Abstract

Pathogenic bacteria engage in social interactions to colonize hosts, which include quorum-sensing-mediated communication and the secretion of virulence factors that can be shared as “public goods” between individuals. While in-vitro studies demonstrated that cooperative individuals can be displaced by “cheating” mutants freeriding on social acts, we know less about social interactions in infections. Here, we developed a live imaging system to track virulence factor expression and social strain interactions in the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonizing the gut of Caenorhabditis elegans. We found that shareable siderophores and quorum-sensing systems are expressed during infections, affect host gut colonization, and benefit non-producers. However, non-producers were unable to successfully cheat and outcompete producers. Our results indicate that the limited success of cheats is due to a combination of the down-regulation of virulence factors over the course of the infection, the fact that each virulence factor examined contributed to but was not essential for host colonization, and the potential for negative frequency-dependent selection. Our findings shed new light on bacterial social interactions in infections and reveal potential limits of therapeutic approaches that aim to capitalize on social dynamics between strains for infection control.

Subject terms: Bacteria, Microbial ecology

Introduction

During infections, pathogenic bacteria secrete a wide range of extracellular virulence factors to colonize and grow inside the host [1, 2]. Secreted molecules include siderophores for iron scavenging, signaling molecules for quorum sensing (QS), toxins to attack host cells, and matrix compounds for biofilm formation [3–6]. In-vitro studies have shown that extracellular virulence factors can be shared as “public goods” between cells, and thereby benefit individuals other than the producing cell [7–9]. There has been enormous interest in understanding how this form of bacterial cooperation can be evolutionarily stable since secreted public goods can be exploited by non-cooperative mutants called “cheats”, which do not engage in cooperation yet still benefit from the molecules produced by others [10–12].

There is increasing evidence that social interactions and cooperator–cheat dynamics might also matter within hosts [9, 13, 14]. For instance, in controlled infection experiments engineered non-producers, deficient for the production of specific virulence factors, could outcompete producers and thereby reduce virulence [15–19], but in other cases the success of non-producers was compromised [20, 21]. Other studies have followed chronic human infections within patients over time and reported that virulence-factor-negative mutants emerge and spread, with the mutational patterns suggesting cooperator–cheat dynamics [7, 22, 23]. These findings spurred ideas of how social interactions within hosts could be manipulated for therapeutic purposes [14, 24, 25]. Suggested approaches include: inducing cooperator–cheat dynamics to steer infections towards lower virulence [7, 26]; introducing less virulent strains with medically beneficial alleles into established infections [24]; and targeting secreted virulence factors to control infections and constrain the evolution of resistance [25, 27–31].

However, all these approaches explicitly rely on the assumption that the social traits of interest are: (i) expressed inside hosts; (ii) important for host colonization; (iii) exploitable; and (iv) induce cooperator–cheat dynamics as observed in vitro [9]—assumptions that have not yet been tested in real time inside living hosts. Here, we explicitly test the importance of bacterial social interactions within hosts by using in vivo fluorescence microscopy to monitor bacterial virulence factor production, host colonization and strain interactions, using the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its nematode model host Caenorhabditis elegans [32–34].

C. elegans naturally grazes on bacteria [35]. While most bacteria are killed during ingestion, a small fraction of cells survives [36], which can, in the case of pathogenic bacteria, establish an infection in the gut [37]. P. aeruginosa deploys an arsenal of virulence factors that facilitate successful host colonization [38]. For example, the two siderophores pyoverdine and pyochelin scavenge host-bound iron during acute infections to enable pathogen growth [6, 39–41]. P. aeruginosa further secretes the protease elastase, the toxin pyocyanin, and rhamnolipid biosurfactants to attack host tissue [7, 42, 43]. Production of these latter virulence factors only occurs at high cell densities and is controlled by the Las and the Rhl QS-systems [44]. Because both QS-regulated virulence factors and siderophores were shown to be involved in C. elegans killing [37, 45–48], we used them as focal traits for our study.

To tackle our questions, we first conducted experiments with fluorescently tagged P. aeruginosa bacteria (PAO1) to follow infection dynamics, from the first uptake through feeding up to a progressed state of gut infection. We then constructed promoter–reporter fusions for genes involved in the synthesis of the two siderophores (pyoverdine and pyochelin) and the two QS-regulators (LasR and RhlR) to track in-vivo virulence factor gene expression during host colonization. Subsequently, we used mutant strains deficient for virulence factors to determine whether they show compromised colonization abilities. Finally, we followed mixed infections of wildtype and mutants over time to determine the extent of strain co-localization in the gut, and to test whether secreted virulence factors are indeed exploitable by non-producers in the host.

Material and methods

Strain and bacterial growth conditions

Bacterial strains, primers and plasmids used in this study are listed in the Supplementary Tables S1–S3. Details on strain construction are outlined in the Supplementary Methods. For all experiments, overnight cultures were grown in 8 ml Lysogeny broth (LB) in 50 ml tubes, incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm for 18 h, washed with 0.8% NaCl solution and adjusted to OD600 = 1.0. Nematode growth media (NGM) plates [0.25% peptone, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM [PO4−], 5 μg/ml cholesterol, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4 supplemented with 1.5% agar, 6 cm diameter] were seeded with 50 μl of bacterial culture and incubated at 25 °C for 24 h. All P. aeruginosa strains used in this study showed equal growth on NGM exposure plates (Supplementary Figure S1). Peptone was purchased from BD Biosciences, Switzerland, all other chemicals from Sigma Aldrich, Switzerland.

Nematode culture

We used the temperature-sensitive, reproductively sterile C. elegans strain JK509 (glp-1(q231) III). This strain reproduces at 16 °C, but does not develop gonads and is therefore sterile at 25 °C. Worms were maintained fertile at 16 °C on high growth media (HGM) agar plates (2% Peptone, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM [PO4−], 20 μg/ml cholesterol, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4) seeded with the standard food source Escherichia coli strain OP50 [49]. For age synchronization, plates were washed with sterile distilled water and adult worms were killed with hypochlorite–sodium hydroxide solution to isolate eggs [49]. Eggs were placed in M9 buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, 40 mM Na2HPO4, 80 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgSO4) and incubated at 16 °C for 16–18 h to hatch. Then, L1 larvae were transferred to OP50-seeded HGM plates and incubated at 25 °C for 28 h to reach L4 developmental stage. Worms and OP50 bacteria were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center (CGC), which is supported by the National Institutes of Health - Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

C. elegans infection protocol

Synchronized L4 worms were washed from HGM plates with M9 buffer + 50 μg/ml kanamycin (M9-Kan), and washed three times with M9-Kan for worm surface disinfection. Viable worms were further separated from any debris by sucrose flotation [50] and rinsed three times in M9 buffer to remove sucrose. The worm handling protocol for the main experiments is depicted in Fig. 1a. Specifically, ~200 worms were moved to seeded NGM plates and incubated for 24 h at 25 °C. After this period of exposure to pathogens, infected worms were extensively washed with M9 buffer + 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol (M9-Cm) followed by M9 buffer, subsequently transferred to individual wells of a six-well plate filled with sterile M9 buffer + 5 μg/ml cholesterol (M9 + Ch Buffer), where they were kept up to 48 h post exposure (hpe) and imaged after 0, 6, and 30 hpe.

