Abstract

Renal cell carcinoma stands out as one of the most immune infiltrated tumors in pan-cancer comparisons. Features of the tumor microenvironment heavily impact disease biology and may affect responses to systemic therapy. With evolving frontline options in the metastatic setting, several immune checkpoint blockade regimens have emerged as efficacious, and there is growing interest in characterizing features of tumor biology that can reproducibly prognosticate patients and/or predict the likelihood of deriving therapeutic benefit. Herein, we review pertinent characteristics of the tumor microenvironment with dedicated attention to candidate prognostic and predictive signatures as well as possible targets for future drug development.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of kidney cancer claiming over 14,000 lives per year in the United States1. Clinically, one third of patients will present with metastatic RCC (mRCC)2. Coupled with relapsing metastases in a quarter of patients with “local” disease following curative nephrectomy, mRCC constitutes a substantial medical burden2. Although all RCCs arise from the nephrons and receive similar clinical regimens, histological subtypes are highly heterogenous in their biology and therapeutic outcomes3. The most common (70–80%) subtype, clear cell RCC (ccRCC) is also one of the most aggressive3.

Generally insensitive to cytotoxic chemotherapy and uniquely dependent on tumor angiogenesis, ccRCC emerged early as the prototype solid tumor malignancy for application of molecularly targeted agents, particularly tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) pathway2. Secondly, ccRCC has long been categorized as ‘immunotherapy responsive’, and cytokine-based regimens having been a standard before the advent of anti-angiogenic therapy2. More recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) which block PD-1/PD-L1 or CTLA-4 T cell inhibitory receptors have proven highly efficacious in this disease and are now considered standards in treatment-naïve and pre-treated patients4,5.

Recent data from large registration studies confirms that pairing VEGF-directed therapies with ICIs adds value over TKI monotherapy 6,7 and are now FDA approved. This wealth of treatment choices will leave treating oncologists with multiple FDA approved options in the first- and second-line setting. With no standard predictive biomarker available to help guide treatment selection, clinicians often rely on validated prognostic risk models – the International Metastatic RCC Database (IMDC) or Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) criteria8,9. These tools integrate clinical and laboratory variables and risk stratify mRCC patients into favorable, intermediate, or poor-risk disease. Poor prognostic factors include poor performance status, high serum calcium, low haemoglobin concentration, less than 1 year interval from diagnosis to treatment, high serum lactate dehydrogenase (MSKCC only), high neutrophil count (IMDC only), and high platelet count (IMDC only), with 0, >2 or >3 of these factors defining good, intermediate and poor risk groups respectively8,9. Expectedly, recent data confirms that these categories serve as surrogates for underlying disease biology10.

Originally developed for prognostication and stratification on clinical trials, these criteria have recently emerged as tools to help with treatment selection. Specifically, combination ICI therapy with ipilimumab plus nivolumab has shown superiority over TKI monotherapy with sunitinib in patients with intermediate and poor-risk disease, while similar in efficacy with long-term follow-up in the favorable-risk setting11. With the approval of combination TKI plus ICI strategies for ccRCC, IMDC risk stratification is no longer sufficient for treatment selection, as benefit over TKI monotherapy was apparent across all three risk groups6,7. Rather, the field awaits biomarker data to recapitulate how these agents synergize to manipulate the stromal and immune tumor microenvironment to elicit an antitumor response. With that in mind, and through a series of larger scale analyses from retrospective cohorts and clinical trials, it has become apparent that expression-based analyses are more likely to prove useful in identifying predictive signatures than tumor genomics.

In this review, we first describe the relatively unique and heterogeneous tumor microenvironment (TME) of ccRCC. To understand the potential mechanisms of synergy between VEGF TKIs and ICIs, we summarise how these therapies alter the immune TME, and highlight specific features important for systemic therapy decision-making.

The Heterogeneous Tumour Microenvironment of ccRCC

The truncal event in 90% of ccRCCs is biallelic loss of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor, which functions as a negative regulator of the HIF1α/2α transcription factors12. HIF accumulation drives the cellular hypoxic response leading to increased angiogenesis, glycolysis and aberrant fatty acid metabolism thus bestowing ccRCC with its characteristic glycogen and lipid-rich cytoplasmic deposits and hyper-vascularity13.

