Abstract

Abdominal surgery represents a high risk for hospital-acquired infections and complication that may compromise the surgery outcome. Patients with recent abdominal surgery have an intestinal dysbiosis. There is evidence that probiotics may counterbalance the impaired microbiota. Therefore, the current survey evaluated the efficacy and safety of Abincol®,an oral nutraceuticalcontaining a probiotic mixture with Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 (1 billion of living cells), Lactobacillus lactis subspecies cremoris LLC02 (800 millions of living cells), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii LDD01 (200 millions of living cells), in 612 outpatients (344 males and 268 females, mean age 58 years) undergoing digestive surgery. Patients took 1 stick/daily for 8 weeks. Abincol® significantly diminished the presence and the severity of intestinal symptoms and improved stool form. In conclusion, the current survey suggests that Abincol® may be considered an effective and safe therapeutic option in the management of patients undergoing digestivesurgery. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: digestive surgery, dysbiosis, microbiota, probiotic, survey

Introduction

It is well known that complications after abdominal surgery, mainly concerning in cancer patients, are often a result of bacterial infections, leading to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality, as well as the duration of hospitalization and the subsequent economic costs (1). The gut pathophysiology exerts a crucial role in this context. Indeed, impaired gut barrier function may lead to an imbalanced intestinal physiology. In addition, bacteria and their toxins may enter the blood stream and provoke systemic inflammatory response, which may lead to multiple organ failure or even death. It has been reported that some patients after open-abdomen surgery have experienced translocation of live bacteria to the mesenteric lymph nodes or to the serosa of the bowel wall (2, 3).

In recent years, there has been growing interest in the human gut microbial ecosystem, which ultimately appears to be involved in both disease onset and progression, as well as in the development of complications. The complex gut ecosystem coexists in a fragile balance (symbiosis), that can easily be disturbed (dysbiosis). Actually, dysbiosis has been linked with severe diseases, not only infections, but also autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders, (4, 5).

In addition, the use of probiotics to prevent and cure the surgery complications has become popular in hospital setting as recently pointed out (6). The rational for probiotics use in abdominal surgery derives from the evidence that probiotics significantly affect gut dysbiosis resulting from both intestinal preparation and abdominal operation. Actually, peri-operatory use of probiotics reduces the mucosal damage consequent to surgery and medications.

Abdominal surgery is also associated with bowel preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis: both have additional detrimental effects on the ecology of commensal bacteria, ranging from self-treated ‘‘functional’’ diarrhoea to life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis (7, 8). Moreover, food restriction, even in the setting of complete intravenous nutrition, leads to a scarcity of macronutrients for the bacteria within the gut, and thus to a relative loss of Firmicutes and to an expansion of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes. All these factors contribute to the severity of intestinal dysbiosis associated to abdominal surgery.

Probiotics are live microbial food supplements, such as nutraceuticals, that may beneficially improve the host by acting on the intestinal microbial balance (9).

Probiotics are able to maintain gut barrier function by restoring intestinal permeability and ameliorating the intestinal anti-inflammatory response and the release of cytokines, and can also maintain the homeostasis of the normal gut microbiota. Therefore, probiotics have been extensively studied as an adjuvant perioperative treatment modality to reduce infectious complications in surgical patients (10). There is therefore evidence that modulation of the intestinal microbiota with probiotics seems to be an effective method to reduce infectious complications in surgical patients. In this regard, probiotics may have an additional indication concerning the endurance of surgical anastomosis as they modulate the oxidative metabolism and peptide metabolism (11). Consistently, Van Praagh and colleagues demonstrated an association between Lachnospiracea and anastomosis failure (12). In addition, a recent review reported a microbiota change including the increase of pathogens and reduction of protective bacteria after abdominal surgery (13).

Abincol® is an oral nutraceuticalcontaining a probiotic mixture with Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 (1 billion of living cells), Lactobacillus lactis subspecies cremoris LLC02 (800 millions of living cells), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii LDD01 (200 millions of living cells) and it has been recently placed on the market.

