Abstract

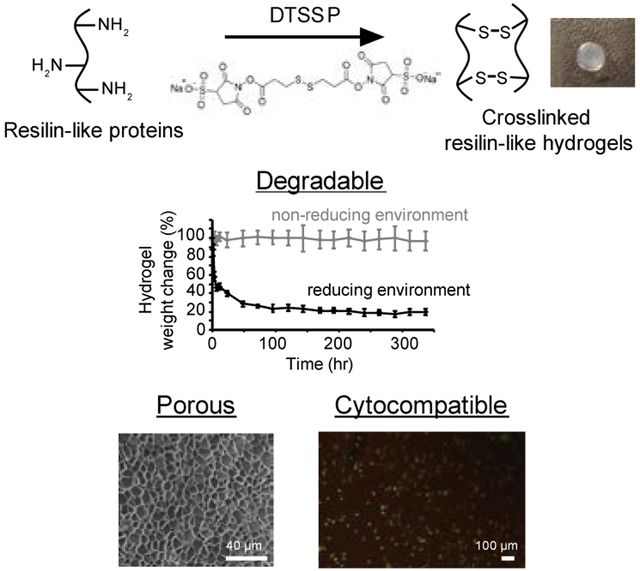

Resilin, a protein found in insect cuticles, is renowned for its outstanding elastomeric properties. Our lab previously developed a recombinant protein, which consisted of consensus resilin-like repeats from Anopheles gambiae, and demonstrated its potential in cartilage and vascular engineering. To broaden the versatility of the resilin-like protein, this study utilized a cleavable crosslinker, which contains a disulfide bond, to develop smart resilin-like hydrogels that are redox-responsive. The hydrogels exhibited a porous structure and a stable storage modulus (G’) of ~3 kPa. NIH/3T3 fibroblasts cultured on hydrogels for 24 h had a high viability (>95%). In addition, the redox-responsive hydrogels showed significant degradation in a reducing environment (10 mM glutathione (GSH)). The release profiles of fluorescently-labeled dextrans encapsulated within the hydrogels were assessed in vitro. For dextran that was estimated to be larger than the mesh size of the gel, faster release was observed in the presence of reducing agents due to degradation of the hydrogel networks. These studies thus demonstrate the potential of using these smart hydrogels in a variety of applications ranging from scaffolds for tissue engineering to drug delivery systems that target the intracellular reductive environments of tumors.

Keywords: protein engineering, DTSSP, degradable hydrogels, smart materials, recombinant proteins

Graphical Abstract

A stimuli-responsive recombinant resilin-like hydrogel with potential for targeted drug delivery and tissue engineering applications is developed using a cleavable crosslinker sensitive to reducing environments. This study characterizes the physical and mechanical properties and demonstrates the cell compatibility of the hydrogels. The redox-responsive hydrogels degrade and have a faster release rate of encapsulated molecules under reducing compared to non-reducing environments.

1. Introduction

Due to their remarkable mechanical properties, structural proteins including elastin, silk, and resilin are being widely investigated for applications in tissue engineering and drug delivery.[1] Genetic engineering offers a powerful tool for the development of protein-based biomaterials with well-defined sequence and molecular weight.[2, 3] These techniques have been used successfully in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications to engineer tailor-made materials with exquisite control over structure and function. For example, fibronectin-derived cell-binding domains were incorporated into elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) for application in neural engineering.[4] Schwann cells showed increased proliferation and maintained their phenotype when cultured on these ELPs. Another example designed and conjugated a cell cycle inhibitory peptide to an ELP with an inverse phase transition temperature between body temperature (37 °C) and temperatures corresponding to tumor hyperthermia (42 °C).[5] The ELP coacervated in tumor cells and improved tumor growth inhibition when used in combination with an anti-cancer drug.

Resilin is another elastomeric protein that has been widely studied recently. Natural resilin was first identified as a highly resilient elastomeric protein in insect cuticles by Weis-Fogh in the early 1960s.[6-8] The first recombinant resilin-like protein, rec1-resilin, encoding the first exon of the Drosophila melanogaster CG15920 gene was synthesized by Elvin and coworkers in 2005.[9] Rec1-resilin exhibited remarkable resilience similar to that of native resilin. Lyons et al. later demonstrated that recombinant proteins composed of repetitive sequences derived from rec1-resilin resulted in similar properties to those of rec1-resilin.[10, 11] Thereafter, resilin-like proteins with repetitive sequences derived from different species have been developed.

These resilin-like proteins have demonstrated potential in tissue engineering applications because of their mechanical similarities to native tissues.[12-15] For instance, RLP12, which is composed of 12 resilin-like repeats derived from D. melanogaster, showed similar mechanical properties to those of human vocal fold tissues under high frequency.[12] In addition, RZ10-RGD, which was developed by our lab, consisted of 10 repeats of the consensus resilin-like sequence from A. gambiae and exhibited a compressive modulus on the same order of magnitude as that of human articular cartilage.[13] Furthermore, a variety of bioactive domains, such as peptides derived from bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), have also been incorporated into resilin-like proteins to expand their applications in bone and blood vessel engineering.[16-18]

The objective of this study was to broaden the versatility of resilin-like proteins by creating degradable resilin-like hydrogels that are responsive to their environment. Redox-sensitive degradation can be a beneficial functionality for biomaterials in both tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. For example, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-based hydrogels with disulfide crosslinks were loaded with BMP-2 and implanted in a rabbit critical bone defect model.[19] The hydrogels degraded due to secretion of extracellular glutathione (GSH) from cells, and new bone formed during this time. After 4 weeks, it was observed that more new bone was formed with degradable PEG hydrogels compared to non-degradable ones. For drug delivery applications, Pan et al. synthesized crosslinked poly(methacrylic acid) (PMMA)-based nanohydrogels that were responsive to low-pH and reducing conditions.[20] When GSH was added to the environment, nanohydrogels degraded and released anti-cancer drugs more quickly than when in phosphate buffer. It is noted that tumor tissues have a >4-fold higher intracellular GSH concentration than normal tissues;[21] thus, redox-responsive hydrogels have the potential for effective delivery of anti-cancer drugs to tumors.

