Abstract

Breast cancer cells experience a range of shear stresses in the tumor microenvironment (TME). However most current in vitro three-dimensional (3D) models fail to systematically probe the effects of this biophysical stimuli on cancer cell metastasis, proliferation and chemoresistance. To investigate the roles of shear stress within the mammary and lung pleural effusion TME, a bioreactor capable of applying shear stress to cells within a 3D extracellular matrix was designed and characterized. Breast cancer cells were encapsulated within an interpenetrating network (IPN) hydrogel and subjected to shear stress of 5.4 dynes cm−2 for 72 hours. Finite element modeling assessed shear stress profiles within the bioreactor. Cells exposed to shear stress had significantly higher cellular area and significantly lower circularity, indicating a motile phenotype. Stimulated cells were more proliferative than static controls and showed higher rates of chemoresistance to the anti-neoplastic drug paclitaxel. Fluid shear stress induced significant upregulation of the PLAU gene and elevated urokinase activity was confirmed through zymography and activity assay. Overall, these results indicate that pulsatile shear stress promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, invasive potential, chemoresistance, and PLAU signaling.

Keywords: breast cancer, mechanotransduction, shear stress, interpenetrating hydrogel, 3D bioreactor, PLAU

1. Introduction

In 2018, breast cancer was the second leading cause of cancer-related death in females accounting for 30% of all new cancer diagnosis (Siegel et al., 2018). The progression of the disease is heavily dependent on the mammary tumor microenvironment (TME) which is comprised of a variety of dynamic stimuli, including shear, compression, tension and the surrounding three dimensional (3D) extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness (Butcher et al., 2009; DuFort et al., 2011). In order to discover effective therapeutics, numerous in vitro models have been developed to isolate and explore the role of dynamic 3D stimuli within the TME (Bersini et al., 2014; Hyler et al., 2018; Li et al., 2011; Polacheck et al., 2014; Rijal and Li, 2016; Rizvi et al., 2015; Shieh et al., 2011; Sung et al., 2013; Weigelt et al., 2014).

Breast cancer cells have been shown to alter their expression and behavior contingent on specialized cues originating from the surrounding microenvironment. For instance, it has been demonstrated that breast cancer cells show increased invasiveness when cultured in 3D versus 2D substrates (Sung et al., 2013; Weigelt et al., 2014) and promote motility, adhesion, and metastasis under shear stress (Avraham-Chakim et al., 2013; Avvisato et al., 2007; Mitchell and King, 2013a; Mitchell and King, 2013b; Swartz and Lund, 2012; Xiong et al., 2017). Cancer cells within primary tumors, pleural effusions, secondary metastasis and the TME experience a wide range of shear stresses. Within the primary tumor, interstitial fluid shear stress may be as low as 0.1 dynes cm−2, but cancer cells exposed to vascular blood flow can experience fluid shear stress up to 30 dynes cm−2 (Barnes et al., 2012; Harrell et al., 2007; Mitchell and King, 2013b; Shieh and Swartz, 2011; Weinbaum et al., 1994). Interstitial velocity flow has been shown to stimulate rheotaxis within breast cancer cells, showing positive migration towards areas of elevated shear stress (Munson and Shieh, 2014; Polacheck et al., 2011; Polacheck et al., 2014). Breast cancer rheotaxis might be one mechanism guiding malignant tumor cells to distant metastatic sites. Fifty percent of all breast cancer patients present pleural effusions (Patil et al., 2015). Once advanced malignancies progress to pleural spaces, the cancer cells experience fluid shear stress ranging from 4.7 dynes cm−2 to 18.4 dynes cm−2, with maximum shear values reaching an excess of 60 dynes cm−2 (Waters et al., 1996). Furthermore, changes in the extracellular fiber architecture, differences in ECM alignment, and expansion of the tumor itself alters the velocity and path of the fluid flow across the stimulated cells (Pedersen et al., 2010). A rapidly changing TME both modulates and increases interstitial fluid flow over time within a diseased microenvironment. The continuous and elevated levels of shear stress present in the breast and malignant TME accentuates the importance of investigating the effects of shear forces within cancer progression (Pedersen et al., 2007; Pedersen et al., 2010; Shieh and Swartz, 2011).

Within the metastatic cascade of cancer, the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) system has been explicitly identified as an assistive mechanism (Mahmood et al., 2018). The uPA system aids in the degradation of surrounding ECM constructs allowing for enhanced cell migration and invasion. uPA is coded for by the Plasminogen Activator Urokinase (PLAU) gene and activates plasminogen via conversion to plasmin (Mahmood et al., 2018). Association between shear stress stimulus and the uPA system modulation has been shown for proximal tubular cells (Essig and Friedlander, 2003), endothelial cells (Diamond et al., 1989; Dolan et al., 2011; Sokabe et al., 2004), and smooth muscle cells (Papadaki Maria et al., 1998); although PLAU upregulation has been linked to metastatic cancers as a possible biomarker (Bredemeier et al., 2017; Sepiashvili et al., 2012; Tang and Han, 2013), it has yet to be directly tied to mechano-stimulus in cancer.

Several studies have investigated the effects of shear stress on various cancer types. Previously reported responses of cancer cells exposed to shear stress include increased chemoresistance, stem cell markers, viability, and changes in adhesion capability (Barnes et al., 2012; Ip et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2014). Within breast cancer specifically, shear stress has been shown to modulate stemness (Triantafillu et al., 2017), survival (Regmi et al., 2017), metastasis (Regmi et al., 2017), adhesion (Xiong et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2014), pH regulation (Kawai et al., 2013), and motility (Yang et al., 2016) though the majority of these studies fail to account for the native 3D microenvironment which significantly impacts cellular responses (Loessner et al., 2010; Weigelt et al., 2014). To more accurately probe the effects of shear stress on breast cancer, in vitro 3D models with shear stress stimulation are needed.

Here we developed a bioreactor that stimulates breast cancer cells embedded in a 3D hydrogel matrix to pulsatile fluid flow allowing for tunable shear stress stimulation (Rotenberg et al., 2012). We utilized this 3D bioreactor to investigate the effects of shear stress on MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and MCF7 breast adenocarcinoma cells in a 3D pleural effusion TME. Through this 3D bioreactor, we identified consistent trends in shape factor alterations, proliferative tendencies, mechanotransduction, and chemoresistance in breast cancer cells exposed to shear stress. These findings suggest that breast cancer cells utilize the PLAU pathway for mechanotransduction of shear stress stimulus. The bioreactor is easily modifiable for a range of shear stresses, as well as, a variety of cancer cell types, making it a feasible platform for further investigation of shear stress in a variety of cancers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Suppliers

2.1.1. Cell Culture, Hydrogel Polymerization, Drugs, Inhibitors, and Assays

The following reagents required for cell culture were purchased from Gibco (Cleveland, TN): DMEM growth medium (31–053-028), RPMI growth medium (11875119), antibiotic/antimycotic (15240062), 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (25–200-056), and L-Glutamine (25030081). Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF7 cell line (HTB-22), human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26) and human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-468 cell line (HTB-132), were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Agarose was obtained from Boston Bioproducts Inc. (P73050G, Ashland, MA). Paclitaxel (T7402) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Atlanta Biologicals (Flowery Branch, GA) and type I rat collagen (3443–100-01) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

2.1.2. Immunohistochemistry

The following reagents needed for immunocytochemistry were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA): formalin, Goat serum, Triton-X, bovine serum albumin (BSA), phosphate buffered saline (PBS), ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant. The anti-Ki-67 antibody (PA5–16785), anti-Caspase-3 antibody (700182), and citrate buffer was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (BDB558615, Pittsburgh, PA). Vectastain elite ABC-HRP kit, DAB, Hematoxylin, and Bloxall solution was purchased from Vector laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

2.1.3. 3D Shear Bioreactor Components

The following materials and equipment were purchased for 3D shear bioreactor fabrication: polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) elastomer and curing agent (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning, Midland, MI), polyethylene plugs (PEP) (PE16030, SPC Technologies Ltd., Norfolk, UK), poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) (11510102, Astra Products, NY, USA), tubing (PharMed BPT, Saint Gobain, Akron, OH), and peristaltic pump (FH100, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The main bioreactor body was constructed from a 14 × 14 × 2 cm acrylic block purchased and machined in the machine shop at the University of Michigan Physics department. The end plates were constructed from 6 × 6 × ½ inch aluminum plates and machined in house.

2.2. Cell Culture

Cells were cultured in 15 cm tissue culture treated polystyrene plates using RPMI 1640 growth medium (MCF7 and MDA-MB-231) or DMEM growth medium (MDA-MB-468) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X antibiotic/antimycotic until 80% confluency was reached. Cells were maintained routinely in tissue culture, until they were ready to be harvested for use in the 3D bioreactor or 3D control gels.

