Abstract

To breed new highly antioxidative common buckwheat cultivars, we selected individual plants from gamma ray-irradiated populations. Selection and propagation were repeated 4 or 5 times. This recurrent selection process resulted in many individuals with enhanced antioxidative activity. Among them, 2 individuals from the forth selection and 9 individuals from the fifth selection were developed into lines with increased antioxidative activities and diverse polyphenolic composition. From these lines, 2 new cultivars ‘Gamma no irodori’ and ‘Cobalt no chikara’ were developed. Furthermore, following the selection of individuals with high rutin contents, ‘Ruchiking’ was developed.

Keywords: antioxidative activity, common buckwheat variety, gamma ray irradiation, individual selection, polyphenol, rutin

Introduction

The genus Fagopyrum comprise several species (Hirose and Ujihara 1998), including common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum. Moench) and Tartary buckwheat (Fagopyrum tartaricum. Gaertn.), which are valuable food crops. Buckwheat has health benefit because of its considerable abundance of protein and minerals. Advances in food science have revealed the functional effects of buckwheat including the fact that buckwheat grains have higher antioxidative activities than other cereal grains (Zieliński and Kozłowska 2000). Additionally, diverse antioxidative compounds have been clarified (Watanabe et al. 1997, Watanabe 1998), and various genetic resources have been evaluated (Morishita et al. 2002, Watanabe et al. 1995).

Recently, common buckwheat cultivars with improved yield and quality have been demanded. Cultivars with high antioxidative activities are desirable because antioxidants protect against oxidative damage caused by free radicals and help prevent lifestyle and adult diseases. In terms of crop improvement, it is generally more difficult to improve quantitative characteristics, (e.g., chemical characteristics) than qualitative characteristics because it is necessary to accumulate polygenes. Additionally, it is more difficult to breed allogamous plant than self-fertilizing plants. However, a study on maize confirmed that long-term selection is effective for improving protein and oil content (Leng 1962). Furthermore, Minami et al. (2001) and Ito et al. (2005) developed high rutin cultivars of common buckwheat. In this study, we selected highly antioxidative plants from gamma ray-irradiated populations, and ultimately developed three new cultivars, namely ‘Gamma no irodori’, ‘Cobalt no chikara’, and ‘Ruchiking’. Analysis of these highly antioxidative cultivars revealed differences in their chemical characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and gamma ray irradiations

We used the common buckwheat cultivar, ‘Botansoba’, of the summer ecotype. This cultivar has a very short growth period, enabling it to be cropped twice a year. In 2001, dry seeds were acutely irradiated for 20 h with 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 Gy in a gamma room (gamma ray irradiation room) at the Institute of radiation Breeding (IRB; Existing Radiation Breeding Division). Irradiated seeds were sown in nursery soil, and the germination rates were determined after 7–10 days. Populations irradiated with 300 Gy, and 400 Gy were used for subsequent selection and propagation. Individual seeds from populations irradiated with 300 Gy, were used for recurrent acute irradiation experiments, which were completed before plants were propagated by isolated culture from May to July in 2002, 2004, 2005 and 2006. Additionally, growing plants from seedlings to maturation were subjected to chronic irradiation for 8 h/day for 5 days with 2.0 (maximum dose for direct planting in gamma field), 1.0, 0.5, and 0.1 Gy/day in a gamma field (facility of gamma ray irradiation field) at the IRB. Seeds were collected from individual plants. Plants irradiated at 2.0 Gy/day were used for further selection and propagation. Individual plants from populations chronically irradiated with 2.0 Gy/day were used for recurrent chronic irradiation experiments.

Selection procedures

In 2001, ‘Botansoba’ seeds that had been irradiated and those that had propagated by isolated culture from May to July, and ripening seeds were collected from individual plants. These collected seeds were sown in August by plant-to-row test. Rows and plants were 60 and 6.5 cm, respectively. Ten seeds were sown in each row, except where there were not enough. Plots were fertilized with N, P2O5 and K2O at 0.28, 0.28, and 0.28 kg/a, respectively. Mature seeds were collected from individual plants for an analysis of their antioxidative activity. Thus, propagation and selections were repeated from 2002 to 2006, exception of 2003. All selection procedures were performed at the IRB.

