Abstract

The gastrointestinal microbiome is recognized as a critical component in host immune function, physiology, and behavior. Early life experiences that alter diet and social contact also influence these outcomes. Despite the growing number of studies in this area, no studies to date have examined the contribution of early life experiences on the gut microbiome in infants across development. Such studies are important for understanding the biological and environmental factors that contribute to optimal gut microbial colonization and subsequent health. We studied infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) across the first six months of life that were pseudo-randomly assigned to one of two different rearing conditions at birth: mother-peer-reared (MPR), in which infants were reared in social groups with many other adults and peers and nursed on their mothers, or nursery-reared (NR), in which infants were reared by human caregivers, fed formula, and given daily social contact with peers. We analyzed the microbiome from rectal swabs (total N=97; MPR=43, NR=54) taken on the day of birth and at postnatal days 14, 30, 90, and 180 using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Bacterial composition differences were evident as early as 14 days, with MPR infants exhibiting a lower abundance of Bifidobacterium and a higher abundance of Bacteroides than NR infants. The most marked differences were observed at 90 days, when Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Bacteroides, Clostridium and Prevotella differed across rearing groups. By day 180, no differences in the relative abundances of the bacteria of interest were observed. These novel findings in developing primate neonates indicate that the early social environment as well as diet influence gut microbiota composition very early in life. These results also lay the groundwork for mechanistic studies examining the effects of early experiences on gut microbiota across development with the ultimate goal of understanding the clinical significance of developmental changes.

Keywords: microbiome, gut microbiota, infant, macaque, development

Graphical Abstarct

INTRODUCITON

The gut microbiome is receiving increased recognition as a critical component in host immune function, physiology, and even behavior. This is evidenced by the recent uptick in studies of the microbiome in both human and nonhuman primates (NHP) in various settings (Chernikova et al., 2018; see also Clayton et al., 2018, for a review of NHP gut microbiome studies). Collectively, the literature demonstrates that early experiences shape infant gut microbial colonization, literature that is best described in human neonates. This colonization appears to be influenced by mode of birth (Frese & Mills, 2015; Rautava, 2016), gestational age at birth (Chernikova et al., 2018), time spent in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU; Chernikova et al., 2018; Hartz, Bradshaw & Brandon, 2016), bacterial transmission by various maternal body sites (Ferretti et al., 2018), infant feeding practices (Bode, 2012; Allen-Blevins, Sela & Hinde, 2015; Cong et al., 2017; Sela, 2017), and social environments, including early caregiving settings (Clayton et al., 2018; Thompson, Menteagudo-Mera, Cadenas, Lampl & Azcarate-Peril, 2015). Moreover, gut microbial composition and diversity in infancy have long-term impacts on infant health and behavior (Allen-Blevins, Sela & Hinde, 2015; Carlson et al., 2018; Kostic et al., 2015; Martin & Sela, 2013; Tamburini, Shen & Clemente, 2016; Thomas et al., 2017). Despite the large body of literature in human neonates, much remains unknown regarding the mechanisms of changes in gut microbiota composition very early in life. Getting to the root of these mechanisms requires carefully-controlled and longitudinal studies, for which NHPs are uniquely suited.

It is well established that in adults of the NHP genus Macaca, the gastrointestinal microbiome is dominated by the Clostridium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides groups (Wireman et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014). However, only a few studies to date have focused on gut microbial composition in infant NHPs. One study found differences in the relative abundance of Prevotella, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium between mother-reared and nursery-reared infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta; Ardeshir et al., 2014), suggesting that early life experiences, including diet, influence gastrointestinal microbiome composition. However, this study neglected to account for differences in early social experiences and the transmission of maternal microbes (and resulting physiological and immunological differences) that likely occurred, as well as other contributing factors.

Suboptimal early rearing experiences have known impacts on the same systems for which microbial colonization is implicated: immune function, physiology, and behavior (Jašarević, Rodgers, & Bale, 2015). Whether one considers NHPs reared in a nursery setting or human infants spending the first weeks, months, or years in the NICU or in orphanages, it is clear that these environments result in altered development. Nursery-reared (NR) NHPs exhibit increased lymphocyte responses to mitogens and lower natural killer cell activity (Coe, Lubach, Schneider, Dierschke, & Ershler, 1992; Lubach, Coe, & Ershler, 1995); altered short- and long-term stress responses (Shannon, Champoux, & Suomi; Dettmer, Novak, Suomi, & Meyer, 2012); and heightened startle responses and anxious behavior in response to stress (Sánchez et al., 2005; Dettmer, Novak, Suomi, & Meyer, 2012) compared to mother-reared (MR) monkeys. Human infants reared in the NICU or an orphanage exhibit similar patterns of development (Strunk, Currie, Richmond, Simmer, & Burgner, 2011; Melville & Moss, 2013; Loman & Gunnar, 2010; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006; Casey et al., 2011). Despite the parallel influences on infant development that are known for gut microbial colonization and early life experiences, experimental studies examining causal relationships between early experience and the gut microbiome in early life development are lacking.

