Abstract

Spindle cell oncocytomas (SCO) of the pituitary are rare tumors accounting for 0.1–0.4% of all sellar tumors. Due to their rarity, little information is available regarding their pathogenesis. Our aim was to investigate miRNA expression profile of pituitary oncocytomas. Total RNA was extracted from 9 formalin-fixed paraffin embedded pituitary samples (4 primary, 3 recurrent oncocytomas and 2 normal tissues). Next-generation sequencing was performed for miRNA profiling. Transcriptome data of additional 6 samples’ were obtained from NBCI GEO database for gene expression reanalysis and tissue-specific target prediction. Bioinformatical analysis, in vitro miRNA mimics transfection, luciferase reporter system and AlamarBlue assay were applied to characterize miRNA’s function. 54 differentially expressed miRNAs and 485 genes in pituitary SCO vs. normal tissue and 8 miRNAs in recurrent vs. primary SCO were determined. Global miRNA downregulation and decreased level of DROSHA were detected in SCO samples vs. normal tissue. Transcriptome analysis revealed cell cycle alterations while miRNAs influenced mainly metabolic processes (tricarboxylic acid cycle-TCA, carbohydrate, lipid metabolism). Through miRNA-target interaction network the overexpressed Aconitase 2 potentially targeted by two downregulated miRNAs (miR-744-5p, miR-127-3p) was revealed. ACO2 and miR-744-5p interaction was validated by luciferase assay. MiR-127-3p and miR-744-5p significantly decreased cell proliferation in vitro. Our study firstly reported miRNA profile of pituitary oncocytoma. Our results suggest that tumor suppressor miRNAs may have an essential role in the pathogenesis of pituitary oncocytoma. Earlier reports showed downregulated TCA cycle in SCO which is extended by our results adding the role of miR-744-5p targeting ACO2.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11064-019-02789-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pituitary adenoma, Oncocytoma, miRNA, Biomarker, Next generation sequencing

Introduction

Prevalence rate of primary tumors of the anterior pituitary varies 10–22% of all intracranial tumors, however, clinically relevant pituitary adenomas appear more rarely [1, 2]. Adenomas of the anterior pituitary are the most common tumor type in the sellar region followed by craniopharyngioma, meningioma and posterior pituitary tumors (PPT) [3]. Based on the WHO 2017 classification, the main tumors of neurohypophysis are pituicytomas, granular cell tumors, spindle cell oncocytomas (SCO) and sellar ependymomas. According to the current hypothesis, PPTs originate from specific morphological variants of pituicytes (specialized glial cells, i.e. pituicytomas from the light/major variant, granular cell tumors from the granular variant, spindle cell oncocytomas from the oncocytic variant and sellar ependymomas from the ependymal pituicytes) [4]. PPTs show a common immunohistochemical feature, diffuse nuclear expression for the thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), a homeobox transcription factor [4]. Spindle cell oncocytomas (SCO or oncocytomas) are rare, benign tumors accounting for 0.1–0.4% of all sellar tumors [5]. Until mid-2017, there have been only 34 cases published [3]. Although some hormonally active oncocytomas have been described [6, 7], PPTs are low-grade, non-neuroendocrine neoplasms clinically presenting with symptoms related to mass effects [4, 8, 9].

Due to its rarity, little information is available regarding the pathogenesis of SCO. Exome sequencing confirmed low genomic mutation rate and a neutral copy-number profile [10]. Enhanced MAPK activity was confirmed by strong phospho-ERK staining (n = 4) [10]. In addition, SCOs are characterized by accumulation of mitochondria in the cytoplasm revealed by ultrastructure analysis [11]. Indeed, mitochondrial Complex I disruptive variants in pituitary oncocytomas were described as somatic modifiers of tumorigenesis most likely contributing not only to the development of oncocytic change but also to a less aggressive tumor phenotype [12]. However Complex I mutations lead to dysfunctional respiratory function, Carelli et al. described that Complex I mutations themselves were not sufficient for mitochondrial proliferation [13].

