Abstract

The vascular dysfunction is the primary event in the occurrence of cardio-vascular risk, and no treatment exists until now. We tested for the first time the hypothesis that chitin-glucan (CG) - an insoluble fibre with prebiotic properties- and polyphenol-rich pomegranate peel extract (PPE) can improve endothelial and inflammatory disorders in a mouse model of cardiovascular disease (CVD), namely by modulating the gut microbiota. Male Apolipoprotein E knock-out (ApoE−/−) mice fed a high fat (HF) diet developed a significant endothelial dysfunction attested by atherosclerotic plaques and increasing abundance of caveolin-1 in aorta. The supplementation with CG + PPE in the HF diet reduced inflammatory markers both in the liver and in the visceral adipose tissue together with a reduction of hepatic triglycerides. In addition, it increased the activating form of endothelial NO-synthase in mesenteric arteries and the heme-nitrosylated haemoglobin (Hb-NO) blood levels as compared with HF fed ApoE−/− mice, suggesting a higher capacity of mesenteric arteries to produce nitric oxide (NO). This study allows to pinpoint gut bacteria, namely Lactobacillus and Alistipes, that could be implicated in the management of endothelial and inflammatory dysfunctions associated with CVD, and to unravel the role of nutrition in the modulation of those bacteria.

Subject terms: Physiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Despite the enormous progress made in the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) over the last twenty years, CVDs remain the leading cause of disability and death in Western countries1. Given the growing prevalence of obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, it is estimated that the number of people with chronic cardiometabolic disease will continue to grow in the next two decades1,2. Obese individuals that develop atherosclerotic CVDs are often characterized by a low-grade chronic inflammation. It has been hypothesized that changes in inflammatory status partly explain the individual differences in cardiovascular risk2. Endothelial dysfunction is an early key marker of CVDs reflecting the integrated effects of risk factors on the vascular system3. It comes from the incapacity of endothelial cells to equilibrate synthesis and release of damaging or protective mediators, among which nitric oxide (NO) is the most important. The main feature of endothelial dysfunction is the inability of endothelium to promote vasodilation in response to agonist or shear forces4.

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a key mediator for transport and reuptake of cholesterol. ApoE knock-out mice (ApoE−/−) are proposed as a model of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction5. Endothelium-dependent relaxation is reduced in response to acetylcholine in 13-months-old ApoE−/− mice compared to wild-type mice6. However, this is not observed in youngest mice, suggesting that vascular disorders occurring in ApoE deficiency depend on age. Obesity are associated to altered vascular functions, with impaired vessel reactivity and lower endothelium-dependent relaxation. Interestingly, high fat (HF) diet feeding accelerates the process of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice7. In addition, HF diets participate to worsening metabolic and vascular phenotypes which negatively influences the evolution of CVD in this murine model8,9.

The pathophysiology of CVDs is complex and involves multiple organs, establishing distant communications via bloodstream. Recently, a growing body of evidence has emerged regarding the critical role of gut microbiota in CVDs and metabolic disorders1,10. The gut microbiota can be considered as a “microbial organ” under the influence of the diet and host factors. Hence, the gut microbiota and its activity are intricately intertwined with the physiology and pathophysiology of the host11–13. Obesity in humans has been associated with the composition and function of the gut microbiota, but only a few studies focus on the role of gut microbiota in the CVDs1.

Modulation of the diet with specific dietary components could be used to prevent atherosclerosis. Dietary fibre is thought to have beneficial effects on health because it is considered to reduce the risk of CVD. In humans, this effect could be attributed to a decrease in plasma LDL10,14. For years, we and others have demonstrated that dietary fibre supplementation modulates the composition of the gut microbiota, and eventually improves host physiology13,15,16. This is particularly the case for inulin-type fructans (ITF), which are classified as prebiotics. Prebiotics are ‘substrates that are selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit’17. Whether CVD and atherosclerosis can be successfully treated by fibre targeting the microbiota is still not clear. ITF-fed ApoE −/− mice have been shown to have reduced cholesterol and atherosclerotic lesions compared to control mice. However, the mechanism was unexplored18. Recently, we demonstrated that ITF improve endothelial dysfunction in ApoE−/− mice fed a n-3 PUFA-depleted diet and developing steatosis. We found that ITF-induced changes in gut microbiota linked endogenous GLP-1 production with an improved endothelial function19. If proven in humans, those studies suggest that prebiotics might be proposed as a novel approach in the prevention of metabolic disorders-related CVDs.

Chitin-glucan (CG) has been shown to modulate the human gut microbiota in the in vitro SHIME microbiota simulator20. In a previous study, we have highlighted beneficial effects of this insoluble fibre on the development of obesity and associated diabetes and hepatic steatosis in mice, through a mechanism related to the restoration of the composition and/or the activity of gut bacteria21.

In the present study, we have tested the prebiotic potency of chitin-glucan, an insoluble dietary fibre, alone or in combination with a pomegranate peel extract (PPE) rich in polyphenols in a model of accelerated atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice fed a high fat diet during 8 weeks.

Results

Chitin-glucan supplementation with or without pomegranate peel extract did not change high fat diet-induced body weight gain, fat mass expansion and hypercholesterolemia

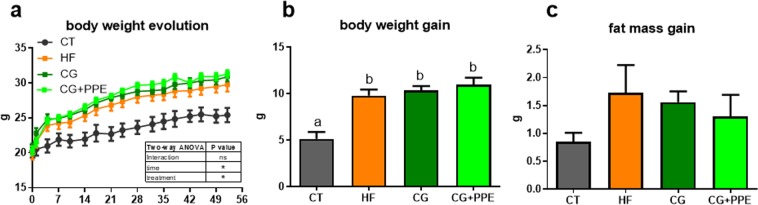

The HF diet significantly increased body weight gain and the development of epididymal, visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues of ApoE−/− mice as compared with control diet (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The fat mass increased upon HF feeding without reaching significance (Fig. 1). Liver weight and cholesterolemia were higher in HF-fed than in CT mice (Table 1). CG or CG + PPE supplementation did not significantly change those parameters. The lipid profile in the plasma was not affected by the dietary treatments (Table 1). Although this effect was not statistically significant due to large variability, CG with or without PPE decreased the level of ALAT in the serum (ALAT activity expressed in U/L: 16.4 ± 6.6, 16.6 ± 5.2, 6.7 ± 1.2, 8.8 ± 1.9 for CT, HF, CG and CG + PPE groups, respectively).

