Abstract

Background

Understanding the molecular mechanisms in perturbation of the metabolome following ischaemia and reperfusion is critical in developing novel therapeutic strategies to prevent the sequelae of post-injury shock. While the metabolic substrates fueling these alterations have been defined, the relative contribution of specific organs to the systemic metabolic reprogramming secondary to ischaemic or haemorrhagic hypoxia remains unclear.

Materials and methods

A porcine model of selected organ ischaemia was employed to investigate the relative contribution of liver, kidney, spleen and small bowel ischaemia/reperfusion to the plasma metabolic phenotype, as gleaned through ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics.

Results

Liver ischaemia/reperfusion promotes glycaemia, with increases in circulating carboxylic acid anions and purine oxidation metabolites, suggesting that this organ is the dominant contributor to the accumulation of these metabolites in response to ischaemic hypoxia. Succinate, in particular, accumulates selectively in response to the hepatic ischemia, with levels 6.5 times spleen, 8.2 times small bowel, and 6 times renal levels. Similar trends, but lower fold-change increase in comparison to baseline values, were observed upon ischaemia/reperfusion of kidney, spleen and small bowel.

Discussion

These observations suggest that the liver may play a critical role in mediating the accumulation of the same metabolites in response to haemorrhagic hypoxia, especially with respect to succinate, a metabolite that has been increasingly implicated in the coagulopathy and pro-inflammatory sequelae of ischaemic and haemorrhagic shock.

Keywords: metabolism, succinate, UHPLC-MS, trauma/haemorrhagic shock

Introduction

Since the early nineteenth century, the term ischaemia has been used to describe a state of deficient blood supply to tissues due to the obstruction of the arterial inflow1. Recent advances in the field of metabolomics have elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying the ischaemic injury to specific organs, including kidney, heart, brain and liver in animal models and humans2–5. Initially, ischaemic injury was in part explained by the inadequate oxygen supply to a given organ, resulting in the upregulation of anaerobic metabolism (e.g. glycolysis), impaired capacity to preserve high-energy phosphate compounds such as adenosine triphosphate and pH acidification1. More recent evidence suggests hypoxia also results in the lack of a final acceptor of electrons at complex IV of mitochondria triggering a backwards flow of electrons through the mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes, which promotes the accumulation of succinate from complex II2,6,7.

Succinate build up during ischaemia, followed by oxygen replenishment upon reperfusion, promotes a rapid accumulation of fumarate, which is accompanied by a burst in the generation of oxygen radicals, the final mediators of the ischaemia reperfusion (I/R) injury2,6,7. Animal models of haemorrhagic shock8,9 suggest that these mechanisms are not just relevant to hypoxia, but could also contribute to the increase in the levels of circulating succinate and fumarate observed during haemorrhagic shock in trauma patients10–14. These considerations are clinically relevant given that trauma is the leading cause of mortality under the age of 44 years15 and metabolic reprogramming during trauma and shock affects morbidity and mortality16. Indeed, metabolic changes secondary to trauma and haemorrhage underlie early coagulopathy17 and late inflammatory complications8,12,18.

Analogously, research has highlighted a role for small molecule metabolites like succinate, a citric acid cycle intermediate and hallmark of ischaemic2 and haemorrhagic hypoxia8, as a key causative player in coagulopathy and inflammatory states19–21. Tracing experiments in animal models in vivo suggest glutamine, rather than glucose, is the preferred substrate for the generation of ischaemic and haemorrhagic succinate8,9, while purine salvage reactions downstream to purine catabolism appear to fuel fumarate accumulation upon I/R2.

Previous studies have addressed the central role of systemic hypoxia due to haemorrhage in producing metabolomic changes following trauma22. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the specific plasma metabolomic contributions of intra-abdominal organs following organ ischaemia using arterial occlusion. The goal is to delineate the role of these organs in clinically relevant scenarios such as global shock and hypoxia or intra-abdominal ischaemia due to aortic cross clamping or resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). The experimental design would enable us to determine whether a specific organ represents a source of pathological metabolites accumulating after an ischaemic insult. Since the liver is the most metabolically active organ in the human body, we hypothesise that occlusion of liver blood flow represents the main contributor to the metabolic derangements observed following ischaemia and reperfusion.

Methods

Animal model

The animal protocol was approved by the University of Colorado Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male farm pigs (50–55 kg) underwent anaesthesia induction with a combination of ketamine (20 mg/kg) (VETone, Boise, ID, USA), acepromazine (0.2 mg/kg) (VETone), and xylazine (2 mg/kg) (Akorn, Decatur, IL, USA), and were then maintained on general anaesthesia using isoflurane (0.5–2%) (VETone) in room air, by mask. Pigs underwent tracheostomy and femoral artery cannulation to measure blood pressure. After tracheostomy, the animals were maintained with isoflurane (0.5–2%) and placed on mechanical ventilation to maintain O2 saturation over 90%. Upon completion of the experiment, the animal was euthanised by exsanguination.