Preparation of extracts

Collected seeds were dehulled and milled with a mortar and pestle. A 0.6 g sample of flour was extracted with 6 ml of an 80% ethanol solution warmed to 80°C for 30 min in a screw-capped test tube. After cooling, the test tube was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. One-fifth of the supernatant diluted using 80% ethanol was used to measure the antioxidative activity. The remaining flour samples were dried for 3 h at 105°C to determine their water content.

Measurement of antioxidative activity

Antioxidative activities were estimated on the basis of DPPH radical-scavenging activity (Morishita et al. 2007). Specifically, 0.4 mM 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH: Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Japan) was prepared in 99.5% ethanol. The reaction mixture, which was prepared in a test tube, consisted of 0.3 ml of a 0.4 mM DPPH solution, 0.3 ml of a 200 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulpholic acid (MES) (Funakoshi, Ltd., Japan) buffer (pH 6.0), 0.3 ml of 20% ethanol, 0.24 ml of 80% ethanol, and 0.06 ml of a diluted buckwheat flour extract. The final ethanol concentration of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 50%. The reaction was started by the addition of the diluted flour extract. After 20 min, the absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 520 nm on a spectrophotometer (U-3000, Hitachi, Inc., Japan or Du800, Beckman-Coulter Inc., Germany). Control samples were also prepared with 80% ethanol (blank) or 0.2 mM Trolox® (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid, Sigma-Aldrich Com., USA) in 80% ethanol (standard) replacing the buckwheat flour extract. Using a Trolox calibration curve, the DPPH radical-scavenging activity was determined from the decrease in absorbance at 520 nm and expressed as μmol-Trolox/g dry weight (DW).

Evaluation of selected lines by cultivation test

We performed cultivation tests at the IRB. In 2005, 2 individual plants were selected and named 06FE-1 and 06FE-2. In 2006, 9 individual plants were selected and named 07FE-1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11. One individual plant was selected from 06FE-1 and named 07FE-15. All plants were propagated by isolated cultures from May to August 2007. These lines were provided for cultivation tests. ‘Botansoba’ and ‘Hitachiakisoba’ were provided as original and standard cultivars, respectively. These 11 lines and 2 cultivars were sown with 2 replications on 27 August 2007, and 28 August 2008. Row and plants were separated by 60 and 6.5 cm, respectively, for a plant density of 25.6 plant·m−2. Plots were fertilized with N, P2O5 and K2O as above. Seeds were collected from plants and analyzed for their antioxidative activities, as well as for their contents of (−)-epicatechin, (−)-epicatechin gallate, and rutin (Morishita et al. 2007). The agronomic characteristics of the lines and cultivars were investigated in 2008.

Results

Dose response of acute irradiation

In the acute irradiation treatments, the survival rate did not decrease until 200 Gy and decreased with increasing doses (data not shown). The survival rate at 500 Gy, the maximum dose of this experiment, was 27.9%. The lethal dose 50 (LD50) was approximately 400 Gy.