Some studies have demonstrated an effect of psycho-social influences on the gut microbiome of infant monkeys (Amaral et al., 2017), including that of maternal separation (Bailey & Coe, 1999) and gestational stress (Bailey et al., 2002). However, all these studies in infant monkeys relied on subjects that were at least six months old, or on culture-based data. To date, no studies have characterized the early development of the NHP microbiome using next generation sequencing technologies. Filling the gaps in this knowledge will provide the groundwork for subsequent studies of NHP gut microbiome development, including factors that change gut microbial composition, as well as for studies of the influence of the gut microbiome on infant immune function, physiology, and socio-cognitive development. Such knowledge is important not only for furthering our understanding of NHP growth and development, but also for advancing the utility of infant NHPs as models of human child health and development.

This study aimed to begin addressing gaps in knowledge by 1) characterizing the gut microbiome in infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) from birth through the first six months of life, and 2) identifying differences in gut microbiome composition in infant monkeys as a function of early life experience. Early life experience was experimentally manipulated by rearing infant monkeys in a neonatal nursery (see Methods) and comparing their gut microbial composition to that of a control group of mother-peer-reared (MPR) infants. As such, this is the first study to characterize gut microbiota profiles in infant macaques beginning at birth and continuing throughout infancy, thereby integrating the gut microbiome into the literature on the consequences of the early life environment. We conducted amplicon (16S rRNA gene) sequencing analyses to examine the gut microbiome, with a particular focus on the relative abundances of Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium based on previous reports that these taxa predominate in the macaque gastrointestinal tract (Clayton et al., 2018), and that they also have health and developmental consequences in human primates (Martin & Sela, 2013; Thomas et al., 2017). These bacteria have important roles in shaping infant development, including stimulating the infant immune system, producing nutrients and energy for host cells, and serving as a barrier to invading pathogens (see Martin & Sela, 2013, for a review).

It is well established that diets, physical environments, and social interactions differ across NHP rearing conditions (Shannon, Champoux, & Suomi, 1998; Dettmer, Novak, Suomi, & Meyer, 2012; Dettmer & Suomi, 2014). Moreover, congruous animal models (Bailey & Coe, 1999; O’Mahony, Hyland, Dinan, & Cryan, 2011; Roger, Costabile, Holland, Hoyles, & McCartney, 2010) have indicated early life social stressors and dietary factors contribute significantly to gut microbiome composition later in development. We therefore hypothesized differences in the community structure of the NHP microbiome would emerge and persist across development as a result of rearing condition.

METHODS

Subjects and rearing

The research presented here adhered to the American Society of Primatologists Principles for the Ethical Treatment of Non-Human Primates. All procedures were approved by the NICHD Animal Care and Use Committee.

Subjects were 44 infant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta; 22 female) born and reared at the Laboratory of Comparative Ethology in Poolesville, MD. Monkeys were born in 2015 and 2016 and were pseudo-randomly assigned to one of two rearing conditions following previously established procedures (Dettmer et al., 2012; Dettmer, Novak, Meyer, & Suomi, 2014; Dettmer et al., 2017; Shannon et al., 1998): mother-peer-rearing (MPR, n=18) or nursery-rearing (NR, n=26). MPR infants were born and reared in indoor/outdoor floor-to-ceiling pens in social groups with their mothers, 8–10 adult females, 1 adult male, and 3–5 other infants (half siblings). NR infants were born to dams living in the same conditions as MPR dams, and were reared by human caregivers starting on the day of birth. NR infants were in constant visual and auditory contact with peers, received daily contact with peers starting from day 37, and received extensive enrichment through daily rotation of toys and interactions with research staff for behavioral and cognitive assessments. Beginning at day 37, NR infants were either peer-reared, living in 24-hr contact with three other same-aged peers, or surrogate-peer-reared, receiving 2-hr daily play sessions with three other same-aged peers but otherwise living in single cages with cloth-covered surrogates. All NR infants were housed together in the same room. Because preliminary analysis of the outcomes of interest did not differ between peer-reared and surrogate peer-reared infants (see Table S1), they are combined henceforth in all methods (including data analysis) and results. MPR and NR infants remained in their respective rearing conditions until approximately 8 months of age, at which time they were all relocated on a single day to a new social group comprised of MPR and NR infants from a single cohort (i.e., either 2015 or 2016; see Dettmer et al., 2012).

Feeding and diet

MPR infants nursed from their mothers ad libitum beginning on the day of birth until relocation and social group formation at approximately 8 months of age. They also were exposed to the same foods their mothers and penmates were provided daily: Purina monkey chow (#5045, St. Louis, MO), fruits, seeds, nuts, and other small food items for foraging. As they developed and were able, infants explored and ingested these food items. Water was provided ad libitum through lixits 24 hours per day. NR infants were fed Similac Advance Complete Nutrition formula (Abbott Nutrition, Chicago, IL) from the day of birth through 180 days of age, and had daily exposure to monkey chow beginning at 15 days. They also received daily fruit, seed, nut, and other foraging materials beginning at 60 days of age. NR infants were weaned from formula at 180 days, at which time they ate only the monkey chow and fruit/other food enrichment. Water was provided in water bottles during the daytime from 31–120 days, after which time it was provided ad libitum through lixits 24 hours per day.