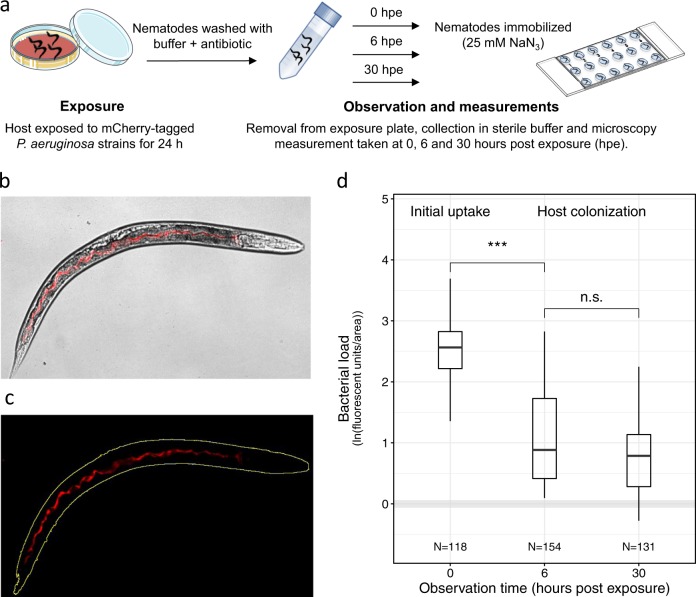

Fig. 1.

Quantifying P. aeruginosa infections in the C. elegans gut. a Experimental procedure: we used fluorescently tagged P. aeruginosa strains to examine bacterial colonization of the C. elegans gut. Per experiment, we exposed ~200 C. elegans nematodes to a lawn of mCherry-tagged PAO1 strains for 24 h. Subsequently, nematodes were removed from the bacterial plate, surface washed and collected in sterile buffer for monitoring. After 0, 6, or 30 h post exposure (hpe), ~30 nematodes were immobilized and transferred to microscopy slides for imaging. b Brightfield and fluorescence channel merged image depicting mCherry-fluorescent bacteria inside the host gut. c Bacterial load inside the nematode was quantified as the sum of fluorescence intensity across pixels in the region of interest (ROI; yellow outline) and standardized by total worm area. d Colonization dynamics of the wildtype strain PAO1-mCherry: immediately after removal from the exposure plate (0 hpe), worms showed high bacterial loads inside their guts. Bacterial load first declined when the worms where kept in buffer for 6 h, but then remained constant for the next 24 h. Gray shaded area indicates background fluorescence (mean ± standard deviation) of worms exposed to the non-fluorescent, non-pathogenic E. coli OP50. N = number of worms from four independent experiments. ***p < 0.001, n.s. not statistically significant

Nematode survival assay

Our goal was to observe infections inside living hosts. To verify that worms stayed alive during the experiment (up to 48 hpe), we tracked the survival of infected populations (50–90 worms) in M9-Ch buffer. Worms were tested for motility at 0, 24, and 48 hpe, by prodding them with a platinum wire. Worms were considered dead when they no longer responded to touches. Each bacterial strain was tested in three replicates and three independent experiments were carried out. We used E. coli OP50 as a negative control for killing. During this observation period, worms experienced only negligible killing by the colonizing bacteria, and we found no significant difference in killing between the non-pathogenic E. coli food strain and the P. aeruginosa strains (Supplementary Figure S2).

Microscopy setup and imaging

For microscopy, we picked individual worms from the M9 + Ch buffer and paralyzed them with 25 mM sodium azide before transferring them to an 18-well μ-slide (Ibidi, Germany). All experiments were carried out at the Center for Microscope and Image Analysis of the University Zurich (ZMB). For the colonization experiment, images were acquired on a Leica LX inverted widefield light microscope system with Leica-TX2 filter cube for mCherry (emission: 560 ± 40 nm, excitation: 645 ± 75 nm, DM = 595) and Leica-DFC-350-FX, cooled fluorescence monochrome camera (resolution: 1392 × 1040 pixels) for image recording (16-bit color depth). For gene expression experiments, microscopy was performed on the InCell Analyzer 2500HS (GE Healthcare) automated imaging system, using a polychroic beam splitter BGRFR_2 (for mCherry, excitation: 575 ± 25 nm, emission: 607.5 ± 19 nm; for GFP, excitation: 475 ± 28 nm, emission: 526 ± 52 nm) and PCO–sCMOS camera (resolution: 2048 × 2048 pixels, 16-bit).

Image processing and analysis

To extract fluorescence measurements from individual worms, images were segmented into objects and background, using an automated image segmentation workflow with the ilastik software [51]. Segmented images were then imported in Fiji [52] to determine the fluorescence intensity (as “Raw Integrated Density”, i.e. the sum of pixels values in the selection) and area of each worm. Images obtained from the InCell microscope entailed 64 frames (8 × 8 grid) with 10% overlap. These frames were stitched together using a macro-automated version of the Stitching plugin in Fiji [53] prior to segmentation and analysis. To correct for background and host-tissue autofluorescence, we imaged, at each time point, worms infected with non-fluorescent strains (i.e. OP50 or PAO1), and used the mean intensity of these control infections to subtract background fluorescence values from worms infected with fluorescent strains.

Competition assay in the host

For in-vivo competitions between PAO1-mCherry and PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF or PAO1ΔlasR, overnight monocultures were washed twice with 0.8% NaCl solution, adjusted to OD600 = 1.0 and mixed at a 1:1 ratio. To control for fitness effects of the mCherry marker, we also competed PAO1-mCherry against the untagged PAO1. NGM plates were then seeded with 50 μl of mixed culture and incubated at 25 °C for 24 h. Worms were exposed to the mix for 24 h and then recovered as previously described. At 6 and 48 h post-exposure, individual worms were picked, immobilized with sodium azide and washed for 5 min with M9 + 0.003% NaOCl. Worms were washed twice with M9 buffer. We then transferred each individual worm to a 1.5 ml screw-cap microtube (Sarstedt, Switzerland) containing sterilized glass beads (1 mm diameter, Sigma Aldrich). Worms were disrupted using a bead-beater (TissueLyser II, QIAGEN, Germany), shaking at 30 Hz for 1.5 min before flipping the tubes and shaking for an additional 1.5 min to ensure even disruption (adapted from ref. [54]). Tubes were then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 2 min, the content was re-suspended in 200 μl of 0.8% NaCl and plated on two LB 1.2% agar plates for each sample. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and left at room temperature for another 24 h to allow the fluorescent marker to fully mature. We then distinguished between fluorescent and non-fluorescent colonies using a custom built fluorescence imaging device (Infinity 3 camera, Lumenera, Canada). We then calculated the relative fitness of PAO1-mCherry as ln(v) = ln{[a48 × (1−a6)]/[a6 × (1−a48)]}, where a6 and a48 are the frequency of PAO1-mCherry at 6 and 48 h after recovery, respectively [55]. Values of ln(v) < 0 or ln(v) > 0 indicate whether the frequency of PAO1-mCherry increased or decreased relative to its competitor.