Recurrent selection of highly antioxidative plants

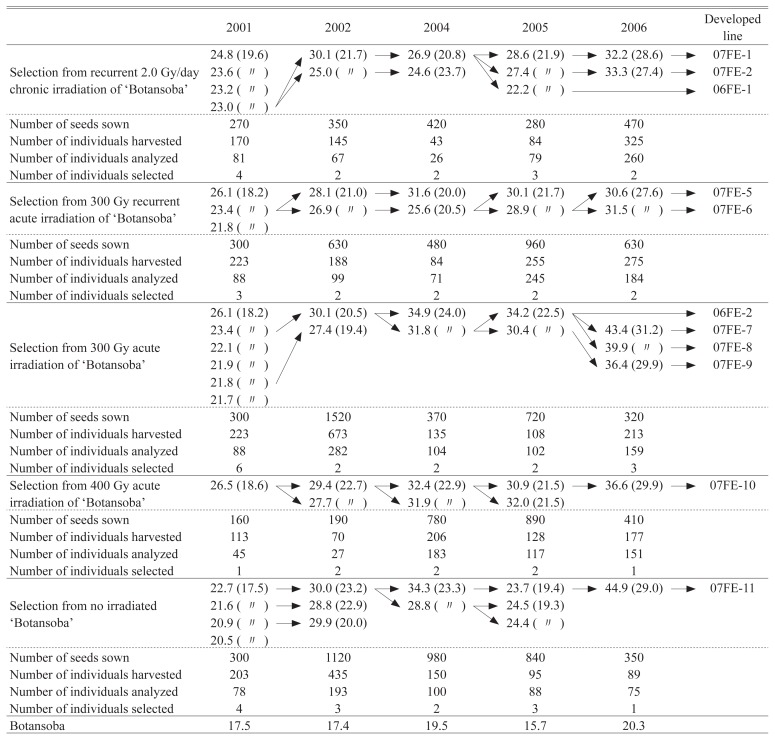

Selections treated with recurrent 2.0 Gy/day chronic irradiation are shown in Table 1. In 2001, 270 seeds were sown and 170 individual plants were harvested, and 81 individual plants were analyzed and 4 individual plants (from 23.0 to 24.8 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2002, 350 seeds were sown and 145 individual plants were harvested, and 67 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (25.0 and 30.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2004, 420 seeds were sown and 43 individual plants were harvested, and 26 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (24.6 and 26.9 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2005, 280 seeds were sown and 84 individual plants were harvested, and 79 individual plants were analyzed and 3 individual plants (22.2, 27.4 and 28.6 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW; one individual plant revealing 22.2 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW was named 06FE-1) were selected. In 2006, 470 seeds were sown and 325 individual plants were harvested, and 260 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (32.2 and 33.3 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW and named 07FE-1 and 07FE-2, respectively) were selected.

Table 1.

The process of selecting for highly antioxidative activity

Unit: μmol-Trolox/gDW. Values in parentheses show the average of the derived populations.

Number of seeds sown in each treatments was calculated with the 10 or fewer seeds in each row rounded up and added.

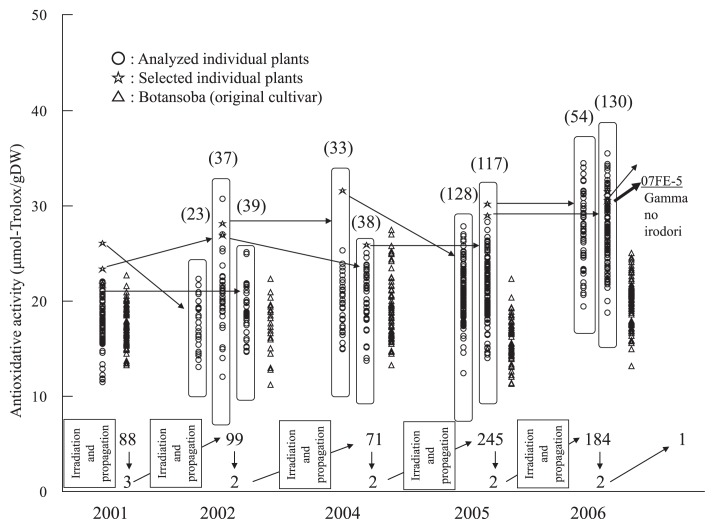

Selections treated with recurrent 300 Gy acute irradiation are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. In 2001, 300 seeds were sown and 223 individual plants were harvested, and 88 individual plants were analyzed and 3 individual plants (21.8, 23.4 and 26.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2002, 630 seeds were sown and 188 individual plants were harvested, and 99 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (26.9 and 28.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2004, 480 seeds were sown and 84 individual plants were harvested, and 71 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (25.6 and 31.6 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2005, 960 seeds were sown and 255 individual plants were harvested, and 245 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (28.9 and 30.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2006, 630 seeds were sown and 275 individual plants were harvested, and 184 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (30.6 and 31.5 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW and named 07FE-5 and 07FE-6, respectively) were selected.

Fig. 1.

Selection process of ‘Gamma no irodori’ during recurrent acute 300 Gy gamma ray irradiation. Values above arrows indicate the number of individuals analyzed, values below arrows indicate the number of selections. Values in parentheses indicate the number of individuals in the derived populations.

