Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between operator or hospital volume and procedural outcomes of carotid revascularization.

Background

Operator and hospital volume have been proposed as determinants of outcome following carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS). The magnitude and clinical relevance of this relationship is debated.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed and EMBASE until August 21, 2017. The primary outcome was procedural (30-days, in-hospital or perioperative) death or stroke. Obtained or estimated risk estimates were pooled with a generic inverse variance random-effects model.

Results

We included 87 studies. A decreased risk of death or stroke following CEA was found for high operator volume with a pooled adjusted OR of 0.50 (95%CI 0.28-0.87; 3 cohorts), and a pooled unadjusted RR of 0.59 (95%CI 0.42-0.83; 9 cohorts); for high hospital volume with a pooled adjusted OR of 0.62 (95%CI 0.42-0.90; 5 cohorts), and a pooled unadjusted RR of 0.68 (95%CI 0.51-0.92; 9 cohorts). A decreased risk of death or stroke following CAS was found for high operator volume with an adjusted OR of 0.43 (95%CI 0.20-0.95; 1 cohort), and an unadjusted RR of 0.50 (95%CI 0.32-0.79; 1 cohort); for high hospital volume with an adjusted OR of 0.46 (95%CI 0.26-0.80; 1 cohort), and no significant decreased risk in a pooled unadjusted RR of 0.72 (95%CI 0.49-1.06; 2 cohorts).

Conclusions

We found a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke following CEA and CAS in high operator and high hospital volume, indicating that aiming for a high volume might help to reduce procedural complications.

Registration

This systematic review has been registered in the international prospective registry of systematic reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42017051491.

Keywords: carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting, hospital volume, operator volume, carotid revascularization, quality of care, atherosclerosis, carotid stenosis

Introduction

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS) are the mainstay surgical procedure as prophylaxis for future (recurrent) stroke, and hundreds of thousands of both procedures are performed worldwide each year. A low procedural mortality and stroke rate are necessary to guarantee net clinical benefit of intervention.1 Hemodynamic disturbance and procedural thromboembolism have been identified as important underlying mechanisms of stroke after both CEA and CAS although the mechanisms differ between the two treatment modalities.2–5 Procedural factors associated with adverse events are timing of surgery after presenting symptom,6 patch-use during CEA,7 and possibly the use of embolic protection devices during CAS.8 General versus local anesthesia9 and shunt use during CEA10 do not seem to influence the rate of adverse events.

Volume is sometimes used as a surrogate measurement of quality of care.11 As a consequence, the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST)12,13, the Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S)14, the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE)15, and the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) used volume thresholds for their credentialing process.16 The reported associations between operator or hospital volume and outcomes following carotid revascularization are, however, inconsistent.17

We therefore systematically reviewed the literature on the relationship between operator or hospital volume and outcomes following carotid revascularization and meta-analyzed the published data to determine the magnitude and clinical relevance.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to a predefined protocol (Appendix 1) that has been registered prospectively in the international prospective registry for systematic reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42017051491. Our study adhered to The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines (Appendix 2).18,19

Search strategy

We used comprehensive electronic strategies (Appendix 3) to search PubMed and EMBASE from inception until August 21, 2017 for observational studies and subgroup analyses of randomized clinical trials meeting our predefined eligibility criteria. Grey literature was not included in the search strategy, because these data may not have been subject to peer-reviewed evaluation.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included based on the following eligibility criteria: 1) full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals; 2) written in: English, German, French, Spanish, or Dutch; 3) presenting original procedural outcome data about patients undergoing either CEA or CAS for asymptomatic or symptomatic carotid stenosis; 4) reporting: hospital volume, defined as the number of carotid procedures performed per hospital within a certain timeframe; or operator volume, defined as the number of carotid procedures performed per operator within a certain timeframe. Since in-trial volume can differ largely from annual volume results, we discarded in-trial volume from this review20; and 5) presenting effect estimates or providing raw data to calculate effect estimates for our predefined outcomes. Data on learning curve, defined as the effect on the outcomes of the early procedures performed by an individual operator, were not included in this systematic review.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts were independently screened for eligibility by two authors (MHFP and ECB) and full-text copies were independently assessed for final inclusion in this review. Subsequently, we cross-checked reference lists of included articles and identified reviews for further relevant studies until no further publications were found. In case of disagreement, discrepancies were resolved in consensus meetings by MHFP, ECB and GJdB.

Data extraction

Two authors (MHFP and ECB) independently extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies: 1) Methods: study design, design of data-collection, data source, setting study, number of study centers, number of operators, geographic area (country and continent) of study, study years, sample size (patients/procedures); 2) Patient characteristics: A) Baseline characteristics: sex, age, and cardiovascular risk factors (adhering to the definitions of the individual studies) B) Disease characteristics: clinical presentation (symptomatic or asymptomatic status), degree of stenosis revealed by duplex ultrasound (<70%, 70-99%, occlusion), duration of hospital stay; 3) Determinant: total number of operators; total number of hospitals, thresholds of operator and hospital categories, number of patients/procedures per category, number of events per category; 4) Outcome: definition of the outcome as used by the authors, specification of the timeframe of outcome measurement, unadjusted RRs or ORs, adjusted RRs, ORs or HRs, and the adjustment factors if applicable.

Results from studies that only reported a P – value for an association, only textually mentioned an association without providing data with which risk estimates could be calculated, or assessed operator or hospital volume as a continuous variable are provided in Appendix Table 1. These results were not used in the quantitative analysis.

Outcome measures

Primary

The primary end-point comprises procedural death or stroke, defined as within 30-days, unless stated otherwise (e.g. in-hospital). Although a composite endpoint might be difficult to interpret, because relative risks for the separate outcomes might be the opposite of each other, we expected studies commonly report the combination of these two postoperative outcomes, which are both important to patients.

