Abstract

Ractopamine hydrochloride is a commercial beta-adrenergic agonist commonly used as a dietary supplement in cattle production for improved feed efficiency and growth promotion. Currently, regulatory target tissues (as approved in the New Animal Drug Application with Food and Drug Administration) for ractopamine residue testing are muscle and liver. However, other tissues have recently been subjected to testing in some export markets for U.S. beef, a clear disregard for scientific maximum residue limits associated with specific tissues. The overall goal of this study was to develop and validate an LC-MS/MS assay to determine whether detectable and quantifiable levels of ractopamine in digestive tract-derived edible offal items (i.e., abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) of cattle resulted from tissue residues or residual ingesta contamination of exposed surfaces of tissues (rinsates). Tissue samples and corresponding rinsates from 10 animals were analyzed for parent and total ractopamine (tissue samples only). The lower limit of quantitation was between 0.03 and 0.66 ppb depending on the tissue type, and all tissue and rinsate samples tested had quantifiable concentrations of ractopamine. The highest concentrations of tissue-specific ractopamine metabolism (represented by higher total vs. parent ractopamine levels) were observed in liver and small intestine. Contamination from residual ingesta (represented by detectable ractopamine in rinsate samples) was only detected in small intestine, with a measured mean concentration of 19.72 ppb (±12.24 ppb). Taken together, these results underscore the importance of the production process and suggest that improvements may be needed to reduce the likelihood of contamination from residual ractopamine in digestive tract-derived edible offal tissues for market.

Keywords: beef, export, offal tissue, ractopamine, residue

INTRODUCTION

Beta-adrenergic agonists, otherwise known as beta-agonists, are commonly used in the livestock industry for growth promotion (Anderson et al., 2004; Kootstra et al., 2005). One type of beta-agonist, ractopamine hydrochloride (RH), is a phenethanolamine compound, similar to endogenous catecholamines, and has been approved for use as a growth promotant in food-animal production in several countries (Johnson et al., 2013). These synthetic compounds bind to G protein-coupled beta-receptors on differing cell surfaces (e.g., muscle and fat) in livestock (Mersmann, 1998; Johnson, 2014), increasing muscle mass via hypertrophy while also decreasing fat accretion/lipid synthesis. Because beta-agonists such as ractopamine increase protein synthesis while decreasing degradation of protein and production of fat (Mersmann, 1998), they are sometimes referred to as repartitioning agents because they are capable of altering utilization of nutrients during animal metabolism (Anderson et al., 2004). Optaflexx (RH; Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN) is a commercial beta-adrenergic agonist approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a dietary supplement in cattle production for increased rate of weight gain, improved feed efficiency, and increased carcass leanness in cattle fed in confinement for slaughter during the last 28 to 42 d on feed.

As the world population continues to increase, it is becoming increasingly important to produce more nutritionally rich food with fewer resources (KC et al., 2018). In fact, it has been stated that sustainably feeding the next generation is one of the most crucial challenges of the 21st century (KC et al., 2018). Because beta-agonists have the ability to stimulate skeletal muscle growth without increasing hormone levels, cattle and swine producers have widely adopted this technology to improve meat yield (Centner et al., 2014). In 2000, use of ractopamine for the purpose of increasing weight gain and carcass leanness and promoting better feed efficiency in swine was approved by the U.S. FDA. Since then, it has been used in livestock production in over 20 countries, but concerns remain regarding potential human health risks (Centner et al., 2014). Furthermore, because of multiple geopolitical issues, the European Union, China, and Russia have restricted and even banned use of ractopamine, as well as the importation of meat with detectable levels of ractopamine (Bories et al. 2009; Centner et al., 2014). The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) is an international scientific authority that assesses safety of residues of veterinary drugs in food (Centner et al., 2014). The Codex Alimentarius Commission then utilizes these assessments and recommendations to adopt maximum residue limits (MRLs) as international standards (Centner et al., 2014). The JECFA has reviewed residue safety data several times (JECFA reviews in 1993, 2004, 2006, and 2010) and recommended an acceptable daily intake (ADI) for consumers and MRLs for specific edible tissues. MRLs for ractopamine were, thus, developed through this lengthy and scientifically rigorous process for muscle, liver, kidney, and fat tissues and were adopted in 2012 (AOAC, 2015). No such limits exist for digestive tract-derived edible offal tissues or other edible tissues such as tendons and bones. The absence of scientifically substantiated MRLs for these offal tissues has created regulatory and trade confusion in export markets where these tissues are more frequently imported and consumed (Centner et al., 2014).

