Abstract

Transparent wood (TW) is an emerging optical material combining high optical transmittance and haze for structural applications. Unlike nonscattering absorbing media, the thickness dependence of light transmittance for TW is complicated because optical losses are also related to increased photon path length from multiple scattering. In the present study, starting from photon diffusion equation, it is found that the angle-integrated total light transmittance of TW has an exponentially decaying dependence on sample thickness. The expression reveals an attenuation coefficient which depends not only on the absorption coefficient but also on the diffusion coefficient. The total transmittance and thickness were measured for a range of TW samples, from both acetylated and nonacetylated balsa wood templates, and were fitted according to the derived relationship. The fitting gives a lower attenuation coefficient for the acetylated TW compared to the nonacetylated one. The lower attenuation coefficient for the acetylated TW is attributed to its lower scattering coefficient or correspondingly lower haze. The attenuation constant resulted from our model hence can serve as a singular material parameter that facilitates cross-comparison of different sample types, at even different thicknesses, when total optical transmittance is concerned. The model was verified with two other TWs (ash and birch) and is in general applicable to other scattering media.

Keywords: transparent wood, transmittance, photon diffusion equation, attenuation coefficient, anisotropic scattering

Introduction

Transparent wood (TW), combining good mechanical performance with high optical transmittance, is a new material for applications in light-transmitting buildings and smart windows.1 Preparation of TW is normally based on delignification followed by infiltration of a refractive-index-matched polymer.2,3 Following such a process, the microscopic and hierarchical structure of the wood4,5 is preserved, and hence the mechanical and optical properties of TW are anisotropic.1−3,6,7

Since its initial realization,7 there have been rapid developments on improved TW preparation techniques and TW potential applications. Related research activities include improved optical properties via surface modification of delignified wood templates,1 tuning mechanical properties by lamination,8 novel preparation of TW with larger thickness,9,10 endowing TW with multiple functionalities (luminescent TW doped with quantum dots,8,11 wood laser embedded with luminescent dye,12 magnetic wood,13 thermal energy storage TW,14 and heat shielding TW15), and integration of TW to construction elements or optoelectronic devices (smart windows16 and solar cells17).

Better understanding of optical properties of TW is essential for further development of this class of optically functional materials. In many applications, for example energy-saving buildings and solar cells,6,17,18 the total light transmittance is an important property. Fundamentally, light transmittance through a TW is highly influenced by light scattering because of the refractive index mismatch between the wood template and the infiltrating polymer, as well as the presence of air gaps between template and polymer.2 It was observed that surface modification1 and lamination8 of delignified wood template lamellae can be used to tune light scattering/haze and also transmittance. Previous work focused mostly on either total transmittance at particular TW thicknesses,2,10 or angular distribution of light transmitted through TW at various thicknesses.19 A quantitative relationship between total transmittance and sample thickness, however, is rarely studied.

For nonscattering media, the Beer–Lambert Law (BL, or absorption law) is well recognized to describe the relationship between transmittance and sample thickness as T = exp(−μad), where T is the transmittance, d is the sample thickness, and μa is the absorption coefficient. This expression is based on the random nature of stochastic light absorption, characterized by the rate constant μa. For scattering materials, for example, animal tissue20 and TW, BL cannot be applied directly because the actual optical path length (OPL) for light shows a broad distribution due to scattering.21 Many approaches have been proposed for modified BL for scattering media to characterize absorption.22−27 However, most of them do not describe “angle-integrated transmittance” for the scattering materials or models. The classical diffusion equation has been applied to describe photon transport inside materials. Durian et al. found that the diffusion coefficient depends on the absorption in a scattering material.28 Donner et al. investigated the light diffusion in multilayered translucent materials based on a multipole diffusion approximation.29 Work by Elaloufi et al. described the application of the photon diffusion equation to a scattering and absorbing material.30 For anisotropic scattering materials, Johnson et al. investigated the light transport in chemically etched gallium phosphide wafers.31 These results show the potential use of the diffusion equation to describe light propagation in highly anisotropic scattering materials such as TW.

