Abstract

Impaired control over drinking is a significant marker of alcohol use disorder (AUD), and a potential target of intervention (Heather, Tebbutt, Mattick, & Zamir, 1993; Leeman, Toll, Taylor, & Volpicelli, 2009). Impaired control may be related to, but conceptually distinct from impulsivity (Leeman, Patock-Peckham, & Potenza, 2012; Leeman, Ralevski, et al., 2014). However, the relationship between impaired control, impulsivity, and alcohol consumption, particularly in non-dependent drinkers is less clear. This study aimed to characterize these relationships using a free-access intravenous alcohol self-administration (IV-ASA) paradigm in non-dependent drinkers (N = 48). Results showed individuals with higher self-reported impaired control achieved higher blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) during the IV-ASA session and reported greater hedonic subjective responses to alcohol. Higher impaired control was also associated with greater positive urgency and reward sensitivity. Moderated-mediation analysis showed that the relationship between positive urgency and peak BAC was mediated by impaired control, and partially moderated by subjective alcohol response. These findings highlight the critical role of impaired control over drinking on alcohol consumption and subjective responses in non-dependent drinkers.

Keywords: Impaired Control, Self-administration, Alcohol, Impulsivity, Alcohol Response

Introduction

Substance use disorders have been characterized as chronic relapsing conditions which cycle between binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation stages (Koob & Le Moal, 2008). As non-dependent drinkers transition to dependence and enter the cycle of addiction, impulsive behavior is compounded by compulsive behavior, and this shift is associated with impairment of executive control processes. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is associated with impairment in control over drinking, decision making, and impulsivity. Impaired control can be defined as “a breakdown of the intention to limit alcohol consumption in a particular situation” (Heather et al., 1993). Impaired control may be a facet of a broader failure of behavioral control (Patock-Peckham, Cheong, Balhorn, & Nagoshi, 2001) (Fillmore, 2003). Impaired control is a significant marker of alcohol use disorder, and an important target of interventions for decreasing alcohol use (Heather & Dawe, 2005) (Leeman et al., 2009). Although a separate construct, impaired control has been linked to impulsivity (Leeman et al., 2012; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Impaired control is described as more of a loss of control over the intention to abstain whereas impulsivity is a personality trait and a broader concept. Past work has shown impaired control to be an important mediator of the relationship between response impulsivity (difficulty inhibiting thoughts or behaviors such as positive and negative urgency) and alcohol use in young heavy drinkers (Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006; J. D. Wardell, Quilty, & Hendershot, 2016). The association of impaired control with alcohol use and problems is also moderated by self-reported sensitivity to alcohol (J. D. Wardell, Quilty, & Hendershot, 2015).

Impulsivity has been defined in many ways, including as “a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli without regard for the negative consequences of these reactions” (Moeller, Barratt, Dougherty, Schmitz, & Swann, 2001). Impulsivity has been shown to influence alcohol outcomes. Alcohol dependent individuals have exhibited poor impulse control and overall more impulsivity in relation to the domains of motor, non-planning, and attentional impulsivity than healthy controls (Bjork, Hommer, Grant, & Danube, 2004; Duka, Townshend, Collier, & Stephens, 2003; Salgado et al., 2009). The link between impulsivity and alcohol consumption is present in non-dependent drinkers as well (Stangl et al., 2016) (Reed, Levin, & Evans, 2012).

An additional related component of impulsivity is reward sensitivity (Dawe, Gullo, & Loxton, 2004). Gray’s theory discusses two systems in the brain that control behavior, the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) and the behavioral approach system (BAS) (Jeffrey A. Gray, 1970; Jeffrey Alan Gray, 1987). The BAS is activated by stimuli associated with reward, and is reflected in greater reward sensitivity, which is associated with alcohol misuse and abuse (Colder et al., 2013; Johnson, Turner, & Iwata, 2003; Jonker & Kuntsche, 2014; Loxton & Dawe, 2006; van Hemel-Ruiter, de Jong, Ostafin, & Wiers, 2015). Reward sensitivity plays an important role in subjective response to alcohol, as those high in reward sensitivity may display greater cue-reactivity to alcohol, such as craving. Subjective response refers to the individual differences in sensitivity to the pharmacological effects of alcohol, and has been shown to explain variance within a population for drinking behavior and alcohol use (Morean & Corbin, 2008, 2010).

While much work has been done demonstrating the association between impaired control and impulsivity with recent drinking history and negative outcomes, the underlying biobehavioral mechanisms have not been well-studied. Examination of these associations in human laboratory models of alcohol self-administration could provide greater sensitivity and unique insights into the impact of impaired control on differences in alcohol consumption, particularly in a non-dependent drinking population. Thus, the aim of our study was to characterize the associations of impaired control of alcohol consumption and impulsivity with recent drinking history and intravenous alcohol self-administration (IV-ASA) in non-dependent drinkers, using the Computer-assisted Alcohol Infusion System (CAIS) method (Zimmermann, O’Connor, & Ramchandani, 2013). This paradigm allows the examination of pharmacologically-driven alcohol consumption (Zimmermann et al., 2013), while controlling for individual variation in alcohol absorption, distribution and elimination, using a physiologically based pharmokinetic (PBPK) model-based algorithm (Ramchandani, Bolane, Li, & O’Connor, 1999). Our previous work has shown the utility of the IV-ASA paradigm to demonstrate the relationship between impulsivity and alcohol consumption (Stangl et al., 2016), as well as to examine the effect of risk factors such as family history of alcoholism, sex, impulsivity and level of response on rate of alcohol consumption (Gowin, Sloan, Stangl, Vatsalya, & Ramchandani, 2017).

In this study, we examined measures of impaired control, impulsivity, and subjective responses to alcohol in a sample of young, non-dependent drinkers who self-administered IV alcohol in our laboratory. Specifically, we hypothesized that individuals with greater self-reported impaired control would self-administer more IV alcohol during the session. We also expected to replicate the association in the literature between impaired control and impulsivity. Next, we wanted to determine if those with greater impaired control had greater subjective response to alcohol in terms of “liking” and “wanting” more IV alcohol. To examine other motivating factors for IV alcohol consumption, we examined the relationship between impaired control measures and sensitivity to punishment and reward. Finally, we used mediation analysis to investigate the inter-relationship between impulsivity, impaired control, and alcohol self-administration measures. In particular, we focused on positive urgency as our impulsivity trait. Positive urgency is the tendency to act rashly to positive mood states (Melissa A. Cyders & Smith, 2007) and it is theorized that young adults are more at risk for hazardous drinking behavior following positive mood states (Bold et al., 2017). Negative urgency predicts an increase in motivation to drink as a way to cope with distress (R. F. Settles et al., 2010). As our sample is a non-dependent drinking population our participants may be using alcohol less for relief drinking and more for celebratory drinking.