Currently, global standards for ractopamine detection are based on analysis of intact ractopamine (“parent”) related to the feed additive itself. In 2012, a candidate method recognized by the Expert Review Panel of AOAC International (AOAC, 2015) was developed and validated for quantitation of ractopamine in bovine, swine, and turkey tissues using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (Burnett et al. 2012). Nine separate laboratory groups were then tasked with analyzing bovine muscle, bovine liver, swine muscle, swine liver, and turkey muscle to quantify ractopamine utilizing this method (Ulrey et al., 2013). Based upon AOAC benchmarks, this method was deemed acceptable due to reproducibility among these laboratories and tissues (Ulrey et al., 2013). The method received Final Action status at the end of 2012 and is a major testing practice utilized globally for ractopamine quantitation (Ulrey et al., 2013).

Alternative testing methods approved by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for detection of parent ractopamine include the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit developed by Randox Food Diagnostics (Randox Laboratories Ltd.; Crumlin, United Kingdom) (Randox, 2018). However, cattle have been shown to metabolize RH into 4 major metabolites—2 ring A monoglucuronides, 1 ring B monoglucuronide, and 1 diglucuronide (Elanco, 2003; Tang et al., 2016). These glucuronide metabolites can be disrupted/deconjugated by beta-glucuronidase (Tang et al., 2016), releasing the ractopamine for detection. Thus, enzymatic treatment of the tissue enables detection of the total ractopamine pool, which represents the parent ractopamine plus the glucuronide metabolites. It is important to note that, while the enzymatic hydrolysis increases the sensitivity to detect ractopamine in tissues, the total ractopamine pool is not appropriate for direct comparison to MRLs as these limits were established based on detection of the marker residue (parent ractopamine; Burnett et al., 2012).

The current study fills an important knowledge gap in our understanding of total ractopamine residues in offal tissues and the potential for contamination with the drug to occur during processing due to the presence of residual ingestate in digestive tract offal tissues. Here, we present a validated LC-MS/MS assay for quantification of parent and total ractopamine in multiple tissue types, including liver, muscle, abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum and evaluate the hypothesis that residual ingestate could contribute to the detection of ractopamine in these offal tissues. Results of this work improve our understanding of the levels of ractopamine residues in beef tissues that are reflective of global eating habits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Collection and Storage

Individual heifers (N = 10), originating from a commercial feedlot producer, which fed ractopamine HCl (24.6 g/ton for 32 d) according to U.S. label direction (fed right up to loading; <4 h between loading to stun), were identified during the slaughter process. Samples from the digestive tract (abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) as well as muscle and liver were collected following complete commercial processing in a large-scale harvest facility. Samples (minimum of 100 g tissue) were placed into sterile sample bags, placed on ice, and transported to Colorado State University (Fort Collins, CO) for processing and analysis. Additionally, 5 known ractopamine HCl-free tissue samples (one of each for muscle, liver, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) were collected and then pooled to be used as a matrix background for each tissue type.

Materials

Ractopamine HCl certified reference standard (1.0 mg/mL) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Ractopamine-d6 HCl internal standard (IS; 1 mg with exact weight packaging) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada). β-Glucuronidase (from Helix pomatia, type HP-d, aqueous solution, ≥100,000 units/mL) and sodium acetate (NaOAc) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonium formate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, water (LC-MS grade), methanol (LC-MS grade), formic acid (Pierce LC-MS grade), and acetonitrile (LC-MS grade) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Sample Preparation