Co-localization analysis

To determine the degree of co-localization of two different bacterial strains in the host, we transferred nematodes to NGM plates seeded with a 1:1 mix of PAO1-gfp with either PAO1-mCherry, PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF–mCherry, or PAO1ΔlasR-mCherry. After a 24 h grazing period, we picked single worms and imaged both mCherry- and GFP channels, using the InCell Analyzer 2500HS microscope. We used Fiji to straighten each worm with the Straighten plugin [56], and extracted fluorescence intensity values in the GFP and mCherry channels for each pixel from tail (X = 0) to head (X = 1) of the worm. To ensure that we only measure areas where bacteria were present, we restricted our analysis to the region of the worm gut where bacterial colonization took place. We then calculated Spearman correlation coefficients between the fluorescent signals, as a proxy for strain co-localization using RStudio v. 3.3.0 [57].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with RStudio. We used Pearson correlations to test for associations between PAO1-mCherry fluorescence intensities and (a) recovered bacteria from the gut and (b) total bacterial load in mixed infections. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare fluorescence values between observation times, strains and for comparisons to non-fluorescent controls. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the post-hoc Tukey HSD test. To compare promoter expression data between wildtype PAO1 and mutant strains, and to compare relative fitness values between competitors in the competition assay, we used Welch’s two-sample t-test. To measure co-localization, we calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient ρ between the intensity of mCherry and GFP signals across the worm gut, and used ANOVA to test for differences between treatments.

Results

PAO1 colonization dynamics in the C. elegans gut

For all infection experiments, we followed the protocol depicted in Fig. 1a–c. We first exposed worms to P. aeruginosa for 24 h on NGM plates. Subsequently, worms were removed, washed, and treated with antibiotics to kill external bacteria. We then imaged infected worms under the microscope at different time points and quantified bacterial density and gene expression using fluorescent mCherry markers. We first confirmed that mCherry fluorescence is a suitable proxy for the number of live bacteria in C. elegans, by comparing fluorescence intensities in whole worms (Fig. 1b) to the number of live bacteria recovered from the worms’ gut. Fluorescence intensity values positively correlated with the bacterial load inside the nematodes, both immediately after recovering the worms from the exposure plates and at 6 h post exposure (hpe; Supplementary Figure S3, Pearson correlation coefficient at 0 hpe: r = 0.49, t28 = 3.02, p = 0.005; at 6 hpe: r = 0.713, t23 = 4.88, p < 0.001). As our goal was to image infections in living hosts, we further confirmed that worms stayed alive during the observation period (Supplementary Figure S2).

When following host colonization by PAO1-mCherry over time, we observed that immediately after removal from the exposure plate, worms carried large amounts of bacteria in their gut (Fig. 1d). Subsequently, bacterial load significantly declined when worms were kept in buffer for 6 h (ANOVA: t391 = −8.55, p < 0.001) and then remained constant for the next 24 h (t391 = 0.61, p = 0.529). This pattern suggests that a large number of bacteria are taken up during the feeding phase, followed by the shedding of a high proportion of cells, leaving behind a fraction of live bacteria that establishes an infection and colonizes the worm gut.

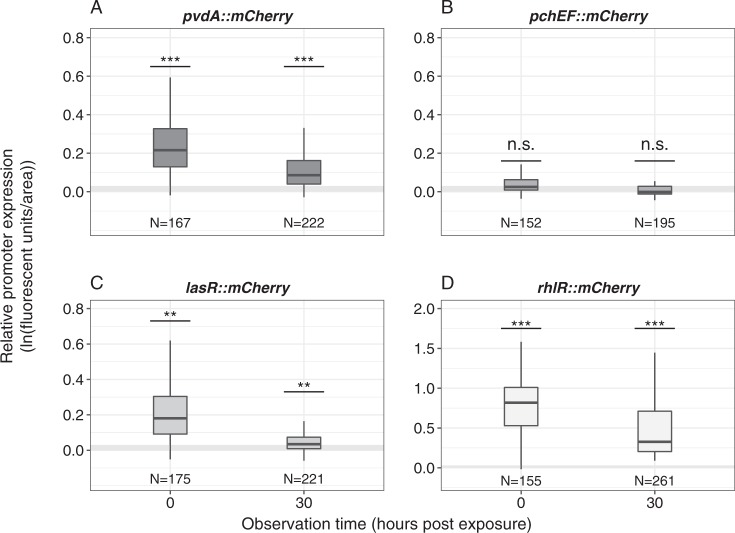

PAO1 expresses siderophore biosynthesis genes and QS regulators in the host

We then examined whether genes involved in the synthesis of pyoverdine (pvdA) and pyochelin (pchEF), and the genes encoding the QS-regulators lasR and rhlR, are expressed inside hosts. Worms were exposed to four different PAO1 strains, each carrying a specific promoter–mCherry fusion. Imaging after the initial uptake phase (0 hpe) revealed that, with the exception of pchEF, all genes were significantly expressed in the host (Fig. 2; ANOVA, comparisons to the non-fluorescent control, for pvdA: t754 = 4.23, p < 0.001; for pchEF: t754 = 0.74, p = 0.461; for lasR: t754 = 2.96, p = 0.003; for rhlR: t754 = 10.37, p < 0.001). Although fluorescence intensity declined over time (linear model, F1,1795 = 48.98, p < 0.001), we observed that apart from pchEF, all genes were still significantly expressed during the subsequent colonization of the host at 30 hpe (Fig. 2; ANOVA, for pvdA: t754 = 4.87, p < 0.001; for pchEF: t754 = 0.684, p = 0.461; for lasR: t754 = 3.01, p = 0.003; for rhlR: t754 = 16.68, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

P. aeruginosa expresses genes for pyoverdine synthesis and quorum-sensing regulators in the host gut. To quantify the expression of virulence factor genes inside hosts, worms were exposed to four PAO1 strains, each containing a promoter::mCherry fusion for either pvdA (pyoverdine synthesis), pchEF (pyochelin synthesis), lasR or rhlR (quorum-sensing regulators). With the exception of pchEF, all genes were significantly expressed in the host, both at 0 and 30 hpe. Expression levels were standardized for bacterial load. Gray shaded areas depict background fluorescence (mean ± standard deviation) of worms exposed to the non-fluorescent, non-pathogenic E. coli OP50. N = number of worms from four independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s. not statistically significant