Selective organ ischaemia

Pigs (n=5) underwent laparotomy and isolation of arterial supply to the selected organs: liver, kidney, spleen, and small bowel. For the liver, the porta hepatis was clamped and blood was collected from the right hepatic vein without clamping the vena cava. For the small bowel, blood flow was occluded at the superior mesenteric artery and the portal vein was used for venous samples. For kidney and spleen, the vascular pedicle was clamped, occluding the arterial inflow and venous outflow simultaneously.

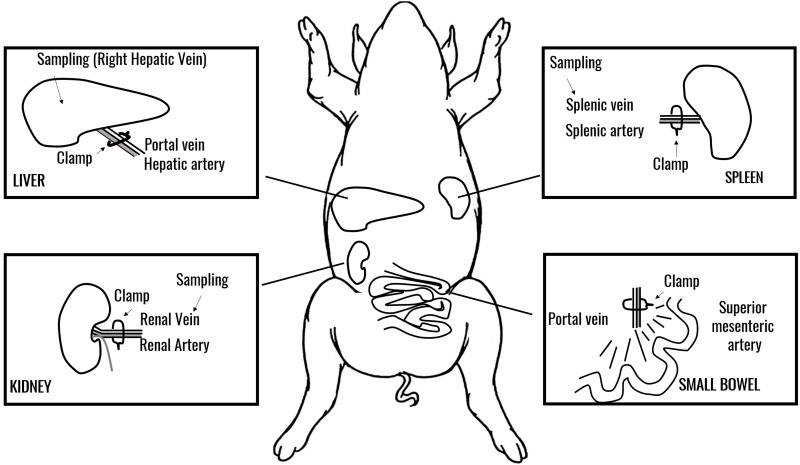

Pre-clamping samples were collected as baseline from each organ’s venous drainage, followed by simultaneous clamping of arterial inflow, with blood drawn at 15 and 30 min after occlusion and 5 min after reperfusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the swine model of selected organ ischaemia used in this study.

Organ clamping and sampling areas are indicated. Sampling was performed from venous supply for each organ at baseline, 15 or 30 min through ischaemia and upon reperfusion. Where applicable, sampling was performed distal to the venous clamp.

Blood samples

Whole blood was collected and prepared as previously described10. Plasma was recovered through centrifugation (2,500 g for 10 min at 4 °C) from each of the 5 pigs and pooled for analysis.

Metabolomics analyses

Metabolomics analyses were performed as previously reported10,18. In brief, plasma samples (10 μL) were immediately extracted in ice-cold lysis/extraction buffer (methanol:acetonitrile:water 5:3:2) at 1:50 dilutions. Samples were then agitated at 4 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Protein pellets were discarded, while supernatants and the methanol soluble lipid fraction were stored at −80 °C prior to metabolomics analyses. Ten μL of sample extracts were injected into an UHPLC system (Vanquish, Thermo, San Jose, CA, USA) and run on a Kinetex XB-C18 column (150×2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm particle size) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using either a 3-min isocratic run (hydrophilic fraction) or a gradient from 5 to 95% B over 9 min (hydrophobic fraction) at 250 μL/min (mobile phase: 5% acetonitrile, 95% 18 mΩ H2O, 0.1% formic acid). The UHPLC system was coupled online with a Q Exactive system (Thermo) scanning in Full MS mode (2 μscans) at 70,000 resolution in the 60–900 m/z range (hydrophilic fraction) or 150–2,000 m/z (hydrophobic fraction), 4 kV spray voltage, 15 sheath gas and 5 auxiliary gas, operated in negative and then positive ion mode (4 separate runs per sample). Calibration was performed before each analysis against positive or negative ion mode calibration mixes (Piercenet - Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL, USA) to ensure sub ppm error of the intact mass. Metabolite assignments were performed using Maven software (Princeton, NJ, USA) upon conversion of .raw files into .mzXML format through MassMatrix (Cleveland, OH, USA). The software allows for peak picking, feature detection and metabolite assignment against the KEGG pathway database. Assignments were further confirmed against chemical formula determination (as gleaned from isotopic patterns and accurate intact mass), and retention times against a more than 630 standard compounds library, including commercially available glycolytic and Krebs cycle intermediates, amino acids, glutathione homeostasis and nucleoside phosphates (SIGMA Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; IROATech, Bolton, MA, USA). Automated feature detection was also performed on the raw mass spectrometry files using Compound Discoverer 2.1 software (Thermo Fisher). Only features with a minimum relative ion intensity of 1,000 and a signal to noise ratio of 3 were included in the analysis.

Data analysis

Relative quantitation was performed by exporting integrated peak area values into Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, CA, USA). Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed through the software GENE-E (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). Integrated peak area values in arbitrary units were graphed through GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and figure panels were assembled through Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, Mountain View, CA, USA) and Inkscape 0.92.3. The relative quantitation of integrated peak area values identified by automated feature detection were compared between all sham time points (n=4) and all ischaemic time points (n=4 each for each organ) for each experimental group using a one-way analysis of variance with correction for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction using JMP Pro 14 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Features were considered significant if they had a fold change of 2-fold or greater or 50% reduction or less and an FDR corrected p-value <0.05.