2.3. Construction and Characterization of Hydrogels

The interpenetrating network (IPN) hydrogel comprised of two components: agarose (3% w/v), and type I rat collagen (500 μg ml−1, Fisher). Hydrogels were supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were seeded within the liquid collagen/agarose solution at a density of 10 million/mL, before transfer to the bioreactor or control plate.

Methods for hydrogel characterization included, scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Philips XL 30, SEMTech Solutions, MA), oscillatory rheometry (ARES, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE), and mercury porosimetry (Micromeritics Mercury Porosimeter Autopore V).

SEM characterization was performed for structural analysis of the network. Gels were first flash frozen using liquid nitrogen then lyophilized (FreeZone 4.5 plus, Labconco, Kansas City, MO) for at least 24 hours before imaging with SEM.

Oscillatory rheometry was used to investigate shear moduli of the IPN hydrogel. Tests were performed using 25 mm parallel plate geometry. Frequency sweeps were performed at 0.5% strain with a frequency ranging from 100 rad s−1 to 0.1 rad s−1. The strain value for these tests was determined from strain sweeps performed at 0.3 Hz. The complex shear moduli, G*, was calculated from the resulting storage modulus, G’, and loss modulus, G”.

Mercury porosimetry (MicroActive AutoPore V9600 Version 1.02) was utilized for pore structure and permeability analysis of the IPN hydrogel. Both 3 and 5 cubic centimeter stem volumes were utilized at a mercury temperature of 18.93 °C.

2.4. 3D Shear Stress Bioreactor

2.4.1. Description

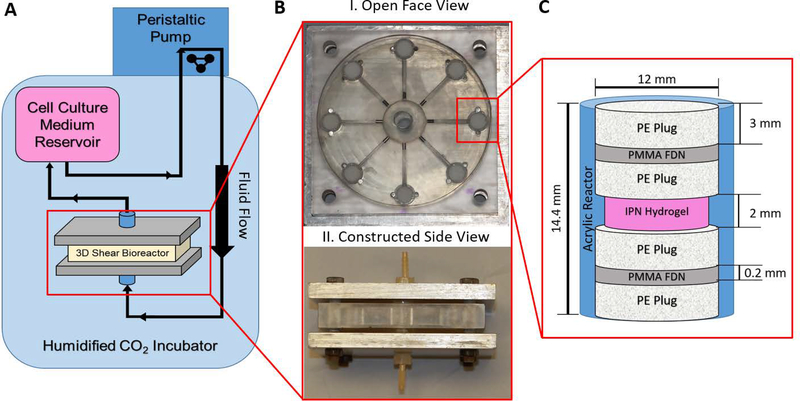

The 3D shear bioreactor was composed of a cell culture medium reservoir made from a modified IV bag that was fed through a peristaltic pump leading to the inlet of the bioreactor. The outlet of the bioreactor was connected back to the medium reservoir creating a continuous loop within the system. The layout of the 3D shear bioreactor flow circuit is depicted in Figure 1A. The bioreactor was machined from an acrylic block and consisted of 8 hydrogel stacks positioned radially from an inlet flow chamber. The flow chambers were sealed with PDMS gaskets and held in place by two compressed aluminum plates. Images of the disassembled and assembled 3D bioreactor are shown in Figure 1B. Continuous and pulsatile cell culture medium flow was provided by a peristaltic pump at volumetric flow rate of 2.28 ± 0.035 mL s−1. Cell culture medium was pumped through the inlet flow chamber, 8 hydrogel stacks, then back out the collective exit. The hydrogel stacks were composed of 3D cell laden agarose-collagen IPN gels (2 mm tall, 11.61 mm diameter) in a cylindrical column bordered by 3 mm thick polyethylene plugs (PEP), 0.2 mm thick polymethyl methacrylate fluid distribution nets (PMMA-FDN), and a second set of 3 mm polyethylene plugs all with a diameter of 12 mm. The smaller diameter gel allowed for a protective notch in the wall of the bioreactor, eliminating gel compression during plug insertion. The stack is depicted in Figure 1C. Shear stresses were modeled using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3. A detailed description of the computational model is provided in 2.4.3.

Figure 1. Schematic of the 3D shear stress bioreactor.

A) Layout of the shear bioreactor. Cell culture medium is contained in IV bag, pumped via peristaltic pump into the bottom of the reactor, and recirculated into the cell culture medium reservoir, as indicated by the directional arrows in the schematic.

B) Photo of the disassembled (I.) and assembled (II.) bioreactor. I.) Flow plate showing radial flow chambers connecting the inlet of media flow to the cell-laden hydrogel stacks. II.) Constructed bioreactor, composed of flow plate with PDMS seals and steal endplates bolted together.

C) Schematic of interpenetrating (IPN) hydrogel stack composition and dimensions. Each stack was connected via a radial flow channel to both the inlet and outlet chamber. Hydrogel stack consisted of PE plug, PMMA fluid distribution net, PE plug sandwich surrounding cell laden hydrogel to both hold the hydrogel in place and evenly distribute fluid flow.

2.4.2. Preparation, Assembly, and Use

Before use the bioreactor was washed and sterilized with a 24 hour ethylene oxide treatment at 54.4 °C. All other components were sterilized by autoclaving, exposure to 70% ethanol, and 30 minute UV treatment. The first half of the stack (PEP, PMMA FDN, PEP) was put in place, followed by the cell laden hydrogel. The cells were concentrated and spun down to 10 million cells before suspension into the hydrogel. The cells and IPN hydrogel solution was polymerized within the bioreactor and conformed to the shape of the chamber (3 min, 25 °C). After polymerization, the remaining portions of the stack (PEP, PMMA-FDN, PEP) were inserted on top of the hydrogel (Figure 1C). This was followed by placing 5 mm stainless steel rods within the flow chambers to control the velocity profile. PDMS gaskets (7 mm thick) were used to seal the bioreactor flow chambers and were compressed using bolted aluminum end plates. The inlet and outlet flow chambers were then attached to tubing, connecting the cell culture medium reservoir and pump to the bioreactor (Figure 1A). The bioreactor and cell culture medium reservoir were placed into the incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) and the pump was started at a flow rate of 1.11 cm3 s−1 before gradually increasing to 2.276 cm3 s−1. Fluid flow was provided in a direction running vertically from the bottom to the top of each hydrogel stack.

Experiments were performed for 72 hours of continuous applied shear stress. Unstimulated control 3D gels, encapsulating cells were constructed to mimic the stimulated environment as completely as possible to ensure observed phenotypic changes were only attributed to shear stress stimulation within the bioreactor. The control gels were housed in 15 cm plates, submerged in 20 mL of cell culture medium and kept within equivalent incubation conditions for 72 hours (37 °C, 5% CO2). For drug experiments paclitaxel was dissolved in the perfusate (25 μM) prior to experimental start. Paclitaxel dosage of 25 μM was previously determined as an effective IC50 in 3D cell culture (Chen et al., 2013; Sarkar and Kumar, 2016). Each experimental condition was repeated a minimum of 3 times with up to 8 technical replicates.

2.4.3. Computational Analysis of Shear Stress

A numerical model was constructed of the 3D shear bioreactor using COMSOL Multiphysics 5.3 to estimated forces experienced within the hydrogel. Symmetry was used to simplify model design. The cellular medium flow throughout the flow chambers and hydrogel stack was modeled utilizing Free and Porous Media Flow physics, as found in COMSOL and displayed in Equation 1–4.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

A second, sequential COMSOL model estimated the peak shear stresses experienced by a given cell within the hydrogel via laminar flow physics. The governing equations are shown below in Equation 5 and 6.

| (5) |

| (6) |

Equation 1 and 2 describe the Navier-Stokes equations for free-flowing medium and Equation 3 and 4 describe the Brinkman equation for porous media flow. Equation 5 and 6 describe the Navier-Stokes equation for freely moving fluid. The equation terms are defined as: ρ density, u velocity field, p pressure, I identity matrix, μ dynamic viscosity, T temperature, F external forces (e.g. gravity), ϵp porosity, κbr permeability, βF Forchheimer drag, and Qbr volumetric flow rate.

Values for the respective material properties were determined experimentally and included under Porous Matrix Properties. A hydrostatic water column was used to determine porosity values of PE and PMMA materials using Darcy’s law of permeability (Hwang et al., 2010). Porosity was calculated from SEM images of the PE and hydrogel and light microscope images of the PMMA FDN on ImageJ. For accurate estimation of these values, measurements were repeated 6 or more times each for permeability and a minimum of 3 images were quantified for porosity estimations. Permeability of the hydrogel was estimated via mercury porosimeter studies. Material characteristic values are listed in Figure 2C.

