Abstract

TRPM8 is a member of the transient receptor potential ion channel family where it functions as a cold and pain sensor in humans and other higher organisms. Previous studies show that TRPM8 requires the signaling phosphoinositide lipid PIP2 to function. TRPM8 function is further regulated by other diverse mechanisms, including the small modulatory membrane protein PIRT (phosphoinositide regulator of TRP). Like TRPM8, PIRT also binds PIP2 and behavioral studies have shown that PIRT is required for normal TRPM8-mediated cold-sensing. To better understand the molecular mechanism of PIRT regulation of TRPM8, solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy was used to assign the backbone resonances of full-length human PIRT and investigate the direct binding of PIRT to PIP2 and the human TRPM8 S1-S4 transmembrane domain. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) binding studies validate the NMR results and identify a competitive PIRT interaction between PIP2 and the TRPM8 S1-S4 domain. Computational PIP2 docking to a human TRPM8 comparative model was performed to help localize where PIRT may bind TRPM8. Taken together, our data suggest a mechanism where TRPM8, PIRT, and PIP2 form a regulatory complex and PIRT modulation of TRPM8 arises, at least in part, by regulating local concentrations of PIP2 accessible to TRPM8.

Subject terms: Transient receptor potential channels, Ion transport, Permeation and transport, Solution-state NMR

Introduction

TRP ion channels are involved in diverse physiological and pathophysiological processes. Functionally, most TRP ion channels are polymodally modulated by various stimuli. TRPM8 functions in human sensory physiology as the primary cold sensor and is implicated in other physiological roles including pain, cancer, and obesity1–5. It is a weakly voltage sensitive, nonselective calcium-permeable cation channel that gates in response to physiologically relevant cold temperatures6, cooling chemicals like menthol7, and is sensitive to many other stimuli8. TRPM8 sensitivity requires the lipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to potentiate the channel for activation9–11 and TRPM8 function is further regulated by modulatory proteins, including the membrane protein PIRT (phosphoinositide interacting regulator of TRPs)12–16. PIRT modulation of TRPM8 displays an emerging trend of species-dependent functional diversity found in orthologous TRP channels8,12. For the mouse orthologs, PIRT increases TRPM8 sensitivity to cold, menthol, and voltage. Whereas, for the human orthologs PIRT attenuates equivalent TRPM8 mediated currents8,12–14,17–21.

PIRT is a phosphoinositide binding membrane protein with two transmembrane (TM) helices and intracellular N- and C-termini. It is expressed primarily in the dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia of the peripheral nervous system22 and appears to modulate thermosensing through apparent interactions with the cold-sensing TRPM812–14 and the heat-sensing TRPV1 ion channels12,22–24. Additionally, PIRT‒TRPV1 interactions have also been functionally implicated in histaminergic and nonhistaminergic pruritus (itch)25, regulation of neuropathic pain23,26, and uterine contraction pain23,25,26. Beyond TRP channel modulation, PIRT has been implicated in modulating P2X purinoreceptors where it is coexpressed with P2X2 channels in the enteric nervous system27, has been reported to inhibit P2X3 currents to reduce bladder overactivity28, and was recently implicated in influencing metabolism in mice29. Despite emerging modulatory roles, little is currently known about the molecular mechanisms that underlie ion channel regulation by PIRT.

To probe the molecular mechanism of human TRPM8 (hTRPM8) modulation by PIRT, we used solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, microscale thermophoresis (MST), and Rosetta computational techniques to isolate how human PIRT (hPIRT), PIP2, and hTRPM8 interact. With solution NMR, we assigned the backbone resonances from full-length hPIRT and used solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement studies to experimentally identify its general membrane topology. With the assigned resonances, we used NMR-detected titrations to isolate specific hPIRT residues that bind PIP2 and the human TRPM8 ligand-sensing domain (hTRPM8-S1S4). Our NMR binding studies identify several hPIRT residues that bind both the hTRPM8-S1S4 and PIP2, which is suggestive of a competitive interaction. Using MST, we validate the NMR-detected binding studies and show that hPIRT displays classical competition with reduced affinity (i.e., a higher Kd value) for hTRPM8-S1S4 when PIP2 is present at saturating conditions.

To contextualize the experimental hPIRT binding results we used the recent apo avian TRPM8 cryo-EM structure17 to generate hTRPM8 transmembrane domain (hTRPM8-TMD, residues 672–1012) homology models using modern Rosetta techniques. We then computationally docked PIP2 to the hTRPM8-TMD to illuminate the potential location of the TRPM8–PIRT–PIP2 ternary complex. From these studies, we propose a mechanism where hPIRT exerts at least partial modulatory control of hTRPM8 by regulating PIP2 accessibility.

Results

Optimization of NMR conditions for biophysical hPIRT studies

The full-length human membrane protein PIRT was optimized for expression and purification from E. coli. This optimization yielded an average of 3 mg of purified hPIRT per liter of M9 minimal media, following a previously established protocol12. The purity and identity of hPIRT were confirmed by SDS-PAGE and trypsin digestion coupled with LC-MS/MS (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Selection of the hPIRT membrane mimic for NMR-based studies was made empirically by screening different detergent and bicelle conditions while monitoring 1H, 15N TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. S2). The optimal NMR protein spectrum typically has narrow linewidths, broad proton resonance dispersion, and unique resonances for most residues in the protein. Based on these criteria, hPIRT was eventually reconstituted in DPC (n-dodecylphosphocholine) for future studies. hPIRT is stable in DPC for weeks and gives relatively well-resolved spectra, for a helical membrane protein.

Far-UV CD and NMR binding studies were performed to validate the suitability of DPC as a membrane mimic. Previous bioinformatic analysis of hPIRT predicts a helical two-span membrane protein22. The far-UV CD spectrum of DPC reconstituted hPIRT (Supplementary Fig. S1) is consistent with an α-helical protein, with spectral minima near 208 nm and 222 nm and a positive maximum near 193 nm. NMR-derived secondary structure analyses (described in detail below) are also consistent with a two-span helical membrane protein (Fig. 1). NMR-detected titrations of hPIRT in DPC micelles with PIP2 and hTRPM8 S1–S4 show saturable binding isotherms (Figs 2 and 3), a hallmark of specific and direct binding. These results indicate that expression and reconstitution of hPIRT in DPC retains a biologically relevant structural conformation; the significance of the affinities are discussed below.

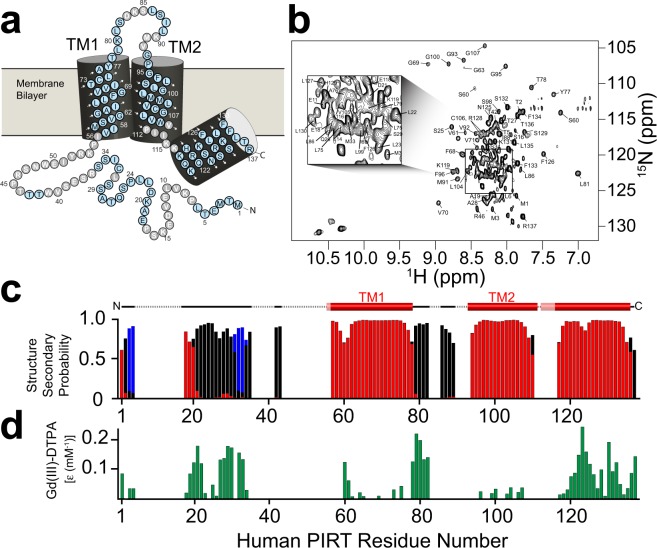

Figure 1.

