Abstract

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL) type 1 (CLN1) is a neurodegenerative storage disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding the lysosomal enzyme palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1). CLN1 patients suffer from brain atrophy, mental and motor retardation, seizures, and retinal degeneration ultimately resulting in blindness. Here, we performed an in-depth analysis of the retinal phenotype of a PPT1-deficient mouse, an animal model of this condition. Reactive astrogliosis and microgliosis were evident in mutant retinas prior to the onset of retinal cell loss. Progressive accumulation of storage material, a pronounced dysregulation of various lysosomal proteins, and accumulation of sequestosome/p62-positive aggregates in the inner nuclear layer also preceded retinal degeneration. At advanced stages of the disease, the mutant retina was characterized by a significant loss of ganglion cells, rod and cone photoreceptor cells, and rod and cone bipolar cells. Results demonstrate that PPT1 dysfunction results in early-onset pathological alterations in the mutant retina, followed by a progressive degeneration of various retinal cell types at relatively late stages of the disease. Data will serve as a reference for future work aimed at developing therapeutic strategies for the treatment of retinal degeneration in CLN1 disease.

Subject terms: Experimental models of disease, Experimental models of disease, Neurodegeneration, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL) comprise a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of lysosomal storage disorders that is characterized by an intracellular accumulation of autofluorescent storage material, progressive neurodegeneration and premature death. Although it is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of 1:14,000 to 1:67,000 depending on the ethnic group and founder group effects, NCLs constitute the major group of neurodegenerative diseases in childhood1–3. Originally classified mainly according to the age at disease onset, the different NCLs are now grouped according to the affected gene (CLN1-CLN8 and CLN10-CLN14)4–7. Patients present with brain atrophy, mental and motor retardation, and epileptic seizures, and die prematurely. Retinal degeneration resulting in visual impairment and ultimately blindness is another characteristic clinical feature of most NCLs6,8–12.

NCL type 1 (CLN1) disease, also termed infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL) or infantile Batten disease, is caused by mutations in the PPT1 gene on chromosome 1p34.213. Until now, 71 mutations and 9 polymorphisms have been identified in the PPT1 gene [https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ncl-disease/] which encodes the soluble lysosomal enzyme palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1). The enzyme is involved in the lysosomal degradation of lipid-modified proteins by removing thioester-linked fatty acyl groups from cysteine residues, and has been implicated in synaptogenesis, regulation of synaptic vesicle endo- and exocytosis, endosomal trafficking and lipid metabolism5,7,8. While PPT1 is ubiquitously expressed, high PPT1 enzymatic activity has been shown in the brain and particularly in the retina14,15.

Clinically, CLN1 disease is characterized by an early-onset and rapidly progressing cerebral atrophy resulting in deterioration of cognitive and motor functions11,16–19. Mental retardation becomes obvious at about 9–19 months of age, and is accompanied by an early loss of motor functions resulting in hypotonia, ataxia and myoclonic jerks11,19,20. Epileptic seizures usually occur at advanced stages of the disease, and patients die at about 10 years of age20,21. In addition to this most prevalent CLN1 disease ‘classic infantile NCL’ (INCL) variant, patients harboring mutations in the PPT1 gene might develop first clinical symptoms later in life, and present with a more slowly progressing late-infantile, juvenile or adult onset NCL22–28.

Retinal degeneration resulting in vision loss is another hallmark of CLN1 disease, and visual impairment is usually diagnosed at about 12–22 months of age19. Ophthalmic examinations demonstrated maculopathy with pigmentary alterations, atrophy of the optic nerve and retinal vessel attenuation11,16,17. Furthermore, electroretinogram (ERG) recordings revealed an early-onset and rapidly progressing deterioration of visual function16,17,29. Histological analyses of the retina of a CLN1 patient at a late stage of the disease revealed autofluorescent storage material throughout the retina, and significant loss of photoreceptor cells, neurons of the inner nuclear layer, and ganglion cells17. In comparison, CLN1 patients with a later onset of the disease presented with night blindness and moderate visual impairment as juveniles, resulting in progressive vision loss and extinguished ERGs at later ages23,27,28. A slowly progressing visual impairment was also observed in CLN1 patients with an adult onset of the disease. Deterioration of visual function was accompanied by no or only mild funduscopic abnormalities, such as pallor of the optic nerve and pigmentary alterations of the macula25,26.

Several transgenic mouse models of CLN1 disease have been generated, and all have been shown to faithfully recapitulate many of the pathological features observed in CLN1 patients, such as accumulation of autofluorescent granular osmiophilic deposits in neural and visceral tissues, rapidly progressing neurodegeneration in the brain, motor abnormalities, seizures and premature death30–33. Analyses of the retina of these mutants demonstrated accumulation of storage material, thinning of different retinal layers, and loss of photoreceptor cells and retinal ganglion cells. In addition, behavioral tests and ERG recordings have demonstrated progressive deterioration of retinal function31,32,34–36. However, detailed information about the progression of retinal degeneration, the molecular changes associated with the retinal pathology, and the impact of PPT1 deficiency on specific retinal neurons, such as rod and cone photoreceptor cells or specific retinal interneurons, is limited. In the present study, we therefore performed an in-depth analysis of the retinal phenotype of a Ppt1 knock-out (ko) mouse. Specifically, we performed biochemical and ultrastructural analyses of the storage material, analyzed the expression of various lysosomal proteins, and quantified retina thinning and the loss of different retinal cell types during the course of the disease. Results of the present study will serve as a reference for future work aimed at establishing therapeutic strategies for the treatment of retinal degeneration in CLN1 disease.

Material and Methods

Animals

Ppt1 ko mice30 and wild-type mice were maintained on a C57BL/6J genetic background and housed under standard conditions in the specific pathogen-free animal facility of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany). For both genotypes male and female mice were included in the analyses, with no significant differences of the obtained results between sexes. All animal experiments were approved by the ‘Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Behörde für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz’ (reference number: ORG842) and were in accordance with the EU Directive for animal experiments.

Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy

Immunohistochemical analyses of mutant retinas were performed as described37–39. In brief, Ppt1 ko and wild-type mice were sacrificed at the age of 45, 112 or 240 days, and eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cryoprotected and frozen. Cryostat sections, 25 µm in thickness, were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.3% Triton X-100 (TX-100; both from Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany), incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1), washed in PBS, and incubated with Cy2- or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). Cone photoreceptor cells were labelled with biotinylated peanut agglutinin (PNA; 1:5,000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) followed by Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (1:500; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Sections were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich), washed, and mounted onto slides. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) were additionally visualized in retina flatmounts using antibodies to brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein-3A (BRN-3A) as described40. Retinal sections and flatmounts from Ppt1 ko and age-matched wild-type mice were processed in parallel for each antigen to allow for direct comparison of staining intensities. At least six animals were analyzed for each antigen, genotype and age. For qualitative documentation, z-stacks were taken from central retinal regions close to the optic disc with an AxioObserverZ.1 microscope equipped with an ApoTome.2 (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using identical microscope settings for each antigen. Ultrastructural analyses of retinas from 240-day-old Ppt1 ko and wild-type mice (n = 3 for each genotype) were performed as described37,38.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies.

| Antigen | Dilution | Company/Reference | Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| brain-specific homeobox/POU domain protein 3A (BRN-3A); (IHC) | 1:200 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA | Sc-31984 |

| cathepsin D (CTSD); (IHC, WB) |

1:100 (IHC) 1:1000 (WB) |

R&D Systems GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany | AF1029 |

| cathepsin X/Z/P (CTSZ); (IHC, WB) |

1:100 (IHC) 1:1000 (WB) |

R&D Systems GmbH | AF1033 |

| cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68); (IHC) | 1:1000 | Bio-Rad-Laboratories, Kidlington, UK | MCA1957 |

| glycerinaldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); (WB) | 1:1000 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. | Sc-25778 |

| glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); (IHC) | 1:500 | Dako Cytomation GmbH, Hamburg, Germany | Z0334 |

| ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1); (IHC) | 1:200 | Wako Chemicals GmbH, Neuss, Germany | 019–19741 |

| lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1); (IHC, WB) |

1:2000 (IHC) 1:250 (WB) |

Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, USA |

Clone 1D4B |

| lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2); (IHC, WB) |

1:200 (IHC) 1:250 (WB) |

Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Clone ABL-93 |

| protein kinase C alpha (PKCα); (IHC) | 1:500 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. | Sc-208 |

| saposin D; (IHC, WB) | 1:2000 | Konrad Sandhoff, Bonn, Germany94 | |

| secretagogin (SCGN); (IHC) | 1:2000 | BioVendor Research and Diagnostic Products, Brno, Czech Republic | RD184120100 |

| sequestosome 1/p62 (SQSTM1/p62); (IHC) | 1:1000 | Enzo Life Sciences, Lausen, Switzerland | BML-PW9860 |

| SQSTM1/p62; (WB) | 1:1000 | Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA | 5114 |

| subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase; (IHC) | 1:1000 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK | ab181243 |

| anti-α-tubulin (WB) | 1:5000 | Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany | T9026 |

IHC: immunohistochemistry, WB: Western blot.