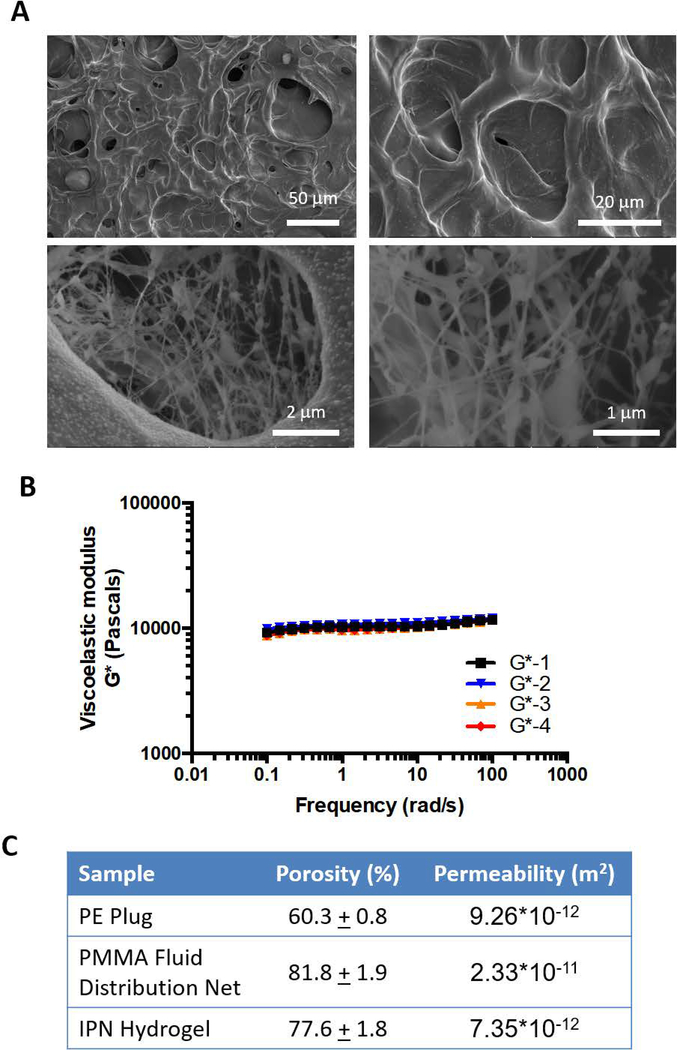

Figure 2. Material characterization of interpenetrating (IPN) hydrogel stack components.

A) SEM images of collagen/agarose IPN hydrogels in order of increasing magnification, where a reticulated network of collagen fibers was observed within a global agarose construct.

B) Graphical representation of a frequency sweep from rheometric testing of collagen/agarose IPN hydrogels. Four trials were utilized to determine viscoelastic modulus of the IPN hydrogel, averaging 10358 ± 81.56 Pa.

C) Table of material properties for each component of the hydrogel stack. Values were determined by experimental measure through SEM analysis, ImageJ quantification, hydrostatic water column flow rate, and mercury porosimetry.

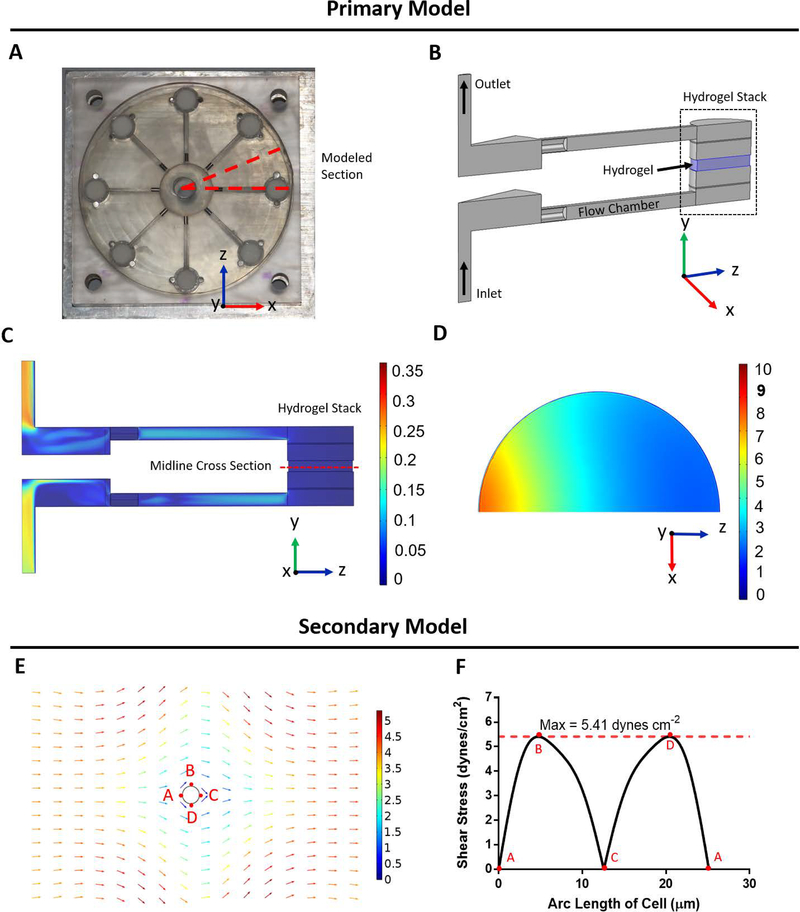

Boundary layers were placed along all edges of the models to capture accurate fluid interfaces within the 3D bioreactor. A mesh analysis was performed to confirm results were independent of mesh size (Supplemental Figure S1). Model results are depicted in Figure 3. The primary model (Figure 3A–3D) determines the average fluid velocity through the hydrogel. This value was subsequently used as input for the secondary model, simulating fluid flow around an idealized cell (Figure 3E). The resultant viscous shear stress was then recorded along the perimeter of the cell, where a maximum incident shear stress value was determined (Figure 3F) (Ip et al., 2016).

Figure 3: Finite element analysis of the 3D shear bioreactor quantifies shear stress.

A) Open face bioreactor with dotted line denoting modeled section

B) 3D COMSOL schematic of modeled section. IPN hydrogel highlighted in blue.

C) Flow velocity of modeled section in m s−1. Velocity ranges from 0–0.3 m s−1 along surface of y-z plane.

D) Flow velocity in x-z plane of midline cross section of hydrogel in mm s−1

E) Secondary model of shear stress field experienced by a single cell within the IPN hydrogel. Average fluid velocity within the hydrogel, determined from primary model (3C) was applied over an idealized spherical cell and resulting shear stress on the surface was determined.

F) Resulting shear stress around perimeter of cell within the flow field demonstrated in Figure 3E. Shear stress experienced by the cell is reported as the maximum value of 5.41 dyne cm−2.

Additionally, hypoxic conditions within the gels were investigated within a COMSOL model. Neither the 3D control nor the 3D shear stress IPN hydrogels demonstrated hypoxic conditions (Supplemental Figure S2). Further details on the hypoxic COMSOL modeling conditions can be found in the supplementary section.

2.5. Cell Morphometry Analysis

Slides were stained for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and imaged under a light microscope at 40X magnification for morphometry and shape factor analysis. These images were analyzed using ImageJ to quantify cellular area and circularity. A minimum of 3 biological replicates were analyzed each containing 8 technical replicates. A minimum of 160 cells were quantified for each condition.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry Analysis

Cell laden hydrogels, once removed from the 3D shear bioreactor or control conditions were placed in 4% neutral buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, and sectioned (perpendicular to flow direction) in preparation for immunohistochemistry analysis. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized and boiled in citrate buffer for 20 minutes. Bloxall was used to quench endogenous peroxidase activity for 10 minutes prior to application of blocking serum for 20 minutes. Primary antibody solution was incubated for 30 minutes followed by washing and secondary antibody incubation for 30 minutes. After washing ABC reagent was applied (30 min), slides were washed, and DAB was applied for approximately 1 minute while slides were viewed under a digital inverted EVOS microscope to ensure adequate color contrast. Slides were then rinsed and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were taken on an inverted Nikon E800 microscope and quantification of the resulting images were performed in ImageJ (ImageJ win64). Positive Ki67 or caspase 3 cells were counted and normalized to total cell counts within the image. Caspase 3 results were then normalized to non-drug treated controls for the respective cell line. A minimum of 5 images were taken per sample with a minimum of 3 experimental replicates analyzed per condition. Drug treated experimental results were normalized to control averages.

