Abstract

Background

Periodontal disease and dental caries are highly prevalent oral diseases that can lead to pain and discomfort, oral hygiene and aesthetic problems, and eventually tooth loss, all of which can be costly to treat and are a burden to healthcare systems. Triclosan is an antibacterial agent with low toxicity, which, along with a copolymer for aiding retention, can be added to toothpastes to reduce plaque and gingivitis (inflammation of the gums). It is important that these additional ingredients do not interfere with the anticaries effect of the fluoride present in toothpastes, and that they are safe.

Objectives

To assess the effects of triclosan/copolymer containing fluoride toothpastes, compared with fluoride toothpastes, for the long‐term control of caries, plaque and gingivitis in children and adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (to 19 August 2013), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 7), MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to 19 August 2013), Embase via OVID (1980 to 19 August 2013), and the US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (clinicaltrials.gov) (to 19 August 2013). We applied no restrictions regarding language or date of publication in the searches of the electronic databases.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects triclosan/copolymer containing toothpastes on oral health.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the search results against the inclusion criteria for this review, extracted data and carried out risk of bias assessments. We attempted to contact study authors for missing information or clarification when feasible. We combined sufficiently similar studies in meta‐analyses using random‐effects models when there were at least four studies (fixed‐effect models when fewer than four studies), reporting mean differences (MD) for continuous data and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data.

Main results

We included 30 studies, analysing 14,835 participants, in this review. We assessed 10 studies (33%) as at low risk of bias, nine (30%) as at high risk of bias and 11 (37%) as unclear.

Plaque

Compared with control, after six to seven months of use, triclosan/copolymer toothpaste reduced plaque by 0.47 on a 0 to 5 scale (MD ‐0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.60 to ‐0.34, 20 studies, 2675 participants, moderate‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 2.17, representing a 22% reduction in plaque. After six to seven months of use, it also reduced the proportion of sites scoring 3 to 5 on a 0 to 5 scale by 0.15 (MD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.10, 13 studies, 1850 participants, moderate‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 0.37, representing a 41% reduction in plaque severity.

Gingivitis

After six to nine months of use, triclosan/copolymer toothpaste reduced inflammation by 0.27 on a 0 to 3 scale (MD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.21, 20 studies, 2743 participants, moderate‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 1.22, representing a 22% reduction in inflammation. After six to seven months of use, it reduced the proportion of bleeding sites (i.e. scoring 2 or 3 on the 0 to 3 scale) by 0.13 (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.08, 15 studies, 1998 participants, moderate‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 0.27, representing a 48% reduction in bleeding.

Periodontitis

After 36 months of use, there was no evidence of a difference between triclosan/copolymer toothpaste and control in the development of periodontitis (attachment loss) (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.27, one study, 480 participants, low‐quality evidence).

Caries

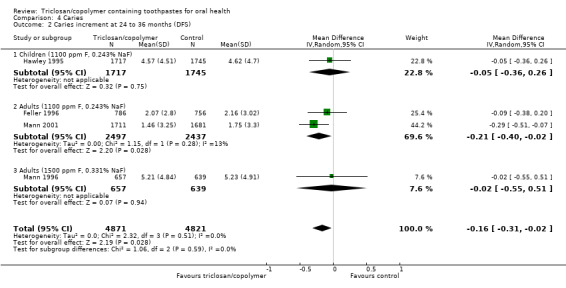

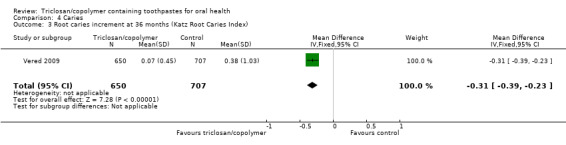

After 24 to 36 months of use, triclosan/copolymer toothpaste slightly reduced coronal caries when using the decayed and filled surfaces (DFS) index (MD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.31 to ‐0.02, four studies, 9692 participants, high‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 3.44, representing a 5% reduction in coronal caries. After 36 months of use, triclosan/copolymer toothpaste probably reduced root caries (MD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.23, one study, 1357 participants, moderate‐quality evidence).

Calculus

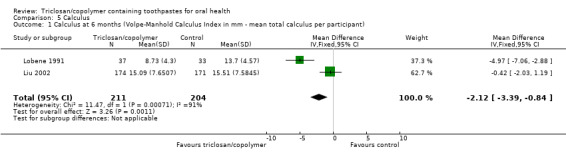

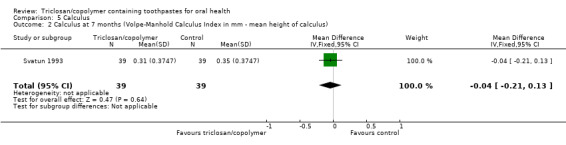

After six months of use, triclosan/copolymer toothpaste may have reduced the mean total calculus per participant by 2.12 mm (MD ‐2.12 mm, 95% CI ‐3.39 to ‐0.84, two studies, 415 participants, low‐quality evidence). The control group mean was 14.61 mm, representing a 15% reduction in calculus.

Adverse effects

There were no data available for meta‐analysis regarding adverse effects, but 22 studies (73%) reported that there were no adverse effects caused by either the experimental or control toothpaste.

There was considerable heterogeneity present in the meta‐analyses for plaque, gingivitis and calculus. Plaque and gingivitis showed such consistent results that it did not affect our conclusions, but the reader may wish to interpret the results with more caution.

Authors' conclusions

There was moderate‐quality evidence showing that toothpastes containing triclosan/copolymer, in addition to fluoride, reduced plaque, gingival inflammation and gingival bleeding when compared with fluoride toothpastes without triclosan/copolymer. These reductions may or may not be clinically important, and are evident regardless of initial plaque and gingivitis levels, or whether a baseline oral prophylaxis had taken place or not. High‐quality evidence showed that triclosan/copolymer toothpastes lead to a small reduction in coronal caries. There was weaker evidence to show that triclosan/copolymer toothpastes may have reduced root caries and calculus, but insufficient evidence to show whether or not they prevented periodontitis. There do not appear to be any serious safety concerns regarding the use of triclosan/copolymer toothpastes in studies up to three years in duration.

Plain language summary

Triclosan/copolymer containing toothpastes for oral health

Review question

This Cochrane Review has been conducted to assess the effects of using a toothpaste containing triclosan (an antibacterial ingredient) plus copolymer (an ingredient to reduce the amount of triclosan that is washed away by rinsing or saliva) plus fluoride (a mineral that prevents tooth decay) compared with using a fluoride toothpaste (without triclosan/copolymer) for oral health.

Background

Gum disease and dental decay are the main reasons for tooth loss. Unless brushed away, plaque (a sticky film containing bacteria) can build up on the teeth. This can lead to gingivitis (a swelling and redness of the gums that affects most adults), which, if not treated, can then lead to a more serious form of gum disease called periodontitis (which affects up to one out of every five adults aged 35 to 44 years worldwide). Periodontitis can cause pain, eating difficulties, an unpleasant facial appearance and eventually tooth loss. Plaque build‐up can also lead to tooth decay, a problem affecting up to 90% of schoolchildren in industrialised countries, and the majority of adults. Vast healthcare resources are used worldwide to treat gum disease and tooth decay, which are both preventable. Currently there is a lot of ongoing research into possible links between periodontitis and other medical conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, heart disease and also to the premature (too early) birth of underweight babies.

Adding an effective and safe antibacterial ingredient to toothpastes could be an easy and low‐cost answer to these problems. It is thought that triclosan could fight the harmful bacteria in plaque while also reducing the swelling that leads to serious gum disease. It is important that adding triclosan to fluoride toothpastes does not reduce the beneficial effects that fluoride has on preventing tooth decay.

Study characteristics

Authors from the Cochrane Oral Health Group carried out this review of existing studies and the evidence is current up to 19 August 2013. It includes 30 studies published from 1990 to 2012 in which 14,835 participants were randomised to receive a triclosan/copolymer containing fluoride toothpaste or a fluoride toothpaste that did not include triclosan/copolymer. The toothpaste that was used in most of the studies is sold by the manufacturer Colgate.

