Abstract

In February 2003, Needham, Massachusetts, became the first town in the nation to raise the minimum legal sales age for tobacco and nicotine products to 21 years (Tobacco 21). This legislation marked a dramatic departure from existing state and federal laws, which generally set the minimum sales age at 18 years. The Needham law significantly preceded and ultimately heralded the emergence of a nationwide movement to raise such sales age. As of May 2019, 14 states and more than 450 cities and counties have passed legislation raising the minimum legal sales age for tobacco and nicotine products to 21 years, covering more than 30% of the United States’ population. The National Academy of Medicine projects that this policy will lower tobacco use rates, particularly among adolescents, and save a substantial number of lives. This narration of the process that led to Needham’s passing of Tobacco 21 legislation and to the growth and spread of the Tobacco 21 movement highlights the significant role of public health advocacy and policy in the control of tobacco, the leading preventable cause of disease and death in the United States. (Am J Public Health. 2019;109:1540–1547. doi: 10.2105/AJPH. 2019.305209)

By 1920, half of US states had set the tobacco minimum legal sales age to at least 21 years. However, in spite of overwhelming scientific evidence of the harm of tobacco, over the next 60 years the tobacco industry’s successful lobbying gradually eroded the age of sale in such states to between 16 and 18 years.1 In 1992, Congress responded with the enactment of the Synar Amendment, setting the federal minimum legal age of access to 18 years2 and by 1993 all states had changed their minimum legal sales age to 18 or 19 years.3 The tobacco industry lobbied in support of Congress’s proposal, most likely as a way of counteracting the American Medical Association’s 1985 recommendation to raise the minimum sales age to 21 years.4 At the time, it was clear that the tobacco industry viewed restoration of a higher minimum legal age of access as a primary business threat that, “could cause nearly a $400 million drop in [sales].”5 The tobacco industry’s self-serving and persistent political advocacy underscores its recognition that continuing to recruit and addict youth smokers remains critical to the industry’s survival.6

Needham, Massachusetts, had been an early adopter of other tobacco control legislation in the decade before its historic action to raise the legal sales age for tobacco and nicotine products to 21 years. The Needham Board of Health had previously voted to limit restaurants in town to a smoking area of 25%, and by 1997 Needham had become one of the first towns in Massachusetts to pass legislation regarding smoke-free workplaces.7

THE EMERGENCE OF TOBACCO 21 LEGISLATION

As a consultant to the Needham public schools beginning in 1994, Needham Board of Health member Alan Stern, MD, had repeatedly heard from the town’s school administration that there were concerns in the community about students obtaining tobacco products and smoking around campus. In approximately 1999, it became apparent that underage students were accessing tobacco products through those aged 18 and 19 years who could legally purchase such products. In addition, underage sales to minors were suspected.8 As DiFranza and Brown note in the tobacco control literature, during the 1990s illegal sales of tobacco to minors was a nationwide trend.9 To begin to address this problem, the Needham Board received a grant to sample underage tobacco access and assess whether those aged younger than 18 years were in fact able to purchase cigarettes. The results demonstrated the ease with which tobacco could be illegally purchased and led to a discussion among Board members regarding the timing of tobacco addiction and ways to inhibit minors’ access to tobacco.10

While the Needham Board of Health was actively discussing how to prevent adolescent tobacco use, Stern first raised the idea of Tobacco 21.11 Stern reasoned that if the Board were to raise the minimum legal age of access from 18 to 21 years, this policy would potentially limit 18-year-old high-school seniors’ access to tobacco products and the sharing of these products with even younger students.12

Knowing that high-risk behaviors that begin during the adolescent years can translate into lifelong habits, Stern viewed the late adolescent years as a critical window in which to enact an addiction prevention initiative. While the Board continued to discuss other policies, all Board members came to strongly support Stern’s idea. As Stern later explained, the Needham Board in no way aimed to be “pioneers in the nation,” but rather thought that passing the policy “was a good thing to do.”13 While questions remained regarding the legality of the proposed policy, the change “made good biological, medical sense” to the Board members.14 Although there were no data available at the time to suggest that Tobacco 21 is an effective tobacco control policy, the Board knew of evidence that supported the effectiveness of raising the legal age of sale of alcohol from 18 to 21 years.15

When the proposed policy developed into a genuine interest of the Needham Board of Health, the Board contacted D. J. Wilson, JD, of the Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA).16 The MMA is a membership organization for local Massachusetts officials including mayors, city councilors, town selectmen, town managers, personnel directors, and town finance committee members. Currently, all 351 Massachusetts towns are MMA members.17 Wilson, as a lawyer and advisor for the MMA, is a leader of the antitobacco movement and provided a “wealth of information,”18 advising the Needham Board regarding the establishment of the new policy.

