Abstract

We employ data from the Adolescent Health and Development in Context Study – a representative sample of urban youth ages 11-17 in and around the Columbus, OH area – to investigate the feasibility and validity of smartphone-based GEMA (geographically-explicit ecological momentary assessment). Age, race, household income, familiarity with smartphones, and self-control were associated with missing GPS coverage, while school day was associated with discordance between percent of time at home based on GPS-only vs. recall-aided space-time budget. Fatigue from protocol compliance increases missing GPS across the week, which results in more discordance. Although some systematic differences were observed, these findings offer evidence that smartphone-based GEMA is a viable method for the collection of activity space data on urban youth.

Background

Residential neighborhood effects have long been a focus of research on adolescent development (Browning, Cagney, & Boettner, 2016; Leventhal, Dupéré, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Much of the theoretical motivation for studying these effects posits that individuals are exposed to causally relevant conditions in the social environment, yet most approaches use only residential context – typically census units such as tracts or block groups – to capture these exposures. This approach ignores variation in daily exposures among youth who reside within the same neighborhood. In response to this concern, a move towards the concept of activity spaces has emerged, which defines the relevant exposure space as including places individuals go in the course of routine activities and the people they encounter in those spaces (Graif, Gladfelter, & Matthews, 2014; Jones & Pebley, 2014; Kwan, 2013; Noah, 2015; Sharp, Denney, & Kimbro, 2015; Sugie & Lens, 2017). In this view, collecting spatio-temporal data on individuals’ activity patterns provides an opportunity to test theories about contextual effects on adolescent outcomes with substantially enhanced validity, incorporating both neighborhood and potentially significant extra-neighborhood exposures (Browning & Soller, 2014; Kestens, Wasfi, Naud, & Chaix, 2017; Matthews & Yang, 2013).

Recently, geographically–explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA), combining global positioning systems [GPS] technology in modern smartphones with ecological momentary assessment (EMA), has emerged as a comprehensive data collection tool for capturing social contexts and activity space exposures in real time (Freisthler, Lipperman-Kreda, Bersamin, & Gruenewald, 2015; Kirchner & Shiffman, 2016; Sugie, 2016). Continuous or near-continuous collection of spatial mobility data overcomes issues related to capturing only residential location or, within an EMA framework, a single GPS point attached to an EMA response. The latter may result in missing information when EMA reports are not completed or if the outcome of interest–such as risky behavior–drives rates of EMA completion in a given moment (Kirchner & Shiffman, 2016; Wen, Schneider, Stone, & Spruijt-Metz, 2017). Advances in mobile technology have also increased the accuracy and reduced the cost and burden of collecting spatial data via mobile phones, allowing GPS and EMA data to be collected in a single device (Palmer et al., 2013; Raento, Oulasvirta, & Eagle, 2009). A number of studies have capitalized on the GEMA approach, yielding an important body of emerging findings on the impact of activity spaces on a range of outcomes (Byrnes et al., 2017; Epstein et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2014; Sugie, 2016; York Cornwell & Cagney, 2017).

Although there are clear advantages of the GEMA approach, concerns remain about the validity of the GPS data collected through this methodology (Raento et al., 2009; Shen & Stopher, 2014; Zandbergen, 2009). Despite improvements in the accuracy of GPS, location estimates yielded by smartphone devices remain inexact. Mennis et al. (2017) report that only 69% of the GPS points collected in their GEMA design are located within the home residential census tract when the individual reports being at home during an EMA response. Although mismatched GPS and EMA-reported locations could result from the respondent mis-reporting their location in the EMA, GPS device imprecision is also likely to contribute to error in location estimates.

Beyond the accuracy of the GPS data collection technology, factors associated with study compliance may affect the quality of smartphone-based data. Broadly, differences in social circumstances across youth may independently contribute to the capacity to adhere to study requirements. Despite their willingness and capacity to follow the study protocol, youth in socioeconomically disadvantaged families or residential neighborhoods may face a number of challenges, constraints, and daily stressors that limit their ability to consistently carry and manage project-provided phones by comparison with more advantaged youth.

The validity of the data derived from GPS or GEMA methods may also be threatened by other subject-level factors (some of which may be related to disadvantaged family and neighborhood circumstances). Bias may be introduced due to lack of familiarity with technology, conscientiousness with respect to data collection procedures, and potentially purposive efforts to conceal location. Familiarity with technology may be a particularly important source of error when collecting GPS data (Bricka, Sen, Paleti, & Bhat, 2012). GEMA data collection projects often involve providing subjects with phones if they don’t already have access to one or if the study design requires device consistency across subjects or significant preprogramming. Older adolescents and those from families with higher household income are more likely to have smartphones already, and may be more easily able to adapt to carrying a second study phone and use the phone to complete GEMA prompts. In contrast, however, already having a phone may make the respondent less likely to carry a second phone, resulting in reduced GPS validity if, for example, the phone is left at home while the subject spends time outside of the home.

The subject’s conscientiousness with respect to the study protocol may also result in reduced data validity above and beyond familiarity with technology. Adolescent respondents must keep track of the phone, charge it nightly, and remember to bring the phone with them. Differences in levels of self-regulation across adolescents may contribute to variation in compliance with study requirements, resulting in systematic differences in GPS coverage and validity (for discussion of EMA compliance rates across individual traits, see Sokolovsky, Mermelstein, & Hedeker, 2014; Wen et al., 2017).

An additional subject-level factor potentially affecting validity is confidentiality and privacy concerns. Some subjects may purposefully shut the phone off, modify GPS data collection settings, or leave the phone at home in order to conceal sensitive locations associated, e.g., with risk behaviors (Mitchell et al., 2014; Rudolph, Bazzi, & Fish, 2016). Prior studies have noted discomfort with being tracked, especially among high-risk populations such as drug users (Rudolph et al., 2016). Among adolescent females in a small community-based pilot study, Wiehe et al. (2008) reported an overall positive sentiment about GPS tracking; respondents cited increased feelings of safety while being tracked. However, it’s unclear the extent to which discomfort with data collection would induce respondents to purposively turn off the GPS tracking on the study phone. Rudolph et al. (2017) recommended obtaining a National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality as one way of reducing participant concerns; having a Certificate increased feelings of trust and honesty about activity locations among urban substance-using respondents.

One method of dealing with potential GPS issues or loss of coverage, developed by transportation and urban planning research, is to conduct a prompted recall interview with respondents after the GPS data collection ends. This approach allows the subject to review GPS tracks, confirm activity locations and trips, provide contextual information, and update inaccurate or erroneous data (Auld & Mohammadian, 2014; Greaves, Fifer, Ellison, & Germanos, 2010; Shen & Stopher, 2014). Comparisons of the GPS-only and prompted recall GPS designs find improved trip accuracy with prompted recall (Auld, Williams, Mohammadian, & Nelson, 2009; Giaimo, Anderson, Wargelin, & Stopher, 2010; Safi, Assemi, Mesbah, & Ferreira, 2017; Shareck, Kestens, & Gauvin, 2013). Prompted-recall designs have been used most frequently in travel and transportation surveys, which typically lack measures of attitudes, behaviors, and health that are key outcomes for social science and health researchers. As a result, these methods have been underutilized in research on adolescent development.

The addition of spatial data to survey-based EMA methods in the GEMA framework expanded the scope of traditional designs to allow for real-time assessments of activity spaces and situational contexts. Yet prior studies using GEMA have been limited by small, unrepresentative samples, and have mostly focused on substance use or physical activity (Byrnes et al., 2017; Dunton, Kawabata, Intille, Wolch, & Pentz, 2012; Epstein et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2016). No studies to our knowledge combine GPS, EMA, and prompted recall interviews with traditional social science surveys to provide a comprehensive collection of activity space exposures, individual and family characteristics, behaviors, and health. The Adolescent Health and Development in Context (AHDC) study is designed to overcome limitations of previous GEMA research. In addition to a large (N=1405), diverse, and representative sample of an urban area, AHDC combines GEMA with a recall-aided interactive space-time budget to increase the accuracy of locational data.

Drawing on both GEMA and space-time budget data from the AHDC, we assess two measures of GEMA data quality. First, we consider the question of GPS coverage – the extent to which AHDC was able to collect GPS data consistently across days of the weeklong study period for a large scale and representative adolescent sample. In this analysis, we model the extent of daily GPS coverage using the number of minutes of missing GPS coverage per day as the outcome. Second, we assess data validity by comparing GPS data collected during the GEMA week to the space-time budget data generated from the prompted recall interview. Specifically, we model instances of discordance between the GPS and respondent-adjusted space-time budget data, i.e., when the GPS data indicate that the youth spent all or most of the day at home but the space-time budget has been adjusted to reflect more time outside the home. This measure captures instances of the youth leaving the phone at home all day, resulting in inaccurate representation of actual exposures in the GPS-collected data.

