Abstract

Background and Aim:

Inappropriate visits to the Emergency Department (ED) by frequent users (FU) are a common phenomenon because this service is perceived as a rapid and concrete answer to any health and social issue not necessarily related to urgent matters. Could Case Management (CM) programs be a suitable solution to address the problem? The purpose is to examine how CM programs are implemented to reduce the number of FU visits to the ED.

Methods:

PubMed, CINAHL and EMBASE were consulted up to December 2018. This review follows PRISMA guidelines for systematic review, as first outcomes were considered the impact of CM interventions on ED utilization, costs and composition of teams.

Results:

Fourteen studies were included and they showed patients with common characteristics but the FU definition wasn’t the same. Twelve studies provided a reduction of ED utilization and seven studies a cost reduction. The main tool used is the individual care plan with telephone contact, supportive group therapy, facilitated contacts with healthcare providers and informatics system for immediate identification. The CM team composition is heterogeneous, even if nurses are considered the most used professional figures.

Conclusions:

In contrast with a standardized method, a customized approach of CM program helps frequent users in finding an appropriate answer to their needs, thus decreasing inappropriate visits to the ED. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: case management, emergency service, patient care planning, vulnerable populations, frequent users

Introduction

Emergency Department (ED) is facing the issues of overcrowding and lengthy waiting times due to a disproportionately elevated number of visits (1, 2). The ED is perceived as a rapid and concrete answer to any health and social issue not necessarily related to urgent matters. Moreover local services are often bypassed because they are perceived as little efficient (3). The visits to the ED for non-urgent matters range between 9% and 54.1% in the USA, between 25.5% and 60% in Canada, and between 19.6% and 40.9% in Europe (4).

Many studies have underlined the presence of frequent users (FU) who often aren’t in need of urgent aid and could receive better cares in a different setting compared to that of the ED (1, 3, 5). According to a systematic review carried out in the USA, FUs are identified as patients who visit the ED at least 4 times a year (or 3 times a month) (1). They represent between 4.5% and 8% of the patients who use the provided service and between 21% and 28% of all the ED medical activity (1). These patients are often defined “vulnerable” patients (6) because they have a low social and economic status (7) and they have difficulties in taking care of themselves independently, especially when complications and exacerbations of their chronic condition arise (8, 9). As a result, non-urgent visits to the ED increase and many healthcare resources are used (5, 10).

To tackle this issue, many healthcare systems are trying to implement new organizational set-ups both in hospitals and territorially (11), among those the Case Management (CM) program (12, 13) which is a collaborative approach used to assess, plan, facilitate and coordinate healthcare related matters (14). It aims at meeting patients’ and their families’ health needs through communication and available resources, thus, improving individual and healthcare system outcomes (15, 16). The CM can be implemented through programs that include various social activities as well as provide clinical assistance such as the individual care plan (ICP) (17), support group therapy (18), assistance in obtaining stable housing (19), linkage to medical care providers (20, 21) and telephone contact (20, 22).

Aim

The aim of the study is to examine if and how the CM programs are implemented to reduce the number of FU visits to the ED.

Methods

Design

A systematic review was carried out. All types of articles (observational and experimental) in English were considered potentially suitable. PubMed, CINAHL and EMBASE were consulted up to December 2018 and the studies published in the last 10 years were taken into account because this review aimed to explore the current trends. This review was undertaken in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (23).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included the studies that describe CM intervention, considering FU adult patients who visit the ED for any kind of clinical or social purpose or who are in need of assistance. Limitations concerning sex, ethnicity, co-morbidity or other characteristics were not applied. Studies indicating CM programs which were developed and implemented both by a single professional figure (doctor, nurse, social worker) and by a multidisciplinary team were taken into account. The studies indicating the composition of the CM teams and the patients’ medical-nursing pathway were analyzed. Limitations regarding the duration of the program and the implementation modalities were not imposed. As first outcomes of interest, were considered the impact of CM interventions on ED utilization, costs and team composition.

Search strategy

The key terms used in the literature search included: “frequent user*”, “frequent attender*”, “emergency department*”, “Hospital Emergency Service*”, “Emergency Unit*”, “Accident and Emergency Department”, “Emergency Room*”, “case management”, “case manager”, “patient care management”.

