Abstract

Many G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are organized as dynamic macromolecular complexes in human cells. Unraveling the structural determinants of unique GPCR complexes may identify unique protein:protein interfaces to be exploited for drug development. We previously reported α1D-adrenergic receptors (α1D-ARs) – key regulators of cardiovascular and central nervous system function – form homodimeric, modular PDZ protein complexes with cell-type specificity. Towards mapping α1D-AR complex architecture, biolayer interferometry (BLI) revealed the α1D-AR C-terminal PDZ ligand selectively binds the PDZ protein scribble (SCRIB) with >8x higher affinity than known interactors syntrophin, CASK and DLG1. Complementary in situ and in vitro assays revealed SCRIB PDZ domains 1 and 4 to be high affinity α1D-AR PDZ ligand interaction sites. SNAP-GST pull-down assays demonstrate SCRIB binds multiple α1D-AR PDZ ligands via a co-operative mechanism. Structure-function analyses pinpoint R1110PDZ4 as a unique, critical residue dictating SCRIB:α1D-AR binding specificity. The crystal structure of SCRIB PDZ4 R1110G predicts spatial shifts in the SCRIB PDZ4 carboxylate binding loop dictate α1D-AR binding specificity. Thus, the findings herein identify SCRIB PDZ domains 1 and 4 as high affinity α1D-AR interaction sites, and potential drug targets to treat diseases associated with aberrant α1D-AR signaling.

Subject terms: Supramolecular assembly, G protein-coupled receptors

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) account for ~4% of the human genome and are targets for ~30% of FDA approved drugs1. Typically these medications compete with endogenous ligands for orthosteric binding sites, hindering drug selectivity due to the similarity of binding pockets amongst closely related GPCRs. Thus, there is great interest in identifying novel sites to modulate GPCR signaling. To this end, a growing body of research has focused on identifying and characterizing the functional roles of GPCR interacting proteins. Two prominent examples are the β-arrestins2; and PDZ (PSD95/Dlg/ZO-1) domain containing proteins, which typically interact with C-terminal PDZ ligands3,4. Since the discovery that rhodopsin interacts with inaD5 and β2-adrenergic receptor (AR) with NHERF6, significant effort has been put forth to understand GPCR:PDZ protein interactions and their potential as drug targets7–11. For example, pharmacological disruption of the nNOS:NOS1AP:PSD95:NMDAR protein complex provides an alternative approach to NMDAR antagonists for treating neuropathic pain12–14 and neuronal excitotoxicity15, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of targeting PDZ protein interactions to selectively modulate membrane protein function.

Of the three α1-AR GPCR subtypes (α1A, α1B, α1D) that respond to the endogenous catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine, only the α1D-AR subtype contains a C-terminal Type I PDZ ligand. Yeast 2-hybrid16 and tandem-affinity purification/mass spectrometry17 screens initially revealed the α1D-AR PDZ ligand interacts with the syntrophin family of PDZ domain containing proteins. Syntrophins enhance α1D-AR function via recruiting the Dystrophin Associated Protein Complex (DAPC) and signaling effectors, α-catulin, liprin and phospholipase-Cβ18. Improved proteomic analyses subsequently revealed that, in addition to syntrophins, α1D-ARs also interact with the multi-PDZ domain containing protein scribble (SCRIB); and that α1D-ARs are expressed as modular homodimers, with one α1D-AR protomer bound to SCRIB, the other to syntrophin, in all human cell lines examined to date19. Strikingly, the α1D-AR:SCRIB:syntrophin complex is highly unique – no other GPCRs containing C-terminal Type I PDZ ligands have been shown to interact with both SCRIB and syntrophins20. Without significant expression of necessary PDZ proteins, α1D-ARs are retained intracellularly and produce weak functional responses21–23, suggesting this protein:protein interaction site has the potential for pharmacological modulation. Indeed, numerous diseases are associated with aberrant α1-AR function, including hypertension24, benign prostate hypertrophy25, bladder obstruction26, schizophrenia27, and post-traumatic stress disorder28,29. Unfortunately, deleterious side effects (i.e. orthostatic hypotension, reflex tachycardia) are frequently observed with chronic use of non-selective α1-AR antagonists. For example, the doxazosin portion of the ALLHAT anti-hypertensive study was prematurely halted due to increased morbidity30. Thus, selectively targeting the α1D-AR:SCRIB:syntrophin complex may provide therapeutic benefit, minus the toxicities associated with non-selective α1-AR ligands.

Herein, we employed a combination of biophysical, biochemical and cell-based approaches to acquire structural insights into the α1D-AR:PDZ protein complex. Together, our data implicate SCRIB PDZ domains 1 and 4 as the primary anchor sites for the α1D-AR. We further highlight differences in α1D-AR:PDZ1 versus α1D-AR:PDZ4 interactions by identifying unique residues in PDZ4 that are critical for α1D-AR binding.

Results and Discussion

α1D-AR preferentially binds SCRIB PDZ domains 1 and 4

We previously discovered the α1D-AR interacts with multiple PDZ proteins with cell-type specificity: scribble (SCRIB), α1-syntrophin (SNTA), human discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 1 (DLG1), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase (CASK)19. With the goal of elucidating the molecular architecture of this unique, modular GPCR:PDZ protein complex, we employed BioLayer Interferometry (BLI) to quantify equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for α1D-AR PDZ ligand:PDZ protein interactions. cDNAs encoding for the PDZ domains of these proteins were subcloned into a modified pGEX vector (pCOOL), expressed in E. coli and purified. Immobilized biotin-labeled peptides containing the distal 20 amino acids of α1D-AR (α1D-CT) were incubated with purified PDZ proteins and subjected to BLI analysis (Fig. 1A). We first compared α1D-CT binding to SCRIB and α1-syntrophin (SNTA), as α1D-ARs were found to interact with both PDZ proteins in all human cell lines examined19. Remarkably, α1D-CT bound SCRIB (KD = 70 ± 20 nM; Fig. 1B) with ~8 higher affinity than SNTA (KD = 0.56 ± 0.14 μM; Fig. 1C). DLG1 (KD = 0.79 ± 0.21 μM; Fig. 1D) and CASK (KD = 1.15 ± 0.21 μM; Fig. 1E), similar to SNTA, bind α1D-CT with lower affinity than SCRIB. MPP7, a known interactor of DLG1 and CASK31, displayed negligible α1D-CT binding (Fig. 1F). The combined rank order of affinity for α1D-CT interactions with known PDZ proteins is SCRIB» > SNTA > DLG1 > CASK» > MPP7 (Fig. 1G). α1D-CT:SCRIB binding affinity was validated by performing reverse BLI on GST-SCRIB probes incubated in serial dilutions of biotinylated α1D-CT (KD = 76 ± 20 nM; Fig. 1H).