Figure 1.

Body weight evolution (a), body weight gain (b) and fat mass gain (c) of ApoE−/− mice fed a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data with different superscript letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA); ns = non significant and *p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA).

Table 1.

Organ weights and plasma lipids.

| CT | HF | CG | CG + PPE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver (g) | 0.96 ± 0.08a | 1.21 ± 0.07b | 1.25 ± 0.06b | 1.24 ± 0.03b |

| Visceral adipose tissue (%) | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.65 ± 0.07 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.07 |

| Subcutaneous adipose tissue (%) | 0.80 ± 0.06a | 1.45 ± 0.20b | 1.19 ± 0.11ab | 1.14 ± 0.14ab |

| Epididymal adipose tissue (%) | 0.96 ± 0.08a | 1.88 ± 0.27b | 1.54 ± 0.17b | 1.51 ± 0.17ab |

| Cecal tissue (mg) | 56 ± 5a | 41 ± 2b | 51 ± 2ab | 56 ± 2a |

| Cecal content (mg) | 239 ± 27 | 171 ± 15 | 221 ± 11 | 213 ± 17 |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 0.71 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.17 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.60 ± 0.07 |

| Non esterified fatty acids (mM) | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.06 |

| Total cholesterol (mM) | 9.78 ± 1.55a | 16.68 ± 2.24b | 14.92 ± 0.76b | 15.90 ± 0.73b |

ApoE−/− mice were fed a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data with different superscript letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 (ANOVA).

It is interesting to note that ApoE−/− mice upon HF feeding and treated with CG or CG + PPE exhibited the higher cecal tissue and cecal content weight compared to HF group; this effect reached statistical significance for the cecal tissue from the mice treated with the combination (Table 1).

Chitin-glucan supplementation with pomegranate peel extract decreased hepatic content of triglycerides

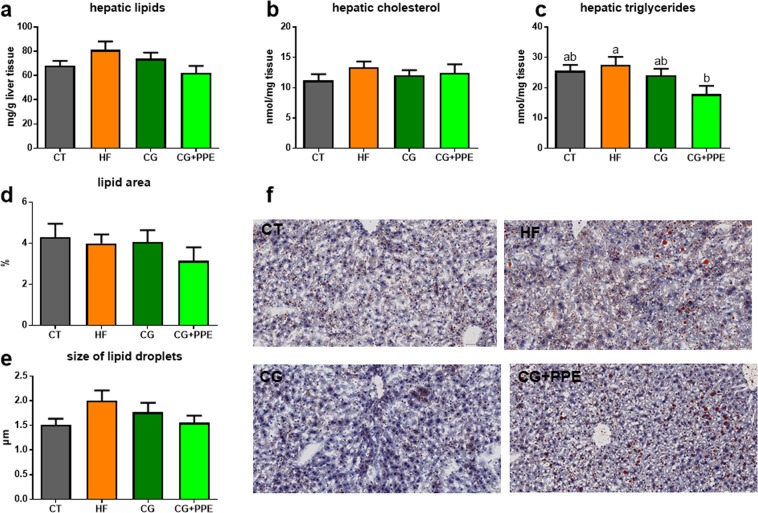

The HF diet did not significantly affect lipid content, cholesterol content and triglyceride content of the liver tissue from the ApoE−/− mice compared to CT group as shown in Fig. 2(a–c). The supplementation with the CG in combination with PPE significantly reduced hepatic triglycerides (Fig. 2c). Fat staining of the tissue confirmed the lower fat accumulation in the liver even if the significance was not reached (Fig. 2d–f).

Figure 2.

Lipid accumulation in the liver tissue. Hepatic content of lipids (a), cholesterol (b) and triglycerides (c) of ApoE−/− mice fed a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Lipid fraction area (d) and mean size of lipid droplets (e) were automatically analysed by ImageJ from Oil red O staining of frozen section of the main lobe of liver, bar = 100 µm (f). Data with different superscript letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 (ANOVA).

In addition, we measured the expression of two hepatic genes regulating lipid metabolism: fatty acid synthase (Fas), a key enzyme involved in lipogenesis and carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (Cpt1), a marker of fatty acid oxidation. None of the dietary treatments significantly affect Fas or Cpt1 expression (data not shown).

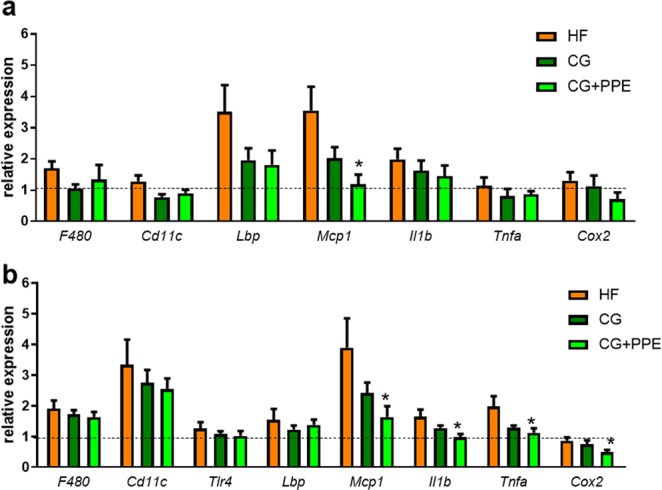

Chitin-glucan supplementation with pomegranate peel extract reduced inflammatory markers both in adipose tissue and in the liver

