Abstract

Background

Surgical‐site infection (SSI) is a serious surgical complication that can be prevented by preoperative skin disinfection. In Western European countries, preoperative disinfection is commonly performed with either chlorhexidine or iodine in an alcohol‐based solution. This study aimed to investigate whether there is superiority of chlorhexidine–alcohol over iodine–alcohol for preventing SSI.

Methods

This prospective cluster‐randomized crossover trial was conducted in five teaching hospitals. All patients who underwent breast, vascular, colorectal, gallbladder or orthopaedic surgery between July 2013 and June 2015 were included. SSI data were reported routinely to the Dutch National Nosocomial Surveillance Network (PREZIES). Participating hospitals were assigned randomly to perform preoperative skin disinfection using either chlorhexidine–alcohol (0·5 per cent/70 per cent) or iodine–alcohol (1 per cent/70 per cent) for the first 3 months of the study; every 3 months thereafter, they switched to using the other antiseptic agent, for a total of 2 years. The primary endpoint was the development of SSI.

Results

A total of 3665 patients were included; 1835 and 1830 of these patients received preoperative skin disinfection with chlorhexidine–alcohol or iodine–alcohol respectively. The overall incidence of SSI was 3·8 per cent among patients in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group and 4·0 per cent among those in the iodine–alcohol group (odds ratio 0·96, 95 per cent c.i. 0·69 to 1·35).

Conclusion

Preoperative skin disinfection with chlorhexidine–alcohol is similar to that for iodine–alcohol with respect to reducing the risk of developing an SSI.

Abstract

Antecedentes

La infección del sitio quirúrgico (surgical site infection, SSI) es una complicación quirúrgica grave que se puede prevenir mediante una desinfección cutánea preoperatoria. En los países de Europa occidental, la desinfección preoperatoria se realiza habitualmente usando clorhexidina o yodo en una solución a base de alcohol. Nuestro objetivo fue investigar si la clorhexidina alcohólica es superior al yodo con alcohol para prevenir la SSI.

Métodos

Este ensayo prospectivo aleatorizado por conglomerados y de grupos cruzados se realizó en cinco hospitales docentes. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes que se sometieron a cirugía mamaria, vascular, colorrectal, biliar y ortopédica entre julio de 2013 y junio de 2015. Los datos de SSI se presentaron de manera rutinaria a la Red Nacional Holandesa de Vigilancia Nosocomial (PREZIES). Los hospitales participantes fueron asignados al azar para realizar una desinfección cutánea preoperatoria con clorhexidina alcohólica (0,5%/70%) o yodo con alcohol (1%/70%) durante los primeros tres meses del estudio; cada 3 meses a partir de entonces, cambiaron a usar el otro agente antiséptico, durante un total de 2 años. El criterio de valoración principal fue el desarrollo de SSI.

Resultados

Se incluyeron un total de 3.665 pacientes; 1.835 y 1.830 de estos pacientes recibieron desinfección cutánea preoperatoria con clorhexidina alcohólica o yodo con alcohol, respectivamente. La incidencia global de SSI fue del 3,8% entre los pacientes en el grupo de clorhexidina alcohólica y del 4,0% entre los pacientes en el grupo de yodo con alcohol (razón de oportunidades, odds ratio, OR 0,96; i.c. del 95%: 0,69‐1,35).

Conclusión

La desinfección cutánea preoperatoria con clorhexidina alcohólica es similar al yodo con alcohol con respecto a la reducción del riesgo de desarrollar una SSI.

Introduction

Surgical‐site infection (SSI) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and increased healthcare costs. From 2007 to 2013, the overall incidence of SSI among surgical patients in the Netherlands was approximately 3·7 per cent, making SSI the most frequent form of hospital‐acquired infection1, 2. In the Netherlands alone, approximately 1·5 million surgical procedures are performed each year; therefore, even a slight reduction in the incidence of SSI would significantly improve patient outcome and drastically reduce healthcare costs.

