Abstract

Background:

Since 1963 Italian law (Law 292/1963, Legislative Decree n.81/2008), defines Tetanus Vaccination (TeV) as mandatory for defined occupational categories, including Construction Workers (CWs).

Materials and Methods:

An institutional survey on of CWs was performed in the Autonomous Province of Trento (Oct. 2016 - Apr. 2017). Vaccination booklets/certificate were retrieved recalling: TeV status (1), and TeV settings (2), i.e. basal schedule; year of last shot, healthcare providers who performed TeV, and TeV formulate(s).

Results:

Data about 205 CWs were collected (mean age 40.6±10.3 years; 78.0% <50 year-old, 71.7% born in Italy). Overall, 38.5% of CW had received last vaccination shot >10 years before the survey (mean: 8.8 ± 8.2 years). The majority of boosters had been administered by Vaccination Services of the Local Health Unit (47.3%), followed by Occupational Physicians (20.0%) and General Practitioners (11.2%). In 85.9% of CWs, a monovalent formulation was used. Combined TeV were mainly reported in CW who had received last vaccination shot in Vaccination Services (96.2%; p<0.001).

Conclusions:

TeV coverage rates in CWs are insufficient, and vaccination shots are frequently performed with inappropriate, monovalent formulates. As only professionals from Vaccination Services systematically employ combined vaccines and particularly Tdap, our results not only stress the opportunity for promoting TeV among CWs, but also the importance of improving reception of up to date official recommendations in Occupational Physicians, General Practitioner and professionals of Emergency Departments. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: tetanus, combined vaccines, tetanus toxoid, occupational health, vaccination, vaccine hesitancy

Introduction

Tetanus (commonly known as “lockjaw”) is a severe acute disease caused by toxinogenic strains of the bacterium Clostridium tetani and prevented by tetanus vaccine (TeV) and post-exposure prophylaxis (1-5). The spores of C tetani can enter the body through any injury contaminated with soils, street dust, human/animal faeces. Spores are nearly ubiquitous and, due to their continued presence in the environment, not only complete eradication is unlikely, but herd immunity plays no role in tetanus prevention (5, 6). In unvaccinated subjects, the case-fatality rate still remains significant, usually ranging from 10 to 80%, reaching 100% in absence of medical treatment (3, 5).

In the last decades, global incidence of Tetanus has decreased. In the majority of European Union (EU) countries, where most Member States have well-functioning immunization and surveillance systems, mortality of non-neonatal tetanus has declined by 85% between 1990 and 2015, recent estimated incidence being in 0.01 cases/100,000 inhabitants, with 65% of cases aged ≥65 years (7-11). Italy is a well-known exception: since 2006 Italy reports the highest number of cases in Europe, with an annual notification rate that remains stable between 0.9-1.0/100,000. Case-fatality ratio, estimated to be 39% at the global level, has dropped less sharply in Italy as compared to other EU countries (i.e. -47% between 1990 and 2015) (2, 7, 8, 11, 12). Nearly 90% of reported cases occurred in unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated subjects (2, 13), these figures stressing the inadequate protection rates of the Italian adult population; around 19% of Italian population is currently susceptible to tetanus (2, 13-15), and 10% of total population has only a basic, inadequate protection as a consequence of failing boost doses (2, 14).

Moreover, it is plausible that these figures may even deteriorate in the next decades. TeV was firstly introduced in 1938 for military personnel, becoming compulsory in 1963 for two-year-old children, and since 1968, for all newborns (L 292/1963). In the past, the rates of adequate protection in males were sustained by vaccination boosters received at conscription, but starting from 2003 compulsory military service has been discontinued for all subjects born after 1985 (2, 12, 13).

As a consequence, occupational TeV immunization has acquired an ever increasing relevance in order to sustain immunization rates (16, 17). In Italy, TeV is in fact the only vaccination whose status is legally defined as compulsory for workers engaged in activities considered to be at risk for interaction with tetanus toxin (e.g. construction, farming, waste collection and animal husbandry) (2, 12, 16, 18).