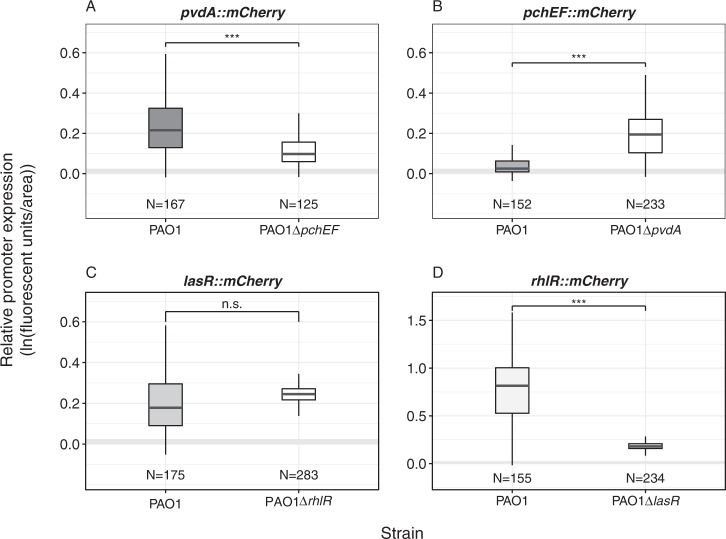

Regulatory links between social traits operate inside the host

We know that regulatory links exist between the virulence traits studied here. While pyoverdine synthesis suppresses pyochelin production under stringent iron limitation [58], the Las-QS system positively activates the Rhl-QS system [44]. To test whether these links operate inside the host, we measured gene expression of each trait in the negative background of the co-regulated trait (Fig. 3, 0 hpe; Supplementary Figure S5, 30 hpe). For pvdA, we observed significant gene expression levels in both the wildtype PAO1 and the pyochelin-deficient PAO1ΔpchEF strain (Fig. 3a), albeit the overall expression was slightly reduced in PAO1ΔpchEF (t-test, t253 = 8.67, p < 0.001). For pchEF, expression patterns confirm the suppressive nature of pyoverdine: the pyochelin synthesis gene was not expressed in the wildtype but significantly upregulated in the pyoverdine-deficient PAO1ΔpvdD strain (Fig. 3b; t296 = −19.68, p < 0.001). For lasR, we found that gene expression was not significantly different in wildtype PAO1 compared to the Rhl-negative mutant PAO1ΔrhlR, confirming that the Las-QS system is at the top of the hierarchy and not influenced by the Rhl-system (Fig. 3c; t211 = −1.50, p = 0.136). Conversely, the expression of rhlR was strongly dependent on a functional Las-system, and therefore only expressed in PAO1, but repressed in the Las-negative mutant PAO1ΔlasR (Fig. 3d; t156 = 19.04, p < 0.001). These results show that (i) iron-limitation is strong in C. elegans as PAO1 primarily invests in the more potent siderophore pyoverdine; (ii) pyochelin can have compensatory effects when pyoverdine is lacking; and (iii) the loss of the Las-system leads to the concomitant collapse of the Rhl-system.

Fig. 3.

P. aeruginosa can switch between siderophores, while quorum-sensing regulators act hierarchically. Because virulence traits are linked at the regulatory level, we measured gene expression of each trait in the negative background of the co-regulated trait. a The expression of the pyoverdine synthetic gene pvdA is significantly expressed in the wildtype and the pyochelin-negative background, but slightly reduced in the latter. b The pyochelin synthetic gene pchEF is significantly expressed in the pyoverdine-negative background, but silent in the wildtype. c The expression of the QS-regulator gene lasR is unchanged in the Rhl-negative background compared to the wildtype. d The expression of the QS-regulator gene rhlR is reduced in the Las-negative background. Expression levels were measured at 0 hpe and standardized for bacterial load. Promoter expression levels at 30 hpe are shown in Supplementary Figure S5. Gray shaded areas depict background fluorescence (mean ± standard deviation) of worms exposed to the non-fluorescent, non-pathogenic E. coli OP50. N = number of worms form four independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n.s. not statistically significant

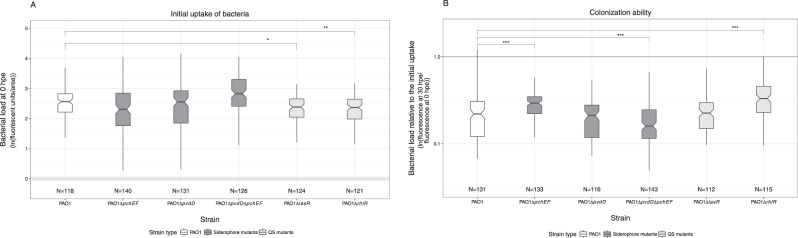

Virulence-factor-negative mutants show trait-specific deficiencies in host colonization

To examine whether the ability to produce shared virulence factors is important for initial bacterial uptake and host colonization, we exposed C. elegans to five isogenic mutants of PAO1-mCherry, either impaired in the production of pyoverdine (ΔpvdD), pyochelin (ΔpchEF), both siderophores (ΔpvdDΔpchEF), the QS receptor LasR (ΔlasR), or the QS receptor RhlR (ΔrhlR). After the feeding phase, the bacterial load of the wildtype and all three siderophore mutants was equal inside hosts, whereas bacterial load was significantly reduced for the two QS-mutants compared to the wildtype (Fig. 4a; ANOVA, significant variation among strains F5,736 = 10.50, p < 0.001; post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons: p > 0.05 for all siderophore mutants, p = 0.021 for PAO1ΔlasR, p < 0.001 for PAO1ΔrhlR).

Fig. 4.

Virulence factor production affects bacterial uptake and host colonization ability. a Bacterial load inside C. elegans guts measured immediately after the recovery of worms from the exposure plates (0 h post exposure; hpe). Comparisons across isogenic PAO1 mutant strains, each deficient for the production of one or two virulence factors, reveal that the two quorum-sensing mutants PAO1ΔlasR and PAO1ΔrhlR reached lower bacterial densities than the wildtype. b Comparison of the relative colonization success of strains (ratio of bacterial loads at 0 hpe vs. 30 hpe) revealed that the siderophore-negative strain PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF showed significantly reduced ability to remain in the host compared to the wildtype. In contrast, the colonization success of PAO1ΔpchEF and PAO1ΔrhlR was increased relative to the wildtype. Gray shaded areas depict background fluorescence (mean ± standard deviation) of worms exposed to the non-fluorescent, non-pathogenic E. coli OP50. N = number of worms form four independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

As shown above for PAO1 colonization (Fig. 1d), we observed that the bacterial load of all strains declined at 6 hpe (Supplementary Figure S4) and 30 hpe (Fig. 4b) following worm removal from the exposure plates. This decline was significantly more pronounced for the double-siderophore knockout PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF than for the wildtype (Fig. 4b; ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test p < 0.001). In contrast, mutants deficient in pyochelin (PAO1ΔpchEF) and RhlR (PAO1ΔrhlR) production showed a significantly higher ability to remain in the host than the wildtype (Fig. 4b; ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test p < 0.001 for both strains). Taken together, our findings suggest that the two siderophores can complement each other, and that only the siderophore double mutant and the LasR-deficient strain have an overall disadvantage in colonizing worms.