One of the most important steps in preventing an SSI is meticulous preoperative disinfection of the skin using an antiseptic agent. The Dutch Guideline for Infection Prevention3 recommends the preoperative application of either chlorhexidine or iodine in an alcohol solution. Until about 5 years ago, these two antiseptic agents were used relatively interchangeably in Dutch hospitals; however, most Dutch hospitals now preferentially use chlorhexidine–alcohol for disinfecting the skin before surgery. This decision to use chlorhexidine–alcohol was based largely on a large trial conducted by Darouiche and colleagues4, which found that chlorhexidine–alcohol provided better results than iodine in an aqueous solution for preventing SSI in surgical patients with a clean‐contaminated wound4, 5. Because alcohol has its own antiseptic properties, however, the results obtained by Darouiche et al. may not necessarily be applicable to routine clinical practice6. In addition, the concentration of chlorhexidine–alcohol used by Darouiche and co‐workers was higher than that commonly used in surgical practice in the Netherlands (2 versus 0·5 per cent respectively).

Currently, little evidence is available indicating whether chlorhexidine–alcohol or iodine–alcohol is more effective at reducing the risk of SSI in patients undergoing general or orthopaedic surgery. This multicentre cluster‐randomized crossover trial aimed to compare directly the risk of SSI following preoperative skin disinfection with 0·5 per cent chlorhexidine–alcohol and 1 per cent iodine–alcohol.

Methods

The SKINFECT trial was conducted from July 2013 to June 2015 as a cluster‐randomized crossover trial in cooperation with the Netherlands National Nosocomial Surveillance Network (in Dutch: PREventie van ZIEkenhuisinfecties door Surveillance, or PREZIES). Each participating hospital (cluster) was assigned randomly to apply preoperative skin disinfection using either chlorhexidine–alcohol (0·5 per cent/70 per cent) or iodine–alcohol (1 per cent/70 per cent). No specifications were given for the manufacturer of the antiseptics. Every 3 months thereafter, participating hospitals switched to using the other antiseptic agent (crossover). This process was repeated until the end of the 2‐year study period, with a total of seven crossover events and eight 3‐month treatment periods. Participating hospitals preferably started at the beginning of the study, but could join at a later time if necessary.

The SKINFECT trial was registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR4004). The rationale for cluster randomization was that it was deemed impractical to perform individual randomization in the operating room. In addition, this study design provided greater generalizability to general practice, given the likelihood of other, unknown, antiseptic practices in most hospitals (for example glove changes, number of door openings during surgery). Compliance with the study protocol was confirmed by quarterly visits to each participating hospital, telephone notification for each crossover to the other antiseptic agent, electronic newsletters, and reminder posters placed in operating rooms. The study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of South‐West Holland and by the respective institutional review board at each participating hospital. The review board waived the need for informed consent, as both antiseptic agents can be used interchangeably in accordance with national guidelines and are therefore not considered to be experimental agents5. All data were reported in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines for cluster‐randomized studies7.

Study outcomes

The primary study outcome was the occurrence of a superficial or deep SSI within 30 days of surgery (or 90 days in the case of an implant). The secondary outcome was the result of wound cultures in the event of an SSI. Definitions established by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) were used2.

Data collection, study population and definitions

Data were collected from the national SSI surveillance database in PREZIES. Nearly all Dutch hospitals participate in the voluntary PREZIES SSI surveillance programme, which annually selects several surgical procedures for surveillance from a predefined list (Table S1 , supporting information). Data collected include patient data, type of surgery performed, a select number of possible risk factors, and the presence of an SSI. An SSI is defined based on the criteria established by the CDC and ECDC, and confirmed by trained hospital personnel. Retrospective on‐site validation is also performed periodically with chart–database comparisons. Superficial SSIs are distinguished from deep SSIs, with a deep SSI defined as a deep incisional SSI or an organ‐space SSI. Details regarding these definitions have been published previously8.

Hospitals were considered for inclusion as a cluster if they participated in the PREZIES SSI surveillance programme and routinely reported standardized SSI data for breast, colorectal, vascular, orthopaedic and gallbladder surgery. All such consecutive operations performed between July 2013 and June 2015 in the participating hospitals in patients aged at least 18 years were included in the trial.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculations were performed using a simulation (performed in R; http://www.r‐project.org), assuming an overall SSI incidence of 5 per cent. This simulation indicated that with a power of 80 per cent, a two‐sided α level of 0·05 and ten clusters, a minimum number of 4000 surgeries was required to detect an absolute difference of 2 per cent in the incidence of SSI.