Search outcomes

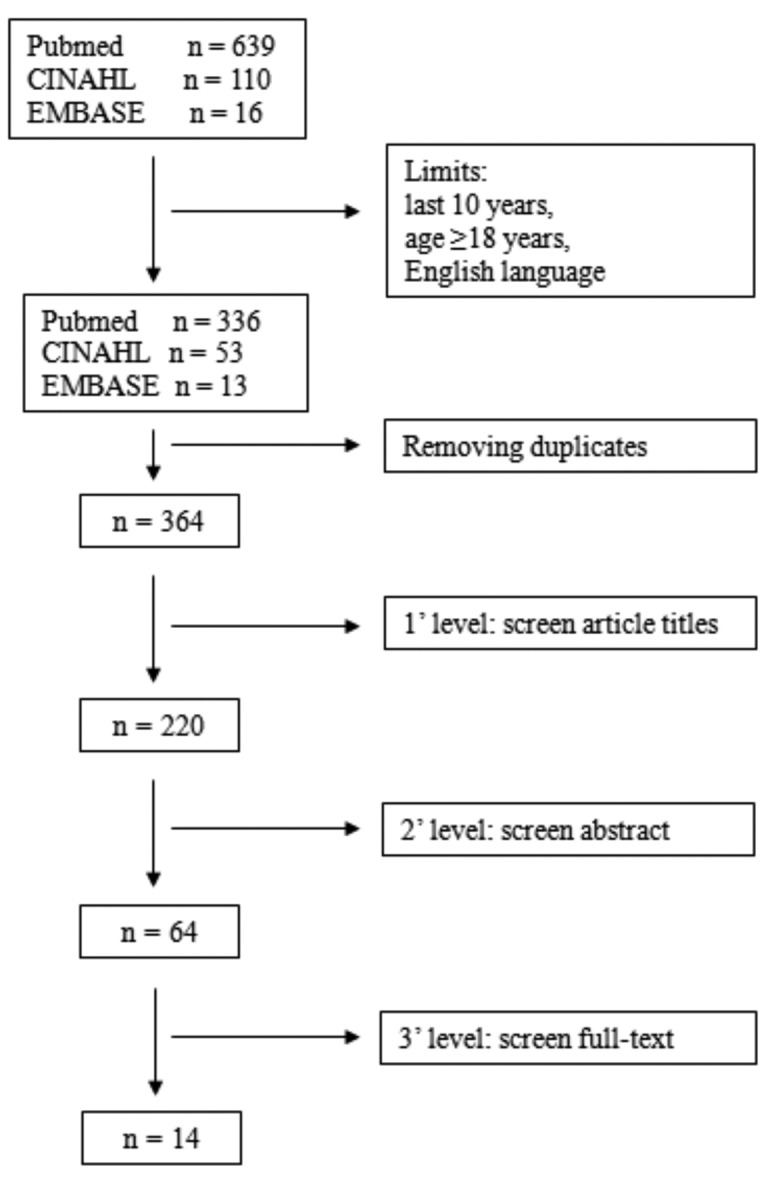

Considering the large number of publications resulting from the bibliography search, an evaluation process based on three levels was used. They were: appropriateness of the titles, evaluation of the abstracts and of the full-texts.

Each evaluation level was analyzed separately by two authors who examined all the bibliographic references judging whether they were potentially suitable. The results of each level were compared and a third author solved any disagreement. Figure 1 shows the search strategy flow diagram used to obtain the results.

Figure 1.

Search and selection flow diagram

After having selected the articles that would be included in this research, two of the authors used a standard Excel module to extract the data. Any disagreement which arose during this stage was solved by means of a third author.

Fourteen studies corresponding to the research criteria were found: 7 randomized controlled trials, 4 prospective observational and 3 retrospective observational studies.