Determination of retina thickness and retinal nerve cell numbers

Optical sections with a thickness of 0.25 µm were taken from the nasal to the temporal periphery of central (i.e. in the plane of the optic disc) retinal sections using an AxioObserverZ.1 microscope equipped with an ApoTome.2. The thickness of the entire retina (i.e. from the retinal pigment epithelium to the vitreal margin of the retina), the inner retina (i.e. from the outer plexiform layer to the vitreal margin of the retina) and the inner nuclear layer was measured at nine equidistant positions of both the nasal and temporal retina. Rows of photoreceptor cell nuclei were counted at the same positions. PNA-labeled cone photoreceptor cells and BRN-3A-positive RGCs were counted over the entire length of central retinal sections. Cones were only counted when their inner segments were in direct contact with the outer nuclear layer. RGCs were counted provided they had a clearly visible DAPI-stained nucleus. Numbers of BRN-3A-positive RGCs were additionally determined in retinal flatmounts from 240-day-old animals as described40. The density of protein kinase C alpha (PKCα)-positive rod bipolar cells and secretagogin (SCGN)-positive cone bipolar cells with clearly visible DAPI-labeled nuclei was determined in three equidistant areas each with a length of 250 µm in both the nasal and temporal retinal half. GFAP-positive Müller cell processes that crossed a line at half height of the inner plexiform layer were counted in nasal and temporal retinal halfs in areas (500 µm in width) located midway between the optic disc and retinal periphery. The mean gray value and the integrated density (i.e. mean gray value x immunoreactive area) of the GFAP immunostaining signal in retinal astrocytes was determined in the same retinal areas using ImageJ software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Mean gray values and integrated density values of the GFAP fluorescence were compared between mutant and age-matched wild-type retinas that were processed in the same immunostainings and photographed using the same microscope settings. Six Ppt1 ko mice and six wild-type mice were analyzed for each antigen and age. Finally, we determined the percentage of CD68-positive cells showing strong immunoreactivity for CTSD or CTSZ and of IBA1-positive cells showing strong immunoreactivity for CTSD, CTSZ, LAMP1 or LAMP2 in z-stacks through the entire thickness of retina sections (25 µm) from P240 Ppt1 ko retinas (n = 6). Countings were done in the nasal and temporal retinal half in areas (500 µm width) located midway between optic disc and retinal periphery. All quantitative analyses were performed in a blinded fashion on number-coded retinal sections and flatmounts. Statistical analyses of cell counting and thickness measurements were performed using the two-way ANOVA and three-way ANOVA, respectively, followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test. Statistical analyses of ganglion cell densities in retinal flatmounts were done with the Mann-Whitney U test. Mean intensity and integrated density values of the GFAP immunostaining signal in retinal astrocytes were analyzed using the paired Student’s t-test.

Retinal protein extraction and western blotting

Total protein homogenates were prepared from 240-day-old Ppt1 ko and age-matched control retinas by suspension in 200 µl ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 1% TX-100 supplemented with protease inhibitors) followed by incubation of protein extracts for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 16,000xg for 10 min, protein concentrations of supernatants were determined using Bradford protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) and BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) as a standard.

Extraction of proteins from retinas for the detection of prosaposin and saposin D by immunoblotting was performed as described41. For the detection of sequestosome 1/p62 (SQSTM1/p62), retinas were homogenized in 200 µl 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors. After addition of 50 µl 10% SDS (final concentration: 2%), homogenates were sonicated for three times using a microtip sonifier and cleared by centrifugation for 10 min at 16.000xg. Protein concentrations of supernatants were determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Aliquots of total protein extracts (30 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes and processed for immunoblotting. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and quantified using the ChemiDoc XRS system and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). Molecular masses of immunoreactive proteins were determined by comparison with the electrophoretic mobility of prestained standard proteins (Page Ruler™, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each experiment was performed in triplicate on retinal extracts from different Ppt1 ko and age-matched control mice. Statistical analyses of data were performed using the Student’s t-test.

Results

In the present study, we performed an in-depth analysis of the retinal phenotype of a PPT1-deficient mouse, an animal model of CLN1 disease. Using immunohistochemistry, morphometry, electron microscopy and immunoblot analyses we provide data about the onset and the progression of the retinal dystrophy, and the molecular and cellular changes associated with the retinal pathology.

Early-onset retinal pathology in the Ppt1 ko mouse

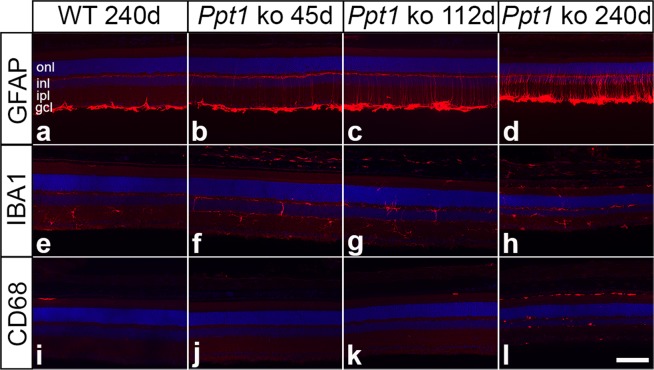

To determine the onset of the retinal pathology in the Ppt1 ko mouse, we analyzed the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1) and cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68) in central retinal sections of mutant and wild-type mice at different ages. Expression of GFAP in wild-type mice was detectable in retinal astrocytes and a few Müller cells at all ages analyzed (for a 240-day-old wild-type retina, see Fig. 1a). In Ppt1 ko retinas, in comparison, the number of GFAP-positive Müller cells was significantly increased at P45, P112 and P240 when compared with age-matched control retinas (Fig. 1b–d, Supplementary Fig. 1a; p < 0.001 for all comparisons; two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test). Furthermore, the mean intensity of the GFAP immunostaining signal in retinal astrocytes of Ppt1 ko mice was slightly but significantly elevated at P45 and P112 (p < 0.05 for both comparisons, paired Student’s t-test), and strongly increased at P240 (p < 0.001) when compared with age-matched wild-type mice (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Integrated density values for the GFAP immunostaining signal in retinal astrocytes were similar between wild-type and Ppt1 ko retinas at P45, but significantly increased in mutant retinas at P112 and P240 when compared to age-matched control retinas (p < 0.001 for both comparisons; Supplementary Fig. 1c). Together, data demonstrate an early-onset reactive astrogliosis in the retina of PPT1-deficient mice.

Figure 1.

Reactive astrogliosis and microgliosis in PPT1-deficient retinas. Expression of GFAP, IBA1 and CD68 in wild-type and Ppt1 ko retinas. Note the presence of some faintly GFAP-positive Müller cells in mutant retinas at P45 (b). The number of positive Müller cells and expression levels of GFAP increased considerably with increasing age of the mutants (c,d). IBA-1-positive microglial cells were restricted to the inner retina of mutant mice at P45 (f), but became detectable in the outer retina and subretinal space at P112 (g) and P240 (h). A few CD68-positive cells were present in the outer retina of 112-day-old mutants (k), and their number was considerably increased in P240 Ppt1 ko retina, particularly in the subretinal space (l). Immunostainings of 240-day-old wild-type retinas are shown for comparison (a,e,i). gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar in (l) (for a–l): 100 µm.

Cell bodies of IBA1-positive microglia cells were restricted to the inner retina (Fig. 1f), while CD68-positive cells were virtually absent from mutant retinas at P45 (Fig. 1j). At this age, some IBA1-positive cells in mutant retinas, but not in wild-type retinas, extended processes into the outer nuclear layer. In 112-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas, a few IBA1- (Fig. 1g) and CD68-positive cells (Fig. 1k) became additionally detectable in the outer nuclear layer and in the subretinal space, and their number increased considerably until P240, particularly in the subretinal space (Fig. 1h,l). In wild-type mice, in comparison, subretinally located IBA1- or CD68-positive microglia/macrophages were not detected in young animals, and were only rarely observed in 240-day-old mice (Fig. 1e,i).

