Abstract

Rationale: Little direction exists on how to integrate early palliative care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Objectives: We sought to identify patient and family caregiver early palliative care needs across stages of COPD severity.

Methods: As part of the Medical Research Council Framework developmental phase for intervention development, we conducted a formative evaluation of patients with moderate to very severe COPD (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]/FVC < 70% and FEV1 < 80%-predicted) and their family caregivers. Validated surveys on quality of life, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and social isolation quantified symptom severity. Semi-structured interviews were analyzed for major themes on early palliative care and needs in patients and family caregivers and across COPD severity stages.

Results: Patients (n = 10) were a mean (±SD) age of 60.4 (±7.5) years, 50% African American, and 70% male, with 30% having moderate COPD, 30% severe COPD, and 40% very severe COPD. Family caregivers (n = 10) were a mean age of 58.3 (±8.7) years, 40% African American, and 10% male. Overall, 30% (n = 6) of participants had poor quality of life, 45% (n = 9) had moderate–severe anxiety symptoms, 25% (n = 5) had moderate–severe depressive symptoms, and 40% (n = 8) reported social isolation. Only 30% had heard of palliative care, and most participants had misconceptions that palliative care was end-of-life care. All participants responded positively to a standardized description of early palliative care and were receptive to its integration as early as moderate stage. Five broad themes of early palliative care needs emerged: 1) coping with COPD; 2) emotional symptoms; 3) respiratory symptoms; 4) illness understanding; and 5) prognostic awareness. Coping with COPD and emotional symptoms were commonly shared early palliative care needs. Patients with very severe COPD and their family caregivers prioritized illness understanding and prognostic awareness compared with those with moderate–severe COPD.

Conclusions: Patients with moderate to very severe COPD and their family caregivers found early palliative care acceptable and felt it should be integrated before end-stage. Of the five broad themes of early palliative care needs, coping with COPD and emotional symptoms were the highest priority, followed by respiratory symptoms, illness understanding, and prognostic awareness.

Keywords: COPD, palliative care, qualitative research, caregivers, symptoms

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States (1), and, as the disease progresses, patients experience poor quality of life (QOL) due to progressively debilitating dyspnea, untreated emotional symptoms, and social isolation (2, 3). Patients with COPD commonly live for years with symptom burden on par with those who have advanced cancer, and hence experience needs that could be addressed by specialist palliative care (4, 5). However, palliative care is rarely offered in COPD; rather, it is typically provided within the context of hospice care primarily in the last 6 months of life, thus limiting its potential impact on improving patient-centered outcomes for individuals with COPD (6–9). In contrast, an early palliative care model integrates outlook planning and physical, emotional, spiritual, and social support alongside routine chronic disease care from the time of diagnosis (10). Data in advanced lung cancer suggest that early palliative care delivered by a specialist clinician or palliative care nurse improves QOL and reduces healthcare utilization (11, 12). Professional guidelines recommend early palliative care in the course of multiple chronic illnesses to optimize supportive care delivered in concert with standard disease management (13, 14). However, there is limited guidance on how to integrate early palliative care in the trajectory of COPD.

Data in advanced COPD illustrate significant unmet needs and a potential benefit from early palliative care in physical symptoms, social isolation, and reduced healthcare utilization (15, 16). However, it may be that patients with COPD with less severe disease have different needs. Similarly, family caregivers express stress caring for a loved one with advanced COPD (17), yet COPD family caregiver research is limited (18). Furthermore, no studies have explored perspectives on early palliative care needs in COPD across GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) stages or in underserved populations (19).

We conducted a formative evaluation study of a racially diverse sample of patients with moderate to very severe COPD and their family caregivers with three primary research questions: 1) how do patients with COPD and family caregivers perceive early palliative care?; 2) what are their perspectives on early palliative care needs?; and, 3) do patients with different levels of COPD severity and symptom burden express different early palliative care needs? Our overarching goal was to identify broad themes on early palliative care needs that would inform development of an early palliative care intervention for patients with COPD and their family caregivers across stages of COPD severity.

Methods

As part of the Medical Research Council framework for developing complex interventions, and informed by our prior research (20–22), we conducted a formative evaluation qualitative descriptive study of patients with COPD and their family caregivers (23, 24). Between October 2017 and January 2017, we purposively sampled adults aged 40 years and older with COPD who attended a pulmonary clinic at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), a tertiary referral center for Alabama. Our purposive sampling strategy sought to balance participants of different ethnicities and COPD severity to capture a broad range of experiences about early palliative care (23). We used routinely collected spirometry data and defined COPD as a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio less than 0.70 with the following GOLD spirometric stages: GOLD stage II (moderate COPD: 50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%); GOLD III (severe COPD: 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%); and GOLD IV (very severe COPD: FEV1 < 30%) (25). Additional literature-informed patient inclusion criteria obtained by chart review included one or more of the following (26): 1) one or more COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization in the prior year; 2) on supplemental oxygen; or 3) had self-reported severe dyspnea as a modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale score of 2 or greater, routinely recorded in the electronic medical record. Consistent with our prior research, patients were required to have a participating family caregiver, defined as an unpaid, close relative, partner, or friend of 19 years of age or older who played an important role in helping the patient with day-to-day activities or medical care (20). We excluded patients with primary lung diseases other than COPD, who were being treated for comorbid cancer in the prior 2 years, and who had a medical record determined or self-reported history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia. Family caregivers were also excluded if they had a history of self-reported schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or dementia. The UAB Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB no. 170209003). Patient and family caregiver participants provided informed consent.