Statistical analysis

The difference between the effect of the two antiseptic agents on the risk of an SSI was analysed using multivariable multilevel logistic regression techniques, thereby creating an odds ratio (OR). All analyses were performed for all surgical procedures combined, while taking into account different baseline risks between surgical specialties (fixed effect), treatment period (fixed effect) and hospitals (random effect)9. Co‐variables associated with the risk of an SSI in univariable analysis were considered potential confounders and included in the subsequent models if the effect of the intervention changed by 10 per cent or more. Overall, the results were considered statistically significant if the 95 per cent c.i. of the OR did not span the value 1·0. All analyses were based on the intention‐to‐treat principle; thus, all eligible patients were included in the analysis of the clusters to which they were randomized, regardless of whether they actually received the assigned antiseptic or not.

Descriptive analyses were performed using SPSS® version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). Regression analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Five hospitals participated as a cluster. One of these five participating hospitals entered the study in the fourth cluster period.

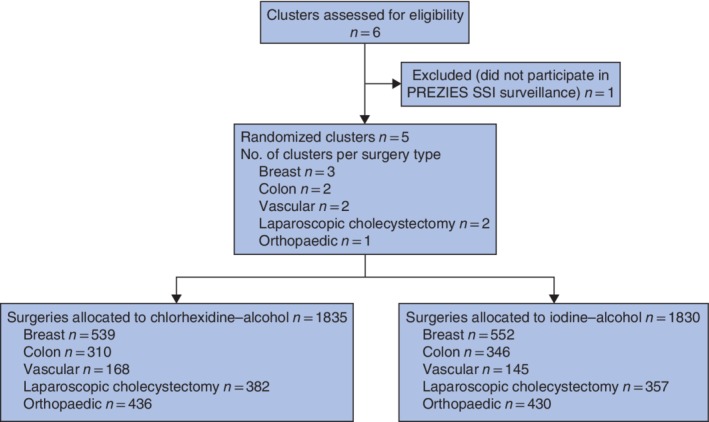

Between July 2013 and June 2015, a total of 3665 patients were included from the five participating hospitals; 1835 patients were randomized to receive chlorhexidine–alcohol skin antiseptic and 1830 to receive iodine–alcohol (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participating hospitals and patients. PREZIES, PREventie van ZIEkenhuisinfecties door Surveillance (Dutch National Nosocomial Surveillance Network); SSI, surgical‐site infection.

The following types of surgery were included in the study: colorectal surgery (656 patients in two hospitals), vascular surgery (313 patients in two hospitals), laparoscopic cholecystectomy (739 patients in two hospitals), breast surgery (1091 patients in three hospitals), and total hip or knee arthroplasty (866 patients in one hospital). Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the chlorhexidine–alcohol and iodine–alcohol groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study demographics

| Chlorhexidine–alcohol (n = 1835) | Iodine–alcohol (n = 1830) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 65 (19–94) | 65 (18–98) |

| Sex | ||

| M | 518 (28·2) | 526 (28·7) |

| F | 1317 (71·8) | 1304 (71·3) |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26·5 (15·8–66·2) | 26·5 (15·0–49·6) |

| Wound classification | ||

| Clean | 1139 (62·1) | 1118 (61·1) |

| Clean‐contaminated | 617 (33·6) | 635 (34·7) |

| Contaminated | 48 (2·6) | 46 (2·5) |

| Dirty | 20 (1·1) | 19 (1·0) |

| Unknown | 11 (0·6) | 12 (0·7) |

| ASA fitness grade | ||

| I | 399 (21·7) | 397 (21·7) |

| II | 1137 (62·0) | 1120 (61·2) |

| III | 266 (14·5) | 272 (14·9) |

| IV | 19 (1·0) | 25 (1·4) |

| V | 1 (0·1) | 2 (0·1) |

| Unknown | 13 (0·7) | 14 (0·8) |

| Malignancy | ||

| Yes | 724 (39·5) | 745 (40·7) |

| No | 898 (48·9) | 909 (49·7) |

| Unknown | 213 (11·6) | 176 (9·6) |

| Implant | ||

| Yes | 578 (31·5) | 567 (31·0) |

| No | 1257 (68·5) | 1263 (69·0) |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Breast | 539 (29·4) | 552 (30·2) |

