Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are induced by and accumulate within many histologically distinct solid tumors, where they promote disease by secreting angiogenic and immunosuppressive molecules. Although IL1β can drive the generation, accumulation, and functional capacity of MDSCs, the specific IL1β-induced inflammatory mediators contributing to these activities remain incompletely defined. Here, we identified IL1β-induced molecules that expand, mobilize, and modulate the accumulation and angiogenic and immunosuppressive potencies of polymorphonuclear (PMN)-MDSCs. Unlike parental CT26 tumors, which recruited primarily monocytic (M)-MDSCs by constitutively expressing GM-CSF- and CCR2-directed chemokines, IL1β-transfected CT26 produced higher G-CSF, multiple CXC chemokines, and vascular adhesion molecules required for mediating infiltration of PMN-MDSCs with increased angiogenic and immunosuppressive properties. Conversely, CT26 tumors transfected with IL1β-inducible molecules could mobilize PMN-MDSCs, but because they lacked the ability to upregulate IL1β-inducible CXCR2-directed chemokines or vascular adhesion molecules, the PMN-MDSCs could not infiltrate tumors. IL1β-expressing CT26 increased angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs, as did CT26 tumors individually transfected with G-CSF, Bv8, CXCL1, or CXCL5, demonstrating that mediators downstream of IL1β could also modulate MDSC functional activity. Translational relevance was indicated by the finding that the same growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules responsible for the mobilization and recruitment of PMN-MDSCs into inflammatory CT26 murine tumors were also coordinately upregulated with increasing IL1β expression in human renal cell carcinoma tumors. These studies demonstrated that IL1β stimulated the components of a multifaceted inflammatory program that produces, mobilizes, chemoattracts, activates, and mediates the infiltration of PMN-MDSCs into inflammatory tumors to promote tumor progression.

Keywords: Tumor microenvironment, MDSCs, IL1β, inflammation, immunosuppression, angiogenesis

INTRODUCTION

Chronic inflammation is now causally linked with the development and progression of cancer (1–4). Many human tumors produce cytokines, growth factors, angiogenic stimuli, oxidative products, and metalloproteases that collectively enhance tumor proliferation, progression, and invasion (5). Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogeneous group of immature myeloid cells that are both angiogenic and immunosuppressive and result from and exacerbate inflammatory conditions that augment tumor growth (6). MDSCs are overproduced in the bone marrow of tumor-bearing mice, and their numbers are elevated in the peripheral blood and tumors of both experimental animals and human cancer patients (6–8). In mice and humans, at least two identifiable subpopulations of MDSCs exist, distinguished by markers characteristic of monocytes (monocytic (M)-MDSCs) or neutrophilic granulocytes (polymorphonuclear (PMN)-MDSCs)(6,9,10).

The phenotypic and functional characteristics of MDSC subpopulations elicited to a tumor could profoundly impact the mechanism by which tumor progression is enhanced. M-MDSCs are often deemed the more immunosuppressive subpopulation, and have been reported to more effectively inhibit T-cell IFNγ production and proliferation than PMN-MDSCs (10–12), reflecting their elevated production of arginase 1, IDO, TGFβ, iNOS, and IL10. PMN-MDSCs are widely considered the more angiogenic subpopulation, with their tumor promoting activity largely ascribed to an abundant synthesis of matrix metalloproteases, VEGF, S100A8/A9 proteins, and Bv8 (12,13). However, although the molecules involved in producing M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs in the bone marrow are fairly well established (14), the determinants regulating the type of MDSCs that infiltrate tumors remain poorly defined. Although it is believed that the molecular components of the tumor microenvironment (TME) might modulate the immunosuppressive and angiogenic activities of infiltrating MDSCs (15), the stimuli mediating those effects and the extent of their impact have not yet been characterized.

In the experiments described below, the magnitude of the IL1β inflammatory signal within a tumor was shown to govern the balance of CD11b+Ly6C+ and CD11b+Ly6G+ cells produced in the bone marrow, as well as their recruitment into the TME. We found that IL1β-inducible molecules, such as G-CSF and Bv8, could induce a significant expansion and mobilization of circulating CD11b+Ly6G+ cells but were unable to promote PMN-MDSC tumor infiltration above that detected in non-inflammatory tumors due to the lack of IL1β-induced specific chemokines and adhesion molecules. We also found that these downstream mediators directly contributed to the functional status of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs. The translational relevance of these studies was supported by the finding that human renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) also produced inflammatory molecules associated with PMN-MDSC generation and intratumoral accumulation in direct proportion to increasing IL1β expression, with the PMN-MDSC chemokine CXCL1 statistically associated with survival for the patients in our cohort and the TCGA RCC patient cohort. In summary, our results showed that IL1β was capable of inducing all mediators required for the elicitation, mobilization, recruitment, and activity of tumor-infiltrating PMN-MDSCs. This function likely represents an important mechanism by which IL1β promotes the growth and dissemination of tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Six to eight week-old female BALB/c and C57BL6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (JAX, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). BALB/c mice heterozygous for CXCR2 (CXCR2+/–) were also obtained from JAX (stock No 002724) and were crossed to generate knockout CXCR2−/− mice. The genotype of the mutant offspring was confirmed as described previously (16). Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which adheres to USDA guidelines. The animals were housed in filtertop microisolator cages in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room, using a standard mouse diet and water provided ad libitum.

Tumors

CT26 is an N-nitroso-N-methylurethane-(NNMU)–induced, undifferentiated murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line (17) and was acquired directly from ATCC. The 4T1 cell line was developed from a spontaneous Balb/c mammary carcinoma (18) and was also purchased from ATCC. The B16F10 melanoma cell line was purchased from ATCC, and D4M cells were a gift from Dr. Mary Jo Turk. CT26-IL1β, CT26-G-CSF, CT26-Bv8, CT26-CXCL1, CT26-CXCL5, and the B16F10IL1β (B16-IL1β) were generated by transfecting the corresponding parental cell line as described below. Cells were maintained at 37oC in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in RPMI medium supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 4 mM L-glutamine (Sigma), and 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals), and were tested and verified to be mycoplasma-free. The cells were kept in culture for no more than three passages before use.

Tumors were stablished by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 106 parental or transfected CT26 cells or 5 × 105 B16F10, B16-IL1β, or D4M cells into the flank of Balb/c or C57BL6 mice, respectively, in a total volume of 0.1 mL PBS. Tumor volumes were measured on alternate days with a micrometer in two dimensions, and tumor size was estimated according to the formula: 0.5 * (shorter diameter)2 × (longer diameter).

Plasmids and transfection

A DNA molecule composed of the human IL1 receptor antagonist signal sequence fused to the coding region of the mature IL1β protein (19) was synthesized with flanking BamH1 sites and cloned into pcDNA3.1 by GENEWIZ. This construct was used to generate B16-IL1β and CT26-IL1β cell lines by stable transfection (using Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V, Amaxa) of parental B16F10 and CT26 cells.

Whole tumor RNA from CT26-IL1β tumors was extracted with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center) and used as a template to generate cDNA using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was amplified by PCR to generate coding regions for G-CSF, Bv8, CXCL1, or CXCL5 Each fragment was subsequently cloned into pcDNA3.1. Primer pairs used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For each cytokine, stable CT26 clones were generated as described above. Stable cell clones were selected with G418 and elevated levels of transfected factor was confirmed by ELISA.