2.7. Upregulation of Gene Expression in Cells under Shear Stress

Total RNA was extracted from gels using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). An additional buffer RPE wash step was amended to the manufacturer’s protocol for enhanced purity. RNA quality and quantification were assessed using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). All samples used for qPCR analysis passed RNA purity (260/280 and 260/230) with a ratio of 2.0 or better. Gene expression analysis was performed in 96 well plates using qRT-PCR on a 7900HT system. 96 well plates also included qPCR controls, a reverse transcription control, and a human genomic DNA contamination control. Fold change in gene expression between control and shear stress stimulated cells was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Gene expression analysis was performed on three replicates within each cell type. Primer pairs utilized for qPCR PLAU expression were as follows: forward 5’-GGGAATGGTCACTTTTACCGAG-3’, reverse 5’-GGGCATGGTACGTTTGCTG-3’.

2.8. Urokinase Activity Assay and Zymography

To quantify the level of urokinase-type plasminogen activator (urokinase, uPA) produced in the shear stressed experiments, a Chemicon uPA activity assay kit was performed on collected phenol free DMEM medium. All results were well within the sensitivity range of the uPA activity assay kit (0.05 to 50 units of uPA activity). In brief, the medium was collected from both shear stress and control gel experiments, passed through a 0.22 μm PES sterilized filter, aliquoted, and stored in a −80 °C freezer. 160 μL of sample were then added to a 96 well plate and incubated for 2 hours in combination with a pNA grouped tripeptide chromogenic substrate (determination of incubation period can be seen in Supplemental Figure S3). Results were then quantified using a microplate reader (BioTEK Synergy HT) at an absorbance reading of 405 nm.

Urokinase activity was additionally evaluated through zymography. Experimental media was concentrated 66.7-fold through 30 kDa centricon tubes (EMD Millipore, UFC703008) and was run at 100 V at room temperature. Zymography resolving gels were fabricated from DI water (9.575 mL), acrylamide (N,N’-Methylenebisacrylamide, 29:1) solution (5.025 mL), Tris buffer (1.5 M, pH 8.8, 5 mL), 8% milk solution (1.74 mL), and plasminogen (118.4 μg) combined with SDS (10% w/v, 200 μL), ammonium persulfate (10%, 200 μL), and TEMED (8 μL). Gels were then rinsed three times in triton-100 rinsing buffer (2.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCL pH 7.5, 0.05% NaN3) for 10 minutes each. They were then incubated overnight in renaturing buffer (0.1 M Glycine pH 8.0 adjusted with NaOH). Gels were rinsed in water three times for 5-minute intervals, dyed with Simply Blue safestain for 1 hour, and rinsed in water again. Destaining was then performed with methanol (30%), acetic acid (10%) and H2O until band contrast was acceptable. Gel imaging was performed on the ChemiDoc™ Touch (BioRad, 732BR0111).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analysis and graphical plots were derived in GraphPad Prism 6.0 (www.graphpad.com, San Diego, CA). All morphological data was calculated on ImageJ, and expressed as mean ± SEM. All reported data is mean ± SEM, derived from a minimum of 3 independent biological replicated experiments. Statistical comparison was performed using one-way ANOVA for all data except the urokinase activity assay and zymography analysis where a two-tailed t-test with Welch’s correction was used.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrogel Characterization and Finite Element Model

To ensure physiological representation of the pleural effusion TME, investigation of the hydrogel and bioreactor shear stress was performed. The biophysical characteristics of the collagen-agarose IPN hydrogel, showcasing fiber morphology, shear modulus, and porosity are illustrated in Figure 2. The reticulated network of collagen fibers within the agarose hydrogel are depicted in Figure 2A. The viscoelastic modulus of the IPN hydrogel was determined to be 10.36 ± 0.08 kPa (Figure 2B) and was used in conjunction with Equation 7 to determine Young’s modulus.

| (7) |

Where E is Young’s modulus, G is viscoelastic modulus, and v is Poisson’s ratio. Poisson’s ratio was estimated at 0.5, which is common for polymers such as equilibrium hydrated agarose hydrogels (Ahearne et al., 2005).

Modeling parameters utilized for COMSOL Multiphysics modeling were as follows (porosity, permeability): PE plug (60.3 ± 0.8, 9.26 × 10−12 m2); PMMA fluid distribution net (81.8 ± 1.9, 2.33 × 10−11 m2); IPN hydrogel (77.6 ± 1.8, 7.35 × 10−12 m2) (Figure 2C). These values were then input into a finite element model using COMSOL Multiphysics (Figure 3).

Flow velocity within the simulated 3D hydrogel was output by the primary COMSOL model. Fluid flow velocity distribution at the center of the hydrogel is depicted in Figure 3D. The velocity of the cell culture medium in the x-z plane decreases in the IPN gel as distance from the flow channel increases, however flow velocity within the y direction was uniform (Supplemental Figure S1C). Fluid velocity within the entirety of the hydrogel was averaged and estimated as 3.83 mm s−1. This value was then used as the input velocity of the secondary model to estimate the shear stress experienced by cells embedded within the hydrogel. An average cell size of 8 μm in diameter, as measured from the H&E stains, and spherical initial shape of the cell was assumed. From the model, the resulting maximum shear stress experienced by the cell surface was observed to be 5.41 dynes cm−2.

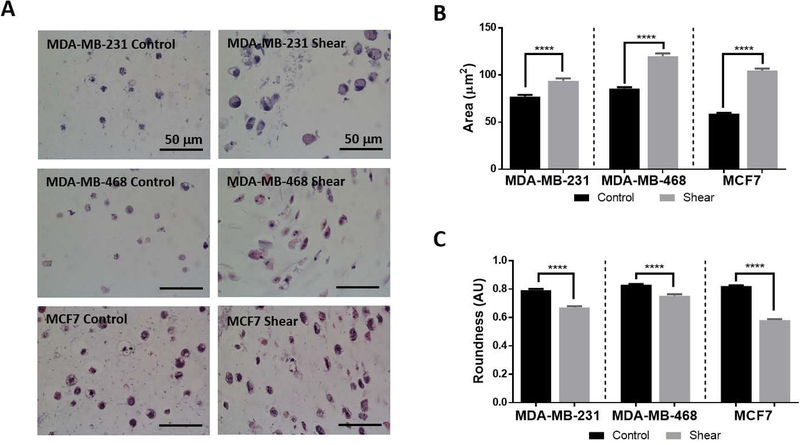

3.2. Shear Stimulation Significantly Alters Cellular Morphology of Breast Cancer Cells

Metastatic potential and invasive capability of cancer cells is often indicated through cellular morphology, thus shape factor analysis was performed. Cellular morphology of the shear stimulated cells were compared to 3D cultured controls. All cell types experiencing shear stress exhibited morphological changes including an increase in area and an elongated morphology (Figure 4A). These changes were quantified through ImageJ analysis and resulted in a significant increase in cellular area (MDA-MB-231: 1.2 fold, MDA-MB-468: 1.4 fold, MCF7: 1.8 fold) and a significant decrease in roundness (MDA-MB-231: 0.84 fold, MDA-MB-468: 0.90 fold, MCF7: 0.71 fold; Figure 4B and 4C). Perimeter and aspect ratio values were also determined to be significantly increased in all shear stressed breast cancer cells, whereas a significant decrease in circularity was found for MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cell types (Supplemental Figure S4).

Figure 4: Shear stress increases area and decreases roundness in breast cancer cells.

A) Representative H&E images of shear and control studies for each cell type. Noticeable cellular elongation and increased cellular area are seen in all shear samples. All scale bars are 50 μm.

B) Graph of cellular area quantification comparing control and sheared cells. Shear stress exposure shows significant increase in cellular area for all cell types (One-way ANOVA ****p< 0.0001, n≥3).

C) Quantification of cell roundness comparing control and sheared cells. Shear stress exposure shows significant decrease in cell roundness for all cell types (One-way ANOVA ****p< 0.0001, n≥3).