In this work, using the anisotropic photon diffusion equation, we suggest a relationship between angle-integrated total transmittance and thickness for TW, in the form of an exponential decay expression. Total transmittances for TW samples in a range of thicknesses were measured. The expression was used to fit measured transmittances with respect to the sample thickness. The TW materials were based on wood templates subjected to two different chemical treatments. An attenuation coefficient of 1.67 ± 0.08 cm–1 was obtained for nonacetylated TW and 0.64 ± 0.01 cm–1 for acetylated TW at a wavelength of 550 nm. The results prove that, in addition to the absorption coefficient, the diffusion coefficient (scattering) also plays an important role for total light transmittance. These two samples have essentially the similar light-absorbing lignin content and differ in scattering strength.

Haze measurements were carried out to verify this conclusion. The nonacetylated TW indeed exhibits higher haze, because of microgaps between the treated wood templates and the infiltrated polymer.1 Based on the proposed relationship as well as the attenuation coefficient obtained from fitting, one can predict transmittance of TW as a function of thickness. The attenuation coefficient becomes important in comparing light-transmitting qualities of TW samples based on different wood species or chemical treatments. The model is in general valid to predict transmittance for other types of anisotropic scattering materials.

Experimental Section

Fabrication of Transparent Wood

In the present work, acetylated TW and nonacetylated TW with different thicknesses were fabricated on the basis of our previous methods with minor modification.1,2

The preparation of acetylated TW includes four main steps: delignification, wood acetylation, bleach and infiltration of prepolymerized methyl methacrylate (PMMA). First, balsa wood (density = 120 kg/m3, purchased from Wentzels Co. Ltd., Sweden) samples were cut from the longitudinal section of the tree with the different thicknesses (0.24, 0.32, 0.42, 0.51, and 0.65 cm). Samples with dimension of 20 × 20 mm were delignified at 80 °C using 1 wt % of sodium chlorite (NaClO2, Sigma-Aldrich) in an acetate buffer solution (pH 4.6) for 6 h (12 h for 0.51 and 0.65 cm, to make sure all the templates have a similar composition). After that, the delignified samples were washed with deionized water, ethanol, and finally acetone. At the second step, the delignified template was treated with acetic anhydride (Sigma-Aldrich) in the solvent of N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Sigma-Aldrich) with pyridine (Sigma-Aldrich) as the catalyst. The ratio of wood template (g):acetate anhydride (mL):pyridine (mL):NMP (mL) is 2:7:6:100. The reaction was performed under 80 °C for 6 h. Third, the acetylated wood was treated with NaClO2 again until white and washed with deionized water, ethanol, and finally acetone. Finally, the delignified wood templates were then infiltrated with PMMA solution for 4 h (12 h for 0.51 and 0.65 cm) under vacuum and were heating in an oven at 45 °C for 24 h, and then 70 °C for 6 h to complete the polymerization process. MMA prepolymerization reaction was performed in a round-bottom flask at 75 °C for 15 min with initiator (2-methylpropionitrile, 0.3 wt %, AIBN, Sigma-Aldrich) and terminated with ice–water bath. The infiltrated wood templates were covered with two glass slides on both sides and packaged in the aluminum foil before heating in an oven. Acetylated TW was obtained after the polymerization process.

Nonacetylated TW (balsa, thickness: 0.11, 0.21, 0.25, 0.31, 0.43, and 0.46 cm) preparation is similar to acetylated TW but with only two main steps: delignification and infiltration of PMMA. The present sample thickness range is similar as in previous TW literature, and primarily limited by mass transport challenges during delignification and monomer infiltration.

Characterization

The cross sections of the samples were observed with a Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan) operating at an acceleration voltage of 1 kV.

Angle-integrated total transmittance and haze of the samples were measured with an integrating sphere according to ASTM D1003 “Standard Test Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics”.32 The sample was set in front of an input port of the integrating sphere, a light source (quartz tungsten halogen light source, model 66181 from Oriel Instruments) with strong, stable output mainly in the visible and NIR region was applied as the incident beam. The output light was collected through an optical fiber connected to the output port of integrating sphere. Each sample was measured 3 times; and the results show statistically averaged values with <1% error.

