Abstract

The Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative (HAPPI) is a multisectoral collaboration that aims to increase use of recommended cancer screening and other clinical preventive services (CPS) among underserved African American and Latino adults aged 50 and older in South Los Angeles. HAPPI uses the principles of the evidence-based model Sickness Prevention Achieved through Regional Collaboration to increase capacity for the delivery of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening, as well as influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, and cholesterol screening. This article describes HAPPI’s collaborative efforts to enhance local capacity by training personnel from community health centers (CHCs) and community-based organizations (CBOs), implementing a small grants program, and forming a community advisory council. HAPPI demonstrates that existing resources in the region can be successfully linked and leveraged to increase awareness and receipt of CPS. Five CHCs expanded quality improvement efforts and eight CBOs reached 2,730 older African Americans and Latinos through locally tailored educational programs that encouraged community–clinic linkages. A community council assumed leadership roles to ensure HAPPI sustainability. The lessons learned from these collective efforts hold promise for increasing awareness and fostering the use of CPS by older adults in underserved communities.

Keywords: Community-based partnerships, Health promotion, Disease prevention, Community–clinic linkages, Capacity building, Immunizations

By 2030, more than one-quarter of the U.S. population, about 81 million people, will have one or more chronic disease for which the cost of care is expected to approach $4.2 trillion (Bodenheimer, Chen, & Bennett, 2009; Wu & Green, 2000). Currently, 84% of health care spending is allocated to people with a chronic illness whereas less than 3% is spent on prevention, despite evidence that much of the disease, disability, and death associated with chronic conditions are preventable (Anderson, 2012; Multack, 2013; Satcher, 2006).

Clinical preventive services (CPS), such as breast and colorectal cancer screening, can help detect disease, delay their onset, or identify them while they are still most treatable. CPS are recommended for all older persons, not just those with particular diagnoses, so increasing their uptake holds value for the entire older adult population. Several national bodies of experts, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, and the Task Force for Community Preventive Services, have agreed on a recommended array of preventive services and on effective ways to increase their use (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2018). In the absence of these preventive measures, older adults are at increased risk of disability, disease, and premature death.

Yet the use of evidence-based CPS is far below recommended levels and national goals. Healthy People 2020 includes a goal of increasing the proportion of people 65 years of age and older who are up to date with a core set of CPS, which includes colorectal cancer screening, mammography screening (for women), and influenza and pneumococcal immunizations (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Many older adults are not receiving the full set of recommended CPS and utilization is particularly low among members of racial and ethnic minority groups (Koh, Piotrowski, Kumanyika, & Fielding, 2011; National Prevention Council, 2011; Shenson et al., 2012). Indeed, there are noted racial and ethnic disparities in the uptake of specific CPS. In 2015, 53% of Hispanics, 48% of Asians, and 41% of Blacks had not received recommended colorectal cancer screening as compared with 36% of Whites. American Indian or Alaska Native (43%) and other Asian (43%) women were among the least likely to have received a mammogram as compared to Black (26%), Hispanic (28%), and White (28%) women (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016; White et al., 2017). Furthermore, there are a host of additional recommended services not included in the core set of CPS put forth by Healthy People 2020 that may reduce cancer risk among older adults (e.g., counseling for smoking cessation and obesity screening and counseling).

Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative

The Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative (HAPPI) is a regional collaboration that promotes awareness and use of CPS by the 50 years or older population in an underserved area of Los Angeles County in California. HAPPI comprises local community-based organizations (CBOs), a coalition of community health centers (CHCs), aging and public health agencies serving the City and County of Los Angeles, and an interdisciplinary research team at a large public university. This article describes the early phases of an ongoing project, including collaborative and capacity-building activities that HAPPI has implemented to encourage community–clinic linkages and increase the community-wide delivery of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening, influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, and cholesterol screening to underserved African American and Latino older adults.

Barriers to the Use of CPS by Older Racial and Ethnic Minorities

The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act removed financial barriers to the uptake of CPS by requiring health plans to cover certain services and eliminate cost sharing and deductibles (Fox & Shaw, 2015). Yet a number of factors that may deter older adults from getting recommended preventive health services remain (Multack, 2013; Ramos, Spencer, Shah, Palmer, Forsberg, & Devers, 2014). At the individual level, a lack of knowledge or understanding about the appropriate use of CPS may lead consumers to either overutilize or underutilize recommended services (Lantz, Evans, Mead, Alvarez, & Stewart, 2016). Particularly among racial and ethnic minority group members, there is often fear and distrust of the traditional medical establishment in the United States, particularly in light of a history of ethical breaches in clinical practice and public health research (Reverby, 2012).

