Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI), developing as a component of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), leads to significant morbidity and mortality. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), produced in part by the neutrophil NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2), have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ALI. Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated the development of pulmonary inflammation in Nox2-deficient (gp91phox-/y) mice that was absent in WT mice in a murine model of SIRS. Given this finding, we hypothesized that Nox2 in a resident cell in the lung, specifically the alveolar macrophage, has an essential anti-inflammatory role. Using a murine model of SIRS, we examined whole-lung digests and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALf) from WT and gp91phox-/y mice. Both genotypes demonstrated neutrophil sequestration in the lung during SIRS, but neutrophil migration into the alveolar space was only present in the gp91phox-/y mice. Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α gene expression and protein secretion were higher in whole-lung digest from uninjected gp91phox-/y mice compared to the WT mice. Gene expression of MIP-1α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 was upregulated in alveolar macrophages obtained from gp91phox-/y mice at baseline compared with WT mice. Further, ex vivo analysis of alveolar macrophages, but not bone marrow-derived macrophages or peritoneal macrophages, demonstrated higher gene expression of MIP-1α and MIP-2. Moreover, isolated lung polymorphonuclear neutrophils migrate to BALf obtained from gp91phox-/y mice, further providing evidence of a cell-specific anti-inflammatory role for Nox2 in alveolar macrophages. We speculate that Nox2 represses the development of inflammatory lung injury by modulating chemokine expression by the alveolar macrophage.

KEY WORDS: acute lung injury, alveolar macrophage, ARDS, NADPH oxidase 2, Nox2

INTRODUCTION

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a serious complication of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). In the setting of SIRS, ALI and its most severe form, the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), carry a mortality rate estimated at up to 40% [1]. Although ARDS occurs following direct lung injury such as pneumonia, up to half of ARDS cases result from indirect inflammatory injury, as might occur in the setting of trauma or sepsis [2]. To date, the primary approach to caring for patients with ARDS is supportive care. Multiple pharmacologic therapies aimed at improving patient outcomes have been unsuccessful, indicating an overall knowledge gap about primary underlying mechanisms. While multiple factors contribute to the development of ALI, oxidative stress caused by or resulting from production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been identified as one potential mechanism [3–5]. Even so, clinical trials using broad-spectrum antioxidant therapies have not improved outcomes [6], suggesting that the role of oxidants is not well understood.

Though there are many potential sources for ROS production during lung injury, a predominant feature of ARDS is the infiltration of neutrophils to the alveolar space. Neutrophils produce ROS in part through the NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2), a multi-subunit enzyme complex in leukocytes. Although oxidative stress resulting from ROS production has been proposed as injurious and involved in the pathogenesis of ARDS [4], there is evidence suggesting the contrary. Segal et al. [7] showed increased pulmonary inflammation following direct lung injury in mice lacking functional Nox2. Further, mice that lack Nox2 develop spontaneous arthritis with high levels of pro-inflammatory mediators [8]. These studies suggest that Nox2-derived ROS also have an important role in the downregulation of local inflammatory processes.

Our laboratory was the first to demonstrate a protective role for Nox2 during sterile systemic inflammation. Using a murine model of SIRS, we found that mice lacking the catalytic subunit of Nox2 (gp91phox-/y) had increased early mortality and unresolved inflammation [9]. The primary phenotypic difference in the gp91phox-/y mice was the development of severe lung injury, characterized by hemorrhage, neutrophil infiltration, and thrombus formation, that was not present in WT mice. The early development of lung injury in the gp91phox-/y mice suggests that Nox2 in a resident cell in the lung is protective against the development of ALI during systemic inflammation.

In this study, we extend our previous findings and provide additional cell-specific evidence of the role of Nox2 in limiting pulmonary inflammation during sterile systemic inflammation using the zymosan-induced sterile inflammation model. Although both genotypes demonstrate early signs of systemic inflammation, mice lacking Nox2 rapidly develop lung injury that is not present in the WT mice. Additionally, we provide evidence that this difference is related to baseline differences in chemokine expression by the alveolar macrophage. Overall, our results demonstrate that Nox2 is essential in limiting inflammation in the lung following sterile systemic insults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Zymosan A from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) was resuspended in PBS, sonicated for 5 min, and then boiled for 10 min. Zymosan A was then centrifuged, rinsed, and boiled two additional times before a final resuspension in PBS and stored at − 20 °C. Alexa Fluor® 700 Ly6G was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). eFluor® 450 CD11b was purchased from Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA). RT-PCR primers were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). ELISA antibodies and streptavidin-HRP were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Collagenase D and DNase I were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals

All studies were approved and conducted under the oversight of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Age-matched (10–14 weeks) male C57BL/6J (WT) and gp91phox-deficient (B6.129S-Cybbtm1Din/J) mice were used in all experiments. Mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and kept in a barrier facility with free access to standard rodent chow and water.

Zymosan-Induced Generalized Inflammation

Sterile systemic inflammation was induced using the zymosan-induced generalized inflammation (ZIGI) model [10], in which mice received an intraperitoneal injection of zymosan (0.7 mg/g). We have previously demonstrated that saline-injected mice did not develop an inflammatory phenotype [9], and thus, non-injected mice were used as controls for all experiments. Mice were sacrificed at 1 h and 2 h post injection.

Assessment of Systemic Inflammation

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and blood was collected into an EDTA-containing tube from the submandibular vein. Complete blood counts (CBCs) were performed by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center animal resource center diagnostic lab using a ProCyte Dx analyzer (IDEXX Laboratories). Remaining blood was centrifuged at 2300×g for 5 min at 4 °C. Plasma was removed and stored at − 80 °C.

Plasma samples from non-injected and zymosan-injected mice were evaluated for cytokine content using a Bio-Plex Pro™ Mouse Cytokine 23-plex Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data was collected and analyzed on a Bio-Rad Bio-Plex (Luminex 200). Samples reported as out-of-range low were assigned the lowest detectable standard value.

