Abstract

The selective in vitro anti-tumor mechanisms of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) and plasma-activated media (PAM) follow a sequential multi-step process. The first step involves the formation of primary singlet oxygen (1O2) through the complex interaction between NO2− and H2O2. 1O2 then inactivates some membrane-associated catalase molecules on at least a few tumor cells. With some molecules of their protective catalase inactivated, these tumor cells allow locally surviving cell-derived, extracellular H2O2 and ONOO─ to form secondary 1O2. These species continue to inactivate catalase on the originally triggered cells and on adjacent cells. At the site of inactivated catalase, cell-generated H2O2 enters the cell via aquaporins, depletes glutathione and thus abrogates the cell’s protection towards lipid peroxidation. Optimal inactivation of catalase then allows efficient apoptosis induction through the HOCl signaling pathway that is finalized by lipid peroxidation. An identical CAP exposure did not result in apoptosis for nonmalignant cells. A key conclusion from these experiments is that tumor cell-generated RONS play the major role in inactivating protective catalase, depleting glutathione and establishing apoptosis-inducing RONS signaling. CAP or PAM exposure only trigger this response by initially inactivating a small percentage of protective membrane associated catalase molecules on tumor cells.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Cancer, Cell biology, Chemical biology, Oncology, Physics

Introduction

Malignantly transformed cells (early stages of oncogenesis) are subject to elimination through selective apoptosis induction based on intercellular signaling, involving reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS). This process, based on the HOCl or the ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling pathway, has been previously described in detail1–4 (reviewed in refs5–8). Briefly, this apoptosis-inducing RONS signaling exploits the fact that transformed cells express unusually large concentrations of membrane-associated NADPH oxidase (NOX1), resulting in high concentrations of extracellular superoxide anions (O2⋅−). Some of this O2⋅− can dismutate to H2O2 spontaneously or through the action of membrane-associated superoxide dismutase (SOD). DUOX-coded peroxidase derived either from the transformed cells themselves or from neighbouring nonmalignant cells, converts this H2O2 into HOCl and in this way initiates the HOCl signaling pathway1,3,8. The interaction between HOCl and NOX1-derived superoxide anions (O2⋅−) then yields ⋅OH radicals that cause lipid peroxidation. Alternatively, the ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling pathway may be established through the reaction between superoxide anions (O2⋅−) and ⋅NO, resulting in the formation of ONOO− H+ derived from membrane-associated proton pumps then leads to the formation of ONOOH, which spontaneously decomposes into ⋅NO2 and lipid peroxidating ⋅OH radicals2,7. If intracellular antioxidants - principally glutathione - are not abundant enough to completely repair this ⋅OH-mediated damage, a caspase-9/caspase-3 associated apoptosis sequence is initiated. We refer to this sequence of events leading to transformed cell apoptosis as intercelluar “HOCl signaling” or “NO/peroxynitrite signaling”, respectively. These two pathways seem to be mutually exclusive7,9.

Tumor cells escape this apoptotic signaling primarily through expression of membrane-associated catalase9–13. This catalase efficiently eliminates H2O2 near the cell membrane, and in this way prevents HOCl synthesis and apoptosis-inducing HOCl signaling. Membrane-associated catalase efficiently interferes also with ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling through oxidation of ⋅NO and decomposition of ONOO−7,9. Interference of membrane-associated catalase with both signaling pathways therefore results in tumor survival. Inactivating tumor membrane-associated catalase is therefore a potentially attractive way to re-activate intercellular RONS-dependent apoptosis-inducing signaling5,6,9,14. It has been established that generation of singlet delta O2 (1O2) outside the cell membrane is capable of selectively inactivating membrane associated catalase, thereby re-activating intercellular RONS-driven apoptosis-inducing signaling15. It had been previously hypothesized that the observed selective anti-tumor effects of CAP might be related to this process involving 1O216–18. The present article reports measurements and analyses testing this hypothesis.

The gaseous and liquid phase of cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) contains electrons, photons, as well as radical and nonradical reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) such as superoxide anions (O2⋅−), hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2⋅), atomic oxygen (O), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH), singlet oxygen (1O2), ozone (O3), nitric oxide (⋅NO), nitrogen dioxide (⋅NO2), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), dichloride radicals (Cl2⋅−) and hypochloride anions (OCl−) (summarized in refs17,19–21; please find detailed references under Suppl. Materials). CAP-derived RONS, created in the gas phase and transferred to liquid medium, represent a unique scenario of RONS chemical biology, based on variable life-times, free diffusion path lengths and multiple potentials of interactions.

The treatment of liquid media with CAP results in the generation of plasma-activated medium (PAM) that maintains the major biological effects of CAP, though it only contains long-lived species from CAP, such as nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−) and H2O222–25. Girard et al.23 and Kurake et al.24 already recognized that a synergistic effect between H2O2 and NO2− was essential for its biological effect. Both groups, as well as Jablonowski and von Woedtke26 suggested a potential role of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) that is generated through the interaction between NO2− and H2O227,28.

Cold atmospheric plasma (CAP) and plasma-activated medium (PAM) cause impressive antibacterial and antiviral effects, as well as beneficial effects for wound healing and the treatment of actinic keratosis29–35 (for review see refs20,21). CAP and PAM also establish promising antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo, in a very broad variety of tumor systems (reviewed in refs20,21,32–41). Clinical application of CAP for tumor therapy gave the first encouraging results in the absence of severe side effects42.

In most studies that directly compared tumor cells with nonmalignant cells, CAP and PAM were found to act selectively towards malignant target cells in vitro and in vivo. Only a few reports claimed nonselective apoptosis-inducing effects of CAP or PAM (reviewed in refs17,21; please find detailed references in Supplementary Material). It has been suggested that this discrepancy might be resolved by standardization of CAP and PAM doses and composition21.

The response of tumor cells in vitro and tumors in vivo from many different tumor systems indicates that CAP and PAM must be targeting a general principle of tumor cells. However, the mechanisms underlying the selective antitumor effects of CAP and PAM are still a matter of scientific debate.

Keidar’s group suggested that the increased concentration of aquaporins on tumor cells43 was the key determinant of selective antitumor action of CAP and PAM, as it should allow for an increased influx of CAP- or PAM-derived H2O2 into tumor cells, compared to nonmalignant cells44,45. This would then result in tumor cell apoptosis through direct intracellular effects mediated by H2O2, potentially by intracellular Fenton reaction.

Van der Paal et al.46 suggested that the decreased cholesterol content of tumor cells compared to nonmalignant cells was the determining factor for selective CAP and PAM action directed towards tumor cells, as cholesterol has a hampering effect on the ingress of ROS into cells.

Both models are based on the concept that ROS/RNS in CAP and PAM are directly responsible for the induction of cell death in the target cells. In both models, H2O2 is the major effector from CAP and the only effector from PAM. Both models did not consider, however, that tumor progression leads to a phenotype that is characterized by increased resistance to exogenous H2O247–51. This tumor progression-associated resistance towards exogenous H2O2 is based on the expression of membrane-associated catalase9–12, Membrane-associated catalase protects tumor cells towards exogenous H2O2, but also oxidizes ⋅NO and readily decomposes peroxynitrite (ONOO−)9,12. Therefore, challenging cells with exogenous H2O2 or ONOO− generally causes a much stronger apoptosis-inducing effect on nonmalignant cells and cells from early stages of tumorigenesis (transformed cells) than on tumor cells12. From this perspective, it seems that the mechanism of a purely H2O2-based apoptosis induction in tumor cells could not achieve the observed selectivity between tumor and nonmalignant cells. Therefore, nonmalignant cells that do not express this protective membrane-associated catalase system are much more vulnerable to exogenous H2O2 than tumor cells9,12, despite their lower number of aquaporins43.

The protective function of membrane-associated catalase of tumor cells9,12 (reviewed in refs5,6,17,18) is frequently neglected in the literature, as tumor cells in generally express less catalase than nonmalignant cells12. The finding of an overall low concentration of catalase in tumor cells is, however, not at all in contradiction to the strong expression of catalase on the membrane of tumor cells. Compared to the low concentration of catalase in the total volume of the tumor cells, the high local concentration of catalase on the spatially restricted site of the membrane is not relevant. Therefore it is not recognized when the catalase content of disaggregated cells is determined. However, its functional relevance towards extracellular ROS/RNS is a dominant factor for protection towards exogenous RONS effects, whereas the low intracellular catalase concentration enhances intracellular RONS effects.

Bauer and Graves16 suggested an alternative model to explain the selective action of CAP and PAM on tumor cells16–18. This model was derived from the analysis of apoptosis induction (as summarized above) in nonmalignant cells, transformed cells and tumor cells by defined RONS9,12,15,52. It took into account that the outer membrane of tumor cells, in contrast to nonmalignant cells, is characterized by the expression of NOX1, catalase and SOD5,6,9,12,15,53,54. It was shown that 1O2 derived from an illuminated photosensitizer caused local inactivation of a few (membrane-associated) catalase molecules15. Catalase inactivation then seemed to allow H2O2 and ONOO− that are continuously generated by the tumor cells, to survive long enough to generate substantial amounts of secondary 1O2 through the reaction between H2O2 and ONOO−55. This was leading to further catalase inactivation and reactivation of intercellular apoptosis-inducing ROS signaling. Bauer and Graves16 and Bauer17,18 suggested that low concentrations of 1O2 from CAP, or derived through interaction of long-lived species in PAM, would interact with the surface of tumor cells, that carries NOX1, catalase and SOD, in the same way as shown before for extracellular 1O2 generated by a photosensitizer. Thus, CAP-and PAM-derived molecular species act as a trigger that utilizes the ability of tumor cells to induce a massive response, whereas it has no impact on the survival of nonmalignant cells. Nonmalignant cells lack the expression of NOX1, catalase and SOD on their surface. As long as the concentration of H2O2 is below an apoptosis-inducing level for nonmalignant cells, selective action of CAP and PAM towards tumor cells is feasible.

