Abstract

Bowel preparation (BP) for colonoscopy induces significantly changes in gut microbiota and elicit intestinal symptoms. Impaired microbiota causes an intestinal dysbiosis. Consequently, probiotics may counterbalance the disturbed microbiota after BP. The current survey evaluated the efficacy and safety of Abincol®,an oral nutraceuticalcontaining a probiotic mixture with Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 (1 billion of living cells), Lactobacillus lactis subspecies cremoris LLC02 (800 millions of living cells), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii LDD01 (200 millions of living cells), in 2,979 outpatients (1,579 males and 1,400 females, mean age 56 years) undergoing BP. Patients took 1 stick/daily for 4 weeks after colonoscopy. Abincol® significantly diminished the presence and the severity of intestinal symptoms and improved stool form. In conclusion, the current survey suggests that Abincol® may be considered an effective and safe therapeutic option in the management of patients undergoing BP. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: bowel preparation, gut microbiota, colonoscopy, probiotics, survey

Introduction

The human intestinal tract contains a large number of diverse microbes, some of which are associated with the faeces, while others are associated with the gut mucosa. Most of these microbes are bacteria and constitute a unique and dense ecosystem named microbiota (1). Many studies investigated human gut microbiota, including the Human Microbiome Project in the United States, to define its physiological and pathological role (2).

It is well known that antibiotics may significantly affect the intestinal microbiota (3). Bowel preparation (BP) may also modify critically microbiota (4). BP consists of large doses of laxatives to evacuate most if not all of the stool from the colon. Typically, such a preparation is taken by the patient overnight before the procedure, resulting in 10–20 bowel movements, most of which are diarrheal stools. Therefore, BP significantly affect the colonic ecosystem. In particular, polyethylene glycol-type BP causes loss of superficial mucus in 96% of patients: it contributes consequently to profound alteration of microbiota (5). In addition, BP effects vary in health and in disease as it has been reported that BP affects various microbiota-related diversity metrics in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and non-IBD samples and the mucosal and luminal compartments, differently (4). Overweight also influences microbiota changes after BP (6).

The relevance of these concepts relies on the huge number of colonoscopies performed worldwide, e.g. just 14 millions/year in the United States (7). In addition, colonoscopy induces also symptoms persistence for some days; symptoms can be also so severe as to cause the loss of working days (8). These symptoms mainly depend on BP-induced microbiota disturbance (9). Notably, microbiota changes may persist until one month after colonoscopy (10, 11). Therefore, there is the need to counterbalance microbiota alteration in a short time. In this regard, probiotics may offer a potential therapeutic option to restore the altered gut microbiota. Two recent studies provided evidence that probiotic may significantly improve both symptoms and gut microbiota after BP (12, 13).

Abincol® is an oral nutraceuticalcontaining a probiotic mixture with Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 (1 billion of living cells), Lactobacillus lactis subspecies cremoris LLC02 (800 millions of living cells), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii LDD01 (200 millions of living cells) and it has been recently placed on the market.

On the basis of this background, an Italian survey explored the pragmatic approach of a group of gastroenterologists in the management of intestinal dysbiosis after BP in clinical practice. Therefore, the aim of the current survey was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Abincol® in outpatients after colonoscopy.

Materials and Methods

The current survey was conducted in 83 Italian Gastroenterology centers, distributed in the whole Italy, so assuring a wide and complete national coverage, during the fall-winter 2018-2019. Gastroenterologists were asked to recruit all consecutive outpatients undergoing BP for colonoscopy.

Patients were consecutively recruited during the specialist visit. The inclusion criteria were: to have the indication for colonoscopy, such as presence of intestinal complaints, both genders, and adulthood. Exclusion criteria were to have comorbidities and concomitant medications able to interfere the evaluation of outcomes.

All patients signed an informed consent. All the procedures were conducted in a real-world setting.

The treatment course lasted 4 weeks. The oral nutraceutical Abincol® (Aurora Biofarma, Milan, Italy) was taken following the specific indications, such as one stick/daily. Patients were visited at baseline (T0), and after 4 weeks (T1).

Clinical examination was performed in all patients at T0, and T1. The following symptoms were investigated: abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, flatulence, and borborygmic. They were evaluated before BP and at T1.

These symptoms were assessed as present/absent and were scored using a four-point scale (0=absent, 1= mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe), but for abdominal pain the scale was 5-point (4=very severe).

A physical examination of stool was performed using the Bristol stool form scale (16).

