Abstract

Soy is one of the most common sources of protein in many commercial formulas for laboratory rodent diets. Soy contains isoflavones, which are estrogenic. Therefore, soy-containing animal diets might influence estrogen-regulated systems, including basal behavioral domains, as well as affective behavior and cognition. Furthermore, the isoflavone content of soy varies, potentially unpredictably confounding behavioral results. Therefore researchers are increasingly considering completely avoiding dietary soy to circumvent this problem. Several animal studies have investigated the effects of soy free diets but produced inconsistent results. In addition, most of these previous studies were performed in outbred rat or mouse strains. In the current study, we assessed whether a soy-free diet altered locomotion, exploration, nesting, anxiety-related behaviors, learning, and memory in C57BL/6 mice, the most common inbred strain used in biomedical research. The parameters evaluated address measures of basic health, natural behavior, and affective state that also are landmarks for animal welfare. We found minor differences between feeding groups but no indications of altered welfare. We therefore suggest that a soy-free diet can be used as a standard diet to prevent undesirable side effects of isoflavones and to further optimize diet standardization, quality assurance, and ultimately increase the reproducibility of experiments.

The composition of laboratory diets is essential for the health and wellbeing of all laboratory animals. Diets are carefully optimized to supply the necessary nutrients, minerals, and trace elements. In many formulas for rodent nutrition, soy is used as a plant-derived source of protein. However, soy also contains high amounts of isoflavones, a class of phytoestrogens.9,33 Due to chemical structural similarities to the most potent estrogen 17-β-estradiol, isoflavones are capable of mimicking the actions and functions of 17-β-estradiol and thus trigger estrogenic or antiestrogenic effects.10,25 Therefore, the effects of isoflavones on estrogen-modulated systems, for example, cardiovascular, skeletal, reproductive, and nervous systems,37 can potentially influence the outcome of in vivo experiments. One comprehensive review15 emphasizes the possible interference of dietary isoflavone levels with experimental results. The concentration of isoflavones can differ substantially between different formulas—from approximately 80 µg/g chow to more than 500 µg/g—but also between batches of the same formula.15 Not only the doses of isoflavones but also the timing and duration of exposure could considerably influence experimental results.26,27 An analysis of isoflavone levels that assessed these parameters could provide helpful information to detect isoflavone-evoked effects and could contribute to an understanding of variability in experimental results.15 However, determining the isoflavone concentrations of feeds is considerably labor- and cost-intensive.

Another consequence that many investigators are considering in light of such observations is the complete avoidance of soy in rodent diet formulas, thereby avoiding soy isoflavone exposure of the animals. The effects of isoflavones on development and behavior have already been investigated in several studies, but their focus was mostly on rats, especially females.15,20,21,29 Here, we performed a broad behavioral investigation of the most widely used inbred mouse strain, C57BL/6, in both sexes. Due to the frequent use of this strain in various scientific disciplines, this behavioral assessment likely is of major interest.

We therefore extensively evaluated mice that received a standard soy-containing diet or a soy-free diet to identify alterations of behavior and to estimate the potential influence of isoflavones on the results. Although the exclusion of soy as a confounding factor might be beneficial in terms of the scientific outcome, we also were interested in potential effects on the wellbeing of the mice. Therefore this study also included measures indicating the welfare of the animals, for example, nesting and anxiety- and depression-related parameters.

Materials and Methods

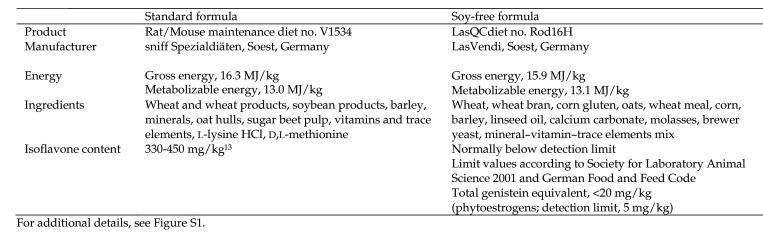

All experimental animals were bred in the SPF animal facility of the Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim, Germany. The parent generation of C57BL/6 N Crl mice (Charles River Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany) was fed with the same diet as their future offspring for at least 3 wk before mating. Male (n = 12) and female (n = 12) littermates were then randomly selected for the feeding experiment according to the feeding scheme of the parental generation: either a soy-free (LasQCdiet Rod16-H, LasVendi, Soest, Germany) or a soy-containing standard (Rat/Mouse Maintenance V1534, sniff Spezialdiäten, Soest, Germany) mouse diet. Details of the diets are listed in Figure 1, with additional information in (Supplemental Figure S1). The mice were fed with the corresponding diet throughout their lifespan.

Figure 1.

Diets used to feed the mice throughout their lifetimes.

At 8 wk after birth, the subjects were transferred to sex-specific colony rooms and allowed to acclimate for 14 d before behavioral testing. The reversed dark:light cycle was set to 12:12 h, with lights off at 0700, the room temperature to 23 ± 2 °C, and relative humidity to 50% ± 5%.

Mice were reared single-housed in conventional cages (Macrolon type II, 26 × 20 × 14 cm) and were provided with bedding (Espen bedding medium, ABEDD Lab and Vet, Vienna, Austria), nesting material (unbleached cellulose tissue, Pharmacy Stadtklinik, Frankenthal, Germany), and untreated tap water and food without restriction. Housing conditions allowed visual and olfactory contact between counterparts. Body weight was assessed during the weekly cage changes for 8 wk, starting at the arrival in the colony room until the end of the experiments. All experiments were conducted during the active phase of the mice, except for the nest test, due to its experimental demands. All experiments complied with regulations covering animal experimentation within the European Union (European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/EU) and were approved by German animal welfare authorities (Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe, ethical approval number 35-9185-81-G-193-11).

