Abstract

Background:

Fentanyl as an epidural additive act on spinal opioid receptors, while dexmedetomidine has selective alpha-2 receptor agonist action enhancing analgesic effects.

Aims:

We aimed to compare the postoperative analgesic efficacy of single doses of dexmedetomidine against fentanyl as epidural adjuvant to 0.125% bupivacaine.

Settings and Design:

A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind trial was conducted in a tertiary care teaching institute.

Patients and Methods:

Forty-six patients undergoing abdominal surgery under general anesthesia with epidural analgesia were allocated into two groups to receive postoperative analgesia with single doses of 10 mL 0.125% bupivacaine with the addition of dexmedetomidine 0.5 μg.kg-1 (Group D) or fentanyl 0.5 μg.kg-1 (Group F). The primary outcome was the duration of postoperative analgesia between the two groups. The secondary outcomes were hemodynamic variations, vasopressor need, and motor blockade.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square test for static parameters and Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables were used for analysis.

Results:

The duration of analgesia was longer in Group D (5.0 ± 2.0 h) versus Group F (2.9 ± 1.4 h), Sixteen patients in Group D versus seven patients in Group F needed vasopressors after the bolus to maintain the blood pressure (BP) within 20% of prebolus value (P = 0.018). Heart rate and mean and systolic BP were lower in Group D at various time points following bolus administration.

Conclusion:

A single dose of dexmedetomidine as an additive to epidural local anesthetic postoperatively prolongs the duration of analgesia in comparison to fentanyl but is associated with changes in hemodynamics, including the need for the administration of vasoactive drugs.

Keywords: Epidural dexmedetomidine, epidural fentanyl, postoperative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Epidural analgesia has become the most commonly used technique for effective postoperative pain relief following open abdominal surgery.[1,2] The addition of opioids such as fentanyl lowers the dose of local anesthetic required and also provides superior analgesia by its action on a separate pain pathway, namely, μ-opioid receptors. Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha-2A receptor agonist that decreases the sympathetic outflow and norepinephrine release and mediates analgesic effects.[3] There are limited studies comparing epidural dexmedetomidine to fentanyl in major abdominal surgeries. We aimed to compare the duration of analgesia following a single postoperative dose of epidural dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl as an adjuvant in 0.125% bupivacaine in abdominal surgery to document improved analgesic effects with dexmedetomidine. We also assessed the degree of hemodynamic instability and the extent of motor blockade between the groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