NMR derived secondary structure and topology of hPIRT. (a) The light blue (gray) colored circles indicate NMR assigned (unassigned) residues. (b) The TROSY-HSQC of hPIRT reconstituted in DPC shows a relatively well-resolved spectrum with dispersion consistent with a α-helical membrane protein. (c) The plot of the consensus TALOS-N predicted hPIRT secondary structure derived from experimental hPIRT Cα, Cβ, and C′ chemical shifts. Red, black, and blue bars indicate the probability of α-helix, loop, and β-sheet respectively. (d) Solvent paramagnetic enhancement in spin relaxation, ε, from Gd(III)-DTPA confirm the hydrophobic nature of the two transmembrane α-helices and the amphipathic nature of the C-terminal α-helix. Larger magnitude values of ε are consistent with solvent accessibility and small magnitude ε values are suggestive of protection from Gd(III)-DTPA relaxation enhancement by the membrane mimic. These results indicate that hPIRT has a relatively unstructured N-terminus, two transmembrane helices, and an amphipathic C-terminal α-helix.

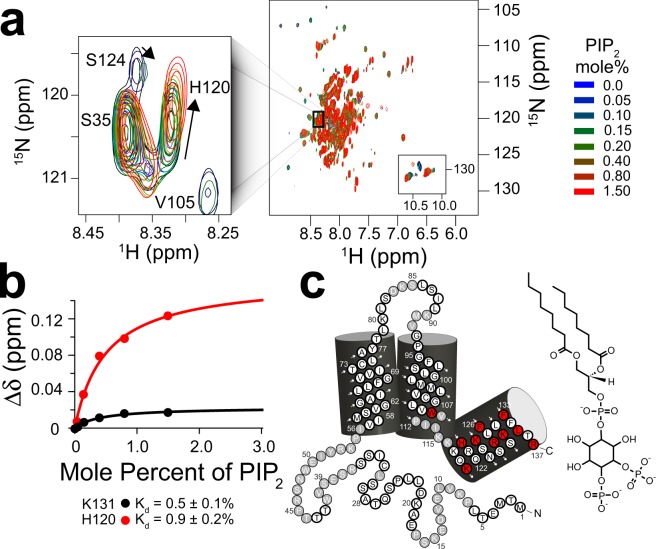

Figure 2.

The PIRT polybasic C-terminal helix binds PIP2. (a) Overlay of eight 15N-TROSY HSQC hPIRT NMR spectra colored as a function of increasing PIP2 concentration. The left inset shows changes in H120 resonance position as the lipid is titrated. (b) Representative chemical shift perturbation (Δδ) titration plots for hPIRT K131 and H120 which are fit to a single binding site model as described in the methods. (c) hPIRT residues that specifically bind PIP2 are highlighted red on the topology plot.

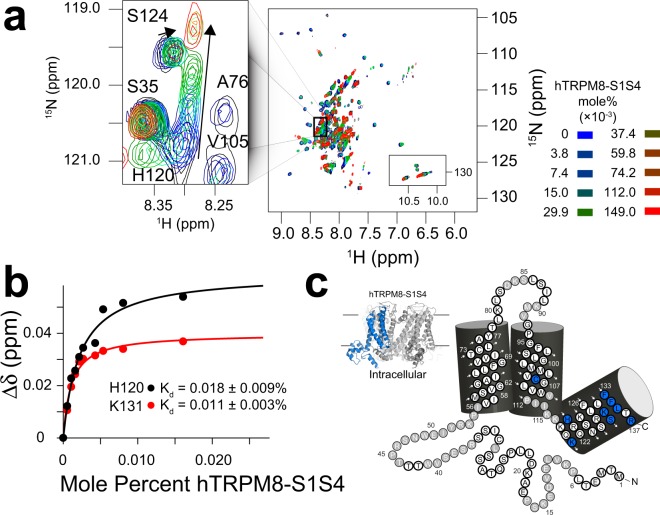

Figure 3.

The PIRT polybasic C-terminal helix binds the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain. Uniformly 15N labeled hPIRT was titrated with unlabeled (14N, NMR silent) hTRPM8-S1S4 and monitored using 15N-TROSY HSQC experiments. (a) Overlay of ten hPIRT NMR spectra as a function of increasing hTRPM8-S1S4 concentration. At about 0.025 mol% hTRPM8-S1S4 the hPIRT H120 change in resonance position (inset) saturates while non-binding residues are generally unperturbed. (b) The chemical shift perturbation was quantified and fit to a standard 1:1 binding model to calculate the affinity (Kd). Representative binding data for H120 and K131 are shown. (c) Individual hPIRT residues that specifically bind to the hTRPM8-S1S4 are mapped onto the hPIRT topology diagram. The hTRPM8-S1S4 is highlighted blue next to the hPIRT topology to emphasize the domain being titrated. These NMR data agree with a previously published study12.

Human PIRT backbone NMR resonance assignment and secondary structure prediction

TROSY 3D NMR experiments were used to assign 68.6% (Fig. 1a) of the hPIRT backbone resonances (15N, 1H, 13Cβ, 13Cα, and 13C′) from a U-13C/15N labeled hPIRT sample in DPC micelles at 40 °C and pH 6.5. Representative assignment data are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The resonance assignments (Fig. 1b) were used as input for TALOS-N30,31, from which secondary structure elements of hPIRT were predicted (Fig. 1c). Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement studies of hPIRT with Gd(III)-DTPA, a hydrophilic paramagnetic probe, were used to experimentally map the hPIRT membrane topology (Fig. 1d)32,33. The data suggest that the start of TM1 is likely near Pro55 and ends at Ala76. TM2 likely begins at Gly93; however, the C-terminal end of TM2 is not clearly defined in our data. Nonetheless, PsiPred-based bioinformatics predictions suggest that TM2 terminates between Pro112 and Lys11534. After TM2, the remaining C-terminal residues comprise an amphipathic α-helix (Asp125 to Arg137), as indicated by NMR with the Gd(III)-DTPA paramagnetic probe studies (Fig. 1d). The amphipathic C-terminal helix provides a region that can hug the inner membrane leaflet and allow for interactions at the bilayer interface with lipids or proteins.

Most of the resonance assignments come from the transmembrane helices and the putative C-terminal PIP2 binding pocket, which are DPC-associated and typically less dynamic than loops and soluble regions. Predictions from PsiPred suggest that the hPIRT N-terminus is disordered, which is consistent with the observed NMR spectral overlap that hinders resonance assignment34,35. Further complicating NMR assignment of the N-terminus is that this region includes several proline residues (Pro7, Pro16, Pro23, Pro45, and Pro55) and there are several repeated amino acid stretches (Leu22-Leu23, Ser29-Ser30, Ser34-Ser35, and Thr42-Thr43-Thr44) making the assignment of the N-terminus difficult. Omitting the hPIRT N-terminus and extracellular loop regions, the remainder of the protein is assigned to about 89%. Thus, the putative C-terminal PIP2 binding pocket and the majority of the transmembrane helices have been successfully assigned.