Key results

The evidence produced shows benefits in using a triclosan/copolymer fluoride toothpaste when compared with a fluoride toothpaste (without triclosan/copolymer). There was a 22% reduction in plaque, a 22% reduction in gingivitis, a 48% reduction in bleeding gums and a 5% reduction in tooth decay. There was insufficient evidence to show a difference between either toothpaste in preventing periodontitis. There was no evidence of any harmful effects associated with the use of triclosan/copolymer toothpastes in studies up to three years in length.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence relating to plaque and gingivitis was considered to be of moderate quality. The evidence on tooth decay was high quality, while the evidence on periodontitis was low quality.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Triclosan/copolymer/fluoride toothpaste compared with control for oral health | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults (children in 2 studies) Settings: clinical (schools in 2 studies) Intervention: triclosan/copolymer/fluoride toothpaste Comparison: control toothpaste (no triclosan/copolymer) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Triclosan/copolymer | |||||

|

Plaque at 6 to 7 months (Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index) (0 to 5 on an increasing scale) |

The mean plaque score for the control groups was 2.17 | The mean plaque in the intervention groups was 0.47 lower (0.60 to 0.34 lower) | 2675 (20 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | This evidence was supported by the results using the Plaque Severity Index (proportion of surfaces scoring > 3 on the Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index) at 6 to 7 months The mean plaque severity in the intervention groups was 0.15 lower (0.20 to 0.10 lower) than the control group mean score of 0.37. These results were based on 1850 analysed participants in 13 studies and we assessed the quality of the evidence (GRADE) as: ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

|

|

Gingivitis at 6 to 9 months (Löe‐Silness Gingival Index) (0 to 3 on an increasing scale) |

The mean gingivitis score for the control groups was 1.22 | The mean gingivitis in the intervention groups was 0.27 lower (0.33 to 0.21 lower) | 2743 (20 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | This evidence was supported by the results using the Gingivitis Severity Index (proportion of sites bleeding, i.e. 2 or 3 on the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index) at 6 to 7 months The mean gingival bleeding in the intervention groups was 0.13 lower (0.17 to 0.08 lower) than the control group mean score of 0.27. These results were based on 1998 analysed participants in 15 studies and we assessed the quality of the evidence (GRADE) as: ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea |

|

| Periodontitis at 36 months (attachment loss > 0 mm) | 249 per 1000 | 229 per 1000 (167 to 316) |

RR 0.92 (0.67 to 1.27) |

480 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | |

|

Coronal caries increment at 24 to 36 months (decayed filled surfaces ‐ DFS) (caries increment is the change from baseline to follow‐up) |

The mean DFS score for the control groups was 3.44 | The mean DFS in the intervention groups was 0.16 lower (0.31 to 0.02 lower) | 9692 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | The mean increment of the decayed filled teeth (DFT) index at 30 to 36 months in the intervention groups was 0.06 lower (0.14 lower to 0.02 higher) than the control group mean score of 1.63. These results were based on 6300 analysed participants in 3 studies and we assessed the quality of the evidence (GRADE) as: ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high For root caries, the mean increment of the Katz Root Caries Index at 36 months in the intervention group was 0.31 lower (0.39 to 0.23 lower) than the control group mean score of 0.38. These results were based on 1357 analysed participants in 1 study and we assessed the quality of the evidence (GRADE) as: ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec |

|

| Calculus at 6 months (Volpe‐Manhold Calculus Index in mm ‐ mean total calculus per participant) | The mean calculus score for the control groups was 14.61 | The mean calculus in the intervention groups was 2.12 lower (3.39 to 0.84 lower) | 415 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | ||

| Adverse effects | 22 studies reported that there were no adverse effects in either the experimental or control arm of the study. 1 study reported mild adverse effects but not by group/arm. The remaining 7 studies did not report any information on adverse effects | |||||

| CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aThese 4 meta‐analyses all had very high heterogeneity (I2 > 90%), however, we only downgraded by 1 point due to the consistency of the effects favouring triclosan/copolymer. The downgrading for was due to the prediction intervals slightly overlapping 0 (the line of no effect). bSingle study at high risk bias with 95% CI including both an effect favouring the intervention and the control. cSingle study (but with large sample size) at high risk bias. d2 studies (1 at high and 1 at unclear risk of bias) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 91%).

Background

Description of the condition

Periodontal disease and dental caries account for the vast majority of tooth loss (Neely 2005). The primary causative factor for both diseases is the accumulation of dental plaque, a microbial biofilm on the surface of the teeth, which the body reacts to with an inflammatory response (Marsh 1994). Plaque can be present, with its microbial components stable and the gums healthy in a state of microbial homeostasis, but changes in the plaque microflora can affect this equilibrium, leading to a composition that favours disease (Dalwai 2006; Marsh 2006). In gingivitis, a form of gum disease characterised by redness, irritation and inflammation of the gums (Mayo 2010), it has been shown that a significant alteration in plaque composition is that which leads to a reduction in Streptococcus spp, which tends to make up the majority of the microflora in disease‐free individuals, and an increase in Actinomyces spp (Dalwai 2006).

Gingivitis, on the scale of periodontal diseases, is less severe than periodontitis, with most people being unaware of its presence due to lack of pain, leading to underestimation by dental practitioners (Lang 2009). Furthermore, it was discovered as early as 1965 that gingivitis was reversible in a study where participants ceased all oral hygiene measures, which led to gingivitis, and subsequent reinstatement of oral care resulted in a return to gingival health (Löe 1965). However, gingivitis can lead to severe and irreversible periodontal diseases such as periodontitis (Lang 2009), and such diseases can have a significant effect on quality of life, causing eating difficulties, pain, problems with facial aesthetics and tooth loss (Needleman 2005). Studies have suggested there may be an association between periodontitis and a number of systemic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases and also conditions such as preterm birth, leading to underweight babies (Seymour 2007; Simpson 2010).

Studies suggest that 50% to 90% of adults in the UK and USA have gingivitis (NICE 2012), with some studies estimating prevalence to be as high as 94% in the USA (Li 2010), and 98% in China (Zhang 2010). In other less economically developed countries, studies have estimated prevalences of 76% in Jordan (Ababneh 2012), and 96% in Mexico (García‐Conde 2010). The fact that 15% to 20% of adults aged 35 to 44 years have severe periodontal disease demonstrates the burden of this health problem (WHO 2012).

Dental caries (tooth decay) is a localised chemical dissolution of the surface of the tooth due to metabolic events occurring in dental plaque, and the longer the plaque remains on the tooth surface, the more likely the manifestation of caries (Fejerskov 2008; Selwitz 2007). An increase in the consumption of fermentable carbohydrates lowers the pH of plaque, which leads to favourable conditions for acid‐tolerating (and acidogenic) bacteria such as mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, which dominate the microflora thus tipping the balance from a state of equilibrium to demineralisation, potentially resulting in cavities (Marsh 2006). This mechanism is self perpetuating as an increase in these bacteria leads to a faster rate of acid production, and enhancement of the demineralisation process (Marsh 2006).

It is estimated that the prevalence of dental caries ranges from 60% to 90% in schoolchildren of most industrialised countries, and it affects the large majority of adults (Petersen 2003). This is despite the significant decline in the severity and prevalence of caries seen in such countries since the middle of the last century (Blinkhorn 2009; Marthaler 2004; Selwitz 2007).

Description of the intervention

Toothbrushing is the main intervention universally performed in the home in order to remove and control the dental biofilm mechanically and prevent caries and periodontal disease, but for many adults toothbrushing alone is inadequate for this purpose (Alexander 2012; Morris 2001). Standard practice is for toothbrushing to be carried out using a fluoride toothpaste yet, while such treatment has been instrumental in the approximate 50% reduction in caries in the populations of industrialised western countries in the latter half of the twentieth century, it has contributed little to reducing periodontal diseases (Blinkhorn 2009). As such, it has been recommended that adults should incorporate the use of an antiplaque/antigingivitis agent into their routine of oral care (Gunsolley 2006).

Triclosan is a broad‐spectrum antibacterial agent with low toxicity that can be added to toothpastes in order to reach large numbers of the population (Blinkhorn 2009). While chlorhexidine may have a greater antimicrobial effect, triclosan is more compatible with other typical toothpaste ingredients, with the added advantage of not having an unpleasant taste (Blinkhorn 2009). However, there is no evidence of effectiveness for products containing triclosan alone in the control of caries or plaque/gingivitis (Gunsolley 2006), hence it is mostly used in conjunction with a copolymer (e.g. polyvinylmethyl ether maleic acid ‐ PVM/MA), which facilitates uptake and retention of the triclosan to enamel, oral epithelial cells and plaque (Ciancio 2007). There is some evidence to show that this combination might be effective in the control of plaque and gingivitis (Davies 2004; Gunsolley 2006).

How the intervention might work

Triclosan is an antibacterial agent that affects bacterial growth; it is thought to exert this influence via the inhibition of key bacterial metabolic pathways. This action is thought to reduce the bacterial load in the plaque biofilm, which in theory could control caries and gingivitis. However, previous work has suggested that triclosan may go further than simply reducing plaque (Lindhe 1993), and that it reduces gingival inflammation, which is a necessary precursor to the development of more severe periodontal disease (Gunsolley 2006). A possible explanation for this reduction in inflammation is that the cytokine TNFα (tumour necrosis factor alpha), which is involved in systemic inflammation, augments both the expression of messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and protein levels of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase‐1 (mPGES‐1). These are both important in the biosynthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in gingival fibroblasts, and it is thought that triclosan inhibits the production of these building blocks of PGE2, thus having an anti‐inflammatory effect (Mustafa 2005).

As caries develop in the dental biofilm, as described above, it may be possible that the antibacterial effect of triclosan, in reducing plaque, disrupts the biofilm and prevents the progression of caries.

