Abstract

Larimichthys crocea is an endemic marine fish in East Asia that belongs to Sciaenidae in Perciformes. L. crocea has now been recognized as an “iconic” marine fish species in China because not only is it a popular food fish in China, it is a representative victim of overfishing and still provides high value fish products supported by the modern large-scale mariculture industry. Here, we report a chromosome-level reference genome of L. crocea generated by employing the PacBio single molecule sequencing technique (SMRT) and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technologies. The genome sequences were assembled into 1,591 contigs with a total length of 723.86 Mb and a contig N50 length of 2.83 Mb. After chromosome-level scaffolding, 24 scaffolds were constructed with a total length of 668.67 Mb (92.48% of the total length). Genome annotation identified 23,657 protein-coding genes and 7262 ncRNAs. This highly accurate, chromosome-level reference genome of L. crocea provides an essential genome resource to support the development of genome-scale selective breeding and restocking strategies of L. crocea.

Subject terms: Sequencing, Genome, DNA sequencing, Ichthyology

| Measurement(s) | reference genome data |

| Technology Type(s) | DNA sequencing |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Larimichthys crocea |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.9767096

Background & Summary

Larimichthys crocea, as known as large yellow croaker, is an endemic marine fish in East Asia that belongs to Sciaenidae in Perciformes. L. crocea has been ranked as one of the top commercial marine fishery species in China in the past two centuries. According to a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimate, the fraction of the world’s marine fish stocks fished at biologically unsustainable levels have reached 33.1% in 20151, and among them, L. crocea has been widely recognized as one of the most depleted and threatened marine fishery species in China due to overfishing in the 1970s and 1980s2. A method of artificial reproduction/propagation for L. crocea was successfully developed based on a small group of wild L. crocea adults collected from the wild population in Fujian Province in the late 1980s. Since then, offshore mariculture of L. crocea has grown quickly in the past two decades, and it became the top mariculture fish in China with an annual production of 177,640 tons in 20173.

L. crocea is now recognized as an “iconic” marine fish species in China because not only is it a popular food fish in China, it is a representative victim of overfishing and still provides high value fish products supported by the modern large-scale mariculture industry. Due to its impressive economic value in China and importance for marine biodiversity, abundant genome resources and genetic tools for this fish have been developed, including two genetic maps4,5, two draft genomes generated based on Illumina technology6,7 and a recently published draft genome using PacBio sequencing technology8 (which can be accessed via NCBI BioProject database, accession ID PRJNA480121). However, a chromosome-level, highly accurate reference genome is still lacking for L. crocea hindering genome-scale genetic breeding, conservation and restocking evaluation for sustainable aquaculture of L. crocea.

In this report, we provided chromosome-level reference genome sequences of L. crocea combining the PacBio single molecule sequencing technique (SMRT) and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technologies.

In addition, we also produced a chromosome-level reference genome of Takifugu bimaculatus9, which is also cultured as an important food fish in China, via almost the same approach. Both genomes were assembled with high quality, confirming the stability and suitability of this approach for marine fishes. The availability of a fully sequenced and annotated genome is essential to support basic genetic studies and will be helpful to develop genome-scale selective breeding strategies for these important mariculture species.

Methods

Sample collection, library construction and sequencing

A healthy female large yellow croaker belonging to the F1 generation of the “Fufa I” strain was collected from the State Key Laboratory of Large Yellow Croaker Breeding at Ningde, Fujian Province, China, and white muscle samples were collected. The muscle samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for 30 min and then stored at −80 °C. For high-molecular-weight (HMW) genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction, frozen samples were lysed in SDS digestion buffer with proteinase K. Then, the lysates were purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK) to obtain HMW gDNA. Meanwhile, normal-molecular-weight (NMW) gDNA was extracted from the same samples using the DNeasy 96 Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Shanghai, China).

A whole-genome shotgun sequencing strategy was employed for genome size estimation and polishing of preliminary contigs. An Illumina library with 250 bp insert size was constructed from NMW gDNA using the standard protocol provided by Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA), and paired-end sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform with a read length of 2 × 150 bp. Finally, 105.23 Gb raw reads were generated. All reads containing adaptor sequences were discarded first. After that, uncertain bases (represented by “N”) and low-quality bases (Q < 5) were trimmed from the remaining Illumina reads using SolexaQA ++ 10 (version v.3.1.7.1). After trimming, there was a total of 105.01 Gb reads longer than 30 bp remaining, and these were retained as clean reads and used in genome size estimation and preliminary contig polishing (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of obtained data using multiple sequencing technologies.

| Library Type | Insert Size (bp) | Raw Data (Gb) | Clean Data (Gb) | Average Read Length of Raw Reads (bp) | Sequencing Coverage (X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 250 | 105.23 | 105.01 | 150 | 148.54 |

| PacBio | 20,000 | 80.61 | — | 8,530.75 | 113.78 |

| Hi-C | — | 119.15 | 58.97 | 150 | 168.18 |

| Total | — | 304.99 | — | — | 430.50 |

Note: The genome size of L. crocea used to calculate sequencing coverage was 708.47 Mbp, which was estimated using a K-mer analysis of the short reads.

