Abstract

This population-based cross-sectional study investigated the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus in premenopausal Korean women. We used data from the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2010–2012). A total of 4633 premenopausal women were included. Hierarchical multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed. Individuals with tinnitus accounted for 21.6%. Women with tinnitus or menstrual irregularity had significantly higher rates of stress, depressive mood, and suicidal ideation than those without. The proportion of individuals with irregular menstrual cycles with duration of longer than 3 months increased as the severity of tinnitus increased (P = 0.01). After adjusting for confounding variables, the odds of tinnitus increased in individuals with irregular menstrual cycles compared to those with regular menstrual cycles. The odds ratios (ORs) of tinnitus tended to increase as the duration of menstrual irregularity became longer (1.37, 95% confidence interval: 1.06–1.78 for duration of up to 3 months; 1.71, 1.03–2.85 for duration of longer than 3 months, P for trend = 0.002). Our study found a positive association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. Menstrual cycle irregularity may be a related factor of tinnitus in women with childbearing age.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Reproductive signs and symptoms

Introduction

Tinnitus refers to a perception of sound even in the absence of external auditory stimuli1. The prevalence of tinnitus has been reported to be between 5.1% and 42.7% worldwide1. In Korea, the prevalence is reported to be 20.7%, and the proportion of those who experience annoyance due to tinnitus is as high as 30%2. The prevalence of tinnitus and annoyance caused by tinnitus increases with age2, and the annoyance seems to be more severe with a longer durations3. People with tinnitus may also have health problems such as hearing loss, sleep disturbance, and hyperacusis4. However, this highly debilitating condition is difficult to cure and there are no satisfactory treatments5. Therefore, it is very important to evaluate and control modifiable risk factors of tinnitus.

People with tinnitus are more likely to complain of mental health problems. Lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders reaches 45% among individuals with tinnitus6. They experience lower self-esteem and well-being7, and moreover, 7.2% of patients with severe tinnitus had ever attempted suicide8. Tinnitus was also associated with stress9 and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, which is found in stress-related disorders10. Abnormally increased levels of stress related hormones such as norepinephrine or 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid were observed in people with tinnitus11 and tinnitus may be exacerbated by stress and lack of sleep12. In particular, psychological symptoms observed in patients with tinnitus aggravate the distress experience due to tinnitus, and subsequently decrease their quality of life13. The odds of tinnitus and annoying tinnitus were reported to be higher in women than men14. Also, women experience a greater degree of tinnitus-related distress than men15. Moreover, various mental health characteristics in women with tinnitus may be related to their menstrual cycle16,17. Therefore, it appears that tinnitus needs to be managed carefully, especially in women.

Menstrual cycle regularity is a non-invasive clinical parameter to assess female physical health status or reproductive capacity, and is influenced by age, lifestyle, and various physical conditions18–20. Menstrual cycle irregularities are common in women of childbearing age21,22, and have been reported to be associated with various chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease23, and breast cancer24 as well as infertility25. Menstrual cycle irregularity is also associated with mental health characteristics in women17,26. Psychological factors such as anxiety and depression are risk factors for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which is known to cause menstrual cycle irregularity27. In this way, both tinnitus and menstrual cycle irregularity seem to be closely related to the physical and mental health in women. In addition, a previous study reported higher prevalence of tinnitus in pregnant than in non-pregnant women and suggested a relationship between female hormonal changes and tinnitus28. However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus has been scarcely studied.

Therefore, we investigated the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus in women of childbearing age by using nationwide representative data from the South Korean population.