Quality appraisal

The quality of the approved studies was assessed by using the CASP checklist (24, 25). This tool is made up of a list of questions. Each question is awarded from 1 to 11 points. The quality of each article was assessed by two authors independently. Any disagreement was dealt effectively through the aid of a third author. The marks of the selected articles were recorded in the last column of Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of selected studies (n=14)

| Author (Year) | Journal | Country | Tipe of Study | Number of Edaccess | Frequent Users Characteristics | Follow Up | Case Management Team | Interventions | Main Findings | Casp Quality Score |

| Bodenmann et al. (2017) | Gen Intern Med | Switzerland | RCT | ≥ 5 in a year | 125 patients, male 57.2 %, mean age 48.5 years. Chronic condition, medical co-morbidity or psychiatric illness. |

1 year | 4 nurse practitioners and 1 chief resident. | ICP, providing intervention in an ambulatory care, hospital or home setting. Telephone contact with case management team. | Reduction of ED access: -19% (P=.048). | 10\11 |

| Chiang et al. (2014) | Hong Kong J Emerg Med | Cina | Prospective observational | ≥3 visits in 3 days | 14 patients, male 78.6%, mean age 44.3 years. Cases were divided into the pain management or chronic disease group according to their chief complaint. |

6 months | Physicians, primary care physicians, psychiatrists, social workers and pharmacologists. | ICP dynamically whith internal ED information system. | Reduction of ED access: -58.5% (P=.004). | 9\11 |

| Crane et al. (2012) | Am Board Fam Mec | USA | Prospective observational | ≥ 6 in a year | 36 patients, male 55.6%, mean age 34 years. Chronic pain 75%, substance abuse 47%, COPD/asthma 17%, homeless 19%. |

1 year | 1 family physician, 1 nurse case manager and 2 behavioral health providers. | ICP, group appointment, direct telephone access and sessions with the care manager. | Reduction of ED access per month: -35% (P<.001). Reduction of costs (ED and inpatient) per patient per month: -80% (P<.001). |

10\11 |

| Edgren et al. (2016) | EurJ Emerg Med | Sweden | RCT | ≥ 3 in 6 month | 4273 patients, male 43.6%, mean age 62.5 years. Generalized or unspecific pain diagnosis, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation. |

2 years | Nurse case manager. | Telephone-based intervention, facilitated contacts with healthcare providers, coached patients’ disease selfmanagement and supported interactions with social services. | Reduction of ED access: -14% (P=.007). Reduction of costs per patient per year: -16% (P=.004). |

10\11 |

| Grover et al. (2016) | Emerg Med | USA | Prospective observational | 12 in a year 6 in 3 months 4 in a month |

533 patients, male 32.2%, mean age 42.6 years. Chronic conditions 71.4%, chemical dependency evaluation/drug abuse treatment 30.7%, pain management 25.6%. |

From 1 month to 8 years | ED nurse and nurse case manager. | ICP based on chronic medical problems and reasons for repeat ED usage. Patients were “flagged” in the ED information system for immediately identify. | Reduction of ED access per month: -56.5%(P<.001). | 10\11 |

| Groveretal. (2018) | West J Emerg Med | USA | Retrospective observational | ≥10 in a year 6 in 6 months 4 in a month |

158 patients, male 44.9%, mean age 42.4 years. Substance use 63.5%, pain management 60.4%. | 19 months | Registered nurse, emergency physicians, social workers, ED nurses, chemical dependency providers, behavioral health registered nurse, case managers and representatives from local insurance providers. | ICP. | Reduction of ED access: -49% (P<.05). Reduction of costs: -41% (P<.05). | 11\11 |

| Moschetti et al. (2018) | Plos One | Switzerland | RCT | ≥ 5 in a year | 125 patients, male 56%, mean age 46 years. Social difficulty 74,4%, somatic problem 72%, mental health problem 49,6%, risky behavior 30,4%, not having a primary care physician 16%. |

1 year | 4 nurses and 1 general practitioner. | ICP, providing intervention in an ambulatory care, hospital or home setting and telephone contact with case management team. | No reduction of ED costs: -19% (P=.29). | 10\11 |

| Peddie et al. (2011) | N Z Med J | Australia | Prospective observational | ≥ 10 in a year | 87 patients, male 40%, mean age 35 years. Desease: medical 45%, psychiatric 29%, substance/alcohol abuse 26%. |