Diffusion Equation for Transparent Wood

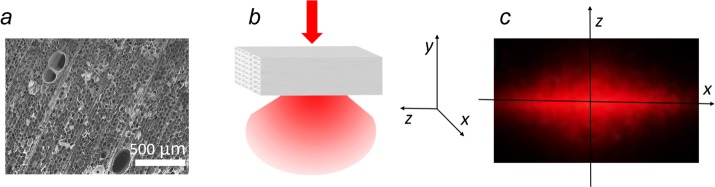

For photon transport in a scattering material, the diffusion equation was modified. Transparent wood is an anisotropic, highly scattering material. When a photon is transported inside the material, scattering could occur at the interfaces between the wood cell wall and the infiltrated polymer and from cell wall pores. Figure 1a shows a cross-section of the original balsa wood, where the average diameter of tubular wood fiber cells is around 30 μm. Note the larger vessel elements, which have much larger diameter. The diffusion model can be applied when photons lose directionality and the transport process becomes stochastic. For TW, an incoming photon initially travels some distance inside the scattering media, but later the initial direction is lost because of scattering (Figure 1b). Therefore, the photon diffusion equation can describe photon transport inside TW. In addition, unlike transparent paper with random organized fibers, transparent wood is an anisotropic scattering material. When the incoming light beam is perpendicular to the wood fiber direction, less scattering happens along the wood fibers (z-direction) than perpendicular to fiber direction (x–y plane, see Figure 1c). At least two different diffusion coefficients should be considered: Dxy (in the plane perpendicular to the fiber direction) and Dz (along the fiber direction). The general diffusion equation for transparent wood can be written as follows

| 1 |

where p(x, y, z, t) is the photon position in TW at time t, Dxy, and Dz are the diffusion coefficients perpendicular and parallel to the wood fibers, μ is the isotropic absorption coefficient for TW, c is the speed of light in TW samples. The equation describes the particle probability density (concentration) evolvement as a function of time. The scheme is shown in Figure 1b. In the figure, the incoming beam (which is along y-axis) is perpendicular to the wood fibers (z-axis), and x-axis is in the same sample plane as z-axis, but perpendicular both to the wood fibers and the input beam. When a photon enters the TW sample, it will be scattered until it leaves the medium or is absorbed (disregarding ballistic photons). Figure 1c shows the scattering pattern of a red laser beam in the x–z detection plane behind the sample of nonacetylated TW with thickness of 0.31 cm. The scattering pattern shows that the scattering strengths parallel and perpendicular to the wood fibers are different, as discussed above.

Figure 1.

(a) SEM image of the cross-section of balsa wood template, (b) Schematic image illustrating light scattering in TW, (c) light scattering pattern for a beam that has passed through the TW sample.

The time-dependent solution for p(x, y, z, t) can be obtained, for instance by using a method of images for a point source.31 Because we are interested in the total transmittance, it can be integrated along x- and z-directions and over the time at y = d, where d is the sample thickness. The resulting p(d) is regarded as a fraction of transmitted photons for a unity point source. The total transmittance of the TW as a percentage value of incoming light is described as follows:33,34

|

2 |

Equation 2 shows that the total transmittance (Ttotal) of TW has an exponentially decaying dependence on sample thickness.

We refer to the constant  in eq 2 as the attenuation coefficient. It depends

not only on the absorption coefficient μ but also on the anisotropic

diffusion coefficient. In this study, it is the exponential thickness

dependence of total transmittance in eq 2 that is used to understand and predict transmittance

of TWs. The attenuation coefficient α is determined through

fitting of experimentally measured transmittance data. The material-specific

constant α contains the effects of both light absorption and

diffusion (where the diffusion coefficient D ∼

(3(μs + μ))−1 and μs refers to scattering coefficient).

Quantitative determination of specific absorption and diffusion (scattering)

coefficients, which determine the value for α, will be carried

out separately.

in eq 2 as the attenuation coefficient. It depends

not only on the absorption coefficient μ but also on the anisotropic

diffusion coefficient. In this study, it is the exponential thickness

dependence of total transmittance in eq 2 that is used to understand and predict transmittance

of TWs. The attenuation coefficient α is determined through

fitting of experimentally measured transmittance data. The material-specific

constant α contains the effects of both light absorption and

diffusion (where the diffusion coefficient D ∼

(3(μs + μ))−1 and μs refers to scattering coefficient).

