Abstract

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a major side effect of cancer therapy that frequently requires a reduction or cessation of treatments and negatively impacts the patient’s quality of life. There is currently no effective means to prevent or treat CIPN. In this study, we developed and applied CIPN in an immunocompetent, syngeneic murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLCab) model that enabled the elucidation of both tumor and host responses to cisplatin and treatments of Y-27632, a selective inhibitor of Rho kinase/p160ROCK. Y-27632 not only preserved cisplatin’s efficacy towards tumor suppression but also the combination treatment inhibited tumor cell proliferation and increased cellular apoptosis. By alleviating the cisplatin induced-loss of epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs), Y-27632 protected tumor-bearing mice from cisplatin-induced reduction of touch sensation. Furthermore, quantitative proteomic analysis revealed the striking cisplatin-induced dysregulation in cellular stress (inflammation, mitochondrial deficiency, DNA repair,etc) associated proteins. Y-27632 was able to reverse the changes of these proteins that are associated with Rho GTPase and NF-κB signaling network, and also decreased cisplatin-induced NF-κB hyperactivation in both foot pad tissues and tumor. Therefore, Y-27632 is an effective adjuvant in tumor suppression and peripheral neuroprotection. These studies highlight the potential of targeting the RhoA-NF-κB axis as a combination therapy to treat CIPN.

Keywords: Cisplatin, Peripheral neuropathy, Y-27632, NF-κB, Touch sensation, Tumor-bearing mice

Introduction

Despite its longstanding clinical application as a first-line chemotherapy drug, cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum) is also known for its high level of toxicity to the peripheral nervous system, which is clinically characterized as numbness, tingling or burning sensation in the body extremities (1). Suspension or reduction of chemotherapy is often the only option for patients who have developed severe CIPN, which can eventually compromise the outcome of treatment (2). CIPN can also lead to long term morbidity, and the CIPN-associated symptoms may continue even after chemotherapy is ended.

The chemotherapeutic effect of cisplatin is to induce apoptosis in the highly proliferative cancer cells by forming covalent bonds with DNA strands (3) in the nucleus. However, cisplatin binding-DNA also accumulates in the neurons of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) (4). Since neurons are not proliferative cells, the nuclear DNA targeting mechanism of cisplatin cannot fully explain its neurotoxicity. On the other hand, increased activity of RhoA, a member of Rho family small GTPases, has been observed in a variety of neuronal injuries (5). LM11A-31, a ligand mimetic of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) that is upstream of the RhoA signaling pathway (6) (7), could partially protect peripheral nerves from being damaged by cisplatin (8). The notion of RhoA involvement in CIPN was further supported since Y-27632, a selective inhibitor of Rho kinase/p160ROCK directly downstream of RhoA (9), reversed the neurodegeneration caused by cisplatin (9).

Rho kinase/p160ROCK also plays a critical role in regulating cancer cell motility and invasion (10). Therefore, to validate the role of RhoA signaling pathway in both tumor development and CIPN, we created an immunocompetent tumor-bearing CIPN mouse model by introducing syngeneic murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLCab) cells to CIPN mouse model. The inhibition of RhoA signaling pathway was achieved by Y-27632 treatment.

In this report, we found that Y-27632 suppressed tumor cell growth by promoting apoptosis and, thus, enhanced the therapeutic effect of cisplatin in the combinatory treatment. Furthermore, in this tumor-bearing CIPN mouse model, cisplatin-induced loss of touch sensation in the mouse hind paw was ameliorated by Y-27632 treatment as it prevented the reduction of epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs). The activation of inflammatory pathway proteins such as NF-κB is associated with tumorigenesis (11,12). The progression of CIPN increases the releases of cytokines, such as TNF and IL-6, that activate NF-κB (13), and the activation of NF-κB also closely interacts with RhoA signaling pathway (14). Significantly, the present study identified that Y-27632 not only alleviated the cisplatin-induced cellular stress proteomic profiles but also suppressed cisplatin-induced NF-κB activation in the mouse footpad, providing a mechanism of dual effectiveness of Y-27632 in both tumor suppression and CIPN prevention in an immunocompetent tumor-bearing mouse model. Our study thus highlights RhoA-NF-κB signaling axis inhibition as a promising option of therapeutic intervention for CIPN and cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Cell line and culture condition

The LLCab subclone was derived from a LLC1 (CRL-1642, ATCC) metastatic tumor (15). The LLCab cells were cultured in DMEM (high glucose, high sodium bicarbonate) with 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified (37°C, 5% CO2) incubator three weeks before injection.

MTT Assay

The MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was conducted as previously described (16). Briefly, selected group of LLCab cells were treated with control (DMSO), cisplatin (8μg/ml), Y-27632 (1μM), cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (1μM), cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (10μM) or cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (100μM) for 24 h followed by incubation with MTT. The absorbance was measured at 562 nm. Data are representative of mean ± SEM from triplicates conducted at least twice.

In vivo allograft experiment and pharmacological treatment

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at East Carolina University. C57/BL6 (8~12 weeks old) female mice (Charles River, Wilmington MA) with an average weight of 20g were used. The general experimental schedule is summarized in SI Table I. In addition to the two weeks of habituation including frequent handling, mice were also subjected to another two weeks of training for familiarizing behavioral test procedures. Subsequently, mice were assayed to establish a baseline of behavior tests before the drug treatment. Then, a total of 5x105 LLCab cells (0.1ml cell media) were subcutaneously injected in the right flank of mice. Mice were randomly separated into four treatment groups five days after LLCab cells injection (week 1). Both cisplatin (Sigma Co, St. Louis MO) and Y-27632 (Millipore, MA) were dissolved in 0.9% saline (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL), and each drug treatment was administrated via an intraperitoneal injection. As illustrated in SI Table II, Saline group was treated with 200 μl 0.9% saline twice a week. Cisplatin and Y-27632 groups were received 6μg/g body weight cisplatin or 30 μg/g body weight Y-27632 (equivalent of 95 μM) accordingly once a week. To prevent cisplatin induced-renal damage, an additional 2ml 0.9% saline was injected in mice receiving cisplatin (17). The Cis+Y-27632 group received both 6μg/g body weight cisplatin and 30 μg/g body weight Y-27632 treatments weekly. Injections of cisplatin and Y-27632 were staggered (separated by 3-4 days) to minimize drug toxicity and drug interactions. On the following day of drug treatment, all mice were subjected to a Von Frey monofilament test. Body weight and tumor size were recorded daily, and the tumor volume was calculated by using the following formula: (longest tumor diameter x shortest tumor diameter x shortest tumor diameter)/2 (18–21).