Figure 1.

In situ affinity determination of α1D-adrenergic receptor C-terminal PDZ ligand:PDZ protein interactions. (A) Real-time biolayer interferometry (BLI) association/dissociation curve measuring binding of α1D C-terminus (α1D-CT) to purified scribble (SCRIB). Biotin-labeled α1D-CT was immobilized to streptavidin probes. Indicated concentrations of SCRIB were used as analytes. (Bio. = Biocytin, Diss. = Dissociation). (B–F) Quantified BLI binding data for biotin labeled α1D-CT binding to (B) SCRIB, (C) α1-syntrophin (SNTA), (D) human discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 1 (DLG1), (E) calcium/calmodulin dependent serine protein kinase (CASK), and (F) membrane palmitoylated protein 7 (MPP7). (G) Comparative analysis of BLI concentration-response curves for α1D-CT:PDZ protein association binding. (H) Reverse BLI assay of purified α1D-CT (analyte) bound to immobilized biotin-labeled SCRIB (probe). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

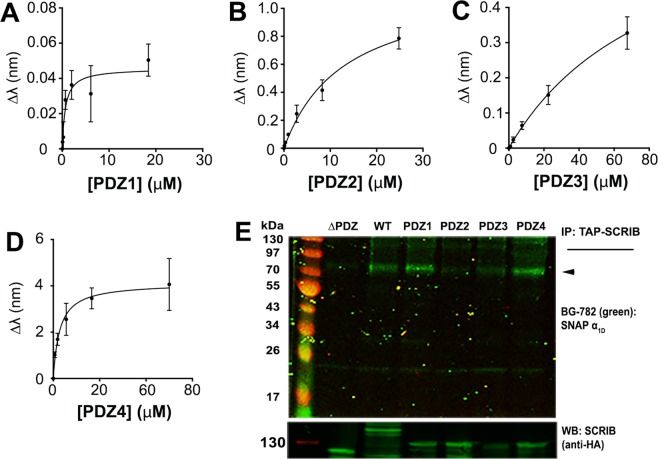

A defining structural characteristic of SCRIB includes the presence of four clustered PDZ domains in the C-terminal portion of the polypeptide. Thus, we questioned if α1D-CT selectively associates with targeted PDZ domains on SCRIB. Individual PDZ domains were purified as GST-fusion proteins from E. coli and subjected to BLI analysis. SCRIB PDZ1 (KD = 1.93 ± 0.49 μM; Fig. 2A) and SCRIB PDZ4 (KD = 1.14 ± 0.23 μM; Fig. 2D) bind α1D-CT with the highest affinity, followed by SCRIB PDZ2 (KD = 14.9 ± 5.44 μM; Fig. 2B) and SCRIB PDZ3 (KD = 44.16 ± 13.52 μM; Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

In situ and in vitro analysis of α1D-adrenergic receptor C-terminal PDZ ligand:SCRIB single PDZ domain interactions. (A–D) Biolayer interferometry (BLI) analyses of immobilized biotin-labeled α1D-CT binding to (A) SCRIB PDZ domain 1 (PDZ1), (B) SCRIB PDZ domain 2 (PDZ2), (C) SCRIB PDZ domain 3 (PDZ3) and (D) SCRIB PDZ domain 4. BLI data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. (E) Top panel, PAGE NIR of BG-782 labeled SNAP-α1D-AR co-immunoprecipitated with TAP-SCRIB containing all 4 PDZ domains (WT), PDZ domain 1 (PDZ1), 2 (PDZ2), 3 (PDZ3) or 4 (PDZ4), or no PDZ domains (ΔPDZ) from HEK293 cell lysates. Bottom panel, Anti-HA western blot of upper gel for listed TAP-SCRIB constructs. ◄ indicates SNAP-α1D-AR monomer band.

Next, SCRIB containing all 4 PDZ domains (WT), SCRIB mutants containing single-PDZ domains (PDZ1, PDZ2, PDZ3, PDZ4), and SCRIB lacking all 4 PDZ domains (ΔPDZ) were subcloned into the pGlue vector to add N-terminal tandem affinity purification (TAP) epitope tags. HEK293 cells were transfected with TAP-SCRIB constructs and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting to verify expression (Suppl. Fig. 1). Next, constructs were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells stably expressing SNAP-α1D-AR. Cell lysates were affinity purified with streptavidin beads. Samples were labeled with BG-782 to detect SNAP-α1D-AR and imaged with PAGE NIR. As shown in Fig. 2E, SNAP-α1D-AR co-immunoprecipitated robustly with SCRIB WT, PDZ1, PDZ4, and to a lesser extent, with PDZ3. As expected SCRIB ΔPDZ produced no significant SNAP-α1D-AR binding. Thus, in vitro analysis of α1D-AR:SCRIB interactions concurs with prior in situ BLI results.

Taken together, these data implicate SCRIB PDZ1 and PDZ4 as the central scaffolds of the α1D-AR complex. Based on our discovery that CASK and DLG1 bind with relatively low affinity to the α1D-AR PDZ ligand, and that previous studies have reported SCRIB can interact with additional PDZ proteins (reviewed in32), we suspect CASK and DLG1 are recruited to the α1D-AR complex indirectly by SCRIB. For example, DLG1 can be indirectly recruited to SCRIB via GUKH, which interacts with SCRIB PDZ2 in Drosophila synaptic boutons33, or LGL − a known interactor with both DLG1 and SCRIB34,35. Additionally, DLG1, CASK, and LIN-7A are expressed as a tripartite complex in vitro and in vivo36–38, suggesting DLG1 may be recruiting CASK and LIN-7A to the α1D-AR complex via indirect interactions with SCRIB.