For both outcomes, we investigate systematic differences along individual, family, and traditional neighborhood characteristics to understand potential variation in data quality across people and places. We test the hypothesis that disadvantaged family and neighborhood circumstances reduce GPS coverage and validity. We also consider the expectation that older youth and those who already have a personal phone will have better GPS coverage because they are more familiar with smartphones and less likely to have disruptions in data collection arising from battery depletion or accidentally turning off location services. Adolescents who already have a phone, however, may be most at risk for discordance, if they are more likely to leave the project phone at home (and later update their location for that time period in the prompted recall interview). We also consider the extent to which measures of self-control (conscientiousness) and prior delinquency (capturing possible motivation to purposefully conceal location) influence study compliance outcomes. Finally, we assess whether aspects of the study design affect GPS coverage and discordance through participant fatigue.

Methods

Data

The Adolescent Health and Development in Context (AHDC) study is a representative, longitudinal study of 1,405 adolescents in Franklin County, Ohio. The sampling frame was based on a combination of a vendor-provided list of households with high probability of meeting eligibility criteria (youth age 11 to 17 in the household) and data from public school districts represented in the study area. Sampled households were mailed a letter or postcard describing the study, followed by interviewer calls to the household to solicit participation in the study. Among contacted, eligible households, one randomly selected youth aged 11-17 and one primary caregiver (English speaking) were recruited to participate in the study. The AAPOR Cooperation Rate 1–the number of completed interviews out of eligible contacted households– is 88%. The response rate for the sample is 21.3% (AAPOR Response Rate 3).1

The study area is a contiguous space within the outerbelt of Interstate 270, encompassing a majority of the city of Columbus as well as a number of suburban municipalities. The final sample is representative of the population in the study area with respect to household income of families with children and racial composition, with the exception that the percent of recruited adolescents that are African-American is elevated compared to the estimated population of adolescents living in the study area (see Results for a comparison). The study design and procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the authors’ university before fieldwork began. Written parental permission and youth assent to participate in the study was obtained by interviewers prior to the beginning of the initial in-home interview. We obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health, which can be used to protect the research team from being subpoenaed for participant research data. The consent forms include information on the GPS tracking, the Certificate of Confidentiality, and assurances that data will be kept confidential, including not sharing child responses with police or their caregivers. Participants are also given the option to refuse to answer any survey-based questions about locations and behaviors or give approximate locations such as an intersection.

The basic design of the adolescent and caregiver data collection proceeds over a weeklong period as follows: at the first in-home visit, an Entrance Survey with a focal youth and his/her caregiver covers a range of topics including demographic and socioeconomic background, household and family environment, health, substance use, and adolescent risk behaviors. Both caregivers and adolescents report on routine locations visited during a typical week. The caregiver face-to-face interviewer is conducted while the youth is taking the self-administered modules of the survey that includes sensitive topics; the caregiver then completes the self-administered survey while the youth completes the face-to-face interview with the interviewer. Interviewers are instructed to separate the caregiver and youth as much as possible to maintain privacy.

A seven day smartphone-based GEMA data collection period follows the Entrance Survey. This novel feature of the AHDC design allows for collection of real-time data on locations, activities, network partner presence and interactions, mood, and risk behavior with continuous GPS monitoring. Participants received a Motorola Droid Razr M running the Android 4.4.2 (Kit Kat) operating system for use during the study period. The study application on the phone provides a user interface which houses the link to the web-based survey when it is time to complete an EMA. The app also executes the passive GPS data collection, using custom written software designed for the AHDC project to integrate the GPS data collection into the EMA application. Finally, Exit Surveys are administered to both the caregiver and youth at the end of the week and an interactive space-time budget (Anderson, 1971) (described below) is completed by the youth.

The smartphone-based GPS data collection prioritizes spatial data from GPS satellites for precision and accuracy, and saves location data collected from the Android SDK [software development kit] every 30 seconds when connected. If no GPS satellite position has been saved in the last 10 minutes, location coordinates based on cell tower network position are collected every 60 seconds. Although we specifically chose a phone with a larger battery, and designed the GPS collection to be as battery-efficient as possible, smartphone-based GPS data collection is still a battery-intensive process. We collect battery level of the phone to assess missing GPS time periods due to low battery. The GPS data are uploaded to secure servers every hour. We also added a prompt to remind the study participant to turn on the location services if they were turned off during the GEMA week.

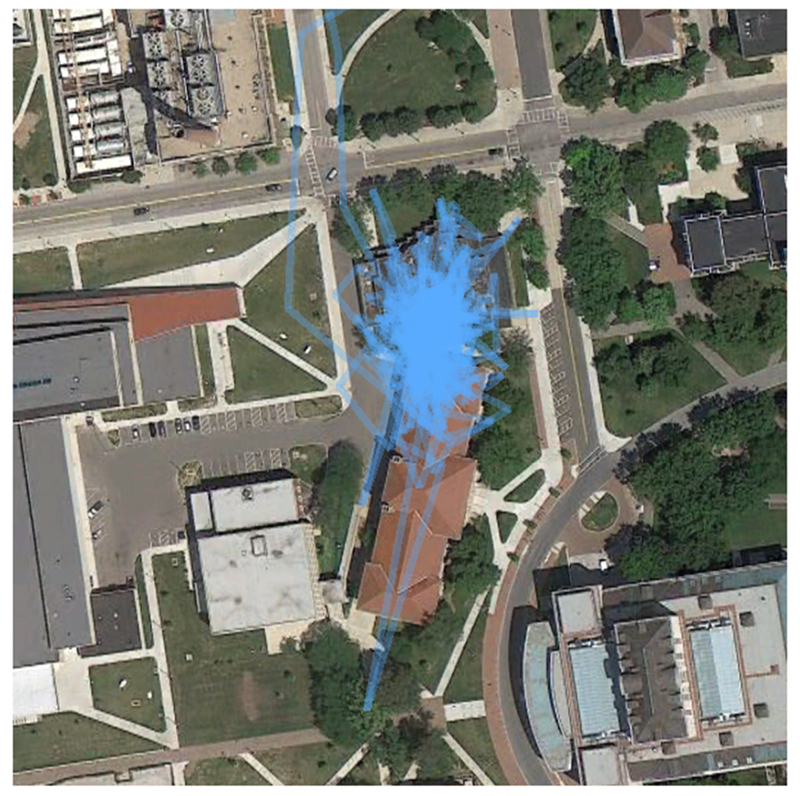

Figure 1 presents test data collected by an AHDC staff member during the development of the data collection methods, for a typical work day.2 Although the majority of the day was spent in one office in the northwest corner of the building shown in the center of the picture, the GPS points from those 7.5 hours bounce around considerably. The basement office location in a 120 year old building may in part explain the difficulty in getting a precise location due to low visibility of satellites (to triangulate position). Visually, the centroid of the collection of points appears to be in between two buildings, rather than actually within either of the adjoining buildings. Other types of buildings observed in the AHDC respondents GPS tracks that also exhibit poor connectivity may include apartment buildings, large box stores and malls, or large school buildings. The space-time budget is designed in part to deal with these potential issues of connectivity and poor visibility of GPS satellites.

Figure 1:

GPS tracks of pilot data from an AHDC staff member

Space-Time Budget Data Collection

In order to deal with potential noise or inaccuracy of GPS-only data collection, we developed an interactive space-time budget (Anderson, 1971) which is administered during a follow-up in-person interview of the youth at the end of the GEMA week. In addition, the follow up collects detailed activity data on five of the GEMA days – the three most recent weekdays and two weekend days. The follow-up interview includes questions that mirror the GEMA survey items in order to capture information about activities, locations, and experiences for time periods that were not covered by GEMA prompts.