HWM gDNA was used in DNA template preparation for sequencing on the PacBio System following the “Template Preparation and Sequencing Guide” provided by Pacific Biosciences (Menlo Park, CA, USA). The main steps were as follows: extracted DNA was first sheared into large fragments (10 Kbp on average) and then purified and concentrated using AMPure PB beads; DNA damage and ends induced in the shearing step were repaired; blunt hairpins were subsequently ligated to the repaired fragment ends; prior to sequencing, the primer was annealed to the SMRTbell template, and then, DNA polymerase was bound to the annealed templates; finally, DNA sequencing polymerases were bound to the primer-annealed SMRTbell templates.

After sequencing, a total of 9.45 K (80.61 Gbases) long reads were generated from the PacBio SEQUEL platform. The average length and N50 length of these reads were 8,530.75 bp and 12,624 bp, respectively. The genome size of L. crocea was estimated to be 708.47 Mbp using K-mer analysis, and the average sequencing coverage was estimated as 113.78X (Table 1).

Hi-C sequencing was performed parallel to the PacBio sequencing. We used formaldehyde to fix the conformation of the HMW gDNA. Then, the fixed DNA was sheared with MboI restriction enzyme. The 5′ overhangs induced in the shearing step were repaired using biotinylated residues. Following the ligation of blunt-end fragments in situ, the isolated DNA was reverse-crosslinked, purified, and filtered to remove biotin-containing fragments. Subsequently, DNA fragment end repair, adaptor ligation, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed successively. In the end, sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform and yielded a total of 119.15 Gb paired-end reads, with an average sequencing coverage of 168.18X (Table 1).

De novo assembly of the L. crocea genome

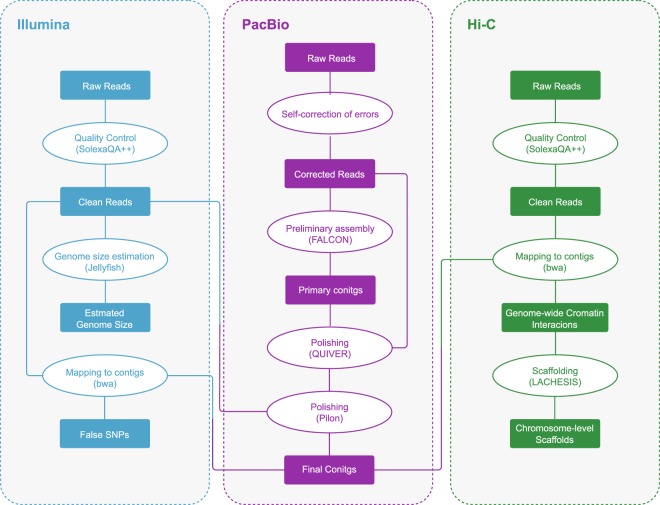

In summary, as shown in Fig. 1, reads generated from three different types of libraries were used in three different assembly stages separately: Illumina sequencing data were used in estimation of genome size and polishing of preliminary contigs; PacBio sequencing data were used for preliminary contig assembly; and Hi-C reads were used in chromosome-level scaffolding.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the complete genome assembly pipeline.

The read pairs generated from the small-insert genomic DNA libraries were filtered out if the proportion of “N” sites exceeded 10%, number of low-quality bases exceeded 75 or the reads were polluted by adaptor sequences. Then, all clean Illumina reads were used to generate 17-mers with a window-sliding-like method. Accordingly, there were 417 different 17-mers. After calculating the depth distribution of these 17-mers using Jellyfish11 (v2.1.3), we could estimate the genome size using Lander/Waterman’s equations:

| 1 |

| 2 |

In these equations, L is read length (150 for Illumina reads), Nbase and N17-mer are counts of bases and 17-mers respectively; Cbase and Ck-mer are expected coverage depths of bases and 17-mers, respectively; estimated genome size is represented by Gest. As a result, the genome size of L. crocea was estimated to be approximately 708.47 Mbp.