Von Frey monofilament assay

The Von Frey monofilament assay for testing hind paw touch sensitivity was conducted as previously described with minor changes (22,23). Mice were placed under glass chambers above an elevated mesh floor that allowed full access to the hind paw and allowed to acclimate for 15 minutes. The test started with the smallest diameter of Von Frey monofilament (Stoeling Co., Wood Dale, IL) and diameter of monofilament was increased until applied monofilament elicited a response. The touch response of hind paw was recorded as positive when the mouse responded a minimum 3 out of 5 applications.

Tissue preparation

After euthanasia, footpad tissues were quickly removed from hind paws and either snap frozen for Western Blot analysis or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Fixed footpad tissues were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and moved to cryoprotectant (30% sucrose in PBS) at 4°C. Footpad tissues were subsequently embedded in the optimal cutting temperature compound (O.C.T) and rapidly frozen with chilled isopentane. Tissue was sectioned (10μm) using a Cryostat and slides were stored at −80°C. Tumor tissues were bisected and half of tissues went through the same tissue preparation procedure as footpad tissue, and the other half of tissues was wrapped in aluminum foil, snap frozen, and stored for Western Blot analysis.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Foot pad tissues were first incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes and then were blocked with 10% BSA in PBS at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Foot pad tissues were incubated with antibodies that listed in SI Table III overnight. Then, tissues were incubated with Cy3 rabbit antibody (1:300, 1% BSA in PBS, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or FITC-phalloidin (1:300, 1% BSA in PBS, Molecular Probes) for 1hour at room temperature. Eventually, Hoechst (1:2500, PBS, Sigma) were applied to the tissues and slides were sealed with prolong diamond anti-fade media (Invitrogen). In some cases, biotinylated secondary antibodies were also applied to the foot pad tissues, DAB staining (Vector Labs, Southfield, MI) then proceeded according to the manufacturer’s suggestions. After counterstaining with hematoxylin, sections were eventually dehydrated in 95% ethanol and mounted on coverslips. Same DAB staining procedure were applied to tumor tissues that blocked with Ki67 rabbit antibody (SI Table III) overnight. The TUNEL analysis for evaluating apoptosis in the tumor tissues was conducted as manufacturer’s suggestion (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR red, Roche), tissues were counterstained with Hoechst (1:2500, PBS, Sigma) and sections were sealed with prolong diamond anti-fade media. DAB staining images were acquired from Zeiss Axio microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) or Aperio ScanScope (Leica Biosystems, Denver). Immunofluorescent images were acquired from Olympus FV3000 confocal microscopy (Tokyo, Japan) or Zeiss Axio microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

ENFs density and MCs percentage Analysis

Forty footpad tissue sections were randomly selected from five mice of each treatment group and scanned by Aperio ScanScope (Leica Biosystems, Denver) at 40x objective. The panoramic image of each tissue section was acquired and analyzed by using ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, Denver). Epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs), which were located between dermis and epidermis of footpad tissues, were observed and counted. Moreover, the length of ENFs’ adjacent epidermis was also measured to obtain the density of ENFs (ENFs/mm) in each treatment group (24–26). The typical Meissner corpuscles (MCs) were identified between dermal papillae in each group. The density of MCs (MCs/mm) from each treatment group was acquired by the same method as the density of ENFs.

The proliferative and apoptotic ratio analyses of tumor tissue

The status of proliferation or apoptosis of tumor cells was analyzed according to the previous methods with minor modifications (27,28). Thirty-six randomly selected fields (mm2) were marked on twelve tumor tissue sections from four mice of each treatment group, the number of Ki67 or TUNEL positive cells in each area were counted. The ratio of proliferation or apoptosis of tumor cells on each tissue section was calculated as the total number of positively stained cells/area (mm2).

Western blot analysis

Selected tumor and foot pad tissues from each treatment group were pulverized in a mortar with liquid nitrogen at the end of the experiment. The tissues were sonicated in RIPA lysis buffer on ice and protein concentration was determined. Then, the protein lysates from each treatment group were equally loaded onto an 8-16% Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica MA), and subjected to Western blot analysis. Subsequently, membranes were blocked and probed with the following antibodies: rabbit Stat3 and rabbit pStat3; rabbit NF-κB and pNF-κB (SI Table III); rabbit cleaved PARP and PARP antibodies (SI Table III). Anti-GAPDH Western blot (mouse antibody, 1:2000, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was used as a loading control. The LLCab cell lysates from different in vitro treatment groups {control (DMSO), cisplatin (8μg/ml), Y-27632 (1μM), cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (1μM), cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (10μM) or cisplatin (8μg/ml) +Y-27632 (100μM)} were prepared in RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (1mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 10mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20mM sodium fluoride, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN)), and subjected to Western blot analysis described above.

Proteomic analysis

Mouse foot pads were micro-dissected and the tissue lysates were prepared as described in the Western bolt analysis. Four biological replicates of tissue samples were submitted to UNC proteomic core for proteomic analysis.

Sample Preparation: Samples were precipitated overnight with 4x volume of cold acetone. The protein pellets were washed twice with cold acetone then resolubilized in 7M urea. Each sample was reduced with 5 mM DTT, alkylated with 15 mM iodoacetamide, and digested with trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37°C. The peptide samples were acidified to 0.1% TFA, desalted using 100 mg sorbent Strata-X cartridges (Phenomenex) and dried via vacuum centrifugation. Peptide samples were reconstituted in 5% ACN, 0.1% formic acid and a peptide quantitation was performed using the Pierce Quantitative Colorimetric Peptide Assay (Thermo).

