Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, affect millions of people and pose major personal and socioeconomic burdens. The causes of neurodegeneration are mostly unknown, although current efforts have described an autoimmune aspect to these diseases. Here we discuss recent findings that shed light on the involvement of the adaptive immune system in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, and provide a model and outlook for further investigation of T cell responses in neurodegenerative disease. We focus on the identification of T cell epitopes from proteins involved in disease pathogenesis and describe the identification of α-synuclein specific epitopes in Parkinson’s disease which provided a crucial link between disease susceptibility and T cell recognition.

Introduction

Inflammation is pervasive in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s (PD) and Alzheimer’s (AD). Here, we focus on evidence, mostly accumulated during the last decade, for a role of the adaptive immune response by T cells in PD and AD. Recent studies from our group have identified α-synuclein (α-syn)-derived T cell epitopes that are preferentially recognized by PD patients, as well as T cells in regions attacked in PD, suggesting an autoimmune component to PD [1••]. T cells also localize to the areas of degeneration in AD and recognize amyloid; but studies of their epitope and patient specificity are preliminary. We propose a model for development of neurodegenerative disease specific T cell responses to assist ongoing research. Understanding the function of the adaptive immune system in neurodegenerative pathogenesis promises novel diagnostic markers and treatments.

The case for an inflammatory and immunological component in neurodegenerative diseases

The neurodegenerative diseases of older age, including AD and PD, are major burdens to society, families, and individuals, particularly as the average life expectancy has increased. AD and PD, as well as many other neurodegenerative disorders, exhibit the loss of neurons in the central nervous system (CNS), but the means by which this occurs remains unknown [2]. These disorders also exhibit the abnormal accumulation of high levels of specific aggregated proteins [3].

In the case of PD, while multiple populations of catecholaminerigic and cholinergic neurons die over the disease course in the central and peripheral nervous system, the movement disorders are mostly due to the neuromelanin-containing dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra [4,5]. The classical pathological aggregate observed in PD brain is intracellular aggregated α-syn protein in Lewy bodies and neurites [5].

The defining pathological aggregates found in AD brain are extracellular “plaques” composed of insoluble amyloid-β (Aβ), a secreted peptide derived from the amyloid precursor protein, and intraneuronal “neurofibrillary tangles” aggregates of highly phosphorylated tau, a protein associated with microtubules in axons [6]. The deposition of tau and Aβ aggregates and neuronal loss in AD are thought to typically begin in the frontal and temporal cortical lobes, and progresses slowly throughout the neocortex and limbic system [6,7].

There is a high degree of overlap in neurodegenerative disorders of aging, where some neurons are lost in both AD and PD, as well as other diseases such as multiple system atrophy [8]. There are moreover multiple additional aggregated proteins that are found in multiple diseases, including TDP43, and many patients and studies indicate most older individuals show some aggregation of several such proteins, which may propagate in characteristic fashion depending on the disorder [8].

Reports of inflammation via the innate immune system, consisting mostly of increased levels of cytokines and activation of antigen presenting cells, has long been observed in these disorders [2,9,10]. New findings implicate a role forT cells that recognize disease related antigens, and may parallel the damage to oligodendrocytes by the acquired immune system in multiple sclerosis [11]. To date, these insights have mostly focused on PD, and as detailed here, but also apply to AD, and may well extend to other CNS disorders, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), that feature inflammatory components consistent with roles for the acquired immune system [12].

Roles for T cells in AD

AD pathological studies have long shown evidence for changes in a broad range of immune cells [13], particularly including a high presence of microglia [14]. More recently, genetic and pathological studies indicate a role associated with neurotropic virus, particularly herpes simplex [15,16]. It has been suggested that a function of Aβ peptide is to provide a protective mechanism against infection by herpes virus [17].

T cells in both the periphery and CNS are also implicated in AD, although their roles in neurodegeneration are unknown. Early pathological studies of AD patient brains reported higher numbers of CD3+ T cells in AD patients than healthy age-matched controls [18–21]. The number of hippocampal CD3+T cells was correlated with tau pathology, but not Aβ plaque load [21]. This observation implies that the extravasation of T cells into the brains of AD patients is due to tau deposition, although tau-specific T cell responses have not yet been reported.