In a series of reconstitution experiments, Bauer confirmed that the long-lived species H2O2 and NO2− that are found in CAP and PAM, are sufficient to generate 1O2 at concentrations that allow for initial local inactivation of a few catalase molecules56. Their reaction chain starts with ONOO− formation through the reaction between NO2− and H2O227,28. ONOO− and residual H2O2 then interact and generate primary 1O255. This interaction is not direct, but seems to require several steps that utilize the decomposition of peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH) into nitrogen dioxide (⋅NO2) and ⋅OH radicals57,58, followed by the generation of hydroperoxyl radicals (HO2⋅) through the interaction between ⋅OH radicals and H2O259. Finally, peroxynitric acid (O2NOOH) is generated through the interaction between ⋅NO2 and HO2⋅60. After deprotonation of O2NOOH, the resultant peroxynitrate (O2NOO−) decomposes and generates 1O260,61 that causes local inactivation of catalase15,62,63. As a result, free tumor cell-derived H2O2 and ONOO− allow for massive generation of secondary 1O2 in an autoamplificatory mode. The process is followed by catalase inactivation and subsequent activation of intercellular HOCl signaling. However, HOCl signaling can only lead to apoptosis induction when a sufficient influx of H2O2 into the cells had caused glutathione depletion, as glutathione/glutathione peroxidase-4 counteract the effects of ∙OH-mediated lipid peroxidation. Interestingly, central elements of the anti-tumor mechanism based on H2O2 influx via tumor cell aquaporins, as proposed by Yan et al.44,45, would be overlapping with the proposed scenario. With membrane-associated catalase inactivated by 1O2, tumor cells would be expected to allow aquaporin-mediated influx of H2O2 into the cells. The resultant depletion of intracellular glutathione seems to be a prerequisite for efficient apoptosis induction after lipid peroxidation by HOCl signaling. Therefore, as described by Yan et al.44,45, inhibition of aquaporins should strongly inhibit PAM-mediated apoptosis induction. Our experimental findings are consistent with their findings. However, intruding H2O2 by itself does not seem to be sufficient to trigger apoptosis induction, even if the intracellular glutathione level has been lowered. Rather, even in the situation of glutathione depletion, apoptosis induction in tumor cells required site-specific ⋅OH generation at the membrane through HOCl/O2∙− interaction56. These findings also highlight the strength of site-directed ⋅OH effects compared to lower signal effectivity of random ⋅OH generation through Fenton chemistry.

In this paper, the mechanisms proposed by reconstitution experiments are verified by using a CAP source operating in ambient air in either streamer corona or transient spark regimes. The malignant cells are treated either “directly” or indirectly via PAM. We were aware that “direct” treatment of cells with CAP also implies that CAP-derived molecular species are first confronted with the overlaying medium, which may react with highly reactive species from CAP and thus select for longer-lived species

Materials and Methods

Materials

Table 1 presents a summary of enzyme inhibitors, reactive species scavengers, reactive species donors, mimetics, and antibodies used in the present study to elucidate apoptotic and protective mechanisms.

Table 1.

Summary of enzyme inhibitors, reactive species scavengers, reactive species donors, mimetics, and antibodies used in the present study to elucidate apoptotic and protective mechanisms.

| Purpose | Compound name | Compound abbreviation and standard working concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Singlet oxygen scavenger | Histidine | HIS 2 mM |

| Peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst | 5-, 10-, 15-, 20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato iron(III) chloride | FeTPPS 25 µM |

| NOX1 inhibitor | 4-(2-Aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride | AEBSF 100 µM |

| HOCl scavenger | Taurine | TAU 50 mM |

| Aquaporin inhibitor | AgNO3 | Ag+ 5 µM |

| Catalase inhibitor | 3-aminotriazole | 3-AT 25 mM |

| Catalase donation (bovine liver catalase) | Catalase | CAT 10 - 1000 U/ml |

| glutathione synthesis inhibitor | Buthionine sulfoximine | BSO 10 - 50 µM |

| ⋅OH scavenger | Manitol | MANN 20 mM |

| ⋅OH scavenger | Dimethylthiourea | DMTU 20 mM |

| NO donor | Dieethylamine NONOate | DEA NONOate 0.5 mM |

| HOCl donor | Sodium oxychloride | NaOCl as indicated |

| Generation of H2O2 | Glucose oxidase | GOX as indicated |

| Nitric Oxide Synthase inhibitor | N-omega-nitro-L-arginine methylester hydrochloride | L-NAME 2.4 mM |

| Proton pump inhibitor | Omeprazole | |

| Peroxidase inhibitor | 4-Aminobenzoyl hydrazide | ABH 150 µM |

| Caspase-3 inhibitor | Z-DEVD-FMK 50 µM | |

| Caspase-8 inhibitor | Z-IETD-FMK 25 µM | |

| Caspase-9 inhibitor | Z-LEHD-FMK 25 µM | |

| SOD mimetics | Mn(III) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-methylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin and Mn (III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin | MnTM-2PyP and MnTE-2-PyP 20 µM |

| Mn-SOD donation (E. coli) | Manganese superoxide dismutase | Mn-SOD 100 U/ml |

| ONOO− decomposition catalyst and O2− scavenger | Fe(III)tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin pentachlorideporphyrin pentachloride | FeTMPyP 25 µM |

| Catalase mimetic | chloro([2,2′-[1,2-ethanediylbis[(nitrilo-κN)methylidyne]]bis[6-methoxyphenolato-κO]]]-manganese | EUK-134 20 µM |

| Antibody for human superoxide dismutase (SOD) | cb 0989 (binding and neutralizing) cb 0987 (binding without neutralization) |

The NOX1 inhibitor 4-(2-Aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), the aquaporin inhibitor AgNO3, the catalase inhibitor 3-aminotriazole (3-AT), the inhibitor of glutathione synthesis buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), catalase from bovine liver, the ⋅OH radical scavenger dimethylthiourea, NaOCl (for the generation of HOCl), the fast decaying ⋅NO donor dieethylamine NONOate (DEA NONOate), glucose oxidase (GOX), the singlet oxygen (1O2) scavenger histidine, the ⋅OH radical scavenger mannitol, the NOS inhibitor N-omega-nitro-L-arginine methylester hydrochloride (L-NAME), the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole, the HOCl scavenger taurine, Mn-SOD from E. coli, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Schnelldorf, Germany).

The peroxidase inhibitor 4-Aminobenzoyl hydrazide (ABH) was obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Inhibitors for caspase-3 (Z-DEVD-FMK), caspase-8 (Z-IETD-FMK) and caspase-9 (Z-LEHD-FMK) were obtained from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden-Nordenstadt, Germany).

The ONOO− decomposition catalyst 5-, 10-, 15-, 20-Tetrakis(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrinato iron(III) chloride (FeTPPS), the SOD mimetics Mn(III) 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-methylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (MnTM-2PyP) and Mn (III) meso-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin (MnTE-2-PyP), as well as Fe(III)tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin pentachlorideporphyrin pentachloride (FeTMPyP, a ONOO− decomposition catalyst and superoxide anion scavenger) were obtained from Calbiochem (Merck Biosciences GmbH, Schwalbach/Ts, Germany).

The catalase mimetic EUK-134 [chloro([2,2‘-[1,2-ethanediylbis[(nitrilo-κN)methylidyne]]bis[6-methoxyphenolato-κO]]]-manganese was a product of Cayman (Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A.) and was obtained from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany).

Single domain antibodies directed towards human SOD (cb 0989 (binding and neutralizing) and cb 0987 (binding without neutralization) have been recently described53.

All small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used in this study were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and are described in detail under Methods.

Detailed information on inhibitors has been previously published2,9–11,64,65. The site of action of inhibitors and scavengers has been presented in detail in the supplementary material of refs64,65.

Cells and media for cell culture

The human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line MKN-45 (ACC 409) (established from the poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach (medullary type) of a 62 year-old woman), was purchased from DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany. MKN-45 were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

The human Ewing sarcoma cell line SKN-MC and human neuroblastoma cell line SHEP were obtained from Dr. J. Roessler, Dep. of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University Medical Center Freiburg. SKN-MC cells and SHEP grow in monolayer and were kept in Eagles MEM, containing 5% FBS and supplements as described above.

The human HPV-16-positive cervix adenocarcinoma cell line SIHA was obtained from the American type culture collection. The cells were kept in Eagles MEM, containing 5% FBS and supplements.

The human non-malignant diploid fibroblasts Alpha-1 were isolated in the Diagnostic Unit of our Institute and have been described in Riethmüller et al.15.

Fetal bovine serum (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) was heated for 30 minutes at 56 °C prior to use. Medium was supplemented with penicillin (40 U/ml), streptomycin (50 µg/ml), neomycin (10 µg/ml), moronal (10 U/ml) and glutamine (280 µg/ml). Care was taken to avoid cell densities below 300 000/ml and above 106/ml.