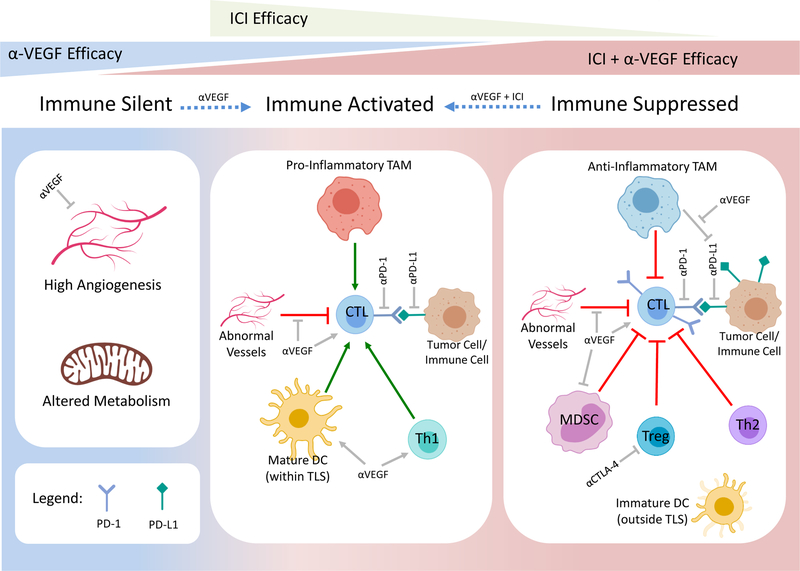

It is well appreciated that angiogenesis and immunity are closely interlinked, and targeting VEGF can promote immune surveillance by normalising dysfunctional tumor vessels14. In line with this, validated RNAseq-derived gene signatures showed that ccRCC has the highest angiogenesis score and is also highly immune infiltrated when compared to 18 epithelial cancer types15,16. More specifically, ccRCC has the highest overall T cell, CD8, Th1, dendritic cell (DC), neutrophil, and cytotoxic cells and relatively low Th2 and regulatory T cell (Treg) scores suggesting an overall pro-inflammatory profile15. However, such pooled analyses can be misleading as accumulating data continues to highlight the heterogeneity within ccRCC, with distinct subgroups differing in expression of angiogenesis programs, immune infiltration patterns and clinical outcomes (Figure 1)10,15,17,18.

Figure 1. Emerging model of targeted therapy efficacy within distinct ccRCC subgroups.

Transcriptomically distinct prognostic and predictive subgroups of ccRCC can be broadly defined as: 1) immune silent, characterised by low immune infiltration, high angiognesis and altered metabolism, 2) immune activated, characterised by pro-inflammatory immune infiltrates, and 3) immune suppressed, characterised by an overall anti-inflammatory cell milieu. Anti-VEGF, ICI and combination therapy of aVEGF and ICI are most effective in highly angiogenic immune silent tumors, immune activated tumors and immune suppressed tumors, respectively (represented by triangles at top). Anti-VEGF treatment can promote immune infiltration and activation, whereas combination treatment with aVEGF and ICI may reinvogorating the active anti-tumor immune response (dashed blue arrows). White boxes below each ccRCC subgroup depicts their respective tumor microenvironments and potential cellular targets of aVEGF or ICI therapies. Generally accepted targets for ICIs include inhibiting CTL downregulatory signals derived from Tregs, tumor or other immune cells. Beyond inhibiting angiogenesis, anti-VEGF therapies can also promote CTL recruitment and activation by unclear mechanisms which may include normalising abnormal tumor vessels, inhbiting MDSCs, promoting Th1 and DC activation and potentially by inhibiting anti-PD-L1-efficacy-limiting myeloid cells. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; DC, dendritic cell; Th1, T helper 1; Th2, T helper 2; Treg, regulatory T cells; MDSC. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell; TLS, tertiary lymphoid structures; αPD-1, anti-programmed cell death-1; αPD-L1, anti-programmed cell death-ligand 1; αVEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors. Created with Biorender.com.

Early efforts at molecular characterisation of RCC by development of a 34-gene expression signature derived from microarray data, allowed separation of patients into two broad prognostic groups, ccA and ccB17,19. These were characterised by high angiogenesis and improved prognosis or high lymphocyte, macrophages and worse survival, respectively20. However, when performing simple unsupervised clustering of microarray data in 53 ccRCCs, four molecular groups could be resolved including an immune infiltrated group and three non-infiltrated groups. The non-infiltrated groups seemed to outline a spectrum of disease progression from normal tissue-like, to upregulation of hypoxia and glycolysis, followed by myc upregulation21.

Larger analyses using single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) of 415 primary tumor samples from patients with metastatic ccRCC within the TCGA database allowed further sub categorisation of these immune infiltrated tumors15. Again, a non-immune infiltrated subgroup resembling normal kidney and a poorly immune infiltrated group with high angiogenesis resembling ccA tumors was identified. Interestingly, within the T cell enriched cluster, two distinct sub-clusters emerged, termed TCa and TCb. While TCa patients had similar survival to non-infiltrated and poorly infiltrated groups, TCb had the overall poorest survival and was significantly enriched with macrophages, stromal cells, and immunosuppressive Treg and Th2 cell signatures15.

Similar molecular subgroups were validated at the protein level by Giraldo et al when combining gene expression data with detailed flow cytometry phenotyping of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Analysis of tumors from 40 localised ccRCC tumors identified three distinct groups: immune silent, immune activated and immune regulated22. Whereas TILs in the immune silent group resembled non-malignant kidney resident TILs, the immune activated and immune regulated groups were infiltrated by activated CD8 T cells. However, T cells in the immune regulated group were less clonal and poorly cytotoxic, with more Tregs and dysfunctional DCs, compared to immune activated tumors. The immune regulated group, analogous with TCb tumors, were enriched with high-grade tumors (74% grade 3–4) and had the highest risk of relapse. More recent studies also support that inflamed tumors have worse survival compared to non-inflamed but highly angiogenic tumors, when patients were categorised using a novel deconvolution method utilising RCC-specific immune and stromal genes23. It would be useful to validate and refine the existence of immune activated and regulated clusters using these RCC-specific signatures.

In summary, these data suggest that highly immune infiltrated tumors are more aggressive than angiogenic tumors, consistent with observations across IMDC risk groups10. However, T cell activation state within infiltrated tumors is a stronger prognostic indicator. Unlike most other cancer types, overall high CD8 T cell infiltration in ccRCC is associated with worse prognosis, suggesting that the infiltrating CD8 T cell pool may be dominated by suppressed and dysfunctional cells. Indeed defective T cell function has been reported in many ccRCC studies24–31. Thus simple measurement of single populations such as CD8 T cells are unlikely to provide sufficient prognostic or predictive information.

