Abstract

Background

It is not known whether perioperative chemotherapy, compared with adjuvant chemotherapy alone, improves disease‐free survival (DFS) in patients with upfront resectable colorectal liver metastases (CLM). The aim of this study was to estimate the impact of neoadjuvant 5‐fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) on DFS in patients with upfront resectable CLM.

Methods

Consecutive patients who presented with up to five resectable CLM at two Japanese and two French centres in 2008–2015 were included in the study. Both French institutions favoured perioperative FOLFOX, whereas the two Japanese groups systematically preferred upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) and Cox regression multivariable models were used to adjust for confounding. The primary outcome was DFS.

Results

Some 300 patients were included: 151 received perioperative chemotherapy and 149 had upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy. The weighted 3‐year DFS rate was 33·5 per cent after perioperative chemotherapy compared with 27·1 per cent after upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy (hazard ratio (HR) 0·85, 95 per cent c.i. 0·62 to 1·16; P = 0·318). For the subgroup of 165 patients who received adjuvant FOLFOX successfully (for at least 3 months), the adjusted effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was not significant (HR 1·19, 0·74 to 1·90; P = 0·476). No significant effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was observed in multivariable regression analysis.

Conclusion

Compared with adjuvant chemotherapy, perioperative FOLFOX does not improve DFS in patients with resectable CLM, provided adjuvant chemotherapy is given successfully.

Abstract

Antecedentes

Se desconoce si la quimioterapia perioperatoria en comparación con la quimioterapia adyuvante sola mejora la supervivencia libre de enfermedad (disease‐free survival, DFS) en pacientes con metástasis hepáticas de origen colorrectal (colorectal liver metastases, CLM) resecables de inicio. El objetivo de este estudio fue estimar el impacto de la neoadyuvancia con 5‐fluorouracilo, leucovorina y oxaliplatino (FOLFOX) sobre la DFS en pacientes con CLM resecables desde el principio.

Métodos

Se incluyeron pacientes consecutivos que presentaban hasta cinco CLM resecables en dos centros japoneses y dos centros franceses entre 2008 a 2015. Ambas instituciones francesas favorecían FOLFOX perioperatorio, mientras que los dos grupos japoneses utilizaban sistemáticamente la cirugía de entrada y quimioterapia adyuvante. Se utilizaron la probabilidad inversa del tratamiento ponderado (Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting, IPTW) y el modelo multivariable de regresión de Cox para ajustar por factores de confusión. El resultado primario fue la DFS.

Resultados

Se incluyeron 300 pacientes (grupo de quimioterapia perioperatoria n = 151 y grupo de cirugía de entrada más quimioterapia adyuvante n = 149). La DFS a los 3 años ponderada fue del 33% después de quimioterapia perioperatoria versus 27% tras cirugía de entrada (cociente de riesgos instantáneos, hazard ratio HR: 0,85; i.c. del 95% (0,62‐1,16); P = 0,32). Cuando se consideró el subgrupo de pacientes que (n = 165) de manera efectiva (al menos 3 meses) recibieron FOLFOX adyuvante, el efecto ajustado de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante no fue significativo (HR: 1,19 (0,74‐1,90); P = 0,48). No se observó un efecto significativo de la quimioterapia neoadyuvante en el análisis de regresión multivariable.

Conclusión

En comparación con la quimioterapia adyuvante, el FOLFOX perioperatorio no mejora la DFS en CLM resecables siempre y cuando la quimioterapia adyuvante se administre de forma efectiva.

Introduction

Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of colorectal liver metastases (CLM) is currently recommended by European, Japanese and American guidelines, based on randomized trials and meta‐analysis1, 2, 3. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 40983 trial4 demonstrated that perioperative FOLFOX (5‐fluorouracil (5‐FU), leucovorin and oxaliplatin) improved disease‐free survival (DFS) compared with that found following surgery alone in patients with one to four resectable metastases. The authors did not, however, observe improved overall survival5.

This EORTC study did not resolve the question of whether perioperative chemotherapy decreases the risk of relapse, compared with adjuvant chemotherapy alone, in patients with upfront resectable CLM. All randomized studies that have attempted to compare perioperative FOLFOX with adjuvant FOLFOX alone have been abandoned because of recruitment issues6, 7, 8.