Methods

The plasma sources

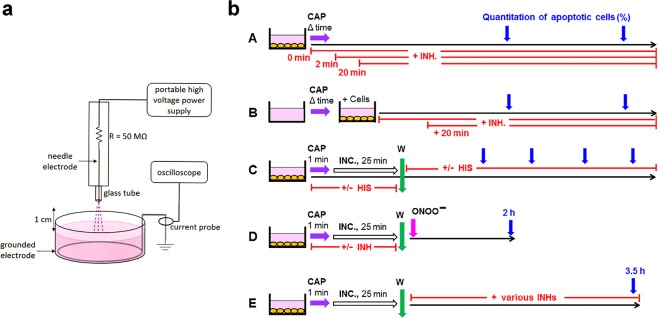

Portable air plasma ‘corona pen’ plasma source used here employs a neon-sign transformer with a rectifier and a high voltage multiplier and was developed in the framework of the frugal plasma biotech applications66 (Fig. 1a). A high voltage needle electrode was inserted in a quartz tube. A DC-positive streamer corona discharge was generated on the needle electrode in ambient air, in a geometry similar to the discharge previously presented in67,68. The grounded electrode was a tin wire submerged in the cell culture medium at the bottom of the container. The distance of the needle tip to the medium surface was kept at 1 cm. The plasma discharge was directly hitting the liquid surface of the medium, as shown in Fig. 1(a). The discharge voltage was kept at 10.7 kV and the maximum streamer pulse current was typically 17 mA with a pulse frequency of 10 kHz. The streamer corona discharge generates RONS, such as O3, NOx, and ⋅OH radicals at very low deposited power (<0.1 W).

Figure 1.

The plasma source and the experimental procedures used in this study. (a) Schematic drawing of the portable plasma source used in this study. The portable plasma source enabled operation in the corona and transient spark regime, as described under Methods69–71. (b) Experimental procedures. A. Tumor cells were treated with CAP for varying times, combined with the addition of specific inhibitors/scavengers (INH) at defined time points. Apoptosis induction was quantified at different times. B. The same princples as shown under A were applied, except that medium was treated with CAP in the absence of cells, and was then transferred to the cells. C. Tumor cells were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min incubation in the same medium. After a washing step, incubation was continued in fresh medium. The 1O2 scavenger histidine was present either before or after the washing step. Apoptosis induction was determined kinetically. D. Tumor cells were treated with CAP (or PAM) in the absence or presence of defined inhibitors/scavenger and incubated for 25 minutes in the same medium. After a washing step, the degree of inactivation of membrane-associated catalase was determined through a ONOO− challenge and determination of ONOO− mediated apoptosis induction12. E. Tumor cells were treated with CAP for 1 min and incubated in the same medium for 25 min. After a washing step, further cultivation of the cells was performed in the absence or presence of defined inhibitors/scavengers (INHs) that allowed to define the molecular species involved in apoptosis-inducing signaling after catalase inactivation.

The portable plasma source also enabled operation in the transient spark regime, described in greater details in69–71. In the same way, the grounded wire was submerged in the medium, the high voltage needle electrode was 1 cm apart from its surface and the discharge was directly hitting the liquid surface. Higher voltage was applied (13.3 kV) to enable the plasma discharge to operate at the streamer-to-spark transition regime, with high (15 A amplitude) but very short (<100 ns) spark current pulses with a repetitive frequency of 1.1 kHz. The transient spark discharge also generates RONS, especially NOx, OH radicals and H2O2 at very relatively low deposited power (~1–2 W).

Treatment of cells with cold atmospheric plasma (CAP)

All treatments were performed in 24 well tissue culture clusters, 1 ml of medium and a grounded electrode. MKN-45 cells were used at a density of 125 000 cells/ml. The cells remain in suspension and only few cells attach firmly. SIHA; Alpha-1, SHEP and SKN-MC cells were treated as monolayers (50 000 cells/assay) as soon as the cells had firmly attached.

Standard treatment with CAP was by the streamer CORONA regime, with a distance of the plasma source from the top of the medium of 1 cm. Typical electrical parameters were voltage 10.7 kV, pulse amplitude 17 mA, and pulse frequency 10 kHz. The standard time of treatment was 1 min, unless otherwise indicated.

After treatment with CAP, the cells were either further incubated at 37 °C for the indicated times or subjected to washing steps and resuspension in fresh medium, depending on the protocol of the experiments. These manipulations, which were essential for the analysis, are specified in the legends of the respective figures. The final goal was to determine the percentage of apoptotic cells induced by the treatment.

In some cases (Supplementary Figs 7–10), CAP treatment was in the transient SPARK regime, with typical electrical parameters voltage 13.3 kV, pulse amplitude 15 A, and pulse frequency 1.1 kHz.

Corona discharges are known to induce “ionic wind”, i.e. a gas flow is induced by the motion of ions in the electric field. In our case the ionic wind blows in the direction from the needle towards the liquid surface and reaches velocities of a few m/s. This consequently induces some medium convection and mixing, dependent on the electrical discharge parameters, as well as the liquid container geometry and the liquid volume. In the transient spark regime, the ionic wind is coupled with the hydrodynamic pressure waves due to the short, strong current pulses, both of which can induce some convections in the liquid. These phenomena and their significance are subject of our future investigations. In all experiments presented in this paper, the electrical discharge parameters, as well as geometries and liquid containers and volumes were kept the same to eliminate their potential influence on the biochemical and biological responses.

Generation and application of plasma-activated medium (PAM)

Complete medium without cells was treated with CAP for 1 min, unless otherwise specified. After 10 min, PAM was added to the cells that had been prepared at higher cell density, to reach a final concentration of PAM between 80–50%, as indicated. In some experiments, PAM was first serially diluted and then equal volumes of the dilution steps and cells of double standard density were mixed.

Apoptosis induction mediated by exogenous ONOO−

Treatment with exogenous ONOO− allows to quantitatively monitor the activity of membrane-associated catalase as this enzyme decomposes exogenous ONOO−, whereas intracellular catalase cannot reach exogenous ONOO− before the compound attacks the cell membrane12. After the indicated pretreatments at a density of 125 000 cells/ml, the cells were washed several times through centrifugation and resuspension in fresh medium and then were seeded at a density of 12 500 cells/100 µl. The cells received 100 µM AEBSF to prevent autocrine apoptosis induction and negative interference of cell-derived H2O2 with ONOO−. ONOO− was diluted in ice-cold PBS immediately after controlled thawing and was rapidly applied to the cells. This approach allows to focus on apoptosis induction by exogenous ONOO−, which is an indication for the inactivation of membrane-associated catalase. Apoptosis criteria were used as defined below.

Determination of the percentage of apoptotic cells

After the indicated time of incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by inverted phase contrast microscopy based on the classical criteria for apoptosis, i.e., nuclear condensation/fragmentation or membrane blebbing9,65,72,73. The characteristic morphological features of intact and apoptotic cells, as determined by inverted phase contrast microscopy have been published9,14,65,74,75. At least 200 neighbouring cells from randomly selected areas were scored for the percentage of apoptotic cells at each point of measurement. Control assays ensured that the morphological features ‘nuclear condensation/fragmentation’ as determined by inverse phase contrast microscopy were correlated to intense staining with bisbenzimide and to DNA strand breaks, detectable by the TUNEL reaction2,14,74,75. A recent systematic comparison of methods for the quantitation of apoptotic cells has shown that there is a perfect coherence between the pattern of cells with condensed/fragmented nuclei (stained with bisbenzimide) and TUNEL-positive cells in assays with substantial apoptosis induction, whereas there was no significant nuclear condensation/fragmentation in control assays14,65. Further controls ensured that ROS-mediated apoptosis induction was mediated by the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, involving caspase-9 and caspase-34,14.

Knockdown by treatment with specific small interfering ribonucleic acids (siRNAs)

Techniques and siRNA described in this and the next subchapter are identical to those described in refs3,4,9,12,13,76 and highly reproducible.

SiRNAs were obtained from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany).

The following siRNAs were used

Control siRNA which does not affect any known target in human and murine cells (siCo):

sense: r(UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU)dTdT,

antisense: CGUGACACGUUCGGAGAA)dTdT;

SiRNA directed towards human NADPH oxidase-1 (NOX1)

custom-made siRNA directed towards NADPH oxidase-1 variant a (siNOX1-a): target sequence: CCG ACA AAT ACT ACT ACA CAA

sense: r(GAC AAA UAC UAC UAC ACA A)dTdT,

antisense: r(UUG UGU AGU AGU AUU UGU C)dGdG;

SiRNAs were dissolved in suspension buffer supplied by Qiagen at a concentration of 20 µM. Suspensions were heated at 90 °C for 1 minute, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 60 minutes. Aliquots were stored at −20 °C.

Before transfection, 88 µl of medium without serum and without antibiotics were mixed with 12 µl Hyperfect solution (Qiagen) and the required volume of specific siRNA or control siRNA to reach the desired concentration of siRNA during transfection (the standard concentration of siRNA was 24 nM for MKN-45 cells). The mixture was treated by a Vortex mixer for a few seconds and then allowed to sit for 10 minutes. It was then gently and slowly added to 300,000 MKN-45 cells in 1 ml RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and antibiotics (12-well plates). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Transfected cells were centrifuged and resuspended in fresh medium at the required density before use.

Determination of the efficiency of siRNA-mediated knockdown

The siRNA transfection system as described above had been optimized to allow a reproducible transfection efficiency of more than 95% of the cells and to avoid toxic effects (Bauer, unpublished data).

The efficiency of knockdown by siNOX1 was based on functional SOD-dependent quantitative assay3,76 and was more than 90%.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, assays were performed in duplicate. Quantitative data are presented as means ± standard deviations. The statistical analysis comprised the comparison of groups such as assay without apoptosis induction/assay with apoptosis inducer or assay without inhibitor/assay with inhibitor. Therefore, the differences between two groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test (two-tailed), with N = 500 in all tests, and double checked with the Yates continuity corrected chi-square test. The confidence interval used was 95%. P < 0.01 was defined as “significant”; P < 0.001 as “highly significant”. The modules for the calculation of the tests were taken from https://www.quantitativeskills.com/sisa/statistics/t-test.htm (t test) and from http://www.quantpsy.org/chisq/chisq.htm (Chi-square test).