Therefore, we explored a redox-responsive crosslinker, 3, 3’-dithiobis(sulfosuccinimidyl propionate) (DTSSP) to manufacture resilin-like hydrogels that degrade under reducing environments. DTSSP has two N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS) groups, which can react with primary amine groups in resilin-like proteins and thus form crosslinked networks, and has been utilized to make targeted drug delivery nanoparticles.[22, 23] Reducing agents can cleave the disulfide bond within the DTSSP molecule and cause the disruption of crosslinked networks. In this study, we demonstrated the formation of degradable resilin-like hydrogels and characterized the rheological properties, water content, swelling ratio, and degradation behavior of the hydrogels. The porous structure and cytocompatibility of hydrogels were also evaluated for tissue engineering applications. Furthermore, various sizes of dextran labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were encapsulated in the resilin-like hydrogels, and their release profiles under reducing environments were demonstrated in vitro.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Protein-based Hydrogel Formation

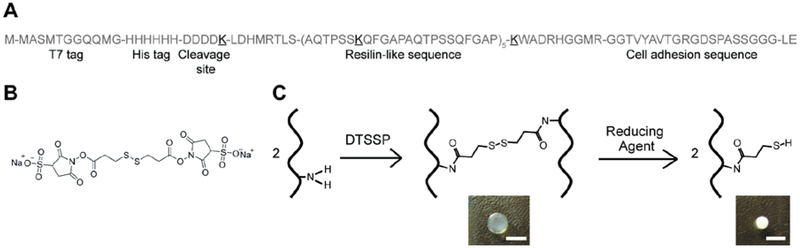

We previously developed a recombinant resilin-like protein (RZ10-RGD) that is composed of 10 repeats of the resilin-like sequence derived from A. gambiae and an integrin-binding sequence (GRGDSP) for cell adhesion.[13] Specifically, one lysine (K) residue was introduced in every 2 repeats of the resilin-like sequence as crosslinking sites. The detailed amino acid sequence of RZ10-RGD is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Redox-responsive RZ10-RGD hydrogels were successfully developed. (A) The detailed amino acid sequence of RZ10-RGD. Lysine (K, boldface and underlined) residues were incorporated as crosslinking sites. (B) The DTSSP molecule contains two sulfo-NHS ester groups, which can react with primary amines. The disulfide bond within the DTSSP molecule can be cleaved in the presence of reducing agents. (C) A scheme illustrating the crosslinking reaction of RZ10-RGD with DTSSP and the degradation reaction in reducing conditions. Pictures of crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels in non-reducing and reducing environments are also shown. Scale bar represents 0.5 cm.

Resilin-like hydrogels were created using a thiol-cleavable crosslinker, DTSSP, which contains a sulfo-NHS ester on each end (Figure 1B). The sulfo-NHS ester groups interacted with primary amines in RZ10-RGD to form stable amide bonds (Figure 1C).

2.2. Swelling Ratio and Water Content

After formation, hydrogels were immersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the weights of hydrogels were monitored. There was no significant change in the wet weight of 16 wt% RZ10-RGD hydrogels after 48 hr. This result indicated that the swollen hydrogels had reached equilibrium at that time point (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Therefore, all swollen hydrogels used in this study were immersed in PBS for at least 72 hr to ensure complete hydration. Dry weights were obtained, and the swelling ratio and water content of 16 wt% hydrogels were calculated. Results showed that 16 wt% hydrogels were highly hydrophilic and possessed a water content of 85.1 ± 1.1% and a swelling ratio of 6.74 ± 0.48.

The swelling ratio of DTSSP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD was comparable to that of RZ10-RGD when crosslinked with transglutaminase (swelling ratios of 8 – 13)[15] and RLP12 (swelling ratios of 6 – 9).[12] The water content of RZ10-RGD hydrogels was slightly higher than that of natural resilin (60%)[6] but was comparable to other resilin-like proteins (80 – 96%).[9, 12, 14, 15] The high water content of RZ10-RGD hydrogels makes them promising biomaterials for tissue engineering scaffolds since they mimic the high water content of natural soft tissues.[24] In addition, its hydrophilicity facilitates the use of RZ10-RGD as an effective drug delivery carrier for hydrophilic drugs.[25]

2.3. Rheological Properties

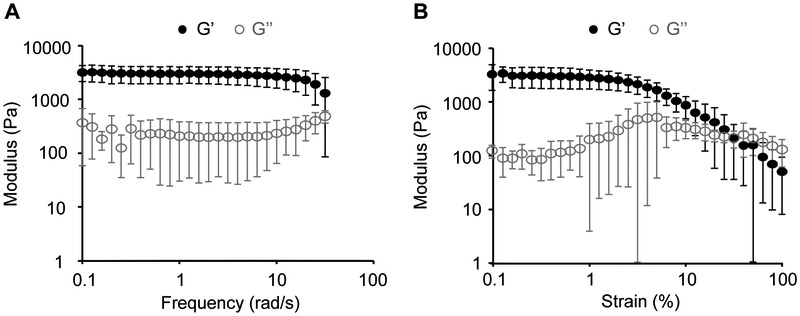

Crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels were subjected to frequency sweeps and strain sweeps. Crosslinked RZ10-RGD presented a significantly larger storage modulus (G’) than loss modulus (G’’). The large G’ values compared to G’’ values indicated gel-like behavior of the crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels (Figure 2). Specifically, the storage modulus (G’) of 16 wt% RZ10-RGD hydrogels was ~3 kPa. Frequency sweeps indicated that G’ was independent of frequency over the range of 0.1 – 10 rad/s (Figure 2A). The linear viscoelastic range (LVR) of RZ10-RGD hydrogels was determined to be 0.1 – 6% strain (Figure 2B). In this range, RZ10-RGD hydrogels had a steady G’ value and were elastic networks. Consequently, all rheological characterizations presented in this study were performed within the LVR (strain = 1%).

Figure 2.

Dynamic oscillatory rheological properties of RZ10-RGD hydrogels. (A) Frequency sweeps and (B) strain sweeps of 16 wt% RZ10-RGD hydrogels. The hydrogels exhibited stable G’ within (A) the frequency range of 0.1 – 10 rad/s and (B) the strain range of 0.1 – 6% strain. Black solid symbols represent G’ (storage modulus), and gray open symbols represent G’’ (loss modulus).