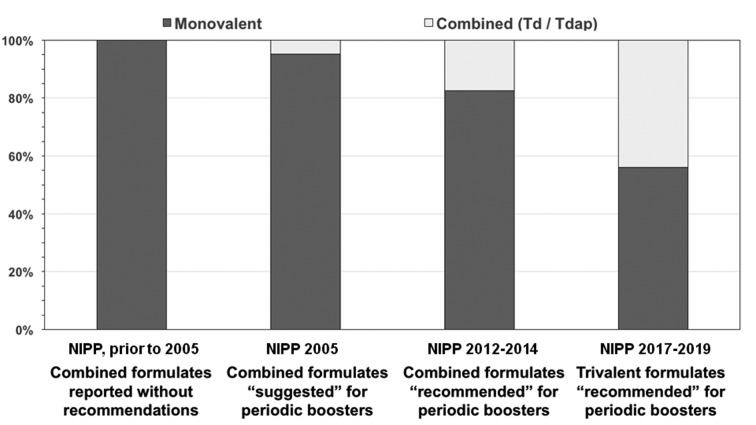

Starting with the National Immunization Prevention Plan (NIPP) in 1999, the Italian Ministry of Health has implemented reinforced vaccination policies in order to address falling vaccination rates, the increasing phenomenon of the vaccination hesitancy, and the re-emergence of anti-vaccination movements (19-23). Among the recommendations issued for TeV, NIPP strongly encourages the use of combined formulations for adult decennial boosters, initially (NIPP 2012-2014 ) with tetanus toxoid and reduced diphtheria toxoid (Td), whereas the more recent NIPP 2017-2019 officially recommends the active offer of trivalent formulations including tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) (4, 20, 24).

In the Autonomous Province of Trento (APT), the Operative Unit for Health and Safety in the Workplaces (UOPSAL, Italian acronym) represents the local governmental structure for the management and prevention of occupational injuries, occupational diseases, and work-related diseases in the workplaces. UOPSAL officers usually perform workplace interventions by visiting plants and/or construction sites without previous warning, evaluating whether parent companies comply with legislation concerning occupational health and safety conditions, and eventually establishing a deadline to solve any faults found (22, 25). Recently, National Plan for Health and Safety Prevention in Construction Settings 2014-2018 (in Italian, Piano Nazionale della Prevenzione in Edilizia, 2014-2018) has specifically included the assessment of health surveillance of CWs among the main objectives of UOPSAL’s workplace interventions. Among groups considered at higher risk for tetanus, people working in construction industry are notable because of the frequency of injuries/wounds potentially contaminated with spores of C tetani, their large number (7, 26), and the high share of workers having inadequate protection against tetanus (7, 27, 28). Consequently, TeV coverage assessment among CWs was identified among the primary objectives of the aforementioned surveillance activity, whose results are here presented in details.

Materials and Methods

Settings

APT is located in the Italy’s North East, covers a total area of 6,214 km2 (2,399 sq. mi) and has a population of 537,416 habitants (2015 census). According to available labor force statistics, in the last decade construction industry employed around 9.2% of total, and 14.8% of male workforce (i.e. around 20,000 adult age subjects/year) (29,30).

Framework

Since October 2016 to April 2017, UOPSAL officers systematically inspected all construction sites notified to the Local Health Authority of the APT: during the inspection, UOPSAL officers identified CWs who were working on the construction sites, and eventually acquired their institutional health and safety documentation, with specific focus on the TeV status of the workers. More in details, CWs were officially requested to provide a copy of the vaccine booklet, or a substitutive certificate.

Data analysis

Data about the type of vaccine received (T, Td, Tdap), the settings of the last vaccination shot (i.e. date; whether it was performed as a programmed/elective or an emergency shot after a penetrating injury), who actually performed it (i.e. General Practitioner, GP; Occupational Physician, OPh; or a healthcare professional from a Vaccination service of the Local Health Unit, Emergency Department, Military Service) were collected.

As recommended by Italian and the majority of international guidelines (3, 4, 15, 31-33), an “appropriate” TeV status was acknowledged for all patients who had completed the baseline schedule (i.e. for subjects vaccinated in infancy, a series of three tetanus-toxoid containing vaccine given in infancy, followed by two boosters at 6 and 11-15 years of age; for primary immunization in adults, 3 doses with a minimum of 1 month apart), plus a booster shot within the last 10 years.

A descriptive analysis was performed using means, standard deviation (SD and proportion as appropriate). Comparisons between CWs with an appropriate and not appropriate status, as well as between CWs whose last shot was performed with a monovalent formulation and those who had received a divalent/trivalent one, were performed through Student’s t test for continuous variables and by means of chi-square test for discrete variables (i.e. ethnicity, occupational status, age categories, items derived from the vaccine booklet). All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 for Macintosh (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY).