Secondary

Procedural: 1) death; 2) stroke; 3) MI; 4) death, stroke or MI; 5) following CEA: cranial nerve injury, defined as any temporary palsy of a cranial nerve at the operative side without an underlying stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Risk of bias assessment

To assess the risk of bias, we developed an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for non-experimental studies with three domains: Selection, comparability, and outcome. To address the domain selection, we assessed three domains: 1) Study design: population based study, multi-centered, data-collection (prospective, retrospective); 2) Representativeness of study cohort: low risk of bias if no selection in patients was applied. High risk of bias if risk factors that influence outcome were used for selection; 3) Ascertainment of intervention: low risk of bias if ascertainment was from medical records or registry. High risk of bias if ascertainment was from administrative sources. To address the domain comparability, we assessed: Comparability of case-mix between volume categories: low risk of bias if adjustment for case-mix differences in statistical analysis; high risk of bias if significant differences in case-mix were reported or no adjustment for case-mix differences. To address the domain outcome, we assessed two domains: 1) Assessment of outcomes: low risk of bias if independent blind assessment of outcomes was performed or outcomes were assessed using record linkage. High risk of bias if self-reporting of outcomes was used; 2) Addressing incomplete data: low risk of bias if loss of outcome data for participants or participants lost to follow-up was unlikely to introduce bias (non-differential lost to follow-up and <20%); high risk of bias if outcome data missing for participants or participants lost to follow-up was likely to introduce bias (differential loss to follow-up and/or >20%).

Statistical analyses

From the included articles, we obtained or calculated the relative risks (RRs), odds ratios (ORs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) stratified per determinant. For calculation, we used the number of patients. If the absolute number of patients was not provided, we contacted authors for additional data. Otherwise, we used the absolute number of procedures instead. If the absolute number of procedures was not provided and could not be obtained, the total number of patients in the meta-analysis was reported preceded by “>”. If articles reported data on different cohorts, we meta-analyzed the cohorts as separate studies. We calculate the inversed risk estimate and 95%CI, if the highest volume group was used as reference group in the original articles. Risk estimates less than 1 indicate decreased risk of the defined outcome in high volume operators or hospitals, and risk estimates greater than 1 indicate an increased risk of the defined outcome in high volume operators or hospitals. If the 95%CI of the pooled risk estimate did not include 1 the association was considered statistically significant. Only risk estimates with a 95%CI were used for pooled analyses. Associations for which point estimates without 95%CI could be extracted or calculated can be found in Appendix Table 2-3.

We compared the outcomes for the highest available volume threshold to the lowest available volume threshold as provided in the original articles. Risk estimates were pooled using a random effects model, with study weights based on the generic inversed variance method. Risk estimates were pooled separately for: 1) CEA and CAS; 2) RRs, ORs, and HRs; 3) unadjusted and adjusted risk estimates.

Forest plots were constructed to visualize contribution of each study to a pooled estimate. To visualize the associations in studies from which only a point estimate could be extracted, we depicted these studies in the forest plots (displayed in the Appendix) without confidence intervals. Studies excluded from meta-analyses due to overlap in study population with other studies are not displayed in the forest plots.

Construction of forest plots, funnel plots, calculation of pooled estimates, and measures of heterogeneity were performed using the Metafor package for R language environment for statistical computing version 3.1.3.21

Heterogeneity

To account for heterogeneity between studies, we used a random effects model with weights per study assigned based on the generic inverse variance method. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed with the Cochran’s Q test (if P < 0.05 significant heterogeneity exists), and expressed in the I2-statistic. A prediction interval was constructed and displayed within the forest plots if ≥3 studies were included in the meta-analyses.22,23 A prediction interval implies that there is a 95% chance that a risk estimate of a subsequent study with comparable characteristics will fall within this prediction interval. Wide prediction intervals indicate more heterogeneity than narrow prediction intervals.

Publication bias

Risk of publication bias is assessed with funnel plots and asymmetry is visually assessed and tested by Egger’s regression24, with a p-value <0.05 indicating asymmetry.25 Symmetric funnel plots indicate no to low evidence for publication bias. Funnel plots were only constructed when ≥10 studies reported on a certain determinant-outcome relation, because interpretation of these plots is hampered when fewer studies are included.25

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the following sensitivity analyses for the primary endpoint: 1) Geographical region: limited to cohorts from North America; 2) Symptomatic status: limited to cohorts with adjustment for symptomatic status; 3) Adjustment for the other volume determinant: limited to cohorts with adjustment for the other volume determinant (e.g. surgeon volume-outcome relationship adjusted for hospital volume); 4) Midyear in which treatment took place (defined as median calendar year of treatment dates): limited to cohorts with midyear of treatment equal or above the median; 5) Volume threshold for low volume: limited to cohorts with low volume equal or above the median; 6) Volume threshold for high volume: limited to cohorts with high volume equal or below the median.