Results

Characteristics of study participants according to the presence of tinnitus

Table 1 shows the characteristics of study participants according to the presence of tinnitus. Of the total participants, 21.6% reported experiencing tinnitus. The mean age was 35.8 ± 0.2 and 34.0 ± 0.4 years in individuals without and with tinnitus, respectively (P < 0.001). The proportion of menstrual cycle irregularity was higher in participants with tinnitus than those without (P = 0.001). The group with tinnitus showed lower education and income levels than the group without tinnitus (P = 0.007 and <0.001, respectively). There were no differences in residential areas and occupations between the two groups. The participants with tinnitus had a higher rate of smoking than those without tinnitus (P = 0.003), however, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and sleep duration did not differ between two groups according to tinnitus. The women without tinnitus had significantly more experience of childbirth than those with tinnitus, while rate of oral contraceptive use were similar between two groups. BMI was slightly higher in individuals without tinnitus than those with tinnitus (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants according to the presence of tinnitus.

| N | Tinnitus | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| 3699 | 934 | ||

| Age (years) | 35.8 ± 0.2 | 34.0 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Menstrual cycle irregularity | 14.1 (0.7) | 19.7 (1.7) | 0.001 |

| Educational level | 0.007 | ||

| ≤Elementary school | 2.7 (0.3) | 4.7 (0.8) | |

| Middle school | 5.7 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.8) | |

| High school | 48.0 (1.1) | 51.3 (2.0) | |

| ≥University | 43.6 (1.1) | 38.2 (2.0) | |

| Household income level | <0.001 | ||

| Q1 | 7.7 (0.7) | 12.7 (1.5) | |

| Q2 | 28.0 (1.1) | 28.6 (1.9) | |

| Q3 | 32.7 (1.0) | 29.5 (1.7) | |

| Q4 | 31.6 (1.1) | 29.2 (1.9) | |

| Residential area (urban) | 85.8 (1.5) | 87.5 (1.8) | 0.282 |

| Occupation (unemployed) | 42.1 (1) | 44.6 (2.1) | 0.273 |

| Ex-smokers or current smokers | 9.1 (0.6) | 13 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| Heavy alcohol drinkers | 3.3 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.7) | 0.590 |

| Regular exercisers | 83.3 (0.8) | 82 (1.7) | 0.452 |

| Sleep duration (hours) | 7.0 ± 0.0 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.288 |

| Parity (yes) | 67.7 (1.1) | 58.3 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Ever use of oral contraceptives (yes) | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.9 (1.2) | 0.397 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.6 ± 0.1 | 22.5 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard error or percentage (standard error).

*p-values were obtained using an independent t-test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables.

Mental health characteristics according to the presence of menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus

Table 2 shows mental health characteristics according to menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. Individuals with menstrual cycle irregularity had higher rates of experiencing stress (P = 0.001), depressive mood (P < 0.001), and suicidal ideation (P < 0.001) than those with regular menstrual cycle. Similarly, women with tinnitus also had higher rate of experiencing all these mental health problems than those without tinnitus (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Mental health characteristics according to the presence of menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus.

| Stress (yes) (n = 1494) |

Depressive mood (yes) (n = 640) | Suicidal ideation (yes) (n = 673) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menstrual cycle irregularity | |||

| No | 32.4 (0.9) | 13.5 (0.7) | 14.9 (0.7) |

| Yes | 40.0 (2.2) | 20.5 (1.7) | 21.8 (1.9) |

| p-value* | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tinnitus | |||

| No | 31.3 (1.0) | 13.0 (0.6) | 13.7 (0.7) |

| Yes | 41.8 (2.0) | 19.9 (1.6) | 24.2 (1.8) |

| p-value* | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

*p-values were obtained using a chi-square test.

Data are presented as percentage (standard error).

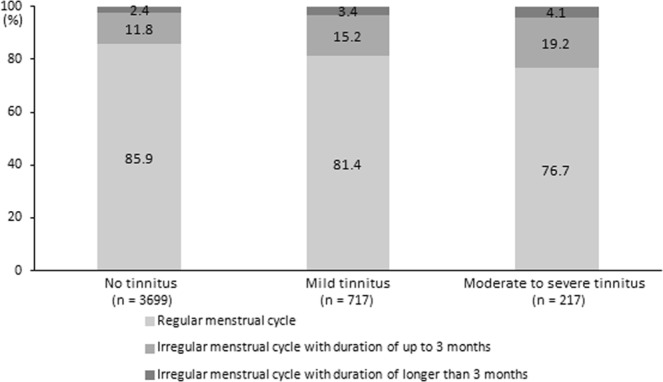

Distribution of menstrual cycle characteristics according to the tinnitus severity

Figure 1 shows the proportion of menstrual cycle characteristics according to tinnitus severity. As the severity of tinnitus increased, the proportion of individuals with a regular menstrual cycle decreased. Also, the proportion of those with irregular menstrual cycles with duration of longer than 3 months increased with more severe tinnitus (P = 0.01).