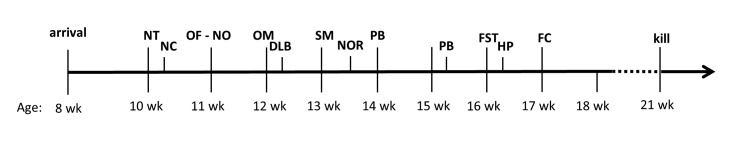

Experimental testing started 1 h after the onset of the dark, active phase and followed an individually randomized order for each test (Research Randomizer, http://www.randomizer.org). Animals were habituated to the experimental room for at least 30 min, except for the forced swim and fear-conditioning tests. Because the nest test requires observation of the home cage, this test was performed in the colony room. The test order was designed to start with the least aversive and to end with the more distressful experiments. Stress accumulation due to frequent testing was prevented by having a minimum of 48 h and a maximum of 7 d between experiments (Figure 2). For each test, we tested all mice on the same day, except for the puzzle box test, for which mice were separated into subgroups because of the temporal requirements of the test. Unless specified otherwise, all measures were performed manually.

Figure 2.

Sequence of experiments. NT, nest test; NC, novel cage test; OF-NO, open field–novel object test; OM, elevated O-maze test; DLB, dark–light test; SM, social memory test; NOR, novel object recognition test; PB, puzzle box test; FST, forced swim test; HP, hot plate test; FC, fear conditioning.

Nest test.

The test was performed as described previously.8 Briefly, a cotton square (Zoonlab, Castrop-Rauxel, Germany) was introduced into the home cage at 1 h before onset of the dark phase. Nest building was evaluated after 5 and 24 h, according to a rating scale based on nest cohesion and shape. Briefly, the rating scale ranged from 1 to 5: 1, nearly untouched cotton square; 2 and 3, increasingly shredded square; 4, a flat nest; and 5, a complex bowl-shaped nest.

Novel cage test.

Mice were placed into an ethanol-cleaned cage with a decreased amount of bedding (20 mL instead of the standard 600 mL) and were observed for 300 s under red light.32 The number of rears performed was recorded.

Open field–novel object test.

Mice were placed into an unfamiliar white arena (50 × 50 cm), which was illuminated from above (25 lx).43 Activity was recorded for 10 min. Subsequently a water-filled 50-mL conical tube (the novel object) was introduced into the center of the arena, and object exploration was recorded for 10 min. An image-processing system (EthoVision XT 8.0, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands) was used to analyze the distance moved, velocity, time spent moving, and time spent in center. Data regarding the latency to approach the novel object and the number of approaches were collected manually.

Elevated O-maze test.

Mice were placed into a walled section of an O-shaped gray plastic runway (width, 6 cm; outer diameter, 46 cm; 50 cm above the floor) with 2 walled (height, 10 cm) sections of gray polyvinyl that were placed opposite to each other.32 The floor of the apparatus was laminated with grip tape to prevent the mice from slipping. The setup was illuminated from above (25 lx). Mice were observed for 300 s, during which the latency to first exit, number of exits, and total time spent in the open compartments were recorded.

Dark–light test.

Mice were placed into the dark compartment of a 2-chamber setup in which the chambers were connected by a small tunnel.2 The dark compartment was made from black acrylic (20 × 15 cm) and covered by a lid, whereas the white chamber (30 × 15 cm) was illuminated from above (600 lx). Mice were observed for 300 s. The latency to the first exit, number of exits, and total time in the light compartment were assessed.

Novel object recognition test.

The novel objects protocol was modified from a previous study.3 Mice were familiarized with the empty arena (50 × 50 cm2, illuminated from above with 25 lx) for 10 min each at 1 day before testing and at 2 h before the first trial. Then they were introduced into the same arena but containing 2 identical items (a small candy glass or plastic cube) for 7 min or until they explored the objects for a total of 15 s. After an intertrial interval of 2 h, they were reintroduced for 5 min into the same arena, which now contained one familiar and one novel object, and the positions of the objects were changed to avoid bias. The number of approaches and time spent exploring were recorded.

Social memory test.

The social memory test was performed as previously described.13 Briefly, mice were tested in a 3-chamber (20 × 30 × 30 cm) social testing arena, in which the chambers were separated by clear acrylic walls containing rectangular openings (5 × 6 cm). The subject was habituated to the central chamber for 300 s before the acrylic panels were removed from the rectangular openings to allow exploration of the complete setup for 300 s. Carousel cages were then introduced into each of the lateral chambers, one containing an unfamiliar C57BL/6N mouse of matched age and sex. The subject was allowed to familiarize with the social partner for 10 min. Subsequently, either a familiar or an unknown social partner matched for age and sex was introduced into the compartments. The time spent with each mouse was assessed for 10 min. The side including the social partner was balanced systematically between subjects throughout the experiment.

Forced swim test.

Mice were placed for 6 min into a glass cylinder (height, 23 cm; diameter, 13 cm) filled with water (21 °C) to a height of 12 cm.22 Latency to immobility and percentage of time spent immobile were determined by using an image-processing system (EthoVision ×8, Noldus Information Technology). This test was conducted twice, with a 24-h intertrial interval.

Hot-plate test.

To assess pain threshold, the mice were placed on a 53 ± 0.3 °C hot plate (ATLab, Vendargues, France). The latency to the first coping reaction (that is, jumping or licking hindpaws) was assessed.5 If no reaction occurred within 45 s, the test was terminated.

Fear conditioning.

Contextual fear conditioning was performed in conditioning chambers (58 × 30 × 27 cm; TSE, Bad Homburg, Germany). The subject was habituated for 2 min to white noise in the chamber. Then an unconditioned stimulus (2-s continuous foot shock at 0.8 mA) was applied, accompanied by the presentation of a tone. After 24 h, freezing behavior in the same context was manually scored every 10 s for 5 min.

Puzzle box test.

The puzzle box test was performed as previously described.1 Briefly, the mouse was introduced into a brightly lit start zone (58 × 28 cm, 600 lux) of the puzzle box, from which it could travel to a goal zone (15 × 28 cm, covered). In 9 trials over 3 consecutive days, the passage through an underpath (4 cm) was modified through obstructions of increasing difficulty: trial 1) open door over the underpass location; trials 2 through 4, open underpath; trials 5 through 7, underpath was filled with sawdust (burrowing puzzle), and trials 8 and 9, underpath was blocked by a cardboard plug (plug puzzle). A trial started by placing the mouse in the start zone and ended when all 4 paws of the mouse entered the goal zone or after a total time of 5 min. The performance of mice in the puzzle box was assessed by measuring the latency to enter the goal zone.