Eventually, Needham’s new tobacco regulations were written with the cumulative input of several additional individuals including the town selectmen, the town lawyer, the town council, and local merchants.19 Agendas for Board of Health meetings were posted ahead of time and meetings were open to the public, ensuring that the voices of the town would be heard and that questions were addressed. The Board also made sure to keep tobacco vendors up to date, sending letters to permit-holding businesses informing them of the status of policy discussions and of dates and times of open meetings.20

On the whole, the Needham community supported the proposed changes. However, many local merchants expressed unease with the policy, as did representatives from the Massachusetts Retail Association. Large chains such as Walgreens and CVS voiced their opposition and sent lawyers and store owners to the meetings to question whether the proposed changes were proceeding legally. Multiple revisions of the proposed regulations resulted from such conversations, taking place over a two-year period.21 While many were vocal in expressing their concerns at public meetings, the tobacco industry offered minimal resistance to the policy. As Stern later speculated, “the tobacco industry thought ‘this was a town with 30,000 people; it’s a blip on the radar.’ They didn’t think much would happen. And I think they miscalculated on that.”22

While many in the Needham community supported Tobacco 21 legislation, members of the town’s Board of Selectmen, the town’s executive branch of government, were initially opposed to the policy. According to former Director of Public Health Janice Berns and former Board of Health member Stern, Needham’s selectmen “were probably 100 percent opposed” to the policy throughout the discussion phase.23 Stern suggests the selectmen felt that it was “their job to protect Needham businesses” and thus they needed to prevent the policy from infringing upon such businesses, regardless of the fact that the selectmen likely saw the policy as making good health sense.24 Eventually, former Needham selectman John Bulian explains, the Needham selectmen concluded that the policy is “a good thing—we knew it was a good thing at the time it was passed.”25 However, Bulian recalls discussions regarding the impact the policy would have on small business establishments, even though he recognizes that it never made sense that Walgreens and CVS sold cigarettes while dispensing medications to support individuals’ health.26

Before voting on the policy, the Board consulted with the state legislative attorney to understand the boundaries of their rights and powers as a local Board of Health. The Board discovered that Massachusetts boards of health have a significant amount of autonomy in terms of making health regulations and enacting them.27 After research and multiple discussions, meetings, and consultations, the Needham Board of Health unanimously passed the Tobacco 21 policy.

NEEDHAM IMPLEMENTS TOBACCO 21 LEGISLATION

On February 27, 2003, Berns, the director of public health at the time, wrote to retail tobacco vendors, informing them that the previous day the Board of Health had amended its tobacco regulations “to state that, as of April 1, 2003, no person shall sell tobacco products or permit tobacco products to be sold to any person under the age of nineteen (19), with the legal age to sell tobacco products eventually rising to twenty-one (21) on April 1, 2005.”28 In an effort to further deter individuals from using tobacco products, regulations governing retail sales of tobacco had also been amended at the same meeting, and the annual fee for a Permit to Sell Tobacco and Tobacco Products was raised to $500.29 Following distribution of the letter alerting retailers of the regulatory changes, the Health Department created a training manual and instructional video explaining the new regulations and the procedures to properly sell tobacco products under the law.30

At the time of the policy change, the Needham Board of Health consisted of three publicly elected board members, each serving a 3-year term: Peter Connolly, MD, Edward Cosgrove, PhD, and Stern. Thus, individuals with medical and scientific backgrounds who were elected by town citizens developed and enacted Needham’s Tobacco 21 sales policy. Although the local media closely followed the law’s passing, it made few if any national headlines.