Safety net providers, such as CHCs, are often challenged by a dearth of available resources, including adequate staffing, and inefficient referral processes, some of which are related to the interoperability of electronic health records (Ryan, Doty, Abrams, & Riley, 2014). Social determinants of health, such as living in poverty, also have implications for access to preventive care. Data from the 2011–2012 National Health Interview Survey revealed that persons with higher income were more likely to have received preventive services than persons with lower income for eight of nine services (Fox & Shaw, 2014). Health equity is compromised when people are poor and do not have the time or the resources to engage in preventive care, especially when basic needs for food and shelter have not been met (Braveman, Egerter, & Williams, 2011).

These data point to the need to increase awareness and appropriate use of CPS and to emphasize efforts that are tailored to the circumstances of underserved racial and ethnic minorities, sensitive to historical experiences, and build on community strengths such as social networks, religious and community institutions, and traditional knowledge (Levy-Storms & Wallace, 2003).

Fostering Community–Clinic Linkages

Although practices to promote the use of CPS exist, relatively few include explicit linkages between clinic and community-based settings (Frank, Kietzman, & Wallace, 2014; Kietzman, Wallace, Bravo, Sadegh-Nobari, & Satter, 2012). Evidence-based practices that deliver CPS typically occur in clinical settings and are delivered by licensed medical personnel. Although aging services providers have long been engaged in health promotion and disease prevention activities, these efforts have largely focused on individual health behaviors that are addressed outside of clinical settings through physical activity or chronic disease self-management programs (Administration for Community Living).

Effective strategies for the promotion and delivery of CPS may require cooperation and collaboration between sectors that have not been traditionally financed or administered in the same way. These types of collaborations require extra effort as one sector needs to learn the operations of the other and find points of intersection that are beneficial to both. One very important but underutilized strategy is community-based prevention, supported by policies and programs that are designed to reach people where they work, live, shop, and play (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2018; Frank et al., 2014; Kietzman et al., 2012). Community programs can promote CPS by addressing barriers such as the lack of transportation or child care, and by conducting outreach through patient navigation programs that are locally tailored and culturally responsive.

Academic institutions can support community-based prevention efforts by providing expertise in program evaluation and applying the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR) to bridge the divide between academia, local government agencies, health care delivery systems, community organizations, and community members. CBPR aims to equitably engage all entities in the research process, building on existing strengths and resources, forging collaborative partnerships, and disseminating knowledge to all participants (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998).

HAPPI: A Model for Regional Collaboration

HAPPI advances a collaborative and community-based effort to increase use of a core set of “high-value” CPS (Sanchez, 2007) among African American and Latino adults aged 50 and older in South Los Angeles. The priority population includes older adults residing in Los Angeles County Service Planning Area 6 (SPA-6), a historically underserved region of about 750,000 people. In 2011, 48% of SPA-6 residents aged 50–64 years were African American and 42% were Latino; among those aged 65 and older, 64% were African American and 28% were Latino. More than half of the older adult population in SPA-6 lived in households with incomes less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Level. They report low rates of CPS use, including 42% who were not up to date with colon cancer screening, 56% who had not received a flu vaccine in the past year, and 15% of women aged 50–74 years not having a mammogram in the past 2 years (California Health Interview Survey 2011–2012).

HAPPI uses the principles of the evidence-based model Sickness Prevention Achieved through Regional Collaboration (SPARC) to specifically focus on increasing the community-wide delivery of influenza and pneumococcal immunizations, breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening, and cholesterol screening. SPARC provides a practical framework that advances access to and delivery of CPS through the implementation of collaborative strategies and convenient delivery mechanisms. Each collaborating partner identifies and assumes a complementary leadership role to facilitate increased use of CPS (Shenson, Benson, & Harris, 2008).

