Abstract

Background and aim:

The study aims at identifying the antecedents and consequences of emotional exhaustion in health professionals and, particularly, examining the process that leads from a hindrance demand, like role ambiguity, to exhaustion and job satisfaction. Emotional exhaustion is a phenomenon that affect health professionals with negative consequence on job satisfaction, and literature has underlined that job demands could be may be a cause of this chronic stress. However, the relationship among job demands, work engagement and exhaustion has produced results not always converging.

Method:

A self-report questionnaire was administered to 66 health professionals.

Results:

The results showed that the effect of role ambiguity on emotional exhaustion was mediated by work engagement and the emotional exhaustion impairs job satisfaction when workers are not committed to their profession.

Conclusions:

Role ambiguity represents a psychosocial risk factor that influence workers’ wellbeing diminishing the level of motivation and this process leads to emotional exhaustion. However, professional commitment appears to be a resource that can protect professionals preventing a decrease in satisfaction. These findings suggest that human resource management should remove hindrance stressors and enhance the mission of Healthcare Professionals in order to increase employees’ work engagement and prevent exhaustion. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: healthcare professionals, role ambiguity, emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction

Burnout is a common phenomenon in healthcare organisations because health professionals are continually exposed to the physical and emotional needs of their patients (1, 2), are involved in complex relationships with patients’ families and have long working hours and are overloaded (3). Burnout is defined as a negative response to chronic stress in the workplace (4, 5), and consists of three symptoms: emotional exhaustion – i.e. the feeling of not being able to give anything to others on an emotional level, depersonalisation – i.e., an excessively detached attitude towards patients and low personal accomplishment – i.e. a negative work-related self-evaluation (6, 7). Burnout has negative repercussions for the efficiency of patient care and for workers’ wellbeing (8, 9): it may lead to negative outcomes such as medical errors, depression and absenteeism (10).

Researchers have shown that organisational factors may be a cause of chronic stress in the workplace, leading to job burnout in healthcare professions. Professional and career issues, workload and time pressure, team climate and leadership (11), lack of job control, role conflict and role ambiguity (3, 12, 13) have been identified as factors which affect burnout risk amongst employees.

In this paper we focused on role ambiguity, i.e. situations when workers’ expectations about a role and the actual tasks required in that role are contradictory or when a worker does not have access to sufficiently clear information about the goals and responsibilities of his or her job (14, 15). This lack of clarity about goals and organisational role can produce incompatibilities in expectations, resulting in increased occupational stress, decreased professional performance and impaired organisational efficiency (8, 12, 16). Chu, Lee and Hsu (17) found that role ambiguity was negatively associated with employees’ performance with negative consequences for the wellbeing of the organisation.

Work Engagement

When we talk about the burnout, we must consider another construct, namely engagement, which is opposite but related to it (7). Kahn (18) introduced the concept of engagement, conceptualising it as the “harnessing of organisation members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances” (p. 694). Thus, engaged employees identify with their work activity and invest effort in it. According to Kahn (18, 19) there is a dynamic, dialectical relationship between the person who puts physical, cognitive, emotional and mental energy into his or her work role and the nature of the work role that allows this person to express him or herself.

Research on burnout has stimulated a new theoretical approach that considers engagement as an independent, distinct concept that is negatively related to burnout (20). Engagement is a positive, persistent state of mind that is related to work and characterised by three dimensions (21): vigour, which allows one to invest energy and effort in one’s work and show mental resilience in the face of difficulties; dedication, which involves being involved in one’s work and perceiving it as exciting and challenging; absorption, which means concentrating fully on one’s work so that one has the feeling that time passes quickly (20). Engagement is closely related to the motivational processes that lead workers to take satisfaction from job tasks whereas burnout is characterised by the opposite: lack of energy and detachment from work activities (22).

Job Demands-Resources Model

The job demands-resources model (20) incorporates both burnout and work engagement, treating them as two different processes that lead to different outcomes, negative (burnout and its consequences) or positive (engagement and its consequences). The job-demands resources model identifies job demands, i.e. those aspects of a job that require sustained physical or mental effort and job resources (personal and work related resources) that allow workers to achieve goals, reduce job demands and costs and stimulate personal growth and development. The model posits both an energetic process, whereby high job demands exhaust employees’ resources and thus deplete their energy (i.e. produce exhaustion) and lead to health problems (health impairment process) and a motivational process whereby job resources foster engagement, with positive effects on wellbeing and work outcomes (23).