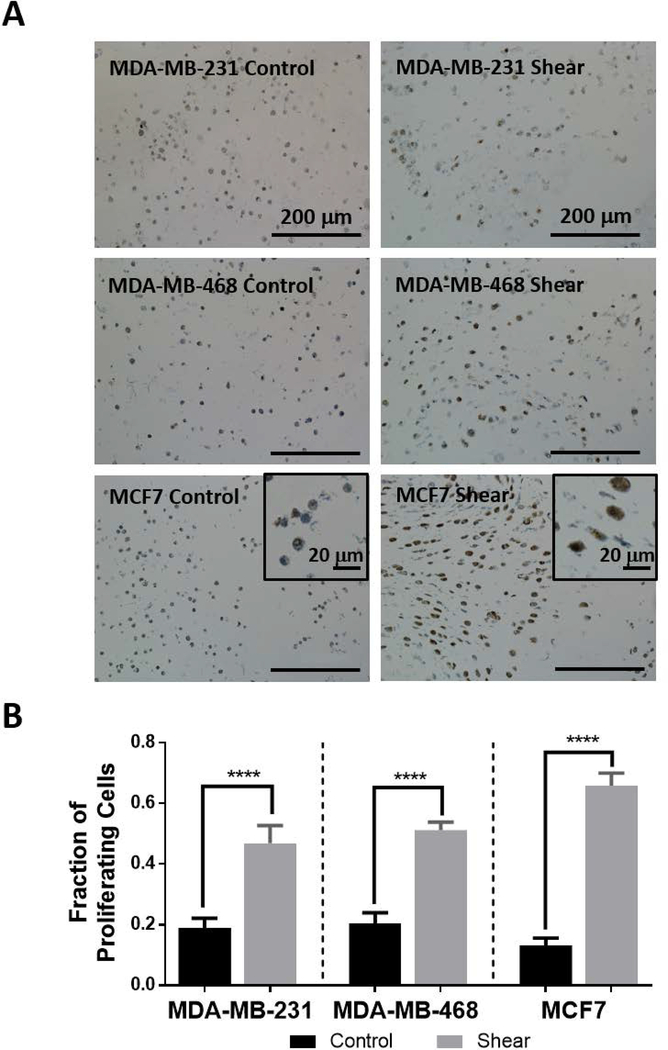

3.3. Breast Cancer Cellular Proliferation Increases with Shear Stress

To quantify the effect of shear stress on the proliferation of breast cancer cells, sections of the IPN hydrogel were IHC stained for Ki67 expression (hematoxylin counterstained) and quantified (Figure 5). Figure 5A shows representative images of control and shear stressed cells expressing Ki67. These results are graphically depicted in Figure 5B showing the fraction of proliferating cells more than doubling under shear stress for each cell type (MDA-MB-231: 2.5 fold, MDA-MB-468: 2.5 fold, MCF7: 5.0 fold).

Figure 5: Shear stress increases breast cancer proliferation.

A) Representative images of Ki67 IHC counterstained with hematoxylin. Deep brown coloring indicates a proliferating cell and was quantified manually. Counts were normalized to total cell count within each image. Scale bars are 200 μm in the main images and 20 μm in the corner frames for MCF7 cells.

B) Graphical representation of the fraction of proliferating cells for each cell type under control and shear conditions (****p< 0.0001, n≥3). All cell types show significantly increased proliferation tendency under shear stress stimulus.

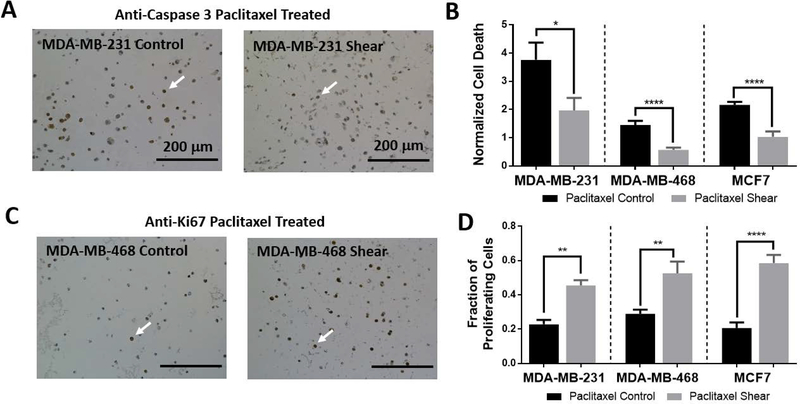

3.4. Breast Cancer Cells Show Chemoresistance while under Shear Stress Stimulus

Given that mechanotransduction can modulate cellular responses to anti-neoplastic agents (Ip et al., 2016; McGrail et al., 2014; McGrail et al., 2015), breast cancer cells were treated with 25 μM paclitaxel for 72 hours. Chemotherapy treatment was administered at the previously determined IC50 concentration of 25 μM (Chen et al., 2013; Sarkar and Kumar, 2016). This concentration was sufficient to significantly increase cell death for all drug treated controls when compared to non-drug treated controls (MDA-MB-231: 3.8 fold, MDA-MB-468: 1.5 fold, MCF7: 2.2 fold; Supplemental Figure S5) as determined through IHC caspase 3 quantification. Under paclitaxel treatment, shear stressed cells remained more viable than their drug treated control counterparts demonstrated as a significant reduction in cell death (Figure 6A and 6B).

Figure 6: Shear stress induced chemoresistance to paclitaxel treatment.

A) Representative images of caspase 3 IHC staining for MDA-MB-231 cells. Arrows indicate examples of cells positively expressing caspase 3.

B) Cells were treated with paclitaxel chemotherapy (25 μM) in either control or shear conditions and cellular death was quantified using caspase 3 IHC staining, counterstained with hematoxylin. Results were manually quantified and compared to total cell number within the image. The fraction of proliferating cells was then normalized to the non-stimulated control average of the respective cell type. All cell types showed significantly decreased death under sheared conditions (*p< 0.1, n≥3). Three or more images were quantified for each experiment and a minimum of three biological replicates were performed for each condition.

C) Representative images of Ki67 IHC staining for MDA-MB-468 cells. Arrows indicate examples of cells positively expressing Ki67.

D) Cellular proliferation was analyzed using Ki67 IHC staining on paclitaxel treated experiments. Results were manually quantified, and each cell type showed significantly enhanced proliferation in sheared samples (**p< 0.01, n≥3).

Additionally, proliferation analysis via Ki67 staining was performed on chemoresistance investigations. Proliferation remained significantly increased in drug treated shear experiments when compared to drug treated controls. Paclitaxel treatment seemed to have little effect on proliferation values as drug treated shear experiments were significantly more proliferative than non-drug treated controls (Supplemental Figure S5).

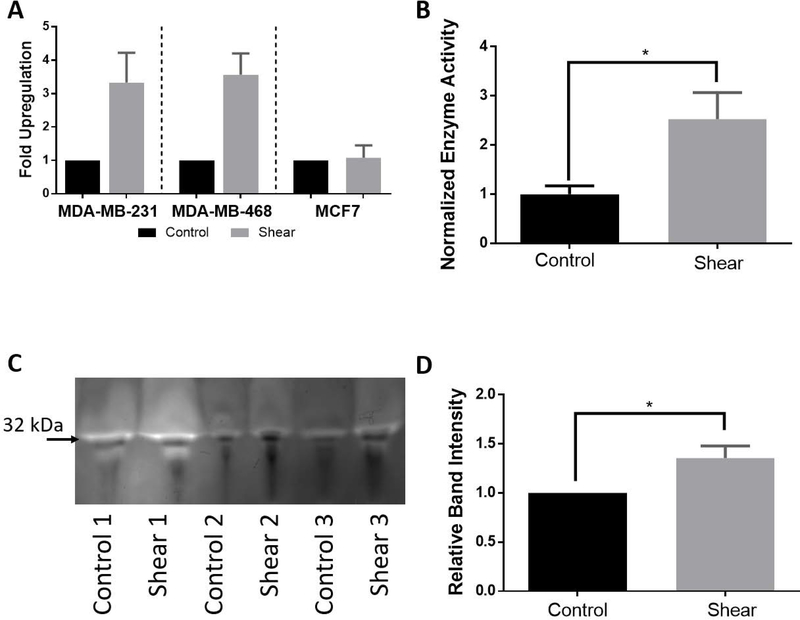

3.5. Shear Stimulation Significantly Upregulates PLAU Gene Expression

Changes in gene regulation due to shear stress stimulation was investigated for identification of potential mechanotransduction pathways. Change in the gene expression of breast cancer cells, after stimulation with shear stress for 72 hours, was quantified using qRTPCR. The PLAU gene was found to have a greater than 2-fold increase in RNA expression under shear stimulation when compared to controls for both MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cell types. MDA-MB-231 cells increased PLAU expression 3.33 ± 0.89-fold, MDA-MB-468 cells increased PLAU 3.567 ± 0.64-fold, and MCF7 cells increased PLAU 1.08 ± 0.37-fold (Figure 7A). All experimental runs are normalized to their respective controls, as such all control conditions result in a fold upregulation of 1.

Figure 7: Activity assay and zymography confirm enhanced urokinase activity under shear stimulation.