Estimating the effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients undergoing resection with subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy by matching them with patients having resection and adjuvant chemotherapy only may provide an indirect argument in favour of either strategy. This would be helpful for designing future studies. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of neoadjuvant FOLFOX by comparing perioperative FOLFOX with adjuvant chemotherapy alone in patients with upfront resectable CLM using international multicentre data.

Methods

This was a multicentre observational study. Data were retrieved from specifically developed databases from two French centres (Paul Brousse Hospital, Villejuif, a hepatobiliary and transplant centre, and Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, a tertiary referral cancer centre) and two Japanese centres (Hospital of Tokyo University, Tokyo, and University of Kumamoto Hospital, Kumamoto). The rationale for using these cohorts was the different oncological strategy for upfront resectable CLM in France and Japan. The two French centres favoured perioperative chemotherapy in the majority of patients, whereas the two Japanese centres systematically proposed upfront resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.

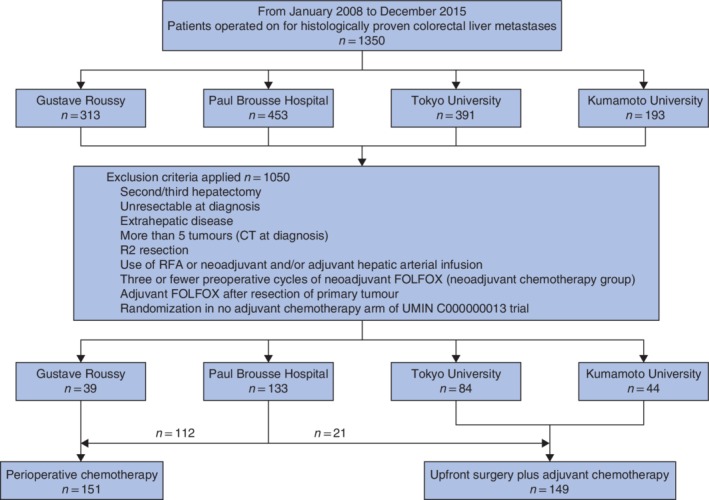

Of all consecutive patients who underwent a first hepatectomy for CLM between January 2008 and December 2015, patients with initially upfront resectable disease (up to 5 liver lesions on initial CT) who had macroscopic radical resections were included. Patients with extrahepatic disease, R2 resection, or in whom concomitant local ablative methods or hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy were used, and those who received fewer than four cycles of neoadjuvant FOLFOX were excluded from the study (Fig. 1). Patients randomized to the no adjuvant chemotherapy arm of the Japanese randomized trial (UMIN C000000013)9 and those who received adjuvant FOLFOX after resection of the primary tumour were also excluded.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the study population. RFA, radiofrequency ablation; FOLFOX, 5‐fluorouracil–leucovorin–oxaliplatin

The study design was discussed at all four centres and Institutional Review Board approval was not considered necessary.

Outcome

The endpoint of this study was DFS. The event of interest was either death or recurrence, regardless of location. As management of recurrence and chemotherapy regimens in second or third lines differed between Japan and France, overall survival was not considered in this study. Owing to the retrospective design of this study, all patients who had progressive disease or died during preoperative chemotherapy and never had a resection could not be analysed. Survival time was therefore calculated from the date of resection. Choosing the date of CLM diagnosis would have artificially increased the survival time of the group that received perioperative chemotherapy.

Upfront surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy group

This group included all Japanese patients and French patients who did not receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy was mainly FOLFOX (FOLFOX4 or FOLFOX6 or modified FOLFOX6) for a minimum duration of 3 months (6 cycles)10, although the recommended duration was 6 months2. Other regimens (XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin), FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5‐FU and irinotecan), LV5FU2 (leucovorin and 5‐FU), capecitabine, UFT (uracil and tegafur) and leucovorin) were given, according to the general condition of the patient, tolerance to oxaliplatin or preferences of the medical oncologist. Successful administration of adjuvant chemotherapy was defined as at least 3 months' treatment.