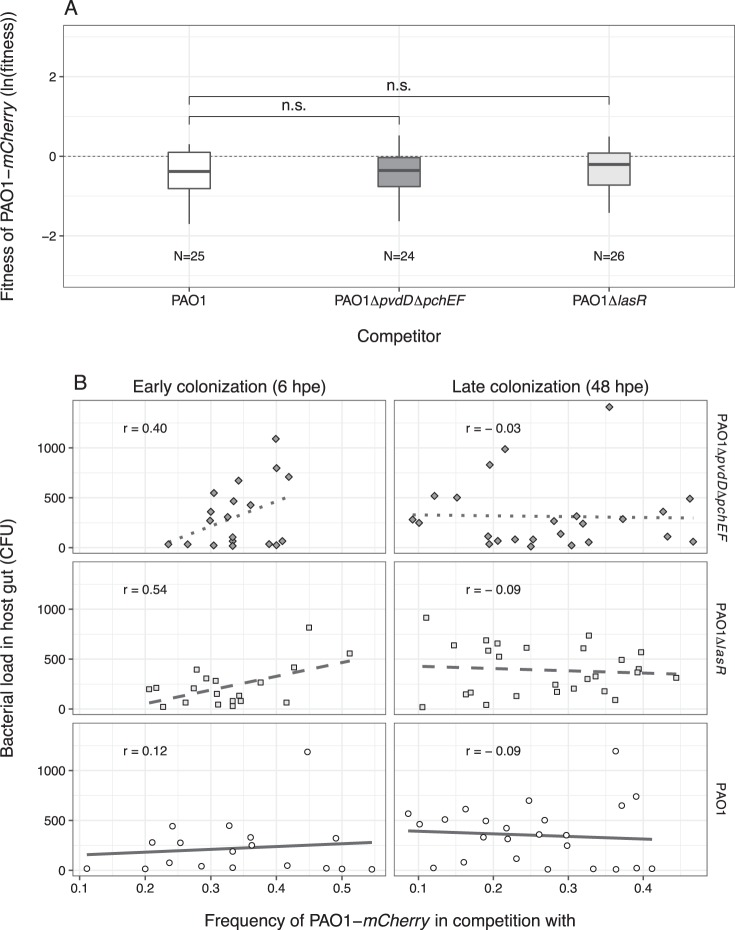

Mixed communities are formed inside hosts, but exploitation of social traits is constrained

Given our findings on colonization deficiencies, we reasoned that the siderophore-double mutant (PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF) and the Las-deficient mutant (PAO1ΔlasR) could act as cheats and benefit from the exploitation of virulence factors produced by the wildtype in mixed infections. To test this hypothesis, we first competed the PAO1-mcherry strain against the untagged wildtype in the host, and found that the mCherry tag had a small negative effect on PAO1 fitness (Fig. 5a; one sample t-test, t24 = −4.12, p < 0.001). We then competed PAO1-mCherry against the two putative cheats and found that neither of them could gain a significant fitness advantage over the wildtype, but also did not lose out (Fig. 5a; ANOVA, F2,70 = 0.517, p = 0.598). These results indicate that virulence-factor-negative mutants, initially compromised in host colonization, can indeed benefit from the presence of the wildtype producer, but not to an extent that would allow them to increase in frequency and displace producers.

Fig. 5.

Mixed infections reveal social strain dynamics but no successful cheating. a Relative fitness of the wildtype PAO1-mCherry after 42 h of competition inside the C. elegans gut against an untagged PAO1 control strain; the siderophore-negative strain PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF; and the Las-negative strain PAO1ΔlasR. The control competition revealed a mild but significant negative effect of the mCherry tag on wildtype fitness. When accounting for these mCherry costs, we found that the putative cheat strains PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF and PAO1ΔlasR performed equally well compared to the wildtype, but could not outcompete it. This suggests that virulence factor deficient strains benefit from the presence of non-producers but cannot successfully cheat on them. b At 6 hpe, wildtype frequency in mixed infections correlated positively with total bacterial load inside hosts in competition with PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF (diamonds and dotted lines) and PAO1ΔlasR (squares and dashed lines) but not in the control competition (circles and solid lines). These correlations disappeared at 48 hpe. Each data point represents an individual worm. Data shown in a+b stem from the same three independent experiments

Since our mono-infection experiments showed that the wildtype can maintain higher bacterial loads in the worms compared to the two mutants (Fig. 4b), we hypothesized that worms, which have initially taken up higher frequencies of the wildtype relative to the mutant should carry increased bacterial loads in the gut. We found this prediction to hold true at 6 hpe in mixed infections with the two non-producers, but not in the control mixed infections with the untagged wildtype (Fig. 5b, 6 hpe; Pearson correlation coefficient, for mixed infection with PAO1ΔlasR: r = 0.54, t17 = 2.67, p = 0.016; with PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF: r = 0.40, t17 = 1.77, p = 0.031; with control PAO1: r = 0.12, t17 = 0.47, p = 0.639). These correlations disappeared at the later colonization stage (Fig. 5b, 48 hpe; Pearson correlation coefficient r < 0, p > 0.05 for all strains). The loss of these correlations indicates that rare producers experienced a selective advantage during competition and increased in relative frequency, while common producers might have lost and decreased in frequency.