Quantitative determination of specific absorption and diffusion (scattering)

coefficients, which determine the value for α, will be carried

out separately.

Results and Discussion

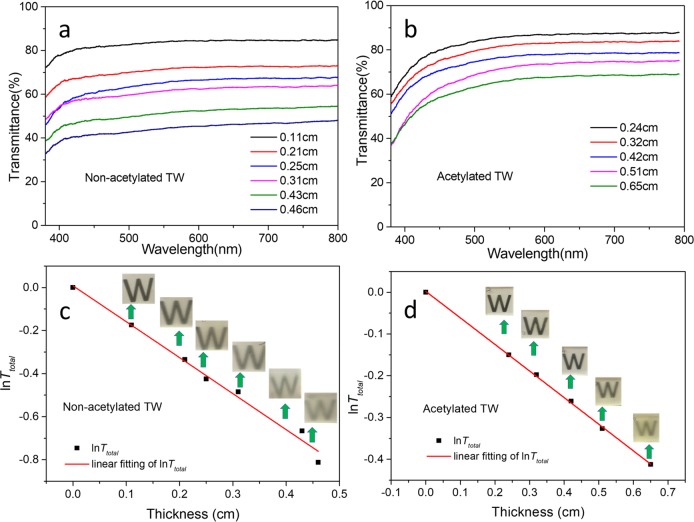

Data for total transmittance of nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW materials with different thicknesses are presented in Figure 2a, b. Both the nonacetylated TW and the acetylated TW show decreased transmittance with increased thickness in the visible light region. The relatively lower transmittance at blue-light spectral region is most likely due to absorption by the remaining lignin. However, the wavelength dependence is not a strong effect and does not strongly influence the total transmittance. The transmittance of nonacetylated TW at a wavelength of 550 nm was 84, 71.5, 65.3, 61.6, 51.3, and 44.4% with sample thicknesses of 0.11, 0.21, 0.25, 0.31, 0.43, and 0.46 cm, respectively. The values for acetylated TW were 86, 82.1, 77.1, 72.1, and 66.2% with sample thicknesses of 0.24, 0.32, 0.42, 0.51, and 0.65 cm, respectively. The relationship between the total transmittance and sample thickness is described by eq 2. Figure 2c, d show the linear fit of ln Ttotal and sample thickness d at wavelength 550 nm based on minimizing the root-mean-square (RMS) error between the measured data and the fitted curve. The RMS error is 0.98 for nonacetylated TW, and 0.99 for acetylated TW. The attenuation coefficient α, which reflects how fast light intensity is reduced with increased thickness of TW samples, were obtained as 1.67 ± 0.08 cm–1 for nonacetylated TW, and 0.64 ± 0.01 cm–1 for acetylated TW at 550 nm. The pictures inserted in Figure 2c, d show the appearance of TW samples with different thicknesses on top of a printed symbol “W”. It is apparent that there is increased randomization of light passing through the samples, as the sample thickness is increased. Attenuation coefficients at λ = 500, 600, 650, and 700 nm were also determined for nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW, which are summarized in Table 1. It is interesting that the attenuation coefficient α decreases as the wavelength increases. This is the case for both acetylated and nonacetylated TW. This fact can be tentatively explained invoking Rayleigh scattering, where the scattering strength is strongly inversely proportional to the wavelength. Larger diffusion coefficient for longer wavelengths then leads to a smaller attenuation coefficient. The attenuation coefficient introduced here can be used to predict the total transmittance of a given material and compare light attenuation for different TW materials.

Figure 2.

(a, b) Transmittance spectra of the nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW in the visible range. (c, d) Fitting between the lnTtotal and the sample thickness for nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW at wavelength of 550 nm, respectively. The pictures inseted in c and d show both the TW samples with different thicknesses on top of a printed symbol “W”.