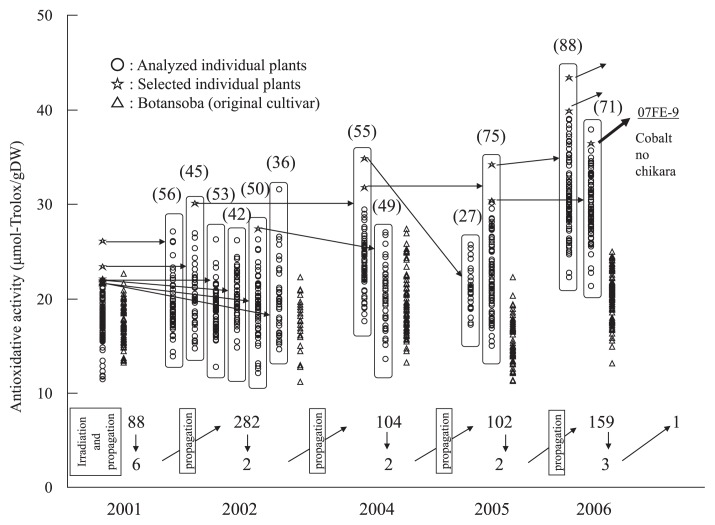

Selections treated with 300 Gy acute irradiation are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2. In 2001, 300 seeds were sown and 223 individual plants were harvested, and 88 individual plants were analyzed and 6 individual plants (from 21.7 to 26.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2002, 1520 seeds were sown and 673 individual plants were harvested, and 282 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (27.4 and 30.1 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2004, 370 seeds were sown and 135 individual plants were harvested, and 104 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (31.8 and 34.9 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2005, 720 seeds were sown and 108 individual plants were harvested, and 102 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (30.4 and 34.2 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected (the higher one was named 06FE-2). In 2006, 320 seeds were sown and 213 individual plants were harvested, and 159 individual plants were analyzed and 3 individual plants (43.4, 39.9 and 36.4 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW and named 07FE-7, 07FE-8 and 07FE-9, respectively) were selected.

Fig. 2.

Selection process of ‘Cobalt no chikara’ during acute 300 Gy gamma ray irradiation. Values above arrows indicate the number of individuals analyzed, values below arrows indicate the number of selections. Values in parentheses indicate the number of individuals in the derived populations.

Selections treated with 400 Gy acute irradiation are shown in Table 1. In 2001, 160 seeds were sown and 113 individual plants were harvested, and 45 individual plants were analyzed and one individual plant (26.5 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) was selected. In 2002, 190 seeds were sown and 70 individual plants were harvested, and 27 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (27.7 and 29.4 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2004, 780 seeds were sown and 206 individual plants were harvested, and 183 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (31.9 and 32.4 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2005, 890 seeds were sown and 128 individual plants were harvested, and 117 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (30.9 and 32.0 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2006, 410 seeds were sown and 177 individual plants were harvested, and 151 individual plants were analyzed and one individual plant (36.6 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW and named 07FE-10) was selected.

Selections from plants not exposed to irradiation are shown in Table 1. In 2001, 300 seeds were sown and 203 individual plants were harvested, and 78 individual plants were analyzed and 4 individual plants (from 20.5 to 22.7 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2002, 1120 seeds were sown and 435 individual plants were harvested, and 193 individual plants were analyzed and 3 individual plants (28.8, 29.9 and 30.0 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2004, 980 seeds were sown and 150 individual plants were harvested, and 100 individual plants were analyzed and 2 individual plants (28.8 and 34.3 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2005, 840 seeds were sown and 95 individual plants were harvested, and 88 individual plants were analyzed and 3 individual plants (23.7, 24.4 and 24.5 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) were selected. In 2006, 350 seeds were sown and 89 individual plants were harvested, and 75 individual plants were analyzed and one individual plant (44.9 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW and named 07FE-11) was selected.