LC-MS/MS analysis: The peptide samples were analyzed by LC/MS/MS using an Easy nLC 1200 coupled to a QExactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Samples were injected onto an Easy Spray PepMap C18 column (75 μm id × 25 cm, 2 μm particle size) (Thermo Scientific) and separated over a 2 hr method. The gradient for separation consisted of 5–35% mobile phase B at a 250 nl/min flow rate over 95 minutes and then 35-45% mobile phase B at a 250 nl/min flow rate for 12 more minutes. Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in water and mobile phase B consisted of 0.1% formic acid in 80% ACN. The QExactive HF was operated in data-dependent mode where the 15 most intense precursors were selected for subsequent fragmentation. Resolution for the precursor scan (m/z 350–1600) was set to 120,000, while MS/MS scans resolution was set to 15,000. The normalized collision energy was set to 27% for HCD. Peptide match was set to preferred, and precursors with unknown charge or a charge state of 1 and ≥ 8 were excluded.

Bioinformatic analysis

The heatmap was generated using Complex Heatmap package in R. Hierarchical clustering of the z-score normalized log2 label-free quantification (LFQ) values averaged across four biological replicates for ANOVA significant proteins (p-value <0.05). The protein-protein interactions of differential expressed proteins was analyzed by STRING (Version 10.5; http://string.embl.de) with following analysis parameters: Species-Mus musculus, meaning of network edges-evidence, active interaction sources-all, interaction score-0.150.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by using Microsoft Excel and Prism 6 (GraphPad Software. Inc, California), and the results were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance of differences between treatment groups was determined either with one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following Tukey post hoc t-test. p<0.05 was applied as the threshold of significance.

Results

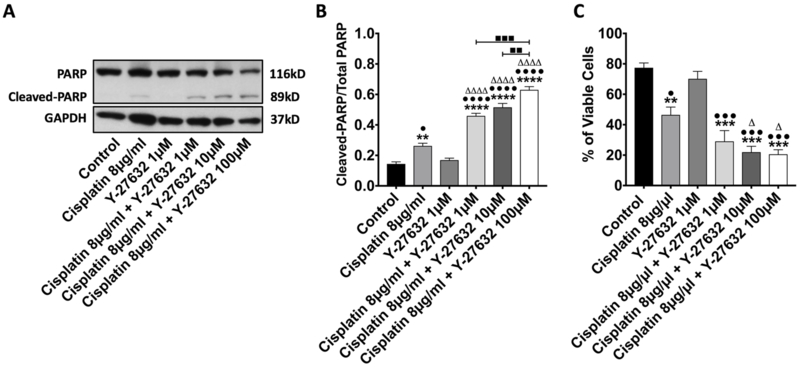

Y-27632 enhanced the antineoplastic effect of cisplatin in vitro

To investigate the potential cooperation of RhoA signaling pathway inhibition in cisplatin induced tumor remission, we first tested the effect of Y-27632 on LLCab cells in vitro. LLCab cells can spontaneously grow to an epidermoid carcinoma in the lung of an immunocopetent syngeneic C57/BL6 mouse. Cultured LLCab cells were treated either with Y-27632 alone or with concurrent treatment of cisplatin. Western Blot analysis showed that cleaved PARP was increased in cisplatin treated LLCab cells (Figure. 1A). Although, single Y-27632 treatment did not significantly elevate the expression of cleaved PARP, Y-27632 enhanced the effect of cisplatin to drastically increase the expression of cleaved PARP in combinational treatments. Quantification of the Cleaved PARP/Total PARP ratio (Figure. 1B) further demonstrated that Y-27632 reinforced cisplatin’s antineoplastic and pro-apoptotic effects when compared to cisplatin treatment alone. MTT analysis (Figure. 1C) showed similar results that Y-27632 (1μM) treatment alone did not significantly affect cancer cell’s viability, whereas Y-27632 further inhibited tumor cell growth when combined with cisplatin. In addition, the cellular activity of NF-κB was significantly increased by a 24-hour treatment of cisplatin. With the increase dose of Y-27632 in combinational treament groups, cisplatin-induced N-B’s activation was reduced (SI Figure. 1A). These in vitro results were consistent with literatures (29,30) and also provided experimental foundations for the following in vivo studies.

Figure 1. Y-27632 enhanced the antineoplastic effect of cisplatin in lung cancer cells in culture.

(A). LLCab Cells were treated with DMSO (Control), cisplatin 8μg/ml, Y-27632 1μM, cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 1μM, cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 10 μM, or cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 100 μM for 24 hours, and the cell lysates collected from each treatment group were subjected to Western blot analysis of Cleaved-PARP and Total PARP. (B). Analysis of the ratio of Cleaved-PARP/Total PARP. Values represent mean±SEM. **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, relative to Control; ΔΔΔΔp<0.0001, relative to Cisplatin 8μg/ml; •p<0.05, ••••p<0.0001, relative to Y-27632 1μM. ■■p<0.01, ■■■p<0.0005. (C). LLCab cells were treated with DMSO (Control), cisplatin 8μg/ml, Y-27632 1μM, cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 1μM, cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 10 μM, or cisplatin 8μg/ml + Y-27632 100 μM for 24 hours. Then, MTT assay analysis was applied to evaluate percentage of viable cells. Values represent mean±SEM. **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, relative to Control; •p<0.05, •••p<0.0001, relative to Y-27632 1μM; Δp<0.05, relative to Cisplatin 8μg/ml.

Y-27632 suppressed in vivo tumor growth as a single agent and preserved the chemotherapeutic effect of cisplatin in combination therapy

We then applied Y-27632 to an immunocompetent, syngeneic LLCab mouse model in which CIPN was induced. Drug treatment began when tumors were first palpable in mice (5 days after subcutaneous injection of LLCab cells). As expected, the tumor volume of the Saline group was significantly increased over the course of experiment (Figure. 2A). Cisplatin treatment suppressed the rapid growth of tumor, and this was first evident at day 23 post LLCab cell injection. Y-27632 treatment started to show significant effects of suppression on tumor growth at day 27 when compared to Saline group (Figure. 2A). Compared with Saline group, the trend of Y-27632-inudced tumor volume suppression further improved. The result of Cis+Y-27632 treatment group showed that Y-27632 preserved the antineoplastic effect of cisplatin (Figure. 2A).