Analysis of isoflavones in mouse serum samples.

Daidzein, genistein, and their corresponding phase II metabolites and of equol, equol-7-glucuronide, and equol-4ʹ-sulfate in mouse serum samples were analyzed by using a validated LC-MS method19,34,42 with the following minor alterations: mouse serum (100 μL) was thawed and 5 μL of internal standard solution (containing 5 μM 13C3-daidzein, 5 μM 13C3-genistein, 5 μM 13C3-daidzein-7-glucuronide, and 5 μM 13C3-genistein-7-glucuronide in DMSO) was added. The samples were diluted with 400 μL of water, and extraction and analysis was done as described previously.19,34,42 Briefly, an automated pipetting workstation (Microlab Star, Hamilton Robotics, Martinsried, Germany) was loaded with the water-diluted serum samples, and automated solid-phase extraction was performed by using a 96-well plate (Strata-X AW, 60 mg; Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). The eluates were evaporated to dryness by using a SpeedVac (model no. SPD131, Thermo Electron LED, Langenselbold, Germany), and the residues were dissolved in 200 μL 30% (v/v) methanol in water. Then the samples were filtered (0.45 μm glass fiber, 96-well plate; Phenomenex) and the filtrates injected to the UHPLC–MS–MS system. This system comprised a mass spectrometer (QTrap 5500, AB Sciex Germany, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with an LC system (Nexera, Shimadzu Europa, Duisburg, Germany). Analytes was separated on a Acquity HSS T3 column (internal diameter, 2.1 mm; length, 100 mm; particle size, 1.8 μm; Waters, Eschborn, Germany) with a precolumn (Acquity HSS T3; diameter, 2.1 mm; length, 5 mm; particle size, 1.8 μm; Waters) and a pre-inline filter (0.5 μm; Krudkatcher, Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). The column oven temperature was adjusted to 40 °C, and the flow rate was set to 0.5 mL/min. Gradient elution was performed by using an aqueous 40 mM ammonium formate buffer (pH 3) and an acetonitrile:methanol mixture (1:2.5, v:v) as solvents. The injection volume was 15 μL. The electrospray ionization source of the MS was operated in the negative mode, and the scheduled multiple-reaction monitoring mode was used to monitor the analytes. Limits of quantification are summarized in Supplemental Figure S2.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Differences were considered to be significant at a P value less than 0.05.

The data were analyzed through 2-way ANOVA with treatment and sex as factors or, when appropriate, by using repeated-measures ANOVA. Mann–Whitney U tests for independent samples and Wilcoxon tests for related samples were used to analyze nesting behavior.

We excluded the data from 2 soy-free–fed female mice that had high serum concentrations of isoflavone metabolites, indicating an unintended and undesirable isoflavone exposure. Therefore, the sample size for all experiments are: soy-free males, n = 12; standard-diet males, n = 12; soy-free females, n = 10; and standard-diet females, n = 12.

Results

Analysis of isoflavones in mouse serum samples.

The levels of daidzein, genistein, and their corresponding phase II metabolites and of equol, equol-7-glucuronide, and equol-4ʹ-sulfate in mouse serum were quantified (Table 1). The profiles of the isoflavone phase II metabolites were comparable to those described recently,31,32 except that in the proportions of monosulfates were substantially higher and the levels of monoglucuronides and sulfoglucuronides were lower in female than in male mice.

Table 1.

Serum concentrations (nM) of daidzein, genistein, and their corresponding phase II metabolites and of equol, equol-7-glucuronide, and equol-4’-sulfate as determined through LC-MS

| Standard formula | Soy-free formula | |||||||||||

| male (n = 12) | female (n = 12) | male (n = 12) | female (n = 10) | Effects (ANOVA) | ||||||||

| mean | 1 SD | mean | 1 SD | mean | mean | 1 SD | treatment | sex | treatment×sex | |||

| Daidzein | 126.6 | 58.6 | 94.2 | 44.4 | 10.5 | 5.3 | 5.9 | F1,42 = 83.113 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | ||

| Daidzein-4’-GlcA | 2.8 | 9.8 | 6.4 | 14.8 | ND | ND | NS | NS | NS | |||

| Daidzein-7-GlcA | 141.2 | 51.2 | 197.3 | 94.0 | ND | ND | F1,42 = 109.121 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | |||

| Daidzein-7,4’-diGlcA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Daidzein-4’-S | 27.1 | 21.2 | 56.0 | 28.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 2.3 | F1,42 = 51.883 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 8.747 P = 0.005 | F1,42 = 6.013 P = 0.018 | |

| Daidzein-7-S | 207.6 | 101.9 | 411.8 | 184.2 | 22.3 | 18.7 | 34.6 | 21.1 | F1,42 = 76.647 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 11.355 P = 0.002 | F1,42 = 5.021 P = 0.030 | |

| Daidzein-7,4’-diS | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Daidzein-7-GlcA-4’-S | 14.1 | 10.5 | 35.6 | 14.3 | ND | ND | F1,42 = 85.808 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 16.022 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 16.022 P < 0.001 | |||

| Daidzein-4’-GlcA-7-S | 0.6 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | ND | ND | F1,42 = 10.622 P = 0.002 | NS | NS | |||

| Daidzein aglycone equivalent | 520.1 | 236.1 | 802.5 | 368.1 | 34.5 | 29.3 | 44.4 | 29.0 | F1,42 = 87.521 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 4.838 P = 0.033 | F1,42 = 4.205 P = 0.047 | |

| Unconjugated daidzein (%) | 24.8 | 3.8 | 11.8 | 1.2 | 32.7 | 24.8 | 7.9 | 8.5 | NS | F1,42 = 22.491 P < 0.001 | NS | |

| Genistein | 46.0 | 17.1 | 29.3 | 13.7 | 1.7 | 3.6 | ND | F1,42 = 119.909 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 7.464 P = 0.009 | F1,42 = 5.021 P = 0.030 | ||

| Genistein-4’-GlcA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Genistein-7-GlcA | 140.2 | 65.2 | 206.9 | 102.9 | ND | ND | F1,42 = 88.525 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | |||