ENFORCEMENT

Following passage of Needham’s tobacco policy, enforcement efforts took on a central role. Needham Public Health Director Timothy McDonald explains, “a regulation without enforcement actions behind it is fairly toothless.”31 Thus, Needham laid out strict penalties for compliance violations. As stated in the 2003 regulations, if a person aged younger than 21 years is sold tobacco, a vendor’s penalties could include a tobacco permit suspension, which would require removal of all tobacco products from the sales floor and a fine of up to $100.32 A week’s loss of tobacco sales could cost a vendor up to $10 000, as tobacco products can account for up to 40% of a retailer’s total product sales.33 A second violation within a two-year period could result in a vendor’s multiple-month permit suspension, and a third violation could trigger a complete tobacco permit revocation.34

Needham’s low tobacco outlet density contributes to the Health Department’s ability to encourage proper compliance with the age of sale policy. Needham’s tobacco regulations currently place a cap35 on the number of Tobacco and Nicotine Delivery Product Sales Permits issued, allowing a maximum of 12 permits. A waiting list exists for additional retailers interested in selling tobacco. By contrast, Massachusetts towns such as Norwood that have populations similar to that of Needham may house upward of 50 locations that hold tobacco permits.36

Before 2003, quarterly enforcement and compliance checks were completed by a state-sponsored inspector in conjunction with adolescents aged younger than 18 years as part of Needham’s membership in a seven-town tobacco control coalition. However, Needham decided to opt out of these checks shortly after the new regulations were introduced, and quarterly checks were incorporated into the regular duties of the Needham health agent. As part of a system of checks, the Health Department also recruited individuals aged 18 to 20 years from surrounding towns to attempt to purchase tobacco products at local retailers.37

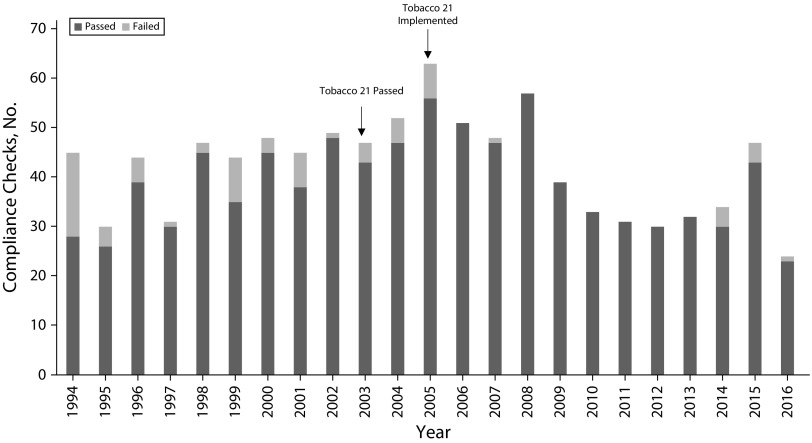

Currently, four compliance checks per store occur per year. In addition, inspections occur twice a year, which intend to ensure proper display of signage and placement of tobacco products behind the sales counter.38 While it took more than two years for compliance checks to have a positive impact on underage sales, following increased enforcement efforts the number of compliance violations dropped dramatically (Figure 1).39 Over the eight-year period from 1996 to 2003, 32 compliance violations occurred in Needham. By contrast, only one violation occurred from 2006 to 2013. A more recent slight increase in violations emphasizes the importance of supporting public health policy with a continuous focus on compliance.

FIGURE 1—

Needham, Massachusetts, Retailers’ Compliance With the Legal Minimum Age of Tobacco Sales, Before and After the Passage of Tobacco 21: 1994–2016

Note. Figure based upon data provided by Timothy McDonald, Needham Director of Public Health, by e-mail, August 1, 2018.

METROWEST ADOLESCENT HEALTH SURVEY

The MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey was first administered in the fall of 2006, approximately one year after the Needham Tobacco 21 sales-age policy had gone into full effect.40 At this point, Needham was the only locale in the United States to have raised the tobacco sales age from 18 to 21 years. The data accumulated through analysis of this survey’s results became pivotal in supporting the emergence and expansion of the state and nationwide Tobacco 21 movement.

The MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey is an anonymous, classroom-administered survey that covers many of the topics assessed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey.41 As MetroWest Health Foundation CEO Martin Cohen notes, in 2006 the organization sought to distribute grants to communities most in need of assistance, but MetroWest lacked good data to accurately identify areas of need. Seeking evidence to inform their efforts as a funding agency by capturing health trends specific to local communities, MetroWest contracted a survey to the Education Development Center. Since the fall of 2006, the survey has been conducted every other year and assesses both current (in the last 30 days) cigarette smoking (any vs none) and current purchase of cigarettes in a store.42

The initial survey was conducted in grades 9 through 12 in 18 of the 25 MetroWest communities.43 The following three times the survey was administered, 17 communities participated. Student participation in those 17 communities has ranged yearly from 88.8% to 89.6%, translating into an annual study population between 16 385 and 17 089 students. The grade and gender distributions of the participants that completed the survey each year have remained consistently similar.44

Presently, both middle- and high-school students in all 25 MetroWest communities are surveyed, totaling approximately 42 000 students.45 Thus, the MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey is one of the largest regional censuses of youth risk behavior in the country, costing MetroWest approximately $500 000 every time it is administered. While MetroWest receives aggregate data encompassing all 25 towns, only the school superintendent of each respective community receives individual district-level data. The superintendent retains the option of deciding how and in what format the data will be disseminated.46

DATA SUPPORTING TOBACCO 21

After multiple years of administration of the MetroWest Adolescent Health Survey, an observable trend became apparent. Every year the survey was conducted, the Needham data indicated a noticeable decline in rates of high-school tobacco use. The Needham Health Department posted a snapshot of these data to its Web site, displaying Needham High School smoking rates.47 In 2014, Winickoff et al. published a preliminary analysis of these Needham data in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled, “Tobacco 21—An Idea Whose Time Has Come.”48

Outside interest in the MetroWest data increased dramatically as word of this trend spread. Initially, MetroWest and the Education Development Center refused to release detailed comparison data for the other 16 school systems or allow outside analysis of the evidence, citing contractual privacy concerns. Recognizing the importance of these data to future public health efforts, Robert Crane, MD, president of the Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation, proposed to solicit all 17 MetroWest school districts for permission to release the data. At this point, the Education Development Center agreed to conduct and release an analysis of the MetroWest surveys’ findings.49

To compare Needham youth smoking trends with trends in the 16 surrounding communities, Education Development Center Project Director Shari Kessel Schneider and others conducted pooled cross-sectional analyses of the data. They published their results in 2015 in the article, “Community Reductions in Youth Smoking After Raising the Minimum Tobacco Sales Age to 21.”50

As stated in both the 2014 New England Journal of Medicine publication by Winickoff et al. and the 2015 analysis by Schneider et al., in 2006 rates of youth smoking did not significantly differ between Needham and the 16 surrounding communities. However, the data suggest that overall rates of smoking among youths in Needham then declined from 13% in 2006 to 6.7% in 2010—a 49% reduction in smoking rates. In the 16 comparison communities, smoking rates among youths declined from 15.0% to 12.4% during the same time period. This suggests that, from 2006 to 2008 and then again from 2008 to 2010, smoking rates declined at a much greater rate in Needham than in surrounding communities.51

From 2010 to 2012, the decline in Needham’s 30-day youth smoking rates exceeded that of all 16 surrounding communities. Notably, during the same period, alcohol consumption in the same Needham population declined very slightly, at a rate similar to that of the 16 surrounding communities.52

Data collected and analyzed regarding smoking rates in Needham after the town implemented the Tobacco 21 policy point to a specific and rapid decline in rates of tobacco use among adolescents. As Schneider states, “the data . . . clearly show that something different was going on in Needham.”53 Beyond serving as a reminder of the potential impact that individuals, boards of health, and thoughtfully devised policies can have on public health outcomes, the data suggested that Tobacco 21 could prove to be an effective antismoking public health strategy. Importantly, the publication of the Needham data accelerated the policy’s spread around the state and nation.