Proteomic analysis showed that 14-3-3η was overexpressed in oncocytomas, and inhibited lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) through direct interaction [14]. In line with this, the authors detected disrupted glycolysis and decreased level of lactate together with reduced expression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in pituitary oncocytoma tissue specimens by metabolic analysis (NanoLC-MS/MS) [14]. However, hypoxia-response signaling pathway was not upregulated in pituitary oncocytomas, thereby failing to enhance glycolysis [14]. Thus, 14-3-3η was capable of inhibiting glycolysis, which together with dysfunctional mitochondria resulted in an increased mitochondrial biogenesis [14].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small regulatory RNAs that have an important role in elementary biological processes, such as cell proliferation, cell differentiation and cell death. Correlation between miRNAs and cancer and abnormal expression of miRNAs have been shown in a variety of tumor tissues including pituitary adenomas [14–17]. By regulating their target genes expression, miRNAs can play either oncogenic or tumor suppressor functions [17].

Herein, for the first time, we investigated miRNA expression profile of pituitary oncocytomas and evaluated the role of differentially expressed miRNAs by complex bioinformatical approaches.

Methods

Patients and Samples

Nine formalin fixed paraffin embedded pituitary samples (4 primary oncocytomas, 3 recurrent oncocytomas and 2 normal tissues) from the archive of the 1st Department of Pathology and Experimental Cancer Research, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary were studied (Table 1). The adjacent non-tumorous tissue of 2 pituitary oncocytoma cases were macrodissected and used as normal control. Pituitary oncocytomas were surgically removed at the National Institute of Clinical Neurosciences between 2009 and 2018. The study was approved by the Scientific and Research Committee of the Medical Research Council of Hungary (0618/15).

Table 1.

Patient and sample characteristics

| Experiment | Sample ID | Sex | Age | Ki-67 proliferation index | Immunostaining positivity | Histological diagnosis | Tumor type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA seq | 1 | M | 48 | 5% | TTF-1, Annexin, S100, EMA, CD63 | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Primary |

| miRNA seq | 2 | Normal | |||||

| miRNA seq | 3 | F | 68 | 5–8% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3, S100, EMA, CD63 | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Primary |

| miRNA seq | 4 | M | 69 | < 5% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3 | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Primary |

| miRNA seq | 5 | M | 43 | 1.5% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3, S100, EMA | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Primary |

| miRNA seq | 6 | M | 44 | 5% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3, S100, EMA | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Recurrent 1 |

| miRNA seq | 7 | M | 49 | 4–8% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3, S100, EMA | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Recurrent 2 |

| miRNA seq | 8 | Normal | |||||

| miRNA seq | 9 | M | 52 | 4–8% | TTF-1, Annexin, Gal-3, S100, EMA | Spindle cell oncocytoma | Recurrent 3 |

| GSE51618 | |||||||

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249410 | M | NA | 4% | NA | Non-invasive pituitary oncocytoma | NA |

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249411 | M | NA | 1% | NA | Non-invasive pituitary oncocytoma | NA |

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249413 | M | NA | 2% | NA | Non-invasive pituitary oncocytoma | NA |

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249421 | M | NA | Normal | |||

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249425 | M | NA | Normal | |||

| Transcriptome data | GSM1249423 | F | NA | Normal | |||

Additional six samples’ transcriptome data were obtained from NBCI GEO database (GSE51618) for gene expression reanalysis and for tissue specific target prediction (Table 1).

RNA Extraction and miRNA Expression Profile by Next-Generation Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from FFPE samples using the RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (AM1975, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

For miRNA sequencing, libraries were prepared using 5 μl RNA and the QIAseq™ miRNA Library Kit (Cat#331505, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All procedures were done as previously described [18]. Briefly, following adapter ligation first at 3′ then at 5′ end of miRNAs universal reverse-transcription was performed on each sample. RT primers contained the Unique Molecular Indexes (UMIs) as well. cDNA was cleaned up using magnetic beads included in the library preparation kit. Next-generation sequencing was run on Illumina MiSeq instrument using MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 150-cycle (MS-102-3001, Illumina, San Diego, USA).