Evaluation of Lung Injury

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed by serial intratracheal infusions of PBS (5 mL final volume) followed by gravity drainage. Recovered fluid was centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in PBS without calcium or magnesium. The total leukocyte number was determined by hemocytometer count. Cell differentials were obtained by counting 100 leukocytes in two random fields on cells obtained using a cytospin that were fixed and stained using a Hema 3 Stat Pack (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Following BAL, the pulmonary vasculature was perfused through the right ventricle with 5 mL of PBS. Lungs were removed, cut into small pieces with scissors, and subjected to digestion in digestion buffer (1 mg/mL collagenase D and 0.1 mg/mL DNase I in PBS) for 30 min at 37 °C with continuous shaking. In a subset of experiments, lungs were mechanically digested using a Miltenyi gentleMACS™ Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Homogenized lungs were passed through a 70-μm nylon filter, and the lung homogenate was centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C. The resultant supernatant was collected and stored at − 80 °C. The remaining red blood cells were lysed, and cells were fixed for flow cytometry using BD FACS lysis buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The cell count was determined using a hemocytometer.

Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 and Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1α ELISA

For quantification of chemokines, 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp microplates were coated with antibodies against macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) or monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in carbonate buffer (100 mM NaHCO3, 34 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.6) for 16 h at 22 °C. Wells were blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA and 5% sucrose for 1 h. Samples were thawed and spun at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C during the blocking step. Standards diluted in assay diluent (PBS with 0.1% BSA) and undiluted samples were loaded into duplicate wells and incubated for 2 h at 22 °C. Biotinylated antibody against the target chemokine was added and allowed to incubate for 2 h followed by streptavidin-HRP for 20 min. Finally, tetramethylbenzidine was added to the wells for 10–30 min for color development and 0.5 M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction. All incubations were performed at 22 °C, and wells were rinsed three times with wash buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) between each step. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured on a CLARIOstar Omega. Samples reported as out-of-range low were excluded.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were blocked with PBS containing 4% NGS and 2% nonfat dry milk on ice for 20 min. Cells were incubated with conjugated antibodies on ice for 1 h and washed before analysis.

All data acquisition was performed on a BD LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) in the Flow Cytometry Facility at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center with ≥ 10,000 events collected per analysis. Data was analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.0.08 (Treestar, Ashland, OR, USA).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol® according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of RNA was determined by absorbance at 260 nm/280 nm using the NanoDrop® ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was prepared using 1 μg RNA using the high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RT-PCR was performed using TaqMan™ primers for GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1), CCL2 (MCP-1; Mm00441242_m1), CCL3 (MIP-1α; Mm00441259_g1), CCL4 (MIP-1β; Mm00443111_m1), and CXCL2 (MIP-2; Mm00436450_m1) on an ABI Prism 7900 system (Applied Biosystems™; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in duplicate. The relative amount of RNA was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method. GAPDH was used as the reference gene.

Cell Culture

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were generated as described previously [11]. Briefly, both femurs were removed from uninjected mice and flushed with RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were plated in RPMI medium with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone™, Logan, UT, USA), 20% L929 cell-conditioned media, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. Following 7 days of growth at 37 °C with 5% CO2, 1 × 106 cells were placed in each well of a six-well culture dish. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, media were removed, cells were washed twice with RPMI medium, and fresh RPMI medium with 10% FBS was added. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for an additional time of 2 h, at which time media were collected and stored at − 80 °C. TRIzol was added directly to cells for RNA isolation.

Peritoneal macrophages were recovered by peritoneal lavage, and alveolar macrophages were collected via bronchoalveolar lavage. Cells were cultured in RPMI medium with 10% FBS. Mature macrophages were allowed to adhere to cell culture plates at 37 °C for 2 h, at which time media were removed and cells were washed twice with RPMI medium. Fresh RPMI medium with 10% FBS was added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C for an additional time of 2 h. Media were collected and used for quantification of MIP-1α and MCP-1. TRIzol was added directly to cells for RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis.

Neutrophil Migration

Neutrophil migration was measured in duplicate using 24-well Transwell® plates with a 3 μM pore diameter (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). Two hours following zymosan injection, BAL fluid was obtained and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C. Five hundred microliters of BAL supernatant was placed in the bottom well of the Transwell® plate.

Following lung digestion, lung polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) were isolated using an anti-Ly6G microbead kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Following magnetic selection, isolated lung PMNs were washed and resuspended in RPMI and were placed in the top well of the Transwell® plate. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. Migrated cells were counted using a hemocytometer, and percent migrated was calculated as the total cells migrated divided by the total lung PMN added to the top well.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.05) for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Results were considered statistically significant with a p value ≤ 0.05. Comparisons between groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. In some cases, direct comparisons between genotypes were made using unpaired Student’s t tests. In all graphs, *p ≤ 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p ≤ 0.001.

RESULTS

WT and gp91phox-/y Mice Exhibit Early Systemic Inflammation in Response to Zymosan