On the basis of this background, an Italian survey explored the pragmatic approach of a group of gastroenterologists in the management of patients undergoing abdominal surgery in clinical practice. Therefore, the aim of the current survey was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Abincol® in outpatients after digestive surgery.

Materials and Methods

The current survey was conducted in 83 Italian Gastroenterology centers, distributed in the whole Italy, so assuring a wide and complete national coverage, during the fall-winter 2018-2019. Gastroenterologists were asked to recruit all consecutive outpatients visited because of recent digestive surgery.

Patients were consecutively recruited during the specialist visit. The inclusion criteria were: to have recent abdominal surgery, both genders, and adulthood. Exclusion criteria were to have comorbidities and concomitant medications able to interfere the evaluation of outcomes.

Digestive surgery included appendicectomy, polypectomy, hemorrhoidectomy, gastrectomy, adherence lysis, ileum resection, sigma resection, hemicolectomy, and rectal resection.

All patients signed an informed consent. All the procedures were conducted in a real-world setting.

The treatment course lasted 8 weeks. The oral nutraceutical Abincol® (Aurora Biofarma, Milan, Italy) was taken following the specific indications, such as one stick/daily. Patients were visited at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks (T1), and after 8 weeks (T2).

Clinical examination was performed in all patients at T0, T1, and T2. The following parameters were investigated: abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, flatulence, borborygmi, eructation, malaise, weakness, headache. These symptoms were assessed as present/absent and were scored using a four-point scale (0=absent, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe), but for abdominal pain the scale was 5-point (4=very severe). A physical examination of stool was performed using the Bristol stool form scale (16).

Safety was measured by reporting the occurrence of adverse events.

All clinical data were inserted in an internet-platform that guaranteed the patients’ anonymity and the findings’ recording accuracy.

The paired T-test was used. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. Data are expressed as medians and 1th and 3rd quartiles. The analysis was performed using STATA, College Station, Texas, USA.

Results

Globally, 612 outpatients (344 males and 268 females, mean age 58 years) were visited and completed the treatment course.

The frequency of symptoms (abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, flatulence, borborygmi, eructation, malaise, weakness, and headache) at baseline (T0), and at T1 and T2 is reported in Table 1 and 2. In particular, abdominal pain and abdominal bloating were the most common symptoms at baseline. The frequency of both significantly diminished after the treatment course.

Table 1.

Frequency of patients for each symptom at baseline (T0). M=males; F=females, Mean age in years

| N=612 | T0 | |||

| n | % | M/F | Mean age | |

| Abdominal pain | 503 | 82.2% | 282/221 | 58 |

| Abdominal bloating | 464 | 75.8% | 253/211 | 58 |

| Flatulence | 421 | 68.8% | 241/180 | 58 |

| Borborygmi | 352 | 57.5% | 199/153 | 57 |

| Eructation | 325 | 53.1% | 176/149 | 57 |

| Malaise | 206 | 33.7% | 116/90 | 60 |

| Weakness | 140 | 22.9% | 84/56 | 61 |

| Headache | 43 | 7.0% | 26/17 | 57 |

Table 2.

Comparison of proportion of patients with symptoms at baseline (T0), and at T1 and T2

| Symptoms | T0 | T1 | T2 | ||||||

| n | n | % | Diff% | p | n | % | Diff% | p | |

| Abdominal pain | 503 | 319 | 63.4% | -36.6% | <0.001 | 191 | 38.0% | -62.0% | <0.001 |

| Abdominal bloating | 464 | 318 | 68.5% | -31.5% | <0.001 | 185 | 39.9% | -60.1% | <0.001 |

| Flatulence | 421 | 258 | 61.3% | -38.7% | <0.001 | 166 | 39.4% | -60.6% | <0.001 |

| Borborygmi | 352 | 183 | 52.0% | -48.0% | <0.001 | 105 | 29.8% | -70.2% | <0.001 |

| Eructazioni | 325 | 190 | 58.5% | -41.5% | <0.001 | 132 | 40.6% | -59.4% | <0.001 |