After sequencing primary data analysis was performed on FASTQ files using Qiagen GeneGlobe Data Analysis Center. Raw reads were processed by trimming off the 3′ adapter and low quality bases using cutadapt (http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/guide.html). Following trimming, insert sequences and UMI sequences were identified. Then sequences were aligned to miRBase v21 mature miRNA sequences using bowtie algorithm (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml). For each sample all reads assigned to a particular miRNA ID was counted and the associated UMIs were clustered to count unique molecules. UMI read counts were used to calculate differential expression. Reads were normalized by TMM and by GeNorm [19, 20]. For further analysis miRNAs were selected if both normalization method yielded significantly different expression among groups by ANOVA combined with Fisher post hoc test.

Analysis of Transcriptome Data

Transcriptome data of 3 pituitary oncocytoma and 3 normal pituitary tissue were obtained from NBCI GEO Database (GSE51618) measured on Agilent-014850 Whole Human Genome Microarray 4x44K G4112F platform. Data analysis was performed by Genespring GX 14.9 Software (Agilent Tech Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Raw data were filtered by percentile (lower cut-off: 20). Fold change filter was set to twofold, and then unpaired t-test was used to identify significant gene expression changes (p < 0.05) with multiple testing correction (Benjamini–Hochberg) to control the false discovery rate (FDR) and to get statistically reliable results.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Tissue specific target prediction was performed using significantly differentially expressed miRNA and mRNA lists. Target prediction was performed by TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) and miRecords (http://c1.accurascience.com/miRecords/). For further filtering miRNA-target pairs were included if opposite expressional change was detected by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis microRNA Target Filter (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/features/microrna-target-filter/). Pathway and Gene ontology analysis were performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), ToPPFun (https://toppgene.cchmc.org/enrichment.jsp) and Panther Classification System (http://www.pantherdb.org/). Gene Ontology term summarizing and removal of redundant GO terms were performed by Revigo (reduce and visualize gene ontology; http://revigo.irb.hr/). For functional analysis and annotation clustering of GO terms DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 was applied. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Luciferase Reporter Vector Construction

ACO2 3′-UTR (ENST00000216254.8) was amplified by PCR from genomic human DNA using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-CCATCCTCCTGAACCACACC-3′ forward and 5′-GCCTCCACTGACCTTGACTG-3′ reverse primers. The amplified sequence was cloned (5′ → 3′) into pGL3 Control vector (Promega, Madison, WI) at the 3′ end of the firefly luciferase gene at XbaI restriction site (pACO2). pGL3 Control vector was used as negative control.

Transfection, Dual-Luciferase Assay, Proliferation Assay

HeLa cells were plated at 104 cells per well in 96-well plates on the day before transfection. Cells were cotransfected with pACO2 [75 ng pACO2 firefly vector or negative control together with 75 ng renilla (pRL-Promega) vector] and miRNA mimics [30 nM any of miR-744-5p, miR-127-3p mirVana™ miRNA Mimics (ID: MC13027, MC10400) or with Non-targeting Control miRNA mimic #1 (4464058, Thermofisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA) using PANFect A-plus Transfection Reagent (P02-8110, PAN Biotech)]. Luciferase assay was performed 24 h later using Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (E2920, Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Firefly luciferase activity was adjusted for transfection efficiency by normalizing to renilla luciferase activity of each sample. For investigating cell proliferation HeLa and H295R cells were transfected with 30 nM miRNA mimics using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (13778030, Thermofisher Scientific). After 24 h cell proliferation was measured by AlamarBlue reagent (DAL1025, Thermofisher Scientific) on Varioskan™ Flash Multimode Reader (Thermofisher Scientific).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis at the 1st Department of Pathology and Experimental Cancer Research, Semmelweis University. 4 µm-thick sections were cut and mounted on SuperFrost/Plus slides and stored at 4 °C until the staining. Slides were deparaffinised, rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidases were inhibited with 10% H 2 O 2 for 20 min in methanol. Antigen retrieval was achieved by incubating slides at 100 °C in TRS (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH = 9) for 3 min. Staining was performed using the Novolink Polymer Detection System (Peroxidase/DAB+, Rabbit, Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK). Non-specific binding was blocked for 10 min at room temperature (RT) using Novocastra™ Protein Block. 0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS was applied (15 min, RT). Slides were then incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-Drosha (ab12286, 1:100) overnight at 4 °C. Subsequently, the rabbit Novolink Polymer was applied for 30 min at RT. The primary antibody binding to tissue sections were visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Novolink Kit, 1:20) for 4 min, and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Results

