Abstract

Backgrounds:

Autophagy and apoptosis are the basic physiological processes in cells that clean up aged and mutant cellular components or even the entire cells. Both autophagy and apoptosis are disrupted in most major diseases such as cancer and neurological disorders. Recently, increasing attention has been paid to understand the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis due to their tightly synergetic or opposite functions in several pathological processes.

Objective:

This study aims to assist autophagy and apoptosis-related drug research, clarify the intense and complicated connections between two processes, and provide a guide for novel drug development.

Method:

We established two chemical-genomic databases which are specifically designed for autophagy and apoptosis, including autophagy-and apoptosis-related proteins, pathways and compounds. We then performed network analysis on the apoptosis- and autophagy-related proteins and investigated the full protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of these two closely connected processes for the first time.

Results:

The overlapping targets we discovered show a more intense connection with each other than other targets in the full network, indicating a better efficacy potential for drug modulation. We also found that Death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) is a critical point linking autophagy-and apoptosis-related pathways beyond the overlapping part, and this finding may reveal some delicate signaling mechanism of the process. Finally, we demonstrated how to utilize our integrated computational chemogenomics tools on in silico target identification for small molecules capable of modulating autophagy- and apoptosis-related pathways.

Conclusion:

The knowledge-bases for apoptosis and autophagy and the integrated tools will accelerate our work in autophagy and apoptosis-related research and can be useful sources for information searching, target prediction, and new chemical discovery.

Keywords: Autophagy, apoptosis, cancer, neurological diseases, systems pharmacology, network analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is a process by which cells capture intracellular lipids, proteins and organelles, and transport them into lysosomes for degradation [1]. It is also known as a lysosomal degradative pathway with the character of the formation of double-membrane autophagic vesicles, also named autophagosomes. Autophagy is involved in many disease processes, and its loss or gain in function may contribute to pathogenesis [2].

Autophagy is believed to play an important role in cancer development. Lots of studies report a connection between carcinogenesis and decreased level of autophagy [3–6]. But in the late stage of cancer, autophagy can aid cancer cells to survive by overcoming nutrition shortage [7–9]. Because of the dual roles of autophagy, a single-agent use of inhibitor can result in different outcomes due to the functional existence of both damage cleaning and autophagic cell death (ACD) [10]. On the other hand, autophagy is essential for maintaining brain homeostasis. It is necessary for neurons to get rid of toxic aggregate-prone proteins [11]. Studies reported that instead of being relatively inactive, basal autophagy is relatively active in neurons for the clearance of abnormal proteins in the cytoplasm [12, 13]. However, both macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) are significantly becoming less efficient during the aging process [14]. Therefore, autophagy failure is one of the most popular concepts in explaining neuro-diseases’ mechanisms.

Mutations of autophagy-related genes are also associated with many diseases in different systems other than cancer and neuro-diseases. The genetic polymorphisms of ATG5 are associated with asthma [15, 16] and can enhance the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus [17, 18]. ATG16L1 mutation is associated with increased risk of Crohn’s disease [19–21], and BECN1 mutation is associated with risk and prognosis of human breast, ovarian, prostate, and colorectal cancers [22–26]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and deletion mutations in IRGM are associated with enhanced risk of Crohn’s disease [27–30]. PARK6/PINK1 mutations are associated with autosomal recessive or sporadic early- onset Parkinson’s disease [31–33]. SQSTM1/p62 mutations are associated with Paget disease of bone [34] and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [35–36], and WDR45/WIPI4 heterozygous mutations are associated with static encephalopathy in childhood and neurodegeneration in adulthood (SENDA) [37–38].

Apoptosis is also known as programmed cell death. The morphological changes during apoptosis include both the cytoplasm and nucleus alterations, which are interestingly similar across species and cell types. Apoptosis is understood to be a stress-induced process of cellular communication [39]. It is more likely to occur under conditions of cellular stress such as genetic damage or severe oxidative stress, which are relatively common in several diseases (like cancer) and their therapies.

The ability to evade apoptosis is one of the hallmarks of cancer cells [40]. Evasion of apoptosis may benefit tumor development, progression, and even resistance to treatment [41]. Cancer cells utilize a variety of mechanisms to evade apoptosis, and some are specific to certain cancer types while others are not. Generally, this evasion is supported by 1) an increased level of antiapoptotic molecules or decreased level of proapoptotic molecules [42]; 2) reduced signaling of a death receptor [43]; and 3) impaired caspase function [42].

Apoptosis is also important in neuron development. It controls the development process of different neuron cells in the developing brain and spinal cord [44]. However, under certain pathologic conditions like aging, apoptosis is also co-responsible for neuron loss. Although the exact mechanisms of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) are still unknown, the available data supported that the accumulation of Aβ peptide will lead to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and induce apoptosis [45]. Apoptosis is also thought to be the dominant mechanism for neurodegeneration in PD (Parkinson’s Disease) [46]. Abnormal and dysfunction in apoptosis-related genes are related to many diseases in the human body. Fas mutation links to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type I (ALPS I), malignant lymphoma and bladder cancer [47–48]; FASLG dysfunction leads to systemic lupus erythematodes [48–51]; Bax mutations lead to colon cancer [52–53] and hematopoietic malignancies [54]; and BIRC3 is related to low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma [55–56].

It is natural for us to think about the connection between autophagy and apoptosis when they always present under the same physiological conditions. Literature reported that autophagy and apoptosis can be triggered by the same upstream signals but end in different outcomes [57], which suggests multiple, delicate signaling connections between them. Studies also highlighted that some important proteins like TOR kinase and Beclin 1 play critical roles in connection [58–60], and the knockdown experiment of cross-talking protein shows a mediation function in decision making to autophagy or apoptosis [59]. It is well acknowledged that the autophagy and apoptosis processes not only work closely with each other, but also share a group of targets to conduct complicated decision making and transformation functions [61–62].

1.1. Crosstalk between Autophagy and Apoptosis

Both autophagy and apoptosis can induce cell death directly. However, autophagy can either inhibit or induce apoptosis under different cellular conditions. The relationship between autophagy and apoptosis at the functional level can be divided into three categories (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1). Relationship of autophagy and apoptosis at the functional level.