As yet, however, the job demands-resources model has not been used to examine the relationship between job demands and work engagement in depth. Research into job demands as a potential predictor of work engagement has produced mixed results (23). Some studies have identified distinct types of job demands (24, 25), which could explain these inconsistencies.

Cavanaugh et al. (25) identified two categories of job demands with different consequences for engagement, which they labelled challenge stressors and hindrance stressors. Challenge demands are stressful requests, such as being asked to assume a high level of responsibility, that can be perceived as opportunities for learning or personal and professional growth that may lead to future gains. Hindrances tend to be perceived as stressful requests that have the potential to impede personal growth, learning and goal achievement. Role conflict and ambiguity and organizational policy are part of this type of demands. Hindrances tend to generate negative emotional states and result in a dysfunctional style of coping, such that investing energy in negative emotions acts as a barrier to workers getting interesting goals and decreases motivation and engagement in work activities (26, 27).

Harter et al. (28) showed that people who do not know what is expected of them are less likely to be emotionally engaged, because they have to invest effort in clarifying the ambiguities of their role, which has consequences for their wellbeing and work satisfaction. Other studies have also underlined that role ambiguity is related to a decrease in affective engagement, which reduces employee wellbeing (24, 29).

Starting from this distinction between job demands and the original definition of engagement (in terms of involvement in role organisation), we hypothesised that in health professionals the relationship between a hindrance demand, namely role ambiguity, and exhaustion is mediated by work engagement, such that hindrance demands have negative consequences for job satisfaction.

Professional Commitment

One personal resource that can influence the motivational process and job satisfaction is professional commitment (30), which has been defined as the extent to which workers feel involved with their profession (31). Research in health organisations has showed that professional commitment is positively related to job performance and low turnover, satisfaction with work activity (32) and organisational commitment (33).

Professional commitment, which is associated with team commitment, can also increase interprofessional collaboration amongst nurses and physicians (34-39). Hence the second objective of this study was to explore how professional commitment moderates the relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction.

Hypotheses

Starting from the distinction between hindrance and challenge job demands, we hypothesised that role ambiguity, a hindrance demand, influences exhaustion through the mediation of job engagement (Hypothesis 1). Specifically, we hypothesised that health professionals who perceived high role ambiguity would be less engaged in work activity and invest energy in dealing with negative feelings activated by stressful demands and hence would perceive themselves to be exhausted and fatigued.

Secondly, in line with the health impairment process postulated in the Job Demands-Resources Model, we hypothesised that emotional exhaustion would reduce job satisfaction (Hypothesis 2).

Our final prediction concerned the moderation of the relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction by professional commitment. We hypothesised that emotional exhaustion reduces job satisfaction only when professional commitment is low (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Data Collection

A self-report questionnaire was hand delivered by researchers to health professionals working at the Cardio-Nephro-Pulmonary Department and Geriatric Rehabilitation Department of a hospital in northern Italy.

Ethical Issue

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the participating hospital.

Participants

Sixty-six questionnaires were returned. Participants were mainly women (70%; three participants did not report their gender) with a mean age of 41.82 years (SD = 9.88; 5 participants did not report their age). Forty (62.5%) participants were nurses or nurse managers, twelve (18.5%) were physicians, eight (12.3%) were healthcare operators and five (7.7%) had other roles.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of several scales, relevant to the theoretical concepts about which we had hypothesised, that have been validated in Italian and international contexts.

Role ambiguity was measured with the scale developed by Rizzo et al. (40). The scale consists of four items referring to the clarity of respondents’ expectations about their role (e.g. ‘In my job I know exactly what is expected of me’). The reliability of the scale was satisfactory (α = .75).

Emotional exhaustion was measured by MBI – General Survey (41). The scale consists of five items referring to the feeling of being emotionally depleted (e.g. ‘I feel run down and drained of physical or emotional energy’). All items were scored on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 = ‘never’ to 6 = ‘always/every day’. The reliability of the scale was satisfactory (α = .91).