Data Collection

Semistructured interviews of palliative care awareness and early palliative care needs

Three authors (A.S.I., J.N.D.-O., and M.A.B.) developed a semistructured interview guide informed by our prior work to explore perspectives of patients with COPD and family caregivers on early palliative care needs (see Table E2 in the online supplement) (20, 27). Interviews explored prior knowledge of palliative care and asked participants to respond to the following early palliative care definition: “specialized medical care for people that provides physical, emotional, spiritual, and social support for patients and their family caregivers, offers an extra layer of support to improve QOL at any stage of serious illness, and is appropriate at any stage alongside routine medical treatment.” (28). We then explored early palliative care timing and needs in COPD. The principal investigator (A.S.I.), a male, specialist pulmonary-critical care physician and COPD clinical investigator with training in qualitative methods, introduced himself to participants and described the overall study goals, then conducted in-person interviews of patients and caregivers separately to ensure perspectives were not biased by dyadic relationships. Interviews lasted 60 minutes on average, were conducted in a private clinic space, audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim using a professional transcription service. The principal investigator reviewed all transcripts against recordings for accuracy. Participants each received a $25 incentive to complete the interview and questionnaires.

Patient and family caregiver demographic, QOL, and symptom data

At the time of the interview, participants completed a demographic sheet on age, race, sex, marital status, education (high school graduate vs. not), health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured), smoking status (current vs. former), religious preference, attendance at religious services, use of prayer for health, and patient-specific clinical data that included supplemental oxygen use, cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, comorbidities by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (sum of 19 comorbidities; higher scores associated with greater mortality risk) (29), prior palliative care and hospice use, identification of a surrogate decision maker, and completion of an advance directive. We asked patients and their family caregivers to complete the following questionnaires administered by a trained study coordinator at the time of the interview: 1) PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) Global Health-10 to measure QOL; 2) PROMIS Emotional Distress Anxiety Short Form-8B to measure anxiety symptoms; 3) PROMIS Emotional Distress Depression Short Form-8B to measure depressive symptoms (30); and 4) the UAB Life Space Assessment (LSA) to measure life-space mobility, a marker of social isolation. We used the National Institutes of Health PROMIS initiative tools to allow comparison with the general population, and these instruments have been validated in COPD (30–33). The PROMIS Global Health-10 is a 10-item measure with physical and mental health domains that has been linked to many commonly used rating systems for QOL (34). Nine questions are rated on a 5-point Likert-scale, and the 10th question rates pain on a scale of 0–10. Using online conversion tables for the physical health domain, we converted raw scores to standardized t-scores ranging from 0 to 100, with lower scores representing worse QOL. Consistent with PROMIS recommendations and linkage data to validated surveys, we defined poor QOL as a t-score of 35 points or less (35, 36). The PROMIS Emotional Distress Anxiety Short Form-8B and the PROMIS Emotional Distress Depression Short Form-8B include seven and eight Likert-scale questions, respectively, each ranging from 0 to 5 (33, 37). Raw scores range from 7 to 35 on the Anxiety Short From and from 8 to 40 on the Depression Short Form. We used online conversion tables to convert raw scores to standardized t-scores that range from 0 to 100, with higher scores associated with greater anxiety and depressive symptoms. We defined moderate–severe anxiety or depressive symptoms as t-score of 60 or greater or greater than 1 SD above the population mean of 50 on each instrument, which has previously been validated (38). The UAB LSA is a 15-item survey of life-space mobility (i.e., the distance, frequency, and independence of movement in the 4 wk before administration). Restricted life-space mobility (LSA ≤60) is a marker of social isolation in community-dwelling older adults (39). We have previously validated restricted life-space mobility as a predictor of severe exacerbations and early palliative care needs in patients with moderate to very severe COPD (40).