One hundred to 150 g of digestive tract tissue (abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) was weighed into a sterile plastic zip bag and 1-mL LC-MS-methanol per g of tissue was added to generate the rinsate samples. The tissue was submerged, shaken, and massaged for 1 min to release any remaining ingesta from the external tissue surface. Tissue was then carefully transferred to a clean cutting surface and liquid (rinsate) was decanted into a clean preweighed 250-mL conical tube. The rinsate was frozen for at least 3 h at −80 °C and then lyophilized for 24–48 h. The rinsed tissue was chopped into small (~ 3 × 3 cm) pieces, flash frozen in liquid N2, and homogenized using a Robot Coupe Blixer V4 (Robot Coupe USA, Jackson, MS). Muscle and liver tissue were homogenized in the same way without rinsing. Two subsamples (5 ± 0.5 g) of each tissue type homogenate were obtained and placed into separate 50-mL conical tubes. Tissue homogenate and lyophilized rinsate were stored at −80 °C until extraction. Rinsate solids were resuspended at 1 mL per 10 mg and tissue homogenate at 4 mL per 1 g with methanol containing 25 ng/mL of the IS. Samples were sonicated for 30 min, vortexed at 4 °C for 10 min, and incubated for 30 min at −80 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min to remove remaining solids. The supernatant was transferred and 2 aliquots of 1 mL were collected in microcentrifuge tubes for analysis (the remaining supernatant was stored at −80 °C). The 1-mL aliquots were centrifuged again at 4 °C for 10 min at 12,000 × g and the supernatant was transferred to glass vials. One aliquot was analyzed directly for parent ractopamine and the other was processed as described below for total ractopamine analysis.

The 1-mL supernatant aliquot from the extraction above was evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. The sample was resuspended in 200 μL of 25 mM NaOAc buffer (pH 5.2). Four milliliter β-glucuronidase was added and the sample was mixed thoroughly by gentle vortex. The sample was incubated at 65 °C for 2 h in a sand bath. Four hundred microliter of methanol were added and the sample was mixed thoroughly by gentle vortex, followed by centrifugation at approximately 2025 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was carefully removed and placed into a clean glass vial for LC-MS analysis. Recovery samples (control tissues) were fortified prior to extraction with ractopamine standard equal to 5, 10, and 20 ppb and allowed to sit undisturbed for 15–20 min on ice before proceeding with extraction as described above.

UPLC-MS Analysis

Samples were analyzed on a Synapt G2-Si Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation) with a standard flow ESI source coupled to a Waters Acquity I-Class ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) equipped with a reverse phase 1.0- × 50-mm Waters Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 µm particles). The UPLC was operated at 0.400 mL/min and the column temperature was thermostatically controlled at 50 °C using the column heater onboard the UPLC stack. Buffer A was water (Fisher Scientific, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [LC-MS] Grade) with 2 mM ammonium formate, buffer B was acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific, LC-MS Grade) with 0.1% formic acid (Pierce, LC-MS Grade). One microliter of sample was directly injected onto the column. The UPLC gradient is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) gradient

| Time (min) | %A | %B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 99.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.2 | 99.0 | 1.0 |

| 2.2 | 70.0 | 30.0 |

| 3 | 1.0 | 99.0 |

| 4.25 | 1.0 | 99.0 |

| 4.5 | 99.0 | 1.0 |

| 6.5 | 99.0 | 1.0 |

Data were acquired at 10 Hz across the mass range of 50–1000 m/z. The collisional energy (CE) of each identified transition was optimized in the trap cell of the TriWave (302 ➔ 164.106: CE = 11, 302 ➔ 284.1627: CE = 9). The transfer cell CE was turned off and no mobility separation was conducted to maintain ion transmission efficiency. Targeted enhancement was turned on and configured to target the product ion of interest. The final method consisted of 2 MS/MS functions: the first targeted ractopamine (302 m/z ➔ 164.106, CE = 11, Targeted Enhancement = 164.106), and the second targeted the IS, ractopamine-d6 (308 m/z ➔ 168.17 m/z, CE = 11, Targeted Enhancement = 168.17 m/z). For identification confirmation, 284.1627 m/z was utilized. These transitions agree with established methods in the literature for detection of ractopamine by LC-MS/MS (Burnett et al., 2012; Tang et al., 2016). The spectra were LockMass corrected using leu-enkephalin (Sigma Aldrich) to provide accurate mass data.