(A) Both autophagy and apoptosis are sufficient in inducing cell death. (B) Autophagy can promote apoptosis-induced cell death by promoting death-inducing signaling complexes (iDISC) or enhancing the degradation of negative regulators of apoptosis [63]. (C) Autophagy can also inhibit apoptosis-induced cell death by degradation of positive regulators of apoptosis such as p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) or by removal of damaged organelles and protein aggregates

Apoptosis interacts with autophagy in both its intrinsic (mitochondrial-mediated) and extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) pathways. Mitochondrial outer membrane perme-abilization (MOMP) is important in apoptosis intrinsic pathway since it controls the release of mitochondrial intermembrane proteins including the cytochrome c which will lead to caspase-9 activation, and it’s controlled by BCL-2 family proteins. For example, anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, Bcl-X, and Mcl-1, prevent the activation of pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Bak under basal cellular conditions [64]. In the aspect of autophagy, BCL2 family proteins prevent phagophore formation by inhibiting Atg14, Beclin-1, PI3K-II and P150. As such, the BCL-2 family proteins tightly connect autophagy and intrinsic apoptosis pathways (Fig. 2). In the extrinsic pathway, death ligands such as TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) have a significant role. However, autophagy-deficient cells are highly sensitive to TRAIL induced apoptosis [64]. Therefore, autophagy and apoptosis are not exclusive processes. They act either synergistically or antagonistically to maintain the homeostasis in cells. However, this balance is always disrupted during disease progression. Generally, autophagy is considered one of the cells’ survival mechanisms during cancer chemotherapeutics due to its attempts to remove damaged cellular components [10].

Fig. (2). BCL-2 family proteins in the cross talk.

Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1) inhibit both the autophagy and apoptosis initiation.

Though there are plenty of researchers trying to explain the connections between autophagy and apoptosis, a direct and complete protein-protein interaction map of the processes hasn’t been generated, making the study about the relationship between two processes in the struggle. The goal of this research is to build autophagy and apoptosis-specific chemogenomics databases and explore the connection between them by identifying the overlapping targets and associated drugs. The better collected and organized databases and target-interaction map should be helpful to better understand and study the mechanism of existing drugs and identify potential targets for the future study.

2. METHOD AND MATERIAL

2.1. Construction of Autophagy and Apoptosis Knowledgebases

The autophagy (http://www.cbligand.org/autophagy) and apoptosis (http://www.cbligand.org/apoptosis) knowledgebase were established based on the chemogenomics database AlzPlatform (www.CBLigand.org/AD) which was previously constructed by our group [65] with an Apache (http://www.apache.org/) web server and MySQL (http://www.mysql.com) database running at the back end. Autophagy and apoptosis-related protein targets and compounds were collected from different literature and databases, including Pub-Med (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) [66], PubChem (pub-chem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [67], Metacore (https://portal.genego.com/), DrugBank (http://www.drugbank.ca) [68], SciFinder (https://scifinder.cas.org/) [69], UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/) [70] and CHEMBL (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/) [71]. The corresponding X-ray crystallographic structures of these X-ray targets were acquired directly from RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org/pdb) [72] to construct the protein structure library. Signaling pathways for autophagy and apoptosis are acquired from KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) [73]. The associated bioassays for the target proteins, which were used to statistically validate our prediction, were collected from CHEMBL database.

We also adopted several systems pharmacological analysis tools in the database such as HTDocking [65], TargetHunter [74] and Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Predictor [65], which are instruments developed by our group.

In the following network analysis studies focused on the overlapping targets between autophagy and apoptosis, we incorporated the protein-protein interaction (PPI) data from STRING (https://string-db.org/) [75]. The interaction network was shown in the molecular action view with the medium confidence level.

2.2. Molecular Docking for the Validation and Systems Pharmacology Research

We performed the molecular docking between the crystal structures of proteins and ligands in the databases using Autodock Vina [76]. Water molecules, as well as ligands in the PDB crystal structure, were removed and hydrogens were added. The active binding site was defined by the interaction residue of the co-crystallized ligands or generated according to the reported literature. Autodock Vina provides us with 20 highest ranked poses for each ligand in a binding pocket by binding affinity values (ΔG values), and the docking score is calculated as pKi, where pKi = -log(predicted Ki) and the predicted Ki = exp(ΔG×1000/(r9871917×29815) 77.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Autophagy Related Protein Targets and Drugs

Autophagy knowledgebase (www.cbligand.org/ autophagy) archived 102 autophagy-related protein targets, 32 autophagy-related FDA-approved and clinical trial drugs, 10,971 target-associated chemicals, 137 related signaling pathways, 16,209 bioactivity records, and 13,326 references.

3.2. Apoptosis-related Protein Targets and Drugs

Apoptosis knowledgebase (www.cbligand.org/apoptosis) archived 456 apoptosis-related protein targets, 14 apoptosis-related FDA-approved and clinical trial drugs, 24,357 target-associated chemicals, 96 related signaling pathways, 12,756 bioactivity records, and 89,039 references.

3.3. Targets Overlap between Autophagy and Apoptosis

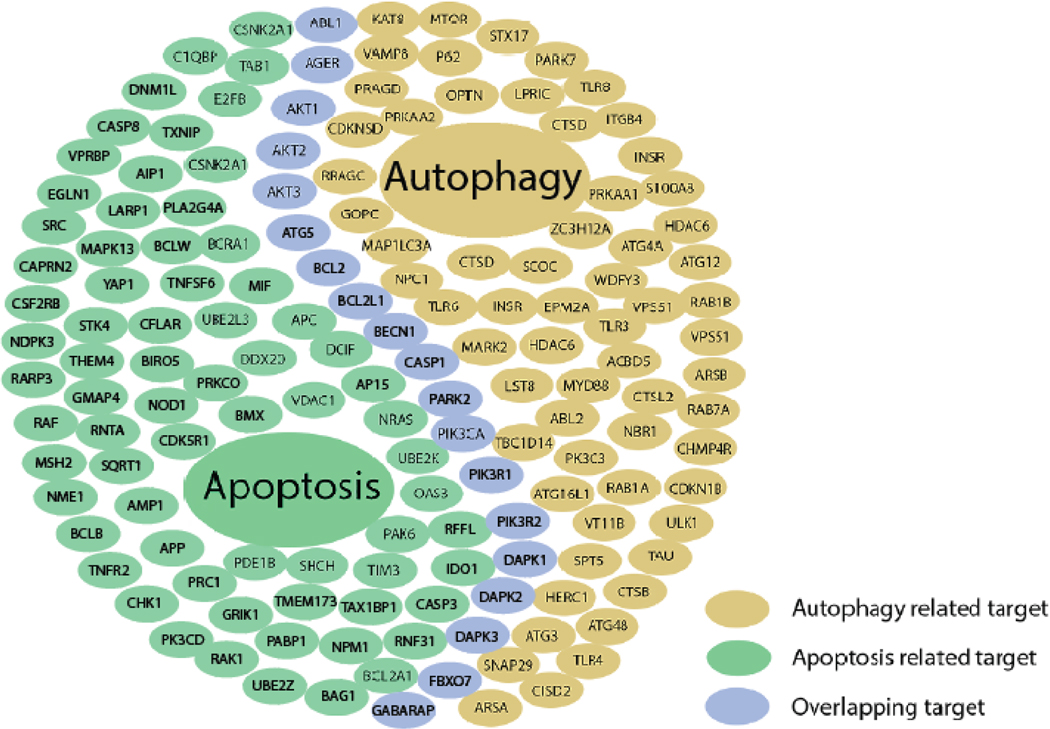

A total of 455 and 102 protein targets are summarized in the Apoptosis Knowledgebase and Autophagy Knowledgebase, respectively. Among these targets, 38 targets overlap. (Fig. 3).