Data Analysis

Two members of the study team (A.S.I. and M.A.B.) performed a thematic content analysis by separately coding a subset of transcripts to build the initial codebook, to extract converging themes, and to reach consensus on themes simultaneously with data collection (41–43). Codes were continuously refined and iteratively merged to construct themes of early palliative care needs. Member checking was conducted throughout as previous participant insights were shared with future participants (e.g., “A number of participants have said X. What is your perspective on this issue?”). Guided by theoretical and inductive saturation models, we determined that the total sample size would be that which achieved thematic saturation, or when no new information, codes, or themes emerged (24, 44). We reported the frequency of the major themes as “all,” “most,” and “some” to denote the general proportion of participants who reported each theme. We presented themes on early palliative care needs in patient and their family caregiver participants and across GOLD stages as patients with GOLD IV COPD and their family caregivers as compared with GOLD II–III stages. All coding was completed using NVivo 11 (QSR International). Descriptive data were analyzed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS 23.0, SPSS Inc.) and reported as frequencies (%) for categorical data and means (±SD) for continuous data. We adhered to guidelines from the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), which can be found in the Table E1 in the online supplemental (60).

Results

Sample Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We reached thematic saturation at eight patient–family caregiver dyads and enrolled to 10 dyads for a total of 20 participants. Three additional dyads declined to participate due to scheduling conflicts of the family caregiver. As shown in Table 1, patients (n = 10) had a mean (±SD) age of 60.4 (±7.5) years, 50% were African American, 70% were male, and 30% were uninsured. The mean % predicted FEV1 was 37.4 (±20.4), and patients represented the spectrum of GOLD stages: 30% GOLD II (moderate), 30% GOLD III (severe), and 40% GOLD IV (very severe). Only one patient had an advance directive, and 30% had identified a surrogate decision maker (Table 1). Family caregivers (n = 10) had a mean age of 58.3 (±8.7) years, 40% were African American, and 10% were male (Table 1). Family caregivers represented the following relationships with patients: spouse (40%), ex-spouse (20%), significant other (20%), child (10%), and parent (10%). Overall, 30% (n = 6) of participants had poor QOL, 45% (n = 9) had moderate–severe anxiety symptoms, 25% (n = 5) had moderate–severe depressive symptoms, and 40% (n = 8) reported social isolation (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient and caregiver participant characteristics (n = 20)

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 10) | Family Caregivers* (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age, yr | 60.4 ± 7.5 | 58.3 ± 8.7 |

| African American race, % | 5 (50) | 4 (40) |

| Male sex, % | 7 (70) | 1 (10) |

| Married, % | 3 (30) | 5 (50) |

| Education (high school graduate), % | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Health insurance, % | ||

| Medicare | 5 (50) | 5 (50) |

| Uninsured | 3 (30) | 1 (10) |

| Current Smoking, % | 5 (50) | 4 (40) |

| Religious preference | ||

| Protestant, % | 1 (10) | 3 (30) |

| None, % | 3 (30) | 1 (10) |

| Regularly attends religious services | 1 (10) | 7 (70) |

| Ever prayed for own health | 7 (70) | 9 (90) |

| Prior palliative care | 1 (10) | n/a |

| Advanced directive | 1 (10) | n/a |

| Identified surrogate decision maker | 3 (30) | n/a |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index† | 1.5 ± 1.0 | n/a |

| GOLD Stage‡ | ||

| GOLD II (moderate), % | 3 (30) | n/a |

| GOLD III (severe), % | 3 (30) | n/a |

| GOLD IV (very severe), % | 4 (40) | n/a |

| FEV1 % predicted | 37.4 ± 20.4 | n/a |

| Supplemental oxygen, % | 8 (80) | n/a |

| ≥One severe exacerbations in the year prior, % | 3 (30) | n/a |

| Prior cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, % | 4 (40) | n/a |

| Severe dyspnea§ | 8 (80) | n/a |

Definition of abbreviations: FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Family caregivers represented the following relationships with patients: spouse (n = 4), ex-spouse (n = 2), significant other (n = 2), child (n = 1), and parent (n = 1).

Derived from 19 comorbidities; higher scores associated with higher mortality.

Moderate = 50% ≤ FEV1 < 80%; severe = 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50%; very severe = FEV1 < 30%.

≥2 on the Modified Medical Research Council scale for dyspnea.

Table 2.

Patient and family caregiver quality of life and symptom burden (n = 20)

| Survey | Patients Mean ± SD or n (%) (n = 10) | Family Caregivers mean ± SD or n (%) (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|

| PROMIS Global Health-10, Physical Health Domain t-score | 35.8 ± 5.5; range = 26.7–44.9 | 46.2 ± 12.8; range = 23.5–67.7 |

| Poor quality of life* | 4 (40) | 2 (20) |

| PROMIS Emotional Distress-Anxiety Short Form t-score | 58.3 ± 13.6; range = 42.1–75.8 | 61.0 ± 15.6; range = 42.1–82.7 |

| Moderate–severe anxiety symptoms† | 4 (40) | 5 (50) |

| PROMIS Emotional Distress-Depression Short Form t-score | 51.1 ± 11.8; range = 37.1–68.3 | 53.4 ± 10.5; range = 37.1–66.3 |

| Moderate–severe depressive symptoms‡ | 2 (20) | 3 (30) |

| UAB Life Space Assessment score | 49.5 ± 26.3; range = 15–102 | 72.9 ± 26.3; range = 35.120 |

| Social isolation§ | 6 (60) | 2 (20) |

Definition of abbreviations: PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; UAB = University of Alabama at Birmingham.

