Abstract

Background and aim Transabdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomographic scanning (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are established diagnostic tools for liver diseases. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography is used to perform hepatic interventional procedures including biopsy, biliary drainage procedures, and radiofrequency ablation. Despite their widespread use, these techniques have limitations. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), a tool that has proven useful for evaluating the mediastinum, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, and biliary tract, has an expanding role in the field of hepatology complementing the traditional investigational modalities. This review aimed to assess the current scientific evidence regarding diagnostic and therapeutic applications of EUS for hepatic diseases.

Introduction

Transabdominal ultrasound (US), computed tomographic (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are established diagnostic tools for liver diseases. In addition, percutaneous interventions, most commonly with US or CT-guidance, are often used to perform a wide range of liver and biliary interventional procedures, including: vascular interventions (as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and transjugular liver biopsy), percutaneous interventions (such as liver biopsy, collections/abscess drainage and transhepatic biliary interventions, namely percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and/or biliary drainage) and interventional oncologic therapeutic procedures (such as transarterial tumor embolization [hepatic radioembolization] and tumor ablations using thermal ablation techniques [radiofrequency ablation]). Despite their widespread use, these techniques have limitations. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), a first-line investigation method for evaluation of the mediastinum, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, and biliary tract, has an expanding role in the field of hepatology complementing the traditional investigational modalities. We aimed to review the current scientific evidence regarding diagnostic and therapeutic applications of EUS for hepatic diseases.

Search strategies and criteria

A search was performed in Pubmed with the keywords (liver OR hepatic) and (EUS OR "endoscopic ultrasound") and (diagnosis OR diagnostic OR treatment OR therapeutic OR ablation OR intervention). Inclusion criteria were: case reports, series, clinical studies, studies in animal models and reviews regarding EUS applications in liver disorders, including portal hypertension. Reports about the use of EUS in extrahepatic bile duct, gallbladder, and other extrahepatic structures were excluded. Non-English language literature without an English translation was also excluded. On March 4, 2018, the search yielded 1095 articles, 201 of which were included in this review.

Diagnostic role of EUS in liver disease

Technical considerations

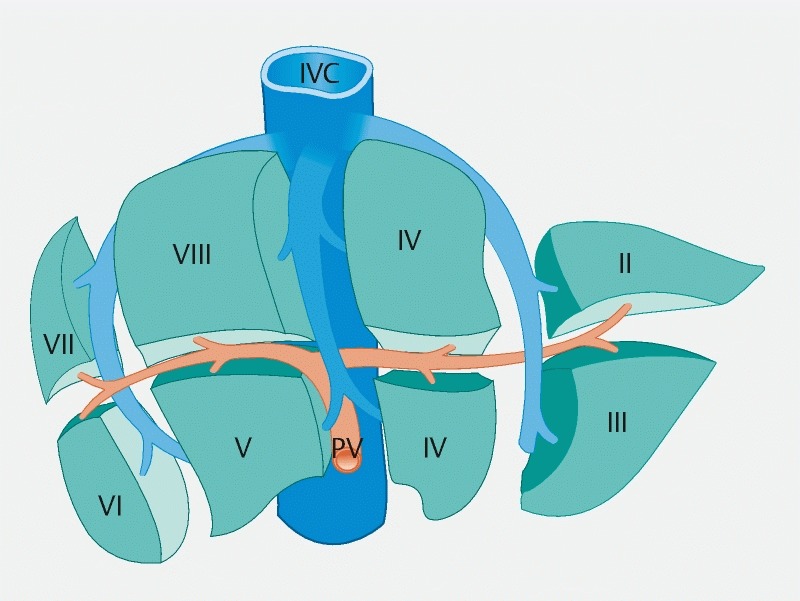

To evaluate the liver with EUS, one must first take into account that its perspective of liver anatomy is much different from US or CT images and requires three-dimensional conceptualization of the liver parenchyma. The Couinaud classification 1 is the most widely used system to describe liver anatomy and divides the liver into eight (I-VIII) functionally independent units, termed segments, based on planes through the hepatic veins (HV) and the bifurcation of the main portal vein (PV) ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Liver segments described by Couinaud 1 .

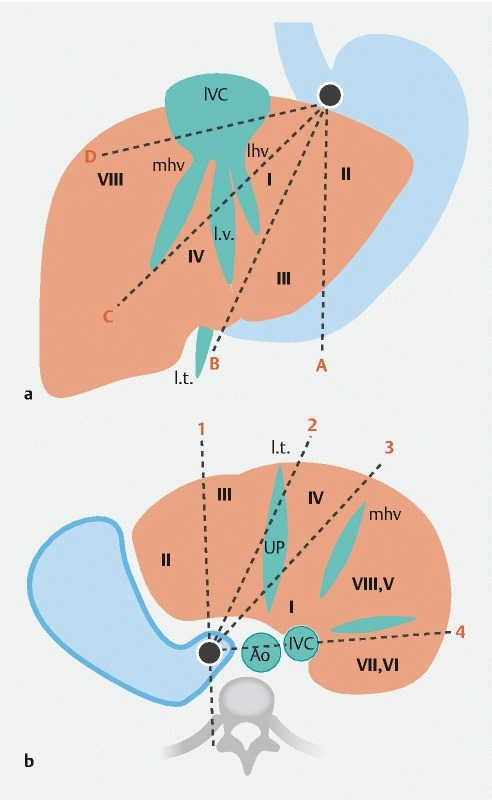

With EUS, these liver segments are recognized by identifying the following structures: (1) PV branches with thick and hyperechoic walls, Doppler positive; (2) HV branches (left and middle) with thin and non-reflective walls, straight course, Doppler positive; (3) biliary radicals with hyperechoic walls, irregular course, Doppler negative; (4) ligaments (venosum and teres) with thick and hyperechoic structures without lumen, extending between vessels and liver capsule; and (5) surface landmarks (gallbladder, falciform ligament and liver hilum). The longitudinal and cross-sectional schematic representations of linear EUS ( Fig. 2 ) through the liver from the proximal stomach with a clockwise probe rotation from A-D ( Fig. 2a ) and from 1 – 4 ( Fig. 2b ) must be taken into account.

Fig. 2 a.

Longitudinal and b cross-sectional schematic representations of linear EUS scans through the liver from the proximal stomach 2 . MHV, middle hepatic vein; LHV, left hepatic vein; UP, umbilical part of the left portal vein; Ao, aorta.

A step-by-step endosonographic evaluation of the liver is performed as described by Bhatia et al. 2 . From the stomach, it is possible to evaluate the left lateral segments (segments II and III), as well as the umbilical part of the left PV and ligamentum teres (l.t.), the medial segment of the left lobe (segment IV), ligamentum venosum (l.v.), the caudate lobe (segment I), the inferior vena cava (IVC), the right lobe (segments V and VIII) and the liver hilum. From the duodenal bulb, segments VI and VII, the hepatoduodenal ligament structures and PV and hepatic artery (HA) branches, the liver hilum and the segmental divisions of right PV and HA are visualized.

EUS has several potential advantages over other imaging modalities regarding optimal visualization of the liver: the EUS transducer can be positioned closely to the liver thereby avoiding interposing structures (such as rib cage, bowel loops, gallbladder, pleural space, ascites and a thickened abdominal wall, which are all well-known limitations of, for example, transabdominal ultrasound 3 ), and it has the potential to thoroughly evaluate the left liver lobe, hilum and deeply-located areas of the liver, such as the caudate lobe. One potential limitation is the evaluation of the right lobe. It is examined from the duodenum, which is technically difficult because of the small endosonographic window and is possibly further compounded by the limited depth of penetration of the ultrasound waves 4 .