Perioperative chemotherapy group

The perioperative group consisted of patients who received at least four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The standard was to propose four to six cycles of FOLFOX4 before surgery11. Progression while receiving chemotherapy was considered a contraindication to resection in the majority of patients, and a second line was usually proposed. When metastases disappeared after preoperative chemotherapy, the general policy was to remove the part initially affected by the tumour, except for deep lesions not visible during surgery. The choice of adjuvant therapy was mainly FOLFOX4 in all centres for 3 months. Other regimens were considered if necessary.

Definition of resectability

Upfront resectability was defined as the possibility to achieve complete macroscopic resection with an estimated future remnant liver volume of at least 30 per cent of the standard liver volume12 (Japan) or 0·5 per cent of bodyweight13 (France). CLM were considered initially not resectable when two‐stage hepatectomy and/or portal vein embolization was necessary.

Preoperative evaluation

In all centres systematic preoperative MRI was used increasingly during the study period. PET was indicated in patients suspected of having extrahepatic disease on conventional imaging, but was not done systematically during the study interval.

Surgical technique

Technical aspects have been described previously14, 15, 16, 17. A parenchyma‐sparing policy was preferred at all centres. The objective of resection was to achieve microscopically complete resection. Resectability was decided after volumetric evaluation of future remnant liver. Intraoperative ultrasound imaging was used routinely by all centres. The pedicle clamping technique was commonly used during transection. A laparoscopic approach was seldom chosen.

Follow‐up

The follow‐up modalities of each centre have been published in detail previously14, 15, 17, 18. Briefly, thoracoabdominal CT and blood tests were performed every 3–4 months for the first 2 years after hepatectomy, and then every 6 months.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon signed rank test. To adjust for confounders, two methods of propensity scoring were used successively. The propensity score was calculated by including confounding variables, which were selected to obtain the best compromise between the quality of balance and the number of variables. Increasing the number of co‐variables makes it more difficult to obtain a correct balance of the weighted sample, especially when the cohort size is small. Priority was given to variables with both prognostic impact (based on the literature)19, 20 and significant differences of distribution in the unweighted cohort. Finally, five variables were selected: age, lymph node status of the primary tumour, synchronous versus metachronous metastases, maximum tumour size, and number of tumours at diagnosis based on CT.

First, the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method was applied. Although popular, propensity score‐based matching is impaired by loss of information resulting from the impossibility of finding a matched pair for every patient in the experimental group. Therefore, when experimental and control groups are of similar size, IPTW should be preferred21. In IPTW, every patient is weighted by the inverse of the propensity score. This creates a pseudopopulation (weighted sample), with unchanged size, but in which patients have different weights. To avoid imbalance due to patients with extreme weights, all extreme weights outside the first and 99th percentiles were truncated to the value of the first and 99th percentiles respectively, as proposed previously22. With IPTW, the outcome of the whole cohort is estimated for each treatment by extrapolating the observed result in treated patients (perioperative chemotherapy group) to that in the control group (upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy group) with similar propensity scores.

To detect misspecification of the model, means and prevalence of co‐variables were compared using absolute standardized differences and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test statistic, as recommended23, 24. The average treatment effect of neoadjuvant therapy was evaluated by weighted Cox regression model in the weighted sample. The bootstrap technique was used to estimate confidence intervals25.

A Cox proportional hazard model was then used. The propensity score was used to adjust for the effect of neoadjuvant FOLFOX on DFS. The variable neoadjuvant FOLFOX and the propensity score were forced into the model. The assumption of proportionality was verified with the Schoenfeld residuals. P < 0·050 defined statistical significance.

Results

Some 300 patients were included (Fig. 1), 151 in the perioperative chemotherapy group and 149 in the adjuvant chemotherapy group. Median follow‐up was 44 months. The overall 90‐day mortality rate after hepatectomy was 0·3 per cent (1 patient). Median DFS was 24 months, with a 3‐year DFS rate of 37·2 per cent. KRAS (exons 2 and 3) and BRAF (exon 15) statuses were available in 159 patients (53·0 per cent). Among tested tumours, BRAF mutation was not detected.