Strategy and design of our analysis

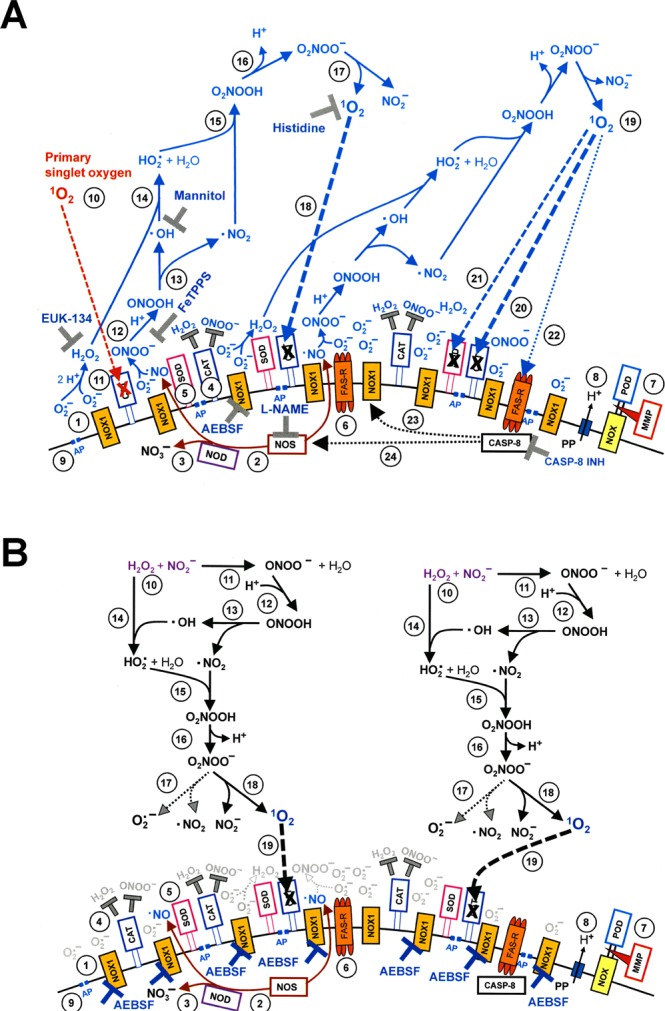

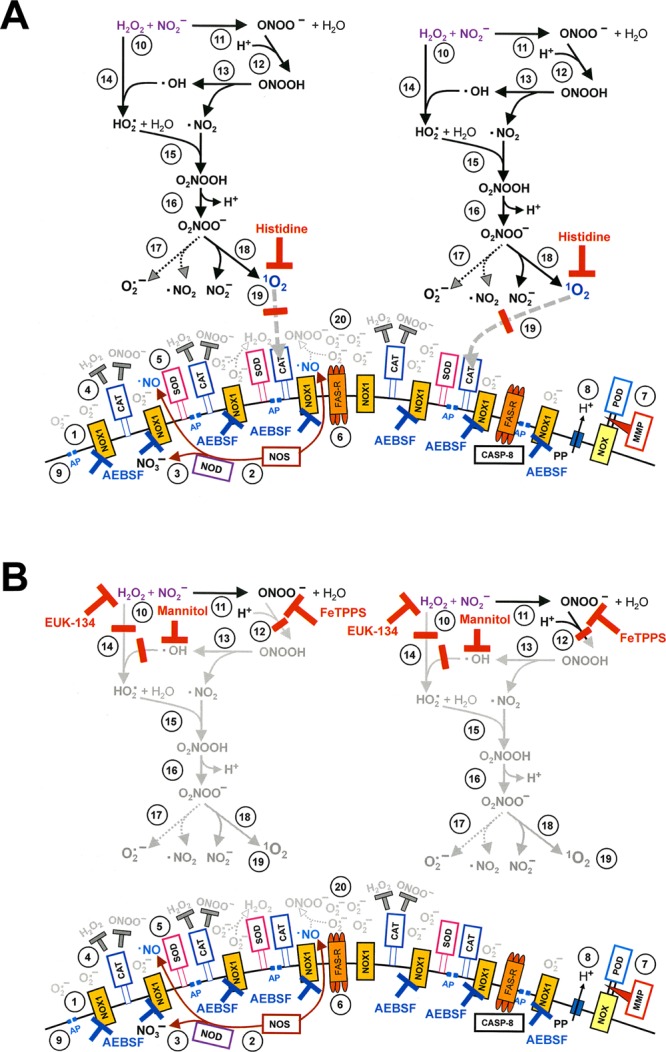

Our study was primarily based on the quantitation of apoptosis induction in human tumor cells by CAP and PAM in vitro. The application of defined inhibitors and scavengers at different time points was used to pinpoint the molecular species that determined the different steps in this scenario. The basic experimental procedures used in this analysis are schematically described in Fig. 1(b). Treatment of the cells with CAP for varying time, combined with addition of inhibitors (regime A, Fig. 1(b)) gave first information on the role of central players like 1O2, O2⋅−, ONOO− and aquaporins (Results will be shown in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

CAP and PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells. (a) CAP- and PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells is dependent on singlet oxygen (1O2). A-D: Treatment with CAP. MKN-45 tumor cells in medium were treated with CAP for either 20 sec or 1 min, either in the absence of the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS) (2 mM) or with HIS addition at the indicated times. Control assays were not treated with CAP. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 2 and 5 h. E,F: The effect of PAM. Medium was treated with CAP for 20 or 60 sec, or not treated. It was then added to an equal volume of MKN-45 cells at double standard density, in the absence or presence of HIS. The final volume was 100 µl. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 2 and 5 h. These results show that 1O2 generated by long-lived species that are generated through treatment of medium with CAP are sufficient to trigger apoptosis induction in tumor cells. The 1O2-dependent process seems to be completed within less than half an hour. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by CAP or PAM under all conditions is highly significant (p < 0.001). The inhibition by histidine added a 0 or 2 min is highly significant (p < 0.001) in all assays. The differences between the effect of histidine added at 20 min or 0/2 min is highly significant (p < 0.001). (b) CAP-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells: Dependency on singlet oxygen (1O2), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), superoxide anions (O2⋅−) and aquaporins. MKN-45 tumor cells were treated with CAP in the absence or presence of the indicated scavengers/inhibitors (A: the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS) (2 mM); B: the ONOO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS (25 µM); C: the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF (100 µM); D: the aquaporine inhibitor Ag+ (5 µM)). Scavengers/inhibitors had been added either 10 min before CAP treatment, or 2 min or 20 min after CAP treatment. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 4.5 h. These results show that CAP-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells involves a very fast 1O2 - and ONOO−-dependent process, as well as longer-lasting processes in which superoxide anions and aquaporins are involved. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by CAP is highly significant (p < 0.001). Inhibition of CAP-mediated apoptosis induction by histidine and FeTPPS added at −10 or 2 min, as well as inhibition by AEBSF or Ag+, added at all time points, is highly significant (p < 0.001).

This procedure was also successfully applied to the study of PAM action (regime B, Fig. 1(b)) (Results shown in Fig. 3a). Regime C in Fig. 1(b) describes a kinetic analysis of apoptosis induction after CAP treatment, in which the singlet oxygen scavenger histidine was present either during CAP treatment plus the subsequent incubation step for 25 min, or thereafter (Fig. 3(b)). This approach allowed to differentiate between an early, 1O2 – dependent step and a subsequent 1O2 – independent step. This approach was also applied to PAM treated cells (not explicitely shown in Fig. 1(b). The kinetic analysis of CAP- and PAM-mediated apoptosis induction will be shown in Fig. 3b. Based on this information, it was possible to study in detail the initial step of CAP (and PAM) action through a ONOO− challenge, that allows to monitor the inactivation of membrane-associated catalase12 (regime D in Fig. 1(b)). The addition of various inhibitors/scavengers during the short treatment with CAP or PAM allowed to define the molecular species involved in this step. Results will be shown in Figs 4 and 5. Finally, the regime described under E in Fig. 1(b) was based on an initial treatment of cells with CAP, which was followed by an incubation in the absence or presence of various inhibitors. This experiment allowed to define the molecular species involved in intercellular apoptosis-inducing RONS signaling after CAP-mediated inactivation of catalase. These results will be shown in Fig. 6. Further experimental approaches, not included in this scheme, were studying the role of aquaporins and intracellular glutathione and the role of proton pumps. Finally, the window of CAP and PAM doses for selective action towards tumor cells was defined.

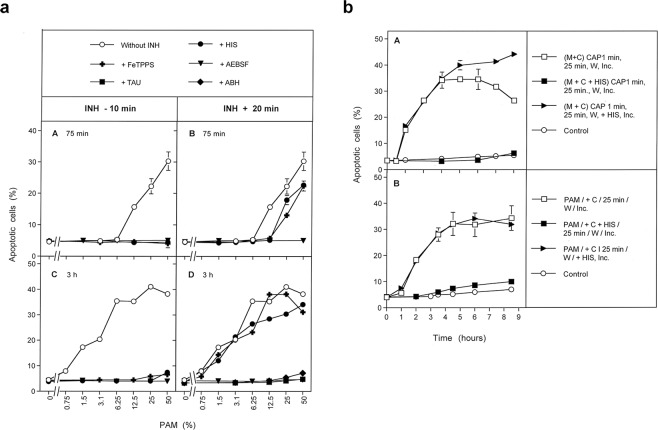

Figure 3.

PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells. (a) Inhibition profile of PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells. Medium was treated with CAP for 1 min in the absence of cells for the generation of PAM. PAM was serially diluted and added at equal volumes to MKN-45 cells to reach a final volume of 100 µl and cell density of 12 500 cells/100 µl. The indicated inhibitors/scavengers (INH) (the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS) (2 mM), the ONOO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS (25 µM); the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF (100 µM); the HOCl scavenger taurine (TAU) (50 mM) and the the peroxidase inhibitor 4-aminobenzoyl hydrazide (ABH) (150 µM)) had been either added 10 min before addition of PAM to the cells or 20 min after addition of PAM. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 75 min (A,B) and 3 h (C,D), as indicated. PAM causes concentration-dependent apoptosis induction in tumor cells. This seems to involve a very short initial process (mediated by 1O2 and ONOO−) and subsequent HOCl signaling, as seen by the involvement of peroxidase and HOCl. Superoxide anions (O2⋅−) may have a dominant role in both processes. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by 12.5 percent PAM and higher concentrations, determined at 75 min, and by 1.5% and higher, measured at 3 hrs is highly significant (p < 0.001.) Inhibition of PAM-mediated apoptosis induction by all inhibitors, added at −10 min is highly significant (p < 0.001).The differences of the inhibitors added at the two time points are highly signficant (p < 0.001). (b) Kinetics of CAP- and PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells. A. MKN-45 cells in medium (M + C) were treated with CAP for 1 min and were further incubated at 37 °C for 25 min (“25 min”). The cells were washed (W) (two cycles) and resuspended in fresh medium. Parallel assays contained histidine (HIS) (2 mM) during CAP treatment and the subsequent 25 min incubation, or received HIS after the washing step. Control assays were not treated with CAP. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined kinetically during the incubation (Inc.) that followed the washing step. Time point zero is defined by resuspension of the cells in fresh medium after the washing step. B. PAM was generated through treatment of medium without cells with CAP for 1 minute. PAM was added to MKN-45 cells (90 µl PAM plus 10 µl cells of 10 fold standard density) and further incubated at 37 °C for 25 min. The cells were washed (2 cycles) and resuspended in fresh medium. Parallel assays contained histidine either during the 25 min incubation step, or received histidine after the washing step. Control assays were not treated with CAP. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined kinetically. These results show that CAP- and PAM-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells are dependent on singlet oxygen and show similar kinetics. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction mediated by CAP after 1 h and later, and by PAM after 2 h and later is highly significant (p < 0.001). The inhibitory effect of histidine added during CAP or PAM treatment is highly significant (p < 0.001).

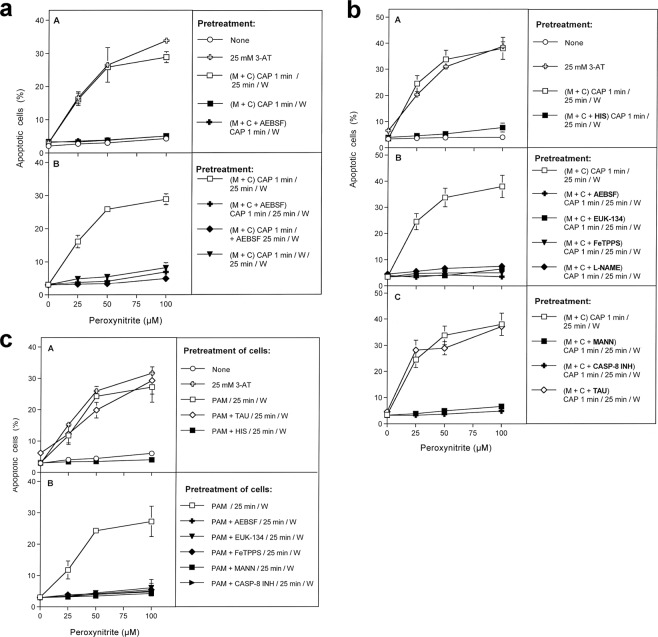

Figure 4.

Inactivation of membrane-associated catalase of tumor cells by CAP and PAM. (a) Basic experiments. A. MKN-45 cells remained untreated (open circle) or were treated with 25 mM of the catalase inhibitor 3-AT (open cross), before they were challenged with peroxynitrite (ONOO−) in the presence of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF (100 µM). In parallel, cells were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min in the same medium before they were washed (W), resuspended in fresh medium containing 100 µM AEBSF, and were challenged with ONOO− (open square). Alternatively, cells in control medium (closed square) and cells in medium containing 100 µM AEBSF (closed cross) were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed directly by a washing step (W) and immediate challenge with ONOO− in the presence of 100 µM AEBSF. B. Cells in medium were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed by an incubation step of 25 min in the same medium, before the cells were washed (W) and resuspended in fresh medium (open square). This regime was modified by adding AEBSF (100 µM) either before CAP treatment (closed cross) or at the beginning of the 25 min incubation (closed diamond), or by washing the cells immediately after the CAP treatment and incubating them for 25 min in fresh medium, followed by a second washing step (closed triangle). All assays were challenged with increasing concentrations of ONOO−, in the presence of 100 µM AEBSF. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined 2 h after addition of ONOO−. The results show that catalase inhibition by 3-AT or treatment of the cells with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min of incubation in the same medium caused sensitization towards ONOO−, indicative for catalase inactivation. Catalase inactivation through CAP treatment required that the long-lived species generated by CAP need to interact with the tumor cells during the 25 min incubation step and that NOX1 was not inhibited during this incubation step. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by all concentrations of ONOO−, in the presence of 3-AT or after pretreatment with CAP is highly significant (p < 0.001). The inhibitory effect of AEBSF is highly significant (p < 0.001). (b) Elucidation of the biochemical mechanism of CAP-mediated inactivation of catalase. (A) MKN-45 cells were not pretreated or treated with 25 mM of the catalase inhibitor 3-aminotriazole (3-AT), received 100 µM of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF and were then challenged by increasing concentrations of peroxynitrite (ONOO−). The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined 2 h after the ONOO− challenge. In parallel, MKN-45 cells were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min incubation in the same medium and three cycles of washing (W) (“(M + C) CAP 1 min/25 min/W”). In addition, the same regime was performed in the presence of the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS) during CAP treatment and the 25 min incubation step (“(M + C + HIS) CAP 1 min/25 min/W”) 100 µM AEBSF were then added and the cells were challenged with increasing concentrations of ONOO−. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined two hours after addition of ONOO−. B,C: CAP treatment, 25 min incubation in the same medium, washing and ONOO−challenge were performed as described under A. This regime was modified by the presence of the following compounds during CAP treatment and the incubation step: the NOX inhibitor AEBSF (100 µM); the catalase mimetic EUK-134 (20 µM), the ONOO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS (25 µM); the NOS inhibitor L-NAME (2.4 mM); the ⋅OH radical scavenger mannitol (MANN) (20 mM), caspase-8 inhibitor (25 µM) and the HOCl scavenger taurine (TAU) (50 mM. These findings show that CAP-mediated inactivation of tumor cell protective catalase requires the action of 1O2, NOX1-derived O2⋅−, H2O2, ONOO−, NOS-derived ⋅NO, ⋅OH radicals and caspase-8, whereas it does not require HOCl. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by ONOO− after CAP treatment is highly significant (p < 0.001). The inhibitory effects of all inhibitors,with the exception of taurine, are highly significant (p < 0.001). (c) Inactivation of protective catalase of tumor cells by PAM. PAM was generated by CAP treatment of the medium without cells for 1 min. Tumor cells were treated with 50% of PAM for 25 min at 37 °C, in the absence of inhibitors or in the presence of 50 mM of the HOCl scavenger taurine (TAU), 2 mM of the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS), 100 µM of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF, 20 µM of the catalase mimetic EUK-134, 25 µM of the ONOO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS, 20 mM of the ⋅OH radical scavenger mannitol (MANN) or 25 µM of caspase-8 inhibitor. Incubation was followed by three cycles of washing steps, followed by the addition of 100 µM AEBSF and the challenge with the indicated concentrations of ONOO−. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 2 h. Untreated cells and cells treated with 25 mM 3-AT served as controls. The results show that PAM efficiently inactivates tumor cell protective catalase, utilizing the same molecular species as shown for direct CAP treatment in Fig. 4b. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by all concentrations of ONOO−, after pretreatment with 3-AT or PAM is highly significant (p < 0.001). The effect of all inhibitors, except taurine, is highly significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Demonstration of catalase inactivation by primary singlet oxygen (1O2) derived from long-lived species of CAP-treated medium or from the gaseous phase of CAP. (a) Catalase inactivation solely by primary singlet oxygen generated from long-lived species of CAP treated medium requires extending the time of CAP treatment and blocking the generation of secondary singlet oxygen (1O2). The experiment described in this Figure followed the same principles and used the same concentrations of inhibitors as described before in Fig. 4, but includes a variation of the time of CAP treatment. A confirms that the catalase inhibitor 3-AT as well as pretreatment of tumor cells with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min in the same medium allowed for inactivation of tumor cell protective catalase, as determined by a peroxynitrite (ONOO−) challenge. Part A also confirms that catalase inactivation is mediated by 1O2 (inhibition by histidine (HIS)) and that primary 1O2 is not sufficient for catalase inactivation under these conditions, as inhibition of NOX1 by AEBSF or NOS by L-NAME during pretreatment and incubation completely prevented catalase inactivation through inhibition of secondary singlet oxygen generation. B. When CAP treatment was extended to 3 min, followed by 25 min incubation in the same medium, significant catalase inactivation was determined despite the presence of L-NAME or AEBSF, i. e. even under conditions where secondary 1O2 generation is inhibited. C. As inactivation of catalase in the presence of AEBSF is inhibited by the parallel presence of either the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS), the ONOO− decomposition catalyst FeTPPS, the catalase mimetic EUK-134 or the ⋅OH radical scavenger mannitol (MANN), the underlying effect of primary 1O2 is confirmed and its generation through the interaction of long-lived species derived from CAP is assured. The action of 1O2directly derived from CAP is excluded as a significant effective source, as its potential action would not have been inhibited by either FeTPPS, mannitol or EUK-134. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction by all concentrations of ONOO−after treatment with CAP for 1 or 3 min is highly significant (p < 0.001). The effects of all inhibitors shown under A-C are highly significant (p < 0.001). There is no significant difference between the effects of L-NAME, AEBSF or their combination on apoptosis induction after 3 min CAP treatment and ONOO− challenge. (b) Demonstration of the effect of primary singlet oxygen (1O2) derived directly from the gaseous phase of CAP. The peroxynitrite (ONOO−) challenge was used for the determination of catalase inactivation as in the previous experiments. A. Extension of the treatment time of cells in medium (M + C) with CAP to 10 min resulted in massive inactivation of catalase, even if there was no further incubation step after CAP treatment ((M + C) CAP 10 min/W). When the generation of secondary 1O2 was prevented by the presence of the NOX inhibitor AEBSF (100 µM) during CAP treatment ((M + C + AEBSF) CAP 10 min/W), the degree of catalase inactivation was strongly lowered. Under these conditions, catalase inactivation must be due to primary 1O2 that may be generated by long-lived species from CAP-treated medium and/or by 1O2 directly derived from CAP. When the generation of secondary 1O2was inhibited by AEBSF and the generation of primary 1O2from long-lived species in CAP-treated medium was blocked through the addition of EUK-134 and FeTPPS, the degree of catalase inactivation was further reduced ((M,C,AEBSF, EUK-134, FeTPPS) CAP 10 min/W). This residual inactivation seemed to be mediated by primary singlet oxygen derived directly from CAP, as its effect was prevented through the presence of histidine in the assays (M,C,AEBSF, EUK-134, FeTPPS, HIS) CAP 10 min/W). Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment is highly significant for all concentrations of ONOO− (p < 0.001). CAP treatment in the presence of AEBSF caused highly significant apoptosis induction by ONOO− at 25 µM and higher, CAP treatment in the presence of AEBSF, EUK-134 and FeTPPS caused highly significant apoptosis induction at 50 µM ONOO− and higher (p < 0.001).