Ethics

This paper describes the results of a surveillance program put in place among institutional duties of the UOPSAL and was not primarily intended as a research project. The Italian legislation does not entail an ethical approval in this type of study and for this reason a formal ethical clearance was not required. Patient data are fully anonimized and no specific activity on human subjects was undertaken, other than that planned as regular surveillance activity.

Results

Characteristics of the sample (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographics of 205 Construction Workers (CWs) assessed during the survey, and characterization of their status regarding tetanus vaccine (TeV) and the recommendations issued by National Immunization Prevention Plans (NIPP)

| Total number of assessed CWs (n) | 205 | |

| Age (years; mean±SD) | 40.6±10.3 | |

| Age group (years; n, %) | ||

| <30 | 35,17.1% | |

| 30-39 | 64, 31.2% | |

| 40-40 | 61, 29.8% | |

| ≥50 | 45, 22.0% | |

| Occupational status (n, %) | ||

| Employee | 178,86.8% | |

| Self-employed | 27,13.2% | |

| Migration Background (n, %) | ||

| Italian-born people of them: | 147,71.7% | |

| Born before 1968 (compulsory tetanus vaccine for all newborns) | 40, 27.2% | |

| Born after 1985 (suspension of compulsory military service) | 32,21.9% | |

| Foreign-born people of them: | 58, 28.3% | |

| Europe | 48, 82.8% | |

| India and South-West Asia | 5,8.6% | |

| South America | 4,6.9% | |

| North Africa and East Mediterranean | 1,1.7% | |

| Time since last TeV shot (years; mean ± SD) | 8.8 ± 8.2 | |

| TeV status (n, %) | ||

| Basal schedule completed, at least 1 shot in the previous 10 years | 106,51.7% | |

| Basal schedule completed, last shot prior than 10 years | 59, 38.5% | |

| Not mailable | 20, 9.8% | |

| Last TeV shot, settings (n, %) | ||

| Vaccination services of the Local Health Unit | 97,47.3% | |

| Occupational Physician | 41,20.0% | |

| GeneraI Practitioner | 23,11.2% | |

| Emergency Department | 13,6.3% | |

| Military service | 11,5.4% | |

| Unknown | 20, 9.8% | |

| Last TeV shot was performed ... (n, %) | ||

| as a Monovalentformulation (T) | 159,77.6% | |

| as a Divalentformulation (Td) | 9,4.4% | |

| as a 1Vivaientformulation (TdaP) | 17, 8.3% | |

| Unknown | 20, 9.8% | |

| Official Recommendations for last vaccination shots (n, %) | ||

| NIPP 2017-2019 (recommendation for Tdap) | 25,12,2% | |

| NIPP 2012-2014 (recommendation forTd) | 70,34.1% | |

| NIPP (Td/Tdap suggested, not recommended) | 66, 32.2% | |

| NIPP prior to 2005 (neither suggestions or recommendations for Td/Tdap) | 24,11.7% | |

| Not Available | 20, 9.8% |

A total of 205 CWs were included in the study (1.1% of all employed in construction industry in the APT), all of male sex, with a mean age of 40.6±10.3 years. The majority of sampled CWs was of Italian origin (71.7%): of them, 27.2% were born before 1968 (when TeV was made compulsory for all newborns), and 21.9% after 1985, being exempted from military service and therefore did not receive vaccination booster at conscription.

Among Foreign-born people, the majority of them was of European origin (n=48, 82.8%), followed by people from India and South-West Asia (8.6%), South America (6.9%), North Africa and East Mediterranean (1.7%). Respectively to the occupational status, the majority of sampled CWs were salaried employees (86.8%), whereas 27 were either self-employed or employers (13.2%).

Vaccination status was available in 90.2% of assessed CWs and, at the time of the analysis, all had completed the basal schedule, with a mean time-lapse from the last vaccination shot of 8.8±8.2 years. More precisely, 106 of them (51.7% of the total sample) had received at least 1 shot in the previous 10 years and were consequently acknowledged as having an “appropriate” TeV status, whereas in 59 cases (38.5%) last vaccination shot was older than 10 years. However, all of them had spontaneously performed vaccination booster before delivering certification to UOPSAL officers.