Results

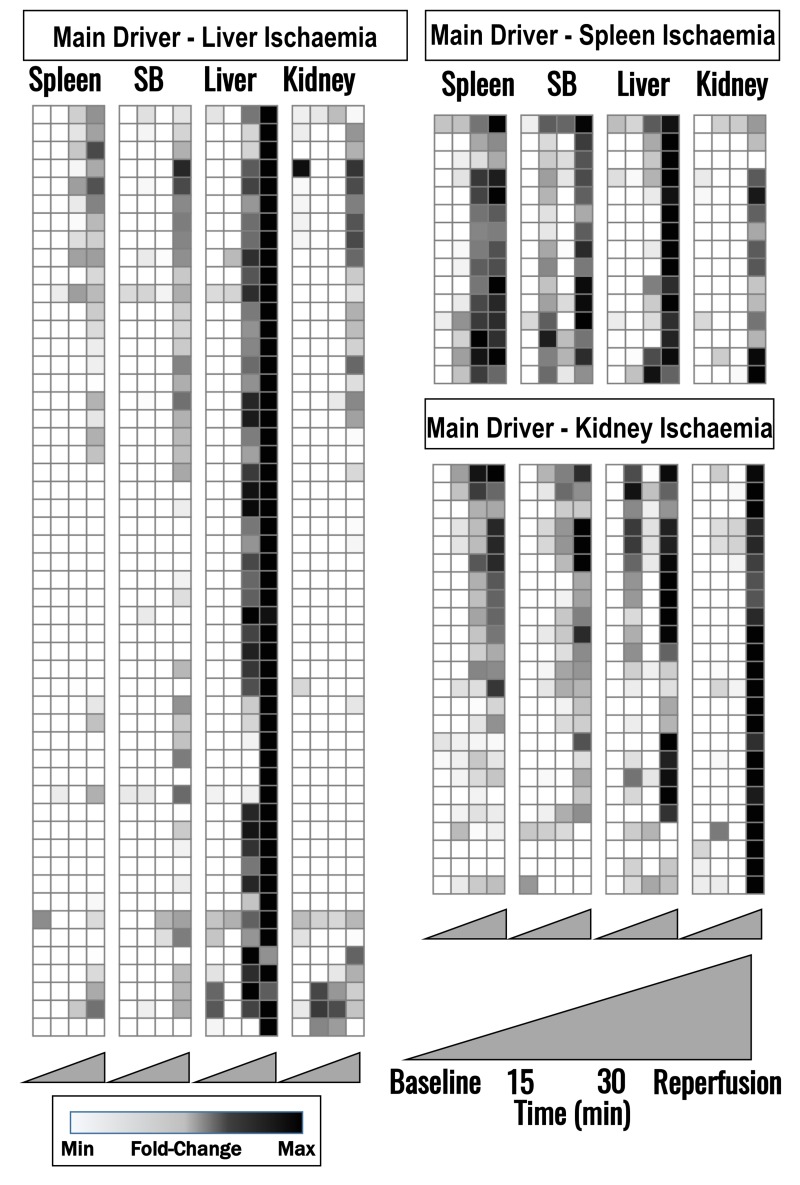

Metabolomic analyses of a total of 168 named metabolites were conducted (Online Supplementary Content, Table SI). Hierarchical clustering analysis grouping metabolites based on relative time-course trended in each organ is displayed in a vectorial version provided as Online Supplementary Content, Figure S1. Figure 2 represents the overall heat maps (white: lowest level of a given metabolite across all tested samples; black: highest levels). Metabolites that accumulated in plasma after liver I/R, but not I/R to other organs are shown in Figure 2, left panel. Metabolites which predominantly increased upon spleen or kidney I/R are shown in Figure 2, right panel. Names of these specific metabolites are detailed in Online Supplementary Content, Figure S1. Pathway analyses indicated that the representative metabolites reported in Figure 2 are grouped as follows: i) glycolysis, glutaminolysis and TCA cycle (Figure 3); ii) purine catabolism/oxidation (Figure 4); iii) arginine metabolism, urea cycle, polyamine and creatine metabolism (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Heat maps of time course (baseline, 15 and 30 min through ischaemia, and reperfusion) metabolic changes in plasma from pigs upon clamping of spleen, small bowel (SB), liver or kidney blood flow.

Metabolites affected by liver ischaemia (left panel), spleen ischaemia (top right), kidney ischaemia (bottom right) are indicated (labels for each metabolite are provided in Online Supplementary Content, Figure S1). Metabolite levels were normalised across samples (Z-score normalisation) and colour-coded from white (low) to black (high).