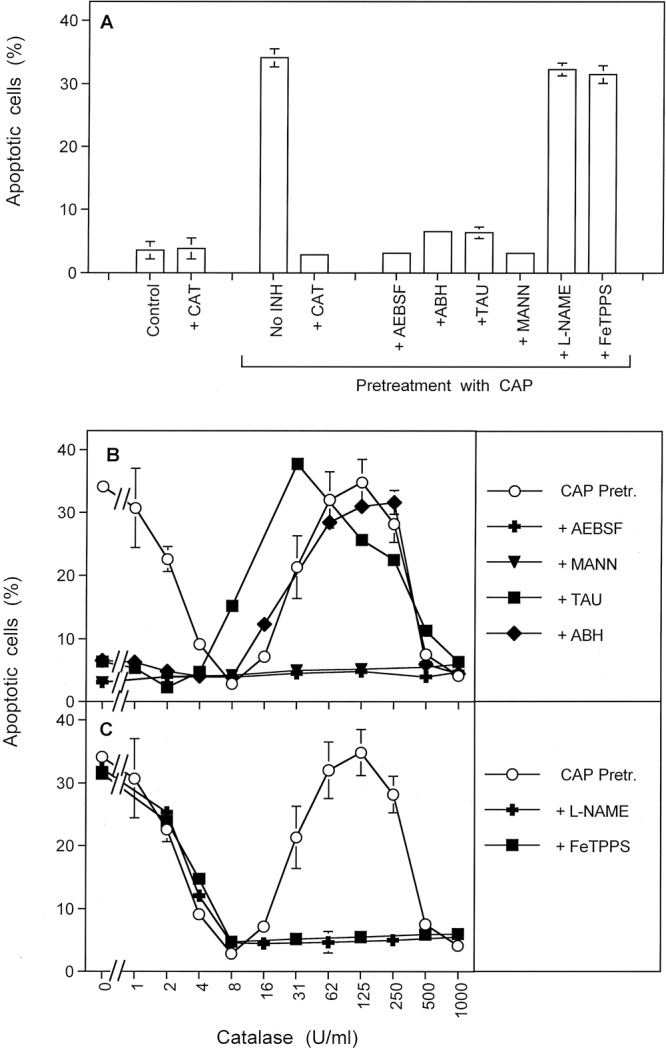

Figure 6.

Inactivation of membrane-associated catalase allows for reactivation of intercellular RONS-mediated apoptosis-inducing signaling. (a) Catalase inactivation through CAP treatment allows for reactivation of intercellular apoptosis-inducing HOCl signaling. Control assays: MKN-45 cells received 100 mM of the catalase inhibitor 3-AT or remained untreated (“control”) and were then incubated for 3.5 h. CAP pretreatment: MKN-45 cells were pretreated with CAP for 1 min, incubated in the same medium for 25 min and then subjected to three washing cycles. The cells received either no inhibitors or were cultivated in the presence of the indicated inhibitors for 3.5 h, before the percentages of apoptotic cells were determined. SOD and the SOD mimetics MnTM-2-Pyp or MnTE-2-PyP scavenge superoxide anions (O2⋅−) and generate H2O2, AEBSF prevents O2⋅− generation by NOX1, catalase and the catalase mimetic EUK-134 decompose H2O2, 4-aminobenzoyl hydrazide (ABH) inhibits peroxidase, taurine (TAU) scavenges HOCl, mannitol (MANN) and dimethyl urea (DMTU) scavenge ⋅OH radicals, L-NAME inhibits NOS, FeTPPS selectively decomposes peroxynitrite (ONOO−), FeTMPyP decomposes ONOO− and scavenges O2⋅−, histidine (HIS) scavenges 1O2, Ag+ inhibits aquaporins, caspase inhibitor specifically inhibit caspase-8 or caspase-3. Please find the respective inhibitor concentrations in Table 1. The results show that pretreatment with CAP plus incubation has the same effect as inhibition of catalase with 3-AT. Cell death after catalase inactivation by CAP is mediated by HOCl signaling, depends on aquaporine activity and is executed through caspase-3. It does not require ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling, caspase-8 or the action of 1O2. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment, as well as inhibition by all inhibitors except L-NAME, FeTPPS, histidine and caspase-8 inhibitor was highly significant (p < 0.001). (b). The effect of the ⋅NO donor DEA NONOate on intercellular apoptosis-inducing signaling after catalase inactivation by CAP treatment. Assays without pretreatment (“control”), treated with 25 mM of the catalase inhibitor 3-AT or with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min incubation, three cycles of washing and addition of the indicated inhibitors received 0.5 mM of the ⋅NO donor DEA NONOate. Parallel controls without pretreatment or treated with 3-AT or CAP remained free of DEA NONOate (Controls of the right side of the panel). The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined 2 h after addition of the ⋅NO donor. The results show that the addition of the ⋅NO donor had shifted apoptosis inducing signaling by cells with inactivated catalase to ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling, as inhibitors that specifically address HOCl signaling (like the peroxidase inhibitor ABH and the HOCl scavenger taurine (TAU)) were now effective, whereas cell death remained dependent on superoxide anions (O2−) and ⋅OH radicals. Inhibition by FeTPPS and the requirement for high concentrations of catalase for inhibition is indicative for ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling. The NOS inhibitor L-NAME remained without effect, as DEA NONOate was the dominating source for ⋅NO. Statistical analysis: Apoptosis induction after pretreatment with CAP and addition of DEA NONOate, as well as inhibition by all inhibitors except 10 U/ml catalase, EUK-134, ABH, taurine, L-NAME, histidine and caspase-8 inhibitor was highly significant (p < 0.001).

The experiments in the main part of this manuscript were performed with a CAP source operating in ambient air in the streamer corona regime. Supplementary information shows central data obtained through the application of a CAP source operation in the transient spark regime.

Results

Apoptosis induction by CAP and PAM

Cold atmospheric plasma, applied in the streamer corona regime, caused apoptosis induction in human MKN-45 gastric carcinoma cells (Fig. 2(a):A–D). Two hours after treatment, differences in CAP exposure time of 20 seconds to 1 minute resulted in slight, but significant differences in the apoptotic response, whereas at five hours past treatment, differences in the dose responses were only minor. Apoptosis induction in the tumor cells by CAP seemed to be mediated by a relatively fast singlet oxygen (1O2)-dependent process, as the presence of the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS) during the treatment completely prevented apoptosis induction, whereas the addition of HIS 20 minutes after CAP treatment only caused marginal inhibitory effects. The strong inhibitory effect of HIS added at two minutes after CAP treatment, demonstrates that 1O2 directly derived from CAP cannot be the major responsible agent, as 1O2 has an extremely short life time in the range of microseconds. This finding rather shows i) that CAP-treated medium generates 1O2 over a period of several to tens of minutes, and that the concentration of 1O2 generated during this time is actually required to trigger the observed biological effect.

Treatment of medium with CAP in the absence of cells, followed by subsequent transfer of this medium to tumor cells (i.e. formation of PAM), caused apoptosis induction in the same range of effectivity as direct treatment of cells by CAP (Fig. 2(a):E,F). This effect of “plasma-activated medium (PAM)” was also completely inhibited by the 1O2 scavenger histidine (HIS).