Overall, 12.2% of sampled CWs had received a TeV that was performed during the validity of NIPP 2017-2019, 34.1% of NIPP 2012-2014, 32.2% of NIPP 2005, 11.7% of NIPP prior to 2005.

Focusing on the vaccination settings, nearly half of the sample with a documented vaccination status (47.3%), had received last vaccination shot by healthcare providers from Vaccination Services of Local Health Units, followed by the OPhs (20.0%), GPs (11.2%), and professionals from Military Service at conscription (5.4%). Eventually, in 13 CWs (5.9%) last vaccination shot was performed in the Emergency Department following a previous injury.

In the majority of workers, TeV was performed as a monovalent formulation (T, 77.6%), whereas 4.4% had received a divalent formulation (Td) and 8.3% a trivalent one (Tdap).

Factors associated with TeV status

As shown in Table 2, no significant differences in terms of age, age group, year of birth, ethnicity and occupational status was identified between CWs having an up-to-date TeV status and subjects lacking vaccination boosters.

Table 2.

Comparisons of recalled demographic factors between CWs with an appropriate (i.e. a documented primary series of 3 doses with an interval of at least 4 weeks between the doses, plus a booster shot within the last 10 years) and a not appropriate TeV status

| Variable | Vaccination status | Chi squared test p value | |

| Appropriate (n/106,%) | Not appropriate (n/99,%) | ||

| Age | 41.0±10.2 | 40.1 ±10.4 | 0.537 |

| Age group | |||

| <30 | 15,13.9% | 20, 20.6% | 0.628 |

| 30-39 | 36, 33.3% | 28, 28.9% | |

| 40-49 | 33, 30.6% | 28, 28.9% | |

| ≥50 | 24,22.2% | 21,21.6% | |

| Migration background | |||

| Italian-born people | 76,70.4% | 71, 73.2% | 0.769 |

| Foreign-born people | 32,29.6% | 26, 26.8% | |

| Year of Birth (only Italian-born people) | |||

| Born before 1968 | 22,28.9% | 18, 25.4% | 0.761 |

| Born in 1968 or thereafter | 54,71.1% | 53, 74.6% | |

| Born before 1986 | 13,17.3% | 19, 26.8% | 0.240 |

| Born in 1986 or thereafter | 62,82.7% | 52, 73.2% | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Employee | 14,13.0% | 13,13.4% | 1.000 |

| Self-employed | 94,87.0% | 84. 86.6% | |

Focusing on the formulates received by CWs (Table 3), no significant differences were identified in terms of demographics and occupational status for monovalent or combined vaccines. On the contrary, when focusing on the vaccination settings, the share of combined formulation was significantly higher in subjects who had received last vaccination shot in Vaccination Services (96.2% vs. 45.3%), whereas TeV by other professionals were more frequently performed as monovalent formulations. Again, a significant difference in the shares of formulation used for TeV was reported when focusing on the framework of reference recommendations: not only 42.3% of all combined formulations was reported after the enforcement of NIPP 2017-2019, but the ratio combined/monovalent vaccine increased from 0 in the years before NIPP 2005-2007, to 0.05 after its enforcement, to 0.21 after the enforcement of NIPP 2012-2014, and eventually to 0.79 after the enforcement of NIPP 2017-2019 (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Comparisons of recalled demographic factors and vaccination settings between CWs having received last shot of tetanus vaccine (TeV) as a monovalent formulation and as a combined tetanus-diphtheria (Td) or tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) one

| Variable | Formulation employed for last TeV shot | p value | |

| Monovalent (n/159, %) | Combined (Td / Tdap) (n/26, %) | ||

| Age | 40.6 ± 9.6 | 38.4 ± 9.6 | 0.418 |

| Age group | |||

| <30 | 29,18.2% | 4,15.4% | 0.126 |

| 30-39 | 58. 36.5% | 4,15.4% | |

| 40-40 | 39,24.5% | 10, 38.5% | |

| ≥50 | 33,20,8% | 8, 30.8% | |

| Migration background | |||

| Italian-born people | 108,67.9% | 21,80.8% | 0.275 |

| Foreign-born people | 51,32.1% | 5,19.2% | |

| Year of Birth (only Italian-born people) | |||

| Born before 1968 | 28, 25.9% | 8,38.1% | 0.383 |

| Born in 1968 or thereafter | 80. 74.1% | 13,61.9% | |

| Born before 1986 | 25,23.4% | 4,19.0% | 0.883 |

| Born in 1986 or thereafter | 82. 76.6% | 17,81.0% | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Employee | 21,13.2% | 4,15.4% | 1.000 |