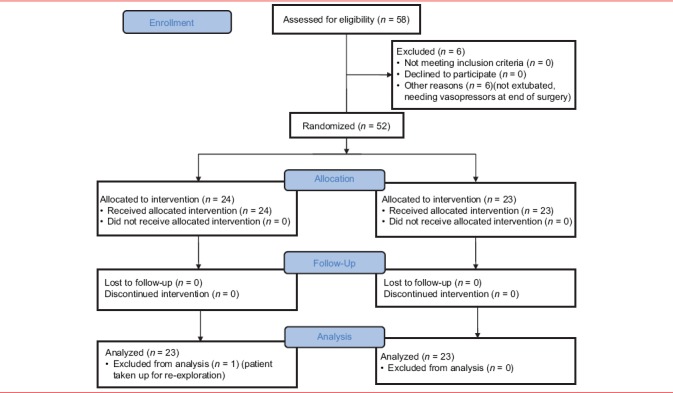

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study conducted in the patients presenting for open gastrointestinal or urologic procedure under combined general and epidural anesthesia at a tertiary care center in South India between December 2015 and April 2016 (CTRI/2016/05/006961). Following Institutional Ethics Committee approval consenting American Society of Anesthesiologists I and II patients aged 18–80 years presenting for elective abdominal surgery needing general anesthesia with scope for epidural analgesia was included. We excluded patients unwilling for epidural, patients on vasopressors after extubation, and those who were ventilated after surgery [Table 1]. All patients followed a standard anesthesia premedication and induction protocol. Premedication included tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg and tablet pantoprazole 40 mg administered on the night before the surgery unless contraindicated (bowel obstruction and obstructive sleep apnea). Induction was with intravenous midazolam 0.05 mg.kg-1 and fentanyl 0.5 μg.kg-1 and propofol titrated to a loss of verbal response. Intubation was accomplished with atracurium 0.5 mg.kg-1 or suxamethonium when indicated. Prior to induction, an epidural catheter was inserted in the lower thoracic space (T8–T12). Intravascular or an intrathecal placement was excluded with a test dose of 3 mL of 2% lignocaine with 1 in 200,000 adrenaline. Intraoperatively during surgery, all patients received an epidural infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine without any additive at 5–6 mL/h after induction. Noradrenaline was added as the vasopressor when the mean arterial pressure (MAP) was <20% from the baseline. Patients who had an increase in heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) with surgery were administered an additional epidural bolus of 10 mL 0.125% bupivacaine. Any patient who did not respond to two successive boluses was considered to have a nonworking epidural and was excluded from the study. Fluid management during surgery and the use of invasive arterial and central venous lines were decided by the anesthetist in the operating room. The epidural infusion of local anesthetic was discontinued at the end of the surgery; all patients were shifted to the postsurgical intensive care unit (ICU) and monitored as per protocols.

Table 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

All patients were extubated, and not on vasopressors were recruited. Patients were randomly allotted to one of two groups using a computer-generated random number sequence given by the statistician, and the random allocation was ensured using sequentially-numbered opaque-sealed envelopes. Consent was obtained from the patient prior to surgery after explanation of the procedure. The primary investigator in charge of the study selected a random envelope and loaded the appropriate drug in a 10 mL syringe that was provided to the intensivist, and nurse who was blinded to the study drug. The management of the patient after the administration of the epidural bolus was according to the set protocols.

Patients received in the ICU were monitored for pain using the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), with 0 representing the complete absence of pain and 10 as the worst pain imaginable, and questioned at intervals on how they would rate their pain. Intervention for pain management was performed when the NRS for pain was >3. At this point, patients were administered epidural medication as per randomization.

Group D: patients received epidural bolus of 10 mL (0.125%) bupivacaine with 0.5 μg.kg-1 dexmedetomidine

Group F: patients received epidural bolus of 10 mL (0.125%) bupivacaine with 0.5 μg.kg-1 fentanyl.

The drugs were administered by the ICU intensivist who was blinded to the study drug, and readings taken by the intensivist and the nurse in charge of the patient. The time of administration was the start time for the duration of analgesia. The NRS for pain, HR, systolic BP, MAP, SpO2, use of vasopressors, and modified Bromage scale were recorded at half hourly intervals. The time point at which the NRS increased above 3 was the end-point in the study, and the time duration after the study drug administration until the NRS >3 was taken as the duration of pain relief obtained by the study drug.

At the time of administration of the epidural bolus in the ICU, all patients received 250 mL crystalloid solution over 5 min. Patients with central venous pressure <6 mmHg after this bolus received an additional bolus of 250 mL over the next 15 min. This was performed in all patients with an aim to limit hypotension following epidural-induced vasodilatation. The management of BP changes following drug administration was according to a standardized protocol. The HR and BP responses were documented at 5-min intervals for 15 min and at half hourly intervals thereafter. Noradrenaline was added if the MAP fell lower than 20% of the predrug administration value at any point during the study. Bradycardia was defined as a HR <60/min, and treatment with atropine 0.6 mg was to be administered.

The time from the epidural bolus drug administration until the time for the patient's pain score to reach a score of 4 (≤3 considered as satisfactory) on the NRS was the end-point of the study. Following this, all patients were managed by the standard epidural analgesia protocol with 0.125% bupivacaine with 2 μg/mL fentanyl titrated to pain relief as an infusion.