Peak picking and integration were performed using Quanlynx software (V 4.2 SCN983, Waters Corporation). Peak areas for each sample (included standard curve) were normalized to the peak area of the IS in that sample. Quantification of samples was performed using linear regression (no weighting) against a matrix matched external standard curve. Separate standard curves were generated for each matrix type (muscle, liver, abomasum, omasum, reticulum, small intestine, and rinsate) from control tissue fortified with ractopamine standard postextraction (ranging from 0.1 to 50 ng/mL). Accuracy and precision were determined for each tissue type and the pooled rinsates based on triplicate injections of the fortified control matrix at ractopamine concentrations of 1, 5, and 25 ng/mL. The limit of detection was calculated as 3 × SD of the blank signal/slope of the linear regression curve and the limit of quantitation was calculated as 10 × SD of the blank signal/slope of the linear regression curve.

RESULTS

Assay Demonstrates Effective and Reproducible Quantification of Ractopamine Across Multiple Tissue Types

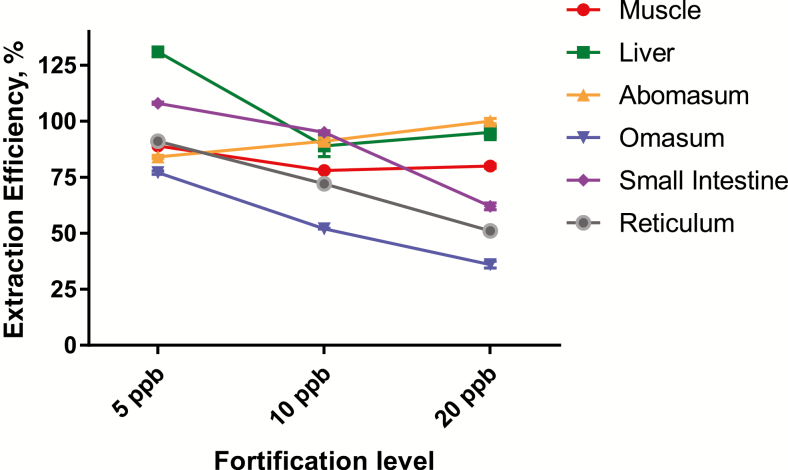

Extraction efficiency was evaluated by fortification of control tissue samples with 5, 10, or 20 ppb of ractopamine before extraction. Measured recoveries ranged from 36% to 131%, with the majority of test samples >75% (% recovery = measured/fortified × 100; Figure 1). These results indicate that the simple extraction protocol utilized in this study was effective and reproducible across the range of concentrations detected in the samples. All extractions were performed using a stable isotope labeled IS.

Figure 1.

Extraction efficiency of ractopamine across all tissue types. Results represent the average % extraction efficiency (with SDs) of 3 control samples fortified with 5, 10, or 20 ppb ractopamine.

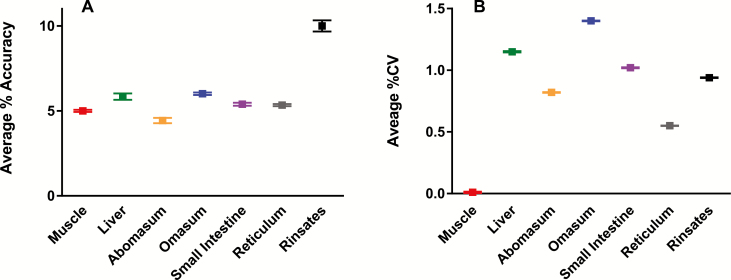

Accuracy and precision of the assay were determined by evaluation of control tissue samples fortified after extraction in triplicate at ractopamine concentrations of 1, 5, and 25 ng/mL. The average % CV of ractopamine detection for each tissue type and the rinsate (evaluated as a pool of rinsates from abomasum, omasum, reticulum, and small intestine) were all less than 2%. Average % accuracy for ractopamine quantitation for each tissue type were all better than 6% and was 10% for the pooled rinsates (% CV = [SD of measured values/average of measure values] × 100; % accuracy = [average of measured values—fortification level/fortification level] × 100; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Accuracy (A) and precision (B) of ractopamine assay across all tissue types and rinsates. Values represent the average % CV and % accuracy (with SDs) for triplicate measurement of control matrix samples fortified with ractopamine at 1, 5, and 25 ppb.