Doppler ultrasound, through different implementations (as continuous-wave, pulsed-wave, color and power Doppler), can be used to identify blood flow in vessels. It is useful for characterizing liver anatomy, identifying interposed vessels during punctures and evaluating portal hypertension (PHT). Regarding vascular changes in PHT, EUS-Doppler has a distinct advantage over endoscopy, as it can reveal not only gastroesophageal varices, but also collaterals adjacent to or outside the wall such as periesophageal collateral veins (peri-ECV), paraesophageal collateral veins (para-ECV) collaterals and perforating veins 5 6 7 8 9 . Moreover, EUS can more accurately determine their size and wall thickness 10 and assess hemodynamic changes in portal and azygos veins and left gastric vessels, important parameters to consider for bleeding management.

Real-time elastography is another helpful tool that provides color-coded images and semi-quantitative measurements related to tissue stiffness of liver parenchyma and focal lesions as an additional tool in determining the etiology of the lesion. The need for manual tissue pressure required during standard transabdominal US elastography is overcome by comparing the ultrasound signals obtained over several seconds of normal breathing and blood circulation 11 . Also important is that elastography imaging via EUS is not limited by ascites and thickened abdominal wall 3 .

Contrast-Enhancement (CE) is an emerging technique that is becoming more and more available to improve US and EUS diagnostic performance of focal liver lesions. CE-EUS is categorized into two types: CE-EUS with the Doppler method (CE-EUS-D) and CE-EUS with harmonic imaging (CE-EUS-H). CE-EUS-D helps distinguishing between vascular-rich and hypovascular areas of a target lesion. CE-EUS-H provides a more detailed vasculature image of the target lesion. Both modes can be obtained to characterize a target lesion, and can be used depending on the purpose. Few US contrast agents are available worldwide, Sonovue and Sonazoid being the most widely used. These are made of microbubbles with a shell of phospholipids that are filled with sulfur hexafluoride gas. Since they are confined to the vessels after injection, it allows visualization of the tiny vessels in the capillary bed and therefore dynamic detection of capillary microvascularization. Given the dual blood supply of the liver, from the portal vein and the hepatic artery, three vascular phases can be observed with this ultrasound contrast: the arterial phase, beginning within 20 seconds after the injection and continuing for 30 to 45 seconds; the portal venous phase, that lasts up to 120 seconds; and then the late phase which persists until clearance of the US contrast agent from the circulation (usually 6 minutes). CE-EUS has several advantages over CT and MRI 12 : (1) It is performed in real time; (2) The contrast is not excreted by the kidneys, thus it does not need pre-investigational renal function testing and it can be used in patients with renal insufficiency, where contrast-enhanced CT or contrast-enhanced MRI are contraindicated; (3) Confinement in the vascular space without extravasation into the interstitial fluid allows a prolonged enhancement of the vascular system and the evaluation in the different vascular phases previously described; (4) It has a much higher resolution compared to other imaging modalities, enabling full study of the enhancement dynamics of lesions; and (5) It has an excellent tolerance and safety profile that makes it appropriate for repeated follow-up examinations.

EUS guided-liver biopsy (EUS-LB) may be safer than its percutaneous counterpart for performing hepatic tissue sampling in patients with coagulation disorders, such as those with liver cirrhosis 13 14 . The 19-gauge biopsy needle, which is smaller than the 16-gauge needles traditionally used in transcutaneous LB, can be oriented under direct vision into the liver for sampling avoiding puncturing larger vessels 15 . Abdominal skin surgical scars, ascites or dense abdominal wall thickness are also not limitations. Few studies compared the yield of percutaneous versus EUS-guided liver sampling, concluding that specimen adequacy and diagnostic yield are at least comparable between both techniques, ranging from 90 % to 100 % 16 . Recently, a comparison between “blind” liver biopsies using different commercially available 19-gauge needles (Cook Echotip Procore, Olympus EZ Shot 2, Boston Scientific Expect Slimline, Covidien SharkCore) was performed and the Covidien Sharkcore needle produced statistically superior histological specimen by capturing more complete portal tracts, possible due to its design 17 .

Focal liver lesions

EUS is a useful adjuvant to CT and MRI in diagnosing and characterizing focal liver lesions (FLL) 18 19 . Several studies 4 20 21 22 have showed superiority of EUS over CT in detecting FLL, especially when they are small (< 1 cm) or located in the left lobe or hilum. Awad et al. showed that EUS could diagnose additional hepatic lesions in 28 % of patients with a history of known liver mass that were detected initially by CT 20 .

Aside from detection, EUS may differentiate the etiology of these lesions using several tools.

First, a validated EUS scoring system has been developed, with a positive predictive value of 88 % 23 . With this system, the presence or absence of certain criteria increases the accuracy to differentiate between malignant, benign or indeterminate FLL. Benign solid FLL are distinct hyperechoic and/or have a distinct geographic shape, while malignant lesions must have at least three of the following characteristics: two components (with isoechoic/slightly hyperechoic center or without isoechoic/slightly hyperechoic center), post-acoustic enhancement, adjacent structures distortion, hypoechogenicity (slightly or distinctly) and/or at least 10 mm.

Second, EUS-elastography has been described in two studies 24 25 as a valuable tool in detecting, characterizing and differentiating between benign and malignant FLL with sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of 92.5 %, 88.8 % and 88.6 %, respectively. More high-quality data are needed to confirm the potential of EUS-elastography in this field.

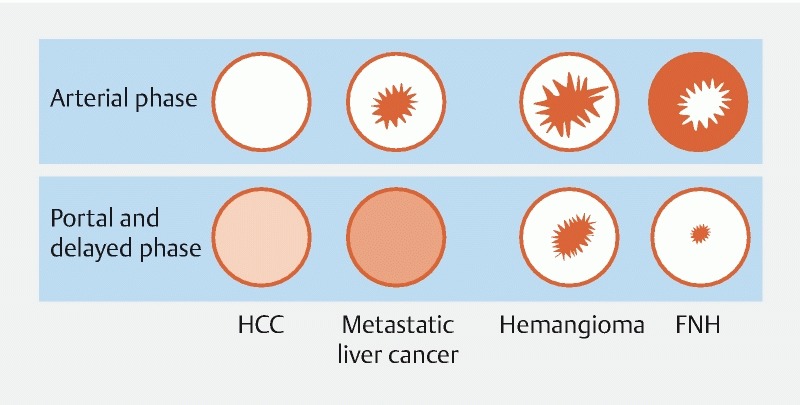

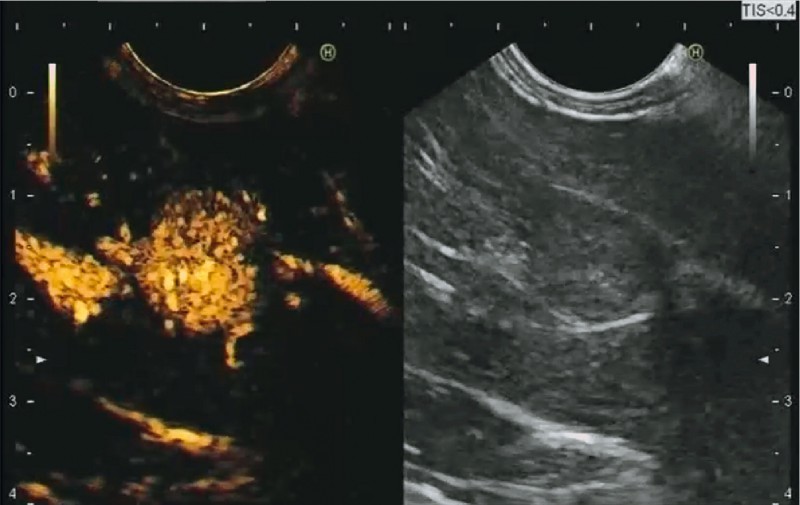

Third, differentiation between different types of FLL can also be studied through vascular enhancement patterns with CE-EUS, as is also done with CE-US 26 ( Fig. 3 ). Typical enhancement patterns are arterial hyperenhancement with subsequent slow washout in late-phase contrast in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), arterial hyperenhancement with rim-like enhancement and subsequent rapid washout in metastatic liver cancer 27 ( Fig.4 ), peripheral nodular hyperenhancement, with centripetal progressive fill-in in hemangioma, and arterial hyperenhancement with progressive, centrifugal complete, early, spoke-wheel arteries, unenhanced central scar in focal nodular hyperplasia 28 .