Accumulation of storage material

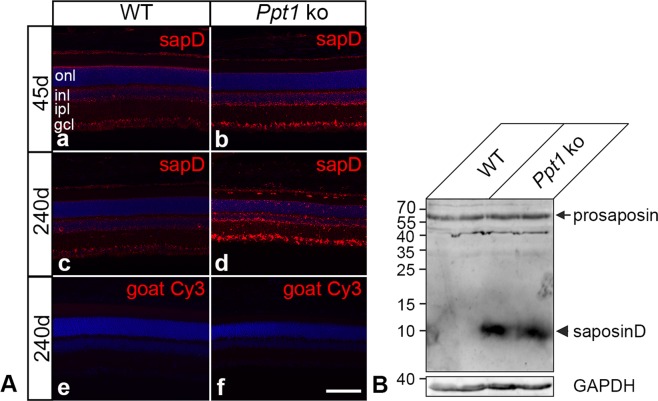

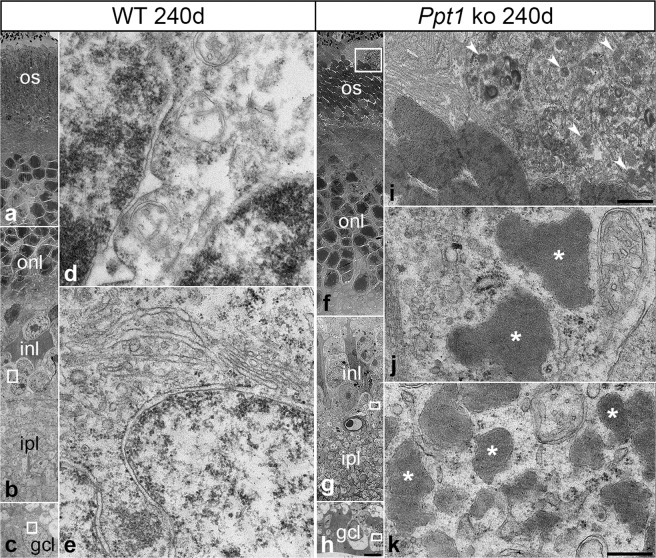

A hallmark of NCL is the accumulation of autofluorescent storage material composed of low molecular weight hydrophobic proteins, mainly subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase and/or sphingolipid activator proteins (saposins) A and D42,43. Immunostainings revealed slightly elevated levels of saposin D in P45 mutant retinas (Fig. 2Ab) when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (Fig. 2Aa). At this age, elevated levels of saposin D were mainly detected in the ganglion cell layer and inner nuclear layer of Ppt1 ko retinas. At P240 saposin D-immunoreactivity was markedly increased throughout the mutant retina, and was particularly pronounced in the ganglion cell layer and in microglia/macrophages (compare Fig. 2Ad with Ac). Retinal sections incubated with the secondary antibody only were negative (Fig. 2Ae,Af). Immunoblot analyses confirmed the immunohistochemical observations, and revealed markedly increased levels of saposin D in 240-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas when compared to age-matched control retinas (Fig. 2B). Levels of prosaposin, in contrast, were not significantly different between genotypes (Fig. 2B). At the ultrastructural level, we found electron-dense storage material in all cell types of the mutant retina, including photoreceptor cells, retinal interneurons and retinal ganglion cells (Fig. 3f–k). Similar electron-dense structures were not apparent in wild-type retinas (Fig. 3a–e). Storage material was particularly pronounced in subretinally located microglia/macrophages, and displayed the typical ultrastructure of granular osmiophilic deposits (Fig. 3f–k, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Accumulation of Saposin D in Ppt1 ko retinas. (A) Immunohistochemical analyses revealed moderately and markedly elevated levels of saposin D in 45- (b) and 240-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas (d) respectively when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (a and c, respectively). No fluorescence signal was detectable when wild-type (e) or mutant (f) retinal sections were incubated with secondary antibodies only. (B) Immunoblot analyses confirmed markedly increased levels of saposin D (arrowhead) in 240-day-old mutant retinas, and revealed similar levels of prosaposin (arrow) in both genotypes. GAPDH immunoblotting was performed as a loading control. Positions of molecular mass markers are indicated. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar in (f) (for a–f): 100 µm.

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural analysis of storage material in the retina of Ppt1 ko mice. Low-power electron micrographs depict the different layers of a 240-day-old wild-type (a–c) and age-matched Ppt1 ko retina (f–h). Analyses of the boxed areas in (f–h) at higher magnification revealed the presence of granular osmiophilic deposits in subretinally located macrophages (arrowheads in i), retinal interneurons (asterisks in j) and retinal ganglion cells (asterisks in k) respectively of Ppt1 ko retinas. Similar cytoplasmic inclusions were not detectable in retinas of age-matched control mice (d,e). gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer; os: outer segments. Scale bar in (h) (for a–c,f–h): 5 μm; in (i): 1 μm; in (k) (for d,e,j,k): 0.2 μm.

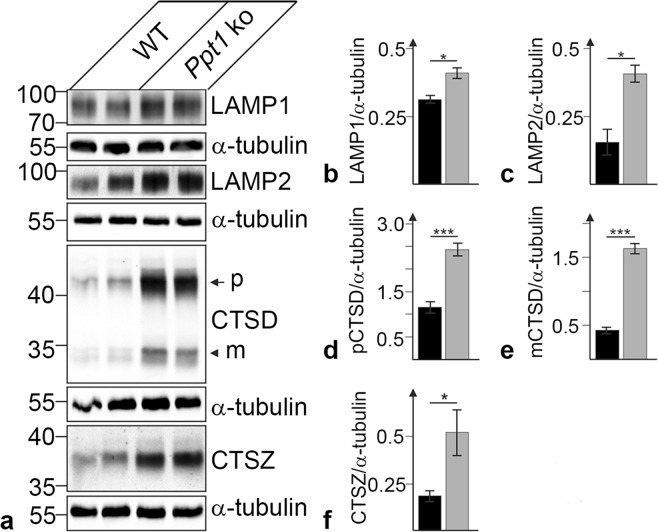

Dysregulation of lysosomal proteins

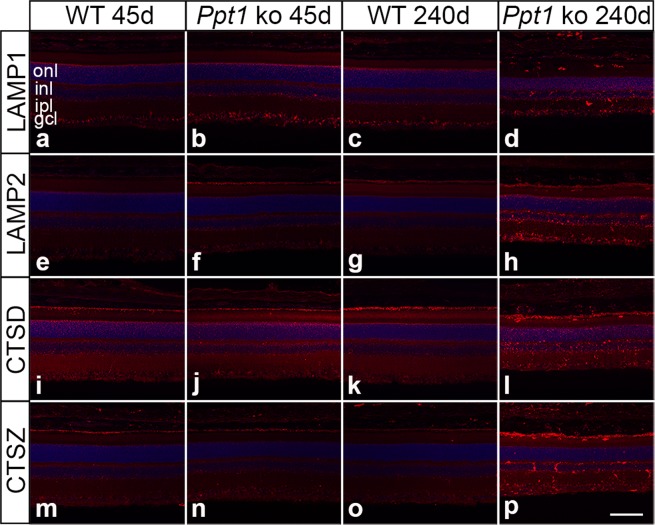

The impact of PPT1 deficiency on expression levels of various lysosomal proteins was studied by immunohistochemistry and immunoblot analyses. Immunostainings revealed slightly elevated levels of lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2) and the soluble lysosomal enzymes cathepsin D (CTSD) and cathepsin X/Z/P (CTSZ) in mutant retinas at P45 (Fig. 4b,f,j,n) when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (Fig. 4a,e,i,m). Moderately and markedly elevated expression levels of these lysosomal proteins were detected in Ppt1 ko mice at P112 (not shown) and P240 (Fig. 4d,h,l,p) respectively when compared to control mice (Fig. 4c,g,k,o). In 240-day-old mutant retinas, LAMP1-, LAMP2-, CTSD- and CTSZ-immunoreactivity was particularly pronounced in microglia/macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 3a–f″). Quantitative analyses revealed strong CTSD- and CTSZ-immunoreactivity in 97.9 ± 1.4% (mean ± SEM) and 96.7 ± 1.6% respectively of CD68-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. 3g). Furthermore, we found pronounced immunoreactivity for CTSD, CTSZ, LAMP1 and LAMP2 in 69.9 ± 1.7%, 82.4 ± 2.8%, 75.1 ± 2.3% and 67.9 ± 4.5% respectively of IBA1-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. 3g).