THE TOBACCO 21 MOVEMENT GAINS MOMENTUM

Although Needham implemented the Tobacco 21 policy in 2005, it was not until seven years later that any other town in the United States changed its minimum legal age of access from 18 to 21 years. As Brownson et al. suggest, numerous factors may influence whether an implemented policy is disseminated to other locales, as well as the rate at which dissemination may occur.54 In the case of Tobacco 21, the initial absence of focused policy advocates and the early lack of rigorous data supporting the new legislation’s efficacy likely slowed its spread.

However, in 2012, two pediatricians began to champion the Massachusetts Tobacco 21 movement—Lester Hartman, MD, MPH, and Jonathan Winickoff, MD, MPH. Prompted by their efforts, Tobacco 21 gradually gained statewide momentum, before beginning to spread nationally. From 2012 to 2013, seven towns in Massachusetts passed Tobacco 21 legislation, followed in the next six years by more than 160 additional Massachusetts towns, 450 counties and cities nationwide, and 14 states.55

Hartman first heard about Tobacco 21 after its passing in his hometown of Needham.56 Impressed by the policy’s impact on the prevention of smoking in young adults, Hartman concluded that, although it would be challenging, the most effective way to spread the Tobacco 21 policy throughout Massachusetts would be to advocate at local board of health meetings in towns throughout the state. He encouraged Walpole, Massachusetts, to move to 19 years, but immediately hit a dead end. He was not received well by the Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program, which initially debated against his perspective at Massachusetts Board of Health meetings. In hindsight, Hartman acknowledges that the Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program was likely concerned that his proposal would distract from grants that the state tobacco control program prioritized.57

Although Winickoff had been aware of the idea of Tobacco 21 for years before meeting Hartman, the possibility of making this policy change had never seemed feasible to him. Yet, when Hartman approached him in 2012, Winickoff was intrigued. As Winickoff explains,

When we look at how hard it is to change youth tobacco behavior once it’s initiated, it did seem like an obvious place to put our energy. We saw it as a way for us to help communities protect themselves against the number-one cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. As pediatricians, we felt invested in the health of children and we thought it was a great way for us to give back to the community.58

Although Needham had raised the tobacco sales age to 21 years without having access to outcome data, the doctors realized that they would need hard evidence supporting the effectiveness of the policy to convince other towns to make a similar change. Winickoff began to work with Hartman to develop a specific advocacy strategy (see the box on page 1544) and talking points that were scientific and rigorous, based upon data on age of youth smoking initiation, the neuroscience of the developing brain, tobacco access laws in other countries, and a mathematical model of the potential effect of raising the tobacco sales age to 21 years.60

Strategies and Operationalization for Public Health Advocacy at Local Boards of Health.

| Strategy Type | Operationalization |

| Local change agent | Recruit respected members of local community who can use specific vignettes to illustrate the importance of proposed law to testify at local board of health meetings. Includes nurses, pediatricians, teachers, etc. |

| Geographic proximity | Enlist board members and leaders from towns that have already passed the proposed law to approach bordering locations yet to pass. Work with smaller, more progressive border towns of major cities to pass the law first, to “surround” locations where passage might be more challenging. |

| Simple messaging | Develop a one-pager with the key arguments for the proposed law concisely summarized. Poll towns asking if they would like more information regarding the law. Start advocacy with towns expressing greatest levels of interest. |

| Youth advocacy | Work with youth advocates, such as high-school and college students affected by the proposed law, to advocate passage. |

| Inoculation against counterarguments | Understand the most common counterarguments and preempt them with opposing counterarguments research and data. |

| Press and media59 | Develop op-eds and contact the press about meetings to provide local coverage. |

In 2012, the two doctors began to approach boards of health together as a team and quickly proved successful. The pair campaigned at the boards of health of Canton and Sharon, Massachusetts, respectively, both of which passed Tobacco 21 legislation in 2012. In early 2013, five other Massachusetts towns followed.61 As Tobacco 21 momentum continued to grow, the movement also began to spread to cities and towns beyond Massachusetts, and the movement received endorsements from organizations such as Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, the Truth Initiative, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Heart Association.

In November 2013, the Big Island of Hawaii passed Tobacco 21 legislation, having been introduced to the policy by Crane that year.62 In January 2016, Hawaii then became the first state in the nation to raise the legal tobacco sales age to 21 years.