Our lab previously characterized 16 wt% RZ10-RGD hydrogels crosslinked with a non-degradable crosslinker, tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine (THP).[13] The DTSSP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels presented in this study exhibited a G’ value (~3 kPa), which is an order of magnitude less than that of THP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels (~22 kPa). A potential explanation for the softer hydrogels could be the different hydration levels of RZ10-RGD hydrogels during rheology measurements. DTSSP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels were fully swollen whereas THP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD gels were not. Similar to the current study, highly swollen rec1-resilin hydrogels were also very soft.[9] Truong et al. proposed that water served as a plasticizer to increase the molecular chain mobility and resulted in a decrease in the stiffness of the protein network.[26]

Soft RZ10-RGD hydrogels showed comparable mechanical properties with other elastomeric proteins, including RZ10-RGD crosslinked with transglutaminase (0.04 – 7 kPa), [15] RLP12-based proteins (0.5 – 24 kPa), [12, 14, 27-31] resilin-based proteins crosslinked with metal ions (2 – 21 kPa), [32] and ELPs (5.8 – 45.8 kPa).[33] Materials with this range of properties show potential for tissue engineering applications in soft tissues such as muscles (8 – 16 kPa)[34] and vocal folds (20 – 40 kPa).[28, 35] Furthermore, studies with protein-based biomaterials demonstrate that their mechanical properties can be easily tuned. For example, the mechanical properties of RLP12 can be modulated between 0.5 – 20 kPa by changing the protein concentration or crosslinking ratio.[12, 28] Thus, it is possible to further expand the versatility of RZ10-RGD by tuning the mechanical properties of RZ10-RGD to be similar to other native tissues.

2.4. In Vitro Degradation

DTSSP possesses a disulfide bond within the spacer arm (Figure 1B). The disulfide bond is expected to be reduced in response to reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) (TCEP), and GSH. In particular, GSH is the most abundant low-molecular-weight thiol in the body.[36] The concentration of GSH in plasma is around 2 – 20 μM but is ~100-fold higher in cells (0.5 – 10 mM). The significant difference between intra- and extracellular GSH concentrations has offered a platform to develop redox-responsive materials for targeted drug delivery.[37] Therefore, to demonstrate the potential use of redox-responsive RZ10-RGD hydrogels in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications, we investigated the degradation behavior of RZ10-RGD hydrogels in response to GSH.

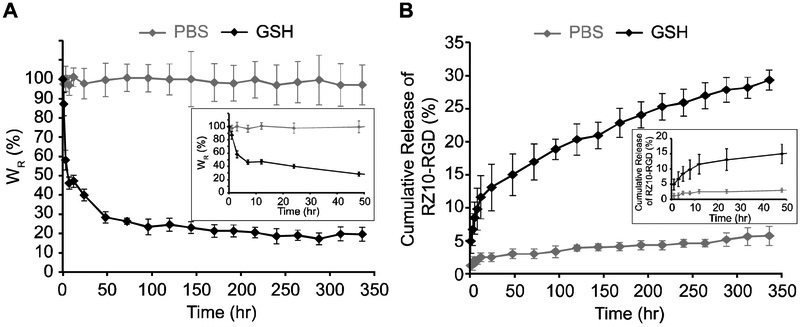

The mass of RZ10-RGD hydrogels immersed in a GSH solution decreased drastically within 48 h and decreased slowly afterwards (Figure 3A). On the other hand, hydrogels in PBS retained constant wet weights over 336 hr (or 2 weeks) and showed no degradation of the RZ10-RGD networks. In addition, hydrogels treated with GSH decreased in size without destruction of the disc shape (Figure 1C). The shrinkage of the RZ10-RGD hydrogels suggested that the decrease in gel weight could potentially be due to a decrease in water content of the gels when treated with GSH.

Figure 3.

In vitro degradation of RZ10-RGD hydrogels in reducing (10 mM GSH) and non-reducing (PBS) environments. (A) The percentage of relative weight change (WR) for RZ10-RGD hydrogels over 336 hr. Hydrogel weight at 0 hr was treated as 100%. (B) Cumulative percentage of RZ10-RGD released in the supernatant over 336 hr. Total amount of crosslinked RZ10-RGD was treated as 100%. Black symbols represent samples in GSH, and gray symbols represent samples in PBS.

While monitoring the mass change of hydrogels over time offers an easy method to determine degradation behavior, its results do not distinguish between decreases in protein content and water content of the hydrogels. To better understand the protein loss from hydrogels due to degradation, the amount of protein released from the hydrogels was measured directly. When gels were immersed in a GSH solution, a sharp release of RZ10-RGD was observed within the first 12 h and was followed by a gradual release of RZ10-RGD over 336 hr (Figure 3B). Hydrogels in PBS showed low levels (~5%) of released RZ10-RGD over 336 hr. Overall, results from both analytical methods to examine degradation present a similar trend in which hydrogels in a GSH solution underwent rapid initial degradation followed by more gradual degradation over 336 hr.

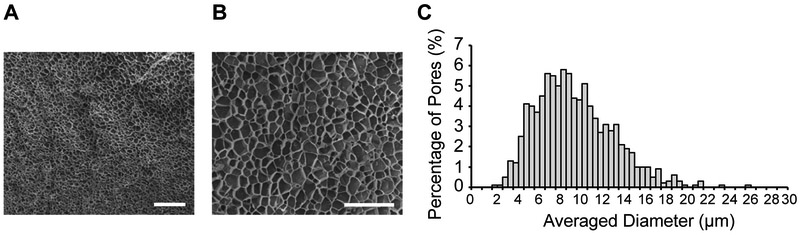

2.5. Structural Networks and Pore Size Determination

Cross-sectional images using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed porous and well-connected structures in RZ10-RGD hydrogels (Figure 4A and 4B). Swollen RZ10-RGD hydrogels possessed a wide range of pore sizes (3 – 24 μm) with an average pore size of 10.0 ± 0.8 μm. A histogram of the pore size distribution is shown in Figure 4C.

Figure 4.

RZ10-RGD hydrogels exhibited a highly porous network. SEM images of hydrogel cross-sections at a magnification of (A) 500x and (B) 2000x. Scale bars represent (A) 200 μm and (B) 40 μm. (C) Histogram of pore size distribution in RZ10-RGD hydrogels. RZ10-RGD hydrogels had a wide range of pore sizes with an average of ~10 μm.