Patient and tumour characteristics

Patients in the perioperative chemotherapy group had a higher number of tumours, larger maximum tumour diameter and more synchronous disease (Table 1). Major hepatectomies were more often performed. Adjuvant chemotherapy was also different, with a higher proportion of patients treated by FOLFOX or FOLFIRI regimen in the perioperative group. The proportions of patients who finally did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy were not significantly different between the two groups. The proportion of patients with a KRAS mutation was not significantly different either.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for the two groups

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 149) | Perioperative chemotherapy (n = 151) | P ¶ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 63·0 (25·0–88·0) | 61·7 (29·1–88·6) | 0·321# |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 102 : 47 | 88 : 63 | 0·087 |

| Primary tumour | |||

| Location | 0·072 | ||

| Right transverse colon | 31 of 148 (20·9) | 44 (29·5) | |

| Left colon | 87 of 148 (58·8) | 87 (58·4) | |

| Rectum | 30 of 148 (20·3) | 18 (12·1) | |

| Stage T3–4 | 94 of 148 (63·5) | 128 of 143 (89·5) | < 0·001 |

| Node‐positive | 94 (63·1) | 107 (70·9) | 0·191 |

| Disease history | < 0·001 | ||

| Synchronous | 67 (45·0) | 109 (72·2) | |

| Metachronous without previous chemotherapy | 39 (26·2) | 5 (3·3) | |

| Metachronous with previous chemotherapy | 43 (28·9) | 37 (24·5) | |

| Hepatic disease | |||

| Maximum tumour size (mm)* | 25 (3–200) | 30 (1–100) | 0·005# |

| No. of tumours* | 1 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | < 0·001# |

| CEA level > 5 ng/ml at diagnosis | 33 (22·1) | 36 (23·8) | 0·833 |

| Neoadjuvant FOLFOX† | |||

| Progression (RECIST) | n.a. | 13 (8·6) | |

| No. of cycles* | n.a. | 6 (3–11) | |

| Surgical procedures and outcomes | |||

| Order of resections | 0·016 | ||

| Primary tumour resection first | 103 (69·1) | 123 (81·5) | |

| Simultaneous liver and primary resection | 45 (30·2) | 26 (17·2) | |

| Liver first | 1 (0·7) | 2 (1·3) | |

| Major hepatectomy (≥ 3 segments) | 9 (6·0) | 41 (27·2) | < 0·001 |

| Dindo–Clavien grade ≥ III | 19 (12·8) | 15 (9·9) | 0·557 |

| Positive resection margins | 12 of 146 (8·2) | 53 of 143 (37·1) | < 0·001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| Regimen | < 0·001 | ||

| None | 36 (24·2) | 43 (28·5) | |

| FOLFOX (± FOLFIRI) | 65 (43·6) | 100 (66·2) | |

| UFT or XELOX | 6 (4·0) | 6 (4·0) | |

| Capecitabine | 42 (28·2) | 2 (1·3) | |

| Postoperative bevacizumab or cetuximab | 3 (2·0) | 22 (14·6) | < 0·001 |

| No. of postoperative cycles*, ‡ | 6 (2–15) | 6 (0–16) | 0·444# |

| Tumour genotype | |||

| KRAS/BRAF mutation§ | 34 of 75 (45) | 35 of 84 (42) | 0·760 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

FOLFOX (5‐fluorouracil–leucovorin–oxaliplatin) includes FOLFOX4, FOLFOX6 and modified FOLFOX6;

for patients treated by intravenous chemotherapy;

KRAS exons 2 and 3, and BRAF exon 15. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (guidelines); n.a., not applicable; FOLFIRI, folinic acid–5‐fluorouracil–irinotecan; UFT, tegafur–uracil; XELOX, capecitabine–oxaliplatin.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

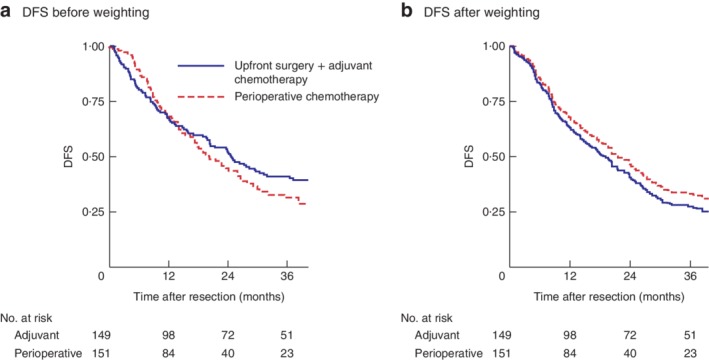

Survival

There was no difference in DFS: median DFS 20 (range 17–27) months and 3‐year DFS rate 31·4 per cent for the perioperative chemotherapy group versus 25 (20–32) months and 41·5 per cent respectively for the adjuvant chemotherapy group (P = 0·394) (Fig. 2 a).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease‐free survival for the whole cohort. Disease‐free survival (DFS) in upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy and perioperative chemotherapy groups a before and b after weighting. a P = 0·394, b P = 0·318 (Cox model)