The motor blockade was assessed prior to the bolus administration and at half hourly intervals for the duration of the study and graded by the modified Bromage scale. The patient was also observed for other side effects such as nausea, vomiting, or pruritus following epidural drug administration.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the sample size from a pilot study conducted at our center prior to this study, comparing analgesia with the same drugs as the study. The mean duration of analgesia with dexmedetomidine was 6.8 ± 4.0 h and that with fentanyl 4.0 ± 2.7 h. Using a mean difference of 2.8 h, allowing an alpha error of 5%, with 95% confidence, and 80% power minimum sample size was calculated as 23 for comparing Groups D and F. We recruited 46 patients in total, 23 in Groups D and F. The statistical analysis was performed using a Chi-square test for a comparison of the categorical values between the groups. The duration of pain relief and hemodynamic factors between the groups were compared using the independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. The analysis was performed using SPSS software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA.

RESULTS

The age, height, weight, and duration of the surgery between all three groups were comparable [Table 2]. The types of surgery were similar between all three groups and included gastrectomy, hepatectomy, Whipple's pancreaticoduodenal resection, colectomy, small bowel resection, and open cholecystectomy. The mean intraoperative use of local anesthetic and intraoperative use of vasopressors among the groups included for the study were comparable [Table 3]. Mean duration of pain relief after the epidural bolus was 5.0 ± 2.0 h for dexmedetomidine versus 2.9 ± 1.4 h for fentanyl. Out of the 46 patients, 12 patients in Group D and 6 in Group F developed hypotension within 15 min after bolus administration (P > 0.05). Sixteen patients in Group D versus 7 in Group F needed noradrenaline after the bolus as per our defined criteria [Table 3]. The NRS after bolus administration was comparable between Groups D and F at all-time points, except at 150 min after bolus administration [Table 4].

Table 2.

Demographics

| Mean±SD | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexmedetomidine (D) | Fentanyl (F) | ||

| Age years | 52.2±15.0 | 57.5±14.6 | 0.233 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 8 (34.8) | 10 (43.5) | 0.763 |

| Female | 15 (65.2) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Height (cm) | 160.7±8.7 | 160.0±10.3 | 0.818 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.6±10.7 | 61.0±10.6 | 0.282 |

| Duration of surgery (h) | 5.1±2.2 | 5.6±1.9 | 0.447 |

SD: Standard deviation, D: Group dexmedetomidine, F: Group fentanyl

Table 3.

Pain relief and hemodynamics following bolus

| Parameters | Dexmedetomidine (D) (n=23), n (%) | Fentanyl (F) (n=23), n (%) | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotension 15 min bolus | |||

| No | 11 (47.8) | 17 (73.9) | 0.131 |

| Yes | 12 (52.2) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Inotropic support | |||

| No | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | 0.018 |

| Yes | 16 (69.6) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Duration of pain relief after bolus (hours) | 5.0±2.0 | 2.9±1.4 | <0.001 |

D: Group dexmedetomidine, F: Group fentanyl

Table 4.

Visual analog scoring for pain following epidural bolus

| VAS (min) | n | Dexmedetomidine (D), median (IQR) | n | Fentanyl (F), median (IQR) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 23 | 5.0 (4-6) | 23 | 5.0 (5-6) | 0.509 |

| 5 | 23 | 3.0 (2-4) | 23 | 3.0 (2-4) | 0.734 |

| 10 | 23 | 2.0 (1-3) | 23 | 2.0 (1-3) | 1.000 |

| 15 | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 0.490 |

| 30 | 23 | 2.0 (1-2) | 23 | 2.0 (1-2) | 0.894 |

| 60 | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 0.273 |

| 90 | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 21 | 1.0 (1-2) | 0.103 |

| 120 | 23 | 1.0 (1-2) | 17 | 2.0 (1-2) | 0.063 |

| 150 | 22 | 1.0 (1-2) | 15 | 2.0 (1-4) | 0.017 |

| 180 | 21 | 1.0 (1-2) | 11 | 2.0 (1-3) | 0.441 |

| 210 | 17 | 1.0 (1-2) | 8 | 2.0 (1-4) | 0.194 |

| 240 | 17 | 2.0 (1-2) | 5 | 1.0 (0.5-2) | 0.526 |

D: Group dexmedetomidine, F: Group fentanyl, VAS: Visual analog scoring, IQR: Interquartile range