The SEM images showed that RZ10-RGD hydrogels had a highly porous network with a pore size similar to the size of cells (fibroblasts have a size of 10 – 20 μm). Thus, cells could potentially migrate through the RZ10-RGD hydrogels. Also, porous networks can facilitate diffusion of nutrients and oxygen and allow for deposition of new extracellular matrix.[38] Porous networks are thus attractive candidates for tissue engineering applications. For instance, chitosan hydrogels with pore diameters of 30 – 40 μm showed effective cell ingrowth.[39] Another study also demonstrated that cardiac implants with a pore size of 30 – 40 μm showed enhanced angiogenesis.[40]

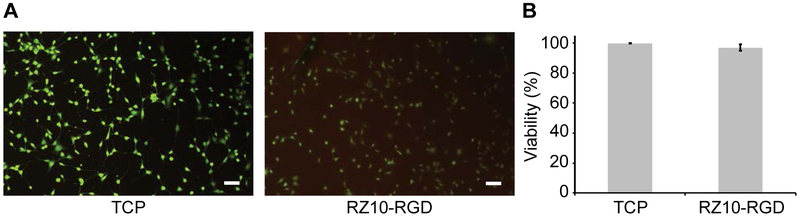

2.6. Cell Viability

Cytocompatibility is an important criterion for materials used in tissue engineering and drug delivery. Representative LIVE/DEAD images of NIH/3T3 fibroblasts on either RZ10-RGD hydrogels or tissue culture polystyrene (TCP) are shown in Figure 5A. NIH/3T3 fibroblasts showed a viability of 96.9 ± 2.2% on RZ10-RGD hydrogels whereas they had 99.8 ± 0.1% viability on TCP (positive control surface) (Figure 5B). Cells on RZ10-RGD hydrogels had similar viability to cells on TCP. Overall, the high viability of NIH/3T3 fibroblasts suggested that RZ10-RGD hydrogels crosslinked with DTSSP were cytocompatible.

Figure 5.

RZ10-RGD hydrogels were cytocompatible. (A) LIVE/DEAD images of NIH/3T3 fibroblasts cultured for 24 h on TCP or RZ10-RGD hydrogels. Live cells were stained green, and dead cells were stained red. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (B) High cell viability (>95%) was observed on both TCP and RZ10-RGD. No significant difference in cell viability was observed between the two groups (unpaired two sample t-test, p > 0.05).

RZ10-RGD hydrogels were cytocompatible, and this finding is similar to other resilin-like hydrogels.[14, 15, 27, 29, 30, 41] For example, NIH/3T3 fibroblasts cultured on RLP12 hydrogels crosslinked with (tris(hydroxymethyl)phosphine)propionic acid (THPP) showed well-organized actin stress fibers similar to those on TCP.[41] Furthermore, human mesenchymal stem cells showed high viability when cultured on RZ10-RGD crosslinked with transglutaminase[15] or when encapsulated in RLP hydrogels crosslinked with THP[29] or PEG.[14, 27, 30] Recent studies demonstrated the promise of resilin-like proteins in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications by showing the biocompatibility in an animal model.[31, 42] DTSSP has also been shown to trigger minimal inflammation in the rat subcutaneous space.[43]

2.7. In Vitro Release of FITC-Dextran

In the past decade, redox-responsive degradable biomaterials have emerged as an interesting tool in triggered delivery of bioactive molecules such as DNA, proteins, and drugs.[44] We investigated the ability of the redox-sensitive RZ10-RGD system to deliver high-molecular-weight protein drugs that have low diffusion coefficients. The release rate of protein drugs is expected to be minimal under non-reducing environments but increase rapidly under a reducing environment due to degradation of the RZ10-RGD scaffolds.

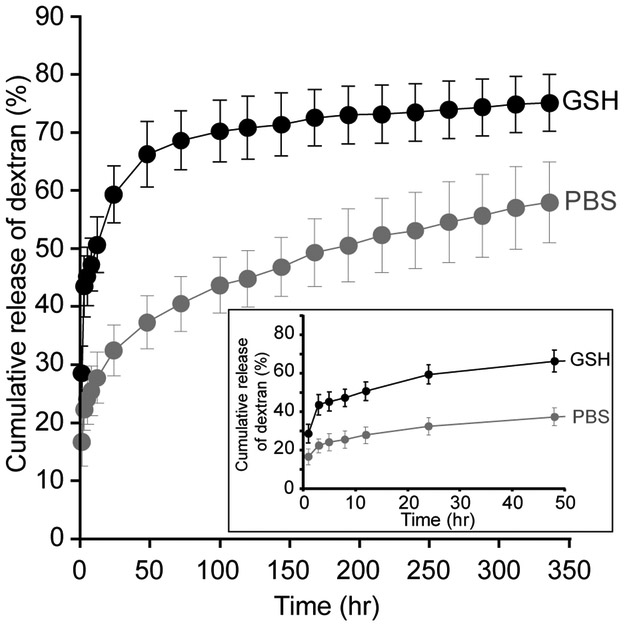

Dextran with a molecular weight (MW) of 150 kDa was chosen as a model drug, and FITC-labeled dextran was encapsulated in RZ10-RGD hydrogels. Dextran-loaded hydrogels were immersed in either PBS (non-reducing environment) or a 10 mM GSH solution. Within 48 h, ~66% of dextran was released from RZ10-RGD hydrogels in the presence of GSH whereas only half that amount of dextran (~37%) was released in a non-reducing environment (Figure 6). In the presence of GSH, the amount of released dextran quickly reached equilibrium after ~96 hr. On the other hand, dextran showed a sustained release over 336 hr under a non-reducing environment. The release behavior of dextran indicated that RZ10-RGD hydrogels could respond to reducing environments quickly and release most of the loaded dextran in a short period of time.

Figure 6.

In vitro release profile of FITC-labeled dextran (150 kDa) from RZ10-RGD hydrogels in reducing (10 mM GSH) and non-reducing (PBS) environments. Total amount of encapsulated FITC-dextran was treated as 100%. Black symbols represent samples in GSH, and gray symbols represent samples in PBS.