Why it is important to do this review

As the prevalence figures above illustrate, periodontal diseases are widespread and, in the USA in 1999, it was estimated that USD 14.4 billion were spent on periodontal and preventive procedures, with USD 4.4 billion of this total being spent on periodontal services alone (Brown 2002). Caries is also a highly prevalent disease and, as it is initially reversible, it has been recommended that the focus of care should be on early preventive action (Pitts 2004). Poor oral health will inevitably affect overall health and well‐being, indeed one study demonstrated that 90% of participants reported feeling that their level of oral health had an impact on their overall quality of life (Needleman 2004). With these negative economic, social and health consequences of caries and periodontal diseases, triclosan, if found to be both effective and safe, may be a low‐cost, simple, non‐invasive and far‐reaching solution globally if added to more fluoride toothpastes.

A systematic review by Davies et al and a meta‐analysis by Gunsolley, both of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), have both shown that triclosan/copolymer toothpastes might be effective against plaque and gingivitis when compared with standard fluoride toothpastes (Davies 2004; Gunsolley 2006). However, it is now seven years since the most recent of these reviews was published, and neither review rigorously assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. Therefore, it is important and timely to conduct a Cochrane Review of triclosan/copolymer toothpastes in order to provide rigorous, up‐to‐date evidence to oral health practitioners and consumers, which takes into account the risk of bias of the studies that have been carried out on the topic. As with all consumer products, it is important to assess the safety of triclosan/copolymer toothpastes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of triclosan/copolymer containing fluoride toothpastes, compared with fluoride toothpastes, for the long‐term control of caries, plaque and gingivitis in children and adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of parallel or cross‐over design, irrespective of language or publication status. Cross‐over studies were eligible but would have required a sufficient washout period to prevent a carry‐over effect, due to the antimicrobial and anti‐inflammatory properties of triclosan, to allow for participants to return to conditions comparable to baseline. We set this period at a minimum of three weeks in accordance with Löe et al's classic experiment (Löe 1965). We only included studies of at least six months' duration (in terms of both use of the toothpaste and follow‐up), as recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in order to represent a person's normal usage more realistically (thus reducing any possible Hawthorne effect (where participants in the studies perform better oral hygiene measures than they normally would due to the knowledge that they are being assessed (McCarney 2007), which may be present in short‐term studies) and to assess long‐term effects (Gunsolley 2006). Therefore, by necessity, cross‐over studies would have to be a minimum of one year (plus washout period) in length. We included studies with and without baseline prophylaxes (scale and polish), but both groups had to have the same treatment, and it must have taken place at the start of both phases in a cross‐over study. We would have included cluster‐RCTs if any such studies existed. It would not be feasible to carry out split‐mouth studies on this topic, therefore, we excluded such designs.

Types of participants

We included RCTs of children or adults (in accordance with other Cochrane reviews, we classified all participants aged 16 years or less as children and those older than 16 years as adults). We excluded any studies including participants with periodontitis at baseline. We excluded studies where participants were selected due to a pre‐existing health condition (e.g. cancer, heart disease, diabetes). We excluded studies where the majority of participants had orthodontic appliances. We also excluded studies where participants were taking another prophylactic regimen for plaque/gingivitis (e.g. chlorhexidine mouthwash), unless this was only in one arm of the study and there was also a triclosan/copolymer/fluoride arm and a fluoride control arm. In this instance, we excluded the chlorhexidine arm and only used data from the eligible arms.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention: any fluoride toothpaste containing a triclosan/copolymer combination.

Comparator intervention: any fluoride toothpaste without triclosan.

We only included studies where toothbrushing was unsupervised to represent everyday use. We would have excluded any studies assessing caries if the toothpastes in each treatment arm contained a different concentration of fluoride.

Types of outcome measures

We only used outcome data at six months of follow‐up or longer.

Primary outcomes

Plaque levels measured using any appropriate scale.

Gingival health measured using any appropriate scale.

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of periodontitis.

Caries: a) new incidence, and b) caries increment ‐ change in decayed, missing and filled surfaces (DMFS/dmfs) index.

Calculus measured using any appropriate scale.

Adverse effects (e.g. taste disturbance, staining, allergic reaction, etc.).

Participant‐centred outcomes: a) participant‐assessed quality of life scores, and b) participant satisfaction with product.

Search methods for identification of studies

For the identification of studies included or considered for this review, we developed detailed search strategies for each database searched. We based these on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE (Appendix 1) but revised appropriately for each database to take account of differences in controlled vocabulary and syntax rules.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register (to 19 August 2013) (Appendix 2);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 7) (Appendix 3);

MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to 19 August 2013) (Appendix 1);

Embase via OVID (1980 to 19 August 2013) (see Appendix 4).

Searching other resources

We searched the US National Institutes of Health Trials Register for ongoing trials to 4 March 2013 (Appendix 5).

We only included handsearching done as part of the Cochrane Worldwide Handsearching Programme and uploaded to CENTRAL (see the Cochrane Masterlist for details of journals and issues searched to date).

We searched the reference lists of included studies to identify further possibly relevant studies.

We placed no restrictions on the language of publications when searching the electronic databases or reviewing reference lists in identified studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

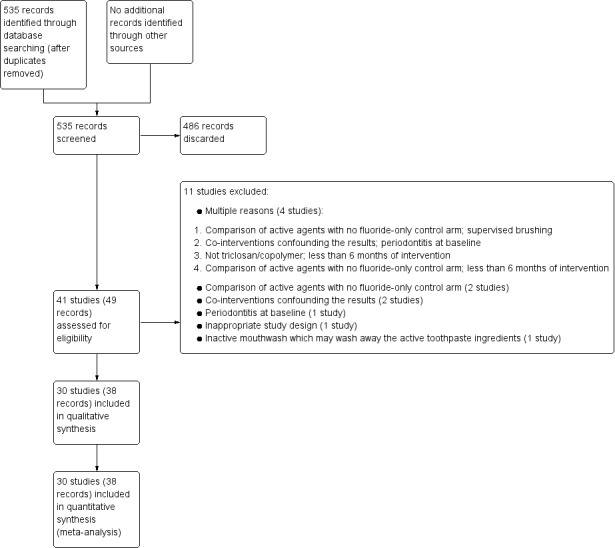

Two review authors screened the titles and abstracts of the list of studies identified by the searching process against the inclusion criteria of the review, independently and in duplicate, to identify eligible and potentially eligible studies. We obtained full‐text copies of all the identified studies, and also of studies with insufficient information in the title/abstract to make a decision on eligibility. Two review authors further assessed the full‐text copies, independently and in duplicate, to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. We contacted study authors for clarification or missing information where necessary and feasible. We linked multiple reports of the same study together under one single study title. We resolved any disagreements on eligibility through discussion but, if this had not been possible, an experienced member of the Cochrane Oral Health Group editorial team would have been consulted to achieve consensus. We recorded any studies failing to meet the inclusion criteria at this stage , along with reasons for exclusion, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, and summarised in the Main results section under the subheading Description of studies > Excluded studies. We have summarised this process in the 'Study flow diagram' (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data from the included studies, independently and in duplicate, using a specially designed data extraction form that was piloted on a small sample of studies. We contacted study authors for clarification or missing information where necessary and feasible. We resolved any disagreements through discussion but, if this had not been possible, an experienced member of the Cochrane Oral Health Group editorial team would have been consulted to achieve consensus. We recorded the extracted data in a spreadsheet, in order to facilitate summarising information in the Main results section under the subheading Description of studies > Included studies.

We recorded the following data for each included study, which was tabulated in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Year of publication, country of origin, study design, number of centres, source of study funding, recruitment period.

Details of the participants including demographic characteristics and criteria for inclusion and exclusion, any relevant information on plaque and gingivitis levels at baseline, numbers randomised to each treatment group, and numbers analysed.

Details of the type of intervention/comparator, timing, dose, and duration, and baseline prophylaxes (scale and polish).

Details of the outcomes reported, including method of assessment, and time(s) assessed.

Sample size calculations.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors assessed the risk of bias of all included studies, independently and in duplicate, using The Cochrane Collaboration's domain‐based, two‐part tool as described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We contacted study authors for clarification or missing information where necessary and feasible. We resolved any disagreements on risk of bias through discussion but, if this had not been possible, an experienced member of the Cochrane Oral Health Group editorial team would have been consulted to achieve consensus. A 'Risk of bias' table was completed for each included study. For each domain of risk of bias, we first described what was reported to have happened in the study in order to provide a rationale for the second part, which involved assigning a judgement of 'Low risk' of bias, 'High risk' of bias, or 'Unclear risk' of bias.

For each included study, we assessed the following seven domains of risk of bias.

Random sequence generation (selection bias): use of simple randomisation (e.g. random number table, computer‐generated randomisation, central randomisation by a specialised unit), restricted randomisation (e.g. random permuted blocks), stratified randomisation and minimisation were assessed as low risk of bias. Other forms of simple randomisation, such as repeated coin tossing, throwing dice or dealing cards, were also considered as low risk of bias (Schulz 2002). If a study report used the phrase 'randomised' or 'random allocation' but with no further information, we assessed it as unclear for this domain.

Allocation concealment (selection bias): use of centralised/remote allocation, pharmacy‐controlled randomisation (i.e. allocation of sequentially numbered toothpaste containers of identical appearance and weight) and sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes were assessed as low risk of bias. If a study report did not mention allocation concealment, we assessed it as unclear for this domain.