PROMIS Global Health-10, Physical Health Domain t-score ≤35 (<1.2 SD below mean; lower scores worse).

PROMIS-Emotional Distress Anxiety t-score ≥60 (>1 SD above the mean; higher scores worse).

PROMIS-Emotional Distress Depression t-score ≥60 (>1 SD above the mean; higher scores worse).

UAB Life Space Assessment Score ≤60 (lower scores worse).

Patient and Family Caregiver Understanding of Palliative Care

To establish a baseline, we asked participants about their general knowledge of palliative care and hospice

Only six (30%) participants had heard of palliative care, and exemplary quotes in Table 3 demonstrate a misconception that palliative care was synonymous with end-of-life care. On the other hand, all participants had heard of hospice care, and exemplary quotes illustrate that participants had a better understanding of hospice (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient and family caregiver quotes on palliative care and hospice

| Question | Answers |

|

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Family Caregivers | |

| What does palliative care mean to you? | “To make the pain go away or somethin'.” (PT003, 72-yr-old WM, FEV1 26%) | “Just helping me get through to a normal, everyday living situation and maybe set goals.” (CG007, 65-yr-old WF to PT007, 63-yr-old WM, FEV1 38%) |

| “Easing your way along, that end of life thing. I think of palliative care as comfort care, making you more comfortable along the way.” (CG003, 62-yr-old WF to PT003, 72-yr-old WM, FEV1 26%) | ||

| “That’s care that you get in the last stages of your condition.” (PT010, 71-yr-old AAF, FEV1 71%) | “I think he is very scared of dying from not breathing. Palliative care is part of dying, I think. I may be wrong.” (CG001, 60-yr-old WF to PT001, 57-yr-old WM, FEV1 32%) | |

| “Making life easier. Not changing the outcome, but making life easier.” (CG004, 73-yr-old WF to PT004, 53-yr-old WF, FEV1 16%) | ||

| What does hospice mean to you? | “Hospice means a doctor has determined you only have a short time to live. During that time, the care you receive is palliative care. It's not so invasive.” (PT003, 72-yr-old WM, FEV1 26%) | “(Hospice is) for people who are terminal. It’s your time. They’re just gonna be there with you to support your family while you’re dyin’.” (CG006, 53-yr-old WF to PT006, a 56-yr-old WM with FEV1 13%) |

| “Hospice takes over the drugs. Palliative care does not.” (CG004, 73-yr-old WF to PT004, 53-yr-old WF, FEV1 16%) | ||

| “Pretty much a person who is at the end of their life.” (PT005, 49-yr-old AAF, FEV1 70%) | “I think [hospice] is the last part of whatever the doctors can do, and they’re just tryin’ to make you comfortable while you’re here.” (CG002, 61-yr-old AAF to PT002, 65-yr-old AAM, FEV1 33%) | |

| “Hospice to a lot of people means terminal. It’s your time. They’re just gonna be there with you to support your family while you’re dyin’.” (CG006, 53-yr-old WF to PT006, 56-yr-old WM, FEV1 13%) | ||

| “Where they take care of people who can’t take care of themselves. Basically give them the attention that they need, that they would normally have to go to an institution like a hospital or somethin’. They can receive it at home instead of being hospitalized. It's basically like a home hospitalization.” (PT002, 65-yr-old AAM, FEV1 33%) | “That’s where you’re at the end. My sister, I watched her die. She was in hospice.” (CG007, 65-yr-old WF to PT007, 63-yr-old WM, FEV1 38%) | |

| “Oh, that’s like the end right there.” (PT009, 57-yr-old AAM, FEV1 50%) | “To me, as I’ve been around people who had to end up having hospice care, they can’t do for themselves. They’re about to leave this world. They also assist the family with different things.” (CG008, 61-yr-old AAF to PT008, 61-yr-old AAM, FEV1 25%) | |

Definition of abbreviations: AAF = African American female; AAM = African American male; CG = caregiver; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 s; PT = patient; WF = white female; WM = white male.