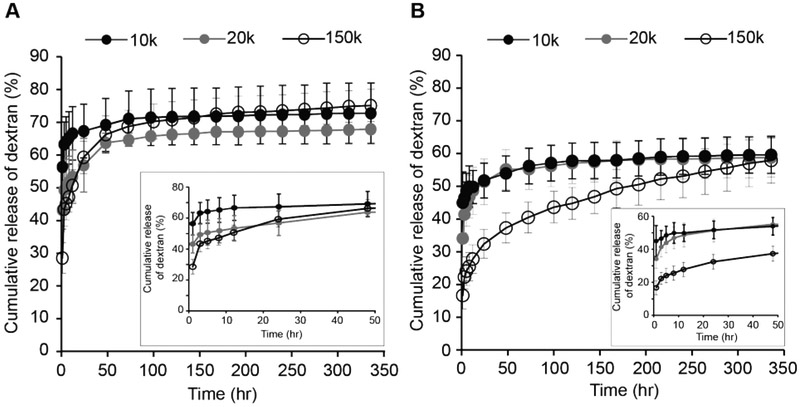

Since the delivery rate can depend on the size of the encapsulated molecules, we investigated the effects of the MW of the encapsulated molecule on the release rate in the RZ10-RGD system. Dextrans with three different MWs (10, 20 and 150 kDa) were chosen. Specifically, dextrans with MWs of 10 and 20 kDa were chosen to mimic molecules that have MWs similar to or smaller than RZ10-RGD, and a dextran with MW of 150 kDa was chosen to imitate large biopharmaceuticals. When GSH was present, there was no significant difference between the release rates regardless of the size of encapsulated dextran after 24 h (Figure 7A). The rapid degradation of the RZ10-RGD hydrogel network in a reducing environment caused a rapid release of dextran of all sizes. On the other hand, under non-reducing conditions, the amount of small-MW dextrans (10 and 20 kDa) released reached equilibrium within 96 hr whereas the large-MW dextran (150 kDa) showed a continuous release over 336 hr (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

In vitro release profile of various sizes of FITC-labeled dextran (10, 20, and 150 kDa) from RZ10-RGD hydrogels in (A) reducing (10 mM GSH) and (B) non-reducing (PBS) environments. Total amount of encapsulated FITC-dextran was treated as 100%. Black solid symbols represent 10 kDa dextran, gray solid symbols represent 20 kDa dextran, and black open symbols represent 150 kDa dextran.

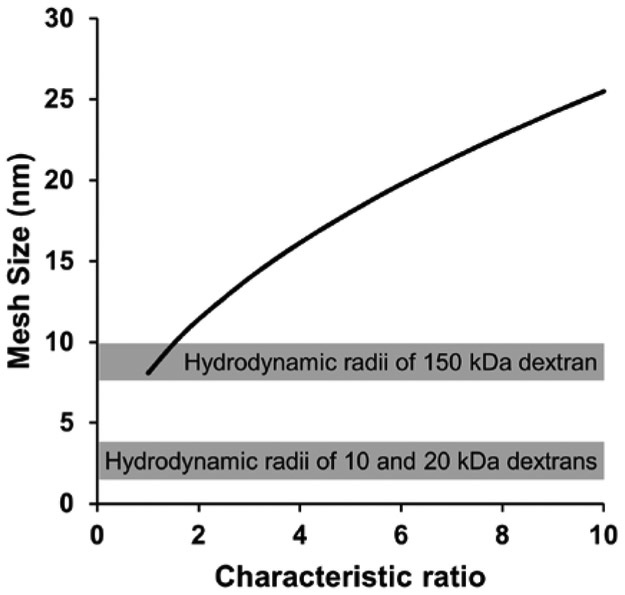

We hypothesized that in non-reducing environments the release of dextrans was predominantly due to diffusion. Diffusion kinetics of small molecules in a hydrogel network are governed by the mesh size of the network.[45] We estimated the mesh size of RZ10-RGD using the swelling ratio data in the non-reducing environment and Flory-Rehner theory.[46] In Figure 8, calculated mesh size was plotted as a function of the characteristic ratio (Cn), which is the ratio of the mean square end-to-end distance to the total length of the rigid segments of a polymer. Because the Cn of resilin, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported yet, it was estimated to span one to ten based on the reported values of several polypeptide copolymers.[47] We then compared the range of possible mesh sizes to the hydrodynamic radii of the three different dextrans used in this study. It is clear that the 10 and 20 kDa dextrans had hydrodynamic radii (~2–3 nm)[48, 49] that are much smaller than the estimated mesh size of the RZ10-RGD hydrogel. On the other hand, the 150 kDa dextran possessed a hydrodynamic radius estimated to be 8.5–10 nm,[48, 49] and this radius was similar or smaller than the estimated mesh size. As a result, a slower diffusion rate of the 150 kDa dextran in the hydrogel network would be expected compared to the rate of the 10 or 20 kDa dextran. These estimates correlated well with the results in a non-reducing environment (Figure 7B) where the 150 kDa dextran had a slower release rate than the 10 and 20 kDa dextrans.

Figure 8.

Mesh size estimation of RZ10-RGD hydrogels using Flory-Rehner theory[46]. The mesh size was calculated using a characteristic ratio that ranged from 1 to 10. The gray boxes indicate the ranges of estimated hydrodynamic radii of dextrans used for the in vitro release experiments.

We noted that the 10 and 20 kDa dextrans did not exhibit large differences in release rate between non-reducing and reducing environments (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Since both of their hydrodynamic radii were smaller than the mesh size of the hydrogel in the non-reducing environment, we hypothesized that the effect from increased mesh size due to network degradation in the reducing environment would not significantly accelerate the diffusion rate of 10 and 20 kDa dextrans.

It has previously been observed that for the same matrix delivery system, there exists a MW cut-off above which the diffusion of encapsulated molecules is strictly impeded.[50] Since our goal was to design a system that would enable targeted drug delivery in response to a reducing environment, our results demonstrate that random release of encapsulated molecules from the current RZ10-RGD hydrogel system can be avoided when encapsulating molecules equal to or larger than the particle size of the 150 kDa dextrans. Besides increasing the particle size of the encapsulated molecules, increasing the protein concentration of the hydrogel carrier could also potentially decrease the diffusion rate.[51, 52]

3. Conclusions

A recombinant resilin-like protein (RZ10-RGD) was crosslinked with a degradable crosslinker, DTSSP. The RZ10-RGD hydrogels were highly hydrophilic and possessed a soft modulus of ~3 kPa when fully swollen. In addition, RZ10-RGD hydrogels had a well-connected network structure and, based on cryo-SEM results, had an average pore size of ~10 μm, which is on the same scale as the size of cells. NIH/3T3 fibroblasts also showed high viability when cultured on RZ10-RGD hydrogels. Another important feature of DTSSP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels was rapid degradation under reducing environments due to cleavage of the disulfide bond in DTSSP. High-molecular-weight dextran was encapsulated in RZ10-RGD hydrogels and showed significantly different release rates between reducing and non-reducing conditions. In conclusion, we illustrated the stimuli-triggered degradation and cytocompatibility of redox-responsive DTSSP-crosslinked RZ10-RGD and thus demonstrated their promise as biomaterials for tissue engineering and targeted drug delivery applications.

4. Experimental Section

Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Avantor Performance Materials (Center Valley, PA) unless stated otherwise.