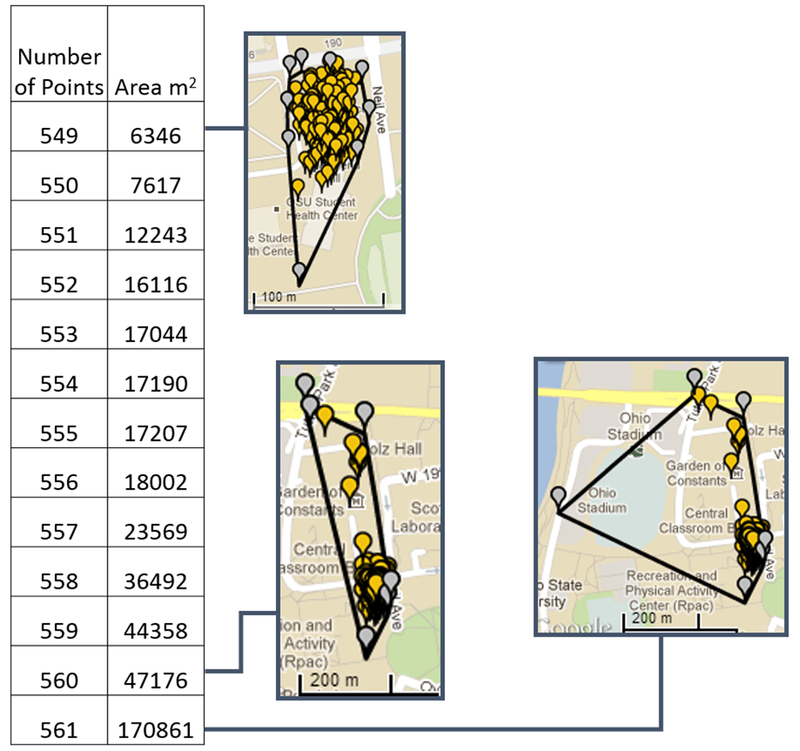

The space-time budget processes GPS data to summarize stationary and travel periods. This process cleans up noise in the GPS measurements that is present even during stationary periods and provides coordinates of stable locations for analysis. These stationary periods are determined by applying a convex hull detection algorithm to the raw GPS data. Convex hull methods have been used recently in several community detection and activity space projects (Chan, Helfrich, Hursh, Sally Rogers, & Gopal, 2014; Yin et al., 2013). This algorithm iteratively creates a minimum bounding polygon, or the smallest convex subset of the real plane containing the set of coordinates. We begin by observing the first four points at the beginning of each day. Due to the volatility of the convex hull with only a few points, we only begin testing checking for movement when the convex hull polygon around a set of points reaches a minimum of 300 meters squared. Once the minimum area has been achieved, we begin checking for increases in area of 100% with the additional of a single GPS point. If the area does not increase by more than 100%, the point is added to the definition of the stationary period, and the new area is taken as the baseline. This continues until the next observed GPS coordinate pairs increase the area of the convex hull by 100 percent, at which point the algorithm infers that the respondent has left the previous stable activity location and has begun a travel period. Following an established mobile period, the algorithm checks for decreasing speed below 2 kilometers per hour averaged across the previous 5 points in order to signal the end of a travel period and the beginning of a stationary period, at which point the above process begins again. Figure 2 shows an example of the convex hull algorithm on the set of points shown in Figure 1. In the top left picture, the minimum area has been achieved to begin processing a stationary period. As points are added, the area increases. By the bottom right picture [scale zoomed out for clarity], the area has increased by 100%, triggering a travel period has begun and the stationary period has ended. This stationary location included 561 points over the course of 8 and a half hours.

Figure 2:

Convex Hull algorithm processing

Note: The table on the left indicates the number of points in the convex hull calculation, and the increase in area by the addition of the last point. The pictures depict the addition of points in time from the upper left to the lower right. Gray points indicate the vertices/bounding points of the convex hull; yellow markers indicate GPS points falling within the convex hull. As points are added to the grouping, the area of the convex hull increases. The convex hull increases by 100% with the addition of a single point, marking the end of the stationary period and the beginning of a travel period at the last added point.

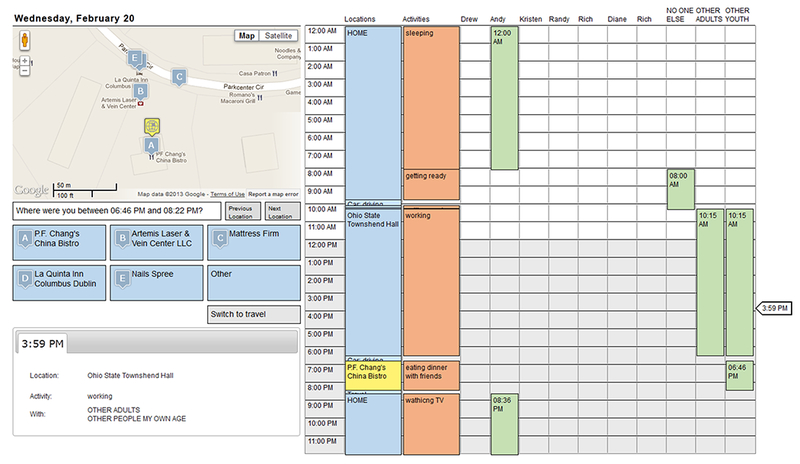

The space-time budget application combines the stable locations identified by processing the raw GPS measurements and displays these locations with labels from nearby routine location self-reports obtained at the Entrance Survey and the Google Places API (see the blue boxes labeled A-E on the left side in Figure 3). Using this information, the algorithm is designed to infer the labels of stable locations. These inferences, combined with EMA responses and maps of travel paths, serve as recall aids. As the interviewer proceeds through each day, the youth confirms their location at an inferred place, or enters a new location. The youth (guided by the interviewer) also reports type of activity and presence of network partners throughout the day. Figure 3 is a screenshot from the space-time budget application, again using pilot data from an AHDC staff member, who visited a P.F. Chang’s restaurant. The restaurant was not a routine location but was correctly inferred by the application (shown in Box A). The arrow on the right indicates an EMA survey was returned at approximately 3:30pm; the data from the EMA responses can aid in populating the activity and network partner reports in the right two columns of the space/time budget. The activity reports do not ask about risk behaviors during the space-time budget process to avoid potential respondent discomfort about discussing locations and risk behaviors aloud during the in-home visit.

Figure 3:

Screenshot from the space-time budget application using pilot data

The data sources that will be considered offer, in combination, far more precise information on routine activity patterns than is currently available from other large scale social survey data resources on adolescent health and development.

Measures

Dependent Variables: GPS Coverage & Discordance

The combined file of all saved GPS coordinates from Wave 1 cases with any GPS data during the GEMA week (N=1,379 respondents) includes 16.9 million points.3 The median interval between saved coordinates is approximately 30 seconds. Over 99% of all coordinates have a gap of less than 2 minutes since the previously saved coordinates. To measure interruptions in spatial coverage across each day of the GEMA week, we identify gaps between coordinates as missing if the total duration between then is 20 minutes or more. This duration was chosen to set a conservative cutoff of what is calculated as missing, to identify periods of time where inferring location and exposures between points may be compromised (however, to the extent that a 20 minute – or larger – gap is considered tolerable for a specific research purpose, our approach would result in an underestimate of coverage). The 20 minute cutoff identifies 8,920 gaps (5%) as indicating missing data. Of those, 15% are due to low battery periods where the phone turned off and was not plugged in to charge immediately. The total duration of the identified missing gaps are then summed across the day to create a measure of daily total minutes missing coverage, the dependent variable for the first set of analyses. Exposure for the day, or the total minutes of possible coverage of GPS data is defined as 1,440 minutes; for the first day of the study for each respondent (day 1; the beginning of the in-scope GEMA period), exposure is defined as the duration from the beginning of the phone setup at visit 1 to the end of the day.

To assess the accuracy of the GPS coverage relative to the space-time budget, we compare summarized GPS data for a single day to matched space-time budget data for the same day. GPS coordinates are identified as “at home” if the points fall within 50 meters of the home latitude and longitude. For two sets of coordinates that are both within the home buffer and within 20 minutes of each other, we sum the duration between matching points at home across the day. The duration at home is then summarized across the day, divided by the non-missing coverage for that day (1- daily total missing minutes described above), then expressed as the percent of daily time at home. For the space-time budget data, we identify locations that are within 30 meters of the home latitude and longitude as “at home” time, and summarize the daily time spent at home as a percent of the total time captured in the space-time budget for the day. Since the location-level coordinates from the space-time budget data collection are centroids of a series of points which have been identified as a stationary location by the convex hull algorithm, we expect that they are more accurate to the exact home coordinates than any individual GPS point. Therefore, we use the smaller buffer of “at home” time for the space-time budget (30m) compared to the GPS data (50m). We then create a day-level measure of discordance which indicates when greater than 95% of the GPS time for the entire day is at home, but less than or equal to 95% of the space-time budget data for that same day is at home. We use this measure of discordance over other possibilities, such as comparing discordance in time at school, in part because leaving the phone at home when the youth spends time outside the home is expected to be one of the most common errors present in the data (although see Supplementary Analyses for the results of sensitivity tests using alternative operationalizations of discordance).

The discordance analysis is conducted with all days with non-zero GPS coverage. Although this includes some days with relatively low coverage, the mean GPS coverage for days with both GPS and space-time budget data in the discordance analysis is 90% (median 100%). In order to reduce the likelihood that including low coverage days introduces bias into the analysis, we separately ran the models presented below in Tables 3a and 3b, restricting the days to those with 90% or more GPS coverage. Results from those models are consistent with the results presented below for all eligible days.