Perspectives on Early Palliative Care and Needs

All participants responded positively when we provided them with a standardized definition of early palliative care

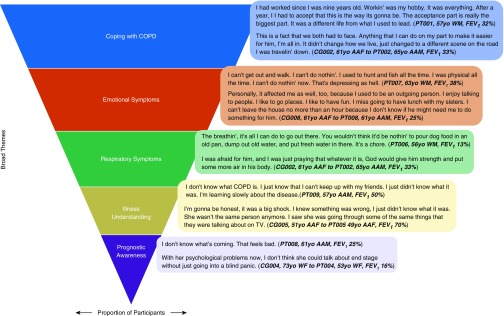

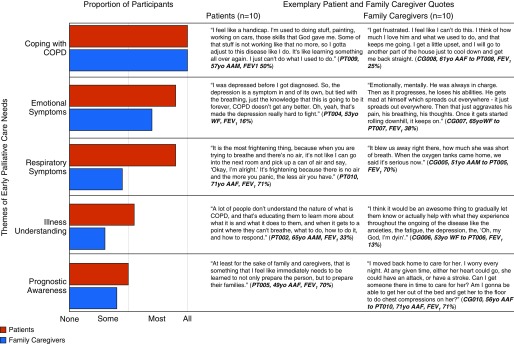

Figure 1 illustrates the five broad themes of early palliative care needs that emerged in interviews and the general proportions that participants discussed for each theme. All participants discussed coping with COPD, most discussed emotional symptoms followed by respiratory symptoms, and some discussed illness understanding followed by prognostic awareness. Figure 2 illustrates that patient and family caregiver participants shared several themes on early palliative care needs. Exemplary quotes illustrate that participants seemed to express a fear of the unknown, both with respect to COPD and its prognosis.

Figure 1.

Broad themes of early palliative care needs in patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and their family caregivers. This figure illustrates the major themes that emerged in the interviews, with the area of each row representing the proportion of patient and family caregiver participants who raised this theme. AAF = African American female; AAM = African American male; CG = caregiver; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PT = patient; WF = white female; WM = white male.

Figure 2.

Differences in early palliative care needs between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients and family caregivers. This figure displays the proportions of patients and family caregivers who discussed the major themes alongside exemplary quotes for each category. AAF = African American female; AAM = African American male; CG = caregiver; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PT = patient; WF = white female; WM = white male.

Timing of Early Palliative Care

We then explored perspectives on the timing of early palliative care. All participants did not see a need to institute early palliative care in mild (GOLD I stage) COPD. Instead, they favored incorporating early palliative care beginning in the moderate stage. For instance, one patient stated:

“If I would have been in stage one, I would have been breathing a little better, and it probably wouldn't have rung a bell like it would have in stage four.” (PT001, 57-yr-old white male with FEV1 32%).

Similarly, a family caregiver did not support early palliative care being instituted in mild COPD:

“No, too early. Because you're not really believing that the disease is going to progress the way it’s going to progress.” (CG003, 62-yr-old white female to PT003, 72-yr-old white male with FEV1 26%).

Another family caregiver stated:

“I think people are still in denial at that point. I would want it to be in moderate stage.” (CG004, 73-yr-old white female to PT004, 53-yr-old white female with FEV1 16%).

Priority Early Palliative Care Needs by GOLD Stage

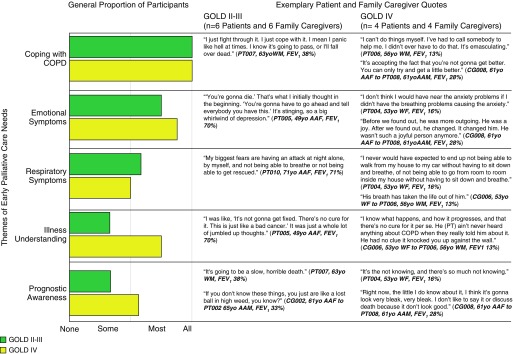

Figure 3 illustrates the combined patient and family caregiver early palliative care themes in GOLD IV and GOLD II–III stages. All patient participants across GOLD stages and their family caregivers discussed themes of coping with COPD. The proportions of participants reporting emotional symptoms and respiratory symptoms themes were similar in GOLD IV and GOLD II–III stages. More patient and family caregiver participants from GOLD IV compared with GOLD II–III prioritized themes on illness understanding and prognostic awareness (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patient and family caregiver early palliative care needs by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) stage. This figure displays the differences in the proportions of the major themes in patients with GOLD II–III stage COPD and their family caregivers compared with those from GOLD IV stages, alongside exemplary quotes for each. AAF = African American female; AAM = African American male; CG = caregiver; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PT = patient; WF = white female; WM = white male.

Discussion

Five themes of early palliative care needs emerged in a cohort of patients with moderate to very severe COPD and their family caregivers: coping with COPD; emotional symptoms; respiratory symptoms; illness understanding; and prognostic awareness. Themes of coping with COPD and emotional symptoms were highest priority. Most themes of early palliative care needs were common across COPD severity stages; thus, the current practice of limiting palliative care to “end-stage” COPD misses an important opportunity to reap QOL and symptom benefits that have been demonstrated when early palliative care is introduced in less severe stages of disease. When we provided patient and family caregiver participants with a standardized definition of early palliative care, they expressed a universal desire to have access to early palliative care. Consistent with the overall study goal, the data informed development of an early palliative care intervention for patients with COPD and their family caregivers across disease severity.