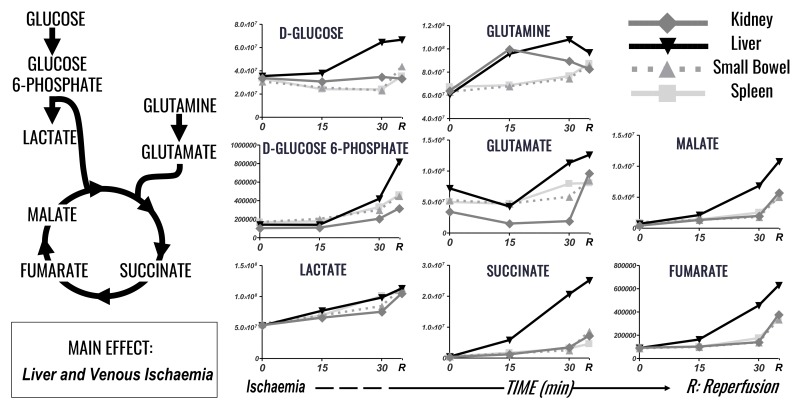

Figure 3.

Time course analysis of glycolysis, TCA cycle and glutaminolysis markers in plasma of pigs undergoing selected organ ischaemia.

Lines are representative of each metabolite in each group, according to the label scheme in the top right corner.

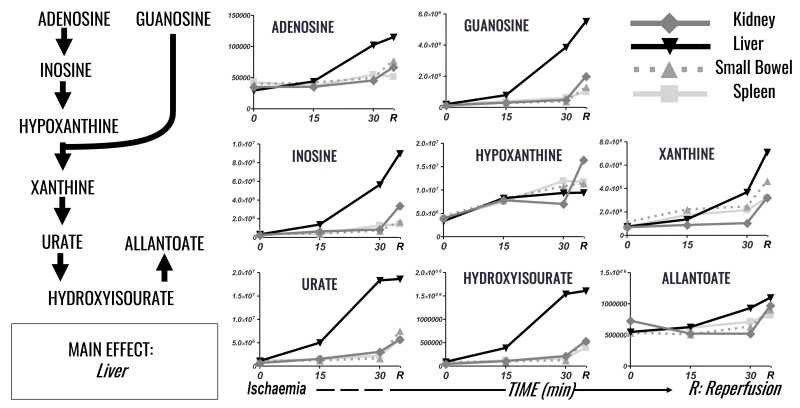

Figure 4.

Time course analysis of purine metabolism and purine oxidation markers in plasma of pigs undergoing selected organ ischaemia.

Lines are representative of each metabolite in each group, according to the label scheme in the top right corner.

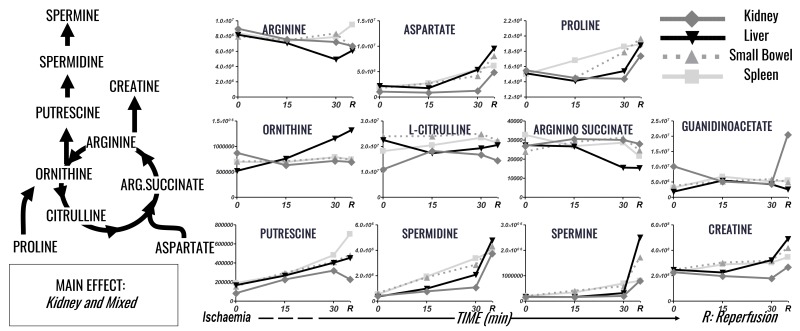

Figure 5.

Time course analysis of nitrogen metabolism (arginine, urea cycle, creatine and polyamine metabolism) markers in plasma of pigs undergoing selected organ ischaemia.

Lines are representative of each metabolite in each group, according to the label scheme in the top right corner.

The liver is the primary mediator of changes seen in metabolites pertaining to glycolysis, glutaminolysis and the TCA cycle (Figure 3). Glucose is increased to 1.9 times baseline levels in the liver in response to I/R. Similarly, Glucose-6-phosphate is increased 5.8 times baseline levels in response to hepatic ischaemia, and further increased during reperfusion. Lactate increased uniformly in response to I/R in all intra-abdominal organs, with increases 1.9–2.1 times baseline levels. Krebs cycles intermediates, by contrast, were all selectively increased in response to hepatic ischaemia, with augmentation of the increases following reperfusion. Malate, succinate and fumarate increase 15.3-fold, 55.4-fold and 7-fold, respectively, compared to baseline levels in the liver.

Hepatic ischaemia promotes differential accumulation of succinate, which was 6.5 times spleen, 8.2 times small bowel, 6 times renal levels in hepatic samples at the end of reperfusion. Glutamine and glutamate elaboration in response to ischaemia are somewhat more heterogeneous. Glutamine has an early peak in response to renal ischaemia, rising to 1.6 times baseline at 15 min of ischaemia, and then dropping to 1.3 times baseline upon reperfusion. Glutamine increases throughout the duration of ischaemia in the small bowel, spleen and liver, although liver reperfusion promotes a slight decrease in glutamine levels (from 1.8 times baseline levels at 30 min of ischaemia to 1.6 times that after reperfusion). Glutamate accumulation in response to I/R shows the greatest response from the kidney, with an increase of 2.7 times from baseline occurring exclusively after reperfusion. The other organs by comparison show increases in glutamate levels 1.6–1.7 times baseline. However, the highest overall levels of glutamate are released in response to hepatic I/R by virtue of its greater levels at baseline. In summary, the liver is primarily responsible for increases in glucose, glutamine and the downstream products leading into and through the TCA cycle.