Blinding of participants (performance bias): as participants performed the intervention, we did not consider personnel blinding. If a study was described as double blind, we assumed that participants and outcome assessors were blinded. If blinding was not mentioned, we assumed that no blinding occurred and we assessed this domain as high risk of bias. It was not possible for a judgement of unclear risk of bias to be assigned for this domain.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): it should be possible to blind outcome assessors for the main outcomes of this review. If blinding was not mentioned we would have assumed that no blinding occurred and we would have assessed this domain as high risk of bias. It was not possible for a judgement of unclear risk of bias to be assigned for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): if 10% or less of randomised participants were excluded from the analysis, we assessed this as low risk of bias. However, when attrition was greater than 10%, assuming the missing participants in one group had a higher mean (e.g. gingivitis score) than those in the other group, as the attrition rate increased, so would the mean difference (MD) between groups, as described in Section 8.13.2.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This situation led to a judgement of high risk of bias if we believed that the attrition was high enough to have resulted in a distortion of the true intervention effect, or if there was considerably greater attrition in one group than another. If attrition was greater than 10%, but with the additional factors of not being reported by group and insufficient reporting of reasons for attrition, this led to a judgement of unclear risk of bias. If it was not clear from the study report how many participants were randomised into each group, we assessed it as unclear risk of bias for this domain.

Selective reporting (reporting bias): if the study either reported outcomes not stated a priori in the methods section (as it is unlikely that the studies have published protocols) or did not report outcomes stated in the methods section, we assessed this as high risk of bias. Furthermore, if the study reported in the methods section that a particular scale would be used, but then a different one was used, we assessed it as high risk of bias; if it was not stated in the methods section, we would have assessed it as unclear risk of bias. If outcomes were reported with insufficient information to allow us to use it in a meta‐analysis (e.g. no information on variance), we assessed it as high risk of bias. Cross‐over studies that did not analyse paired data would have been assessed as high risk of bias. Cluster‐RCTs that did not take clustering effects into account would have been assessed as high risk of bias.

Other bias: any other potential source of bias that may feasibly alter the magnitude of the effect estimate (e.g. possible carry‐over effects in cross‐over studies, only first period data reported in cross‐over studies, incorrect analysis in cross‐over studies, baseline imbalances in potentially important prognostic factors between intervention groups, randomisation by set block size in unblinded studies (or where blinding was broken) as this could enable prediction of future allocation (this is regardless of whether allocation concealment was adequate), and differential diagnostic activity by outcome assessors).

We summarised the risk of bias as follows.

| Risk of bias | Interpretation | In outcome | In included studies |

| Low risk of bias | Plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results | Low risk of bias for all key domains | Most information is from studies at low risk of bias |

| Unclear risk of bias | Plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results | Unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains | Most information is from studies at low or unclear risk of bias |

| High risk of bias | Plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results | High risk of bias for one or more key domains | The proportion of information from studies at high risk of bias is sufficient to affect the interpretation of results |

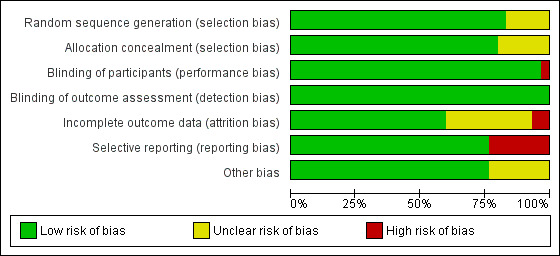

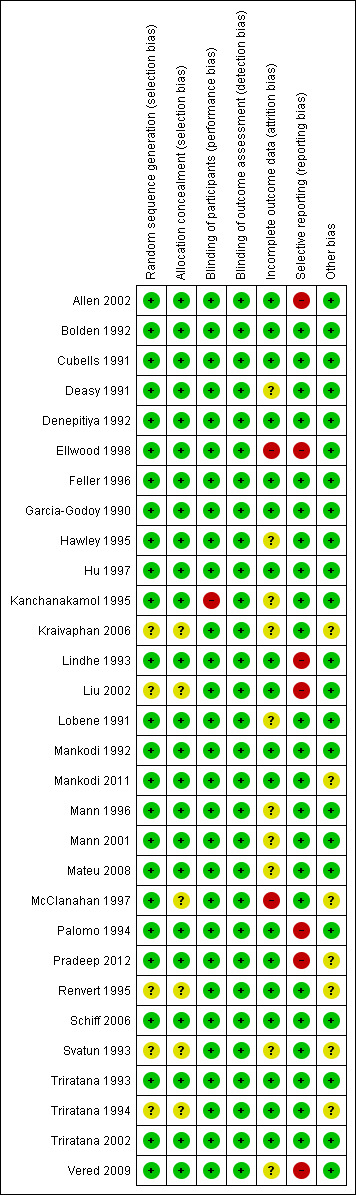

We present the 'Risk of bias' summary graphically by: a) proportion of studies with each judgement ('Low risk', 'High risk' and 'Unclear risk' of bias) for each risk of bias domain (Figure 2); b) cross‐tabulation of judgements by study and by domain (Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes (e.g. plaque/gingivitis scores), where studies used the same scale, we used the mean values and standard deviations reported in the studies in order to express the estimate of effect of the intervention as MD with 95% confidence interval (CI). Where different scales were used, we would have expressed the treatment effect as standardised mean difference and 95% CI.

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. attachment loss/no attachment loss), we expressed the estimate of effect of the intervention as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI.

For cross‐over studies, we would have extracted appropriate data following the methods outlined by Elbourne et al (Elbourne 2002), and we would have used the generic inverse variance method to enter log RRs or MD/standardised mean difference and standard error into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012).

Unit of analysis issues

The participant was the unit of analysis. Cross‐over studies should analyse data using a paired t‐test, or other appropriate statistical test, to take into account the two‐period nature of the data. Cluster‐RCTs should analyse results taking account of the clustering present in the data, otherwise we would have used the methods outlined in Section 16.3.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions in order to perform an approximately correct analysis (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted, where feasible, to contact the author(s) of studies to obtain missing data or for clarification. Where appropriate, we used the methods outlined in Section 7.7.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions in order to estimate missing standard deviations (Higgins 2011). We did not use any further statistical methods or carry out any further imputation to account for missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If meta‐analyses were performed, we assessed the possible presence of heterogeneity visually by inspecting the point estimates and CIs on the forest plots; if the CIs had poor overlap then heterogeneity was considered to be present. We also assessed heterogeneity statistically using a Chi2 test, where a P value < 0.1 indicated statistically significant heterogeneity. Furthermore, we quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. A guide to interpretation of the I2 statistic given in Section 9.5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions is as follows (Higgins 2011):

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Assessment of reporting bias within studies has already been described in the section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.

Reporting biases can occur when reporting (or not reporting) research findings is related to the results of the research (e.g. a study that did not find a statistically significant difference/result may not be published). Reporting bias can also occur if ongoing studies are missed (but that may be published by the time the systematic review is published), or if multiple reports of the same study are published, or if studies are not included in a systematic review due to not being reported in the language of the review authors. If there were more than 10 studies included in a meta‐analysis, we assessed the possible presence of reporting bias by testing for asymmetry in a funnel plot. If present, we would have carried out statistical analysis using the methods described by Egger 1997 for continuous outcomes and Rücker 2008 for dichotomous outcomes. However, we did attempt to limit reporting bias in the first instance by conducting a detailed, sensitive search, including searching for ongoing studies, and any studies not reported in English were translated by a member of The Cochrane Collaboration.

Data synthesis

We only carried out a meta‐analysis where studies of similar comparisons reported the same outcomes. We combined MDs (we would have used standardised mean differences where studies had used different scales) for continuous outcomes, and would have combined RRs for dichotomous outcomes, using a fixed‐effect model if there were only two or three studies, or a random‐effects model if there were four or more studies.

We would have used the generic inverse variance method to include data from cross‐over studies in meta‐analyses as described in Section 16.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Elbourne 2002; Higgins 2011). Where appropriate, we would have combined the results from cross‐over studies with parallel group studies, using the methods described by Elbourne et al (Elbourne 2002). We would have reported the results from studies not suitable for inclusion in a meta‐analysis in an additional table.

Although not stated in the protocol, in order to provide a more complete summary of random‐effects meta‐analyses with high heterogeneity, we calculated 95% prediction intervals where appropriate (Riley 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there were sufficient studies, we carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Baseline prophylaxes (scale and polish) versus none.

Children versus adults.

Different fluoride concentrations (only for caries outcome).

Initial plaque and inflammation levels.

We would have carried out subgroup analyses according to study design (parallel/cross‐over/cluster‐RCTs).

Sensitivity analysis

In order to ensure our conclusions were robust, we carried out sensitivity analysis (where there were sufficient studies for each outcome) by excluding studies at high and unclear risk of bias.