Table 1. Attenuation Coefficients for Both Nonacetylated TW and Acetylated TW at Different Wavelengths.

| 500 nm | 600 nm | 650 nm | 700 nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nonacetylated TW (cm–1) | 1.75 ± 0.13 | 1.62 ± 0.08 | 1.58 ± 0.08 | 1.56 ± 0.07 |

| acetylated TW (cm–1) | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.01 |

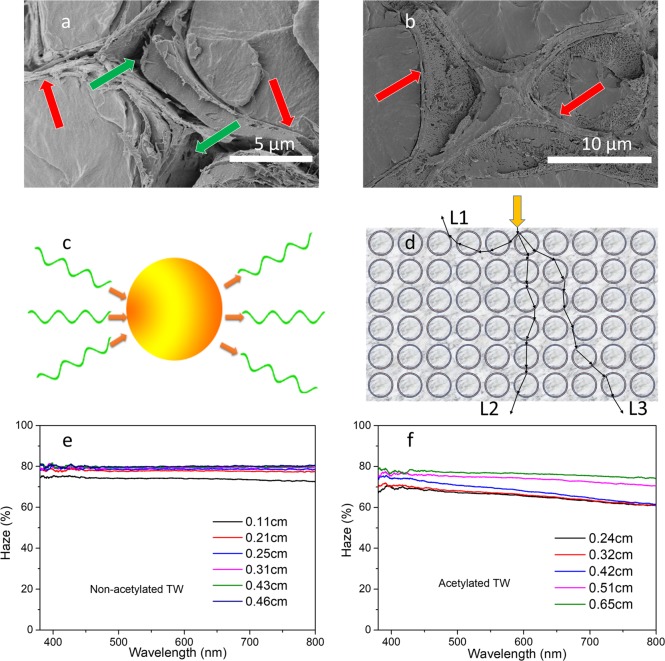

Equation 2 shows that the total transmittance of TW can be strongly influenced by scattering. Two contributions to light scattering inside TW are refractive index mismatch (between wood template and polymer) and air gaps between wood cell wall and the infiltrated polymer. The acetylation process improves the interaction between the wood cell wall and PMMA, reduces the extent of wood/PMMA debond gaps, and results in reduced scattering from corresponding air pockets at wood/PMMA interfaces. Figure 3a, b shows the interfaces (red arrows) between the cell wall and PMMA for nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW, respectively, where light scattering occurs. The presence of air gaps between cell wall and PMMA is particularly apparent in nonacetylated TW, where strong light scattering takes place (Figure 3a, green arrows). The acetylated TW micrograph in Figure 3b does not show apparent wood/PMMA debond gaps, and light scattering is expected to be reduced.

Figure 3.

(a, b) SEM micrographs of freeze-fractured cross-sections of nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW, the arrows show scattering centers (the red arrows are the interface between PMMA and wood cell wall, greens are the air gaps). (c, d) Possible path and path length in the cell lumen and TW samples, respectively. (e, f) Haze spectra of nonacetylated TW and acetylated TW in the visible range.

To explain light scattering inside TW, a simplified scheme of light propagation and scattering mechanisms in TW is suggested in Figure 3c. In this scheme, the wood cells are simplified to have cylindrical shapes, and the absorption coefficient is the same inside the whole material. When a photon travels into cell lumen space, scattering takes place at the interface between the polymer and the wood cell wall, and the photon can go in random directions. Figure 3d schematically shows the possible route for a photon traveling through TW, where scattering occurs at each interface.

Scattering can lead to photon transport in random directions, and the optical path length for individual photons can be very different. Photons can be backscattered with an OPL = L1, or L2 or L3 through the sample, see Figure 3d. Obviously, details of scattering paths are very sensitive to microstructural details in a composite, in particular optical scattering centers and defects. In a material with a larger density of scattering centers (for example in nonacetylated TW), the extent of scattering and the haze are increased. Haze is a measure of the fraction of transmitted light which is scattered forward at wide angles, therefore qualitatively reflecting the scattering coefficient and thereby the diffusion coefficient. The measured haze spectra are presented in Figure 3e, f. The haze of nonacetylated TW at λ = 550 nm was 78.8% with sample thickness 0.25 cm, which is higher than the value for acetylated TW with sample thickness of 0.24 cm (66.7%). The same trend exists for all sample thicknesses. The data show that the haze of nonacetylated TW is always higher than that for acetylated TW at comparable thickness, which means that the scattering in nonacetylated TW is stronger than for acetylated TW, and this also corresponds to higher transmittance for acetylated TW.