Results

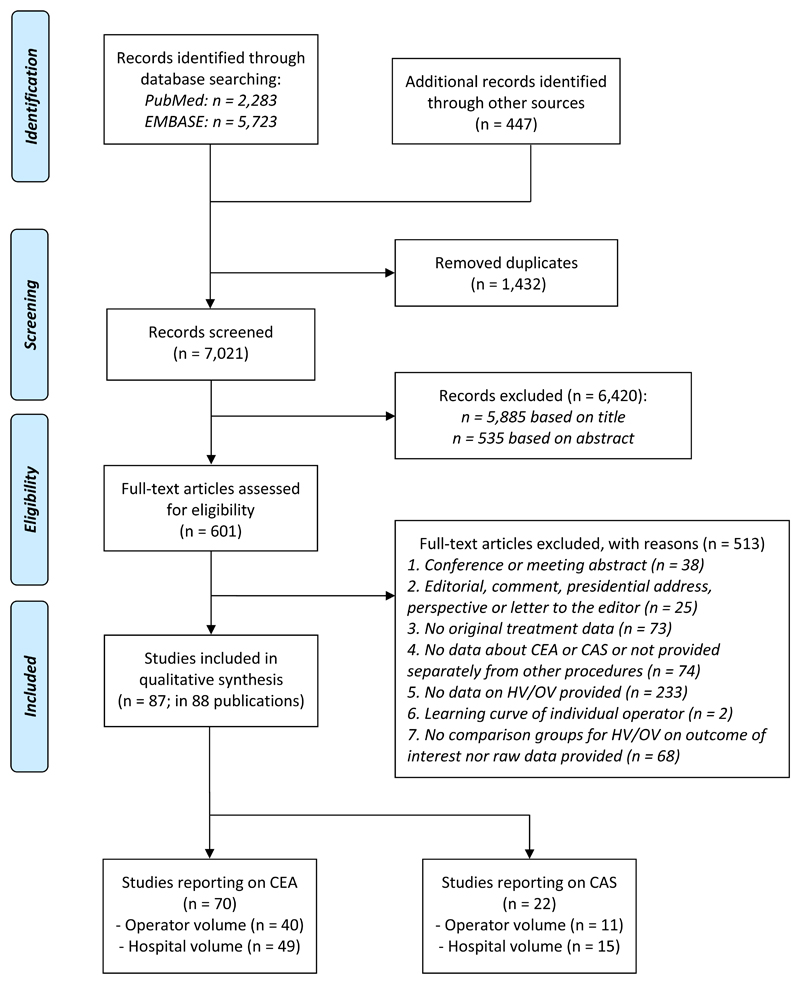

After screening 7021 publications, we identified 87 eligible studies (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 4). Two (2.3%) studies were based on data from randomized clinical trials, 85 (97.7%) studies were cohort studies, in which data-collection was prospective (15 [17.2%]), retrospective (57 [65.5%]), or a combination or unknown (15 [17.2%])(Table 1 and Appendix Table 5-6). For CEA, the relation was assessed with: 1) operator volume in 40 studies with >1,197,878 patients, and 2) hospital volume in 49 studies with >4,257,847 patients; and for CAS: 1) operator volume in 11 studies with 103,051 procedures, and 2) hospital volume in 15 studies with 178,251 procedures (Appendix Table 7). An overview of the pooled risk estimates is provided in table 2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart detailing the numbers of studies excluded and included at each step of the literature search.

Table 1. Summary of study, patient and disease characteristics of the included studies.

| Study characteristics | Totala No. of studies (%) |

CEA No. of studies (%) |

CAS No. of studies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | |||

| Cohort | 85 (97.7) | 69 (98.6) | 21 (95.5) |

| Subgroup of RCT | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (4.5) |

| Data-collection | |||

| Prospective | 15 (17.2) | 10 (14.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| Retrospective | 57 (65.5) | 47 (67.1) | 14 (63.6) |

| Combination, otder or not reported | 15 (17.2) | 13 (18.6) | 3 (13.6) |

| Data source | |||

| Clinical | 20 (23.0) | 17 (24.3) | 3 (13.6) |

| Administrative | 57 (65.5) | 46 (65.7) | 16 (72.7) |

| Combination, otder or unknown | 10 (11.5) | 7 (10) | 3 (13.6) |

| Continent | |||

| Nortd-America | 73 (83.9) | 61 (87.1) | 16 (72.7) |

| Europe | 8 (9.2) | 7 (10.0) | 2 (9.1) |

| Asia | 3 (3.4) | 0 | 3 (13.6) |

| Australia | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) | 0 |

| Transcontinental | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (4.5) |

| Number of operators in studies reporting on operator volume | |||

| ≥100 operators | 20 (39.2) | 16 (40.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| <100 operators | 16 (31.4) | 16 (40.0) | 0 |

| Unknown | 15 (29.4) | 8 (20.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| Number of hospitals in studies reporting on hospital volumea | |||

| ≥25 centers | 37 (62.7) | 30 (61.2) | 10 (66.7) |

| <25 centers | 10 (16.9) | 10 (20.4) | 0 |

| Unknown | 12 (20.3) | 9 (18.4) | 5 (33.3) |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Reported | 66 (75.9) | 51 (72.9) | 20 (90.9) |

| ≥65% male | 17 (25.8) | 12 (23.5) | 7 (35.0) |

| Age | |||

| Reported mean or median | 59 (67.8) | 42 (60.0) | 17 (77.3) |

| Mean or median ≥70 years | 29 (49.2) | 19 (45.2) | 13 (76.5) |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Symptomatic status | |||

| Reported | 54 (62.1) | 41 (58.6) | 18 (81.8) |

| ≥50% of tde cohort underwent carotid revascularization for | 24 (44.4) | 20 (48.8) | 4 (22.2) |

| symptomatic carotid stenosis | |||

| Reported degree of stenosis | |||

| Reported | 8 (9.2) | 7 (10.0) | 3 (13.6) |

| Duration of hospital stay | |||

| Reported | 22 (25.3) | 16 (22.9) | 7 (31.8) |

CAS, carotid stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Five studies reported on CEA and CAS.

Study, patient and disease characteristics per study are provided in Appendix Table 5-6.

Table 2. Pooled risk estimates per outcome for the relation between operator volume and hospital volume (high-volume vs. low-volume) and procedural outcomes following CEA and CAS.

| Operator volume | Hospital volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unadjusted RR [95%-CI] (N of cohorts) |