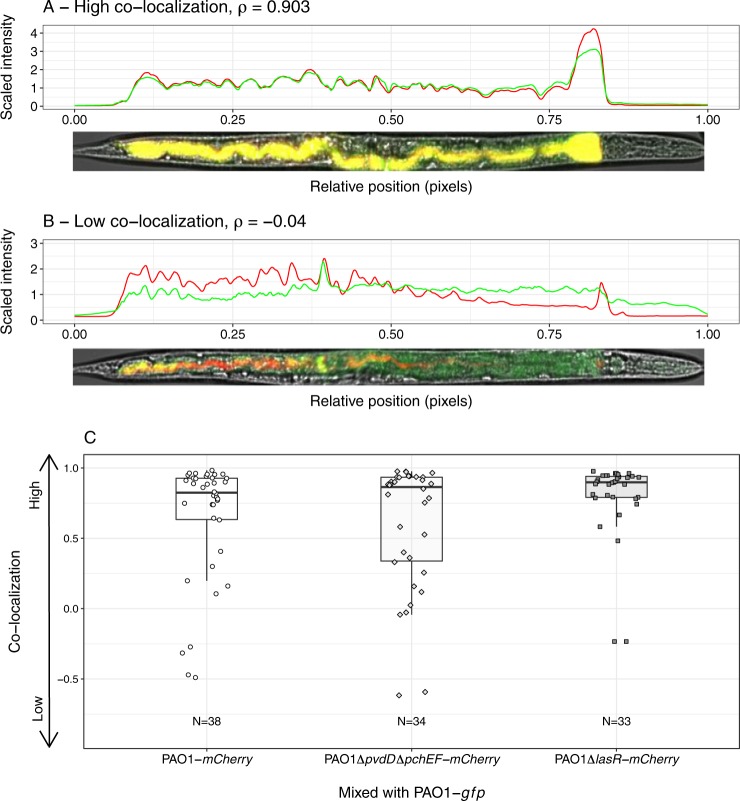

Strain co-localization is generally high within the host, but varies substantially across individuals

In-vitro studies have shown that spatial proximity of cells is crucial for efficient compound sharing [59, 60]. We thus assessed the co-localization of strains in mixed infections inside the gut (Fig. 6). We found that all worms were colonized by both strains, and that the level of co-localization ρ (from tail to head) was generally high, although it varied substantially across individuals (Fig. 6a, b). Similar co-localization patterns emerged for all three strain combinations tested, highlighting that the type of competitor did not influence the degree of strain co-localization in the host gut (Fig. 6c; ANOVA, F2,102 = 2.17, p = 0.119). While our measure of co-localization has some limitations as it does not reveal physical proximity at the single cell level, and is based on a 2D projection of a 3D organ, it clearly suggests that competing cells are close to one another, and that social interactions could occur between them.

Fig. 6.

Spatial structure of mixed infections in the nematode gut. a, b Illustrative examples of C. elegans individuals infected with a mixture of GFP-labeled and mCherry-labeled strains. Each worm was computationally straightened and fluorescence intensity values were extracted for each pixel from tail (X = 0) to head (X = 1). We then calculated the Spearman correlation coefficient ρ between the intensity values in the two fluorescence channels across pixels, as our estimate of strain colocalization. Examples show worms with high (a) and low (b) degrees of colocalization. c Patterns of colocalization levels varied substantially between individuals, but did not differ across strain combinations (p = 0.119: wildtype PAO1-mCherry vs.: (i) wildtype PAO1-gfp (circles), (ii) PAO1ΔpvdDΔpchEF-mCherry (diamonds) or (iii) PAO1ΔlasR-mCherry (squares). Each data point represents an individual worm. Data stems from three independent experiments, with 12 replicates each

Discussion

We developed a live imaging system that allows us to track host colonization by pathogenic bacteria (P. aeruginosa) and their expression of virulence factors inside hosts (C. elegans). We used this system to focus on the role of secreted virulence factors, which can be shared as public goods between bacterial cells, and examined competitive dynamics between virulence factor producing and non-producing strains in the host. We found that siderophores (pyoverdine and pyochelin) and the Las and Rhl QS-systems (i) are expressed inside the host; (ii) affect the ability to colonize and reside within the nematodes; (iii) allow non-producers to benefit from virulence factors secreted by producers in mixed infections; but (iv) do not allow non-producers to cheat and outcompete producers. Our results have implications for both the understanding of bacterial social interactions within hosts, and therapeutic approaches that aim to manipulate social dynamics between strains for infection control.

Numerous in-vitro studies have shown that bacterial cooperation can be exploited by cheating mutants that no longer express the social trait, but benefit from the cooperative acts performed by others [3, 11, 12, 55, 61–65]. These findings contrast with our observations that the spread of non-producers was constrained within infections. There are multiple ways to explain this constraint. First, increased spatial structure can limit the diffusion of secreted metabolites and lead to the physical separation of cooperators and cheats [63]. Both effects result in metabolites being shared more locally among cooperative individuals. The physical separation of strains seemed to explain the results of Zhou et al. [20], where QS-mutants of Bacillus thuringiensis infecting caterpillars could not exploit metabolites from producers. Conversely, physical separation seemed low in our study system (Fig. 6), and therefore unlikely explains why cheats could not spread. While we solely focussed on proximity patterns inside hosts, it is important to note that processes at the meta-population level such as bottlenecking [54, 66], can reduce the probability of different strains ending up in the same host, and thus further compromise cheat success.

Second, negative frequency-dependent selection could explain why the spread of virulence factor negative mutants is constrained [55]. This scenario predicts that cheats only experience a selective advantage when rare, but not when common. The reasoning is that non-producers can only efficiently exploit public goods when surrounded by many producers. Our competition experiments indeed provide indirect evidence for negative frequency-dependent selection in the nematode gut (Fig. 5b). Specifically, we observed that bacterial load was reduced when producers occurred at low frequency early during infection (6 hpe), a result confirming that non-producers are worse host colonizers than producers. These correlations disappeared during the competition period (48 hpe), indicating that rare producers might have experienced a selective advantage and increased in relative frequency, while common producers lost and decreased in frequency.

Third, the relatively low bacterial density in the gut could further compromise the ability of non-producers to cheat (Figs. 1d, 5b). Low cell density restricts the sharing and exploitation of secreted compounds [67, 68]. Mechanisms responsible for the low bacterial density in the gut (Figs. 1d, 5b) could include the peristaltic activity of the gut, expelling a part of the pathogen population and the host immune system, killing a fraction of the bacteria [69].

Fourth, our analysis reveals that, although siderophores and QS-systems play a role in host colonization, they are not essential (Fig. 4). Moreover, the expression of pyoverdine and QS-systems declined over time (Fig. 2). These two observations indicate that the benefits of cheating might be fairly low, and that the costs of virulence factor production are reduced at later stages of the infection. Thus, bacteria might switch from production to recycling of already secreted public goods [70, 71], an effect that can hamper the spread of cheats.

Finally, we show that the regulatory linkage between traits is an important factor to consider when predicting the putative advantage of non-producers [72, 73]. For instance, P. aeruginosa pyoverdine-negative-mutants upregulated pyochelin production to compensate for the lack of their primary siderophore (Fig. 3). Thus, if pyoverdine-negative mutants evolve de novo, their spread as cheats could be hampered because they invest in pyochelin as an alternative siderophore [74]. For QS, meanwhile, we observed that the absence of a functional Las-system resulted in the concomitant collapse of the Rhl-system. Although lasR mutants could be potent cheats, as they are deficient for multiple social traits, their spread might be hampered because QS-systems also regulate non-social traits, important for individual fitness [75].