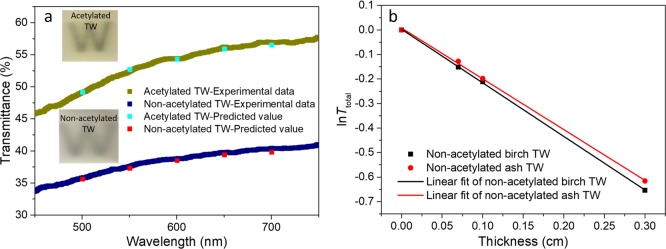

To verify the validity of eq 2 at other sample thicknesses, a nonacetylated TW material with a thickness of 0.59 cm and an acetylated TW material with a thickness of 1 cm (insets in Figure 4a on top of the symbol “W”) were fabricated (the delignification time was 12 h for 0.59 cm sample and 18 h for 1 cm sample). On the basis of the attenuation coefficients obtained from the exponential fitting (Figure 2c, d, Table 1), eq 2 predicts the total transmittance of a nonacetylated TW with thickness 0.59 cm at wavelengths of 500, 550, 600, 650, and 700 nm to be 35.6, 37.3, 38.5, 39.4, and 39.8%, respectively, whereas the experimental data are 35.8, 37.6, 38.8, 39.7, and 40.4%, respectively. The predicted transmittances for acetylated TW with thickness 1 cm at wavelengths of 500, 550, 600, 650, and 700 nm should be 49.2, 52.7, 54.3, 55.9, and 56.5%, respectively, whereas the experimental data are 49.2, 52.4, 54.4%, 56.2, and 56.9%. Both the predictions of nonacetylated and acetylated TW are in good agreement with experimental transmittance data obtained from the integrating sphere (Figure 4a). Thus, this is an additional support of an exponential relationship between the total transmittance and sample thickness. It also suggests that no new type of major optical defects is introduced by TW processing of larger thickness wood templates and the extracted attenuation coefficient is a valid material property.

Figure 4.

(a) Optical transmittances of an acetylated TW with a thickness of 1 cm and nonacetylated TW with a thickness of 0.59 cm. Predicted values are presented together with experimental data. The inserted images show the two types of TW samples on top of a printed symbol “W”. (b) Fitting between total transmittance and the sample thickness of nonacetylated transparent wood made from birch and ash. The transmittance was collected at wavelength of 550 nm.

To test the generality of this approach, we also applied the model to TW made from other wood species. In this work, nonacetylated TW based on birch (density 620 kg/m3; thickness: 0.07, 0.1, and 0.3 cm; purchased from Calexico Wood AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) and ash (density 650 kg/m3; thickness: 0.07, 0.1, and 0.3 cm; purchased from Calexico Wood AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) were also prepared and studied. The fitting showing the relationship between Ttotal (at wavelength = 550 nm) and thickness of the TW samples could be found in Figure 4b. The extracted attenuation coefficients were 2.07 ± 0.05 cm–1 for birch-based TW and 2.18 ± 0.02 cm–1 for ash-based TW. The higher attenuation coefficients for nonacetylated TWs made from birch and ash compared with that of balsa were mainly ascribed to the higher volume fraction of cellulose in these two materials, which leads to a higher concentration of scattering centers and in turn lower diffusion coefficients. Light traveling through such TW samples covers on average longer optical path lengths and experiences more absorption.