| Self-employed | 138,86.8% | 22,84.6% | |

| Vaccination settings | |||

| Vaccination Services | 72,45.3% | 25,96.2% | <0.001 |

| Occupational Physicians | 40, 25.2% | 1,3.8% | |

| General Practitioners | 23,14.5% | 0,- | |

| Emergency Department | 13,8.2% | 0,- | |

| Military services | 11,6.9% | 0,- | |

| Vaccination references | |||

| NIPP 2017-2019 | 14,8.8% | 11,42.3% | <0.001 |

| NIPP 2012-2014 | 57,35.8% | 12,46.2% | |

| NIPP 2005-2007 | 60, 37.7% | 3,11.5% | |

| Prior NIPP 2005-2007 | 28,17,6% | 0,- | |

Notes. NIPP: National Immunization Prevention Plan

Figure 1.

Discussion

Tetanus immunization in Italy is a long-lasting problem (2, 7, 12-14): not only TeV rates appear to be largely unsatisfactory when compared to other European countries, but some reports suggests even worse estimates for certain occupational settings (34-36). More specifically, previous studies about Italian construction industry found that between 20% to 40% of CWs may have an inadequate protection, either in terms of serology (7) or up-to-date vaccination status (16). Moreover, in a recent survey from the same geographical settings, i.e. APT, 41.6% of 707 agricultural workers (AWs) had either not completed basal schedule nor received a TeV booster in the last 10 years (18). This is particularly worrisome, as around 20% of tetanus cases usually follow an apparently minor and somehow unnoticed injury, and workers may therefore lack emergency catch-up vaccinations or even post-exposure prophylaxis with immune serum (4, 5, 33, 37). Even though TeV status is only a proxy of actual immunization status, and even intervals longer than 10 years may be eventually more cost-effective and represent a better estimate of physiological reduction of antibody levels (31, 36, 38-42), our results are consistent with available evidence, and collectively underscore the necessity for improving TeV rates and increase vaccine surveillance in adult population performing works at risk for burns and injuries potentially contaminated with soils, street dust, human/animal faeces (2, 16, 20, 24).

Interestingly enough, the majority of CWs with inadequate TeV status spontaneously performed lacking vaccination shots, or even started the basal schedule when no documentation was available: these results are consistent with previous reports suggesting that workers from lower socio-economic status and education level (7, 43, 44), such as CWs and AWs, frequently assumed at higher risk for misconceptions and hesitancy (45, 46), actually may retain relatively low shares of vaccine hesitancy, and that the main reason for lacking a vaccination booster in these workers is usually the lack of time or even the simple forgetfulness (2, 10, 12).

Not coincidentally, NIPP 2017-2019 has stressed that every contact with a physician should be used to check vaccination status, and that decennial TeV boosters should be actively offered and performed by exploiting all the available opportunities (e.g. recertification for driving licence, periodic medical assessment etc.) (27). In other words, more recent guidelines design a proactive role for GPs and OPhs (47, 48), in particular for older age group. In this regard, even though some reports have suggested that TeV rates significantly decline with age, ratios of appropriate vs. not appropriate TeV status was similar across all age groups, and even cut-off potentially associated with differences in the immunization status, i.e. being born before the introduction of compulsory tetanus immunization for all newborns (i.e. 1968) or after suspension of conscription (i.e. 1985), did not affect vaccination rates. Actually, not only general attitude of CWs towards TeV might be diffusely better than previously supposed, but it should also be stressed that a significant share of sampled CWs had received last TeV shot in Emergency Departments, and such interventions have been described as significant opportunities to catch up with appropriate vaccination status in older workers, ultimately increasing general vaccination rates (2, 7, 16, 18, 49).

Aside assessing vaccination rates in CWs, this survey gave us the opportunity to evaluate the intervention of several healthcare providers in the vaccination practice, and our results are somehow disappointing. Although official recommendations have been issued in order to promote vaccination booster as combined formulates (since 2012 Td and, more recently Tdap), the large majority of CWs had received a monovalent formulate only including tetanus toxoid. Moreover, we identified a significantly heterogeneous adaptation to the recommendations of NIPPs by different healthcare providers, as nearly all combined formulations were delivered in Vaccination Services of Local Health Units, and conversely GPs, OPhs as well as Emergency Departments still largely employ monovalent formulates. Such figures are therefore consistent with previous reports, and may found some presumptive explanations (16, 18). First and foremost, while workers considered at risk for tetanus may receive TeV without cost in Vaccination Services, when immunization is performed by other professionals such as GPs and OPhs, it is not compensated. Since the costs are on employer’s charge, he may have some hesitancy towards the additional expenditures determined by the combined formulations (21-24).