HF diet has been reported to induce endotoxemia and inflammation in the liver and the visceral adipose tissue22. In addition, our previous findings support that pomegranate extract alleviated tissue inflammation in HF diet-induced obese mice23. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of the target genes among others, in particular: two macrophage markers (CD11c, F4/80), the lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP), a key pattern recognition receptor (Toll-like Receptor-4 (TLR4)), one of the most potent chemokines identified for monocytes recruitment (monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP1)), two important proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (Il1β)) and the gene coding for cyclooxygenase (COX-2) that produces prostaglandin E2, a regulator of inflammation, both in the liver and the visceral adipose tissues24. Several markers of macrophage infiltration and/or inflammation were induced in the visceral adipose tissue (p < 0.05 ANOVA for Mcp1) and in the liver (p < 0.05 ANOVA for Mcp1, Cd11c, Il1b, Tnfa, F480) of ApoE−/− mice due to HF feeding as compared to CT group (Fig. 3). Among them, MCP1 was downregulated after CG supplementation; this effect was more pronounced and significant in combination with the PPE. In addition, the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα, Ilβ and COX-2 were downregulated in the liver from mice treated with the combined supplementation (Fig. 3b). However, several circulating cytokines and biomarkers of inflammatory related to cell adhesion molecules (IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, MIP1α, MCP1, TNFα, sE-Selectin, sICAM-1, PAI-1, proMMP-9) were not significantly influenced by the treatments (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Expression of inflammatory markers in the visceral adipose tissue (a) and the liver (b). ApoE−/− mice were fed a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The dotted line depicts the relative values observed in ApoE−/− mice fed a low fat diet (set at 1). *p < 0.05 versus HF group (ANOVA).

Chitin-glucan supplementation with pomegranate peel extract improved endothelial (dys)function

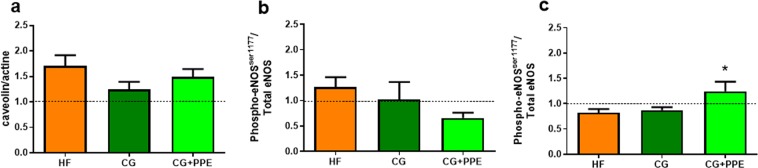

Endothelial dysfunction was attested by atherosclerotic plaques in aorta isolated from ApoE−/− mice fed a HF diet (data not shown). In line with a potential reduced endothelial function25, aorta showed increased abundance of caveolin-1 (*p < 0.05 HF group versus CT group, ANOVA), the negative allosteric regulator of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) (Fig. 4a). We performed western blotting to assess the activating serine 1177 phosphorylated form of endothelial NOS (p-eNOSser1177) in conductance (thoracic) versus resistance (mesenteric) arteries (Fig. 4b,c). Interestingly, the combination CG + PPE increased the activating form of eNOS in mesenteric arteries (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Western blot analyses on aorta (a,b) and mesenteric arteries (c) with anti-caveolin-1 (a) or anti-phosphorylated endothelial NOS (eNOS)ser1177 (b,c). ApoE−/− mice were fed a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Values are expressed relative to ApoE−/− mice fed a low fat diet (set at 1). *p < 0.05 versus HF group (ANOVA).

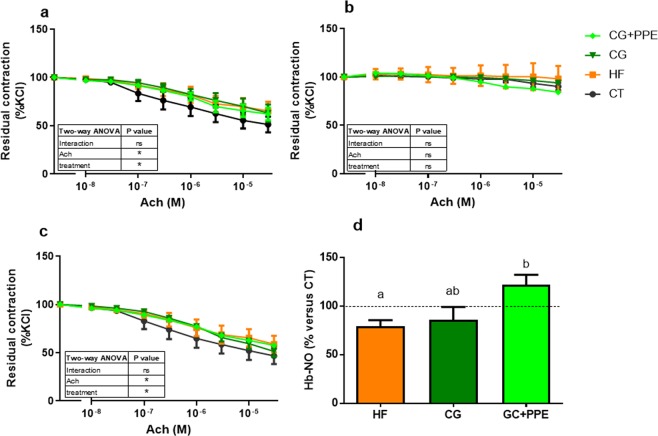

Mesenteric arteries segments were mounted in wire myograph in order to evaluate endothelial function. Resting parameters revealed no difference (after normalization) between the four groups concerning the basal tone, the maximal contraction after a KCl challenge and the mean arterial diameter (supplemental File 1). The endothelium-dependent relaxation was studied upon acetylcholine addition in the incubation medium on pre-constricted arteries in the presence of a KCl-enriched solution and in the presence of a cyclooxygenase inhibitor (indomethacin) or a NO synthase inhibitor (L-NAME). Mesenteric arteries isolated from HF treated ApoE−/− mice relaxed less in response to acetylcholine than vessels obtained from ApoE−/− mice fed a control diet, suggesting the presence of endothelial dysfunction in HF fed mice whatever the supplementation (Fig. 5a). In contrast to incubation in the presence of indomethacin, this effect disappeared in the presence of NO synthase inhibitor (Fig. 5b), suggesting that HF diet worsened the NO-dependent endothelial dysfunction of ApoE−/− in mesenteric arteries. However, dietary supplementations did not significantly modify endothelium-dependent relaxation of mesenteric arteries (Fig. 5a–c). Importantly, to confirm an impact of CG + PPE on NOS/NO pathway, we measured the level of circulating heme-nitrosylated hemoglobin (Hb-NO) in the mice venous blood by EPR (Fig. 5d). HF mice presented a decreased level of Hb-NO compared to CT mice. In line with result obtained with phosphorylated form of eNOS protein, CG + PPE mice displayed a 40% increase in Hb-NO levels as compared with HF mice.

Figure 5.

Endothelium-dependent relaxation of preconstricted mesenteric arteries and level of Hb-NO in venous blood. Endothelium-dependent relaxation was evaluated by cumulative addition of acetylcholine (Ach) on pre-contracted arteries with a high KCl-solution, in the absence (a) or the presence of nitric oxide synthase inhibitor Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (b) or a cyclooxygenase inhibitor (c). Level of Hb-NO in venous blood (d). ApoE−/− mice were fed a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data with different superscript letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA); ns = non significant and *p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA).