| Genistein-7,4’-diGlcA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Genistein-4’-S | 40.0 | 28.3 | 56.2 | 30.3 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.7 | F1,42 = 52.185 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | |

| Genistein-7-S | 188.6 | 97.8 | 378.3 | 186.8 | 19.5 | 16.3 | 28.7 | 12.2 | F1,42 = 65.392 P < 0.001 | F1,24 = 9.622 P = 0.003 | F1,42 = 7.923 P = 0.007 | |

| Genistein-7,4’-diS | 1.4 | 3.2 | ND | ND | ND | |||||||

| Genistein-7-GlcA-4’-S | 33.7 | 17.8 | 57.2 | 26.8 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 2.7 | F1,42 = 71.056 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 7.373 P = 0.010 | F1,42 = 4.342 P = 0.043 | |

| Genistein-4’-GlcA-7-S | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Genistein aglycone equivalent | 449.7 | 221.0 | 727.8 | 353.6 | 26.2 | 25.9 | 36.8 | 17.3 | F1,42 = 77.544 P < 0.001 | F1,42 = 5.200 P = 0.028 | F1,42 = 4.468 P = 0.041 | |

| Unconjugated genistein (%) | 10.9 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 10.3 | 28.6 | —a | NS | F1,42 = 3.857 P = 0.056 | NS | ||

| Equol | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||||||||

| Equol-7-GlcA | 458.8 | 243.5 | 349.2 | 178.1 | 3.0 | 10.2 | ND | F1,42 = 77.569 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | ||

| Equol-4’-S | 427.7 | 215.4 | 398.7 | 138.2 | 14.9 | 11.1 | 27.4 | 21.5 | F1,42 = 101.592 P < 0.001 | NS | NS | |

GlcA, β-d-glucuronide; ND, not determined; NS, nonsignificant; S, sulfate

Because the genistein aglycone concentrations in all samples of this group were below the limit of quantitation, the percentage of unconjugated genistein could not be calculate.

Isoflavones were detectable in all serum samples of mice that received the soy-free diet, but daidzein and genistein aglycone equivalent concentrations were 15 to 20 times lower than those in the standard diet group.

Evaluation of body weight, litter size, locomotion, and nesting.

The soy-free diet did not adversely affect the number or size of litters, in that 5 of the 6 breeding pairs on each diet successfully delivered a total of 65 offspring, which demonstrated a female:male ratio of 3.5:3.

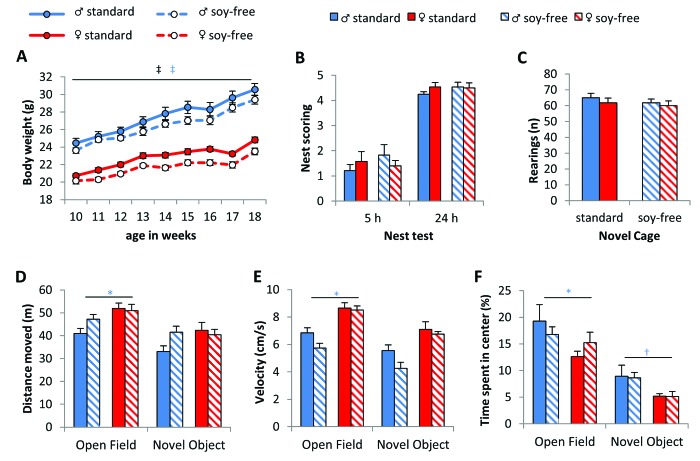

In general, mice fed the standard diet weighed more than those given the soy-free diet (treatment: F1,42 = 7.178, P = 0.010), and the differences in weight were statistically significant from week 12 onward. The gain in body weight was normal in both sexes (time: F8,336 = 232.674, P < 0.001; time×sex: F8,352 = 22.937, P < 0.001), with male mice being heavier (sex: F1,42 = 129.725, P < 0.001; Figure 3 A) independent of the diet.

Figure 3.

Body weight but not basal behavior is altered due to soy content of diet. (A) Mice fed with soy-free diet weighed significantly less than mice given soy-containing diet, and males weighed more than females. (B) Nest building behavior and (C) the number of rearings in the novel cage test were unaffected by diet and sex. (D) Distance moved, (E) velocity, and (F) time spent in the center were not altered by soy content but differed between sexes in the open-field and in part during the subsequent novel object test. Female mice moved farther, more quickly, and longer than male mice, which spent more time in the center. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; ‡, P < 0.001; time effect, black symbols; between treatments, red symbols; between sexes, blue symbols.

Nesting behavior was not affected by sex or diet (Figure 3 B). The quality of nests improved over time (all: Z = –5.922, P < 0.001; males: Z = –4.303, P < 0.001; females: Z = –4.117, P < 0.001; standard diet: Z = –4.295, P < 0.001; soy-free diet: Z = –4.123, P < 0.001). Locomotion did not differ between the treatment groups (Figure 3 C through F). Although no sex-associated differences were detectable in vertical activity in the novel cage test, female mice moved greater distances and at higher velocity than male mice in the open-field test (sex: distance, F1,44 = 8.018, P = 0.007; velocity: F1,44 = 7.949, P = 0.007; Figure 3 D and E). This effect was not detected in the subsequent novel object test. Although female mice spent less time in the center of the empty arena during the open-field test (sex: F1,42 = 5.664, P = 0.022) and during the novel object test (sex: F1,42 = 8.221, P = 0.006, Figure 3 F), neither sex nor diet influenced exploratory behavior directed toward the novel object (data not shown).

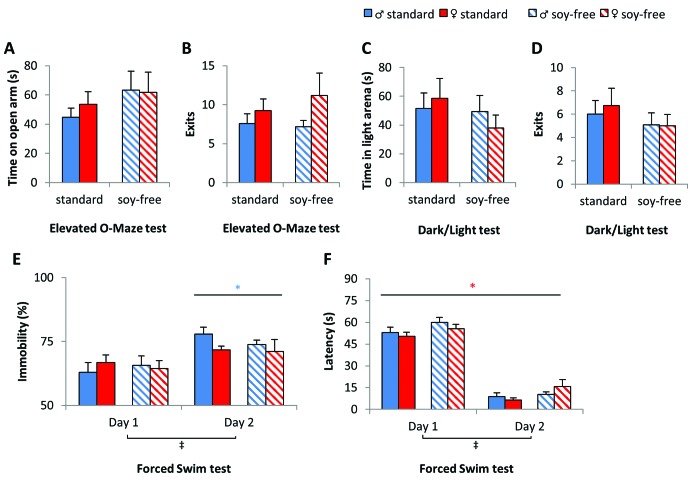

Effects of dietary soy on affective state.