Second, some previous reports have suggested that the knowledge of OPhs and GPs about vaccines and VPDs are neither regularly up-to-date or consistently based upon scientific evidence, rather frequently residing on personal beliefs and misconceptions (48, 50, 51). Consequently, our results may simply reflect the inappropriate reception of recently issued vaccine recommendations (21-24, 48-51).

Some limits of this survey should be considered. Firstly, the operative definition of inadequate vaccination status. As previously stated, a 10 years interval between the vaccine booster is a diffuse but arbitrary cut-off, as the excessive use of boosters in a restricted time frame could potentially result in anergy on the one hand, and in the severe side effects on the other hand, whereas a significant share of subjects lacking periodic booster may actually maintain an efficient protection (32). Moreover, the lack of vaccine booklet should not be automatically addressed as the lack of previous vaccinations or even as a lack of effective immunization (7, 12, 32, 49, 52).

Second, as a result of the primary aim of this survey, i.e. assess the vaccination rates among CWs in a restricted geographic area, we did not evaluate actual determinants of vaccination acceptance/hesitance/refusal among sampled workers. Even though our results are somehow consistent with previous reports that explicitly assessed a positive attitude of CWs towards TeV, we cannot rule out that the large share of workers spontaneously performing catch up vaccinations did it as they felt the request of documentation by UOPSAL’s officers as a sort of informal warning, perceiving the possibility of significant fines whether the TeV status was ultimately ascertained as inappropriate, and ultimately representing a sort of “social desirability bias” (53, 54).

Third, it is important to underscore that the study population was not randomly selected. Moreover, although the sampling was somehow systematic, including all workers involved in active construction sites of the APT during the study period, it mainly included CWs from APT and nearby provinces from Northern Italy: as Italy is very heterogeneous in terms of tetanus vaccination rate, our results should be cautiously interpreted as representative of the National level (2, 7, 12-14, 44, 55).

Fourth, National setting of Italy on Occupational Health and Safety law is neither typical or representative of all developed countries. Actually, Italian law enforces occupational health surveillance, with occupational health services ultimately available to all workers, and defines specific occupational recommendations for TeV (16, 17, 22, 25). Consequently, our results cannot be easily generalized even at European level.