Methods

Participants

Male and female healthy volunteers (n=48) ages 21–45 were recruited through newspaper advertisements and the NIH Normal Volunteer Office. The research study was approved through the NIH Addiction Institutional Review Board, and conducted at The National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. All study procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all participants provided written informed consent before participating in the research study.

Potential volunteers were pre-screened via telephone interview and brought into the Clinical Center for further screening in the outpatient clinic. The screening visit included the following: medical history and physical examination, electrocardiogram, blood tests for routine blood chemistry and liver function, and urine screen for illicit drugs. Recent drinking history was assessed using the 90-day Timeline Followback (TLFB) (Sobell & Sobell, 1992), and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor, Kranzler, & Lauerman, 1989). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID) was conducted to assess to evaluate major Axis-I disorders including alcohol or substance abuse and dependence (Spitzer, Gibbon, Skodol, Williams, & First, 2002). Participants seeking treatment for alcohol use, those with current or past alcohol dependence, or other past substance use disorders as determined by the SCID were excluded. Females were required to have normal menstrual cycles. Menstrual cycle data were collected via self-report and females were tested within 10 days of offset of menses for consistency. In addition, all females had a negative urine pregnancy (hCG) test at the start of each study session. Potential participants with any major medical problems, positive hepatitis or HIV test, or current diagnosis of Axis-I psychiatric illness were excluded.

Baseline Measures

During the screening visit, participants completed two self-report measures of impulsivity: (1) the Urgency Premeditation Perseverance Scale (UPPS-P) assessed positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of planning, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking (Lynam et al., 2006), and (2) the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) to assess attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995).

At the start of the study session, participants completed two self-report assessments: (1) the Impaired Control Scale (ICS) (Heather et al., 1993) and (2) the Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ). The Impaired Control Scale has three main subscales: Part I/Attempted control (AC), which measures the degree to control drinking in the past 6 months; Part II/Failed control (FC), which measures the attempts in exercising control over drinking but failing to do so within the past 6 months; and Part III/Perceived control (PC), which measures beliefs about the ability to exert control over drinking in a hypothetical drinking event. (2) The Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ), which assesses reward sensitivity and punishment (Torrubia, Ávila, Moltó, & Caseras, 2001).

Study Session Procedures

The IV-ASA session procedures have been previously described (Stangl et al., 2016; Zimmermann et al., 2008). Participants typically arrived at the day hospital unit on the morning of the day of testing after abstaining from alcohol for 48 hours. A breathalyzer test was performed to ensure a zero-breath alcohol concentration (BrAC). A urine sample was collected for a urine drug screen for all participants and a urine beta-hCG pregnancy test for females; both were required to be negative to continue participation in the study. Participants received a standardized 350 kcal metabolic meal and completed brief medical and drinking history questionnaires. An indwelling intravenous catheter was then inserted into a vein in the antecubital fossa of (preferably) the non-dominant arm using sterile technique. This catheter was used for the alcohol infusion.

The participant was seated in a comfortable chair in a study room in the day hospital unit, out of sight of the infusion pumps and technician’s screen, then instructed in the procedures and limits for selecting alcohol self-infusions in the paradigm. In order to maintain an ambient environment during the self-administration session, participants were allowed to watch television or listen to music. The experimenter was available to monitor the infusion and obtain breathalyzer readings, as well as to answer any questions raised by the participants and to occasionally inquire about the well-being of the participant.

The study employed the CAIS algorithm (Ramchandani et al., 1999), which computes the model parameters for each participant using age, height, weight and sex, and derives the incremental infusion rate profile required to achieve a linear ascent in BAC of 7.5mg% in 2.5 min. for each button press by the participant. Breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) was measured using an Alcotest 6510 handheld breathalyzer (Drager Safety Diagnostics Inc., Irving, TX) approximately every 15 minutes during the session, and entered into the CAIS software program to enable real-time adjustments to the model-based algorithm.

Participants underwent a free-access IV-ASA session, lasting 150 minutes, during the study that began in the early afternoon. The session included a 25 minute priming phase followed by a 125 minute voluntary free-access phase. During the directed priming phase, participants were prompted to push the button to receive four increments of alcohol designed to increase their BAC to ~30 mg% in the first 10 minutes. This allowed a participant to understand the effects of IV alcohol before allowing them free access. This was followed by a 15 minute rest period which allowed the participant to experience the effects of IV alcohol. Following the rest period, participants entered a 125 minute voluntary free-access phase where they could press a button whenever they chose to experience the same increment in BAC increase until the participant pressed the button for another infusion (Zimmermann et al., 2008). Participants were told they could press the button to receive IV infusions of alcohol and they could self-administer alcohol as if they were in a social situation where they usually consume alcohol. The intention was to inform them that they could consume to levels similar to those experienced during a typical drinking episode. Previous research has shown that IV alcohol self-administration behavior reflects realw-orld drinking behavior as assessed by timeline followback (Stangl et al., 2016, Gowin, Sloan et al., 2017). The button was inactivated whenever the next push would yield a BAC increase that exceeded a preset safety limit of 100mg%. The availability of alcohol and the inactivation were imposed with the participant’s knowledge and communicated on the computer screen.

Throughout the session, serial subjective response measures were collected using the Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ). The DEQ measures the subjective effects of certain drugs and in this study measured “Liking” and “Want More” effects of alcohol (Morean et al., 2013) . The DEQ was collected at baseline as well as during the directed priming phase (at the 10 minute and 20 minute time points), and eight times during the IV-ASA session every 15 minutes, with a final post-infusion measure 15 minutes after the IV-ASA had ended. These measures took roughly 5 minutes to complete. Subjects could press for more alcohol during data collection so as to not interfere with the subject’s opportunity to self-administer alcohol.

At the end of the free-access phase, the infusion pump was disconnected and the IV catheter was removed from the participant’s arm. Lunch was provided and serial breathalyzer tests tracked the BrAC. Participants were asked to stay in the hospital for at least two hours after the end of the self-administration or until their BrAC level fell below 20mg%, whichever was later. At this time, participants were debriefed and sent home in a taxi paid for by NIH. The total duration of the session was approximately seven hours. Study participants were instructed to refrain from medications and operating any machinery requiring concentration for at least two hours following their release from the unit.