Protein Expression and Purification

Large-scale protein expression and purification were performed following previously published methods with slight modification.[13] Briefly, protein expression was performed with a 10 L culture in a 14 L-capacity fermentor (BioFlo 110, New Brunswick, Enfield, CT) and induced with 2.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (EMD Chemicals, Billerica, MA). Protein purification was conducted via a combination method of salting-out and heating. A concentration of 10 (w/v)% ammonium sulfate was first used to remove undesired bacterial proteins. A final concentration of 20 (w/v)% ammonium sulfate was used to precipitate RZ10-RGD. The salted-out pellet was resuspended at a concentration of >100 mg/mL in Milli-Q water and heated at 75 – 80 °C to remove undesired impurities. Dialysis was used to remove residual salt from the salting-out method. Protein expression and purification were confirmed via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Formation of Covalently Crosslinked Protein-based Hydrogels

To assemble customized molds, a 4.5 mm diameter circular hole was punched in a 1000 μm-thick silicone sheet (McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, IL), and the sheet was placed on top of a glass slide. Lyophilized RZ10-RGD was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, MO) and mixed with a 0.2 M DTSSP solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce, Waltham, MA) in DMSO. To ensure high crosslinking efficiency, RZ10-RGD was crosslinked with excess DTSSP at a stoichiometric crosslinking ratio of 2:1 (ratio of the number of sulfo-NHS ester groups to the number of primary amine groups). The solution was immediately loaded into the silicone mold, and another silicone sheet (1000 μm-thick) was placed on top. Loaded molds were incubated at room temperature (RT) overnight. Once they were fully crosslinked, hydrogels were immersed in a 50 mM Tris solution (pH 7.5) for 15 min to quench the crosslinking reaction and then were removed from the molds. All experiments in this study were conducted with crosslinked 16 wt% RZ10-RGD hydrogels.

Swelling Ratio and Water Content Measurements

RZ10-RGD hydrogels were prepared as described above. After formation, hydrogels were immersed in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) at 37 °C and weighed every 24 h until the swollen weight equilibrated. Swollen hydrogels were rinsed with Milli-Q water (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) to remove residual salts from the PBS. Dry weights of hydrogels were measured after lyophilization. The swelling ratio (q) and water content (WC) of hydrogels were evaluated as follows: q = Ws/Wd and WC = 100 × (Ws – Wd)/Ws, where Ws and Wd are the swollen and dry weights of the hydrogels, respectively. Data are reported as an average of five replicates ± standard deviation.

Oscillatory Rheology

Rheological properties of crosslinked resilin-like hydrogels were determined with an AR2000 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) using a 20-mm diameter plate-on-plate geometry with a solvent trap. Fully swollen RZ10-RGD hydrogels were placed on the center of the bottom plate, and the top plate was then lowered to a gap distance of 1000 μm. To prevent the gel from drying during the measurements, the solvent trap was filled with Milli-Q water, and the entire setup was covered. The temperature of the bottom plate was then raised to 37 °C. After the hydrogels had equilibrated for 1 min at 37 °C, oscillatory frequency and strain sweeps were performed. Frequency sweeps were conducted from 0.1 – 100 rad/s at 1% strain, and strain sweeps were conducted from 0.1 – 100% strain at an angular frequency of 1 rad/s. Data are reported as an average of six replicates ± standard deviation.

In Vitro Degradation of Crosslinked Resilin-like Hydrogels

Fully swollen RZ10-RGD hydrogels were immersed in 5 mL of PBS or a 10 mM glutathione solution (GSH in PBS, pH 7.4) and shaken at 100 rpm and 37 °C. Degradation of hydrogels was evaluated by two methods: direct weighing of hydrogels and measuring the amount of RZ10-RGD in the supernatant.

For the direct weighing method, hydrogel weights were recorded at each preselected time point (1, 3, 8, 12, 24, and every 24 h thereafter for up to 336 hr). To determine the amount of RZ10-RGD in the supernatant, 1 mL of supernatant was collected at preselected time points and replaced with fresh buffer with or without 10 mM GSH. The RZ10-RGD concentration in the collected supernatant was measured with a Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The initial amount of crosslinked RZ10-RGD was treated as 100%. Standard curves were established with RZ10-RGD in either PBS or a 10 mM GSH solution at concentrations ranging from 0.01 – 1 mg/mL. Data are reported as an average of at least four replicates ± standard deviation for both measurements.

Cryo-scanning Electron Microscopy Imaging and Pore Size Quantification

Cryo-scanning electron microscopy (cryo-SEM) images were acquired by the Life Science Microscopy Facility (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN). Hydrogel samples were prepared as described above and immersed in PBS until fully swollen. The hydrogels were then rinsed with Milli-Q water to remove residual salts. Samples were plunged into nitrogen slush to preserve network structure. Frozen samples were fractured to reveal the cross section of the samples, and they were coated with platinum. SEM images were taken on an FEI NOVA nanoSEM field emission scanning electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) using an Everhart-Thornley (ET) detector operating at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV.

Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD)[53] was used to analyze pore sizes of RZ10-RGD hydrogels. Pore sizes were determined by averaging the lengths of the major and minor axes of each pore. Data are reported as an average of three replicates ± standard deviation, and each replicate consisted of at least 195 pores.

Cell Culture

NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (1% P/S) (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), and 10% (v/v) bovine calf serum. Cells were subcultured after reaching 65 – 80% confluence.

Cell Viability

Crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels were manufactured as a 6 mm-diameter disc with a thickness of 250 µm. After formation, hydrogels were immersed in PBS until fully swollen. Swollen RZ10 hydrogels were cut into a 7 mm-diameter disc and placed on the surface of a TCP well. A cloning cylinder (10 mm outer diameter, Corning, Corning, NY) was placed around the hydrogel to reduce culture volume. The hydrogels were sterilized with 70% ethanol for >30 min. Hydrogels were then rinsed with PBS to remove ethanol and immersed in high-glucose DMEM (with 1% penicillin-streptomycin) before cell culture.