The effect of dietary soy on affective behavior was heterogeneous. Anxiety-sensitive parameters in the Elevated O-Maze test and the dark–light test remained unchanged (Figure 4 A through D), but despair behavior in the forced swim test was slightly decreased in soy-free–fed mice. Repeated-measures analysis revealed a general increase of the latency to start floating in soy-free–fed compared with standard-fed mice (treatment: F1,42 = 4.928, P = 0.032) (Figure 4 F). Yet, this treatment-induced effect was not observed for the immobility parameter (Figure 4 E). Immobility increased significantly on day 2 compared with day 1, whereas latency decreased (day: latency, F1,42 = 67.458, P < 0.001; immobility, F1,42 = 686.572, P < 0.001; day×sex: F1,42 = 7.457, P = 0.009). Compared with females, male mice showed significantly more immobile behavior on day 2 (sex: day 2, F1,42 = 4.332, P = 0.044). Subsequent analyses for each sex did not reveal any significant differences between treatment groups.

Figure 4.

Dietary soy content influenced affective behavior. (A and B) Anxiety-related parameters in the elevated O-maze and (C and D) dark:light test were unaffected by dietary soy content, whereas (E and F) behavior in the forced swim test was mildly altered. (F) Soy-free–fed mice had a longer latency to start floating in general, with a more pronounced trend on day 2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; ‡, P < 0.001; time effect, black symbols; between treatments, red symbols; between sexes, blue symbols.

Effect of dietary soy on cognitive functions.

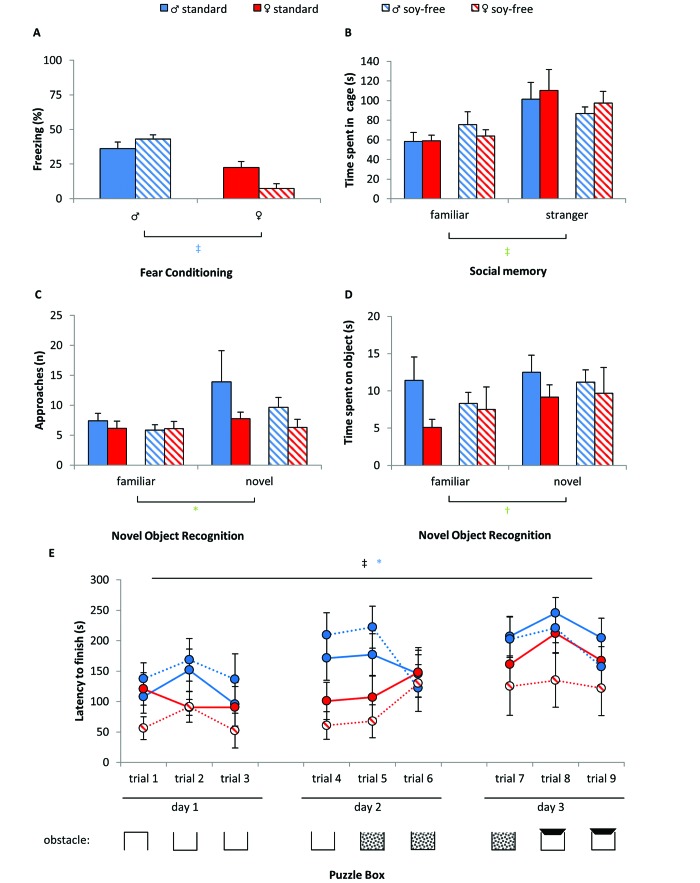

Treatment with soy-free diet did not alter cognitive abilities in tests of fear conditioning, social memory, or novel object recognition; neither did the soy-free diet alter executive functioning in the puzzle box test (Figure 5 A through D).

Figure 5.

Cognitive behavior was not dramatically affected by the soy-free diet. The outcome of (A) fear conditioning, (B) social memory, (C and D) novel object recognition, and (E) puzzle box tests was unaffected by treatment. However, sex-associated differences were detected in (A) fear conditioning and (E) puzzle box tests. (B) The nonfamiliar mouse was preferred over the familiar. (C and D) The novel object was preferred over the familiar one. (E) Performance changed over trials in the puzzle box test, in which female mice performed significantly better than males. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; *, P < 0.05; †, P < 0.01; ‡, P < 0.001; time effect, black symbols; between treatments, red symbols; between sexes, blue symbols; between familiar and unfamiliar, green symbols.

Compared with their male counterparts, female mice demonstrated a reduced context-dependent freezing response after fear conditioning (sex: F1,42 =37.108, P < 0.001). The pain threshold in the hot-plate test was similar between sexes (data not shown). Even though diet did not lead to differences between groups, it influenced the sex-specific outcome (treatment×sex: F1,42 = 7.454, P = 0.009). Whereas male mice fed the soy-free diet had the most frequent freezing behavior (mean ± SEM, 43.06% ± 4.78%), soy-free-fed females had the least (7.33% ± 3.36%).

In all tests based on recognition, novelty was preferred by all groups: an unfamiliar social partner in the social memory test (familiar: F1,41 = 19.262, P < 0.001) and the number of approaches (familiar: F1,42 = 5.314, P = 0.006) and the time spent near a novel object (familiar: F1,42 = 12.299, P = 0.001) in the novel object recognition test. This pattern depicts the natural behavior of mice toward novel conditions and is a basis for the analysis of differences between the groups. We did not find sex- or treatment-dependent effects on Social Memory and Novel Object Recognition.