In 2013, the City of New York became the first large city to pass Tobacco 21 regulations. Before the passing of the policy in New York City, Hartman and Winickoff made a deliberate effort to work under the radar, hoping to see multiple towns pass the legislation before having tobacco companies recognize and oppose their strategy. When New York City looked to make the change to Tobacco 21, the Health Department reached out to Hartman and Winickoff, requesting data and testimonials in support of the policy change.63

While extremely beneficial to the overall Massachusetts local movement, once New York City passed, Hartman and Winickoff’s “under-the-radar” strategy was finished.64 A noticeable increase in Big Tobacco (Altria) attendance was now apparent at local board meetings. Convenience store owners would additionally testify at board meetings, speaking under the tobacco industry’s guidance and at times as surrogates for Big Tobacco representatives.65 Pushback from the tobacco industry and product retailers emanated from self-serving economic concerns. As a consequence, board of health members and legislators had to choose between protecting tobacco company profits and affiliated business interests or protecting the public health of their communities.

Despite the burgeoning spread of the Tobacco 21 movement throughout Massachusetts, with 351 towns in the state, the doctors began to realize the scope of the challenge ahead. As Hartman explains, a move to 21 years requires at least two or three meetings. New regulations are first introduced; a public hearing may occur; and the regulations are then voted on by the board.66 Therefore, concurrent with ongoing local efforts, Hartman and Winickoff met with Massachusetts state representatives to craft bills to implement statewide Tobacco 21 legislation. These statewide bills failed in two consecutive legislative cycles, primarily because of the tobacco industry’s strong lobbying efforts. However, in 2018, a third attempt at passage of a statewide Tobacco 21 bill in Massachusetts was successful.

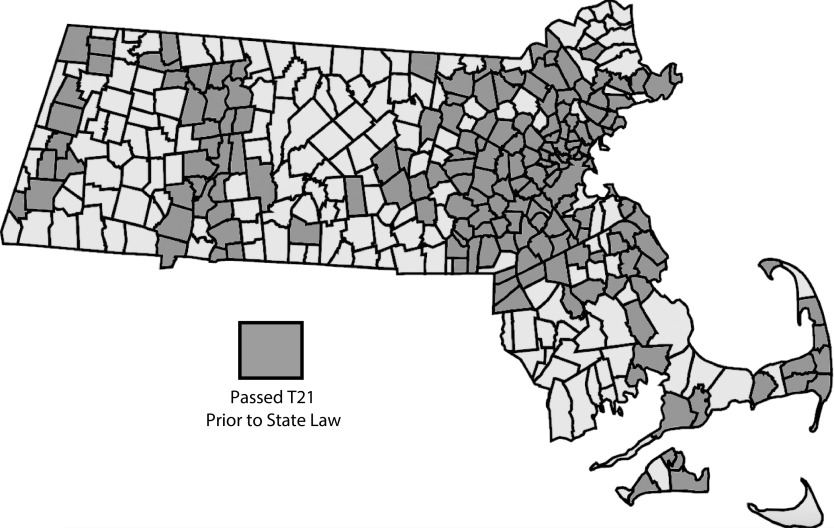

In May 2018, Tobacco 21 legislation passed in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, before passing in the Senate the following month. On July 27, 2018, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed Tobacco 21 into state law. As of January 2019, the legal minimum age for the sale of tobacco and nicotine products in Massachusetts is officially 21 years.67 In the six years before the signing of this policy into law, between 2012 and 2018, more than 175 Massachusetts towns, comprising more than 70% of the Massachusetts population, had adopted Tobacco 21 legislation (Figure 2).68

FIGURE 2—

Massachusetts Towns That Passed Tobacco 21 (T21) Legislation Before the Passing of Statewide Legislation: 2003–2018

Source. Courtesy of Patrick McKenna.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Nationwide data underscore the importance of the Tobacco 21 movement. Tobacco 21 laws now cover more than 100 million Americans across the United States. Of the 14 states that have passed the legislation, nine have followed the strategy of first passing Tobacco 21 in towns and cities at the local level before crafting and passing a statewide bill. The federal government has also begun to consider adopting this law, as the first federal Tobacco 21 legislation was introduced in Congress on September 20, 2015.69 Research suggests that the American public overwhelmingly supports this legislation. According to recent surveys, approximately three quarters of American adults and adolescents favor raising the tobacco age of sale to 21 years, including 7 in 10 smokers.70 It is important that Congress enact Tobacco 21 legislation that is absent special interest provisions that benefit the tobacco industry.