Adjusted OR [95%-CI] (N of cohorts) |

Unadjusted RR [95%-CI] (N of cohorts) |

Adjusted OR [95%-CI] (N of cohorts) |

|

| Procedural outcomes for CEA | ||||

| Death or stroke |

0.59 [0.42-0.83] (N = 9) |

0.50 [0.28-0.87] (N = 3) |

0.68 [0.51-0.92] (N = 9) |

0.62 [0.42-0.90] (N = 5) |

| OR: 0.40 [0.21-0.76] (N = 1) |

RR: 0.74 [0.60-0.90] (N = 1) |

|||

| Death |

0.60 [0.52-0.69] (N = 22) |

0.67 (0.61-0.74) (N = 10) |

0.71 [0.62-0.82] (N = 17) |

0.78 [0.72-0.84] (N = 12) |

| RR: 0.74 [0.53-1.02] (N = 1) |

||||

| Stroke |

0.56 [0.49-0.64] (N = 14) |

0.55 [0.41-0.75] (N = 3) |

0.83 [0.76-0.90] (N = 11) |

0.62 [0.50-0.77] (N = 3) |

| MI |

0.33 [0.20-0.53] (N = 3) |

0.55 [0.31-0.97] (N = 1) |

0.65 [0.42-0.99] (N = 4) |

1.22 [0.96-1.56] (N = 2) |

| Death, stroke, or MI | NA | 1.08 [0.64-1.82] (N = 1) |

0.70 [0.41-1.20] (N = 1) |

1.48 [0.19-11.70] (N = 2) |

| Cranial nerve injury | 0.68 [0.15-3.10] (N = 1) |

NA | 0.23 [0.04-1.39] (N = 2) |

NA |

| Procedural outcomes for CAS | ||||

| Death or stroke |

0.50 [0.32-0.79] (N = 1) |

0.43 [0.20-0.95] (N = 1) |

0.72 [0.49-1.06] (N = 2) |

0.46 [0.26-0.80] (N = 1) |

| RR: 0.43 [0.26-0.74] (N = 1) |

RR: 0.93 [0.50-1.69] (N = 1) |

|||

| Death |

0.57 [0.44-0.74] (N = 2) |

0.5 [0.4-0.7] (N = 1) |

0.70 [0.51-0.98] (N = 4) |

0.59 [0.46-0.77] (N = 2) |

| RR: 0.65 [0.28-1.52] (N = 1) |

||||

| HR: 1.36 [0.74-2.49] (N = 1) |

||||

| Stroke |

0.67 [0.50-0.90] (N = 2) |

0.67 [0.49-0.92] (N = 2) |

0.81 [0.71-0.92] (N = 4) |

0.76 [0.62-0.92] (N = 2) |

| HR: 1.04 [0.62-1.74] (N = 1) |

||||

| MI | NA | NA | 1.46 (0.19-11.00) (N = 1) |

HR: 0.38 [0.04-3.34] (N = 1) |

| Death, stroke, or MI | 0.42 [0.17-1.05] (N = 1) |

0.4 [0.15-1.07] (N = 1) |

0.94 (0.44-2.00) (N = 1) |

HR: 1.10 [0.75-1.63] (N = 1) |

CAS, carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction; N, number; NA, no cohorts available; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

All risk estimates represent the comparison of high volume with low volume taken as reference category.

Pooled estimates are calculated based on a random effects model weighting the individual cohorts with the generic inversed variance method.

Statistically significant risk estimates are displayed in a bold font. The references of the individual studies that contributed to the meta-analyses are provided in Appendix Table 10

Risk of bias assessment

Most studies were population-based or multicenter. Incomplete data on outcome did not exceed 20% except for one study. High risk of bias was assigned to studies that retrospectively used administrative databases, especially if these databases implied a selection of patients for enrolment. The use of classification coding systems for ascertainment of treatment and determination of outcome was the main reason leading to the assignment of a high risk of bias (Appendix Table 8).

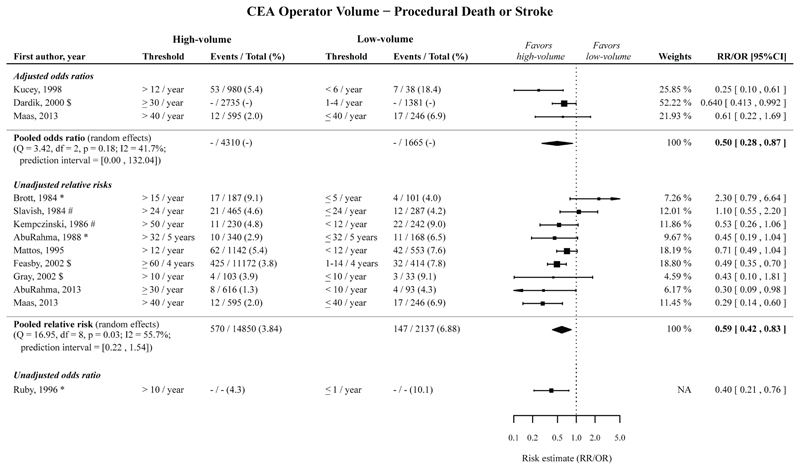

CEA operator volume

High operator volume compared to low operator volume was significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death or stroke following CEA, with a pooled adjusted OR of 0.50 (95%CI 0.28-0.87; 3 cohorts),26–28 with a pooled unadjusted RR of 0.59 (95%CI 0.42-0.83; 9 cohorts),28–36 and with an unadjusted OR of 0.40 (95%CI 0.21-0.76; 1 cohort).37 (Figure 2; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Risk estimates and meta-analysis for the association between CEA operator volume (high vs. low volume) for the outcome procedural death or stroke. Pooled estimates are based on a random effects model. Point sizes of the individual studies are proportional to the standard error of the specific study. Point estimates without confidence intervals were not included in the meta-analyses, and can be found in Appendix Figure 19.

The timeframe for the measured outcomes is depicted as follows: no symbol 30-days outcome, * perioperative, # postoperative, $ in-hospital, § not further specified. CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

The pooled adjusted ORs and pooled unadjusted RRs, with low operator volume taken as reference, showed that high operator volume is significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death and procedural stroke separately, and procedural MI following CEA (Table 2; Appendix Figure 1-3).

The adjusted association for procedural death, stroke or MI following CEA, and the unadjusted association for procedural cranial nerve injury were not statistically significant (Table 2; Appendix Figure 4-5).

Among the studies reporting unadjusted RRs for procedural death or stroke, procedural death, and procedural stroke, most prediction intervals were narrow and did not include 1 except for the outcome procedural death or stroke.

Within the meta-analyses of the adjusted ORs for these outcomes the prediction intervals were wider and including 1 (except for the outcome procedural death), possibly due to the low number of studies reporting adjusted ORs.

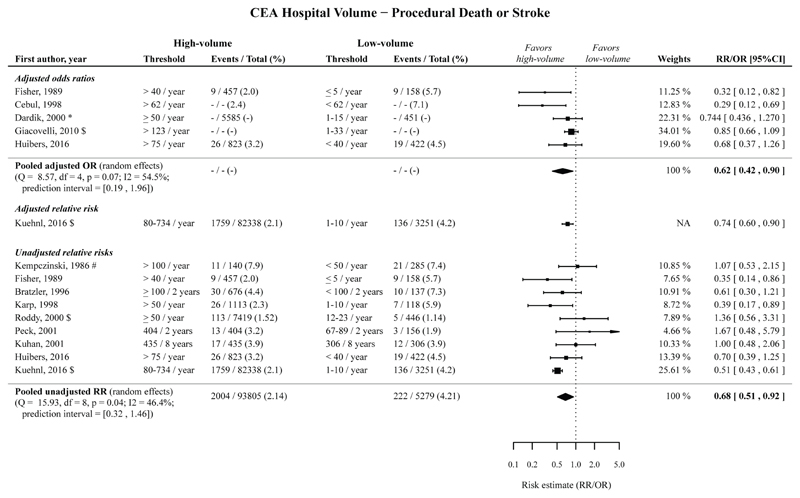

CEA hospital volume

High hospital volume compared to low operator volume was significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death or stroke following CEA, with a pooled adjusted OR of 0.62 (95%CI 0.42-0.90; 5 cohorts),20,26,38–40 with an adjusted RR of 0.74 (95%CI 0.60-0.90; 1 cohort),41 and with an pooled unadjusted RR of 0.68 (95%CI 0.51-0.92; 9 cohorts).20,36,39,41–46 (Figure 3; Table 2).