Chitin-glucan supplementation with pomegranate peel extract affected the gut microbiota composition in ApoE−/− mice fed a high fat diet

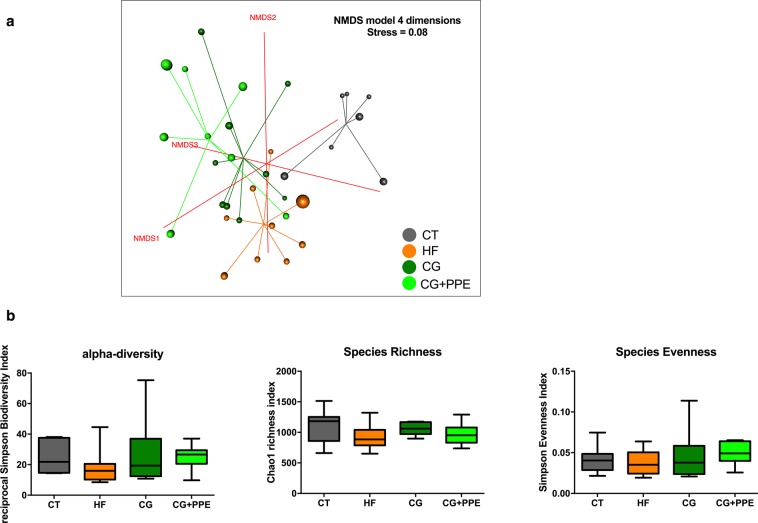

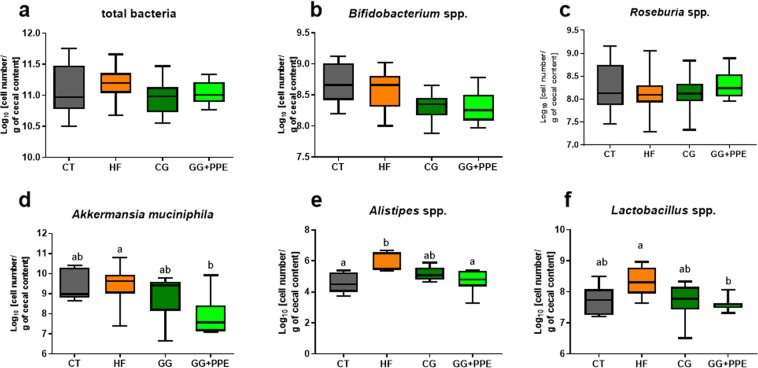

The differences within the intestinal microbial population between the four groups were visualized by Non Metric Dimensional Scaling built upon a Bray-curtis distance matrix based on the species taxonomic level (Fig. 6a). A distinct clustering was observed for each of the four groups of mice and was confirmed by AMOVA analysis of the dissimilarity matrix, albeit not for the CG + PPE versus CG groups (Supplementary File 1). We did not observe any significant effect on cecal microbial α-diversity (Fig. 6b). Despite the presence of different clustering, the relative abundances between phyla or family or genus due to CG and PPE supplementation were not significantly affected at the q-value by the dietary treatment (Supplementary Dataset 1). However, it is important to mention that the abundances of Akkermansia and Alistipes among other bacterial genera were significantly different between the dietary treatments at the p-value. In addition to the sequencing of the cecal microbiota, we analyzed some specific bacteria with a complementary quantitative approach by using qPCR method on an educated guess basis, meaning that we selected bacteria for which previous reports have shown a link between these bacteria and inflammation/metabolic disorders: (1) several studies demonstrated that specific Bifidobacterium or Lactobacillus strains alone or in combination, decreased the metabolic alterations (decrease of body weight and fat mass gain) together with a reduction of the inflammatory events, occurring in the liver and/or the adipose tissue in diet-induced obesity models26,27; (2) a recent paper demonstrated that Roseburia interacted with dietary plant polysaccharides to lower systemic inflammation and ameliorated atherosclerosis in germ-free apolipoprotein E-deficient mice colonized with synthetic microbial communities28. Moreover, our previous work showed that CG had metabolic interest that could be related to the increase in Roseburia spp. in a mouse model of HF induced-obesity21; (3) Alistipes were positively associated with HF-induced obesity in several independent studies29–31; (4) finally, Akkermansia is a bacterium capable of reducing adipose tissue inflammation and dyslipidaemia in obese mice26,27,32,33. The Fig. 7 shows that the increase of Alistipes spp. and Lactobacillus spp in the cecal content due to HF feeding was counteracted by the CG + PPE supplementation (Fig. 7e,f). Akkermansia muciniphila were also significantly decreased by the combination CG + PPE compared to the HF fed group (Fig. 7d). We did not observe any changes in total bacteria, Roseburia spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. (Fig. 7a–c).

Figure 6.

Microbiota structure assessed by non-metric dimensional scaling (NMDS) and bacterial diversity. A four dimensional model, built on a species level dissimilarity matrix has been obtained with a stress value of 0.08 (a). Reciprocal Simpson alpha-diversity, Chao richness and Simpson evenness (b) assessed from amplicon sequencing data of microbial cecal content of ApoE−/−mice fed, a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks (p > 0.05 ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Figure 7.

Cecal bacteria assessed by qPCR. Total bacteria (a), Bifidobacterium spp. (b), Akkermansia muciniphila (c), Roseburia spp. (d), Alistipes spp. (e), Lactobacillus spp. (f) in the cecal content of ApoE−/−mice fed, a low fat diet (CT), a high fat (HF) diet or a HF diet supplemented with 5% chitin-glucan (CG) or a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% pomegranate peel extracts (CG + PPE) for 8 weeks. Data are Whiskers plots with minimum and maximum. Data with different superscript letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 (ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis test).

Discussion

The nutritional quality of diets underlies or exacerbates several chronic pathologies, including CVD34,35. Western diets are high in calories, simple sugars, saturated fat and are also characterized by an imbalance in the dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 PUFA36. In a recent study, we demonstrated that n-3 PUFA depletion for 12 weeks could accelerate the process of endothelium dysfunction in young ApoE−/− mice prone to develop atherosclerosis19. Another study demonstrated that consumption of HF diet (60% kJ from fat) during 17 weeks promotes obesity and accelerates atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice7. This effect was accompanied by the development of a metabolic syndrome phenotype characterized by a low level of inflammation and atherosclerotic lesion7. In the present study, we show that HF feeding (60% kcal from fat and 0.15% cholesterol) induces obesity, hypercholesterolemia, inflammatory disorders and endothelial dysfunction in young (10-wk-old at the beginning of the treatment) ApoE−/− mice fed a HF diet for only 8 weeks. We then used this model to test the health benefits of original nutrients in the management of endothelial and inflammatory dysfunctions associated with CVD.