AD mouse models that recapitulate Aβ pathology have demonstrated T cell infiltration in the brain. CD3+ T cells localize to the hippocampus of ArcAβ, APP-PS1-dE9, and Tg2576 mice, which display cerebral amyloidosis, but not in E22ΔAβ mice, in which pathology is restricted to intracellular Aβ [22]. While the number of infiltrating T cells is correlated with plaque load, these T cells do not localize on or adjacent to Aβ plaques [22]. Adoptive transfer of nonspecific Tregs into a 3xTg mouse model of AD improved cognition and reduced Aβ deposition, while depletion of Tregs aggravated spatial learning deficits in the same mice [23]. Contradictory to this finding, depletion of Tregs in the 5XFAD mouse model was also followed by reduced Aβ deposition and reversal of cognitive decline [24].

Aβ has been described as one of the antigenic targets of T cells in AD. Mouse models have indicated that protective vs. pathogenic functions of Aβ-specific T cells is determined by their Th subset phenotype, although results are contradictory. On one hand, Aβ-specific Th1 (IFNγ-producing) was shown to impair cognitive function [25], but it has also been shown that IFNγ-producing T cells improves cognitive function [26]. Aβ-specific Th2 have been shown to reverse cognitive impairment [27]. In humans, T cells that proliferate in response to Aβ has been described as significantly higher in AD patients and age-matched controls as compared to young / middle-aged (25-40 years old) adults [28]. The Aβ16-33 peptide has been identified as an immunodominant epitope in individuals irrespective of age and disease status [28]. An age-matched control cohort displayed divergent responses, with some showing highly responsive T cells, and others with no reactivity. As AD is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease, some controls were likely presymptomatic, and it may be necessary to follow individuals longitudinally to determine if Aβ reactivity has potential as a diagnostic marker.

Roles for T cells in PD

In addition to many long-standing reports of sustained microglial activation, particularly in the SN of PD patients, more recent lines of evidence suggest a role for T cells in PD [1••]. Both early and more recent pathology studies found that CD8+ and CD4+T cells were present at higher levels in the SN of PD brains [29–31], although the antigenic targets were not defined. In a mouse model using viral α-syn overexpression, MHC class II−/− mice were protected from SN neuronal death [32], indicating a role of MHC class II in neuronal death. Moreover, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) associated PD with DRB1*15:01 and DRB5*01:01 HLA class II alleles [33••], although it was not known whether this association might reflect recognition of α-syn epitopes in the context of these alleles.

Human T cells recognize α-synuclein derived peptides in PD patients

To address whether PD is associated with α-syn-specific recognition by T cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 67 PD and 36 healthy, age-matched controls were screened with potential α-syn peptides [1••]. These peptides included both overlapping 15-mers spanning α-syn and 9-10-mers predicted to bind common HLA class I alleles. This study identified several T cell epitopes, with the majority of α-syn-specific responses directed against two main antigenic regions; one centered around Y39, and the other around phosphorylated-S129 (pS129), a post-translational modification of α-syn found in Lewy bodies. The experiments revealed that the autoimmune responses to Y39 and pS129 were significantly higher in PD compared to age-matched controls. Recently, the increased frequency of α-syn-specific T cells in PD patients was confirmed by an independent study [34]. The α-syn-specific T cell responses were primarily mediated by CD4+ T cells (and some CD8+T cells) secreting IL-5, IFNγ, and to lesser extent IL-10. Some PD-specific α-syn epitopes identified in this study also displayed distinct HLA class II binding characteristics, while one epitope region demonstrated little clear restriction suggesting that it is associated with promiscuous HLA class II binding capacity. In both cases binding to five or more alleles was observed. In particular, the Y39 epitope bound the PD-associated DRB1*15:01 and DRB5*01:01 HLA proteins with high affinity, thus closely mirroring the HLA association reported in the GWAS studies. This was further analyzed by examining whether specific HLA alleles were significantly enriched in the individuals responding to the α-syn epitopes. We found that α-syn responses were significantly associated not only with HLA DRB1*15:01 and DRB5*01:01, but also DQB1*03:04 and A*11:01. Further investigation revealed that the Y39 antigenic region contains nested epitopes with an HLA A*11:01 motif that elicit IFNγ production. Additionally, we showed that HLA DRB1*15:01 expression is associated with a trend towards higher expression compared to DRB1*15:01 controls in individuals with PD. Thus, suggesting that higher expression of DRB1*15:01 could result in more HLAs available to aberrantly interact with α-syn peptides, or that the higher expression of the allele may reflect a general inflammatory state in the individuals with PD.