Data Analysis

The associations among the ICS subscales were assessed using Spearman’s rho correlations. Initial correlations were run between the baseline measures collected (ICS, UPPS-P, BIS Total Score, SPSRQ) (Table 1). Self-administration measures obtained from the free-access IV-ASA paradigm included the estimated peak BAC (mg%) during the free-access phase which is the highest BAC during the free-access phase, and total ethanol consumed in grams (EtOH) during the session.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Participant Demographics, Recent Drinking History, and Impaired Control Scale Measures

| Total (N=48) | Males (N=23) | Females (N=25) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.3 (5.5) | 26.7 (5.9) | 25.9 (5.2) | |

| Years Education | 16.7 (3.2) | 17.2 (4.4) | 16.3 (1.7) | |

| Race | Asian | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Black / African American | 11 | 5 | 6 | |

| White | 28 | 16 | 12 | |

| More than One Race | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Unknown or Unspecified | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 42 | 21 | 21 | |

| AUDIT Score | 5.1 (2.3) | 5.7 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.4) | |

| Recent Drinking History (90-day Timeline Followback) | ||||

| Total Drinks | 70.4 (42.2) | 74.6 (41.8) | 66.6 (43.1) | |

| Drinking Days | 25.4 (12.5) | 23.8 (11.4) | 26.8 (12.5) | |

| Drinks/Drinking Day | 2.8 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.4 (0.9) | |

| Impaired Control Scale Measures | ||||

| Attempted Control | 5.9 (4.4) | 6.7 (3.9) | 5.2 (4.9) | |

| Failed Control | 5.8 (4.6) | 6.7 (4.5) | 5.0 (4.6) | |

| Perceived Control | 5.5 (5.2) | 6.5 (5.0) | 4.7 (5.3) | |

Regression analyses were conducted to examine how impaired control measures AC and FC predict IV-ASA measures, subjective response measures, as well as impulsivity (UPPS-P measure of positive urgency) and sensitivity to reward, while covarying for sex. Recent drinking as measured by the TLFB number of drinking days was evaluated as a covariate but was not significantly associated with any of the measures and was therefore removed from further analyses. The level of significance for all analyses was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Additionally, individuals were categorized as high or low in impaired control based on median splits for AC and FC. Comparison of IV-ASA outcomes, impulsivity measures, DEQ subjective response, and sensitivity to reward and punishment between high and low impaired control groups was done using analysis of variance (ANOVA) while covarying for sex. Bonferroni corrections are reported under analyses for IV-ASA measures and subjective response. Correction for multiple comparisons were not done for the UPPS-P Positive Urgency since it was the only impulsivity measure examined, or the SPSRQ measure as it was exploratory. These results are provided in the supplement. Analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, NY) and the level of significance for all analyses was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Based on the relationships among measures observed in the above analyses, mediation analyses were conducted to better understand the relationships among impulsivity, impaired control, subjective response, and IV-ASA. Peak BAC was the dependent variable. Predictors were chosen based on variables related to both impaired control measures and IV-ASA, while variables that were related to both impulsivity measures and IV-ASA outcomes in preliminary analyses were included as mediators in the mediation model. Age and sex were included as covariates in each model. TLFB drinks per drinking day was later controlled for in follow-up analyses, and although the results were similar, the findings were slightly less robust. As subjective response has been reported in our laboratory and others to be strongly associated with alcohol administration, and in this study showed an association with impaired control, in a second set of analyses DEQ “Liking” and “Want More” were tested as potential moderators of the relationship between impaired control and peak BAC. Analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro developed for SAS by Andrew F. Hayes (available at http://processmacro.org/index.html), which uses a bootstrapping method for estimation of indirect effects (Hayes, 2012). Indirect effects were estimated via bootstrap analysis for 10,000 randomly generated samples, with mediation established if the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval for the indirect parameter estimate did not contain zero. Mediation analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

ICS subscales were significantly correlated with each other. Attempted control was positively correlated with both failed control (r=0.586, p<0.001) and perceived control (r=0.597, p<0.001) while failed control and perceived control were strongly correlated with each other (r=0.813, p=<0.001). This high correlation between FC and PC has been previously reported (Heather, Booth, & Luce, 1998; Heather et al., 1993; Jeffrey D Wardell, Foll, & Hendershot). To avoid multicollinearity issues, we did not include PC in further analyses. Also, AC and FC appear to show unique associations with IV-ASA after controlling for each simultaneously (J. D. Wardell, Le Foll, & Hendershot, 2018). Each one measures distinct aspects of impaired control over drinking over the past six month period, and therefore provide a more integrated evaluation of the effect of impaired control on IV-ASA.

Table 1 shows the demographics and drinking history characteristics of the 48 participants in the study. Also shown are the mean ICS measures. Participants were a young sample (average age=26.3 years), college-educated (average 16.7 years education) and mostly Caucasian, neither Hispanic nor latino. There was one significantly different measure of the TLFB Drinks per Drinking Day between males and females. This was expected due to differences in total body water volume of alcohol distribution between the sexes.

Impaired Control and IV Alcohol Self-Administration

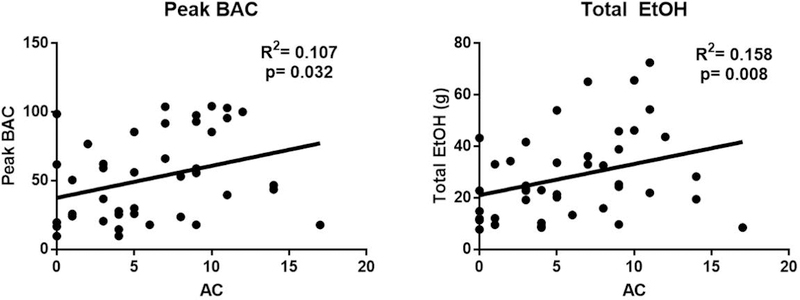

Regression analyses showed that AC and predicted peak BAC (R2=0.107, p=0.032) and total EtOH consumed during the session (R2=0.158, p=0.008) (Figure 1). FC did not predict any of the IV-ASA measures. Sex was not a significant covariate.

Figure 1. Impaired Control and IV Alcohol Self-Administration.

These regressions show how Attempted Control predicted Peak BAC (Panel A) and Total Ethanol consumed (Panel B). Sex was included as an independent variable in these regression models and was not significant.

Analysis of variance showed that the high AC group reached a higher peak BAC (F=5.431, p=0.024, Figure 1A) and consumed more ethanol (F=4.881, p=0.032, Figure 1B) during the IV-ASA session compared to the low AC group. Sex was trending as a significant covariate for the EtOH measure (F=3.702, p=0.061) which was to be expected, as females typically have smaller total body water volumes of alcohol distribution in comparison to males. The high AC group was also more likely to reach a binge level (BrAC=80 mg%) during the session (F=5.311, p=0.026; data not shown) as defined using the NIAAA definition of a binge {Institute on Alcohol, 2004 #2442}. A similar pattern was observed for FC, with the high FC group showing a trend for higher peak BAC (F=3.320, p=0.075, Figure 2C). Bonferroni corrections for AC comparisons remained significant for Peak BAC (F=5.86, p=0.02) and Peak EtOH (F=5.06, p=0.03), and sex was not a significant covariate (data not shown). FC comparisons were trending for Peak BAC but not EtOH.