Presentation of main results

We produced a 'Summary of findings' table for main outcomes of this review using GRADEPro software. We assessed the quality of the body of evidence by considering the overall risk of bias of the included studies, the directness of the evidence, the inconsistency of the results, the precision of the estimates, the risk of publication bias, the magnitude of the effect and whether or not there was evidence of a dose response. We categorised the quality of the body of evidence for each of the primary outcomes as high, moderate, low or very low.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The searches resulted in 535 references following de‐duplication. Two review authors screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria for this review, independently and in duplicate, discarding 486 references in the process. We obtained full‐text copies of the remaining 49 references and examined them independently and in duplicate, excluding 11 studies at this stage. Eight of the remaining 38 references were abstracts and were subsequently linked to other references. Therefore, 30 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. This process is presented diagrammatically in Figure 1.

Included studies

Characteristics of the trial designs and settings

Thirty studies met the inclusion criteria for this review and were included (see Characteristics of included studies tables). All studies were of parallel group design, 20 of which had two arms, seven had three arms (Allen 2002; Feller 1996; Liu 2002; Mann 1996; McClanahan 1997; Pradeep 2012; Schiff 2006), and three had four arms (Palomo 1994; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993). However, two of the three‐arm studies did not report any details regarding the third arm, stating only that it was an experimental toothpaste, the results of which bore no impact on the comparison between the two reported toothpastes (Feller 1996; Mann 1996). Eleven studies were conducted in the USA; five in Thailand; three in Israel; two in Spain; two in the UK; one in each of the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, India, Sweden, and Norway; and two were unclear as the authors were from more than one country and the setting was not explicitly stated (Hu 1997; Lindhe 1993). The setting of the studies was poorly reported, with 17 studies not mentioning the type of setting, seven stating the phrase 'clinical facility' (Allen 2002; Cubells 1991; Mankodi 1992; Mankodi 2011; Mann 1996; Mateu 2008; Palomo 1994), two were conducted in high schools (Ellwood 1998; Hawley 1995), one appeared to be in a university setting (Triratana 2002), one was in a dental college/research institute (Pradeep 2012), one in an antenatal care unit (Kraivaphan 2006) and one was in a dental clinic (Feller 1996).

All studies were single‐centre, with two involving multiple high schools (Ellwood 1998; Hawley 1995), and two involving multiple communities across Israel (Mann 2001; Vered 2009). We report them as single‐centre studies in that they appear to have followed a single study protocol administrated by a single centre/group. Eight studies explicitly stated Colgate Palmolive as a source of support (Hawley 1995; Kanchanakamol 1995; Mankodi 1992; Mankodi 2011; Mateu 2008; Schiff 2006; Triratana 2002; Vered 2009), with a further 15 studies not explicitly stating this, but being clearly associated with Colgate Palmolive through authorship (Allen 2002; Bolden 1992; Cubells 1991; Deasy 1991; Denepitiya 1992; Ellwood 1998; Feller 1996; Garcia‐Godoy 1990; Hu 1997; Lindhe 1993; Lobene 1991; Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Palomo 1994; Triratana 1993). One study explicitly stated Procter & Gamble as a source of support (Liu 2002), with one more study being associated through authorship (McClanahan 1997). One study was associated through authorship to Unilever (Svatun 1993), while one more study stated that LB Aroma provided the toothpastes (Pradeep 2012). Only three studies were potentially truly independent (Kraivaphan 2006; Renvert 1995; Triratana 1994).

Only three studies mentioned sample size calculations. One of these studies achieved the required sample size even after attrition was taken into account (Hawley 1995). Another study performed a sample size calculation but did not report the results of the calculation and it was unclear whether or not the required sample size was achieved (Pradeep 2012). The sample size of the final study was informed by a previous study, stating that approximately 50 participants were required in each of the four arms, yet it was unclear whether this was achieved as the numbers in each arm ranged from 45 to 48 (Svatun 1993).

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 14,835 participants provided data for this review, with the numbers analysed in each study ranging from 54 to 3462. Only two studies were conducted on children (Ellwood 1998; Hawley 1995), both of which had a mean age of 12.7 years, and a range of 11 to 13 years. In the other 28 studies, the age range was 18 to 81 years, with the mean age ranging from 21.5 to 59. All studies had a greater proportion of females than males, except for one study (Schiff 2006). One study was conducted on pregnant women (Kraivaphan 2006).

For the 20 studies that assessed plaque using the Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, the mean baseline plaque score was 2.52.

For the 20 studies that assessed gingivitis using the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index, the mean baseline gingivitis score was 1.48.

For the four studies that assessed coronal caries, the three conducted on adults had a mean baseline decayed, filled tooth surfaces (DFS) score of 14.54, and the study on children had a mean baseline decayed, missing and filled tooth surfaces (DMFS) score of 5.4. A further study assessed root caries using the Katz Root Caries Index, and the mean baseline score was 0.97.

For the two studies that assessed calculus, using a comparable version of the Volpe‐Manhold Calculus Index, the mean baseline calculus score was 16.85 mm.

Characteristics of the interventions

In 23 studies, the intervention involved brushing the teeth with the assigned toothpaste, twice daily, for one minute each time. Three studies only specified brushing twice daily but did not state a duration of brushing (Ellwood 1998; Mann 2001; Svatun 1993), and another three stated neither frequency nor duration (Hawley 1995; Pradeep 2012; Renvert 1995). One further study only specified brushing twice daily, for one minute each time, in the triclosan/copolymer arm, while the control arm was instructed to follow their "normal oral hygiene procedure" (Kanchanakamol 1995). Eight studies explicitly stated that participants were asked to refrain from all other oral hygiene procedures (Allen 2002; Denepitiya 1992; Hu 1997; Kanchanakamol 1995; Mankodi 2011; Pradeep 2012; Schiff 2006; Triratana 2002), while one study merely stated that the "use of interdental cleaning devices was not advocated" (Lindhe 1993).

All studies had a triclosan/copolymer arm compared with a control arm. The toothpaste that was used in most of the studies is sold by the manufacturer Colgate. In 29 studies, it was clearly stated that the triclosan/copolymer concentration was 0.3% triclosan, 2% copolymer, but one study did not report the concentration of either ingredient (Pradeep 2012).

Twenty‐eight studies stated that the triclosan/copolymer arms also contained sodium fluoride, while one study only stated fluoride (Pradeep 2012), and another study did not clearly report whether or not it contained fluoride in any form (Kraivaphan 2006). The concentration of sodium fluoride in the triclosan/copolymer arms was 0.243% (1100 parts per million (ppm) fluoride), except for one study, which had a concentration of 0.221% (1000 ppm fluoride) (Kanchanakamol 1995), and another of 0.331% (1500 ppm fluoride) (Mann 1996). Twenty‐seven control arms involved brushing with a fluoride‐only toothpaste, while two studies stated placebo (Kraivaphan 2006; Pradeep 2012), and one study stated "normal oral hygiene procedure" (Kanchanakamol 1995). It is possible that the control arm in these three studies contained fluoride‐only toothpastes but, if this was not the case, we did not consider this to be important as the studies were assessing plaque and gingivitis rather than caries. Of the 27 studies that explicitly reported the control arm to be a fluoride‐only toothpaste, two were in the form of sodium monofluorophosphate, one of which was a 0.8% concentration that had an approximate equivalent fluoride content of 0.243% sodium fluoride in the triclosan/copolymer arm (Svatun 1993), while the other study did not state the concentration (Renvert 1995). Twenty‐four of the remaining studies contained 0.243% sodium fluoride, while one study contained 0.331% (Mann 1996).

Twenty studies reported a baseline prophylaxis to remove plaque and thus assess the potential for triclosan/copolymer toothpastes to prevent plaque accumulation and its ability to reduce gingivitis. The remaining 10 studies did not have a baseline prophylaxis. However, of these, five studies were assessing caries (Feller 1996; Hawley 1995; Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Vered 2009), and one was assessing the development of periodontitis (Ellwood 1998). The remaining four studies were thus designed to assess the potential for triclosan/copolymer toothpastes to treat/reduce plaque and gingivitis (Lindhe 1993; Mankodi 2011; Triratana 1993; Triratana 2002).

In 21 studies, the duration of intervention was six months, with two studies having seven months of intervention (Garcia‐Godoy 1990; Svatun 1993), and one study, conducted on pregnant women, having nine months of intervention (including three months postpartum) (Kraivaphan 2006). In the remaining six studies, the duration of intervention was 24 months (Mann 2001), 30 months (Hawley 1995), and 36 months (Ellwood 1998; Feller 1996; Mann 1996; Vered 2009). Five of these six studies assessed caries, while the remaining study assessed periodontitis (Ellwood 1998). In all 30 studies, the final follow‐up assessment was at the end of the intervention phase.

One study had the additional intervention of flossing in both the triclosan/copolymer arm and the control arm (Schiff 2006), while four further studies included an element of oral hygiene instruction (Mann 2001; Pradeep 2012; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993).

Characteristics of the outcomes

Plaque

Twenty‐one studies included plaque as an outcome, with 20 of these reporting the Turesky et al modification of the Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index, which is a 0 to 5 scale. One of these studies also reported the Löe‐Silness Plaque Index (Renvert 1995), while another study only used the Löe‐Silness Plaque Index (Svatun 1993). Thirteen of the aforementioned 20 studies also reported the Plaque Severity Index, which is a measure of the proportion of higher scores (3 or higher) on the Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index.