Gut microbiome sampling

Samples were collected via rectal swab on the day of birth and at postnatal days 14, 30, 90, and 180. Swab sampling was conducted during routine neonatal assessments or veterinary health exams so as not to require additional separation from the social group and/or additional capture and sedation. To collect samples, researchers gently washed the exterior surface of the infant’s rectum with a sterile saline solution using sterile gauze, then gently and slowly inserted a sterile swab (BD CultureSwab, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) into the rectum, spun the swab around three times in each direction, and also gently twirled the swab against the walls of the rectum before extracting the swab. Swabs were immediately placed on dry ice and transferred to a −80C freezer for storage, where they remained until they were shipped to the Bailey lab at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH, for analysis.

Due to unexpected institutional managerial decisions in 2015 that influenced the timing of this research project, samples were not available for every infant at every age. Table 1 shows the sample size for rectal swabs for each rearing condition at each age.

Table 1.

Sample size for rectal swabs at each age for each rearing condition.

| DOB | D14 | D30 | D90 | D180 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPR | 6 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 13 | 43 |

| NR | 3 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 22 | 54 |

| Total | 9 | 21 | 19 | 13 | 35 | 97 |

DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA was extracted from swabs using a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit following manufacturer’s instructions, with slight modifications. Swabs were incubated for 45 min at 37°C in lysozyme buffer (22 mg/ml lysozyme, 20 mM TrisHCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton-x, pH 8.0), then bead-beat for 150 s with 0.1 mm zirconia beads. Samples were incubated at 95°C for 5 min with InhibitEX Buffer, then incubated at 70°C for 10 min with Proteinase K and Buffer AL. Following this step, the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit isolation protocol was followed, beginning with the ethanol step. DNA was quantified with the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using the dsDNA Broad Range Assay Kit. Samples were standardized to at least 5 ng/μl before being sent to the Molecular and Cellular Imaging Center (MCIC) in Wooster, OH for library preparation. Amplified PCR libraries were sequenced from both ends of the 250 nt region of the V4–V5 16S rRNA hypervariable region using an Illumina Miseq. Illinois Mayo Taxonomy Operations for RNA Database Operations (IM-TORNADO-2) workflow integrated with Mothur V1.40.0 was utilized for quality (>30)30 and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) binning of paired end reads using Mothur and Greengenes database. Downstream microbiome diversity and taxonomic analysis was completed using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology [QIIME] 1.9.131 at a sequencing depth of 2,580 sequences/sample based off of alpha-diversity (α-diversity) rarefaction (data not shown).

Data analysis

At no time point did the relative abundance of the select taxa differ between two nursery-reared groups: peer-reared and surrogate-peer-reared infants (see Table S1). As such, these infants were combined into the nursery-rearing (NR) group and significant differences between rearing groups are presented in relation to MPR values.

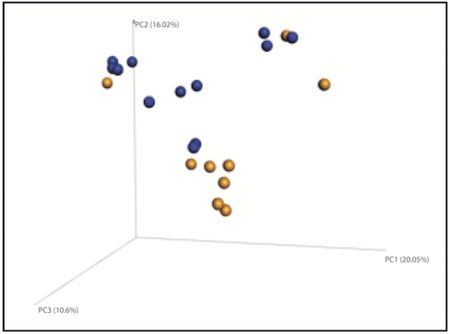

Separate permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMAVOVA) at each time point throughout were used to test the differences in gut microbiome community architecture as a result of rearing condition. We based our ß-diversity analysis on the phylogenetic-based weighted UniFrac distance metric (Lozupone, Hamady, Kelley, & Knight, 2007). UniFrac uses phylogenetic similarity metrics (based on sharing of tree branches) to compare underlying microbial community composition. Sample similarity is calculated as the sum of “unshared” branch lengths divided by the sum of all tree branch lengths (i.e., shared + unshared). Weighted UniFrac weighs each of those shared nodes based on relative abundance of each operational taxonomic unit (bacteria assignment). Sample similarity is then compared across all samples by unsupervised multi-dimensional scaling (e.g., principal components analysis, or PCoA). Here we chose three principal coordinates (PCs) to describe the gut microbiome, as it is the most descriptive (compared to one or two PCs) in visual space. The three PCs together explain nearly ~50% of the variance in community composition, thus accounting for a large percentage of the diversity variation.

Owing to the descriptive aim of the study and to the small sample sizes with non-normal distributions at each age, non-parametric analyses were performed to examine differences in gut microbiome genera between MPR and NR infants on the day of birth (DOB) and on postnatal days 14, 30, 90, and 180. Mann-Whitney U tests were performed at each age, with rearing condition as the between-subjects variable and relative abundance of each of the six bacterial genera of interest (Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium) as the dependent variables. The significance level was set at α=0.05. The distribution for each rearing group at each age was not similar (i.e., did not have the same variability; for example, at some ages some groups had 0% relative abundance of certain bacteria). Thus, the results of the Mann-Whitney U tests are to be interpreted as comparing mean ranks rather than median values.