Fig. 3.

Typical enhancement patterns of FLL with contrast-enhanced ultrasound.

Fig. 4.

CE-EUS in liver metastases, with arterial hyperenhancement with rim-like enhancement.

Moreover, CE-US recently has been considered a useful tool for evaluating the effects of treatment of HCC. It can dynamically observe tumor vessel perfusion with superior diagnostic performance for residual tumors after transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) compared to CE-CT (sensitivity and accuracy of detecting residual tumor with CE-US 95.6 % and 96.2 % versus CE-CT 76.2 % and 77.7 %, respectively) 29 . For this particular indication, CE-EUS could be of value, with the advantage of better examining the deeper liver lesions not visualized with CE-US 30 . However, this needs further confirmation.

In addition to the tools described above, EUS-guided tissue sampling can confirm a HCC diagnosis and avoid unnecessary surgery 22 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

EUS-guided tissue sampling of a hepatic malignant lesion.

Currently, EUS-guided sampling is indicated “if the pathological result is likely to affect patient management and the lesion is poorly accessible/not detected at percutaneous imaging or a sample obtained via the percutaneous route repeatedly yielded an inconclusive result” 15 . If cytohistopathological results are inconclusive, KRAS mutation can be analyzed as it provides high diagnostic yield in EUS-guided histopathological evaluation 49 . To reduce the number of needle passes and potential adverse events (AEs), novel ancillary techniques are being developed. A recent study 50 conducted in animal models demonstrated technical feasibility of in vivo cytological observation using a high-resolution microendoscopy (HRME) system under EUS guidance. The authors concluded that HRME could obtain clear images representing cytology-level morphology of liver and would therefore improve diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA for liver lesions. EUS-FNA may also play a significant role in staging HCC in patients with cirrhosis with PV thrombus by differentiating a tumor thrombus from a clot, as its etiology is difficult to assess in the absence of characteristic hallmarks 51 52 53 54 55 . This is of paramount importance in HCC management, as patients with tumor invasion into the PV are deemed to have unresectable disease and to be ineligible for transplant 56 . EUS-FNA of splenic vein thrombus has also been performed to clarify its etiology (benign versus malignant) 57 . A systematic review concerning complications related to EUS-guided sampling showed a 2.33 % rate of morbidity (bleeding, infection, pain, fever) and 0.29 % rate of mortality (due to uncontrollable cholangitis) after 344 EUS-FNA of hepatic lesions 58 . Due to the long path required to reach the liver capsule and the fact that HCC is more vascular in comparison with other cancers (for example, pancreatic), one could presume a higher risk of tumor spillage into the peritoneal cavity along the needle track. Nonetheless, no such cases have been reported so far.

Lastly, convex EUS-Doppler can provide staging information regarding vascular invasion at the hepatic hilum, an important parameter to evaluate in, for example, peri-hilar cholangiocarcinomas 59 .

Liver cirrhosis

Detection of liver fibrosis has important management and prognostic implications. Traditionally, liver biopsy is considered the “gold standard” diagnostic method for identifying liver cirrhosis, but has drawbacks regarding sampling errors, inter-observer variability and complications 60 . Noninvasive fibrosis markers, such as liver stiffness measurements (transient elastography – Fibroscan – and real-time elastography), have been developed to overcome these problems. Nonetheless, applicability of these measurements with a transabdominal approach is lower in cases of obesity or ascites and in discriminating between intermediate stages of fibrosis 60 . In addition, real-time elastography, used in EUS, can be advantageous over transabdominal Fibroscan, as it can estimate liver stiffness in all patients (either obese or not) and has the potential to differentiate between fibrosis and steatosis, as liver steatosis has a distinct appearance on real-time sono-elastography images, with low mean hue histogram values 61 . Further studies are needed, however, to confirm these hypotheses.

If histological confirmation is needed, EUS-guided LB is a safe technique with a diagnostic yield for liver parenchymal disorders such as liver cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis and NAFLD between 91 % and 100 % 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 , which is at least comparable to percutaneous or transjugular routes 16 74 75 . Few complications have been reported with this technique. Four self-limited pericapsular hematomas 72 73 74 , two cases of duodenal perforations 23 , one self-limited bleeding 62 and a case of a near-fatal hemorrhagic shock after EUS-LB 76 have been reported so far. Data on patient preference regarding being submitted to a percutaneous versus EUS liver biopsy are missing.

Portal hypertension

Detecting vascular changes within and outside of the upper digestive wall

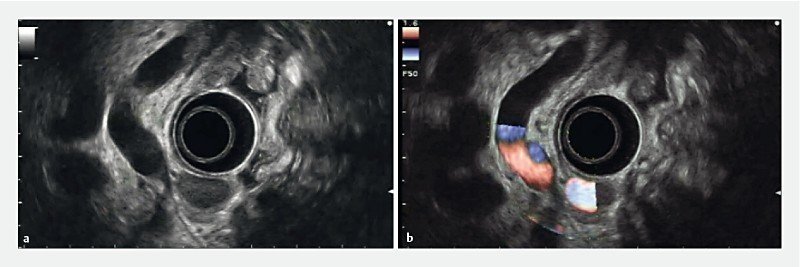

EUS-Doppler has a higher sensitivity for detecting esophageal and gastric varices compared to upper endoscopy 5 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 ( Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Fundus varices in EUS a without Doppler and b with EUS-Doppler.

It is also a useful modality for evaluating ectopic duodenal varices 86 87 88 89 90 . The higher the grade of esophageal varices, the higher the EUS sensitivity 82 . Success in visualizing small esophageal varices by EUS can be improved by using small water-filled balloons 77 , small 20-Hz ultrasound transducers 91 92 , videotaped high-resolution endoluminal sonography 81 or high-frequency ultrasound miniature probes 93 .

EUS-doppler can diagnose collateral veins, which are found adjacent to or outside the esophageal wall in patients with esophageal varices 5 6 7 8 9 . There is a correlation between grade of esophageal varices and development and diameter of para-ECV 5 and between diameter of the splenic vein and diameter of these collaterals 94 .

EUS-Doppler can also substantiate diagnosis of portal gastropathy, showing diffuse thickening of the gastric wall with dilated paragastric veins 6 95 , thereby distinguishing it from watermelon stomach , which is characterized by focal swelling and spongy appearance in mucosa and submucosa 96 97 . It is also valuable in differential diagnosis of giant gastric folds 98 99 , distinguishing benign causes, such as gastric varices, from malignant causes.

Dynamic assessment of hemodynamic changes

The hepatic venous portal pressure gradient or portal pressure gradient (PPG) reflects the degree of PHT and is the single best prognostic indicator in liver disease. Currently, PPG measurement via right jugular vein access is considered the gold standard. Nonetheless, this is an indirect invasive measurement because it relies on a wedge pressure to assess portal vein pressure, and may not always accurately reproduce true PV pressures. EUS-guided PV catheterization was developed to overcome drawbacks of the transjugular approach. It was first performed in porcine models 100 101 102 103 104 105 , appearing feasible and safe for portal pressure measurements as well as for portal angiography and pressure measurements. The first human clinical report was made by Fuji-Lau et al. 106 . Later, a human study 106 107 involving 28 patients demonstrated a 100 % technical success and no AEs in measuring the PPG with a linear echoendoscope, a 25G FNA-needle and a compact manometer. An excellent correlation was found between PPG measurement, clinical evidence of PHT, and clinical suspicion of liver cirrhosis. Larger clinical trials and comparative studies between both approaches are needed to confirm and establish the role of this technique.