Work engagement was assessed using the Italian version (42) of the nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) (43). The three sub-dimensions of vigour (e.g., ‘At my job I feel strong and vigorous’), dedication (e.g. ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’) and absorption (e.g. ‘I feel happy when I am working intensely’) are each represented by three items. All items were scored on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 = ‘never’ to 6 = ‘always/every day’. We followed Schaufeli and colleagues’ (43) recommendation and computed an overall work engagement score (α = .93).

Job satisfaction was assessed with a single item (44): ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?’, to which responses were given using a five-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘totally unsatisfied’ to 5 = ‘totally satisfied’.

Professional commitment was measured with six items (e.g. ‘I am proud to be a nurse/physician/healthcare operator’) taken from the Professional Identity Status Questionnaire (PISQ-5d);(30). Responses were given using a four-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’, 4 = ‘completely agree’). The reliability was satisfactory (α = .91).

Analysis Strategy

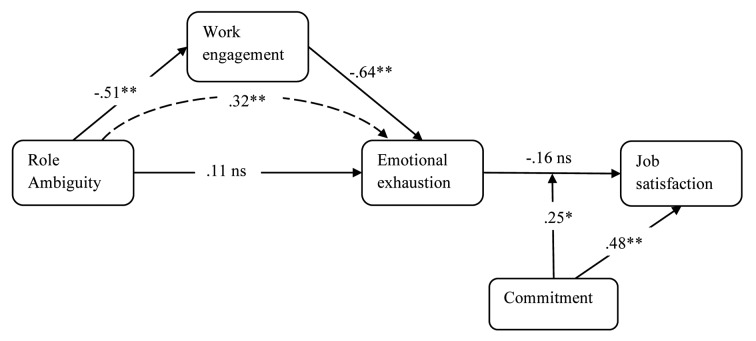

First we analysed zero-order correlations between the measured variables. We then tested our predicted model (see Figure 1) using path analysis with maximum likelihood and robust standard error estimation. All variables except job satisfaction were centred on the grand mean and the interaction between professional commitment and emotional exhaustion was computed after centring.

Figure 1.

Model of the relationships amongst variables and estimations.

*p = .05;** p < .01

Standardised coefficients are reported. Dotted line represents the indirect effect. N = 66

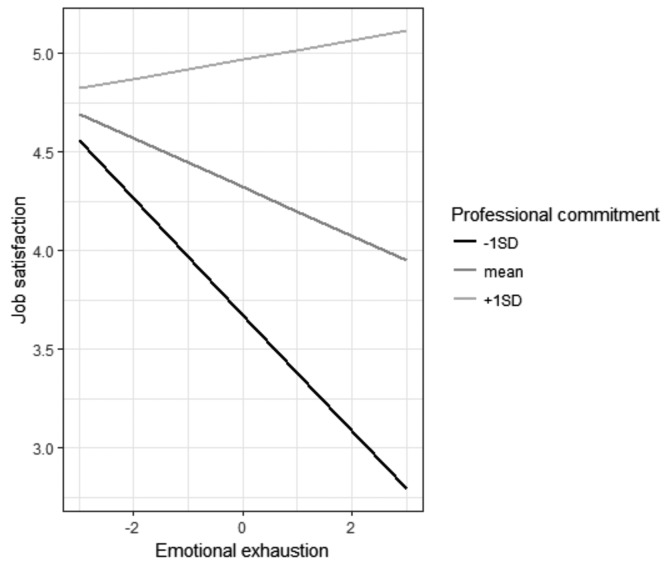

Figure 2.