Global Downregulation of miRNA Expression in Pituitary Oncocytoma

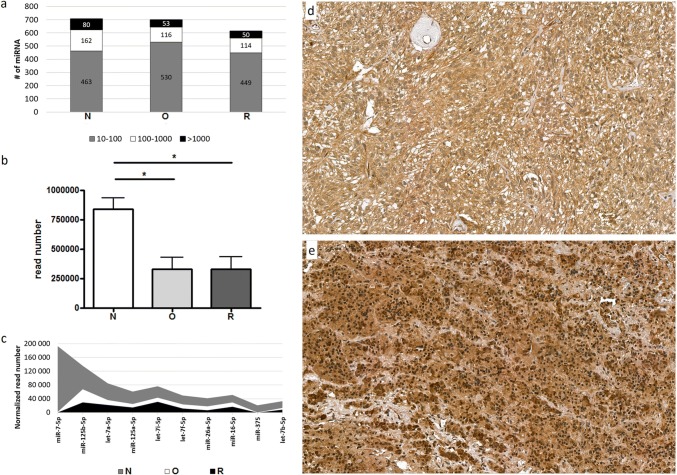

Altogether 4,000,965 reads were generated, with an average of 889,103 reads/sample. More than half of the miRNAs were in low expression range between 10 and 100 reads. 23%, 17% and 19% of the miRNAs were between 100 and 1000 read and only 11%, 8% and 8% of the miRNAs appeared in the highest expression range (> 1000 reads) in the normal, oncocytoma and recurrent oncocytoma groups, respectively (Fig. 1a). We found global miRNA downregulation in oncocytoma vs. normal and assessing the most abundant 10 miRNAs showed lower expression in the oncocytoma and recurrent oncocytoma groups compared to the normal tissue as well (Fig. 1b, c). Investigating the mechanism behind miRNA downregulation we found lower expression of DROSHA (Drosha Ribonuclease III) on mRNA level. In a pilot experiment we detected decreased DROSHA protein level in sample where adjacent normal tissue was available (Fig. 1d, e). Additionally, 40% of downregulated miRNAs were located on chromosome 14 at 14q32 region. Whole miRNA profile was able to discriminate pituitary oncocytomas from normal tissue (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 1.

a miRNAs expressed in pituitary oncocytoma, recurrent oncocytoma and normal tissue in different expressional ranges. Grey represents the number of miRNA expressed in low range (between 10 and 100 normalized reads), white represents the number of miRNA expressed in middle range (between 100 and 1000 normalized reads) and black represents the number of strongly expressed miRNAs (> 1000 normalized reads). b Overall miRNA read numbers in normal pituitary, onocytoma and recurrent oncocytoma. *p < 0.05. c Ten most abundant miRNAs expression in pituitary oncocytoma (white), recurrent oncocytoma (black) and normal tissue (grey). DROSHA immunostaining in d Oncocytoma and e normal pituitary. By CaseViewer v2.1 software (3DHISTECH Ltd.) quantification strong staining appeared in 21% in oncocytoma and 41% of normal pituitary. N normal pituitary, O spindle cell onocytoma and R recurrent oncocytoma