NMR-detected human PIRT titrations with PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain

NMR assignment allows for identification of residue-specific information in NMR-detected binding studies. Thus these studies provide affinity information, identify regions involved in binding, and provide insight into the binding modalities. Saturation of chemical shift perturbation (Δδ) is indicative of specific and direct binding36. NMR-based hPIRT-detected titrations of PIP2 (Fig. 2) and hTRPM8-S1S4 (Fig. 3) identify several hPIRT residues with saturable binding curves.

In membrane protein binding studies, where a ligand strongly partitions into the membrane or membrane mimic, dissociation constants in units of mole percent better reflect the physical constraints of the interaction37,38. Previous studies have estimated that the physiological concentration of PIP2 in the inner leaflet of dorsal root ganglia (DRG) is ca. 1 percent of membrane mass39. NMR-detected hPIRT binding studies of PIP2 show saturable chemical shift perturbation (Fig. 2a,b) for select residues in the intracellular side of TM2 and the C-terminal amphipathic helix (Fig. 2c). The hPIRT affinity for PIP2 (Supplementary Table S2) is in the range of the physiological PIP2 concentration, suggesting a biologically relevant interaction.

We have previously shown that hPIRT directly binds the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain with a stoichiometry of ~1:112. Here we use units of mole percent and hPIRT resonance assignments to further interrogate the hPIRT–hTRPM8-S1S4 interaction (Fig. 3a). From these studies, we identify many hPIRT residues that bind specifically to the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain (Fig. 3b,c).

MST Binding measurements and competition assay

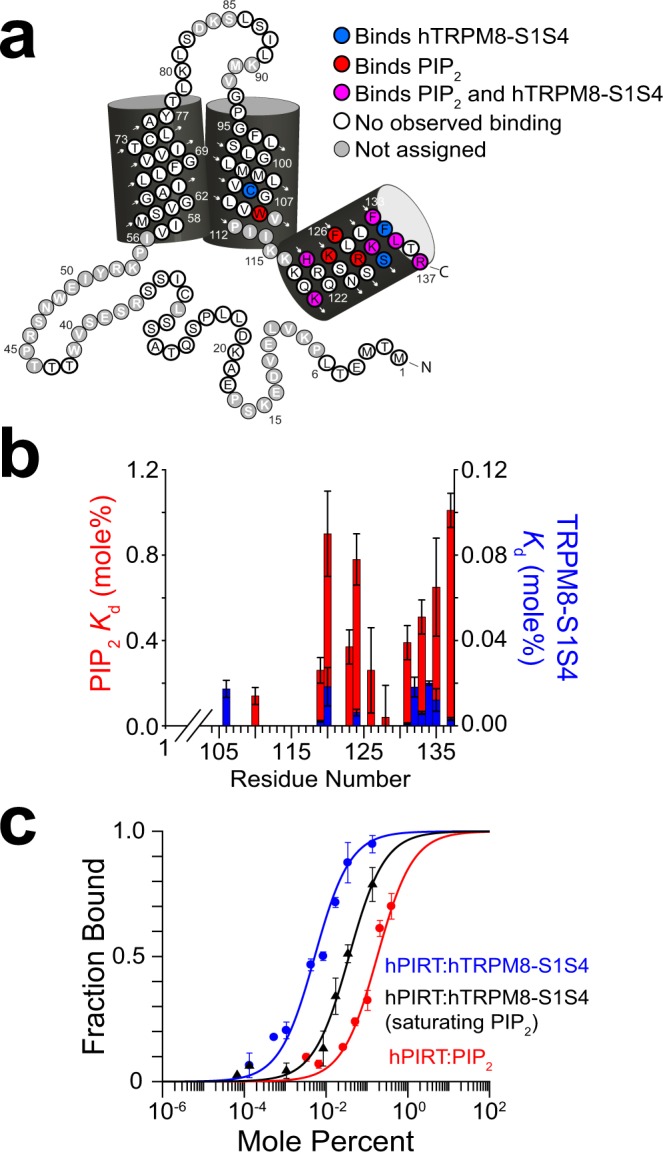

The NMR studies identify several hPIRT residues involved in binding the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain, including Lys119 and His120, that overlap with the putative PIP2 binding pocket (Figs 2c, 3c and 4a) suggesting the potential for a competitive interaction (Supplementary Table S2). We used MST to interrogate the apparent hPIRT competitive binding for PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4. In Fig. 4a, the overlapping binding residues are mapped onto the hPIRT topology, which suggests that the C-terminal helix is predominantly responsible for binding to both the hTRPM8-S1S4 and PIP2, with relative affinities suggesting hPIRT has a higher affinity for hTRPM8-S1S4 than PIP2 (Fig. 4b). MST has been used previously to measure affinities for hTRPM8-S1S4 ligand interactions37, PIP2 protein interactions40, and is highly sensitive to minor differences in binding41. Kd values obtained from MST measurements of the affinities of hPIRT for PIP2 and hTRPM8-S1S4 are 0.18 ± 0.06 mole% and 0.0053 ± 0.0004 mole%, respectively (Fig. 4c) and corroborate the NMR determined affinities (Supplementary Table S2). Competitive hPIRT binding to hTRPM8-S1S4 in the presence of a saturating PIP2 concentration shows a seven-fold decrease in affinity to 0.0365 ± 0.0005 mole% (Fig. 4c). A negative control for the MST studies shows that hPIRT does not bind to DMSO (Supplementary Fig. S4).

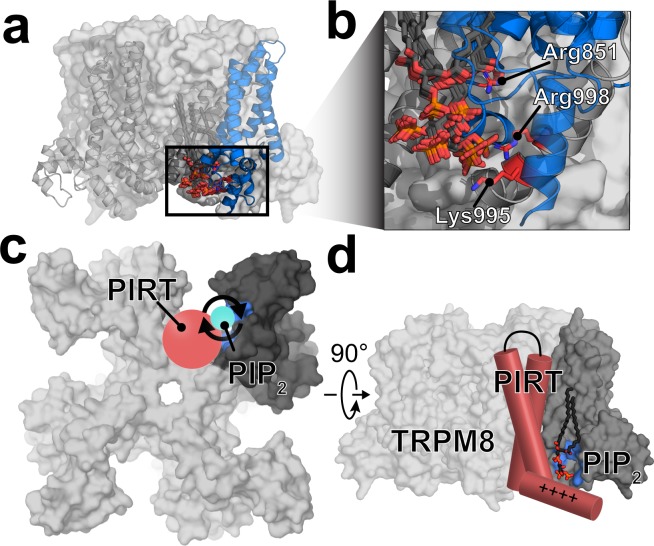

Figure 4.