The diagnostic balance after weighting is shown in Table S1 (supporting information). Weighted cumulative survival probabilities were similar (3‐year DFS rate of 33·5 per cent in the perioperative chemotherapy group versus 27·1 per cent in the adjuvant chemotherapy group). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed no association with DFS (hazard ratio (HR) 0·85, 95 per cent c.i. 0·62 to 1·16; P = 0·318). Median DFS after IPTW was 21 (18–27) months in the perioperative group and 19 (14–24) months in the upfront surgery plus adjuvant therapy group (Fig. 2 b).

There was no significant difference in overall survival before and after weighting (Fig. S1, supporting information).

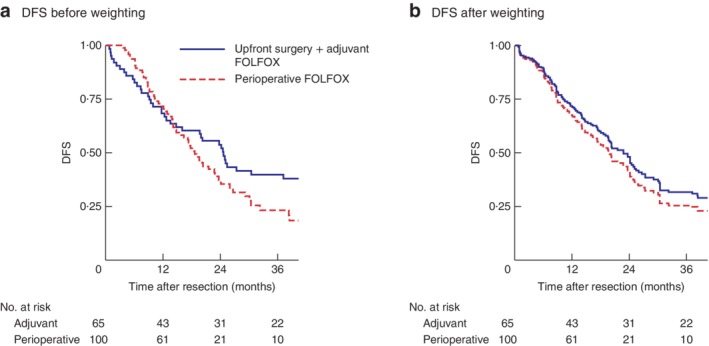

Subgroup of patients who had successful adjuvant FOLFOX treatment

This subgroup included 165 patients (100 in the perioperative chemotherapy group and 65 in the adjuvant chemotherapy group). Baseline comparisons before adjustment are shown in Table 2, Kaplan–Meier DFS curves in Fig. 3 a (median DFS 21 (18–27) versus 25 (16–49) months, and 3‐year DFS rate 23 versus 40 per cent, respectively), and diagnostic balance after weighting in Table S2 (supporting information).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients who received adjuvant FOLFOX

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 65) | Perioperative chemotherapy (n = 100) | P ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 63·6 (25·0–80·6) | 60·9 (32·2–88·6) | 0·321§ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 47 : 18 | 62 : 38 | 0·231 |

| Primary tumour | |||

| Location | 0·075 | ||

| Right transverse colon | 13 of 64 (20) | 30 of 98 (31) | |

| Left colon | 36 of 64 (56) | 57 of 98 (58) | |

| Rectum | 15 of 64 (23) | 11 of 98 (11) | |

| Stage T3–4 | 32 (49) | 86 of 94 (91) | < 0·001 |

| Node‐positive | 43 (66) | 65 (65) | > 0·999 |

| Disease history | < 0·001 | ||

| Synchronous | 32 (49) | 77 (77) | |

| Metachronous without previous chemotherapy | 13 (20) | 4 (4) | |

| Metachronous with previous chemotherapy | 20 (31) | 19 (19) | |

| Hepatic disease | |||

| Maximum tumour size (mm)* | 25 (3–100) | 30 (1–100) | 0·042§ |

| No. of tumours* | 1 (1–5) | 2 (1–5) | 0·009§ |

| CEA level > 5 ng/ml at diagnosis | 17 (26) | 30 (30) | 0·720 |

| Surgical procedures and outcomes | |||

| Order of resections | 0·239 | ||

| Primary tumour resection first | 43 (66) | 77 (77) | |

| Simultaneous liver and primary resection | 21 (32) | 21 (21) | |

| Liver first | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Major hepatectomy (≥ 3 segments) | 7 (11) | 25 (25) | 0·040 |

| Dindo–Clavien grade ≥ III | 6 (9) | 9 (9) | > 0·999 |

| Positive resection margins | 8 of 63 (13) | 33 of 96 (34) | 0·004 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| Postoperative bevacizumab or cetuximab | 3 (5) | 18 (18) | 0·023 |

| Tumour genotype | |||

| KRAS/BRAF mutation† | 14 of 31 (45) | 21 of 53 (40) | 0·789 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