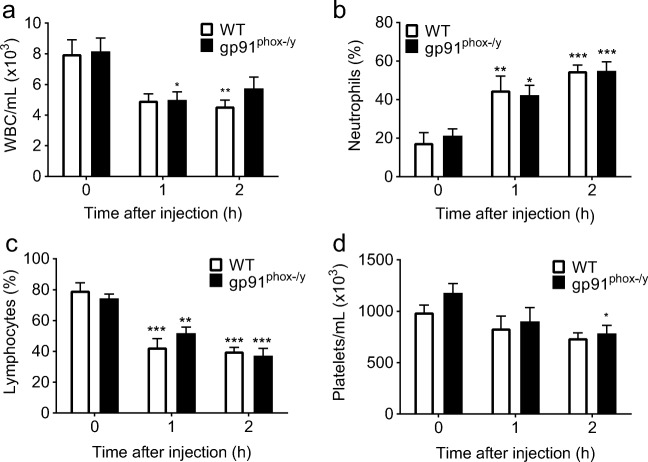

Given our previous data demonstrating that the gp91phox-/y mice have increased early mortality and develop severe lung injury [9], we investigated the onset of systemic inflammation using the ZIGI model [10]. Mice were scored for the presence of ruffled fur, lethargy, diarrhea, and conjunctivitis using a previously validated scoring system for rodents [10] at 1 h and 2 h post intraperitoneal zymosan injection. There were no significant differences in the inflammation score between genotypes at these early time points (data not shown). We have previously shown that both genotypes develop a systemic inflammatory response as evidenced by hypothermia, hypotension, and leukopenia by 6 h following intraperitoneal injection with zymosan [9]. In the current study, we found that both genotypes displayed an early decline in WBC count, with no differences between genotypes (Fig. 1a). There was an increase in the percentage of circulating neutrophils, with a decrease in the percentage of lymphocytes 1 h and 2 h after zymosan injection in both genotypes (Fig. 1b, c). The gp91phox-/y mice develop thrombocytopenia 2 h following zymosan injection, with no significant differences in platelet count between genotypes (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

Both genotypes exhibit alterations in circulating white blood cells following induction of sterile inflammation. WT and gp91phox-/y mice demonstrate a reduction in circulating white blood cells and increase in the percentage of circulating neutrophils within 1–2 h of intraperitoneal injection of zymosan (a, b). There is a decrease in the percentage of circulating lymphocytes in both genotypes within 1–2 h after injection (c), with only the gp91phox-/y mice developing decreased platelet counts at 2 h (d). Time 0 represents uninjected control mice. (N = 6–17 per time point from seven independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001 as compared to uninjected mice.

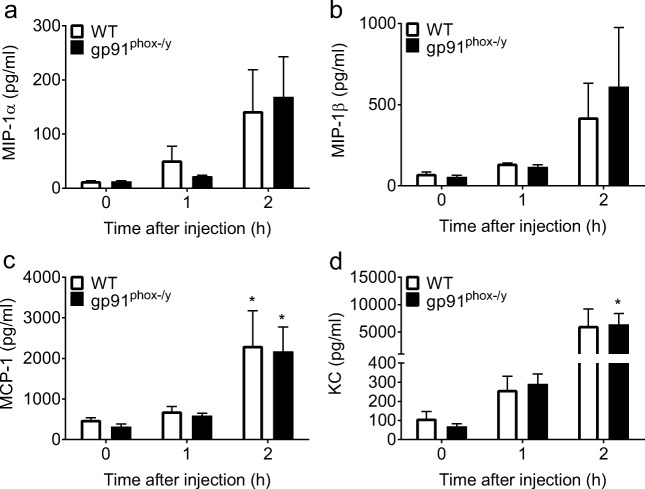

We further characterized the early systemic inflammatory response through the measurement of plasma chemokines and cytokines 1 h and 2 h following zymosan injection. Plasma levels of MCP-1 were elevated in both genotypes, with levels of KC elevated only in the gp91phox-/y mice 2 h following zymosan injection. There were no differences in the amount of MIP-1α, MIP-β, MCP-1, or KC in gp91phox-/y mice when compared to WT mice at any time point (Fig. 2). Taken together, our inflammation scoring, CBC data, and plasma cytokine/chemokine measurements are consistent with the conclusion that both genotypes develop early systemic inflammation following zymosan injection. Thus, the onset of lung injury in only the gp91phox-/y mice seems unlikely to be mediated by differences in the systemic inflammatory environment but rather is a local or tissue-specific event.

Fig. 2.

Plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines do not differ between genotypes. There are no significant differences in plasma levels of MIP-1α (a) or MIP-1β (b) following zymosan injection in either genotype. MCP-1 is increased in both genotypes 2 h after zymosan injection, with no significant difference between genotypes (c). Plasma levels of KC are increased in the gp91phox-/y mice 2 h after zymosan injection, with no significant differences between genotypes (d). Time 0 represents uninjected control mice. (N = 4–5 from four independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05 as compared to uninjected mice.

Enhanced PMN Response in the Lungs of gp91phox-/y Mice Following Induction of Sterile Inflammation

Our previously published work demonstrated a striking difference between genotypes in the development of lung injury, with the gp91phox-/y mice displaying neutrophil infiltration, hemorrhage, and thrombus formation, that was lacking in the WT mice. This distinction between genotypes was evident as early as 6 h and persisted over many weeks [9, 12]. We hypothesized that this lung injury resulted from the loss of inhibitory Nox2 signaling in a resident cell in the lung, and sought to explore the initial onset of lung injury 1 h and 2 h post zymosan injection.

To evaluate the role of Nox2 in PMN recruitment to the lung during systemic inflammation, we examined lung homogenates from uninjected mice and at 1 h and 2 h following intraperitoneal zymosan injection. On gross inspection at the time of euthanasia, we noted the development of microthrombi on the surface of the lungs 2 h following intraperitoneal zymosan injection in a significant percentage of gp91phox-/y mice (11/18; 61%), whereas this was not observed in WT mice (0/19; 0%) (Fig. 3). There was a significant increase in the percentage of neutrophils in the lung homogenates 1 and 2 h post injection in both genotypes (Fig. 4a–c), with no significant differences in total lung cell count between genotypes (Fig. 4d). Given that the lung homogenates were obtained following bronchoalveolar lavage and perfusion of the pulmonary vasculature, the neutrophils represent both marginated and interstitial neutrophils. We further examined the phenotype of this subgroup of neutrophils by examining the surface expression of the β2-integrin CD11b (Mac-1). CD11b is a well-described marker of neutrophil priming/activation status and a necessary protein for neutrophil migration [13]. PMNs in the lung homogenate displayed an increase in CD11b expression on the cell surface 2 h after injection in both genotypes, with significantly higher expression in the gp91phox-/y mice compared to the WT mice (Fig. 4e). Thus, even though both genotypes display increased neutrophil sequestration in the lung during systemic inflammation, the increase in CD11b expression 2 h following zymosan injection suggests that neutrophils from the gp91phox-/y mice are more activated when compared to the WT mice. Given this difference, we next examined expression and secretion of inflammatory chemokines in the lung.