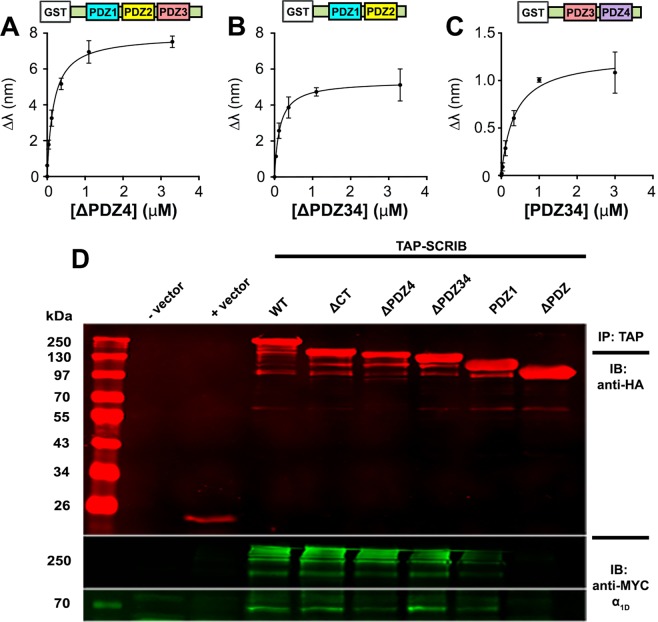

α1D-CT:SCRIB binding is co-operative

A key finding from BLI studies was the notable difference in α1D-CT binding affinity for SCRIB containing all 4 PDZ domains (70 nM) relative to each individual SCRIB PDZ domain (1.14–44.16 μM). The divergent α1D-CT:SCRIB binding affinities are suggestive of a co-operative binding mechanism, in that the binding of a single α1D-CT PDZ ligand to SCRIB enhances the affinity of subsequent intramolecular α1D-CT:SCRIB PDZ binding events. We tested this model by quantifying the affinity of SCRIB C-terminal truncation mutants missing PDZ4 (ΔPDZ4) or PDZ3 and PDZ4 (ΔPDZ34) with BLI. α1D-CT bound SCRIB ΔPDZ4 (KD = 0.14 ± 0.02 μM; Fig. 3A) and SCRIB ΔPDZ34 (KD = 0.16 ± 0.01 μM; Fig. 3B) with ~2x lower affinity than SCRIB WT (not significant, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test), but ~6x higher affinity than SCRIB PDZ1 (p = 0.001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test) or PDZ4 alone (p = 0.07, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test). In the reverse experiment, α1D-CT bound SCRIB PDZ3 and PDZ4 (PDZ34) with substantially lower affinity (KD = 0.34 ± 0.09 μM; Fig. 3C; not significant, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test) than SCRIB WT, but greater than SCRIB PDZ4 (not significant, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test). Thus, these findings are suggestive of a co-operative α1D-CT:SCRIB binding modality, and provide additional support for previous studies suggesting SCRIB PDZ34 forms a “supramodule” binding site for PDZ ligands39.

Figure 3.

In situ and in vitro analysis of α1D-adrenergic receptor C-terminal PDZ ligand:SCRIB truncation mutant interactions. (A–C). Biolayer interferometry (BLI) analyses of α1D-CT binding to SCRIB ΔPDZ4 (A), SCRIB ΔPDZ34 (B) and SCRIB PDZ34 (C). BLI data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of myc-α1D-AR with transfection vehicle (− vector), empty pGlue vector (+vector), TAP-SCRIB containing all 4 PDZ domains (WT), or sequentially truncated at the C-terminus (CT), PDZ domain 4 (ΔPDZ4), PDZ domain 3 (ΔPDZ34), PDZ domain 2 (PDZ1) or PDZ domain 1 (ΔPDZ) from HEK293 cell lysates. Shown are western blots of TAP-SCRIB constructs (top panel), myc-α1D-AR multimers (middle panel) and monomers (bottom panel). For full blots reference Supplemental Fig. 2.

We then tested the ability of SCRIB truncation mutants to co-immunoprecipitate with full length α1D-AR in mammalian cell culture. TAP-SCRIB mutants were co-transfected with myc-α1D-AR into HEK293 cells, digitonin-solubilized as cell lysates, immunoprecipitated with streptavidin beads and probed for anti-HA (TAP-SCRIB; Fig. 3D, Suppl. Fig. 2, top panel) and anti-myc (α1D-AR; Fig. 3D, lower panels). As shown, successive C-terminal SCRIB deletions produced progressive decreases in α1D-AR monomer (Fig. 3D, bottom panel, 68 kDa) and multimer (Fig. 3D, middle panel, ~250 kDa) signal, whereas SCRIB ΔPDZ produced no detectable α1D-AR interaction. Of note, the most dramatic decrease in α1D-AR binding was observed with SCRIB containing only PDZ1 (Fig. 3D, lane PDZ1).