Principal Components Analysis (PCoA) of microbiota ß-diversity was plotted by rearing conditions at each age (DOB, Day 14, Day 30, Day 90, Day 180) using QIIME 1.9.1. Additionally, heat maps were utilized (using R script) to depict the relative abundance of six prominent bacterial genera that were differentially represented among rearing conditions.

RESULTS

Rearing condition shapes gut microbial community diversity in NHP

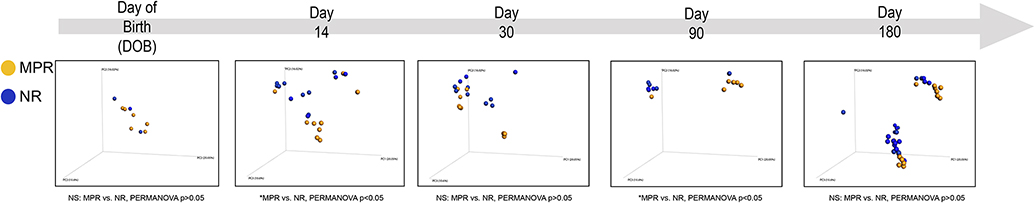

Collapsed across developmental age, no differences in α-diversity (measured by Chao 1 index) were observed as a result of rearing condition (data not shown). However, at 14 and 90 days of age there was a substantial difference in gut microbiome community diversity as a result of rearing condition (as measured by the ß-diversity weighted UniFrac distance metric; Figure 1). Most notably, we observed that microbiome community architecture of MPR monkeys clustered together, and separate from, the microbiome of NR monkeys, across these developmental time points (MPR vs. NR, PERMANOVA P<0.05).

Figure. 1.

Rearing conditions regulate gut microbial community diversity. Principal components analysis (PCoA) based on weighted UniFrac distance metric assessing the community architecture of rhesus macaques across development (Day of Birth [DOB], Day 14, Day 30, Day 90 and Day 180 post birth). Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) reveals an effect of maternal rearing (MPR) on gut microbiome community composition across developmental stages (*PERMANOVA p<0.05 versus NR, respectively).

Rearing condition alters taxonomic structure of the NHP gut microbiome

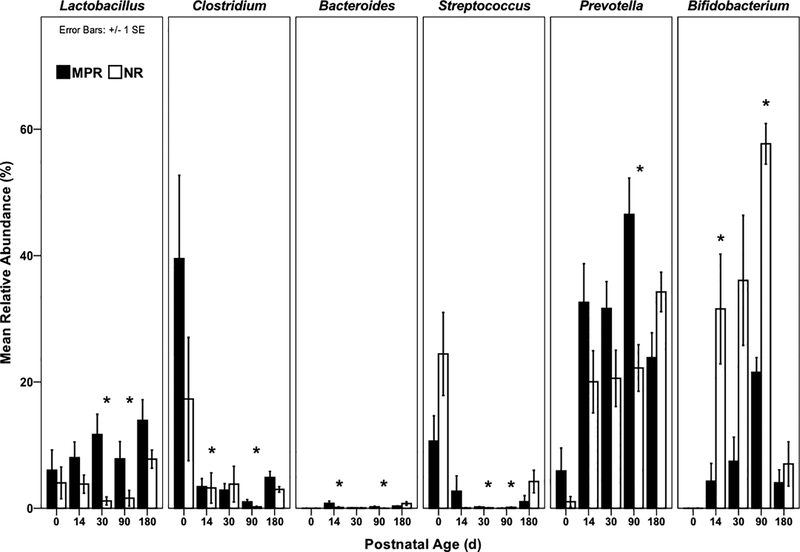

No differences in gut microbiota composition were evident between MPR and NR infants on the day of birth. Rearing differences in gut microbiota composition first emerged at day 14, with NR infants exhibiting significantly lower abundances of Bacteroides (U=25, P=0.041) and Clostridium (U=26, P=0.049) than MPR infants, and a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium (U=86, P=0.023; Figures 2 and S1). By day 30, NR infants exhibited significantly lower abundances of Lactobacillus (U=4, P<0.001) and Streptococcus (U=17, P=0.022) than MPR infants.

Figure. 2.

Mean relative abundances of bacterial genera of interest across development. *p<0.05 for Mann-Whitney U tests comparing MPR [black] and NR [white]. Postnatal age 0 = day of birth (DOB).

The effect of rearing condition on the gut microbiome was most apparent at Day 90. At this time point, all six bacterial genera of interest differed between MPR and NR infants (Figures 2). MPR infants exhibited higher abundances of Lactobacillus (U=5, P=0.022), Bacteroides (U=4, P=0.014), Clostridium (U=3, P=0.008), and Prevotella (U=1, P=0.002) than NR infants, and lower abundances of Bifidobacterium (U=42, P=0.001) and Streptococcus (U=35.5, P=0.035).

At Day 180 no differences in relative abundances of any of the bacterial genera of interest were observed.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We prospectively documented gastrointestinal microbiota composition in infant rhesus monkeys from the day of birth through six months of age. The data here represent the first direct, longitudinal comparison of gut microbiota in infant monkeys that experienced different early life experiences: mother-peer-rearing (MPR) or nursery-rearing (NR). As such, this study examined two types of early life experiences in NHPs that have been thoroughly researched with respect to biobehavioral development, but never with respect to gut microbiota composition. The findings here have important implications for understanding how very early life experiences in human infants – such as extended stays in NICUs or in orphanages – might shape their development as a consequence of differential gut microbiology. These data also incorporate an important perspective – that of host microbial community – to the literature on early life environment and development in primates.