Determinants of Effective T cell Responses in ccRCC

Tumor Immunogenicity

It is generally thought that tumor-specific mutations give rise to immunogenic neo-antigens that can drive immune infiltration, a prerequisite for ICI efficacy. Accordingly, tumor mutation burden (TMB) and genomic instability serve as robust predictors of ICI response in many malignancies32. CcRCC is a historically immunogenic cancer, but the precise nature of the T cell-activating neoantigens still eludes us. Interestingly, amongst other highly infiltrated cancer types such as lung adenocarcinoma and melanoma, ccRCC stands out as having only a modest mutation burden15. TMB is similar between MSKCC prognostic risk groups33 and immune infiltration is independent of predicted neoantigen affinity 15. Ultimately, TMB alone does not predict RCC response to ICI18,34–36.

Although non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (nsSNVs) are the most established readout of TMB, frameshifts caused by small nucleotide insertions or deletions (indels) are predicted to generate more immunogenic neoantigens than nsSNVs. In pan-cancer comparisons, indels are strikingly abundant in ccRCC perhaps explaining the disparity between low SNVs and high immune infiltration34. However in the IMmotion-150 phase II trial, indels and frameshift burdens were not significantly associated with response to atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) alone or combined with bevacizumab (anti-VEGF)18.

Expression of the germline encoded genes CSAG2 (a cancer testis antigen) and 7 different endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are re-activated in ccRCC, and are positively associated with CYT score (a GZMB- and PRF1-based gene expression metric strongly associated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte abundance; CTL)37. Whether CSAG2 and ERV-derived neoantigens can elicit T cell responses and influence ICI efficacy is unknown, but these alterations occur relatively infrequently. On going efforts to identify immunogenic RCC antigens is critical for future development of novel vaccination or adoptive cell transfer approaches.

Tumor immunogenicity is also dependent on successful presentation of tumor neoantigens by antigen presenting cells. High levels of somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) are independently associated with immune evasion across cancer types, including ccRCC, and predict worst response to ICI in melanoma35. Interestingly, reduction of cytotoxic CD8 and NK cells was predicted only by chromosomal and arm-level but not focal SCNA events, despite a significant overlap in genes. The authors speculate that the protein imbalance may impair key signals such as neoantigen peptide presentation, which are required for immunogenicity.

Moreover, high SCNA ccRCC tumors were associated with significantly decreased ratios of pro- and anti-inflammatory cells and cytokines, and lower ratios of proinflammatory M1/anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages compared with low SCNA tumors, together suggesting that high tumor SCNA promotes both immune exclusion and an immunosuppressive microenvironment35. Given these significant effects on the inflammatory milieu and the recurrent patterns of SCNA occurring in ccRCC38, interrogation of the predictive power of SCNA in ICI therapy is warranted.

T Cell Suppression

In highly infiltrated ccRCC tumors, T cell activation state is a pivotal determinant of ccRCC prognosis, and likely of immunotherapy response (discussed later). To determine which cell types may mediate T cell suppression, co-infiltration analyses were performed on over 7000 tumors from the TCGA database spanning 23 different cancer types39. Consistent with the TCa and TCb groups observed in ccRCC15, in 5 other cancer types (lung adenocarcinoma, glioma, pancreatic, ovarian and bladder) tumors with high CD8 T cell infiltrates could be subdivided into prognostic groups in which low macrophage levels dictated longer survival times39. This is also true of ovarian and lung cancers with low CD8 infiltrates highlighting the T-cell dependent and independent tumor-promoting effects of macrophages which are well reviewed elsewhere40.

Recently, mass cytometry was used to comprehensively phenotype tumor resident T cell and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) from 73 ccRCC patients spanning stage I-IV and metastatic disease, including adjacent normal kidney29. T cells were the most prevalent immune subset (50%) followed by TAMs (25%), natural killer (9%), B cells (4%) and other low frequency cells included plasma cells, dendritic cells and neutrophils. The authors teased out 20 T cell and 17 macrophage clusters, highlighting the sheer heterogeneity of cell subtypes and sub-states.

In agreement with other data, tumor-infiltrating T cells (abundant in tumor but not normal or early stage disease) were predominantly CD8+ cells expressing high levels of co-inhibitory receptors including PD-1 and low levels of the proliferation marker Ki-67, indicative of a near exhausted phenotype. Tregs also comprised a significant proportion, together depicting a largely exhausted and immunosuppressive T cell landscape in advanced ccRCC tumors.

In contrast to T cells, human macrophage subsets are far less characterised and exhibited more heterogeneous marker expression across clusters. Interestingly, three prevalent mature TAM populations distinct from normal kidney resident macrophages were identified, termed M5, M11 and M13, and tended not to co-occur. Instead M5 TAMs, characterised by high CD38 expression, were positively associated with the number of Tregs or exhausted T cells. CD38 is upregulated in human monocytes and macrophages in response to classic pro-inflammatory stimulus (lipopolysaccharide; LPS) but not the alternative macrophage stimulus IL-441 and has been demonstrated to be critical for macrophage FcγR-mediated phagocytosis albeit only in mice42. This suggests that the CD38+ M5 macrophage subset may be pro-inflammatory in nature, promoting initial T cell activation and eventual exhaustion in ccRCC, but further functional characterisation is required.