When relating our insights to previous studies, it turns out that earlier work produced mixed results with regard to the question whether siderophore-deficient and QS-deficient mutants can spread within infections. While Harrison et al. [15, 21] (pyoverdine, P. aeruginosa in Galleria mellonella and ex-vivo infection models) and Zhou et al. [20] (QS, B. thuringiensis in Plutella xylostella) showed that the spread of non-producers is constrained, Rumbaugh et al. [16, 17] (QS; P. aeruginosa in mice), Pollitt et al. [19] (QS, Staphylococcus aureus in G. mellonella) and Diard et al. [18] (T3SS-driven inflammation, Salmonella typhimorium in mice) demonstrated cases where non-producers spread to high frequencies in host populations. While the reported results were based on strain frequency counts before and after competition, we here show that information on social trait expression, temporal infection dynamics, and physical interactions among strains within hosts are essential to understand whether social traits are important and exploitable in a given system. We thus posit that more such detailed approaches are required to understand the importance of bacterial social interactions across host systems and infection contexts and explain differences between them.

A deeper understanding of bacterial social interactions inside hosts is particularly relevant for novel therapeutic approaches that seek to take advantage of cooperator–cheat dynamics inside hosts to control infections. For instance, it was proposed that strains deficient for virulence factors could be introduced into established infections [24]. These strains are expected to spread because of cheating, thereby reducing the overall virulence factor availability in the population and the damage to the host. Our results reveal that virulence-factor-negative strains, although eventually gaining a benefit from producer strains, are unable to spread in populations. Another therapeutic approach involves the specific targeting of secreted virulence factors [25, 27]. This approach is thought to reduce damage to the host and to compromise resistance evolution [30]. Resistant mutants, resuming virulence factor production, are not expected to spread because they would act as cooperators, sharing the benefit of secreted goods with susceptible strains [76–78]. Our results yet indicate that such resistant mutants could get local benefits and thus increase to a certain frequency in the population [31]. These confrontations show that the identification of key parameters driving social interactions across hosts and infection types is of utmost importance to predict the success of ‘cheat therapies’ and anti-virulence strategies targeting secreted public goods.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments and the Center of Microscopy and Image Analysis (University of Zürich) for support with image acquisition and advice on image analysis.

Funding

This project has received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. PP00P3_165835 and 31003A_182499 to RK and no. P2ZHP3_174751 to ETG), and the European Research Council under the grant agreement no. 681295 (to RK).

Data availability

All raw data sets have been deposited in the Figshare repository (10.6084/m9.figshare.8068715.v1).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chiara Rezzoagli, Email: chiara.rezzoagli@uzh.ch.

Rolf Kümmerli, Phone: +41 44 635 48 01, Email: rolf.kuemmerli@uzh.ch.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-019-0442-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science. 1995;268:1899–902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu HJ, Wang AHJ, Jennings MP. Discovery of virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diggle SP, Griffin AS, Campbell GS, West SA. Cooperation and conflict in quorum-sensing bacterial populations. Nature. 2007;450:411–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flemming HC, Wingender J, Szewzyk U, Steinberg P, Rice SA, Kjelleberg S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:563–75. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henkel JS, Baldwin MR, Barbieri JT. Toxins from bacteria. EXS. 2010;100:1–29. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8338-1_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granato ET, Harrison F, Kümmerli R, Ross-Gillespie A. Do bacterial “Virulence Factors” always increase virulence? A meta-analysis of pyoverdine production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a test case. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1952. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Köhler T, Buckling A, van Delden C. Cooperation and virulence of clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6339–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811741106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raymond B, West SA, Griffin AS, Bonsall MB. The dynamics of cooperative bacterial virulence in the field. Science. 2012;337:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1218196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison F. Bacterial cooperation in the wild and in the clinic: Are pathogen social behaviours relevant outside the laboratory? BioEssays. 2013;35:108–12. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West SA, Diggle SP, Buckling A, Gardner A, Griffin AS. The social lives of microbes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2007;38:53–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghoul M, Griffin AS, West SA. Toward an evolutionary definition of cheating. Evolution. 2014;68:318–31. doi: 10.1111/evo.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Özkaya Ö, Balbontín R, Gordo I, Xavier KB. Cheating on cheaters stabilizes cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Curr Biol. 2018;26:2070–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckling A, Brockhurst MA. Kin selection and the evolution of virulence. Heredity. 2008;100:484–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leggett HC, Brown SP, Reece SE. War and peace: social interactions in infections. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2014;369:20130365. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison F, Browning LE, Vos M, Buckling A. Cooperation and virulence in acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. BMC Biol. 2006;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rumbaugh KP, Diggle SP, Watters CM, Ross-Gillespie A, Griffin AS, West SA. Quorum sensing and the social evolution of bacterial virulence. Curr Biol. 2009;19:341–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rumbaugh KP, Trivedi U, Watters C, Burton-Chellew MN, Diggle SP, West SA. Kin selection, quorum sensing and virulence in pathogenic bacteria. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279:3584–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diard M, Garcia V, Maier L, Remus-Emsermann MNP, Regoes RR, Ackermann M, et al. Stabilization of cooperative virulence by the expression of an avirulent phenotype. Nature. 2013;494:353–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollitt EJG, West SA, Crusz SA, Burton-Chellew MN, Diggle SP. Cooperation, quorum sensing, and evolution of virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2014;82:1045–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01216-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou L, Slamti L, Nielsen-LeRoux C, Lereclus D, Raymond B. The social biology of quorum sensing in a naturalistic host pathogen system. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2417–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison F, McNally A, Da Silva AC, Heeb S, Diggle SP. Optimised chronic infection models demonstrate that siderophore ‘cheating’ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is context specific. ISME J. 2017;11:2492–509. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen SB, Marvig RL, Molin S, Krogh Johansen H, Griffin AS. Long-term social dynamics drive loss of function in pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10756–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508324112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen SB, Ghoul M, Marvig RL, Bin LeeZ, Molin S, Johansen HK, et al. Privatisation rescues function following loss of cooperation. Elife. 2018;7:e38594. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown SP, West Sa, Diggle SP, Griffin AS. Social evolution in micro-organisms and a Trojan horse approach to medical intervention strategies. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 2009;364:3157–68. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen RC, Popat R, Diggle SP, Brown SP. Targeting virulence: can we make evolution-proof drugs? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:300–8. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Granato ET, Ziegenhain C, Marvig RL, Kümmerli R. Low spatial structure and selection against secreted virulence factors attenuates pathogenicity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J. 2018;12:2907–18. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.André JB, Godelle B. Multicellular organization in bacteria as a target for drug therapy. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:800–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00783.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clatworthy AE, Pierson E, Hung DT. Targeting virulence: a new paradigm for antimicrobial therapy. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:541–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:117–28. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pepper JW. Drugs that target pathogen public goods are robust against evolved drug resistance. Evol Appl. 2012;5:757–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2012.00254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezzoagli C, Wilson D, Weigert M, Wyder S, Kümmerli R. Probing the evolutionary robustness of two repurposed drugs targeting iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Evol Med Public Heal. 2018;1:246–59. doi: 10.1093/emph/eoy026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan MW, Ausubel FM. Caenorhabditis elegans: a model genetic host to study Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:29–34. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ewbank JJ. Tackling both sides of the host–pathogen equation with Caenorhabditis elegans. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:247–56. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papaioannou E, Utari P, Quax W. Choosing an appropriate infection model to study quorum sensing inhibition in Pseudomonas infections. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:19309–40. doi: 10.3390/ijms140919309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Félix M-A, Braendle C. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R965–R969. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portal-Celhay C, Bradley ER, Blaser MJ. Control of intestinal bacterial proliferation in regulation of lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:715–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimenez PN, Koch G, Thompson JA, Xavier KB, Cool RH, Quax WJ. The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:46–65. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer JM, Neely A, Stintzi A, Georges C, Holder IA. Pyoverdin is essential for virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1996;64:518–23. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.518-523.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takase H, Nitanai H, Hoshino K, Otani T. Impact of siderophore production on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in immunosuppressed mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1834–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.4.1834-1839.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornelis P, Dingemans J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapts its iron uptake strategies in function of the type of infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith RS, Iglewski BH. P. aeruginosa quorum-sensing systems and virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:56–60. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alibaud L, Köhler T, Coudray A, Prigent-Combaret C, Bergeret E, Perrin J, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes identified in a Dictyostelium host model. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:729–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J, Zhang L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell. 2015;6:26–41. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0100-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaborin A, Romanowski K, Gerdes S, Holbrook C, Lepine F, Long J, et al. Red death in Caenorhabditis elegans caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6327–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813199106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirienko NV, Kirienko DR, Larkins-Ford J, Wahlby C, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas aeruginosa disrupts Caenorhabditis elegans iron homeostasis, causing a hypoxic response and death. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:406–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cezairliyan B, Vinayavekhin N, Grenfell-Lee D, Yuen GJ, Saghatelian A, Ausubel FM. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazines that kill Caenorhabditis elegans. PLOS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003101. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu J, Cai X, Harris TL, Gooyit M, Wood M, Lardy M, et al. Disarming Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factor LasB by leveraging a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Chem Biol. 2015;22:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology. WormBook. 2006. p 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Portman DS. Profiling C. elegans gene expression with DNA microarrays. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology. WormBook. 2006. p 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Sommer C, Strähle C, Köthe U, Hamprecht FA. ilastik: interactive learning and segmentation toolkit. Eighth IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). Proceedings. 2011. p 230–3.

