Abstract

Aim:

To verify the possible advantages of 3- β-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) measurement compared to urinary assay of ketones during an intercurrent disease managed at home.

Methods:

Twelve Pediatricians were asked to enroll at least 4 patients aged 3 to 5 years, affected by an intercurrent illness and showing at least one of symptoms reliable to ketosis. Recruited patients were submitted to the simultaneous assay of 3HB in capillary blood and ketones in urine at 3 (T3) and 6 hours (T6) from the first measurement (T0). For urinary and blood ketone detection commercial tests were used.

Results:

Thirty-eight children (4.36±2.60 years old; 25 boys) were enrolled into the study. At T0 all children showed 3HB levels (1.2-3.2 mmol/L), but only 10 of them (26.3%) associated also urinary ketone bodies (2 to 4+). In response to 3 hour treatment (T3) with a glucose solution, 3HB values decreased in 19 (0,8-1,8 mmol/L) and normalized in 13 children (<0.2 mmol/L); while ketonuria disappeared in only 2 patients, it was confirmed in 8 and appeared (4+) the first time in the remaining 28 children. At T6 3HB levels fell definitively within the normal range in all children, while ketonuria was still present (2+) in 9 patients (23%). The pediatricians reported two limitations about blood 3HB dosage compared to the urinary test: the invasiveness of capillary blood collection, and the cost of supplies for finger pricking, reagent strips and reflectance meter.

Conclusions.

3HB monitor in capillary blood is more effective and clinically more useful in diagnosing and managing of an ongoing ketosis in children with a mild infective disease than ketones detection in the urine. These advantages are mitigated by the cost of 3HB measurement. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: ketone bodies, physiological ketosis, 3-beta-hydroxybutyrate, ketonemia, ketonuria

Introduction

When the body does not have enough carbohydrates available to meet its demand for energy, this begins to utilize the stored fat for energy. These fatty acids are metabolized in the liver and this metabolism induces chemical products called ketones. The ketone bodies consist of acetone, acetoacetate (AcAc), and 3-β-hydroxybutyrate (3HB) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of ketogenesis process

Mild infections in children under 5, especially those complicated by vomiting and diarrhea, commonly cause elevated levels of ketone bodies. This kind of ketosis is known as “physiological ketosis” because it is a transient condition, reliable to the low availability of glycogen in children’s liver, and because it responds promptly to glucose administration.

To diagnose ketosis Pediatricians can rely on clinical criteria (such as high fever, appetite loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dehydration signs, headache, somnolence), and on some tests to measure ketone bodies in either urine or blood. Urine test is the most used method in pediatric practice to investigate a state of ketosis even if this procedure does not detect the presence of all three ketone bodies. AcAc is the only measurable ketone since 3HB is not detectable by common urinary strips and acetone is eliminated through the breath.

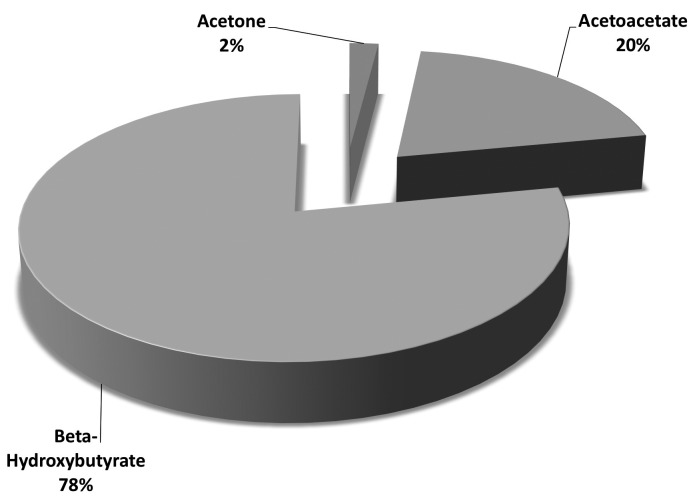

New rapid enzymatic methods have been introduced since the nineties for the quantization of 3HB levels in small blood samples (1). These systems allow to measure within a few seconds on a fingerstick blood specimen 3HB which during the ketogenesis process accounts the majority of the total ketone body pool (78%) Figure 2) (2, 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the total ketone bodies pool

Most information on advantages of 3HB dosage on ketosis management comes from the experience on ketoacidosis treatment in children with Type 1 diabetes (T1D). In response to insulin therapy, 3HB blood levels commonly decrease long before AcAc levels do in the urine. Our previous experience showed that in children with T1D at onset, monitored with 3HB measurement, it was possible to record ketoacidosis disappearance 4 to 9.5 hours earlier than in patients monitored with urine ketone bodies determination (4). Furthermore blood ketone tests help diabetic children to guide a sick day management more efficiently than urine test (5). Blood 3HB measurements may be especially valuable to prevent DKA in patients who use an insulin pump: elevations in blood 3HB levels may precede increases in urine ketones due to interrupted insulin delivery (6). 3HB measurement seems also to be able to improve clinical outcomes and enhance cost efficiency in ketoacidosis treatment (7).