Figure 1.

The distribution of menstrual cycle characteristics according to tinnitus severity (P = 0.01 by using a chi-square test).

Odds of tinnitus according to menstrual cycle characteristics

Table 3 shows the adjusted ORs (95% CIs) of tinnitus according to menstrual cycle characteristics. After adjustment for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, parity, and BMI (model 1), the ORs of tinnitus were greater in the irregular menstrual cycle group than in the regular menstrual cycle group (1.41, 95% CI: 1.09–1.82 for irregular menstrual cycle with duration of up to 3 months; 1.77, 95% CI: 1.05–2.97 for irregular menstrual cycle with duration of longer than 3 months, P for trend = 0.001). These associations between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus persisted even after further adjustment for educational level, household income level, sleep duration, use of oral contraceptives, psychological stress, and depressive mood (model 2). The ORs of tinnitus were 1.37 (95% CI: 1.06–1.78) for women with irregular menstrual cycles with durations of up to 3 months and 1.71 (95% CI: 1.03–2.85) for those with irregular menstrual cycle with durations of longer than 3 months (P for trend = 0.002).

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) of tinnitus according to menstrual cycle characteristics.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Regular menstrual cycle | 1 | 1 |

| Irregular menstrual cycle with duration of up to 3 months | 1.41 (1.09–1.82) | 1.37 (1.06–1.78) |

| Irregular menstrual cycle with duration of longer than 3 months | 1.77 (1.05–2.97) | 1.71 (1.03–2.85) |

| p for trend | 0.001 | 0.002 |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, parity, and body mass index.

Model 2 was adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol intake, physical activity, parity, body mass index, educational level, household income level, sleep duration, use of oral contraceptives, psychological stress, and depressive mood.

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the association between menstrual cycle irregularities and tinnitus among premenopausal women. There was a significant positive association between irregular menstrual cycles and the odds of tinnitus. Especially, odds of tinnitus increased as the durations between the menstrual cycles were longer. These associations between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus were continued irrespective of adjustment for potential confounding variables regarding sociodemographic, lifestyle, physical, and mental health characteristics. Our findings suggest that menstrual cycle irregularity may be a risk factor of tinnitus in premenopausal women.

Previous studies reported that tinnitus patients often experience mental health problems such as stress12, and anxiety6. Also, mental health status has been reported to affect regularity of menstrual cycles16,17,27. However, no study has explored the relationship between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. Interestingly, a few studies have shown that hormonal changes during menstrual cycles are associated with hearing problems such as tinnitus28, hyperacusis29, and hearing threshold changes30,31. Furthermore, there was observed a high-frequency hearing loss in women with PCOS, which is a risk factor for menstrual irregularity32. Additionally, female hormone replacement therapy was shown to help alleviate tinnitus in postmenopausal women33,34. These previous studies suggest possible associations between sex hormone status and tinnitus in women and consistently support our findings on the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. To the best of our knowledge, our study is meaningful as the first population-based study to identify the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus in women of childbearing age. Notably, irregular menstrual cycles with longer durations were more likely to be associated with severe tinnitus.

