Abstract

A 56-year man with multiple comorbidities and recent septic embolization presented claudication intermittens (Rutherford3) at right lower limb and complaint in right lower quadrant at abdominal palpation. Duplex and computed tomography angiogram (CTA) showed a 64mm-pseudo-aneurysm (PA) originating from right common iliac artery, occlusion of external iliac and patency of hypogastric artery. An urgent endovascular approach was preferred. By left brachial percutaneous access, coil embolization (Balt SPI™ and Cook MReye™) of hypogastric and common iliac artery and deployment of Amplatzer Vascular PlugII™ into the common iliac artery were performed. Completion angiography showed exclusion of PA. One-day, 3-day and 1-month CTA proofed no vascularization of PA. No fever, no leukocytosis, no signs of infection occurred during follow-up and 10-month CTA showed the complete resolution of pseudoaneurysm. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: infected pseudoaneurysms, endovascular treatment, interventional radiology

Case report

A 56-year old man with multiple comorbidities (severe obesity, moderate chronic renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, smoking, cirrhosis, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease) presented to the out-patient clinic complaining intermittent claudication (Rutherford category 3) at right lower limb since 2 weeks. He received mitral valve replacement with coronary artery bypass graft three months before for acute endocarditis (Streptococcus gallolyticus), followed by brain septic embolization.

Physical examination revealed absence of right lower limb pulses with mild hypothermia and abdominal pain at deep palpation of the right lower quadrant without pulsating masses. Duplex ultrasound (DUS) found a perfused abdominal mass with 69mm in diameter in the right lower quadrant with steno-occlusion of right iliac axis. An emergency computer tomography angiography (CTA) revealed a right common iliac artery pseudoaneurysm (62x64 mm) with occlusion of external iliac artery, patency of hypogastric and recanalization of the right common femoral artery.

At admission, the patient had no fever and no leukocytosis (white blood cells=6,76x10^3), with anemia (Hb=9.1 g/dl), mild chronic renal failure (creatinine: 2.1 mg/dl) and high C reactive protein (CRP=97.2 mg/l). No blood culture or positron emission tomography were performed for absence of signs of concurrent systemic infection. No systemic antibiotics was undertaken for the same reason.

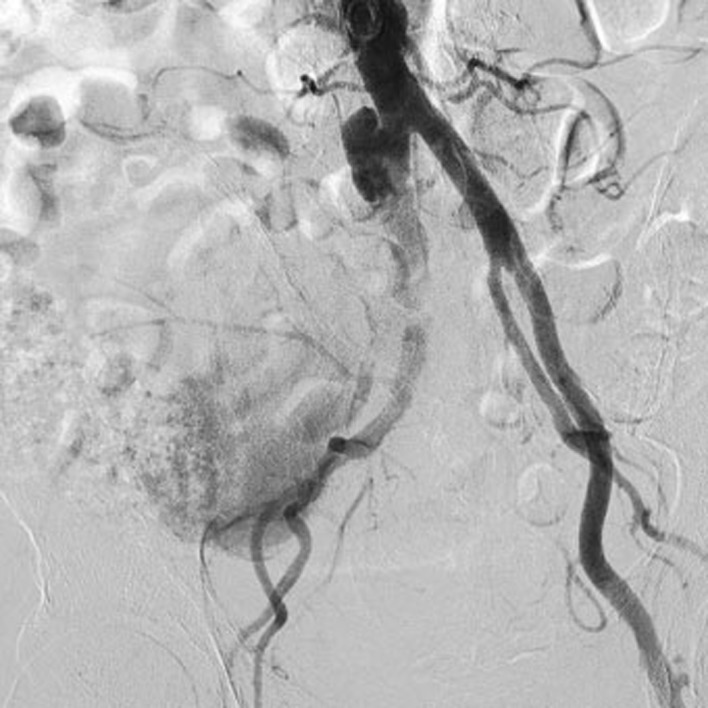

The following day, the patient underwent a digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (Fig. 1) through left brachial access (6F-sheath introducer, 90cm in length).

Figure 1.