As expected, there were no differences in the gut microbiome between MPR or NR infants at birth. However, by 14 days of life NR infants as a group exhibited decreased levels of Bacteroides and Clostridium, and elevated levels of Bifidobacterium. The higher levels of Bifidobacterium in the NR infants are consistent with the primarily plant-derived bifidogenic galacto-oligosaccharides found in the Similac formula they were fed (Gopal, Sullivan, & Smart, 2001; Kukkonen et al., 2007; Nijman, Liu, Bunyatratchata, Smilowitz, Stahl, & Barile, 2018). These galacto-oligosaccharides in commercial formula facilitate the establishment of adult-type, but not infant-type, strains of microbiota, including Bifidobacterium (Backhed et al., 2015). Moreover, despite the natural reduction in oligosaccharides in mother’s milk over the course of lactation (in humans, at least; Nijman, Liu, Bunyatratchata, Smilowitz, Stahl, & Barile, 2018), oligosaccharide concentrations remain constant throughout formula feeding. This difference likely accounts for the higher abundances of Bifidobacterium at 30 days (though not statistically significant) and at 90 days (statistically significant).

By one month of age, NR infants exhibited lower levels of Lactobacillus and Streptococcus compared to their MPR counterparts. Both Lactobacillus and Streptococcus have been found in macaque milk at peak lactation (Lin et al., 2011), which helps to explain the higher abundance of these bacteria in nursing MPR infants compared to the NR infants that received formula. Streptococcus is also a known microbe on oral and cutaneous surfaces (Walter & Ley, 2011), so it is likely that some of the MPR exposure to Streptococcus occurred via social interactions (primarily with the mother) as well as through diet. Thus, our data are consistent with others demonstrating the importance of infant diet in shaping the host microbiome, at least in the first month of life. It also appears that social interactions may be contributing to a portion of the variance in some bacteria in the neonatal period.

By 90 days of age, which represents peak lactation in rhesus monkeys (Hinde, Power, & Oftedal, 2009; Hinde & Capitanio, 2010; Hinde et al., 2015), marked differences in the gut microbiome were evident as a result of rearing condition. Relative abundances of Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Streptococcus, and Bifidobacterium all differed between MPR and NR infants. NR infants had lower relative abundances of Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Prevotella, but higher relative abundances of Bifidobacterium and Streptococcus. By this time, MPR infants have for several months ingested mother’s milk, which contains bacteria that are not found in Similac formula (Lin et al., 2011). As such, diet likely continues to explain some of the observed rearing differences in the gut microbiome at 90 days. However, between 30–90 days is when NR infants began social interactions (either in 24-hour housing or 2-hour daily play sessions). Given that social partners are known to influence host gut microbiota composition (Archie & Tung, 2015; Tung et al., 2015), it is likely that the differences in the gut microbiome that we observed between rearing groups at 90 days of age are also influenced by the social partners each rearing group had interacted with for at least the preceding two months. Thus, the combined effects of neonatal diet and early life social experiences may begin to emerge in the gut microbiome sometime between 30–90 days. These hypotheses require carefully-controlled follow-up study.

By six months of age, rhesus macaques consume less milk/formula and are primarily consuming chow, fruits, seeds, nuts, etc. As a result, the diets of MPR and NR infants are more similar by day 180. By this age, MPR and NR infants have also experienced daily social interactions with conspecifics for many months, and subsequently have been exposed to bacteria from other monkeys, as well as from their built environments, for an extended period of time. Undoubtedly, between three and six months of age, the MPR and NR infants in this study experienced substantial skin contact with other monkeys, contact with fecal material of other monkeys, and contact with the caging that other monkeys also came into contact with. Although the social partners differed – MPR infants were exposed to other adults as well as other peers, whereas NR infants were exposed to other peers only – these more similar social and dietary experiences may explain the lack of observed differences in gut microbial colonization between MPR and NR infants by six months of age.