A) qPCR analysis on PLAU expression showed significant upregulation for MDA-MB-231 (*p< 0.1, n≥3) and MDA-MB-468 (**p< 0.01, n≥3). MCF7 cells showed an increase in PLAU expression but was not significant (n≥3).

B) Confirmation of PLAU upregulation was performed using a urokinase activity assay on MDA-MB-468 experimental medium. Results showed a significant increase in enzymatic activity for shear samples normalized to controls.

C) Additional confirmation of urokinase protein activity was performed via plasminogen zymography. Band intensity for three MDA-MB-468 experimental sets is sown (32 kDa low molecular weight form uPA).

D) Quantification of the zymography band intensity was normalized to their respective controls and statistically analyzed with a two tailed t-test. MDA-MB-468 sheared samples showed a significant increase in band brightness, indicating increased urokinase enzyme activity.

3.6. Protein Expression Confirms Enzymatic Activity of Urokinase

The PLAU gene encodes for the enzymatic protein urokinase which functions to degrade plasminogen into plasmin. It is a secreted protein present in all cells where it aids in the degradation of surrounding extracellular matrix to assist in cell migration/invasion. To investigate the protein expression of urokinase, both a commercially available enzymatic activity assay and a plasminogen zymography test was performed. Experimental medium was collected after the completion of three 72-hour MDA-MB-468 experiments for use in protein/enzyme analysis. Shear stressed cells were discovered to have significantly higher enzymatic activity of urokinase than the unstimulated controls (2.5 fold; Figure 7B). As a means for independent verification, zymography was performed on plasminogen acrylamide gels. After conclusion of the trial, experimental medium was concentrated and run in the zymography gel. The resulting band intensity was normalized to its respective control. Shear stimulated MDA-MB-468 cells significantly increased secretion of uPA (1.4 fold) (Figure 7C and D).

4. Discussion

Both cancer and non-malignant cells experience shear stress in many microenvironments (Jain et al., 2014; Mitchell and King, 2013b; Shieh and Swartz, 2011). The inflammatory environment surrounding the tumor, as well as the structure of the TME, act to increase interstitial flow, thus increasing the shear stress experienced by cancer cells (Harrell et al., 2007; Mitchell and King, 2013b; Pedersen et al., 2010). This mechanical stimulus aids in cellular invasion while hindering chemotherapy delivery to the center of the tumor, resulting in chemoresistance and a flow gradient outwards from the tumor (Ip et al., 2016; Lunt et al., 2008; Netti et al., 2000; Wirtz et al., 2011). These findings emphasize the importance of mechanotransduction by shear stress within the TME.

A variety of methods to apply and study the effects of shear stress on cells have already been devised. However, many of these methods study the application of force on a monolayer culture (Avraham-Chakim et al., 2013; Blackman et al., 2002; Mitchell and King, 2013a; Zhao et al., 2014). Though 2D systems can apply uniform stimulation, these methods lack the physiologic 3D shear stress found within the TME. The 3D shear models currently in existence incorporate microfluidic design or single cell analysis, which replicate the in vivo shear stress experienced by CTCs (Barnes et al., 2012; Ip et al., 2016). The constructs that investigate interstitial shear stress effects often only investigate migratory behaviors (Haessler et al., 2012) through microfluidics (Polacheck et al., 2011) and the use of Boyden chambers (Qazi et al., 2011). While this type of device is advantageous for observation of small number of cells, it provides a hurdle for further downstream analysis such as western blot or qRTPCR. In this report, we advance the existing shear bioreactor designs (Rotenberg et al., 2012) by: 1) incorporating a 3D IPN hydrogel that matches the morphology and modulus of the pleural effusion TME ECM, 2) embedding breast cancer cells within a 3D IPN hydrogel and providing variable pulsatile flow to the cells, 3) constructing a numerical model for a more accurate portrayal of fluid flow and shear stresses experienced by the breast cancer cells within the 3D bioreactor, and 4) increased yield of cells for molecular biology assays after experimental completion (not typical with microfluidic devices).

The agarose IPN hydrogel was chosen to provide a 3D microenvironment capable of easy stiffness modulation, encapsulation of cells, and blank background free of excess growth factor stimulation as to avoid excess signaling cues to the cells (Ulrich et al., 2010; Ulrich et al., 2011). The collagen type I component was included to provide minimal and easily controlled adhesive signal for the cells within the network to sense the shear stress stimulation and due to its key role within the breast cancer ECM (Ulrich et al., 2010; Ulrich et al., 2011). This hydrogel design has been previously utilized and investigated (Afrimzon et al., 2016; Lake et al., 2011; Ulrich et al., 2010; Ulrich et al., 2011). With this combination IPN gel, cells could be encapsulated in situ within the bioreactor wells under highly regulated stiffness and adherence conditions. Normal breast tissue has been reported to have a Young’s modulus of approximately 3.25 kPa whereas breast tumors range from 6.41 – 42.52 kPa in stiffness depending on disease progression (Bae et al., 2018; Samani et al., 2007). The stiffness of the IPN agarose-collagen hydrogel fell well within this range attaining a Young’s modulus value of 31.08 kPa. At this stiffness the IPN hydrogels most closely replicated intermediate to high grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma (Samani et al., 2007) and could be easily adjusted to suit alternate TME biophysical properties.

We developed a two-step COMSOL model that enables greater accuracy when calculating estimated shear force experienced by cells captured within the 3D microenvironment. The first model uses a 3D rendering of the shear bioreactor to determine the fluid velocity and velocity distribution within the hydrogel. Subsequently, the estimated velocity is input as the inlet velocity for the secondary COMSOL model that applies the input flow over an ideal spherical cell. Due to the complicated IPN network, specific adhesive sites for the cell are not included, rather the shear velocity along the surface is calculated and the maximum shear stress is reported. This two-step system is more comprehensive than previous models for similar bioreactors (Rotenberg et al., 2012) due to the inclusion of the entire continuous flow path within the bioreactor, as well as, all components of the hydrogel stack, which were found to be relevant in model results. While majority of cells experience the same maximum shear value regardless of their vertical positioning within the hydrogel, there is some variation in flow velocity in the X-Z plane. This is due to the location of the inlet flow chamber lateral to the hydrogel stack and respective flow distribution components. From these models, advanced estimates of cellular stimulation can be predicted with spatial accuracy within the hydrogel. Average shear stress values experienced by cells was determined to be 5.41 dynes cm−2.

When exposed to shear stimulation in 2D, epithelial ovarian cancer cells have been shown to elongate and increase formation of stress fibers (Avraham-Chakim et al., 2013), whereas endothelial cells align in the direction of the shear force and elongate (Avraham-Chakim et al., 2013; Blackman et al., 2002). The cell morphological data from our breast cancer cell lines under shear stress is consistent with these outcomes. Similarly, several studies demonstrate alterations in gene expression related to proliferation when exposed to shear stress (Avraham-Chakim et al., 2013; Ip et al., 2016; Mitchell and King, 2013a; Yao et al., 2007). The results of this study demonstrate that shear stress increases the proliferative ability of the breast cancer cells, where as normal vascular endothelial cells have been found to inhibit proliferation in the presence of shear stress (Akimoto et al., 2000).

Gene expression analysis showed a significant enhancement of PLAU under shear stimulation. The PLAU gene codes for uPA, a secreted protein initially found in its inactive form that is then cleaved for activation (Mahmood et al., 2018). This enzyme primarily activates plasminogen (pro enzyme) to plasmin (multiple substrate cleaving enzyme) (Rao, 2003). Plasmin then aids in the migratory cascade through degradation of ECM components, activation of MMPs, release of growth factors, and functions as a feed forward mechanism on the uPA-uPAR complex by activating pro-uPA to active uPA (Duffy, 2003; Duffy et al., 2014). Recently, uPA and its interactome have become a point of interest in cancer research due to its role in metastasis, proliferation, angiogenesis, its frequent aberrant expression within a variety of cancers, and its potential role as a diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target (Duffy et al., 2014; Mahmood et al., 2018). Many alternative studies have tied the uPA system with cancer progression such as Huang and colleagues who found a significant decrease in tumor metastasis with uPA knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells (Huang et al., 2010). Additionally, shear stress has been identified as a driver of PLAU expression (Dolan et al., 2011; Essig and Friedlander, 2003; Sokabe et al., 2004). However, to our knowledge this is the first time the PLAU excess has been tied directly to shear stress stimulus in cancer. The enhancement of uPA expression found under shear stress stimulation suggests support of the metastatic cascade via mechanotransduction mechanisms. This result is further supported by the enhanced uPA enzyme activity produced by the shear stress stimulated cells and morphological changes indicating enhanced invasive potential, emphasizing the importance of mechanotransduction to the metastatic cascade.