Characterization of MDSCs in murine blood, bone marrow, spleen, and tumor

Tumor bearing mice were sacrificed when the tumors were approximately 400 mm3 in size. Blood was collected into EDTA Microtainer® Tubes (BD) following heart puncture. Blood cell counts were determined using the Advia 120 Hematology Analyzer (Siemens). Bone marrow (BM) cells flushed from femora and tibiae were depleted of RBCs with ACK lysis buffer (Gibco). Spleen cell suspensions were generated by gentle mashing followed by RBC depletion with ACK lysis buffer according to well-established procedures (20,21). Parental or transfected CT26, 4T1, B16F10, or D4M tumors were weighed and subsequently digested using the Mouse Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) on the gentleMACS Octo Dissociator with C-tubes according to manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). Single-cell suspensions of the bone marrow, spleen, and tumors were filtered using 70-μm cell strainers (BD Falcon) and counted. One million cells were stained with antibodies specific for Ly6G (clone 1A8, BD), Ly6C (clone ER-MP20, Bio-Rad), and CD11b (clone M1/70, eBioscience) before being acquired on a LSRFortessa (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo™ software. MDSCs from blood, bone marrow, spleen, and tumors were positively selected by cell sorting using a Special-Order FACSAria II (BD) after staining with Ly6G (clone 1A8, BD), and CD11b (clone M1/70, eBioscience). M-MDSCs were identified as CD11b+Ly6G–, and PMN-MDSCs were identified as CD11b+Ly6G+. Ten million CD11b+Ly6C+ Ly6G– cells from the bone marrow of CT26-IL1β mice bearing tumors of approximately 400 mm3 were labelled with 5 μM CFSE (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C for 10 minutes and immediately washed with ice-cold PBS containing 5% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals). After staining, 1×106 cells were injected i.v. via tail vein into a second set of mice bearing 400 mm3 CT26-IL1β tumors. Four days after transfer mice were euthanized and tumor suspensions were prepared as described above. Tumor infiltrating CFSE+ cells were assayed by flow cytometry using a LSRFortessa (BD) and analyzed using FlowJo™ software after staining with antibodies specific for Ly6G (clone 1A8, BD), Ly6C (clone ER-MP20, Bio-Rad), and CD11b (clone M1/70, eBioscience).

T-cell suppression assays

CD11b+Ly6G+ cells sorted from cell suspensions of CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumors, described above, were cocultured with T cells isolated from spleens using the MojoSort Mouse CD3 T-Cell Isolation Kit (BioLegend) at a 2:1 or 4:1 T cell to MDSC ratio. T cells were activated using Dynabeads™ Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Gibco) and IL2 (25 U/mL; Peprotech). On day 6 of culture, cells were treated with Golgi Plug (BD) 4 hours before staining with anti-CD8a antibody (Clone 53–6.7, BioLegend). After staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer (BD) and incubated with anti-IFNγ antibody (Clone XMG1.2, Invitrogen). IFNγ unconjugated antibody (Clone XMG1.2 Invitrogen) was used as a blocking control. Cells were acquired using a LSRFortessa (BD) and CD8+IFNγ+ cells were analyzed with FlowJo software. Results are expressed as percent suppression, which was calculated as the decrease in the frequency of CD8+IFNγ+ cells.

Human tumors

Twenty-six primary RCC tumor samples and 2 oncoytoma samples used as controls were collected after nephrectomy. All human tissue was obtained at the Cleveland Clinic under a protocol approved by the institutional review board (IRB) with written informed consent obtained from each patient. Patient studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report.

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (22). Tissues were snap-frozen in isopentane pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen until sectioned. Frozen tissue sections (6 μm) were prepared, fixed in cold reagent grade acetone for 10 minutes, and air dried. After blocking with 10% BSA (Sigma), slides were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of Alexa-fluor 488-conjugated Armenian hamster anti-human IL1β monoclonal IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), washed, and visualized by confocal microscopy. RNA was purified from each sample as described below.

Gene expression analysis

For comparative gene expression studies, quantitative RT-PCR analysis was conducted. Briefly, RNA was extracted from whole tumor or sorted MDSCs using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center). One microgram of RNA was used to generate cDNA with the TaqMan Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gene expression levels were normalized to β−2-Microglobulin and used to calculate relative expression using the 2-ΔCt formula. Primer pairs used in the quantitative PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Transcriptomic analysis of MDSC populations sorted from B16F10, B16-IL1B, and D4M tumors was performed using the nCounter Mouse Myeloid Innate Immunity Panel (Nanostring Technologies.) RNA was isolated as described above and probes annealed at 65 °C overnight. Samples were subsequently processed in the fully automated nCounter Prep-station and analyzed in the nCounter Digital Analyzer (NanoString Technologies.) The nSolver 3 software was used for data normalization and differential gene expression analyses. An agglomerative cluster heat map analysis was performed using normalized data. Clustering parameters included z-Score transformation of genes calculated under the Euclidian distance metric and centroid linkage method.

TCGA analysis

TCGA data was accessed and analyzed using the UCSC Xena platform (23). The GDC TCGA Kidney Clear Cell Carcinoma (KIRC) data base was used. Analysis included 604 samples from patients with a confirmed diagnosis of renal clear cell carcinoma. Samples lacking survival data were excluded. HTSeq counts specific for CXCL1 were obtained and association with survival was determined by Kaplan Meier Survival Analyses using the Xena Genomics Explorer software. P values were calculated using the log-rank test.

Statistical analyses

P values were calculated using Student’s t test (Graphpad Prism) and a significant difference among experimental groups was defined as a p<0.05. Overall survival was calculated using a Kaplan- Meier curve and p-value was determined by log-rank test using R version 3.4 (R Foundation).

RESULTS

IL1β drives the expansion, mobilization, and accumulation of PMN-MDSCs within tumors