Fig. 3.

gp91phox-/y mice develop microthrombi on the surface of the lung. Two hours following the induction of sterile inflammation, there is development of microthrombi on the surface of the lung in gp91phox-/y mice (b) that is not present in WT mice (a).

Fig. 4.

gp91phox-/y mice display increased neutrophil sequestration and activation in the lung. Representative dot plots demonstrate the percentage of lung PMNs following i.p. zymosan injection in WT and gp91phox-/y mice (a). Both WT and gp91phox-/y mice display sequestration of neutrophils within the lung 1 h after intraperitoneal injection of zymosan with further increase by 2 h when compared with uninjected control mice (b, c). There is no significant difference in the total cell count in lung homogenates between genotypes (d). Surface expression of CD11b is upregulated on neutrophils from the whole-lung digest of gp91phox-/y mice 2 h after injection when compared to the WT mice (e). (N = 7–18 from four independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05.

gp91phox-/y Mice Display Enhanced Gene Expression of Inflammatory Chemokines in the Lung

Based on the early evidence of neutrophil migration, we hypothesized that there would be increased levels of inflammatory chemokines in the lung. We examined the gene expression of the inflammatory chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 in lung homogenates. Unexpectedly, we found that the basal expression of MIP-1α is significantly higher in gp91phox-/y mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 5a), with no significant differences in gene expression of MCP-1, MIP-1β, or MIP-2 between genotypes (Fig. 5b–d). After finding evidence of a difference in baseline chemokine expression in the whole lung by RT-PCR, we measured MIP-1α and MCP-1 protein levels in the lung digest supernatant. Uninjected gp91phox-/y mice displayed markedly enhanced secretion of MIP-1α in the lung compared to WT mice, with a trend towards increased secretion of MCP-1 (Fig. 5e, f). As the lung homogenate contains a mixed cell population, it is difficult to determine which cell type is responsible for the increase in MIP-1α secretion. We hypothesized that this baseline difference was due to phenotypic differences in resident macrophages in gp91phox-/y mice, and therefore, we next examined the cells in the alveolar space.

Fig. 5.

gp91phox-/y mice have enhanced gene expression and protein secretion of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in whole-lung digests. There is higher gene expression of MIP-1α in unstimulated gp91phox-/y mice compared to WT mice (a), with no significant differences in the expression of MCP-1 (b), MIP-1β (c), or MIP-2 (d). (N = 4–11 from four independent experiments). Levels of MIP-1α and MCP-1 in the supernatant of the whole-lung digest were determined using ELISA in uninjected mice and 1 h and 2 h post injection. The gp91phox-/y mice have increased basal secretion of MIP-1α in the lung as compared to WT mice (e), with no significant differences in protein secretion of MCP-1 (f). (N = 3–10 from five independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

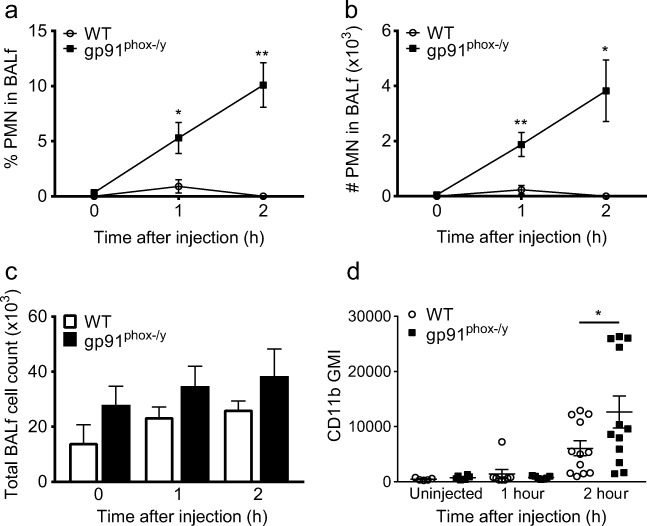

gp91phox-/y Mice Display Enhanced Neutrophil Infiltration to the Alveolar Space

Consistent with our previously published observations at 6–48 h [9], the gp91phox-/y mice displayed hemorrhagic bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALf) within 2 h of injection (7/17; 41%), whereas there was minimal hemorrhage seen in WT mice (1/20; 5%). Despite our finding that both genotypes had enhanced neutrophil trapping in the lung, only the gp91phox-/y mice displayed migration of these neutrophils into the alveolar space (Fig. 6a, b). Although there was a trend towards higher total cell counts in the BAL in the gp91phox-/y mice compared to the WT mice, this was not statistically significant (Fig. 6c). Similar to our findings in the whole-lung digest, PMNs from the alveolar space displayed a significantly higher expression of surface CD11b in the gp91phox-/y mice compared to the WT mice (Fig. 6d). These data suggest that Nox2 is protective against neutrophil migration to the alveolar space during systemic inflammation.

Fig. 6.

gp91phox-/y mice display neutrophil recruitment to the alveolar space. The gp91phox-/y mice display increased neutrophil infiltration into the alveolar space as measured in the BALf within 1 h and 2 h of zymosan injection when compared to the WT mice (a, b), with no significant difference in total BAL cell count (c). There is higher cell surface expression of CD11b on neutrophils from the BAL 2 h after injection when compared to WT mice (d) (N = 4–10 from five independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

gp91phox-/y Mice Display Enhanced Gene Expression of MIP-1α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 in Cells Isolated from BALf

The most remarkable difference between the gp91phox-/y mice and WT mice is the early recruitment of neutrophils to the alveolar space. We postulated that this recruitment is initiated by alveolar macrophages, and that there would be differences in inflammatory chemokine production by the alveolar macrophages in uninjected gp91phox-/y mice. Unlike the lung digest, which contains several different cell types, cells obtained from the alveolar space by BAL in uninjected mice are 99.3% ± 0.28% alveolar macrophages. Using RT-PCR to examine the gene expression of specific inflammatory chemokines in alveolar macrophages isolated from uninjected mice, we found increased mRNA expression of MIP-1α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 in gp91phox-/y mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 7a). Uninjected gp91phox-/y mice displayed markedly enhanced secretion of MIP-1α in the BALf compared to WT mice, with a persistent increase noted 1 h and 2 h following intraperitoneal zymosan injection (Fig. 7b). There was no significant difference in the secretion of MCP-1 (Fig. 7c). Although we hypothesized that this baseline difference was due to phenotypic differences in resident macrophages in gp91phox-/y mice, we recognized that levels of MIP-1α in the BALf may represent protein secreted from other cells, such as epithelial or endothelial cells. Therefore, we next examined isolated alveolar macrophages ex vivo.