In contrast, the M11 and M13 TAMs were mutually exclusive with activated and exhausted T cells. In fact, M11 seems to be mutually exclusive with all T cell clusters. It is tempting to speculate that these M11 TAMs may be involved in T cell exclusion, a phenomena recently reported in human lung tumors and mouse breast cancer models43. In fitting with this hypothesis, low M5, high M11 and high M13 macrophages corresponded to poor survival in ccRCC, but validation is required in larger cohorts29. Of note, three sizeable macrophage clusters expressed high levels of the commonly used pro-tumor M2 macrophage marker CD206. These include M11 TAMs but also two potentially non-pathogenic tissue-resident macrophage populations. In sum, this crucial study highlights the complexity and need to co-characterise TAM subsets and T cell activation states in predictive and functional studies.

Dendritic cells can also modulate TIL function in ccRCC. Tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) have been shown to exist in various human tumors including RCC and are sites of T cell activation with immune organisation analogous to lymph nodes44. Localisation of mature dendritic cells (DCs) within TLS was associated with better survival in ccRCC patients with high levels of activated CD8 T cells22,28. In contrast more DCs located outside of TLS was associated with co-infiltration of dysfunctional CD8 T cells and poor survival, together suggesting that local T cell priming by DCs within TLS is a key component of effective tumor immune surveillance.

RCC TME and Systemic Therapies

VEGF Directed Effects on TME

Current FDA-approved anti-angiogenesis agents have known immunomodulatory effects both through VEGF and their effects on other tyrosine kinase receptors. For instance, pre-surgical bevacizumab reduces total CD68+ macrophages45. Bevacizumab treatment has also been shown to increase gene signatures related to Th1 responses, and high CD8+ T cell infiltration has been shown with combination bevacizumab and atezolizumab46. Pre-surgical pazopanib is associated with a reduction in CD8+ T cell infiltration, increased PD-L1 expression, and enhanced DC activation proposed through downregulation of the p-ERK/β-catenin pathway47,48. Sunitinib is associated with a reduction in Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) with an improved Th1 response49,50. This effect has therapeutic implications as reductions in Tregs during sunitinib treatment are associated with prolonged survival51. Sunitinib has also been shown to enhance overall T cell infiltration including Tregs, CD8, and CD4 cells52. This is accompanied by increased tumor cell PD-L1 expression and negative associations for survival suggesting that sunitinib may enhance initial immune responses, but cannot prevent subsequent immunosuppression. As each agent may demonstrate distinct immune compartmental changes and downstream impacts on survival10, continued large-scale efforts which characterize these changes will be crucial in designing novel combination strategies.

Several studies suggest that RNA based molecular signatures from tumor tissue can have predictive and prognostic implications for VEGFR TKI therapy, possibly more so than traditional IMDC risk stratification. For instance, Beuselinck and colleagues performed unsupervised cluster analysis to distinguish 4 subgroups of RCC tumors:: ccrcc1–421. Patients with ccrcc1/4 tumors had lower response rates and had shorter PFS and OS when compared with ccrcc2/3 tumors to both sunitinib and pazopanib therapy21,53. Further analyses delineated broader differences between these tumor subgroups: ccrcc2 tumors were hallmarked by angiogenesis-high gene signatures, and ccrcc3 tumors had indolent disease courses. In contrast, ccrcc1 tumors had lower rates of T cell infiltration and were typically “immune-cold”, and ccrcc4 tumors had high T cell infiltration with high expression display of inhibitory markers like PD-1, cognate ligands PD-L1/PD-L2, LAG3, TGF-β, and high expression of activated myeloid cells with high CSF-1 expression. Subsequent analyses suggest that these signatures may also inform surgical decision making for patients considered for metastasectomy54.

Large-scale correlative work from the COMPARZ trial, a phase III study of treatment naïve metastatic RCC patients treated with sunitinib or pazopanib, has uncovered several TME factors associated with outcomes on VEGFR TKI therapy10. In this analysis, four biologically distinct groups were identified by uninformed RNA-based consensus clustering with significant differences in median progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Amongst the groups cluster 3 had the best OS and was associated with the highest angiogenesis scores. Forty-one percent of ccRCC patients harbor PBRM1 loss of function mutations55. PBRM1 mutations were enriched in cluster 3 and were also associated with improved response to sunitinib in a separate cohort18, in fitting with its known roles in augmenting the HIF-mediated hypoxia response signature of VHL-deficient tumors56.

Cluster 4 had the worst OS and was enriched for BAP1 and TP53 mutations. In addition, cluster 4 demonstrated high enrichment for immune and particularly macrophage gene signatures with associated high PD-L1+ macrophage enrichment. High macrophage infiltration was associated with poor OS (HR 1.54, p=0.0018) and angiogenesis-low/macrophage-high signatures had the worst OS with TKI therapy (HR 3.12, p=0.000003). However, when considering the two TKIs separately, angiogenesis had only marginal impact on survival within the pazopanib cohort but remained significantly predictive for improved sunitinib response. This data remains in line with results from the phase II IMmotion-150 study in which sunitinib achieved improved PFS in angiogenesis-high tumors compared to angiogenesis-low (HR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18–0.55)18. In contrast, macrophages were significantly predictive for poor response to pazopanib but not sunitinib, emphasizing that different TKIs can modulate the TME in different ways. Supporting this, hepatocellular carcinoma models implanted into immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice show that the anti-tumor activity of the anti-angiogenesis TKI lenvatinib but not sorafenib, is dependent on adaptive immunity57. In sum, these data support the characterization of stromal and cellular immune components of the TME in an effort to develop RNA based biomarker signatures for VEGF-directed therapies10.