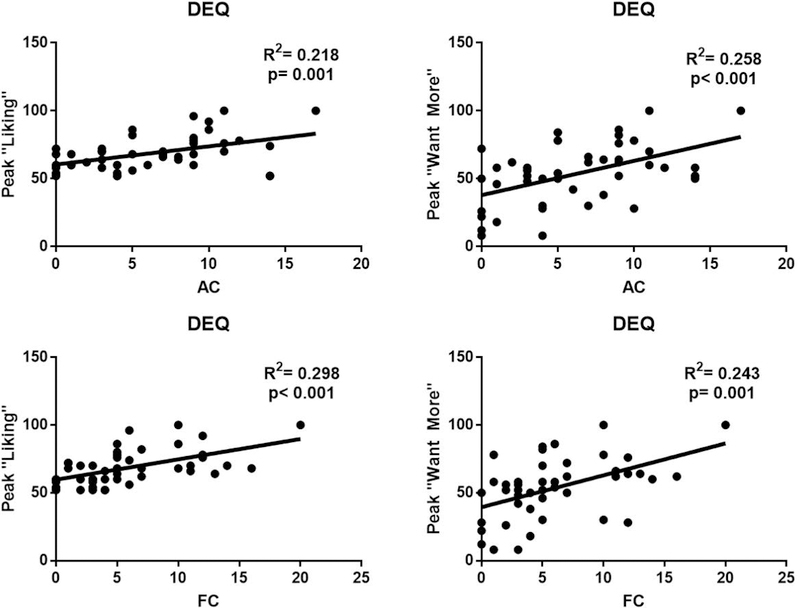

Impaired Control and Subjective Response

Regression analyses revealed that AC and predicted both peak “Liking” and “Want More” alcohol during the session (R2=0.218, p=0.001; R2=0.258, p=0.001, respectively; Figure 2A, 2B) and FC also predicted both peak “Liking” and “Want More” alcohol during the session (R2=0.298, p=0.001; R2=0.243, p=0.001, respectively, Figure 2C, 2D). Sex was not a significant covariate.

The high AC group had greater peak scores for DEQ “Liking” and DEQ “Want More” during IV-ASA (Liking: F=8.847, p=0.005 (Figure 3A); Want More: F=9.583, p=0.003 (Figure 3B)) compared to the low AC group. Similarly, the high FC group had higher peak “Liking” and “Want More” measures during IV-ASA (Liking: F=12.06, p=0.001 (Figure 3C); Want More: F=9.564, p=0.003 (Figure 3D)) compared to the low FC group. Bonferroni corrections for AC comparisons remained significant for DEQ “Liking” (F=10.64, p=0.002) and DEQ “Want More” (F=12.56, p=0.001), and sexwas not a significant covariate (data not shown). FC comparisons also remained significant for DEQ “Liking” (F=11.26, p=0.002) and DEQ “Want More” (F=7.35, p=0.01), with sex not a significant covariate. All effects remained significant after controlling for peak BrAC, except for the effect of FC on DEQ “Want More” which was at trend level (p=0.065).

Impaired Control, Impulsivity and Sensitivity to Punishment and Reward

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix for the impaired control, impulsivity and SPSRQ measures. Significant correlations among these variables were followed up with further analyses as described below.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix Between All Baseline Measures (n=48 participants)

| Measure | Attempted Control | Failed Control | Percieved Control | Negative Urgency | Premeditation | Perseverance | Sensation Seeking | Positive Urgency | BIS Total Score | SPSRQ Punishment | SPSRQ Reward |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted Control | — | ||||||||||

| Failed Control | 0.59** | — | |||||||||

| Perceived Control | 0.56** | 0.87** | — | ||||||||

| Negative Urgency | 0.09 | 0.32* | 0.06 | — | |||||||

| Premeditation | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.61** | — | ||||||

| Perseverance | 0.20 | 0.22 | .003 | 0.48* | 0.68** | — | |||||

| Sensation Seeking | −0.16 | −0.08 | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.14 | — | ||||

| Positive Urgency | 0.27* | 0.42** | 0.23 | 0.63** | 0.57** | 0.56** | 0.11 | — | |||

| BIS Total Score | 0.08 | 0.26 | −0.05 | 0.65** | 0.65** | 0.78** | 0.12 | 0.33 | — | ||

| SPSRQ Punishment | 0.32* | 0.45** | 0.28 | 0.45* | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.59** | 0.30 | — | |

| SPSRQ Reward | 0.41** | 0.31* | 0.08 | 0.40* | 0.23 | 0.47* | 0.04 | 0.57** | 0.32 | 0.25 | — |

p<0.05

p<0.01

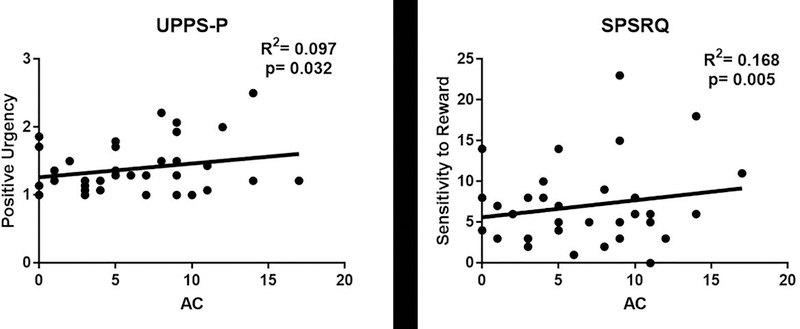

The UPPS-P measure of Positive Urgency predicted Attempted Control scores on the ICS (R2=0.107, p=0.048) (Figure 3A). The Sensitivity to Reward and Punishment Scalepredicted Attempted Control scores on the ICS (R2=0.187, p=0.005) (Figure 3B).

