Abstract

Herpes simplex virus encephalitis (HSE) is the most common cause of letal encephalitis and its prevalence appears higher among oncologic patients who undergo brain radiotherapy (RT). We describe a case of 76-year-old woman with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) who developed HSE shortly after brain RT. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (CSF) was normal and the diagnosis was driven by brain MRI and EEG. Prompt introduction of antiviral therapy improved the clinical picture. We highlight the importance of EEG and brain MRI for the diagnosis and suggest the possibility of antiviral profilaxys in oncologic patients who undergo brain RT. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV1), encephalitis, glioblastoma, radiotherapy

Background and aim of the work

GBM is the most common fatal primary brain tumor in adults, representing approximately 50% of brain cancer in patients older than 65 years old (1). The median survival in treated patients is about 12-14 months from diagnosis (2,3). HSE is the most common cause of sporadic letal encephalitis (4) with an incidence of approximately 2-4 cases per million per year (5).

Reports exist of co-occurrence of HSE and GBM, of HSE following GBM, and of GBM mimicking HSE (6).

As far as we know there is no clear association in literature between brain RT and HSE, even if several case reports documented HSE shortly after whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) in oncologic patients with GBM (5).

In patients affected by GBM, HSE diagnosis is particularly challenging because of absent or mild CSF pleocytosis, atypical clinical features, negative neuroimaging in early phases.

Clinical Vignette

We report a case of 76-year-old woman with a right-sided cerebral GBM (WHO IV stadium), who developed HSE shortly after RT. We discuss the possible association between tumor and opportunistic infections and the potential utility of antiviral profilaxys in HSV1 oncologic patients who undergo RT. In September 2016an Italian 76-year-old woman received the diagnosis of right frontal post-central GBM by cerebral biopsy. Neurosurgical resection was not possible because of tumor’s size and location. Therefore she was treated with RT and subsequently adjuvant chemotherapy.

In December 2016, few weeks after RT, she was admitted to our Emergency Department presenting fever, confusion, lethargy, subacute cognitive decline and recurrent focal seizures with left motor onset. At neurological examination she was stunned, could be aroused with vigorous stimulation, presenting localizing motor response (Glasgow Coma Scale, GCS 9), without focal deficits.

Laboratory tests including white blood cell (WBC) count and biochemical profile were unremarkable except for hyponatriemia (124 mEq/L). Chest X-ray (CXR) showed a possible lobe infiltrate, suspected for pneumonia. Brain computer tomography (CT) excluded tumor progression.

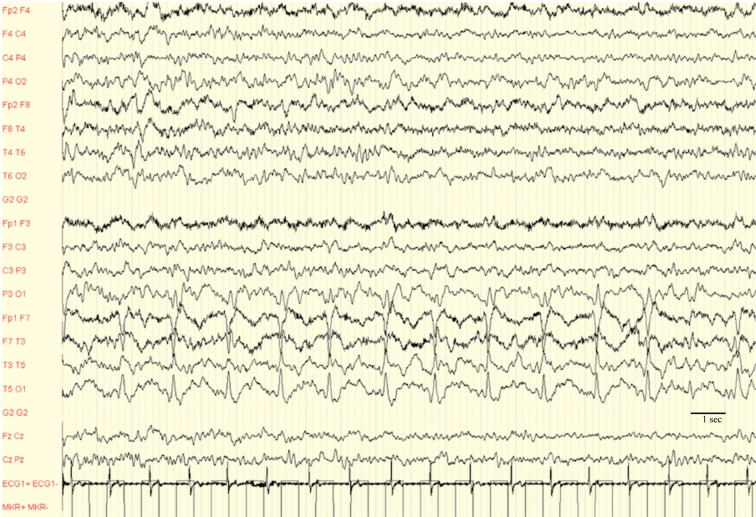

The EEG demonstrated mild generalized background slowing and 0.5-0.75 Hz lateralized periodic discharges (LPD) in left temporal region, highly suggestive of HSE (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

EEG: 0.5-0.75 Hz lateralized periodic discharges (LPD) in left temporal region, sensitivity 70 μV

The patient underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). The CSF analysis was completely normal (WBCs 0/mm3, total protein 43 mg/dL, glucose 84 mg/dL), with a negative Gram stain.