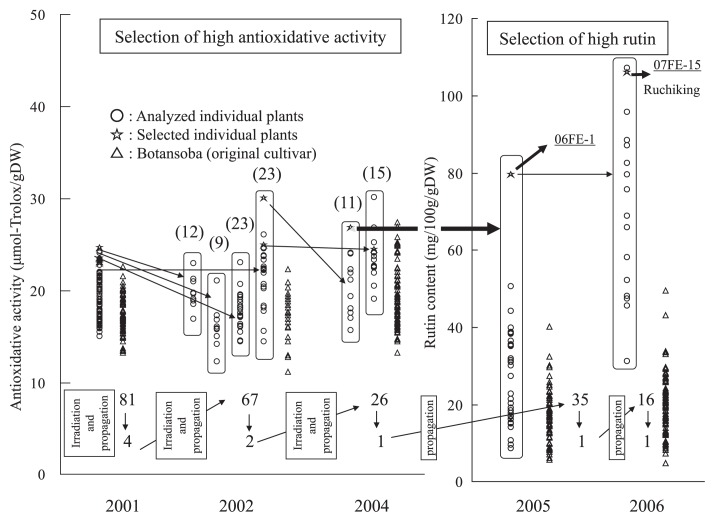

Selection of high-rutin plants from line 06FE-1

The selection process for high rutin is shown in Fig. 3. In 2005, an analysis of the 06FE-1 (22.2 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW: Table 1, Fig. 3) plant revealed a very high rutin content (79.8 mg/100 g DW: Fig. 3). In 2006, one individual plant selected from 16 plants of 06FE-1 had an extremely high rutin content (106.1 mg/100 g DW) and was named 07FE-15.

Fig. 3.

Selection process of ‘Ruchiking’ during recurrent chronic 2.0 Gy/day gamma ray irradiation. High antioxidative activities and high rutin contents were selected in 2001–2004 and 2005–2006, respectively. Values above arrows indicate the number of individuals analyzed, values below arrows indicate the number of selections. Values in parentheses indicate the number of individuals in the derived populations.

Evaluation of selected lines in a cultivation test

The chemical components of the selected lines and ‘Hitachiakisoba’ and ‘Botansoba’ are shown in Table 2. The antioxidative activities of all selected lines were higher than those of ‘Hitachiakisoba’ and ‘Botansoba’ in 2007 and 2008. The highest line was 07FE-10 in 2007 and 07FE-9 in 2008. The (−)-epicatechin and (−)-epicatechin gallate contents of selected lines were also higher than those of ‘Hitachiakisoba’ and ‘Botansoba’. Especially, the (−)-epicatechin contents of 07FE-2 and 07FE-9 were higher than 100 mg/100 g DW, and the (−)-epicatechin gallate contents of 07FE-6 and 07FE-9 were higher than 10 mg/100 g DW in both 2007 and 2008. In contrast, the rutin contents of a few selected lines (07FE-1 and 07FE-9 in 2007 and 07FE-1 and 07FE-10 in 2008) were lower than those of ‘Hitachiakisoba’ and ‘Botansoba’. However, most of the selected lines had higher rutin contents. The highest was 07FE-15, and next one was 07FE-5 in both 2007 and 2008. Thus, there was considerable variability in the polyphenol contents of the selected lines.

Table 2.

Antioxidative activity and contents of (−)-epicatechin, (−)-epicatechin gallate, and rutin of selected lines and cultivars

| Lines and cultivars | Antioxidative activity μmol-Trolox/g DW | (−)-Epicatechin mg/100 g DW | (−)-Epicatechin gallate mg/100 g DW | Rutin mg/100 g DW | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 2007 | 2008 | 2007 | 2008 | 2007 | 2008 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| 06FE-1 | 23.4 | 22.9 | 60.4 | 70.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 50.8 | 49.2 |

| 06FE-2 | 23.3 | 26.3 | 55.3 | 71.7 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 20.2 | 29.8 |

| 07FE-1 | 24.5 | 24.3 | 84.0 | 88.0 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 9.4 | 5.6 |

| 07FE-2* | 28.0 | 23.3 | 102.9 | 100.3 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 19.2 | 21.7 |

| 07FE-5 (Gamma no irodori) | 26.4 | 27.5 | 32.2 | 52.3 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 56.8 | 56.7 |

| 07FE-6 | 27.5 | 26.9 | 54.2 | 76.1 | 13.4 | 15.3 | 28.6 | 38.6 |

| 07FE-7 | 25.9 | 26.7 | 65.9 | 87.2 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 19.5 | 27.4 |