Limits of detection and quantitation were determined for all tissue types (Table 2) and were comparable with published methods for muscle and liver and well below the current Codex Alimentarius Commission MRL of 10 ppb for muscle (Codex, 2015). Importantly, this sensitivity was achieved using a very simple, high throughput extraction protocol that does not include a solid phase extraction step as is common in most published protocols for ractopamine detection (Burnett et al., 2012; Ulrey et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ)

| Tissue Type | LOD (ppb) | LOQ (ppb) |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Abomasum | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| Liver | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Omasum | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Small intestine | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Reticulum | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Rinsate | 0.02 | 0.06 |

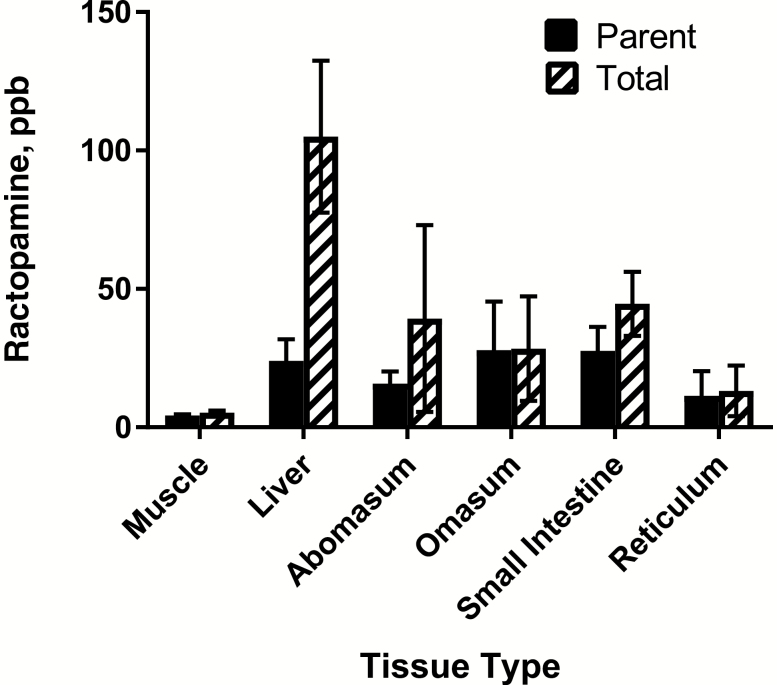

Parent and Total Ractopamine Varies Across Tissue Types

Both parent and total ractopamine were measured in muscle, liver, abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum from 10 animals (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Dataset). Total ractopamine concentrations represent parent ractopamine plus ractopamine metabolites. As expected, the highest concentration of ractopamine metabolites were measured in liver tissue (80.93 ± 39.8 ppb; represented by the difference between the total and parent ractopamine concentration). However, ractopamine metabolites were also detected in abomasum (23.52 ± 47.6 ppb) and small intestine (16.97 ± 20.2; Figure 3; Supplementary Table S1). All of the digestive tract offal tissues contained higher concentrations of ractopamine than muscle (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S1). As an example, the total ractopamine concentration in muscle samples was 5.37 ± 0.95 ppb, while the total ractopamine values of other tissues ranged from 13.19 ± 12.7 ppb (reticulum) to 105.04 ± 38.4 ppb (liver) (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Parent and total ractopamine levels in tissue samples. Values represent the average of 10 animals (with SDs).