Our study also found the possible association of mental health problems with menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus; several previous studies supported this finding. A greater risk of menstrual cycle irregularity was shown with increased depression and decreased psychological well-being in adult women17. In addition, high levels of stress and depressive mood were associated with menstrual cycle irregularity in adolescents and female college students16,26. Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle were associated with suicidal attempts and suicidal ideation in adult women35. In particular, irregular menstrual cycles in female adolescents were associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation36. Regarding the association between mental health and tinnitus, a study for Egyptian outpatients reported that the duration of exposure to tinnitus was associated with severity of depression, and severity of tinnitus with severity of stress9. A study for healthy Koreans also showed that tinnitus occurrence was associated with an increase in perceived stress or stress hormones levels11. Moreover, a recent Swedish cross-sectional study reported that severe tinnitus was associated with suicide attempt in women8. Although the mechanism linking menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus has not been revealed, from collected findings of mentioned previous studies, a possible mediating effect of mental health problems between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus may be inferred. In addition, from evidence that many genetic factors are associated with menstrual cycle37 and genetic factor may be predisposed in young people especially for bilateral tinnitus38, genetic factors may potentially contribute to the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. Further studies are needed to confirm the associations.

There are some limitations in this study. First, this study is based on retrospective self-reported data; therefore, there may be a recall bias. Second, it is not possible to deduce the causal relationship between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus from cross-sectional design. Third, only questionnaire-based data without objective examinations were used to define menstrual cycle regularity, tinnitus, and mental health problems due to lack of data from the KNHANES, thus it was impossible to identify them more accurately and to reflect fluctuations of them over time. Fourth, menstrual cycle irregularity was classified into three groups based only on longer duration. Although confirmative diagnostic criteria for menstrual cycle irregularity have still not been established, it is necessary to classify menstrual cycle irregularity with more detailed parameters in later studies. Fifth, prevalent mental health problems such as anxiety were not considered due to lack of data from KNHANES. Despite these limitations, the major strength of this study is that it is the first study to confirm the association between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus, suggesting the clinical implications of menstrual cycle irregularity in assessing hearing problems in women. Furthermore, this study used nationally representative data with large samples; thus, it might provide epidemiologic evidence for single ethnicity. Additionally, this study accounted for comprehensive potential confounding factors which might be related to both menstrual irregularity and tinnitus.

In conclusion, our study found the positive associations between menstrual cycle irregularity and tinnitus. Menstrual cycle irregularity may be considered as a related factor in assessing tinnitus in women with child bearing age. Furthermore, our results suggest appropriate interventions to alleviate tinnitus symptoms through accurate assessment and management of menstrual cycle irregularity in women. Further studies such as case-control and cohort studies are warranted to confirm the associations between menstrual irregularity and tinnitus.

Methods

Data source and participants

This study used data from the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) for three years from 2010 to 2012. KNHANES has been conducted annually to identify the health and nutritional status of non-institutionalized civilians of South Korea, since 1998. It is designed as a rolling sampling survey method so that each of the three years can be independently representative of the nationwide probability sample. In the KNHANES, a stratified, multi-stage, and clustered probability design was used to improve the accuracy of the representative sample. The survey items include three parts: health interview, health examination, and nutritional surveys. The survey protocol is reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of KCDC. Written informed consent was taken from all participants of the survey. This study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Of the 13,918 female adults who participated in the 5th KNHANES, we excluded those aged <19 or >54 years old (n = 7416), those in menopausal state (n = 1733), those who were pregnant (n = 2), and those with missing data (n = 134). Finally, data of 4633 female adults were analyzed. The data are accessible at http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/main.do.

Definition of tinnitus

The presence of tinnitus was assessed based on the participants’ responses to the following question: “Have you experienced tinnitus within the past year (ringing, buzzing, roaring, or hissing sound)?” If participants answered “yes”, they were required to mark one of the following questionnaires responses: (1) My tinnitus is not annoying; (2) My tinnitus is annoying and makes me nervous; (3) My tinnitus is severely annoying and causes sleep problems. Based on the participants’ responses, the severity groups of tinnitus were indicated as mild, moderate, and severe.

Menstrual cycle characteristics

Menstrual cycle characteristics were assessed by asking the participants to recall their menstrual cycle duration. Participants who responded “yes” to the following question; “Do you have a regular menstrual cycle?” were identified as having regular menstrual cycles, while those who responded “no” were as having irregular menstrual cycles. In addition, if women indicated menstrual cycle irregularity, they were asked about the duration between menstruations (up to 3 months or longer than 3 months).