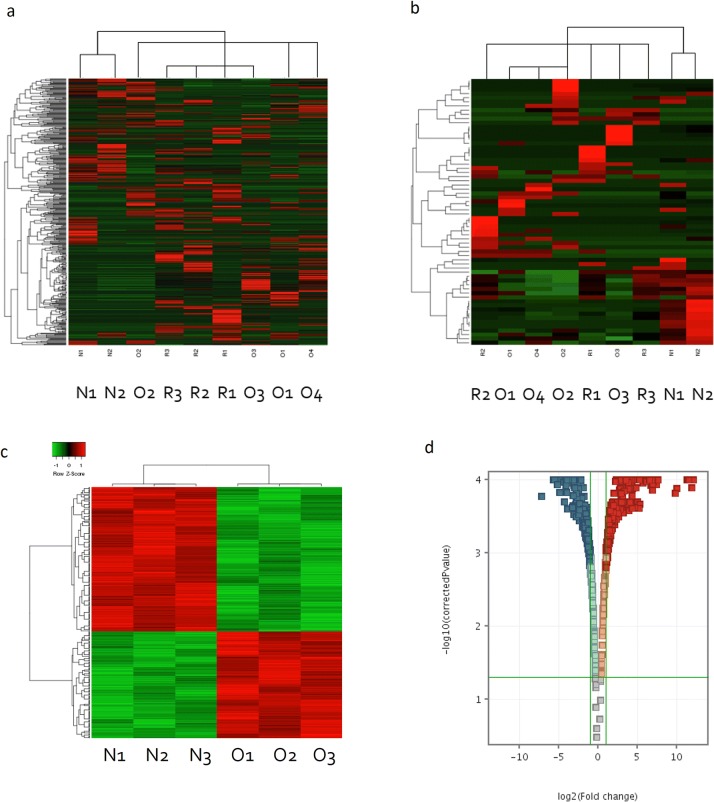

Fig. 2.

a Whole miRNA expression profile differentiate pituitary oncocytoma, recurrent oncocytoma and normal tissue. b Significant miRNAs between pituitary oncocytoma, recurrent oncocytoma and normal tissue. c Pituitary oncocytoma and normal pituitary samples were separated by gene expression profile. d Significant differentially expressed genes in pituitary oncocytoma compared to normal tissue (with a fold change cut-off:2 and p < 0.05 after FDR adjustment). N normal pituitary, O spindle cell onocytoma, R recurrent oncocytoma

Tissue Specific Target Prediction Using Pituitary Oncocytoma Transcriptome Data Revealed the Role of miRNAs in Metabolic Process

We identified 54 differentially expressed miRNAs in pituitary oncocytoma compared to normal tissue and 8 miRNA in recurrent oncocytomas vs. primary tumor (Fig. 2b, Online Resource 1).

By reanalysing mRNA expression data, 485 differentially expressed genes were identified (Fig. 2c, d). The most significant pathway affected by these genes was “cell cycle” (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pathway analysis of pituitary oncocytoma transcriptome

| Database | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | DAVID | TOPPFUN | |||

| Pathway | p-value | Pathway | p-value | Pathway | p-value |

| CELL CYCLE: G1/S | 0.0025 | PI3K-AKT SIGNALING PATHWAY (Kegg Pathway) | 0.005 | GROWTH HORMONE SIGNALING | 0.000002 |

| CELL CYCLE: G2/M | 0.0027 | CELL CYCLE: G1/S (Biocarta Pathway) | 0.016 | ||

| GROWTH HORMONE SIGNALING | 0.0027 | RAP1 SIGNALING PATHWAY (Kegg Pathway) | 0.026 | ||

| CELL CYCLE REGULATIONS | 0.816 | CELL CYCLE REGULATION (Biocarta Pathway) | 0.076 | ||

Next, we performed miRNA target prediction using TargetScan and miRecords databases. For further analysis we included miRNA-mRNA pairs only when additionally to the positive target prediction miRNA and its target showed opposite expression pattern in pituitary oncocytoma vs. normal tissue.

Pathway analysis among others showed “Tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle)” and “Cell cycle” pathways altered by miRNAs (Online Resource 2).

Performing Gene Ontology (GO) analysis „Cellular Process” and „Metabolic process” were the most significant biological processes influenced by miRNAs (Online Resource 3, 4). After summarizing and removing the redundant GO terms “cholesterol metabolism”, “mitochondrial transport”, “acetyltransferase activity” and “cation transmembrane transporter activity” were the most important GO terms (Online Resource 5a, b). Metabolism related Biological Processes were also enriched in miRNA regulated genes (Table 3). By functional annotation clustering we identified a Metabolism and a Mitochondria related gene cluster influenced by miRNAs (Online Resource 5c, d). Using these gene clusters we constructed a miRNA-target interaction network in order to visualize miRNAs’ role in oncocytoma metabolism and mitochondrial function (Fig. 3a, b).