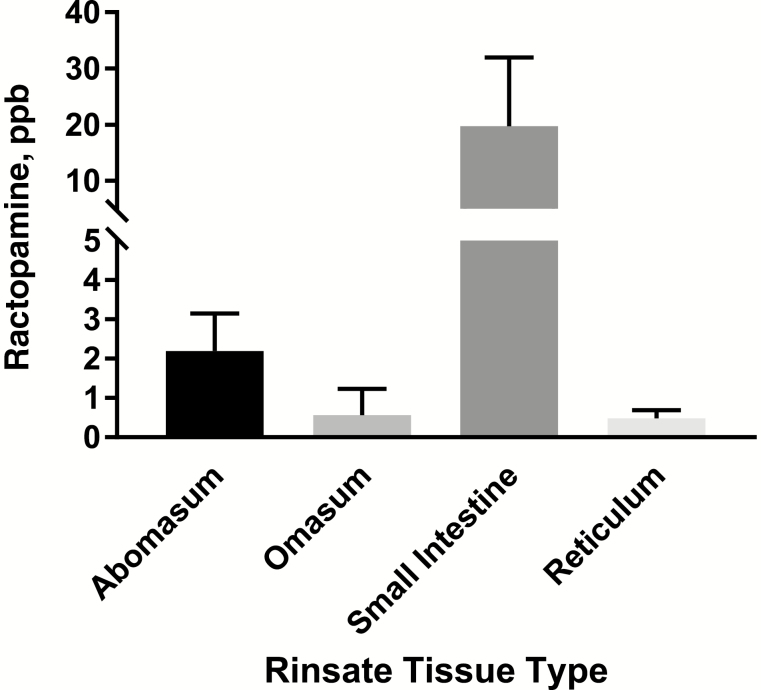

Residual Ingesta may Contribute to Ractopamine in Some Offal Tissues

To determine if residual ingesta in the digestive tract could be contributing to measured ractopamine levels in tissue homogenates, rinsate samples were generated by gently massaging the tissue samples in methanol to release any residual ingesta into solution. This rinsate sample was then extracted and assayed for parent ractopamine. The rinsate from the small intestine contained an average parent ractopamine concentration of 19.71 ± 12.2 ppb, whereas all other digestive tissue rinsates contained <2.19 ± 1 ppb of ractopamine (Figure 4; Supplementary Table S2). This suggests that commercial processing procedures were insufficient to remove all residual ingesta from digestive tissues and, in particular, from the small intestine.

Figure 4.

Measured parent ractopamine in rinsates of digestive tissues. Values represent average ppb of 10 animals (with SDs).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, this study represents the first published report of ractopamine residues in/on digestive edible offal tissues from beef cattle. Results demonstrate the development and validation of a sensitive and accurate analytical method for quantitation of ractopamine in multiple tissues with importance relevant to global eating habits. Furthermore, the results demonstrate potential for substantial contamination from residual ingesta on tissues (specifically digestive tissues) collected at commercial beef harvest facilities even after commercial processing procedures. This finding has important implications for harvest facilities to ensure that processing procedures are sufficient to reduce or eliminate contamination from residual ingesta.

These results are of even further significance when considering zero-tolerance trade policies—albeit for off-target tissues—for ractopamine residues that have been implemented in markets including China, the EU, and Russia. These countries will refuse or destroy imported product with any detectable concentration of ractopamine upon arrival (Centner et al., 2014). Importantly, “all” of the offal tissues analyzed in this study (abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) contained detectable levels of ractopamine.

Currently, the U.S. meat industry relies heavily on export markets, exporting over 120,000 metric tons of beef to Hong Kong, alone, in 2018, valued at $966 million (USMEF, 2018). As trade negotiations continue, it will be of critical importance for beef producers to keep in mind that different countries/foreign trading blocs have different policies in regards to ractopamine residues. While the tissues and rinsates investigated in this study were off-target items, it will continue to be important for beef producers and commercial beef harvest facilities to develop methods for reducing ractopamine residues in edible offal products meant for export to avoid refusal of products that have no regulatory MRL. Moreover, continued research must be conducted to evaluate how these offal tissues could be contaminated with ractopamine upon beef cattle harvest and fabrication and to explore practical measures to prevent such contamination.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Journal of Animal Science online.

Supplementary Table 1. Mean parent and total ractopamine residue concentrations (ppb) in 6 tissue types (muscle, liver, abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) from cattle fed RH after a practical 12-hour (0 day) withdrawal. Total ratopamine metabolites were calculated as the difference between the total ractopamine and parent ractopamine measurements with propagation of the standard deviations.

Supplementary Table 2. Mean parent concentrations (ppb) from rinsates from 4 different tissue types (abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) from cattle fed RH after a practical 12-hour (0 day) withdrawal.