Figure 2. Y-27632 suppressed tumor growth in vivo and promoted cisplatin-induced apoptosis in the tumor tissues.

(A). Drug treatment began on day 5 post LLCab injection. Day 6 to Day 20, n=10 animals/all groups. Day 20 to Day 30: n=10 animals/group Saline, Y-27632 and Cis+Y-27632, n=8 animals/group Cisplatin. Values represent mean±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 relative to Saline; Δp<0.05, ΔΔΔΔp<0.0001, relative to Y-27632. (B and C). Images of anti-Ki67 (B) and TUNEL (C) immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissues from all treatment groups. Scale bar: 30μm. (D). Density analysis of anti-Ki67 positive cells in the tumor tissues. Values represent mean±SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001, relative to Saline; •••p<0.005, relative to Y-27632; Δp<0.05, relative to Cisplatin. (E). Density analysis of TUNEL positive cells in the tumor tissues. Values represent mean±SEM. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 relative to Saline; ••p<0.01, relative to Y-27632; Δp<0.05, relative to Cisplatin.

Y-27632 induced apoptosis of tumor cells and enhanced the effects of cisplatin-induced tumor cell death in vivo

To further investigate the molecular basis underlying the tumor suppression by cisplatin and Y-27632, tumor tissue sections were stained with antibodies that detect proliferative cells (Ki67) and apoptotic cells (TUNEL). A large population of Ki67 positive tumor cells was observed in the Saline group while a notably small population of Ki67 positive tumor cells was observed in the Cis+Y-27632 group (Figure. 2B; Ki67). Quantification analysis of proliferative cells in the tumor tissue from each group (Figure. 2D) revealed that cisplatin treatment reduced the number of proliferative tumor cells when compared to saline treatment. Cis+Y-27632 group produced greater anti-proliferative effect on Ki67 positive tumor cells than either cisplatin or Y-27632 treatment alone.

Cisplatin treatment led to a significantly increased number of TUNEL positive cells when compared to the Saline group (Figure. 2C; TUNEL). On the other hand, a drastically increased number of TUNEL positive cells was observed in the Cis+Y-27632 group when compared to the other three treatment groups (Figure. 2C; TUNEL). Quantification analysis of TUNEL positive cells in the tumor tissue (Figure. 2E) confirmed that Y-27632 alone induced apoptosis of tumor cells. Furthermore, Cis+Y-27632 group showed the highest number of apoptotic cells in the tumor tissues when compared to that of cisplatin or Y-27632 single treatment group. Western Blot analysis on tumor tissue lysate collected from each treatment group indicated that cleaved PARP was increased in all three (Cisplatin, Y-27632 and Cis+Y-27632) treatment groups in comparison to the Saline group (SI Figure. 1B). These findings were consistent with our in vitro Cleaved-PARP Western Blot result (Figure. 1A and 1B). Therefore, apoptosis may play a key role in the tumor suppressive effect of Y-27632 treatment.

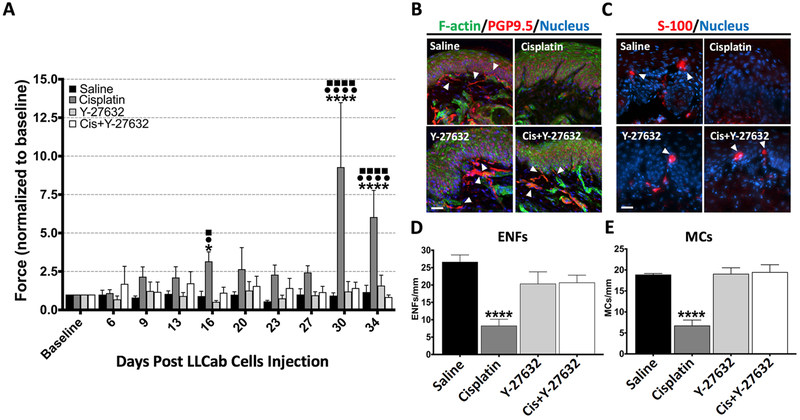

Y-27632 alleviated the reduction of touch sensitivity induced by cisplatin treatment in vivo

To assess whether weekly drug treatment altered the peripheral nervous system function in our tumor-bearing mouse model, Von Frey monofilament assay was carried out to evaluate the response from the mouse hind paw following cutaneous mechanical stimuli. The force (normalized to baseline) required to elicit a response was presented for each group in Figure 3A. Cisplatin-treated mice displayed a bi-phasic change in touch sensation compared to other treatment groups of mice. The 6μg/g cisplatin treatment regimen induced a decreased touch response initially (day 20) followed by a temporary reversal of the trend reminiscent of mechanical allodynia (day 23 to day 27 after LLCab cells injection). Thereafter, these mice exhibited a dramatic reduction in touch sensitivity indicating a sharp decline of sensory function in the peripheral nervous system. The Von Frey analysis further showed that the loss of touch sensitivity caused by cisplatin was prevented by Y-27632 treatment since no significant change of applied force was observed between Saline group and Cis+Y-27632 group. These results suggested that Y-27632 ameliorated the cisplatin-induced reduction in touch sensitivity in tumor-bearing mice.

Figure 3. Y-27632 ameliorated cisplatin-induced reduction of touch sensation and protected ENFs and Meissner corpuscles from cisplatin-induced impairment in the mouse hind paw.