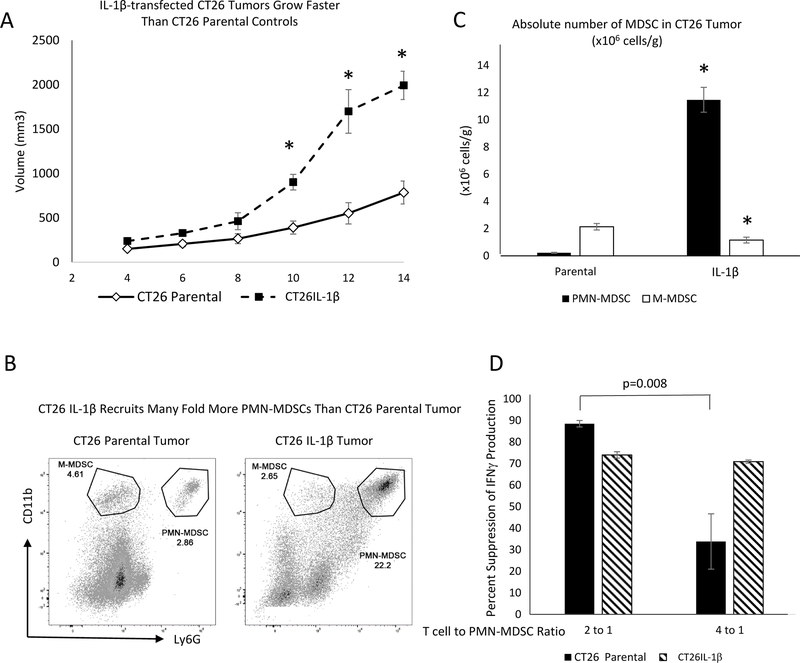

IL1β has been demonstrated in multiple settings to stimulate a broad spectrum of inflammatory activities that collectively promote tumor progression (1,2). Our objective was to determine the changes that were induced by IL1β, and to assess which were responsible for promoting the expansion and accumulation of MDSCs within tumor sites and the modulation of their tumor-promoting function. We examined mice bearing either parental CT26 tumors (CT26 parental) or CT26 tumors engineered to express elevated IL1β (CT26-IL1β). Fourteen days following implantation, the CT26-IL1β tumors were 3-fold larger than the parental tumors (Figure 1A), and H&E staining revealed that the modified tumors were more heavily infiltrated by small, polymorphonuclear granulocytic cells (Supplementary Figure S1), which were demonstrated to be CD11b+Ly6G+ PMN-MDSCs via flow cytometry (Figure 1B). However, in contrast to the 50-fold greater influx of PMN-MDSCs into CT26-IL1β compared to CT26 parental tumors, CT26-IL1β tumors were infiltrated by 50% fewer M-MDSCs than the parental tumors. Analysis also showed that both CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumors contained CD11b+Ly6C+LY6G– M-MDSCs (Figure 1C). On average, the parental tumors contained 9-times more M-MDSCs than PMN-MDSCs, and the CT26-IL1β tumors had nearly 10-times more PMN-MDSCs than M-MDSCs (Figure 1C). The suppressive activity of T-cell function by PMN-MDSCs infiltrating CT26-IL1β tumors was enhanced compared to that of PMN-MDSCs infiltrating CT26 parental tumors. The data indicated that although PMN-MDSCs from IL1β-expressing tumors were equally suppressive at 4:1 and 2:1 ratios of T cells:MDSCs, the PMN-MDSCs from parental tumors were 60% less suppressive at the 4:1 ratio (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Enhanced progression of IL1β-expressing CT26 tumors associates with increased recruitment of PMN-MDSCs.

A. Balb/c mice (n=5) were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 parental or IL1β-transfected CT26 tumor cells, and were monitored every two days for primary tumor growth. B. Parental and IL-1β-expressing CT26 tumors were harvested and digested into single-cell suspensions and counted. The frequency of PMN-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G+) and M-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G–) from all viable cells was determined by flow cytometry. C. Absolute numbers of infiltrating PMN-MDSCs or M-MDSCs, graphed as millions of cells/gram (g) tumor tissue, were calculated based on the total tumor cellularity. D. Suppressive activity of PMN-MDSCs infiltrating CT26 parental or CT26-IL1β tumors was measured. Percent reduction of CD8+IFNγ+ T cells frequency, as assessed by flow cytometry, after T cells were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads + IL2 (25 U/mL) at the indicated T cell:PMN-MDSC ratios. Data are expressed as the average of at least five measurements ±SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s t test. Statistically significant differences (P< 0.05 or otherwise indicated) are indicated by an asterisk. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

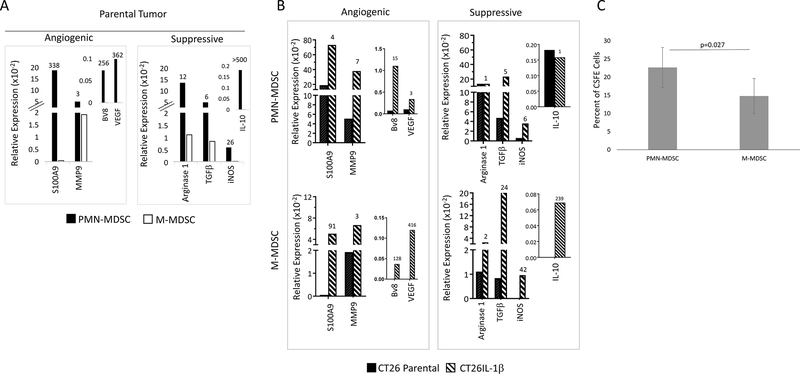

IL1β-induced PMN-MDSCs are more angiogenic and immunosuppressive than M-MDSCs

IL1β also stimulates both M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs to express mRNAs that encode angiogenic and immunosuppressive molecules. CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumors were digested into single-cell suspensions, and purified pools of M- and PMN-MDSCs were obtained by sorting. RNA was isolated from each subpopulation, and the relative expression of angiogenic and immunosuppressive mRNAs was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. The PMN-MDSC subpopulation had significantly higher expression of three of the four angiogenic molecules evaluated (S100A9, Bv8, and VEGF; only 3-fold more MMP9) and significantly higher expression of the immunosuppressive molecules (arginase 1, TGFβ, iNOS, IL10) compared to the M-MDSC subpopulation from the same CT26 parental tumors (Figure 2A). However, both the M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs from CT26-IL1β tumors had higher expression of these mRNAs compared to the MDSC populations isolated from CT26 parental tumors (Figure 2B). The PMN-MDSCs from the CT26 parental tumors had high expression of tumor promoting mRNAs, which were only modestly elevated in PMN-MDSCs from CT26-IL1β tumors, although the effect of IL1β exposure on the M-MDSC population was much more pronounced (Figure 2B). These results collectively indicated that the effect of IL1β on the MDSC contribution to tumor progression was multi-factorial – IL1β significantly increases the intratumoral numbers of the more potent PMN-MDSCs, but also substantially enhances the expression of tumor-promoting immunosuppressive and angiogenic activities by both the M- and PMN-MDSCs. It is suggested that recruited M-MDSCs could potentially be converted into PMN-MDSCs within the inflammatory tumor bed (24). Indeed, when CFSE-labelled bone marrow–derived CD11b+Ly6G–Ly6C+ cells were injected intravenously into mice bearing CT26-IL1β tumors, the CSFE-labelled population recovered from the tumor four days later was largely CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C-, supporting the possibility that the IL1β-containing tumor microenvironment could promote this conversion (Figure 2C). Thus, another effect of IL1β may be to promote a process by which M-MDSCs differentiate into PMN-MDSCs.

Figure 2. PMN-MDSCs isolated from CT26 parental tumors have higher expression of angiogenic and immunosuppressive molecules than the M-MDSCs.

PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs were sorted from 400 mm3 parental or IL1β-transfected CT26 tumors (n=8) based on expression of CD11b and Ly6G. The RNA prepared from each population was used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis to assess relative expression of angiogenic and immunosuppressive molecules, as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers on top of each bar indicate the following: A. fold increase expression by PMN-MDSCs compared to M-MDSCs when both populations were isolated from parental CT26 tumors, and B. fold increase expression by PMN-MDSCs or M-MDSCs isolated from CT26-IL1β tumors compared to those same populations isolated from parental CT26 tumors. Genes assessed are indicated. C. CD11b+Ly6C+ Ly6G– cells from the bone marrow of CT26-IL1β tumor-bearing mice were labeled with CFSE before being adoptively transferred into a second set of CT26-IL1β tumor-bearing mice (n=5). Four days later tumors were harvested and levels of infiltrating CFSE-labeled M- (CD11b+Ly6G–) and PMN-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G+) were determined. Data are shown as the average of 5 measurements ±SEM, and is representative of two independent experiments. P value was calculated using Student’s t test.