Overall, the present findings support a growing body of literature demonstrating early life environment as a critical component that shapes the infant gut microbiome. This study provides evidence that a combination of diet plus early social and physical stressors establishes microbial communities. From birth through 90 days of life, when we observed the most marked differences in the gut microbiota composition between MPR and NR infants, diet was a key factor that differed between the groups. MPR infants drank exclusively mother’s milk, the composition of which changes across lactation (Jin, Hinde, & Tao, 2011; Hinde & Milligan, 2011). In contrast, NR infants drank commercial formula, the bacterial composition of which remains constant over time (but, both MPR and NR infants also had exposure to water and other solid food items in the first 90 days of life). Our data suggest greater individual variation in gut microbiota across development in MPR infants and greater individual consistency in NR infants. Some of this difference in individual consistency is very likely due to the temporal dynamics of mother’s milk composition that is absent in formula. Beyond diet, other important environmental factors may also contribute to the gut microbiome composition as result of rearing condition. The built environments of MPR and NR infants, and the timing of exposure to these environments, differed substantially. For instance, the housing environments contained different types of structures that were used by different types of other monkeys. From birth, MPR infants were exposed to caging and substrates that adult monkeys also used. In contrast, NR infants were only exposed to caging equipment and substrates that other infants (but not other adults) used, and this exposure began after one month of age. In addition, the two housing environments likely had subtle differences in temperature, humidity, and cleaning methods. Although not tested directly (i.e., by swabbing caging surfaces, substrates, etc.), the present findings indicate that in addition to differences in diet, these different physical and social environments experienced by MPR and NR infants may be key elements that establish the infant gut microbiome. Importantly, continuous social interaction (like that experienced by one group of NR infants, the peer-reared monkeys, as well as by the MPR infants, but not by the surrogate-peer-reared infants) does not sufficiently explain the observed differences between MPR and NR infants. Rather, it is very likely the types of social interactions – specifically, continuous exposure to other adults and their microbes – that, in addition to ingestion of mother’s milk, account for gut microbiome development.

Collectively, this study indicates that diet and early life experiences combine to influence the developing gut microbiome. The timing of observed differences in the present study have important implications for infant health and development. As the bacteria we studied have known roles in stimulating the immune system and serving as a barrier to invading pathogens (Martin & Sela, 2013), the present findings may help explain the documented differences in immune function (Lubach, Coe, & Ershler, 1995), susceptibility to disease (Elmore, Anderson, Hird, Sanders, & Lerche, 1992), and physiological and behavioral responses to stress (Sánchez et al., 2005; Dettmer, Novak, Suomi, & Meyer, 2012) between MPR and NR infants later in life. These findings also provide translational value for human infants. Precise identification of how and when differences in gut microbiome composition emerge as a result of early life experiences will require future study, though the present results are an important first step in this line of research. The present results and the small sample sizes upon which they rely necessitate replication to the extent possible (given differences in rearing practices in primate facilities). In addition to the replication that is needed to confirm that early rearing experience influences the gut microbiome across development, there are a number of exciting avenues that open up as a result of our findings. It will be necessary to conduct a detailed content analysis of both the dams’ milk and the formula that nursery-reared infants were fed (in addition to the primate chow). Additional studies focusing on social networks and types of social interactions are also needed. Finally, studies examining the gut-brain-axis are warranted, as a growing body of research is demonstrating links between the gut microbiome, neurobiology, and behavior (Cryan & O’Mahony, 2011; Cryan & Dinan, 2012; Foster, Rinaman, & Cryan, 2017). It is our hope that the present study will inspire and encourage other researchers to add to the body of literature on neonatal and infant NHP gut microbiome work, including studies of immunological development, social and cognitive development, and more.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Heat map of differentially abundant bacterial taxa across rearing conditions. MPR=mother-peer-reared; NR=nursery-reared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by funds from the Legacy Award to AMD from the American Society of Primatologists, by the Research Institute at the Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and by the Division of Intramural Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors gratefully acknowledge Ashley Murphy for scheduling sample collection and maintaining the sample database; Kristen Byers, Ryan McNeill, Emma Soneson, Emily Slonecker, Kathryn Jones, and Kielee Jennings for assistance with swab collection; Vanessa Varaljay for analysis of samples; Stephen J. Suomi for support of the project; and the dedicated animal care staff at the LCE for their exceptional care of the animals and their steadfast support of this research. We thank Gabrielle Lubach for advice on sample collection in infants.

REFERENCES

- Allen-Blevins CR, Sela DA, & Hinde K (2015). Milk bioactives may manipulate microbes to mediate parent–offspring conflict. Evolution, medicine, and public health, 2015(1), 106–121. DOI: 10.1093/emph/eov007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral WZ, Lubach GR, Proctor A, Lyte M, Phillips GJ, & Coe CL (2017). Social influences on prevotella and the gut microbiome of young monkeys. Psychosomatic medicine, 79(8), 888–897. DOI: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archie EA, & Tung J (2015). Social behavior and the microbiome. Current opinion in behavioral sciences, 6, 28–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardeshir A, Narayan NR, Méndez-Lagares G, Lu D, Rauch M, Huang Y, … & Hartigan-O’Connor DJ (2014). Breast-fed and bottle-fed infant rhesus macaques develop distinct gut microbiotas and immune systems. Science translational medicine, 6(252), 252ra120–252ra120. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, … & Khan MT (2015). Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell host & microbe, 17(5), 690–703. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MT, & Coe CL (1999). Maternal separation disrupts the integrity of the intestinal microflora in infant rhesus monkeys. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 35(2), 146–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MT, Lubach GR, & Coe CL (2004). Prenatal stress alters bacterial colonization of the gut in infant monkeys. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 38(4), 414–421. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Shannon C, Parker C, Dvoskin RL, Becker ML, … & Suomi SJ (2004). Rearing condition and rh5-HTTLPR interact to influence limbic-hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to stress in infant macaques. Biological psychiatry, 55(7), 733–738. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode L (2012). Human milk oligosaccharides: every baby needs a sugar mama. Glycobiology, 22(9), 1147–62. DOI: 10.1093/glycob/cws074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson AL, Xia K, Azcarate-Peril MA, Goldman BD, Ahn M, Styner MA, … & Knickmeyer RC (2018). Infant gut microbiome associated with cognitive development. Biological psychiatry, 83(2), 148–159. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Ruberry EJ, Libby V, Glatt CE, Hare T, Soliman F, … & Tottenham N (2011). Transitional and translational studies of risk for anxiety. Depression and anxiety, 28(1), 18–28. DOI: 10.1002/da.20783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux M, Metz B, & Suomi SJ (1991). Behavior of nursery/peer-reared and mother-reared rhesus monkeys from birth through 2 years of age. Primates, 32(4), 509–514. No DOI available. [Google Scholar]