This study used a formative evaluation approach guided by the Medical Research Council framework to identify early palliative care needs of patients and family caregivers as a critical first step in intervention development (20, 21). Our purposively selected cohort included patients across COPD severity stages with a mix of races, and incorporated the key support needs of their family caregivers. This study is one of the first to demonstrate that early palliative care needs are not limited to very severe or end-stage COPD, which is the current status of traditional specialist palliative care referral in COPD and GOLD recommendations (25). Patients and family caregivers confirmed that reserving palliative care for end-stage COPD is too late; instead, our data suggest that early palliative care should begin as early as moderate (GOLD II) stage COPD. Furthermore, our cohort was 50% African American and 20% uninsured, a population in which palliative care referral is limited (19, 45, 46). The data support the development of early palliative care interventions to meet patient and family caregiver needs in diverse populations across the continuum of COPD.

Expanding early palliative care beyond cancer to nonmalignant chronic disease has not yet been well accepted, in part due to a limited awareness of and misconceptions of palliative care (47, 48). Our data are consistent with national data where palliative care in its traditional sense is often mislabeled as being end-of-life or hospice care, which confines this service to end-stage disease (5, 28, 49). Our cohort demonstrated a basic understanding of palliative care, though misconceptions existed. Conversely, participants unanimously welcomed early palliative care once we defined this service. We are not certain that our data indicate if early palliative care should be provided by a specialist clinician in the traditional sense, or if pulmonologists, palliative care nurses, or respiratory nurses and therapists could be trained in primary palliative care. Future research should investigate these delivery models and how professional education programs could boost understanding of early palliative care and primary palliative care in the field of pulmonary medicine for COPD patients.

The highest priority theme that emerged in our data was coping with COPD, and, as a result, we placed the greatest emphasis on incorporating this theme during intervention development. The theme of coping with COPD was discussed by all patient and family caregiver participants and across GOLD stages. Variations in patients’ coping abilities across COPD severity stages appear to moderate the interaction between lung function and QOL, wherein reduced FEV1 does not necessarily translate to poor QOL (50). Data reveal that an inability to cope with progressive COPD is associated with more severe emotional symptoms and mortality (51). Early palliative care interventions in advanced cancer improve active coping strategies compared with usual care, helping patients and their family caregivers to positively reframe the diagnosis and to learn how to use active rather than avoidant-oriented strategies of coping that worsened QOL (52). Patients who learn active coping strategies show reductions in emotional symptoms, as demonstrated in multiple randomized controlled trials of early palliative care interventions in advanced cancer (53, 54) and heart failure (55). Interventions that incorporate training in coping skills, whether by telehealth or through cardiopulmonary rehabilitation, improve QOL and change the coping styles of patients from negative and avoidant to positive and active (56). To be effective, active coping strategies need to be taught to patients earlier in the disease trajectory, as the losses experienced with end-stage disease make it difficult to teach these active coping strategies (52). Furthermore, coping with COPD is an important factor in QOL for patient–family caregiver dyads (57). As this theme was also expressed universally in family caregiver participants in our cohort, we recommend that early palliative care interventions incorporate instruction for family caregivers on how to cope while caring for a loved one with COPD.

Themes on emotional symptoms and respiratory symptoms were the next most frequently discussed themes on early palliative care. The frequency of emotional symptoms and their impact on clinical outcomes in COPD have been well demonstrated (58); however, management of these symptoms in COPD remains controversial. Palliative care specialists may be ideally suited to help manage clinical emotional distress, especially in those with anxiety precipitated by dyspnea. In fact, it has been suggested that severe dyspnea may be an ideal trigger for referral to early palliative care (3). Although pulmonary specialists routinely manage severe dyspnea, referral to specialist palliative care or advanced primary palliative care training for pulmonologists can help to manage the bidirectional relationship between emotional and respiratory symptoms and to reinforce the often neglected cardiopulmonary rehabilitation (59).

The remaining themes on early palliative care needs, illness understanding and prognostic awareness, were discussed by more patients with GOLD IV stage COPD and their family caregivers compared with GOLD II–III stages. Although it may seem that patients with more advanced disease should have a better understanding of illness, our findings instead suggest that illness understanding is something patients with COPD and family caregivers continue to wrestle with as the disease progresses. Prognostic awareness relates closely to illness understanding and similarly involves an on-going process that requires sensitive and skillful clinician training while maintaining hope. Addressing these topics earlier in the disease could have a strong QOL impact (42).