The health-promoting effect of prebiotic fibre and plant extracts is subject to interesting developments37. Chitin-glucan (CG), a natural component of the cell wall of microscopic fungi has been approved as a novel food ingredient after a positive safety evaluation in 2010 by the European Food Safety Authority38. The CG used in the present study is a high-purity biopolymer extracted from the mycelium of Aspergillus niger. This insoluble fiber is composed of two types of polysaccharide chains, namely chitin (poly-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) and beta-(1,3)-D-glucan (D-glucose units linked predominantly via beta-(1,3) linkage). We previously demonstrated its beneficial effects on the development of obesity and associated diabetes and hepatic steatosis in HF-fed mice, through a mechanism related to the restoration of the composition and/or the activity of gut bacteria [33]. On the other side, health benefits of pomegranate fruit and/or juice consumption have recently received considerable scientific focus. The PPE used in this study is a source of polyphenol (40%), with punicalagin and ellagic acid levels reaching 10% and 2%, respectively. Our previous findings support that pomegranate extract constitutes a promising food ingredient to control atherogenic and inflammatory disorders associated with diet-induced obesity since it alleviated tissue inflammation and hypercholesterolaemia in HF diet-induced obese mice23. In line with our previous results, here we observe that CG + PPE reduces several proinflammatory parameters such as the expression of the chemokine MCP-1 (involved in the recruitment of inflammatory cells inside the tissue) in both the visceral and liver tissues and the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα in the liver.

The presence of hepatic steatosis has previously been reported for ApoE−/− mice fed a HF diet and the model has been proposed to study features of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) on cardiovascular events38,39. In the present study, HF feeding did not induce higher lipid accumulation in the liver of ApoE−/− mice than the low fat diet. This is probably due to the short-term dietary treatment investigated here. Importantly, the supplementation with CG + PPE reduced significantly hepatic triglycerides, one of the critical features of NAFLD. Further studies are needed to unravel the mechanism behind the lower hepatic fat accumulation since two key genes in the liver that regulate lipid metabolism (FAS and CPT-1) were not affected by the dietary treatments.

Metabolic diseases such as NAFLD are associated with macro- and microcirculation damage, initiating an impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation39,40. Eight weeks of HF-diet were able to accelerate the process of endothelial dysfunction in aorta namely by increasing abundance of caveolin-1, a negative allosteric regulator of eNOS leading to endothelial dysfunction exacerbation and associated CVD25,41. However, the dietary combination did not affect this parameter in the aorta, the major representative conductance vessel of the macrocirculation. We used western blotting to assess the activation of eNOS through analysis of its phosphorylated forms (p-eNOSser1177) both in conductance (thoracic) and resistance (mesenteric) arteries. We observed that the activated form of eNOS was a third higher in mesenteric arteries due to supplementation with CG + PPE compared to HF ApoE−/− mice, suggesting that the innovative dietary combination activated the NOS/NO pathway in the resistance arteries representing the microcirculation near the gut. Furthermore, we investigated the relaxation profile of mesenteric arteries. We demonstrated that HF feeding for 8 weeks accelerated the process of endothelial dysfunction in resistance mesenteric arteries in ApoE−/− genotype, as already shown in previous studies42,43. We concluded that prostanoids do not play an major role in this early stage of endothelial dysfunction, based on the lack of effect of indomethacin, a non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor. In most cases, endothelial dysfunction is related to a reduced NO availability in mice6. Accordingly, impairment of endothelial function due to HF feeding is mainly dependent on a reduced NO bioavailability in ApoE−/− mice as L-NAME (a NOS inhibitor), counteracted the vasorelaxation of mesenteric arteries from all mice and repealed the differences between genotypes, independently of the dietary conditions. In contrast, resting parameters (vessel diameter and basal tone) and contraction profile (response to KCl challenge stimulation) of mesenteric arteries were not affected by the HF treatment whatever the dietary supplementations. In our experimental setting, CG + PPE supplementation did not improve the NO-dependent endothelium relaxation measured in mesenteric arteries. Of more relevance for human CVD, the effects of CG + PPE supplementation were not restricted to the phosphorylated form of eNOS in enteric vascular tree since this dietary treatment also increased the circulating levels of Hb-NO in peripheral blood at distance from the mesenteric bed. Altogether, our results demonstrate that, besides interesting hepatic events highlighted above, the supplementation with CG and PPE for 8 wk improved the endothelial function with consequences on systemic NO bioavailability in HF-fed ApoE−/− mice. It was previously shown that pomegranate extract administrated alone during 30 days enhanced endothelium-dependent artery relaxation although it concerned coronary arteries isolated from perfused hearts of spontaneously hypertensive ovariectomized rats44. Furthermore, they demonstrated in the same study that the treatment with their extract inhibited p-eNOS Thr495 without affecting p-eNOS Ser1177, improved lipid profile and was able to prevent the reduction in plasma nitrite levels spontaneously induced by castration.

Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the control of host intestinal functions and management of NAFLD, through the release and/or biotransformation of metabolites (eg, bile acids and short chain fatty acids) which regulate gut endocrine function12. Establishing the causal and consequential actions of the gut microbiota in driving obesity and related-metabolic diseases has been challenging. Interestingly, Stepankova et al.45 reported that germ-free ApoE−/− mice developed more aortic atherosclerotic plaques compared with conventionally raised ApoE−/− mice fed the same low standard cholesterol diet. Along the same lines, compared to germ-free mice, the levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in plasma of conventionally raised mice are reduced, whereas they are increased in adipose tissue and liver46. Both findings support the hypothesis of a protective ability for the gut microbiota in CVD and in the management of plasma levels of cholesterol and lipids10. We have previously shown that the improvement of vascular dysfunction by ITF was linked to an activation of the NOS/NO pathway, which could be dependent on events occurring at the gut microbiota level (namely, through an increase in NO-producing bacteria). Although dietary treatment induced clusterization due to CG and CG + PPE supplementation, our targeted microbiota characterization did not reveal any changes in bacterial diversity or relative abundance of bacteria whatever the taxonomical level considered. However, the CG and PPE counteracted the effect of the HF feeding on the abundance of Alistipes spp and Lactobacillus spp present in the cecal content of mice only when these compounds were combined. Recently, Moschen and colleagues identified Alistipes spp. as one of the top ten most abundant genera associated with human colorectal carcinoma and provide experimental evidence that Alistipes potently induces inflammation in colitis-prone Il10−/− mice47. In line with this finding, Alistipes were positively associated with HF-induced obesity in several independent studies29–31. The depletion of Alistipes by CG + PPE in the current study is particularly relevant, considering that in both studies, they demonstrated that transmissible microbial and metabolomic remodeling by dietary fiber improved metabolic homeostasis29,30. Our results indicated that Lactobacillus spp. and Akkermansia muciniphila are other bacteria susceptible to dietary manipulation. It has been reported that members of the Lactobacillus, Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium genera may play a critical role as anti-obesity drivers in experimental models and humans32,48,49. One study linked specific species of Lactobacillus (L. reuteri) with obesity in humans50 whereas many studies tested for their ability to affect positively obesity and risk factors associated with CVD26,51. Here, the Lactobacillus genus increased upon HF feeding whereas the supplementation with CG + PPE blunted this effect. The study of Fak and Backhed demonstrated that bacterial strains of the same Lactobacillus species showed different effects on adiposity and insulin sensitivity in ApoE−/− mice, illustrating the complexity of host bacterial cross-talk and the importance of strain specificity52. In this context, it would be of interest to further characterize the identity and the functionality of the Lactobacillus strains affected by the dietary treatments. Although Akkermansia muciniphila is a bacterium capable of reducing fat mass development, insulin resistance, metabolic endotoxemia, adipose tissue inflammation and dyslipidaemia in obese mice and in a pilot study conducted in humans32,33, we observed a decreased abundance of this bacteria in the cecal content of ApoE−/− mice treated with the combination CG + PPE. Our previous work showed that CG had metabolic interest that could be dependent on the increase in Roseburia spp. in a mouse model of HF induced-obesity21 but their level was not impacted the dietary treatments in the model of HF-fed ApoE−/− mice. Therefore, we proposed that neither Akkermansia nor Roseburia spp. were involved in the metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects of the combined treatment (CG + PPE) observed in the present study. These data also clearly support the notion that we should not generalize the effects of dietary fibers and polyphenols on Akkermansia, as discussed in a recent review, predicting which fibers or polyphenols are the most suited to maximize beneficial health effects is highly dependent on the health situation, the individual and its microbiota53

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that food supplementation with CG and PPE limited triglyceride accumulation in the liver and exerted anti-inflammatory effects both in the liver and in the visceral adipose tissue of ApoE−/− mice fed a HF diet. In addition, the combination improved endothelial function in mesenteric arteries through a higher production and availability of NO in this model. Gut bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Alistipes could be implicated in the management of metabolic and inflammatory dysfunctions associated with CVD. The beneficial effects were observed only when CG was associated with PPE in the diet, confirming a previous study that highlighted the need to consider the interactions among bioactive food components when evaluating potential prebiotic effects of dietary fiber54.

Methods

Ethics statement

All experiments were performed in strict accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for the care and use of animals and in accordance with the EU directive. All mouse experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the local ethics committee for animal care of the Health Sector of the Université catholique de Louvain under the specific agreement numbers 2017/UCL/MD/005. Housing conditions were as specified by the Belgian Law of 29 May 2013, on the protection of laboratory animals (Agreement LA 1230314). Every effort was made to minimize animal pain, suffering, and distress and to reduce the number of animals used.

Animals and experimental design

Nine weeks old male and ApoE−/− mice (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J from Charles River Laboratories, L’Arbresle, France) were housed two or three mice per cage (environmental enrichment: plastic tunnels and sheets) and with a 12 h light/dark cycle at 22 °C, diet and water were ad libitum. Mice were fed a low fat (10 kJ%), no sucrose, purified ingredient diet (CT, E157452-047, Ssniff, Germany) or a high fat (HF) diet (60 kJ% fat, 0.15% cholesterol, S8899-E730, Ssniff, Germany) for 8 weeks. HF-fed mice were supplemented with or without 5% CG (Kitozyme, Belgium) and a combination of 5% CG and 0.5% PPE (Oxylent, Belgium). CG used in the study was derived from the cell walls of the mycelium of Aspergillus niger, in which two types of polysaccharide chains, i.e., chitin (poly N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) and β(1,3)-D-glucan, are associated. PPE extract (OXYLENT®GR, Oxylent S.A.) used in the study was derived from pomegranate peel in which polyphenol content reached 40% (Folin–Ciocalteu method, equivalent gallic acid) and the concentrations of punicalagin and ellagic acid were 10 and 2% (ultra-performance liquid chromatography method with diode array detection), respectively.

The data provided in the manuscript are issued from 2 separate experiments, performed in the same animal facility, one for measurement of vascular contraction and relaxation and western blot analysis of mesenteric arteries (experiment A, n = 8 per group) and one for other parameters (experiment B, n = 9 per group). Body composition was assessed every two weeks by using 7.5 MHz time domain-NMR (LF50 minispec, Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany).

Experiment A

After a total of 8 weeks of dietary treatment, mice were anaesthetized in postprandial state (Anesketin®, Ketamin hydrochloride and Rompun®, xylazine hydrochloride i.p., 100 and 10 mg/kg of body weight, respectively). Second and third order mesenteric arteries were rapidly removed and carefully isolated from visceral adipose and/or connective tissues as previously described55.

Experiment B

After a total of 8 weeks of dietary treatment and a 6-h period of fasting, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Forene®, Abbott, Queenborough, Kent, England) and blood samples were harvested. We collected venous blood (0.2 mL) from the right ventricle, immediately frozen in heparinized calibrated tube in liquid nitrogen. Venous blood samples were also collected and centrifuged (3 min at 13,000 g) for further analysis. Liver, aorta, adipose tissues and caecum were carefully dissected, weighted and immersed in liquid nitrogen before storage at −80 °C; pieces of liver and aorta were embedded in OCT compound and frozen in nitrogen cooled isopentane for histology.

Measurement of nitric oxide bioavailability by electron paramagnetic resonance

The level of circulating heme-nitrosylated haemoglobin (Hb-NO) was assayed in whole blood of mice from the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal of 5-coordinate-α-Hb-NO as previously described55.