- Chernikova DA, Madan JC, Housman ML, Lundgren SN, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, Williams SM, Moore JH, Karagas MR, & Hoen AG (2018). The premature infant gut microbiome during the first 6 weeks of life differs based on gestational maturity at birth. Pediatric Research, 84, 71–79. DOI: 10.1038/s41390-018-0022-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton JB, Gomez A, Amato K, Knights D, Travis DA, Blekhman R, … & Glander KE (2018). The gut microbiome of nonhuman primates: Lessons in ecology and evolution. American journal of primatology, e22867 DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe CL, Lubach GR, Ershler WB, & Klopp RG (1989). Influence of early rearing on lymphocyte proliferation responses in juvenile rhesus monkeys. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 3(1), 47–60. DOI: 10.1016/0889-1591(89)90005-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong X, Judge M, Xu W, Diallo A, Janton S, Brownell EA, … & Graf J (2017). Influence of Feeding Type on Gut Microbiome Development in Hospitalized Preterm Infants. Nursing research, 66(2), 123–133. DOI: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, & O’mahony SM (2011). The microbiome‐gut‐brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 23(3), 187–192. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer AM, Novak MA, Meyer JS, & Suomi SJ (2014). Population density-dependent hair cortisol concentrations in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Psychoneuroendocrinology, 42, 59–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer AM, Novak MA, Suomi SJ, & Meyer JS (2012). Physiological and behavioral adaptation to relocation stress in differentially reared rhesus monkeys: hair cortisol as a biomarker for anxiety-related responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(2), 191–199. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer AM, Wooddell LJ, Rosenberg KL, Kaburu SS, Novak MA, Meyer JS, & Suomi SJ (2017). Associations between early life experience, chronic HPA axis activity, and adult social rank in rhesus monkeys. Social neuroscience, 12(1), 92–101. DOI: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1176952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer AM, & Suomi SJ (2014). Nonhuman primate models of neuropsychiatric disorders: influences of early rearing, genetics, and epigenetics. ILAR journal, 55(2), 361–370. DOI: doi.org/10.1093/ilar/ilu025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore DB, Anderson JH, Hird DW, Sanders KD, & Lerche NW (1992). Diarrhea rates and risk factors for developing chronic diarrhea in infant and juvenile rhesus monkeys. Laboratory animal science, 42(4), 356–359. No DOI available. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, Asnicar F, Gorfer V, Fedi S, … & Beghini F (2018). Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell host & microbe, 24(1), 133–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JA, Rinaman L, & Cryan JF (2017). Stress & the gut-brain axis: regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of stress. 7, 124–126. DOI: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frese SA, & Mills DA (2015). Birth of the infant gut microbiome: moms deliver twice!. Cell host & microbe, 17(5), 543–544. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal PK, Sullivan PA, & Smart JB (2001). Utilisation of galacto-oligosaccharides as selective substrates for growth by lactic acid bacteria including Bifidobacterium lactis DR10 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus DR20. International Dairy Journal, 11(1–2), 19–25. DOI: 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00026-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, & Fisher PA (2006). Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive interventions for neglected and maltreated children. Development and psychopathology, 18(3), 651–677. DOI: 10.1017/S0954579406060330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz LE, Bradshaw W, & Brandon DH (2015). Potential NICU environmental influences on the neonate’s microbiome: a systematic review. Advances in neonatal care: official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses, 15(5), 324–335. DOI: 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K, & Capitanio JP (2010). Lactational programming? Mother’s milk energy predicts infant behavior and temperament in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). American Journal of Primatology: Official Journal of the American Society of Primatologists, 72(6), 522–529. DOI: 10.1002/ajp.20806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K, & Milligan LA (2011). Primate milk: proximate mechanisms and ultimate perspectives. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 20(1), 9–23. DOI: 10.1002/evan.20289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K, Power ML, & Oftedal OT (2009). Rhesus macaque milk: magnitude, sources, and consequences of individual variation over lactation. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 138(2), 148–157. DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.20911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinde K, Skibiel AL, Foster AB, Del Rosso L, Mendoza SP, & Capitanio JP (2014). Cortisol in mother’s milk across lactation reflects maternal life history and predicts infant temperament. Behavioral Ecology, 26(1), 269–281. DOI: 10.1093/beheco/aru186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jašarević E, Rodgers AB, & Bale TL (2015). A novel role for maternal stress and microbial transmission in early life programming and neurodevelopment. Neurobiology of stress, 1, 81–88. DOI: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Hinde K, & Tao L (2011). Species diversity and relative abundance of lactic acid bacteria in the milk of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Journal of medical primatology, 40(1), 52–58. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2010.00450.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyötyläinen T, Hämäläinen AM, … & Lähdesmäki H (2015). The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell host & microbe, 17(2), 260–273. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen K, Savilahti E, Haahtela T, Juntunen-Backman K, Korpela R, Poussa T, … & Kuitunen M (2007). Probiotics and prebiotic galacto-oligosaccharides in the prevention of allergic diseases: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 119(1), 192–198. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, & Gunnar MR (2010). Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & biobehavioral reviews, 34(6), 867–876. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Kelley ST, & Knight R (2007). Quantitative and qualitative β diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Applied and environmental microbiology, 73(5), 1576–1585. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.01996-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubach GR, Coe CL, & Ershler WB (1995). Effects of early rearing environment on immune-responses of infant Rhesus monkeys. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 9(1), 31–46. DOI: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Prince AL, Bader D, Hu M, Ganu R, Baquero K, … & Aagaard KM (2014). High-fat maternal diet during pregnancy persistently alters the offspring microbiome in a primate model. Nature communications, 5, 3889 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MA, & Sela DA (2013). Infant gut microbiota: developmental influences and health outcomes In Building babies (pp. 233–256). Springer, New York, NY: DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4060-4_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JM, & Moss TJ (2013). The immune consequences of preterm birth. Frontiers in neuroscience, 7, 79 DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller AH, Foerster S, Wilson ML, Pusey AE, Hahn BH, & Ochman H (2016). Social behavior shapes the chimpanzee pan-microbiome. Science Advances, 2(1), e1500997 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman R, Liu Y, Bunyatratchata A, Smilowitz JT, Stahl B, & Barile D (2018). Characterization and quantification of oligosaccharides in human milk and infant formula. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 66(26), 6851–6859. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony SM, Hyland NP, Dinan TG, & Cryan JF (2011). Maternal separation as a model of brain–gut axis dysfunction. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 71–88. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-010-2010-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perofsky AC, Lewis RJ, Abondano LA, Di Fiore A, & Meyers LA (2017). Hierarchical social networks shape gut microbial composition in wild Verreaux’s sifaka. Proc. R. Soc. B, 284(1868), 20172274 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautava S (2016). Early microbial contact, the breast milk microbiome and child health. Journal of developmental origins of health and disease, 7(1), 5–14. DOI: 10.1017/S2040174415001233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger LC, Costabile A, Holland DT, Hoyles L, & McCartney AL (2010). Examination of faecal Bifidobacterium populations in breast-and formula-fed infants during the first 18 months of life. Microbiology, 156(11), 3329–3341. DOI: 10.1099/mic.0.043224-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez MM, Noble PM, Lyon CK, Plotsky PM, Davis M, Nemeroff CB, & Winslow JT (2005). Alterations in diurnal cortisol rhythm and acoustic startle response in nonhuman primates with adverse rearing. Biological psychiatry, 57(4), 373–381. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela DA (2017, April). Human Milk Interactions With the Developing Infant Microbiome. In The 116th Abbott Nutrition Research Conference (p. 35). No DOI available. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon C, Champoux M, & Suomi SJ (1998). Rearing condition and plasma cortisol in rhesus monkey infants. American Journal of Primatology, 46(4), 311–321. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strunk T, Currie A, Richmond P, Simmer K, & Burgner D (2011). Innate immunity in human newborn infants: prematurity means more than immaturity. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 24(1), 25–31. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2010.482605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, & Clemente JC (2016). The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nature medicine, 22(7), 713–722. DOI: 10.1038/nm.4142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Izard J, Walsh E, Batich K, Chongsathidkiet P, Clarke G, … & Gilligan JP (2017). The host microbiome regulates and maintains human health: a primer and perspective for non-microbiologists. Cancer research, 77(8), 1783–1812. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AL, Monteagudo-Mera A, Cadenas MB, Lampl ML, & Azcarate-Peril MA (2015). Milk-and solid-feeding practices and daycare attendance are associated with differences in bacterial diversity, predominant communities, and metabolic and immune function of the infant gut microbiome. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 5, 3 DOI: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung J, Barreiro LB, Burns MB, Grenier JC, Lynch J, Grieneisen LE, … & Archie EA (2015). Social networks predict gut microbiome composition in wild baboons. Elife, 4, e05224 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.05224.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J, & Ley R (2011). The human gut microbiome: ecology and recent evolutionary changes. Annual review of microbiology, 65, 411–429. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wireman J, Lowe M, Spiro A, Zhang YZ, Sornborger A, & Summers AO (2006). Quantitative, longitudinal profiling of the primate fecal microbiota reveals idiosyncratic, dynamic communities. Environmental microbiology, 8(3), 490–503. DOI: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Heat map of differentially abundant bacterial taxa across rearing conditions. MPR=mother-peer-reared; NR=nursery-reared.