| Malaise | 206 | 58 | 28.2% | -71.8% | <0.001 | 14 | 6.8% | -93.2% | <0.001 |

| Weakness | 140 | 39 | 27.9% | -72.1% | <0.001 | 10 | 7.1% | -92.9% | <0.001 |

| Headache | 43 | 7 | 16.3% | -83.7% | <0.001 | 2 | 4.7% | -95.3% | <0.001 |

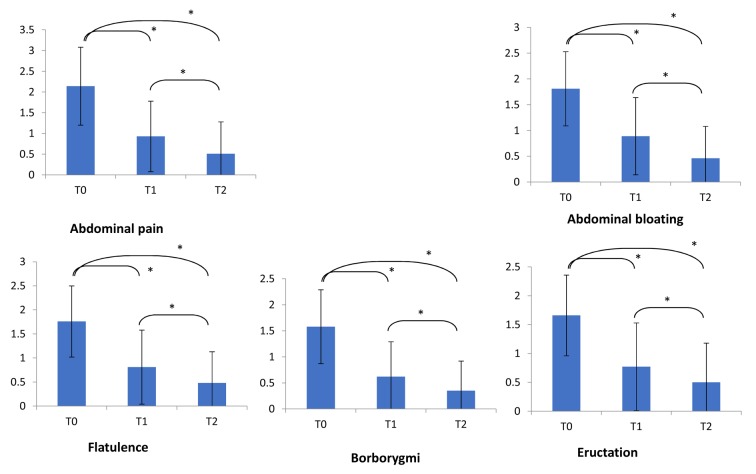

Consistently, the severity of the most relevant symptoms did significantly diminish after the treatment (Figure 1). In particular, abdominal pain and bloating significantly diminished at T1 and T2 (p<0.001 respectively for both symptoms).

Figure 1.

Symptoms severity at baseline (T0), at T1 and T2. Symptoms’ score scale was 0-3 for all symptoms but abdominal pain (0-4). Comparisons were made by paired Wilcoxon test. *= p<0.001

In addition, stool form significantly improved as a normal form (type 3 and 4) was detectable in 25.8% at baseline, in 46.4% at T1, and in 47% at T2 (p<0.001 as linear trend).

The treatment was well tolerated by all patients and no clinically relevant adverse event was reported.

Discussion

There is evidence that any surgery represents a high risk for hospital-acquired infections (HAIs): in fact, surgical site infections (SSIs) are the most frequent HAI in the surgical population, in particular, abdominal surgery has the highest ratio (2-20%) as recently reported (14, 15). In this regard, a promising novel infection-prevention strategy may be the administration of probiotics, which are live microbial preparations that may confer a positive benefit to the host when taken in sufficient amounts. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs suggests that probiotics/synbiotics in adult patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery reduce the risk of SSIs compared to placebo or standard of care (14). However, the currently available evidence was found to be of low to very low quality, mainly due to risk of bias and imprecision; thus, a large, methodologically sound RCT is needed to corroborate the safety and efficacy of their use in surgical patients.

The rational for probiotic use in preventing infections depends on the characteristics of microbiota (16). However, it has to be underlined that the efficacy of probiotic products is both strain-specific and disease-specific. Important factors involved in choosing the appropriate probiotic include matching the strain(s) with the targeted disease or condition, type of formulation, dose used and the source, including manufacturing quality control and shelf-life (17). Therefore, choosing an appropriate probiotic is multi-factored, based on the mode and type of disease indication and the specific efficacy of probiotic strain(s), as well as product quality, formulation, and conservation. For example, it has been very recently demonstrated that two probiotic mixtures obtained by combining taxonomically similar species produced with different manufacturing methods exert divergent effects in mouse models of colitis (18).

Anyway, we know that gut microbiota is associated with the pathogenesis of many diseases and the emerging new therapeutic targets in gut microbiota represent an intriguing challenge (19, 20).

The current survey demonstrated that Abincol® was able to significantly and progressively reduce the most common digestive complaints occurring in patients after abdominal surgery. In particular, Abincol® did diminish impressively abdominal pain and bloating that are bothersome symptoms and affects the quality of life. The improvement of stool form in many patients could be considered the indirect proof of the mechanism of action of Abincol® as it modified the intestinal microbiota inducing a physiological digestive function.

In addition, Abincol® was safe and well tolerated.