NIH/3T3 fibroblasts were seeded on crosslinked RZ10-RGD hydrogels at a density of 200 cells/mm2. Cells cultured on TCP were used as positive controls. The viability of NIH/3T3 fibroblasts after 1 day was determined with a LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Molecular Probes L-3224, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were rinsed with high-glucose DMEM and incubated at 37 °C with high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 0.5 μM calcein (acetoxymethyl) AM and 1.5 μM ethidium homodimer-1 for 40 min. Cells were rinsed with high-glucose DMEM before imaging. Images were taken using a Nikon Ti-E microscope with a 4x objective. FITC and tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) filter cubes were used to detect calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-1 signals, respectively. The numbers of live and dead cells were determined by visual counting. Each group contained three replicates, and each replicate contained >2,500 cells. Cells treated with 70% ethanol for >30 min served as a negative control for viability.

In Vitro Release of FITC-Dextran

Various sizes of FITC-labeled dextran (average MW of 10, 20, and 150 kDa) in DMSO (2 mg/mL) were incorporated into the crosslinked resilin-like hydrogels at a concentration of 0.1 (w/v)% during hydrogel formation. The encapsulation efficiency was 78.0 ± 4.6% for 10 kDa dextran, 80.8 ± 5.3% for 20 kDa dextran, and 90.6 ± 3.4% for 150 kDa dextran.

To determine the release rate of FITC-dextran, crosslinked hydrogels were incubated in 5 mL of PBS or a 10 mM GSH solution on a rotary shaker (100 rpm) at 37 °C. One mL of supernatant was collected at pre-selected time points, and another 1 mL of fresh buffer with or without 10 mM GSH was added as a replacement. Fluorescence readings were measured on a SpectraMax M2e (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA) at 518 nm with an excitation wavelength of 492 nm and a cutoff at 515 nm. Standard curves of FITC-dextran were established that ranged from 0.005 – 10 μg/mL. The total amount of encapsulated FITC-dextran was treated as 100%. Data are reported as an average of at least three replicates ± standard deviation.

Mesh Size Estimation

Volumetric swelling ratio (Q) was calculated from the swelling ratio (q) using the following equations[54] with the density of RZ10-RGD (ρRZ10–RGD, 1.3 g/cm3)[15] and the density of PBS (ρPBS, 1.01 g/cm3)[55]:

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

Q was then used to calculate the mesh size of RZ10-RGD hydrogel with Flory-Rehner theory[46] and a Flory-Huggins interaction parameter of 0.48[56]. ρgel is the calculated density of the swollen hydrogel.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post hoc analysis was performed to organize treatments into statistically different (p < 0.05) subgroups using Minitab (State College, PA). Welch’s ANOVA coupled with a Games-Howell post hoc analysis was performed instead when groups exhibited unequal variances. ANOVA residuals were checked for normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. When there were only two groups for comparison, an unpaired two-sample Student’s t-test was performed. For all statistical tests, a significance threshold of α = 0.05 was chosen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Defense Lung Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-14–1-0012 to J.C.L.), the National Institutes of Health (NIDCR R03DE021755 to J.C.L.), and the American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (12SDG8980014 to J.C.L.). We thank Dr. Sherry Voytik-Harbin (Purdue University) for access to the rheometer and Dr. Christopher Gilpin (Life Science Microscopy Facility, Purdue University) for aid in obtaining cryo-SEM images. We appreciate the generous gift of the NIH/3T3 fibroblasts from Dr. Alyssa Panitch (Purdue University). We also thank Emily E. Gill for her help with the experiments characterizing the swelling ratios and water content of the RZ10-RGD hydrogels.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Renay S.-C. Su, Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA 47907-2100

Richard J. Galas, Jr., Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA 47907-2100

Charng-Yu Lin, Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA 47907-2100.

Julie C. Liu, Davidson School of Chemical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA 47907-2100; Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA 47907-2032