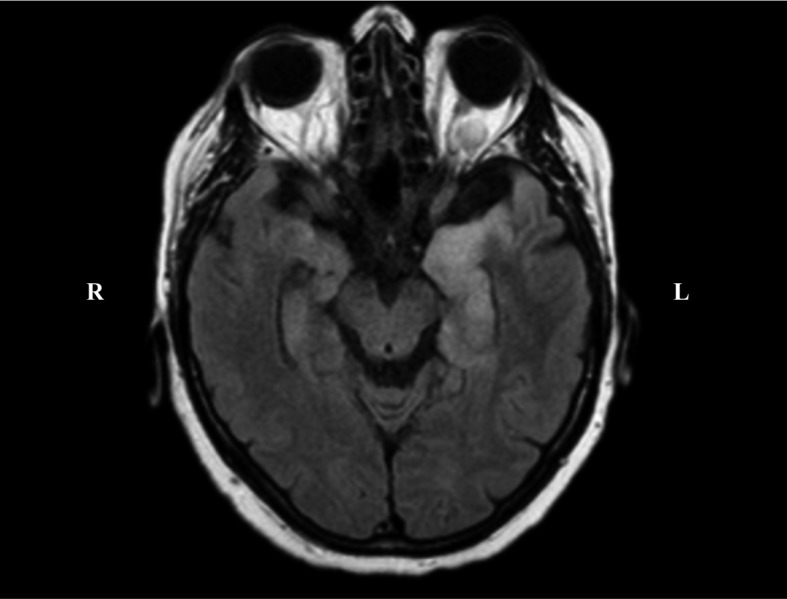

Brain MRI showed FLAIR hyperintensity of left temporo-polar, insular and temporo-mesial lobes, involving the hippocampus and, to a lesser extent, the controlateral hemisphere, without contrast enhancement (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

3T Brain MRI: Axial FLAIR sequence, hyperintensity of left temporo-polar and mesio-temporal lobe. R: right; L: left

The patient immediately received empirical antiviral therapy with Acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), together with antibiotics for pneumonia. In the following days qualitative CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) confirmed positivity for HSV-1 (2857 copies/mL). She continued intravenous antiviral therapy with acyclovir, increasing doses at 15 mg/kg/day and, after 21 days, with chronic oral prophylaxis (800 mg twice a day).

Clinical conditions gradually improved. At discharge, one month after the admission, she was alert but confused (GCS 13), without focal deficits. She died eight months later because of tumor progression.

Conclusion

We describe the case of a patient with GBM who developed HSE after RT. Even if this eventuality has been already reported (7), the present case is noteworthy as it confirms the association between HSE and GBM and further provides evidence favoring the preventive therapy with antiviral drugs in patient with GBM who undergo RT.

Antiviral prophylaxis with acyclovir has been suggested in a number of haematological malignancies to prevent HSV reactivation during the period of leucopenia (7). Acyclovir is usually well tolerated and major side effects are rare. On these grounds, considering the poor prognosis that HSE has shown in patients with GBM, a benefit/risk discussion for the utility of the introduction of acyclovir prophylaxis during RT, may be pertinent.

GBM is the most common brain tumor in adults, with a median age at diagnosis of 61 years. Histopathologic features are necrosis and endothelial proliferation, resulting in the assignment of grade IV, the highest grade in the WHO classification.

RT is still the cornerstone of GMB treatment and, together with chemotherapy, in particular Temozolomide, it improves the median survival of patients (8), although this remains extremely rare up to 5 years from the diagnosis.

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines from American Society for Radiation suggest that, following biopsy or resection, GBM patients with reasonable performance status up to 70 years of age should receive conventionally fractionated RT (eg, 60 Gy in 2- Gy fractions) with concurrent and adjuvant Temozolomide (9). However, radiotherapic treatment-induced central nervous system (CNS) toxicity remains an important issue in these patients. In particular patients could develop acute encephalopathy characterized by headache, fever, vomiting, probably linked to cerebral oedema and disruption of blood brain barrier (BBE) (10).

Moreover, even if neurological decline during treatment is more likely due to RT side effects or tumor progression (11), opportunistic infections could represent one of yet underestimated cause of deterioration. Viral infection in immunocompromised patients could be triggered by several factors: immunodepressive environment induced by the tumor ‘per se’ (2), steroid treatment and RT.

In this contest, precious recognition of concomitant infections is crucial for patients with GBM treated with RT, being the prognosis of even treatable conditions worse in immunocompromised patients (11).

Several case reports of HSE following brain RT are described in literature (5, 12, 13). HSE incidence in patients with cancer undergoing WBRT has been estimated 2000 times higher than in general population (12-13). In addition, anedoctal reports of GBM improvement after treatment with acyclovir raise the question of wheter anti-HSV therapy may play an adjunctive role in GBM treatment (14).

In our case the prompt introduction of acyclovir therapy determine neurological improvement and the patient died eight months later because of tumor progression and not for complication related to HSE.