Digital subtraction angiography throughout left humeral access: right common iliac artery pseudoaneurysm with occlusion of external iliac artery, patency of hypogastric and recanalization of the right common femoral artery

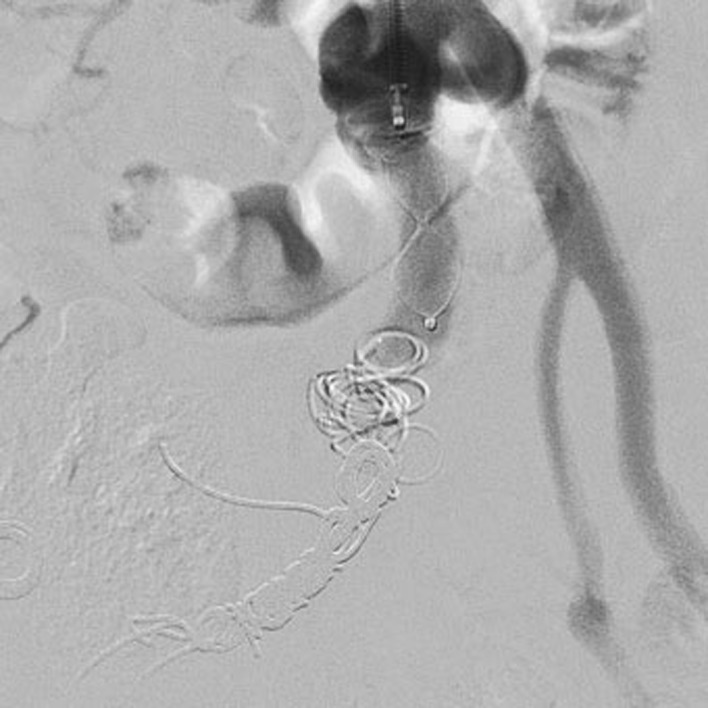

The embolization of the hypogastric artery with coils (Balt SPI™ and Cook Mreye™) and of the common iliac artery with Plug (16 mm-Amplatzer Vascular Plug II™) was performed.

The post-procedural DSA revealed the complete exclusion of the hypogastric artery, and the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2). The reperfusion of ipsilateral common femoral artery was maintained by collateral circulation.

Figure 2.

Post-procedural digital subtraction angiography: internal iliac artery embolization with coils (Balt SPI™ and Cook Mreye™) and with Plug at the origin of common iliac artery (6mm-Amplatzer Vascular Plug II ™). Complete exclusion of right common iliac artery, internal iliac artery and pseudoaneurysm.

During the post-operatory period, no hypotension or ischemia of the right lower limb occurred. A CTA confirmed the exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm. Similar findings were highlighted at CTA performed in the third post-procedural day. At discharge (6th post-procedural day), the patient had no fever, no leukocytosis (WBC=5,66x10^3) with stable anemia (Hb=9.1 g/dl) and renal function (creatinine=1.6 mg/dl). The abdominal pain disappeared, the right leg was normothermic and in hemodynamic compensation without rest pain, acute ischemia or neurological deficit.