Gingivitis

Twenty‐two studies included gingivitis as an outcome, with 20 of these reporting the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index (15 of which specified the Talbot et al modification), which is a 0 to 3 scale. Thirteen of these studies also reported the Gingivitis Severity Index, which is a measure of the proportion of higher scores (2 or 3, i.e. gingival bleeding) on the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index. Two further studies reported gingivitis using the Ainamo‐Bay Bleeding Index, but it was scored in such a way that we believed it equated to the Gingivitis Severity Index (Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993). One of the 20 studies also reported gingival bleeding (2 or 3 on the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index) but as the number of sites rather than a proportion (McClanahan 1997).

Periodontitis

One study included the outcome of periodontitis, which was reported as the dichotomous outcome of attachment loss or no attachment loss (Ellwood 1998).

Caries

Five studies included caries as an outcome. Four of these assessed coronal caries, all reporting the DFS caries increment, which is the change in decayed and filled surfaces (Feller 1996; Hawley 1995; Mann 1996; Mann 2001). Three of the same studies also reported the DFT caries increment, which is the change in decayed and filled teeth (Feller 1996; Hawley 1995; Mann 1996). One study assessed root caries, reporting the Katz Root Caries Index (Vered 2009).

Calculus

Three studies included calculus as an outcome, all stating that they used the Volpe‐Manhold Calculus Index, yet they were reported in different ways. Two of the studies reported the mean total calculus per participant (Liu 2002; Lobene 1991), while the other study reported the mean height of the calculus (Svatun 1993).

Adverse effects

Although 23 studies included adverse effects as an outcome, only one study reported one type of adverse effect (tooth staining using Meckel Stain Scores) in a way amenable to data analysis in this review (McClanahan 1997). However, this was not the fault of the study investigators in most cases, as they simply reported that there were no adverse events/effects, and, therefore, it is not possible to meta‐analyse such data. One study did report adverse events, but not by group or with sufficient details (Liu 2002). The staining in the McClanahan 1997 study was measured on a continuous scale and was not an adverse event as such. The studies investigated local adverse effects such as tooth staining, altered taste and included clinical examination of oral and perioral soft and hard tissues.

Excluded studies

We excluded 11 studies from the review (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). Below is a summary of the reasons for excluding these studies (some studies were excluded for more than one reason).

Four studies compared only active agents with no fluoride‐only control arm (Archila 2004; Boneta 2010; Dóri 1999; Mankodi 2002).

Three studies had co‐interventions confounding the results: powered toothbrushes used in the triclosan/copolymer arm (Bogren 2007; Bogren 2008); interdental cleaning in the control group (Kocher 2000).

Two studies included participants with periodontitis at baseline (Bogren 2008; Cullinan 2003).

Two studies had less than six months of the intervention (de la Rosa 1992; Dóri 1999).

One study involved supervised brushing (Archila 2004).

One study did not include a triclosan/copolymer arm (de la Rosa 1992).

One study had an inactive mouthwash as a co‐intervention and we judged that there was potential for this to wash away the active toothpaste ingredients (Charles 2001).

One study was an inappropriate design whereby participants with fewer than 20 gingival bleeding sites at baseline, accounting for 26% of the study sample, exited the study after three months (Winston 2002). This could undermine the randomisation process and introduce selection bias.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias based on the information reported in the included studies in the first instance. We attempted to contact study authors for missing information and clarification, and two sources provided additional information for 23 studies (Allen 2002; Bolden 1992; Cubells 1991; Deasy 1991; Denepitiya 1992; Ellwood 1998; Feller 1996; Garcia‐Godoy 1990; Hawley 1995; Hu 1997; Kanchanakamol 1995; Lindhe 1993; Lobene 1991; Mankodi 1992; Mankodi 2011; Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Mateu 2008; Palomo 1994; Schiff 2006; Triratana 1993; Triratana 2002; Vered 2009).

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We assessed 25 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain. Only two of these studies clearly reported the method of random sequence generation, allowing us to make this judgement (McClanahan 1997; Pradeep 2012). We assessed the other 23 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain after email correspondence with study authors, which confirmed that the studies had used appropriate methods. The remaining five studies did not report sufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Kraivaphan 2006; Liu 2002; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993; Triratana 1994).

Allocation concealment

We assessed 24 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain, only one of which reported information to allow this judgement (Pradeep 2012). The other 23 studies achieved this judgement after email correspondence. The remaining six studies did not report sufficient information to make a judgement and we assessed them as at unclear risk of bias (Kraivaphan 2006; Liu 2002; McClanahan 1997; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993; Triratana 1994).

Therefore, the overall risk of selection bias was low in 24 studies and unclear in six studies.

Blinding

Blinding of participants (performance bias)

Twenty‐nine studies made sufficient efforts to ensure that the triclosan/copolymer and the control toothpastes were indistinguishable from each other, and we assessed them as at low risk of bias for this domain. The remaining study assigned participants to either triclosan/copolymer toothpaste or normal oral hygiene procedure (Kanchanakamol 1995). Therefore, the participants were aware of their assignment thus introducing the potential for performance bias, so we assessed this study as at high risk of bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

We assessed all 30 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain, as they either clearly stated that the outcome assessor(s) was not aware of the participants' assignment or used the phrase 'double blind'.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed 18 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain, as 17 had 10% or less attrition, and one had 11% attrition but reported attrition by group, which was relatively equal (Hu 1997). We assessed two studies as at high risk of bias, one of which had 25% attrition, which could pose a risk of bias significant enough to have led to a distortion of the true intervention effect (Ellwood 1998), while the other did not report reasons for attrition, which was much higher in the triclosan/copolymer arm than the control arm (McClanahan 1997). We assessed the remaining 10 studies as at unclear risk of attrition bias because seven studies had attrition greater than 10% but with the additional factors of not being reported by group and not reporting reasons (Deasy 1991; Hawley 1995; Kanchanakamol 1995; Kraivaphan 2006; Lobene 1991; Svatun 1993; Vered 2009), while three studies did not report the number of participants initially randomised so it is not possible to calculate overall attrition, and they also did not report reasons for withdrawal/exclusion from the analyses (Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Mateu 2008).

Selective reporting

We assessed 23 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain, as they reported appropriate outcomes in full, as planned in the methods section of each study report. We assessed the remaining seven studies as at high risk of reporting bias. Two of these stated in the methods section that they would assess adverse effects, but did not report any information in the results section (Allen 2002; Pradeep 2012). Two studies assessed additional outcomes that are important to this review at follow‐up points but did not report them: plaque, gingivitis and calculus (Ellwood 1998), and coronal caries (Vered 2009). One of those studies also did not report the main outcome of the study (periodontitis) as stated in the methods section (Ellwood 1998). One study only reported variance of the mean scores visually as 95% confidence interval bars in the graphs, and our interpretation of the graphs gave different means to those reported in the study (Lindhe 1993). One study reported that there had been adverse effects but the data were not reported by group (Liu 2002). The remaining study did not report any information on the variance of the mean scores (Palomo 1994).

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed 23 studies as at low risk of bias for this domain, as no other potential sources of bias were apparent. Ten of these studies clearly reported information suggesting that outcome assessors were adequately trained or calibrated or both, implying that the risk of differential diagnostic activity would have been low (Allen 2002; Cubells 1991; Ellwood 1998; Feller 1996; Hawley 1995; Liu 2002; Mankodi 1992; Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Vered 2009). We judged 13 of the 23 studies to be at low risk of bias after email correspondence with study authors confirmed that the studies followed a protocol whereby all outcome assessors were highly trained in the indices and procedures used, and inter and intra‐examiner calibration occurred where practical (Bolden 1992; Deasy 1991; Denepitiya 1992; Garcia‐Godoy 1990; Hu 1997; Kanchanakamol 1995; Lindhe 1993; Lobene 1991; Mateu 2008; Palomo 1994; Schiff 2006; Triratana 1993; Triratana 2002). We assessed the remaining seven studies as at unclear risk of bias. Six of these studies did not report any methods to minimise differential diagnostic activity (Kraivaphan 2006; McClanahan 1997; Pradeep 2012; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993; Triratana 1994), and the remaining study reported statistically significant differences between groups at baseline for plaque scores and age, which could indicate a problem with the randomisation process (Mankodi 2011).

Overall risk of bias

We assessed 10 studies as being at low overall risk of bias (Bolden 1992; Cubells 1991; Denepitiya 1992; Feller 1996; Garcia‐Godoy 1990; Hu 1997; Mankodi 1992; Schiff 2006; Triratana 1993; Triratana 2002).

We assessed nine studies as being at high overall risk of bias (Allen 2002; Ellwood 1998; Kanchanakamol 1995; Lindhe 1993; Liu 2002; McClanahan 1997; Palomo 1994; Pradeep 2012; Vered 2009). These studies had at least one domain judged to be at high risk of bias.