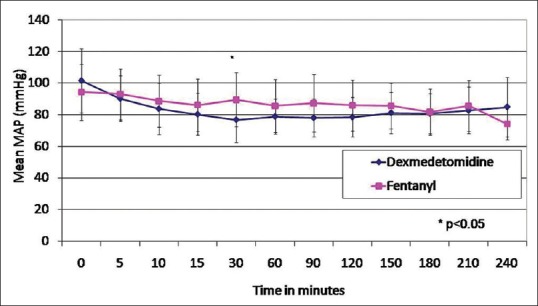

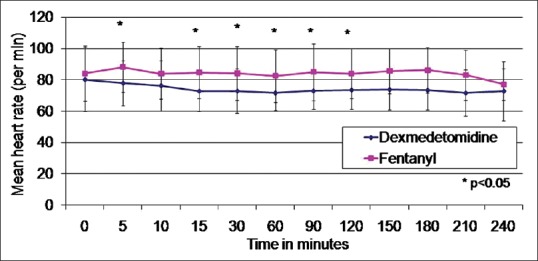

The MAP was significantly lower in the dexmedetomidine group at 30 min in comparison with the fentanyl group [Figure 1]. The HR was significantly lower in Group D in comparison to Group F at 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 1 h 30 min, and 2 h after bolus administration [Figure 2]. However, none of the patients had HR lower than 60/min warranting the need for chronotropic drugs. None of the patients had motor blockade after epidural bolus administration. There were no adverse side effects such as nausea, vomiting, or pruritus following administration of the study drug.

Figure 1.

Mean arterial pressure in Groups D and F

Figure 2.

Mean heart rate between Groups D and F

DISCUSSION

Epidural dexmedetomidine has been shown to be safe as an additive to bupivacaine in patients, and even those undergoing high-risk vascular surgery.[4,5] We proposed to evaluate the efficacy of dexmedetomidine in prolongation in the duration of analgesia in comparison to fentanyl combined with a standard concentration of epidural anesthetic in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Although there are reports mastectomy, of the use of epidural dexmedetomidine with clonidine in lower limb surgeries and gynecological surgery, and[6,7,8] there are very few studies in the abdominal surgery. We anticipated that hemodynamic responses could be altered in abdominal versus lower limb surgery. To avoid confounding factors for the continuous infusion of local anesthetic with additive perioperatively, we chose to administer the drugs postoperatively under surveillance and protocolized to minimize hemodynamic responses.

Epidural dexmedetomidine also appeared to cause a lowering of HR at various time points in administration, although treatment for bradycardia was not needed, and this was similar to other studies with epidural dexmedetomidine.[6,7,8,9,10]

Contrary to these studies, we noticed that our patients had significant hypotension, and this was endorsed in a few studies.[10,11] Soliman and Eltaweel[11] had used an infusion of 2 μg/mL in an infusion of 0.125% bupivacaine postoperatively in knee surgeries and documented a 20% incidence of hypotension. This was significantly higher than the group that received fentanyl at the same dose. Chakole et al.[10] had concluded that epidural dexmedetomidine in doses ≥2 μg.kg-1 resulted in bradycardia, and significant hypotension in patients undergoing lower limb and pelvic surgeries but not in lesser doses.