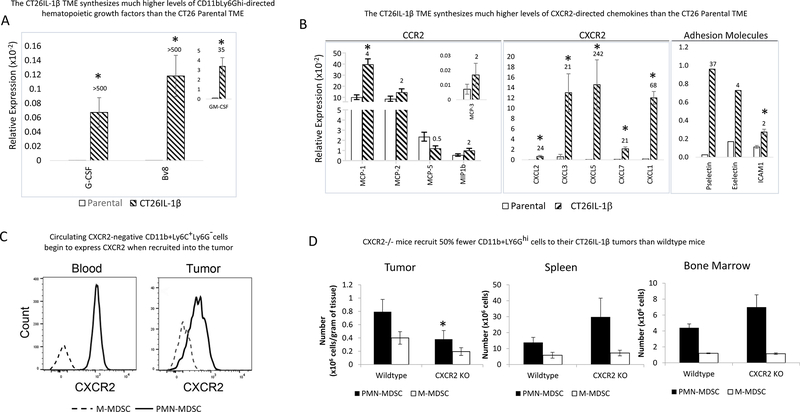

IL1β induces all mediators needed for intratumoral accumulation of PMN-MDSCs

Given our observation that IL1β promoted the accumulation of PMN-MDSCs within the tumor, we next asked what gene products downstream of IL1β were involved in the process. To answer this question, we prepared RNA from 14-day CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumors and performed quantitative RT-PCR using validated primer pairs specific for mRNAs encoding growth factors, adhesion molecules, and chemokines. These studies, repeated more than a dozen times, consistently demonstrated that CT26-IL1β tumors synthesized significantly greater expression of mRNAs encoding PMN-targeting growth factors (G-CSF and Bv8) than CT26 parental tumors (Figure 3A). GM-CSF and the CCR2-directed chemokines MCP-1, MCP-2, and MCP-5 were constitutively expressed in parental tumors and were not significantly elevated in CT26-IL1β tumors (Figure 3B), consistent with the limited impact of IL1β on tumor infiltration by M-MDSCs. This is in contrast to the expression of mRNAs encoding chemokines that promote PMN-MDSC chemotaxis through CXCR2 (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL7), which had significantly higher expression in CT26-IL1β tumors than CT26 parental tumors (20- to >200-fold) (Figure 3B). This, in part, explains their augmented recruitment of circulating PMN-MDSCs, >95% of which expressed CXCR2 in mice bearing CT26-IL1β tumors (Figure 3C). By comparison, circulating CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G– cells were essentially all CXCR2-negative, although they did begin to express CXCR2 following infiltration into CT26-IL1β tumors, which could reflect an early stage of M-MDSC to PMN-MDSC conversion (Figure 3C). The role for CXCR2 and the cognate chemokines in promoting increased PMN-MDSC recruitment was further demonstrated by our finding that CT26-IL1β tumors grew more slowly and were infiltrated by 50% fewer PMN-MDSCs when injected into CXCR2–/– mice, with corresponding increases in PMN-MDSC numbers observed in the bone marrow and spleen (Figure 3D). In addition to growth factors and chemoattractants, CT26-IL1β tumors also had higher expression of mRNAs encoding endothelial adhesion molecules, including E-selectin, P-selectin, and ICAM-1 (Figure 3B), which allow for the attachment of recruited cells to the tumor vasculature as an initial step of extravasation.

Figure 3. CT26-IL1β tumors express higher levels of growth factors, chemokines, and adhesion molecules involved in the accumulation of PMN-MDSC via their CXCR2 chemokine receptors.

RNA was prepared from whole, CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumors (n=3) and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis to assess their relative expression of growth factors, chemokines, and adhesion molecules involved in the accumulation of PMN-MDSCs, as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers on top of each bar indicate fold increased expression by CT26-IL1β tumors compared to parental CT26 tumors of A. hematopoietic growth factors or B. CCR2- and CXCR2-directed chemokines and adhesion molecules. C. Representative plots showing the frequency of CXCR2 expression by M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs in both blood and IL1β-expressing tumors. Data are expressed as the average relative expression ±SEM. D. Tumors, spleens, and bone marrow from wild-type and CXCR2 knock out mice (n=5) were processed into single-cell suspensions, and total cellularity was quantified. Frequency of PMN-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G+) and M-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G–) were determined by flow cytometry, and absolute numbers were calculated based on the total cellularity. Data are expressed as the average number of PMN-MDSCs or M-MDSCs per gram of tissue of at least five measurements ±SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s t test. Statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

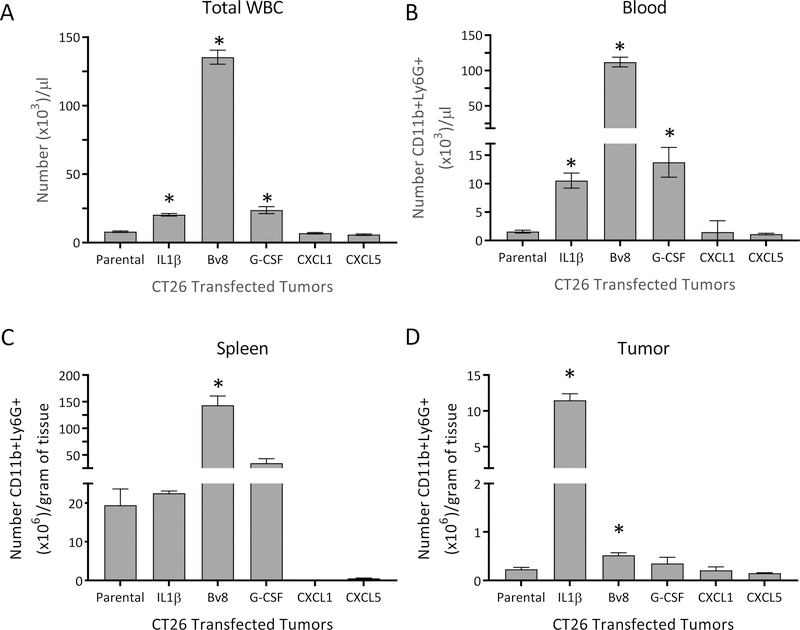

G-CSF and Bv8 expand and mobilize PMN-MDSCs but are unable to recruit them to tumors

To determine the specific roles for the growth factors and chemoattractants downstream of IL1β in the behavior of MDSC populations, we evaluated tumors engineered to express each of those factors independently (Supplementary Figure S2). Although mice bearing CT26-Bv8 tumors developed severe leukocytosis, having 16-fold more circulating total white blood cells (WBCs), 71-fold more circulating CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, and 7-fold more splenic CD11b+Ly6G+ cells than mice bearing CT26 parental tumors, the tumors were infiltrated by only 2.3-fold more PMN-MDSCs than the CT26 parental tumors (Figure 4). Likewise, mice bearing CT26–G-CSF tumors had approximately 3-fold more circulating WBCs, and almost 13-fold more peripheral blood CD11b+Ly6G+ cells than animals harboring CT26 parental tumors, and the CT26–G-CSF tumors were infiltrated by only 1.5-fold more PMN-MDSCs than the CT26 parental tumors (Figure 4). By comparison, mice bearing CT26-IL1β tumors had only 2.5-fold more circulating WBCs, 6.7-fold more circulating CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, and essentially equal numbers of splenic CD11b+Ly6G+ cells as mice carrying parental tumors. However, these inflammatory tumors were infiltrated up to 50-times more PMN-MDSCs than CT26 parental tumors (Figure 4). Tumors engineered to express CXCR2-directed chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL5) did not exhibit altered numbers of peripheral WBCs, circulating CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, or intratumoral PMN-MDSCs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relative ability of CT26 tumors overexpressing IL1β, Bv8, G-CSF, CXCL1, or CXCL5 to mobilize and/or recruit PMN-MDSCs.