We assessed 11 studies as being at unclear overall risk of bias (Deasy 1991; Hawley 1995; Kraivaphan 2006; Lobene 1991; Mankodi 2011; Mann 1996; Mann 2001; Mateu 2008; Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993; Triratana 1994). These studies had at least one domain judged to be at unclear risk of bias, but no domains judged to be at high risk of bias.

The results of the risk of bias assessments are presented graphically in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

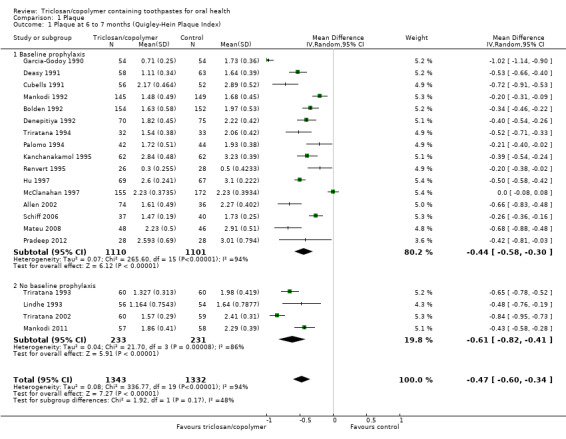

Plaque

Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index (six to seven months)

Twenty studies analysing 2675 participants (nine at low risk of bias, six at high risk of bias and five at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed a statistically significant reduction in plaque in favour of triclosan/copolymer (mean difference (MD) ‐0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.60 to ‐0.34, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 94%) (Analysis 1.1). The control group mean was 2.17, representing a 22% reduction in plaque. We performed subgroup analyses according to whether or not participants received a baseline prophylaxis and according to whether baseline plaque levels, prior to any baseline prophylaxes, were low or high (we used the median value (2.40) to dichotomise these), and the results are presented in Additional Table 2. All subgroup analyses still showed a statistically significant reduction in plaque in favour of triclosan/copolymer. However, for baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.44, 95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.30, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 94%), and no baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.61, 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.41, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 94%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 1.92, degrees of freedom (df) = 1, P value = 0.17, I2 = 47.8%). Also, for low baseline plaque (MD ‐0.41, 95% CI ‐0.57 to ‐0.25, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 92%), and high baseline plaque (MD ‐0.54, 95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.35, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 95%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 1.08, df = 1, P value = 0.30, I2 = 7%). As the subgroup analyses could not account for the considerable heterogeneity, it may be assumed that the causes are multiple. The results of this random‐effects meta‐analysis represent the average treatment effect across a range of settings. Therefore, we calculated a 95% prediction interval in order to provide information on the potential effectiveness of the intervention in an individual setting (Riley 2011). This ranged from ‐1.07 to 0.13 indicating that triclosan/copolymer will be beneficial in most settings but, as the interval overlaps zero, there is a small possibility that in some settings it may not be more effective than the control.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Plaque, Outcome 1 Plaque at 6 to 7 months (Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index).

1. Subgroup analyses.

| Subgroup factor | Mean difference (95% confidence interval) | Test for subgroup differences | |

| Baseline prophylaxis | Yes | No | |

| QHPI | ‐0.44 (‐0.58 to ‐0.30) | ‐0.61 (‐0.82 to ‐0.41) | Chi2 = 1.92, df = 1, P value = 0.17, I2 = 47.8% |

| PSI | ‐0.13 (‐0.18 to ‐0.08) | ‐0.20 (‐0.26 to ‐0.14) | Chi2 = 3.01, df = 1, P value = 0.08, I2 = 66.7% |

| LSGI | ‐0.26 (‐0.34 to ‐0.18) | ‐0.30 (‐0.39 to ‐0.21) | Chi2 = 0.43, df = 1, P value = 0.51, I2 = 0% |

| GSI | ‐0.12 (‐0.18 to ‐0.07) | ‐0.16 (‐0.27 to ‐0.05) | Chi2 = 0.32, df = 1, P value = 0.57, I2 = 0% |

| Baseline plaque levels |

Low (0.50 to 2.36) |

High (2.45 to 4.40) |

|

| QHPI | ‐0.41 (‐0.57 to ‐0.25) | ‐0.54 (‐0.72 to ‐0.35) | Chi2 = 1.08, df = 1, P value = 0.30, I2 = 7% |

| PSI | ‐0.15 (‐0.18 to ‐0.13) | ‐0.14 (‐0.21 to ‐0.07) | Chi2 = 0.14, df = 1, P value = 0.71, I2 = 0% |

| Baseline gingivitis levels |

Low (0.71 to 1.42) |

High (1.49 to 2.11) |

|

| LSGI | ‐0.21 (‐0.30 to ‐0.13) | ‐0.33 (‐0.36 to ‐0.31) | Chi2 = 7.41, df = 1, P value = 0.006, I2 = 86.5% |

| GSI* | ‐0.13 (‐0.19 to ‐0.07) | ‐0.17 (‐0.22 to ‐0.12) | Chi2 = 0.92, df = 1, P value = 0.34, I2 = 0% |

df: degrees of freedom; GSI: Gingivitis Severity Index (proportion of sites bleeding, i.e. 2 or 3 on the Löe‐Silness Gingival Index); LSGI: Löe‐Silness Gingival Index (0 to 3 on an increasing scale); PSI: Plaque Severity Index (proportion of surfaces scoring > 3 on the Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index); QHPI: Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index (0 to 5 on an increasing scale).

*2 studies not included due to no reporting of baseline LSGI scores (Renvert 1995; Svatun 1993).

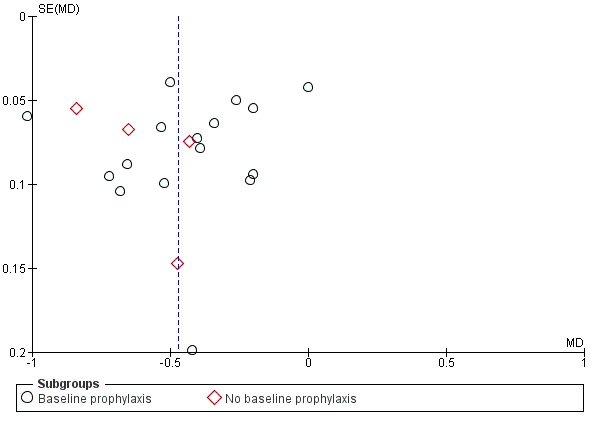

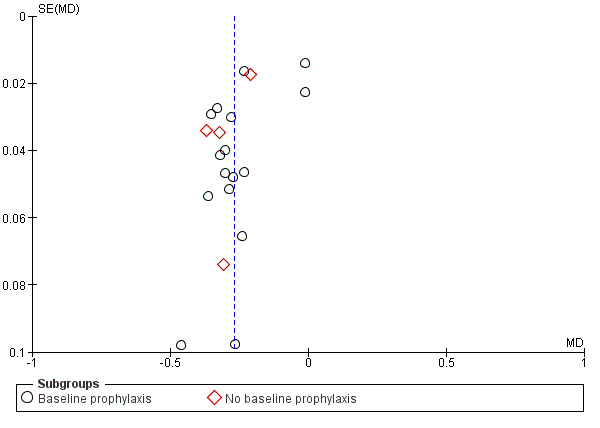

We were unable to detect the presence of any obvious publication bias in the funnel plot analysis (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Plaque, outcome: 1.1 Plaque at 6 to 7 months (Quigley‐Hein Plaque Index).

A sensitivity analysis, based on restricting the meta‐analysis to the nine studies assessed as being at low risk of bias, produced a similar result to the overall effect estimate in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.55, 95% CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.36, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 96%), indicating that the results are robust.

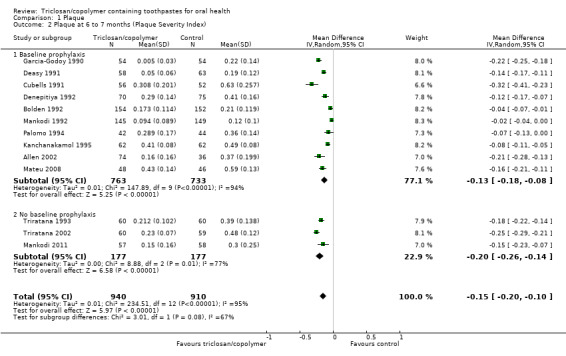

Plaque Severity Index (six to seven months)

Thirteen studies analysing 1850 participants (seven at low risk of bias, three at high risk of bias and three at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed a statistically significant reduction in plaque severity in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.10, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 95%) (Analysis 1.2). The control group mean was 0.37, representing a 41% reduction in plaque severity. Subgroup analyses based on baseline prophylaxis/no baseline prophylaxis and low/high baseline plaque scores were carried out and are presented in Additional Table 2. All subgroup analyses still showed a statistically significant reduction in plaque severity in favour of triclosan/copolymer. For baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.08, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 94%) and no baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.14, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 77%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 3.01, df = 1, P value = 0.08, I2 = 66.7%). Also, for low baseline plaque (MD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.13, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 34%) and high baseline plaque (MD ‐0.14, 95% CI ‐0.21 to ‐0.07, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 97%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 0.14, df = 1, P value = 0.71, I2 = 0%). As the subgroup analyses could not account for the considerable heterogeneity, it may be assumed that the causes are multiple. The 95% prediction interval for the average effect ranged from ‐0.34 to 0.05 indicating a beneficial effect in most settings.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Plaque, Outcome 2 Plaque at 6 to 7 months (Plaque Severity Index).