Figure 4.

Dysregulation of lysosomal proteins in PPT1-deficient retinas. Expression levels of LAMP1, LAMP2, CTSD and CTSZ were slightly elevated in 45-day-old mutant animals (b,f,j,n, respectively) when compared to age-matched wild-type mice (a,e,i,m, respectively). Pronounced upregulation of LAMP1-, LAMP2-, CTSD- and CTSZ-immunoreactivity was observed in 240-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas (d,h,l,p, respectively). The corresponding immunostainings of P240 control retinas are shown in (c,g,k,o), respectively. gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar in (p) for (a–p): 100 µm.

In agreement with the immunohistochemical data, immunoblot analyses revealed significantly elevated levels of LAMP1, LAMP2, CTSD and CTSZ in mutant retinas at P240 when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (Fig. 5). Quantitative analyses of the immunoblots revealed that expression levels in Ppt1 ko retinas were increased 1.3-fold for LAMP1 (p < 0.05; Student’s t-test), 2.6-fold for LAMP2 (p < 0.05), 2.1-fold for the CTSD precursor protein (p < 0.01), 3.9-fold for mature CTSD (p < 0.01), and 2.8-fold for CTSZ (p < 0.05) when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (Fig. 5b–f).

Figure 5.

Dysregulation of lysosomal proteins in Ppt1 ko retinas. Immunoblot analyses revealed elevated levels of LAMP1, LAMP2, CTSD and CTSZ in 240-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (a). α-tubulin immunoblotting was performed as a loading control. Positions of the molecular mass markers and the precursor (p) and mature (m) form of CTSD are indicated (a). Quantitative analyses of immunoblots demonstrated significantly increased levels of LAMP1 (b), LAMP2 (c), the precursor (d) and mature (e) form of CTSD, and CTSZ (f). Bars represent mean values (±SEM) of protein levels from three independent experiments normalized to the amounts of α-tubulin in 240-day-old wild-type (filled bars) and age-matched Ppt1 ko retinas (grey bars). Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 according to the Student’s t-test.

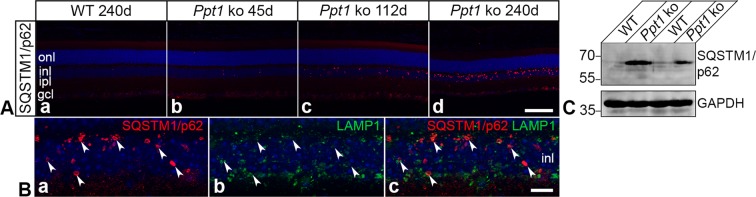

Regionally restricted expression of SQSTM1/p62 in Ppt1 ko retinas

Expression of the autophagy marker SQSTM1/p62 was not detectable in wild-type retinas at any age analyzed (for a P240 control retina, see Fig. 6Aa). In the mutant, in contrast, a few SQSTM1/p62-positive punctae were detectable at P45 (Fig. 6Ab), and their density increased considerably with increasing age of the mutants (Fig. 6Ac,Ad). Of note, SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates were restricted to the inner nuclear layer of mutant retinas at all ages analyzed. Furthermore, double immunostainings revealed hardly any co-localization of SQSTM1/p62 with the lysosomal marker LAMP1 (Fig. 6Ba–Bc). Immunoblot analyses of retinas from P240 mutant and wild-type mice confirmed significantly elevated amounts of SQSTM1/p62 in Ppt1 ko retinas (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Expression of SQSTM1/p62 in the retina of Ppt1 ko mice. (A) SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates were detectable in the retina of 45-day-old mutants (Ab) and increased in number and size with increasing age of the animals (Ac,Ad). Note that the immunoreactive punctae were restricted to the inner nuclear layer at all ages analyzed (Ab–Ad). Wild-type retinas were devoid of SQSTM1/p62-positive punctae (for a 240-day-old animal, see Aa). (B) There was either no or only partial co-localization of SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates (Ba) with LAMP1 (Bb) in P240 Ppt1 ko retinas (arrowheads in Ba–Bc). (C) Immunoblot analyses of retinas at P240 confirmed markedly elevated levels of SQSTM1/p62 in mutant retinas when compared to control retinas. GAPDH immunoblotting was performed as a loading control. Positions of the molecular mass markers are indicated. Uncropped blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar in (Ad) for (Aa–Ad): 100 µm; in (Bc) for (Ba–Bc): 10 µm.

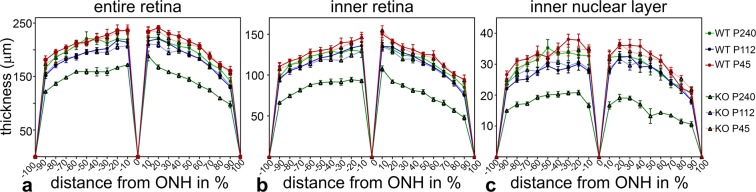

Thinning of the Ppt1 ko retina

To analyze the progression and extent of retinal degeneration in Ppt1 ko mice, we first determined the thickness of the entire retina, the inner retina (i.e. from outer plexiform layer to vitreal retina margin) and the inner nuclear layer in 45-, 112- and 240-day-old mutant and wild-type retinas (Fig. 7). Analyses revealed an age-dependent decrease of the thickness of the entire retina, inner retina and inner nuclear layer of Ppt1 ko mice when compared to wild-type mice that was independent of the retinal position (effect of the interaction between age and genotype: p < 0.001 according to the three-way ANOVA). Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed significant differences between mutant and wild-type retinas only at P240 (entire retina: Ppt1 ko 147.7 ± 5.5 µm (mean ± SEM), wild-type 199.5 ± 5.7 µm, p < 0.001; inner retina: Ppt1 ko 81.1 ± 3.6 µm, wild-type 118.1 ± 3.3 µm, p < 0.001; inner nuclear layer: Ppt1 ko 16.7 ± 0.3 µm, wild-type 29.6 ± 1.0 µm, p < 0.001; Fig. 7a–c). Significant thinning of the entire retina, inner retina and inner nuclear layer at P240 suggests the loss of various retinal cell types in the mutant at advanced stages of the disease.

Figure 7.

Thickness of the entire retina, inner retina and inner nuclear layer of Ppt1 ko and age-matched wild-type mice. The thickness of the entire retina (a), inner retina (b) and inner nuclear layer (c) was similar in 45- or 112-day-old Ppt1 ko and wild-type mice, but significantly reduced in P240 mutants when compared to age-matched wild-type mice (p < 0.001 for all comparisons between 240-day-old mutant and wild-type mice; three-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test). Values represent the mean ± SEM from six animals of each age and genotype. ONH: optic nerve head.