KRAS exons 2 and 3, and BRAF exon 15. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test, except

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease‐free survival in patients who had successful adjuvant FOLFOX treatment. Disease‐free survival (DFS) in upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy and perioperative chemotherapy groups a before and b after weighting. FOLFOX, 5‐fluorouracil–leucovorin–oxaliplatin. a P = 0·170, b P = 0·476 (Cox model)

No statistically significant differences in weighted DFS were seen after neoadjuvant compared with adjuvant chemotherapy (3‐year DFS rate 24·8 versus 31·4 per cent respectively; median DFS 20 (15–25) versus 23 (17–30) months respectively). The effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on DFS was not significant (HR 1·19, 95 per cent c.i. 0·74 to 1·90; P = 0·476) (Fig. 3 b).

Adjusted effect of neoadjuvant FOLFOX

Univariable analysis of DFS is shown in Table S3 (supporting information). The multivariable Cox regression model, including neoadjuvant FOLFOX and the propensity score, found that the adjusted effect of neoadjuvant FOLFOX on DFS was not significant (HR 0·88, 95 per cent c.i. 0·64 to 1·22; P = 0·455) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox analysis of disease‐free survival

| Hazard ratio | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant FOLFOX | 0·88 (0·64, 1·22) | 0·455 |

| Propensity score | 8·84 (3·29, 23·77) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. FOLFOX, 5‐fluorouracil–leucovorin–oxaliplatin.

Discussion

All randomized studies investigating perioperative chemotherapy versus adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with upfront resectable CLM have failed owing to recruitment issues. To gain more insight into this topic, this multicentre retrospective comparison between the two strategies was performed by including patients treated in France and Japan, distinct in their approach to resectable patients. Neoadjuvant FOLFOX did not improve DFS compared with upfront surgery followed by chemotherapy in patients with resectable CLM. These results suggest that upfront surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy could be considered in patients with easily resectable disease, those with a high probability of receiving adjuvant treatment.

Upfront surgery is a valid option, provided that optimal adjuvant chemotherapy is administered effectively. This is of major importance as proponents of the neoadjuvant chemotherapy approach propose that giving chemotherapy before resection offers the best chance for a patient to receive chemotherapy successfully5, 26.

In the present study, 24·2 per cent of patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy after upfront surgery, mainly due to severe postoperative morbidity or mediocre general status. This suggests that upfront surgery should not be proposed to patients at high risk of postoperative complications or those requiring complex hepatectomies.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy has already been explored as a treatment option in patients with resectable CLM. A review of literature27 and a meta‐analysis28 concluded there was no clear benefit for neoadjuvant treatment when liver disease was upfront resectable. This analysis, however, was based mainly on single‐centre studies focusing on the toxicity of preoperative chemotherapy and early outcomes. Several studies29, 30, 31 have shown no association of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with survival benefit in univariable or multivariable analysis. Similar findings were reported in patients with low oncological risk32, 33. All of these were single‐centre studies. Preoperative chemotherapy was indicated in patients with borderline resectable disease, which makes it difficult to compare the two strategies. A study based on the LiverMetSurvey registry did not observe any survival benefit after preoperative chemotherapy in resectable patients34. Although many groups were involved, this study was limited by the heterogeneity in the definition of resectability or in surgical expertise among centres.

In the present study, differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups before weighting may be surprising, but reflect differences between French and Japanese healthcare systems. In Japan, most liver resections are performed by certified hepatobiliary surgeons, whereas in France general surgeons commonly perform limited liver resections. As a result, French patients with easily resectable disease are rarely managed in specialized hepatobiliary centres.