Fig. (3). An illustration of apoptosis- and autophagy-related targets and their overlap.

Autophagy and apoptosis pathways share 38 targets function as a bridge between two processes transferring signals from one to another. This figure does not display the full set of the targets because there are too many. Please find the whole list of targets in supplementary material.

3.4. Network Analysis

To understand the connection of autophagy and apoptosis in a direct way, network analysis method was used to generate the whole protein-protein interaction (PPI) network for the two processes. Earlier studies suggest the method of identifying disease-related genes based on the network approach [78, 79], which provides a compromised view between extreme reductionism and the ‘knowledge of everything’ [80]. In network analysis, a small group of nodes with a higher number of neighbors than average in the overall network is called a hub, and the signal transfer deteriorates rapidly in most real-world networks and hubs can help maintain the signal strength. This property made hubs attractive drug targets [81].

To further take advantage of the databases we established, network analysis was performed in order to provide a view of the connection between two processes. The targets’ interaction network of two separate pathways was merged to provide an overview and the overlapping targets are studied with extra attention. The merged network provided a lot of information, just as we expected. To simplify the network for a better understanding, we calculated the interactions linked to each protein to see the weight and importance of them in the network. Furthermore, we incorporated the developing and approved drugs targeting the overlapping targets to provide a general view.

Fig. (4) shows the interactions of proteins in the whole processes of autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy and apoptosis pathways are connected through the overlapping targets and the connection may be affected by compounds and drugs. All the nodes are connected in an intensive manner and yield a PPI enrichment p-value less than 1.0×e−16, which means these proteins have more interactions among themselves than what would be expected for a random set of proteins of similar size drawn from the genome. But the overlapping part is even more condensed with an average local clustering coefficient of 0.656 in contrast to 0.454 and 0.633 for apoptosis and autophagy respectively, and this value for the full PPI network is 0.455 to compare. This indicates that the targets in the overlapping part do have more condense connections compared to other targets, possess a larger capability to alter the function of two processes and have bigger potential in the drug development aspect.

Fig. (4). The Full Interaction Map of Apoptosis- and Autophagy-related Drugs and Targets.

Full PPI network yields a PPI enrichment p-value < 1.0×e−16 and 0.455 for average local clustering coefficient, indicating that the proteins shown in the figure are more connected than a random set of proteins of similar size. DAPK1 (Death-associated protein kinase 1), colored in yellow, is found enjoying a critical position in the network as all connections pass through this node. This finding indicates a potential important modification function of DAPK 1.

Furthermore, there is an interesting finding beyond the overlapping area that although there are many connections between two processes, the only portal to influence the apoptosis processes is through the DAPK1 (Death-associated protein kinase 1), shown in yellow in the figure. DAPK1 is a well-studied protein and its role in apoptosis and autophagy is widely acknowledged [82–83], it can mediate autophagy and apoptosis by regulating related targets like STAT3, NF-κB and caspase-3 [84]. Lots of compounds were designed to interact with this protein but none of them made it to the market [85]. This phenomenon further illustrates the interesting role DAPK1 plays in the mechanism of a cell dealing with stress and raises a potential target for modulating apoptosis-and autophagy-related diseases.

It’s not a surprise that these targets are interacting extensively, as shown in Fig. (5a), where all the edges represent the interaction above a medium interaction score 0.4. Because of the limitations of current data, a lot of interactions’ directions cannot be determined. Thus, there is a possibility that these interactions will self-cancel themselves rather than work in the same direction. However, we can still speculate about the importance of the targets in the network according to the number of links connecting to them. The overlapping targets function as a bridge connecting and transferring signals between these two processes. As we can see from Fig. (5b), ABL1 (Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1), AKT1 (Serine/threonine-protein kinase akt-1), BCL2 (Bcl2-associated agonist of cell death), BCL2L1 (Bcl-2-like protein 1), BECN1 (beclin1), TP53 (Cellular tumor antigen p53), PIK3CA (Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform), and STK11 (Serine/ threonine-protein kinase STK11) contribute a lot for the network. Therefore, the drugs and compounds that can influence them will have a bigger impact on the whole system and further influence autophagy and apoptosis. Literature report that autophagy and apoptosis are two phases that the cell deals with stress and the dynamic relationship between the two processes is closely related to these overlapping targets and the pathways involved [86].

Fig. (5). Overlapping Protein-protein Interactions Analysis.

(a) PPI network of 38 overlapping targets and targeted drugs. (b) The interaction and compound count of each target of overlapping targets. The interactions data are counts from the merged PPI network of apoptosis and autophagy processes. The number of interactions connected to proteins could be a sign of the importance of the target in the network.

Furthermore, we can see an interesting phenomenon that drugs have avoided the most connected targets but focus instead on the medium-connected targets and low-connected targets like HTR2B (5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B) and PIM2 (Serine/threonine-protein kinase pim-2). This may be because in the aspect of identifying good targets for drug development, involving too many pathways may be an indicator for more unnecessary side effects, which makes the targets not druggable. The targets with rather simple connections are easier to predict the effect of when influenced by chemicals and are thus preferred in drug development. The drugs shown in Fig. (5a) are a mixture of discontinued, developing and approved drugs, but they all function as inhibitors to their targets. Many of these drugs, like Docetaxel, Aripiprazole and Thalidomide, were reported to have regulatory effects on apoptosis and autophagy, and these drugs have been applied in the treatment therapy of schizophrenia and cancer with an outstanding performance [87–89]. This suggests that other overlapping targets can possess potentials similar to those that have been developed successfully.

This figure can also give us insight into the aspect of drug design and discovery to focus on the well-connected targets like BECN1, which have no targeted drug. The relationships between these targets and the directions of the interactions play a critical role when we try to understand the dynamic transformation of autophagy and apoptosis during dealing with stresses. Developing compounds and drugs can affect this transformation can own a signature therapeutic usage in neurological diseases and cancer to move this process in the direction we desire.

4. CASE STUDY

As mentioned above, the goal of the establishment of these databases is to facilitate studies of autophagy and apoptosis-related mechanisms and targets. This goal can be accomplished by incorporating systems pharmacology tools with the results of the databases. Following are two case studies demonstrating the ways how the databases can be used as great instruments and resources in identifying new targets and studying drug mechanisms.