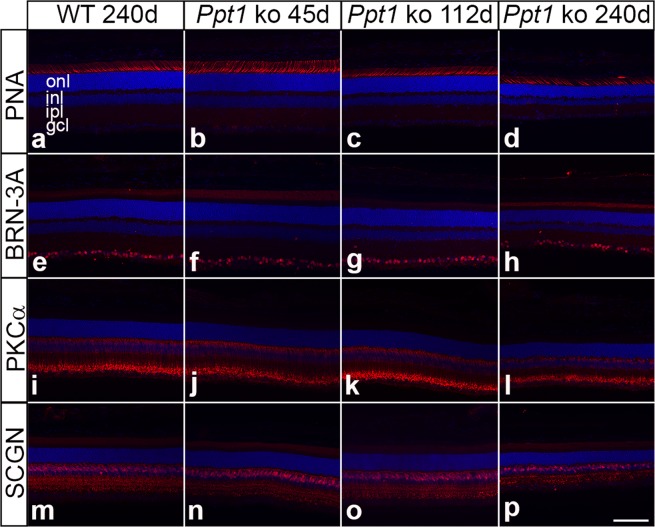

Degeneration of photoreceptor cells

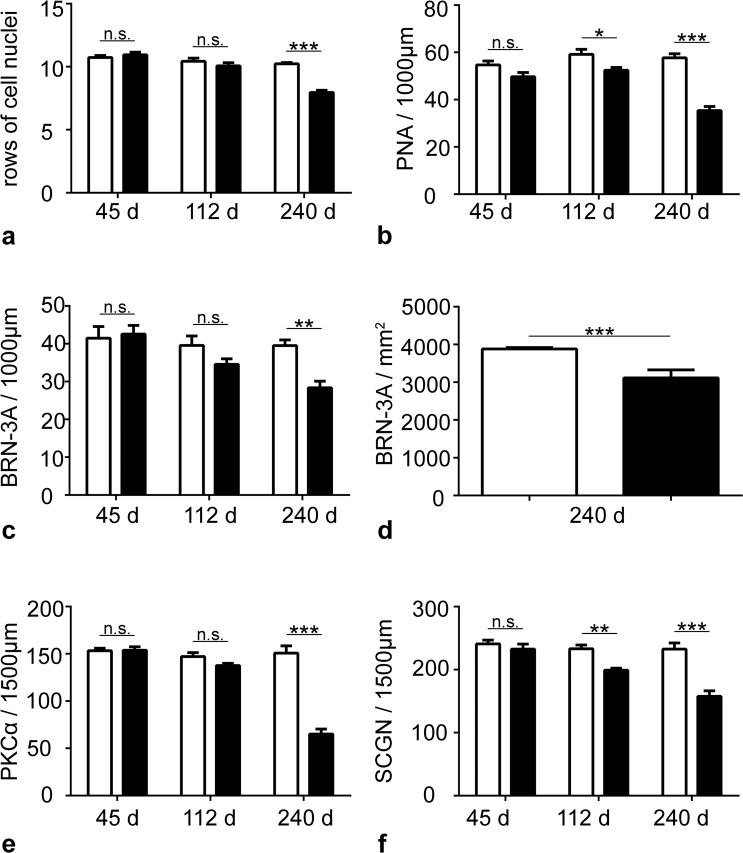

To analyze the impact of PPT1 deficiency on photoreceptor cells, we first determined the number of rows of DAPI-labelled photoreceptor cell nuclei (Fig. 8). This analysis revealed similar numbers of photoreceptor cells in Ppt1 ko and age-matched control retinas at P45 and P112 (Fig. 9a). In 240-day-old animals, in comparison, we found 10.2 ± 0.1 (mean ± SEM) rows of photoreceptor cell nuclei in wild-type mice compared to 8.0 ± 0.2 rows of nuclei in mutant mice (p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test), demonstrating that more than 20% of photoreceptors were lost at this age in the mutant (compare Figs 8a,d, 9a). To study whether cone and rod photoreceptor cells are differentially affected, we next determined the density of PNA-labeled cones (Fig. 8a–d). In 45-day-old animals, the number of cones per 1000 µm retina length was not significantly different between Ppt1 ko (49.7 ± 1.8; mean ± SEM) and age-matched wild-type mice (54.7 ± 1.6; Fig. 9b). At P112 and P240, however, the number of cones was significantly reduced in mutant retinas by 11.4% (p < 0.05) and 38.7% (p < 0.001) respectively when compared to control retinas (Figs 8a–d, 9b). Together with the progressive loss of photoreceptor cell nuclei, data demonstrate degeneration of both cone and rod photoreceptors, and indicate that cones are more susceptible to PPT1 dysfunction than rods.

Figure 8.

Degeneration of various retinal cell types in PPT1-deficient mice. The density of PNA-labelled cone photoreceptor cells, BRN-3A-positive retinal ganglion cells, PKCα-positive rod bipolar cells and SCGN-positive cone bipolar cells in 45-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas (b,f,j,n, respectively) was similar to that observed in wild-type retinas (a,e,i,m, respectively). Retinas from 112-day-old Ppt1 ko mice also contained normal numbers of retinal ganglion cells (g) and rod bipolar cells (k), but decreased densities of cone photoreceptor cells (c) and cone bipolar cells (o). Note the significant decrease in the number of all cell types in 240-day-old mutant retinas (d,h,l,p) when compared to age-matched wild-type retinas (a,e,i,m). gcl: ganglion cell layer; inl: inner nuclear layer; ipl: inner plexiform layer; onl: outer nuclear layer. Scale bar in (p) for (a–p): 100 µm.

Figure 9.

Degeneration of various retinal cell types in Ppt1 ko mice. The number of rows of photoreceptor nuclei (a) and the density of PNA-labeled cone photoreceptor cells (b), BRN-3A-positive retinal ganglion cells in retinal sections (c) or retinal flatmounts (d), PKCα-positive rod bipolar cells (e) and SCGN-positive cone bipolar cells (f) were determined in 45-, 112- and 240-day-old Ppt1 ko (filled bars) and wild-type mice (open bars). Each bar represents the mean value ± SEM of six animals. Statistical analyses of data were performed with the two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test (a–c,e,f) or the Mann-Whitney U test (d). n.s.: not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Degeneration of retinal ganglion cells

To study the consequences of PPT1 deficiency on nerve cell types of the inner retina, we next determined the density of BRN-3A-positive ganglion cells. Analyses of retinal sections (Fig. 8e–h) revealed similar densities of ganglion cells in mutant and wild-type retinas at P45 and P112 (Fig. 9c), in line with a normal thickness of the inner retina of Ppt1 ko mice at these ages (Fig. 7b). At P240, however, the number of ganglion cells per 1000 µm retina length was significantly reduced in the mutant mice (28.4 ± 1.75; mean ± SEM; Fig. 8h) when compared to wild-type mice (39.5 ± 1.5; p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test; Figs 8e, 9c). A significant loss of ganglion cells in 240-day-old Ppt1 ko mice was confirmed by analyses of BRN-3A-stained retinal flatmounts (Supplementary Fig. 4) which revealed 3112.8 ± 87.5 ganglion cells/mm2 in Ppt1 ko retinas as opposed to 3879.7 ± 15.5 ganglion cells/mm2 in wild-type retinas (Fig. 9d; p < 0.001; Mann-Whitney U test).

Early and pronounced loss of bipolar cells

Significant thinning of the inner nuclear layer of mutant retinas at P240 (Fig. 7c) suggests the loss of retinal interneurons at late stages of the disease. We therefore immunostained mutant and wild-type retinas with antibodies to PKCα (Fig. 8i–l) and SCGN (Fig. 8m–p) to visualize rod and cone bipolar cells, respectively. Mutant and wild-type retinas contained similar numbers of both bipolar cell types at P45 (Fig. 9e,f). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the density of rod bipolar cells between both genotypes at P112 (Fig. 9e). However, the density of cone bipolar cells was significantly reduced at this age with 199.2 ± 3.1 (mean ± SEM) cone bipolar cells per 1500 µm retina length in Ppt1 ko retinas compared to 233.2 ± 6.1 cone bipolar cells per 1500 µm retina length in wild-type retinas (Fig. 9f; p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test). In 240-day-old Ppt1 ko retinas, we found a pronounced loss of both rod and cone bipolar cells (compare Fig. 8l with i and Fig. 8p with m, respectively). The density of PKCα-positive rod bipolar cells was reduced by 57% from 150.8 ± 7.5 cells per 1500 µm retina length in wild-type retinas to 65.2 ± 5.2 cells per 1500 µm retina length in Ppt1 ko retinas (Fig. 9e; p < 0.001), while the density of SCGN-positive cone bipolar cells was reduced by 32% from 232.7 ± 9.6 cells per 1500 µm retina length in wild-type retinas to 157.7 ± 8.7 cells per 1500 µm retina length in Ppt1 ko retinas (Fig. 9f; p < 0.001).

Discussion

Retinal degeneration and loss of vision is a characteristic clinical symptom of most NCLs, and among the first clinical signs in CLN1 patients6,9,17,20,43. We therefore performed an in-depth analysis of the retinal phenotype of a PPT1-deficient mouse30 to gain insight into the molecular and cellular changes and the progression of the retinal dystrophy caused by PPT1 dysfunction. Accumulation of storage material, reactive astrogliosis and microgliosis, dysregulation of lysosomal proteins and elevated levels of the autophagy marker SQSTM1/p62 were evident early in the disease course. Progressive degeneration of various retinal cell types, in comparison, became apparent at significantly later stages of the disease.

Accumulation of autofluorescent storage material with a protein composition and ultrastructural appearance characteristic for different NCL forms is a hallmark of the disease. While subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase prevails in most NCLs, saposin A and D comprise the major protein components of storage material in CLN1, CLN4 and CLN10 disease43–46. In the Ppt1 ko retina, levels of saposin D were elevated at P45, more than two months before we observed a moderate but significant loss of some retinal cell types. Levels of saposin D further increased until the end stage of the disease when storage material resembling the ultrastructure of granular osmiophilic deposits was found in all retinal cell types and microglia/macrophages. While accumulation of storage material clearly preceding the onset of neurological symptoms has also been noted in other studies, both in CLN1 animal models and CLN1 patients30,31,44,47, its relevance for the pathogenesis of the disease is largely unknown. In brains of a sheep CLN6 model, for instance, distribution and amount of storage material correlated only partially with the extent of neurodegeneration48,49, and experimental work on Ctsd ko mice indicated that nerve cells can tolerate large amounts of storage material50.