Fig. 7.

gp91phox-/y mice display enhanced basal gene expression of inflammatory chemokines in cells isolated from the BALf. There is enhanced gene expression of MIP-1α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 in uninjected gp91phox-/y mice compared to WT mice, with a trend towards increased MIP-1β gene expression (a). (N = 3–15 from four independent experiments). In the BALf, the gp91phox-/y mice display increased protein secretion of MIP-1α at baseline and 1–2 h following intraperitoneal injection compared to WT mice (b), with no difference in the secretion of MCP-1 (c). (N = 6–17 from 10 to 11 independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 Gene Expression Is Enhanced in Alveolar Macrophages Isolated from gp91phox-/y Mice

Our results demonstrate differences in chemokine secretion in the lung and BALf of uninjected gp91phox-/y mice compared to WT mice. Given that the primary phenotypic difference is the development of lung injury in the gp91phox-/y mice that is lacking in the WT mice, we postulated that the increased chemokine secretion was a cell-specific finding in the alveolar macrophage. Similar to the results of our in vivo studies, alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice display enhanced gene expression of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 compared to WT mice, whereas there are no significant differences in chemokine expression in cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 8a–c). Isolated peritoneal macrophages from gp91phox-/y mice have increased the gene expression of MIP-1β, with no significant differences in MCP-1, MIP-1α, or MIP-2. Moreover, in this ex vivo analysis, there was increased protein secretion of MIP-1α by the alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice with no differences in the secretion of this chemokine by isolated peritoneal cells (Fig. 8d). These data suggest that the increase in chemokine secretion in the gp91phox-/y mice is a cell-specific event in the alveolar macrophage. As our model shows an increase in neutrophil recruitment to the alveolar space in the gp91phox-/y mice in vivo, we next sought to determine if neutrophil migration to BALf could be demonstrated ex vivo.

Fig. 8.

Alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice display enhanced gene expression of inflammatory chemokines. There is enhanced gene expression of MIP-1α (a), MIP-2 (b), and MIP-1β (c) in alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice when compared to WT mice. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice have enhanced gene expression of MIP-1β compared to WT mice. There is increased protein secretion of MIP-1α in alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice, with no difference in peritoneal macrophages (d). (N = 4–11 from a minimum of four independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

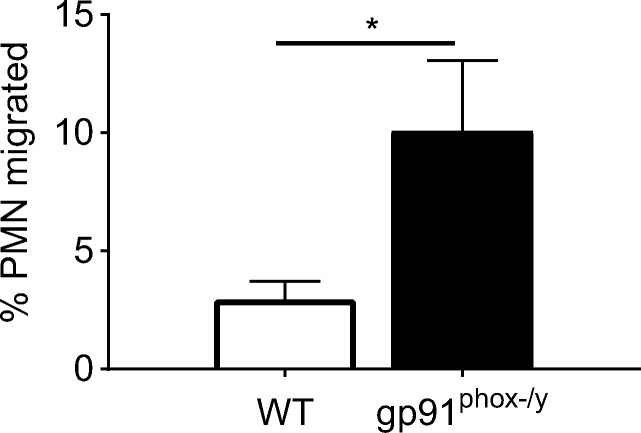

Isolated Lung PMN Migrate to BAL Fluid from gp91phox-/yEx Vivo

Given our findings that alveolar macrophages display increased secretion of inflammatory chemokines, we next sought to determine if the secretion of these chemokines was sufficient to facilitate neutrophil migration. We studied neutrophil migration ex vivo using BAL fluid collected from WT and gp91phox-/y mice 2 h following zymosan injection. We demonstrate that PMNs isolated from the lung of gp91phox-/y mice migrate to BAL fluid obtained from the gp91phox-/y mice, whereas there is a lower percentage of WT lung PMNs that migrate to WT BAL fluid (Fig. 9). Since cells have been removed from the BAL fluid, this demonstrates that the chemokine gradient present in the BAL fluid is sufficient to lead to increased neutrophil recruitment to the alveolar space. Considered in combination, these data suggest that Nox2 protects against the development of ALI by modulating chemokine secretion by alveolar macrophages.

Fig. 9.

Isolated lung PMNs migrate to the gp91phox-/y BALf. There is increased neutrophil migration to the gp91phox-/y BALf compared to WT BALf. (N = 5–6 from three independent experiments). *p ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

ARDS leads to significant morbidity and mortality, and there are currently no effective mechanistic-based therapies. Oxidative stress has been targeted in the past, but these therapies have not been effective in improving patient outcomes. Prior studies in our laboratory have demonstrated that there is an important anti-inflammatory role of Nox2-derived ROS in the lung. In the current study, we significantly expand our understanding of the mechanism by which Nox2-derived ROS serve to protect against ALI in sterile systemic inflammation. Our findings demonstrate that the development of lung injury is not a function of increased systemic inflammation, but rather an organ-specific inflammatory process in the gp91phox-/y mice. The novelty of the current study is the demonstration of enhanced basal gene expression of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MIP-2 in alveolar macrophages isolated from gp91phox-/y mice, suggesting that Nox2-derived ROS are required for the modulation of inflammatory chemokines in the lung and maintenance of immune homeostasis. While this baseline difference in inflammatory chemokine gene expression in alveolar macrophages in the gp91phox-/y mice does not lead to lung injury in unstimulated mice, it may lead to enhanced susceptibility to systemic inflammatory insults. The requirement for Nox2-derived ROS in repressing the secretion of chemokines in the lung may also partially explain the failure of broad-spectrum antioxidant therapies in ARDS.