In conclusion, our study enlightens that TeV rates still remain unsatisfactory even among a high-risk occupational groups such as CWs, and that updated guidelines and recommendations encounter significant difficulties in their diffusion across all healthcare providers. Consequently, our results stress the opportunity for sustaining a more active role of GPs and OPhs in promoting and performing vaccinations, as well as in monitoring vaccine status of their patients, the latter being a critical aspect for a immunizations with very long recommended between-shots intervals. Therefore, it is also crucial to provide GPs and OPhs with up-to-date information about vaccines and their recommendations, assuring that they will be able to adequately advice and inform patients regarding vaccinations.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Luisto M, Seppalainen AM. Tetanus caused by occupational accidents. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1992;18:323–326. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filia A, Bella A, Hunolstein von C, Pinto A, Alfarone G, Declich S, et al. Tetanus in Italy 2001-2010: a continuing threat in older adults. Vaccine. 2014;32:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Oganization. Tetanus vaccines: WHO position paper: February 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92:53–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Tetanus vaccines: WHO position paper, February 2017 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2017. pii: S0664-410X(17)30228-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Thwaites CL, Loan HT. Eradication of tetanus. Br Med Bull. 2015;116:68–77. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldv044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thwaites CL, Beeching NJ, Newton CR. Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 2015;385:362–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapisarda V, Bracci M, Nunnari G, Ferrante M, Ledda C. Tetanus immunity in construction workers in Italy. Occup Med. 2014;64:217–219. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Stockholm: ECDC; 2015. Annual epidemiological report 2014; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabibi R, Vaccalini R, Barassi A, Bonizzi L, Brambilla G, Consonni D, et al. Occupational exposure to zoonotic agents among agricultural workers in Lombardy Region, northern Italy. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2013;20:676–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Öncü S, Önde M, Öncü S, Ergin F, Öztürk B. Tetanus seroepidemiology and factors influencing immunity status among farmers of advanced age. Health policy. 2011;100:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyu HH, Mumford JE, Stanaway JD, Barber RM, Hancock JR, Vos T, et al. Mortality from tetanus between 1990 and 2015: findings from the global burden of disease study 2015. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:179. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4111-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valentino M, Rapisarda V. Tetanus in a central Italian region: scope for more effective prevention among unvaccinated agricultural workers. Occup Environ Med. 2001;51:114–117. doi: 10.1093/occmed/51.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedalino B, Cotter B, Ciofi degli Atti ML, Mandolini D, Parroccini S, Salmaso S. Epidemiology of Tetanus in Italy in years 1971-2000. Euro Surveill. 2002;7:pii=357. doi: 10.2807/esm.07.07.00357-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroffolini T, Giammanco A, Giammanco G, Maggio M, Genovese R, De Mattia D, et al. Immunity to tetanus in the 3-20 year age group in Italy. Public Health. 1997;111:19–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger B. Adult vaccination against tetanus and diphtheria: the European perspective. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;187:93–99. doi: 10.1111/cei.12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riccò M, Cattani S, Veronesi L, Colucci ME. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of construction workers towards tetanus vaccine in Northern Italy. Ind Health. 2016;54:554–564. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2015-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manzoli L, Sotgiu G, Magnavita N, Durando P; National Working Group on Occupational Hygiene of the Italian Society of Hygiene, Preventive Medicine and Public Health (SItI). Evidence-based approach for continuous improvement of occupational health. Epidemiol Prev. 2015;39:S81–S85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riccò M, Razio B, Panato C, Poletti L, Signorelli C. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Agricultural Workers towards Tetanus Vaccine: a Field Report. Ann Ig. 2017;29:239–255. doi: 10.7416/ai.2017.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tafuri S, Gallone MS, Cappelli MG, Martinelli D, Prato R, Germinario C. Addressing the anti-vaccination movement and the role of HCWs. Vaccine. 2014;32:4860–4865. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonanni P, Ferro A, Guerra R, Iannazzo S, Odone A, Pompa MG, et al. Vaccine coverage in Italy and assessment of the 2012-2014. National Immunization Prevention Plan Epidemiol Prev. 2015;39:145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonanni P, Bergamini M. Factors influencing vaccine uptake in Italy. Vaccine. 2002;20:S8–S12. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Signorelli C, Riccò M, Odone A. The Italian National Health Service expenditure on workplace prevention and safety (2006-2013): a national-level analysis. Ann Ig. 2016;28:313–318. doi: 10.7416/ai.2016.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biasio LR, Corsello G, Costantino C, Fara GM, Giammanco G, Signorelli C, et al. Communication about vaccination: A shared responsibility. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:2984–2987. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1198456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Signorelli C, Odone A, Bonanni P, Russo F. New Italian immunisation plan is built on scientific evidence: Carlo Signorelli and colleagues reply to news article by Michael Day. BMJ. 2015;351:h6775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farina E, Bena A, Fedeli U, Mastrangelo G, Veronese M, Agnesi R. Public injury prevention system in the Italian manufacturing sector: What types of inspection are more effective? Am J Ind Med. 2016;59:315–321. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Confindustria Servizi Innovativi e Tecnologici, Federcostruzioni. Il Sistema delle Costruzioni in Italia. Rome: Confindustria; 2013 [Italian] Available at: http://www.confindustriasi.it/files/FC%2020.11.13_Low%20Res%202_VERS_ONLINE.pdf. Accessed on: September 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Böhmer MM, Walter D, Krause G, Müters S, Göβwald A, Wichmann O. Determinants of tetanus and seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in adults living in Germany. Hum Vaccin. 2014;7:1317–1325. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.12.18130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang P, Zimmermann H, Piller U, Steffen R, Hatz C. The Swiss National Vaccination Coverage Survey, 2005-2007. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:S96–S108. doi: 10.1177/00333549111260S212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Labour Agency of the Autonomous Province of Trento. Local Job Creation: How Employment and Training Agencies can Help. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/localjobcreationreporttrento.htm . Accessed on: September 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agnolin C, Ioriatti C, Pontalti M, Venturelli MB. IFP Experiences in Trentino, Italy. Acta Hortic. 2000;525:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Italian Ministry of Health. Tetanus prophylaxis measures. Nov 11, 1996. Available at: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_normativa_1529_allegato.pdf. Accessed on: September 15, 2017.