Long reads generated from the PacBio SEQUEL platform containing adaptor sequences or with a quality value lower than 20 (corresponding to a 1% error rate) were filtered out. The remaining reads were subsequently further processed by self-correction to address sequencing errors using Falcon12 (version 1.8.2). Thereafter, genome assembly based on these error-corrected reads was processed in three stages: detection of overlaps among input reads and assemble the final string graph13 using the Falcon pipeline; calling of highly accurate consensus sequences based on PacBio reads using quiver14 (version 2.1.0); and polishing the preliminary contigs with Illumina reads using pilon15 (version 1.21). Finally, we obtained a newly assembled genome of L. crocea containing 1,591 contigs with a total length of 723.86 Mb and a contig N50 length of 2.83 Mb (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the L. crocea genome assembly and structural annotation.

| Genome Assembly | |

| Contig N50 length (Mbp) | 2.83 |

| Number of conitgs longer than N50 | 68 |

| Contig N90 size (Kbp) | 0.26 |

| Number of conitgs longer than N90 | 376 |

| Number of conitgs | 1,591 |

| Maximum contig length (Mbp) | 11.8 |

| Median contig length (Mbp) | 0.64 |

| Total contig length (Mbp) | 723.86 |

| Structural Annotation | |

| Number of protein-coding genes | 23,172 |

| Number of unannotated genes | 73 |

| Average transcript length (bp) | 11,839.98 |

| Average exons per gene | 9.27 |

| Average exon length (bp) | 158.16 |

| Average CDS length (bp) | 1,465.51 |

| Average intron length (bp) | 1,255.04 |

To obtain chromosome-level scaffolds, Hi-C reads were filtered in the same way as we filtered the short-insert library reads and subsequently mapped to de novo assembled contigs to construct contacts among the contigs using bwa16 (version 0.7.17) with the default parameters. BAM files containing Hi-C linking messages were processed by another round of filtering, in which reads were removed if they were not mapped to the reference genome within 500 bp from the nearest restriction enzyme site. Then, LACHESIS17 (version 2e27abb) was used for ultra-long-range scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies using the signal of genomic proximity provided by the Hi-C data. In this step, all parameters were set to defaults except that CLUSTER_N, CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES and ORDER_MIN_N_RES_IN_SHREDS were set to 24, 80 and 10, respectively. The parameter CLUSTER_N was used to specify the number of chromosomes. For large yellow croaker, this number was determined to be 24 in previous studies5,18,19. Ultimately, we obtained 24 chromosome-level scaffolds constructed from 548 contigs with a total length of 668.67 Mb (92.48% of the total length of all contigs) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Detailed results of chromosome-level scaffolding using Hi-C technology.

| Chromosomes | Length (Mbp) | Number of Contigs |

|---|---|---|

| Chr1 | 34.89 | 34 |

| Chr2 | 24.81 | 19 |

| Chr3 | 28.07 | 17 |

| Chr4 | 29.96 | 22 |

| Chr5 | 33.77 | 25 |

| Chr6 | 24.87 | 16 |

| Chr7 | 31.52 | 27 |

| Chr8 | 32.80 | 24 |

| Chr9 | 24.26 | 18 |

| Chr10 | 27.49 | 16 |

| Chr11 | 34.65 | 24 |

| Chr12 | 26.70 | 25 |

| Chr13 | 16.24 | 24 |

| Chr14 | 29.81 | 21 |

| Chr15 | 27.79 | 19 |

| Chr16 | 20.01 | 23 |

| Chr17 | 25.06 | 18 |

| Chr18 | 32.81 | 20 |

| Chr19 | 29.92 | 30 |

| Chr20 | 32.24 | 39 |

| Chr21 | 27.85 | 20 |

| Chr22 | 27.44 | 11 |

| Chr23 | 23.57 | 27 |

| Chr24 | 22.13 | 29 |

| Linked Total | 668.67 | 548 |

| Unlinked Total | 54.39 | 1,043 |

| Linked Percent | 92.48 | 34.44 |

| Total | 723.06 | 1,591.00 |

Gene annotation

To obtain a fully annotated L. crocea genome, three different approaches were employed to predict protein-coding genes. Ab intio gene prediction was performed on the repeat-masked L. crocea genome assembly using Augustus20 (version 2.5.5), GlimmerHMM21 (version 3.0.1), Geneid22 (version 1.4.4) and GenScan23 (version 1.0). Furthermore, homology-based prediction was performed using protein sequences of three common model species [Danio rerio (Dre)24, Homo sapiens (Hsa)25, and Mus musculus (Mmu)26] downloaded from European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) and two related species [Oreochromis niloticus (Oni)27 and Notothenia coriiceps (Nco)28]. Subsequently, these protein sequences were mapped onto the generated assembly using blat29 (version 35) with a cut off of e-value ≤ 1e−5. GeneWise30 (version 2.2.0) was employed to align the homologs in the L. crocea genome against the other species for gene structure prediction. In addition, we also applied transcriptome-based prediction by using existing RNA-seq data generated from various tissues including gonad31, spleen32, liver33, muscle34, skin35, brain36 and embryos in different developmental stages37 (Table 4). The RNA-seq reads were mapped onto the genome assembly using TopHat38 (version 2.0.13), and the structures of all transcribed genes were predicted by Cufflinks39 (version 2.2.1) with the default parameters. The predicted gene sets generated from these three approaches were then integrated to produce a non-redundant gene set using EvidenceModeler40 (version 1.1.0). PASA41 (version 2.0.2) was then used to annotate the gene structures. As a result, a total of 23,172 protein-coding genes were predicted and subsequently annotated. The average number of exons per gene, and average CDS length were 9,27 and 1465.51 bp, respectively. To identify candidate non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes, we aligned genome sequences against the Rfam database42 (version 12.0) using BLASTN to search for homologs. As a result, a total of 7262 ncRNA genes were predicted (1246 miRNAs, 3517 tRNAs, 1758 rRNAs and 741 snRNAs, Fig. 2 and Table 5).