Conclusions

In this work, the photon diffusion equation was used to model a general dependence of total light transmittance of TW samples as a function of sample thickness. The dependence follows an exponentially decaying expression containing attenuation coefficient as the key parameter that characterizes a certain material. Acetylated and nonacetylated balsa TW samples with different thicknesses were prepared and investigated. On the basis of fitting of transmittance, we obtained attenuation coefficients for the acetylated and nonacetylated TW samples as 0.64 ± 0.01 and 1.67 ± 0.08 cm–1, respectively, at a wavelength of 550 nm (with weak dependence on wavelength at measured spectral range). The coefficients are qualitatively supported by our haze measurements. According to our model, such attenuation coefficient encompasses both light absorption and scattering effects to light transmittance, and can therefore serve as a primitive material property inherent to a particular type of TW prepared by a certain process. It not only can be used to predict total transmittance across a wider range of sample thicknesses, but also can facilitate cross-comparison of transmittances of samples derived from different wood species. The validity of the model was verified by using TWs also made from birch and ash. Besides transparent wood, our result based on the photon diffusion equation can potentially be generalized to investigate total transmittance of other anisotropic scattering materials, for example, transparent films made of wood fibers, glass fiber composites, nanoparticle composites, or anisotropic polymers.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from KTH and European Research Council Advanced Grant (742733) Wood NanoTech and from Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation through the Wallenberg Wood Science Center at KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Li Y.; Yang X.; Fu Q.; Rojas R.; Yan M.; Berglund L. A. Towards Centimeter Thick Transparent Wood through Interface Manipulation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 1094–1101. 10.1039/C7TA09973H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Fu Q.; Yu S.; Yan M.; Berglund L. Optically Transparent Wood from a Nanoporous Cellulosic Template: Combining Functional and Structural Performance. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17 (4), 1358–1364. 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Song J.; Li T.; Gong A.; Wang Y.; Dai J.; Yao Y.; Luo W.; Henderson D.; Hu L. Highly Anisotropic, Highly Transparent Wood Composites. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28 (26), 5181–5187. 10.1002/adma.201600427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey M.; Widner D.; Segmehl J. S.; Casdorff K.; Keplinger T.; Burgert I. Delignified and Densified Cellulose Bulk Materials with Excellent Tensile Properties for Sustainable Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (5), 5030–5037. 10.1021/acsami.7b18646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano H.; Hirose A.; Collins P. J.; Yazaki Y. Effects of the Removal of Matrix Substances as a Pretreatment in the Production of High Strength Resin Impregnated Wood Based Materials. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2001, 20 (12), 1125–1126. 10.1023/A:1010992307614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Fu Q.; Rojas R.; Yan M.; Lawoko M.; Berglund L. Lignin-Retaining Transparent Wood. ChemSusChem 2017, 10 (17), 3445–3451. 10.1002/cssc.201701089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink S. Transparent Wood - a New Approach in the Functional-Study of Wood Structure. Holzforschung 1992, 46 (5), 403–408. 10.1515/hfsg.1992.46.5.403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q.; Yan M.; Jungstedt E.; Yang X.; Li Y.; Berglund L. A. Transparent Plywood as a Load-Bearing and Luminescent Biocomposite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 164, 296–303. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Zhan T.; Liu Y.; Shi J.; Pan B.; Zhang Y.; Cai L.; Shi S. Q. Large-Size Transparent Wood for Energy-Saving Building Applications. ChemSusChem 2018, 11 (23), 4086–4093. 10.1002/cssc.201801826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Guo X.; He Y.; Zheng R. A Green Steam-Modified Delignification Method to Prepare Low-Lignin Delignified Wood for Thick, Large Highly Transparent Wood Composites. J. Mater. Res. 2019, 34 (6), 932–940. 10.1557/jmr.2018.466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Yu S.; Veinot J. G. C.; Linnros J.; Berglund L.; Sychugov I. Luminescent Transparent Wood. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5 (1), 1600834. 10.1002/adom.201600834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva E.; Li Y.; Sychugov I.; Mensi M.; Berglund L.; Popov S. Lasing from Organic Dye Molecules Embedded in Transparent Wood. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5 (10), 1700057. 10.1002/adom.201700057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan W.; Gao L.; Xiao S.; Zhang W.; Zhan X.; Li J. Transparent Magnetic Wood Composites Based on Immobilizing Fe3O4 Nanoparticles into a Delignified Wood Template. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52 (6), 3321–3329. 