Competitive PIRT binding between PIP2 and TRPM8-S1S4. (a) NMR-detected titrations show hPIRT residues that bind both to PIP2 and hTRPM8 (magenta) are generally localized to the intracellular amphipathic helix. Residues that exclusively bind PIP2 (hTRPM8-S1S4) are colored red (blue). The overlapping binding regions indicate a competitive interaction for hPIRT. (b) Comparative binding affinities between PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain to hPIRT show overlapping binding sites and a higher hPIRT affinity for hTRPM8-S1S4. (c) MST measurements highlight the apparent competitive binding relationship between hPIRT, hTRPM8-S1S4, and PIP2 suggested by the NMR data. When hPIRT is titrated with the TRPM8-S1S4 domain in the presence of saturating PIP2, the affinity curve shifts rightward, indicative of competition. MST Kd values are 5.3 ± 0.4, 36.5 ± 0.5, and 180 ± 60 millimole percent for hPIRT:hTRPM8-S1S4, hPIRT:hTRPM8-S1S4 + PIP2, and hPIRT:PIP2 respectively.

Rosetta comparative modeling of human TRPM8 transmembrane domain (TMD)

RosettaCM was used to generate a hTRPM8-TMD homology model to integrate previously published information about hTRPM8, PIP2, and hPIRT. Previous biochemistry and functional studies have identified regions of hTRPM8 that have been linked to PIP2 regulation9–11. Previous biophysical and cellular studies have suggested that hPIRT interacts with both the hTRPM8-S1S4 and pore domains12. The hTRPM8 TMD decoys were built into the electron density map from the avian Ficedula albicollis TRPM8 (FaTRPM8, 6BPQ) cryo-EM structure17 using RosettaCM electron density tools42,43, and TRPM4 as templates (Supplementary Fig. S5). Implicit membrane potentials44–46 were also used and resulted in models of human TRPM8 that include loops and side chains that are absent in the apo FaTRPM8 structure (Fig. S6a). The output shows a characteristic energy funnel of decreasing energy scores as a function of the RMSD that is typically consistent with sampling convergence (Fig. S6). Refinement of the two most populated clusters gives way to high-quality homology models as judged by analysis of the centroid model from the top ten final decoys, which has an EMRinger score of 1.6 and MolProbity clash score of 4.99 (94th percentile) after accounting for the number of residues47,48. The resulting hTRPM8 TMD homology models also fit well to the FaTRPM8 electron density (Fig. S6a). Analysis of the top ten final models also shows that there is relatively little Cα deviation especially in the transmembrane regions (Fig. S6a), which are those that have been implicated in hPIRT modulation12. The hTRPM8-TMD models contain Lys680, Arg688, Arg851, Lys995, Arg998, and Arg1008 (Fig. S9) that were previously suggested to interact with the electronegative phosphoryl groups in PIP29,17 but were unresolved in the apo FaTRPM8 structure.

Computational PIP2 docking to the hTRPM8–TMD

Rosetta-based ligand docking was used to probe the PIP2 binding site of hTRPM8. Unrestrained docking of PIP2 to the hTRPM8-TMD was used to generate 10,000 TRPM8–PIP2 decoys. These docked complexes identify a PIP2 binding pocket that is consistent with PIP2-dependent TRPM8 residues that were previously determined experimentally (Fig. S7)9–11. Generally, the unrestrained PIP2 docking appears to highlight a positively charged area near the juxtamembrane region at the nexus of the hTRPM8 pore, S1-S4, and TRP domains. To refine the docking with functional-based restraints, we selected centroids from the largest PIP2 binding clusters (Supplementary Figs S8 and S9) to seed the next rounds of docking using the Rosetta Matcher constraint protocols49. Experimentally, residues Lys995, Arg998, and Arg1008 have been implicated in PIP2 regulation of TRPM89. However, because Arg1008 is not spatially close to Lys995 nor Arg998, we performed two additional rounds of docking using constraints to guide PIP2 near Lys995/Arg998 (Fig. S7c,d) or Arg1008. With 1000 experimentally guided decoys, seeded from the 10,000 unrestrained decoys, PIP2 binding near hTRPM8 residues Lys995 and Arg998 were consistently identified in both the unrestrained (Supplementary Fig. S9) and Lys995/Arg998 restrained docking (Fig. 5). Decoys with PIP2 in the vicinity of Arg1008 were not populated in the large, unrestrained docking of 10,000 PIP2 decoys, which is in agreement with recent PIP2 bound structures50. Nonetheless, in a subsequent docking study, PIP2 was guided near Arg1008; however, the output from these 1000 decoys and an additional 3000 decoys did not show convergence (Supplementary Fig. S10). Generally, the Arg1008 guided decoys did not result in a consensus PIP2 binding site. During the manuscript review process, additional structures of FaTRPM8 were determined using cyro-EM50. Two of these structures, namely 6nr2 and 6nr3, identify the binding site of PIP2 in TRPM8. These structures are remarkably consistent with the docking outcomes as shown in Fig. 5 and validate the location of the PIP2 binding site. Comparison of the cryo-EM structures with the computational docking are shown in and compared in Fig. S11. Given that hPIRT binds PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain, and recent structural data that validate our comptuationally identified TRPM8–PIP2 binding site that is centered around the TRPM8-S1S4 domain, it follows that PIRT presumably binds TRPM8 near the TRPM8–PIP2 binding site to excert its modulatory impact.

Figure 5.

Computational docking was used to identify the PIP2 binding site of hTRPM8 and suggests the region where PIRT binds TRPM8. (a) The largest clusters of docked PIP2 are localized around the positively charged intracellular space near the TRP domain interfacing with the S1S4 domain. (b) Arg851, Lys995, and Arg998 in TRPM8 were previously identified as PIP2 sensitive in early cellular studies and are shown near the docked PIP2. The results from the hPIRT binding and lipid docking studies implicate the binding site for PIRT modulation of TRPM8. (c) A proposed mechanism of PIRT regulation emerges where PIP2 accessibility for TRPM8 activation is regulated by PIRT binding leading to channel regulation. PIRT is shown in red, PIP2 in cyan, the TRPM8-S1S4 domain in dark grey, and Arg851, Lys995, and Arg998 are highlighted in a blue surface for a monomer. (d) Cartoon of PIRT, near the PIP2 binding site of TRPM8. This interaction is consistent with PIRT binding both the TRPM8-S1S4 domain (dark grey) and PIP2 competitively and places PIRT near the pore domain which has been shown to be important in PIRT modulation of TRPM8 previously. For simplicity, the figure only depicts a single binding interaction, previous studies suggest that there are up to four PIRT binding sites in a tetrameric TRPM8 channel.