Figure 3.

Risk estimates and meta-analysis for the association between CEA hospital volume (high vs. low volume) for the outcome procedural death or stroke. Pooled estimates are based on a random effects model. Point sizes of the individual studies are proportional to the standard error of the specific study. Point estimates without confidence intervals were not included in the meta-analyses, and can be found in Appendix Figure 20.

The timeframe for the measured outcomes is depicted as follows: no symbol 30-days outcome, * perioperative, # postoperative, $ in-hospital, § not further specified. CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

The pooled adjusted ORs and pooled unadjusted RRs, with low operator volume taken as reference, showed that high hospital volume is significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke separately following CEA. (Table 2; Appendix Figure 6-7).

The pooled unadjusted RR showed that high hospital volume was significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural MI following CEA. The adjusted OR showed that high hospital volume is not significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural MI following CEA. The associations for procedural death, stroke or MI, and procedural cranial nerve injury following CEA were not statistically significant. (Table 2; Appendix Figure 8-10).

Among studies reporting on procedural death or stroke, procedural death, and procedural stroke, the prediction intervals for studies reporting unadjusted RRs for procedural stroke, and adjusted ORs for procedural death were below 1. The other prediction intervals were wider, but except for the prediction interval for procedural stroke (prediction interval: 0.10-3.85) the upper bound did not exceed 2.

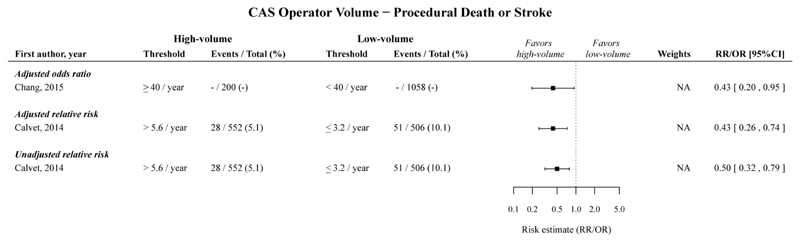

CAS operator volume

High operator volume compared to low operator volume was significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death or stroke following CAS, with an adjusted OR of 0.43 (95%CI 0.20-0.95; 1 cohort),47 with an adjusted RR of 0.43 (95%CI 0.26-0.74; 1 cohort),48 and with an unadjusted RR of 0.50 (95%CI 0.32-0.79; 1 cohort).48(Figure 4; Table 2).

Figure 4.

Risk estimates and meta-analysis for the association between CAS operator volume (high vs. low volume) for the outcome procedural death or stroke. No pooled estimates are provided, because only one study per category was included. Point estimates without confidence intervals were not included in the meta-analyses, and can be found in Appendix Figure 21.

The timeframe for the measured outcomes is depicted as follows: no symbol 30-days outcome, * perioperative, # postoperative, $ in-hospital, § not further specified. CAS, carotid artery stenting; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

The pooled adjusted ORs and pooled unadjusted RRs, with low operator volume taken as reference, showed that high operator volume is significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke separately following CAS (Table 2; Appendix Figure 11-12).

No studies reported on procedural MI after CAS, and the association for procedural death, stroke or MI following CAS was not statistically significant. (Table 2; Appendix Figure 13-14).

No substantial heterogeneity was found in the three meta-analyses performed for CAS operator volume and no prediction intervals could be estimated because the number of studies per meta-analysis was ≤2.

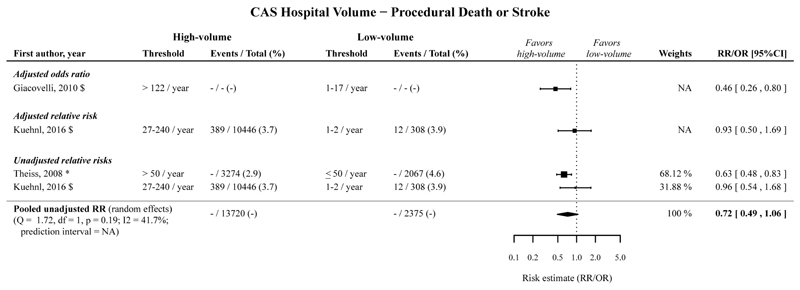

CAS hospital volume

High hospital volume compared to low hospital volume was significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death or stroke following CAS, with an adjusted OR of 0.46 (95%CI 0.26-0.80; 1 cohort),40, and not significantly associated with an adjusted RR of 0.93 (95%CI 0.50-1.69; 1 cohort),41 and a pooled unadjusted RR of 0.72 (95%CI 0.49-1.06; 2 cohorts).41,49 (Figure 5; Table 2).

Figure 5.

Risk estimates and meta-analysis for the association between CAS hospital volume (high vs. low volume) for the outcome procedural death or stroke. No pooled estimates are provided, because only one study per category was included.

The timeframe for the measured outcomes is depicted as follows: no symbol 30-days outcome, * perioperative, # postoperative, $ in-hospital, § not further specified. CAS, carotid artery stenting; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk.

The pooled adjusted ORs and pooled unadjusted RRs, with low hospital volume taken as reference, showed that high hospital volume is significantly associated with a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke separately following CAS. (Table 2; Appendix Figure 15-16).

The associations for procedural MI, and procedural death, stroke or MI following CAS were not statistically significant. (Table 2; Appendix Figure 17-18).