| 07FE-8* | 25.8 | 25.3 | 32.0 | 71.1 | 7.0 | 9.1 | 20.1 | 20.8 |

| 07FE-9 (Cobalt no chikara) | 28.5 | 27.6 | 106.8 | 120.8 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 14.1 | 18.6 |

| 07FE-10* | 29.4 | 24.6 | 101.5 | 97.5 | 10.6 | 7.9 | 18.4 | 12.0 |

| 07FE-11 | 27.6 | 26.9 | 83.1 | 96.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 18.9 | 25.3 |

| 07FE-15 (Ruchiking) | 25.4 | 25.4 | 62.3 | 72.7 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 70.7 | 70.3 |

| Hitachiakisoba | 19.0 | 18.2 | 28.4 | 32.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 18.2 | 17.9 |

| Botansoba | 17.8 | 18.4 | 20.9 | 26.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 17.8 | 20.3 |

: No replication in 2007.

Agronomic characteristics of lines and cultivars

The agronomic characteristics of varieties are shown in Table 3. The flowering time and maturing time of three selected lines were earlier than those of ‘Hitachiakisoba’ and later than those of ‘Botansoba’. Yield was not different significantly among all lines and varieties. Plant height, number of nodes, number of primary branches of selected lines were almost at the same levels as those of ‘Botansoba’ and lower than those of ‘Hitachiakisoba’. While, 1000 seeds weight was different among all varieties, and that of 3 developed varieties were lower than that of ‘Botansoba’.

Table 3.

Agronomic characteristics of cultivars in 2008

| Cultivars | Seeding time m.d | Flowering time m.d | Maturing time m.d | Plant height cm | No. of nodes No./plant |

No. of primary branch No./plant |

Yield kg/a | 1000 seeds weight g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07FE-5 (Gamma no irodori) | 8.28 | 9.11 | 10.20 | 61.7 a | 9.3 a | 3.3 a | 11.8 a | 23.7 a |

| 07FE-9 (Cobalt no chikara) | 8.28 | 9.11 | 10.20 | 65.5 a | 9.9 a | 3.0 a | 9.8 a | 26.9 b |

| 07FE-15 (Ruchiking) | 8.28 | 9.11 | 10.20 | 72.5 a | 9.8 a | 3.0 a | 11.4 a | 28.6 c |

| Hitachiakisoba | 8.28 | 9.12 | 10.23 | 96.2 b | 11.8 b | 3.3 a | 14.5 a | 33.8 e |

| Botansoba | 8.28 | 9.10 | 10.19 | 64.0 a | 9.5 a | 3.0 a | 10.6 a | 29.7 d |

| — | — | — | ** | * | ns | ns | ** |

: Significant at 5% and 1% level, respectively by LSD.

Same letters are not significantly varietal different at the 5% level by LSD.

Registration

07FE-5 was registered as ‘Gamma no irodori’ with high rutin content and relatively low catechins (Table 2) (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2013a). 07FE-9 was registered as ‘Cobalt no chikara’ with high (−)-epicatechin content (Table 2) (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2013b). 06FE-1 was used for further high rutin reselection, and a line with extremely high rutin was developed and named 07FE-15 (Table 2), which was registered as ‘Ruchiking’ (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2013c).

Discussion

This study was performed to develop new highly antioxidative common buckwheat cultivars. In the selection process, although higher antioxidative individuals were detected, some, including the most highly antioxidative individual, could not be selected because fewer than 50 seeds per plant were collected, insufficient for subsequent propagation. We used gamma ray irradiation because a previous study confirmed that gamma rays irradiation can be expected to expand variation (Takagi et al. 1998). We adopted 300 Gy and 400 Gy for recurrent selections because the lethal dose 50% (LD50) of common buckwheat was estimated to be approximately 350 Gy in a previous report (Morishita et al. 2001) and above 400 Gy in this study. Therefore, we did not adopt 500 Gy because it severely inhibited seed propagation. In contrast, irradiated plants could be propagated at all doses of chronic irradiation. Consequently, we adopted the highest chronic irradiation dose, 2.0 Gy/day for recurrent irradiation and selection.