(A).Von Frey analysis was conducted weekly on each treatment group of mice. Values represent mean±SEM. *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001, relative to Saline. •p<0.05, ••••p<0.0001, relative to Y-27632; ■p<0.05, ■■■■p<0.0001, relative to Cis+Y-27632. Baseline to Day 20: n=10 animals/all groups. Day 20 to Day 30: n=10 animals/group Saline, Y-27632 and Cis+Y-27632, n=8 animals/group Cisplatin. Day 30 to Day 34: n=10 animals/group Saline, n=9 animals/group Y-27632 and Cis+Y27632, n=7 animals/group Cisplatin. (B and C). Footpad tissues were excised and immunofluorescence analysis was performed with anti-PGP 9.5 (pan ENF marker) and anti-S-100 (schwann cells marker). ENFs and MCs were indicated with white arrowheads, F-actin were stained by FITC-Phalloidin and nuclei were indicated by Hoechst staining. Scale bar: 50μm. (D). Density analysis of anti-PGP9.5 positive ENFs in the footpad tissues from each treatment group. Values represent mean±SEM. ****p<0.0001, relative to Saline. n=5 animals per each treatment group. (E). Density analysis of MCs in the footpad tissues from each treatment group. Values represent mean±SEM. ****p<0.0001, relative to Saline. n=5 animals per each treatment group.

Y-27632 protected ENFs and Meissner corpuscles from cisplatin-induced impairment

Found between the epidermis and dermis of skin, small cutaneous nerve fibers, referred as epidermal nerve fibers (ENFs) and heavily myelinated Meissner corpuscles (MCs), are in charge of transmitting touch sensations from body extremities to the brain . Based on the characteristic histological differences between ENFs and MCs(31,32), antibodies for detecting neuronal axons (PGP9.5) and myelin sheath (S-100) were applied to investigate the density of total ENFs and MCs, in the tumor-bearing mouse foot pad tissues. Confocal microscopic images of foot pad tissues acquired from each treatment group (Figure. 3B) revealed numerous ENFs in the Saline and Y-27632 groups while notably fewer ENFs were found in the Cisplatin group. Combined treatment of Y-27632 with cisplatin prevented the loss of ENFs in the foot pad tissues. Furthermore, density analysis of nerve fibers confirmed a significant reduction of total ENFs (Figure. 3D) in the Cisplatin group, which was prevented by the treatment of Y-27632.

As another important mechanoreceptor in the skin (33), all MCs encapsulate unmyelinated nerve endings and are wrapped around by heavily myelinated sheath. In the current study, MCs were frequently seen between dermal papillae in the footpad tissues of Saline group (Figure. 3C). Cisplatin treatment resulted in a notable paucity of MCs. On the contrary, number of MCs were restored in both Y-27632 and Cis+Y-27632 groups (Figure. 3C). Moreover, density analysis of MCs indicated that Y-27632 treatment prevented the cisplatin-elicited MCs reduction in the mouse hind paw (Figure. 3E). These observations, which corroborate with the results from Von Frey analysis, indicated that the loss of touch sensitivity was a dominant manifestation of CIPN at the end of the treatment course in our tumor-bearing mouse model and Y-27632 treatment was capable of preventing this peripheral neurotoxicity.

Y-27632 attenuated cisplatin-induced dysregulation of cellular stress (inflammation/DNA repairing/oxidative stress) associated protein profile and the hyper-activation of NF-κB in mouse footpad tissues

To gain unbiased insights of potential mechanisms by which Y-27632 ameliorates CIPN in the body extremities, mouse foot pads were micro-dissected and tissue lysates were collected from each treatment group for quantitative proteomic analysis (Figure.4A). An average of over 2134 proteins were identified in an individual treatment group, with 66 of them showing the statistically significant up- or down-regulation across all treatment groups by ANOVA (p-value < 0.05; n=4: 4 independent mice per each treatment group). Further analysis focused on protein overexpression revealed that a wide range of proteins were upregulated by cisplatin treatment but Cis+Y-27632 treatment was able to revert them towards the level of saline treated group (Figure. 4B; SI Table IV).

Figure 4. Y-27632 attenuated the cisplatin induced inflammation/DNA repairing/oxidative stress responses in the mouse foodpad tissues.

(A). Hierarchical clustering of the z-score normalized log2 label-free quantification (LFQ) values averaged across four biological replicates for ANOVA significant proteins (p-value <0.05). Protein levels correspond to the color scale. A color gradient from red to blue represented a high level to low level of proteomic responses (grey = missing data). (B). Ratio of protein expression level change of each treatment group compared to Saline group. Listed proteins were all upregulated by cisplatin treatment while being reverted towards control level under Cis+Y-27632 combination treatment. (C). Footpad tissues were stained with anti-DHFR, anti-SMC1a, anti-HMGCS2 and anti-AKAP8 antibodies. ENFs were revealed by anti-PGP9.5 antibody and were indicated by white arrowheads, and nuclei were indicated by Hoechst staining. Scale bar: 30μm. (D). STRING analysis revealed the interaction network of cisplatin induced-upregulated gene encoded proteins with RhoA-NF-κB signaling axis (inside red circle). (E). Western blot analysis of footpad tissue lysates collected from each treatment group. Among the expression of Stat3, phospho-Stat3, NF-κB and phospho-NF-κB, phospho-NF-κB was most dramatically increased. (F). Quantification analysis of the ratio of pNF-κB/NF-κB in all treatment groups. Values represent mean±SEM. **p<0.0001, relative to Saline. N=5 animals per each treatment group.

Analyses of protein database indicated that cisplatin treatment upregulated DNA repairing associated proteins, such as Smc1a(34)(SI Table IV). Upregulation was also observed for the groups of proteins, such as DHFR(35), HMGCS2(36) and Nqo1(37), that are associated with the response of oxidative stress. In addition, cisplatin treatment triggered upregulation of proteins associated with cellular stress (e.g. Hspa4l) (38) and inflammation responses (e.g. Akap8)(39). Y-27632 treatment, in the presence of cisplatin, was able to attenuate the overexpression of these cisplatin-induced proteins (Figure. 4B). To investigate the potential association between cisplatin-upregulated proteins with peripheral nerual structures, such as ENFs, immunofluorescent analysis was conducted on the non-treated mouse foot pad tissues. Results indicated that DHFR, SMC1a, and AKAP8 were primarily expressed in the epidermis and were not associated with ENFs (Figure. 4C, DHFR, SMC1a, and AKAP8). DHFR demonstrated a cytoplasmic distribution among non-keratinized epithelial cells. A ring-shape staining pattern was observed for SMC1a, indicating its perinuclear localization in the non-keratinized epithelial cells. AKAP8 was only localized in a selected group of non-keratinized epithelial cells. Interestingly, HMGCS2 was not only expressed in the cytoplasm of non-keratinized epithelial cells in the epidermis but was also co-localized with ENFs (Figure. 4C, HMGCS2; Arrowheads). Thus, this data indicate that cisplatin-induced cellular stress impacted both the epidermal cells and ENFs in the mouse foot pad.