Cochran’s Q was >0.05 for all five meta-analyses for the CAS hospital volume-outcome relationship. Two prediction intervals could be estimated for studies reporting unadjusted RRs for procedural stroke (prediction interval: 0.60-1.08), and unadjusted RRs for procedural death (prediction interval: 0.22-2.21).

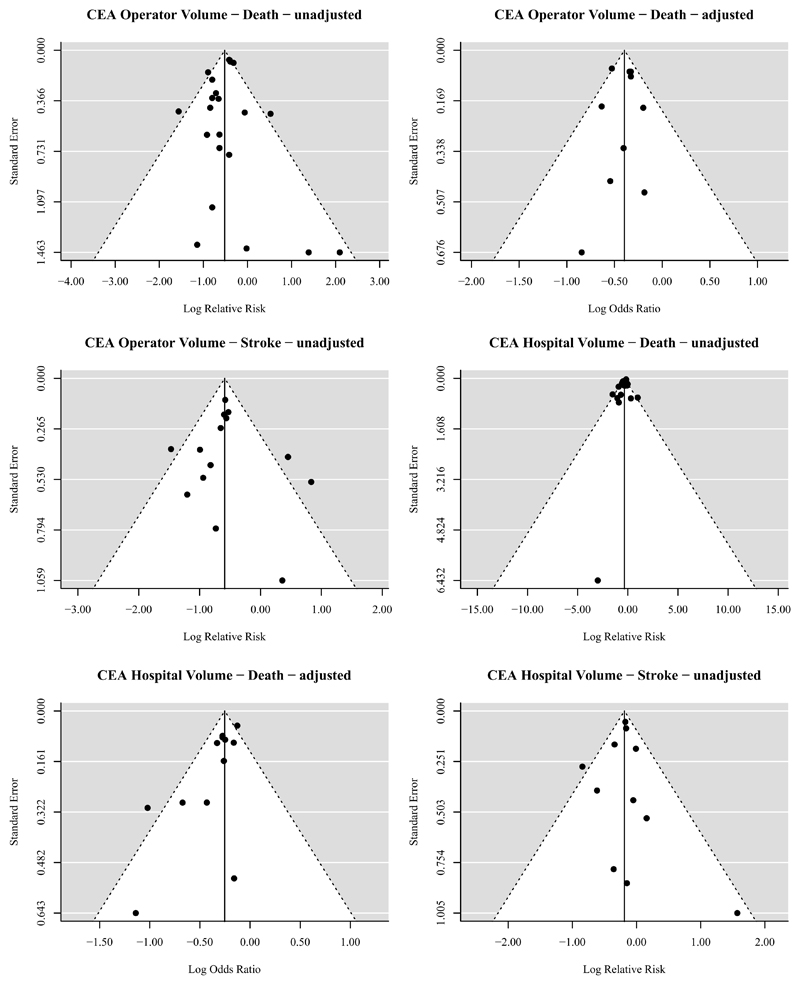

Publication bias

Asymmetry in the funnel plots was found for studies presenting adjusted associations between CEA hospital volume and procedural death (Egger’s regression p=0.0012), indicating that there is statistical evidence for publication bias. No asymmetry was found for studies presenting other unadjusted and adjusted associations, indicating that there is no statistical evidence for publication bias for these procedural outcomes. (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Funnel plots for all determinant-outcome relations with at least 10 studies. Adjusted or unadjusted in the title refers to the effect estimates under study, i.e. unadjusted/crude relative risks or adjusted odds ratios. Statistically significant asymmetry, indicating statistical evidence for publication bias, was only found within the funnel plot for the reported adjusted associations between CEA hospital volume and death with an Egger’s regression p=0.0012.

Sensitivity analysis

Limited to studies from North America, we found similar associations between CEA operator and hospital volume and procedural death or stroke (Appendix Table 9). For CAS, no studies were found from North America reporting on procedural death or stroke. We found only one study reporting on operator volume that adjusted for symptomatic status of the patients undergoing CEA and no studies reporting on hospital volume adjusted for symptomatic status. We found similar results if the inclusion for analysis was restricted to studies that adjusted for the other determinant. Limited to more recently treated patients, we found similar results (i.e. direction and size of risk estimate) for CEA operator volume, CAS operator and CAS hospital volume and procedural death or stroke. However, the 95%-CI of the association between CEA hospital volume and procedural death or stroke widened and included one, due to the lower number of included studies.

When limited to studies with higher low-volume thresholds or studies with lower high-volume threshold the direction and size of the association between CEA operator or hospital volume and procedural death or stroke remained stable. In a few comparisons, the risk estimates became statistically non-significant, because the pooled risk estimates had wider 95%-CI due to the less number of cohorts included in these sensitivity analyses. For CAS, the sensitivity analyses with volume thresholds showed similar results compared to the primary analyses.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis shows a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke following CEA and CAS in high operator and high hospital volume. For CEA, the unadjusted and adjusted pooled risk estimates for procedural death or stroke, procedural death and procedural stroke almost all show better outcomes in high volume operators and hospital. For CAS, similar results were found in a limited number of studies. The association between operator or hospital volume and procedural MI; procedural death, stroke or MI; and procedural cranial nerve injury has been less extensively studied, leading to less robust results. Importantly, we found limited evidence for publication bias.

Historically, two explanations have been proposed for the observed association between volume and outcome: The practice-makes-perfect hypothesis (note that this term has been criticized for being used in volume assessment but rather describes learning curve assessment50), assumes that the increasing experience of an operator or hospital leads to a reduction in adverse events. The selective-referral-pattern hypothesis stresses the influence of higher number of patient referrals to operators and hospital with better outcomes.51 The latter hypothesis assumes high volume operators and hospitals select lower risk patients. However, in our meta-analyses, pooled unadjusted risks for death or stroke were comparable to adjusted risks. Furthermore, hospital readmission rates may be partly linked to hospital quality, regardless of patient-related factors.52

It is often assumed that the experience or skill of the operator has an important impact on outcomes.53 This is underlined by a study in which operator volume remained statistically significantly associated with CEA procedural death after extra adjustment for hospital volume.54

Our literature search was extensive and the inclusion of studies in our study was only influenced by suitability for the analyses. Our findings strengthen the evidence that operator and hospital volume influence the outcome following CEA and CAS.55