Table 3.

Metabolism related Biological Processes influenced by miRNAs differentially expressed in pituitary oncocytomas

| Term | Gene count | Genes | Fold enrichment | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0006664~glycolipid metabolic process | 5 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, ST8SIA5, CLN6 | 13.1763967 | 0.0005202 |

| GO:1903509~lipopolysaccharide metabolic process | 5 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, ST8SIA5, CLN6 | 12.8497092 | 0.00057189 |

| GO:0009247~glycolipid biosynthetic process | 4 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, ST8SIA5 | 18.564953 | 0.00123325 |

| GO:0006643~membrane lipid metabolic process | 5 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, ST8SIA5, CLN6 | 7.62164125 | 0.00389079 |

| GO:0046467~membrane lipid biosynthetic process | 4 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, ST8SIA5 | 9.01341922 | 0.00942844 |

| GO:0044262~cellular carbohydrate metabolic process | 5 | GAL3ST3, CLK2, INPP5E, PPP1CC, CALM1 | 5.73732404 | 0.01045816 |

| GO:0044255~cellular lipid metabolic process | 9 | GAL3ST3, PTK2, PIGY, PIGH, PRKAB2, ST8SIA5, INPP5E, CRAT, CLN6 | 2.68328539 | 0.01584233 |

| GO:0044264~cellular polysaccharide metabolic process | 3 | GAL3ST3, PPP1CC, CALM1 | 9.51927438 | 0.03831898 |

| GO:0008610~lipid biosynthetic process | 6 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, PRKAB2, ST8SIA5, INPP5E | 2.99002849 | 0.046311 |

| GO:0005976~polysaccharide metabolic process | 3 | GAL3ST3, PPP1CC, CALM1 | 8.04214559 | 0.05189019 |

| GO:0044723~single-organism carbohydrate metabolic process | 6 | GAL3ST3, CLK2, ST8SIA5, INPP5E, PPP1CC, CALM1 | 2.84417344 | 0.05523079 |

| GO:0006629~lipid metabolic process | 9 | GAL3ST3, PTK2, PIGY, PIGH, PRKAB2, ST8SIA5, INPP5E, CRAT, CLN6 | 2.10426065 | 0.05563828 |

| GO:0019538~protein metabolic process | 24 | BCKDK, PIGY, L3MBTL2, PRKAB2, PKN2, NDFIP1, HMG20A, UBE2C, KAT5, PPP1CC, CAMK2N1, CCNB1, URM1, PTK2, POLE4, HIF1AN, CLK2, PIGH, ST8SIA5, USP35, FBXL14, GFRA2, CALM1, CLN6 | 1.36762161 | 0.0628948 |

| GO:1901137~carbohydrate derivative biosynthetic process | 6 | GAL3ST3, PIGY, PIGH, DTYMK, ST8SIA5, CALM1 | 2.46796002 | 0.08915693 |

| GO:0010563~negative regulation of phosphorus metabolic process | 5 | CCNB1, UBE2C, CAMK2N1, GFRA2, CALM1 | 2.85811547 | 0.09220633 |

| GO:0045936~negative regulation of phosphate metabolic process | 5 | CCNB1, UBE2C, CAMK2N1, GFRA2, CALM1 | 2.85811547 | 0.09220633 |

| GO:0006796~phosphate-containing compound metabolic process | 15 | BCKDK, PIGY, PRKAB2, DTYMK, PKN2, UBE2C, PPP1CC, CAMK2N1, CCNB1, PTK2, CLK2, PIGH, INPP5E, GFRA2, CALM1 | 1.51295636 | 0.09396383 |

| GO:0006793~phosphorus metabolic process | 15 | BCKDK, PIGY, PRKAB2, DTYMK, PKN2, UBE2C, PPP1CC, CAMK2N1, CCNB1, PTK2, CLK2, PIGH, INPP5E, GFRA2, CALM1 | 1.51001763 | 0.09515533 |

| GO:0005975~carbohydrate metabolic process | 6 | GAL3ST3, CLK2, ST8SIA5, INPP5E, PPP1CC, CALM1 | 2.39817195 | 0.09782965 |