Reactive astrogliosis and first signs of microglia activation in Ppt1 ko retinas were also evident more than two months before we observed a significant loss of some retinal cell types. Activation of astrocytes and microglia and infiltration of lymphocytes prior to significant neurodegeneration in CLN1 mouse models suggests a critical role of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of the disease31,35,51–53. In support of this view, genetic and pharmacological immunomodulatory therapeutic approaches targeting the innate or adaptive immune system have indeed been shown to delay the thinning of inner retinal layers and the loss of retinal ganglion cells in the Ppt1 ko retina35,54,55. Whether the degeneration of other retinal cell types affected in the PPT1-deficient retina was also attenuated by these treatments was, however, not analysed in these studies. Early-onset microgliosis has recently also been reported to closely accompany light-induced retinal degeneration in the Cln3Δex7/8 mouse model of CLN3 disease56 and the progressive loss of photoreceptor cells in the nclf mouse model of CLN6 disease57. Interestingly, treatment of Cln3Δex7/8 mice with the immunomodulatory compound minocycline or of nclf mice with the immunomodulatory compounds curcumin or docosahexaenoic acid resulted in attenuation of microgliosis and partial correction of the retina pathology56,57.

A slight upregulation of LAMP1, LAMP2, CTSZ and CTSD was another early pathological feature of mutant retinas. Levels of all four lysosomal proteins progressively increased until the end stage of the disease at P240. In line with the immunohistochemical data, immunoblot analyses of retinas at P240 revealed that levels of LAMP1, LAMP2 and CTSZ were increased 1.3-, 2.6- and 2.8-fold, respectively when compared with control retinas. For the aspartic protease CTSD, we found a 2.1-fold increase for the precursor form and a 3.9-fold increase for the mature form. Significantly elevated levels of CTSD mRNA and CTSD protein were also observed in the brain of Ppt1 ko mice prior to the onset of neurological impairment58. Paradoxically, however, levels of the 31 kDa and 14 kDa CTSD fragments, which constitute enzymatically active CTSD after dimerization, were markedly decreased in PPT1-deficient lysosomes58. Impaired processing of CTSD in lysosomes correlated with an elevated pH and decreased levels of cathepsin B and cathepsin L. Evidence was presented that the increased levels of mature CTSD detected in immunoblots of total tissue brain homogenates comprised CTSD that was released from the cells and subsequently processed by a matrix metalloproteinase. Of note, extracellularly located CTSD was shown to be neurotoxic and might thus contribute to the pathogenesis of CLN1 disease, in addition to the paucity of CTSD enzymatic activity in PPT1-deficient lysosomes58.

Upregulation of lysosomal enzyme expression in response to transcription factor EB (TFEB) activation represents an adaptive mechanism in conditions of lysosomal dysfunction and starvation59. Under normal conditions, the lysosome-associated mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) phosphorylates TFEB, thereby retaining the transcription factor in the cytosol in an inactive state60. Upregulation of TFEB mRNA and protein, primarily in astrocytes and microglia, has been observed in the brain of CLN1-deficient mice58, and pharmacological inhibition of PPT1 activity by DQ661 has been shown to repress mTORC1 activity and to block autophagic flux61. Together, results implicate TFEB in both the elevated expression levels of lysosomal enzymes and the blockage of autophagic flux observed in the PPT1-deficient retina. We have recently found elevated levels of several lysosomal proteins also in retinas of a CLN637 and a CLN7 mouse model38. While the relevance of the marked upregulation of lysosomal protein biosynthesis for the progression of the retinal dystrophies is unknown, it might serve as a useful pathogenic marker for studies aimed at correcting lysosomal dysfunction in the Ppt1 ko retina as we have recently demonstrated in Ctsd ko mice after intravitreal injections of human pro-CTSD62.

At the morphological level, PPT1 dysfunction has been reported to result in a slight thinning of the outer nuclear layer and a moderate loss of photoreceptor cells late during the disease course31,32,34,36. In line with these findings, we found normal photoreceptor numbers in 112-day-old Ppt1 ko mice, but significantly reduced photoreceptor numbers in 240-day-old mutants. Analyses specifically of cones, which comprise only ~3% of all photoreceptors in the mouse retina63 revealed, however, that photoreceptor degeneration becomes evident already at P112, as indicated by a ~11% loss of cones. At P240, cones were markedly reduced by ~39%. In comparison and in agreement with other studies34,36, the number of all photoreceptor cells (i.e. cones and rods) at the end stage of the disease was decreased by ~20%, demonstrating that cones are more severely affected than rods. However, a significant decline in scotopic and photopic ERG amplitudes has been observed before the onset of photoreceptor loss in 2- and 3-month-old mutants, respectively. Similarly, another study found moderately decreased ERG responses in 4-month-old Ppt1 ko mice36. Early deterioration of retina function but a relatively late and moderate photoreceptor loss indicates that PPT1 dysfunction impairs photoreceptor function in addition to photoreceptor survival. Notably, it has recently been shown that PPT1 is localized in cilia, and that PPT1 deficiency affected the abundance levels and distribution of ciliary proteins in presymptomatic Ppt1 ko mice64. Furthermore, PPT1 deficiency resulted in a reduced number of ciliated cells and in the formation of abnormally long cilia. Together these data suggest that cilia abnormalities, the cause of several isolated and syndromic retinal dystrophies65–67, might contribute to the pathogenesis of CLN1 disease64.

Retinal ganglion cells comprise another cell type affected by PPT1 dysfunction32,35. Using antibodies to BRN-3A, an established marker to monitor ganglion cell degeneration68, we found normal RGC numbers in 112-day-old mutants. At P240, in comparison, analyses of retinal sections and flatmount preparations revealed a loss of RGCs by ~28% and ~20%. respectively. Another study has reported an earlier onset and more pronounced loss of RGCs35. The reasons for these discrepant findings are unknown given that the same CLN1 mouse model on the same genetic background was analyzed with similar methods in both studies.

PPT1 dysfunction additionally results in thinning of the inner nuclear layer32,36. One study has reported normal cell numbers in this layer in four-month-old animals, and a cell loss of ~26% in eight-month-old mutants36. However, no attempts were made to identify the affected cell types and to study the time course of their degeneration. Our results demonstrate a significant loss of SCGN-positive cone bipolar cells but normal numbers of PKCα-positive rod bipolar cells at P112. At the end stage of the disease at P240, numbers of both cone and rod bipolar cells were markedly reduced by 32% and 57%, respectively. Of note, elevated levels of SQSTM1/p62, a cargo-receptor that binds ubiquitin and LC3 and is required for autophagic degradation69, were restricted to the inner nuclear layer long before the onset and during the entire course of the retinal dystrophy. Furthermore, we observed an only minor co-localization of SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates with the lysosomal marker protein LAMP1, indicating mainly extralysosomal accumulation of SQSTM1/p62. Extralysosomal accumulation of SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates has also been observed in neurons of Cln2 ko mice70 and arylsulfatase G-deficient mice71, most likely as a result of lysosomal membrane permeability. Alternatively, accumulation of lysosomal storage material may impair the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes and thus the processing of autophagic material, resulting in accumulation of SQSTM1/p62-positive aggregates72. Increased levels of the autophagic markers SQSTM1/p62 and/or microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3-II (LC3-II) as pathological markers for impaired constitutive autophagy have also been reported in mouse models of various other NCLs, both in the brain41,73–75 and in the retina62,76,77.

The pronounced loss of bipolar cells is in line with the decreased b/a-amplitude ratio observed in ERG recordings from CLN1 mouse models32,36. Photopic and scotopic ERG recordings from CLN1 patients at relatively early stages of the disease also revealed a pronounced reduction of the b-wave amplitude with a relative preservation of the a-wave amplitude17. Interestingly, an involvement of the inner nuclear layer early during the disease course has also been demonstrated for other NCLs. For instance, a progressive decrease of the b/a amplitude ratio and/or a pronounced degeneration of inner nuclear layer neurons has been observed in a canine CLN2 model and CLN2 patients, and in a CLN3 mouse model and CLN3 patients16,78–82. Of interest in this context, a recent study has provided evidence that the progressive loss of photoreceptor cells in the nclf mouse model of CLN6 disease37,57 is caused by dysfunctions of bipolar cells83. While an AAV vector-mediated expression of CLN6 in photoreceptor cells had no beneficial effects on photoreceptor survival or function, photoreceptor cells were preserved and deterioration of retinal function was attenuated when CLN6 was expressed in bipolar cells, which in the nclf mouse start to degenerate only at late stages of the disease83. The combined data suggest that retinal interneurons are particularly vulnerable to lysosomal dysfunctions, at least in certain NCLs.