Parental CT26 tumor cells were stably transfected or not with expression vectors encoding IL1β, Bv8, G-CSF, CXCL1, or CXCL5 and were each injected into mice (n=5). When the tumors were approximately 400 mm3 in size, the mice were assessed for A. numbers of total white blood cells (WBCs), B. their numbers of circulating or C. splenic CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, and D. the capacity of each individually-expressed cytokine or chemokine to recruit intratumoral PMN-MDSCs. Data are expressed as the average of five different measurements ±SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s t test. Statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

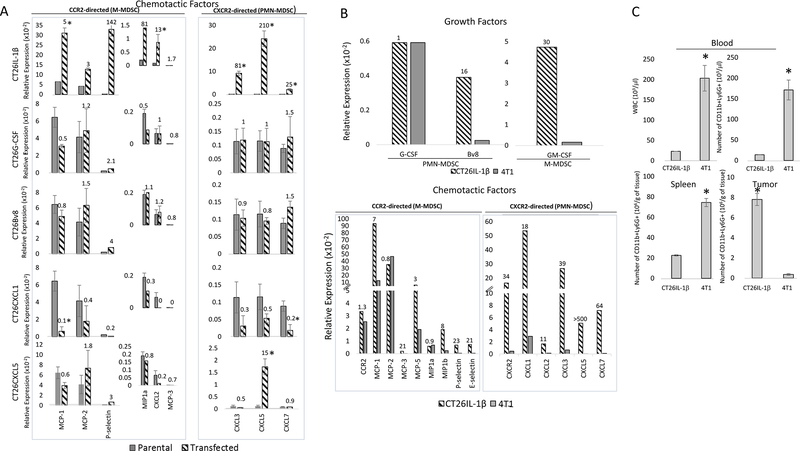

To better understand the discrepancy between PMN-MDSCs in circulation versus those within the tumor, we measured the expression of molecules involved in the elicitation and homing of M-MDSCs or PMN-MDSCs. We found that compared to CT26-IL1β, which expressed all the necessary molecules for PMN-MDSC elicitation and accumulation, tumors engineered to overexpress only G-CSF, Bv8, CXCL1, or CXCL5 did not exhibit elevation of the other factors required for effective PMN-MDSC infiltration into tumors, such as CXCR2-directed chemokines or P-selectin. Similarly, CT26 tumors engineered to overexpress CXCL1 or CXCL5 did not produce G-CSF, Bv8 (Supplementary Figure S3), or P-selectin, which are also required for PMN-MDSC elicitation and homing (Figure 5A). This could explain the low levels of PMN-MDSCs in both the circulation and within the tumors overexpressing individual factors (Figure 4). These results were supported by parallel studies using a 4T1 breast cancer model, which exhibits naturally elevated G-CSF expression but comparatively low expression of all the other mediators involved in MDSC elicitation and recruitment (Figure 5B). 4T1 tumors were found to have 10-fold more circulating total WBCs, 11-fold more circulating Ly6G+CD11b+ cells, and 3.3-fold more splenic CD11b+Ly6G+ cells than mice bearing CT26-IL1β tumors. Despite of elevated levels in circulation, 4T1 tumors had 21.6-fold fewer infiltrating PMN-MDSCs per gram of tissue than CT26-IL1β tumors (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Only CT26-IL1β tumors synthesize all the factors required for the enhanced elicitation, mobilization and infiltration of PMN-MDSC.

RNA was prepared from whole, 400 mm3 CT26 parental tumors, 4T1 tumors, and comparably sized tumors engineered to express IL1β, G-CSF, Bv8, CXCL1, or CXCL5 (n=8). The RNA prepared from each tumor was used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis to assess relative expression of the indicated mediators as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers on top of each bar indicate fold increased expression of: A. the indicated chemotactic factor by the transfected tumor compared to its parental counterpart or B. growth factors, chemotactic factors, and adhesion molecules by CT26-IL1β tumors compared to 4T1 tumors. C. CT26-IL1β or 4T1 tumors were analyzed for their numbers of WBCs and PMN-MDSCs per μL of blood, as well as their numbers of splenic and tumor-infiltrating PMN-MDSCs per gram of tissue, as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as the average of five different measurements ±SEM. P values were calculated using Student’s t test. Statistically significant differences (P< 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk. Data is representative of at least three independent experiments.

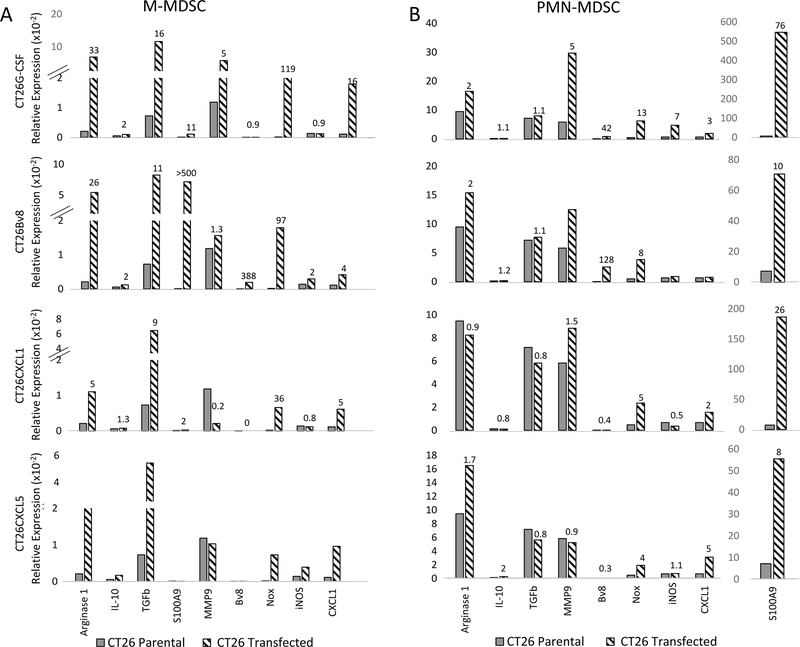

G-CSF, BV8, CXCL1, and CXCL5 induce angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors

Although tumors expressing elevated Bv8, G-CSF, CXCL1 or CXCL5 did not increase the number of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs, those that did infiltrate tumors exhibited elevated expression of angiogenic and immunosuppressive genes compared with the parental tumor MDSC counterparts. For example, compared to M-MDSCs isolated from CT26 parental tumors, the M-MDSCs purified from CT26–G-CSF tumors expressed more S100A9 (11-fold), TGFβ (16-fold), arginase 1 (33-fold), and Nox (119-fold)(Figure 6A). The G-CSF and/or Bv8 transgenes expressed by the transfected tumors induced increased expression of S100A9, Bv8, Nox, MMP9, and iNOS mRNAs in the tumor-infiltrating PMN-MDSCs, as well as the M-MDSCs. Although the inductions of Nox, S100A9, TGFβ, and, arginase 1 were significantly increased in the M-MDSCs, stimulated PMN-MDSCs expressed greater amounts of almost all of the molecules assessed (Figure 6). M-MDSCs infiltrating tumors transfected with CXCL1 and CXCL5 also showed increased levels of arginase 1 mRNA (5–10–fold), TGFβ (8-fold), and Nox (40-fold) compared to M-MDSCs isolated from CT26 parental tumors (Figure 6A). These data collectively demonstrated the ability of downstream inflammatory mediators to enhance the pro-tumor activity of MDSCs.

Figure 6. IL1β-induced factors, when individually transfected into CT26 parental tumors, stimulate the synthesis of angiogenic and/or immunosuppressive genes by infiltrating MDSCs.