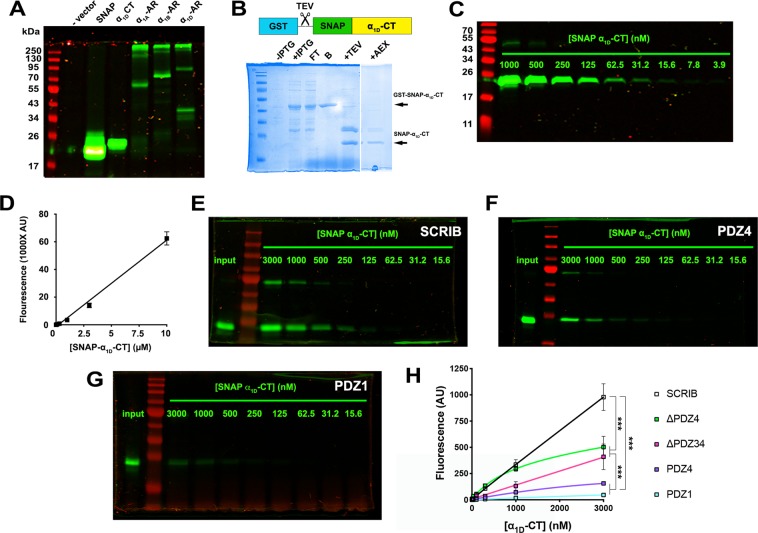

Next, SNAP GST-tag pulldown assays were used to test the proposed co-operative model of α1D-AR:SCRIB binding. The experimental approach involved the creation of a novel reporter construct: a SNAP-epitope tag adjacent to the N-terminus of the distal 16 amino acids of the α1D-CT (SNAP-α1D-CT). PAGE near infrared (NIR) analysis of HEK293 cell lysates transfected with SNAP-α1D-CT displayed protein bands of expected size 21.7 kDa (Fig. 4A). Next, GST-SNAP-α1D-CT was expressed in and purified from E. Coli, then eluted via TEV cleavage (Fig. 4B). SNAP-α1D-CT was pre-labeled with 1 μM SNAP-substrate BG-782 and subjected to PAGE NIR/LICOR Odyssey NIR imaging (Fig. 4C) to generate a standard curve (Fig. 4D). Glutathione agarose beads were incubated with previously described GST-SCRIB constructs, mixed with serial dilutions of labeled SNAP-α1D-CT, eluted, and analyzed with PAGE NIR. 10 μM BG-782 pre-labeled SNAP-α1D-CT was included in each gel as a normalization control (Fig. 4E–G, denoted as INPUT). In accordance with previous BLI experiments, SCRIB WT bound SNAP-α1D-CT in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4E), with higher avidity than PDZ4 (Fig. 4F; p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test) or PDZ1 (Fig. 4G; p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test). Interestingly, SCRIB ΔPDZ4 (~48% of SCRIB WT; p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test) and ΔPDZ34 (~34% of SCRIB WT; p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test) produced maximal SNAP-α1D-CT binding responses that were less than SCRIB WT, yet greater than single SCRIB PDZ domain constructs (<10% of SCRIB WT, Fig. 4H; p < 0.0001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test). Taken together, our findings support the model that multiple α1D-AR CT PDZ ligands bind a single molecule of SCRIB via a co-operative mechanism.

Figure 4.

SNAP-α1D-adrenergic receptor C-terminal PDZ ligand:GST-SCRIB pulldown assays indicate a co-operative binding model. (A) PAGE NIR of HEK293 cell lysates transfected with vehicle alone (− vector), pSNAP vector (SNAP), N-terminal SNAP-tagged α1D-AR C-terminus (α1D-CT), α1A, α1B and α1D-AR. (B) Coomassie stain of GST-SNAP-α1D-CT purification ± IPTG induction, unbound (FT), bound to beads (B), following TEV cleavage (+TEV) and anion exchange chromatography (AEX). (C) PAGE NIR of purified SNAP-α1D-CT pre-labeled with BG-782. (D) SNAP-α1D-CT standard curve plotting concentration of BG-782 labeled SNAP-α1D-CT versus fluorescence quantified at λ = 800 nm. (E–G) Representative PAGE NIR gels of SNAP-α1D-CT pulldowns with GST-SCRIB (E), GST-PDZ4 (F), or GST-PDZ1 (G). (H) Concentration-response curves quantifying SNAP-α1D-CT bound to GST-SCRIB, SCRIB truncated before PDZ domain (ΔPDZ4), before PDZ domain 3 (ΔPDZ34), SCRIB PDZ1, or SCRIB PDZ4 (mean ± SEM, n = 3–4). ***p < 0.001, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test.

A similar model has been proposed for numerous proteins containing multiple PDZ domains40–43. For example, PDZ domains 1 and 2 of PSD-95 exhibit greater affinity for binding partners Kv1.4, NR2B, and CRIPT when expressed in tandem40. The PDZ domains of syntenin also work co-operatively to bind syndecan dimers – syntenin PDZ2:syndecan interaction is a pre-requisite for syntenin PDZ1:syndecan binding41,42. A recent study similarly found that PDZ domains 2 and 3 of PTPN13 show enhanced binding for the PDZ ligand of APC when expressed together compared to individual domain constructs43. These previously characterized interactions further support our findings that the α1D-CT:SCRIB interaction is co-operative.

Structure-function analyses identify R1110PDZ4 as a selectivity determinant for α1D-CT binding

We next compared α1D-CT:SCRIB binding parameters to previously identified SCRIB PDZ1 and PDZ4 interactors. SCRIB PDZ1 interacts with >20 proteins32, whereas PDZ4 interacts with NOS1AP44, APC45, p22phox46, NMDA receptor subunits GLUN2A and GluN2B47, and DLC348. Remarkably, α1D-CT has the highest reported affinity to date of all reported SCRIB PDZ4 interactors. For example, the PDZ ligand of p22phox binds SCRIB PDZ4 with KD = 40 μM46, whereas the NMDA receptor PDZ ligands bind SCRIB PDZ4 with KD > 150 μM47. Thus, targeting SCRIB PDZ4 may provide the highest opportunity to disrupt α1D-AR function without perturbing other SCRIB complexes.