| Vascular | 168 (9·2) | 145 (7·9) |

| Colorectal | 310 (16·9) | 346 (18·9) |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 382 (20·8) | 357 (19·5) |

| THA/TKA | 436 (23·8) | 430 (23·5) |

| Duration of surgery (min)* | 80 (10–393) | 81 (13–401) |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | ||

| Yes | 1156 (63·0) | 1175 (64·2) |

| No | 177 (9·6) | 162 (8·9) |

| Unknown | 502 (27·4) | 493 (26·9) |

| NNIS grade | ||

| 0 | 1036 (56·5) | 1024 (56·0) |

| 1 | 682 (37·2) | 676 (36·9) |

| 2 | 87 (4·7) | 99 (5·4) |

| 3 | 7 (0·4) | 6 (0·3) |

| Unknown | 23 (1·3) | 25 (1·4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range). THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; NNIS, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance classification.

Primary outcome

The overall incidence of SSI was 3·8 per cent among patients in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group and 4·0 per cent among those in the iodine–alcohol group. There was no significant difference between the groups in multivariable analysis (OR 0·96, 95 per cent c.i. 0·69 to 1·35) (Table 2). When results were stratified based on the severity of SSI, the same findings were observed. The rate of superficial SSI was 1·7 per cent in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group and 1·9 per cent in the iodine–alcohol group (OR 1·13, 0·70 to 1·85). The rate of deep SSI was 2·1 per cent in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group and 2·1 per cent in the iodine–alcohol group (OR 1·00, 0·64 to 1·57). Similar results were obtained when analysis was performed by type of surgery. Factors significantly associated with SSI incidence included wound classification, ASA fitness grade, duration of surgery, patient sex and age at the time of surgery.

Table 2.

Summary of the incidence of surgical‐site infection

| Chlorhexidine–alcohol (n = 1835) | Iodine–alcohol (n = 1830) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of hospitals | No. of surgeries | No. of SSIs* | No. of surgeries | No. of SSIs* | Crude OR† | Multilevel OR†, ‡ | Co‐variables | |

| All surgeries combined | 5 | 1835 | 70 (3·8) | 1830 | 74 (4·0) | 0·94 (0·67, 1·31) | 0·96 (0·69, 1·35) | Surgical specialty added as fixed effect |

| Colorectal surgery | 2 | 310 | 30 (9·7) | 346 | 33 (9·5) | 1·02 (0·60, 1·71) | Identical to crude OR | |

| Breast surgery | 3 | 539 | 11 (2·0) | 552 | 10 (1·8) | 1·13 (0·48, 2·68) | Identical to crude OR | |

| Vascular surgery | 2 | 168 | 10 (6·0) | 145 | 9 (6·2) | 0·96 (0·38, 2·43) | Identical to crude OR | |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 2 | 382 | 12 (3·1) | 357 | 17 (4·8) | 0·65 (0·30, 1·38) | Identical to crude OR | |

| Total hip/knee arthroplasty | 1 | 436 | 7 (1·6) | 430 | 5 (1·2) | 1·39 (0·44, 4·41) | Identical to crude OR | |

Values in parentheses are

percentages and

95 per cent confidence intervals.

Hospital added as a random effect; this did not result in a significant difference in the analysis. SSI, surgical‐site infection; OR, odds ratio.

Secondary outcome

Culture test results were available for 108 of the 144 SSIs (75·0 per cent) (Tables S2 and S3 , supporting information). A total of 161 pathogens were cultured, including 40 cases (24·8 per cent) of Staphylococcus aureus and 25 cases of Escherichia coli (15·5 per cent); 21 of these E. coli cases occurred after colorectal surgery. There was no statistically significant difference between the chlorhexidine–alcohol and iodine–alcohol group with respect to the culture results, although 24 of the S. aureus cultures were in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group compared with 16 in the iodine–alcohol group (OR 1·50, 95 per cent c.i. 0·79 to 2·73).