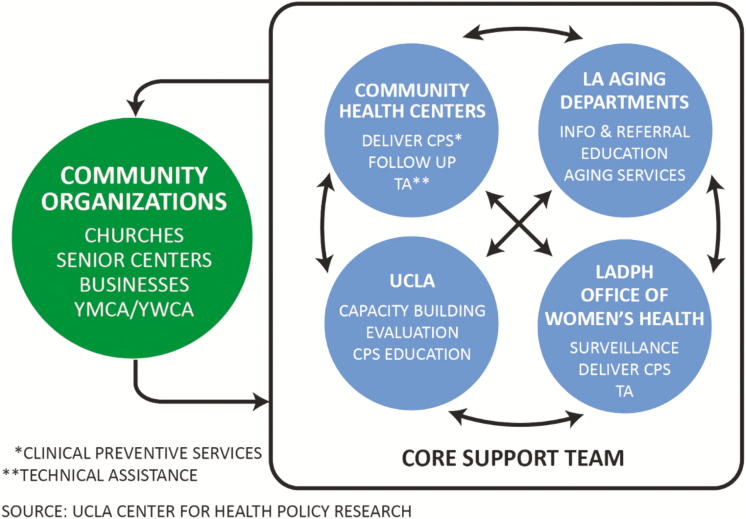

A strategic action governance model, Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP), was applied to advance the work of the collaborative (National Association of City and County Health Officials). MAPP uses a core support team (CST) representing key sectors providing services and resources to the priority population. A key member of HAPPI’s CST, the Southside Coalition of Community Health Centers, has a network of more than 35 community- and school-based health clinics with strong ties to local organizations. Other members include the Los Angeles County and City Departments of Aging, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, and the Office of Women’s Health (a unit within the Public Health Department; Figure 1). The CST provided expertise, access to information and resources, and identified more than 40 diverse community organizations to assume leadership roles to promote and increase CPS utilization through their respective networks.

Figure 1.

Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative (HAPPI) Core Support Team.

Although the CST provided an important starting point, it was essential to extend the collaborative network further into the community. Of the 40 community organizations identified by the CST, 34 convened to learn more about HAPPI at the Martin Luther King Health Education Center (MLK Health Education Center), a trusted and major hub for CBOs engaged in community health promotion efforts in South Los Angeles. Organizational leaders were motivated to attend the meetings at MLK Health Education Center by an invitation extended from the SPA-6 Area Health Office, a trusted public organization with established ties to the community. Public health and clinical research practitioners increasingly recognize the importance of trust as a significant influence in community response to interventions (Ward, 2017).

Attending CBOs, representing faith-based, community services, housing, worksite and labor, social justice, and major volunteer organizations, agreed to assume leadership roles to promote and increase CPS utilization through their network of partners. The resulting Community Council comprises diverse organizations such as the Girls Club of Los Angeles, Worksite Wellness, Men’s Cancer Network, New Visions Christian Fellowship Church, Alzheimer’s Association, and others including community clinics and organizations represented on the CST.

Support for HAPPI came from a combination of grant funds and in-kind contributions. Funding to support part-time project staff at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and at the Southside Coalition of Community Health Centers, along with monies dedicated to clinic and community training participants and small pilot grants for community organizations, was provided by the U.S. DHHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Mobilization for Health: National Prevention Partnership Awards Program (NPPA) (U.S. DHHS Grant No. 1 PAWOS000015-01-00). A total of $300,000 was regranted to community organizations over the 3-year term of the project. UCLA supported part-time staff to lead project management, coordination, and evaluation activities. The Southside Coalition received funding to support coalition staff coordinators and stipends of $3,000 each for the participation of eight Southside health centers in CPS in-service training. Stipends of $250 each were given to community representatives to complete the Healthy Aging and CPS training and conduct community workshops. Small pilot grants of $10,000–$20,000 were awarded to eight community organizations to implement CPS programs in partnership with CHCs.

Significant in-kind contributions came from the CST, state agencies, and participating CHCs and CBOs. For example, the Department of Public Health provided Continuing Medical Education credits to CHC staff participating in CPS in-service training. The Department of Public Health, Department of Aging, and Office of Women’s Health provided expert speakers and educational materials for clinic and community training. Additional training and technical assistance were provided by the California Every Woman Counts program that supports free mammography and cervical cancer screening as well as training of clinic staff. The Department of Aging, Southside Coalition, and a diverse set of community entities (e.g., churches, utility companies, public housing sites, shopping centers) hosted HAPPI grantee activities on an in-kind basis.