A sensitivity analysis, based on restricting the meta‐analysis to the seven studies assessed as being at low risk of bias, produced a similar result to the overall effect estimate in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.24 to ‐0.08, P value < 0.0001, I2 = 97%), indicating that the results are robust.

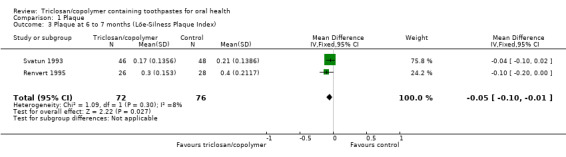

Löe‐Silness Plaque Index (six to seven months)

Two studies analysing 148 participants (both at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis which showed a marginally statistically significant reduction in plaque in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.10 to ‐0.01, P value = 0.03, I2 = 8%) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Plaque, Outcome 3 Plaque at 6 to 7 months (Löe‐Silness Plaque Index).

Gingivitis

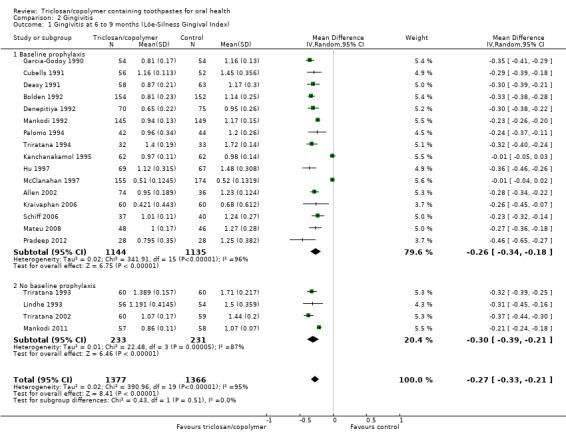

Löe‐Silness Gingival Index (six to nine months)

Twenty studies analysing 2743 participants (nine at low risk of bias, six at high risk of bias and five at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed a statistically significant reduction in gingivitis in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.33 to ‐0.21, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 95%) (Analysis 2.1). The control group mean was 1.22, representing a 22% reduction in inflammation. We performed subgroup analyses according to whether or not participants received a baseline prophylaxis and according to whether baseline gingivitis (inflammation) levels, prior to any baseline prophylaxes, were low or high (we used the median value (1.455) to dichotomise these), and the results are presented in Additional Table 2. All subgroup analyses still showed a statistically significant reduction in gingivitis in favour of triclosan/copolymer. However, for baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.26, 95% CI ‐0.34 to ‐0.18, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 96%) and no baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.21, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 87%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 0.43, df = 1, P value = 0.51, I2 = 0%). In contrast, for low baseline gingivitis (MD ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.30 to ‐0.13, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 97%) and high baseline gingivitis (MD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.36 to ‐0.31, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 0%), there was a statistically significant difference between subgroups in favour of a larger effect for the high baseline values (Chi2 = 7.41, df = 1, P value = 0.006, I2 = 86.5%). The low baseline gingivitis subgroup still showed considerable heterogeneity while the high baseline subgroup showed no heterogeneity, but the causes of this are unclear and likely to be multiple. The 95% prediction interval for the average effect ranged from ‐0.56 to 0.02 indicating a beneficial effect in most settings.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gingivitis, Outcome 1 Gingivitis at 6 to 9 months (Löe‐Silness Gingival Index).

We were unable to detect the presence of any obvious publication bias in the funnel plot analysis (Figure 5).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Gingivitis, outcome: 2.1 Gingivitis at 6 to 9 months (Löe‐Silness Gingival Index).

A sensitivity analysis, based on restricting the meta‐analysis to the nine studies assessed as being at low risk of bias, produced a similar result to the overall effect estimate in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.35 to ‐0.27, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 73%), indicating that the results are robust.

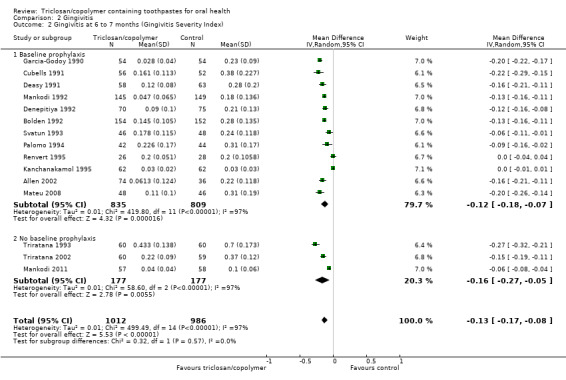

Gingivitis Severity Index (six to seven months)

Fifteen studies analysing 1998 participants (seven at low risk of bias, three at high risk of bias and five at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed a statistically significant reduction in gingivitis severity (gingival bleeding) in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.08, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 97%) (Analysis 2.2). The control group mean was 0.27, representing a 48% reduction in bleeding. Subgroup analyses based on baseline prophylaxis/no baseline prophylaxis and low/high baseline gingivitis scores were carried out and are presented in Additional Table 2. All subgroup analyses still showed a statistically significant reduction in gingivitis severity in favour of triclosan/copolymer. For baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.07, P value < 0.0001, I2 = 97%) and no baseline prophylaxis (MD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.27 to ‐0.05, P value = 0.006, I2 = 97%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 0.32, df = 1, P value = 0.57, I2 = 0%). Also, for low baseline gingivitis (MD ‐0.13, 95% CI ‐0.19 to ‐0.07, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 97%) and high baseline gingivitis (MD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.22 to ‐0.12, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 86%), there was no statistically significant difference between subgroups (Chi2 = 0.92, df = 1, P value = 0.34, I2 = 0%). As the subgroup analyses could not account for the considerable heterogeneity, it may be assumed that the causes are multiple. The 95% prediction interval for the average effect ranged from ‐0.32 to 0.07 indicating a beneficial effect in most settings.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gingivitis, Outcome 2 Gingivitis at 6 to 7 months (Gingivitis Severity Index).

A sensitivity analysis, based on restricting the meta‐analysis to the seven studies assessed as being at low risk of bias, produced a similar result to the overall effect estimate in favour of triclosan/copolymer (MD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.14, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 84%), indicating that the results are robust.

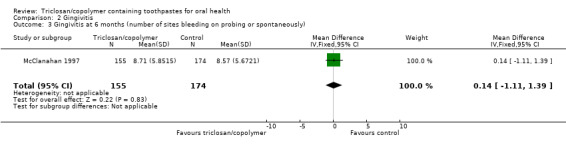

Number of bleeding sites (six months)

One study at high risk of bias, analysing 329 participants, showed no evidence of a difference between triclosan/copolymer and control (MD 0.14, 95% CI ‐1.11 to 1.39) (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Gingivitis, Outcome 3 Gingivitis at 6 months (number of sites bleeding on probing or spontaneously).

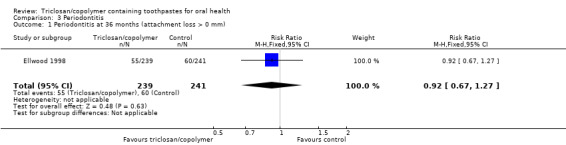

Periodontitis

Attachment loss (36 months)

One study at high risk of bias, analysing 480 participants, showed no evidence of a difference between triclosan/copolymer and control (risk ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.27) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Periodontitis, Outcome 1 Periodontitis at 36 months (attachment loss > 0 mm).

Caries

Coronal caries

Change in decayed and filled teeth (30 to 36 months)

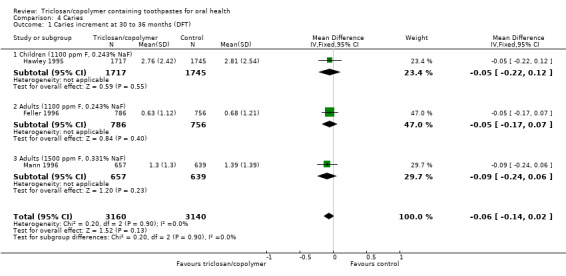

Three studies analysing 6300 participants (one at low risk of bias and two at unclear risk of bias) were combined in a meta‐analysis, which showed no evidence of a difference between triclosan/copolymer and control (MD ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.02, P value = 0.13, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 4.1). There were three subgroups, each consisting of one study, and all of which showed no evidence of a difference. The subgroups were: 1) children (permanent dentition) and 0.243% sodium fluoride/1100 parts per million (ppm) fluoride; 2) adults and 0.243% sodium fluoride/1100 ppm fluoride; and 3) adults and 0.331% sodium fluoride/1500 ppm fluoride. There were no statistically significant differences between the subgroups (Chi2 = 0.20, df = 2, P value = 0.90, I2 = 0%) indicating that it was probably appropriate to pool them in a combined meta‐analysis.

4.1. Analysis.