4.1. Case Study 1: Prediction and Experiment Validation of Bcl-xL as an Apoptosis-inducing Target of a Novel Compound

In silicon targets identification of small molecules is the fundamental function of our databases which is essential for unraveling the underlying drug mechanisms. We use a novel compound named CHEMBL376055 as an example to illustrate how the databases can help in identifying targets and exploring mechanisms. Based on the literature reports, it binds to Bcl-xL with Ki of 638 nM and is highly effective in induction of cell death in breast cancer cells [90]. We uploaded the compound structures to the docking study section in the databases and ran the docking procedure. The results show that the compound is predicted to have a great binding affinity with NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-2, Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 proteins. The Bcl-xL proteins were ranked with the second highest docking score of 10.2, suggesting they are highly likely to be the key targets of this compound. A more detailed docking study was performed using Maestro Glide to further validate the predicted interactions between the compound and Bcl-xL (PDB ID 3QKD Chain A) as shown in Fig. (6a) and the planar interactions shown in Fig. (6b). The docking score of CHEMBL376055 and protein is 8.32 and is acceptable. The compound shows three hydrogen bonds (ARG139, ASN136, and GLY138) and one pi-pi stacking interaction (TYR101) with residues of the protein which further validate the possibility of Bcl-xL as a target for the compound.

Fig. (6). Docking Study of CHEMBL376055 in the ligand binding pocket of Bcl-xL.

(a) Predicted binding pose and residue interaction of CHEMBL376055 and Bcl-xL crystal structure PDB ID 3QKD Chain A (docking score 8.32). (b) 2D molecular interaction graph.

4.2. Case Study 2: The Prediction of Pharmacology of Known Apoptosis-related Drugs for Targets Identification

Statins have been discussed and studied over their ability to alter the expression of anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins [91]. As Bcl-2 family proteins play a crucial role in apoptosis and cell death, the statin induced reduction in Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL and increase in Bax support a pro-apoptotic outcome [92]. However, how statins alter the expression of Bcl-2 remains unclear. Literature reports that endothelin-1 (ET-1) can increase Bcl-2 abundance via the nuclear transcription factors of activated thymocytes (NFATc) and simvastatin can increase ET-1 gene expression whose products is the precursor of ET-1 protein [93–94]. In order to make a prediction of the potential target of statins, we uploaded the structure of simvastatin to the databases. The result reported several potential targets with high docking scores, which indicate a high likelihood of binding between simvastatin and these proteins.

Fig. (7 and 8) exhibit the detailed docking result of simvastatin and the top two ranked proteins. The binding between simvastatin and Apoptosis-inducing factor 1(AIF, PDB ID 4bur) is quite interesting because the binding site of the protein is divided into two major pockets, of which either one of them can contain the ligand well. But the highest 20 ranks are all located in the deeper positions in the pocket. The binding between simvastatin and Apoptosis-inducing factor 1 yields a docking score of 10.6 and forms hydrogen bonds with residue ASP271, ARG285, GLU314, LYS177, and LYS176. The binding between simvastatin and Tyro-sine-protein kinase ABL1 yields a docking score of 9.9 and forms hydrogen bonds with residue PHE401, LYS290, THR334, and GLY402. Both results further confirm the high possibility of binding. There are reports that show that binding with Apoptosis-inducing factor 1 is essential for inducing cell death in several cell types by preventing the release of the factor that can inhibit caspase-independent apoptosis [100, 101]. Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 is also a critical target in apoptosis pathways and was reported as a popular target for apoptosis-related studies [102, 103]. The prediction of the databases and binding results matches the observed effect of simvastatin in the literature report.

Fig. (7). Docking Study of Simvastatin in the ligand binding pocket of mitochondrial Apoptosis-inducing factor 1 AIF1.

Predicted binding pose and residue interaction of Simvastatin and Apoptosis-inducing factor 1 (PDB ID 4bur, docking score 10.6).

Fig. (8). Docking Study of Simvastatin in the ligand binding pocket of Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1.

Predicted binding pose and residue interaction of Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 (PDB ID 2g2h, docking score 9.9).

5. DISCUSSION

As discussed in the introduction section, both autophagy and apoptosis are basic but critical in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. The disruption of either autophagy or apoptosis is considered one of the major contributors to cancer and neurological disorders. Most of the drugs now in the market are thought to interact with autophagy and apoptosis either by a direct signaling cascade or an indirect functional regulation. However, this can be particularly challenging when the desired regulations of autophagy and apoptosis by medications are in opposite directions. Specifically, one drug may inhibit the growth of cancer in the aspect of apoptosis but facilitate cancer survival at the same time in the aspect of autophagy. Therefore, specific knowledgebases for autophagy and apoptosis are expected to be beneficial for research related to cancer and neurological disease.

With the construction of the autophagy-apoptosis specific knowledgebases in this work, one can have a specific overview of autophagy and apoptosis from the molecular signaling level to the chemical level. These knowledgebases integrate several systems pharmacological analysis tools including, but not limit to; HTDocking, BBB predictor, PAINS remover, and Toxicity predictor, which will further accelerate the autophagy-apoptosis related research by using the information collected in the knowledgebase. Several shared protein targets between autophagy and apoptosis are also revealed by the overlapping study between these two knowledge bases. These targets are incredibly important due to their potential dual functions in the diseases and disease- related treatment. Researchers who plan to treat the diseases by manipulating the autophagy or apoptosis function can take great benefit from these knowledge bases, either through the information searching or the target prediction.

Several autophagy or apoptosis-related databases are now available online, with popular ones including but not limited to the iLIR Autophagy Database (http://ilir.warwick.ac.uk/) [104], Human Autophagy Database (http://www.auto-phagy.lu/) [69, 105], Deathbase (http://www.deathbase.org/) [106], and The Apoptosis Database (http://www.apoptosis-db.org) [107]. All of these public databases serve as good information portals for searching autophagy-apoptosis related proteins, pathways, and gene information. Compared to these databases, the knowledgebases reported in this paper contain not only the autophagy-apoptosis related information but also some practical tools for cheminformatics research. This will grant the researchers more convenience when conducting the autophagy- and apoptosis-related drug development.

However, limitations remain in this study. Identification of novel targets is a hot topic and it may come from various sources, and most of them are hard to verify because it takes a long time and become a combined results of different approaches. As a matter of fact, up to 50% published data from academia cannot be reproduced in industry [108]. The contents of our databases will be enlarged and the results of the systems pharmacology tools will be further tested in the future study.