The National Academy of Medicine estimates that, once passed, nationwide Tobacco 21 legislation will result in 249 000 fewer premature deaths, 45 000 fewer deaths from lung cancer, and 4.2 million fewer lost life-years among Americans born between 2010 and 2019.71 The compelling National Academy of Medicine model strongly suggests that Tobacco 21 is an important and effective tobacco control policy. Wider adoption of Tobacco 21 and implementation of strict compliance regulations would dramatically prevent smoking initiation, improve health outcomes, reduce health care costs, and save lives. As exemplified by the Tobacco 21 movement, the model of initial local action, followed by local spread and state-level action, in conjunction with national advocacy can work effectively to promote public health in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lester J. Hartman for his support and mentorship and Henry K. Philofsky for his helpful insights. We are grateful to Alan Brandt for his thoughtful feedback. We also thank all those interviewed throughout the research process, including past and present members of the Needham Board of Health, town selectmen, Janice Berns, Timothy McDonald, D. J. Wilson, Martin Cohen, and Shari Kessel Schneider. We thank each of the interviewees for their honesty, availability, and willingness to share their perspectives on the early history of Tobacco 21.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Crane is founder and president of both the Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation and its advocacy arm, Tobacco 21. Both organizations work toward prevention solutions for adolescent nicotine addiction with a focus on raising the minimum sales age for all nicotine and tobacco products to 21 years. He receives no salary or financial consideration for these efforts.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not needed as human research was not conducted. Conducted interviews were with professionals with historical knowledge of actual events and were absent personal details.

Footnotes

See also Ribisl and Mills, p. 1483.

ENDNOTES

- 1.Dorie E. Apollonio and Stanton A. Glantz, “Minimum Ages of Legal Access for Tobacco in the United States From 1863 to 2015. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303172. 106, no. 7 (2016): 1200–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “About Synar,” April 22, 2014, https://www.samhsa.gov/synar/about (accessed January 11, 2018)

- 3. Apollonio, “Minimum Ages,” 1204.

- 4. Philip Morris USA, “Five year plan 1986–1990,” March 1986, Bates no. 2044799001-2044799142, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dxd12a00 (accessed April 20, 2018)

- 5. Unknown author, “Discussion Draft Sociopolitical Strategy,” January 21, 1986, Philip Morris, Bates no. 2043440040-2043440049, https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=zswh0127 (accessed February 7 2018): 8.

- 6.Michael S. Givel and Stanton A. Glantz, “Tobacco Lobby Political Influence on US State Legislatures in the 1990s. Tobacco Control. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.124. 10, no. 2 (2001): 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Timothy McDonald. “Article 1: Regulation Affecting Smoking and the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products in Needham,” in Needham Tobacco Laws (Needham, MA: Needham Board of Health, 2013); Janice Berns, telephone interview by M. J. Reynolds, July 6, 2016.

- 8. Alan Stern, telephone interview by M. J. Reynolds, July 6, 2016.

- 9.DiFranza J. R., Brown L. J. “The Tobacco Institute’s ‘It’s the Law’ Campaign: Has It Halted Illegal Sales of Tobacco to Children? American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.9.1271. 82, no. 9 (1992): 1271–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peter Connolly, e-mail interview by M. J. Reynolds, July 20, 2016.

- 11. Berns, interview.

- 12. Stern, interview.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. Ibid.

- 16. Berns, interview.

- 17. D. J. Wilson, interview by M. J. Reynolds, June 10, 2016.

- 18. Berns, interview.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22. Stern, interview.

- 23. Ibid.; Berns, interview.

- 24. Stern, interview.

- 25. John Bulian, telephone interview by M. J. Reynolds, August 10, 2016.

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. Stern, interview.