Dietary soy content did not influence executive functions or problem solving in the puzzle box test (Figure 5 E). A general improvement of responses over time indicated successful learning in all mice (training: F8,336 = 7.490, P < 0.001). However, female mice acquired the task more quickly than males (training×sex: F8,336 = 2.225, P = 0.025) and were able to solve the tasks in significantly less time (sex: F1,42 = 5.361, P = 0.026). This outcome was most pronounced in trial 4 (F1,44 = 9.488, P = 0.004) and trial 5 (F1,44 = 12.621, P = 0.001).

Discussion

Whether to include or omit soy in laboratory animal diets continues to be debated. Some investigators argue that the removal of soy circumvents possible interference by estrogen-modulated properties, others do not want to exclude soy from their experiments or to exclude it only under certain circumstances, depending on the specific research focus.15,28,40 The aim of the current study was—by focusing on welfare, affective, and cognitive parameters—to provide a scientific basis to support evidence-based decision-making regarding the most suitable diet instead of choosing the approach of ‘one size fits all.’ Accordingly, we did not aim to detect which component of soy (for example, isoflavones) was likely to initiate possible changes. We want to emphasize that soy itself or its metabolites might be responsible for observed effects; for example, administration of the soy metabolite βCGα (323–333) elicits anxiolytic effects.31 When we looked at the serum levels of isoflavones and their metabolites, we found the expected sex-associated differences, supporting previous findings.36 Although not within the scope of our project, we want to highlight the effects that soy can have on reproductive endpoints, which are very sensitive to soy, including uterine physiology and other estrogen-sensitive endpoints.

We assessed several animal welfare parameters, including basic health parameters (for example, locomotion, body weight), the ability to perform natural behaviors (for example, nesting), and measures of affective state (for example anxiety or despair), to investigate the effect of soy consumption on the animals’ wellbeing. All mice were well nourished and showed a typical gain in body weight when compared with previous data from our own lab. Soy-fed mice weighed significantly more from week 12 onward, although isoflavones are suggested to have beneficial effects on obesity.21,38 Several studies suggest an increase of locomotor activity as the cause for the often-observed reduced body weight in animals supplemented with soy isoflavones.21 Yet, similar to a previous study,4 we did not detect differences in locomotor activity in the open field test, possibly because we used a similar testing duration and setup size as previously.4 Perhaps a longer time window would have revealed further differences.30,39 We did not monitor the food intake in the current study, and the greater body weight of mice that received the standard diet might be due to increased energy intake. Even though our results are not definitive in this regard, we want to emphasize that estrogenic diets, like endogenous estrogens, might help with weight control in laboratory animals. This propensity might also be an interesting perspective for manufacturers, who might want to develop diets that are less prone to induce weight gain.

Housing is a much-discussed topic in the field of animal welfare, because both individual and group housing can have sex-dependent effects on stress levels and behavior. In particular, as a part of the behavioral repertoire of mice, nest building is a parameter that is very sensitive to stress effects.16 It is, therefore, a useful tool for investigating wellbeing and a naturalistic behavior.8,16 Given that we noted no difference in nest building between male and female mice, the chosen form of housing (individual) did not appear to influence this stress-sensitive parameter. Likewise, the type of diet did not affect this behavioral pattern.

Previous studies on affective behavior and isoflavones indicated both anxiolytic and anxiogenic effects in rats21,23 and mice.11,41 We did not detect alterations in anxiety-related approach–avoidance tests related to soy consumption in C57BL/6 mice. However, mice consuming the soy-free diet showed less despair behavior in the forced swim test than those fed the standard chow. Whether this effect is antidepressant or, conversely, whether feeding soy induces depressive-like behavior is a matter of perspective, especially given that earlier studies showed the antidepressant effects of a powdered soy supplement and the soy isoflavone genistein.17 Nevertheless, apparently the affective state of the mice did not suffer due to the soy-free diet and, therefore, none of the mentioned welfare domains deteriorated due to omitting soy from the diet.

The importance of awareness of possible influences of dietary soy can be illustrated by findings on cognitive performance. Previous work has shown increased cognitive performance due to isoflavone supplementation, mostly in female rats (for review, see reference 20). Some evidence suggests that dietary soy isoflavones influence sexually dimorphic cognitive behavior.24 In particular, when their food contained phytoestrogens, female rats performed better than males in tasks requiring reference and not working memory in the radial arm maze.24 In contrast, males given the same treatment demonstrated impaired visual spatial memory, which could be rescued by switching to a phytoestrogen-free diet. The authors propose an advantageous outcome of increased mobility in females but a disruptive effect in males.24 Our results support this finding, given that the highly significant sex-associated difference we detected in the contextual learning phase of the fear conditioning paradigm was further amplified when the mice received soy-free chow. These findings clearly emphasize the importance of including both sexes in experiments, as characteristic of sound scientific practice, and the potential for interaction effects.6 Although we found some sex-specific differences regarding locomotor and cognitive performance in C57BL/6 mice, we did not find significant differences between the treatment groups, apart from the earlier-mentioned results from the fear conditioning test. Social memory, object recognition, and executive functioning in the puzzle box appeared to be unaffected by soy avoidance. This outcome contradicts the findings of another group,12 who observed sexually dimorphic social behavior that was influenced by soy diet. This discrepancy in results may reflect the fact that this previous study was performed in rats, which have different social behavior than mice.

Another relevant aspect that is affected by the dietary soy content is effects on the rodent reproductive tract.7,14 An in-depth analysis of this aspect was beyond the scope of our study, yet litters did not differ in number, size, or sex distribution and therefore gave no indication of a soy-associated effect at this level. But this measure, like all of the other behavioral parameters that we investigated, might be influenced by timing, duration, and isoflavone concentration.11 The influence of general living conditions of animals—for example, type of bedding, nesting material, or food—are often overlooked by experimenters, even though these factors comprise the direct environment of their subjects. For example, the transition from vendor to laboratory most likely will coincide with a switch in food. The effects that can be triggered by such changes are unknown. Being attentive to the animals’ environment might yield insight into possible inconsistencies.

With regard to the 3Rs (replacement, refinement, and reduction), we cannot conclude from our results that removing soy from lab animals’ diet will result in a refinement for comparable experiments. Even though the assessed parameters are highly relevant, given that they cover a broad scope of behavior, they may not have been particularly sensitive to exogenous estrogens. In addition, this dietary manipulation does not cause an apparent gain in welfare, given that neither of the highly standardized diets applied sufficiently mimics the animals’ feeding behavior in nature.