- 52.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preibisch S, Saalfeld S, Tomancak P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquisitions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1463–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vega NM, Gore J. Stochastic assembly produces heterogeneous communities in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. PLOS Biol. 2017;15:e2000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ross-Gillespie A, Gardner A, West SA, Griffin AS. Frequency dependence and cooperation: theory and a test with bacteria. Am Nat. 2007;170:331–42. doi: 10.1086/519860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kocsis E, Trus BL, Steer CJ, Bisher ME, Steven AC. Image averaging of flexible fibrous macromolecules: the clathrin triskelion has an elastic proximal segment. J Struct Biol. 1991;107:6–14. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(91)90025-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013.

- 58.Dumas Z, Ross-Gillespie A, Kümmerli R. Switching between apparently redundant iron-uptake mechanisms benefits bacteria in changeable environments. Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280:20131055. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Gestel J, Weissing FJ, Kuipers OP, Kovács ÁT. Density of founder cells affects spatial pattern formation and cooperation in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. ISME J. 2014;8:2069–79. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weigert M, Kümmerli R. The physical boundaries of public goods cooperation between surface-attached bacterial cells. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284:20170631. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Griffin AS, West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation and competition in pathogenic bacteria. Nature. 2004;430:1024–7. doi: 10.1038/nature02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sandoz KM, Mitzimberg SM, Schuster M. Social cheating in Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15876–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kümmerli R, Griffin AS, West Sa, Buckling A, Harrison F. Viscous medium promotes cooperation in the pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:3531–8. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Popat R, Crusz SA, Messina M, Williams P, West SA, Diggle SP. Quorum-sensing and cheating in bacterial biofilms. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279:4765–71. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Brien S, Luján AM, Paterson S, Cant MA, Buckling A. Adaptation to public goods cheats in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc R Soc B. 2017;284:20171089. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Leeuwen E, O’Neill S, Matthews A, Raymond B. Making pathogens sociable: The emergence of high relatedness through limited host invasibility. ISME J. 2015;9:2315–23. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ross-Gillespie A, Gardner A, Buckling A, West SA, Griffin AS. Density dependence and cooperation: theory and a test with bacteria. Evolution. 2009;63:2315–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scholz RL, Greenberg EP. Sociality in Escherichia coli: enterochelin is a private good at low cell density and can be shared at high cell density. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2122–8. doi: 10.1128/JB.02596-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM. Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Imperi F, Tiburzi F, Visca P. Molecular basis of pyoverdine siderophore recycling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20440–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908760106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kümmerli R, Brown SP. Molecular and regulatory properties of a public good shape the evolution of cooperation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18921–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011154107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindsay RJ, Kershaw MJ, Pawlowska BJ, Talbot NJ, Gudelj I. Harbouring public good mutants within a pathogen population can increase both fitness and virulence. Elife. 2016;5:1–25. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.dos Santos M, Ghoul M, West SA. Pleiotropy, cooperation and the social evolution of genetic architecture. PLOS Biol. 2018;16:e2006671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross-Gillespie A, Dumas Z, Kümmerli R. Evolutionary dynamics of interlinked public goods traits: an experimental study of siderophore production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Evol Biol. 2015;28:29–39. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dandekar AA, Chugani S, Greenberg PE. Bacterial quorum sensing and metabolic incentives to cooperate. Science. 2012;338:264–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1227289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mellbye B, Schuster M. The sociomicrobiology of antivirulence drug resistance: a proof of concept. MBio. 2011;2:e00131–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00131-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gerdt JP, Blackwell HE. Competition studies confirm two major barriers that can preclude the spread of resistance to quorum-sensing inhibitors in bacteria. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:2291–9. doi: 10.1021/cb5004288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ross-Gillespie A, Weigert M, Brown SP, Kümmerli R. Gallium-mediated siderophore quenching as an evolutionarily robust antibacterial treatment. Evol Med Public Heal. 2014;2014:18–29. doi: 10.1093/emph/eou003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw data sets have been deposited in the Figshare repository (10.6084/m9.figshare.8068715.v1).