Table 3a.

Multilevel Logistic Regression of Discordance (>95% GPS at Home, ≤95% Space-Time Budget at Home)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | SE | Odds Ratio | SE | Odds Ratio | SE | |

| School Day | 1.825*** | 0.229 | 1.827*** | 0.230 | 1.823*** | 0.229 |

| Male | 0.856 | 0.138 | 0.851 | 0.138 | 0.852 | 0.137 |

| Age 14-15 | 0.980 | 0.191 | 0.971 | 0.190 | 0.955 | 0.187 |

| Age 16-17 | 0.833 | 0.169 | 0.832 | 0.169 | 0.815 | 0.166 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.720 | 0.154 | 0.799 | 0.201 | 0.811 | 0.205 |

| Hispanic | 1.451 | 0.490 | 1.488 | 0.510 | 1.490 | 0.508 |

| Multiracial | 0.998 | 0.293 | 1.055 | 0.317 | 1.053 | 0.316 |

| Income $30,001-$60,000 | 0.803 | 0.174 | 0.762 | 0.168 | 0.757 | 0.166 |

| Income $60,001-$150,000 | 0.815 | 0.195 | 0.716 | 0.183 | 0.711 | 0.181 |

| Income >$150k | 0.939 | 0.290 | 0.778 | 0.258 | 0.792 | 0.263 |

| Caregiver cohabiting | 1.275 | 0.373 | 1.312 | 0.386 | 1.344 | 0.395 |

| Caregiver single | 1.180 | 0.308 | 1.172 | 0.307 | 1.170 | 0.306 |

| Caregiver other marital status | 1.571 | 0.369 | 1.566 | 0.369 | 1.565 | 0.368 |

| Youth has a phone | 1.368 | 0.282 | 1.302 | 0.272 | 1.265 | 0.264 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 0.829 | 0.131 | 0.830 | 0.131 | ||

| Neighborhood black population | 1.328 | 0.672 | 1.349 | 0.681 | ||

| Neighborhood residential instability | 0.936 | 0.107 | 0.929 | 0.106 | ||

| Youth Behavior and Personality | ||||||

| Delinquency, 1 report | 1.417 | 0.322 | ||||

| Delinquency, 2 reports | 0.923 | 0.285 | ||||

| Delinquency, 3 or more | 1.217 | 0.406 | ||||

| Self-control | ||||||

| Space-time budget day | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.024*** | 0.008 | 0.025*** | 0.008 | 0.025*** | 0.008 |

| Variance Component: Youth | 2.253*** | 0.356 | 2.254*** | 0.356 | 2.225*** | 0.354 |

| N (Days) | 5413 | 5413 | 5413 | |||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 3b.

Multilevel Logistic Regression of Discordance (>95% GPS at Home, ≤95% Space-Time Budget at Home)

| Model 4 | Model 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | SE | Odds Ratio | SE | |

| School Day | 1.824*** | 0.229 | 1.738*** | 0.222 |

| Male | 0.848 | 0.137 | 0.842 | 0.139 |

| Age 14-15 | 0.957 | 0.187 | 0.951 | 0.190 |

| Age 16-17 | 0.825 | 0.168 | 0.818 | 0.170 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.827 | 0.209 | 0.823 | 0.213 |

| Hispanic | 1.508 | 0.515 | 1.515 | 0.528 |

| Multiracial | 1.053 | 0.316 | 1.063 | 0.325 |

| Income $30,001-$60,000 | 0.761 | 0.167 | 0.758 | 0.170 |

| Income $60,001-$150,000 | 0.720 | 0.183 | 0.715 | 0.186 |

| Income >$150k | 0.797 | 0.264 | 0.784 | 0.266 |

| Caregiver cohabiting | 1.313 | 0.387 | 1.328 | 0.399 |

| Caregiver single | 1.151 | 0.301 | 1.172 | 0.313 |

| Caregiver other marital status | 1.566 | 0.368 | 1.600 | 0.384 |

| Youth has a phone | 1.272 | 0.265 | 1.278 | 0.273 |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 0.821 | 0.130 | 0.818 | 0.132 |

| Neighborhood black population | 1.342 | 0.678 | 1.351 | 0.696 |

| Neighborhood residential instability | 0.935 | 0.107 | 0.928 | 0.109 |

| Youth Behavior and Personality | ||||

| Delinquency, 1 report | 1.383 | 0.316 | 1.389 | 0.324 |

| Delinquency, 2 reports | 0.872 | 0.273 | 0.878 | 0.281 |

| Delinquency, 3 or more | 1.129 | 0.385 | 1.147 | 0.399 |

| Self-control | 0.877 | 0.106 | 0.873 | 0.108 |

| Space-time budget day | 1.269*** | 0.054 | ||

| Intercept | 0.025*** | 0.008 | 0.012*** | 0.004 |

| Variance Component: Youth | 2.221*** | 0.353 | 2.363*** | 0.375 |

| N (Days) | 5413 | 5413 | ||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Control Variables: Day level characteristics

A control for whether the day is a regularly scheduled school day (vs. non-school days and weekends) is included to account for possible missing that occurs if the respondent turns off the phone during school hours. The original design of the study did not treat school as in-scope time due to concerns regarding school rules on phone use and the potential for youth to be constrained in their ability manage the phone during school hours. However, the vast majority of youth kept their phones on during school hours. Consequently, we chose to include school hours in the current analysis. In the GPS coverage analysis, we also include a measure of GEMA day, the day of the GEMA study design (coded as a continuous indicator than ranges from 1 to 7), to capture potential effects of design-related fatigue in carrying the phone. In the discordance models, we include a similar measure of the space-time budget day, which is a continuous indicator of where the day falls in the sequence of collected space-time budget days (ranging from 1 to 5).

Control Variables: Individual level characteristics

We use a set of core demographic and socioeconomic variables in models predicting individual level differences in GPS coverage and discordance across the week. We include adolescent age (ranging from 11-17), whether the youth is male (female is reference category), and race/ethnicity (white is the reference category; black, Hispanic, multiracial, and Asian/other). To capture household resources, we include caregiver marital status (married is reference; cohabiting, single, and other) and household income (less than $30,000 is the reference; $30,001 to $60,000, $60,001 to $150,000, and greater than $150,000). We also control for whether the youth already has a cellphone or smartphone of their own, as a way of capturing familiarity with the routine of carrying a phone and charging it regularly.

We also include a measure of delinquency, a count of the number of behaviors as reported by the adolescent on the self-administered survey of 14 behaviors. Items include causing trouble in a public place, purposely damaging property, breaking into a building or property, stealing, and pickpocketing. We use a categorical version in the models, comparing those with 1, 2, or 3 or more items reported with those who report none as the omitted reference category. Self-control is a youth level self-reported measure, based on agreement with 9 items about ability to resist temptation, attitudes towards risk-taking, and reaction to provocation (Wikström & Svensson, 2010). Agreement is on a scale from 1 (low self-control) to 5 (high self-control), with the average taken across the nine items; the Cronbach’s alpha for the items is 0.69. The measure is centered in analyses for ease of interpretation. We propose that effects of delinquency on missing GPS coverage net of self-control would be consistent with a purposive intent to limit the GPS information provided. Effects of self-control we argue are consistent with a conscientiousness effect, where gaps in GPS coverage are due to lower capacity to comply with the demands of the data collection (as opposed to an intentional effort to circumvent logging of GPS information on the phone).

Neighborhood characteristics

We include three structural measures of residential neighborhood using 2009-2013 Census tract data from the American Community Survey to capture potential differences in GPS coverage using typical covariates in neighborhood effects research. Economic disadvantage is a standardized scale of the following four items: (1) poverty rate, (2) unemployment rate, (3) the percent of households that are female-headed, and (4) the percent of households that receive cash assistance. Residential instability is a standardized scale consisting of the percent of residents ages one and older who have moved in the past year and the percent of occupied housing units that are renter-occupied. We also include the percent of the population that is non-Hispanic black.

Analytic Strategy

In the first set of analyses, we model the number of missing minutes of GPS coverage per day. While the number of minutes missing is technically constrained to be less than the number of in-scope minutes, due to the relatively small percentage of missing time, a Poisson approximation to the binomial distribution for the outcome is appropriate. We employ multilevel negative binomial regression to account for clustering of days within participants and overdispersion of the dependent variable relative to the Poisson distributional assumptions. We include a range of individual and neighborhood characteristics to assess how key predictors of adolescent developmental outcomes (the major focus of the AHDC study) are related to coverage and therefore may introduce bias into substantive models. We start with 1,379 cases with usable GPS data during the GEMA week. We lose 135 cases in this analysis to listwise deletion on all covariates used across the models, largely due to missing household income and caregiver marital status. All models for the GPS coverage analyses include the remaining 8,703 days from 1,244 respondents once accounting for missing on covariates.