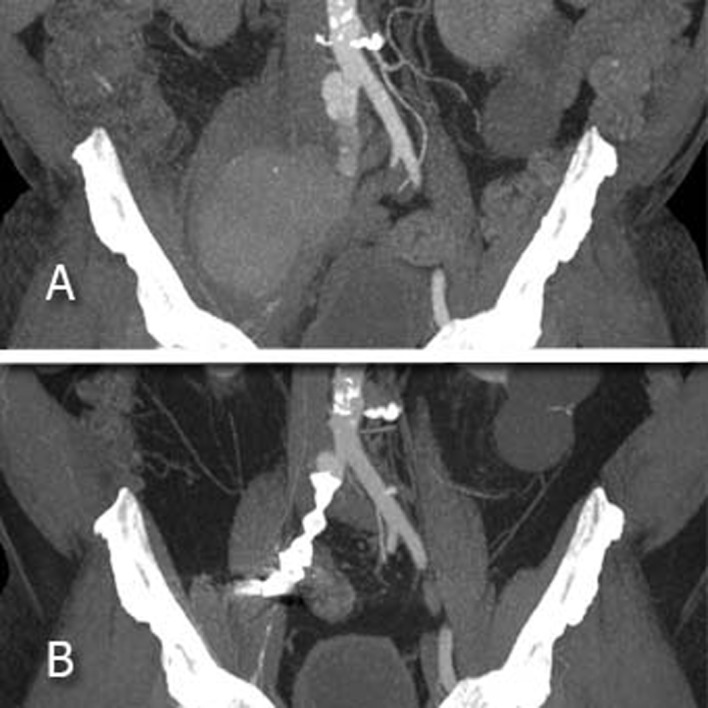

After one month, a CTA referred the exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm with a gradual reduction in the size. After 10 months, other CTA showed the complete resolution of the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 3) and the revascularization of the right common femoral artery by collateral circulation.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography angiography: A-first exam, before the interventional radiological procedure, that shows the pseudoaneurysm. B-control after 10 months, complete resolution of the pseudoaneurysm

Discussion

An arterial pseudoaneurysm is defined as presence of blood flow outside the wall of an artery and contained in surrounding tissues. The pseudoaneurysm is due to an arterial wall rupture, and may occur in any arterial segments. Its formation developed often as complication of a percutaneous access (femoral or brachial) (1), for an aneurysm rupture (cerebral (2), abdominal (3)), for anastomotic structural failure (para-anastomotic aneurysm (4)), infection (5), or trauma (6). The arterial rupture induces a gradual formation of pseudoaneurysm that can rapidly increase, with signs of hypotension and shock, or stabilize remaining slightly symptomatic.

The current case consists in a oligo-symptomatic iliac rupture after an episode of septic embolization (3 months before). However, the pseudoaneurysm was not considered infected for the lack of systemic infection signs and no evidence of infected etiology.

Currently, the CTA is the gold standard for the evaluation of a pseudoaneurysm, especially in aortic, visceral and intracranial districts (7, 8). DUS is reserved for peripheral vessels.

The best approach and treatment depend on the characteristics of pseudoaneurysm (location, morphology, presence and extent of the bleeding), the patient’s clinical condition and the experience of operators.

The treatment options are multiple and include conservative medical therapy, open surgery, endovascular treatment or hybrid treatment.

Small intracranial pseudoaneurysms, asymptomatic and without signs of growth or rupture, are generally managed with conservative treatment and follow-up by imaging (ultrasound or CTA) (9). The response to medical therapy can be variable (9): complete thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm with reduction in size, or increase in volume that needs more aggressive therapy.

Large extracranial or intracranial pseudo-aneurysms, symptomatic or ruptured, require immediate treatment in emergency/urgency setting (7). Pseudo-aneurysms secondary to arterial puncture are often treated with ultrasound-guided thrombin injection with high success rate (10). In aortic district, pseudo-aneurysms following surgical repair are mainly managed by stentgraft deployment avoiding demanding open reintervention (11, 12). Open surgery remain first option in case of infected pseudoaneurysm in drug abuser (13).

In the current case, considering localization, symptoms and size of pseudoaneurysm, the treatment was mandatory. The right external iliac artery was occluded, but endovascular or in-situ surgical recanalization (stentgraft or bypass graft, respectively) was not considered for high risk of infection.

The therapeutic options were: (I) the surgical ligation of right iliac axis; (II) the right hypogastric and common iliac artery embolization and exclusion with left aorto-uniiliac endograft. A surgical revascularization of right lower limb (aorto-femoral or femoro-femoral crossover bypass) was possible in case of right lower limb ischemia.

The surgical ligation of right axis was excluded for the high surgical risk of the patient, risk of infection and follow-up failure. An endovascular treatment was undertaken deploying less material as possible. Therefore, after pseudoaneurysm exclusion with embolization, aorto-uniiliac endografting was not considered essential. During the immediate post-procedural period, close clinical and radiological monitoring with multiple CTA was needed to assess the necessity of additional procedures (aorto-uniiliac endografting or femoral-femoral crossover bypass). The aorto-uniiliac endograft was not deployed for the complete exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm and the femoral-femoral bypass was not performed for clinical stability of the right lower limb.