Discussion

Since its identification in 2008, PIRT has been implicated in the modulation of TRPM8, TRPV1, P2X2, and P2X3 ion channels with corresponding functional consequences that impact hot and cold temperature sensing12,14,22, neuropathic23 and uterine contraction pain sensing26, histaminergic and non-histaminergic itch25, enteric nervous system regulation27, and bladder overactivity28. Initial murine studies of PIRT modulation of TRPM8 functionally implicated the TRPM8–PIRT complex in thermosensing and showed that PIRT increases TRPM8 channel conductance13,14. Recent cellular studies identified species-dependent effects confirming that mouse PIRT enhances mouse TRPM8 currents while human PIRT attenuates hTRPM8 conductance12. As part of these cellular studies, hPIRT was shown to directly bind to the hTRPM8-S1S4, and the hTRPM8 pore domain was identified as central to the species-dependent functional effects12. To expand our understanding of hTRPM8 modulation by hPIRT at the molecular level, we experimentally determined the hPIRT membrane topology and characterized the direct binding of hPIRT to both PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain using solution NMR. These NMR-detected binding data indicate a competitive interaction between hPIRT binding PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4. MST studies of hPIRT binding further confirm a competitive interaction between PIP2 and hTRPM8-S1S4. To put our experimental results in a molecular context, we used computational techniques to construct a homology model of hTRPM8-TMD guided by the electron microscopy density map from the avian FaTRPM8 structure17 and the homologous mouse TRPM4 structure51,52. Using this homology model, we used experimentally guided computational docking of PIP2 to identify the binding site9. Given that hPIRT binds the hTRPM8-S1S4 and PIP2, and hTRPM8 binds PIP2, these computational studies allow us to predict the general region where hPIRT binds hTRPM8 (Fig. 5c,d). Our studies herein experimentally identify the hPIRT topology, help illuminate the mechanism for hPIRT modulation of hTRPM8, and provide insight into where hPIRT potentially binds hTRPM8.

MST binding studies confirm results from NMR showing hPIRT interacts with both PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain (Fig. 4) and that hPIRT affinity for the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain that is about 35-fold higher (lower Kd value) than that for the PIP2 lipid. While the MST and NMR binding data are generally in good agreement, the relatively small differences in the affinities observed here are likely explained by the fact that the NMR experiments were carried out near physiological temperature (40 °C) and the MST measurements at room temperature (25 °C). The MST competitive binding assay monitoring hTRPM8-S1S4 affinity in the presence of saturating PIP2 supports the overlapping hPIRT binding sites identified by NMR. Specifically, in the presence of saturating PIP2, the affinity between hPIRT and hTRPM8-S1S4 is decreased by ca. 7-fold as noted by increased Kd values (Fig. 4b). Taken together, the observation from NMR studies that identify overlapping hPIRT binding residues for PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain combined with the MST data showing a decrease in affinity for the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain in the presence of PIP2 is indicative of a competitive interaction. In the context of functional regulation, we suggest that the mechanism for hPIRT regulation of hTRPM8 relies at least in part on modulating channel access to PIP2, a required lipid cofactor for hTRPM8 function9.

A detailed structural understanding of the TRPM8–PIP2 complex would help explain how PIRT modulates TRPM8 function and identify potential modes of interaction between hTRPM8 and hPIRT. During the manuscript peer-review process, two FaTRPM8 cryo-EM structures were determined with PIP2 bound and resolved50. These PIP2 bound TRPM8 structures, validate the Rosetta-based PIP2 docking to hTRPM8 (Figs 5 and S11). Our docked hTRPM8–PIP2 models, together with the binding data showing that hPIRT binds to the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain and PIP2, suggest that PIRT likely binds TRPM8 near the PIP2 binding site. Collectively, the data imply that PIRT interacts with TRPM8 on the S1/S4 helix face of the S1S4 domain (Fig. 5c), which would place PIRT near the TRPM8 pore domain and the TRP helix (Fig. 5d), which are emerging as critical regions related to TRP channel function and PIRT regulation12.

PIP2 plays a multitude of roles in biology53, and many regulatory pathways control its availability. Some of these pathways include regulation of PIP2 biosynthesis, interconversion between phosphoinositide species, and degradation (e.g., phospholipase C cleavage of PIP2 to inositol 1,4,5 tris-phosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG)). Additionally, local PIP2 concentrations can be controlled by sequestration by PIP2 binding proteins54,55. For example, MARCKS (Myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate) is a PIP2 binding protein that is thought to participate in regulating the concentration of free PIP2 in the membrane55,56. The MARCKS–PIP2 interaction is reversible such that free PIP2 concentrations are dynamically regulated55. PIRT, like MARCKS and other PIP2 binding proteins, has a polybasic region that is an electrostatic complement to the PIP2 head group (Fig. 2c). By analogy, PIRT regulation of TRPM8 activity, and generally for other PIRT-sensitive ion channels, may arise from the ability of PIRT to shuttle and/or sequester PIP2 leading to activation or attenuation respectively.

Access to PIP2 has strong modulatory effects on many ion channels, including many TRP channels9,11,57–64, with recent studies suggesting channel regulation can be controlled by access to PIP29,62–64. The voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ1, which is structurally homologous to hTRPM8, also requires PIP2 to function, where PIP2 is thought to stabilize the channel in an open state by maintaining coupling between the voltage-sensing domain (helices S1-S4) and the pore domain (S5-S6)11,65. KCNQ1 functional studies indicate that positively charged residues in the post S6 helical region are essential to PIP2 regulation66 and this region is structurally homologous to the TRP domain in hTRPM8 identified by Rohacs and coworkers to be important in PIP2 regulation of hTRPM89. Interestingly, the KCNQ1–KCNE1 complex is also regulated by PIP2 where the complex function is dependent on the lipid65,66. Analogous to PIRT, the modulatory KCNE1 protein has a polybasic region near the inner membrane leaflet. In KCNE1 and other KCNE family members, these basic residues are key determinants of PIP2 sensitivity for the KCNQ1–KCNE1 complex67. This general mode of PIP2 localizing between TRPM8 and PIRT is reminiscent of KCNQ1 and KCNE1. For PIRT modulation of TRPM8, our experimental data show that hPIRT binds both PIP2 and the hTRPM8-S1S4 competitively (Fig. 4). A previous study identified that PIRT modulation of TRPM8 also depends on the pore domain12. The PIP2–hTRPM8 docking studies, and recent cryo-EM structural studies50, identify that PIP2 binds near the domains in TRPM8 implicated in PIRT binding and functional studies12. Together, these hTRPM8 regions are located in relative proximity and are consistent with a competitive model of hPIRT regulation of hTRPM8. In general, PIRT–PIP2 interactions could lead to increased or decreased local effective PIP2 concentrations, i.e., a shuttling/sequestering mechanism, that could lead to both positive and negative regulation of a given PIP2-dependent channel.

Our proposed mechanism for PIRT function integrates previous experimental observations that PIP2 depletion from TRPM8 leads to inactive TRPM8-dependent conductance9,10,68, that PIRT effectively desensitizes TRPM8 conductance in electrophysiological studies using human constructs12, that our competitive binding data shows PIRT binds TRPM8 and PIP2, and our structurally validated50 computational docking models highlight the putative PIP2 binding region. Our data suggest a mechanism for PIP2 modulation by dynamic allocation between PIRT, a PIP2 binding protein, and TRPM8, a PIP2 sensitive ion channel.

Methods

Purification and solubilization

Expression and purification of hPIRT follows the protocol outlined in Hilton, et al.12. The resulting hPIRT was greater than 95% pure as verified by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. S1). Following ion exchange chromatography, the buffer was exchanged and concentrated to NMR buffer (4% D2O (v/v), 20 mM sodium phosphate (Fisher Scientific) and 0.2 mM EDTA at pH 6.5) and a final volume of 180 μL for NMR studies. The identity of the protein was verified by LC-MS/MS (MS Bioworks) after trypsin digestion with 62% coverage of hPIRT, including regions spanning both N- and C-termini, indicating full-length protein was expressed, purified, and ultimately studied.