Safety was measured by reporting the occurrence of adverse events.

All clinical data were inserted in an internet-platform that guaranteed the patients’ anonymity and the findings’ recording accuracy.

The paired T-test was used. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. Data are expressed as medians and 1th and 3rd quartiles. The analysis was performed using STATA, College Station, Texas, USA.

Results

Globally, 2,979 outpatients (1,579 males and 1,400 females, mean age 56 years) were visited and completed the treatment course.

The frequency of symptoms (abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, flatulence, and borborygmi) at baseline (T0) and at T1 is reported in Table 1 and 2. In particular, abdominal pain and abdominal bloating were the most common symptoms at baseline. The frequency of both significantly diminished after the treatment course.

Table 1.

Frequency of patients for each symptom at baseline (T0). M=males; F=females, Mean age in years

| N=2,979 | T0 | |||

| n | % | M/F | Mean age | |

| Abdominal pain | 2387 | 80.1% | 1256/1131 | 55 |

| Abdominal bloating | 2102 | 70.6% | 1090/1012 | 56 |

| Flatulence | 1936 | 65.0% | 1037/899 | 56 |

| Borborygmi | 1690 | 56.7% | 872/818 | 56 |

Table 2.

Comparison of proportion of patients with symptoms at baseline (T0) and at T1

| T0 | T1 | ||||

| n | n | % | Diff % | p | |

| Abdominal pain | 2387 | 1124 | 47.1% | -52.9% | <0.001 |

| Abdominal bloating | 2102 | 1039 | 49.4% | -50.6% | <0.001 |

| Flatulence | 1936 | 948 | 49.0% | -51.0% | <0.001 |

| Borborygmi | 1690 | 677 | 40.1% | -59.9% | <0.001 |

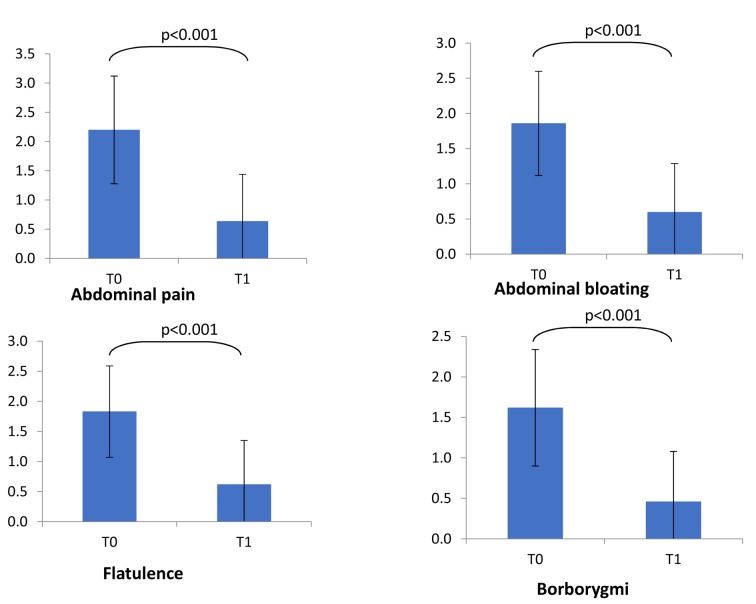

Consistently, the severity of the most relevant symptoms did significantly diminish after the treatment (Figure 1). In particular, abdominal pain and bloating significantly diminished at T1 (p<0.001 respectively for both symptoms).

Figure 1.

Symptoms severity at baseline (T0) and at T1. Symptoms’ score scale was 0-3 for all symptoms but abdominal pain (0-4). Comparisons were made by paired Wilcoxon test. *= p<0.001

In addition, stool form significantly improved as a normal form (type 3 and 4) was detectable in 36.3% at baseline, and in 53.5% at T1 (p<0.001 as linear trend).

The treatment was well tolerated by all patients and no clinically relevant adverse event was reported.

Discussion

Drago and colleagues reported relevant and persistent changes in the intestinal bacteria composition after colonic lavage (10). Actually, the relative abundance among the different bacterial phyla had reduced after the BP, in particular, there was a significant increase in Proteobacteria abundance and a decrease in Firmicutes abundance. This intestinal dysbiosis has been linked to diarrhea, and more interestingly, it has been reported an association between the increase in Proteobacteria and the onset of moderate to severe diarrhea in children from low-income countries (14). An increased frequency of Enterobacteriaceae has been observed immediately after BP (10). It has to be noted that Enterobacteriaceae include a number of nosocomial pathogens with considerable antibiotic resistance, which may proliferate and act as pathogens when not counteracted by the physiological gut microbiota, but also act as a clinically relevant antibiotic-resistance reservoir in the intestinal environment (15). Moreover, Enterobacteriaceae were markedly changed even after one month (10). These microbiota changes are associated with BP-dependent clinical feature. Hence, there is the need to improve the impaired gut microbiota after BP: in this regard, probiotics could be an attractive therapeutic strategy.