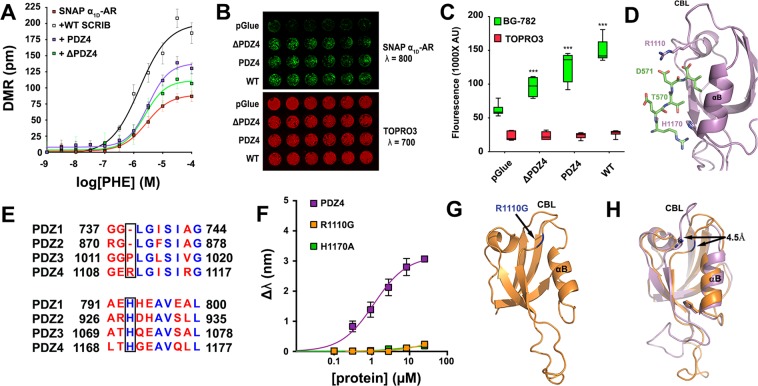

We first investigated the impact of SCRIB PDZ4 on α1D-AR functional responses. Label-free dynamic mass redistribution (DMR) signaling assays were performed using HEK293 cells stably expressing SNAP-α1D-AR alone or transiently co-expressing SCRIB WT, SCRIB PDZ4 or SCRIB ΔPDZ4. Concentration-response curves were generated for the selective α1-AR agonist phenylephrine to facilitate efficacy comparison between transfection conditions. As shown, phenylephrine efficacy was enhanced by all SCRIB constructs with rank order WT > PDZ4 > ΔPDZ4 > pGLUE vector control (Fig. 5A). Next, the ability of SCRIB mutants to promote α1D-AR plasma membrane trafficking were assessed using a 96-well plate near infrared imaging cell surface assay. The rank order of SCRIB constructs for promoting α1D-AR plasma membrane trafficking was WT > PDZ4 > ΔPDZ4 > pGlue (Fig. 5B,C). We have previously reported that α-syntrophin interacts with α1D-AR in the endoplasmic reticulum49, and that SCRIB and syntrophin co-localize and compete for the PDZ ligand of α1D-CT19. Therefore, we propose the α1D-AR:SCRIB interaction occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum to facilitate trafficking to the plasma membrane. However, further studies are warranted to determine the precise mechanism and machinery by which this complex formation is regulated.

Figure 5.

Structure-function analysis of the α1D-CT:SCRIB PDZ4 interaction. (A) Dynamic mass redistribution assays quantifying phenylephrine efficacy in HEK293 cells stably expressing SNAP-α1D-AR alone, or transfected with SCRIB WT, PDZ4, or SCRIB containing only PDZ domains 1, 2 and 3 (ΔPDZ4). Data are the mean of 12 replicates ± SEM. (B) Cell surface expression of SNAP-α1D-AR in HEK293 cells transfected with vector control (pGlue), ΔPDZ4, PDZ4, or SCRIB WT (top panel, green); nuclear stain TO-PRO-3 was used to normalize for cell number (bottom panel, red). (C) Quantification of data from B (mean ± SEM, n = 3, 6 replicates; ***p < 0.001 from pGLUE, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests). (D) Molecular docking model of α1D-CT:SCRIB PDZ4 interaction (purple = PDZ4, green = α1D-CT, PDB ID = 4WYT used for model). (E) Sequence alignment of SCRIB PDZ domains (boxes indicate residues identified in D). (F) Biolayer interferometry (BLI) analysis of SCRIB mutations H1170A and R1110G on α1D-CT binding (mean ± SEM, n = 3). (G) X-ray crystallography structure of SCRIB PDZ4 R1110G (mutation highlighted in blue; PDB ID = 6EEY). (H) R1110G (orange) causes a 4.5 Å shift in carboxylate binding loop, as determined by superposition with WT PDZ4 (purple).

Functional studies indicate targeting SCRIB PDZ4 alone may be a useful approach to modulate α1D-AR processes in vivo. However, this requires a thorough understanding of the structural determinants governing selectivity of the α1D-CT PDZ ligand for SCRIB PDZ4. Molecular docking that employed the solved crystal structure of SCRIB PDZ4 (PDB ID: 4WYT; refs.39,50,51) was used to predict α1D-CT:SCRIB PDZ4 interactions. Our model identified D571α1D-AR:R1110PDZ4 of the carboxylate binding loop and T570α1D-AR:H1170PDZ4 of α-helix B as possible α1D-CT PDZ ligand interaction sites within SCRIB PDZ4 (Fig. 5D). SCRIB PDZ domain sequence alignment revealed that R1110, but not H1170, is unique to PDZ4, suggesting that this residue may be responsible for the specificity of α1D-AR to PDZ4 (Fig. 5E). In support of our structural prediction, purified PDZ4 harboring either R1110G or H1170A mutations ablates α1D-CT binding (Fig. 5F).

Previous structural and biophysical studies have identified homologous histidine residues within Type I PDZ domains that control ligand specificity52–55. However, the structural role of R1110 is unknown. To resolve the mechanistic underpinnings of this interaction, the crystal structure of PDZ4 R1110G was solved to 1.15 Å resolution (Fig. 5G; Table 1; Suppl. Fig. S3). A superposition of the R1110G mutant with WT PDZ4 reveals a 4.5 Å shift of the carboxylate binding loop (Fig. 5H). We predict this shift creates steric hindrance that prevents the interaction between I572α1D-AR and PDZ4. Previous studies have found PDZ ligand:PDZ domain interactions are dictated by interactions of the C-terminal residue of the PDZ ligand52,55,56. For example, in situ peptide library screens revealed 89% of peptides interacting with the PDZ domain of nNOS contain a C-terminal valine56. Thus, we propose that preventing I572α1D-AR from interacting with PDZ4 is sufficient to inhibit α1D-CT binding.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for Scribble PDZ4 R1110G mutant (molecular replacement).