Building Community Capacity

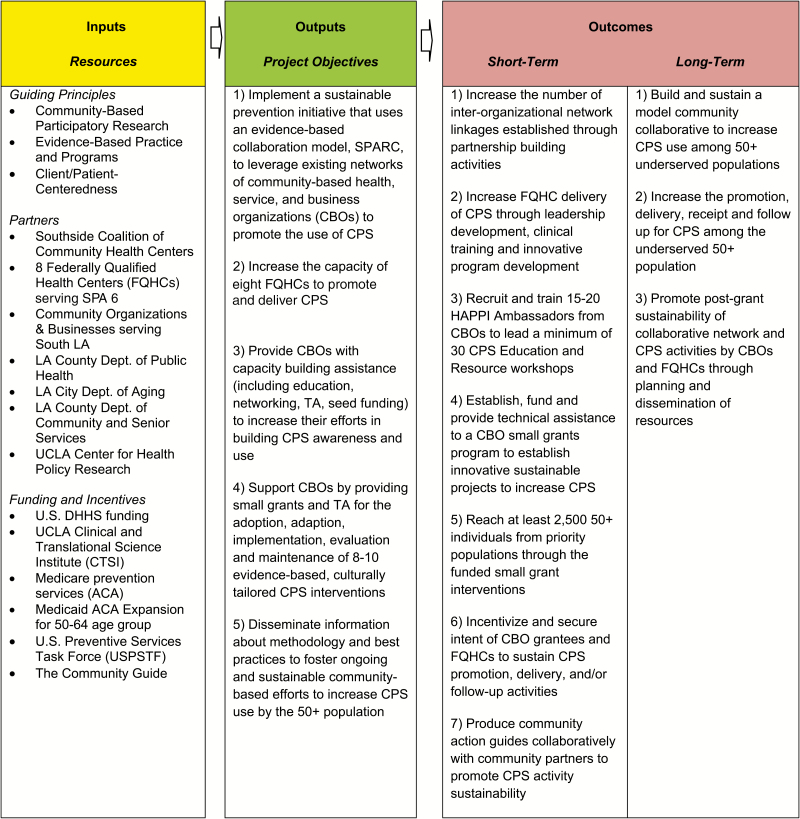

HAPPI engaged CHCs and CBOs in several capacity-building activities to advance the community’s role in increasing CPS use among older adults. These activities are briefly summarized later. Figure 2 provides a graphic representation of a logic model that describes the major components of HAPPI. All data collection methods and study protocols were approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB 15-000368).

Figure 2.

Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative (HAPPI): A logic model.

Community Health Centers

HAPPI staff and CST members provided in-service training and technical assistance to facilitate CHC quality improvement activities. The content of these training sessions was informed by a multidisciplinary competency framework developed by the Partnership for Health in Aging (2010) and further refined using findings from earlier CHC capacity-assessment activities (Bravo, Kietzman, Toy, Duru, & Wallace, 2019). Key learning objectives included familiarizing participants with unique health conditions for adults aged 50 years and older and providing evidence-based recommendations for CPS delivery to this population. The training sessions also introduced the idea of partnering with CBOs to address the preventive health needs of older adults both within and outside of their clinic walls. This latter discussion set the stage for future efforts to align each CHC with one or two specific CBOs, fostering community–clinic linkages and improving CPS delivery.

Community-Based Organizations

HAPPI Ambassadors

In consultation with the CST, the UCLA team developed a 12-hr curriculum and applied a train-the-trainer model successfully used in previous community capacity-building programs (Carroll-Scott, Toy, Wyn, Zane, & Wallace, 2012). Learning objectives include the following: (a) the importance of CPS to healthy aging, (b) screening guidelines and how to communicate guidelines to priority populations, (c) the role of evidence-based community interventions to improve access to CPS, and (d) how to partner with clinics to promote CPS (see Bravo et al., 2019, for more information about HAPPI Ambassador training). Organizations that completed the training and conducted a workshop were eligible to apply for a HAPPI Community Small Grant.

HAPPI Small Grants Program

The Community Council worked with the CST to design and administer a competitive Request For Proposal process to award small grants of $10,000–$20,000 to local CBOs. Those awarded grants engaged in a range of CPS-related activities, including outreach and education via one-on-one sessions, small groups, and train-the-trainer workshops; dissemination of written materials through existing communication channels and tabling at health fairs; motivational appeals through podcasts and faith-based presentations and testimonials; referrals and linkages to source of health care; and direct delivery of CPS.

Most grantees developed projects that combined at least two CPS. Some paired CPS education and referral with other ongoing health promotion activities. Primary cancer prevention behavioral modifications recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force such as tobacco cessation counseling and healthy diet classes were integrated in some grantee activities. For example, Esperanza Housing Corporation, a HAPPI grantee, received Freedom From Smoking certification from the American Lung Association to provide tobacco cessation counseling for residents in St. John’s CHC service area. Others expanded organizational work that previously focused on children or youth to begin to address the needs of older adult populations. For example, although the Girls Club of Los Angeles had already engaged older adults as volunteer foster grandparents, HAPPI now provided an opportunity specific to their needs and beneficial to their preventive health practices.