A recent study identified a region in α-syn with high homology to a region in HSV-1, and that both of these regions stimulated T cell responses in individuals with PD [35•], thus suggesting an environmental role in PD pathogenesis and triggering an autoimmune response [36]. In conclusion, the Y39 epitope binds with high affinity and specificity to DRB1*15:01 and DRB5*01:01, and α-syn responses are associated with DRB1*15:01, which corresponds to the alleles associated with PD in GWAS studies. The data further revealed a minor PD association with DQB1*03:04 and A*11:01. These data establish a crucial link between disease susceptibility and T cell recognition.

A working model for the role of T cells in neurodegenerative disorders

Based on these results, we have suggested a model in which α-syn-specific T cells drive neuronal death in neurodegenerative diseases associated with specific misfolded proteins. CD4+ T cell recognition of antigens presented by APC such as microglia, and by CD8+T cells on neurons, could mediate both direct and indirect neuronal damage. Substantia nigra and locus coeruleus neurons express HLA class I [9••], but there has been no description of HLA class II expression. Importantly, α-syn-epitope specific T cells have been shown to recognize exogenous native antigen (both monomer and fibrils) [1••], demonstrating that T cells can respond to epitopes arising from natural processing by APCs of extracellular native and fibrilized α-syn. Moreover, a recent study has shown that IL-17, a cytokine commonly secreted by CD4+T cells, can cause direct neuronal damage via IL-17-receptors on human IPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons [37•], providing an alternative method to how PD patient derived T cells can direct neurodegeneration. α-Syn may not be the only protein causing an autoimmune response in PD. The α-syn epitopes identified thus far are not immunogenic in 100% of individuals with PD, suggesting that other antigens might exist. For example, Lewy bodies have been known to contain tau protein and, similarly to α-syn, post-translational modifications of tau accumulate with age and/or disease. To investigate antigenicity to tau, we have synthesized tau derived peptides and are in the process of assessing their immune reactivity in individuals with PD.