Generally, the contents of chemical components are influenced easily by environmental conditions such as soil fertility, moisture supply and temperature. In this study, the antioxidative activity of ‘Botansoba’ varied from year to year, and the values of selected individuals also varied similarly (Table 1). For example, the activities of ‘Botansoba’ (15.7 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW) and selected individuals were low in 2005, while they were high in 2006 (20.3 μmol-Trolox g−1 DW). Anyways, our recurrent selection process was able to overcome the effect of environmental variations, enabling us to develop highly antioxidative lines and cultivars could be developed.

Various highly antioxidative lines were developed with various (−)-epicatechin contents and high and low rutin contents in this study. Among the analyzed compounds, (−)-epicatechin contributes to the antioxidative activities in common buckwheat (Morishita et al. 2007). As a result, selection for highly antioxidative activity may be caused by the selection of high (−)-epicatechin materials, while the contribution ratio of rutin to antioxidative activity was very low (Morishita et al. 2007). Consequently, rutin was unrelated to antioxidative selection, and low and high lines may be developed incidentally.

In this study, 3 cultivars could be successfully developed from chronic and acute gamma ray irradiated populations. On the other hand, the selection from no irradiated population could be developed high antioxidative line (07FE-11). But this line did not show an outstanding characteristic compared with other lines, we did not register it as a new cultivar. Consequently, we could introduce one example of radiation breeding and demonstrated the effectiveness of mutation breeding by using gamma rays.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. H. Kuwahara for his assistance in the field. This study was financially supported by the Budget for Nuclear Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, based on the screening and counseling by the Atomic Energy Commission.

Literature Cited

- Hirose, T. and Ujihara, A. (1998) Buckwheat flower pictorial. Fagopyrum 15: 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S., Ohsawa, R., Tsutsumi, T., Baba, T., Arakawa, A., Hayashi, K. and Nakamura, E. (2005) A new common buckwheat variety “Toyomusume” with high yield and higher rutin content. Bull. Natl. Agric. Res. Cent. 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, E.R. (1962) Results of long-term selection for chemical composition in maize and their significance in evaluating breeding systems. Z. Pflanzenzuchtg. 47: 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Minami, M., Kitabayashi, H., Nemoto, K. and Ujihara, A. (2001) Breeding of high rutin content common buckwheat, “SunRutin”. Advances in Buckwheat Research (Proc. 8th Intl. Symp. Buckwheat at Chunchon): 367–370. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2013a) Plant Variety Protection. GAMMA NOIRODORI. http://www.hinshu2.maff.go.jp/vips/cmm/apCMM112.aspx?TOUROKU_NO=22872&LANGUAGE=English (accessed June 29, 2018).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2013b) Plant Variety Protection. COBALT NOCHIKARA. http://www.hinshu2.maff.go.jp/vips/cmm/apCMM112.aspx?TOUROKU_NO=22873&LANGUAGE=English (accessed June 29, 2018).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (2013c) Plant Variety Protection. RUCHI KING. http://www.hinshu2.maff.go.jp/vips/cmm/apCMM112.aspx?TOUROKU_NO=22874&LANGUAGE=English (accessed June 29, 2018).

- Morishita, T., Yamaguchi, H. and Degi, K. (2001) The dose response and mutation induction by gamma ray in buckwheat (Proc. 8th Intl. Symp. Buckwheat at Chunchon): 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Hara, T., Suda, I. and Tetsuka, T. (2002) Radical-scavenging activity in common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) harvested in the Kyushu region of Japan. Fagopyrum 19: 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita, T., Yamaguchi, H. and Degi, K. (2007) The contribution of polyphenols to antioxidative activity in common buckwheat and Tartary buckwheat grain. Plant Prod. Sci. 10: 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, Y., Rahman, S.M. and Anai, T. (1998) Construction of novel fatty acid composition in soybean oil by induced mutation. Gamma Field Symp. 37: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M., Sato, A., Ohsawa, R. and Terao, J. (1995) Antioxidative activity of buckwheat seed extracts and its rapid estimate for the evaluation of breeding materials. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi 42: 649–655. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M., Ohshita, Y. and Tsushida, T. (1997) Antioxidant compounds from buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Möench) hulls. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45: 1039–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M. (1998) Catechins as antioxidants from buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) groats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 46: 839–845. [Google Scholar]

- Zieliński, H. and Kozłowska, H. (2000) Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected cereal grains and their different morphological fractions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48: 2008–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]