Immune Checkpoint Blockade and TME

The differences in therapy response and survival when comparing combination ICI therapy and VEGFR TKI therapies are rooted in underlying tumor biology. In the phase III registration study of ipilimumab and nivolumab versus sunitinib, patients with intermediate-poor risk disease had superior survival and response compared with favorable-risk patients, setting this regimen apart from others4. In IMmotion-151, a phase III study of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib, angiogenesis-high signatures were more prevalent in MSKCC favorable-risk patients compared with intermediate and poor-risk (p = 4.28e-06)58. TME may also significantly influence response differences seen across sarcomatoid de-differentiated tumors. Subgroup analyses of sarcomatoid patients treated with combination ICI or VEGF plus ICI therapy have shown impressive response rates, including a complete response in 18.3% for ipilimumab plus nivolumab59, 11.8% for pembrolizumab plus axitinib60, and 10% for atezolizumab plus bevacizumab61. As these tumors have higher PD-L1 expression and T-effector gene signatures, with lower angiogenesis-signatures, compared to their non-sarcomatoid counterparts61, this may provide rationale for the robust responses seen to combination ICI therapy.

Specific TME features that correlate with combination VEGF plus ICI therapy response have been gleaned from the above-mentioned IMmotion-150 study, a phase II 3-arm randomized study of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, atezolizumab, and sunitinib monotherapy. Consistent with data from the COMPARZ cohort10, sunitinib had improved PFS and response rate in those tumors harboring angiogenesis-high vs. low signatures. This difference in both response and survival rates was not seen in the atezolizumab monotherapy arm suggesting that angiogenesis is not predictive of anti-PD-L1 response. When directly comparing outcomes for atezolizumab and sunitinib monotherapy, no difference was seen in PFS overall nor when stratified by levels of angiogenesis or T effector cells. Overall, the combination arm was only significantly superior to sunitinib in patients with >1% PD-L1-expressing immune cells, emphasizing the necessity for prior immune activation in tumors for ICI combination efficacy. Further, angiogenesis-low tumors had improved PFS with combination ICI plus VEGF therapy when compared to sunitinib monotherapy. Interestingly, when stratifying T effector high tumors by myeloid signature abundance, the combination arm was superior to atezolizumab monotherapy in myeloid high but not low groups, suggesting that myeloid immunosuppression hinders single-agent ICI therapy, and that the immunomodulatory effects of concurrent VEGF-inhibition can help overcome this18. Validation of these molecular analyses were confirmed in the phase III IMmotion-151 study, where T effector signatures were associated with superior PFS with combination atezolizumab plus bevacizumab when compared to sunitinib monotherapy (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.99), and high T effector gene signatures are associated with increased PD-L1 expression. Further, combination therapy is associated with superior PFS compared to sunitinib in those tumors with angiogenesis-low tumors (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.52–0.89)58,62. Recently, PBRM1 was discovered to confer resistance to T-cell induced apoptosis and deletion in a B16F10 melanoma mouse model increases susceptibility to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-463. In small RCC cohorts, PBRM1 was also suggested to be a positive predictor of anti-PD-1 efficacy64, but this signal was not seen in the context of anti-PD-L1 therapy18. Given this conflicting data, validation in larger cohorts is required and PBRM1 mutations should not be used a biomarker at present.

Novel Approaches to Manipulating the TME

With the identification of specific TME constituents and their recognized impact on treatment responses, combination strategies that target distinct cell populations may help overcome treatment resistance. As highlighted here, TAMs significantly contribute to VEGFR TKI and ICI therapy resistance, and targeting of specific macrophage specific pathways may represent a novel treatment for patients with advanced RCC. Direct blockade of colony stimulating factor-1 and its cognate receptor (CSF-1 / CSF-1R), responsible for recruitment and differentiation, and CD47/SRPα, responsible for transmitting a protective “don’t eat me” signal, may represent new therapeutic avenues for investigation for patients harboring macrophage-high tumors65,66. The institution of these new therapies may be facilitated by the integration of rapid biomarker assessment tools and incorporation of novel radiomic approaches. Ferumoxytol enhanced MRI or hybrid MR/PET scans using alternative tracers can identify TAMs67,68, and combination imaging modalities have shown high concordance between imaging and RNA-sequencing data distinguishing angiogenesis-low or high tumors69. Application of these modalities may also yield similar classifying metrics; for example, hybrid PET/MRI has been shown to distinguish tumors into ccA and ccB classifications represented by either angiogenesis-high or TGFβ/epithelial to mesenchymal transition-high tumor differentiation70. Integration of these tools will lead to future biomarker driven studies which help select and stratify patient based on individual TME characteristics for response evaluation.

Agents that additionally target other immunosuppressive populations through alternative mechanisms serve as attractive strategies for paired or enhanced ICI response. Entinostat, a HDAC inhibitor, has shown inhibitory effects on monocytes and neutrophils71, and paired ICI therapies to target immunosuppressive MDSCs or TAMs using this approach remain underway ()72. Early phase studies of X4P-001, a CXCR4 inhibitor which downregulates HIF2-α with preliminary efficacy in advanced RCC patients, also may downregulate MDSC trafficking73. Further, pegilodecakin, a pegylated IL-10 which increases CD8+ T cells and reduces TGF-β, has shown preliminary efficacy when combined with an anti-PD-1 agent, but interestingly has shown hemophagocytic lymphohysticytosis (HLH) (7.9% any grade, n=38) as a reported treatment side effect. As HLH only occurred in this small cohort of RCC patients and preliminarily not in other solid tumors, whether this effect represents a heightened macrophage activation state due to the high infiltration of TAMs in RCC specifically is unclear. The prodrug NKTR-214, a CD-122 agonist designed to provide sustained signaling through the IL-2 receptor pathway, has been shown to activate and expand NK and CD8+ effector T cells over Tregs. In a phase I trial, serial TME analyses during treatment showed that NKTR-214 induces an increase in total and proliferating NK cells, CD8+ and CD4+ cells, with correlations between peripheral immune cells and immune infiltration in the tumor74. Preliminary results for the combination of NKTR-214 with ICI have shown clinical responses, and higher clinical benefit for those patients whose tumors were PD-L1+ at baseline or those tumors which converted to PD-L1+ during treatment75.