For the second set of analyses of discordance between the GPS data and the space-time budget data, we use a multilevel logistic regression predicting the log odds of the day-level GPS data being greater than 95% at home, while the space-time budget data from the same day is less than or equal to 95% at home. This analysis is limited to a subset of days from the GPS coverage analyses for which there is non-zero GPS coverage and space-time budget data is available (collected for a maximum of 5 of 7 GEMA days).4 The discordance models include 5,413 days from 1,183 respondents. We include the same set of predictors for these models as the GPS coverage analyses.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables included in the analysis. The median number of missing minutes per day is 24 minutes, which is approximately 1.7% of the possible time covered per day. The mean percentage of daily time with GPS coverage for youth is 86%. Only 7.1% of days with both GPS and space-time budget data are discordant, where at least 95% of the GPS time is at home but 95% or less of the space-time budget data is at home. The sample is diverse with respect to race and ethnicity; 48% of youth are non-Hispanic white, 36% are black, and 6% are Hispanic, closely mirroring the adolescent population in the study area, which is 49% white, 32% black, and 9% Hispanic.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Adolescent Health and Development in Context (AHDC) study variables

| Mean or Percent | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Day Level Characteristics (N=8,703) | ||

| Missing GPS time, minutes | 186.94 | 364.58 |

| Possible GPS coverage, minutes | 1295.92 | 359.39 |

| School Day | 49.4% | |

| GPS-Space Time Budget discordance (N=5,413) | 7.1% | |

| Individual and Family Characteristics (N=1,243) | ||

| Male | 47.4% | |

| Age 11-13 | 35.8% | |

| Age 14-15 | 31.8% | |

| Age 16-17 | 32.4% | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 47.8% | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 36.6% | |

| Hispanic | 5.6% | |

| Asian | 1.4% | |

| Multiracial | 8.5% | |

| Other | 0.2% | |

| Household Income ≤$30,000 | 35.2% | |

| Income $30,001-$60,000 | 24.5% | |

| Income $60,001-$150,000 | 28.4% | |

| Income >150k | 11.9% | |

| Caregiver married | 54.9% | |

| Caregiver cohabiting | 9.7% | |

| Caregiver single | 19.4% | |

| Caregiver other marital status | 16.0% | |

| Youth has a phone | 76.2% | |

| Delinquency, None | 72.0% | |

| Delinquency, 1 report | 13.9% | |

| Delinquency, 2 reports | 8.0% | |

| Delinquency, 3 or more | 6.0% | |

| Self-control | 3.35 | 0.70 |

| Neighborhood Characteristics(N=181) | ||

| Economic disadvantage | 0.28 | 0.97 |

| Non-Hispanic black population | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Residential instability | 0.59 | 0.97 |

GPS Coverage

Multilevel negative binomial models of minutes of missing GPS time for days across the GEMA week are presented in Tables 2a (Models 1-4) and 2b (Models 5-7). In Model 1, we include whether it is a school day, youth age, gender, and race. Model 2 adds family resources, household income and caregiver marital status. Model 3 adds an indicator of whether the youth already has a cellphone or not, and Model 4 adds neighborhood characteristics. In Model 5, we add a measure of delinquency; model 6 adds self-control. Model 7 adds the indicator of the GEMA day sequence.

Table 2a.

Multilevel Negative Binomial Regression of Total Daily Minutes of Missing GPS Coverage

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| School Day | 0.071 | 0.066 | 0.057 | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.067 |

| Male | 0.025 | 0.071 | 0.043 | 0.072 | 0.028 | 0.072 | 0.030 | 0.072 |

| Age 14-15 | −0.248** | 0.086 | −0.240** | 0.086 | −0.201* | 0.087 | −0.198* | 0.087 |

| Age 16-17 | −0.477*** | 0.088 | −0.468*** | 0.088 | −0.387*** | 0.091 | −0.386*** | 0.091 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.484*** | 0.080 | 0.308*** | 0.093 | 0.294** | 0.094 | 0.253* | 0.111 |

| Hispanic | 0.208 | 0.159 | 0.116 | 0.161 | 0.085 | 0.162 | 0.067 | 0.165 |

| Asian | −0.554 | 0.301 | −0.513 | 0.302 | −0.460 | 0.304 | −0.456 | 0.305 |

| Multiracial | 0.150 | 0.132 | 0.033 | 0.135 | 0.015 | 0.136 | −0.007 | 0.140 |

| Other | 0.455 | 0.848 | 0.306 | 0.852 | 0.427 | 0.855 | 0.424 | 0.856 |

| Income $30,001-$60,000 | −0.075 | 0.094 | −0.029 | 0.096 | −0.012 | 0.098 | ||

| Income $60,001-$150,000 | −0.230* | 0.104 | −0.156 | 0.107 | −0.126 | 0.115 | ||

| Income >$150k | −0.425** | 0.136 | −0.345* | 0.139 | −0.307* | 0.151 | ||

| Caregiver cohabiting | 0.075 | 0.131 | 0.119 | 0.133 | 0.108 | 0.133 | ||

| Caregiver single | 0.101 | 0.112 | 0.128 | 0.113 | 0.131 | 0.114 | ||

| Caregiver other marital status | 0.156 | 0.108 | 0.179 | 0.108 | 0.179 | 0.109 | ||

| Youth has a phone | −0.326*** | 0.089 | −0.330*** | 0.090 | ||||

| Neighborhood economic disadvantage | 0.029 | 0.070 | ||||||

| Neighborhood black population | 0.080 | 0.225 | ||||||

| Neighborhood residential instability | −0.024 | 0.050 | ||||||

| Youth Behavior and Personality | ||||||||

| Delinquency, 1 report | ||||||||

| Delinquency, 2 reports | ||||||||

| Delinquency, 3 or more | ||||||||

| Self-control | ||||||||

| GEMA day | ||||||||

| Intercept | −2.130*** | 0.092 | −1.988*** | 0.121 | −1.833*** | 0.128 | −1.855*** | 0.137 |

| Ln(α) | 2.130*** | 0.019 | 2.126*** | 0.019 | 2.123*** | 0.019 | 2.122*** | 0.019 |

| Variance Component: Youth | 0.178** | 0.067 | 0.186** | 0.067 | 0.199** | 0.068 | 0.202** | 0.069 |

| N (Days) | 8703 | 8703 | 8703 | 8703 | ||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

Table 2b.

Multilevel Negative Binomial Regression of Total Daily Minutes of Missing GPS Coverage

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| School Day | 0.062 | 0.067 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.050 | 0.065 |

| Male | 0.029 | 0.073 | 0.039 | 0.072 | 0.048 | 0.068 |

| Age 14-15 | −0.212* | 0.088 | −0.219* | 0.087 | −0.211* | 0.083 |

| Age 16-17 | −0.400*** | 0.092 | −0.396*** | 0.091 | −0.377*** | 0.086 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.244* | 0.111 | 0.269* | 0.111 | 0.237* | 0.105 |

| Hispanic | 0.048 | 0.166 | 0.057 | 0.164 | 0.103 | 0.156 |

| Asian | −0.442 | 0.306 | −0.404 | 0.305 | −0.310 | 0.290 |

| Multiracial | −0.003 | 0.141 | −0.012 | 0.139 | −0.026 | 0.132 |

| Other | 0.453 | 0.859 | 0.321 | 0.858 | 0.432 | 0.817 |

| Income $30,001-$60,000 | −0.016 | 0.098 | −0.004 | 0.098 | −0.009 | 0.092 |

| Income $60,001-$150,000 | −0.110 | 0.116 | −0.111 | 0.115 | −0.097 | 0.108 |

| Income >$150k | −0.296 | 0.152 | −0.296* | 0.151 | −0.291* | 0.142 |

| Caregiver cohabiting | 0.093 | 0.134 | 0.057 | 0.133 | 0.073 | 0.126 |

| Caregiver single | 0.119 | 0.115 | 0.086 | 0.114 | 0.059 | 0.108 |

| Caregiver other marital status | 0.162 | 0.109 | 0.146 | 0.109 | 0.090 | 0.103 |

| Youth has a phone | −0.332*** | 0.090 | −0.306*** | 0.090 | −0.302*** | 0.085 |

| Neighborhood economic disadvantage | 0.024 | 0.070 | 0.018 | 0.069 | 0.016 | 0.066 |

| Neighborhood black population | 0.117 | 0.226 | 0.077 | 0.224 | 0.107 | 0.212 |

| Neighborhood residential instability | −0.018 | 0.05 | −0.009 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.047 |

| Youth Behavior and Personality | ||||||

| Delinquency, 1 report | −0.102 | 0.106 | −0.146 | 0.106 | −0.131 | 0.101 |

| Delinquency, 2 reports | 0.190 | 0.133 | 0.119 | 0.134 | 0.093 | 0.127 |

| Delinquency, 3 or more | 0.274 | 0.153 | 0.192 | 0.154 | 0.133 | 0.145 |

| Self-control | −0.171** | 0.052 | −0.147** | 0.049 | ||

| GEMA day | 0.191*** | 0.016 | ||||

| Intercept | −1.876*** | 0.14 | −1.294*** | 0.225 | −2.168*** | 0.222 |

| Ln(α) | 2.120*** | 0.019 | 2.121*** | 0.019 | 2.113*** | 0.019 |

| Variance Component: Youth | 0.210** | 0.069 | 0.193** | 0.067 | 0.099 | 0.056 |

| N (Days) | 8703 | 8703 | 8703 | |||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