The result during follow-up was optimal. After 10 months, complete resolution of pseudoaneurysm and no signs of persistent infection occurred.

Conclusions

The pseudoaneurysm formation is a possible event due to many causes. For abdominal pseudoaneurysms, the symptoms are sneaky and an early diagnosis is infrequent. The CTA is the diagnostic gold standard to characterize the place, the size, morphology, and to drive the therapeutic procedure. Based on the characteristics of the patient, the injury and the availability of operators, conservative therapy, interventional or surgical procedures are possible.

In our case, the use of endovascular treatment in urgency was effective, avoiding surgical complications and the dissemination of the infectious process. The complete resolution of the pseudoaneurysm after 10 months represents an excellent final result.

Ethical Approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Mlekusch W, Mlekusch I, Sabeti-Sandor S. Vascular puncture site complications - diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis. Vasa. 2016 Nov;45(6):461–469. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000551. Epub 2016 Jun 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nomura M, Mori K, Tamase A, Kamide T, Seki S, Iida Y, Nakano T, Kawabata Y, Kitabatake T, Nakajima T, Yasutake K, Egami K, Takahashi T, Takahashi M, Yanagimoto K. Pseudoaneurysm formation due to rupture of intracranial aneurysms: Case series and literature review. Neuroradiol J. 2017 Apr;30(2):129–137. doi: 10.1177/1971400916684667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu M, Weiss C, Fishman EK, Johnson PT, Verde F. Review of visceral aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015 Jan-Feb;39(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000156. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pogorzelski R, Fiszer P, Toutounchi S, Szostek MM, Krajewska E, Jakuczun W, Tworus R, Skórski M. Anastomotic aneurysms after arterial reconstructive operations--literature review. Pol Przegl Chir. 2014 Jan;86(1):48–56. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2014-0009. doi: 10.2478/pjs-2014-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moulakakis KG, Alexiou VG, Sfyroeras GS, Kakisis J, Lazaris A, Vasdekis SN, Brountzos EN, Geroulakos G. Endovascular management of infected iliofemoral pseudoaneurysms - a systematic review. Vasa. 2017 Jan;46(1):5–9. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000572. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000572. Epub 2016 Dec 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salsamendi J, Pereira K, Rey J, Narayanan G. Endovascular Coil Embolization in the Treatment of a Rare Case of Post-Traumatic Abdominal Aortic Pseudoaneurysms: Brief Report and Review of Literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:310.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.07.030. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.07.030. Epub 2015 Oct 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macedo TA, Stanson AW, Oderich GS, Johnson CM, Panneton JM, Tie ML. Infected aortic aneurysms: imaging findings. Radiology. 2004;231(1):250–257. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2311021700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Nakashima K, Minami K, Hayashi K. Visceral and peripheral arterial pseudoaneurysms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(3):741–749. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee W, Mossop P, Little A, Fitt G, Vrazas J, Hoang J, Hennessy O. Infected (Mycotic) Aneurysms: Spectrum of Imaging Appearances and Management. RadioGraphics. 2008;28:1853–1868. doi: 10.1148/rg.287085054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esterson YB, Pellerito JS. Recurrence of Thrombin-Injected Pseudoaneurysms Under Ultrasound Guidance: A 10-Year Retrospective Analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 Apr 13 doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.09063. doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.09063. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Z, Xu L, Raithel D, Qu L. Endovascular repair of proximal para-anastomotic aneurysms after previous open abdominal aortic aneurysm reconstruction. Vascular. 2016 Jun;24(3):227–32. doi: 10.1177/1708538115593194. doi: 10.1177/1708538115593194. Epub 2015 Jun 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallitto E, Gargiulo M, Freyrie A, Bianchini Massoni C, Mascoli C, Pini R, Faggioli GL, Ancetti S, Stella A. Fenestrated and Branched Endograft after Previous Aortic Repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Apr;32:119–27. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.10.018. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2015.10.018. Epub 2016 Jan 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayaraman S, Richardson D, Conrad M, Eichler C, Schecter W. Mycotic pseudoaneurysms due to injection drug use: a ten-year experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012 Aug;26(6):819–24. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.11.031. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.11.031. Epub 2012 Apr 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]