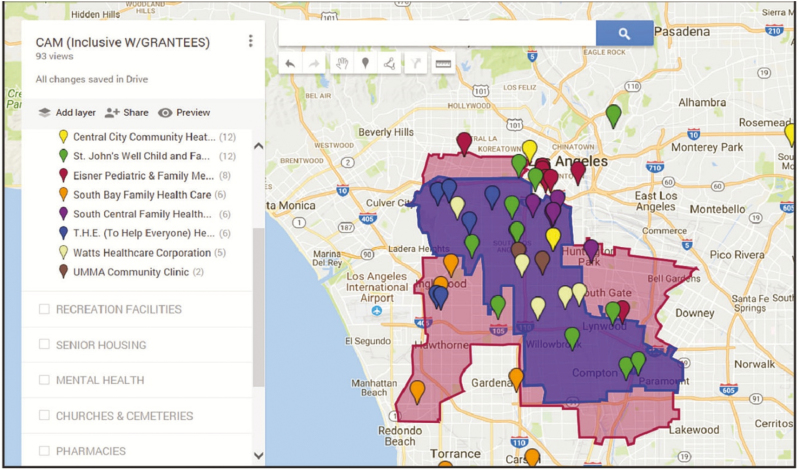

HAPPI Community Asset Maps

To further support these collaborative activities, a community asset map was developed, providing a common tool for resource identification and access that was used across all capacity assessment and capacity-building activities. Using Google mapping software, a comprehensive database was developed by the UCLA research team that includes all HAPPI partners (i.e., CHCs, CBOs, members of the CST and Community Council) and hundreds of additional community resources, including both aging-specific resources (e.g., senior housing, senior centers, and nutrition sites) and more general resources important to the broader population (e.g., food banks, parks and recreation departments, public libraries, shelters and services for homeless, mental health services). See Figure 3 for an example of a customized HAPPI community asset map.

Figure 3.

Healthy Aging Partnerships in Prevention Initiative (HAPPI): Community Asset Map.

Tailored to local geography, the maps are searchable by zip code, allowing users to identify and facilitate access to resources and referrals in proximity to the CHC, CBO, or community member’s place of residence. The maps were integrated into the CHC and CBO training and provided as a resource to all HAPPI partners.

Lessons Learned

The early implementation of HAPPI offers an example of “community gerontology”—an approach that encourages the active participation of gerontologists in change processes that extend beyond research activities to promote the integration of policy, practice, and research on communities and aging (Greenfield, Black, Buffel, & Yeh, 2018). Many lessons were learned through the formative efforts and processes HAPPI used to increase utilization of CPS among older adults in South Los Angeles.

Prepare Partners for a “New” Audience

Although HAPPI’s primary focus was on increasing CPS use among older adults, it quickly became evident that many CHCs and CBOs had limited exposure to or expertise in the needs of an aging population. Capacity assessment of CHCs made it clear that providing care to the older adult population had not been a traditional area of emphasis. While acknowledging that older adults have been increasing as a proportion of their patient panels, most clinic staff lacked expertise in the specific and unique concerns of an older adult population. Key informant interview data also produced evidence of a clinical culture that was primarily focused on addressing patients’ acute care needs, and less attuned to preventive care and the chronic care needs that are much more prevalent among an aging population.

As a result, HAPPI’s focus broadened considerably, as many partners needed basic information about how to outreach, motivate, and teach older adults. Over time, there was increasing recognition by some CHC and CBO partners that they needed to modify their approach for this new audience. For example, it took time for some partners to understand the great diversity of the older adult population. Programs needed to recognize that they may need to implement different outreach strategies for those who were between 50 and 64 years of age and those who were 65 and older including where and when to hold educational events, the best ways in which to present information, and differences in insurance coverage affecting access to care.

Grantee organizations with an existing or recognized older adult audience had a head start as they had already built relationships and established trust with this population. Some grantees engaged older adult volunteers to conduct peer-to-peer outreach and training, a strategy that was found to be particularly effective. Others engaged older adults in navigator or promotora roles. Some grantees found that testimonials provided by community members who were cancer survivors were especially effective when messaging about the importance of CPS. They reported that older adults seemed to be especially receptive to getting health education and prevention messages from members of their own generational cohort.

Strengthen Cross-sectoral Capacity Through Shared Resources

HAPPI’s capacity-building activities with CHCs and CBOs were designed to enhance cross-sectoral efforts to increase uptake of CPS. Such cross-sectoral opportunities were particularly evidenced in the membership and collaborative work of the CST and the Community Council. In addition, the platform created by the small grants program and enhanced by the community asset map incentivized new or enhanced CBO–CHC linkages. HAPPI organizational participants were empowered through the promotion of these interorganizational activities, which increased their capacity to influence each other, while attaining the resources and power necessary to create social and systems-level change (Peterson & Zimmerman, 2004).