Expression and purification of hTRPM8-S1S4

The expression and purification of the human TRPM8 ligand sensing domain (hTRPM8-S1S4) followed what was previously reported12,37.

Far-UV circular dichroism (CD)

A Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter was used to collect a CD spectrum of hPIRT (Supplementary Fig. S1). The CD buffer conditions were identical to those used in the NMR studies with a hPIRT concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. Temperature was maintained with a Jasco Peltier device (JASCO PTC-424S) and set to 40 °C. The data was collected from signal averaging five scans from 190 nm to 250 nm in 0.5 nm steps.

Detergent screening hPIRT

To optimize the detergent conditions for solution NMR, hPIRT was reconstituted in six different membrane mimics and screened by 15N TROSY-HSQC experiments (Supplementary Fig. S2). hPIRT was expressed and purified as described above, except that Empigen was exchanged to a specific candidate detergent. The following micelle and bicelle membrane mimics were evaluated: DHPC, LMPC, DMPG:DHPC q = 0.3, LMPG, TDPC, and DPC.

Amino acid resonance assignment and secondary structure assessment

To assign the hPIRT backbone resonances, a 0.9 mM sample of 15N, 13C labeled hPIRT in a 3 mm diameter NMR tube with 4% D2O (v/v) was used to collect transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)69 versions of traditional protein backbone amide 3D experiments on a Bruker 850 MHz (1H) Avance III HD spectrometer with a 5 mm TCI Cryoprobe. The experiments collected include TROSY-based HSQC, HNCA, HNCOCA, HNCACB, HNCO, and CBCACONH; parameters for each experiment are listed in Supplementary Tabel S1 and representative assignment data shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Uniformly sampled NMR experiments were processed in nmrPipe70 and analyzed in CcpNMR71. Non-uniformly sampled experiments were reconstructed using qMDD72, processed in NMRPipe, and analyzed in CcpNMR. The resonance assignments were deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB ref 27438). Human PIRT secondary structure prediction was generated from the backbone resonance assignments with the TALOS-N software30,31.

Non-covalent solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) studies

Resonance intensities were monitored on a 0.3 mM hPIRT sample by collecting 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra at 850 MHz 1H with 0 mM, 2 mM, 6 mM, 10 mM, and 20 mM Gd(III)-DTPA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) from a stock solution of 150 mM Gd(III)-DTPA in 25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5 and 250 mM EDTA (Sigma Aldrich). EDTA is present to chelate any free Gd(III). The intensities of individual amino acids resonances were then plotted as a function of the concentration of added Gd(III)-DTPA and fit according to a mono-exponential decay ; where ε is the solvent paramagnetic relaxation enhancement, x is the concentration of Gd(III)-DTPA added. The magnitude of ε was then plotted as a function of the corresponding residue number (Fig. 1d).

15N hPIRT-detected NMR titrations with hTRPM8-S1S4 and PIP2

15N-hPIRT was titrated with 14N-hTRPM8-S1S4 or a short chain PIP2 lipid, (1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-myo-inositol-4′,5′-bisphosphate).The titration with hTRPM8-S1S4:hPIRT follows what was done for Hilton, et al.12 with the exception that the mole ratios are converted to mole percentage of titrated hTRPM8-S1S4 and are 3.7 × 10−3, 7.5 × 10−3, 14.9 × 10−3, 29.9 × 10−3, 37.3 × 10−3, 59.8 × 10−3, 74.7 × 10−3, 112.0 × 10−3, 149.0 × 10−3, where mole percent is defined as:

The hPIRT titration with PIP2 was done in a similar fashion as the hTRPM8-S1S4 domain, except that the amount of PIP2 used corresponds to the following mole percentages: 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.40, 0.80, and 1.5.

Changes in chemical shift were analyzed according to previously established protocols12,38,73. Errors in Kd were calculated using the standard deviations of the fit, by using Matlab R2017a to fit the adsorption binding model and then taking the square root along the diagonal of the covariance matrix of the fit.

Microscale thermophoresis

Microscale thermophoresis was measured on a Nanotemper Monolith NT.115 nano Blue/Green (MO-G008) instrument. Human PIRT was labeled with the Nanotemper green maleimide reactive fluorophore. Before labeling, hPIRT was purified and solubilized in 0.1% DPC in 50 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.5 as described above, which was then buffer exchanged to remove imidazole using a 10 kDa cutoff Amicon Ultra 5 centrifugal filter unit. After which, 100 μL of 20 μM hPIRT was reacted in the dark with 2 mM DTT for 3 h at room temperature. The fluorophore was added to a final volume of 200 μL and a concentration of 2:1 dye:protein (mol:mol). The maleimide reaction was carried out in the dark at room temperature overnight and then purified using a gravity flow desalting column. One column volume eluted the labeled protein at 6 μM concentration and a volume of 300 μL.

For the hTRPM8-S1S4 sample, 40 μL of 400 nM hPIRT was used per titration point in mole percentages of 0.1368, 0.0342, 0.0171, 0.0086, 0.0043, 0.0011, 0.0005, and 0.0001 of hTRPM8-S1S4. For the PIP2 sample, 40 μL of 400 nM of hPIRT was prepared with an initial 0.1 mg/mL of PIP2 with mole percentages of 0.421, 0.220, 0.110, 0.055, 0.028, 0.007, and 0.004. For competitive studies with saturating PIP2, the hTRPM8-S1S4 was prepared as above but included 4.05 mole% PIP2 in each tube. All the samples were run in triplicate with 95% LED power and 40% infrared laser power. As a control, hPIRT was titrated in the same buffer conditions and protein concentration as above with DMSO concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 100 mM with no ligand-dependent thermophoresis observed (Supplementary Fig. S4). Error bars in MST measurements were calculated as fraction bound standard errors of the mean from three separate measurements.

Rosetta comparative modeling of the human TRPM8 transmembrane domain (residues 672–1012)

A Rosetta protocol capture and PDB formatted lowest energy hTRPM8-TMD comparative model are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Briefly, RosettaCM42 was used to model the hTRPM8-TMD (amino acids 672–1012). Using Rosetta protocols with implicit membrane scoring functions44–46, 11,300 decoys were generated using FaTRPM8 (6BPQ)17 and mTRPM4 (6BQV, 6BCL, 6BCJ, 5WP6, 6BCO)51,52 cryo-EM structures as templates, and the FaTRPM8 EM electron density map as a restraint (EMDB: 7127). To use these structural templates, a sequence alignment was created using CLUSTAL-Ω74 between the hTRPM8, flycatcher TRPM8, and the mouse TRPM4 (Supplementary Fig. S6), which was manually refined to enforce a known functional disulfide bond75. The alignment file was then used to thread the hTRPM8 sequence onto each template. The 9mer and 3mer fragments were generated using the ROBETTA server76 for positions 672–1012 of the hTRPM8 amino acid sequence. The flycatcher TRPM8 cryo-EM structure has no density for the following transmembrane regions: 716–721, 820–822, 889–894, 912–945, and 978–990 and were rebuilt de novo in the human comparative model. All-atom refinement was carried out on the two biggest clusters identified with Calibur software77 comprising 379 and 241 decoys and expanded to 5600 decoys per cluster. All decoys were rescored with mpframework_fa_2007.wts45,46 to the respective lowest energy conformer and clustered with Calibur where the lowest energy decoy from the largest cluster was used as the representative model.