Discussion

In recent years, several studies4, 10, 11, 12 have compared the efficacy of preoperative chlorhexidine versus iodine in preventing SSI. However, most studies compared chlorhexidine in an alcohol solution with iodine in an aqueous solution, thereby confounding the analysis. The present study compared the efficacy of chlorhexidine and iodine in the same solution (70 per cent alcohol) in preventing SSI in several types of surgery, and found them to be similar. The results did not differ when stratified based on severity of surgery. No stratifications were done for implant placement, because this was done for all arthroplasties and the number of SSIs was too low in vascular procedures to analyse the effect of the different antiseptics.

The incidence of SSI in this study varied among surgery type and was more or less consistent with previous data from 2009–2014 in the Netherlands8. Three previous studies10, 12, 13 have compared chlorhexidine–alcohol with iodine–alcohol for preventing SSI, yielding conflicting results. Swenson and colleagues13 conducted a single‐centre study of 3209 patients undergoing general surgery, and compared iodine in aqueous solution with chlorhexidine–alcohol (ChloraPrep®; Cardinal Health, Dublin, Ohio, USA) and iodine–alcohol (DuraPrep™; 3 M, Maplewood, Minnesota, USA). They found SSI rates of 6·4, 7·1 and 3·9 per cent respectively, suggesting that iodine–alcohol is more effective at preventing SSI. Broach and co‐workers12 performed a randomized non‐inferiority trial comparing iodine–alcohol and chlorhexidine–alcohol in clean‐contaminated wounds in colorectal surgery. They found the incidence of SSI was 2·8 per cent lower in the chlorhexidine–alcohol group, although this difference was not statistically significant. Tuuli et al. 10 compared antiseptic agents in patients undergoing caesarean delivery (clean‐contaminated surgery) and found superiority for chlorhexidine–alcohol compared with iodine–alcohol (SSI rate 4·3 versus 7·3 per cent respectively).

A concentration of 0·5 per cent chlorhexidine in alcohol was used in the present study. Literature regarding the most appropriate concentration of chlorhexidine is sparse. In a randomized trial of 100 patients, Casey and colleagues14 compared 2 per cent chlorhexidine with 0·5 per cent chlorhexidine. Chlorhexidine 2 per cent significantly reduced the number of microorganisms on the skin, but did not reduce the incidence of SSI. In addition, McCann et al. 15 found no significant difference in catheter‐related or catheter‐associated bloodstream infections in patients disinfected with 2 per cent chlorhexidine compared with other concentrations.

A strength of this study is that the data were collected using an established SSI surveillance system (PREZIES) run by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, with both internal and external validation of the data reported by participating hospitals. In addition, established definitions used by the CDC and ECDC were employed, and no learning curve was needed for data reporting.

Another strength was the cluster‐randomization design. Compared with an RCT design, this approach provides relevant information regarding the expected outcome if a hospital were to switch to using a different preoperative antiseptic agent while maintaining all other aspects of their care as usual. The finding that chlorhexidine–alcohol provided similar results to iodine–alcohol for five different types of surgery, regardless of the participating hospital, illustrates the generalizability of the study results.

This study was, however, slightly underpowered. The power calculation suggested that 4000 operations in ten clusters were required, but 3665 surgeries in five clusters were included. This shortfall was due in part to the 2‐year study interval, which was chosen to minimize the influence of any changes over time in terms of SSI prevention or surgical care. A post hoc power calculation showed that the present study design has 78 per cent power.

Following up on the study by Darouiche and colleagues4, this study was designed as a superiority study, with the goal of testing whether chlorhexidine–alcohol is superior to iodine–alcohol in terms of preventing SSI. Another option would have been to test whether the two antiseptic agents were equally effective at preventing SSI (equivalence design) or whether one agent was not inferior to the other (non‐inferiority design). However, these study designs would have required an a priori determined equivalence (or non‐inferiority) margin, which generally necessitates larger sample sizes than those needed for a superiority study design16, 17. It is therefore not possible retrospectively to confirm equal effectiveness of the two disinfectants.