Over time, HAPPI partners identified and assumed complementary leadership roles, providing each other with guidance and resources. For example, members of the HAPPI CST provided expertise on CPS guidelines and communicating guidelines to community audiences. Members also served as faculty for the HAPPI clinic and community training activities, provided information and guest speakers for grantee community education activities, enabled access to inventories of community resources for adults aged more than 50 years, and provided technical assistance to grantees.

The Southside Coalition of Community Health Centers facilitated access and engagement of their members in the assessment and community engagement components of the project. The Department of Aging provided inventory data on their multipurpose senior centers that were mapped by the project team to facilitate online access by project participants. The Office of Women’s Health was a key source of information on local health and social services and provided assistance in accessing these resources through their online and telephone-based LA Healthline service.

The Department of Public Health Service Planning Area (SPA) unit was another key source of linkage to CBOs. The SPA develops and provides relevant public health and clinical services to address the specific needs of local community residents. Engaging local organizations is a key component of program planning and dissemination of health information. The SPA-6 unit, which serves HAPPI’s priority population in South Los Angeles, assisted in the recruitment of organizations to the HAPPI Community Council and hosted the first convening of representatives to form the Council.

The Community Council provided recommendations for the HAPPI community training curriculum and small grants program, and also proved to be key partners to recruit organizations to participate in the HAPPI Ambassador Train the Trainer Course and apply for the small grants. The Council meets quarterly and the meetings have become a key platform for dissemination of findings from the HAPPI project and information on healthy aging programs and resources.

Be Responsive to the Varying Capacity of Partners

Another important lesson was to recognize the varying capacity of HAPPI’s cross-sectoral partners. As such, the implementation of program and evaluation activities was dynamic, adapting to varying levels of readiness and capacity to perform. For example, although some grantees had experience in program planning, implementation, and/or evaluation, others needed guidance. At every step, the HAPPI evaluation team had to be responsive to the individual grantee’s level of readiness rather than assume that everyone was able to adopt and implement a new practice or program at the same pace. Although certainly not the traditional approach of intervention science, it was essential to work with a community in the nascent stages of adopting new practices and developing knowledge and skills.

Plant Seeds for Sustainability

Finally, HAPPI is just a starting point for other health promotion activities. It offers a framework that can now be used to support other community health priorities, for example, interventions to address health behaviors known to increase cancer risk, such as alcohol misuse and smoking. The Community Council is playing a significant role in leading sustainability planning to ensure healthy aging using the CDC Sustainability Planning Guide for Healthy Communities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). It continues to meet quarterly and hosts speakers on topics relevant to healthy aging and CPS. A leadership workgroup is guiding efforts to obtain funding to sustain CPS education, recruitment, and referral in partnership with local health centers, senior centers, health and city agencies, and other CBOs. The Council plans to continue and expand the work of HAPPI and is committed to addressing disparities experienced by the aging population in South Los Angeles. The continued investment of HAPPI organizational participants bodes well for the sustainability of this initiative, especially in the context of incentives that respond to identified community interests (Nichols & Taylor, 2018).

Conclusion

The World Health Organization recently conducted a global review of healthy aging and health inequities and concluded that multisectoral and intersectoral approaches are essential to addressing the social determinants of health in aging populations (Sadana, Blas, Budhwani, Koller, & Paraje, 2016). In the United States, age-friendly community initiatives are engaging stakeholders from multiple sectors to plan local communities that better support older adult health, well-being, and ability to age in place (Greenfield, Oberlink, Scharlach, Neal, & Stafford, 2015). Similar, albeit more narrowly focused, community health initiatives note the promise of CPS delivery models that facilitate collaboration across the sectors of health care, public health, and community (Ogden, Richards, & Shenson, 2012; Shenson et al., 2012).

In South Los Angeles, HAPPI has made important inroads, advancing community health by building capacity to increase knowledge and foster use of CPS through enhanced community–clinic linkages. Early signs of the initiative’s success are the product of multiple efforts, initiated at different entry points, and encouraged by the perceived benefits of collaborating across sectoral divides. These collective efforts have resulted in expanded capacity within and across sectors and encouraged or enhanced linkages between CHCs and CBOs. By jointly participating in capacity-building activities, HAPPI partners identified and shared existing resources, developed new tools and programs, and increased the potential for the sustainability of a collaborative health promotion and cancer prevention network.