With the help of the databases and tools included, we are able to get a clearer insight about the connection between autophagy and apoptosis. The interaction network among targets indicates a delicate signaling pathway that leads to the mechanism of cell deal with stress which can be helpful in multiple diseases like cancer and neuro degenerative diseases. Furthermore, the result of the network analysis also provides directions and potential targets for novel drug design and discovery of the unclear mechanism of existing drugs.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we established two knowledgebases which are specifically designed for autophagy or apoptosis by collecting the related gene, protein, and chemical data with several cheminformatics tools integrated. We used our knowledgebase to review the important drug targets in autophagy and apoptosis research paired with their known chemical modulators in the clinical studies. Target overlap study was also conducted based on these knowledgebases to investigate the potential interactions between autophagy and apoptosis. The result of network analysis shows a very inspiring and promising hint for a future study. Target prediction function was also implemented into these knowledgebases by using the open-source algorithm and the proper protein structure subsets. Overall, the Autophagy Knowledgebase and the Apoptosis Knowledgebase will accelerate our work in acquiring disease-specific information and could be a useful tool for predicting the potential targets for future medications.

Supplementary Material

Apoptosis related targets list.

Autophagy related targets list.

Table 1.

Predicted result for simvastatin.

| PDB ID Chain | Protein | Docking Score |

|---|---|---|

| 4bur_A [95] | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 10.6 |

| 2g2h_A [96] | Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL1 | 9.9 |

| 4lii_A | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 9.8 |

| 4bv6_A [95] | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 9.7 |

| 5fs9_A [97] | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 9.7 |

| 2z7x_A [98] | Toll-like receptor 2 | 9.6 |

| 5fs7_A [97] | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 9.6 |

| 5fs8_A [97] | Apoptosis-inducing factor 1, mitochondrial | 9.6 |

| 2xm8_A [99] | Serine/threonine-protein kinase Chk2 | 9.6 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to acknowledge the funding supports to the Xie laboratory from the NIH NIDA (P30 DA035778A1), and DOD (W81XWH-16–1-0490).