In Model 1, school days are associated with more minutes of missing on average per day than non-school days, but the difference is not significant, nor is the positive effect of being male. Youth age is negatively and significantly associated with number of minutes of missing coverage across the week. Compared to respondents who were between 11 and 13 years old, 14 and 15 year olds had 22% fewer missing minutes of GPS coverage per day. Youth ages 16 and 17 had 38% fewer missing minutes per day on average, holding all other covariates constant. The coefficient for Black youth is positive and significant. The expected rate of missing time among days from Black youth is approximately 1.6 times greater compared to white youth. None of the other racial/ethnic groups are significantly different from white youth.

In Model 2, we add household level characteristics to investigate whether they account for the observed differences across age and race/ethnicity in Model 1. The two highest household income groups, $60,000-$150,000 and greater than $150,000 per year, have a significant negative effect. The negative direction of the effect indicates that adolescents from higher income families have fewer expected minutes of missing coverage across days in the GEMA week than adolescents from lower income households. Caregiver marital statuses other than being married are positively associated with the log expected missing time, but are not significant. With the introduction of these household resources control variables, the magnitude of the effect for black youth is reduced but still significant.

Model 3 adds whether the youth already has a phone or not. The effect is negative; youth who have a phone may be more familiar with the device and better able to keep the phone charged and connected to location services. Adding this control to the model does not appreciably affect the coefficients for individual and family characteristics except for a reduction in the magnitude of the coefficient for the oldest respondents ages 16-17, suggesting that some of the effect of age is mediated in part by older adolescents who already have a phone.

Model 4 adds neighborhood economic disadvantage, non-Hispanic black and residential instability. Disadvantage and proportion Black are both positive, but not significant, while instability is negative and also non-significant. The addition of the neighborhood level measures results in a further reduction in the magnitude of the effect for Black youth, though it is still significant.

To understand how behavioral tendencies may be related to GPS coverage and study protocol compliance, Model 5 adds a measure of youth self-reported delinquency. Youth who report any delinquent behaviors are not significantly different from those who report none. We find no systematic evidence that would be consistent with purposive efforts to minimize collection of location data on the device, perhaps associated with sensitive behaviors. However, delinquent behavior is also correlated with other characteristics that may influence phone management independent of deliberate efforts to conceal location. Model 6 adds self-control to examine whether conscientiousness affects compliance with the study protocol. Self-control is negative and significant; a one standard deviation increase in self-control is associated with a 14% decrease in minutes of missing GPS coverage. The negative effect of self-control is consistent with inadvertent or accidental GPS connectivity loss, rather than intentional evasion. Finally, Model 7 adds day of the GEMA study, which is positively associated with missing GPS coverage; days later in the GEMA week have more missing coverage. Adding GEMA day also reduces the magnitude of the self-control effect, suggesting that study fatigue is a factor in compliance across the week and partially accounts for the association between self-control and GPS coverage.

Discordance

Evidence of relatively high GPS coverage among AHDC subjects is encouraging; however, GPS coverage alone is no guarantee of the validity of the data collected. The space-time budget approach is designed to allow the subject to correct instances of invalid GPS data, commonly due to having left the phone (on) at home. Tables 3a (Models 1-3) and 3b (Models 4-5) presents the odds ratios from multilevel logistic regression models of discordance between the GPS data and the space-time budget data. We model the log odds of a day having greater than 95% of time at home as measured by the GPS data, while the space-time budget has less than or equal to 95% of the daily time at home. This discordance represents days when the phone was at home most or all of the day, but the youth respondent changed their activities to add non-home locations and activities during the prompted recall space-time budget session. On average, discordant days have 28% more time at home as measured by GPS than in the space-time budget. Although some small differences in percent of time at home may be due the difference in radii used to allocate time at home, the overall difference in time at home is non-trivial and represents potentially substantial differences in activity space exposures. These models assess whether day, youth, or neighborhood characteristics are associated with these changes, suggesting possible systematic variation in adjusting the accuracy of the raw GPS activity patterns.

Model 1 presents the coefficients for the school day indicator and youth level control variables.5 School day is significantly associated with the likelihood of discordance; school days are 1.8 times more likely to be discordant between the GPS and the space-time budget. Gender, age, racial/ethnic identity, caregiver marital status, and having a phone are not associated with GPS and space-time budget discordance. Carrying a study phone on school days may be an additional logistical burden due to school or parental policies regarding phone use, concerns about phone theft, or forgetfulness in the early morning school hours, resulting in inaccurate or missed activity patterns. The predicted probability of discordance among youth respondents on school days is .09, whereas the predicted probability on non-school days is .06, holding all other covariates in Model 1 at their means. Although there is a large proportionate increase in the predicted probability between school and non-school days, the absolute difference is minimal.

Model 2 adds neighborhood characteristics to the model. None of the three characteristics are significantly associated with day-level discordance between the GPS and space-time budget data, and their addition does not substantially change the positive effects of school day. Model 3 adds delinquency. Youth who report any lifetime delinquent behaviors are not more likely to have discordance days, on average. In Model 4, we add self-control. In contrast to models of GPS coverage, self-control is not associated with discordance. Model 5 adds the day of the space-time budget sequence, which is positively associated with discordance. Days reviewed later in the space-time budget process are more likely to be discordant than days completed earlier in the process. This effect is consistent with the finding that days later in the GEMA week are more likely to have missing GPS coverage, and suggests that respondents do not experience participation fatigue as they complete the space-time budget process (possibly resulting in a tendency to avoid correcting erroneous location data). .

Overall, individual level demographic and socioeconomic status do not appear to influence discordance, nor do neighborhood characteristics. Study phone management challenges associated with going to school while carrying the study phone are consistently associated with discordance in these analyses.

Supplementary Analyses

Alternative construction of the dependent variable – more than 75, 80, and 90% of time from the GPS was at home, while 75, 80, or 90% or less time in the space-time budget was at home, respectively – resulted in a significant and positive effect of the school day measure and the space-time budget day, consistent with the models presented here that school day and fatigue may be an important determinants of discordance. These models are equivalent with respect to the sign and significance of coefficients.

Conclusions

The median estimate of daily GPS coverage is 98 percent, indicating that youth charge the phones and maintain activated location services relatively consistently. The estimates reported here use a conservative approach, identifying gaps of at least 20 minutes or greater as missing. Using a higher tolerance for gap length would result in even more estimated coverage across the GEMA week. Overall, these findings point to the success of the GPS data collection, which also sets a strong foundation for the quality of the data derived from the space-time budget application. As expected, respondents who have a personal phone do have fewer minutes of missing coverage. Older adolescents and those from families with higher household income have less missing GPS coverage, net of having a cellphone already. However, conventionally employed measures of neighborhood structural characteristics – economic composition, racial composition, and residential instability – are not significantly related to GPS coverage.

In models of daily missing GPS coverage, Black adolescents have significantly more missing GPS coverage than white respondents. This effect is only partially explained by family socioeconomic status, family structure, and neighborhood characteristics. Black respondents have a similar number of gaps across the week due to low battery issues as other racial/ethnic groups. We speculate that perhaps the type of housing, school buildings, or built environment may provide interference in the GPS satellite connectivity for the Black youth in our sample. Other GPS-only travel surveys have noted gaps in GPS data in urban canyons and narrow alleyways with taller buildings (Chen, Gong, Lawson, & Bialostozky, 2010). Although Columbus is not as dense as major metropolitan areas such as New York or Chicago, researchers should be sensitive to the fact that differences in activity location paths may induce GPS coverage gaps if the surrounding built environment reduces the quality of satellite signals. In models not shown of missing GPS coverage, there was no significant interaction between school day and race/ethnicity in amount of time covered, which, although not a definitive test, suggests school location is not to blame.