Rosetta ligand docking of PIP2 to hTRPM8 transmembrane domain (residues 672–1012)

A Rosetta protocol capture for docking is provided in the Supplementary Materials. Rosetta has been used in the past to dock ligands to membrane proteins78, and we used a RosettaScripts79 protocol to computationally dock PIP2 (CHARMM small molecule library, CSML: SAPI24)80 to our hTRPM8-TMD comparative model. The initial PIP2 starting point was manually placed out of contact between hTRPM8-S1S4 domains with PIP2 in the pseudo-bilayer plane and the head group in an intracellular facing orientation (Supplementary Fig. S5). To efficiently sample PIP2 conformational space, 1000 PIP2 conformers were generated using Frog281 with the AMMOS energy minimization82. Docking PIP2 to hTRPM8 followed previously optimized Rosetta protocols to generate a total of 10,000 docked hTRPM8–PIP2 complex decoys79. The Rosetta score versus the ligand PIP2 RMSD to the lowest energy decoy was analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S6) to assign cluster centroids and then finally each assigned centroid was individually analyzed in PyMol (Supplementary Fig. S7). The ligand RMSD corresponds to the internal symmetries and equivalent atoms within the ligand79. The cluster centroids were used to seed an additional 1000 Rosetta-generated decoys guided by experimental pseudo-constraints49 to encourage either Lys995 or Arg998 to non-covalently interact with the head group of PIP2. To limit computational bias, the constraint file did not direct which phosphate should interact with Lys995 or Arg998, nor did it specify whether Lys995 or Arg998 would be favored for the interaction. Separately, docking with PIP2 constraints guided to Arg1008 was calculated with 4000 decoys and analyzed with poor results and modes that predominantly force PIP2 into unlikely binding modes. It is worth noting that Arg1008 is not near enough to the positively charged pocket where Lys995 and Arg998 to satisfy one PIP2 molecule per monomer. Additionally, the PIP2 tails were loosely constrained (see PIP2 constraint file in Supplementary Material) by loosely enforcing the distal regions of the acyl chains to the hydrophobic core of the implicit membrane bilayer in order encourage a physiologically appropriate PIP2 membrane depth. After the constraint guided refinement, a small perturbation using the Transform mover was applied to increase sampling near the consensus docking site. A plot of the refined decoys score versus RMSD was analyzed with the 20 lowest energy decoys from each of three clusters were used in the analysis of hTRPM8–PIP2 complex and the implications for hPIRT modulation (Figs S7–S9).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the computational and NMR resources and support available through Arizona State University. We acknowledge Dorothy Machorro who helped identify conditions suitable for hPIRT expression and Dr. Jacob Hilton for suggestions and editing of the manuscript. This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health grant R01GM112077 to W.D.V.H.

Author Contributions

N.J.S. expressed and purified proteins used in these studies. N.J.S. and W.D.V.H. collected NMR data. N.J.S collected MST data. N.J.S. and C.V.M.H. performed Rosetta calculations. N.J.S. and W.D.V.H. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. W.D.V.H. conceived and designed the study.

Data Availability

The data generated from the current study are available from W.D.V.H. on reasonable request. hPIRT NMR assignment data have been deposited in the BMRB 27438. The lowest scoring hTRPM8-TMD decoy is included in the Supplementary Materials.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49912-5.