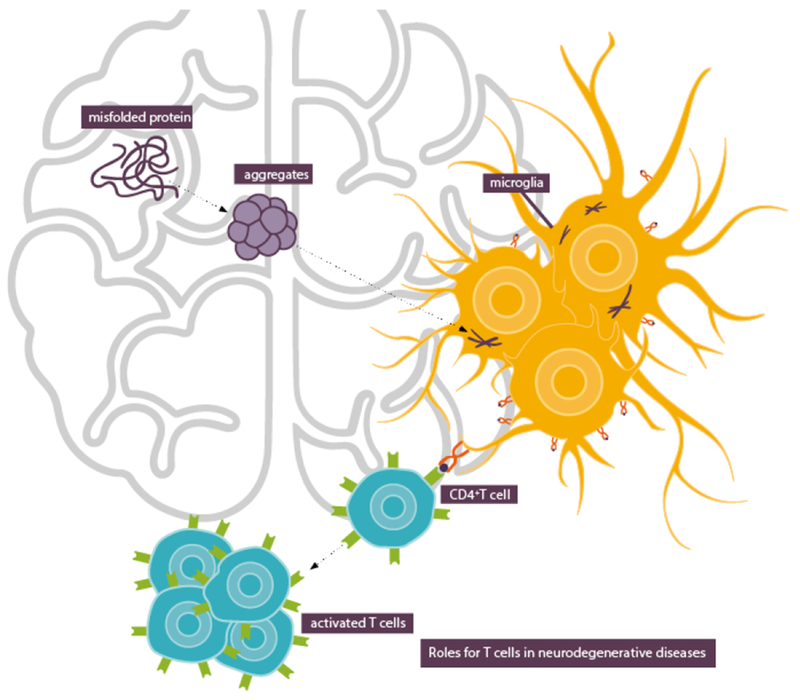

We speculate that aggregated and misfolded proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disorders, for example α-syn, tau and Aβ, are particularly prone to internalization by microglia and other immune cells with phagocytic and HLA class II processing capacity, thus initiating a cascade of events linked to immune processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aggregated and misfolded proteins are internalized by microglia and other immune cells which leads to T cell activation.

Outlook for further investigations

The current data implicating α-syn and Aβ epitopes may represent the proverbial tip of the iceberg for characterizing the role of the immune response in neurodegenerative disease. Clearly, much remains to be done. Analysis of reactivity against other additional autoantigens associated with PD, as well as investigation of the potential for T cell autoimmunity in other neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and ALS, is of clear interest. Future research should analyze the relationship between autoimmune reactivity and development of clinical manifestations. More in-depth analysis of antigen-specific T cell subsets in neurodegenerative diseases may provide avenues to limit disease progression. For example, there is limited evidence that IL-10 production is associated with recognition of α-syn epitopes by human T cells from PD patients [1••]. If these cells are distinct from those responsible for inflammatory adaptive responses, it is possible that they might be associated with regulatory functions [38], and their induction is of potential therapeutic interest. We are currently investigating α-syn-specific IL-10 regulatory responses in relation to their potential role in pathogenesis and therapy, performing phenotyping studies to establish which cell type is responsible for IL-10 production, and studying the correlation of IL-5, IFNγ and IL-10 production with the time after clinical disease onset.

It is widely appreciated that these disorders are associated with a protracted prodromal phase, where neurodegeneration precedes the onset of clear symptoms. For PD, by the time of diagnosis, 60-80% of SNpc neurons have already degenerated [39], a situation which bears some similarity to autoimmune disease (i.e., diabetes), where significant inflammation and damage precedes onset of clinical disease [40]. Detection of PD prior to SN neuron loss is a major goal of PD research, and intervening during the prodromal period may delay or prevent SNpc degradation [39]. It is therefore important to investigate whether T cell reactivity is associated with the prodromal phase; it is conceivable that a T cell based assay may identify individuals at risk or in early stages of neurodegeneration. For this purpose, the characterization of the TCR repertoire associated with recognition of α-syn and other antigens in neurodegenerative diseases will likely provide important answers. Identification of antigen-specific T cells in eurodegenerative diseases will help unveil previously unknown mechanisms that cause neurodegeneration, as well as guide the development of biomarkers, diagnostic tools and treatments and thus help affected individuals.

Conclusions

Our data establish a crucial link between T cell recognition and susceptibility to PD, a common neurodegenerative disease. Understanding the role of adaptive immune responses in neurodegenerative diseases may provide novel diagnostic and/or therapeutic strategies. Our current research efforts are aimed at expanding these lines of investigation to other antigens and other neurodegenerative diseases, and to dissecting the role of T cell reactivity in the prodromal phase and disease pathogenesis.

Highlights.

T cells play a role in neurodegenerative diseases

T cells recognize α-synuclein derived peptides in Parkinson’s patients

T cell recognition and susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease is linked

Understanding autoimmune reactivity may improve diagnosis and treatment options

The relation between autoimmunity and development of disease should be explored

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01NS095435, U19 AI118626], the Michael J Fox, JPB and Parkinson’s Foundations and UCSD-LJI Program in Immunology funding.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

Recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Sulzer D, Alcalay RN, Garretti F, Cote L, Kanter E, Agin-Liebes J, Liong C, McMurtrey C, Hildebrand WH, Mao X, et al. : T cells from patients with Parkinson’s disease recognize alpha-synuclein peptides. Nature 2017, 546:656–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• First report of α-syn-derived T cell epitopes preferentially recognized by individuals with PD and displayed by MHC alleles that are associated with PD.