Ischaemia reperfusion injury promoted significant alterations of purine catabolism and oxidation in the liver, 2–4 times higher than other organs (Figure 4); a phenomenon that resulted in the accumulation of plasma adenosine, guanosine and inosine, and the relative catabolites hypoxanthine, xanthine, urate and hydroxyisourate. Adenosine and inosine show marked increases in response to liver I/R, rising to 3.9 and 28.3 times baseline levels. Hypoxanthine shows fairly uniform enrichment in response to organ I/R, with levels increasing 2.6–4 times baseline in all organs, with the kidney showing the greatest increase (4 times baseline). Guanosine shows again preferential accumulation in response to hepatic I/R, rising to 27 times baseline levels. Hepatic levels peak at 2.7 times, 4.2 times and 5.6 times kidney, small bowel and splenic levels after reperfusion. The downstream products of xanthine, urate and hydroxyisourate show increases throughout I/R in all organs, with the dominant driver again the liver. Hepatic I/R promotes increases in xanthine, urate and hydroxyisourate 9.6 times, 17 times, 17.7 times baseline levels. Hepatic xanthine increases are greatest upon reperfusion, while reperfusion attenuates the increases seen in urate and hydroxyisourate. Allantoate, similarly to hypoxanthine, is not selectively enriched by a single organ but increases with I/R of all organs measured (1.3–2 times baseline, with the greatest increase [2 times] in response to hepatic ischaemia).

Different organs, including the urea cycle, arginine metabolism, creatinine and polyamines, contributed to nitrogen metabolism, with no clear dominant organ responsible. I/R of kidney and spleen resulted in the greatest effect on arginine, proline, creatine and polyamine metabolism (Figure 5). Arginine decreased in response to small bowel, kidney and hepatic I/R (0.8 times baseline levels), with a slight increase in response to splenic I/R. Proline increased 1.1–1.3 times baseline following I/R, with the smallest change in response to renal ischaemia, and the greatest response to small bowel ischaemia. Creatinine was affected most significantly by renal ischaemia, with increases 1.6 times baseline, while other organ ischaemia increased levels 1.01.1 times baseline. Arginine consumption and accumulation of ornithine, polyamines (putrescine, spermidine and spermine) were observed upon I/R to all organs, with no significant major contribution of one organ over the other (Figure 5). Spermine increased 4, 5, 8.7 and 14.9 times baseline levels in response to spleen, kidney, small bowel and hepatic ischaemia, with spermidine following a similar trend. Putrescine increased anywhere 2.7–3.7 times baseline levels, with the greatest response from splenic ischaemia and the least response from hepatic and renal ischaemia.

Small molecule metabolites involved in redox homeostasis (e.g. reduced glutathione - GSH, cysteine, carnosine, kynurenine, taurine and hypotaurine) and, in general, metabolites involved in glutathione turnover (5-oxoproline) or sulphur metabolism (taurine, hypotaurine, methionine, GSH) were mostly affected by liver and kidney I/R (Online Supplementary Content, Figure S2). Taurine is increased upon reperfusion of the liver and kidney, and reduced glutathione (GSH) is increased upon reperfusion of the liver, kidney and small bowel. No substantial increases were observed in the post-I/R circulating levels of carnitine, tryptophan and serotonin (Online Supplementary Content, Table SI).

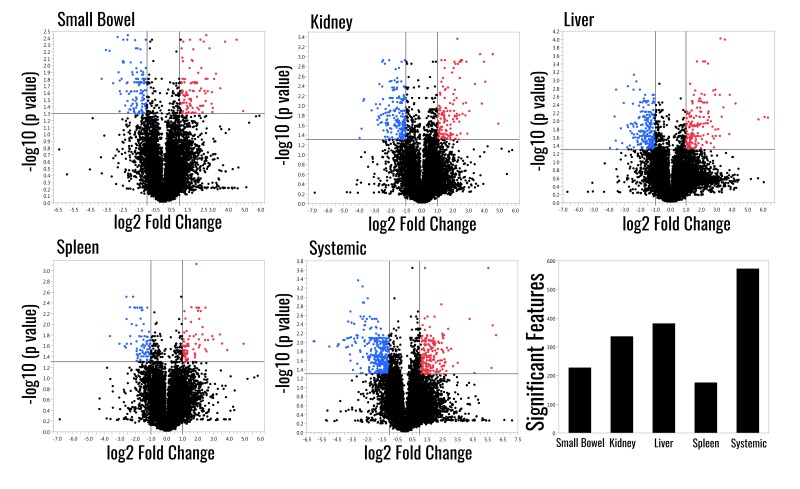

Automated feature detection identified an additional 12,633 features (Online Supplementary Content, Table SII). Between 1% and 5% of these features were significantly different compared to the sham group, with the systemic venous samples having the greatest number of significant features and the spleen having the fewest (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Volcano plots comparing the sham treatment to each ischaemic group and total count of significant features for each group.