The reach of this work to date has been most directly realized through the launch of the small grants program. Most grantees went above and beyond what they had originally proposed to do. For example, several grantees added outreach activities or expanded their training activities to reach a larger audience. By the end of the small grants program, grantees had delivered a total of 234 educational sessions, including workshops and presentations at community events and health fairs. A total of 2,730 African American and Latino seniors received education and referrals, whereas 438 participants also directly received a screening or immunization. The next phase of the project will establish specific health service goals and benchmarks from which to evaluate changes in CPS awareness, attitudes, and behaviors among HAPPI participants. In addition, data collected from HAPPI organizational partners will be assessed to understand more about their motivation and perception of the value of the project.

HAPPI aimed to build capacity by leveraging and connecting existing resources to achieve a common goal. The building blocks provided by the CST, the Community Council, the CHCs, and the CBOs were enhanced through capacity-building activities and tools, including CHC in-service training, CBO ambassador training, community asset maps, and the funding of the small grants program. Furthermore, HAPPI partners assumed leadership roles and acted as change agents who fostered ownership of the HAPPI model, motivating the commitment to sustain it. HAPPI’s success is evidenced by the formation of a collaborative network and framework for health promotion, now positioned to continue to educate about and refer community members to recommended CPS and other primary prevention efforts. The lessons learned can inform other community-based initiatives to advance research and practice on enhancing access to CPS through cross-sectoral approaches.

Funding

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Mobilization for Health: National Prevention Partnership Awards Program (U.S. DHHS Grant No. 1 PAWOS000015-01-00), and the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI; NIH/NCATS UCLA CTSI Grant No. UL1TR000124 and SC CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000130). This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the essential contributions of dozens of collaborators, including the Southside Coalition of Community Health Centers staff June Levine, RN; Nina Vaccaro, MPH; Andrea Williams, MPA; Yolanda Rogers and participating clinics: Eisner Health, South Bay Family Health Care, South Central Family Health Center, St. John’s Well Child and Family Center, To Help Everyone (THE) Health and Wellness Centers; HAPPI Small Grantees Black Women for Wellness, California Black Women’s Health Project, Cedars-Sinai COACH for Kids and their Families, Esperanza Housing Corporation, Girls Club of Los Angeles, Los Angeles Metropolitan Churches, New Visions Christian Fellowship Church, Worksite Wellness; HAPPI Core Support Team Tony Kuo, M.D.; Rita Singhal, M.D.; Annie Pham, MPH; and Anat Louis, PsyD representing Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Office on Women’s Health, Los Angeles City Department of Aging, Los Angeles County Department of Workforce Development, Aging and Community Services; and Jan King, MD, MPH SPA 6 Area Health Officer; Project Partners Los Angeles County Department of Public Health Immunization Program, California Department of Health Care Services Every Woman Counts Program and UCLA Team Henar Abdelmonem, BA; Andrea Ambor, BA; Janet C. Frank, DrPH; Aleah Frison, BS; Angela Gutierrez, MPH; Porsche McGinnis, and Armin Takallou, BS.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Administration for Community Living Older Americans Act Title IIID Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Services. Last updated June 6 2017. Retrieved from https://www.aging.ca.gov/ProgramsProviders/AAA/Disease_Prevention_and_Health_Promotion/#Description. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. (2012). Chronic care: Making the case for ongoing care. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T., Chen E., & Bennett H. D (2009). Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: Can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health affairs (Project Hope), 28, 64–74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Egerter S., & Williams D. R (2011). The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 381–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo R. L., Kietzman K. G., Toy P., Duru O. K., & Wallace S. P. Linking primary care and community organizations to increase colorectal cancer screening rates: The HAPPI project. Salud Publica De Mexico. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey, 2011–2012. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Retrieved from http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Pages/methodology.aspx. Accessed February 23, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll-Scott A., Toy P., Wyn R., Zane J. I., & Wallace S. P (2012). Results from the Data & Democracy initiative to enhance community-based organization data and research capacity. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1384–1391. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC’s healthy communities program: A sustainability planning guide for healthy communities. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/programs/healthycommunitiesprogram/pdf/sustainability_guide.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2017.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force (2018). The community guide. Retrieved from http://www.thecommunityguide.org/. Accessed December 14, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. B., & Shaw F. E.; Office of Health System Collaboration, Office of the Associate Director for Policy, CDC (2014). Relationship of income and health care coverage to receipt of recommended clinical preventive services by adults—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63, 666–670. PMCID: PMC4584657, PMID: 25102414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. B., & Shaw F. E (2015). Clinical preventive services coverage and the affordable care act. American Journal of Public Health, 105, e7–e10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J. C., Kietzman K. G., & Wallace S. P (2014) Bringing it to the community: Successful programs that increase the use of clinical preventive services by vulnerable older populations. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Retrieved from http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/2014/preventiveservicespb-aug2014.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Black K., Buffel T., & Yeh J (2018). Community gerontology: A framework for research, policy, and practice on communities and aging. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. August 13, 2018. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield E. A., Oberlink M., Scharlach A. E., Neal M. B., & Stafford P. B (2015). Age-friendly community initiatives: Conceptual issues and key questions. The Gerontologist, 55, 191–198. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., & Becker A. B (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzman K. G., Wallace S. P., Bravo R. L., Sadegh-Nobari T., & Satter D. E (2012). Opportunity knocks for preventive health. Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; Retrieved from http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/search/pages/detail.aspx?PubID=1099. Accessed June 21, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Koh H. K., Piotrowski J. J., Kumanyika S., & Fielding J. E (2011). Healthy people: A 2020 vision for the social determinants approach. Health Education & Behavior, 38, 551–557. doi: 10.1177/1090198111428646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P. M., Evans W. D., Mead H., Alvarez C., & Stewart L (2016). Knowledge of and attitudes toward evidence-based guidelines for and against clinical preventive services: Results from a national survey. The Milbank Quarterly, 94, 51–76. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Storms L., & Wallace S. P (2003). Use of mammography screening among older Samoan women in Los Angeles county: A diffusion network approach. Social science & medicine (1982), 57, 987–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00474-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multack M. (2013). Use of clinical preventive services and prevalence of health risk factors among adults aged 50–64. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of City and County Health Officials (2013). Mobilizing for action through planning and partnerships (MAPP). Retrieved from http://archived.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/mapp/framework/. Accessed March 3, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2016). National health interview survey, 2015. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- National Prevention Council (2011). National prevention strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols L. M., & Taylor L. A (2018). Social determinants as public goods: A new approach to financing key investments in healthy communities. Health affairs (Project Hope), 37, 1223–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden L. L., Richards C. L., & Shenson D (2012). Clinical preventive services for older adults: The interface between personal health care and public health services. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 419–425. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partnership for Health in Aging (2010). Multidisciplinary competencies in the care of older adults at the completion of the entry-level health professional degree. New York: American Geriatrics Society; Retrieved from https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Multidisciplinary_Competencies_Partnership_HealthinAging_1.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson N. A., & Zimmerman M. A (2004). Beyond the individual: Toward a nomological network of organizational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 129–145. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000040151.77047.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos C., Spencer A. C., Shah A., Palmer A., Forsberg V. C., & Devers K (2014). Factors that influence preventive service utilization among adults covered by medicaid: Environmental scan and literature review. The Urban Institute. Contract Number: HHSM-500-2010-00024I/HHSM-500-T0005. [Google Scholar]