References

- 1.Proudfoot CJ, et al. Analgesia mediated by the TRPM8 cold receptor in chronic neuropathic pain. Current Biology. 2006;16:1591–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsavaler L, Shapero MH, Morkowski S, Laus R. Trp-p8, a novel prostate-specific gene, is up-regulated in prostate cancer and other malignancies and shares high homology with transient receptor potential calcium channel proteins. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3760–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Barritt GJ. Evidence that TRPM8 is an androgen-dependent Ca2+ channel required for the survival of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8365–8373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma S, et al. Activation of the cold-sensing TRPM8 channel triggers UCP1-dependent thermogenesis and prevents obesity. Journal of molecular cell biology. 2012;4:88–96. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi HL, et al. Characterization of bilateral trigeminal constriction injury using an operant facial pain assay. Neuroscience. 2012;224:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 2002;416:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid G, Flonta ML. Ion channels activated by cold and menthol in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Neurosci Lett. 2002;324:164–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilton JK, Rath P, Helsell CV, Beckstein O, Van Horn WD. Understanding thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels as versatile polymodal cellular sensors. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2401–2413. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Michailidis I, Logothetis DE. PI(4,5)P2 regulates the activation and desensitization of TRPM8 channels through the TRP domain. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:626–634. doi: 10.1038/nn1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yudin Y, Lukacs V, Cao C, Rohacs T. Decrease in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels mediates desensitization of the cold sensor TRPM8 channels. J Physiol. 2011;589:6007–6027. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.220228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Qin F. Functional control of cold- and menthol-sensitive TRPM8 ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1674–1681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilton JK, Salehpour T, Sisco NJ, Rath P, Van Horn WD. Phosphoinositide-interacting regulator of TRP (PIRT) has opposing effects on human and mouse TRPM8 ion channels. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:9423–9434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang M, Wu GY, Dong XZ, Tang ZX. Phosphoinositide interacting regulator of TRP (Pirt) enhances TRPM8 channel activity in vitro via increasing channel conductance. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:98–104. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Z, et al. Pirt functions as an endogenous regulator of TRPM8. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2179. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarria I, Ling J, Zhu MX, Gu JG. TRPM8 acute desensitization is mediated by calmodulin and requires PIP(2): distinction from tachyphylaxis. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:3056–3066. doi: 10.1152/jn.00544.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gkika D, et al. TRP channel-associated factors are a novel protein family that regulates TRPM8 trafficking and activity. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:89–107. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin Y, et al. Structure of the cold- and menthol-sensing ion channel TRPM8. Science. 2018;359:237–241. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson DA, Chase HW, Bevan S. TRPM8 activation by menthol, icilin, and cold is differentially modulated by intracellular pH. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5364–5369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0890-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersson DA, Nash M, Bevan S. Modulation of the cold-activated channel TRPM8 by lysophospholipids and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3347–3355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4846-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanden Abeele F, et al. Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2-dependent gating of TRPM8 by lysophospholipids. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40174–40182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morenilla-Palao C, Pertusa M, Meseguer V, Cabedo H, Viana F. Lipid raft segregation modulates TRPM8 channel activity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9215–9224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807228200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim AY, et al. Pirt, a phosphoinositide-binding protein, functions as a regulatory subunit of TRPV1. Cell. 2008;133:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, et al. Pirt Together with TRPV1 Is Involved in the Regulation of Neuropathic Pain. Neural Plast. 2018;2018:4861491. doi: 10.1155/2018/4861491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UniProt C. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D204–212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel KN, Liu Q, Meeker S, Undem BJ, Dong X. Pirt, a TRPV1 modulator, is required for histamine-dependent and -independent itch. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C, et al. Pirt contributes to uterine contraction-induced pain in mice. Mol Pain. 2015;11:57. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0054-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo W, et al. Co-localization of Pirt protein and P2X2 receptors in the mouse enteric nervous system. Purinergic Signal. 2016;12:489–496. doi: 10.1007/s11302-016-9515-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao XF, et al. Pirt reduces bladder overactivity by inhibiting purinergic receptor P2X3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7650. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jall Sigrid, Finan Brian, Collden Gustav, Fischer Katrin, Dong Xinzhong, Tschöp Matthias H., Müller Timo D., Clemmensen Christoffer. Pirt deficiency has subtle female-specific effects on energy and glucose metabolism in mice. Molecular Metabolism. 2019;23:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Y, Bax A. Protein structural information derived from NMR chemical shift with the neural network program TALOS-N. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1260:17–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2239-0_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen Y, Bax A. Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J Biomol NMR. 2013;56:227–241. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beel AJ, et al. Structural studies of the transmembrane C-terminal domain of the amyloid precursor protein (APP): does APP function as a cholesterol sensor? Biochemistry. 2008;47:9428–9446. doi: 10.1021/bi800993c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butterwick JA, MacKinnon R. Solution structure and phospholipid interactions of the isolated voltage-sensor domain from KvAP. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DT. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W349–357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson MP. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Progress in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. 2013;73:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rath P, Hilton JK, Sisco NJ, Van Horn WD. Implications of Human Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 8 (TRPM8) Channel Gating from Menthol Binding Studies of the Sensing Domain. Biochemistry. 2016;55:114–124. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett PJ, et al. The amyloid precursor protein has a flexible transmembrane domain and binds cholesterol. Science. 2012;336:1168–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.1219988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng H, Jiang X, Han X. Alterations in lipid homeostasis of mouse dorsal root ganglia induced by apolipoprotein E deficiency: a shotgun lipidomics study. J Neurochem. 2007;101:57–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van den Bogaart G, Meyenberg K, Diederichsen U, Jahn R. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate increases Ca2+ affinity of synaptotagmin-1 by 40-fold. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:16447–16453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.343418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jerabek-Willemsen M, Wienken CJ, Braun D, Baaske P, Duhr S. Molecular interaction studies using microscale thermophoresis. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2011;9:342–353. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song Y, et al. High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure. 2013;21:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DiMaio F, Tyka MD, Baker ML, Chiu W, Baker D. Refinement of protein structures into low-resolution density maps using rosetta. J Mol Biol. 2009;392:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yarov-Yarovoy V, Schonbrun J, Baker D. Multipass membrane protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Proteins. 2006;62:1010–1025. doi: 10.1002/prot.20817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alford RF, et al. An Integrated Framework Advancing Membrane Protein Modeling and Design. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barth P, Schonbrun J, Baker D. Toward high-resolution prediction and design of transmembrane helical protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15682–15687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702515104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barad BA, et al. EMRinger: side chain-directed model and map validation for 3D cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2015;12:943–946. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter F, Leaver-Fay A, Khare SD, Bjelic S, Baker D. De novo enzyme design using Rosetta3. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin Ying, Le Son C., Hsu Allen L., Borgnia Mario J., Yang Huanghe, Lee Seok-Yong. Structural basis of cooling agent and lipid sensing by the cold-activated TRPM8 channel. Science. 2019;363(6430):eaav9334. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Autzen HE, et al. Structure of the human TRPM4 ion channel in a lipid nanodisc. Science. 2018;359:228–232. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo J, et al. Structures of the calcium-activated, non-selective cation channel TRPM4. Nature. 2017;552:205–209. doi: 10.1038/nature24997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gambhir A, et al. Electrostatic sequestration of PIP2 on phospholipid membranes by basic/aromatic regions of proteins. Biophys J. 2004;86:2188–2207. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McLaughlin S, Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laux T, et al. Gap43, Marcks, and Cap23 Modulate Pi(4,5p)2 at Plasmalemmal Rafts, and Regulate Cell Cortex Actin Dynamics through a Common Mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:1455–1472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bandell M, et al. High-throughput random mutagenesis screen reveals TRPM8 residues specifically required for activation by menthol. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:493–500. doi: 10.1038/nn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brauchi S, et al. Dissection of the components for PIP2 activation and thermosensation in TRP channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10246–10251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703420104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen L, et al. Migration of PIP2 lipids on voltage-gated potassium channel surface influences channel deactivation. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15079. doi: 10.1038/srep15079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han B, et al. Human EAG channels are directly modulated by PIP2 as revealed by electrophysiological and optical interference investigations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23417. doi: 10.1038/srep23417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun J, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM Structure of a KCNQ1/CaM Complex Reveals Insights into Congenital Long QT Syndrome. Cell. 2017;169:1042–1050 e1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.She J, et al. Structural insights into the voltage and phospholipid activation of the mammalian TPC1 channel. Nature. 2018;556:130–134. doi: 10.1038/nature26139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rohacs T. Phosphoinositide regulation of TRP channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;223:1143–1176. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05161-1_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H, et al. PIP2 Activates KCNQ Channels, and Its Hydrolysis Underlies Receptor-Mediated Inhibition of M Currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loussouarn G, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2, controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K+ channels. EMBO J. 2003;22:5412–5421. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, et al. KCNE1 enhances phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) sensitivity of IKs to modulate channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9095–9100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100872108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daniels RL, Takashima Y, McKemy DD. Activity of the neuronal cold sensor TRPM8 is regulated by phospholipase C via the phospholipid phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1570–1582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Czisch M, Boelens R. Sensitivity enhancement in the TROSY experiment. J Magn Reson. 1998;134:158–160. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delaglio F, et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vranken WF, et al. The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kazimierczuk K, Orekhov VY. Accelerated NMR spectroscopy by using compressed sensing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:5556–5559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kroncke BM, et al. Structural basis for KCNE3 modulation of potassium recycling in epithelia. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1501228. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dragoni I, Guida E, McIntyre P. The cold and menthol receptor TRPM8 contains a functionally important double cysteine motif. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37353–37360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim DE, Chivian D, Baker D. Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W526–531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li SC, Ng YK. Calibur: a tool for clustering large numbers of protein decoys. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nguyen ED, Norn C, Frimurer TM, Meiler J. Assessment and challenges of ligand docking into comparative models of G-protein coupled receptors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lemmon G, Meiler J. Rosetta Ligand docking with flexible XML protocols. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;819:143–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-465-0_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jo S, Kim T, Iyer VG, Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J Comput Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Miteva MA, Guyon F, Tuffery P. Frog2: Efficient 3D conformation ensemble generator for small compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W622–627. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pencheva T, Lagorce D, Pajeva I, Villoutreix BO, Miteva MA. AMMOS: Automated Molecular Mechanics Optimization tool for in silico Screening. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:438. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated from the current study are available from W.D.V.H. on reasonable request. hPIRT NMR assignment data have been deposited in the BMRB 27438. The lowest scoring hTRPM8-TMD decoy is included in the Supplementary Materials.