4 years | Nurse, ED consultant, medical specialists, psychiatric services and social workers. | ICP. | The interventions and the control are infussicient to prove the utility. | 10\11 |

| Reinius et al. (2013) | EurJ Emerg Med | Sweden | RCT | ≥ 3 in 6 months | 211 patients, male 40.3% mean age 62.6 years. Hypertension 26%, ischaemic heart disease 19%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorders 9%, heart failure 15%, anxiety disorders 9%, generalized or unspecified pain 41%, atrial fibrillation 18%. |

1 year | Case management nurses. | Telephone calls: motivational conversations (13%), support for patient self-care (17%), education on basic medical issues (18%), providing contact with counsellors (3%) or social services (5%), providing contacts with primary care physicians (14%) primary care nurses (5%) and help to establish contacts or appointments at other healthcare facilities (15%). | Reduction of ED access: - 20% (P not avaiable). Reduction of costs: -45% (P=.004). |

11\11 |

| Sadowski et al. (2009) | Jama | USA | RCT | Not define | 201 patients, male 74%, mean age 47 years. Homeless adults with chronic medical illnesses median duration of homelessness of 30 months. |

18 months | Social worker whith post-graduate specialization. | Provision of transitional housing and subsequent placement in stable housing. | Reduction of ED access: -24% (P=,03). | 10\11 |

| Shah et al. (2011) | Med Care | USA | Retrospective observational | ≥ 6 in a year | 98 patients, male 59.2%, mean age 46.6 years. Deseases of pancreas 15.56%, asthma 6.67%, Charlson comorbidity index mean 1.4. |

2 years | Not identified the professional profiles. | ICP, schedule appointments, arranging for support services, discharge plans and communication with providers. | Reduction of ED access: -32% (P<.001). Reduction of costs per patient per year: -26% (P<.001). | 9\11 |

| Shumwayetal.(2008) | Am J Emerg Med | USA | RCT | ≥5 inayear | 167 patients, male 75%, mean age 43 years. Mental disorders (22%), injury (16%), diseases of the skin (8%), endocrine disorders (5%), digestive system disorders (5%), respiratory illnesses (5%). |

2 years | Nurse practitioner, a primary care physician and a psychiatrist. | ICP, assessment, crisis intervention, individual and group supportive therapy, linkage to medical care providers, referral to services when needed, assistance in obtaining stable housing and income entitlements. | Reduction of ED access: (P=.01) no single number or percentage avaiable. Reduction of costs per patient: (P=,01) no single number or percentage avaiable. | 11\11 |

| Stergiopoulos et al. (2017) | Plos One | Canada | RCT | ≥ 5 in a year | 83 patients, male 47%, mean age 42.7 years. Anxiety disorders 61.5%, mood disorders 63.9%, psychotic disorders 25.6%, substance misuse disorder 53%, personality disorder 25%, |

1 year | Not identified the professional profiles. | Home visits, crisis intervention, supportive therapy, practical needs assistance and care coordination, aiming to integrate hospital, community and social care and improve continuity of care. | No reduction of ED access -14% (P=.31). | 10\11 |

| Stokes-Buzzelli et al. (2010) | West J Emerg Med | USA | Retrospective observational | Not define | 45 patients, male 75%, mean age 48 years. Substance abuse problems 89%, mental illness 72%, various medical co-morbidity as asthma/COPD 44%, hypertension 64%. |

2 years | ED attending physician, ED medical socia worker, ED mental health social worker, ED psychologist, ED resident, ED clinical nurse specialists and a student healthcare volunteer. | ICP, use of health information technologies and electronic medical record systems for immediately identify. | Reduction of ED access: -25% (P=.046). Reduction of costs per patient per 2 years: -25% (P=.049). | 9\11 |

Legend: COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ED Emergency Department, ICP individual care plan, RCT randomized controlled trial

Results

The details extracted from the chosen studies were synthesized in Table 1.

The selected studies analyzed 6031 participants undergone CM interventions, the majority were males with mean age 46 years. The study target population was heterogeneous and mainly consisted of people suffering from chronic conditions and socioeconomic issues, such as, for example, alcoholism (26), mental illnesses (26-31), illegal substance use (28, 30-34), homeless status (32, 35), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (30, 32) and cardiovascular diseases (29, 30). Four studies (29, 33, 34, 36) showed that pain is a frequent reason for patients’ ED visits.