Supplementary data set. Peak areas and standard curve calculations for 6 tissue types (muscle, liver, abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum) and rinsates for abomasum, omasum, small intestine, and reticulum). Data set includes raw peak areas and internal standard normalization for all samples and standard curve points.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Elanco Animal Health for financial support and technical assistance.

Conflict of interest statement. T.J.B. and J.S. were employees of Elanco Animal Health, Inc. during the conduct of this study.

LITERATURE CITED

- Anderson D. B., Moody D. E., and Hancock D. L.. . 2004. Beta adrenergic agonists. In: Pond W. G. and Bell A. W., editors. Encyclopedia of animal science. New York (NY): Marcel Dekker, Inc, p. 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC 2015. Setting global standards. http://www.aoac.org/aoac_prod_imis/AOAC/AOAC_Member/AOACACF/AOACOCF/AOACA14.aspx Accessed April 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bories G., Brantom P., de Barbera J. B., Chesson A., Cocconcelli P. S., Debski B., Dierick N., Gropp J., Halle I., Hogstrand C., . et al. 2009. Safety evaluation of ractopamine. EFSA J. 1041:1–52. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett T. J., Rodewald J. M., Brunelle S. L., Neeley M., Wallace M., Connolly P., and Coleman M. R.. . 2012. Determination and confirmation of parent and total ractopamine in bovine, swine, and turkey tissues by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry: First Action 2011.23. J. AOAC Int. 95:1235–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centner T. J., Alvey J. C., and Stelzleni A. M.. . 2014. Beta agonists in livestock feed: status, health concerns, and international trade. J. Anim. Sci. 92:4234–4240. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-7932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codex 2015. Maximum residue limits (MRLs) and risk management recommendations (RMRs) for residues of veterinary drugs in foods. In: 38th Session of the Codex Alimentarius Commission. Geneva, Switzerland, July, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Elanco 2003. Elanco Animal Health—Freedom of Information Summary: Original New Animal Drug Application—NADA 141–221—Ractopamine hydrochloride. https://www.fda.gov.tw/upload/133/02%20US%20FDA%20(evaluation%20of%20ractopamine%20for%20beef).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J. 2014. Mechanism of action of beta adrenergic agonists and potential residue issues. Kearney, MO: American Meat Science Association. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. J., Ribeiro F. R. B., and Beckett J. L.. . 2013. Application of growth technologies in enhancing food security and sustainability. Anim. Front. 3:8–13. doi: 10.2527/af.2013-0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- KC K. B., Dias G. M., Veeramani A., Swanton C. J., Fraser D., Steinke D., Lee E., Wittman H., Farber J. M., Dunfield K., . et al. 2018. When too much isn’t enough: Does current food production meet global nutritional needs? PLoS One. 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kootstra P. R., Kuijpers C. J. P. F., Wubs K. L., van Doorn D., Sterk S. S., van Ginkel L. A., and Stephany R. W.. . 2005. The analysis of beta-agonists in bovine muscle using molecular imprinted polymers with ion trap LCMS screening. Anal. Chim. Acta. 529:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.09.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mersmann H. J. 1998. Overview of the effects of beta-adrenergic receptor agonists on animal growth including mechanisms of action. J. Anim. Sci. 76:160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randox 2018. Ractopamine detection in meat. https://www.randox.com/ractopamine-detection-meat/ Accessed April 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Liang X., Zhang K., Zhao Q., Meng Q., and Zhang J.. . 2016. Residues of ractopamine and identification of its glucuronide metabolites in plasma, urine, and tissues of cattle. J. Anal. Toxicol. 40:738–743. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkw072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrey W. D., Burnett T. J., Brunelle S. L., Lombardi K. R., and Coleman M. R.. . 2013. Determination and confirmation of parent and total ractopamine in bovine, swine, and turkey tissues by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry: Final Action 2011.23. J. AOAC Int. 96:917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USMEF 2018. United States Meat Export Federation: total U.S. beef exports: 2009–2018 (including variety meat). https://www.usmef.org/downloads/Beef-2009-to-2018.pdf Accessed April 17, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.