Table 4.

List of RNA-seq datasets used for gene structural prediction.

| Run | Tissue | Sample Name | Study | BioProject | MBases | Load Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRR6474596 | gonad | Male5 | SRP128079 | PRJNA368644 | 3,824 | 2018/1/15 |

| SRR6474594 | gonad | Female3 | SRP128079 | PRJNA368644 | 4,845 | 2018/1/15 |

| SRR6474588 | gonad | Female5 | SRP128079 | PRJNA368644 | 4,052 | 2018/1/15 |

| SRR6474586 | gonad | Male4 | SRP128079 | PRJNA368644 | 3,742 | 2018/1/15 |

| SRR5121288 | embryo | pharyngula | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,399 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121287 | embryo | gastrulation | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,392 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121286 | embryo | 1_cell_embryo | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,567 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121204 | embryo | blastula_L1 | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,695 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121203 | embryo | 256_cell_embryo_L1 | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,730 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121202 | embryo | 16_cell_embryo_L1 | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,688 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121194 | embryo | 8_cell_embryo_L1 | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,425 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5121193 | embryo | 2_cell_embryo_L1 | SRP095312 | PRJNA357970 | 4,495 | 2016/12/23 |

| SRR5000825 | spleen | BS24h | SRP092778 | PRJNA340054 | 5,229 | 2016/11/7 |

| SRR5000824 | spleen | BS0h | SRP092778 | PRJNA340054 | 5,278 | 2016/11/7 |

| SRR3711298 | liver | The raw sequence reads of Larimichthys crocea liver | SRP076957 | PRJNA326556 | 4,758 | 2016/6/27 |

| SRR3711297 | liver | The raw sequence reads of Larimichthys crocea liver | SRP076957 | PRJNA326556 | 4,878 | 2016/6/27 |

| SRR2984347 | skin | stress_0.5h_1 | SRP066525 | PRJNA303096 | 2,963 | 2015/12/11 |

| SRR2984346 | skin | control | SRP066525 | PRJNA303096 | 2,913 | 2015/12/11 |

| SRR2473991 | muscle | GSM1890206 | SRP063956 | PRJNA296537 | 5,073 | 2015/9/21 |

| SRR2473990 | muscle | GSM1890205 | SRP063956 | PRJNA296537 | 6,310 | 2015/9/21 |

| SRR1509885 | mixture | a composite sample of large yellow croaker | SRP044199 | PRJNA254539 | 6,122 | 2014/7/10 |

| SRR1284627 | brain | GSM1385502 | SRP041934 | PRJNA246784 | 6,144 | 2015/12/29 |

| SRR1284623 | brain | GSM1385498 | SRP041934 | PRJNA246784 | 4,399 | 2015/9/13 |

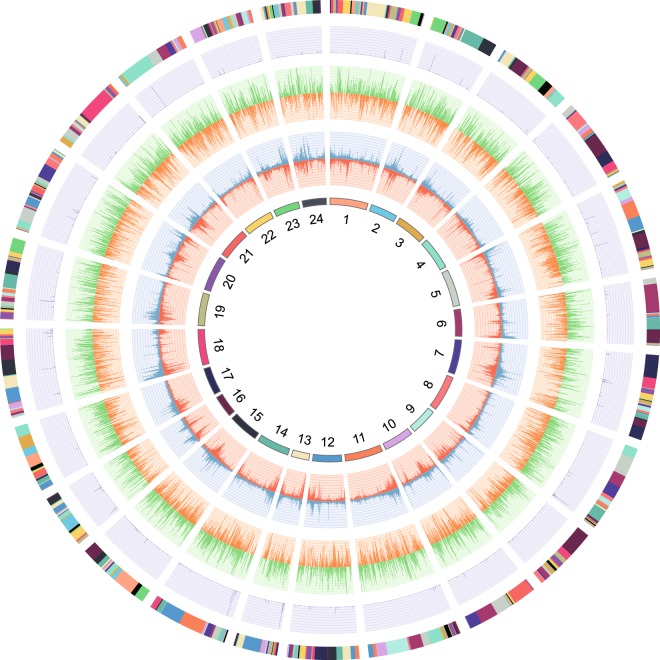

Fig. 2.