CAP-mediated apoptosis induction was dependent on CAP treatment time and on the density of the target cells, as shown in Supplementary Figs 1 and 2. The concentration response curve was characterized by a steep increase of the apoptotic response at low CAP treatment times, followed by a long-lasting plateau. CAP-dependent apoptosis induction was abrogated by the presence of 1O2 inhibitor HIS at all doses applied.

CAP-mediated apoptosis induction was dependent on an early and short-lasting singlet oxygen- and ONOO−-dependent step, which seemed to be completed within 20 minutes after CAP treatment (Fig. 2(b):A,B). In contrast, inhibition of NOX1 activity by AEBSF and inhibition of aquaporins through Ag+ prevented apoptosis even if the inhibitors had been added at a time point when the 1O2 and ONOO−-dependent step had already been completed (Fig. 2(b):C,D).

Apoptosis was induced in MKN-45 cells dependent on the concentration of PAM (Fig. 3(a)). A strong leftward shift of the concentration-response curve of PAM was observed with time (Fig. 3(a):AB versus Fig. 3(a):CD). This indicates substantial kinetic differences for apoptosis induction at higher and lower concentrations of PAM. Similar to CAP action, the effect of PAM was also characterized by a fast 1O2- and ONOO−-dependent step. This step seemed to be followed by a process that depended on (O2−), peroxidase and HOCl. In line with previous findings in model experiments performed with long-lived compounds from CAP and PAM, this is indicative of reactivation of intercellular HOCl-dependent apoptosis-inducing signaling56. Reactivation of HOCl signaling by tumor cells has been shown to be dependent on substantial inactivation of membrane-associated catalase8,9,12.

An initial treatment with CAP (Fig. 3(b):A) caused similar kinetics of apoptosis induction in tumor cells as PAM (Fig. 3(b):B)). Both treatments were confirmed to be strictly dependent on 1O2 in their initial step, whereas apoptosis induction following initial treatment with CAP or PAM was independent of 1O2.

Dissection of the experimental system

Treatment with CAP or PAM leads to the inactivation of membrane-associated catalase of tumor cells

In analogy to the results obtained for reconstitution experiments56 with defined concentrations of the long-lived species H2O2 and nitrite (which are the essential components of PAM), and in line with established concepts on reactivation of intercellular ROS-dependent apoptosis induction7–9,15,52, CAP- or PAM-mediated inactivation of membrane-associated catalase seemed to be an attractive and conclusive hypothesis to explain the initial steps of action.

Inactivation of membrane-associated catalase can be specifically tested through a challenge with exogenous peroxynitrite (ONOO−)12, as intact membrane-associated catalase decomposes ONOO−, whereas inactivation of membrane-associated catalase allows apoptosis induction by exogenous ONOO−. This requires formation of peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH) and its decomposition into ⋅NO2 and apoptosis-inducing ⋅OH radicals.This process is favoured in close vicinity to the cell membrane, due to the activity of proton pumps. Intracellular catalase has no impact on this process, as it cannot reach extracellular ONOO−. Passage of ONOO− through the membrane would cause lipid peroxidation before the intracellular catalase might interact with ONOO−.

As shown in Fig. 4(a), tumor cells that had not been pretreated were protected towards the applied concentrations of ONOO−. Treatment of tumor cells with CAP, followed by 25 min incubation in the same medium, seemed to cause the same degree of inactivation of membrane-associated catalase as the incubation with the established catalase inhibitor 3-AT, as both treatment regimes caused similar apoptotic responses to the dose-dependent ONOO− challenge.

Treatment of tumor cells with CAP for one minute without the subsequent incubation period was not sufficient for the inactivation of catalase. Washing of the tumor cells immediately after CAP treatment and further incubation in fresh medium resulted in a negligible catalase inactivation. This finding shows that the presence and action of long-lived species from CAP is necessary to achieve catalase inactivation during the 25 min incubation step. The presence of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF during CAP treatment and/or the subsequent incubation for 25 min in the original medium, prevented the inactivation of catalase. This finding demonstrates that, following CAP treatment, the cells must have contributed to the inactivation of their catalase through NOX1-derived O2⋅−. As shown in Fig. 4(b), catalase inactivation by CAP under standard conditions required 1O2, NOX1-derived O2⋅−, H2O2, NOS-derived ⋅NO, ONOO−, ⋅OH radicals and the activity of caspase-8, as seen from the inhibitor profile of apoptosis induction by the ONOO−- challenge. Inactivation of catalase did not require the action of HOCl, as taurine had no inhibitory effect on catalase inactivation through CAP.

Inactivation of membrane-associated catalase by PAM seemed to be mediated by the same molecular players as the catalase inactivation by CAP (Fig. 4(c)). Again, PAM seemed to trigger a strong autoamplificatory secondary singlet oxygen generation by the tumor cells, as seen by the strong inhibitory effect of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF.

Figure 5(a):A confirms that 1 min treatment with CAP followed by 25 min incubation of the cells in the same medium did not cause detectable catalase inactivation when secondary 1O2 generation had been prevented by either inhibiting NOX1 or NOS; by AEBSF or L-NAME, respectively. When, however, CAP treatment had been extended to 3 min, inactivation of catalase despite the presence of AEBSF or L-NAME was demonstrated (Fig. 5(a):B). The degree of inactivation under these conditions was lower than in the absence of AEBSF or L-NAME. Inactivation of catalase in the presence of AEBSF seemed to be due to primary singlet oxygen generated by the long-lived species in plasma-treated medium, as it was prevented through scavenging of 1O2, ONOO−, H2O2 and ⋅OH radicals by histidine, FeTPPS, EUK-134 and mannitol (Fig. 5(a):C).

Further extension of the treatment time with CAP to 10 min (without subsequent incubation step) demonstrated catalase inactivation by CAP-derived 1O2. However, this approach required a prior application of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF in combination with EUK-134 and FeTPPS, which catalytically decompose H2O2 and ONOO−, respectively (Fig. 5(b)). These conditions prevent formation of primary 1O2 generation from long-lived species in PAM and the generation of secondary 1O2 by the cells, and thus allow to focus on the effects induced by singlet oxygen derived directly by CAP.

We note that it is possible that CAP can create 1O2 in the gas phase and that some of these species could enter the top parts of the cell culture medium before being lost. Demonstration of the possible action of singlet oxygen generated in this direct fashion by CAP was only possible in cell cultures that were partially in suspension, like MKN-45 cells, but not for SIHA or SKN-MC cells that were firmly attached to the bottom of the tissue culture plate and covered by medium.

Catalase inactivation allows for subsequent intercellular ROS/RNS signaling

Treatment of MKN 45 tumor cells with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 minutes incubation and a washing step, allowed subsequent apoptosis induction to a similar degree as the direct inhibition of catalase by 3-AT (Fig. 6(a)). Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment was blocked when O2⋅− synthesis was inhibited by AEBSF, when O2⋅− was scavenged by SOD or the SOD mimetics MnTM-2-Pyp or MnTE-2PyP, when H2O2 was decomposed by catalase or the catalase mimetic EUK-134. Strong apoptosis inhibition occurred also when peroxidase was blocked by ABH, when HOCl was scavenged by taurine and when ⋅OH radicals were scavenged by mannitol or DMTU. These findings are in perfect alignment with the inhibitor profile of the HOCl signaling pathway. The ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling pathway did not seem to play a role for apoptosis- inducing signaling under these conditions, as inhibition of NOS by L-NAME, or decomposition of ONOO− by FeTPPS had no inhibitory effect on apoptosis induction. 1O2 and caspase-8 played no role for apoptosis induction, wherease the aquaporin inhibitor Ag+ and caspase-3 caused a strong inhibition of apoptosis.

When the fast decaying ⋅NO donor DEA NONOate was added to CAP-treated cells, apoptosis-inducing signaling was completely shifted to ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling at the expense of HOCl signaling (Fig. 6(b)).

Abrogation of apoptosis-inducing HOCl as well as ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling by exogenous soluble catalase was in line with the proposed dominant controling function of catalase for these processes. Importantly and in line with previous findings9. Inhibition of ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling required higher concentrations of exogenous catalase than inhibition of HOCl signaling.

The relevance of catalase inactivation for apoptosis-inducing RONS signaling

As shown in Fig. 7A, apoptosis induction by HOCl signaling, in the absence of ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling, was confirmed for CAP-treated tumor cells. As HOCl signaling was completely prevented in the presence of 8 U/ml exogenous catalase, the functional role of the targeted membrane-associated catalase of tumor cells for their protection was confirmed. Gradually increasing concentrations of exogenous catalase caused gradually decreased apoptosis induction in the CAP-treated tumor cells (Fig. 7B). Cell death was completely prevented at a concentration of 8 U/ml catalase. Further addition of exogenous catalase seemed to allow reactivation of ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling, in the absence of HOCl signaling, as deduced from the inhibitor profile (Fig. 7B,C). Finally, apoptosis was completely blocked at 1000 U/ml of exogenous catalase. These findings again demonstrate the relevance and central role of catalase inactivation for cell death-inducing ROS/RNS signaling of tumor cells. They also show a differential requirement of catalase concentrations for the inhibition of the two signalling pathways. In addition, they confirm the established negative interference of HOCl signaling towards ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling. Furthermore, adding the ⋅NO donor DEA NONOate, resulting in the formation of large amounts of ONOO−, showed similar negative interference of ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling towards HOCl signaling.

Figure 7.