Enzyme replacement strategies through injection of the recombinant proteins, AAV vector-mediated gene transfer or cell transplantation represent a promising treatment strategy for NCLs caused by dysfunctions of soluble lysosomal enzymes (for reviews, see6,7,84–88). In support of this view, a phase I/II clinical trial has recently demonstrated that biweekly intracerebroventricular infusions of a recombinant human tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1) proenzyme (cerliponase alfa) resulted in significant attenuation of disease progression in CLN2 patients89. Preclinical work suggests, however, that retinal degeneration in these patients will likely proceed at a normal rate despite the successful brain-directed treatment. For instance, intraventricular injections of recombinant TPP1 or TPP1-encoding AAV vectors significantly delayed onset and progression of the brain pathology in a CLN2 canine model90,91, but had no therapeutic impact on the progression of retinal degeneration and visual deterioration92. Similarly, injections of a CTSD-encoding AAV vector into the cerebral hemispheres of neonatal Ctsd ko mice resulted in significant attenuation of neurodegeneration in the brain but not in the retina50. While the combined data indicate the urgent need to develop enzyme replacement strategies that specifically target the retina, only a few studies have analyzed the efficacy of this approach to treat retinal dystrophies34,62,93. In the Ppt1 ko mouse, intravitreal injections of an AAV2 vector encoding human PPT1 have been shown to partly preserve retina function34. However, loss of photoreceptor cells was not prevented despite the fact that levels of PPT1 enzyme activity in treated retinas exceeded by far those found in healthy control retinas. While the reasons for the limited effect on photoreceptor survival are unknown, separate analyses of rod and cone survival were not performed, and potential therapeutic effects on the other cell types affected in the Ppt1 ko retina were not evaluated34.

In summary, our data demonstrate early pathological alterations in the Ppt1 ko retina, and a progressive loss of various retinal cell types at relatively late stages of the disease. The detailed knowledge of the progression of the retinal dystrophy at the cellular and molecular level will aid future work aimed at developing treatments for vision loss in CLN1 disease.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Stefanie Schlichting and Sabine Helbing for excellent technical assistance, Konrad Sandhoff (University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany) for the Saposin D antibody, Fabio Morellini for help with the statistical analyses, Klaus Rüther for providing Ppt1 ko mice, and Wanda Jankowiak and Mahmoud Bassal for critically reading the manuscript. Work was supported by the Ernst und Berta Grimmke Stiftung (Düsseldorf, Germany) (to Y.A.) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 666918; BATCure) (to S.S.).

Author Contributions

Y.A., S.B., T.D., E.B., C.H. and S.S. performed and analyzed experiments. Y.A., S.B., S.S. and U.B. contributed to manuscript writing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. U.B. supervised the research.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50726-8.