RNA was prepared from pooled M-MDSCs or PMN-MDSCs isolated from CT26 tumors (n=8) that were transfected or not to stably overexpress G-CSF, Bv8, CXCL1, or CXCL5 and used for RT-PCR analysis to assess the relative expression of angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers on top of each bar indicate fold increased expression of the indicated immunosuppressive or angiogenic factor by A. M-MDSCs or B. PMN-MDSCs isolated from transfected tumors compared to the same cell populations isolated from its parental counterpart. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

To rule out the possibility that the effect of intratumoral accumulation of IL1β on tumor progression and the recruitment and function of MDSCs was limited to the CT26 model, we engineered B16F10 melanoma tumors to overexpress IL1β (B16-IL1β). Although we did not observe significant differences in tumor sizes, likely due to the fast growth of tumors, B16-IL1β tumors exhibited increased vascularization and fibroplasia, two hallmarks of tumor aggressiveness (25,26), compared with their parental counterpart (Supplementary Figure S4A). The overall MDSC content of B16-IL1β–overexpressing tumors was significantly increased compared to the corresponding parental tumor (Supplementary Figure S4B). In addition to augmenting the frequency of intratumoral MDSCs, IL1β enhanced their function, as evidenced by the increased expression of genes involved in immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic functions among sorted PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs (Supplementary Figure S4C)(27). We also analyzed D4M tumors, a mouse melanoma cell line that constitutively expresses high IL1β relative to B16F10. The accumulation of MDSCs and the pattern of inflammatory mediators expressed by D4M tumor-infiltrating PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs was similar to B16-IL1β tumors (Supplementary Figure S4B,D).

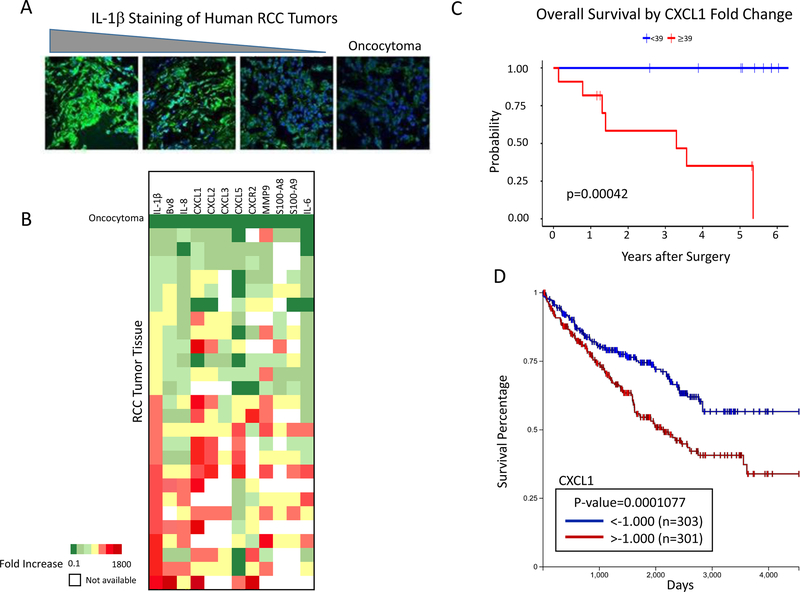

Mediators involved in PMN-MDSC accumulation in human RCCs are expressed in proportion to IL1β

When tumors from RCC patients were analyzed by immunofluorescence for IL1β expression, a wide range of staining intensities was observed (Figure 7A). Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine whether the growth factors, chemokines, and adhesion molecules associated with PMN-MDSC infiltration of IL1β-transfected murine tumors were also synthesized by RCC tissues at levels corresponding to IL1β production. A control non-malignant oncocytoma did not stain positive for IL1β (Figure 7A, right panel), and gene expression data generated from that tissue provided baseline gene expression. Unlike CT26-IL1β tumors that consistently expressed all of the CXCR2-directed, inducible chemokines at elevated levels (Figure 3B), RCC tumors exhibited variable expression of the CXCR2-directed chemokines, even in tumors with the highest IL1β expression (Figure 7B). Overall, however, the expression of IL1β-inducible mediators associated with the formation, recruitment, or functional activities of PMN-MDSCs (IL6, S100A9, MMP-9, Bv8, IL8, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL5, IL10, TGFβ, IDO) did generally rise coordinately with IL1β expression in tumors (Figure 7B). Although RCC tumors exhibited greater heterogeneity in terms of cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor expression, most of these components were elevated in the IL1β-expressing tumors, whereas, by comparison, the oncocytoma control showed consistently low expression of these factors (Figure 7B). Out of the 26 patients from whom we collected RCC tumor samples, we obtained survival data from 24 and found a correlation between tumor CXCL1 expression and worse survival (Figure 7C). These results were corroborated by analysis using TCGA, showing a statistically significant association between elevated CXCL1 and poor RCC patient survival (Figure 7D).

Figure 7: IL1β within human RCCs associates with the expression of factors that mediate the recruitment and function of MDSC and levels of CXCL1 correlate with survival.

A. Human RCC tumor sections were stained with anti-human IL1β using a non-malignant oncocytoma as a negative control. Triangle above indicates stain intensity. All images are shown at 40x magnification. B. Expression IL1β-inducible cytokines and chemokines involved in MDSC production, intratumoral accumulation, and functional activity. Twenty-six different RCC tumors are arranged vertically according to gradually increasing expression levels of IL1β. Gene expression is depicted as fold increase over oncocytoma tissue control. C. Survival analysis of RCC patients (excluding those without survival or expression data) based on the fold change of CXCL1 expression (<39 n=10, >39 n=11). D. Survival analysis of clear-cell carcinoma patients from TCGA based on the fold change of CXCL1 expression (n=604). Survival was calculated using Kaplan Meier analysis.

DISCUSSION

The ability of IL1β to promote the expansion, mobilization, and trafficking of MDSCs to tumors was described a decade ago (28–30), and although that apical inflammatory mediator is known to stimulate a broad and diverse spectrum of activities, precisely which downstream molecules contribute to the observed changes in MDSC behavior remain incompletely defined. A number of studies demonstrated that there are at least two MDSC subpopulations that develop in tumor-bearing mice: a monocytic subtype (M-MDSCs) that is recruited through its CCR2 chemokine receptor (31,32) and a granulocytic form (PMN-MDSCs) that expresses CXCR2 (33,34). Evidence suggests that IL1β can significantly enhance the numbers of circulating CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, although the molecular mediators and pathways involved in modulating the differential recruitment, intratumoral localization and protumoral activities of the monocytic and granulocytic MDSC subpopulations are poorly understood (28,34). We used CT26 parental and CT26-IL1β tumor cells to identify the IL1β-induced activities that drive these different effects, and to determine the scope of their individual contributions to IL1β-mediated tumor progression. The results demonstrated: 1) that IL1β expression within the TME was associated with significant increases in expression of growth factors (G-CSF, Bv8) that drive PMN-MDSC expansion, 2) that IL1β induced the molecules that mobilize PMN-MDSCs from the bone marrow, as well as the chemoattractants and endothelial adhesion molecules that are essential for their subsequent accumulation, within the tumor site, and 3) that elevated IL1β expression significantly increased the number of PMN-MDSCs that infiltrated tumors and increased the immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic function of both MDSC populations. Our results also revealed that although G-CSF and Bv8 could augment the numbers of Ly6G+CD11b+ cells in the circulation, these molecules were not sufficient for tumor infiltration of PMN-MDSCs, which also depended on the coincident expression of the trafficking mediators. However, although the multiple IL1β-inducible factors have very distinct roles in the accumulation and trafficking of MDSCs, they do have overlapping capacities to modulate the functional activities of the different MDSC populations. We also showed that the effect of intratumoral accumulation of IL1β in modulating the recruitment and function of MDSCs, and the progression of tumors also applied to melanoma tumors. Finally, the translational relevance of our studies was underscored by the observation that human RCC tissue samples also expressed mRNAs encoding G-CSF, CXCR2-directed chemokines, vascular adhesion molecules, and PMN-MDSC effector molecules at levels corresponding to their synthesis of IL1β.