Metabolic based therapeutic strategies which alter the TME also remain under active investigation in early phase studies. CB-839, a selective glutaminase inhibitor which blocks formation of glutamate metabolites and cell proliferation, may have additional effects as other constituents of the TME compete for nutrients76. Combination strategies utilizing CB-839 with VEGFR TKI, mTOR inhibitors, and ICI agents are ongoing (, , ). Metabolic changes with CB-839 and downstream oxidative stress may be captured radiographically and new PET avid tracers of glutamine metabolism which capture glutamine and glutamate conversion may aid in monitoring treatment response with therapeutic use77. In a small cohort of advanced RCC patients, peripheral blood metabolic analysis highlights additional metabolic pathways including IDO and adenosine and associations with ICI therapy response. Patients with no response to PD-1 monotherapy had significantly higher adenosine levels at baseline and while on-treatment, and high levels were associated with a significantly worse PFS (p=0.004)78. The use of CPI-444, an A2A receptor antagonist, may overcome this dampening and promote immune responses when combined with ICIs (). On-treatment tumor biopsies also show high associations between CD8+ T cell infiltration and response with CPI-444 treatment when compared to baseline samples (p<0.016), and implementation of an adenosine gene signature composed of chemokines and cytokines associated with myeloid derived suppression were also associated with response (p<0.008)79. Interestingly, this adenosine signature is similar to the myeloid-high signature previously used for characterization in the IMmotion-150 trial, supporting the role of adenosine as an additional mechanism for tumor escape80.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Molecular classification of RCC tumors into tumors harboring high expression of angiogenic or inflammatory signatures are associated with differential responses to VEGF-directed and ICI based therapies. Whether these distinct ccRCC subgroups exist along a spectrum of high angiogenesis followed by immune infiltration and eventual immunosuppression is not yet known, but given their associations with prognosis and stage this would not be surprising.

TAMs play a significant role in both VEGFR TKI and ICI therapy resistance and directed attention to macrophages and other immunosuppressive compartments in the RCC TME provides therapeutic opportunity to salvage therapeutic response in refractory patients. Although several macrophage depletion agents are under clinical evaluation, TAMs are highly heterogenous and it is likely that targeting specific TAM subpopulations may lead to better outcomes than pan-macrophage ablation. Further comprehensive functional characterisation of ccRCC TAMs and their interplay with T cells is greatly needed and will likely be guided by emerging high-resolution technologies such as single cell RNAseq (scRNAseq).

We have discussed the treatment-altering insights made possible by large-scale genomic analyses of clinical trial specimens, but it is important to note the limitations of current genomic tools. Conflicting reports on the prognostic effects of macrophages in ccRCC10,22,39 may be confounded by the high degree of macrophage heterogeneity and highlights the inherent challenge this poses for the generation of cell-type specific gene signatures for accurate quantification of immune populations from bulk RNA sequencing data. Indeed, existing immune gene signatures were not sufficiently representative of RCC-specific transcripts and immune populations23. Development of RCC-specific signatures could greatly improve the accuracy of ccRCC immune deconvolution, but further refinement of these signatures is needed, as a small proportion of leukocytes were still misidentified23.

Finally, deep sequencing of multiple regions of primary and metastatic tumors from over 100 ccRCC patients revealed that single region biopsies relied on to date are unlikely to capture the full spectrum of tumor subclones and that metastases are significantly more clonal than primary tumors81,82. This has fundamental implications for the interpretation of the majority of published studies that infer TME characteristics and therapeutic outcomes of metastatic clones from the phenotypes of fully excised primary tumors. Moreover, important spatial or co-infiltration patterns can be missed when relying fully on genomics and protein cytometry28,83. Going forward, multi-region assessments and integrative genomic and imaging-based models will be critical for robust clarifications of the relationships between tumor genomics, the TME and their impact on immunotherapy outcomes.

Significance:

Tumor microenvironment features broadly characterizing angiogenesis and inflammatory signatures have shown striking differences in response to immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenic agents. Integration of stromal and immune biomarkers may hence produce predictive and prognostic signatures to guides management with existing regimens as well as future drug development.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest: M.H.V reports receiving commercial research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genentech/Roche, honoraria from Novartis, travel/accommodation from Eisai, Novartis and Takeda, consultant/advisory board member for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Calithera Biosciences, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Exelixis, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Natera, Novartis and Pfizer. A.A.H, L.V. and R.K. have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD & Jemal A Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 68, 7–30 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choueiri TK & Motzer RJ Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 376, 354–366 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linehan WM Genetic basis of kidney cancer: role of genomics for the development of disease-based therapeutics. Genome research 22, 2089–2100 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 378, 1277–1290 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 373, 1803–1813 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 380, 1103–1115 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rini BI, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine 380, 1116–1127 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer RJ, et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 17, 2530–2540 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heng DY, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 27, 5794–5799 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakimi AA, et al. Transcriptomic Profiling of the Tumor Microenvironment Reveals Distinct Subgroups of Clear cell Renal Cell Cancer - Data from a Randomized Phase III Trial. Cancer discovery 9, 510–525 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannir NM, et al. Thirty-month follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 214 trial of first-line nivolumab + ipilimumab (N+I) or sunitinib (S) in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, 547–547 (2019).30650044 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh JJ, et al. Chromosome 3p Loss-Orchestrated VHL, HIF, and Epigenetic Deregulation in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, JCO2018792549 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hakimi AA, et al. An Integrated Metabolic Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer cell 29, 104–116 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG & Jain RK Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 15, 325–340 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senbabaoglu Y, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment characterization in clear cell renal cell carcinoma identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant messenger RNA signatures. Genome biology 17, 231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshihara K, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nature communications 4, 2612 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks SA, et al. ClearCode34: A prognostic risk predictor for localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. European urology 66, 77–84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDermott DF, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nature medicine 24, 749–757 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Velasco G, et al. Molecular Subtypes Improve Prognostic Value of International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium Prognostic Model. The oncologist 22, 286–292 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iglesia MD, et al. Genomic Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltrates Across 11 Tumor Types. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 108(2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beuselinck B, et al. Molecular subtypes of clear cell renal cell carcinoma are associated with sunitinib response in the metastatic setting. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 21, 1329–1339 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giraldo NA, et al. Tumor-Infiltrating and Peripheral Blood T-cell Immunophenotypes Predict Early Relapse in Localized Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 23, 4416–4428 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T, et al. An Empirical Approach Leveraging Tumorgrafts to Dissect the Tumor Microenvironment in Renal Cell Carcinoma Identifies Missing Link to Prognostic Inflammatory Factors. Cancer discovery 8, 1142–1155 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakano O, et al. Proliferative activity of intratumoral CD8(+) T-lymphocytes as a prognostic factor in human renal cell carcinoma: clinicopathologic demonstration of antitumor immunity. Cancer research 61, 5132–5136 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson RH, et al. PD-1 is expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells and is associated with poor outcome for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 13, 1757–1761 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang QJ, Hanada K, Robbins PF, Li YF & Yang JC Distinctive features of the differentiated phenotype and infiltration of tumor-reactive lymphocytes in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer research 72, 6119–6129 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siska PJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysregulation and glycolytic insufficiency functionally impair CD8 T cells infiltrating human renal cell carcinoma. JCI insight 2(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giraldo NA, et al. Orchestration and Prognostic Significance of Immune Checkpoints in the Microenvironment of Primary and Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 21, 3031–3040 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chevrier S, et al. An Immune Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell 169, 736–749 e718 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ricketts CJ, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell reports 23, 3698 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsushita H, et al. Neoantigen Load, Antigen Presentation Machinery, and Immune Signatures Determine Prognosis in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer immunology research 4, 463–471 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Havel JJ, Chowell D & Chan TA The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Cancer 19, 133–150 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Velasco G, et al. Tumor Mutational Load and Immune Parameters across Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Risk Groups. Cancer immunology research 4, 820–822 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turajlic S, et al. Insertion-and-deletion-derived tumour-specific neoantigens and the immunogenic phenotype: a pan-cancer analysis. The Lancet. Oncology 18, 1009–1021 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davoli T, Uno H, Wooten EC & Elledge SJ Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science 355(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samstein RM, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nature genetics 51, 202–206 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G & Hacohen N Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell 160, 48–61 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beroukhim R, et al. Patterns of gene expression and copy-number alterations in von-hippel lindau disease-associated and sporadic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Cancer research 69, 4674–4681 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varn FS, Wang Y, Mullins DW, Fiering S & Cheng C Systematic Pan-Cancer Analysis Reveals Immune Cell Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer research 77, 1271–1282 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noy R & Pollard JW Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity 41, 49–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amici SA, et al. CD38 Is Robustly Induced in Human Macrophages and Monocytes in Inflammatory Conditions. Frontiers in immunology 9, 1593 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang J, et al. The role of CD38 in Fcgamma receptor (FcgammaR)-mediated phagocytosis in murine macrophages. The Journal of biological chemistry 287, 14502–14514 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peranzoni E, et al. Macrophages impede CD8 T cells from reaching tumor cells and limit the efficacy of anti-PD-1 treatment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, E4041–E4050 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Goc J, Giraldo NA, Sautes-Fridman C & Fridman WH Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends in immunology 35, 571–580 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamma R, et al. Microvascular density, macrophages, and mast cells in human clear cell renal carcinoma with and