The use of nonstandardized open-formula diets with natural ingredients is not recommended in general. The committee for nutrition of the German Society for Laboratory Animal Science mentions uncontrolled nutrient uptake, the possible influence of microbiologic status, a source of pathogens, or unwanted associated substances with undetected interaction in experiments and inaccurate interpretation of results.18 This concern can include soy-derived isoflavones. The removal of this confounding factor therefore might refine the quality of in vivo studies and decrease variability in resulting data, improve reproducibility, and achieve a desirable reduction in experiments involving animals. Optimizing experimental conditions is one way to ensure quality and to gain sustainability. Another action that can increase reproducibility across labs rather effortlessly is to describe the diet used in experiments when preparing publications, as advised by the ARRIVE guidelines.

Our systematic investigation of behavioral changes due to soy-free or standard diet can serve as a basis for discussion and evidenced-based decision making. Generally, avoiding fluctuations of undesired, added substances in the food of laboratory rodents can reduce environmental influences and minimize variability, thus ultimately maximizing reproducibility.

Supplementary Materials

Nutrient content of diets.

Limits of quantification (nM) for daidzein, genistein, and their corresponding phase II metabolites and for equol, equol-7-glucuronide, and equol-4’-sulfate in mouse serum samples measured by LC–MS.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR 2591, GZ: GA427/12-1). We thank Lisa Baumann for her support in the acquisition of data during behavioral experiments Bettina Schindler for excellent technical support regarding the isoflavone analyses.

References

- 1.Ben Abdallah NM, Fuss J, Trusel M, Galsworthy MJ, Bobsin K, Colacicco G, Deacon RM, Riva MA, Kellendonk C, Sprengel R, Lipp HP, Gass P. 2011. The puzzle box as a simple and efficient behavioral test for exploring impairments of general cognition and executive functions in mouse models of schizophrenia. Exp Neurol 227:42–52. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkel S, Tang W, Treviño M, Vogt M, Obenhaus HA, Gass P, Scherer SW, Sprengel R, Schratt G, Rappold GA. 2012. Inherited and de novo SHANK2 variants associated with autism spectrum disorder impair neuronal morphogenesis and physiology. Hum Mol Genet 21:344–357. 10.1093/hmg/ddr470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevins RA, Besheer J. 2006. Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial nonmatching-to-sample learning task to study ‘recognition memory.’ Nat Protoc 1:1306–1311. 10.1038/nprot.2006.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cederroth CR, Vinciguerra M, Kühne F, Madani R, Doerge DR, Visser TJ, Foti M, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Vassalli JD, Nef S. 2007. A phytoestrogen-rich diet increases energy expenditure and decreases adiposity in mice. Environ Health Perspect 115:1467–1473. 10.1289/ehp.10413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chourbaji S, Zacher C, Sanchis-Segura C, Spanagel R, Gass P. 2005. Social and structural housing conditions influence the development of a depressive-like phenotype in the learned helplessness paradigm in male mice. Behav Brain Res 164:100–106. 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clayton JA, Collins FS. 2014. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature 509:282–283. 10.1038/509282a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cline JM, Franke AA, Register TC, Golden DL, Adams MR. 2004. Effects of dietary isoflavone aglycones on the reproductive tract of male and female mice. Toxicol Pathol 32:91–99. 10.1080/01926230490265902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deacon RM. 2006. Assessing nest building in mice. Nat Protoc 1:1117–1119. 10.1038/nprot.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Degen GH, Janning P, Diel P, Bolt HM. 2002. Estrogenic isoflavones in rodent diets. Toxicol Lett 128:145–157. 10.1016/S0378-4274(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon RA. 2004. Phytoestrogens. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55:225–261. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartley DE, Edwards JE, Spiller CE, Alom N, Tucci S, Seth P, Forsling ML, File SE. 2003. The soya isoflavone content of rat diet can increase anxiety and stress hormone release in the male rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 167:46–53. 10.1007/s00213-002-1369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hicks KD, Sullivan AW, Cao J, Sluzas E, Rebuli M, Patisaul HB. 2016. Interaction of bisphenol A (BPA) and soy phytoestrogens on sexually dimorphic sociosexual behaviors in male and female rats. Horm Behav 84:121–126. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inta D, Vogt MA, Lima-Ojeda JM, Pfeiffer N, Schneider M, Gass P. 2011. Lack of long-term behavioral alterations after early postnatal treatment with tropisetron: implications for developmental psychobiology. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 99:35–41. 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jefferson WN, Doerge D, Padilla-Banks E, Woodling KA, Kissling GE, Newbold R. 2009. Oral exposure to genistin, the glycosylated form of genistein, during neonatal life adversely affects the female reproductive system. Environ Health Perspect 117:1883–1889. 10.1289/ehp.0900923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen MN, Ritskes-Hoitinga M. 2007. How isoflavone levels in common rodent diets can interfere with the value of animal models and with experimental results. Lab Anim 41:1–18. 10.1258/002367707779399428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jirkof P. 2014. Burrowing and nest building behavior as indicators of wellbeing in mice. J Neurosci Methods 234:139–146. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kageyama A, Sakakibara H, Zhou W, Yoshioka M, Ohsumi M, Shimoi K, Yokogoshi H. 2010. Genistein-regulated serotonergic activity in the hippocampus of ovariectomized rats under forced swimming stress. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74:2005–2010. 10.1271/bbb.100238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluge R, Madry M. [Internet]. 2012. Stellungnahme aus dem Ausschuss für Ernährung zum Einsatz von nicht standardisierten Futtermitteln bei Versuchstieren. [Cited 13 August 2019]. Available at: http://www.gv-solas.de/fileadmin/user_upload/pdf_stellungnahme/Stellungn_nicht_stand_fm.pdf. [In German].