It is now understood that MDSCs mediate their tumor-promoting activities through both angiogenic and immunosuppressive mechanisms, although controversy exists in the literature over which MDSC subtype is the most immunosuppressive and/or pro-angiogenic, and whether those activities are differentially manifested in vitro and in vivo, or in inflammatory vs non-inflammatory environments (10,12,30,35–38). These conflicting results are compromised, however, by the fact that most published functional studies were performed using purified splenic or circulating MDSCs, and not MDSCs isolated from the tumors themselves, where most of their tumor-promoting activities are mediated (15).

Hence, we focused heavily on the number and properties of the two MDSC subsets within the tumors, and how these were each selectively influenced by the IL1β-driven inflammatory environment. One finding of our study was that CT26-IL1β tumors were infiltrated by 50-fold more PMN-MDSCs, but 50% fewer M-MDSCs than CT26 parental non-inflammatory tumors. The PMN-MDSC recruitment disparity is likely based on the substantial increases we observed in expression of G-CSF, multiple CXCR2-directed chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL7), and vascular adhesion molecules (P-selectin, E-selectin, ICAM-1) by the IL1β-overexpressing tumors. The vital importance of tumor-derived CXCR2 ligands for PMN-MDSC recruitment was confirmed by our results indicating that PMN-MDSC infiltration of CT26-IL1β was reduced in CXCR2-deficient mice. Additional results of our study suggest that some of the PMN-MDSCs infiltrating CT26-IL1β tumors might have been initially recruited as M-MDSCs, but then subsequently transitioned to PMN-MDSCs in the inflammatory TME. The individual roles of the various IL1β-inducible molecules in mediating the production and infiltration of PMN-MDSCs was clarified by our studies with G-CSF- and Bv8-transfected CT26 tumors, each of which increased the numbers of circulating and splenic PMN-MDSCs. However, those growth factors did not significantly augment the infiltration of PMN-MDSC populations into the tumor, likely reflecting our observation that both G-CSF and Bv8 failed to modulate chemokine or adhesion molecule expression. The same finding was made using the 4T1 murine breast cancer line, which produces high levels of G-CSF but only low levels of the necessary vascular adhesion molecules and CXCR2-directed chemokines. These results refute previous hypotheses suggesting the possibility that G-CSF and Bv8 might each individually play a direct role in MDSC recruitment and extravasation into tumor tissue (39,40). The finding that the non-inflammatory CT26 parental tumor is enriched with M-MDSCs but comparatively few PMN-MDSCs is consistent with that tumor’s constitutive synthesis of elevated CCR2-directed chemokines, but extremely low CXC chemokines (ligands for CXCR2).

Previous reports indicate that tumor-infiltrating MDSCs are more suppressive than splenic MDSCs, although they do not specify if the MDSCs examined were monocytic or granulocytic, or whether they were obtained from inflammatory or non-inflammatory tumors (37). Our study demonstrated that when isolated from the same non-inflammatory CT26 parental tumors, the PMN-MDSCs expressed significantly greater amounts of mRNAs encoding angiogenic and immunosuppressive tumor-promoting molecules than the M-MDSCs. IL1β expression within a TME further promoted these properties in both subpopulations, and although the activities of M-MDSC were the most enhanced, those of PMN-MDSC were increased as well – PMN-MDSCs purified from CT26-IL1β tumors had 3–15–fold more mRNA encoding angiogenic activities (VEGF, Bv8, matrix metalloproteinase MMP9, and S100A9) than those derived from CT26 parental tumors, whereas the inflammatory, CT26-IL1β-derived M-MDSCs had hundreds fold more expression of those molecules than the non-inflammatory tumor-derived M-MDSCs. Similar effects were observed for expression of the immunosuppressive molecules (arginase 1, iNOS, and IL10) when M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs from parental versus IL1β-expressing tumors were compared.

Essentially all of the angiogenic and immunosuppressive molecules expressed by MDSCs and measured in these studies were dependent on STAT3, a transcription factor now understood to be an important regulator of inflammation-associated tumorigenesis (41). G-CSF and Bv8 both activate and are themselves stimulated by STAT3 signaling (42,43), and although receptors for both hematopoietic molecules are expressed by MDSCs (42,44), it is only the Bv8 receptors that are detected on many peripheral tissues including endothelial cells (45,46). This likely explains why Bv8-transfected tumors stimulated abundant G-CSF mRNA, but G-CSF-transfected tumors did not stimulate detectable, intratumoral expression of Bv8.