- 32.Borella-Venturini M, Frasson C, Paluan F, De Nuzzo D, Di Masi G, Giraldo M, et al. Tetanus vaccination, antibody persistence and decennial booster: a serosurvey of university students and at-risk workers. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145:1757–1762. doi: 10.1017/S0950268817000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal S, Samuelson J, Reed J, Yakubu A, Ncube B, Baggaley R. Tetanus disease and deaths in men reveal need for vaccination. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94:613–621. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.166777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baratin D, Del Signore C, Thierry J, Caulin E, Vanhems P. Evaluation of adult dTPaP vaccination coverage in France: experience in Lyon city, 2010-2011. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:940. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poethko-Müller C, Schmitz R. [Vaccination coverage in German adults] Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2013;56:845–857. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1693-6. in German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner KS, White JM, Andrews NJ, Borrow R, Stanford E, Newton E, et al. Immunity to tetanus and diphtheria in the UK in 2009. Vaccine. 2012;30:7111–7117. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alici DE, Sayiner A, Unal S. Barriers to adult immunization and solutions: Personalized approaches. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13:213–215. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1234556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn HE, McIntyre P. Tetanus in the elderly - An important preventable disease in Australia. Vaccine. 2007;25:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ölander RM, Aureanen K, Härkänen T, Leino T. High tetanus and diphtheria antitoxin concentrations in Finnish adults - Time for new booster recommendations? Vaccine. 2009;27:5295–5298. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardner P. Issues related to the decennial tetanus-diphtheria toxoid booster recommendations in adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner P, LaForce MF. Protection against Tetanus. N Eng J Med. 1995;333:599–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Assessing Adult Vaccination Status at Age 50 Years. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1995;44:561–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hassan HA, Houdmont J. Health and safety implications of recruitment payments in migrant construction workers. Occup Med. 2014;64:331–336. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abbate R, Di Giuseppe G, Marinelli P, Angelillo IF, De Stefano A, Ferrara M, et al. Appropriate tetanus prophylaxis practices in patients attending Emergency Departments in Italy. Vaccine. 2008;26:3634–3639. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccinations from a global perspectives: a systematic review of published literature, 2007-2012. Vaccine. 2014;32:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloom BR, Marcuse E, Mnookin S. Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy. Science. 2014;24(344):339. doi: 10.1126/science.1254834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fortunato F, Tafuri S, Cozza V, Martinelli D, Prato R. Low vaccination coverage among italian healthcare workers in 2013. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:133–139. doi: 10.4161/hv.34415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Betsch C, Wicker S. Personal attitudes and misconceptions, not official recommendations guide occupational physicians’ vaccination decisions. Vaccine. 2014;32:4478–4484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orsi GB, Modini C, Principe MA, Di Muzio M, Moriconi A, Amato MG, et al. Assessment of tetanus immunity status by tetanus quick stick and anamnesis: a prospective double blind study. Ann Ig. 2015;27:467–474. doi: 10.7416/ai.2015.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riccò M, Cattani S, Casagranda F, Gualerzi G, Signorelli C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of Occupational Physicians towards vaccinations of Health Care Workers: a cross sectional pilot study from North-Eastern Italy. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30:775–790. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riccò M, Cattani S, Casagranda F, Gualerzi G, Signorelli C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of Occupational Physicians towards seasonal influenza vaccination: a cross-sectional study from North-Eastern Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2017;58:E141–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veronesi L, R V, Bizzoco S, Colucci ME, Affanni P, Paganuzzi F, et al. Vaccination status and prealence of enteric viruses in Internationally adopted children. The case of Parma, Italy. Acta Biomed. 2011;82:208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oh SS, Mayer JA, Lewis EC, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Elder JP, et al. Validating outdoor workers’ self-report of sun protection. Prev Med. 2004;39:798–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Riccò M, Razio B, Poletti L, Panato C. Knowledge, attitudes, and sun-safety practices among agricultural workers in the Autonomous Province of Trento, North-Eastern Italy (2016) G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2017; forthcoming doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.17.05672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Signorelli C, Riccò M. [The health-environment interaction in Italy] Ig Sanita Pubbl. 2012;68:374–380. In Italian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]