Covariates

Participants’ socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics were assessed through a self-reported questionnaire or by trained interviewers. Educational level was classified into four groups as follows; below elementary school graduated, completed middle school, completed high school, and university graduated or higher. Income level was classified based on the quartile groups of monthly household income. Residential area was divided into urban and rural, and occupation was divided as having a job and unemployed. Smoking status was divided into ex-smokers or current smokers, and non-smokers. Ex-smokers or current smokers were defined as those who are currently smoking or have smoked for at least one day in the past month. Regarding alcohol drinking, individuals who drank more than 30 grams a day were defined as heavy drinkers. Physical activity was assessed by using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form for Koreans39. Individuals who exercised moderately more than 30 min per session for more than 5 times a week or those who performed vigorous exercise more than 20 min per session for more than three times a week were considered as performing regular physical activity. Sleep duration was assessed by the question “How many hours do you usually sleep a day?” In addition, parity was assessed by the question regarding whether she has had childbirth. Ever use of oral contraceptives was also assessed.

The mental health characteristics were assessed regarding psychological stress, depressive mood, and suicidal ideation. Stress was assessed using the question “How much stress do you usually feel in your daily life?” Participants who responded with a stress level of “severe” or “a lot” were defined as the high-stress group, while those who responded with “a little” or “rare” as the low-stress group. Participants who responded “yes” to the question “Have you felt sad or desperate for two consecutive weeks during the past year?” were defined as having a depressive mood. Participants who responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever considered suicide in the past year?” were defined as having a suicidal ideation.

Trained staff measured participants’ height and weight, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated by the following formula: weight (kg)/height2 (m2).

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) survey procedure was used for statistical analysis. Chi-square test or independent t-test was performed to identify differences in participants’ characteristics according to menstrual cycle irregularity or tinnitus. The results were expressed as percentage (standard error) and mean ± standard error. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of tinnitus according to menstrual cycle irregularity were calculated using a hierarchical multivariable logistic regression analysis. Model 1 was adjusted for age, smoking status, alcohol drinking, physical activity, parity, and BMI. Model 2 was adjusted for the variables considered in model 2 plus educational level, household income level, sleep duration, ever use of oral contraceptives, psychological stress, and depressive mood.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate KCDC for providing data.

Author Contributions

J.N.Y., G.E.N., K.H., J.K., G.K. and Y.K.R. conceived and designed the study. K.H. and G.K. performed statistical analyses. J.N.Y., G.E.N., K.H., J.K., Y.H.K., K.H.C., G.K. and Y.K.R. interpreted the data and contributed to the preparation of the article. J.N.Y., G.E.N. and Y.K.R drafted the article. Y.K.R. supervised the study. J.N.Y. and G.E.N. contributed equally to this work. All authors critically revised the article and have approved the final version of manuscript for submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jin-Na Yu and Ga Eun Nam contributed equally.

References

- 1.McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, Hall D. A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear. Res. 2016;337:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HJ, et al. Analysis of the prevalence and associated risk factors of tinnitus in adults. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Rochtchina E, Karpa MJ, Mitchell P. Incidence, persistence, and progression of tinnitus symptoms in older adults: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ear Hear. 2010;31:407–412. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181cdb2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Tinnitus Association. Tinnitus, understanding the facts, https://www.ata.org/understanding-facts (2014).