Eleven studies gave a precise definition of the amount of annual and monthly visits to the ED that identified the patient as a FU. In the analyzed articles FU are people who visit the ED 5 (26, 27, 31) or 6 (21, 32) or 10 (28, 34) or 12 (33) times or more in a year, 3 (29, 34, 37) times or more in six months, 6 (33) times or more in three months, 4 times or more in a month (33, 34) and 3 (36) times or more in 3 days. These numbers remain unvaried but may be combined in different ways according to the study they are recorded in (33, 34). Two studies (30, 35) did not report a specific metric for frequency of use.

Concerning CM interventions, eight studies (21, 26-28, 30, 33, 34, 36) created ICPs. Four studies (27, 29, 32, 37) recognized the importance of telephoning patients directly, thus, simplifying the course of their treatment. Among these treatments, a study (29) showed that motivational support was given too. Four studies (21, 26, 29, 37) facilitated contacts with healthcare providers and two studies (26, 32) organized group meetings with patients who needed the same kind of treatment. Two studies (30, 33) showed how patients enrolled in CM programs were immediately identified by the computerized system guaranteeing them appropriate treatments. Two studies (27, 31) included home visits and ambulatory care. Two studies (26, 35) guaranteed that homeless people receive an apartment through social services. Only in a study (26) patients were enrolled in treatment pathways defined by other departments.

Analyzing the selected articles, differences among CM team compositions stood out. In seven studies (26-28, 30, 32, 34, 36) an actual multidisciplinary team was recognized. It was made up of various professional figures with specific characteristics who collaborated to guarantee that local services took responsibility for ED patients. Three studies (29, 33, 37) deemed professional nurses specialized in CM to be the main CM protagonist. In an article (35) social workers with a post-graduate specialization were considered central in CM, whereas two articles (21, 31) didn’t clearly define what kind of professional figure carried out the task but only identified him/her with the Case Manager.

Ten papers showed as main finding the decrease in visits to the ED (from 14% to 58.5%) and in only three studies (28, 29, 31) the results were insufficient to prove this utility. Furthermore, seven studies (26, 29-33, 37) reported a reduction in health costs (from 16% to 80%).

The duration of the most significant follow-up was 2 years (21, 26, 30, 37) followed by 1 year (27, 29, 31, 32). Fewer studies showed 6-month (36), 18-month (35), 19-month (34) and 4-year (28) follow-up periods. Only one study showed a 1-month to 8-year follow-up (33).

Discussion

Despite being a heterogeneous group of patients, the most significant categories of those enrolled are: addiction to illegal substances, mental illness and homeless. These data correspond to the study of Ko et al. (38) and to the systematic review of LaCalle et al. (1).

Concerning the regularity of visits to the ED which identify the FU, findings show that patients who visit the ED ≥5 times a year and ≥3 times in 6 months are the most represented categories; in fact, a definition of a FU varies in the literature (30). It is interesting to note that no study considered patients who visit the ED a minimum of 4 times a year as FUs, moreover, only one study enrolled patients who visited the ED at least 3 times a month (criteria found in the literature regarding the definition of FU patients) (1). Not all the chosen studies used specific FU definitions.

The ICP is the most used tool in answer to the patients’ needs. It is based upon the needs that brought each patient to turn to the ED. The ICP has been carried out in different ways: structured telephone calls are deemed of great importance. The reason is simple: telephone calls enable the program to reach people at greater distances; hence, it is possible to guarantee a constant presence even when a physical meeting cannot take place. This reduces the risk of losing patients enrolled in the program to minimum levels (38).

Placing direct telephone calls also enables an immediate access to the National Health System in case of emergency. This could lead to considering direct telephone calls the gold standard of implementation; however, the evidence is still insufficient to judge them as such.

It is relevant to note how an early warning system and a clear communication method were used in two studies among health care suppliers to identify the FU.

Nine studies showed the significance of the roles of nurses working both individually and in a team. The reason could be that they take a holistic responsibility of their patient due to their nature and training.