Finally, we investigated whether breast cancer cells under shear stress show a greater resistance to chemotherapy. Cells stimulated with shear stress were more resistant to paclitaxel treatment compared to unstimulated controls emphasizing the necessity to consider shear stress stimulus in treatment investigations. These findings are consistent with Ip et al. who tested paclitaxel treatment of ovarian cancer spheroids under shear stress (Ip et al., 2016) finding enhanced drug resistance. When cellular proliferation was investigated simultaneously with drug treatment, little effect was found on the proliferating population despite paclitaxel’s mechanism of action on cell division (Weaver, 2014). Overall, these findings reinforce the importance of recapitulating the in vivo mechanical microenvironments for fundamental and translational approaches.

The design of this shear bioreactor enables simultaneous 3D cell culture along with tunable shear stress that provides a physiologic mechanical microenvironment for cancer biology investigations. Under these conditions more accurate results for in vitro modeling, drug screening, and therapeutic investigation for breast cancer can be realized. The versatility of this model provides a platform that can be applied to a multitude of cancer cell types and drug screening, enabling a better understanding of disease states and their responses.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, an improved 3D bioreactor capable of applying tunable shear stress to breast cancer cells within an IPN hydrogel matrix was designed and constructed. With the application of shear stress, morphological changes were observed in the breast cancer cells, including increased cellular area and decreased roundness. Shear stress stimulation also increased cellular proliferation, and enhanced PLAU expression. Cells exposed to shear stress demonstrated higher resistance to chemotherapy treatment with paclitaxel, and the proliferation in this condition was unaffected. These findings demonstrate that breast cancer cells under shear stress stimulus adopt enhanced proliferation, invasion, and chemoresistant phenotypes, emphasizing the importance of shear stimulus in a 3D setting. This data reveals the role of PLAU in modulating shear stress induced mechanotransduction in breast cancer cells and provide researchers with a new 3D platform for understanding the fundamentals of shear stress induced mechanotransduction and evaluating prospective chemotherapeutics effectively and efficiently.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the DOD OCRP Early Career Investigator Award W81XWH-13-1-0134 (GM) and DOD Pilot award W81XWH-16-1-0426 (GM). This research was supported by grants from the Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer and the Michigan Ovarian Cancer Alliance (MIOCA). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA046592. CMN is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. 1256260. The authors would like to acknowledge assistance received from Dr. Shreya Raghavan, Dr. Kristopher Inman, Emily Lin, Judy Pore, and Bingxin Yu.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings can be requested by contacting the corresponding author, Dr. Geeta Mehta (mehtagee@umich.edu).