- 2.Ransohoff RM: How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 353:777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar V, Sami N, Kashav T, Islam A, Ahmad F, Hassan Ml: Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative diseases: From theory to therapy. Eur J Med Chem 2016, 124:1105–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulzer D, Surmeier DJ: Neuronal vulnerability, pathogenesis, and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2013, 28:715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poewe W, Seppi K, Tanner CM, Halliday GM, Brundin P, Volkmann J, Schrag AE, Lang AE: Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3:17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masters CL, Bateman R, Blennow K, Rowe CC, Sperling RA, Cummings JL: Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1:15056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier MC: Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol 2009, 118:5–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ: Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: a focus on human studies. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015, 16:109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cebrian C, Zucca FA, Mauri P, Steinbeck JA, Studer L, Scherzer CR, Kanter E, Budhu S, Mandelbaum J, Vonsattel JP, et al. : MHC-I expression renders catecholaminergic neurons susceptible to T-cell-mediated degeneration. Nat Commun 2014, 5:3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Study describing MHCclass I expression on human catecholamineric substantia nigra and locus coeruleus neurons.

- 10.Hirsch EC, Hunot S: Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol 2009, 8:382–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA: Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2018, 378:169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCombe PA, Henderson RD: The Role of immune and inflammatory mechanisms in ALS. Curr Mol Med 2011, 11:246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao W, Zheng H: Peripheral immune system in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2018, 13:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S, Colonna M: Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease: A target for immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu C, Chyr J, Zhao W, Xu Y, Ji Z, Tan H, Soto C, Zhou X, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I: Genome-Wide Association and Mechanistic Studies Indicate That Immune Response Contributes to Alzheimer’s Disease Development. Front Genet 2018, 9:410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Readhead B, Haure-Mirande JV, Funk CC, Richards MA, Shannon P, Haroutunian V, Sano M, Liang WS, Beckmann ND, Price ND, et al. : Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron 2018, 99:64–82 e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eimer WA, Vijaya Kumar DK, Navalpur Shanmugam NK, Rodriguez AS, Mitchell T, Washicosky KJ, Gyorgy B, Breakefield XO, Tanzi RE, Moir RD: Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated beta-Amyloid Is Rapidly Seeded by Herpesviridae to Protect against Brain Infection. Neuron 2018, 100:1527–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers J, Luber-Narod J, Styren SD, Civin WH: Expression of immune system-associated antigens by cells of the human central nervous system: relationship to the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 1988, 9:339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itagaki S, McGeer PL, Akiyama H: Presence of T-cytotoxic suppressor and leucocyte common antigen positive cells in Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Neurosci Lett 1988, 91:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Togo T, Akiyama H, Iseki E, Kondo H, Ikeda K, Kato M, Oda T, Tsuchiya K, Kosaka K: Occurrence of T cells in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological diseases. J Neuroimmunol 2002, 124:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merlini M, Kirabali T, Kulic L, Nitsch RM, Ferretti MT: Extravascular CD3+ T Cells in Brains of Alzheimer Disease Patients Correlate with Tau but Not with Amyloid Pathology: An Immunohistochemical Study. Neurodegener Dis 2018, 18:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferretti MT, Merlini M, Spani C, Gericke C, Schweizer N, Enzmann G, Engelhardt B, Kulic L, Suter T, Nitsch RM: T-cell brain infiltration and immature antigen-presenting cells in transgenic models of Alzheimer’s disease-like cerebral amyloidosis. Brain Behav Immun 2016, 54:211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baek H, Ye M, Kang GH, Lee C, Lee G, Choi DB, Jung J, Kim H, Lee S, Kim JS, et al. : Neuroprotective effects of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in a 3xTg-AD Alzheimer’s disease model. Oncotarget 2016, 7:69347–69357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baruch K, Rosenzweig N, Kertser A, Deczkowska A, Sharif AM, Spinrad A, Tsitsou-Kampeli A, Sarel A, Cahalon L, Schwartz M: Breaking immune tolerance by targeting Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells mitigates Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Nat Commun 2015, 6:7967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne TC, McQuillan K, McManus RM, O’Reilly JA, Mills KH, Lynch MA: IFN-gamma Production by amyloid beta-specific Th1 cells promotes microglial activation and increases plaque burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Immunol 2013, 190:2241–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baruch K, Deczkowska A, Rosenzweig N, Tsitsou-Kampeli A, Sharif AM, Matcovitch-Natan O, Kertser A, David E, Amit I, Schwartz M: PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade reduces pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2016, 22:135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao C, Arendash GW, Dickson A, Mamcarz MB, Lin X, Ethell DW: Abeta-specific Th2 cells provide cognitive and pathological benefits to Alzheimer’s mice without infiltrating the CNS. Neurobiol Dis 2009, 34:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monsonego A, Zota V, Karni A, Krieger JI, Bar-Or A, Bitan G, Budson AE, Sperling R, Selkoe DJ, Weiner HL: Increased T cell reactivity to amyloid beta protein in older humans and patients with Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 2003, 112:415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Boyes BE, McGeer EG: Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology 1988, 38:1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGeer PL, Itagaki S, McGeer EG: Expression of the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR in neurological disease. Acta Neuropathol 1988, 76:550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brochard V, Combadiere B, Prigent A, Laouar Y, Perrin A, Beray-Berthat V, Bonduelle 0, Alvarez-Fischer D, Callebert J, Launay JM, et al. : Infiltration of CD4+ lymphocytes into the brain contributes to neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. J Clin Invest 2009, 119:182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harms AS, Cao S, Rowse AL, Thome AD, Li X, Mangieri LR, Cron RQ, Shacka JJ, Raman C, Standaert DG: MHCII is required for alpha-synuclein-induced activation of microglia, CD4 T cell proliferation, and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J Neurosci 2013, 33:9592–9600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wissemann WT, Hill-Burns EM, Zabetian CP, Factor SA, Patsopoulos N, Hoglund B, Holcomb C, Donahue RJ, Thomson G, Erlich H, et al. : Association of Parkinson disease with structural and regulatory variants in the HLA region. Am J Hum Genet 2013, 93:984–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• GWAS study showing the association of PD with HLA alleles.