There is no evidence in literature on the use of blood 3HB test in early detection of “physiological ketosis” during a mild infection in healthy children. The lack of information about this topic led us to submit to some Pediatricians a protocol in order to verify the possible advantages of capillary blood test compared to urinary assay of ketones during an intercurrent disease managed at home. The results we have obtained are shown below.

Subjects and Methods

The study involved 12 Pediatricians working in the same area of Parma municipality, a district located in northern Italy. Pediatricians were asked to enroll each-one at least 4 patients 3 to 5 years old, affected by an intercurrent illness and showing at least one of the following symptoms reliable to ketosis, in addition to fever (≥37.5°C): fruity-smelling breath, appetite loss, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, alteration of consciousness.

All Pediatricians were equipped with devices for simultaneous measurement of ketonuria and capillary blood 3HB, supplies for reagent strips, finger pricking and a reflectance meter. One-hour meeting was organized to inform pediatricians on correct management of capillary blood 3HB and urine ketone tests, and to give them more information about ketogenesis and about the criteria for early diagnosis of ketosis. Pediatricians were invited to collect and storage clinical data of tested children in a database, and to obtain the written informed consent from the parents before patients enrollment.

Once a patient was selected, this was submitted to the simultaneous assay of 3HB in capillary blood and ketones in the urine (T0). Children who did not present ketone bodies either in the blood or in the urine were excluded from the study. T0 procedures were repeated at 3 (T3) and 6 hours (T6) from the first measurement. T3 and T6 tests were performed by an experienced nurse or by a resident of the Postgraduate School of Pediatrics of Parma who was performing the internship in an outpatient clinic involved in the study. Capillary blood assay was interrupted when 3HB values have reached an amount <0.2 mmol/L. Urine tests were repeated until the urine was not appeared cleaned from ketones. The decision to stop the tests in either urine or blood was agreed with the pediatrician. Children with ketones were orally treated by a spoon of 10% dextrose solution at 5 minutes of interval. As soon as 3HB levels were normalized or ketones were undetectable in urine, the children were fed normally. Body temperature was measured by an ear thermometer.

For urinary ketone detection the same commercial test was used. After urine collection, the strip was passed through the urine, and after 15 seconds AcAc in the of urine reacted with nitroprusside producing a purple-colored complex on the test strip. The color was compared to that displayed on the color scale of the strips bottle. Test results were read as negative or 1+ to 4+.

For the quantification of 3HB levels in the blood commercial systems available in Italy were unconditionally chosen. Adopted devices measured 3HB levels on a fingerstick blood specimen (0.8 μl) within 10 seconds, and were reported to be accurate for 3HB levels from 0.1 to 8.0 mmol/L. A value <0.2 mmol/L was considered as indicative of ketosis absence; and a value ranging from 0.1 to 2.5 mmol/L was assessed as expression of mild to moderate ketosis (8,9).

At the end of the study pediatricians were asked to report an opinion on clinical utility of the 3HB test and on any found limitations.

Analysis of variance and the χ2 for the comparison of percentages were used. Linear regression analysis between fever degree and 3HB levels at T0 was calculated. Data were reported as mean±SD. P<0.05 was considered significant. No conflict of interest existed in relation to the subject matter of the present paper.

Results

Ten children dropped out of the study since they had no ketone bodies either in the blood or in the urine. Thirty-eight children (4.36±2.60 years old; n. 25 boys) were finally enrolled. All subjects showed body temperature ranging from 37.7 to 40.0°C. The symptoms reported by pediatricians to support the suspicion of a ketosis state are showed in the Figure 1. Otitis media (4/38), sinusitis (5/38), bronchitis (7/38), diarrhea (10/38), common cold (12/38) were the most frequent illnesses diagnosed by the Pediatricians at recruitment.