References

- 1.Haltia M. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses: from past to present. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1762:850–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haltia M, Goebel HH. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses: a historical introduction. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1795–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams, R. E. In The Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (Batten Disease). (eds Mole, S. E., Williams, R. E. & Goebel, H. H.) 361–365 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- 4.Williams RE, Mole SE. New nomenclature and classification scheme for the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Neurology. 2012;79:183–191. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kollmann K, et al. Cell biology and function of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-related proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1866–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohlschütter A, Schulz A, Bartsch U, Storch S. Current and emerging treatment strategies for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. CNS drugs. 2019;33:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson TB, et al. Therapeutic landscape for Batten disease: current treatments and future prospects. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2019;15:161–178. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carcel-Trullols J, Kovacs AD, Pearce DA. Cell biology of the NCL proteins: What they do and don’t do. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1852:2242–2255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz A, Kohlschütter A, Mink J, Simonati A, Williams R. NCL diseases - clinical perspectives. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1801–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleat DE, Gedvilaite E, Zhang Y, Lobel P, Xing J. Analysis of large-scale whole exome sequencing data to determine the prevalence of genetically-distinct forms of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Gene. 2016;593:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santavuori P, Haltia M, Rapola J, Raitta C. Infantile type of so-called neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. 1. A clinical study of 15 patients. J Neurol Sci. 1973;18:257–267. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(73)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goebel HH. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses. Journal of child neurology. 1995;10:424–437. doi: 10.1177/088307389501000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vesa J, et al. Mutations in the palmitoyl protein thioesterase gene causing infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Nature. 1995;376:584–587. doi: 10.1038/376584a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chattopadhyay S, Pearce DA. Neural and extraneural expression of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses genes CLN1, CLN2, and CLN3: functional implications for CLN3. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2000;71:207–211. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dearborn JT, et al. Histochemical localization of palmitoyl protein thioesterase-1 activity. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2016;117:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weleber RG. The dystrophic retina in multisystem disorders: the electroretinogram in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Eye. 1998;12(Pt 3b):580–590. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weleber RG, et al. Electroretinographic and clinicopathologic correlations of retinal dysfunction in infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (infantile Batten disease) Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2004;83:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalanko A, Braulke T. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1793:697–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santavuori P. Neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses in childhood. Brain & development. 1988;10:80–83. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(88)80075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mole SE, Williams RE, Goebel HH. Correlations between genotype, ultrastructural morphology and clinical phenotype in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Neurogenetics. 2005;6:107–126. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chabrol B, Caillaud C, Minassian B. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2013;113:1701–1706. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59565-2.00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das AK, et al. Molecular genetics of palmitoyl-protein thioesterase deficiency in the U.S. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102:361–370. doi: 10.1172/JCI3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalviainen R, et al. Juvenile-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis with infantile CLN1 mutation and palmitoyl-protein thioesterase deficiency. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:369–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mole, S. E., Mitchison, H. M. & Munroe, P. B. Molecular basis of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses: mutations in CLN1, CLN2, CLN3, and CLN5. Human mutation14, 199–215, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:3<199::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-A (1999). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Ramadan H, et al. Adult neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis caused by deficiency in palmitoyl protein thioesterase 1. Neurology. 2007;68:387–388. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252825.85947.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Diggelen OP, et al. Adult neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis with palmitoyl-protein thioesterase deficiency: first adult-onset patients of a childhood disease. Annals of neurology. 2001;50:269–272. doi: 10.1002/ana.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzei R, et al. A novel mutation in the CLN1 gene in a patient with juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Journal of neurology. 2002;249:1398–1400. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0849-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metelitsina TI, Waggoner DJ, Grassi MA. Batten disease caused by a novel mutation in the PPT1Gene. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2016;10:211–213. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birch DG. Retinal degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: An overview. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 1999;66:356–366. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta P, et al. Disruption of PPT1 or PPT2 causes neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:13566–13571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251485198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jalanko A, et al. Mice with Ppt1Deltaex4 mutation replicate the INCL phenotype and show an inflammation-associated loss of interneurons. Neurobiology of disease. 2005;18:226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouchelion A, Zhang Z, Li Y, Qian H, Mukherjee AB. Mice homozygous for c.451C>T mutation in Cln1 gene recapitulate INCL phenotype. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2014;1:1006–1023. doi: 10.1002/acn3.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller JN, Kovacs AD, Pearce DA. The novel Cln1(R151X) mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (INCL) for testing nonsense suppression therapy. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24:185–196. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffey M, Macauley SL, Ogilvie JM, Sands MS. AAV2-mediated ocular gene therapy for infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2005;12:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groh J, et al. Immune cells perturb axons and impair neuronal survival in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2013;136:1083–1101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lei B, Tullis GE, Kirk MD, Zhang K, Katz ML. Ocular phenotype in a mouse gene knockout model for infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Journal of neuroscience research. 2006;84:1139–1149. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartsch U, et al. Apoptotic photoreceptor loss and altered expression of lysosomal proteins in the nclf mouse model of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013;54:6952–6959. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jankowiak W, et al. Retinal degeneration in mice deficient in the lysosomal membrane protein CLN7. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57:4989–4998. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruszewski K, Lüllmann-Rauch R, Dierks T, Bartsch U, Damme M. Degeneration of photoreceptor cells in arylsulfatase G-deficient mice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57:1120–1131. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flachsbarth K, et al. Neural stem cell-based intraocular administration of ciliary neurotrophic factor attenuates the loss of axotomized ganglion cells in adult mice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;55:7029–7039. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandenstein L, Schweizer M, Sedlacik J, Fiehler J, Storch S. Lysosomal dysfunction and impaired autophagy in a novel mouse model deficient for the lysosomal membrane protein Cln7. Human molecular genetics. 2016;25:777–791. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer DN, Barry LA, Tyynelä J, Cooper JD. NCL disease mechanisms. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1882–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radke J, Stenzel W, Goebel HH. Human NCL Neuropathology. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1852:2262–2266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson GW, Goebel HH, Simonati A. Human pathology in NCL. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1807–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyynelä J, Palmer DN, Baumann M, Haltia M. Storage of saposins A and D in infantile neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. FEBS letters. 1993;330:8–12. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80908-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmer DN. The relevance of the storage of subunit c of ATP synthase in different forms and models of Batten disease (NCLs) Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1852:2287–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galvin N, et al. A murine model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-ultrastructural evaluation of storage in the central nervous system and viscera. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2008;11:185–192. doi: 10.2350/07-03-0242.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oswald MJ, et al. Glial activation spreads from specific cerebral foci and precedes neurodegeneration in presymptomatic ovine neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (CLN6) Neurobiology of disease. 2005;20:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kay GW, Jay NP, Palmer DN. The specific loss of GnRH-positive neurons from the hypothalamus of sheep with CLN6 neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis occurs without glial activation and has only minor effects on reproduction. Neurobiology of disease. 2011;41:614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shevtsova Z, et al. CNS-expressed cathepsin D prevents lymphopenia in a murine model of congenital neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The American journal of pathology. 2010;177:271–279. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kielar C, et al. Successive neuron loss in the thalamus and cortex in a mouse model of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiology of disease. 2007;25:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macauley SL, et al. An anti-neuroinflammatory that targets dysregulated glia enhances the efficacy of CNS-directed gene therapy in murine infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:13077–13082. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2518-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macauley SL, Pekny M, Sands MS. The role of attenuated astrocyte activation in infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:15575–15585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Groh J, et al. Sialoadhesin promotes neuroinflammation-related disease progression in two mouse models of CLN disease. Glia. 2016;64:792–809. doi: 10.1002/glia.22962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Groh J, Berve K, Martini R. Fingolimod and Teriflunomide Attenuate Neurodegeneration in Mouse Models of Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2017;25:1889–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dannhausen Katharina, Möhle Christoph, Langmann Thomas. Immunomodulation with minocycline rescues retinal degeneration in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis mice highly susceptible to light damage. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2018;11(9):dmm033597. doi: 10.1242/dmm.033597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mirza M, et al. Progressive retinal degeneration and glial activation in the CLN6 (nclf) mouse model of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: a beneficial effect of DHA and curcumin supplementation. PloS one. 2013;8:e75963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandra G, et al. Cln1 gene disruption in mice reveals a common pathogenic link between two of the most lethal childhood neurodegenerative lysosomal storage disorders. Human molecular genetics. 2015;24:5416–5432. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Settembre C., Ballabio A. Lysosomal Adaptation: How the Lysosome Responds to External Cues. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2014;6(6):a016907–a016907. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Settembre C, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicastri MC, Rebecca VW, Amaravadi RK, Winkler JD. Dimeric quinacrines as chemical tools to identify PPT1, a new regulator of autophagy in cancer cells. Mol Cell Oncol. 2018;5:e1395504. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2017.1395504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marques, A. R. A. et al. Enzyme replacement therapy with recombinant pro-CTSD (cathepsin D) corrects defective proteolysis and autophagy in neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Autophagy, 10.1080/15548627.2019.1637200 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Jeon CJ, Strettoi E, Masland RH. The major cell populations of the mouse retina. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1998;18:8936–8946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08936.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Segal-Salto M, et al. Proteomics insights into infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (CLN1) point to the involvement of cilia pathology in the disease. Human molecular genetics. 2017;26:1678. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bujakowska Kinga M., Liu Qin, Pierce Eric A. Photoreceptor Cilia and Retinal Ciliopathies. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2017;9(10):a028274. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Estrada-Cuzcano A, Roepman R, Cremers FP, den Hollander AI, Mans DA. Non-syndromic retinal ciliopathies: translating gene discovery into therapy. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:R111–124. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.May-Simera H, Nagel-Wolfrum K, Wolfrum U. Cilia - The sensory antennae in the eye. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2017;60:144–180. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mead B, et al. Comparative evaluation of methods for estimating retinal ganglion cell loss in retinal sections and wholemounts. PloS one. 2014;9:e110612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pankiv S, et al. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Micsenyi MC, Sikora J, Stephney G, Dobrenis K, Walkley SU. Lysosomal membrane permeability stimulates protein aggregate formation in neurons of a lysosomal disease. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:10815–10827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0987-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kowalewski B, et al. Ataxia is the major neuropathological finding in arylsulfatase G-deficient mice: similarities and dissimilarities to Sanfilippo disease (mucopolysaccharidosis type III) Human molecular genetics. 2015;24:1856–1868. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Settembre C, et al. A block of autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17:119–129. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thelen M, et al. Disruption of the autophagy-lysosome pathway is involved in neuropathology of the nclf mouse model of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. PloS one. 2012;7:e35493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koike M, et al. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease) The American journal of pathology. 2005;167:1713–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tanaka Y, Chambers JK, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M. Possible involvement of lysosomal dysfunction in pathological changes of the brain in aged progranulin-deficient mice. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2014;2:78. doi: 10.1186/s40478-014-0078-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leinonen H, et al. Retinal degeneration in a mouse model of CLN5 disease is associated with compromised autophagy. Scientific reports. 2017;7:1597. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01716-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.von Eisenhart-Rothe P, et al. Failure of autophagy-lysosomal pathways in rod photoreceptors causes the early retinal degeneration phenotype observed in Cln6nclfmice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2018;59:5082–5097. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Katz ML, et al. Retinal pathology in a canine model of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2008;49:2686–2695. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katz ML, Johnson GS, Tullis GE, Lei B. Phenotypic characterization of a mouse model of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Neurobiology of disease. 2008;29:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Collins J, Holder GE, Herbert H, Adams GG. Batten disease: features to facilitate early diagnosis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2006;90:1119–1124. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.091637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Staropoli JF, et al. Large-scale phenotyping of an accurate genetic mouse model of JNCL identifies novel early pathology outside the central nervous system. PloS one. 2012;7:e38310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Volz C, Mirza M, Langmann T, Jägle H. Retinal function in aging homozygous Cln3 (Deltaex7/8) knock-in mice. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2014;801:495–501. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kleine Holthaus SM, et al. Prevention of photoreceptor cell loss in a Cln6nclf mouse model of batten disease requires CLN6 gene transfer to bipolar cells. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2018;26:1343–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Geraets RD, et al. Moving towards effective therapeutic strategies for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2016;11:40. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0414-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Neverman NJ, Best HL, Hofmann SL, Hughes SM. Experimental therapies in the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1852:2292–2300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sands MS. Considerations for the treatment of infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (infantile Batten disease) Journal of child neurology. 2013;28:1151–1158. doi: 10.1177/0883073813495960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mole SE, et al. Clinical challenges and future therapeutic approaches for neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The Lancet. Neurology. 2019;18:107–116. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hawkins-Salsbury JA, Cooper JD, Sands MS. Pathogenesis and therapies for infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (infantile CLN1 disease) Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1832:1906–1909. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schulz A, et al. Study of intraventricular cerliponase alfa for CLN2 disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;378:1898–1907. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Katz ML, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy attenuates disease progression in a canine model of late-infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (CLN2 disease) Journal of neuroscience research. 2014;92:1591–1598. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Katz ML, et al. AAV gene transfer delays disease onset in a TPP1-deficient canine model of the late infantile form of Batten disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:313ra180. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whiting RE, et al. Intracerebroventricular gene therapy that delays neurological disease progression is associated with selective preservation of retinal ganglion cells in a canine model of CLN2 disease. Experimental eye research. 2016;146:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tracy CJ, et al. Intravitreal implantation of TPP1-transduced stem cells delays retinal degeneration in canine CLN2 neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Experimental eye research. 2016;152:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Klein A, et al. Sphingolipid activator protein D (sap-D) stimulates the lysosomal degradation of ceramide in vivo. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1994;200:1440–1448. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.