The study of Shah et al. (21) doesn’t specify who the professional case manager is, however it can be assumed it is a nurse due to the tasks he/she carries out. The study of Sadowski et al. (35) underlines the role of social workers defining them a point of reference for patients, since their job is to analyze and deal with homeless patients’ needs. Considering this perspective, it is interesting to observe that the outcome of this analysis isn’t just the decrease in the number of ED visits but also of the hospital use. This could be explained with a drop in admissions for social reasons, such as the inappropriate admission of a patient as a result of no alternatives as to where he/she should turn to instead.

The study of Moschetti et al. (39) analyzes the costs of the CM program implemented by Bodenmann et al. (27) allowing a more in-depth analysis of costs and interventions.

Limits

Comparing the selected studies is difficult to carry out since said studies are little heterogeneous in terms of number of patients, methods used and FU definitions.

Some of the studies referred to healthcare realities are rather different in relation to organizations, structures and roles according to their country of origin. Hence, considering the composition of the CM teams, some professional figures cannot be compared because they exist only in some health care systems. The selected studies varied in the amount of details given to describe CM interventions making it challenging to assess the intervention scale and intensity.

Most of the studies focused only on one ED and didn’t consider whether the patients, both enrolled and not enrolled in CM program, had had further contact with other local EDs.

Conclusion

The review shows that in contrast with a standardized method, a customized CM approach helps FUs in finding an appropriate answer to their needs. The ICP takes patients’ individual needs into consideration more than any other tool programming well-aimed interventions with the objective of satisfying them, and consequently, reducing visits to the ED and, in some cases, healthcare costs. The CM process must make use of hospital and territorial services, continuously integrating the medical and the social dimensions. Since FUs are a complex population for EDs, appropriate actions are needed to reduce their access.

Considering the global aging of population and the increase in chronic pathologies health care systems should implement policies of global care of the patient and of his/her family context. The CM can be a tool which should be applied with different methods. It could be desirable to carry out CM models also in the Italian EDs where there are no published studies.

Conflict of interest:

None to declare

References

- 1.LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent Users of Emergency Departments: The Myths, the Data, and the Policy Implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayaprakash N, O’Sullivan R, Bey T, Ahmed SS, Lotfipour S. Crowding and delivery of healthcare in emergency departments: the European perspective. West J Emerg Med. 2009 Nov;10(4):233–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: A systematic review. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(3):717–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bornaccioni C, Coltella A, Pompi E, Sansoni J. Non-urgent access to care and nurses’ roles in the Emergency Department: a narrative literature review. Prof Inferm. 2014 Jul-Sep;67(3):139–54. doi: 10.7429/pi.2013.673139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenmann P, Velonaki VS, Ruggeri O, et al. Case management for frequent users of the emergency department: study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Jun 17;14:264. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodenmann P, Baggio S, Iglesias K, et al. Characterizing the vulnerability of frequent emergency department users by applying a conceptual framework: A controlled, cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Tiel S, Rood PP, Bertoli-Avella AM, et al. Systematic review of frequent users of emergency departments in non-US hospitals: state of the art. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015 Oct;22(5):306–15. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein LR, Martel ML, Driver BE, Reing M, Cole JB. Emergency Department Frequent Users for Acute Alcohol Intoxication. West J Emerg Med. 2018 Mar;19(2):398–402. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.10.35052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, Noseworthy TW, Clement FM. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 13;10(4):e0123660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuek BJW, Li H, Yap S, et al. Characteristics of Frequent Users of Emergency Medical Services in Singapore. Prehospital Emerg Care. 2018 Aug;1:10. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2018.1484969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carli A, Moretti F, Giovanazzi G, et al. “Should I stay or Should I go”: patient who leave Emergency Department of an Italian Third-Level Teaching Hospital. Acta Biomed 2018 Oct. 8;89(3):430–436. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i3.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Lambert M, Dufour I, Krieg C. Effectiveness of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012353. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, Noseworthy TW, Clement FM. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 13;10(4):e0123660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfieri E, Ferrini AC, Gianfrancesco F, et al. The mapping competences of the nurse Case/Care Manager in the context of Intensive Care. Acta Biomed. 2017 Mar 15;88(1S):69–75. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i1-S.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huntley AL, Thomas R, Mann M, et al. Is case management effective in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital admissions for older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2013;30(3):266–75. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thoma JE, Waite MA. Experiences of nurse case managers within a central discharge planning role of collaboration between physicians, patients and other healthcare professionals: A sociocultural qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2018 Mar;27(5-6):1198–208. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton A, Sarker SJ, Parfitt A, et al. Individual care plans can reduce hospital admission rate for patients who frequently attend the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:654–657. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.085704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(5):603–8. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malte CA, Cox K SA. Providing intensive addiction/housing case management to homeless veterans enrolled in addictions treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31(3):231–41. doi: 10.1037/adb0000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera D, Shah R, Guenther T, et al. Integrated community case management (iCCM) of childhood infection saves lives in hard-to-reach communities in Nicaragua. Rev Panam Salud Publica-Pan Am J Public Heal [Internet] 2017 doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2017.66. [cited 2018 May 8] 41(iCCM):10. Available from: https://scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1020-49892017000100226&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah R, Chen C, O’Rourke S, Lee M, Mohanty SA, Abraham J. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care. 2011 Feb;49(2):166–71. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182028e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kivelitz L, Kriston L, Christalle E, et al. Effectiveness of telephone-based aftercare case management for adult patients with unipolar depression compared to usual care: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015 Dec;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Case Control Study Checklist [Internet] 2018. [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 25.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist [Internet] 2018. [cited 2018 Jun 1]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 26.Shumway M, Boccellari A, O’Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(2):155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodenmann P, Velonaki V-S, Griffin JL, Baggio S, Iglesias K, Moschetti K, et al. Case Management may Reduce Emergency Department Frequent use in a Universal Health Coverage System: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(5):508–15. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3789-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peddie S, Richardson S, Salt L, Ardagh M. Frequent attenders at emergency departments: research regarding the utility of management plans fails to take into account the natural attrition of attendance. N Z Med J [Internet] 2011 Mar [cited 2018 Jun 7];124(1331):61–6. Available from: http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/124-1331/4581/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinius P, Johansson M, Fjellner A, Werr J, Öhlén G, Edgren G. A telephone-based case-management intervention reduces healthcare utilization for frequent emergency department visitors. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013;20(5):327–34. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328358bf5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stokes-Buzzelli S, Peltzer-Jones JM, Martin GB, Ford MM, Weise A. Use of health information technology to manage frequently presenting emergency department patients. West J Emerg Med [Internet] 2010 [cited 2018 Jun 7]; 11(4): 348-53. Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gw5t63j . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, Cohen A, et al. The effect of brief case management on emergency department use of frequent users in mental health: Findings of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017 Aug 3;12(8):e0182157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crane S, Collins L, Hall J, Rochester D, Patch S. Reducing Utilization by Uninsured Frequent Users of the Emergency Department: Combining Case Management and Drop-in Group Medical Appointments. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(2):184–91. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grover CA, Crawford E, Close RJH. The Efficacy of Case Management on Emergency Department Frequent Users: An Eight-Year Observational Study. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(5):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grover CA, Sughair J, Stoopes S, et al. Case Management Reduces Length of Stay, Charges, and Testing in Emergency Department Frequent Users. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(2):238–44. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.9.34710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadowski LS, Buchanan D. Effect of a Housing and Case Management Program on Emergency Department Visits Homeless Adults. Jama. 2009;301(17):1771–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang C, Lee C, Tsai T, Li C, Lee W, Wu K. Dynamic Internet-Mediated Team-Based Case Management of High-Frequency Emergency Department Users. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2014 May 11;21(3):161–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgren G, Anderson J, Dolk A, et al. A case management intervention targeted to reduce healthcare consumption for frequent Emergency Department visitors. Eur J Emerg Med [Internet] 2016 Oct;23(5):344–50. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ko M, Lee Y, Chen C, Chou P, Chu D. Prevalence of and predictors for frequent utilization of emergency department: A population-based study. Med (United States) 2015;94(29):1–9. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moschetti K, Iglesias K, Baggio S, Velonaki V, Hugli O, Burnand B, et al. Health care costs of case management for frequent users of the emergency department: Hospital and insurance perspectives. PLoS One. 2018 Sep 24;13(9):e0199691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]