It could be argued that lack of power and more advanced disease in the perioperative group explain the absence of difference between the two strategies. As power calculation a posteriori is known to be misleading35, 36, 37, no post hoc power was calculated. Moreover, neither of the two methods (IPTW and Cox model) used for adjustment found any difference. The calculated increase of 6 per cent in 3‐year DFS rates in the perioperative chemotherapy group after weighting may be clinically relevant. This analysis, however, was based on resected patients only. As a result, patients who never had a resection owing to disease progression while on chemotherapy were excluded, giving an advantage to the perioperative group in terms of tumour biology. Moreover, the subgroup analysis of patients who received adjuvant FOLFOX successfully suggests that neoadjuvant chemotherapy has no effect when optimal adjuvant chemotherapy is administered effectively. Thus, if a true difference exists, the expected effect may be lower than the increase in DFS rate of 6 per cent and a clinically relevant effect is unlikely.

Over the 8 years of the present study, only 300 patients from four high‐volume centres met the inclusion criteria. This represents 22·2 per cent of the total number of patients who had surgery for CLM. This point is important for those willing to undertake a future trial, as it clearly indicates issues for achieving the planned recruitment and underlines the need to involve a large number of centres.

This study has several limitations. Beyond racial differences between groups and the possible impact on prognosis, differences in healthcare systems and in the preoperative workup (MRI, PET–CT) may also influence outcomes and limit comparability. Although four centres were involved, the size of the whole cohort remained limited. The retrospective design of this study precluded any true intention‐to‐treat analysis and determination of progression‐free survival. The authors acknowledge that DFS is an imperfect endpoint. To limit bias, strict criteria for patient selection were applied to the study population. Surgical management across centres was comparable, including surgical volume, intraoperative ultrasound imaging and parenchyma‐sparing policy. Two methods of adjustment were used to secure the present results, which affect the daily practice of treating resectable colorectal liver metastases.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival in the whole cohort before (S1A) and after weighting (S1B)

Table S1 Diagnostics balance before and after weighting (whole cohort)

Table S2 Diagnostics balance before and after weighting (subgroup of patients who effectively received adjuvant FOLFOX)

Table S3 Univariable analysis of disease‐free survival

Acknowledgements

M.‐A.A. received a research grant from the Association Française de Chirurgie and the Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Paris.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 1386–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watanabe T, Muro K, Ajioka Y, Hashiguchi Y, Ito Y, Saito Y et al.; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum . Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2016 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2018; 23: 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) . Colon Cancer https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf [accessed 22 April 2019].

- 4. Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P et al.; EORTC Gastro‐Intestinal Tract Cancer Group; Cancer Research UK; Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen und‐tumoren in der Chirurgischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Onkologie (ALM‐CAO); Australasian Gastro‐Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG); Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD) . Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 1007–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P et al.; EORTC Gastro‐Intestinal Tract Cancer Group; Cancer Research UK; Arbeitsgruppe Lebermetastasen und–tumoren in der Chirurgischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Onkologie (ALM‐CAO); Australasian Gastro‐Intestinal Trials Group (AGITG); Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD) . Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long‐term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. ClinicalTrials.gov. Treatment Regimens for Patients with Resectable Liver Metastases (PANTER Study) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01266187 [accessed 22 April 2019].

- 7. ClinicalTrials.gov. Compare FOFLOX4 in Preoperative and Postoperative and Postoperative in Resectable Liver Metastasis Colorectal Cancer (MCC) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01035385 [accessed 22 April 2019].

- 8. UMIN Clinical Trials Registry . Randomized Phase III Trial of Surgery Followed by mFOLFOX6 as Adjuvant Chemotherapy Versus Peri‐operative mFOLFOX6 Plus Cetuximab for KRAS Wild Type Resectable Liver Metastases of Colorectal Cancer. UMIN000007787 https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi‐open‐bin/icdr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000009175 [accessed 22 April 2019].

- 9. Hasegawa K, Saiura A, Takayama T, Miyagawa S, Yamamoto J, Ijichi M et al. Adjuvant oral uracil‐tegafur with leucovorin for colorectal cancer liver metastases: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0162400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sakamoto Y, Beppu T, Miyamoto Y, Okabe H, Ida S, Imai K et al. Feasibility and short‐term outcome of adjuvant FOLFOX after resection of colorectal liver metastases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2013; 20: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Société Nationale Française de Gastro‐Entérologie . Cancer Colorectal Métastatique https://www.snfge.org/content/4‐cancer‐colorectal‐metastatique [accessed 22 April 2019].