Impaired Control as a Mediator between Impulsivity and IV-ASA

Mediation analyses examined whether impaired control accounted for indirect associations between impulsivity and alcohol self-administration. Positive urgency was selected as the predictor variable as it showed the highest and most consistent association with both IV-ASA measures and all three ICS measures. Mediator variables included AC and FC scores. Table 3 shows the results of mediation models using positive urgency as a predictor and peak BAC as the outcome. Model 1 with AC as the mediator was significant overall (R2=0.28, p = 0.006), and while there was no significant direct effect of positive urgency on peak BAC, there was a significant indirect effect of positive urgency through AC (bootstrapped estimate of b = 9.75, 95% CI = 0.61, 30.37). Model 2 with FC as a mediator was also significant overall (R2=0.28, p = 0.006), and again while there was no direct effect of positive urgency, there was an indirect effect through FC (bootstrapped estimate of b = 8.89, 95% CI = 0.32, 24.09).

Table 3.

Results of Mediation Analyses for Impaired Control Measures for Peak BAC Using Positive Urgency as a Mediator

| Mediator | Effect of Positive Urgency on Mediator | Effect of Mediator on Peak BAC | Indirect Effect Estimate | 95% Bias-corrected confidence interval | Direct Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL 1 | ||||||

| Attempted Control | 4.67* | 2.08# | 9.75* | 0.61, 30.37 | 4.86 n.s. | 14.61 n.s. |

| MODEL 2 | ||||||

| Failed Control | 4.49* | 1.98# | 8.89* | 0.32, 24.09 | 5.72 n.s. | 14.61 n.s. |

p<0.05

p<0.10

n.s.=not significant

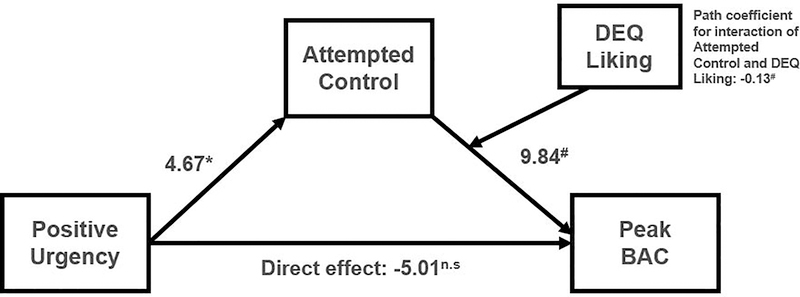

Subjective Response as Moderators of the Relationship between Impaired Control and IV-ASA

Table 4 shows the results of moderated mediation models with DEQ “Liking” and “Want More” as moderators (also see Figure 4). Specifically, the models tested whether DEQ “Liking” or “Want More” moderated the relationship between the mediators (AC or FC) and the outcome (peak BAC). There was a trend level effect of DEQ “Liking” (b coefficient for the interaction = −0.13, p = 0.07) as a moderator of the mediating effect of AC on the relationship between positive urgency and peak BAC. Conditional indirect effects were evaluated at different levels of the moderator (the mean ± one standard deviation from the mean); results showed a significant indirect effect of positive urgency on peak BAC, through AC, at the lower value of DEQ “Liking” (bootstrapped estimate of b = 10.90, 95% CI = 0.44, 42.34) but not at the higher values (Figure 4). DEQ “Liking” also showed a trend level moderating effect for the model using FC as a mediator (b coefficient for the interaction = −0.11, p = 0.07), however, no significant indirect effects were found at any level of the moderator in this model. No moderating effects were found for DEQ “Want More” on either model using AC or FC as mediators.

Table 4.

Moderated Mediation Analyses for Impaired Control Measures for Peak BAC with Positive Urgency as a Predictor and Subjective Response as a Moderator

| Mediator | Moderator | Effect of Positive Urgency on Mediator | Main Effect of Mediator on Peak BAC | Main Effect of Moderator on Peak BAC | Interaction Effect of Moderator and Mediator | Value of Moderator | Indirect Effect estimate | 95% Bias-corrected confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted Control | Liking | 4.67* | 2.08# | 2.30** | −0.13 # | 56.14 (Mean−SD) | 10.90* | 0.44, 42.34 |

| 69.15 (Mean) | 2.78 n.s. | −8.28, 21.56 | ||||||

| 82.16 (Mean+SD) | −5.34 n.s. | −27.66, 11.97 | ||||||

| Wanting | 4.67* | 4.86# | 0.87* | −0.06 n.s. | 31.69 (Mean−SD) | 13.22 n.s. | −0.59, 43.64 | |

| 53.95 (Mean) | 6.59 n.s. | −2.36, 28.14 | ||||||

| 76.21 (Mean+SD) | −0.05 n.s. | −13.44, 16.26 | ||||||

| Failed Control | Liking | 4.36* | 8.81# | 1.98** | −0.11 # | 56.14 (Mean−SD) | 11.27 n.s. | −0.63, 35.92 |

| 69.15 (Mean) | 4.98 n.s. | −5.43, 18.13 | ||||||

| 82.16 (Mean+SD) | −1.31 n.s. | −17.28, 8.48 | ||||||

| Wanting | 4.36* | 5.26* | 0.88** | −0.06 n.s. | 31.69 (Mean−SD) | 13.93 n.s. | −4.43, 44.37 | |

| 53.95 (Mean) | 7.61 n.s. | −5.03, 25.38 | ||||||

| 76.21 (Mean+SD) | 1.29 n.s. | −17.38, 12.80 | ||||||

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.10

n.s.=not significant

Figure 4. Moderated Mediation Model Using DEQ Liking as a Moderator Between Attempted Control and Peak BAC.

This model presents a trend level effect of DEQ “Liking” as a moderator of the mediating effect of attempted control on the relationship between Positive Urgency and Peak BAC. There was a significant indirect effect of positive urgency on Peak BAC through Attempted Control, but only at the lower values of DEQ “Liking”.

Discussion

The results of this human laboratory study provided support to our hypothesis that greater impaired control over drinking would be associated with greater alcohol self-administration in non-dependent drinkers. Subjective response to alcohol was also significantly predicted by impaired control. Specifically, those with higher attempted and failed control had greater liking for alcohol and reported greater wanting for more alcohol during the session. Impaired control over drinking was a significant mediator of the relationship between positive urgency and alcohol self-administration, and there was some suggestion of partial moderation by subjective response to alcohol. Findings from a larger survey sample reported an indirect association between positive and negative urgency measures and self-report alcohol outcomes via impaired control (J. D. Wardell, Quilty, et al., 2015). In addition, these associations were moderated by self-reported sensitivity to alcohol. Our results were able to extend this relationship to drinking in the laboratory using positive urgency as a predictor.