As the data in this study were limited by those provided to the Dutch National Nosocomial Surveillance Network, there were limited data on other relevant risk and preventive factors for SSI, and also on other possibly relevant outcomes such as length of hospital stay, mortality and readmission numbers.

Finally, this study did not include cost‐effectiveness as an endpoint, so no conclusions could be drawn with respect to financial considerations when selecting an antiseptic agent. In general, however, the cost of iodine is lower than that of chlorhexidine–alcohol18. Current Dutch guidelines permitting the use of a preoperative antiseptic alcohol solution containing either chlorhexidine or iodine are adequate for reducing the risk of SSI.

Supporting information

Table S1 Types of surgery included in the SKINFECT trial

Table S2 Summary of wound culture results

Table S3 S. aureus‐positive and E. coli‐positive wound cultures, stratified by surgery type

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by the Bontius Foundation of Leiden University Medical Centre.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. PREZIES (Dutch National Nosocomial Surveillance Network) . [Reference Numbers 2017 to 2014: Prevalence Research Hospitals] https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2018‐11/Referentiecijfers%20Prevalentie%20tm%202014_versie%206.1%20DEFINITIEF.pdf [accessed 7 May 2019].

- 2. Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control 1992; 20: 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. PREZIES . Protocol Module Postoperatieve Wondinfecties http://www.rivm.nl/Onderwerpen/P/PREZIES/Incidentieonderzoek_POWI/Protocol_module_Postoperatieve_wondinfecties/Protocol_en_Dataspecificaties_POWI_2017.org [accessed 21 October 2017].

- 4. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM et al. Chlorhexidine–alcohol versus povidone–iodine for surgical‐site antisepsis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charehbili A, van Gijn W, Liefers GJ, van de Velde C, Swijnenburg RJ. How evidence‐based is the transition from iodine to chlorhexidine for preoperative desinfection of the skin? Dutch J Surg 2013; 22: 34. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1999; 27: 97–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG; CONSORT Group . Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012; 345: e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koek MBG, Hopmans TEM, Soetens LC, Wille JC, Geerlings SE, Vos MC et al. Adhering to a national surgical care bundle reduces the risk of surgical site infections. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0184200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turner RM, White IR, Croudace T; PIP Study Group . Analysis of cluster randomized cross‐over trial data: a comparison of methods. Stat Med 2007; 26: 274–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, Martin S, Cahill AG, Odibo AO et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Privitera GP, Costa AL, Brusaferro S, Chirletti P, Crosasso P, Massimetti G et al. Skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus iodine for the prevention of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Infect Control 2017; 45: 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Broach RB, Paulson EC, Scott C, Mahmoud NN. Randomized controlled trial of two alcohol‐based preparations for surgical site antisepsis in colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2017; 266: 946–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Swenson BR, Hedrick TL, Metzger R, Bonatti H, Pruett TL, Sawyer RG. Effects of preoperative skin preparation on postoperative wound infection rates: a prospective study of 3 skin preparation protocols. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30: 964–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casey A, Itrakjy A, Birkett C, Clethro A, Bonser R, Graham T et al. A comparison of the efficacy of 70% v/v isopropyl alcohol with either 0.5% w/v or 2% w/v chlorhexidine gluconate for skin preparation before harvest of the long saphenous vein used in coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Infect Control 2015; 43: 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCann M, Fitzpatrick F, Mellotte G, Clarke M. Is 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol more effective at preventing central venous catheter‐related infections than routinely used chlorhexidine gluconate solutions: a pilot multicenter randomized trial (ISRCTN2657745)? Am J Infect Control 2016; 44: 948–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lesaffre E. Superiority, equivalence, and non‐inferiority trials. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2008; 66: 150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schumi J, Wittes JT. Through the looking glass: understanding non‐inferiority. Trials 2011; 12: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee I, Agarwal RK, Lee BY, Fishman NO, Umscheid CA. Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31: 1219–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Types of surgery included in the SKINFECT trial

Table S2 Summary of wound culture results

Table S3 S. aureus‐positive and E. coli‐positive wound cultures, stratified by surgery type