| SCRIB PDZ4 R1110G | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P 1 21 1 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 27.29, 40.24, 32.26 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 97.85, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 31.96–1.145 (1.186–1.145)* |

| R merge | 0.06674 (0.07563)* |

| I/σI | 12.82 (3.48)* |

| Completeness (%) | 82.58 (3.40)* |

| Redundancy | 4.4 (1.0)* |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 31.96–1.145 (1.186–1.145)* |

| No. reflections | 20613 (85)* |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.1571 (0.1385)/0.1818 (0.1574)* |

| No. atoms | 1646 |

| Protein | 692 |

| Ligand/ion | — |

| Water | 131 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 7.36 |

| Ligand/ion | — |

| Water | 16.20 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.35 |

*Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

Finally, we leveraged the information gathered from our structural studies to understand how mutations in either PDZ1 and/or PDZ4 affect the α1D-CT interaction in context of the core binding protein, SCRIB. This involved introducing H793A PDZ1 and H1170A PDZ4 mutations into GST-SCRIB (Fig. 6A, schematic) and subjecting to α1D-CT BLI analysis. As shown, SCRIB H1170A retains significant α1D-CT binding with affinity (KD = 0.32 ± 0.08 μM; Fig. 6A) similar to the SCRIB PDZ34 construct (Fig. 3D). Mutating the equivalent amino acid in SCRIB PDZ1, H793A, produced a species that retains α1D-CT binding, with ~20x lower affinity (KD = 7.34 ± 4.53 μM; Fig. 6B) than SCRIB PDZ4 H1170A. Strikingly, introducing both H793A and H1170A mutations into SCRIB abolished α1D-CT binding as measured by BLI (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Biolayer interferometry analysis of α1D-adrenergic receptor C-terminal PDZ ligand:SCRIB H793A/H1170A interactions. Biolayer interferometry (BLI) was used to quantify α1D-CT binding to full length SCRIB containing point mutations H1170A (A), H793A (B), or both H793A and H1170A (C). ▼ indicate the SCRIB PDZ domain harboring the denoted H → A mutation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3. (D) Hypothetical model of the α1D-AR:SCRIB:DAPC macromolecular complex in human cells.

Conclusions

The present study strongly suggests that α1D-CT is capable of binding each SCRIB PDZ domain, but preferentially interacts with SCRIB PDZ1 and PDZ4. Also, the α1D-CT:SCRIB interaction appears to be co-operative, potentially driving multiple α1D-AR PDZ ligands to bind one molecule of SCRIB. We previously reported α1D-ARs can be expressed as modular homodimers in human cells, with one α1D-AR protomer bound to SCRIB, the other to syntrophin and the DAPC19. Based on the results of the present study, it is possible that α1D-AR homodimers interact simultaneously with both SCRIB PDZ1 and PDZ4, with at least one α1D-AR protomer interacting with the syntrophin:DAPC via the non-SCRIB bound PDZ ligand, and the other bound to a second syntrophin:DAPC module, or the DLG:CASK:LIN-7A tripartite complex (36–38; hypothetical schematic of α1D-AR:SCRIB:DAPC shown in Fig. 6D). Alternatively, an α1D-AR protomer may bind another SCRIB, anchoring interconnected α1D-AR:SCRIB:DAPC complexes at the plasma membrane in human cells. Finally, we demonstrate that SCRIB R1110PDZ4 serves as a unique α1D-CT interface site that could be targeted to modulate α1D-AR pharmacodynamics.

Methods

Plasmids and chemicals

Molecular cloning was performed using inFusion HD cloning technology (Clontech/Takara Biotech, Mountain View, CA). Constructs used for bacterial expression were sub-cloned into a modified pGEX vector to add GST-tags. For mammalian expression, constructs were inserted into pGLUE to add streptavidin binding protein/TEV/calmodulin binding protein tags; or pSNAPf to add SNAP-epitope tags; or pcDNA3.1 to fuse MYC tags. BG-782 SNAP substrate was from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). PageRuler Prestained NIR Protein Ladder was used for all PAGE NIR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were transfected with 1 mg/ml polyethyleneimine (PEI) and used ~48 h post-transfection. For the development of the SNAP-α1D-AR stable cell line, G418 was added to the media 24 h post-transfection. [3H]-Prazosin saturation radioligand binding (data not shown) and PAGE NIR (described in 57) were used to verify SNAP-α1D-AR protein expression.

Label-free DMR assays

DMR assays were performed in 384 well Corning Epic sensor microplates (Corning, Corning, NY) using the protocol described previously57. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

Recombinant protein expression and purification

Recombinant proteins were expressed in Rosetta™ (DE3) competent cells (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA) in Miller LB supplemented with 100 μg/mL Ampicillin and 34 μg/mL Chloramphenicol at 37 °C until an OD600 = 0.6–1.0 was reached; followed by induction with IPTG (1 mM) at 18 °C for 18 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, Protease inhibitors). GST-tagged protein was immobilized on Pierce® glutathione agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and washed (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 200 mM NaCl). Bound protein was eluted from the beads in wash buffer supplemented with 10 mM glutathione and concentration was determined using Bradford assay. Immobilized protein for crystallography was incubated with TEV at 4 °C for 18 h and subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) on an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) in lysis buffer. The peak 215 nm fractions were collected. SDS-PAGE analysis was employed to determine purity, and protein was flash frozen and stored at −80 °C until needed.

SNAP GST-pulldown assay

SNAP-α1D-C terminal domain (SNAP-α1D-CT) was created by subcloning cDNA encoding the distal 16 amino acids of the human α1D-C terminal domain into the 3′ MCS of pSNAP. SNAP and SNAP-α1D-CT were then subcloned into a modified pGEX vector to add N-terminal GST tags, expressed in, and purified from E. coli using the previously described method (Fig. 4B). Following TEV cleavage and ion exchange chromatography, SNAP-α1D-CT was reacted with BG-782 (1 μM) for 30 min @37 °C in the dark. Serial dilutions of BG-782:SNAP-α1D-CT were subjected to SDS-PAGE and near infrared fluorescence (NIR: λ = 800 nm) was quantified with the LI-COR Odyssey CLx (Fig. 4C; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Fluorescence intensity standard curves for SNAP-α1D-CT were generated to calculate protein concentrations (Fig. 4D). For GST-pulldown, 25 μL of 1 μM GST-tagged SCRIB proteins and 25 μL of BG-782:SNAP-α1D-CT were incubated with 25 μL of packed Pierce® glutathione agarose beads and rotated in the dark for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged @ 500 RPM at 4 °C for 5 min. Supernatant was discarded and beads were washed 3x (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.05% NP-40). Samples were boiled in SDS-sample buffer, and 10 μL aliquots were subjected to PAGE NIR.