without bevacizumab treatment. Urologic oncology 37, 355 e311–355 e319 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallin JJ, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab enhances antigen-specific T-cell migration in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nature communications 7, 12624 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powles T, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Pazopanib Therapy Prior to Planned Nephrectomy in Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cancer. JAMA oncology 2, 1303–1309 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zizzari IG, et al. TK Inhibitor Pazopanib Primes DCs by Downregulation of the beta-Catenin Pathway. Cancer immunology research 6, 711–722 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finke JH, et al. Sunitinib reverses type-1 immune suppression and decreases T-regulatory cells in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 14, 6674–6682 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ko JS, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 15, 2148–2157 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adotevi O, et al. A decrease of regulatory T cells correlates with overall survival after sunitinib-based antiangiogenic therapy in metastatic renal cancer patients. Journal of immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md. : 1997) 33, 991–998 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu XD, et al. Resistance to Antiangiogenic Therapy Is Associated with an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer immunology research 3, 1017–1029 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Verbiest A, et al. Molecular Subtypes of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Are Associated With Outcome During Pazopanib Therapy in the Metastatic Setting. Clinical genitourinary cancer 16, e605–e612 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verbiest A, et al. Molecular Subtypes of Clear-cell Renal Cell Carcinoma are Prognostic for Outcome After Complete Metastasectomy. European urology 74, 474–480 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varela I, et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature 469, 539–542 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao W, Li W, Xiao T, Liu XS & Kaelin WG Jr. Inactivation of the PBRM1 tumor suppressor gene amplifies the HIF-response in VHL−/− clear cell renal carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114, 1027–1032 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura T, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of lenvatinib contributes to antitumor activity in the Hepa1–6 hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cancer science 109, 3993–4002 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rini BI, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (IMmotion151): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 393, 2404–2415 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McDermott DF, et al. CheckMate 214 post-hoc analyses of nivolumab plus ipilimumab or sunitinib in IMDC intermediate/poor-risk patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid features. Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, 4513–4513 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rini BI, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): Outcomes in the combined IMDC intermediate/poor risk and sarcomatoid subgroups of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, 4500–4500 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rini BI, et al. Atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) versus sunitinib (sun) in pts with untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and sarcomatoid (sarc) histology: IMmotion151 subgroup analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, 4512–4512 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rini BI, H.M., Atkins MB, McDermott DF, Powles T, Escudier B, Banchereau R, Liu L, Leng N, Fan J, Doss J, Nalle S, Carroll S, Li S, Schiff C, Green M, and Motzer RJ. Molecular Correlates Differentiate Response to Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab vs Sunitinib: Results From A Phase III Study (IMmotion151) in Untreated Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma). Annals of Oncology 29, Abstract LBA31 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pan D, et al. A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science 359, 770–775 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miao D, et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science 359, 801–806 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Advani R, et al. CD47 Blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and Rituximab in Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine 379, 1711–1721 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pathria P, Louis TL & Varner JA Targeting Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cancer. Trends in immunology 40, 310–327 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Locke LW, Mayo MW, Yoo AD, Williams MB & Berr SS PET imaging of tumor associated macrophages using mannose coated 64Cu liposomes. Biomaterials 33, 7785–7793 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iv M, et al. Quantification of Macrophages in High-Grade Gliomas by Using Ferumoxytol-enhanced MRI: A Pilot Study. Radiology 290, 198–206 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yin Q, et al. Associations between Tumor Vascularity, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression and PET/MRI Radiomic Signatures in Primary Clear-Cell-Renal-Cell-Carcinoma: Proof-of-Concept Study. Scientific reports 7, 43356 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yin Q, et al. Integrative radiomics expression predicts molecular subtypes of primary clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clinical Radiology 73, 782–791 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orillion A, et al. Entinostat Neutralizes Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Enhances the Antitumor Effect of PD-1 Inhibition in Murine Models of Lung and Renal Cell Carcinoma 23, 5187–5201 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neubert NJ, et al. T cell–induced CSF1 promotes melanoma resistance to PD1 blockade 10, eaan3311 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Atkins M, et al. Abstract B201: A phase 1 dose-finding study of X4P-001 (an oral CXCR4 inhibitor) and axitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 17, B201–B201 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hurwitz ME, et al. Effect of NKTR-214 on the number and activity of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology 35, 454–454 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diab A, et al. NKTR-214 (CD122-biased agonist) plus nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: Preliminary phase 1/2 results of PIVOT. Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, 3006–3006 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tannir NM, et al. Phase 1 study of glutaminase (GLS) inhibitor CB-839 combined with either everolimus (E) or cabozantinib (Cabo) in patients (pts) with clear cell (cc) and papillary (pap) metastatic renal cell cancer (mRCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology 36, 603–603 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abu Aboud O, et al. Glutamine Addiction in Kidney Cancer Suppresses Oxidative Stress and Can Be Exploited for Real-Time Imaging. Cancer research 77, 6746–6758 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giannakis M, et al. Metabolomic correlates of response in nivolumab-treated renal cell carcinoma and melanoma patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology 35, 3036–3036 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawrence Fong JP, Jason Luke, Drew Hotson, Mario Sznol, Saby George, Toni Choueiri, Brian Rini, MD, Matthew Hellmann, MD, Shivaani Kummar, MD, Leonel Hernandez-Aya, Daruka Mahadevan, Brett Hughes, Ben Markman, Matthew Riese, Joshua Brody, Daniel Renouf, Rebecca Heist, Rachel Goodwin, Amy Weise, Leisha Emens, Stephen Willingham, Long Kwei, Ginna Laport, Richard Miller. O45 Refractory renal cell cancer (RCC) exhibits high adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) expression and prolonged survival following treatment with the A2AR antagonist, CPI-444. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer; 33rd Annual Meeting & Pre-Conference Programs of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC 2018) 6, 115 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hotson AN, et al. 1137PDIdentification of adenosine pathway genes associated with response to therapy with the adenosine receptor antagonist CPI-444. Annals of Oncology 29(2018). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Turajlic S, et al. Deterministic Evolutionary Trajectories Influence Primary Tumor Growth: TRACERx Renal. Cell 173, 595–610 e511 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Turajlic S, et al. Tracking Cancer Evolution Reveals Constrained Routes to Metastases: TRACERx Renal. Cell 173, 581–594 e512 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Keren L, et al. A Structured Tumor-Immune Microenvironment in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging. Cell 174, 1373–1387 e1319 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]