References

- 1.Li L, Charati MB, and Kiick KL, Elastomeric Polypeptide-Based Biomaterials. Polymer Chemistry, 2010. 1(8): p. 1160–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sengupta D and Heilshorn SC, Protein-engineered Biomaterials: Highly Tunable Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Tissue Engineering, Part B: Reviews, 2010. 16: p. 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMarco RL and Heilshorn SC, Multifunctional Materials through Modular Protein Engineering. Advanced Materials, 2012. 24(29): p. 3923–3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsueh Y-S, et al. , Design and Synthesis of Elastin-like Polypeptides for an Ideal Nerve Conduit in Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Materials Science and Engineering C, 2014. 38: p. 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu JS and Raucher D, Anti-tumor Efficacy of a Therapeutic Peptide Based on Thermo-responsive Elastin-like Polypeptide in Combination with Gemcitabine. Cancer Letters, 2014. 348: p. 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weis-Fogh T, A Rubber-like Protein in Insect Cuticle. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1960. 37: p. 889–907. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weis-Fogh T, Molecular Interpretation of the Elasticity of Resilin, A Rubber-like Protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1961. 3(5): p. 648–667. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weis-Fogh T, Thermodynamic Properties of Resilin, A Rubber-like Protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1961. 3(5): p. 520–531. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elvin CM, et al. , Synthesis and Properties of Crosslinked Recombinant Pro-resilin. Nature, 2005. 437: p. 999–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyons RE, et al. , Design and Facile Production of Recombinant Resilin-like Polypeptides: Gene Construction and A Rapid Protein Purification Method. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection, 2007. 20(1): p. 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons RE, et al. , Comparisions of Recombinant Resilin-like Proteins: Repetitive Domains are Sufficient to Confer Resilin-like Properties. Biomacromolecules, 2009. 10(11): p. 3009–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, et al. , Tunable Mechanical Stability and Deformation Response of A Resilin-based Elastomer. Biomacromolecules, 2011. 12(6): p. 2302–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renner JN, et al. , Characterization of Resilin-based Materials for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules, 2012. 13(11): p. 3678–3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGann CL, Akins RE, and Kiick KL, Resilin-PEG Hybrid Hydrogels Yield Degradable Elastomeric Scaffolds with Heterogeneous Microstructure. Biomacromolecules, 2016. 17(1): p. 128–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y, Gill EE, and Liu JC, Enzymatic Cross-Linking of Resilin-Based Proteins for Vascular Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules, 2016. 17(8): p. 2530–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renner JN, et al. , Modular Cloning and Protein Expression of Long, Repetitive Resilin-based Proteins. Protein Expression and Purification, 2012. 82(1): p. 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Renner JN, and Liu JC, Incorporating the BMP-2 Peptide in Genetically-engineered Biomaterials Accelerates Osteogeneic Differentiation. Biomaterials Science, 2014. 2(8): p. 1110–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y and Liu JC, Protein-engineered microenvironments can promote endothelial differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of exogenous growth factors. Biomaterials Science, 2016. 4(12): p. 1761–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang F, et al. , Bone Regeneration Using Cell-Mediated Responsive Degradable PEG-Based Scaffolds Incorporating with rhBMP-2. Biomaterials, 2013. 34(5): p. 1514–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Y-J, et al. , Redox/pH Dual Stimuli-responsive Biodegradable Nanohydrogels with Varying Responses to Dithiothreitol and Glutathione for Controlled Drug Release. Biomaterials, 2012. 33(27): p. 6570–6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuppusamy P, et al. , Noninvasive Imaging of Tumor Redox Status and Its Modification by Tissue Glutathione Levels. Cancer Research, 2002. 62(1): p. 307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li P, et al. , Bioreducible alginate-poly (ethylenimine) nanogels as an antigen-delivery system robustly enhance vaccine-elicited humoral and cellular immune responses. Journal of Controlled Release, 2013. 168(3): p. 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y-F, et al. , Disulfide-cross-linked PEG-block-polypeptide nanoparticles with high drug loading content as glutathione-triggered anticancer drug nanocarriers. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2018. 165: p. 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J and Marchant RE, Design Properties of Hydrogel Tissue-Engineering Scaffolds. Expert Review of Medical Devices, 2011. 8(5): p. 607–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Liu F, and Wei J, Hydrophilic Silicone Hydrogels with Interpenetrating Network Structure for Extended Delivery of Ophthalmic Drugs. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 2012. 23: p. 1258–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truong MY, et al. , The Effect of Hydration on Molecular Chain Mobility and the Viscoelastic Behavior of Resilin-mimetic Protein-based Hydrogels. Biomaterials, 2011. 32: p. 8462–8473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGann CL, Levenson EA, and Kiick KL, Resilin-Based Hybrid Hydrogels for Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 2013. 214(2): p. 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L and Kiick KL, Transient Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Resilin-based Elastomeric Hydrogels. Frontiers in Chemistry, 2014. 2(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, et al. , Resilin-like Polypeptide Hydrogels Engineered for Versatile Biological Function. Soft Matter, 2013. 9: p. 665–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGann CL, et al. , Thiol-ene Photocrosslinking of Cytocompatible Resilin-Like Polypeptide-PEG Hydrogels. Macromolecular Bioscience, 2016. 16: p. 129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, et al. , Recombinant Resilin-Based Bioelastomers for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 2016. 5: p. 266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Degtyar E, et al. , Recombinant Engineering of Reversible Cross-links into a Resilient Biopolymer. Polymer, 2015. 69: p. 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim DW, et al. , Rapid Cross-Linking of Elastin-Like Polypeptides with (Hydroxymethyl)phosphines in Aqueous Solution. Biomacromolecules, 2007. 8: p. 1463–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engler AJ, et al. , Myotubes Differentiate Optimally on Substrates with Tissue-Like Stiffness: Pathological Implications for Soft Or Stiff Microenvironments. The Journal of Cell Biology, 2004. 166(6): p. 877–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Min YB, Titze IR, and Alipour-Haghighi F, Stress-strain Response of the Human Vocal Ligament. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 1995. 104(7): p. 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G, et al. , Glutathione Metabolism and Its Implications For Health. Journal of Nutrition, 2004. 134(3): p. 489–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng R, et al. , Dual and Multi-Stimuli Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles for Programmed Site-Specific Drug Delivery. Biomaterials, 2013. 34: p. 3646–3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Annabi N, et al. , Controlling the Porosity and Microarchitecture of Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering: Part B, 2010. 16: p. 371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji C, et al. , Fabrication of Porous Chitosan Scaffolds for Soft Tissue Engineering Using Dense Gas CO2. Acta Biomaterialia, 2011. 7: p. 1653–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madden LR, et al. , Proangiogenic Scaffolds As Functional Templates For Cardiac Tissue Engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010. 107: p. 15211–15216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charati MB, et al. , Hydrophilic Elastomeric Biomaterials Based on Reilin-like Polypeptides. Soft Matter, 2009. 5: p. 3412–3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li L, et al. , Biocompatibility of injectable resilin-based hydrogels. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2018. 106(8): p. 2229–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bulpitt P and Aeschlimann D, New strategy for chemical modification of hyaluronic acid: Preparation of functionalized derivatives and their use in the formation of novel biocompatible hydrogels. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 1999. 47(2): p. 152–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meng F, Hennink WE, and Zhong Z, Reduction-Sensitive Polymers and Bioconjugates For Biomedical Applications. Biomaterials, 2009. 30: p. 2180–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J and Mooney DJ, Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nature Reviews Materials, 2016. 1(12): p. 16071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Canal T and Peppas NA, Correlation between mesh size and equilibrium degree of swelling of polymeric networks. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 1989. 23(10): p. 1183–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller WG, Brant DA, and Flory PJ, Random coil configurations of polypeptide copolymers. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1967. 23(1): p. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Smedt S, et al. , Structural information on hyaluronic acid solutions as studied by probe diffusion experiments. Macromolecules, 1994. 27(1): p. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Armstrong JK, et al. , The hydrodynamic radii of macromolecules and their effect on red blood cell aggregation. Biophysical Journal, 2004. 87(6): p. 4259–4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang X and Brazel CS, On the Importance and Mechanisms of Burst Release in Matrix-Controlled Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Controlled Release, 2001. 73: p. 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel RA and Rathbone MJ, Overview Of Controlled Released Mechanisms, in Fundamentals And Applications Of Controlled Released Drug Delivery, Siepmann J, Siegel RA, and Rathbone MJ, Editors. 2012, Springer US: New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertz A, et al. , Encapsulation of Proteins in Hydrogel Carrier Systems for Controlled Drug Delivery: Influence of Network Structure and Drug Size on Release Rate. Journal of Biotechnology, 2013. 163: p. 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, and Eliceiri KW, NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nature Methods, 2012. 9: p. 671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee S, Tong X, and Yang F, The effects of varying poly (ethylene glycol) hydrogel crosslinking density and the crosslinking mechanism on protein accumulation in three-dimensional hydrogels. Acta Biomaterialia, 2014. 10(10): p. 4167–4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beamish JA, et al. , The effects of monoacrylated poly (ethylene glycol) on the properties of poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels used for tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A, 2010. 92(2): p. 441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Truong MY, et al. , The effect of hydration on molecular chain mobility and the viscoelastic behavior of resilin-mimetic protein-based hydrogels. Biomaterials, 2011. 32(33): p. 8462–8473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.