Nonetheless, our study has several limitations. First, there was considerable heterogeneity in volume definitions and thresholds. For this reason, the magnitude of the effect could only be measured for the dichotomized determinant volume groups: high versus low. Since most original studies did not pre-specify thresholds and possibly selected thresholds to maximize differences in outcome between volume groups, bias might be introduced. Next to that, not all studies provided data on annual volume, but sometimes different timeframes were used. Second, the majority of the included studies used administrative data as data source that might be of inferior quality with regard to symptom status, high-risk status, and perioperative stroke.56,57

Third, individual operator experience or ‘learning curve’ is knowingly not included as a determinant in this study.58–61 The experience prior to the measured timeframe is unknown. The influence of developing clinical practice and the position of the operator on the learning curve might be underestimated, and the influence of other provider characteristics such as academic status of the hospital and experience with carotid interventions in high-risk patients is unknown.62

Fourth, the assessment of the relationship between volume and outcome is hampered since not all studies adjusted for characteristics that are known to influence outcome following carotid revascularization (Appendix Tables 5-6).6,63–65

Fifth, we may have missed publications where operator and hospital volume was assessed but not clearly reported.

Sixth, despite our efforts to prevent double-counting of patients by excluding overlapping datasets from meta-analyses, studies based on administrative datasets could potentially still have included overlapping patient groups.

Our results indicate an association between increasing volume and decreasing procedural death and stroke. Studies investigating determinants of outcome following carotid revascularization should adjust for operator volume and hospital volume. Heterogeneity in thresholds and definitions of determinants and outcomes emphasizes the need for clear definitions in order to improve the comparability of studies. Our findings question the decision of the Leapfrog initiative to drop volume standard for CEA as safety standard in surgical procedures.11,17 The heterogeneity in the identified studies cannot justify direct introduction of set volume-thresholds, but do call for a closer examination of volume-effects within carotid revascularization.

The possibility of another relationship besides a dichotomized high versus low volume groups might be clinically relevant. For this reason, we extracted data from studies in which the volume-outcome relation was assessed continuously. The possibility of a plateau phase in which the effect of additional cases per year after a certain number minimally affects outcomes should be considered, since this was found for many surgical procedures.

In conclusion, our study shows a decreased risk of death and stroke following CEA and CAS in high operator and high hospital volume. The association for CAS has been studied in fewer studies. The relationship of operator and hospital volume with procedural MI and procedural cranial nerve injury has less extensively been studied and therefore remains uncertain. Our results indicate that aiming for a high operator and hospital volume may help minimizeadverse events following carotid revascularization. Further research is needed to establish the optimum volume thresholds balancing a minimum adverse event rate and practical feasibility.

Supplementary Material

Mini-abstract.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the association between operator volume and hospital volume and the outcomes following CEA or CAS. Associations between high operator and high hospital volume and a decreased risk of procedural death and stroke following CEA and CAS were found.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank J.A.A.G. Damen (Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, and Cochrane Netherlands, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands) for her advice on the meta-analyses and heterogeneity methodology. P. Wiersma (Medical information specialist library Utrecht University, The Netherlands) for her help with designing the search strategy. We would like to thank the following authors for providing additional data: G. Ailawadi, D.W. Bratzler, A. Dardik and T. Westvik, S. Desai, A. Huibers, S. Kao and C.-S. Hung, J.-W. Lin, N. Sahni, D. Sidloff, P. Stavrinou. No one received compensation outside of their usual salary.

Funding

Professor Halliday’s research is funded by the UK Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

MHF: None

ECB: None

AH: None

RB: None

MB: None

GJdB: None

Author contributions

MHFP, ECB, GJdB conceived the original idea for the study. All authors were involved in acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. MHFP and ECB performed the statistical analysis. The manuscript was drafted by MHFP, ECB, and GJdB with input from all co-authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was done by all authors. Study supervision was done by GJdB. GJdB is guarantor for this article.