Our study is limited by its small sample size and single-center design, though this is consistent with the purpose of our formative evaluation and intervention development (27). We interviewed a racially diverse sample of patients and their family caregivers, a first in the literature. Furthermore, we include qualitative data on the COPD experience in patients and their family caregivers across GOLD stages typically not included in palliative care trials in COPD. This is unique and provides insight into the unmet early palliative care needs that exist for this population. We recognize that our inclusion criteria requiring the presence of a family caregiver excluded the perspectives of patients without family caregivers who may have unique social support needs. This leaves room for further exploration of early palliative care needs in this particularly vulnerable population of patients with COPD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have identified five high-priority early palliative care needs in COPD: coping with COPD; emotional symptoms; respiratory symptoms; illness understanding; and prognostic awareness. Our data provide support for expanding the reach of early palliative care to patients with moderate to very severe COPD and their family caregivers. Future studies investigating needs-based referral using QOL and symptom surveys are warranted. With emphasis placed on coping with COPD and emotional symptoms, the five broad themes informed the development of an early palliative care intervention for patients with COPD and their family caregivers across disease severity, which was subsequently tested for feasibility.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant K12HS023009 and University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Center for Palliative and Supportive Care Palliative Research Enhancement Project (PREP) Pilot Award; A.S.I. is supported by a UAB Patient Centered Outcomes Research K12 grant K12HS023009 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by a PREP pilot award from the UAB Center for Palliative and Supportive Care; J.N.D.-O. is funded by National Institute of Nursing Research grant R00NR015903; C.J.B. is supported by a Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation R&D Scientific Merit Award; M.T.D. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1K24HL140108, the Department of Defense, American Lung Association, contracted clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, PneumRx/BTG, and Pulmonx, and reports consulting from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Mereo, PneumRx/BTG, and Quark; M.A.B. is supported by grants bNR013665-01A1, NR011871-01, PCORI PLC-1609-36381, PLC-1609-36714.

Author Contributions: A.S.I. and M.A.B. take full responsibility for the study as a whole, including conception and design, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; J.N.D.-O. and N.V.I. contributed to study conception, study design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation; S.M.F., S.L.C.T., E.D.S., C.J.B., R.O.T., and M.T.D. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E.Mortality in the United States, 2016 NCHS Data Brief.Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroedl CJ, Yount SE, Szmuilowicz E, Hutchison PJ, Rosenberg SR, Kalhan R. A qualitative study of unmet healthcare needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a potential role for specialist palliative care? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1433–1438. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-155BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maddocks M, Lovell N, Booth S, Man WD, Higginson IJ. Palliative care and management of troublesome symptoms for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2017;390:988–1002. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wysham NG, Cox CE, Wolf SP, Kamal AH. Symptom burden of chronic lung disease compared with lung cancer at time of referral for palliative care consultation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1294–1301. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-180OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beernaert K, Cohen J, Deliens L, Devroey D, Vanthomme K, Pardon K, et al. Referral to palliative care in COPD and other chronic diseases: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2013;107:1731–1739. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, McDermid RC, Celi LA. Use of Palliative Care in Patients With End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States Chest 2017151141–46.doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gershon AS, Maclagan LC, Luo J, et al. End-of-life strategies among patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J. Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(11):1389–1396. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0592OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton R, Rocker G, Dale A, Young J, Hernandez P, Sinuff T. Implementing a palliative care trial in advanced COPD: a feasibility assessment (the COPD IMPACT study) J Palliat Med. 2013;16:67–73. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakitas MA. On the road less traveled: journey of an oncology palliative care researcher. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:87–95. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, Meier DE.National Consensus Project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines4th ed. J Palliat Med [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siouta N, van Beek K, Preston N, Hasselaar J, Hughes S, Payne S, et al. Towards integration of palliative care in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review of European guidelines and pathways. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:18. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayle C, Coventry PA, Gomm S, Caress AL. Understanding the experience of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who access specialist palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2013;27:861–868. doi: 10.1177/0269216313486719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheerens C, Deliens L, Van Belle S, Joos G, Pype P, Chambaere K. “A palliative end-stage COPD patient does not exist”: a qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators for early integration of palliative home care for end-stage COPD. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2018;28:23. doi: 10.1038/s41533-018-0091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strang S, Osmanovic M, Hallberg C, Strang P. Family caregivers’ heavy and overloaded burden in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1768–1772. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansfield E, Bryant J, Regan T, Waller A, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher R. Burden and unmet needs of caregivers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a systematic review of the volume and focus of research output. COPD. 2016;13:662–667. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2016.1151488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, Ceronsky L, Clifford KN, Dionne-Odom JN, et al. Systematic review of palliative care in the rural setting. Cancer Contr. 2015;22:450–464. doi: 10.1177/107327481502200411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, Jackson L, Ellis D, Ahmed A, et al. Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:995–1004. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivankova N. V. Applying mixed methods in community-based participatory action research: a framework for engaging stakeholders with research as a means for promoting patient-centredness. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2017;22(4):282–294. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A.Foundation of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20:169–177. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199704)20:2<169::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1700214. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00214-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelley AS, Covinsky KE, Gorges RJ, McKendrick K, Bollens-Lund E, Morrison RS, et al. Identifying older adults with serious illness: a critical step toward improving the value of health care. Health Serv Res. 2017;52:113–131. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dionne-Odom JN, Taylor R, Rocque G, Chambless C, Ramsey T, Azuero A, et al. Adapting an early palliative care intervention to family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer in the rural Deep South: a qualitative formative evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1519–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center to Advance Palliative Care 2011 Public Opinion Research on Palliative Care 2011 June 1. accessed 2019 January 16]. Available from: https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/2011-public-opinion-research-palliative-care