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publishers web site along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- [1].Levine B;Kroemer G,Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 2008, 132 (1), 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kroemer G,Autophagy: a druggable process that is deregulated in aging and human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125 (1), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schwarze PE; Seglen PO, Reduced autophagic activity, improved protein balance and enhanced in vitro survival of hepatocytes isolated from carcinogen-treated rats. Experimental cell research 1985, 157 (1), 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Komatsu M;Waguri S;Koike M;Sou Y-s.; Ueno T;Hara T;Mizushima N;Iwata J-i.; Ezaki J;Murata S,Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell 2007, 131 (6), 1149–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Komatsu M;Waguri S;Ueno T;Iwata J;Murata S;Tanida I;Ezaki J;Mizushima N;Ohsumi Y;Uchiyama Y,Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2005, 169 (3), 425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mathew R;Karp CM; Beaudoin B;Vuong N;Chen G;Chen H-Y; Bray K;Reddy A;Bhanot G;Gelinas C,Autophagy suppresses tumorigenesis through elimination of p62. Cell 2009, 137 (6), 1062–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Degenhardt K;Mathew R;Beaudoin B;Bray K;Anderson D;Chen G;Mukherjee C;Shi Y;Gélinas C;Fan Y,Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer cell 2006, 10 (1), 5l–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lum JJ; Bauer DE; Kong M;Harris MH; Li C;Lindsten T;Thompson CB, Growth factor regulation of autophagy and cell survival in the absence of apoptosis. Cell 2005, 120 (2), 237248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kuma A;Hatano M;Matsui M;Yamamoto A,The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 2004, 432 (7020), 1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mohammad RM; Muqbil I;Lowe L;Yedjou C;Hsu H-Y; Lin L-T; Siegelin MD; Fimognari C;Kumar NB; Dou QP In Broad targeting of resistance to apoptosis in cancer, Seminars in cancer biology, Elsevier: 2018; pp S78–S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Levine B;Kroemer G,Autophagy in aging, disease and death: the true identity of a cell death impostor. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hara T;Nakamura K;Matsui M;Yamamoto A;Nakahara Y;Suzuki-Migishima R;Yokoyama M;Mishima K;Saito I;Okano H,Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 2006, 441 (7095), 885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Komatsu M;Waguri S;Chiba T;Murata S;Iwata J-i.; Tanida I;Ueno T;Koike M;Uchiyama Y;Kominami E,Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 2006, 441 (7095), 880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Martinez-Vicente M;Sovak G;Cuervo AM, Protein degradation and aging. Experimental gerontology 2005, 40 (8), 622–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Martin LJ; Gupta J;Jyothula SS; Kovacic MB; Myers JMB; Patterson TL; Ericksen MB; He H;Gibson AM; Baye TM, Functional variant in the autophagy-related S gene promotor is associated with childhood asthma. PloS one 2012, 7 (4), e334S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Poon A;Eidelman D;Laprise C;Hamid Q,ATGS, autophagy and lung function in asthma. Autophagy 2012, 8 (4), 694–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhou X.-j.; Lu X-l.; Lv J.-c.; Yang H-z.; Qin L.-x.; Zhao M.- h.; Su Y;Li Z.-g.; Zhang H,Genetic association of PRDM1-ATGS intergenic region and autophagy with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese population. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70 (7), 1330–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pierdominici M;Vomero M;Barbati C;Colasanti T;Maselli A;Vacirca D;Giovannetti A;Malorni W;Ortona E,Role of autophagy in immunity and autoimmunity, with a special focus on systemic lupus erythematosus. The FASEB Journal 2012, 26 (4), 1400–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hampe J;Franke A;Rosenstiel P;Till A;Teuber M;Huse K;Albrecht M;Mayr G;De La Vega FM; Briggs J,A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39 (2), 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rioux JD; Xavier RJ; Taylor KD; Silverberg MS; Goyette P;Huett A;Green T;Kuballa P;Barmada MM; Datta LW, Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39 (5), S96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Barrett JC; Hansoul S;Nicolae DL; Cho JH; Duerr RH; Rioux JD; Brant SR; Silverberg MS; Taylor KD; Barmada MM, Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40 (8), 955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Saito H;Inazawa J;Saito S;Kasumi F;Koi S;Sagae S;Kudo R;Saito J;Noda K;Nakamura Y,Detailed deletion mapping of chromosome l7q in ovarian and breast cancers: 2-cM region on l7q2l.3 often and commonly deleted in tumors. Cancer research 1993, 53 (14), 3382–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gao X;Zacharek A;Salkowski A;Grignon DJ; Sakr W;Porter AT; Honn KV, Loss of heterozygosity of the BRCA1 and other loci on chromosome 17q in human prostate cancer. Cancer research 1995, 55 (5), 1002–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Aita VM; Liang XH; Murty VV; Pincus DL; Yu W;Cayanis E;Kalachikov S;Gilliam TC; Levine B,Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics 1999, 59 (1), 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liang XH; Jackson S;Seaman M;Brown K;Kempkes B;Hibshoosh H;Levine B,Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999, 402 (6762), 672–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koukourakis MI; Giatromanolaki A;Sivridis E;Pitiakoudis M;Gatter KC; Harris AL, Beclin 1 over- and underexpression in colorectal cancer: distinct patterns relate to prognosis and tumour hypoxia. British journal of cancer 2010, 103 (8), 1209–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Parkes M;Barrett JC; Prescott NJ; Tremelling M;Anderson CA; Fisher SA; Roberts RG; Nimmo ER; Cummings FR; Soars D;Drummond H;Lees CW; Khawaja SA; Bagnall R;Burke DA; Todhunter CE; Ahmad T;Onnie CM; McArdle W;Strachan D;Bethel G;Bryan C;Lewis CM; Deloukas P;Forbes A;Sanderson J;Jewell DP; Satsangi J;Mansfield JC; Cardon L;Mathew CG, Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nature genetics 2007, 39 (7), 830–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McCarroll SA; Huett A;Kuballa P;Chilewski SD; Landry A;Goyette P;Zody MC; Hall JL; Brant SR; Cho JH; Duerr RH; Silverberg MS; Taylor KD; Rioux JD; Altshuler D;Daly MJ; Xavier RJ, Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn’s disease. Nature genetics 2008, 40 (9), 1107–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brest P;Lapaquette P;Souidi M;Lebrigand K;Cesaro A;Vouret-Craviari V;Mari B;Barbry P;Mosnier JF; He-buterne X;Harel-Bellan A;Mograbi B;Darfeuille-Michaud A;Hofman P,A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xenophagy in Crohn’s disease. Nature genetics 2011, 43 (3), 242–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Barrett JC; Hansoul S;Nicolae DL; Cho JH; Duerr RH; Rioux JD; Brant SR; Silverberg MS; Taylor KD; Barmada MM; Bitton A;Dassopoulos T;Datta LW; Green T;Griffiths AM; Kistner EO; Murtha MT; Regueiro MD; Rotter JI; Schumm LP; Steinhart AH; Targan SR; Xavier RJ; Libioulle C;Sandor C;Lathrop M;Belaiche J;Dewit O;Gut I;Heath S;Laukens D;Mni M;Rutgeerts P;Van Gossum A;Zelenika D;Franchimont D;Hugot JP; de Vos M;Vermeire S;Louis E;Cardon LR; Anderson CA; Drummond H;Nimmo E;Ahmad T;Prescott NJ; Onnie CM; Fisher SA; Marchini J;Ghori J;Bumpstead S;Gwilliam R;Tremelling M;Deloukas P;Mansfield J;Jewell D;Satsangi J;Mathew CG; Parkes M;Georges M;Daly MJ, Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nature genetics 2008, 40 (8), 955–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Trinh J;Farrer M,Advances in the genetics of Parkinson disease. Nature reviews. Neurology 2013, 9 (8), 445–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Valente EM; Abou-Sleiman PM; Caputo V;Muqit MM; Harvey K;Gispert S;Ali Z;Del Turco D;Bentivoglio AR; Healy DG; Albanese A;Nussbaum R;Gonzalez-Maldonado R;Deller T;Salvi S;Cortelli P;Gilks WP; Latchman DS; Harvey RJ; Dallapiccola B;Auburger G;Wood NW, Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science 2004, 304 (5674), 1158–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Valente EM; Bentivoglio AR; Dixon PH; Ferraris A;Ia-longo T;Frontali M;Albanese A;Wood NW, Localization of a novel locus for autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism, PARK6, on human chromosome 1p35-p36. American journal of human genetics 2001, 68 (4), 895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Laurin N;Brown JP; Morissette J;Raymond V,Recurrent Mutation of the Gene Encoding sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1/p62) in Paget Disease of Bone. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2002, 70 (6), 1582–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hirano M;Nakamura Y;Saigoh K;Sakamoto H;Ueno S;Isono C;Miyamoto K;Akamatsu M;Mitsui Y;Kusunoki S,Mutations in the gene encoding p62 in Japanese patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2013, 80 (5), 458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rubino E;Rainero I;Chio A;Rogaeva E;Galimberti D;Fenoglio P;Grinberg Y;Isaia G;Calvo A;Gentile S;Bruni AC; St George-Hyslop PH; Scarpini E;Gallone S;Pinessi L,SQSTM1 mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2012, 79 (15), 1556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Haack TB; Hogarth P;Kruer MC; Gregory A;Wieland T;Schwarzmayr T;Graf E;Sanford L;Meyer E;Kara E;Cuno SM; Harik SI; Dandu VH; Nardocci N;Zorzi G;Dunaway T;Tarnopolsky M;Skinner S;Frucht S;Hanspal E;Schrander-Stumpel C;Heron D;Mignot C;Garavaglia B;Bhatia K;Hardy J;Strom TM; Boddaert N;Houlden HH; Kurian MA; Meitinger T;Prokisch H;Hayflick SJ, Exome sequencing reveals de novo WDR45 mutations causing a phenotypically distinct, X-linked dominant form of NBIA. American journal of human genetics 2012, 91 (6), 1144–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Saitsu H;Nishimura T;Muramatsu K;Kodera H;Kumada S;Sugai K;Kasai-Yoshida E;Sawaura N;Nishida H;Hoshino A;Ryujin F;Yoshioka S;Nishiyama K;Kondo Y;Tsurusaki Y;Nakashima M;Miyake N;Arakawa H;Kato M;Mizushima N;Matsumoto N,De novo mutations in the autophagy gene WDR45 cause static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood. Nature genetics 2013, 45 (4), 445–9, 449e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jean Y,Nucleo-cytoplasmic communication in apoptotic response to genotoxic and inflammatory stress. Cell research 2005, 15 (1), 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hanahan D;Weinberg RA, The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100 (1), 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Johnstone RW; Ruefli AA; Lowe SW, Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell 2002, 108 (2), 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Igney FH e. a., Death and anti-death: Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev. Cancer. 2002, 2, 277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ashkenazi A;Dixit VM, Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science 1998, 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ghavami S;Shojaei S;Yeganeh B;Ande SR; Jangamreddy JR; Mehrpour M;Christoffersson J;Chaabane W;Moghadam AR; Kashani HH, Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Progress in neurobiology 2014, 112, 24–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lustbader JW; Cirilli M;Lin C;Xu HW; Takuma K;Wang N;Caspersen C;Chen X;Pollak S;Chaney M,ABAD directly links Aß to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science 2004, 304 (5669), 448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kountouras J;Zavos C;Polyzos S;Deretzi G;Vardaka E;Giartza-Taxidou E;Katsinelos P;Rapti E;Chatzopoulos D;Tzilves D,Helicobacter pylori infection and Parkinson’s disease: apoptosis as an underlying common contributor. European journal of neurology 2012, 19 (6), e56–e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ashkenazi A;Dixit VM, Death Receptors: Signaling and Modulation. Science 1998, 281 (5381), 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Peter ME; Krammer PH, Mechanisms of CD95 (APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Immunol 1998, 10 (5), 545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].O’Connell J;Bennett MW; O’Sullivan GC; Collins JK; Shanahan F,Fas counter-attack-the best form of tumor defense? Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pinkoski MJ; Green DR, Fas ligand, death gene. Cell Death Differ. 1999, 6, 1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nagata S,Fas Ligand-Induced Apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999, 33 (1), 29–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shin MS; Park WS; Kim SY; Kim HS; Kang SJ; Song KY; Park JY; Dong SM; Pi JH; Oh RR; Lee JY; Yoo NJ; Lee SH, Alterations of Fas (Apo-1/CD95) Gene in Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. The American Journal of Pathology 1999, 154 (6), 1785–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yamamoto H;Gil J;Schwartz S;Perucho M,Frameshift mutations in Fas, Apaf-1, and Bcl-10 in gastro-intestinal cancer of the microsatellite mutator phenotype. Cell Death Differ. 2000, 7, 238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Müllauer L;Gruber P;Sebinger D;Buch J;Wohlfart S;Chott A,Mutations in apoptosis genes: a pathogenetic factor for human disease. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2001, 488 (3), 211–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Baens M;Maes B;Steyls A;Geboes K;Marynen P;De Wolf-Peeters C,The Product of the t(11;18), an API2-MLT Fusion, Marks Nearly Half of Gastric MALT Type Lymphomas without Large Cell Proliferation. The American Journal of Pathology 2000, 156 (4), 1433–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Rosenwald A;Ott G;Stilgenbauer S;Kalla J;Bredt M;Katzenberger T;Greiner A;Ott MM; Gawin B;Döhner H;Müller-Hermelink HK, Exclusive Detection of the t(11;18)(q21;q21) in Extranodal Marginal Zone B Cell Lymphomas (MZBL) of MALT Type in Contrast to other MZBL and Extranodal Large B Cell Lymphomas. The American Journal of Pathology 1999, 155 (6), 1817–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Maiuri MC; Zalckvar E;Kimchi A;Kroemer G,Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2007, 8 (9), 741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Nikoletopoulou V;Markaki M;Palikaras K;Tavernarakis N,Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2013, 1833 (12), 3448–3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Liang J;Shao SH; Xu Z-X; Hennessy B;Ding Z;Larrea M;Kondo S;Dumont DJ; Gutterman JU; Walker CL; Slingerland JM; Mills GB, The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27kip1 phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Salminen A;Kaarniranta K;Kauppinen A,Beclin 1 interactome controls the crosstalk between apoptosis, autophagy and in-flammasome activation: impact on the aging process. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12 (2), 520–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lockshin RA; Zakeri Z,Apoptosis, autophagy, and more. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2004, 36 (12), 2405–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gordy C;He Y-W, The crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: where does this lead? Protein & cell 2012, 3 (1), 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fan Y-J; Zong W-X, The cellular decision between apoptosis and autophagy. Chin. J. Cancer 2013, 32 (3), 121–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Fitzwalter BE; Thorburn A,Recent insights into cell death and autophagy. FEBSjournal 2015, 282 (22), 4279–4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Liu H;Wang L;Lv M;Pei R;Li P;Pei Z;Wang Y;Su W;Xie X-Q, AlzPlatform: an Alzheimer’s disease domain-specific chemogenomics knowledgebase for polypharmacology and target identification research. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2014, 54 (4), 1050–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45 (D1), D12–d17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kim S;Thiessen PA; Bolton EE; Chen J;Fu G;Gindulyte A;Han L;He J;He S;Shoemaker BA; Wang J;Yu B;Zhang J;Bryant SH, PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44 (Database issue), D1202-D1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wishart DS; Feunang YD; Guo AC; Lo EJ; Marcu A;Grant JR; Sajed T;Johnson D;Li C;Sayeeda Z;Assempour N;Iynkkaran I;Liu Y;Maciejewski A;Gale N;Wilson A;Chin L;Cummings R;Le D;Pon A;Knox C;Wilson M,DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46 (D1), D1074-d1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ridley DD, Information Retrieval: SciFinder and SciFinder Scholar. John Wiley & Sons: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [70].The UniProt Consortium, UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45 (D1), D158–D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bento AP; Gaulton A;Hersey A;Bellis LJ; Chambers J;Davies M;Krüger FA; Light Y;Mak L;McGlinchey S;Nowotka M;Papadatos G;Santos R;Overington JP, The ChEMBL bioactivity database: an update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42 (D1), D1083-D1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Berman HM; Westbrook J;Feng Z;Gilliland G;Bhat TN; Weissig H;Shindyalov IN; Bourne PE, The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28 (1), 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kanehisa M;Goto S,KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2000, 28 (1), 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chen S;Rehman SK; Zhang W;Wen A;Yao L;Zhang J,Autophagy is a therapeutic target in anticancer drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1806 (2), 220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Jensen LJ; Kuhn M;Stark M;Chaffron S;Creevey C;Muller J;Doerks T;Julien P;Roth A;Simonovic M;Bork P;von Mering C,STRING 8-- a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37 (Database issue), D412–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Trott O;Olson AJ, AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry 2010, 31 (2), 455–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wang N;Wang L;Xie X-Q, ProSelection: A Novel Algorithm to Select Proper Protein Structure Subsets for in Silico Target Identification and Drug Discovery Research. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2017, 57 (11), 2686–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Krauthammer M;Kaufmann CA; Gilliam TC; Rzhetsky A,Molecular triangulation: Bridging linkage and molecular-network information for identifying candidate genes in Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101 (42), 15148–15153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Csermely P;Korcsmaros T;Kiss HJ; London G;Nussinov R,Structure and dynamics of molecular networks: a novel paradigm of drug discovery: a comprehensive review. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2013, 138 (3), 333–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Huang S;Ernberg I;Kauffman S,Cancer attractors: A systems view of tumors from a gene network dynamics and developmental perspective. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 2009, 20 (7), 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Albert R;Jeong H;Barabási A-L, Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 2000, 406, 378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Singh P;Ravanan P;Talwar P,Death Associated Protein Kinase 1 (DAPK1): A Regulator of Apoptosis and Autophagy. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 2016, 9, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Yoo HJ; Byun HJ; Kim BR; Lee KH; Park SY; Rho SB, DAPk1 inhibits NF-kappaB activation through TNF-alpha and INF-gamma-induced apoptosis. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24 (7), 1471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Wu B;Yao H;Wang S;Xu R,DAPK1 modulates a curcumin-induced G2/M arrest and apoptosis by regulating STAT3, NF-kappaB, and caspase-3 activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 434 (1), 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Tian X;Xu L;Wang P,MiR-191 inhibits TNF-alpha induced apoptosis of ovarian endometriosis and endometrioid carcinoma cells by targeting DAPK1. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2015, 8 (5), 4933–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Jiang P;Mizushima N,Autophagy and human diseases. Cell research 2014, 24 (1), 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Makhov P;Kutikov A;Golovine K;Uzzo RG; Canter DJ; Kolenko VM, Docetaxel-mediated apoptosis in myeloid progenitor TF-1 cells is mitigated by zinc: potential implication for prostate cancer therapy. Prostate 2011, 71 (13), 1413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ergun MA; Konac E;Erbas D;Ekmekci A,Apoptosis and nitric oxide release induced by thalidomide, gossypol and dexamethasone in cultured human chronic myelogenous leukemic K-562 cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2004, 28 (3), 237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Abekawa T;Ito K;Nakagawa S;Nakato Y;Koyama T,Effects of aripiprazole and haloperidol on progression to schizophrenia-like behavioural abnormalities and apoptosis in rodents. Schizophrenia research 2011, 125 (1), 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Tang G;Yang C-Y; Nikolovska-Coleska Z;Guo J;Qiu S;Wang R;Gao W;Wang G;Stuckey J;Krajewski K;Jiang S;Roller PP; Wang S,Pyrogallol-Based Molecules as Potent Inhibitors of the Antiapoptotic Bcl-2 Proteins. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2007, 50 (8), 1723–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Wood WG; Igbavboa U;Muller WE; Eckert GP, Statins, Bcl-2 and Apoptosis: Cell Death or Cell Protection? Mol. Neuro- biol. 2013, 48 (2), 308–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Blanco-Colio LM; Villa A;Ortego M;Hernandez-Presa MA; Pascual A;Plaza JJ; Egido J,3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, atorvastatin and simvastatin, induce apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells by downregulation of Bcl-2 expression and Rho A prenylation. Atherosclerosis 2002, 161 (1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Johnson-Anuna LN; Eckert GP; Keller JH; Igbavboa U;Franke C;Fechner T;Schubert-Zsilavecz M;Karas M;Muller WE; Wood WG, Chronic administration of statins alters multiple gene expression patterns in mouse cerebral cortex. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 312 (2), 786–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Kawamura T;Ono K;Morimoto T;Akao M;Iwai-Kanai E;Wada H;Sowa N;Kita T;Hasegawa K,Endothelin-1-dependent nuclear factor of activated T lymphocyte signaling associates with transcriptional coactivator p300 in the activation of the B cell leukemia-2 promoter in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 2004, 94 (11), 1492–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Ferreira P;Villanueva R;Martinez-Julvez M;Herguedas B;Marcuello C;Fernandez-Silva P;Cabon L;Hermoso JA; Lostao A;Susin SA; Medina M,Structural insights into the coenzyme mediated monomer-dimer transition of the pro-apoptotic apoptosis inducing factor. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2014, 53 (25), 4204–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Levinson NM; Kuchment O;Shen K;Young MA; Koldob-skiy M;Karplus M;Cole PA; Kuriyan J,A Src-like inactive conformation in the abl tyrosine kinase domain. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4 (5), e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sevrioukova IF, Structure/Function Relations in AIFM1 Variants Associated with Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428 (18), 3650–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Jin MS; Kim SE; Heo JY; Lee ME; Kim HM; Paik SG; Lee H;Lee JO, Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell 2007, 130 (6), 1071–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Caldwell JJ; Welsh EJ; Matijssen C;Anderson VE; Antoni L;Boxall K;Urban F;Hayes A;Raynaud FI; Rigoreau LJ; Raynham T;Aherne GW; Pearl LH; Oliver AW; Garrett MD; Collins I,Structure-based design of potent and selective 2-(quinazolin-2-yl)phenol inhibitors of checkpoint kinase 2. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (2), 580–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Wang D;Liang J;Zhang Y;Gui B;Wang F;Yi X;Sun L;Yao Z;Shang Y,Steroid receptor coactivator-interacting protein (SIP) inhibits caspase-independent apoptosis by preventing apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from being released from mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (16), 12612–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].He Y;Li B;Zhang H;Luo C;Shen S;Tang J;Chen J;Gu L,L-asparaginase induces in AML U937 cells apoptosis via an AIF-mediated mechanism. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition) 2014, 19, 515–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Klener P;Klener P Jr., [ABL1, SRC and other non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases as new targets for specific anticancer therapy]. Klinicka onkologie : casopis Ceske a Slovenske onkologicke spolecnosti 2010, 23 (4), 203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Dasgupta Y;Koptyra M;Hoser G;Kantekure K;Roy D;Gornicka B;Nieborowska-Skorska M;Bolton-Gillespie E;Cerny-Reiterer S;Muschen M;Valent P;Wasik MA; Richardson C;Hantschel O;van der Kuip H;Stoklosa T;Skorski T,Normal ABL1 is a tumor suppressor and therapeutic target in human and mouse leukemias expressing oncogenic ABL1 kinases. Blood 2016, 127 (17), 2131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Kalvari I;Tsompanis S;Mulakkal NC; Osgood R;Johansen T;Nezis IP; Promponas VJ, iLIR: A web resource for prediction of Atg8-family interacting proteins. Autophagy 2014, 10 (5), 913–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Moussay E;Kaoma T;Baginska J;Muller A;Van Moer K;Nicot N;Nazarov PV; Vallar L;Chouaib S;Berchem G,The acquisition of resistance to TNFα in breast cancer cells is associated with constitutive activation of autophagy as revealed by a transcriptome analysis using a custom microarray. Autophagy 2011, 7 (7), 760–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Diez J;Walter D;Munoz-Pinedo C;Gabaldón T,DeathBase: a database on structure, evolution and function of proteins involved in apoptosis and other forms of cell death. Nature Publishing Group: 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Doctor K;Reed J;Godzik A;Bourne P,The apoptosis database. Cell Death & Differentiation 2003, 10 (6), 621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Hutson PH; Clark JA; Cross AJ, CNS Target Identification and Validation: Avoiding the Valley of Death or Naive Optimism? Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 57, 171–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Apoptosis related targets list.

Autophagy related targets list.