- Reverby S. M. (2012). Ethical failures and history lessons: The US public health service research studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. Public Health Reviews, 34, 13. doi: 10.1007/BF03391665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J., Doty M. M., Abrams M. K., & Riley P (2014). The adoption and use of health information technology by community health centers, 2009–2013. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Sadana R., Blas E., Budhwani S., Koller T., & Paraje G (2016). Healthy ageing: Raising awareness of inequalities, determinants, and what could be done to improve health equity. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl 2), S178–S193. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez E. (2007). Preventive care: A national profile on use, disparities, and health benefits. Partnership for Prevention, Washington, DC: National Commission on Prevention Priorities. [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D. (2006). The prevention challenge and opportunity. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 25, 1009–1011. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenson D., Adams M., Bolen J., Wooten K., Clough J., Giles W. H., & Anderson L (2012). Developing an integrated strategy to reduce ethnic and racial disparities in the delivery of clinical preventive services for older Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 102, e44–e50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenson D., Benson W., &Harris A. C (2008). Expanding the delivery of clinical preventive services through community collaboration: The SPARC model. Preventing Chronic Disease, 5 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/07_0139.htm. Accessed March 6, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2000). Healthy people 2020. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Retrieved from https://www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed March 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ward P. R. (2017). Improving access to, use of, and outcomes from public health programs: The importance of building and maintaining trust with patients/clients. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 22. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A., Thompson T. D., White M. C., Sabatino S. A., de Moor J., Doria-Rose P. V., … Richardson L. C (2017). Cancer screening test use—United States, 2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66, 201–206. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S. Y., & Green A (2000). Projection of chronic illness prevalence and cost inflation. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health, pp.18. [Google Scholar]