Affinity purification/Co-immunoprecipitation

TAP purification was performed using the protocol described previously19,20. 5 μL of 25 μM BG-782 was included in the 1st overnight solubilization step with 0.5% digitonin to label SNAP-α1D-ARs. PAGE NIR was used to observe SNAP-α1D-AR protein levels. Gels were then transferred to nitrocellulose and blotted for anti-HA (#2367, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or anti-MYC (#9B11, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), then anti-mouse Alexa-Fluor 2° antibodies in the 700–800 nm range (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Gels and blots were imaged with the LI-COR Odyssey CLx.

Biolayer interferometry (BLI)

BLI was performed using the Octet Red 96 system (Pall Forte Bio, Fremont, CA). All steps were performed in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. 50 nM of biotin labeled peptide containing the last 20 amino acids of the α1D-CT (BioMatik, Cambridge, ON) was immobilized to streptavidin coated probes, followed by biocytin. The immobilized peptide was incubated in serial dilutions of target proteins until steady-state binding was reached. Biocytin was used to determine non-specific binding. For reverse BLI, GST-SCRIB was immobilized using anti-GST probes, and then incubated in serial dilutions of biotin labeled α1D-CT.

Cell surface assay

HEK293 cell surface expression of SNAP-α1D-AR was quantified with cell impermeable SNAP-substrate BG-782 using the method described previously57. TO-PRO-3 nuclear stain was used to normalize samples according to cell number. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software.

X-ray crystallography

SCRIB PDZ4 R1110G was concentrated to 11 mg/mL in 20 mM Tris at pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 5 mM DTT and screened against crystallization conditions using a Mosquito Liquid Handler (TTP Labtech, Cambridge, MA). Final crystals were obtained in 21% PEG 3,350 and 0.25 M Ammonium Nitrate. Crystals were flash frozen in mother liquor supplemented with 15% glycerol. All diffraction data was collected at the Advanced Light Source at Berkeley on beam line 8.2.1, integrated with XDS58, and scaled with AIMLESS59,60. Phases were determined by molecular replacement using Phaser61 and SCRIB PDZ4 (39; PDB ID: 4WYT) as a search model. The Phaser solution was manually rebuilt over multiple cycles using Coot62 and refined using PHENIX63. All images were generated using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.74 Schrödinger, LLC. Coordinate files have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 6EEY.

Molecular docking

The distal 6 amino acids of the α1D-AR C-terminus, LRETDI, was modeled into the canonical βB and αB binding pocket of Scribble PDZ439 using PyMOL and submitted to FlexPepDock server50,51. Models with scores greater than −131 were analyzed for hydrogen bonding (1.5–2.5Å) between peptide and PDZ4. Only interactions identified in greater than 5 models are reported.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIGMS T32GM007750 (E.J., D.A.H.) and R01GM100893 (C.H.) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (N.Z.).

Author Contributions

E.M.J. and C.H. designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. D.A.H., D.D. and A.S. performed experiments. T.R.H. contributed to experimental design and analysis of BLI experiments. E.M.J., P.L.H. and N.Z. contributed to collection and interpretation of X-ray crystallography data. All co-authors contributed to editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50671-6.