For technical reasons, most of the previous clinical studies attempting to relate cytokine and chemokine expression to tumor progression and cancer patient survival depended on serum or plasma levels for their analyses, and have demonstrated correlations between IL1β, CXCL1, CXCL5, and/or CXCL8 with peripheral blood numbers of PMN-MDSCs, tumor grade, and/or time to death (47–50). Only comparatively few labs, including our own, have further demonstrated that the human tumor tissue itself was the source of the chemokines, or even contained CXCR2+ cells (34,51,52). We extended these studies by analyzing RCC tissue from nephrectomy specimens and found a broad spectrum of immunofluorescence staining for IL1β, reflecting the range of inflammatory character within RCC tumors. Quantitative RT-PCR performed on mRNA from 26 of these tissues also demonstrated a correlation between IL1β mRNA expression and mRNAs encoding the downstream IL1β-inducible growth factors, cytokines, CXCR2-directed chemokines and adhesion molecules that we found to be associated with the PMN-MDSC infiltration of the CT26-IL1β tumors. Unlike the mouse inflammatory tumors, the human RCC samples did not uniformly express all CXCR2-interacting chemokines, even when expressing elevated IL1β. In the 24 patient tumors examined we observed a statistically significant relationship between poor survival and elevated, intratumoral expression of the IL1β-inducible chemokine CXCL1, consistent with reports demonstrating a correlation between CXCL1 expression and lung cancer progression (50), formation of a pre-metastatic niche in colorectal cancer (33), and TCGA database results using a study of 604 RCC patients corroborating its relationship with survival. Analysis of IL1β-induced chemokines and growth factor expression by cultured tumors cells suggested that the tumor cells themselves were not completely responsible for the inducible expression of these factors. Specifically, which stromal cells produce which chemokines, and whether the IL1β responsiveness of stromal cells within the TME governs the nature of MDSC infiltration and function remains to be determined, but is likely important for defining candidate cell populations for therapeutic targeting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest. This work was supported by NHI grants R01 CA168488 to JF, and R21 CA188767 to CMDM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apte RN, Dotan S, Elkabets M, White MR, Reich E, Carmi Y, et al. The involvement of IL-1 in tumorigenesis, tumor invasiveness, metastasis and tumor-host interactions. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2006;25(3):387–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantovani A, Barajon I, Garlanda C. IL-1 and IL-1 regulatory pathways in cancer progression and therapy. ImmunolRev 2018;281(1):57–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajendran P, Chen YF, Chen YF, Chung LC, Tamilselvi S, Shen CY, et al. The multifaceted link between inflammation and human diseases. J Cell Physiol 2018. doi 10.1002/jcp.26479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pesic M, Greten FR. Inflammation and cancer: tissue regeneration gone awry. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2016;43:55–61 doi 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Inflammation and cancer: how hot is the link? BiochemPharmacol 2006;72(11):1605–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer ImmunolRes 2017;5(1):3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2009;58(1):49–59 doi 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J, Montero AJ. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. SeminOncol 2014;41(2):174–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. NatRevImmunol 2009;9(3):162–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peranzoni E, Zilio S, Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Zanovello P, Mandruzzato S, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity and subset definition. CurrOpinImmunol 2010;22(2):238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity 2010;32(6):790–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binsfeld M, Muller J, Lamour V, De VK, De RH, Bellahcene A, et al. Granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote angiogenesis in the context of multiple myeloma. Oncotarget 2016;7(25):37931–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kowanetz M, Wu X, Lee J, Tan M, Hagenbeek T, Qu X, et al. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor promotes lung metastasis through mobilization of Ly6G+Ly6C+ granulocytes. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 2010;107(50):21248–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sevko A, Umansky V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells interact with tumors in terms of myelopoiesis, tumorigenesis and immunosuppression: thick as thieves. JCancer 2013;4(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maenhout SK, Thielemans K, Aerts JL. Location, location, location: functional and phenotypic heterogeneity between tumor-infiltrating and non-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology 2014;3(10):e956579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma B, Nannuru KC, Varney ML, Singh RK. Host Cxcr2-dependent regulation of mammary tumor growth and metastasis. ClinExpMetastasis 2015;32(1):65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griswold DP, Corbett TH. A colon tumor model for anticancer agent evaluation. Cancer 1975;36(6 Suppl):2441–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulaski BA, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduction of established spontaneous mammary carcinoma metastases following immunotherapy with major histocompatibility complex class II and B7.1 cell-based tumor vaccines. Cancer Res 1998;58(7):1486–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingren AG, Bjorkdahl O, Labuda T, Bjork L, Andersson U, Gullberg U, et al. Fusion of a signal sequence to the interleukin-1 beta gene directs the protein from cytoplasmic accumulation to extracellular release. Cell Immunol 1996;169(2):226–37 doi 10.1006/cimm.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donovan J, Brown P. Blood collection. CurrProtocImmunol 2006;Chapter 1:Unit. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko JS, Rayman P, Ireland J, Swaidani S, Li G, Bunting KD, et al. Direct and differential suppression of myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets by sunitinib is compartmentally constrained. Cancer Res 2010;70(9):3526–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tannenbaum CS, Wicker N, Armstrong D, Tubbs R, Finke J, Bukowski RM, et al. Cytokine and chemokine expression in tumors of mice receiving systemic therapy with IL-12. JImmunol 1996;156:693–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldman M, Craft B, Zhu JC, Haussler D. Cancer genomics visualization and interpretation using UCSC Xena. Cancer research 2018;78(13) doi 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-2274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youn JI, Kumar V, Collazo M, Nefedova Y, Condamine T, Cheng P, et al. Epigenetic silencing of retinoblastoma gene regulates pathologic differentiation of myeloid cells in cancer. NatImmunol 2013;14(3):211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer M, Werner S. Cancer as an overhealing wound: an old hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008;9(8):628–38 doi 10.1038/nrm2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruoslahti E Specialization of tumour vasculature. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2(2):83–90 doi 10.1038/nrc724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ablikim M, Achasov MN, An L, An Q, An ZH, Bai JZ, et al. Evidence for psi’ decays into gammapi0 and gammaeta. Phys Rev Lett;105(26):261801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha P, Okoro C, Foell D, Freeze HH, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Srikrishna G. Proinflammatory S100 proteins regulate the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. JImmunol 2008;181(7):4666–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunt SK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Leips J, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Inflammation induces myeloid-derived suppressor cells that facilitate tumor progression. JImmunol 2006;176(1):284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu S, Bhagat G, Cui G, Takaishi S, Kurt-Jones EA, Rickman B, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell 2008;14(5):408–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang AL, Miska J, Wainwright DA, Dey M, Rivetta CV, Yu D, et al. CCL2 Produced by the Glioma Microenvironment Is Essential for the Recruitment of Regulatory T Cells and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells. Cancer Res 2016;76(19):5671–82 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesokhin AM, Hohl TM, Kitano S, Cortez C, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Avogadri F, et al. Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer research 2012;72(4):876–86 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D, Sun H, Wei J, Cen B, Dubois RN. CXCL1 Is Critical for Premetastatic Niche Formation and Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res 2017;77(13):3655–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Najjar YG, Rayman P, Jia X Jr., Pavicic PG, Rini BI, Tannenbaum C, et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Subset Accumulation in Renal Cell Carcinoma Parenchyma Is Associated with Intratumoral Expression of IL1beta, IL8, CXCL5, and Mip-1alpha. ClinCancer Res 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. JImmunol 2008;181(8):5791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. JClinInvest 2007;117(5):1155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maenhout SK, Van LS, Emeagi PU, Thielemans K, Aerts JL. Enhanced suppressive capacity of tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells compared with their peripheral counterparts. IntJCancer 2014;134(5):1077–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrams SI, Waight JD. Identification of a G-CSF-Granulocytic MDSC axis that promotes tumor progression. Oncoimmunology 2012;1(4):550–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shojaei F, Wu X, Zhong C, Yu L, Liang XH, Yao J, et al. Bv8 regulates myeloid-cell-dependent tumour angiogenesis. Nature 2007;450(7171):825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W, Zhang X, Chen Y, Xie Y, Liu J, Feng Q, et al. G-CSF is a key modulator of MDSC and could be a potential therapeutic target in colitis-associated colorectal cancers. Protein Cell 2016;7(2):130–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. NatRevCancer 2009;9(11):798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawano M, Mabuchi S, Matsumoto Y, Sasano T, Takahashi R, Kuroda H, et al. The significance of G-CSF expression and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the chemoresistance of uterine cervical cancer. SciRep 2015;5:18217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu X, Zhuang G, Yu L, Meng G, Ferrara N. Induction of Bv8 expression by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in CD11b+Gr1+ cells: key role of Stat3 signaling. JBiolChem 2012;287(23):19574–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrara N, LeCouter J, Lin R, Peale F. EG-VEGF and Bv8: a novel family of tissue-restricted angiogenic factors. BiochimBiophysActa 2004;1654(1):69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franchi S, Giannini E, Lattuada D, Lattanzi R, Tian H, Melchiorri P, et al. The prokineticin receptor agonist Bv8 decreases IL-10 and IL-4 production in mice splenocytes by activating prokineticin receptor-1. BMCImmunol 2008;9:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeCouter J, Zlot C, Tejada M, Peale F, Ferrara N. Bv8 and endocrine gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor stimulate hematopoiesis and hematopoietic cell mobilization. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA 2004;101(48):16813–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wald G, Barnes KT, Bing MT, Kresowik TP, Tomanek-Chalkley A, Kucaba TA, et al. Minimal changes in the systemic immune response after nephrectomy of localized renal masses 2. UrolOncol 2014;32(5):589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Teijeira A, Onate C, Gonzalez A, et al. Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment and follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev 2017;60:24–31 doi 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waugh DJ, Wilson C, Seaton A, Maxwell PJ. Multi-faceted roles for CXC-chemokines in prostate cancer progression. Front Biosci 2008;13:4595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan M, Zhu H, Xu J, Zheng Y, Cao X, Liu Q. Tumor-Derived CXCL1 Promotes Lung Cancer Growth via Recruitment of Tumor-Associated Neutrophils. JImmunolRes 2016;2016:6530410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mestas J, Burdick MD, Reckamp K, Pantuck A, Figlin RA, Strieter RM. The role of CXCR2/CXCR2 ligand biological axis in renal cell carcinoma. JImmunol 2005;175(8):5351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu K, Yu S, Liu Q, Bai X, Zheng X, Wu K. The clinical significance of CXCL5 in non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:5561–73 doi 10.2147/OTT.S148772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.