Our finding of increased lung injury in mice lacking Nox2 is consistent with several prior studies demonstrating the development of ALI in Nox2-deficient mice. These include models of direct lung injury, such as intratracheal zymosan [7], LPS [7], and acid aspiration [14], and indirect lung injury, such as bacterial peritonitis [15]. In contrast with our findings, Imai et al. [16] demonstrated that mice lacking Nox2 were protected against the development of lung injury using pulmonary instillation of the H5N1 virus, and Menden et al. [17] found that Nox2-deficient mice had attenuated lung injury following intraperitoneal injection with LPS. In the study by Imai et al., mice lacking p47phox, a cytosolic subunit of Nox2, were protected against lung injury as determined by improved lung elastance, decreased pulmonary edema and decreased alveolar wall thickening during H5N1 infection [16]. No comment is made regarding the presence of neutrophil infiltration in the lung or BAL in their model. Patients with mutations in p47phox have a less severe phenotype when compared to patients with mutations in gp91phox due to residual ROS production [18], which may, in part, explain the attenuated lung injury in their study. Menden et al. [17] used intraperitoneal injection of LPS in neonatal mice and demonstrated attenuated neutrophil infiltration to the lung in Nox2-deficient mice. There are two key differences in this study when compared to our model of sterile systemic inflammation. First, this study utilized neonatal mice, which, in addition to having underdeveloped lungs, have been demonstrated to have an immature innate immune system [19]. Second, mice and humans are known to have different sensitivities to LPS, and therefore, this model may not be directly applicable to human disease. Interestingly, the study by Menden et al. was also in contrast to the study by Gao et al. [15], which used Escherichia coli peritonitis as their model. As LPS and E. coli both produce inflammation through Toll-like receptor 4, the mechanism behind the difference in responses in the two studies is unclear.

Neutrophil infiltration to the alveolar space is a key feature of ARDS [20–25]. Our data demonstrate that neutrophil sequestration occurs in both genotypes as early as 1 h following induction of sterile inflammation. This increase in neutrophil sequestration in the lung is consistent with prior studies using mice lacking Nox2 with induced bacterial peritonitis [15]. The accumulation of neutrophils in the pulmonary vascular bed has been previously demonstrated and may be beneficial in allowing for rapid response to infection or injury. In patients who develop ARDS, neutrophil sequestration in the pulmonary capillaries has been shown to be one of the earliest events [26], with the large number of neutrophils remaining in the pulmonary vascular bed resulting in a reduction in the peripheral neutrophil count [27, 28]. Although neutrophil sequestration is recognized as an early event in the development of ALI, the activation status of these neutrophils likely determines the extent of their extravascular migration and the degree of host damage. Consistent with previous studies in our laboratory [12], there was higher expression of CD11b on the surface of neutrophils sequestered in the lung in gp91phox-/y mice when compared to WT mice 2 h following zymosan injection. This difference in activation status may be a factor in the differential neutrophil migration to the alveolar space in gp91phox-/y mice despite the increase in neutrophil sequestration in both genotypes.

Alveolar macrophages have a central role in the regulation of neutrophil recruitment to the alveolar space. The production of cytokines and chemokines by alveolar macrophages has been shown to be instrumental in murine models of ischemia/reperfusion injury [29, 30], trauma-induced lung injury [31, 32], and LPS-induced lung injury [33]. Chemical depletion of alveolar macrophages was associated with attenuated neutrophil recruitment in LPS-induced lung injury [34, 35], further solidifying the importance of alveolar macrophages in modulating the immune response in the lung. Additionally, murine models of hemorrhagic shock [36, 37] and burn injury [38] have implicated early activation of alveolar macrophages in the development of lung injury.

The novelty of our data is the demonstration of a basal difference in the gene expression of inflammatory chemokines in alveolar macrophages isolated from the BALf of unstimulated gp91phox-/y mice in vivo and ex vivo. MIP-2, a CXC chemokine, and MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MCP-1, members of the CC family of chemokines, act primarily to recruit pro-inflammatory cells, including neutrophils [39–41]. MIP-2 has been demonstrated to regulate neutrophil recruitment to the lung in ventilator-induced lung injury [42]. MIP-1α has been demonstrated to promote lung inflammation in a model of LPS-induced direct lung injury [43], as well as during ventilator-induced lung injury [44]. Additionally, MIP-1α and MCP-1 have been demonstrated to participate in inflammatory cell recruitment into the lungs in the setting of a cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis model [45], though a definitive causative role was not determined in this study.