- 34.Lodygin D, Hermann M, Schweingruber N, Flugel-Koch C, Watanabe T, Schlosser C, Merlini A, Korner H, Chang HF, Fischer HJ, et al. : beta-Synuclein-reactiveT cells induce autoimmune CNS grey matter degeneration. Nature 2019, 566:503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caggiu E, Paulus K, Galleri G, Arru G, Manetti R, Sechi GP, Sechi LA: Homologous HSV1 and alpha-synuclein peptides stimulate a T cell response in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroimmunol 2017, 310:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Study describing immune reactivity to homologous HSV-1 and α-syn peptides in PD.

- 36.Caggiu E, Paulus K, Arru G, Piredda R, Sechi GP, Sechi LA: Humoral cross reactivity between alpha-synuclein and herpes simplex-1 epitope in Parkinson’s disease, a triggering role in the disease? J Neuroimmunol 2016, 291:110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommer A, Maxreiter F, Krach F, Fadler T, Grosch J, Maroni M, Graef D, Eberhardt E, Riemenschneider MJ, Yeo GW, et al. : Th17 Lymphocytes Induce Neuronal Cell Death in a Human iPSC-Based Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23:123–131 e126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Study showing a role for T cells as cell death inducers of neurons.

- 38.Benoist C, Mathis D:Treg cells, life history, and diversity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2012, 4:a007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Postuma RB, Berg D: Advances in markers of prodromal Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2016, 12:622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katsarou A, Gudbjornsdottir S, Rawshani A, Dabelea D, Bonifacio E, Anderson BJ, Jacobsen LM, Schatz DA, Lernmark A: Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3:17016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]