Circos plot of 24 chromosome-level scaffolds, representing annotation results of genes, ncRNAs and transposable elements on these scaffolds. The tracks from inside to outside are: 24 chromosome-level scaffolds, gene abundance of positive strand (red), gene abundance of negative strand (blue), TE abundance of positive strand (orange), TE abundance of negative strand (green), ncRNA abundance of both strands, and contigs that comprised the scaffolds (adjacent contigs on a scaffold are shown in different colours).

Table 5.

Detailed results of ncRNA annotation.

| Type | Copy | Average Length (bp) | Total Length (bp) | Proportion in Genome (‰) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | 1,246 | 100.90 | 125,725 | 0.17 | |

| tRNA | 3,517 | 75.58 | 265,811 | 0.37 | |

| rRNA | 18S | 68 | 227.37 | 15,461 | 0.02 |

| 28S | 70 | 208.07 | 14,565 | 0.02 | |

| 5.8S | 1 | 45 | 45 | 0.00 | |

| 5S | 1,619 | 111.3 | 180,190 | 0.25 | |

| Subtotal | 1,758 | 119.6 | 210,261 | 0.29 | |

| snRNA | CD-box | 153 | 118.72 | 18,164 | 0.03 |

| HACA-box | 119 | 156.36 | 18,607 | 0.03 | |

| Splicing | 469 | 124.25 | 58,271 | 0.08 | |

| Subtotal | 741 | 129.85 | 95,042 | 0.14 | |

| Total | 72 | 95.96 | 696,839 | 0.97 | |

Note: The genome size of L. crocea was estimated to be 708.47 Mbp by genome K-mer analysis.

Gene function annotations were conducted against the NCBI nr and SwissProt protein databases, and homologs were called with E values of <1 × 10−5. The functional classification of Gene Ontology (GO) categories was performed using the InterProScan program43 (version 5.26). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)44 pathway annotation analysis was performed using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS)45. As a result, a total of 23,323 genes could be annotated, accounting for 99.7% of all predicted genes (Fig. 2, and Table 2).

Repetitive element characterization

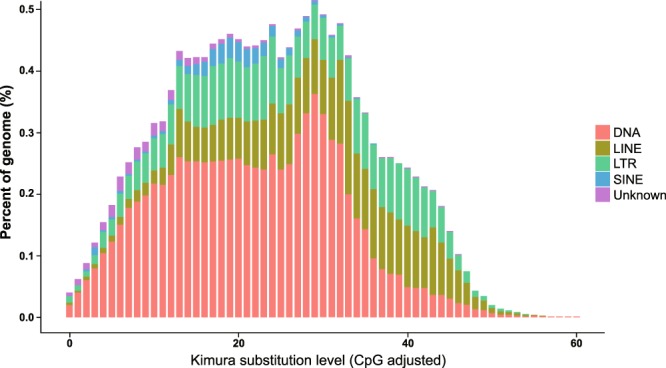

We employed two approaches to detect repeat sequences in the L. crocea genome. First, we used Tandem Repeats Finder46 (version 4.04), Piler47 (version 1.0), LTR_FINDER48 (version 1.0.2), RepeatModeler49 (version 1.04) and RepeatScout50 (version 1.0.2) to detect various kinds of repeat sequences in the L. crocea genome synchronously. The results were then integrated as a de novo non-redundant repeat sequence library by USEARCH51 (version 10.0.240). Subsequently, the library was annotated using RepeatMasker49 (version 3.2.9) based on Repbase TE52 (version 14.04) to discriminate between known and novel transposable elements (TEs). In another approach, genome sequences were mapped on Repbase TE52 (version 14.04) using RepeatProteinMask49 (version 3.2.2), a Perl script included in RepeatMasker, to detect transposable element (TE) proteins in L. crocea genome. After combining the results of the two approaches and removing the redundancy, ~26.13% of the L. crocea genome with a total length of 189.3 Mb were identified as repetitive elements, including 69.1 Mb (9.54%) of DNA transposons, 51.4 Mb (7.09%) of long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) and 52.4 (7.24%) of long terminal repeats (LTRs) (Table 6). A Perl script createRepeatLandscape.pl supplied with RepeatMasker was used to visualize the divergence distribution of TEs in the L. crocea genome (Fig. 3). The numbers and lengths of contigs comprising each chromosome were shown in the outermost track of a Circos53 plot.

Table 6.