The relevance of catalase inactivation for apoptosis-inducing ROS/RNS signaling. (A) MKN-45 cells remained without pretreatment (control), received 8 U/ml exogenous catalase or were treated with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min of incubation and three cycles of washing. CAP-pretreated cells then remained either without inhibitors, or received 8 U/ml catalase, 100 µM of the NOX1 inhibitor AEBSF, 150 µM of the peroxidase inhibitor ABH, 50 mM of the HOCl scavenger taurine (TAU) or 25 µM of the peroxynitrite (ONOO−) decomposition catalyst FeTPPS. The determination of apoptotic cells after 3.5 h showed that apoptosis induction required treatment with CAP. The effect of CAP treatment was due to selective establishment of HOCl signaling and was completely inhibited by exogenous catalase. This allows to conclude on the functional role of catalase for the protection of tumor cells towards HOCl signaling. This is in line with catalase being the central target for CAP treatment. (B,C) MKN-45 cells were pretreated with CAP for 1 min, followed by 25 min incubation in the same medium and three cycles of washing steps. The cells remained without inhibitor or received the indicated inhibitors. All assays then received the indicated increasing concentrations of catalase and apoptosis induction was determined after 3.5 h. The result shows that CAP treatment reactivated specifically HOCl signaling, without initial contribution of ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling. With increasing concentrations of catalase, first HOCl signaling was efficiently inhibited before ⋅NO/ONOO− signaling was reactivated. Finally ⋅NO/ONOO−signaling was inhibited by very high concentrations of exogenous catalase. Statistical analysis: A: Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment, as well as inhibition by all inhibitors except FeTPPS was highly significant (p < 0.001). B, C: Apoposis induction after CAP treatment and in the presence of 0–2, as well as 31–250 U/ml catalase was highly significant (p < 0.001). The inhibition by AEBSF and mannitol was highly significant at all catalase concentrations (p < 0.001). Inhibition by taurine and ABH in the low concentration range of catalase (0–2 U/ml), and by L-NAME and FeTPPS in the high concentration range (31–250 U/ml) was highly significant (p < 0.001). The shifting effect of taurine in the concentration range of 16 and 31 U/ml was highly significant (p < 0.001).

SiRNA-based analysis of the molecular players involved in CAP-mediated apoptosis induction

Small interfering RNA (SiRNA)-mediated knockdown of defined proteins has been instrumental for the elucidation of ROS/RNS-mediated signaling and its control4,13. This instrument was therefore utilized for the analysis of CAP-mediated effects on tumor cells. However, in contrast to inhibitors that can be applied differentially, siRNA-mediated knockdown cannot determine per se at which step an enzyme is involved.

Supplementary Figure 3 shows that CAP-mediated, singlet oxygen- and ROS-signaling-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells was dependent on NOX1, but not on NOX-3, -4, -5. Apoptosis induction seemed to require expression of DUOX and iNOS, but not of nNOS. The signaling relevant molecules TGFbeta, its receptor as well as PKC zeta were also found to be essential. As recently shown, these compounds are essential for NOX1 activity4. The FAS receptor and caspase-8 seemed to be required for enhancement of defined signaling processes (as deduced in parallel by inhibitor studies), whereas the requirement for SMASe, Bak, Diablo, VDAC, CYTC, APAF, Caspase-9 and Caspase-3 was indicative for the execution of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis after CAP treatment.

Further information on the signaling relevant function of caspase-8 is presented in Supplementary Fig. 4.

CAP-mediated inactivation of SOD

Singlet oxygen can inactivate SOD as well as catalase62,63. Therefore, an impact of CAP and PAM treatment on the SOD activity on the surface of tumor cells was also expected. Inactivation of membrane-associated SOD leads to an increase in free extracellular superoxide anions that can be verified by an increased reaction with exogenous apoptosis-inducing HOCl. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5A, CAP treatment seemed to cause a marked increase in free superoxide anions as detected by a leftward shift of the concentration-dependency of apoptosis induction by HOCl. This effect was analogous and in the same range of efficiency as the inactivation of SOD by neutralizing single domain antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 5B). Control assays confirmed that single domain antibodies that bound to SOD without neutralizing its activity did not cause an analogous effect.

The role of aquaporins for CAP-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells

Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment was completely prevented in the presence of the aquaporine inhibitor Ag+ (Fig. 8(a)). However, when the intracellular glutathione level had been lowered through preincubation of the tumor cells with buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis, the kinetics of apoptosis induction after CAP treatment showed no lag phase and was faster. Importantly, apoptosis induction under these conditions was no longer blocked by Ag+. These data show that the action of aquaporins is not required when the glutathione level is lowered by biochemical treatment before application of CAP.

Figure 8.

The role of aquaporins and proton pumps for CAP-mediated apoptosis induction. (a) The role of aquaporins for intercellular apoptosis-inducing signaling after CAP treatment. Tumor cells were pretreated in the absence of inhibitors (Control) or in the presence of 10 µM or 50 µM of buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), an inhibitor for glutathione synthesis, for 14 h. The cells were washed and either received no further treatment, addition of 5 µM of the aquaporin inhibitor Ag+, treatment with CAP for 1 min plus 25 min incubation or CAP treatment plus Ag+. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined kinetically. Part A shows that control cells required a 1 hour lag phase before they responded to CAP treatment with apoptosis induction. CAP-mediated apoptosis induction was completely blocked when Ag+ had been added at 0 min of incubation, whereas there was no inhibitory effect when Ag+ had been added 1 hour after the beginning of the incubation. Part B shows that pretreatment of the cells with BSO, i. e. inhibition and consumption of GSH, allowed for a faster onset of CAP-mediated apoptosis induction that was no longer inhibited by Ag+. Statistical analysis: A: Apoptosis induction after CAP treatment at 2 h and later, as well as inhibition by Ag+ added before CAP treatment was highly significant (p < 0.001), whereas addition of Ag+ 1 h after CAP treatment was without significant inhibitory effect. B: Apoptosis induction after pretreatment with BSO, followed by CAP treatment was highly significant (p < 0.001), whereas Ag+ did not cause significant inhibition. (b) The role of proton pumps for CAP-mediated apoptosis induction. Upper graph: The proton pump inhibitor omeprazol was added at increasing concentrations to MKN-45 cells either at the beginning of CAP treatment for 1 min or 25 min after CAP treatment. Apoptosis induction was determined after 3.5 h. The result shows that later effects of CAP treatment are less sensitive to the proton pump inhibitor than earlier ones. Lower graph. Model experiments with omeprazol using defined signaling pathways for apoptosis induction. Increasing concentrations of omeprazol were added to MKN-45 cells that were either treated with the indicated concentrations of the catalase inhibitor 3-AT plus peroxynitrite (ONOO−) or HOCl. The percentages of apoptotic cells were determined after 2 h. The result shows that ONOO−-mediated apoptosis induction was more efficiently inhibited by omeprazol than HOCl-dependent apoptosis induction. Statistical analysis: Upper graph: When omeprazol had been added at 0 min, the inhibitor caused highly significant inhibition at 0.4 µM and higher concentrations, whereas it caused highly significant inhibition at 3.5 µM and higher when added at 25 min (p < 0.001). Lower graph: Inhibition of ONOO−-mediated apoptosis induction was highly significant (p < 0.001) at 0.4 µM omeprazol and higher, whereas highly significant inhibition of HOCl-mediated apoptosis induction required concentrations of 14 µM or higher.

The role of proton pumps for CAP mediated apoptosis induction

The formation of peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH), with its high potential to spontaneously dissociate into ⋅NO2 and ⋅OH radicals, is essential for the generation of secondary 1O215,77. The formation of ONOOH acid is favoured at the membrane of tumor cells through proton pumps, whereas ONOO− distant from cell membranes has a higher chance to react with CO2 and be unavailable for activity near the cell membrane78–80. As shown in Fig. 8(b), inhibition of proton pumps by omeprazol had a very strong inhibitory effect on the early steps of CAP-mediated apoptosis induction, whereas omeprazol inhibited the following steps to a much lesser degree. Recall that acidification from proton pumps in buffered cell medium is necessary for CAP-generated H2O2 and nitrite to form primary 1O2. This pattern is in good agreement with the differential inhibition of ONOO−- and HOCl-dependent apoptosis induction by the proton pump inhibitor.

Differential effects of CAP and PAM on nonmalignant cells and tumor cells: clues to establishment of selective antitumor effects

In addition to apoptosis induction in MKN-45 human gastric carcinoma cells, CAP treatment of 1 min was also sufficient to substantially induce apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells (SHEP), Ewing sarcoma cells (SKN-MC) and cervix carcinoma cells (SIHA) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Apoptosis induction in these cells seemed to depend on NOX1-derived O2⋅−, as it was inhibited by AEBSF. It was also dependent on 1O2, as seen by the efficient inhibition by the 1O2 scavenger histidine. The strong inhibitory effect of histidine that had been added one minute after CAP treatment indicated an action of 1O2 that was not generated in the gas phase but generated by CAP-generated nitrite and H2O2 in medium. The singlet oxygen-dependent step seemed to be completed 30–60 min after CAP treatment.

Apoptosis induction in nonmalignant diploid human fibroblasts by CAP required longer than 1 min treatment and its effects increased with exposure time (Fig. 9(a):A). Apoptosis induction in nonmalignant cells by high doses of CAP seemed to be mediated primarily by H2O2, independent of singlet oxygen and NOX-derived superoxide anions (Fig. 9(a):B). This is contrasted by the strict dependence of CAP-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells on singlet oxygen, NOX-derived superoxide anions and H2O2 (Fig. 9(a):C). As noted previously, H2O2 is involved in CAP-mediated apoptosis induction in tumor cells through its role during the formation singlet oxygen, intracellular glutathione depletion and substrate for peroxidase to generate HOCl.

Figure 9.