Relationship between emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction at various levels of professional commitment

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Table 1 shows zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics for the measured variables. Job satisfaction was positively correlated with both work engagement and professional commitment, whereas emotional exhaustion and role ambiguity were negatively correlated with job satisfaction. Emotional exhaustion, in turn, was negatively correlated with work engagement and positively correlated with role ambiguity.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptive statistics of measured variables

| Work engagement | Emotional exhaustion | Role ambiguity | Professional commitment | Job satisfaction | |

| Work engagement | - | -.69** | -.50** | .73** | .68** |

| Emotional exhaustion | - | .43** | -.54** | -.48** | |

| Role ambiguity | - | -.40** | -.53** | ||

| Professional commitment | - | .67** | |||

| M | 4.65 | 3.11 | 2.66 | 3.20 | 4.15 |

| SD | 1.29 | 1.68 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 1.37 |

** p < .01. N = 66

Hypothesis Testing

Path analysis (see Figure 1) indicated that, unlike in the zero-order correlations, there was no direct effect of role ambiguity on emotional exhaustion, b = .21, SE = .25, Z = 0.86, p = .39. This is because, in accordance with hypothesis 1, the effect of role ambiguity on emotional exhaustion was completely mediated by work engagement, b = .63, SE = 0.15, Z = 4.09, p < .001, 90%CI = 0.327-0.927. Also as expected, professional commitment had a direct effect on emotional exhaustion,b = .79, SE = .23, Z = 3.43, p = .001. However, contrary to hypothesis 2 and the results of the correlation analysis, emotional exhaustion did not have a direct effect on job satisfaction, b = -.12, SE = .01,Z = 1.24, p = .22. Nevertheless, in accordance with hypothesis 3, this relationship was subject to an interaction between emotional exhaustion and professional commitment, b = .21, SE = .11, Z = 1.96, p = .05. More precisely, when professional commitment was low, emotional exhaustion had a negative effect on job satisfaction,b = -.30, SE = .13, Z = 2.30, p = .02, whereas when professional commitment was high, emotional exhaustion did not affect job satisfaction, b = .05, SE = .14, Z = 0.36, p = .72. Figure 1 shows the paths linking emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction and professional commitment.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the process that produces emotional exhaustion in health professionals, focusing on the hindrances they experience (45, 46), specifically role ambiguity and its consequences for work satisfaction.

Analysis showed that the effect of role ambiguity on emotional exhaustion was mediated by work engagement. Role ambiguity represents a psychosocial risk factor that influence workers’ wellbeing and level of performance. Workers who do not perceive clear goals put less effort into their tasks and perform less effectively. As a consequence, workers who lack clear goals show less engagement and hence experience lower wellbeing and job satisfaction (24, 25, 47). Harter, Schmidt and Hayes (28) also reported that workers’ engagement is negatively affected by difficulties such as not knowing what is expected of them. Role ambiguity generates uncertainty about how to attain one’s performance objectives and creates doubt about how tasks should be completed and how performance will be assessed (48). The increased effort required to cope with role ambiguity results in strain, which may manifest as frustration and fatigue, and can lead to employees feeling exhausted, worn out and dissatisfied. Thus the emotional consequences of role ambiguity can lead to increased turnover and intention to leave (49).

In fact, people experiencing hindrance stress will direct an amount of effort to face each demand, and they will probably use energy that would otherwise be dedicated to achieving challenge goals. Workers who have to deal with the negative emotions and psychological threat associated with hindrance demands use many resources that are detrimental to the motivational process of engagement (26, 27). Hence hindrance demands lead to exhaustion and frustration, which has negative consequence for work satisfaction.

In contrast, role fit predicts psychological meaningfulness, which has a positive influence on engagement. Professionals who are emotionally engaged tend to know what is expected of them, perceive that they are a member of an organisation where there are chances of development (28). If an individual has the opportunity to build resources through acquisition of mastery and personal growth, he or she will make more effort to complete work tasks and achieve personal own performance objectives.

Our results also indicated that emotional exhaustion only impairs job satisfaction when workers are not committed to their profession. In other words, professional commitment appears to protect exhausted professionals, helping them to manage the associated emotional distress and maintain adequate job satisfaction. This may be due to the fact professional commitment satisfies professionals’ need to belong and supplies professionals with roles, norms and identities that can compete with self and professional devaluation and emotional exhaustion. Thus, professional commitment appears to be an individual and collective resource that can help professionals to build a strong, resilient and satisfying professional identity.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, the use of cross-sectional questionnaires and a correlational design means that we must be cautious about inferring causal relationships among variables. Second, the sample size was small and composed mainly of nurses; in other words it was not representative of healthcare professionals generally. These two factors may reduce the generalisability of the results.