Prediction of variceal bleeding and rebleeding

Elevated intravariceal pressure is associated with risk of variceal bleeding. In 1999, Jackson et al. developed a technique for directly measuring esophageal variceal wall tension using an ultrasonographic transducer and needle puncture of the varix 108 . Later, to avoid risk of variceal bleeding from needle puncture, Miller et al. 109 110 developed a noninvasive EUS-based device by which they successfully measured intravariceal pressure in a varix model by placing a 20-MHz ultrasound transducer in a latex balloon catheter sheath and attaching the catheter to a pressure transducer. Another indirect measurement of intravariceal pressure has been developed using EUS-Doppler-guided manometry of esophageal varices, using a linear EUS probe with power Doppler to assess flow in the varices and a manometry balloon attached to the tip of the probe 111 . Nonetheless, despite being promising, none of these methods are in widespread use today.

Other EUS predictors have also been found in relation to risk of variceal bleeding. Hematocystic spots on the surface of esophageal varices, identified in EUS as saccular aneurysms, are closely associated with high risk of variceal rupture 81 112 . By summing the cross-sectional surface area of all esophageal varices in the distal esophagus with digitized image, EUS can predict the risk of variceal bleeding: for each 1 cm 2 increase in variceal cross-sectional surface area (CSA) the risk of variceal bleeding increases 76-fold per year 113 . Using a cutoff value for the CSA of 0.45 cm 2 , sensitivity and specificity for future variceal bleeding above and below this point are 83 % and 75 %, respectively 113 . Furthermore, high blood flow variceal velocities and thin gastric variceal wall (mean thickness of the gastric wall of 1.2 ± 0.2 mm) correlate with greater bleeding risk 114 . Number and size of para and peri-ECV 115 116 and perforating veins 117 118 are also associated with risk of variceal bleeding.

EUS has a predictive value identifying rebleeding risk from esophageal varices by evaluating the type and grade of esophageal collaterals and cardiovascular structures 80 119 120 . Collateral vessels in the vicinity of gastric cardia improve after endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL), indicating that esophageal varices can be treated by EVL even though they connect with cardia varices. Their disappearance is associated with longer periods free from recurrence of esophageal varices 121 . Patients with peri-ECV and perforator veins 77 115 122 123 124 and/or with large para-ECV 83 116 125 126 127 128 are more likely to experience variceal recurrence and rebleeding. EUS can clearly predict recurrence of esophageal varices following EVL with a sensitivity and specificity of 89.2 % and 90.5 %, respectively 124 .

Paraesophageal diameter after EVL is a better recurrence predictor, because it has a lower cut-off parameter, higher sensitivity, and higher area under a ROC Curve (AUROC) (4 mm, 70.6 % sensitivity, 84.6 % specificity, 0.801 AUROC) 127 . A study using balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for management of gastric varices concluded that presence of esophageal varices and high gastric variceal resistance index assessed by EUS (≥ 0.24) before the procedure were significant risk factors for worsening of esophageal varices after obliteration 129 . Velocity of hepatofugal blood flow in the left gastric vein trunk can be determined, and also the branching pattern, both of which are associated with variceal recurrence after endoscopic treatments (anterior branch dominance and flow velocity of 12 c/s or more are associated with higher variceal recurrence) 118 124 130 131 .

Assessment of pharmacological effects

Variceal rupture results from increased variceal wall tension, which according to Laplace’s law, is determined by transmural pressure difference, size and wall variceal thickness. Based on this formula, few studies have shown that EUS morphological assessment of varices (column radius and volume) combined with simultaneous pressure measurement are objective and useful tools for risk stratification 132 133 . The effects of somatostatin, octreotide, and terlipressin on azygos blood flow in patients with portal hypertension have also been well evaluated by EUS. EUS is capable of documenting a marked decrease of the azygos blood flow after injection of vasoactive agents, showing a potential role for monitoring pharmacological effects on the superior porto-systemic collateral circulation and portal venous flow in patients with portal hypertension 134 135 136 .

In sum, there are several potential clinical applications of EUS in portal hypertension, namely in the evaluation of vascular changes of the digestive wall (through evaluation of esophageal and gastric varices, collateral veins and portal gastropathy), dynamic assessment of hemodynamic changes (through EUS-guided PV catheterization), prediction of variceal bleeding and rebleeding (through intravariceal pressure measurements, evaluation of hematocystic spots, summing the cross-sectional surface area of EV, calculation of type and grade of collateral veins) and assessment of pharmacological effects. Nonetheless, despite the multiplicity of possible uses, EUS currently does not have an established role in clinical practice to explore portal hypertension. More efficacy and safety data are needed.

Therapeutic role of EUS

EUS-guided liver tumor ablation/injection

Several EUS-guided liver tumor ablation/injection techniques have been described in the literature.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an alternative low-risk minimally invasive therapy for HCC and liver metastases when resection cannot be performed or, in case of HCC, when transplantation cannot be executed 137 . EUS-guided RFA with a prototype retractable umbrella-shaped electrode array has been created for effective coagulation necrosis of large areas, minimizing the risk of gastric mucosa damage 138 . More recently, a monopolar RFA under EUS guidance using a 1-Fr wire electrode (Habib) was introduced and tested in pig models 139 140 . Its flexible and thinner electrode could facilitate tissue access. Although one study did not show definite coagulative necrosis in the liver 139 , another study did show positive results 140 . Further studies are needed to fully examine the response of tumor tissues to EUS-RFA.

Cryothermy (Cool-Tipped RFA) is a new flexible ablation device with a hybrid cryotherm probe that combines bipolar RFA with cryotechnology allowing for more efficient tissue ablation in the setting of lower temperatures provided by the cooling cryogenic gas 141 . In a single study, EUS-guided transgastric cryotherm ablation in porcine liver resulted in well-defined ablation areas without any complications 142 .

Neodymium:yttium-aluminum-garnet (Nd-YAG) laser ablation is a minimally invasive method for solid tumor destruction by directing low-power laser light energy into tissue. Its advantages are use of thinner needles, shorter application time and the ability to reuse and re-sharpe the needle, which can be used at different angles. Di Matteo et al. 143 reported the first human case of EUS-guided Nd:YAG laser ablation for treatment of HCC located in the caudate lobe, with favorable prognosis. More recently, a prospective study including 10 patients with HCC or liver metastasis from colorectal carcinoma concluded that EUS-guided laser ablation might be technically feasible in selected tumors of the caudate lobe and left liver 144 . Nonetheless, the safety of this modality must be further confirmed in future studies.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) was first developed as a thermal ablation method to ablate prostatic tissue and later to ablate liver metastases surgically or via a transcutaneous approach. Recently, a EUS-HIFU device has been created with the aim of treating tumors localized near the gastric lumen without the difficulties of gas interposition. Two reports, performed in living pig models, achieved complete necrosis of the lesions and had no immediate AEs 145 146 .

EUS-guided fine-needle ethanol injection was developed to deliver therapeutic agents to a target site more precisely and minimize damage to non-tumor tissue compared to the percutaneous approach. The efficacy and safety seen in the case reports and case series of EUS-guided ethanol injection in HCC 147 148 149 150 and hepatic metastasis 151 152 suggest a promising role for EUS in managing lesions that are difficult to access with conventional methods. After EUS-guided ethanol liver tumor injection, a self-limited subcapsular hematoma 152 was reported.

EUS-guided iodine-125 brachytherapy is another palliative treatment. Although usually performed percutaneously, EUS-guided iodine-125 brachytherapy can be a safe and effective alternative for left-sided liver tumors refractory to transabdominal interventions 150 .