All these issues suggest that this probiotic mixture may be useful in the management of patients undergoing abdominal surgery.

Of course, the present survey cannot be considered a formal investigative study. Consequently, further studies should be conducted by a rigorous methodology, such as designed according to randomized-controlled criteria. Another relevant issue is the need of investigating the microbiota before and after probiotics supplementation.

On the other hand, the strength of this survey is the huge number of enrolled patients and the real-world setting. The outcomes could therefore mirror the facts observable in clinical practice. In particular, the sample consisted of patients undergoing elective surgery.

Finally, it has to be noted that the probiotics effects are strain-dependent and outcomes cannot be generalized for all probiotic species.

In conclusion, the current survey suggests that Abincol® may be considered an effective and safe therapeutic option in the management of patients undergoing digestive surgery.

The current article was supported by Aurora Biofarma, Italy

References

- 1.Stavrou G, Kotzampassi Gut microbiome, surgical complications and probiotics. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30:45–53. doi: 10.20524/aog.2016.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alverdy J, Holbrook C, Rocha F. Gut-derived sepsis occurs when the right pathogen with the right virulence genes meets the right host: evidence for in vivo virulence expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ann Surg. 2000;232:480–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasid O, Cavaillon JM. Recent developments in severe sepsis research: from bench to bedside and back. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:293–314. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna S, Tosh PK. “A clinician’s primer on the role of the microbiome in human health and disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francino MP. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:1543. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundell L. Use of probiotics in abdominal surgery. Dig Dis. 2011;29:570–3. doi: 10.1159/000332984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter PD, Stanton C, Ross RP, Hill C. The impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiota as revealed by high throughput DNA sequencing. Discov Med. 2012;13:193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macfarlane S. Antibiotic treatments and microbes in the gut. Environ Microbiol. 2014;16:919–24. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna S, Tosh PK. “A clinician’s primer on the role of the microbiome in human health and disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linares DM, Ross P, Stanton C. Beneficial microbes: The pharmacy in the gut. Bioengineered. 2016;7:11–20. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2015.1126015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann R, Leonard D, Delzenne N, Kartheuser A, Cani PD. Novel insight into the role of microbiota in colorectal surgery. Gut. 2017;66:738–749. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Praagh JB, de Goffau MC, Bakker IS, Harmsen HJ, Olinga P, Havenga K. Intestinal microbiota and anastomotic leakage of stapled colorectal anastomoses: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2259–65. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4508-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lederer AK, Pisarski P, Kousoulas L, Fichtner-Feigl S, Hess C, Huber R. Postoperative changes of the microbiome: are surgical complications related to the gut flora? A systematic rewie. BMC Surg. 2017;17:125. doi: 10.1186/s12893-017-0325-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoe DS, Anderson DJ, Berenholtz SM. A compendium of strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 updates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:967e977. doi: 10.1086/677216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lytvyn L, Quach K, Banfield L, Johnston BC, Mertz D. Probiotics and synbiotics for the prevention of postoperative infection following abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:130–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allali I, Arnold JW, Roach J, Cadenas MB, Butz N, Hassan HM, et al. A comparison of sequencing platforms and bioinformatics pipelines for compositional analysis of the gut microbiome. BMC Microbiology. 2017;17:194. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sniffen JC, McFarland LV, Evans CT, Goldstein EJC. Choosing an appropriate product for your patient: an evidence-based practical guide. PlosOne. 2018;13(12):e0209205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biagioli M, Capobianco D, Carino A, Marchianò S, Fiorucci C, Ricci P, et al. Divergent effectiveness of multispecies probiotic preparations on intestinal microbiota structure depends on metabolic properties. Nutrients. 2019;11:325. doi: 10.3390/nu11020325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, Fan X, Ying J, Chen S. Emerging trends and research foci in gastrointestinal microbiome. J Transl Med. 2019;17:67. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1810-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez-Mercado AI, Navarro-Oliveros M, Robles-Sanchez C, Plaza-Diaz J, Saez-Lara MJ, Munoz-Quezada S, et al. Microbial population changes and their relationship with human health and disease. Microorganisms. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]