Implication for Nursing Management

Understanding the factors affecting job burnout is important from a practical point of view, because burnout has implications for workers’ psychosocial wellbeing, organisational effectiveness, and consequently for the patient care process. In fact, role ambiguity has serious consequences also for the efficiency of care process.

From the perspective of the strategic management of human resources, the clarification of professional roles helps to identify the expected behaviours with respect to integration into organisational patterns and culture. This intervention could allow defining significant and successful actions to achieve goals in line with values and mission of healthcare services.

These findings also suggest that managers should remove hindrance stressors in order to increase employees’ work engagement whilst at the same time providing challenge-related stressors in the workplace.

Finally, managers who want try to improve the work context in order to reduce job dissatisfaction and turnover should be aware of the protective function served by professional commitment. Professionals should always feel that they are treated as such and that their professional competence is recognised. This may help professionals not to forget their professional duties and mission with respect to patients’ care and to continue to perceive their job and profession as satisfactory.

The model developed from these findings suggests ways of improving employment strategies to enhance health professionals’ job satisfaction.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Cao X, Chen L, Tian L, Diao Y. The effect of perceived organisational support on burnout among community health nurses in China: The mediating role of professional self-concept. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(1):E77–E86. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12292. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun JW, Bai HY, Li JH, Lin PZ, Zhang HH, Cao FL. Predictors of occupational burnout among nurses: a dominance analysis of job stressors. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(23-24):4286–4292. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13754. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tunc T, Kutanis RO. Role conflict, role ambiguity, and burnout in nurses and physicians at a university hospital in Turkey. Nurs Heal Sci. 2009;11(4):410–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00475.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;(52):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Early Predictors of Job Burnout and Engagement. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(3):498–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han S-S, Han J-W, An Y-S, Lim S-H. Effects of role stress on nurses’ turnover intentions: The mediating effects of organizational commitment and burnout. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2015;12(4):287–296. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12067. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI. Burnout and Work Engagement: The JD–R Approach. Ssrn. 2014;1(1):389–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrosa E, Moreno-Jiménez B, Liang Y, González JL. The relationship between socio-demographic variables, job stressors, burnout, and hardy personality in nurses: An exploratory study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(3):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.09.003. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kendrick P. Comparing the effects of stress and relationship style on student and practicing nurse anesthetists. AANA J. 2000;68(2):115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon Burnout: A Systematic Review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.022. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou H, Gong YH. Relationship between occupational stress and coping strategy among operating theatre nurses in China: A questionnaire survey. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12094. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert VA, Lambert CE. Literature review of role stress/strain on nurses: An international perspective. Nurs Health Sci. 2001;3(3):161–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x. doi: doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert VA, Lambert CE, Petrini M, Li M, Zhang YJ. Workplace and personal factors associated with physical and mental health in hospital nurses in China. Nurs Heal Sci. 2007;9(2):120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00316.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzo JR, House RJ, Lirtzman SI. Role Conflict and Ambiguity in Complex Organizations. Adm Sci Q. 2006 doi: 10.2307/2391486. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao X, Chen L, Tian L, Diao Y, Hu X. Effect of professional self-concept on burnout among community health nurses in Chengdu, China: The mediator role of organisational commitment. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(19-20):2907–2915. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12915. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posig M, Kickul J. Extending Our Understanding of Burnout: Test of an Integrated Model in Nonservice Occupations. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003;8(1):3–19. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.8.1.3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu CI, Lee MS, Hsu HM. The impact of social support and job stress on public health nurses’ organizational citizenship behaviors in rural Taiwan. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23(6):496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00599.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn WA. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad Manag J. 1990;33(4):692–724. doi: 10.5465/256287. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn WA. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum Relations. 1992;45(4):321–349. doi: 10.1177/001872679204500402. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of burnout and engagement: a simple confirmatory analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3:71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis HS, Cunningham CJL. Linking nurse leadership and work characteristics to nurse burnout and engagement. Nurs Res. 2016;65(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000130. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demerouti E, Mostert K, Bakker AB. Burnout and Work Engagement: A Thorough Investigation of the Independency of Both Constructs. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15(3):209–222. doi: 10.1037/a0019408. doi: 10.1037/a0019408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J Organ Behav. 2004;25(3):293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawford ER, LePine JA, Rich BL. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(5):834–848. doi: 10.1037/a0019364. doi: 10.1037/a0019364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling M V, Boudreau JW. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(1):65–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2004;77(1):11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porath CL, Erez A. Overlooked but not untouched: How rudeness reduces onlookers’ performance on routine and creative tasks. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2009;109(1):29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.01.003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Hayes TL. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(2):268–279. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mañas MA, Díaz-Fúnez P, Pecino V, López-Liria R, Padilla D, Aguilar-Parra JM. Consequences of team job demands: Role ambiguity climate, affective engagement, and extra-role performance. Front Psychol. 2018:8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02292. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marletta G, Caricati L, Mancini T, et al. Professione infermieristica: Stati dell’identità e soddisfazione lavorativa. Psicol della Salut. 2014;(2):139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang Y. Turnover propensity and its causes among Singapore nurses: an empirical study. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2001;12(5):859–871. doi: 10.1080/713769669. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caricati L, La Sala R, Marletta G, et al. Work climate, work values and professional commitment as predictors of job satisfaction in nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(8):984–994. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12079. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenfield AC, Norman CS, Wier B. The effect of ethical orientation and professional commitment on earnings management behavior. J Bus Ethics. 2008;83(3):419–434. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9629-4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartunek JM. Intergroup relationships and quality improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;(20 Suppl 1Suppl_1):162–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046169. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.046169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caricati L, Guberti M, Borgognoni P, et al. The role of professional and team commitment in nurse-physician collaboration: A dual identity model perspective. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(5):464–468. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1016603. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1016603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caricati L, Mancini T, Sollami A, et al. The role of professional and team commitments in nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(2):E192–E200. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12323. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeves S, Lewin S, Espin S, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional Teamwork for Health and Social Care 2010. doi: 10.1002/9781444325027. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sollami A, Caricati L, Mancini T. Attitudes towards Interprofessional Education among Medical and Nursing Students: the Role of Professional Identification and Intergroup Contact. Curr Psychol. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9575-y. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sollami A, Caricati L, Mancini T. Does the readiness for interprofessional education reflect students’ dominance orientation and professional commitment? Evidence from a sample of nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;68:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.06.009. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzo JR, House RJ, Lirtzman SI. Role Conflict and Ambiguity in Complex Organizations. Adm Sci Q. 1970;15(2):150–163. doi: 10.2307/2391486. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. Teacher Burnout: A Research Agenda. In: Vandenberghe R, Huberman AM, eds. Understanding and Preventing Teacher Burnout; pp. 295–303. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511527784.021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balducci C, Fraccaroli F, Schaufeli WB. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9): A cross-cultural analysis. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2010;26(2):143–149. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale Preliminarty Manual. Occup Heal Psychol Unit -utr Univ. 2003 doi: 10.1037/t01350-000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wanous JP, Reichers AE, Hudy MJ. Overall job satisfaction: How good are singe-item measures? J Appl Psychol. 1997;82(2):247–252. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panari C, Levati W, Alfieri E, Tonelli M, Bonini A, Artioli G. La mappatura del ruolo come nuovo approccio di lettura di due professionisti ospedalieri: l’infermiere e l’operatore socio-sanitario. MECOSAN. 2015;(94):67–95. doi: 10.3280/mesa2015-094005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panari C, Levati W, Bonini A, Tonelli M, Alfieri E, Artioli G. The ambiguous role of healthcare providers: A new perspective in human resources management. Acta Biomed. 2016;87:49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In: Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A Transdisciplinary Approach. Vol 9789400756. 2014:43–68. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3-4. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rogalsky K, Doherty A, Paradis KF. Understanding the Sport Event Volunteer Experience: An Investigation of Role Ambiguity and Its Correlates. J Sport Manag. 2016;30(4):453–469. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2015-0214. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antón C. The impact of role stress on workers’ behaviour through job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Int J Psychol. 2009;44(3):187–194. doi: 10.1080/00207590701700511. doi: 10.1080/00207590701700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]