Measurement of ketone bodies in either urine or blood was performed in all selected children 24 hours after the first fever detection. At T0 all children showed detectable blood 3HB levels (1.2-3.2 mmol/L) meeting the criteria of a ketosis at onset, but only 10 of them (26.3%) showed also ketone bodies (2 to 4+) in the urine.

After 3 hour treatment (T3), 3HB values decreased in 19 (0,8-1,8 mmol/L) and normalized in 13 children (<0.2 mmol/L); in 6 children 3HB levels remained elevated (2.2-2.5 mmol/l). In contrast, ketonuria disappeared in only 2 patients, it was confirmed in 8 and it occurred for the first time (4+) in 28 children.

At the end of the study (T6), 3HB levels fell definitively within the normal range in all children, while ketonuria was still present (2+) in 9 (23%) patients An urine test arbitrarily performed by parents in the hours following T6 showed that ketonuria completely disappeared 2-6 hours after 3HB. All tests on capillary blood were performed at the scheduled times, while 36% of the urine tests underwent a delay ranging from 30 minutes to 2 hours since children did not urinate

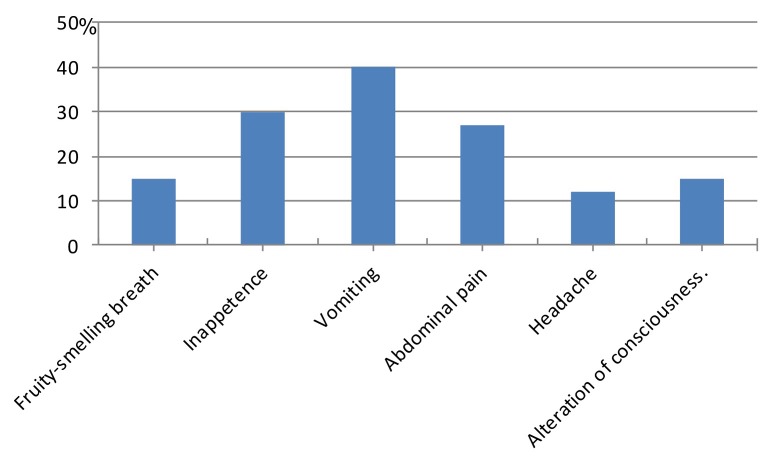

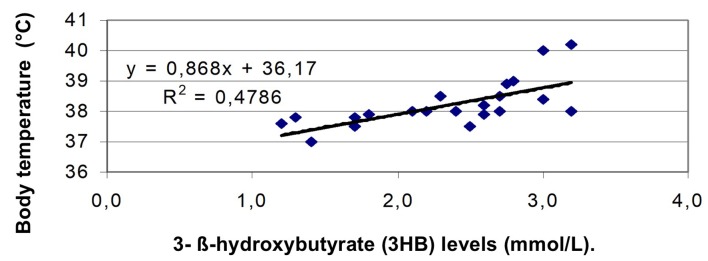

Among symptoms reported by pediatricians to support the suspicion of a state of ketosis, vomiting (40.2%) and appetite loss (29.8%) recurred more frequently (χ2=19.28 and 9.19; p<0.001) compared to the others symptoms (Figure 3). A strong correlation was found between body temperature and 3HB levels at diagnosis of ketosis (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Prevalent symptoms reported by pediatricians to support the suspicion of a ketosis state

Figure 4.

Fever is a factor increasing the levels of 3HB

Thirty-two children (84.2 %) responded promptly to glucose administration. The levels of 3 HB have begun to decrease as early as the third hour of treatment. Sixty-nine per cent of parents reported that the choice to give glucose with a spoon at short intervals proved to be a very effective tool to prevent vomiting and treatment rejection by patients. Thanks to this approach 25 children (65.8%) were able to restart normal feeding already at the end of T3.

No patient needed to be hospitalized. None of the pediatricians involved in the study had previously used 3HB measurement. All pediatricians recognized clinical utility of 3HB detection at home. However, two limitations have been reported compared to the urinary test: the invasiveness of capillary blood collection, and the cost of supplies for finger pricking, reagent strips and reflectance meter.

Discussion

We showed that 3HB levels in capillary blood is more effective and clinically more useful in diagnosing and managing an ongoing ketosis in children with a mild infective disease than ketones levels in urine. This is in agreement with previous reports on the use of 3HB both in treating ketoacidosis and in monitoring a sick day in children with T1D (3, 4, 5, 7).