References

- 1.Rerkasem K, Rothwell PM. Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001081.pub2. CD001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huibers A, Calvet D, Kennedy F, et al. Mechanism of Procedural Stroke Following Carotid Endarterectomy or Carotid Artery Stenting Within the International Carotid Stenting Study (ICSS) Randomised Trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobowitz GR, Rockman CB, Lamparello PJ, et al. Causes of perioperative stroke after carotid endarterectomy: special considerations in symptomatic patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 2001;15:19–24. doi: 10.1007/s100160010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riles TS, Imparato AM, Jacobowitz GR, et al. The cause of perioperative stroke after carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1994;19:206–214. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(94)70096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Borst GJ, Moll FL, van de Pavoordt HD, et al. Stroke from carotid endarterectomy: when and how to reduce perioperative stroke rate? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:484–489. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2001.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, et al. Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet. 2004;363:915–924. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15785-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rerkasem K, Rothwell PM. Patch angioplasty versus primary closure for carotid endarterectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000160.pub3. CD000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonati LH, Lyrer P, Ederle J, et al. Percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000515.pub4. CD000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaniyapong T, Chongruksut W, Rerkasem K. Local versus general anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000126.pub4. CD000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aburahma AF, Mousa AY, Stone PA. Shunting during carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1502–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer CM. Volume standards for high-risk surgical procedures: potential benefits of the Leapfrog initiative. Surgery. 2001;130:415–422. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.117139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins LN, Roubin GS, Chakhtoura EY, et al. The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial: credentialing of interventionalists and final results of lead-in phase. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobson RW, Howard VJ, Roubin GS, et al. Credentialing of surgeons as interventionalists for carotid artery stenting: experience from the lead-in phase of CREST. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mas JL, Chatellier G, Beyssen B, et al. Endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1660–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckstein HH, Ringleb P, Allenberg JR, et al. Results of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:893–902. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ederle J, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, et al. Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:985–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian CK, Gustafson ML, Betensky RA, et al. The Leapfrog volume criteria may fall short in identifying high-quality surgical centers. Ann Surg. 2003;238:447–455. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089850.27592.eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huibers A, de Waard D, Bulbulia R, et al. Clinical Experience amongst Surgeons in the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial-1. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;42:339–345. doi: 10.1159/000446079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley RD, Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172:137–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www cochrane-handbook org 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dardik A, Bowman HM, Gordon TA, et al. Impact of race on the outcome of carotid endarterectomy: a population-based analysis of 9,842 recent elective procedures. Ann Surg. 2000;232:704–709. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kucey DS, Bowyer B, Iron K, et al. Determinants of outcome after carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maas MB, Jaff MR, Rordorf GA. Risk adjustment for case mix and the effect of surgeon volume on morbidity. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:532–536. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray WA, White HJ, Jr, Barrett DM, et al. Carotid stenting and endarterectomy: a clinical and cost comparison of revascularization strategies. Stroke. 2002;33:1063–1070. doi: 10.1161/hs0402.105304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slavish LG, Nicholas GG, Gee W. Review of a community hospital experience with carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 1984;15:956–959. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aburahma AF, Stone PA, Srivastava M, et al. The effect of surgeon's specialty and volume on the perioperative outcome of carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:666–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feasby TE, Quan H, Ghali WA. Hospital and surgeon determinants of carotid endarterectomy outcomes. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1877–1881. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.12.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattos MA, Modi JR, Mansour AM, et al. Evolution of carotid endarterectomy in two community hospitals: Springfield revisited--seventeen years and 2243 operations later. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:719–726. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(05)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aburahma AF, Boland J, Robinson P. Complications of carotid endarterectomy: the influence of case load. South Med J. 1988;81:711–715. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198806000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brott T, Thalinger K. The practice of carotid endarterectomy in a large metropolitan area. Stroke. 1984;15:950–955. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.6.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kempczinski RF, Brott TG, Labutta RJ. The influence of surgical specialty and caseload on the results of carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:911–916. doi: 10.1067/mva.1986.avs0030911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruby ST, Robinson D, Lynch JT, et al. Outcome analysis of carotid endarterectomy in Connecticut: the impact of volume and specialty. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10:22–26. doi: 10.1007/BF02002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cebul RD, Snow RJ, Pine R, et al. Indications, outcomes, and provider volumes for carotid endarterectomy. JAMA. 1998;279:1282–1287. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher ES, Malenka DJ, Solomon NA, et al. Risk of carotid endarterectomy in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1617–1620. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.12.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giacovelli JK, Egorova N, Dayal R, et al. Outcomes of carotid stenting compared with endarterectomy are equivalent in asymptomatic patients and inferior in symptomatic patients. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:906–13, 913. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuehnl A, Tsantilas P, Knappich C, et al. Significant Association of Annual Hospital Volume With the Risk of Inhospital Stroke or Death Following Carotid Endarterectomy but Likely Not After Carotid Stenting: Secondary Data Analysis of the Statutory German Carotid Quality Assurance Database. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e004171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bratzler DW, Oehlert WH, Murray CK, et al. Carotid endarterectomy in Oklahoma Medicare beneficiaries: patient characteristics and outcomes. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1996;89:423–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karp HR, Flanders WD, Shipp CC, et al. Carotid endarterectomy among Medicare beneficiaries: a statewide evaluation of appropriateness and outcome. Stroke. 1998;29:46–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peck C, Peck J, Peck A. Comparison of carotid endarterectomy at high- and low-volume hospitals. Am J Surg. 2001;181:450–453. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roddy SP, O'Donnell TF, Jr, Wilson AL, et al. The Balanced Budget Act: potential implications for the practice of vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(00)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuhan G, Gardiner ED, Abidia AF, et al. Risk modelling study for carotid endarterectomy. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1590–1594. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang CH, Lin JW, Lin CH, et al. Effectiveness and safety of extracranial carotid stent placement: a nationwide self-controlled case-series study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Calvet D, Mas JL, Algra A, et al. Carotid stenting: is there an operator effect? A pooled analysis from the carotid stenting trialists' collaboration. Stroke. 2014;45:527–532. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theiss W, Hermanek P, Mathias K, et al. Predictors of death and stroke after carotid angioplasty and stenting: a subgroup analysis of the Pro-CAS data. Stroke. 2008;39:2325–2330. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gandjour A, Lauterbach KW. The practice-makes-perfect hypothesis in the context of other production concepts in health care. Am J Med Qual. 2003;18:171–175. doi: 10.1177/106286060301800407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luft HS, Hunt SS, Maerki SC. The volume-outcome relationship: practice-makes-perfect or selective-referral patterns? Health Serv Res. 1987;22:157–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krumholz HM, Wang K, Lin Z, et al. Hospital-Readmission Risk - Isolating Hospital Effects from Patient Effects. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1055–1064. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1702321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maruthappu M, Gilbert BJ, El Harasis MA, et al. The influence of volume and experience on individual surgical performance: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2015;261:642–647. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doig D, Turner EL, Dobson J, et al. Risk Factors For Stroke, Myocardial Infarction, or Death Following Carotid Endarterectomy: Results From the International Carotid Stenting Study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hertzer NR. Reasons why data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample can be misleading for carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting. Semin Vasc Surg. 2012;25:13–17. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bensley RP, Yoshida S, Lo RC, et al. Accuracy of administrative data versus clinical data to evaluate carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wayangankar SA, Aronow HD. Carotid Artery Stenting: Operator and Institutional Learning Curves. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2014;3:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.iccl.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smout J, Macdonald S, Weir G, et al. Carotid artery stenting: relationship between experience and complication rate. Int J Stroke. 2010;5:477–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kouvelos G, Koutsoumpelis A, Arnaoutoglou E, et al. The effect of increasing operator experience on procedure-related characteristics in patients undergoing carotid artery stenting. Vascular. 2017;25:488–496. doi: 10.1177/1708538117691431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrafiello G, De Lodovici ML, Piffaretti G, et al. Carotid artery stenting: Influence of experience and cerebrovascular risk factors on outcome. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burke LG, Frakt AB, Khullar D, et al. Association Between Teaching Status and Mortality in US Hospitals. JAMA. 2017;317:2105–2113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Howard G, Roubin GS, Jansen O, et al. Association between age and risk of stroke or death from carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting: a meta-analysis of pooled patient data from four randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003;361:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Volkers EJ, Greving JP, Hendrikse J, et al. Body mass index and outcome after revascularization for symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Neurology. 2017;88:2052–2060. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.