As we administered a bolus after major abdominal surgery with an intraoperative epidural infusion, we had reduced the dose of dexmedetomidine to 0.5 μg.kg-1 added to 10 mL of 0.125% bupivacaine. We also instituted noradrenaline support, if the MAP fell below 20% of the value at bolus administration to avoid any compromise in the care of the patient. The higher incidence of hypotension, even at very small doses in our study (dexmedetomidine 52.2% and 26.1% in the fentanyl group) are reflective of greater vasodilatation during major abdominal surgery. None of the groups had motor blockade or side effects such as pruritus, nausea, or vomiting following epidural bolus.

There is limited literature on a comparison of epidural fentanyl versus epidural dexmedetomidine.[6,7,11] Epidural fentanyl binds to opioid receptors after crossing the dura, or it can be absorbed systemically and exert its action through the supraspinal route. Although the mechanism postulated for its action in labor is spinal opiate receptor binding, several other studies comparing epidural versus intravenous fentanyl have shown no differences in analgesia, serum levels, or side effects suggesting that the epidural route may exert its actions through systemic absorption.[12]

We performed our study in the ICU when the patient had recovered from the effects of intraoperative analgesics, and the pain scores were above 3. The types of surgery, anesthesia technique, and the volume of analgesics used intraoperatively were similar. The measurement of the pain was made by an intensivist who was blinded to the drug administered epidurally. We had excluded patients who required vasopressors or inotropic supports at extubation to eliminate exaggerated hypotension following epidural bolus. However, we included patients who needed intraoperative vasopressors that were discontinued an hour before the end of the surgery. Both the groups were comparable with regard to duration of surgery and volume of local anesthetic used intraoperatively.

The duration of pain relief was significantly higher in the dexmedetomidine group. This finding appears to correlate with the results of other workers who compared the postoperative analgesic effects of dexmedetomidine administered epidurally in the perioperative period.[6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] In our study, the dosing of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl was calculated to 0.5 μg.kg-1. There are no comparisons of equipotent dosing of epidural dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl. Studies have compared 1 μg.kg-1 dexmedetomidine and fentanyl[6,7] or 2 μg/mL infusion with local anesthetic[7] but for lower limb surgery. Other studies have compared epidural dexmedetomidine versus clonidine, and the doses varying between 1 μg and 1.5 μg.kg-1 administered as a single bolus for orthopedic, mastectomy and gynecological surgeries.[8,9,10,12,13]

The onset of analgesia as measured by the NRS, after bolus administration was similar in both groups, and scores were <3 in 10 min. This again correlates with the peak onset time for analgesia described in other studies, although some studies have reported an earlier onset of sensory block.[6,9] In our study, the pain scores in Group F had increased at 2 h, while Group D remained at 1 D clearly providing an advantage with the use of dexmedetomidine.

We believe that a judicious use of dexmedetomidine could provide an advantage on the onset and quality of analgesia in an epidural. We followed a restrictive fluid policy intraoperatively, as it is believed to be associated with improved outcomes after abdominal surgery.[16,17] The use of noradrenaline intraoperatively was part of the restrictive fluid strategy for abdominal surgery and was not associated with any adverse outcomes in our patients. We chose to supplement a vasopressor at 20% fall in MAP to avoid any compromise in circulation and also since we believed that it is not associated with potential harm for the patient. It is possible that the hypotension was documented even when the pressures were acceptable on account of this protocol.

Our study had its limitations. As we could not find any reference that compared equianalgesic doses of bupivacaine or fentanyl, we compared 0.5 μg/mL of both. To check and objectively document analgesia, we interrupted the infusion postoperatively. The epidural catheters were sited at any space below T8 and T12 based on the surgical incision, and postoperative bolus doses did produce fall in BP that we managed as per protocol. We could document extended analgesia with dexmedetomidine, but also increased hypotension needing inotropes contrary to lower limb and gynecological surgeries. Our findings appear in line with the meta-analysis of Wu et al.[18] who had concluded that dexmedetomidine as a neuraxial adjuvant provides longer and better analgesia but is associated with significant bradycardia and an increased incidence of hypotension.