- 5.Miroddi M, et al. Clinical pharmacology of melatonin in the treatment of tinnitus: a review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015;71:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pattyn T, et al. Tinnitus and anxiety disorders: A review. Hear. Res. 2016;333:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krog NH, Engdahl B, Tambs K. The association between tinnitus and mental health in a general population sample: results from the HUNT Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010;69:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lugo A, et al. Sex-Specific Association of Tinnitus With Suicide Attempts. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck. Surg. 2019;145:685–687. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.0566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomaa MA, Elmagd MH, Elbadry MM, Kader RM. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale in patients with tinnitus and hearing loss. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:2177–2184. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazurek B, Szczepek AJ, Hebert S. Stress and tinnitus. HNO. 2015;63:258–265. doi: 10.1007/s00106-014-2973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DK, et al. Diagnostic value and clinical significance of stress hormones in patients with tinnitus. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:2915–2921. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan T, Tyler RS, Ji H, Coelho C, Gogel SA. Differences Among Patients That Make Their Tinnitus Worse or Better. Am. J. Audiol. 2015;24:469–476. doi: 10.1044/2015_aja-15-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brüggemann P, et al. Impact of Multiple Factors on the Degree of Tinnitus Distress. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016;10:341. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park RJ, Moon JD. Prevalence and risk factors of tinnitus: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2011, a cross-sectional study. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2014;39:89–94. doi: 10.1111/coa.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seydel C, Haupt H, Olze H, Szczepek AJ, Mazurek B. Gender and chronic tinnitus: differences in tinnitus-related distress depend on age and duration of tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2013;34:661–672. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828149f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagma S, et al. To evaluate the effect of perceived stress on menstrual function. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015;9:Qc01–03. doi: 10.7860/jcdr/2015/6906.5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toffol E, Koponen P, Luoto R, Partonen T. Pubertal timing, menstrual irregularity, and mental health: results of a population-based study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2014;17:127–135. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0399-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jukic AM, et al. Accuracy of reporting of menstrual cycle length. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167:25–33. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang PJ, Chen PC, Hsieh CJ, Chiu LT. Risk factors on the menstrual cycle of healthy Taiwanese college nursing students. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009;49:689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinkerton JV, Guico-Pabia CJ, Taylor HS. Menstrual cycle-related exacerbation of disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;202:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cakir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A. Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr. Int. 2007;49:938–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2007.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karout N, Hawai SM, Altuwaijri S. Prevalence and pattern of menstrual disorders among Lebanese nursing students. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012;18:346–352. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gast GC, et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics and risk of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Fertil. Steril. 2010;94:2379–2381. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balekouzou A, et al. Reproductive risk factors associated with breast cancer in women in Bangui: a case-control study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0368-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowland AS, et al. Influence of medical conditions and lifestyle factors on the menstrual cycle. Epidemiology. 2002;13:668–674. doi: 10.1097/01.Ede.0000024628.42288.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu M, Han K, Nam GE. The association between mental health problems and menstrual cycle irregularity among adolescent Korean girls. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;210:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fraser IS, Critchley HO, Broder M, Munro MG. The FIGO recommendations on terminologies and definitions for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2011;29:383–390. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurr P, Owen G, Reid A, Canter R. Tinnitus in pregnancy. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1993;18:294–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baribeau J. Hormonal related variability in auditory dysfunctions. Ann Rev Cyberther Telemed. 2007;5:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farage MA, Osborn TW, MacLean AB. Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008;278:299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souza DDS, et al. Variation in the Hearing Threshold in Women during the Menstrual Cycle. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;21:323–328. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1598601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kucur C, et al. Extended high frequency audiometry in polycystic ovary syndrome. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:482689. doi: 10.1155/2013/482689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai JT, Liu CL, Liu TC. Hormone replacement therapy for chronic tinnitus in menopausal women: Our experience with 13 cases. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2017;42:1366–1369. doi: 10.1111/coa.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SS, Han KD, Joo YH. Association of perceived tinnitus with duration of hormone replacement therapy in Korean postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013736. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baca-Garcia E, et al. Suicide attempts among women during low estradiol/low progesterone states. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010;44:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith A, et al. Cycles of risk: associations between menstrual cycle and suicidal ideation among women. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;74:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruth KS, et al. Genetic evidence that lower circulation FSH levels lengthen menstrual cycle, increase age at menopause and impact female reproductive health. Hum. Reprod. 2016;31:473–481. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mass IL, et al. Genetic susceptibility to bilateral tinnitus in a Swedish twin cohort. Genet. Med. 2017;19:1007–1012. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oh JY, Yang YJ, Kim BS, Kang JH. Validity and Reliability of Korean Version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Short Form. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2007;28:532–541. [Google Scholar]