The current survey demonstrated that a 4-week course of Abincol® was able to significantly improve digestive symptoms and stool form. These outcomes are consistent with a previous randomized and placebo-controlled study showing that a single capsule of a probiotic containing 2.5 x 1010 CFUs of L. acidophilus NCFM and B. lactis Bi-07 taken daily starting on the night after colonoscopy resulted in an earlier resolution of abdominal pain from 2.78 to 1.99 days (12). Nevertheless, a sub-analysis of that study revealed that there was no significant difference between groups in post-procedural discomfort, bloating nor time to return of normal bowel function (13). However, a subgroup analysis of the patients with preexisting symptoms showed a reduction in incidence of bloating with the use of probiotics. This subset of patients is consistent with our population as presented symptoms before BP.

Therefore, the current survey demonstrated that an oral probiotic mixture with Lactobacillus plantarum LP01 (1 billion of living cells), Lactobacillus lactis subspecies cremoris LLC02 (800 millions of living cells), and Lactobacillus delbrueckii LDD01 (200 millions of living cells) administered for 4 weeks after colonoscopy was able to significantly reduce intestinal symptoms. The significantly improvement of stool form in many patients could be considered the indirect proof of the mechanism of action of Abincol® as it modified the intestinal microbiota inducing a physiological digestive function.

In addition, Abincol® was safe and well tolerated.

It is conceivable that the present survey cannot be considered a formal investigative study. Consequently, further studies should be conducted by a rigorous methodology, such as designed according to randomized-controlled criteria.

On the other hand, the strength of this survey is the huge number of enrolled patients and the real-world setting. The outcomes could therefore mirror the facts observable in clinical practice.

In conclusion, the current survey suggests that Abincol® may be considered an effective and safe therapeutic option in the management of patients undergoing BP.

The current article was supported by Aurora Biofarma, Italy

References

- 1.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–10. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shobar RM, Velineni S, Keshavarzian A, Swanson G, DeMeo MT, Melson JE, et al. The effects of bowel preparation on microbiota-related metrics differ in health and inflammatory bowel disease and for the mucosal and luminal microbiota compartments. Clin Translat Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e143. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rappe MS, Giovannoni SJ. The uncultured microbial majority. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:369–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen HM, Chen CC, Chen CC, Wang SC, Wang CL, Huang CH, et al. Gut microbiome changes in overweight male adults following bowel preparation. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(Suppl 10):904. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5285-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeff LC, Richards TB, Shapiro JA. How many endoscopies are performed for colorectal cancer screening? Results from CDCs survey of endoscopic capacity. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1670–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ko C, Riffle S, Shapiro J, et al. Incidence of minor complications and time lost from normal activities after screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:648–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai M, Zhang T, Li Q, Cui B, Xiang L, Ding X, et al. The bowel preparation for magnetic resonance enterography in patients with Chron’s disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:1. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3101-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drago L, Toscano M, De Grandi R, Casini V, Pace F. Persisting changes of intestinal microbiota after bowel lavage and colonoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:532–7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagata N, Tohya M, Fukuda S, Suda W, Nishijima S, Takeuchi F, et al. Effects of bowel preparation on the human gut microbiome and metabolome. Scientific reports. 2019;9:4042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40182-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Souza B, Slack T, Wong SW, Lam F, Muhlmann M, Koestenbauer J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of probiotics after colonoscopy. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:E65–E69. doi: 10.1111/ans.13225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullaney TG, Lam D, Kluger R, D’Souza B. Randomized controlled trial of probiotic use for post-colonoscopy symptoms. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:234–8. doi: 10.1111/ans.14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pop M, Walker AW, Paulson J, Lindsay B, Antonio M, Hossain MA, et al. Diarrhea in young children from low-income countries leads to large-scale alterations in intestinal microbiota composition. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace NR, Olsen GJ, Woese CR. Ribosomal RNA phylogeny and the primary lines of evolutionary descent. Cell. 1986;45:325–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]