Detailed classification of repeat sequences.

| Type | De novo | TE proteins | Combined TEs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (Mbp) | Proportion in Genome (%) | Length (Mbp) | Proportion in Genome (%) | Length (Mbp) | Proportion in Genome (%) | |

| DNA | 66.39 | 9.17 | 5.58 | 0.77 | 69.11 | 9.54 |

| LINE | 45.38 | 6.26 | 14.50 | 2.00 | 51.37 | 7.09 |

| SINE | 3.45 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.45 | 0.48 |

| LTR | 51.19 | 7.07 | 9.51 | 1.31 | 52.41 | 7.24 |

| Simple Repeat | 16.86 | 2.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.86 | 2.33 |

| Unknown | 11.85 | 1.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 11.85 | 1.64 |

| Total | 183.50 | 25.33 | 29.51 | 4.07 | 189.27 | 26.13 |

Note: “De novo” represents the de novo identified transposable elements using RepeatMasker, RepeatModeler, RepeatScout, and LTR_FINDER. “TE proteins” indicates homologous transposable elements in Repbase identified with RepeatProteinMask, while “Combined TEs” refers to the combined results of transposable elements identified in these two ways. “Unknown” represents transposable elements that could not be classified by RepeatMasker.

Fig. 3.

Divergence distribution of TEs in the L. crocea genome.

Data Records

This whole genome shotgun sequencing project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession RQIN00000000. The version described in this paper is version RQIN0100000054.

Genome assembly and annotation have also been deposited at Figshare55.

All sequencing data, including the PacBio long reads, Illumina short reads and Hi-C reads, have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRP16905756.

The existing RNA-seq datasets are all available in NCBI SRA, with the accession numbers listed in Table 4 31–37.

Technical Validation

DNA sample quality

DNA quality was assessed using 1% agarose gel.

Illumina libraries

Ready-to-sequence Illumina libraries were quantified by qPCR using the KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina Libraries (KapaBiosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA), and library profiles were evaluated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Completeness and accuracy of the assembly

The completeness and accuracy of the assembly were further assessed in multiple ways. First, the reads from the short-insert library were re-mapped onto the assembly using bwa16 (version 0.7.17). As a result, 97.61% of the reads were accurately mapped with a coverage of 99.89%. Then Genome Analysis Toolkit57 (GATK) (version 4.0.2.1) was applied for SNP discovery and finally identified 3,739.45 K SNPs, including 3,735.88 K heterozygous SNPs and 3568 homozygous SNPs (Table 7). The extremely low proportion of homozygous SNPs suggests the high accuracy of this assembly. The assembly completeness was evaluated using Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach (CEGMA) software58 (version 2.3) based on an appropriate reference gene set, core vertebrate genes (CVG)59. There were 232 genes out of the complete set of 233 genes (99.57%) covered by the assembly, suggesting the high completeness of the draft genome of L. crocea (Table 7). Subsequently, Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) software60 (version 1.22) was executed using actinopterygii_odb9 database to assess the predicted gene set. The genome mode result showed that 97.1% of all 4584 BUSCOs were assembled, including 93.7% and 3.3% of all BUSCOs were completely and partially assembled, also implying a high level of completeness for the de novo assembly (Table 7). In addition, the results generated with protein mode based on all predicted genes showed that 91.2% of all 4584 BUSCOs were assembled, including 11.9% of all BUSCOs that were partially predicted (Table 7).

Table 7.

Details of accuracy and completeness validation of genome assembly.

| Illumina Reads Mapping | ||

| Mapping ratio | 97.61% | |

| Mapping coverage | 99.89% | |

| Number of heterozygous SNPs | 3,735,880 | |

| Number of homozygous SNPs | 3568 | |

| CEGMA | ||

| Total number of reference genes | 233 | |

| Number of completely assembled CEGs | 231 | |

| Proportion of completely assembled CEGs (%) | 99.14 | |

| Number of assembled CEGs | 232 | |

| Proportion of assembled CEGs (%) | 99.57 | |

| BUSCO (genome mode) | Number | Proportion (%) |

| All orthologues used | 4584 | 100.00 |

| Complete and fragmented orthologues | 4419 | 97.1 |

| Missing orthologues | 135 | 2.9 |

| BUSCO (protein mode) | Number | Proportion (%) |

| All orthologues used | 4584 | 100.00 |

| Complete and fragmented orthologues | 4182 | 91.2% |

| Missing orthologues | 402 | 8.8 |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the State Key Laboratory of Large Yellow Croaker Breeding (Fujian Fuding Seagull Fishing Food Co., Ltd) (Nos. LYC2017ZY01 & LYC2017RS05), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos 20720180123, 20720160110 & 20720190102), the Science and Technology Platform Construction of Fujian Province (No. 2018N2005), the Local Science and Technology Development Project Guide by the Central Government (No. 2017L3019), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFC1406305), China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-47) and the Major Special Projects of Fujian Province (No. 2016NZ0001). Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author Contributions