We test measures of prior delinquent behavior and self-control to attempt to identify purposive or intentional loss of GPS coverage vs. unintentional loss of coverage. Delinquency is not associated with missing GPS coverage. Although self-control is not a direct measure of ability to comply with the study protocol, the negative effect on missing GPS coverage suggests conscientiousness may be a factor in GPS coverage. Additionally, the day of the study is associated with more missing coverage, indicating that fatigue across the week may be an issue. As the GEMA week progresses, participants are more like to have missing data. The overall high levels of GPS coverage and lack of association with prior risk behaviors suggest no wide-spread actions that we are able to detect to purposefully turn off location services for the GPS data collection.6

In models comparing the GPS and space-time budget data, we find that discordance was significantly more likely on school days. Several respondents mentioned to the interviewers that their caregivers were concerned about loss or theft at school and discouraged the youth from carrying the phone to school. Several local public schools also ban cellphones during the school day. In response to these comments, interviewers highlighted the importance of carrying the phone at all time whenever feasible, provided the respondent wouldn’t endanger their schooling experience. Note that the design of the study did not originally consider school time as “in scope”; however, we included school time in the current analysis in order to assess patterns of GPS coverage during this period of the day.

No demographic or neighborhood characteristics other than school day are associated with discordance. In contrast to models of GPS coverage, self-control is not associated with discordance. Conscientiousness as measured by self-control, therefore, affects overall coverage, but is not associated with leaving the phone at home all day and subsequently correcting the time to include non-home exposures.

These finding highlights the critical logistical decisions involved in the planning of the phone-based GPS tracking and GEMA assessment. The AHDC design gave each respondent a phone to use for the duration of the GEMA week. Providing a phone allows for significantly more control over the application and software to be installed, and introduces no variation across platforms or phone quality as sources of potential bias. While this makes the phone settings easier to control from the perspective of the study design, it also introduces potential burden for respondents who already have a personal phone. Respondents with a phone have better GPS coverage, possibly because they are more used to charging it, and keeping the location services on. But, we also find that respondents have more discordant days on school days regardless of having a personal phone, when early morning logistics or parental/school concerns may affect compliance. Thus, these days may have excellent GPS coverage while sitting at the respondents’ homes, but ultimately misrepresent daily activities. Good GPS coverage alone does not guarantee validity.

Future research projects considering the use of GPS-only data collection for assessing activity spaces may underestimate time spent outside of home for some subset of days. Although 7.1% of days in our sample are discordant when measuring time spent at home, there may be other ways in which GPS is biased from inaccurate points or the phone being left while the youth traveled elsewhere that are harder to detect. It is also possible that other days should have been discordant but the youth respondent did not correct or change the location and activity in the space time budget process with the interviewer due to recall bias or interviewer error in reporting location changes. The effects of the study design are also important to consider. The study day (as measured by what day in the sequence of collected days) is positively associated with discordance, consistent with our finding that days later in the GEMA week have lower levels of GPS coverage. Increasing discordance across the week also suggests that participants are willing to correct days later in the week despite awareness that the process will consume time during the space-time budget interview. . Having the prompted recall in the space-time budget process is preferred where feasible, given improved accuracy and the ability to adjust substantial errors (e.g. accurately placing the youth at school vs. home), despite the potential for some recall bias or interviewer error.

For studies where a prompted recall interview is not possible, we recommend GPS as an improved measure of true activity space exposures compared to survey-only data collection. In combination with EMA reports of locations as another more limited method of corroboration, passive collection of GPS on a study phone or the respondent’s own personal phone provides significantly more information about activity space contexts without any additional burden other than carrying the phone itself. Although there may be compliance issues related to carrying the phone, use of GPS only designs may be able to leverage enhanced EMA incentives to increase the likelihood that the youth will carry the phone and improve response rates about in the moment location reports. We also recommend detailed training for interviewers and participants on how to manage the study phone in order to maximize compliance, including ensuring location services (Wifi and GPS) are turned on at all times. The increasing ubiquity of cellphones in younger ages may improve compliance over time. High quality survey reports of activity locations can also be used to corroborate the validity of spatial data based on GPS-only designs, from which a buffer could be applied to the GPS data to check congruence (e.g., Kestens, Thierry, Shareck, Steinmetz-Wood, & Chaix, 2018).

The rapid increase in high quality modern smartphones has allowed for GEMA designs that are administered using a single device. Although smartphones still lag behind dedicated GPS devices in terms of battery and accuracy and may vary significantly across phone models (Gadziński, 2018; Montini, Prost, Schrammel, Rieser-Schüssler, & Axhausen, 2015; Shen & Stopher, 2014; Zandbergen & Barbeau, 2011), devices and their components–including GPS chip hardware–are changing faster than published research can keep up with. Modern smartphones also provide additional contextual information, including accelerometer data, battery life, and other phone usage data that aid in interpretation of compliance, understanding gaps in coverage, and adjudicating between stationary locations and travel time. Although the AHDC software was custom written–which potentially could limit the generalizability to other platforms–commercially available platforms increasingly include the ability to collect continuous GPS data within the context of EMA survey designs, making incorporation of GEMA into research more broadly available.

One prior study comparing activity space measurements using survey, GPS, and prompted recall methods found that survey-only activity spaces are smaller and less diverse than GPS or prompted recall methods (Kestens et al., 2018; Shareck et al., 2013). Systematic differences in true activity space exposures between adolescents in the same neighborhood and across neighborhoods that drive many of the theoretical mechanisms of neighborhood and spatial effects research cannot be tested with residential neighborhood or survey measures alone. Although AHDC is set in one urban area, it is the largest population-based sample to date that uses GEMA methodology to construct and assess adolescent activity spaces as well as in-the-moment collection of social contexts, behaviors, and health. The overall success of the GEMA data collection in the context of the AHDC study bodes well for future data collection projects employing this methodology. Ongoing challenges to the implementation of GEMA data collection remain, however, and additional research on best practices associated with this methodology is a critical need for research on adolescent development.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA032371), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (R01HD088545), the William T. Grant Foundation, and the Ohio State University Institute for Population Research (NICHD P2CHD058484).

Footnotes

The AAPOR 3 response rate includes the estimated proportion of cases with unknown eligibility that is actually eligible in the denominator. Although low by historical standards, the AHDC AAPOR 3 response rate reflects recent trends afflicting social survey response rates globally (National Research Council, 2013).

We present data collected from a staff member to visualize the methods while preserving respondent confidentiality.

Twelve participants have no GPS data over the GEMA week, due to partial interviews (4 cases) and due to technological difficulties or interviewer error in setting up the phone (8 cases). Six participants are excluded from current analyses due to errors in their GPS that suggest they changed the time on their phone. While this may represent accidental and/or purposeful tampering, we exclude them because the data is unreliable for measuring daily coverage. An additional 8 participants are excluded from all analyses due to scheduling issues regarding their in-home survey and EMA prompts that result in non-matching days being collected under the space-time budget.

There are 6,395 GPS days that match to space-time budget days from 1,331 respondents. Once limiting the sample to non-missing covariates, the number of days available for analysis is 5,723 from 1,192 respondents. We further exclude 310 days with no GPS coverage for the day.

Model 1 in Table 3a is equivalent to Table 2a Model 3 in the GPS analysis to be parsimonious. We omit the sequential models with individual and day level controls prior to including whether the youth has a phone since the results are similar to Model 1 presented here despite the addition of having a phone.

We examined alternative measures of behavioral problems (e.g. violence), finding no effect on either GPS coverage or discordance.

Contributor Information

Bethany Boettner, Email: boettner.6@osu.edu.

Christopher R. Browning, Email: browning.90@osu.edu.

Catherine A. Calder, Email: calder@stat.osu.edu.