Impaired control is an understudied concept compared to other facets of addiction (Leeman, Beseler, et al., 2014; Leeman et al., 2012). The ICS was developed to measure treatment outcomes and used during treatment to conceptualize lapses in control as a target for intervention (Heather et al., 1998; Heather & Dawe, 2005). However, more recent studies have shown ICS scores to be an important indicator of risk for AUD, even in non-dependent samples (Leeman et al., 2012; Leeman et al., 2009). Our analysis showed complementary results, with higher scores on the ICS associated with more alcohol consumed in the laboratory and subjective hedonic effects of “Liking” and “Want More” alcohol compared with participants with low ICS measures. Subjective response is a risk factor for developing an alcohol use disorder and has been shown to correlate with laboratory alcohol consumption both within-session ((J. D. Wardell, Ramchandani, & Hendershot, 2015) and prospectively (Hendershot, Wardell, McPhee, & Ramchandani, 2017). Interestingly, Attempted Control was a stronger predictor than Failed Control of these measures within our sample. A potential reason may be that our sample is a healthy, non-dependent drinking sample, and therefore may not have as many reported failed attempts to control their drinking, and so attempts to control their drinking may be a more salient measure for this sample. Within our healthy non-dependent sample, we provide a direct association for the role of impaired control in self-administration behavior in the laboratory, whereas this was reported as an indirect relationship between subjective response to alcohol and self-administration behavior for those high on impaired control ((J. D. Wardell, Ramchandani, et al., 2015).

Understanding more about impaired control, even in a sample without AUD, could illuminate research into the cycle of addiction itself. Impaired control is an important component to understanding risky drinking behavior, such as binge drinking episodes. The binge/intoxication phase of Koob’s model of addiction is innately related to impaired control (Koob & Le Moal, 2008). Our findings and those of others suggest that impaired control over drinking may be a potentially useful marker of risk even prior to the development of maladaptive drinking patterns in non-dependent drinkers (Leeman, Beseler, et al., 2014; Leeman et al., 2012)

The relationship between impulsivity and consumption of alcohol has been well documented (Berey, Leeman, Pittman, & O’Malley, 2017; Coskunpinar et al., 2013), as well as the relationship between impaired control and AUD (Heather et al., 1998; Heather & Dawe, 2005; Leeman, Fenton, & Volpicelli, 2007). The importance of impaired control was highlighted in a study showing greater impaired control strengthens the relationship between craving and higher BAC during IV alcohol self-administration (J. D. Wardell, Ramchandani, et al., 2015). Empirical support for impaired control as a mediator between impulsivity and alcohol use problems has been extended upon in the literature (Patock-Peckham, King, Morgan-Lopez, Ulloa, & Moses, 2011; Patock-Peckham & Morgan-Lopez, 2006). Additionally, the trait of positive urgency has shown particular sensitivity to predicting risky behavior and problem drinking in comparison to the other UPPS-P trait measures of impulsivity (Melissa A. Cyders & Smith, 2007; M. A. Cyders et al., 2007). This finding was extended by emphasizing the importance of difficulty inhibiting thoughts or behaviors, or response impulsivity, in which both positive and negative urgency measures from the UPPS-P loaded on to more strongly (J. D. Wardell, Quilty, et al., 2015). Specifically, positive and negative urgency have been associated with greater risk for alcohol use disorder (R. E. Settles et al., 2012; Stautz & Cooper, 2014; Jeffrey D. Wardell, Strang, & Hendershot, 2016). Both urgency measures have little overlap in terms of variance with other impulsivity-related traits (M. A. Cyders et al., 2007). Although there have been similar associations made for the two traits with alcohol use (Coskunpinar, Dir, & Cyders, 2013) and alcohol problems (Curcio & George, 2011), distinctions have been reported whereby these traits have separate risk pathways in terms of increased drinking during the first year of college and mood-based rash action (M. A. Cyders & Smith, 2010; R. F. Settles, Cyders, & Smith, 2010).

Impaired control partially mediated the relationship between response impulsivity and alcohol problems. Most recently, a study examining heavy episodic drinkers who exhibited impaired control by exceeding their given limit BrAC during an IV-ASA session found that craving mediated the relationship between self-reported impaired control and differences beween intended and actual BrAC. Our findings extended the field by highlighting the unique relationship between positive urgency and IV-ASA, and the role of impaired control as a potential behavioral mechanism underlying this relationship. Given our sample of non-dependent drinkers with no current history of mood disorders, positive urgency may be more salient and relevant compared to negative urgency or other facets of impulsive behaviors in this population.

Our results also indicated that those with greater impaired control are more sensitive to reward as measured on the SPSRQ. The relationship between heightened reward sensitivity as measured by the SPSRQ has been previously associated with greater heart rate responses to alcohol (Brunelle et al., 2004) but the association with impaired control is unique and suggests that this personality trait may be a potential factor in the relationship between impaired control and alcohol use. Beyond our association between reward sensitivity and impaired control, we has an initial association between impaired control and punishment. Although interesting, these findings are preliminary and require replication. This result, combined with differences in subjective response to alcohol, specifically “Liking” and “Want More”, suggest that craving and hedonic responses are implicated in individual differences in impaired control, and may therefore drive the motivation to self-administer alcohol in the laboratory. Although these participants are non-dependent drinkers, those with impulsive traits and greater impaired control may be higher risk for AUD.

This research study is not without its limitations. This study was designed to examine the effect of number of factors on IV alcohol self-administration behavior in non-dpeendent behavior. Therefore, it was not prospectively designed to examine the relationship between impaired control and IV-ASA, i.e., the sample was not selected based on levels of impaired control over drinking. However, these findings do suggest that impaired control is an important indicator of alcohol self-administration in non-dependent drinkers. As this study was focused on examining alcohol self-administration in the human laboratory setting, there are no longitudinal data to examine changes in impaired control and relationships with drinking patterns over time. This was also a small sample, and therefore lacked the power to detect more complicated potential interactions that should be addressed in future studies such as sex differences and different levels of alcohol consumption. A larger sample size may also help strengthen our mediation results. Additionally, female participants were tested during a 10-day window following offset of menses and this was estimated based on self-report, which may limit the interpretation of any menstrual cycle-related effects on the relationships examined in this study. Finally, the inclusion of non-dependent drinkers with a relatively homogenous range of drinking and absence of AUD did not allow the examination of differences in impaired control as a function of drinking history. However, the effect of impaired control measures on alcohol self-administration and subjective responses does suggest that impaired control may be an early marker of risk even in this healthy volunteer sample.

In conclusion, these results highlight the importance of impaired control as a relevant potential behavioral mechanism underlying the relationship between positive urgency and alcohol consumption in non-depedent drinkers. Future directions for this research include examining impaired control in positive and negative contexts as predictors of alcohol seeking and consumption as well as developing novel human laboratory paradigms to better understand the temporal relationships and biobehavioral mechanisms of impaired control over drinking and drinking behavior. Ultimately, a better understanding of the mechanisms of impaired control can lead to better and more precise behavioral and pharmacological treatments for alcohol use disorder (Leeman, Beseler, et al., 2014).