P.X. conceived the study. B.C. and Z.Z. performed bioinformatics analysis. Q.K. and F.P. collected the samples. Z.Z., Y.W. and H.B. extracted the genomic DNA. B.C. and P.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Code Availability

The execution of this work involved using many software tools. To allow readers to repeat any steps involved in genome assembly and genome annotation, the settings and parameters were provided below:

Genome assembly:

(1) Falcon: all parameters were set to the defaults; (2) quiver: all parameters were set to the defaults; (3) pilon: all parameters were set to the defaults; (4) LACHESIS: RE_SITE_SEQ = AAGCTT, USE_REFERENCE = 0, DO_CLUSTERING = 1, DO_ORDERING = 1, DO_REPORTING = 1, CLUSTER_N = 24, CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 300, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 4, CLUSTER_NONINFORMATIVE_RATIO = 10, REPORT_EXCLUDED_GROUPS = −1;

Genome annotation:

(1) RepeatProteinMask: -noLowSimple -pvalue 0.0001 -engine wublast; (2) RepeatMasker: -a -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 1; (3) LTR_FINDER: -C -w 2; (4) RepeatModeler: -database genome -engine ncbi -pa 15; (5) RepeatScout: all parameters were set to the defaults; (6) TRF: matching weight = 2, mismatching penalty = 7, INDEL penalty = 7, match probability = 80, INDEL probability = 10, minimum alignment score to report = 50, maximum period size to report = 2000, -d –h; (7) Augustus:–extrinsicCfgFile–uniqueGeneId = true–noInFrameStop = true–gff3 = on–genemodel = complete–strand = both; (8) GlimmerHMM: -f –g; (9) Genscan: -cds; (10) Geneid: -P -v -G -p geneid; (11) Genewise: -trev -genesf -gff –sum; (12) BLAST: -p tblastn -e 1e-05 -F T -m 8 -d; (13) EVidenceModeler: G genome.fa -g denovo.gff3 –w weight_file -e transcript.gff3 -p protein.gff3–min_intron_length 20 (14) PASA: all parameters were set to the defaults.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2018 - Meeting the sustainable development goals (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2018).

- 2.Zhao, S., Wang, R. & Liu, X. Reasons of Exhaustion of Resources of Pseudosciaenacrocea in Zhoushan Fishing Ground and the Measures of Protection and Proliferation. Journal of Zhejiang Ocean University2, 160–165 (2002).

- 3.Ministry of Agricultrure and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. 2018 China Fishery Statistical Yearbook (China Agriculture Press, 2018).

- 4.Ye H, Liu Y, Liu X, Wang X, Wang Z. Genetic Mapping and QTL Analysis of Growth Traits in the Large Yellow Croaker Larimichthys crocea. Mar Biotechnol. 2014;16:729–738. doi: 10.1007/s10126-014-9590-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ning Y, et al. A genetic map of large yellow croaker Pseudosciaena crocea. Aquaculture. 2007;264:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.12.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ao Jingqun, Mu Yinnan, Xiang Li-Xin, Fan DingDing, Feng MingJi, Zhang Shicui, Shi Qiong, Zhu Lv-Yun, Li Ting, Ding Yang, Nie Li, Li Qiuhua, Dong Wei-ren, Jiang Liang, Sun Bing, Zhang XinHui, Li Mingyu, Zhang Hai-Qi, Xie ShangBo, Zhu YaBing, Jiang XuanTing, Wang Xianhui, Mu Pengfei, Chen Wei, Yue Zhen, Wang Zhuo, Wang Jun, Shao Jian-Zhong, Chen Xinhua. Genome Sequencing of the Perciform Fish Larimichthys crocea Provides Insights into Molecular and Genetic Mechanisms of Stress Adaptation. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11(4):e1005118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu, C. W. et al. The draft genome of the large yellow croaker reveals well-developed innate immunity. Nat Commun5, 5227 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.2018. NCBI BioProject. PRJNA480121

- 9.Zhou, Z. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of Takifugu bimaculatus genome using PacBio and Hi-C technologies. Sci Data, 10.1038/s41597-019-0195-2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A. & Biggs, P. J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. Bmc Bioinformatics11, 485 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Marcais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pendleton M, et al. Assembly and diploid architecture of an individual human genome via single-molecule technologies. Nat Methods. 2015;12:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers EW. The fragment assembly string graph. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 2):ii79–85. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin CS, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker Bruce J., Abeel Thomas, Shea Terrance, Priest Margaret, Abouelliel Amr, Sakthikumar Sharadha, Cuomo Christina A., Zeng Qiandong, Wortman Jennifer, Young Sarah K., Earl Ashlee M. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korbel JO, Lee C. Genome assembly and haplotyping with Hi-C. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1099–1101. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, Z., Wang, Z., Liu, X., Jiang, Y. & Cai, M. J. J. F. C. Area and physical length of metaphase chromosomes in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). J Fish China38, 632–637 (2014).