EUS-guided portal injection chemotherapy (EPIC) using irinotecan-loaded microbeads in liver metastases can increase intrahepatic irinotecan concentrations while decreasing systemic exposure 153 .

EUS-guided fiducial placement for stereotactic body radiation therapy

Use of EUS-guided fiducial placement for stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is becoming more widespread. Using multiple photon beams that intersect at a stereotactically determined target, it delivers higher doses of radiation into the tumor while sparing surrounding normal tissue. As the liver is very radiosensitive, accurate targeting of the tumor while salvaging normal hepatic parenchyma is crucial to prevent radiation-induced liver injury. SBRT requires implantation of fiducial markers in the lesion for adequate detection. EUS-guided fiducial placement seems to be a safe and technically feasible technique for preparing patients with deeper liver malignancies for SBRT that are not feasible for percutaneous approaches 154 155 .

EUS-guided selective portal vein embolization

Preoperative embolization of PV branches causing atrophy of the hepatic segments to be removed and subsequent compensatory hypertrophy of the remaining segments has proven to be safe and effective in patients undergoing extensive hepatectomy 156 157 . Matthes et al. 158 reported the first successful EUS-guided selective PV embolization with Enteryx (ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer) in a single swine model.

EUS-guided cyst ablation

Most simple liver cysts require no treatment. However, when they become symptomatic, treatment is indicated. Surgery is the classical approach, but as it leads to considerable morbidity rates, other less-invasive modalities were developed. Percutaneous aspiration (US or CT-guided) with lavage therapy with a sclerosing agent has demonstrated encouraging results with minimal AEs. More recently, EUS-guided aspiration and lavage therapy with alcohol has been postulated as having the advantage of not requiring insertion of a percutaneous drainage catheter, thus enabling alcohol lavage to be done with a one-step approach and has been considered a preferred approach to left lobe cysts 159 . There is a newer sclerosing agent used in EUS-FNA (1 % lauromacrogol) that seems to have fewer side effects than traditional ethanol and can thus be used as a replacement 160 .

EUS-guided liver abscess drainage

Percutaneous drainage (PCD) is a first-line method for liver abscess drainage because of its minimal invasiveness and high technical success rate 161 162 . However, it has several disadvantages, such as external-drainage and self-tube removal that may lead to patient discomfort. Recently, EUS-guided liver abscess drainage (EUS-AD) has been developed with the advantages of doing one-step internal drainage (which has an obvious cosmetic benefit and avoids risk of self-tube removal and peritonitis). Nonetheless, only a few cases have been reported 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 . Even fewer reports can be found on EUS-AD using fully-covered self-expandable metallic stents (fcSEMS) 168 169 170 171 172 174 . SEMS are expandable and have a larger diameter compared to plastic stents, resulting in impaction between the stent and the surrounding drainage area or abscess wall, and thus potentially less leakage into the abdominal cavity. In addition, the larger diameter allows for a better drainage effect, obviating the need for multiple sessions to clean the abscess and a lesser procedure time. If, however, a direct endoscopic necrosectomy is indicated, it can be easily performed through the large-bore stent. Finally, SEMS can also be helpful in hemostasis when unexpected bleeding from the tract occurs during the procedure. Ogura et al. 172 concluded that EUS-AD with fcSEMS is a potential first-line treatment for liver abscesses, particularly in the left liver lobe, as it is associated with shorter hospital stay, higher clinical success and lower AE rates compared to PCD. So far, only one case report has described a successful EUS-AD of the right hepatic lobe with SEMS 175 .

Infected hepatic cysts are much rarer and only a single case has reported an effective EUS-guided drainage 176 . Rare infected intracystic papillary hepatic adenocarcinomas have also been successfully approached by EUS 177 .

EUS-guided therapy for portal hypertension

Apart from improving the diagnosis, EUS can also assist in the management of PHT.

Nagamine et al. 178 conducted a successful pilot study of a “modified” esophageal variceal ligation (EVL) technique using an EUS-color Doppler with the aim of decreasing variceal recurrence rate associated with traditional EVL. As it has been shown that persistence of patent varices, perforating veins or peri-ECV are associated with variceal recurrence, EVL performed with EUS can be advantageous compared to upper endoscopy as it can better identify these zones and assist in completing variceal eradication.

Esophageal varices can also be eradicated using EUS-guided sclerotherapy, as concluded in a randomized controlled study by Paulo et al. 179 . This procedure seems to reduce recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic therapy 180 and the azygus vein diameter 181 . Minor complications in EUS-sclerotherapy (as thoracic pain and self-limited bleeding) have been reported and do not seem to differ from the endoscopically induced complications 179 .

For eradication of gastric varices, EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection with/without coiling with precise injection in the collaterals veins can be valuable, both for obtaining hemostasis during active bleeding and in primary and secondary bleeding prophylaxis 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 ( Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

EUS-guided cyanoacrylate in varices. a EUS-doppler evaluation of varices. b EUS-puncture of the varix. c EUS-guided cyanoacrylate. d Varix total obliteration with the cyanoacrylate.

EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection with/without coiling has been also used for duodenal varices 86 87 192 . EUS can further be useful for evaluating adequacy of tissue adhesive in variceal obturation 193 . EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection has been associated with fever, chest pain, post-injection ulcers, and asymptomatic pulmonary glue embolisms 182 . These AEs, however, seem to be fewer than with endoscopy-guided injection 186 .

EUS-guided coiling is another option for embolization of gastric varices 194 . It requires fewer procedures and has fewer AEs than EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection although larger comparative studies are needed 182 . One coil migration into the liver was described, but passed spontaneously retrograde into the portal vein and assumed a final position in the subcapsular liver without clinical sequelae 195 and few cases of self-limited bleeding have occurred at the puncture site during the procedure 196 . AEs associated with EUS-guided coil application tend to be fewer than with EUS-guided cyanoacrylate injection 182 . Combining cyanoacrylate injection and coil embolization showed favorable results in large studies 183 197 . Combining both carries a 7 % AE rate (self-limited abdominal pain, pulmonary embolization, and bleeding) 187 . Good short-term outcomes after microcoil injection in anastomotic varices after total pancreatectomy have also been reported 196 .

A case report of small bowel variceal bleeding demonstrated successful management using an EUS-assisted human thrombin injection 198 .

Finally, traditional transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS), an effective treatment for PHT complications, can be technically challenging when performed in the setting of IVC and HV obstruction. In addition, catheter manipulation through the right atrium and intrathoracic IVC may be dangerous in patients with severe cardiopulmonary disease. EUS-guided IPSS creation 103 199 200 201 was thus introduced as a potentially advantageous alternative as it does not require entrance into the heart or the IVC and decreases radiation exposure to both patient and physician during stent deployment. Also, it could become a valid therapeutic option in patients with active variceal bleeding that does not respond to endoscopic hemostasis and who are not stable enough to sustain transport to a radiology suite or when there is an anticipated delay before conventional TIPSS placement.

Limitations of EUS

The potential drawback of EUS when used for diagnostic purposes might be that it is invasive and expensive to perform. In addition, as already described, diagnostic accuracy is limited for lesions located in the right liver lobe or under the dome of the diaphragm. Presence of fatty infiltration, calcifications, pneumobilia, and extensive fibrosis may also interfere with ultrasound images. Altered anatomy (for example, presence of a pharyngeal diverticulum or a tight stricture), as is an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, may also restrict EUS performance. Some of the EUS tools discussed here may also be unavailable. The endosonographer’s experience and diligence by which the liver is scrutinized are of critical diagnostic and therapeutic importance.

Patients included in the studies either had no cirrhosis or a compensated cirrhosis. To fully evaluate use of EUS interventions, it would be very interesting to incorporate patients with decompensated cirrhosis in the study population, as they are susceptible to higher rates of complications such as bleeding/infection.