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Study Session Timeline.

Figure 2. Impaired Control and IV Alcohol Self-Administration. The high AC group (n=24) showed greater Peak BACs (Panel A) and Total Ethanol consumed (Panel B) compared to the low AC group (n=24). Similarly, the high FC group (n=24) showed greater Peak BAC (Panel C) compared to the low FC group (n=24).

Figure 3. Impaired Control and Subjective Response during IV-ASA. The High AC group (n=24) showed greater Peak “Liking” (Panel A) and Peak “Want More” (Panel B) compared to the low AC group (n=24). Similarly, the High FC group (n=24) showed greater Peak “Liking” (Panel C) and Peak “Want More” (Panel D) compared to the low FC group (n=24).

Figure 4. Impaired Control, Impulsivity and Sensitivity to Reward. The high AC group (n=24) showed significantly greater postive urgency scores compared to the low AC group (n=24) (Panel A). The high AC group (n=24) showed greater sensitivity to reward on the SPSRQ (Panel D) compared to the low AC group (n=24).

Figure 2. Impaired Control and Subjective Response During IV-ASA.

Attempted Control predicted scores of DEQ Peak “Liking” (Panel A) and Peak “Want More” (Panel B). Failed Control also predicted the DEQ measures of Peak “Liking” (Panel C) and Peak “Want More” (Panel D). Sex was included as an independent variable in these regression models and was not significant.

Figure 3. Impaired Control, Impulsivity and Sensitivity to Reward.

The UPPS-P measure Positive Urgency predicted Attempted Control (Panel A) and the SPSRQ measure of Sensitivity to Reward also predicted Attempted Control (Panel B). Sex was included as an independent variable in these regression models and was not significant.

Significance Statement.

These results indicate the importance of examining self-reported impaired control over alcohol consumption in non-dependent drinkers. Particiants higher in self-reported impaired control had greater ratings of urge for alcohol, reward sensitivity and impulsivity, which have been previously shown to be important risk factors for AUD. Therefore, high impaired control may be an important marker for individuals at greater risk for an AUD.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Mary Lee, Dr. Nancy Diazgranados, Dr. David T. George, and Nurse Practitioner LaToya Sewell for medical support and the monitoring safety of the participants, as well as Dr. Reza Momenan for operational support. The authors also would like to thank the staff of the 5-SW day hospital and 1-HALC alcohol clinic at the NIH Clinical Center. Finally, the authors are grateful and appreciative for the clinical oversight and guidance from the late Dr. Daniel Hommer.