The graph lines indicate the threshold for significance for fold change and FDR p-values.

Discussion

This study details a MS-metabolomics-based investigation of the effects of isolated visceral ischaemia and reperfusion. Hepatic ischaemia promoted the largest changes in metabolites across the widest spectrum of pathways compared to any other organ. The liver was the main source for accumulation of glucose and glucose intermediates, as well as glutamate and Krebs cycle intermediates, which were not corrected by early reperfusion. Most notable among these was succinate, which accumulated selectively in response to hepatic ischaemia. Additionally, hepatic ischaemia played the largest role in purine catabolism and oxidation. Conversely, ischaemia of the kidney and spleen had the greatest effect on arginine, proline, creatine and polyamine metabolism. Finally, metabolites involved in redox homeostasis were most affected by liver and kidney ischaemia. Taken together, liver ischaemia is the predominant driver of metabolic alterations during abdominal organ ischaemia and reperfusion, followed by the kidney, spleen and small bowel.

The liver mediates gluconeogenesis/glycogenolysis and is a target of insulin and glucagon signalling23. Because it is the main source for circulating glucose, liver I/R results in a unique signature with respect to glycaemia and circulating glucose catabolites. Conversely, no significant differences were observed in lactataemia across ischaemic organs, suggesting that all organs rely on similar anaerobic glycolysis rates in response to a lack of oxygen. In the last few years, metabolomic studies have burgeoned in the field of IR injury2–5, suggesting a mechanistic role for hypoxia mediating the uncoupling of the electron transport chain, and the transient accumulation of metabolic substrates fueling reactive oxygen species generation upon reperfusion, most notably succinate2,7. Succinate has been tied to the induction of inflammatory cascades through the stimulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1α)-mediated signals involving pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β, which may explain the untoward pro-inflammatory sequelae of ischaemia24. Additionally, succinate has been shown to have a direct pro-inflammatory effect through the succinate receptor, and increased levels are an excellent predictor of post-traumatic death21,25. These observations are not just relevant to inflammatory consequences of ischaemic hypoxia, but could also underlie some of the adverse sequelae of haemorrhagic shock. Tissue injury and haemorrhage result in the accumulation of circulating carboxylic acids in animal models and humans10,12,13,18,26,27. In the current study, we establish the primary role of the liver in the production of TCA cycle intermediates such as succinate, malate and fumarate. Tracing experiments in animal models has suggested a minor role for glycolysis8, in contrast to a more prominent role for glutaminolysis9 and purine catabolism and salvage2, in mediating the accumulation of systemic plasma succinate in response to haemorrhagic or ischaemic hypoxia.

Additional non-TCA metabolic derangements were also evident. Early increases in plasma adenosine have been reported following haemorrhagic shock, and in this study we have shown this to be predominantly the result of hepatic ischaemia10,28–31. Previous metabolomic studies following I/R, especially of kidneys, have identified allantoin (an end product of purine catabolism and oxidation) as one of the metabolites showing the highest fold change increases in plasma following the ischaemic insult1,3–5,32,33. Moreover, increases in circulating levels of purines (adenosine and guanosine) and downstream metabolites (inosine, hypoxanthine, xanthine, urate and hydroxyisourate) were observed in response to I/R for all organs, though liver ischaemia contributed the most to these metabolic changes (up to 4 times higher than other organs). This increase in purines was in part expected owing to the critical role hepatocytes play in their metabolism and biosynthesis34. Arginine catabolism and polyamine synthesis were similarly affected by I/R to all organs: however, spleen and small bowel I/R showed the highest effect on proline catabolism, putrescine, spermidine and guanidinoacetate accumulation. The increase in these metabolites suggests a likely effect mediated by the gut microbiome35. 5-oxoproline production was predominantly produced by hepatic I/R, with implications for worsening metabolic acidosis36.

Ischaemia reperfusion injury is in part mediated by the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)2, which implies that: 1) oxidised small molecule metabolites, such as taurine and kynurenine, are potential markers of the severity of the I/R injury; and 2) I/R can be attenuated by boosting antioxidant defences by exogenous supplementation of antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine (a precursor to cysteine in the synthesis of glutathione), carnitine, carnosine, or hypotaurine3,33,37–39. Importantly, the administration of hypotaurine, N-acetylcysteine or methionine to rats upon reperfusion attenuated post-ischaemic liver injury39. However, only hypotaurine prevented the ischaemic elevation of hepatic lactate and promoted recovery of the energy charge upon reperfusion. Increases in plasma taurine upon reperfusion in hypotaurine pre-conditioned rats suggested that the exogenously administered compound was utilised as an antioxidant, and taurine has been proposed as a potential marker of the severity of I/R39. In the presented data, I/R promoted increases in circulating taurine and hypotaurine, and, although no major contribution to this phenomenon was observed, it was noted that hypotaurine consumption was the highest upon reperfusion of the liver. Additionally, taurine levels are increased following reperfusion, with the greatest effect from renal reperfusion, suggesting a possible role for plasma hypotaurine to scavenge free radicals with production of taurine.

