853–858. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roy F, Manfredi S, Hamonic S et al. Frequency of and risk factors for the surgical resection of nonmalignant colorectal polyps: a population-based study. Endoscopy 2016 Mar. 48:263–270. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C K, Shim J-J, Jang J Y. Cold snare polypectomy vs. Cold forceps polypectomy using double-biopsy technique for removal of diminutive colorectal polyps: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1593–1600. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y et al. A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1217–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saito Y, Fukuzawa M, Matsuda T et al. Clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal tumors as determined by curative resection. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0562-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]