A clear limitation of the current literature of EUS related to liver diseases is that the majority of the studies have been small, single-center, often retrospective and non-randomized. Experience with EUS interventional procedures in the liver remains limited mainly to animal feasibility studies and small human case series.

Therefore, although promising, much work needs to be done to firmly and scientifically establish the indication of diagnostic and therapeutic EUS in liver disease, including resolving issues pertaining its cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion

EUS has potentially significant clinical applications in diagnosis and treatment of liver disorders. It provides excellent, unobstructed, real-time imaging of the liver at high resolution. Adjunct tools such as Doppler, elastography, and contrast can be used to improve its diagnostic yield. EUS-guided interventional procedures to measure portal hepatic pressure, ablate hepatic tumors and cysts, and drain liver abscesses have great potential to be patient friendly, cost-effective treatment alternatives with limited risk of complications. It should also be recognized that EUS is limited in regard to right lobe access. All this potential calls for adequately designed, preferably randomized controlled studies to substantiate the promise of the technology and firmly establish the role of EUS in diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms for liver disorders.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Couinaud C. [Liver lobes and segments: notes on the anatomical architecture and surgery of the liver ] Presse Med. 1954;62:709–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatia V, Hijioka S, Hara K et al. Endoscopic ultrasound description of liver segmentation and anatomy: Endoscopic ultrasound anatomy of liver. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:482–490. doi: 10.1111/den.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andanappa H K, Dai Q, Korimilli A et al. Acoustic liver biopsy using endoscopic ultrasound. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1078–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Mukhopadhyay P, Bhatt B et al. Endoscopic ultrasound versus CT scan for detection of the metastases to the liver: results of a prospective comparative study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:367–373. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318167b8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caletti G, Brocchi E, Baraldini M et al. Assessment of portal hypertension by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S21–S27. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seicean A. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of upper digestive bleeding: a useful tool. J Gastrointest Liver Dis JGLD. 2013;22:465–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiechowska-Kozłowska A, Zasada K, Milkiewicz M et al. Correlation between endosonographic and doppler ultrasound features of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2012/395345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiechowska-Kozlowska A, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Wasilewicz M P et al. Upper gastrointestinal endosonography in patients evaluated for liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3082–3084. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh J-S, Wang W-M, Perng D-S et al. Modified devascularization surgery for isolated gastric varices assessed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:666–671. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiano T D, Adrain A L, Cassidy M J et al. Use of high-resolution endoluminal sonography to measure the radius and wall thickness of esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:425–428. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson B C. Pressed for an answer: has elastography finally come to EUS? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:301–303. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claudon M, Dietrich C, Choi B et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver – update 2012. Ultraschall Med - Eur J Ultrasound. 2012;34:11–29. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollerbach S, Reiser M, Topalidis T et al. Diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (hcc) in a high-risk patient by using transgastric EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy (EUS-FNA) Z Für Gastroenterol. 2003;41:995–998. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhary N, Bansal R, Puri R et al. Impact and safety of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration on patients with cirrhosis and pyrexia of unknown origin in India. Endosc Int Open. 2016;04:E953–E956. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-112585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumonceau J-M, Deprez P, Jenssen C et al. Indications, results, and clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline – Updated January 2017. Endoscopy. 2017;49:695–714. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-109021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pineda J J, Diehl D L, Miao C L et al. EUS-guided liver biopsy provides diagnostic samples comparable with those via the percutaneous or transjugular route. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee W J, Uradomo L T, Zhang Y et al. Comparison of the Diagnostic yield of EUS needles for liver biopsy: ex vivo study. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2017;2017:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2017/1497831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prasad P, Schmulewitz N, Patel A et al. Detection of occult liver metastases during EUS for staging of malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath K, Brody D, Luketich J et al. Detection of unsuspected left hepatic lobe metastases during EUS staging of cancer of the esophagus and cardia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1742–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awad S S, Fagan S, Abudayyeh Set al. Preoperative evaluation of hepatic lesions for the staging of hepatocellular and metastatic liver carcinoma using endoscopic ultrasonography Am J Surg 2002184601–604.; discussion 604-605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh P, Erickson R A, Mukhopadhyay P et al. EUS for detection of the hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen P, Feng J C, Chang K J. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of liver lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:357–361. doi: 10.1053/ge.1999.v50.97208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii-Lau L L, Abu Dayyeh B K, Bruno M J et al. EUS-derived criteria for distinguishing benign from malignant metastatic solid hepatic masses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1188–1.196E10. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadan R, Irena H, Milorad O et al. EUS elastography in the diagnosis of focal liver lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:823–824. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandulescu L, Padureanu V, Dumitrescu C et al. A pilot study of real time elastography in the differentiation of focal liver lesions. Curr Health Sci J. 2012;38:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Onofrio M, Crosara S, De Robertis R et al. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of Focal Liver Lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W56–W66. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minaga K, Takenaka M, Kitano M et al. 115 Improved diagnosis of liver metastases using kupffer-phase image of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:AB53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H-X. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound: The evolving applications. World J Radiol. 2009;1:15. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v1.i1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu M, Lin M, Lu M et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography in evaluating the treatment response to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma using modified RECIST. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:2502–2511. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakaji S, Hirata N. Evaluation of the viability of hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography after transarterial chemoembolization. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:390. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWitt J. Endoscopic ultrasound–guided fine needle aspiration cytology of solid liver lesions: a large single-center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1976–1981. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowe D R, Eloubeidi M A, Chhieng D C et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of hepatic lesions: Computerized tomographic-guided versus endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA. Cancer. 2006;108:180–185. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollerbach S, Willert J, Topalidis T et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of liver lesions: histological and cytological assessment. Endoscopy. 2003;35:743–749. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anand D, Barroeta J E, Gupta P K et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of non-pancreatic lesions: an institutional experience. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1254–1262. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.045955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowe A, Knight C S, Jhala D et al. Diagnosis of metastatic fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma by endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration. CytoJournal [Internet] 2011;8:2. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.76495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Sakamoto N. Hepatobiliary alveolar echinococcosis infiltration of the hepatic hilum diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:339–340. doi: 10.1111/den.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee Y N, Moon J H, Kim H K et al. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling using core biopsy needle as a percutaneous biopsy rescue for diagnosis of solid liver mass: Combined histological-cytological analysis: EUS-guided biopsy for solid liver mass. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1161–1166. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes M CD, Huang X, Bain A et al. Primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma with metastasis to the liver diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and fine needle biopsy: A case report and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:1070–1073. doi: 10.1002/dc.23540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng H Q, Darwin P, Papadimitriou J C et al. Liver metastases of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with marked nuclear atypia and pleomorphism diagnosed by EUS FNA cytology: a case report with emphasis on FNA cytological findings. CytoJournal. 2006;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulman A R, Thompson C C, Odze R et al. Optimizing EUS-guided liver biopsy sampling: comprehensive assessment of needle types and tissue acquisition techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopes C, de Garcia R, Santos G et al. Gastric compression due to a cystic liver metastasis of vulvar carcinoma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E208–E209. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang D, Zhu H, DiMaio C J. Abdominal Splenosis mimicking a liver mass: diagnosis by EUS-FNA. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e16–e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Husney J, Guttmann S, Anyadike N et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration: A novel way to diagnose a solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the liver. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:134. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.180481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh D, Seo D-W, Hong S-M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration can target right liver mass. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:109. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.204813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.tenBerge J, Hoffman B J, Hawes R H et al. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of the liver: Indications, yield, and safety based on an international survey of 167 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:859–862. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prachayakul V, Aswakul P, Kachintorn U. EUS guided fine needle aspiration cytology of liver nodules suspicious for malignancy: yields, complications and impact on management. J Med Assoc Thail Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 2012;95:S56–S60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bogstad J, Vilmann P, Burcharth F. Early detection of recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma by endosonographically guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:322–324. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goel R K, Jha B, Mohapatra I et al. A liver mass in a case of gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the stomach is not always a metastasis. Cytopathology. 2016;27:74–76. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi H J, Moon J H, Kim H K et al. KRAS mutation analysis by next-generation sequencing in endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling for solid liver masses: KRAS mutation analysis in EUS sampling . J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:154–162. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki R, Shin D, Richards-Kortum R et al. In vivo cytological observation of liver and spleen by using high-resolution microendoscopy system under endoscopic ultrasound guidance: A preliminary study using a swine model. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:239. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.187867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kayar Y, Turkdogan K A, Baysal B et al. EUS-guided FNA of a portal vein thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21:86. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.21.86.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai R, Stephens V, Bardales R. Diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma by EUS-FNA of a portal vein thrombus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:574–577. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Storch I, Gomez C, Contreras F et al. hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with portal vein invasion, masquerading as pancreatic mass, diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:789–791. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moreno M, Gimeno-García A, Corriente M et al. EUS-FNA of a portal vein thrombosis in a patient with a hidden hepatocellular carcinoma: confirmation technique after contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E590–E591. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michael H, Lenza C, Gupta M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound -guided fine-needle aspiration of a portal vein thrombus to aid in the diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7:124–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.European Association For The Study Of The Liver ; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer . EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delconte G, Bhoori S, Milione M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of splenic vein thrombosis: a novel approach to the portal venous system. Endoscopy. 2016;48:E40–E41. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-100199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang K-X, Ben Q-W, Jin Z-D et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hara K, Bhatia V, Hijioka S et al. A convex EUS is useful to diagnose vascular invasion of cancer, especially hepatic hilus cancer: a convex EUS is useful to diagnose. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:26–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2011.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: Non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rimbaş M, Gheonea D I, Săndulescu L et al. EUS elastography in evaluating chronic liver disease. Why not from Inside? Curr Health Sci J. 2009;35:225–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diehl D, Johal A, Khara H et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy: a multicenter experience. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E210–E215. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stavropoulos S N, Im G Y, Jlayer Z et al. High yield of same-session EUS-guided liver biopsy by 19-gauge FNA needle in patients undergoing EUS to exclude biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lutz H, Wasmuth H, Streetz K et al. Endoscopic ultrasound as an early diagnostic tool for primary sclerosing cholangitis: a prospective pilot study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:934–939. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeWitt J, McGreevy K, Cummings O et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided Tru-cut biopsy of benign liver disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mathew A. EUS-guided routine liver biopsy in selected patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2354–2355. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01353_7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gleeson F C, Clayton A C, Zhang L et al. Adequacy of endoscopic ultrasound core needle biopsy specimen of nonmalignant hepatic parenchymal disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1437–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakai Y, Samarasena J, Iwashita T et al. Autoimmune hepatitis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy using a new 19-gauge histology needle. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E67–E68. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gor N, Salem S B, Jakate S et al. Histological adequacy of EUS-guided liver biopsy when using a 19-gauge non–Tru-Cut FNA needle. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sey M SL, Al-Haddad M, Imperiale T F et al. EUS-guided liver biopsy for parenchymal disease: a comparison of diagnostic yield between two core biopsy needles. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johal A, Khara H, Maksimak M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy in pediatric patients. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:191. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.138794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saab S, Phan J, Jimenez M A et al. Endoscopic ultrasound liver biopsies accurately predict the presence of fibrosis in patients with fatty liver. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1477–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shah N D, Sasatomi E, Baron T H. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided parenchymal liver biopsy: single center experience of a new dedicated core needle. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:784–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nieto J, Khaleel H, Challita Y et al. EUS-guided fine-needle core liver biopsy sampling using a novel 19-gauge needle with modified 1-pass, 1 actuation wet suction technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shahshahan M, Gertz H, Fakhreddine A Y et al. Mo1285 endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy versus percutaneous and trans-jugular liver biopsy for evaluation of liver parenchyma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:AB490. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hassan G, Sahai A, Paquin S. Near-fatal hemorrhagic shock after endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy. Endoscopy. 2015;47:E378–E388. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choudhuri G, Dhiman R K, Agarwal D K. Endosonographic evaluation of the venous anatomy around the gastro-esophageal junction in patients with portal hypertension. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1250–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee Y T, Chan F KL, Ching J YL et al. Diagnosis of Gastroesophageal Varices and Portal Collateral Venous Abnormalities by Endosonography in Cirrhotic Patients. Endoscopy. 2002;34:391–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-25286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McKiernan P J, Sharif K, Gupte G L. The role of endoscopic ultrasound for evaluating portal hypertension in children being assessed for intestinal transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;86:1470–1473. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181891d63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Konishi Y, Nakamura T, Kida H et al. Catheter US probe EUS evaluation of gastric cardia and perigastric vascular structures to predict esophageal variceal recurrence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:197–203. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miller L S, Schiano T D, Adrain A et al. Comparison of high-resolution endoluminal sonography to video endoscopy in the detection and evaluation of esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1996;24:552–555. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burtin P, Calès P, Oberti F et al. Endoscopic ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lo G H, Lai K H, Cheng J S et al. Prevalence of paraesophageal varices and gastric varices in patients achieving variceal obliteration by banding ligation and by injection sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:428–436. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pontes J M, Leitão M C, Portela F A et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the treatment of oesophageal varices by endoscopic sclerotherapy and band ligation: do we need it? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sgouros S N, Bergele C, Avgerinos A. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of portal hypertension. Where are we next? Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Curcio G. Case of obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding after pediatric liver transplantation explained by endoscopic ultrasound. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:571. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i12.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rana S, Bhasin D, Chaudhary V et al. Clinical, endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound features of duodenal varices: A report of 10 cases. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:54. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.121243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sample Organization . Rana S S. Communication of duodenal varix with pericholedochal venous plexus demonstrated by endoscopic ultrasound in a patient of portal biliopathy. Endosopic Ultrasound. 2012;1:165. doi: 10.7178/eus.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rana S S, Bhasin D K, Singh K. Duodenal varix diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:A24. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sharma M, Mohan P, Rameshbabu C S et al. Identification of perforators in patients with duodenal varices by endoscopic ultrasound—a case series [with video] J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu J B, Miller L S, Feld R I et al. Gastric and esophageal varices: 20-MHz transnasal endoluminal US. Radiology. 1993;187:363–366. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.2.8475273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nishizono M, Haraguchi Y, Eto T et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography using a 15/20 MHz probe in a direct contact technique: evaluation and application in esophageal and gastric varices. Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi Hukuoka Acta Medica. 1994;85:251–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Suzuki T, Matsutani S, Umebara K et al. EUS changes predictive for recurrence of esophageal varices in patients treated by combined endoscopic ligation and sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:611–617. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.109801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nakamura H, Endo M, Shimojuu Ket al. Esophageal varices evaluated by endoscopic ultrasonography: observation of collateral circulation during non-shunting operations Surg Endosc 1990469–74.; discussion 75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Caletti G C, Brocchi E, Ferrari A et al. Value of endoscopic ultrasonography in the management of portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 1992;24:342–346. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Avunduk C, Hampf F. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:104–106. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parente F, Petrillo M, Vago L et al. The watermelon stomach: clinical, endoscopic, endosonographic, and therapeutic aspects in three cases. Endoscopy. 1995;27:203–206. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen T K, Wu C H, Lee C L et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of giant gastric folds. J Formos Med Assoc Taiwan Yi Zhi. 1999;98:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wong R CK, Farooq F T, Chak A. Endoscopic Doppler US probe for the diagnosis of gastric varices (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Giday S A, Clarke J O, Buscaglia J M et al. EUS-guided portal vein catheterization: a promising novel approach for portal angiography and portal vein pressure measurements. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lai L, Poneros J, Santilli J et al. EUS-guided portal vein catheterization and pressure measurement in an animal model: a pilot study of feasibility. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:280–283. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Giday S A, Ko C-W, Clarke J O et al. EUS-guided portal vein carbon dioxide angiography: a pilot study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:814–819. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schulman A R, Thompson C C, Ryou M. EUS-guided portal pressure measurement using a digital pressure wire with real-time remote display: a novel, minimally invasive technique for direct measurement in an animal model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:817–820. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schulman A R, Thompson C C, Ryou M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided direct portal pressure measurement using a digital pressure wire with real-time remote display: a survival study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:1051–1054. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Magno P, Ko C-W, Buscaglia J M et al. EUS-guided angiography: a novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the vascular system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:587–591. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fujii-Lau L, Leise M, Kamath P et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided portal-systemic pressure gradient measurement. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E654–E656. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huang J Y, Samarasena J B, Tsujino T et al. EUS-guided portal pressure gradient measurement with a simple novel device: a human pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:996–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jackson F W, Adrain A L, Black M et al. Calculation of esophageal variceal wall tension by direct sonographic and manometric measurements. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miller E S, Kim J K, Gandehok J et al. A new device for measuring esophageal variceal pressure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:284–291. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Miller L S, Dai Q, Thomas A et al. A new ultrasound-guided esophageal variceal pressure-measuring device. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1267–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pontes J M, Leitão M C, Portela F et al. Endosonographic Doppler-guided manometry of esophageal varices: experimental validation and clinical feasibility. Endoscopy. 2002;34:966–972. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schiano T D, Adrain A L, Vega K J et al. High-resolution endoluminal sonography assessment of the hematocystic spots of esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:424–427. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Miller L, Banson F L, Bazir K et al. Risk of esophageal variceal bleeding based on endoscopic ultrasound evaluation of the sum of esophageal variceal cross-sectional surface area. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:454–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J et al. Observation of Gastric Variceal Flow characteristics by endoscopic ultrasonography using color Doppler. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:575–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Irisawa A, Saito A, Obara K et al. Endoscopic recurrence of esophageal varices is associated with the specific EUS abnormalities: Severe periesophageal collateral veins and large perforating veins. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:77–84. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.108479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Faigel D O, Rosen H R, Sasaki A et al. EUS in cirrhotic patients with and without prior variceal hemorrhage in comparison with noncirrhotic control subjects. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:455–462. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.107297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Irisawa A, Obara K, Sato Y et al. EUS analysis of collateral veins inside and outside the esophageal wall in portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:374–380. doi: 10.1053/ge.1999.v50.97777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Men C, Zhang G. Endoscopic ultrasonography predicts early esophageal variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6749. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kume K, Yamasaki M, Watanabe T et al. Mild collateral varices and a fundic plexus without perforating veins on EUS predict endoscopic non-recurrence of esophageal varices after EVL. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Masalaite L, Valantinas J, Stanaitis J. The role of collateral veins detected by endosonography in predicting the recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic treatment: a systematic review. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:339–351. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Seno H, Konishi Y, Wada M et al. Improvement of collateral vessels in the vicinity of gastric cardia after endoscopic variceal ligation therapy for esophageal varices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2004;2:400–404. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J et al. Perforating veins in recurrent esophageal varices evaluated by endoscopic color Doppler ultrasonography with a galactose-based contrast agent. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:422–428. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1314-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J et al. Endoscopic ultrasonographic evaluation of hemodynamics related to variceal relapse in esophageal variceal patients. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:126–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Masalaite L, Valantinas J, Stanaitis J. Endoscopic ultrasound findings predict the recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic band ligation: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1322–1330. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1043640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Leung V K, Sung J J, Ahuja A T et al. Large paraesophageal varices on endosonography predict recurrence of esophageal varices and rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1811–1816. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Irisawa A, Obara K, Bhutani M S et al. Role of para-esophageal collateral veins in patients with portal hypertension based on the results of endoscopic ultrasonography and liver scintigraphy analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:309–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Carneiro F OAA, Retes F A, Matuguma S E et al. Role of EUS evaluation after endoscopic eradication of esophageal varices with band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Dhiman R K, Choudhuri G, Saraswat V A et al. Role of paraoesophageal collaterals and perforating veins on outcome of endoscopic sclerotherapy for oesophageal varices: an endosonographic study. Gut. 1996;38:759–764. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Elsamman M K, Fujiwara Y, Kameda N et al. Predictive factors of worsening of esophageal varices after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration in patients with gastric varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2214–2221. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kuramochi A, Imazu H, Kakutani H et al. Color Doppler endoscopic ultrasonography in identifying groups at a high-risk of recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1992-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hino S, Kakutani H, Ikeda K et al. Hemodynamic analysis of esophageal varices using color Doppler endoscopic ultrasonography to predict recurrence after endoscopic treatment. Endoscopy. 2001;33:869–872. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liao W-C, Chen P-H, Hou M-C et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography assessment of para-esophageal varices predicts efficacy of propranolol in preventing recurrence of esophageal varices. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:342–349. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0970-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Escorsell A, Bordas J M, Feu F et al. Endoscopic assessment of variceal volume and wall tension in cirrhotic patients: effects of pharmacological therapy. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1640–1646. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lee Y T, Sung J J, Yung M Y et al. Use of color Doppler EUS in assessing azygos blood flow for patients with portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Nishida H, Giostra E, Spahr L et al. Validation of color Doppler EUS for azygos blood flow measurement in patients with cirrhosis: Application to the acute hemodynamic effects of somatostatin, octreotide, or placebo. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:24–30. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hansen E F, Bendtsen F, Brinc K. Endoscopic Doppler ultrasound for measurement of azygos blood flow: validation against thermodilution and assessment of pharmacological effects of terlipressin in portal hypertension. scand j gastroenterol. 2001;36:318–325. doi: 10.1080/003655201750074717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.McDermott S, Gervais D. Radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors. Semin Interv Radiol. 2013;30:49–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Varadarajulu S, Jhala N C, Drelichman E R. EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation with a prototype electrode array system in an animal model (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yoon W J, Daglilar E S, Kamionek M et al. Evaluation of radiofrequency ablation using a 1-Fr wire electrode in porcine pancreas, liver, gallbladder, spleen, kidney, stomach, and lymph nodes: A pilot study: RFA of abdominal organs. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:465–468. doi: 10.1111/den.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rustagi T, Gleeson F C, Abu Dayyeh B K et al. Evaluation of Effects of Radiofrequency Ablation of Ex vivo Liver Using the 1-Fr Wire Electrode. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:168–171. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Hines-Peralta A, Hollander C Y, Solazzo S et al. Hybrid radiofrequency and cryoablation device: preliminary results in an animal model. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1111–1120. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000136031.91939.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Carrara S, Arcidiacono P, Albarello L et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided application of a new internally gas-cooled radiofrequency ablation probe in the liver and spleen of an animal model: a preliminary study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:759–763. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Di Matteo F, Grasso R, Pacella C M et al. EUS-guided Nd:YAG laser ablation of a hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate lobe. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jiang T, Tian G, Bao H et al. EUS dating with laser ablation against the caudate lobe or left liver tumors: a win-win proposition? Cancer Biol Ther. 2018;19:145–152. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2017.1414760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pioche M, Lafon C, Constanciel E et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound liver destruction through the gastric wall under endoscopic ultrasound control: first experience in living pigs. Endoscopy. 2012;44:E376–E377. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Li T, Khokhlova T, Maloney E et al. Endoscopic high-intensity focused US: technical aspects and studies in an in vivo porcine model (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1243–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]