Cisplatin-induced inflammatory reaction inflicted damage on the peripheral nerve system, and cytokines released from these reactions were capable of activating NF-κB (13,40,41). Since NF-kB activation also interacts with RhoA signaling pathway (14), we explored the potential interactions between all cisplatin upregulated proteins with RhoA and NF-κB signaling pathways by using STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) to predict protein-protein associations. Many cisplatin upregulated proteins were associated with RhoA and NF-κB signaling pathways (Figure 4D: Red Circle). Next, we sought to determine the activity of NF-κB and the proteins associated with NF-κB signaling pathway in the mouse foot pad tissue. Cisplatin treatment resulted in significant increases of activated NF-κB (Figure. 4E and 4F). Y-27632 treatment attenuated the hyper-activation of NF-κB induced by cisplatin, further validating the upregulation of inflammatory signaling and the protective effect of Y-27632 on the peripheral nerve system. The activity of Stat3 remained unchanged among all treatment groups; therefore, cisplatin induced the hyper-activation of NF-κB without affecting the Stat3 signaling.

Discussion

While the number of cancer survivors has increased significantly in recent years, CIPN still has a grave impact on the quality of life in cancer survivors (42). Therefore, it is important to identify better treatment strategies to minimize CIPN, while maintaining the cancer suppressing effects of chemotherapeutic drugs.

Suppression of small GTPase RhoA signaling, either through inhibition of its upstream p75NTR or the downstream effector Rho kinase/p160ROCK, reversed and prevented experimental CIPN in non-tumor bearing mice (8,23). The current study demonstrated, for the first time, that Y-27632 had dual therapeutic effects on tumor suppression and peripheral neuroprotection in a immunocompetent, tumor-bearing CIPN mouse model. Our findings are consistent with the previous in vitro observation that suppression of RhoA signaling pathway elicits antineoplastic effects (43). While the effect of Cis+Y-27632 treament was not significantly greater than the single cisplatin treatment on tumor volume which also contained the necrotic cell debris, Y-27632 clearly promoted the cisplatin effect of reducing tumor cell proliferation and enhancing tumor cell apoptosis (Figure. 2B–E). We believe that ultimately, increased tumor cell apoptosis will result in tumor volume reduction in the combination treatment.

Previous literatures (45) and this study (SI Figure. 2) showed that different dosages of cisplatin treatment can result in different manifestation of peripheral neuropathy. In our study, although not statistically significant, the applied cisplatin treatment (6μg/g) induced a transient increase in response to Von Frey stimulation that soon gave way to the loss of touch sensitivity. On the contrary, the half dose of applied cisplatin treatment (3μg/g) led to a prolonged phase of mechanical allodynia before the mouse responses to Von Frey stimuli subside (SI Figure. 2). These results were consistent with the literature (45), which revealed that high dosage of cisplatin treatment produces numbness whereas lower dosage of cisplatin cause mechanical allodynia first followed by the recovery. Therefore, we hypothesized that, under our experimental condition, CIPN in the tumor-bearing mice undergoing high cumulative cisplatin treatment has rapidly progressed to the stage that loss of touch sensation may represent the numbness of human cancer patients suffering from chronic CIPN (44,45). In our model, cisplatin treatment caused a significant decrease in the density of touch sensory associated-ENFs and MCs, which could be prevented by Y-27632 treatment. These data support the notion that the pathogenesis of CIPN in our model is bi-phasic, with a transient mechanic allodynia period declining quickly to the terminal loss of touch sensation. We hypothesize that Y-27632 may be able to prevent the loss of touch sensation aspect of CIPN similar to the numbness in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

As a key regulator of inflammation, NF-κB is involved in a variety of important biological functions. During tumorigenesis and metastasis, activated NF-κB increases the number of DNA-damaged cells but enhances cancer cell proliferation and survival (46), and activation of RhoA pathway promoted tumorigenesis through NF-κB (47). In addition, NF-κB also plays a pivotal role in the development of chemoresistance, especially cisplatin resistance (48). For instance, cisplatin treatment significantly increased NF-κB activity in prostate cancer cells, which leads to chemoresistance. Genistein, an AKT-NF-κB inhibitor, abolished the NF-κB-induced chemoresistence in murine models (30). Moreover, activation of NF-κB signaling by p53 deficiency and KRAS mutation promotes chemoresistance and tumorigenesis in lung cancer cells (49). Meanwhile, activation of RhoA by p120 mutation led to an increased activation of NF-κB in the mouse skin (50), and the inhibition of RhoA pathway prevented pathogenesis of pemphigus vulgaris through NF-κB pathway (51). Additonally, inhibition of NF-κB activity attenuated increased pain sensitivity in a rodent model of inflammation (52). Therefore, RhoA signaling pathway interacts with NF-κB biological network (14) and may play an important role in CIPN as demonstrated in the current study. It is possible that Y-27632 promoted PARP-mediated cancer cell death independent of NF-κB signaling, thereby improving the tumor suppressive effect of cisplatin, decreasing potential NF-κB-induced chemoresistance, while preventing the injury of ENFs and MCs caused by cisplatin (Figure. 5). Our study thus highlights the potential of developing Y-27632 or its optimized analogs as a promising adjuvant with cisplatin treatment. We can now further investigate the mechanisms underlying RhoA-NF-κB signaling pathway in preventing CIPN and prepare for potential clinical applications.

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of potential therapeutic mechanisms of Y-27632 on cisplatin-induced suppression of lung cancer and its neuroprotective roles in the peripheral nerves.