- 12. Urata K, Kawasaki S, Matsunami H, Hashikura Y, Ikegami T, Ishizone S et al. Calculation of child and adult standard liver volume for liver transplantation. Hepatology 1995; 21: 1317–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Truant S, Oberlin O, Sergent G, Lebuffe G, Gambiez L, Ernst O et al. Remnant liver volume to body weight ratio > or = 0.5%: a new cut‐off to estimate postoperative risks after extended resection in noncirrhotic liver. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204: 22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goéré D, Benhaim L, Bonnet S, Malka D, Faron M, Elias D et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of colorectal liver metastases in patients at high risk of hepatic recurrence: a comparative study between hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin and modern systemic chemotherapy. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Flores E, Azoulay D, Castaing D, Adam R. R1 resection by necessity for colorectal liver metastases: is it still a contraindication to surgery? Ann Surg 2008; 248: 626–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oba M, Hasegawa K, Matsuyama Y, Shindoh J, Mise Y, Aoki T et al. Discrepancy between recurrence‐free survival and overall survival in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases: a potential surrogate endpoint for time to surgical failure. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 1817–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Beppu T, Hayashi N, Masuda T, Komori H, Horino K, Hayashi H et al. FOLFOX enables high resectability and excellent prognosis for initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Anticancer Res 2010; 30: 1015–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elias D, Liberale G, Vernerey D, Pocard M, Ducreux M, Boige V et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic colorectal metastases: when resectable, their localization does not matter, but their total number has a prognostic effect. Ann Surg Oncol 2005; 12: 900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med 2007; 26: 734–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hallet J, Sa Cunha A, Adam R, Goéré D, Bachellier P, Azoulay D et al.; French Colorectal Liver Metastases Working Group, Association Française de Chirurgie (AFC) . Factors influencing recurrence following initial hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 2016; 103: 1366–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011; 46: 399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015; 34: 3661–3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity‐score matched samples. Stat Med 2009; 28: 3083–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Austin PC. Variance estimation when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) with survival analysis. Stat Med 2016; 35: 5642–5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benoist S, Nordlinger B. The role of preoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16: 2385–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehmann K, Rickenbacher A, Weber A, Pestalozzi BC, Clavien PA. Chemotherapy before liver resection of colorectal metastases: friend or foe? Ann Surg 2012; 255: 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robinson SM, Wilson CH, Burt AD, Manas DM, White SA. Chemotherapy‐associated liver injury in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 4287–4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Araujo R, Gonen M, Allen P, Blumgart L, DeMatteo R, Fong Y et al. Comparison between perioperative and postoperative chemotherapy after potentially curative hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 4312–4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faron M, Chirica M, Tranchard H, Balladur P, de Gramont A, Afchain P et al. Impact of preoperative and postoperative FOLFOX chemotherapies in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014; 45: 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lubezky N, Geva R, Shmueli E, Nakache R, Klausner JM, Figer A et al. Is there a survival benefit to neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy, combined with surgery for resectable colorectal liver metastases? World J Surg 2009; 33: 1028–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhu D, Zhong Y, Wei Y, Ye L, Lin Q, Ren L et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. PLoS One 2014; 9: >e86543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ayez N, van der Stok EP, Grünhagen DJ, Rothbarth J, van Meerten E, Eggermont AM et al. The use of neo‐adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases: clinical risk score as possible discriminator. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015; 41: 859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bonney GK, Coldham C, Adam R, Kaiser G, Barroso E, Capussotti L et al.; LiverMetSurvey International Registry Working Group . Role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastasis; an international multi‐center data analysis using LiverMetSurvey. J Surg Oncol 2015; 111: 716–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goodman SN, Berlin JA. The use of predicted confidence intervals when planning experiments and the misuse of power when interpreting results. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121: 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smith AH, Bates MN. Confidence limit analyses should replace power calculations in the interpretation of epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 1992; 3: 449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: the pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat 2001; 55: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival in the whole cohort before (S1A) and after weighting (S1B)

Table S1 Diagnostics balance before and after weighting (whole cohort)

Table S2 Diagnostics balance before and after weighting (subgroup of patients who effectively received adjuvant FOLFOX)

Table S3 Univariable analysis of disease‐free survival