CONCLUSION

A single bolus dose epidural bupivacaine 0.125% with dexmedetomidine at 0.5 μg.kg-1 produces longer duration of analgesia compared to 0.125% bupivacaine with 0.5 g/kg fentanyl in open abdominal surgery but is associated with an increased need of vasopressor and hemodynamic changes following administration.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schultz AM, Werba A, Ulbing S, Gollmann G, Lehofer F. Peri-operative thoracic epidural analgesia for thoracotomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1997;14:600–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1994.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberg GL. Lipid emulsion infusion: Resuscitation for local anesthetic and other drug overdose. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:180–7. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825ad8de. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaakola ML, Salonen M, Lehtinen R, Scheinin H. The analgesic action of dexmedetomidine – A novel alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist – In healthy volunteers. Pain. 1991;46:281–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90111-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathyanarayana LA, Heggeri VM, Simha PP, Narasimaiah S, Narasimaiah M, Subbarao BK. Comparison of epidural bupivacaine, levobupivacaine and dexmedetomidine in patients undergoing vascular surgery. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:UC13–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17344.7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grewal A. Dexmedetomidine: New avenues. J Anaesth Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:297–302. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.83670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajwa SJ, Arora V, Kaur J, Singh A, Parmar SS. Comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl for epidural analgesia in lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:365–70. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.87264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill RS, Acharya G, Rana A, Arora KK, Kumar D, Sonkaria LK. Comparative evaluation of the addition of fentanyl and dexmedetomidine to ropivacaine for epidural anaesthesia and analgesia in lower abdominal and lower limb orthopedic surgeries. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 2016;3:200–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Channabasappa SM, Venkatarao GH, Girish S, Lahoti NK. Comparative evaluation of dexmedetomidine and clonidine with low dose ropivacaine in cervical epidural anesthesia for modified radical mastectomy: A prospective randomized, double-blind study. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:77–81. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.167844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh G, Arora V, Gupta S, et al. Dexmedetomidine and clonidine in epidural anaesthesia: A comparative evaluation. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.79883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakole V, Kumar P, Sharma M. Effect of dexmedetomidine on postoperative analgesia and haemodynamics when added to bupivacaine 0.5% in epidural block for pelvic and lower limb orthopaedic surgeries. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2016;3:2239–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soliman R, Eltaweel M. Comparative study of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl as an adjuvant to epidural bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief in adult patients undergoing total knee replacement: A randomized study. J Anesthesiol Clin Sci. 2016;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Angelo R, Gerancher JC, Eisenach JC, Raphael BL. Epidural fentanyl produces labor analgesia by a spinal mechanism. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1519–23. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199806000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saravana Babu MS, Verma AK, Agarwal A, Tyagi CM, Upadhyay M, Tripathi S. A comparative study in the postoperative spine surgeries: Epidural ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine and ropivacaine with clonidine for post-operative analgesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:371–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.118563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain D, Khan RM, Kumar D, Kumar N. Perioperative effect of epidural dexmedetomidine with intrathecal bupivacaine on haemodynamic parameters and quality of analgesia. South Afr J Anaesth Analgesia. 2012;18:105–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta K, Rastogi B, Gupta PK, Jain M, Gupta S, Mangla D. Epidural 0.5% levobupivacaine with dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl for vaginal hysterectomy: A prospective study. Indian J Pain. 2014;28:149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleier JI, Aarons CB. Perioperative fluid restriction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26:197–202. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia FJ, Yan QY, Sun Q, Tuxun T, Liu H, Shao L, et al. Liberal versus restrictive fluid management in abdominal surgery: A meta-analysis. Surg Today. 2017;47:344–56. doi: 10.1007/s00595-016-1393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu HH, Wang HT, Jin JJ, Cui GB, Zhou KC, Chen Y, et al. Does dexmedetomidine as a neuraxial adjuvant facilitate better anesthesia and analgesia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]