Sources of Financial Support:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Division of Clinical and Biological Research (Z1A AA 000466). The CAIS software was developed with support from Sean O’Connor, Martin Plawecki and Victor Vitvitskiy from the Indiana Alcohol Research Center (P60 AA 07611).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Statement:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Babor TF, Kranzler HR, & Lauerman RJ (1989). Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: Comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addict Behav, 14(2), 139–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90043-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berey BL, Leeman RF, Pittman B, & O’Malley SS (2017). Relationships of Impulsivity and Subjective Response to Alcohol Use and Related Problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 78(6), 835–843. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin GS, & Hollander E (2014). Compulsivity, impulsivity, and the DSM-5 process. CNS Spectr, 19(1), 62–68. doi: 10.1017/s1092852913000722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Hommer DW, Grant SJ, & Danube C (2004). Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2-like traits. Alcohol, 34(2–3), 133–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bold KW, Fucito LM, DeMartini KS, Leeman RF, Kranzler HR, Corbin WR, & O’Malley SS (2017). Urgency traits moderate daily relations between affect and drinking to intoxication among young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend, 170, 59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle C, Assaad JM, Barrett SP, C AV, Conrod PJ, Tremblay RE, & Pihl RO (2004). Heightened heart rate response to alcohol intoxication is associated with a reward-seeking personality profile. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 28(3), 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Hawk LW Jr., Lengua LJ, Wiezcorek W, Eiden RD, & Read JP (2013). Trajectories of Reinforcement Sensitivity During Adolescence and Risk for Substance Use. J Res Adolesc, 23(2), 345–356. doi: 10.1111/jora.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, & Cyders MA (2013). Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 37(9), 1441–1450. doi: 10.1111/acer.12131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, & George AM (2011). Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: the mediating role of drinking motives. Addict Behav, 36(10), 959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2007). Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, & Smith GT (2010). Longitudinal validation of the urgency traits over the first year of college. J Pers Assess, 92(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1080/00223890903381825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, & Peterson C (2007). Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess, 19(1), 107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Gullo MJ, & Loxton NJ (2004). Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addict Behav, 29(7), 1389–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duka T, Townshend JM, Collier K, & Stephens DN (2003). Impairment in cognitive functions after multiple detoxifications in alcoholic inpatients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 27(10), 1563–1572. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000090142.11260.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT (2003). Drug abuse as a problem of impaired control: current approaches and findings. Behav Cogn Neurosci Rev, 2(3), 179–197. doi: 10.1177/1534582303257007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George O, & Koob GF (2017). Individual differences in the neuropsychopathology of addiction. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 19(3), 217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowin JL, Sloan ME, Stangl BL, Vatsalya V, & Ramchandani VA (2017). Vulnerability for Alcohol Use Disorder is Associated with Rate of Alcohol Consumption. American Journal of Psychiatry, appiajp201716101180. doi:doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16101180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA (1970). The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 8(3), 249–266. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(70)90069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA (1987). The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. 2012. URL: http://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/SobelTest. [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Booth P, & Luce A (1998). Impaired Control Scale: cross-validation and relationships with treatment outcome. Addiction, 93(5), 761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, & Dawe S (2005). Level of impaired control predicts outcome of moderation-oriented treatment for alcohol problems. Addiction, 100(7), 945–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Tebbutt JS, Mattick RP, & Zamir R (1993). Development of a scale for measuring impaired control over alcohol consumption: a preliminary report. J Stud Alcohol, 54(6), 700–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Turner RJ, & Iwata N (2003). BIS/BAS Levels and Psychiatric Disorder: An Epidemiological Study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 25(1), 25–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1022247919288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker A, & Kuntsche E (2014). Could music potentially serve as a functional alternative to alcohol consumption? The importance of music motives among drinking and non-drinking adolescents. J Behav Addict, 3(4), 223–230. doi: 10.1556/jba.3.2014.4.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, & Le Moal M (2008). Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu Rev Psychol, 59, 29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Beseler CL, Helms CM, Patock-Peckham JA, Wakeling VA, & Kahler CW (2014). A brief, critical review of research on impaired control over alcohol use and suggestions for future studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 38(2), 301–308. doi: 10.1111/acer.12269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Fenton M, & Volpicelli JR (2007). Impaired control and undergraduate problem drinking. Alcohol Alcohol, 42(1), 42–48. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Patock-Peckham JA, & Potenza MN (2012). Impaired control over alcohol use: An under-addressed risk factor for problem drinking in young adults? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 20(2), 92–106. doi: 10.1037/a0026463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Ralevski E, Limoncelli D, Pittman B, O’Malley SS, & Petrakis IL (2014). Relationships between impulsivity and subjective response in an IV ethanol paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 231(14), 2867–2876. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3458-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Toll BA, Taylor LA, & Volpicelli JR (2009). Alcohol-induced disinhibition expectancies and impaired control as prospective predictors of problem drinking in undergraduates. Psychol Addict Behav, 23(4), 553–563. doi: 10.1037/a0017129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loxton NJ, & Dawe S (2006). Reward and punishment sensitivity in dysfunctional eating and hazardous drinking women: associations with family risk. Appetite, 47(3), 361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, & Cyders MA (2006). The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, Schmitz JM, & Swann AC (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, & Corbin WR (2008). Subjective alcohol effects and drinking behavior: the relative influence of early response and acquired tolerance. Addict Behav, 33(10), 1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, & Corbin WR (2010). Subjective response to alcohol: a critical review of the literature. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 34(3), 385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, Sofuoglu M, Rueger SY, & O’Malley SS (2013). The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 227(1), 177–192. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2954-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou H, Nederkoorn C, Havermans R, van der Horst M, & Jansen A (2012). Can’t stop the craving: the effect of impulsivity on cue-elicited craving for alcohol in heavy and light social drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 219(2), 511–518. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2240-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J, Balhorn ME, & Nagoshi CT (2001). A social learning perspective: a model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 25(9), 1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, King KM, Morgan-Lopez AA, Ulloa EC, & Moses JM (2011). Gender-specific mediational links between parenting styles, parental monitoring, impulsiveness, drinking control, and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 72(2), 247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, & Morgan-Lopez AA (2006). College drinking behaviors: mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychol Addict Behav, 20(2), 117–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.20.2.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, & Barratt ES (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol, 51(6), 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani VA, Bolane J, Li TK, & O’Connor S (1999). A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for alcohol facilitates rapid BrAC clamping. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 23(4), 617–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Levin FR, & Evans SM (2012). Alcohol increases impulsivity and abuse liability in heavy drinking women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 20(6), 454–465. doi: 10.1037/a0029087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio G, Jimenez M, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, Martinez I, Avila C, Ferre F, . . . Palomo T (2008). The role of behavioral impulsivity in the development of alcohol dependence: a 4-year follow-up study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 32(9), 1681–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado JV, Malloy-Diniz LF, Campos VR, Abrantes SS, Fuentes D, Bechara A, & Correa H (2009). Neuropsychological assessment of impulsive behavior in abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 31(1), 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Combs JL, Gunn RL, & Smith GT (2012). Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. J Abnorm Psychol, 121(1), 160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, & Smith GT (2010). Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychol Addict Behav, 24(2), 198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, & Sobell M (1992). Timeline Followback: A Technique for Assessing Self Reported Ethanol Consumption, Vol. 17: Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Gibbon ME, Skodol AE, Williams JB, & First MB (2002). DSM-IV-TR casebook: A learning companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text rev: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Stangl BL, Vatsalya V, Zametkin MR, Cooke ME, Plawecki MH, O’Connor S, & Ramchandani VA (2016). Exposure-Response Relationships during Free-Access Intravenous Alcohol Self-Administration in Nondependent Drinkers: Influence of Alcohol Expectancies and Impulsivity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, & Cooper A (2014). Urgency traits and problematic substance use in adolescence: Direct effects and moderation of perceived peer use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 487–497. doi: 10.1037/a0034346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrubia R, Ávila C, Moltó J, & Caseras X (2001). The Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(6), 837–862. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00183-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemel-Ruiter ME, de Jong PJ, Ostafin BD, & Wiers RW (2015). Reward sensitivity, attentional bias, and executive control in early adolescent alcohol use. Addict Behav, 40, 84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Le Foll B, & Hendershot CS (2018). Preliminary evaluation of a human laboratory model of impaired control over alcohol using intravenous alcohol self-administration. J Psychopharmacol, 32(1), 105–115. doi: 10.1177/0269881117723000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Quilty LC, & Hendershot CS (2015). Alcohol sensitivity moderates the indirect associations between impulsive traits, impaired control over drinking, and drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 76(2), 278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Quilty LC, & Hendershot CS (2016). Impulsivity, working memory, and impaired control over alcohol: A latent variable analysis. Psychol Addict Behav, 30(5), 544–554. doi: 10.1037/adb0000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Ramchandani VA, & Hendershot CS (2015). A multilevel structural equation model of within- and between-person associations among subjective responses to alcohol, craving, and laboratory alcohol self-administration. J Abnorm Psychol, 124(4), 1050–1063. doi: 10.1037/abn0000121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Strang NM, & Hendershot CS (2016). Negative urgency mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and problems with alcohol and cannabis in late adolescence. Addict Behav, 56(Supplement C), 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, & Lynam DR (2001). The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(4), 669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann US, Mick I, Vitvitskyi V, Plawecki MH, Mann KF, & O’Connor S (2008). Development and pilot validation of computer-assisted self-infusion of ethanol (CASE): a new method to study alcohol self-administration in humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 32(7), 1321–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00700.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann US, O’Connor S, & Ramchandani VA (2013). Modeling alcohol self-administration in the human laboratory. Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 13, 315–353. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1. Study Session Timeline.

Figure 2. Impaired Control and IV Alcohol Self-Administration. The high AC group (n=24) showed greater Peak BACs (Panel A) and Total Ethanol consumed (Panel B) compared to the low AC group (n=24). Similarly, the high FC group (n=24) showed greater Peak BAC (Panel C) compared to the low FC group (n=24).

Figure 3. Impaired Control and Subjective Response during IV-ASA. The High AC group (n=24) showed greater Peak “Liking” (Panel A) and Peak “Want More” (Panel B) compared to the low AC group (n=24). Similarly, the High FC group (n=24) showed greater Peak “Liking” (Panel C) and Peak “Want More” (Panel D) compared to the low FC group (n=24).

Figure 4. Impaired Control, Impulsivity and Sensitivity to Reward. The high AC group (n=24) showed significantly greater postive urgency scores compared to the low AC group (n=24) (Panel A). The high AC group (n=24) showed greater sensitivity to reward on the SPSRQ (Panel D) compared to the low AC group (n=24).