- 28. “Notice to Retailers Re 2-03 BoH Meeting Raising Ages,” Janice Berns to Retail Tobacco Vendors of Needham (Needham, MA: Board of Health, February 27, 2003).

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. Berns, interview.

- 31. Timothy McDonald, interview by M. J. Reynolds, June 24, 2016.

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. NACS, “Convenience Stores Hit Record In-Store Sales in 2016,” April 5, 2017, http://www.convenience.org/Media/Press_Releases/2017/Pages/PR040517.aspx#.WwJCCNMvxp_ (accessed April 3, 2018)

- 34. McDonald, interview.

- 35.Ackerman A. et al. Reducing the Density and Number of Tobacco Retailers: Policy Solutions and Legal Issues. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw124. 19, no. 2 (2017): 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDonald, interview.

- 37. Berns, interview.

- 38. McDonald, interview.

- 39. Summary of tobacco age of sales compliance checks in Needham, Massachusetts, 1994–2016; e-mail communication from Timothy McDonald, Needham Public Health Director; August 1, 2018.

- 40. Martin Cohen, interview by M. J. Reynolds, June 9, 2016.

- 41. Ibid.

- 42. Ibid.

- 43.Kessel Schneider S. et al. “Community Reductions in Youth Smoking After Raising the Minimum Tobacco Sales Age to 21,”. Tobacco Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052207. 25, no. 3 (2016): 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ibid., 355.

- 45. Cohen, interview.

- 46. Ibid.

- 47. Lester Hartman, interview by M. J. Reynolds, July 8, 2016.

- 48.Winickoff Jonathan P., Gottlieb Mark, Mello Michelle M. “Tobacco 21—An Idea Whose Time Has Come. New England Journal of Medicine. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1314626. 370, no. 4 (2014): 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rob Crane, e-mail interview by M. J. Reynolds, June 2, 2016.

- 50. Schneider, “Community Reductions,” 355–359.

- 51. Ibid.; Winickoff, “Tobacco 21.”.

- 52. Schneider, “Community Reductions,” 356–357.

- 53. Shari Kessel Schneider, telephone interview by M. J. Reynolds, June 21, 2016.

- 54.Brownson R. C. et al. Getting the Word Out. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673. 24, no. 2 (2018): 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tobacco 21, “Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation,” https://tobacco21.org (accessed May 22, 2019)

- 56. Hartman, interview.

- 57. Ibid.

- 58. Jonathan Winickoff, telephone interview by M. J. Reynolds, September 2, 2016.

- 59.Lawrence Wallack, Dorfman Lori. Media Advocacy: A Strategy for Advancing Policy and Promoting Health. Health Education Quarterly. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. 23, no. 3 (1996): 293–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Winickoff, interview.

- 61. Hartman, interview.

- 62. Crane, interview.

- 63. Winickoff, interview.

- 64. Ibid.

- 65. Hartman, interview.

- 66. Ibid.

- 67. “Gov. Baker Signs Bill Raising Tobacco Purchasing Age to 21,” AP News, July 27, 2018, https://apnews.com/a66692f0974643c4ba70a95bbdc20990 (accessed July 31, 2018)

- 68. Tobacco 21, “Massachusetts,” https://tobacco21.org/state/massachusetts (accessed November 2, 2018)

- 69. Brian Schatz, S.2100 - 115th Congress (2017-2018), “Tobacco to 21 Act,” November 8, 2017, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2100 (accessed January 13, 2018)

- 70.Kowitt S. D. King B. A. Attitudes Toward Raising the Minimum Age of Sale for Tobacco Among US Adults. 4. Vol. 49. American Journal of Preventive Medicine; 2015. “Should the Legal Age for Tobacco Be Raised? Results From a National Sample of Adolescents,” Preventing Chronic Disease 14 (2017): e112; J. P. Winickoff et al., “Public Support for Raising the Age of Sale for Tobacco to 21 in the United States,” Tobacco Control 25, no. 3 (2016): 284–288; pp. 583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morain Stephanie R., Winickoff Jonathan P., Mello Michelle M. Have Tobacco 21 Laws Come of Age? New England Journal of Medicine. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1603294. 374, no. 17 (2016): 1601–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]