The HSE presentation in immunocompromised patients might be tricky to be recognize especially as the gold standard for diagnosis (i.e. CSF analysis) might be misleading. In our case, indeed, CSF analysis was completely normal, without pleocytosis or evidence of inflammatory markers.

The normal cell count and poor evidence of CNS inflammatory might be possibly caused by an anergic immune comportmental cellular responce (7). The HSE diagnosis in our patient was driven by EEG and MRI scan. Bilateral asymmetric mesial temporal lobe hyperintensity in FLAIR was observed that represents a typical finding in HSE (15). EEG is highly informative for HSE, since unilateral LPDs from the temporal lobe are a key diagnostic clue for the disease (16). In our case, the presence of LPD at 0.5-0.75 Hz, immediately address the clinician to the diagnosis of HSE (Fig. 1).

Overall mortality of HSE has decreased from 70% to <20% after the introduction of antiviral treatment. Among survivors, more than 60% have moderate-severe neurological deficits and only 2-3% of patients will survive with fully normal neurological functions. The cognitive domains most frequently impaired are anterograde memory, retrograde memory, executive functions and language. All of these outcomes are worsened if treatment is delayed (4).

Current guidelines recommend treatment of HSE in adults with intravenous acyclovir 10mg/kg given every 8 hours for 2-3 weeks, even if duration of therapy is not clearly defined in the literature. Some authors suggested the need for follow-up CSF analysis prior to discontinuation of antiviral therapy (4).

Considering the challenging diagnosis of HSE in immunocompromised patients affected by GBM, due to atypical clinical findings and potential negativity of laboratory examinations, we highlight the importance of early EEG and brain MRI in supporting diagnosis. Then, considering the favourable risk-benefit balance of acyclovir profilaxys, we suggest the introduction of antiviral treatment in GBM patients at high risk of HSE develoment, such as those who underwent brain RT.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Nam TS, Choi KH, Kim MK, Cho KH. Glioblastoma mimicking herpes sim plex encephalitis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50:119–22. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.50.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangani D, Weller M, Roth P. The network of immunosuppressive pathways in glioblastoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;15(130):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gately L, McLachlan SA, Dowling A, Philip J. Life beyond a diagnosis of glioblastoma: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:447–452. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skelly MJ, Burger AA, Adekola O. Herpes simplex virus-1 encephalitis: a review of current disease management with three case reports. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2012;25(23):13–8. doi: 10.3851/IMP2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sermer DJ, Woodley JL, Thomas CA, Hedlund JA. Herpes simplex encephalitis as a complication of whole-brain radiotherapy: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;21(7):774–9. doi: 10.1159/000369527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha BA, Talmasov D, Connolly JJ. Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-1) Encephalitis Mimicking Glioblastoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2014;12(3):1392–401. doi: 10.3390/jcm3041392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berzero G, Di Stefano AL, Dehais C, Sanson M, Gaviani P, Silvani A, et al. Herpes simplex encephalitis in glioma patients: a challenging diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:374–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-307198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gzell C, Back M, Wheeler H, Bailey D, Foote M. Radiotherapy in Glioblastoma: the Past, the Present and the Future. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2017;29:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera AR, Kirkpatrick JP, Fiveash JB, Shih HA, Koay EJ, Lutz S, et al. Radiation therapy for glioblastoma: Executive summary of an American Society for Radiation Oncology Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soussain C, Ricard D, Fike JR, Mazeron JJ, Psimaras D, Delattre JY. CNS complications of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Lancet. 2009;7(374):1639–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61299-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan IL, McArthur JC, Venkatesan A, et al. Soussain C, Ricard D, Fike JR, Mazeron JJ, Psimaras D, Delattre JY. CNS complications of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Lancet. 2009 Nov 7;2012(374)(9701):1639–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61299-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graber JJ, Rosenblum MK, DeAngelis LM. Herpes simplex encephalitis in patients with cancer. J Neurooncol. 2011;105:415–21. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakraborty S, Donner M, Colan D. Fatal herpes encephalitis in a patient with small cell lung cancer following prophylactic cranial radiation--a case report with review of literature. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Söderlund J, Erhardt S, Kast RE. Acyclovir inhibition of IDO to decrease Tregs as a glioblastoma treatment adjunct. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;6(7):44. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradshaw MJ, Venkatesan A. Herpes Simplex Virus-1 Encephalitis in Adults: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13:493–508. doi: 10.1007/s13311-016-0433-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schomer DL. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. Lopes de Silva FH Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications and Related Fields; pp. 2011–1275. [Google Scholar]