Other soluble markers of oxidative stress either increased (reduced glutathione, kynurenine, cystine) or were not altered (carnitine, methionine, cystine) by I/R. Glutathione had a marked increase upon reperfusion of all organs, most significantly in the liver, suggesting increased oxidative stress upon reperfusion, possibly as a result of succinate metabolism.

This study, while providing many important insights in organ ischaemia with implications on global hypoperfusion states, does have several limitations. Most importantly, samples were pooled within groups, which limits the ability of this study to provide measures of statistical significance between time points. However, as an investigational study, this does highlight global trends. Combining the time points did allow us to perform a limited statistical comparison between the sham group and each experimental ischaemic group, and identify an additional 12,633 features with up to 5% having levels that change in response to I/R. Additionally, while we see a relatively minor contribution from small bowel ischaemia, our previous studies have shown lymphatic drainage of the small bowel is bioactive40. We did not sample the lymphatic drainage of the small bowel, potentially under-estimating the effect of small bowel ischaemia on the global plasma metabolome. Additionally, the method of organ ischaemia also occluded the venous outflow for kidney, spleen and small bowel that may add a confounding effect of venous stasis to the experimental protocol. While the effect of venous stasis is likely minimal with the lack of arterial inflow, this may affect the organs’ response to ischaemia. Additionally, tracings reveal that the metabolomic derangements are not corrected at 5 min of reperfusion, but in some cases are exacerbated. For example, lactate, a biomarker of tissue hypoxia is increased following reperfusion. While this may represent washout of ischaemic metabolites, the fact that these metabolites are being released into circulation despite reperfusion suggests that post-ischaemic metabolomics derangements persist despite normalisation of blood flow. Additional time points would be valuable to determine over what time frame these metabolomic derangements resolve and its implication for patients who have suffered profound organ ischaemia.

In this study, we expand on prior work showing the key role of haemorrhagic shock in producing metabolomics derangements22, and delineate the extent and dynamics of plasma metabolic responses to organ-specific ischaemia and reperfusion. The liver played a primary role in mediating the majority of the systemic metabolic aberrations observed after ischaemia as well as the accumulation of plasma succinate and purine oxidation products. These observations expand our understanding of the systemic response to ischaemia and suggest the potential source of haemorrhagic hypoxia-driven accumulation of potentially pathogenic small molecule metabolites such as succinate. These molecules may have significant roles in the pathogenesis of trauma-induced coagulopathy as well as organ dysfunction. The central role of hepatic ischaemia has important implications in trauma, as resuscitative techniques such as REBOA or descending aortic cross clamp potentially carry a higher burden with regard to IR injury when they occlude blood flow to the liver.

Conclusions

Ischaemia and reperfusion generate substantial derangements in the plasma metabolome due to inadequate oxygen delivery and access to metabolic substrate. In a porcine selective organ ischaemia model, we noted that liver ischaemia and reperfusion generated the greatest changes to the plasma metabolome relative to the other organs studied.

Online supplementary content

Acknowledgements

Angelo D‘Alessandro received funds from the National Blood Foundation. This study is supported by the US Army Medical Research Acquisition Act of the Department of Defense under Contract Award Number W81XWH1220028 and the National Institutes of Health (P50 GM049222, T32 GM008315, and UMHL120877). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

NC, GRN and AD shared first authorship. EEM, AB, CS, HBM designed the study. EG, MF, MC and HBM performed surgeries on the animals and collected samples. NC, JAR, TN, MJW, KH and AD set up the metabolomics assays and performed metabolomics analyses. AD prepared the tables and figures, and wrote the paper. GRN, NC and AD revised the paper. All the Authors critically contributed to the final manuscript for publication.