- 19.Xiao, S. J. et al. Gene map of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) provides insights into teleost genome evolution and conserved regions associated with growth. Sci Rep5, 18661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Stanke M, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W465–467. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parra G, Blanco E, Guigo R. GeneID in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2000;10:511–515. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA11776

- 25.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA31257

- 26.2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA20689

- 27.Brawand D, et al. The genomic substrate for adaptive radiation in African cichlid fish. Nature. 2014;513:375–381. doi: 10.1038/nature13726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin SC, et al. The genome sequence of the Antarctic bullhead notothen reveals evolutionary adaptations to a cold environment. Genome Biol. 2014;15:468. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent WJ. BLAT - The BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP128079

- 32.2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP092778

- 33.2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP076957

- 34.2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP063956

- 35.2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP066525

- 36.2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP041934

- 37.2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP095312

- 38.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology. 2010;28:511–U174. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas Brian J, Salzberg Steven L, Zhu Wei, Pertea Mihaela, Allen Jonathan E, Orvis Joshua, White Owen, Buell C Robin, Wortman Jennifer R. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biology. 2008;9(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nawrocki EP, et al. Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D130–D137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edgar RC, Myers EW. PILER: identification and classification of genomic repeats. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i152–158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2009;Chapter 4(Unit 4):10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:I351–I358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bao W, Kojima KK, Kohany O. Repbase Update, a database of repetitive elements in eukaryotic genomes. Mob DNA. 2015;6:11. doi: 10.1186/s13100-015-0041-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krzywinski M, et al. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu P, 2018. Larimichthys crocea breed Fufa I, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank. RQIN00000000

- 55.Chen B, 2019. The sequence and de novo assembly of Larimichthys crocea genome using PacBio and Hi-C technologies. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP169057

- 57.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hara, Y. et al. Optimizing and benchmarking de novo transcriptome sequencing: from library preparation to assembly evaluation. Bmc Genomics16, 977 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2018. NCBI BioProject. PRJNA480121

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA11776

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA31257

- 2018. European Nucleotide Archive. PRJNA20689

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP128079

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP092778

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP076957

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP063956

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP066525

- 2015. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP041934

- 2016. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP095312

- Xu P, 2018. Larimichthys crocea breed Fufa I, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. GenBank. RQIN00000000

- Chen B, 2019. The sequence and de novo assembly of Larimichthys crocea genome using PacBio and Hi-C technologies. figshare. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2018. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP169057

Data Availability Statement

The execution of this work involved using many software tools. To allow readers to repeat any steps involved in genome assembly and genome annotation, the settings and parameters were provided below:

Genome assembly:

(1) Falcon: all parameters were set to the defaults; (2) quiver: all parameters were set to the defaults; (3) pilon: all parameters were set to the defaults; (4) LACHESIS: RE_SITE_SEQ = AAGCTT, USE_REFERENCE = 0, DO_CLUSTERING = 1, DO_ORDERING = 1, DO_REPORTING = 1, CLUSTER_N = 24, CLUSTER_MIN_RE_SITES = 300, CLUSTER_MAX_LINK_DENSITY = 4, CLUSTER_NONINFORMATIVE_RATIO = 10, REPORT_EXCLUDED_GROUPS = −1;

Genome annotation:

(1) RepeatProteinMask: -noLowSimple -pvalue 0.0001 -engine wublast; (2) RepeatMasker: -a -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 1; (3) LTR_FINDER: -C -w 2; (4) RepeatModeler: -database genome -engine ncbi -pa 15; (5) RepeatScout: all parameters were set to the defaults; (6) TRF: matching weight = 2, mismatching penalty = 7, INDEL penalty = 7, match probability = 80, INDEL probability = 10, minimum alignment score to report = 50, maximum period size to report = 2000, -d –h; (7) Augustus:–extrinsicCfgFile–uniqueGeneId = true–noInFrameStop = true–gff3 = on–genemodel = complete–strand = both; (8) GlimmerHMM: -f –g; (9) Genscan: -cds; (10) Geneid: -P -v -G -p geneid; (11) Genewise: -trev -genesf -gff –sum; (12) BLAST: -p tblastn -e 1e-05 -F T -m 8 -d; (13) EVidenceModeler: G genome.fa -g denovo.gff3 –w weight_file -e transcript.gff3 -p protein.gff3–min_intron_length 20 (14) PASA: all parameters were set to the defaults.