Cisplatin suppresses tumor growth but also induces cellular stress. At the peripheral nerve-epidermis interface in the mouse footpad, cisplatin-induced RhoA activation increases NF-κB hyper-activation, which led to peripheral neuropathy. Functional inhibition of RhoA signaling pathway by Y-27632 can promote cancer cell apoptosis, decrease NF-κB-induced chemoresistance, and prevent the loss of ENFs in the mouse footpad.

Supplementary Material

Implications:

This study, for the first time, demonstrated the dual anti-neoplastic and neuroprotective effects of Rho kinase/p160ROCK inhibition in a syngeneic immunocompetent tumor-bearing mouse model, opening the door for further clinical adjuvant development of RhoA-NF-κB axis to improve chemotherapeutic outcomes.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Kori Brewer and Dr. Yan-Hua Chen for guidance. We also thank Joani Zary Oswald, Jered Cope Meyers, Rodney Tatum, Zachary Elliott and Taylor Alexandra Leposa for technical assistance. This work was supported in part by grants from National Cancer Institute CA111891 (QL) and CA165202 (QL and KV) and the Harriet and John Wooten Foundation for Neurodegenerative Diseases Research MT7955 (QL). This research is based in part upon work conducted at UNC Proteomics Core Facility supported in part by National Cancer Institute CA016086 to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Bennett GJ, Doyle T, Salvemini D. Mitotoxicity in distal symmetrical sensory peripheral neuropathies. Nature reviews Neurology 2014;10(6):326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staff NP, Grisold A, Grisold W, Windebank AJ. Chemotherapy - Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Current Review. Annals of Neurology 2017;81(6):772–81 doi 10.1002/ana.24951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang H, Zhu L, Reid BR, Drobny GP, Hopkins PB. Solution structure of a cisplatin-induced DNA interstrand cross-link. Science 1995;270(5243):1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald ES, Randon KR, Knight A, Windebank AJ. Cisplatin preferentially binds to DNA in dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro and in vivo: a potential mechanism for neurotoxicity. Neurobiology of disease 2005;18(2):305–13 doi 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubreuil CI, Marklund N, Deschamps K, McIntosh TK, McKerracher L. Activation of Rho after traumatic brain injury and seizure in rats. Experimental neurology 2006;198(2):361–9 doi 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita T, Tohyama M. The p75 receptor acts as a displacement factor that releases Rho from Rho-GDI. Nature neuroscience 2003;6(5):461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu Q, Longo FM, Zhou H, Massa SM, Chen Y-H. Signaling through Rho GTPase pathway as viable drug target. Current medicinal chemistry 2009;16(11):1355–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friesland A, Weng Z, Duenas M, Massa SM, Longo FM, Lu Q. Amelioration of Cisplatin-Induced Experimental Peripheral Neuropathy by a Small Molecule Targeting p75. Neurotoxicology 2014;45:81–90 doi 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James SE, Burden H, Burgess R, Xie Y, Yang T, Massa SM, et al. Anti-cancer drug induced neurotoxicity and identification of Rho pathway signaling modulators as potential neuroprotectants. Neurotoxicology 2008;29(4):605–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellenbroek SI, Collard JG. Rho GTPases: functions and association with cancer. Clinical & experimental metastasis 2007;24(8):657–72 doi 10.1007/s10585-007-9119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-kappaB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5(10):749–59 doi 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010;140(6):883–99 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu LY, Zhou Y, Cui WQ, Hu XM, Du LX, Mi WL, et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) dependent microglial activation promotes cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice. Brain Behav Immun 2018;68:132–45 doi 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong L, Tergaonkar V. Rho protein GTPases and their interactions with NFkappaB: crossroads of inflammation and matrix biology. Biosci Rep 2014;34(3) doi 10.1042/BSR20140021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Posekany KJ, Pittman HK, Bradfield JF, Haisch CE, Verbanac KM. Induction of Cytolytic Anti-Gal Antibodies in α-1,3-Galactosyltransferase Gene Knockout Mice by Oral Inoculation with Escherichia coli O86:B7 Bacteria. Infection and Immunity 2002;70(11):6215–22 doi 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6215-6222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boykin C, Zhang G, Chen YH, Zhang RW, Fan XE, Yang WM, et al. Cucurbitacin IIa: a novel class of anti-cancer drug inducing non-reversible actin aggregation and inhibiting survivin independent of JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation. Br J Cancer 2011;104(5):781–9 doi 10.1038/bjc.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verdú E, Vilches JJ, Rodríguez FJ, Ceballos D, Valero A, Navarro X. Physiological and immunohistochemical characterization of cisplatin-induced neuropathy in mice. Muscle & nerve 1999;22(3):329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owonikoko TK, Zhang G, Deng X, Rossi MR, Switchenko JM, Doho GH, et al. Poly (ADP) ribose polymerase enzyme inhibitor, veliparib, potentiates chemotherapy and radiation in vitro and in vivo in small cell lung cancer. Cancer medicine 2014;3(6):1579–94 doi 10.1002/cam4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho I-L, Kuo K-L, Chang H-C, Hsieh J-T, Wu J-T, Chiang C-K, et al. MLN4924 synergistically enhances cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity via JNK and Bcl-xL pathways in human urothelial carcinoma. Scientific reports 2015;5:16948 doi 10.1038/srep16948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu D-D, Wang C-T, Shi H-S, Li Z-Y, Pan L, Yuan Q-Z, et al. Enhancement of cisplatin sensitivity in Lewis Lung carcinoma by liposome-mediated delivery of a survivin mutant. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2010;29(1):46 doi 10.1186/1756-9966-29-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang S, Peng X, Li X, Yang P, Xie L, Li Y, et al. Silencing of CXCR4 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to cisplatin. Oncotarget 2015;6(2):1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doppler K, Werner C, Sommer C. Disruption of nodal architecture in skin biopsies of patients with demyelinating neuropathies. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System 2013;18(2):168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James SE, Dunham M, Carrion-Jones M, Murashov A, Lu Q. Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 facilitates recovery from experimental peripheral neuropathy induced by anti-cancer drug cisplatin. Neurotoxicology 2010;31(2):188–94 doi 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett GJ, Liu GK, Xiao WH, Jin HW, Siau C. Terminal arbor degeneration–a novel lesion produced by the antineoplastic agent paclitaxel. European Journal of Neuroscience 2011;33(9):1667–76 doi 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyette-Davis J, Dougherty P. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Experimental neurology 2011;229(2):353–7 doi 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doss AL, Smith PG. Langerhans cells regulate cutaneous innervation density and mechanical sensitivity in mouse footpad. Neuroscience letters 2014;578:55–60 doi 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Chen X, Meng Q, Jing H, Lu H, Yang Y, et al. MiR-181b regulates cisplatin chemosensitivity and metastasis by targeting TGFbetaR1/Smad signaling pathway in NSCLC. Sci Rep 2015;5:17618 doi 10.1038/srep17618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver TG, Mercer KL, Sayles LC, Burke JR, Mendus D, Lovejoy KS, et al. Chronic cisplatin treatment promotes enhanced damage repair and tumor progression in a mouse model of lung cancer. Genes Dev 2010;24(8):837–52 doi 10.1101/gad.1897010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuang S-E, Yeh P-Y, Lu Y-S, Lai G-M, Liao C-M, Gao M, et al. Basal levels and patterns of anticancer drug-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and its attenuation by tamoxifen, dexamethasone, and curcumin in carcinoma cells. Biochemical pharmacology 2002;63(9):1709–16 doi 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Ahmed F, Ali S, Philip PA, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Inactivation of Nuclear Factor κB by Soy Isoflavone Genistein Contributes to Increased Apoptosis Induced by Chemotherapeutic Agents in Human Cancer Cells. Cancer Research 2005;65:6934–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009;139(2):267–84 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lumpkin EA, Caterina MJ. Mechanisms of sensory transduction in the skin. Nature 2007;445(7130):858 doi 10.1038/nature05662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman A, Bai L, Ginty DD. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science 2014;346(6212):950–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He M, Lin Y, Tang Y, Liu Y, Zhou W, Li C, et al. miR-638 suppresses DNA damage repair by targeting SMC1A expression in terminally differentiated cells. Aging 2016;8(7):1442–56 doi 10.18632/aging.100998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes L, Carton R, Minguzzi S, McEntee G, Deinum EE, O’Connell MJ, et al. An active second dihydrofolate reductase enzyme is not a feature of rat and mouse, but they do have activity in their mitochondria. FEBS Lett 2015;589(15):1855–62 doi 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rardin MJ, He W, Nishida Y, Newman JC, Carrico C, Danielson SR, et al. SIRT5 regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic networks. Cell Metab 2013;18(6):920–33 doi 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou GD, Randerath K, Donnelly KC, Jaiswal AK. Effects of NQO1 deficiency on levels of cyclopurines and other oxidative DNA lesions in liver and kidney of young mice. Int J Cancer 2004;112(5):877–83 doi 10.1002/ijc.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pennarossa G, Maffei S, Rahman MM, Berruti G, Brevini TA, Gandolfi F. Characterization of the constitutive pig ovary heat shock chaperone machinery and its response to acute thermal stress or to seasonal variations. Biol Reprod 2012;87(5):119 doi 10.1095/biolreprod.112.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall EA, Zavzavadjian JR, Chang MS, Randhawa B, Zhu X, Hsueh RC, et al. Suppression of LPS-induced TNF-alpha production in macrophages by cAMP is mediated by PKA-AKAP95-p105. Sci Signal 2009;2(75):ra28 doi 10.1126/scisignal.2000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Areti A, Yerra VG, Naidu V, Kumar A. Oxidative stress and nerve damage: role in chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy. Redox Biol 2014;2:289–95 doi 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang XM, Lehky TJ, Brell JM, Dorsey SG. Discovering cytokines as targets for chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Cytokine 2012;59(1):3–9 doi 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park SB, Goldstein D, Krishnan AV, Lin CSY, Friedlander ML, Cassidy J, et al. Chemotherapy‐induced peripheral neurotoxicity: A critical analysis. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2013;63(6):491–37 doi 10.1002/caac.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuoka T, Yashiro M. Rho/ROCK signaling in motility and metastasis of gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG 2014;20(38):13756 doi 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaggi AS, Singh N. Mechanisms in cancer-chemotherapeutic drugs-induced peripheral neuropathy. Toxicology 2012;291(1):1–9 doi 10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cata JP, Weng H-R, Dougherty PM. Behavioral and electrophysiological studies in rats with cisplatin-induced chemoneuropathy. Brain research 2008;1230:91–8 doi 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taniguchi K, Karin M. NF-kappaB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2018. doi 10.1038/nri.2017.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim JG, Choi KC, Hong CW, Park HS, Choi EK, Kim YS, et al. Tyr42 phosphorylation of RhoA GTPase promotes tumorigenesis through nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB. Free Radic Biol Med 2017;112:69–83 doi 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Godwin P, Baird AM, Heavey S, Barr MP, O’Byrne KJ, Gately K. Targeting nuclear factor-kappa B to overcome resistance to chemotherapy. Front Oncol 2013;3:120 doi 10.3389/fonc.2013.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang L, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhou J, Wu Y, Cui Y, et al. Mutations of p53 and KRAS activate NF-kappaB to promote chemoresistance and tumorigenesis via dysregulation of cell cycle and suppression of apoptosis in lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett 2015;357(2):520–6 doi 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Moreno M, Davis MA, Wong E, Pasolli HA, Reynolds AB, Fuchs E. p120-catenin mediates inflammatory responses in the skin. Cell 2006;124(3):631–44 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang J, Zeng X, Halifu Y, Chen W, Hu F, Wang P, et al. Blocking RhoA/ROCK inhibits the pathogenesis of pemphigus vulgaris by suppressing oxidative stress and apoptosis through TAK1/NOD2-mediated NF-kappaB pathway. Mol Cell Biochem 2017;436(1–2):151–8 doi 10.1007/s11010-017-3086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartung JE, Eskew O, Wong T, Tchivileva IE, Oladosu FA, O’Buckley SC, et al. Nuclear factor-kappa B regulates pain and COMT expression in a rodent model of inflammation. Brain Behav Immun 2015;50:196–202 doi 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.