The regulation of MIP-1α and other inflammatory chemokine expression occurs through several pathways, including ERK 1/2, JNK, and p38 MAP kinases [46], as well as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, specifically STAT3 [47, 48]. Park et al. [49] demonstrated a requirement for ERK and JNK for the expression of MIP-1α and MCP-1 in response to LPS using cultured murine macrophages. STAT3 is recognized to play a key role in regulating inflammatory processes [50, 51] and is activated primarily through the Janus kinase (JAK) family of kinases via tyrosine phosphorylation [52]. Inhibition of the Jak2-STAT3 pathway blocked the upregulation of MIP-1α 6 h following LPS treatment in cultured murine macrophages [53]. The modification of cysteine residues and tyrosine phosphatases [54] by Nox2-derived ROS may alter MAPK and/or the Jak2/STAT3 pathway and thus regulate chemokine production. The exact molecular mechanisms regulating these processes are currently being investigated in our laboratory.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that Nox2 is essential in protecting against lung injury during systemic inflammation. The finding of a basal increase in the expression of MIP-1α, MCP-1, and MIP-2 in vivo as well as MIP-1β ex vivo in alveolar macrophages isolated from the gp91phox-/y mice suggests that Nox2 modulates the production of chemokines by alveolar macrophages, thereby regulating neutrophil infiltration in the lung under inflammatory conditions. Enhanced basal secretion of these inflammatory chemokines in the gp91phox-/y mice, while insufficient to cause significant lung injury under resting conditions, may make the lungs more susceptible to inflammation following an acute inflammatory stimulus. The interaction between activated circulating neutrophils and increased secretion of inflammatory chemokines from the alveolar macrophage leads to neutrophil infiltration in the alveolar space in gp91phox-/y mice. Strategies aimed at regulating chemokine production in the lung may be a future target for reducing lung injury-associated morbidity in the setting of systemic inflammation.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by award number K12HD068369 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the offical views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Matthay MA, Kallet RH. Prognostic value of pulmonary dead space in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care. 2011;15(5):185. doi: 10.1186/cc10346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(16):1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunnell E, Pacht ER. Oxidized glutathione is increased in the alveolar fluid of patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1993;148(5):1174–1178. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow CW, Herrera Abreu MT, Suzuki T, Downey GP. Oxidative stress and acute lung injury. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2003;29(4):427–431. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthay MA, Geiser T, Matalon S, Ischiropoulos H. Oxidant-mediated lung injury in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical Care Medicine. 1999;27(9):2028–2030. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard GR, Wheeler AP, Arons MM, Morris PE, Paz HL, Russell JA, Wright PE. A trial of antioxidants N-acetylcysteine and procysteine in ARDS. The Antioxidant in ARDS Study Group. Chest. 1997;112(1):164–172. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal BH, Han W, Bushey JJ, Joo M, Bhatti Z, Feminella J, Dennis CG, Vethanayagam RR, Yull FE, Capitano M, Wallace PK, Minderman H, Christman JW, Sporn MB, Chan J, Vinh DC, Holland SM, Romani LR, Gaffen SL, Freeman ML, Blackwell TS. NADPH oxidase limits innate immune responses in the lungs in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009631.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee K, Won HY, Bae MA, Hong JH, Hwang ES. Spontaneous and aging-dependent development of arthritis in NADPH oxidase 2 deficiency through altered differentiation of CD11b+ and Th/Treg cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(23):9548–9553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitmore LC, Hilkin BM, Goss KL, Wahle EM, Colaizy TT, Boggiatto PM, Varga SM, Miller FJ, Moreland JG. NOX2 protects against prolonged inflammation, lung injury, and mortality following systemic insults. Journal of Innate Immunity. 2013;5(6):565–580. doi: 10.1159/000347212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volman TJ, Hendriks T, Goris RJ. Zymosan-induced generalized inflammation: Experimental studies into mechanisms leading to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Shock. 2005;23(4):291–297. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000155350.95435.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmussen JA, Fletcher JR, Long ME, Allen LA, Jones BD. Characterization of Francisella tularensis Schu S4 mutants identified from a transposon library screened for O-antigen and capsule deficiencies. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6:338. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitmore LC, Goss KL, Newell EA, Hilkin BM, Hook JS, Moreland JG. NOX2 protects against progressive lung injury and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2014;307(1):L71–L82. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00054.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furie MB, Tancinco MC, Smith CW. Monoclonal antibodies to leukocyte integrins CD11a/CD18 and CD11b/CD18 or intercellular adhesion molecule-1 inhibit chemoattractant-stimulated neutrophil transendothelial migration in vitro. Blood. 1991;78(8):2089–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segal BH, Davidson BA, Hutson AD, Russo TA, Holm BA, Mullan B, Habitzruther M, Holland SM, Knight PR., 3rd Acid aspiration-induced lung inflammation and injury are exacerbated in NADPH oxidase-deficient mice. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2007;292(3):L760–L768. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00281.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao XP, Standiford TJ, Rahman A, Newstead M, Holland SM, Dinauer MC, Liu QH, Malik AB. Role of NADPH oxidase in the mechanism of lung neutrophil sequestration and microvessel injury induced by Gram-negative sepsis: Studies in p47phox-/- and gp91phox-/- mice. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(8):3974–3982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133(2):235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menden HL, Xia S, Mabry SM, Navarro A, Nyp MF, Sampath V. NADPH oxidase 2 regulates LPS-induced inflammation and alveolar remodeling in the developing lung. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2016;55:767–778. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0006OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhns DB, Alvord WG, Heller T, Feld JJ, Pike KM, Marciano BE, Uzel G, DeRavin SS, Priel DAL, Soule BP, Zarember KA, Malech HL, Holland SM, Gallin JI. Residual NADPH oxidase and survival in chronic granulomatous disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2600–2610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007097.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao J, Kim KD, Yang X, Auh S, Fu YX, Tang H. Hyper innate responses in neonates lead to increased morbidity and mortality after infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(21):7528–7533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800152105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pittet JF, Mackersie RC, Martin TR, Matthay MA. Biological markers of acute lung injury: Prognostic and pathogenetic significance. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;155(4):1187–1205. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang KY, Arcaroli JJ, Abraham E. Early alterations in neutrophil activation are associated with outcome in acute lung injury. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003;167(11):1567–1574. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-664OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warshawski FJ, Sibbald WJ, Driedger AA, Cheung H. Abnormal neutrophil-pulmonary interaction in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of pulmonary neutrophil kinetics in humans with in vivo 111indium neutrophil scintigraphy. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1986;133(5):797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinaldo JE, Borovetz H. Deterioration of oxygenation and abnormal lung microvascular permeability during resolution of leukopenia in patients with diffuse lung injury. The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1985;131(4):579–583. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.4.579.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azoulay E, Darmon M, Delclaux C, Fieux F, Bornstain C, Moreau D, Attalah H, Le Gall JR, Schlemmer B. Deterioration of previous acute lung injury during neutropenia recovery. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30(4):781–786. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg KP, Milberg JA, Martin TR, Maunder RJ, Cockrill BA, Hudson LD. Evolution of bronchoalveolar cell populations in the adult respiratory distress syndrome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;150(1):113–122. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WL, Downey GP. Neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2001;7(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao X, Dib M, Wang X, Widegren B, Andersson R. Influence of mast cells on the expression of adhesion molecules on circulating and migrating leukocytes in acute pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Lung. 2005;183(4):253–264. doi: 10.1007/s00408-004-2538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou X, Dai Q, Huang X. Neutrophils in acute lung injury. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2278–2283. doi: 10.2741/4051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii M, Suzuki Y, Takeshita K, Miyao N, Kudo H, Hiraoka R, Nishio K, Sato N, Naoki K, Aoki T, Yamaguchi K. Inhibition of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity improves ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat lungs. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(4):2569–2577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naidu BV, Krishnadasan B, Farivar AS, Woolley SM, Thomas R, Van Rooijen N, Verrier ED, Mulligan MS. Early activation of the alveolar macrophage is critical to the development of lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126(1):200–207. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seitz DH, Niesler U, Palmer A, Sulger M, Braumuller ST, Perl M, Gebhard F, Knoferl MW. Blunt chest trauma induces mediator-dependent monocyte migration to the lung. Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38(9):1852–1859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8ad10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoth JJ, Wells JD, Hiltbold EM, McCall CE, Yoza BK. Mechanism of neutrophil recruitment to the lung after pulmonary contusion. Shock. 2011;35(6):604–609. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182144a50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koay MA, Gao X, Washington MK, Parman KS, Sadikot RT, Blackwell TS, Christman JW. Macrophages are necessary for maximal nuclear factor-kappa B activation in response to endotoxin. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2002;26(5):572–578. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.4748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berg JT, Lee ST, Thepen T, Lee CY, Tsan MF. Depletion of alveolar macrophages by liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1993;74(6):2812–2819. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang G, White JE, Lumb PD, Lawrence DA, Tsan MF. Role of endogenous cytokines in endotoxin- and interleukin-1-induced pulmonary inflammatory response and oxygen tolerance. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1995;12(3):339–344. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.3.7873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powers KA, Woo J, Khadaroo RG, Papia G, Kapus A, Rotstein OD. Hypertonic resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock upregulates the anti-inflammatory response by alveolar macrophages. Surgery. 2003;134(2):312–318. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan J, Kapus A, Li YH, Rizoli S, Marshall JC, Rotstein OD. Priming for enhanced alveolar fibrin deposition after hemorrhagic shock: Role of tumor necrosis factor. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2000;22(4):412–421. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.4.3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright MJ, Murphy JT. Smoke inhalation enhances early alveolar leukocyte responsiveness to endotoxin. The Journal of Trauma. 2005;59(1):64–70. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000171588.25618.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW, Greenberger MJ, Danforth JM, Kunkel RG, Strieter RM. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha mediates lung leukocyte recruitment, lung capillary leak, and early mortality in murine endotoxemia. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(3):1515–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonecchi R, Polentarutti N, Luini W, Borsatti A, Bernasconi S, Locati M, Power C, et al. Up-regulation of CCR1 and CCR3 and induction of chemotaxis to CC chemokines by IFN-gamma in human neutrophils. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(1):474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson, T.S., and K. Ley. 2002. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in leukocyte trafficking. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 283 (1): R7–R28. 10.1152/ajpregu.00738.2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Londhe V, Xue YY, Li K, Phillips RJ, Strieter RM. Critical role for CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands during the pathogenesis of ventilator-induced lung injury. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(11):1703–1716. doi: 10.1172/JCI15849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quintero PA, Knolle MD, Cala LF, Zhuang Y, Owen CA. Matrix metalloproteinase-8 inactivates macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha to reduce acute lung inflammation and injury in mice. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(3):1575–1588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blazquez-Prieto J, Lopez-Alonso I, Amado-Rodriguez L, Batalla-Solis E, Gonzalez-Lopez A, Albaiceta GM. Exposure to mechanical ventilation promotes tolerance to ventilator-induced lung injury by Ccl3 downregulation. American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2015;309(8):L847–L856. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00193.2015.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Speyer CL, Gao H, Rancilio NJ, Neff TA, Huffnagle GB, Sarma JV, Ward PA. Novel chemokine responsiveness and mobilization of neutrophils during sepsis. The American Journal of Pathology. 2004;165(6):2187–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63268-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wuyts WA, Vanaudenaerde BM, Dupont LJ, Demedts MG, Verleden GM. Involvement of p38 MAPK, JNK, p42/p44 ERK and NF-kappaB in IL-1beta-induced chemokine release in human airway smooth muscle cells. Respiratory Medicine. 2003;97(7):811–817. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(03)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deverman BE, Patterson PH. Cytokines and CNS development. Neuron. 2009;64(1):61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: A leading role for STAT3. Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2009;9(11):798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park OJ, Cho MK, Yun CH, Han SH. Lipopolysaccharide of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans induces the expression of chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, and IP-10 via similar but distinct signaling pathways in murine macrophages. Immunobiology. 2015;220(9):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, King KL, Sheehan KCF, Yin L, Pennica D, Johnson EM, Jr, Schreiber RD. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93(3):373–383. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Forster I, Akira S. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bourgeais J, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Gouilleux F. Oxidative metabolism in cancer: A STAT affair? JAKSTAT. 2013;2(4):e25764. doi: 10.4161/jkst.25764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiguchi N, Saika F, Kobayashi Y, Ko MC, Kishioka S. TC-2559, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, suppresses the expression of CCL3 and IL-1beta through STAT3 inhibition in cultured murine macrophages. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2015;128(2):83–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon AR, Rai U, Fanburg BL, Cochran BH. Activation of the JAK-STAT pathway by reactive oxygen species. The American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):C1640–C1652. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.6.C1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]