- 29.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin DE, Atwood CA, Jr, Hays RD, Spritzer K, Liu H, Donohue JF, et al. Correlation of PROMIS scales and clinical measures among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with and without exacerbations. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:999–1009. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0818-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11:304–314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broderick JE, DeWitt EM, Rothrock N, Crane PK, Forrest CB. Advances in patient-reported outcomes: the NIH PROMIS(®) measures. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2013;1:1015. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds N, Johnston KL, Yount S, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. PROMIS Cooperative Group. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Thompson WW, Cella D. U.S. general population estimate for “excellent” to “poor” self-rated health item. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1511–1516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3290-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilford J, Osann K, Hsieh S, Monk B, Nelson E, Wenzel L. Validation of PROMIS emotional distress short form scales for cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi SW, Schalet B, Cook KF, Cella D. Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: linking the BDI–II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychol Assess. 2014;26:513–527. doi: 10.1037/a0035768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allman R, Sawyer P, Roseman J. The UAB Study of Aging: background and insights into life-space mobility among older Americans in rural and urban settings. Aging Health. 2002;2:417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iyer AS, Wells JM, Bhatt SP, Kirkpatrick DP, Sawyer P, Brown CJ, et al. Life-space mobility and clinical outcomes in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2731–2738. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S170887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akyar I, Dionne-Odom JN, Bakitas MA. Using patients and their caregivers feedback to develop ENABLE CHF-PC: an early palliative care intervention for advanced heart failure. J Palliat Care. 2019;34:103–110. doi: 10.1177/0825859718785231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Back AL. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: a communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:894–900. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgio KL, Williams BR, Dionne-Odom JN, Redden DT, Noh H, Goode PS, et al. Racial differences in processes of care at end of life in VA medical centers: planned secondary analysis of data from the beacon trial. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:157–163. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, Von Roenn JH, Szmuilowicz E, Prigerson HG, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3802–3808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boland J, Martin J, Wells AU, Ross JR. Palliative care for people with non-malignant lung disease: summary of current evidence and future direction. Palliat Med. 2013;27:811–816. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozlov E, McDarby M, Reid MC, Carpenter BD. Knowledge of palliative care among community-dwelling adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:647–651. doi: 10.1177/1049909117725725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, Shen MJ, Adelman RD, Reid MC. Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: a population-based survey study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35:431–439. doi: 10.1177/1049909117715215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brien SB, Lewith GT, Thomas M. Patient coping strategies in COPD across disease severity and quality of life: a qualitative study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16051. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoilkova A, Wouters EF, Spruit MA, Franssen FM, Janssen DJ. The relationship between coping styles and clinical outcomes in patients with COPD entering pulmonary rehabilitation. COPD. 2013;10:316–323. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.744389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobs JM, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. The positive effects of early integrated palliative care on patient coping strategies, quality of life, and depression. Presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium. October 28, 2017, San Diego, CA. Abstract 92, p. 92.

- 53.Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, Dahlin C, Block SD, Buss MK, et al. Phase II study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non–small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2377–2382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Barnett KN, Brokaw FC, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:75–86. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: the PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blumenthal JA, Emery CF, Smith PJ, Keefe FJ, Welty-Wolf K, Mabe S, et al. The effects of a telehealth coping skills intervention on outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: primary results from the INSPIRE-II study. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:581–592. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meier C, Bodenmann G, Mörgeli H, Jenewein J. Dyadic coping, quality of life, and psychological distress among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and their partners. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:583–596. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S24508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iyer AS, Holm KE, Bhatt SP, Kim V, Kinney GL, Wamboldt FS, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Symptoms of anxiety and depression and use of anxiolytic-hypnotics and antidepressants in current and former smokers with and without COPD—a cross sectional analysis of the COPDGene cohort. J Psychosom Res. 2019;118:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maddocks M, Reilly CC, Jolley C, Higginson IJ. What next in refractory breathlessness? Research questions for palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2014;30:271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.