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, et al. Cell biology of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012;298:229–317. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, et al. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Nature. 2014;515:431–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jouret F, Leenders J, Poma L, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomic profiling of mouse kidney, urine and serum following renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Wang Y, Li M, et al. (1)H NMR-based metabolomics exploring biomarkers in rat cerebrospinal fluid after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:431–9. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25224d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei Q, Xiao X, Fogle P, et al. Changes in metabolic profiles during acute kidney injury and recovery following ischemia/reperfusion. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pell VR, Chouchani ET, Frezza C, et al. Succinate metabolism: a new therapeutic target for myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111:134–41. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tretter L, Patocs A, Chinopoulos C. Succinate, an intermediate in metabolism, signal transduction, ROS, hypoxia, and tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:1086–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D‘Alessandro A, Slaughter AL, Peltz ED, et al. Trauma/hemorrhagic shock instigates aberrant metabolic flux through glycolytic pathways, as revealed by preliminary (13)C-glucose labeling metabolomics. J Transl Med. 2015;13:253. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0612-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slaughter AL, D‘Alessandro A, Moore EE, et al. Glutamine metabolism drives succinate accumulation in plasma and the lung during hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:1012–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D‘Alessandro A, Moore HB, Moore EE, et al. Early hemorrhage triggers metabolic responses that build up during prolonged shock. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308:R1034–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00030.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D‘Alessandro A, Moore HB, Moore EE, et al. Plasma first resuscitation reduces lactate acidosis, enhances redox homeostasis, amino acid and purine catabolism in a rat model of profound hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2016;46:173–82. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peltz ED, D‘Alessandro A, Moore EE, et al. Pathologic metabolism: an exploratory study of the plasma metabolome of critical injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:742–51. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinross JM, Alkhamesi N, Barton RH, et al. Global metabolic phenotyping in an experimental laparotomy model of surgical trauma. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:277–87. doi: 10.1021/pr1003278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheppard FR, Macko A, Fryer DM, et al. Development of a nonhuman primate (Rhesus Macaque) model of uncontrolled traumatic liver hemorrhage. Shock. 2015;44(Suppl 1):114–22. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;64:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuthbertson DP, Angeles Valero Zanuy MA, Leon Sanz ML. Post-shock metabolic response. 1942. Nutr Hosp. 2001;16:176–82. discussion 175–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiener G, Moore HB, Moore EE, et al. Shock releases bile acid inducing platelet inhibition and fibrinolysis. J Surg Res. 2015;195:390–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D‘Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Moore HB, et al. Metabolomics of trauma-associated death: shared and fluid-specific features of human plasma vs lymph. Blood Transfus. 2016;14:185–94. doi: 10.2450/2016.0208-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogberg C, Gidlof O, Tan C, et al. Succinate independently stimulates full platelet activation via cAMP and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-beta signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:361–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spath B, Hansen A, Bokemeyer C, et al. Succinate reverses in-vitro platelet inhibition by acetylsalicylic acid and P2Y receptor antagonists. Platelets. 2012;23:60–8. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2011.590255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Littlewood-Evans A, Sarret S, Apfel V, et al. GPR91 senses extracellular succinate released from inflammatory macrophages and exacerbates rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1655–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clendenen N, Nunns GR, Moore EE, et al. Hemorrhagic shock and tissue injury drive distinct plasma metabolome derangements in swine. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:635–42. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aronoff SLBK, Shreiner B, Want L. Glucose metabolism and regulation: beyond insulin and glucagon. Diabetes Spectrum. 2004;17:8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2013;496:238–42. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D‘Alessandro A, Moore HB, Moore EE, et al. Plasma succinate is a predictor of mortality in critically injured patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:491–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forni LG, McKinnon W, Lord GA, et al. Circulating anions usually associated with the Krebs cycle in patients with metabolic acidosis. Crit Care. 2005;9:R591–5. doi: 10.1186/cc3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen MJ, Serkova NJ, Wiener-Kronish J, et al. 1H-NMR-based metabolic signatures of clinical outcomes in trauma patients--beyond lactate and base deficit. J Trauma. 2010;69:31–40. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e043fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darlington DN, Gann DS. Adenosine stimulates NA/K ATPase and prolongs survival in hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2005;58:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000151185.63058.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conlay LA, Evoniuk G, Wurtman RJ. Endogenous adenosine and hemorrhagic shock: effects of caffeine administration or caffeine withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4483–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung CS, Chu KM, Tseng CJ, et al. Adenosine in hemorrhagic shock: possible role in attenuating sympathetic activation. Life Sci. 1987;41:1375–82. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koscso B, Trepakov A, Csoka B, et al. Stimulation of A2B adenosine receptors protects against trauma-hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9:427–32. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9362-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemann CU, Choi S, Behrends M, et al. Mild hypothermia protects obese rats from fulminant hepatic necrosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Surgery. 2006;140:404–12. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Yan S, Ji C, et al. Metabolomic changes and protective effect of (L)-carnitine in rat kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35:373–81. doi: 10.1159/000336171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, Higashino K. Enzymes involved in purine metabolism--a review of histochemical localization and functional implications. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:1321–40. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shoaie S, Karlsson F, Mardinoglu A, et al. Understanding the interactions between bacteria in the human gut through metabolic modeling. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2532. doi: 10.1038/srep02532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenves AZ, Kirkpatrick HM, 3rd, Patel VV, et al. Increased anion gap metabolic acidosis as a result of 5-oxoproline (pyroglutamic acid): a role for acetaminophen. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;1:441–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01411005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao de la Barca JM, Bakhta O, Kalakech H, et al. Metabolic signature of remote ischemic preconditioning involving a cocktail of amino acids and biogenic amines. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003891. pii: e003891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olenchock BA, Moslehi J, Baik AH, et al. EGLN1 Inhibition and Rerouting of alpha-Ketoglutarate Suffice for Remote Ischemic Protection. Cell. 2016;164:884–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakuragawa T, Hishiki T, Ueno Y, et al. Hypotaurine is an energy-saving hepatoprotective compound against ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat liver. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;46:126–34. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.09-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wohlauer MV, Moore EE, Harr J, et al. Cross-transfusion of postshock mesenteric lymph provokes acute lung injury. J Surg Res. 2011;170:314–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.