References

- Anderson J (1971). Space-time budgets and activity studies in urban geography and planning. Environment and Planning A, 3(4), 353–368. 10.1068/a030353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auld J, & Mohammadian A (2014). Collecting Activity-Travel and Planning Process Data Using GPS-Based Prompted Recall Surveys: Recent Experience and Future Directions. Hersey: Igi Global. [Google Scholar]

- Auld J, Williams C, Mohammadian A, & Nelson P (2009). An automated GPS-based prompted recall survey with learning algorithms. Transportation Letters, 1(1), 59–79. 10.3328/TL.2009.01.01.59-79 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bricka SG, Sen S, Paleti R, & Bhat CR (2012). An analysis of the factors influencing differences in survey-reported and GPS-recorded trips. Transportation Research Part C-Emerging Technologies, 21(1), 67–88. 10.1016/j.trc.2011.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA, & Boettner B (2016). Neighborhoods, activity spaces, and the life course In Shanahan MJ, Mortimer JT, & Johnson MK (Eds.), Handbook of the Life Course (Vol. II, pp. 597–620). New York, NY: Springer; Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-20880-0_26/fulltext.html [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, & Soller B (2014). Moving beyond neighborhood: Activity spaces and ecological networks as contexts for youth development. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 16(1), 165–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Morrison CN, Wiebe DJ, Woychik M, & Wiehe SE (2017). Association of environmental indicators with teen alcohol use and problem behavior: Teens’ observations vs. objectively-measured indicators. Health & Place, 43, 151–157. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DV, Helfrich CA, Hursh NC, Sally Rogers E, & Gopal S (2014). Measuring community integration using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and participatory mapping for people who were once homeless. Health & Place, 27, 92–101. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Gong H, Lawson C, & Bialostozky E (2010). Evaluating the feasibility of a passive travel survey collection in a complex urban environment: Lessons learned from the New York City case study. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 44(10), 830–840. 10.1016/j.tra.2010.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Kawabata K, Intille S, Wolch J, & Pentz MA (2012). Assessing the Social and Physical Contexts of Children’s Leisure-Time Physical Activity: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. American Journal of Health Promotion, 26(3), 135–142. 10.4278/ajhp.100211-QUAN-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Tyburski M, Craig IM, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Vahabzadeh M, … Preston KL (2014). Real-time tracking of neighborhood surroundings and mood in urban drug misusers: Application of a new method to study behavior in its geographical context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 22–29. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler B, Lipperman-Kreda S, Bersamin M, & Gruenewald PJ (2015). Tracking the When, Where, and With Whom of Alcohol Use: Integrating Ecological Momentary Assessment and Geospatial Data to Examine Risk for Alcohol-Related Problems. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 36(1), 29–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadziński J (2018). Perspectives of the use of smartphones in travel behaviour studies: Findings from a literature review and a pilot study. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 88, 74–86. 10.1016/j.trc.2018.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giaimo G, Anderson R, Wargelin L, & Stopher P (2010). Will It Work? Pilot Results from First Large-Scale Global Positioning System-Based Household Travel Survey in the United States. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2176, 26–34. 10.3141/2176-03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graif C, Gladfelter AS, & Matthews SA (2014). Urban poverty and neighborhood effects on crime: Incorporating spatial and network perspectives. Sociology Compass, 8(9), 1140–1155. 10.1111/soc4.12199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves S, Fifer S, Ellison R, & Germanos G (2010). Development of a Global Positioning System Web-Based Prompted Recall Solution for Longitudinal Travel Surveys. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2183, 69–77. 10.3141/2183-08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, & Pebley AR (2014). Redefining neighborhoods using common destinations: Social characteristics of activity spaces and home census tracts compared. Demography, 51(3), 727–752. 10.1007/s13524-014-0283-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestens Y, Thierry B, Shareck M, Steinmetz-Wood M, & Chaix B (2018). Integrating activity spaces in health research: Comparing the VERITAS activity space questionnaire with 7-day GPS tracking and prompted recall. Spatial and Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology, 25, 1–9. 10.1016/j.sste.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestens Y, Wasfi R, Naud A, & Chaix B (2017). “Contextualizing Context”: Reconciling Environmental Exposures, Social Networks, and Location Preferences in Health Research. Current Environmental Health Reports, 4(1), 51–60. 10.1007/s40572-017-0121-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, & Shiffman S (2016). Spatio-temporal determinants of mental health and well-being: advances in geographically-explicit ecological momentary assessment (GEMA). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(9), 1211–1223. 10.1007/s00127-016-1277-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan M-P (2013). Beyond space (as we knew it): Toward temporally integrated geographies of segregation, health, and accessibility. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 103(5), 1078–1086. 10.1080/00045608.2013.792177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Dupéré V, & Brooks-Gunn J (2009). Neighborhood influences on adolescent development In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 411–443). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M, Mennis J, Light J, Rusby J, Westling E, Crewe S, … Zaharakis N (2016). Parents, Peers, and Places: Young Urban Adolescents’ Microsystems and Substance Use Involvement. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(5), 1441–1450. 10.1007/s10826-015-0344-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SA, & Yang T-C (2013). Spatial Polygamy and Contextual Exposures (SPACEs): Promoting activity space approaches in research on place and health. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1057–1081. 10.1177/0002764213487345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason M, Ambrus A, Way T, & Henry K (2017). The spatial accuracy of geographic ecological momentary assessment (GEMA): Error and bias due to subject and environmental characteristics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178(Supplement C), 188–193. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Schick RS, Hallyburton M, Dennis MF, Kollins SH, Beckham JC, & McClernon FJ (2014). Combined Ecological Momentary Assessment and Global Positioning System Tracking to Assess Smoking Behavior: A Proof of Concept Study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 10(1), 19–29. 10.1080/15504263.2013.866841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini L, Prost S, Schrammel J, Rieser-Schüssler N, & Axhausen KW (2015). Comparison of Travel Diaries Generated from Smartphone Data and Dedicated GPS Devices. Transportation Research Procedia, 11, 227–241. 10.1016/j.trpro.2015.12.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2013). Nonresponse in social science surveys: A research agenda. (Tourangeau R & Plewes Thomas J., Eds.). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; Retrieved from 10.17226/18293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noah AJ (2015). Putting Families Into Place: Using Neighborhood-Effects Research and Activity Spaces to Understand Families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(4), 452–467. 10.1111/jftr.12119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JRB, Espenshade T, Bartumeus F, Chung C, Ozgencil N, & Li K (2013). New approaches to human mobility: Using mobile phones for demographic research. Demography, 50(3), 1105–1128. 10.1007/s13524-012-0175-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raento M, Oulasvirta A, & Eagle N (2009). Smartphones: An emerging tool for social scientists. Sociological Methods & Research, 37(3), 426–454. 10.1177/0049124108330005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Bazzi AR, & Fish S (2016). Ethical considerations and potential threats to validity for three methods commonly used to collect geographic information in studies among people who use drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 84–90. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Young AM, & Havens JR (2017). A rural/urban comparison of privacy and confidentiality concerns associated with providing sensitive location information in epidemiologic research involving persons who use drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 74, 106–111. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safi H, Assemi B, Mesbah M, & Ferreira L (2017). An empirical comparison of four technology-mediated travel survey methods. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition), 4(1), 80–87. 10.1016/j.jtte.2015.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, & Gannon-Rowley T (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443–478. 10.2307/3069249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shareck M, Kestens Y, & Gauvin L (2013). Examining the spatial congruence between data obtained with a novel activity location questionnaire, continuous GPS tracking, and prompted recall surveys. International Journal of Health Geographics, 12(1), 40 10.1186/1476-072X-12-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp G, Denney JT, & Kimbro RT (2015). Multiple contexts of exposure: Activity spaces, residential neighborhoods, and self-rated health. Social Science & Medicine, 146, 204–213. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, & Stopher PR (2014). Review of GPS Travel Survey and GPS Data-Processing Methods. Transport Reviews, 34(3), 316–334. 10.1080/01441647.2014.903530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovsky AW, Mermelstein RJ, & Hedeker D (2014). Factors predicting compliance to ecological momentary assessment among adolescent smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(3), 351–358. 10.1093/ntr/ntt154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugie NF (2016). Utilizing smartphones to study disadvantaged and hard-to-reach groups. Sociological Methods & Research, 47(3), 458–491. 0049124115626176. 10.1177/0049124115626176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugie NF, & Lens MC (2017). Daytime locations in spatial mismatch: Job accessibility and employment at reentry from prison. Demography, 1–26. 10.1007/s13524-017-0549-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen CKF, Schneider S, Stone AA, & Spruijt-Metz D (2017). Compliance with mobile ecological momentary assessment protocols in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(4), e132 10.2196/jmir.6641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehe SE, Carroll AE, Liu GC, Haberkorn KL, Hoch SC, Wilson JS, & Fortenberry JD (2008). Using GPS-enabled cell phones to track the travel patterns of adolescents. International Journal of Health Geographics, 7(1), 22 10.1186/1476-072X-7-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P-OH, & Svensson R (2010). When does self-control matter? The interaction between morality and self-control in crime causation. European Journal of Criminology, 7(5), 395–410. 10.1177/1477370810372132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Raja S, Li X, Lai Y, Epstein L, & Roemmich J (2013). Neighbourhood for playing: Using GPS, GIS and accelerometry to delineate areas within which youth are physically active. Urban Studies, 50(14), 2922–2939. 10.1177/0042098013482510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- York Cornwell E, & Cagney KA (2017). Aging in activity space: Results from smartphone-based gps-tracking of urban seniors. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 72(5), 864–875. 10.1093/geronb/gbx063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]