- 19.Kurrat A, Blei T, Kluxen FM, Mueller DR, Piechotta M, Soukup ST, Kulling SE, Diel P. 2015. Lifelong exposure to dietary isoflavones reduces risk of obesity in ovariectomized Wistar rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 59:2407–2418. 10.1002/mnfr.201500240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YB, Lee HJ, Sohn HS. 2005. Soy isoflavones and cognitive function. J Nutr Biochem 16:641–649. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lephart ED, Setchell KD, Handa RJ, Lund TD. 2004. Behavioral effects of endocrine-disrupting substances: phytoestrogens. ILAR J 45:443–454. 10.1093/ilar.45.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima-Ojeda JM, Vogt MA, Pfeiffer N, Dormann C, Kohr G, Sprengel R, Gass P, Inta D. 2013. Pharmacologic blockade of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors induces antidepressant-like effects lacking psychotomimetic action and neurotoxicity in the perinatal and adult rodent brain. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr 45:28–33. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund TD, Lephart ED. 2001. Dietary soy phytoestrogens produce anxiolytic effects in the elevated plus maze. Brain Res 913:180–184. 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02793-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund TD, West TW, Tian LY, Bu LH, Simmons DL, Setchell KD, Adlercreutz H, Lephart ED. 2001. Visual spatial memory is enhanced in female rats (but inhibited in males) by dietary soy phytoestrogens. BMC Neurosci 2:1–13. 10.1186/1471-2202-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molteni A, Brizio-Molteni L, Persky V. 1995. In vitro hormonal effects of soybean isoflavones. J Nutr 125:751S–756S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molzberger AF, Soukup ST, Kulling SE, Diel P. 2013. Proliferative and estrogenic sensitivity of the mammary gland are modulated by isoflavones during distinct periods of adolescence. Arch Toxicol 87:1129–1140. 10.1007/s00204-012-1009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller DR, Soukup ST, Kurrat A, Liu X, Schmicke M, Xie MY, Kulling SE, Diel P. 2016. Neonatal isoflavone exposure interferes with the reproductive system of female Wistar rats. Toxicol Lett 262:39–48. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai M, Cook L, Pyter LM, Black M, Sibona J, Turner RT, Jeffery EH, Bahr JM. 2005. Dietary soy protein and isoflavones have no significant effect on bone and a potentially negative effect on the uterus of sexually mature intact Sprague–Dawley female rats. Menopause 12:291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odum J, Tinwell H, Jones K, Van Miller JP, Joiner RL, Tobin G, Kawasaki H, Deghenghi R, Ashby J. 2001. Effect of rodent diets on the sexual development of the rat. Toxicol Sci 61:115–127. 10.1093/toxsci/61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ossenkopp KP, Kavaliers M. 1996. Measuring spontaneous locomotor activity in small mammals. p 33–59. In: Ossenkopp KP, Kavaliers M, Sanberg PR, editors. Measuring movement and locomotion: from invertebrates to humans, Austin (TX): RG Landes. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ota A, Yamamoto A, Kimura S, Mori Y, Mizushige T, Nagashima Y, Sato M, Suzuki H, Odagiri S, Yamada D, Sekiguchi M, Wada K, Kanamoto R, Ohinata K. 2017. Rational identification of a novel soy-derived anxiolytic-like undecapeptide acting via gut–brain axis after oral administration. Neurochem Int 105:51–57. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richter SH, Garner JP, Zipser B, Lewejohann L, Sachser N, Touma C, Schindler B, Chourbaji S, Brandwein C, Gass P, van Stipdonk N, van der Harst J, Spruijt B, Voikar V, Wolfer DP, Würbel H. 2011. Effect of population heterogenization on the reproducibility of mouse behavior: a multi-laboratory study. PLoS One 6:e16461 10.1371/journal.pone.0016461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz H, Sontag G, Plumb J. 2009. Inventory of phytoestrogen databases. Food Chem 113:736–747. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soukup ST, Al-Maharik N, Botting N, Kulling SE. 2014. Quantification of soy isoflavones and their conjugative metabolites in plasma and urine: an automated and validated UHPLC–MS-MS method for use in large-scale studies. Anal Bioanal Chem 406:6007–6020. 10.1007/s00216-014-8034-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soukup ST, Helppi J, Muller DR, Zierau O, Watzl B, Vollmer G, Diel P, Bub A, Kulling SE. 2016. Phase II metabolism of the soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein in humans, rats, and mice: a cross-species and -sex comparison. Arch Toxicol 90:1335–1347. 10.1007/s00204-016-1663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soukup ST, Helppi J, Muller DR, Zierau O, Watzl B, Vollmer G, Diel P, Bub A, Kulling SE. 2016. Erratum to: Phase II metabolism of the soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein in humans, rats, and mice—a cross-species and -sex comparison. Arch Toxicol 90:1349 10.1007/s00204-016-1718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thigpen JE, Setchell KD, Saunders HE, Haseman JK, Grant MG, Forsythe DB. 2004. Selecting the appropriate rodent diet for endocrine disruptor research and testing studies. ILAR J 45:401–416. 10.1093/ilar.45.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velasquez MT, Bhathena SJ. 2007. Role of dietary soy protein in obesity. Int J Med Sci 4:72–82. 10.7150/ijms.4.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh RN, Cummins RA. 1976. The open-field test: a critical review. Psychol Bull 83:482–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao Y, Mao X, Yu B, He J, Yu J, Zheng P, Huang Z, Chen D. 2015. Potential risk of isoflavones: toxicological study of daidzein supplementation in piglets. J Agric Food Chem 63:4228–4235. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu C, Tai F, Zeng S, Zhang X. 2013. Effects of perinatal daidzein exposure on subsequent behavior and central estrogen receptor α expression in the adult male mouse. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 43:157–167. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng W, Hengevoss J, Soukup ST, Kulling SE, Xie M, Diel P. 2017. An isoflavone enriched diet increases skeletal muscle adaptation in response to physical activity in ovariectomized rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 61:1600843 10.1002/mnfr.201600843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zueger M, Urani A, Chourbaji S, Zacher C, Roche M, Harkin A, Gass P. 2005. Olfactory bulbectomy in mice induces alterations in exploratory behavior. Neurosci Lett 374:142–146. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Nutrient content of diets.

Limits of quantification (nM) for daidzein, genistein, and their corresponding phase II metabolites and for equol, equol-7-glucuronide, and equol-4’-sulfate in mouse serum samples measured by LC–MS.