References

- 1.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shukla AK, Xiao K, Lefkowitz RJ. Emerging paradigms of β-arrestin-dependent seven transmembrane receptor signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011;36:457–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero G, von Zastrow M, Friedman PA. Role of PDZ proteins in regulating trafficking, signaling, and function of GPCRs: means, motif, and opportunity. Adv. Pharmacol. 2011;62:279–314. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385952-5.00003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritter SL, Hall RA. Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrm2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsunoda S, et al. A multivalent PDZ-domain protein assembles signaling complexes in a G-protein-coupled cascade. Nature. 1997;388:243–249. doi: 10.1038/40805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall RA, et al. The β2-adrenergic receptor interacts with the Na+/H+-exchanger regulatory factor to control Na+/H+ exchange. Nature. 1998;392:626–630. doi: 10.1038/33458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauffer BE, et al. SNX27 mediates PDZ-directed sorting from endosomes to the plasma membrane. J. Cell. Biol. 2010;190:565–574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gage RM, Matveeva EA, Whiteheart SW, von Zastrow M. Type I PDZ ligands are sufficient to promote rapid recycling of G protein-coupled receptors independent of binding to N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3305–3313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, et al. β1-adrenergic receptor association with the synaptic scaffolding protein membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted-2 (MAGI-2) J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41310–41317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillaume JL, et al. The PDZ protein mupp1 promotes Gi coupling and signaling of the Mt1 melatonin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16762–16771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn HA, Ferguson SS. PDZ protein regulation of G protein-coupled receptor trafficking and signaling pathways. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015;88:624–639. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.098509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey LM, et al. Small molecular inhibitors of PSD95-nNOS protein-protein interactions suppress formalin-evoked Fos protein expression and nociceptive behavior in rats. Neuroscience. 2017;349:303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee WH, et al. ZLcOO2, a putative small-molecule inhibitor of nNOS interaction with NOS1AP, suppresses inflammatory nociception and chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain and synergizes with paclitaxel to reduce tumor cell viability. Mol. Pain. 2018;14:1–17. doi: 10.1177/1744806918801224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WH, et al. Disruption of nNOS-NOS1AP protein-protein interactions suppresses neuropathic pain in mice. Pain. 2018;159:849–863. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li LL, et al. The nNOS-p38 MAPK pathway is mediated by NOS1AP during neuronal death. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:8185–8201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4578-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z, Hague C, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Syntrophins regulate α1D-adrenergic receptors through a PDZ domain-mediated interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:12414–12420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyssand JS, et al. α-Dystrobrevin-1 recruits α-catulin to the α1D-adrenergic receptor/dystrophin-associated protein complex signalosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21854–21859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010819107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyssand JS, Lee KS, DeFino M, Adams ME, Hague C. Syntrophin isoforms play specific functional roles in the α1D-adrenergic receptor/DAPC signalosome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;412:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camp ND, et al. Individual protomers of a G protein-coupled receptor dimer integrate distinct functional modules. Cell Discov. 2015;1:15011. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2015.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camp ND, et al. Dynamic mass redistribution reveals diverging importance of PDZ-ligands for G protein-coupled receptor pharmacodynamics. Pharmacol. Res. 2016;105:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Cazarin ML, et al. The α1D-adrenergic receptor is expressed intracellularly and coupled to increases in intracellular calcium and reactive oxygen species in human aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Mol. Signal. 2008;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrovska R, Kapa I, Klovins J, Schiöth HB, Uhlén S. Addition of a signal peptide sequence to the α1D-adrenoceptor gene increases the density of receptors, as determined by [3H]-prazosin binding in the membrane. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;144:651–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hague C, Uberti MA, Chen Z, Hall RA, Minneman KP. Cell surface expression of α1D-adrenergic receptors is controlled by heterodimerization with α1B-adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:15541–15549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sever PS. Alpha 1-blockers in hypertension. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 1999;15(2):95–103. doi: 10.1185/03007999909113369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walden PD, Gerardi C, Lepor H. Localization and expression of the α1A, α1B and α1D-adrenoceptors in hyperplastic and non-hyperplastic human prostate. J. Urol. 1999;161:635–640. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61986-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampel C, et al. Modulation of bladder α1-adrenergic receptor subtype expression by bladder outlet obstruction. J. Urol. 2002;167:1513–1521. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, et al. The association of DNA methylation and brain volume in healthy individuals and schizophrenia patients. Schizophr. Res. 2015;169:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raskind MA, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:507–517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson VG, et al. The role of norepinephrine in differential response to stress in an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;70:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller JL. Doxazosin dropped from ALLHAT study. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2011;57:718. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.8.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stucke VM, Timmerman E, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K, Hall A. The MAGUK protein MPP7 binds to the polarity protein hDlg1 and facilitates epithelial tight junction formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:1744–1755. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-11-0980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens R, et al. The Scribble cell polarity module in the regulation of cell signaling in tissue development and tumorigenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2018;430:3585–3612. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathew D, et al. Recruitment of scribble to the synaptic scaffolding complex requires GUK-holder, a novel Dlg binding protein. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:531–539. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu J. Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between tumor suppressors Dlg and Lgl. Cell Res. 2014;24:451–463. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kallay LM, McNickle A, Brennwald PJ, Hubbard AL, Braiterman LT. Scribble associates with two polarity proteins, Lgl2 and Vangl2, via distinct molecular domains. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;99:647–664. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butz S, Okamoto M, Südhof TC. A tripartite protein complex with the potential to couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to cell adhesion in brain. Cell. 1998;94:773–782. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borg JP, et al. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved heterotrimeric protein complex involved in protein targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3163–31636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S, Fa S, Makarova O, Straight S, Margolis B. A novel and conserved protein-protein interaction domain of mammalian Lin-2/CASK binds and recruits SAP97 to the lateral surface of epithelia. Mole. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:1778–1791. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.6.1778-1791.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren J, et al. Interdomain interface-mediated target recognition by the Scribble PDZ34 supramodule. Biochem. J. 2015;468:133–144. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long JF, et al. Supramodular structure and synergistic target binding of the N-terminal tandem PDZ domains of PSD-95. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:203–214. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grootjans JJ, Reekmans G, Ceulemans H, David G. Syntenin-syndecan binding requires syndecan-synteny and the co-operation of both PDZ domains of syntenin. J. Boil. Chem. 2000;275:19933–19941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002459200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grembecka J, et al. The binding of the PDZ tandem of syntenin to target proteins. Biochem. J. 2006;45:3674–3683. doi: 10.1021/bi052225y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dicks, M. et al. The binding affinity of PTPN13’s tandem PDZ2/3 domain is allosterically modulated. BMC Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 10.1186/s12860-019-0203-6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Richier L, et al. NOS1AP associates with Scribble and regulates dendritic spine development. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:4796–4805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3726-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takizawa S, et al. Human scribble, a novel tumor suppressor identified as a target of high-risk HPV E6 for ubiquitin-mediated degradation, interacts with adenomatous polyposis coli. Genes Cells. 2006;11:453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng W, et al. An interaction between Scribble and the NADPH oxidase complex controls M1 macrophage polarization and function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:1244–1252. doi: 10.1038/ncb3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piguel NH, et al. Scribble1/AP2 complex coordinates NMDA receptor endocytic recycling. Cell Rep. 2014;9:712–727. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrick J, et al. The polarity protein Scribble positions DLC3 at adherens junctions to regulate Rho signaling. J Cell Sci. 2016;19:3583–3596. doi: 10.1242/jcs.190074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyssand JS, et al. Blood pressure is regulated by an α1D-adrenergic receptor/dystrophin signalosome. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18792–18800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801860200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raveh B, London N, Schueler‐Furman O. Sub‐angstrom modeling of complexes between flexible peptides and globular proteins. Proteins. 2010;78:2029–2040. doi: 10.1002/prot.22716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.London N, Raveh B, Cohen E, Fathi G, Schueler-Furman O. Rosetta FlexPepDock web server—high resolution modeling of peptide–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W249–W253. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doyle DA, et al. Crystal structures of a complexed and peptide-free membrane protein–binding domain: molecular basis of peptide recognition by PDZ. Cell. 1996;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mamonova T, et al. Origins of PDZ binding specificity. A computational and experimental study using NHERF1 and the parathyroid hormone receptor. Biochemistry. 2017;56:2584–2593. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Songyang Z, et al. Recognition of unique carboxyl-terminal motifs by distinct PDZ domains. Science. 1997;275:73–77. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Babault N, et al. Peptides targeting the PDZ domain of PTPN4 are efficient inducers of glioblastoma cell death. Structure. 2011;19:1518–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strickler NL, et al. PDZ domain of neuronal nitric oxide synthase recognizes novel C-terminal peptide sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997;15:336–342. doi: 10.1038/nbt0497-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kountz TS, et al. Endogenous N-terminal domain cleavage modulates α1D-adrenergic receptor pharmacodynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:8210–18221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.729517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCoy, A.J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Emsley P, Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams PD, et al. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution; pp. 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.