10.1007/s10853-016-0619-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari C.; Li Y.; Chen H.; Yan M.; Berglund L. A. Transparent Wood for Thermal Energy Storage and Reversible Optical Transmittance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11 (22), 20465–20472. 10.1021/acsami.9b05525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Yao Y.; Yao J.; Zhang L.; Chen Z.; Gao Y.; Luo H. Transparent Wood Containing CsxWO3 Nanoparticles for Heat-Shielding Window Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5 (13), 6019–6024. 10.1039/C7TA00261K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; De Keersmaecker M.; Berglund L.; Lang A. W.; Reynolds J. R.; Shen D. E.; Österholm A. M. Transparent Wood Smart Windows: Polymer Electrochromic Devices Based on Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(Styrene Sulfonate) Electrodes. ChemSusChem 2018, 11 (5), 854–863. 10.1002/cssc.201702026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M.; Li T.; Davis C. S.; Yao Y.; Dai J.; Wang Y.; AlQatari F.; Gilman J. W.; Hu L. Transparent and Haze Wood Composites for Highly Efficient Broadband Light Management in Solar Cells. Nano Energy 2016, 26, 332–339. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Zhu M.; Yang Z.; Song J.; Dai J.; Yao Y.; Luo W.; Pastel G.; Yang B.; Hu L. Wood Composite as an Energy Efficient Building Material: Guided Sunlight Transmittance and Effective Thermal Insulation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6 (22), 1601122. 10.1002/aenm.201601122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva E.; Chen H.; Li Y.; Sychugov I.; Yan M.; Berglund L.; Popov S. Light Scattering by Structurally Anisotropic Media: A Benchmark with Transparent Wood. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6 (23), 1800999. 10.1002/adom.201800999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J. J.; Berg E. P.; Lee J. W.; Yao G. Characterizing Beef Muscles with Optical Scattering and Absorption Coefficients in VIS-NIR Region. Meat Sci. 2007, 75 (1), 78–83. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savo R.; Pierrat R.; Najar U.; Carminati R.; Rotter S.; Gigan S. Observation of Mean Path Length Invariance in Light-Scattering Media. Science 2017, 358 (6364), 765–768. 10.1126/science.aan4054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm D. J. Explaining Some Light Scattering Properties of Milk Using Representative Layer Theory. J. Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2013, 21 (5), 323–339. 10.1255/jnirs.1071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen N. A.; Xiao S. Slow-Light Enhancement of Beer-Lambert-Bouguer Absorption. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90 (14), 141108. 10.1063/1.2720270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sassaroli A.; Fantini S. Comment on the Modified Beer-Lambert Law for Scattering Media. Phys. Med. Biol. 2004, 49 (14), 255–257. 10.1088/0031-9155/49/14/N07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis L.; Herman P.; Eke A. The Modified Beer-Lambert Law Revisited. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51 (5), N91–N98. 10.1088/0031-9155/51/5/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobrecht A.; Bendoula R.; Roger J. M.; Bellon-Maurel V. Combining Linear Polarization Spectroscopy and the Representative Layer Theory to Measure the Beer-Lambert Law Absorbance of Highly Scattering Materials. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 853 (1), 486–494. 10.1016/j.aca.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens H.; Nielsen J. P.; Engelsen S. B. Light Scattering and Light Absorbance Separated by Extended Multiplicative Signal Correction. Application to near-Infrared Transmission Analysis of Powder Mixtures. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75 (3), 394–404. 10.1021/ac020194w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durian D. J. The Diffusion Coefficient Depends on Absorption. Opt. Lett. 1998, 23 (19), 1502–1504. 10.1364/OL.23.001502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner C.; Jensen H. W. Light Diffusion in Multi-Layered Translucent Materials. ACM Trans. Graph. 2005, 24 (3), 1032–1039. 10.1145/1073204.1073308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elaloufi R.; Carminati R.; Greffet J.-J. Definition of the Diffusion Coefficient in Scattering and Absorbing Media. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2003, 20 (4), 678–685. 10.1364/JOSAA.20.000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. M.; Bret B. P. J.; Rivas J. G.; Kelly J. J.; Lagendijk A. Anisotropic Diffusion of Light in a Strongly Scattering Material. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89 (24), 243901. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.243901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTM International. ASTM D1003: Standard Test Method for Haze and Luminous Transmittance of Transparent Plastics; ASTM, 2003; pp 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tihonov A. N.; Samarsky A. A.. Equations of Mathematical Physics; Nauka: Moscow, 1977; p 654. [Google Scholar]

- Dunaev A. S.; Schlychkov V. I.. Special Functions; Ural Federal University: Ekaterinburg, Russia, 2015; p 802–809. [Google Scholar]