Blood biochemical analyses

Plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol and non-esterified fatty acid levels were analyzed in venous blood using kits (Diasys Diagnostic and Systems, Holzheim, Germany; Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, United Kingdom). Alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) levels were measured in the serum as a marker of liver damage using the ALAT/GPT kit (DiaSys Diagnostic and Systems). Plasma concentrations of cardiovascular analytes (sE-Selectin, sICAM-1, PAI-1 Total, proMMP-9) and of cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, MIP1α, MCP1 and TNFα) were determined using two multiplex immunoassay kits (Milliplex kits from Merck Millipore based on Luminex® technology (Bioplex®, Bio-Rad, Belgium)). Triglycerides and cholesterol were measured in the liver tissue after extraction with chloroform–methanol according to the Folch method, as previously described56.

Histological analysis

Sections of aortic arch, previously isolated from connective tissues, were frozen in embedding medium (Tissue-tek, Sakura, The Netherlands). Sections of artic arch of 5 µm were cut at 3 different levels for each sample. Haematoxylin-eosin stained sections were digitalized at a 20x magnification using a SCN400 slide scanner (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Frozen sections of the main liver lobe (embedding in Tissue-tek) were sliced and stained with the Oil Red O. Haematoxylin-eosin stained sections were digitalized at a 20x magnification using a SCN400 slide scanner (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The quantification of positive area/tissue area was determined by thresholding for the Oil Red O signal (software TissueIA, version 4.0.7).

Real-Time quantitative PCR

Total RNA from tissues was extracted with TriPure reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 1 μg total RNA (Reverse Transcription System kit, Promega, Leiden, The Nederlands). Real-time qPCRs were performed using Mesa Fast qPCRTM (Applied Biosystems, Den Ijssel, The Netherlands and Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) for detection as previously described56. Ribosomal 7 protein L19 (RPL19) RNA was the housekeeping gene. Sequences of the primers are given in Supplementary File 1. All samples were run in duplicate and data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Western blot

Equal amount proteins from thoracic aorta and mesenteric arteries were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk or bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris-buffered saline tween-20. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies as previously described19. Gels were analysed and quantified by ImageQuantTM TL instrument (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, England).

Gut microbiota analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from the cecal content using a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, including a bead-beating step. 16S rDNA profiling, targeting V1-V3 hypervariable region and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq were performed as described previously57 and detailed in Supplementary File 1. For total bacteria, Bifidobacterium spp., Roseburia spp., Akkermansia muciniphila and Lactobacillus spp. quantification by qPCR, primers are detailed in Supplementary File 1 and conditions were based on 16S rRNA gene sequence and was described earlier21,33. For Alistipes spp., method was detailed in Supplementary File 1.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Within-groups variances were compared using a Bartlett’s test. If variances were significantly different between groups, values were normalized by Log-transformation before proceeding to the analysis. Dixon’s Q-test was performed to statistically reject outliers (95% confidence level). Differences between groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey post hoc test. For cecal bacteria, we used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Data with different superscript letters were significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) according to the post hoc ANOVA statistical analysis. Grouped analyses were assessed by two-way ANOVA. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.04 for windows.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

N.M.D. is a recipient of grants from FRS-FNRS, from Wallonia supported by the competitive cluster Wagralim (ADIPOSTOP project, convention 7366). C.D. is a senior research associate at FRS-FNRS. PDC, a senior research associate at the FRS-FNRS (Belgium), is a recipient of an ERC Starting Grant 2013 (336452-ENIGMO), Baillet Latour grant for medical research 2015 and is supported by the FRS-FNRS via the FRFS-WELBIO under Grant number WELBIO-CGR-2017. We thank V. Allaeys, B. Es Saadi and R. Selleslagh for technical assistance, R. M. Goebbels for histological assistance.

Author Contributions

A.M.N. and N.M.D. conceived and designed the experiment. A.M.N. and E.C. performed the experiment and analyzed the data. E.C. performed study of endothelial function. B.T. performed microbiota sequencing and qPCR of Alistipes. A.M.N. and N.M.D. wrote the paper. P.D.C., L.B.B., G.D. and C.D. provided intellectual input on the paper and reviewed the paper. N.M.D. planned and supervised all experiments and manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50700-4.