The measurement of 3HB was considered as a reliable tool to recognize an incipient ketogenesis earlier than ketonuria detection (9). Ketonuria misses this goal because it provides a partial and delayed information about ketones during the ketogenesis process. Urine test assesses only AcAc and not 3HB levels, with a delay that is proportional to the interval between a bladder emptying and the next (4). Dehydration status that is frequently noticeable in a child with physiological ketosis affects the regular collection of urine specimens and may prolong the above delay. The gap in information between the two methods explains the high percentage of children we found who at T0 were already positive for 3HB but not yet for ketonuria, and of those children who at T6 continued to showing ketonuria despite 3HB levels had already came back to the normal range.

Thanks to 3HB detection, the pediatricians had the chance to start promptly the treatment established by the study protocol. Glucose solution administration stopped shortly the ongoing ketogenesis process, and children were enabled to resume within 3-6 hours of treatment the usual feeding. If the treatment had been modulated on the basis of ketonuria levels, in 23% of patients the treatment would have been prolonged beyond the planned conclusion of clinical observation, with discomfort for children and parents.

Pediatricians reported being encouraged in carrying out the 3HB test by three sentinel symptoms that are usually related to a physiological ketosis: vomiting, appetite loss and fever. Fever has proven to be a reliable indicator of ketosis at onset, and its reliability seems to grow with increasing the body temperature.

Vomiting, appetite loss and fever were reported by pediatricians more frequently than fruity-smelling breath due to acetone. Acetone is produced from AcAc and represents the least relevant ketone given its volatility, nevertheless it is often believed to be the first and the only sign of a ketotic state. The recognition of this ketone body through the breath depends on the investigator subjectivity, and not being an objective sign it could be liable to be both under- and overestimated. This remark could be retained one of the reasons why fruity-smelling breath was estimated by the pediatricians involved in the study as a unreliable sentinel symptom for ketosis.

At the end of the study, we found general satisfaction of pediatricians about blood ketone measurements compared to ketone determinations in urine. However, pediatricians reported that an important limitation on the use of blood ketone monitoring technology is the high costs compared to the determination in the urine. In fact, the cost of one test strip for ketonemia determination varies between 3 to 5 €, while the cost of one strip for ketonuria dosage ranges between 0.20 and 0.50 €, in other words ten times less. If the costs related to the puncture of the finger and to the meter of reflection are added, the gap becomes macroscopic.

Due to this difference we can speculate that it will take a lot time for blood 3HB monitoring to gain routine acceptance over urine testing in ketosis diagnosis and management. The delay could be shortened focusing on the benefits obtained with the measurement of 3HB in managing and monitoring diabetic ketoacidosis in terms of quality of care, and reduction in time and costs of treatment (4). A further impulse could result from promotional campaigns for pediatricians to update their outpatient clinics with new simplified and fast minimally invasive enzymatic methods for capillary blood measurement of some biological parameters such as glucose, cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin, and finally 3HB. We believe that these recently developed technological supports should enter without further delay in pediatric practice.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Koch DD, Feldbruegge DH. Optimized kinetic method for automated determination of beta-hydroxybutyrate. Clin Chem. 1987;33:1761–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne HA, Tuesnon KL, Hollis S, et al. Evaliation ofan Electromedical sensor for measuring blood ketone. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:500–5003. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sena SF. Beta-hydroxybutyrate: New test for ketoacidosis. Tehinically speaking, Danbury Hospital, A high level of care. July 2010, vol 4, n 8 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanelli M, Chiari G, Capuano C, et al. T. The direct measurement of 3-B-hydroxybutyrate enhances the management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children and reduces time and costs of treatment. Diab Nutr Metab. 2003;16:312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brink S, Joel D, Laffel L, et al. Sick day management in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2014;15(Suppl. 20):193–202. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umpierrez GE, Watts NB, Phillips LS. Clinical utility of beta-hydroxybutyrate determined by reflectance meter in the management of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:137–138. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanelli M, Chiari G, Capuano C. Cost effectiveness of the direct measurement of 3-beta-hydroxybutyrate in the management of diabetic ketoacidosis in children. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:959. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell GA, Kassovska-Bratinova S, Boukaftane Y, et al. Medical aspects of ketone body metabolism. Clin Invest Med. 1995;18:193–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laffel L. Ketone Bodies: a Review of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Application of Monitoring to Diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:412–426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199911/12)15:6<412::aid-dmrr72>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]