References

- Afrimzon E, Botchkina G, Zurgil N, Shafran Y, Sobolev M, Moshkov S, Ravid-Hermesh O, Ojima I, Deutsch M. 2016. Hydrogel microstructure live-cell array for multiplexed analyses of cancer stem cells, tumor heterogeneity and differential drug response at single-element resolution. Lab. Chip 16:1047–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahearne M, Yang Y, Haj AJE, Then KY, Liu K-K. 2005. Characterizing the viscoelastic properties of thin hydrogel-based constructs for tissue engineering applications. J. R. Soc. Interface 2:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto S, Mitsumata M, Sasaguri T, Yoshida Y. 2000. Laminar Shear Stress Inhibits Vascular Endothelial Cell Proliferation by Inducing Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21Sdi1/Cip1/Waf1. Circ. Res 86:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham-Chakim L, Elad D, Zaretsky U, Kloog Y, Jaffa A, Grisaru D. 2013. Fluid-Flow Induced Wall Shear Stress and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Peritoneal Spreading: e60965. PLoS One 8 http://search.proquest.com.proxy.lib.umich.edu/docview/1330895410/abstract/8C897248438C4093PQ/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvisato CL, Yang X, Shah S, Hoxter B, Li W, Gaynor R, Pestell R, Tozeren A, Byers SW. 2007. Mechanical force modulates global gene expression and β-catenin signaling in colon cancer cells. J Cell Sci 120:2672–2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SJ, Park JT, Park AY, Youk JH, Lim JW, Lee HW, Lee HM, Ahn SG, Son EJ, Jeong J. 2018. Ex Vivo Shear-Wave Elastography of Axillary Lymph Nodes to Predict Nodal Metastasis in Patients with Primary Breast Cancer. J. Breast Cancer 21:190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JM, Nauseef JT, Henry MD. 2012. Resistance to Fluid Shear Stress Is a Conserved Biophysical Property of Malignant Cells. Ed. Olson Michael F. PLoS ONE 7:e50973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersini S, Jeon JS, Dubini G, Arrigoni C, Chung S, Charest JL, Moretti M, Kamm RD. 2014. A microfluidic 3D in vitro model for specificity of breast cancer metastasis to bone. Biomaterials 35:2454–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman BR, García-Cardeña G, Gimbrone Michael A. Jr 2002. A New In Vitro Model to Evaluate Differential Responses of Endothelial Cells to Simulated Arterial Shear Stress Waveforms. J. Biomech. Eng 124:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredemeier M, Edimiris P, Mach P, Kubista M, Sjöback R, Rohlova E, Kolostova K, Hauch S, Aktas B, Tewes M, Kimmig R, Kasimir-Bauer S. 2017. Gene Expression Signatures in Circulating Tumor Cells Correlate with Response to Therapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Chem 63:1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher DT, Alliston T, Weaver VM. 2009. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:108–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wang J, Chen D, Yang J, Yang C, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Dou J. 2013. Evaluation of characteristics of CD44+CD117+ ovarian cancer stem cells in three dimensional basement membrane extract scaffold versus two dimensional monocultures. BMC Cell Biol. 14:7–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond SL, Eskin SG, McIntire LV. 1989. Fluid flow stimulates tissue plasminogen activator secretion by cultured human endothelial cells. Science 243:1483–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan JM, Sim FJ, Meng H, Kolega J. 2011. Endothelial cells express a unique transcriptional profile under very high wall shear stress known to induce expansive arterial remodeling. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 302:C1109–C1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MJ. 2003. The Urokinase Plasminogen Activator System: Role in Malignancy. Curr. Pharm. Des http://www.eurekaselect.com/62195/article. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Duffy MJ, McGowan PM, Harbeck N, Thomssen C, Schmitt M. 2014. uPA and PAI-1 as biomarkers in breast cancer: validated for clinical use in level-of-evidence-1 studies. Breast Cancer Res. 16:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuFort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. 2011. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 12:308–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essig M, Friedlander G. 2003. Tubular Shear Stress and Phenotype of Renal Proximal Tubular Cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 14:S33–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haessler U, Teo JCM, Foretay D, Renaud P, Swartz MA. 2012. Migration dynamics of breast cancer cells in a tunable 3D interstitial flow chamber. Integr. Biol 4:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell MI, Iritani BM, Ruddell A. 2007. Tumor-Induced Sentinel Lymph Node Lymphangiogenesis and Increased Lymph Flow Precede Melanoma Metastasis. Am. J. Pathol 170:774–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-Y, Jiang Z-F, Li Q-X, Liu J-Y, Wang T, Zhang R, Zhao J, Xu Y-M, Bao W, Zhang Y, Jia L-T, Yang A-G. 2010. Inhibition of Human Breast Cancer Cell Invasion by siRNA Against Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator. Cancer Invest. 28:689–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulst AC, Hens HJH, Buitelaar RM, Tramper J. 1989. Determination of the effective diffusion coefficient of oxygen in gel materials in relation to gel concentration. Biotechnol. Tech 3:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang CM, Sant S, Masaeli M, Kachouie NN, Zamanian B, Lee S-H, Khademhosseini A. 2010. Fabrication of three-dimensional porous cell-laden hydrogel for tissue engineering. Biofabrication 2:035003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyler AR, Baudoin NC, Brown MS, Stremler MA, Cimini D, Davalos RV, Schmelz EM. 2018. Fluid shear stress impacts ovarian cancer cell viability, subcellular organization, and promotes genomic instability. PLOS ONE 13:e0194170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip CKM, Li S-S, Tang MYH, Sy SKH, Ren Y, Shum HC, Wong AST. 2016. Stemness and chemoresistance in epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells under shear stress. Sci. Rep 6 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4887794/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, Martin JD, Stylianopoulos T. 2014. The Role of Mechanical Forces in Tumor Growth and Therapy. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 16:321–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y, Kaidoh M, Yokoyama Y, Ohhashi T. 2013. Cell surface F1/Fo ATP synthase contributes to interstitial flow-mediated development of the acidic microenvironment in tumor tissues. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol 305:C1139–C1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake SP, Hald ES, Barocas VH. 2011. Collagen-agarose co-gels as a model for collagen–matrix interaction in soft tissues subjected to indentation. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 99A:507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Chen C, Kapadia A, Zhou Q, Harper MK, Schaack J, Labarbera DV. 2011. 3D Models of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Breast Cancer Metastasis High-Throughput Screening Assay Development, Validation, and Pilot Screen. J. Biomol. Screen 16:141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods San Diego Calif 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loessner D, Stok KS, Lutolf MP, Hutmacher DW, Clements JA, Rizzi SC. 2010. Bioengineered 3D platform to explore cell–ECM interactions and drug resistance of epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Biomaterials 31:8494–8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt SJ, Fyles A, Hill RP, Milosevic M. 2008. Interstitial fluid pressure in tumors: therapeutic barrier and biomarker of angiogenesis. Future Oncol. 4:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood N, Mihalcioiu C, Rabbani SA. 2018. Multifaceted Role of the Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator (uPA) and Its Receptor (uPAR): Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Applications. Front. Oncol 8 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2018.00024/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrail DJ, Kieu QMN, Dawson MR. 2014. The malignancy of metastatic ovarian cancer cells is increased on soft matrices through a mechanosensitive Rho–ROCK pathway. J Cell Sci 127:2621–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrail DJ, Kieu QMN, Iandoli JA, Dawson MR. 2015. Actomyosin tension as a determinant of metastatic cancer mechanical tropism. Phys. Biol 12:026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MJ, King MR. 2013a. Fluid shear stress sensitizes cancer cells to receptor-mediated apoptosis via trimeric death receptors. New J. Phys. 15:015008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MJ, King MR. 2013b. Computational and Experimental Models of Cancer Cell Response to Fluid Shear Stress. Front. Oncol 3 http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fonc.2013.00044/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson JM, Shieh AC. 2014. Interstitial fluid flow in cancer: implications for disease progression and treatment. Cancer Manag. Res 6:317–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. 2000. Role of Extracellular Matrix Assembly in Interstitial Transport in Solid Tumors. Cancer Res. 60:2497–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maria Papadaki, Johannes Ruef, Nguyen Kytai Truong, Li Fengzhi, Cam Patterson, Eskin Suzanne G., McIntire Larry V., Runge Marschall S. 1998. Differential Regulation of Protease Activated Receptor-1 and Tissue Plasminogen Activator Expression by Shear Stress in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Circ. Res 83:1027–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil CB, Gupta A, Gupta R, Dixit R, Gupta N, Indushekar V. 2015. Carcinoma breast related metastatic pleural effusion: A thoracoscopic approach. Clin. Cancer Investig. J 4:633. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen JA, Boschetti F, Swartz MA. 2007. Effects of extracellular fiber architecture on cell membrane shear stress in a 3D fibrous matrix. J. Biomech 40:1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen JA, Lichter S, Swartz MA. 2010. Cells in 3D matrices under interstitial flow: effects of extracellular matrix alignment on cell shear stress and drag forces. J. Biomech 43:900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacheck WJ, Charest JL, Kamm RD. 2011. Interstitial flow influences direction of tumor cell migration through competing mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108:11115–11120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacheck WJ, German AE, Mammoto A, Ingber DE, Kamm RD. 2014. Mechanotransduction of fluid stresses governs 3D cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111:2447–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qazi H, Shi Z-D, Tarbell JM. 2011. Fluid Shear Stress Regulates the Invasive Potential of Glioma Cells via Modulation of Migratory Activity and Matrix Metalloproteinase Expression. Ed. Sumitra Deb. PLoS ONE 6:e20348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JS. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regmi S, Fu A, Luo KQ. 2017. High Shear Stresses under Exercise Condition Destroy Circulating Tumor Cells in a Microfluidic System. Sci. Rep 7:39975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijal G, Li W. 2016. 3D scaffolds in breast cancer research. Biomaterials 81:135–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, Miller ML, Rekhtman N, Moreira AL, Ibrahim F, Bruggeman C, Gasmi B, Zappasodi R, Maeda Y, Sander C, Garon EB, Merghoub T, Wolchok JD, Schumacher TN, Chan TA. 2015. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science:aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg MY, Ruvinov E, Armoza A, Cohen S. 2012. A multi-shear perfusion bioreactor for investigating shear stress effects in endothelial cell constructs. Lab. Chip 12:2696–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani A, Zubovits J, Plewes D. 2007. Elastic moduli of normal and pathological human breast tissues: an inversion-technique-based investigation of 169 samples. Phys. Med. Biol 52:1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar J, Kumar A. 2016. Thermo-responsive polymer aided spheroid culture in cryogel based platform for high throughput drug screening. The Analyst 141:2553–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepiashvili L, Hui A, Ignatchenko V, Shi W, Su S, Xu W, Huang SH, O’Sullivan B, Waldron J, Irish JC, Perez-Ordonez B, Liu F-F, Kislinger T. 2012. Potentially Novel Candidate Biomarkers for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Identified Using an Integrated Cell Line-based Discovery Strategy. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11:1404–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh AC, Rozansky HA, Hinz B, Swartz MA. 2011. Tumor Cell Invasion Is Promoted by Interstitial Flow-Induced Matrix Priming by Stromal Fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 71:790–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh AC, Swartz MA. 2011. Regulation of tumor invasion by interstitial fluid flow. Phys. Biol 8:015012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. 2018. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA. Cancer J. Clin 68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe T, Yamamoto K, Ohura N, Nakatsuka H, Qin K, Obi S, Kamiya A, Ando J. 2004. Differential regulation of urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression by fluid shear stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol 287:H2027–H2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung KE, Su X, Berthier E, Pehlke C, Friedl A, Beebe DJ. 2013. Understanding the Impact of 2D and 3D Fibroblast Cultures on In Vitro Breast Cancer Models. PLOS ONE 8:e76373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz MA, Lund AW. 2012. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12:210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L, Han X. 2013. The urokinase plasminogen activator system in breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 67:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafillu UL, Park S, Klaassen NL, Raddatz AD, Kim Y. 2017. Fluid shear stress induces cancer stem cell-like phenotype in MCF7 breast cancer cell line without inducing epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Oncol http://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ijo.2017.3865/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ulrich TA, Jain A, Tanner K, MacKay JL, Kumar S. 2010. Probing cellular mechanobiology in three-dimensional culture with collagen–agarose matrices. Biomaterials 31:1875–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich TA, Lee TG, Shon HK, Moon DW, Kumar S. 2011. Microscale mechanisms of agarose-induced disruption of collagen remodeling. Biomaterials 32:5633–5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendruscolo F, Rossi MJ, Schmidell W, Ninow JL. 2012. Determination of Oxygen Solubility in Liquid Media. Research article. Int. Sch. Res. Not https://www.hindawi.com/journals/isrn/2012/601458/.

- Wagner BA, Venkataraman S, Buettner GR. 2011. The rate of oxygen utilization by cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med 51:700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM, Glucksberg MR, Depaola N, Chang J, Grotberg JB. 1996. Shear stress alters pleural mesothelial cell permeability in culture. J. Appl. Physiol 81:448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BA. 2014. How Taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 25:2677–2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt B, Ghajar CM, Bissell MJ. 2014. The need for complex 3D culture models to unravel novel pathways and identify accurate biomarkers in breast cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 69–70. Innovative tissue models for drug discovery and development:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbaum S, Cowin SC, Zeng Y. 1994. A model for the excitation of osteocytes by mechanical loading-induced bone fluid shear stresses. J. Biomech 27:339–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K, Searson PC. 2011. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11:512–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong N, Li S, Tang K, Bai H, Peng Y, Yang H, Wu C, Liu Y. 2017. Involvement of caveolin-1 in low shear stress-induced breast cancer cell motility and adhesion: Roles of FAK/Src and ROCK/p-MLC pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Res 1864:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Guan L, Li S, Jiang Y, Xiong N, Li L, Wu C, Zeng H, Liu Y. 2016. Mechanosensitive caveolin-1 activation-induced PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway promotes breast cancer motility, invadopodia formation and metastasis in vivo. Oncotarget 7:16227–16247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Rabodzey A, Dewey CF. 2007. Glycocalyx modulates the motility and proliferative response of vascular endothelium to fluid shear stress. Am. J. Physiol. - Heart Circ. Physiol 293:H1023–H1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Li L, Guan L, Yang H, Wu C, Liu Y. 2014. Roles for GP IIb/IIIa and [alpha]v[beta]3 integrins in MDA-MB-231 cell invasion and shear flow-induced cancer cell mechanotransduction. Cancer Lett. 344:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.