References

- 1.Schiattarella Gabriele G., Sannino Anna, Esposito Giovanni, Perrino Cinzia. Diagnostics and therapeutic implications of gut microbiota alterations in cardiometabolic diseases. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2019;29(3):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Munckhof ICL, et al. Role of gut microbiota in chronic low-grade inflammation as potential driver for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of human studies. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1719–1734. doi: 10.1111/obr.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunner H, et al. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Part II: Association with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. A statement by the Working Group on Endothelins and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2005;23:233–246. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juonala M, et al. Interrelations between brachial endothelial function and carotid intima-media thickness in young adults: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Circulation. 2004;110:2918–2923. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147540.88559.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loria P, et al. Cardiovascular risk, lipidemic phenotype and steatosis. A comparative analysis of cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic liver disease due to varying etiology. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.d’Uscio LV, et al. Mechanism of endothelial dysfunction in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1017–1022. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.21.6.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King VL, et al. A murine model of obesity with accelerated atherosclerosis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:35–41. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang YX. Cardiovascular functional phenotypes and pharmacological responses in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreyer SA, Wilson DL, LeBoeuf RC. C57BL/6 mice fed high fat diets as models for diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1998;136:17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)00165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonsson AL, Backhed F. Role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:79–87. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delzenne NM, Neyrinck AM, Cani PD. Modulation of the gut microbiota by nutrients with prebiotic properties: consequences for host health in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Microbial Cell Factories. 2011;10(S10):11–11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-s1-s10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delzenne N. M., Knudsen C., Beaumont M., Rodriguez J., Neyrinck A. M., Bindels L. B. Contribution of the gut microbiota to the regulation of host metabolism and energy balance: a focus on the gut–liver axis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2019;78(3):319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0029665118002756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delzenne NM, Neyrinck AM, Backhed F, Cani PD. Targeting gut microbiota in obesity: effects of prebiotics and probiotics. Nat.Rev.Endocrinol. 2011;7:639–646. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5:1417–1435. doi: 10.3390/nu5041417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Everard A, Neyrinck AM, Bindels LB. Gut microorganisms as promising targets for the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia: clinical and experimental diabetes and metabolism. 2015;58:2206–2217. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3712-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder BO, Backhed F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nat Med. 2016;22:1079–1089. doi: 10.1038/nm.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson GR, et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:491–502. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rault-Nania MH, et al. Inulin attenuates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:840–844. doi: 10.1017/BJN20061913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Catry E, et al. Targeting the gut microbiota with inulin-type fructans: preclinical demonstration of a novel approach in the management of endothelial dysfunction. Gut. 2018;67:271–283. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marzorati M. MV, Possemiers S. Fate of chitin-glucan in the human gastrointestinal tract as studied in a dynamic gut simulator (SHIME®) Journal of Functional Foods. 2017;30:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neyrinck AM, et al. Dietary modulation of clostridial cluster XIVa gut bacteria (Roseburia spp.) by chitin-glucan fiber improves host metabolic alterations induced by high-fat diet in mice. J.Nutr.Biochem. 2012;23:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cani PD, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Annals of Nutrition and metabolism. 2007;51:79–79. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neyrinck AM, et al. Polyphenol-rich extract of pomegranate peel alleviates tissue inflammation and hypercholesterolaemia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice: potential implication of the gut microbiota. The British Journal of Nutrition: an international journal of nutritional science. 2013;109:802–809. doi: 10.1017/s0007114512002206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engin AB. Adipocyte-Macrophage Cross-Talk in Obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:327–343. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelat M, et al. Rosuvastatin decreases caveolin-1 and improves nitric oxide-dependent heart rate and blood pressure variability in apolipoprotein E−/− mice in vivo. Circulation. 2003;107:2480–2486. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065601.83526.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druart C, Delzenne NM, Neyrinck AM, Salazar Garzo N, Alligier M. Modulation of the gut microbiota by nutrients with prebiotic and probiotic properties. Advances in Nutrition. 2014;5:624S–633S. doi: 10.3945/an.114.005835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazloom Kiran, Siddiqi Imran, Covasa Mihai. Probiotics: How Effective Are They in the Fight against Obesity? Nutrients. 2019;11(2):258. doi: 10.3390/nu11020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasahara K, et al. Interactions between Roseburia intestinalis and diet modulate atherogenesis in a murine model. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:1461–1471. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0272-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang Yongbo, Li Yu, Du Yuhui, Guo Liqiong, Chen Minghui, Huang Xinwei, Yang Fang, Hong Jingan, Kong Xiangyang. Konjaku flour reduces obesity in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. International Journal of Obesity. 2018;43(8):1631–1643. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He B, et al. Transmissible microbial and metabolomic remodeling by soluble dietary fiber improves metabolic homeostasis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10604. doi: 10.1038/srep10604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong C, Gao R, Yan X, Huang L, Qin H. Probiotics improve gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese mice fed a high-fat or high-sucrose diet. Nutrition. 2018;60:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plovier H, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107–113. doi: 10.1038/nm.4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everard A, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 2013;110:9066–9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Writing Group M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Fact sheet.

- 36.Simopoulos AP. An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients. 2016;8:128. doi: 10.3390/nu8030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casas Rosa, Castro-Barquero Sara, Estruch Ramon, Sacanella Emilio. Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018;19(12):3988. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.(2016).

- 39.Tilg H, Moschen AR, Roden M. NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Francque SM, van der Graaff D, Kwanten WJ. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiological mechanisms and implications. J Hepatol. 2016;65:425–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rath G, Dessy C, Feron O. Caveolae, caveolin and control of vascular tone: nitric oxide (NO) and endothelium derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) regulation. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 4):105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinonen I, et al. The effects of equal caloric high fat and western diet on metabolic syndrome, oxidative stress and vascular endothelial function in mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;211:515–527. doi: 10.1111/apha.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aoqui C, et al. Microvascular dysfunction in the course of metabolic syndrome induced by high-fat diet. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:31. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-13-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delgado NT, et al. Pomegranate Extract Enhances Endothelium-Dependent Coronary Relaxation in Isolated Perfused Hearts from Spontaneously Hypertensive Ovariectomized Rats. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:522. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stepankova R, et al. Absence of microbiota (germ-free conditions) accelerates the atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice fed standard low cholesterol diet. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2010;17:796–804. doi: 10.5551/jat.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velagapudi VR, et al. The gut microbiota modulates host energy and lipid metabolism in mice. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1101–1112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moschen AR, et al. Lipocalin 2 Protects from Inflammation and Tumorigenesis Associated with Gut Microbiota Alterations. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:455–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Druart C, et al. Gut microbial metabolites of polyunsaturated fatty acids correlate with specific fecal bacteria and serum markers of metabolic syndrome in obese women. Lipids. 2014;49:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s11745-014-3881-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Depommier C, et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia muciniphila in overweight and obese human volunteers: a proof-of-concept exploratory study. Nat Med. 2019;25:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Million M, et al. Correlation between body mass index and gut concentrations of Lactobacillus reuteri, Bifidobacterium animalis, Methanobrevibacter smithii and Escherichia coli. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1460–1466. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 51.Sun J, Buys N. Effects of probiotics consumption on lowering lipids and CVD risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2015;47:430–440. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1071872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fak F, Backhed F. Lactobacillus reuteri prevents diet-induced obesity, but not atherosclerosis, in a strain dependent fashion in Apoe−/− mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Hul, M. & Cani, P. D. Targeting Carbohydrates and Polyphenols for a Healthy Microbiome and Healthy Weight. Curr Nutr Rep, 10.1007/s13668-019-00281-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Zhang S, et al. Dietary pomegranate extract and inulin affect gut microbiome differentially in mice fed an obesogenic diet. Anaerobe. 2017;48:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catry E, et al. Nutritional depletion in n-3 PUFA in apoE knock-out mice: a new model of endothelial dysfunction associated with fatty liver disease. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2016;60:2198–2207. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suriano F, et al. Fat binding capacity and modulation of the gut microbiota both determine the effect of wheat bran fractions on adiposity. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(5621):5621–5613. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05698-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neyrinck AM, et al. Rhubarb extract prevents hepatic inflammation induced by acute alcohol intake, an effect related to the modulation of the gut microbiota. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2017;61(1500899):1500891–1500812. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.