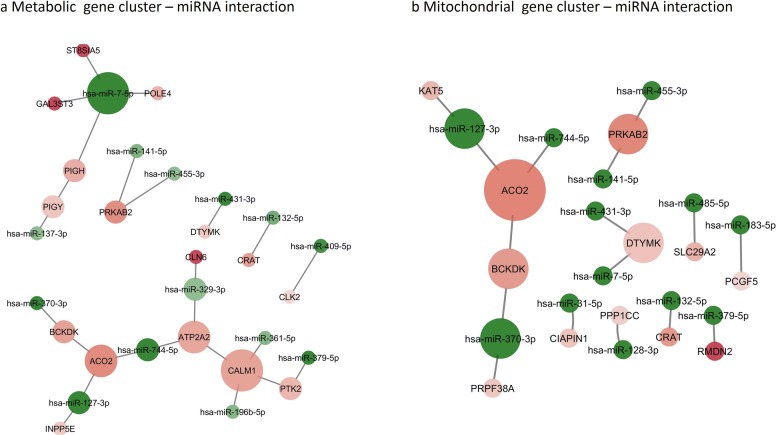

Fig. 3.

miRNA-target interaction network of oncocytoma on “Metabolic” gene cluster (a) and “Mitochondrial” gene cluster (b). Node size indicates interaction number, node color shades indicates expression (green: significant downregulation, red: significant upregulation; bright color represents higher fold change, faint color represents lower fold change) (Color figure online)

We found that mitochondrial Aconitase 2 (ACO2) was upregulated significantly (fold change 2.78, p < 0.01) in pituitary oncocytoma compared to normal tissue on mRNA level. Additionally, miR-744-5p and miR-127-3p, two miRNAs targeting ACO2 showed significant downregulation (miR-744-5p: fold change 0.20; p = 0.01 and miR-127-3p, fold change: 0.05; p < 0.01).

In vitro investigation of the function of miR-127-3p and miR-744-5p

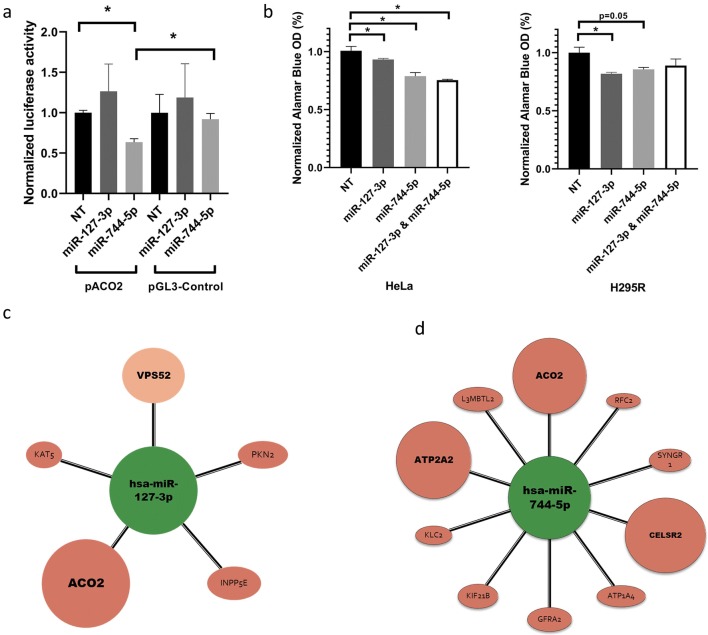

For validating miRNA-ACO2 interaction we constructed an ACO2 3′UTR firefly luciferase vector (pACO2). After co-transfection of pACO2 (with pRL-TK renilla luciferase vector for normalizing to transfection efficiency) and any of miR-127-3p, miR-744-5p or non-targeting control (NT) miRNA mimics, significantly reduced luciferase activity was detected after miR-744-5p but not after miR-127-3p transfection (Fig. 4a). For further investigation of the role of miR-127-3p and miR-744-5p HeLa and H295R cells were transfected with miRNA mimics. After 24 h posttransfection significant decrease in cell proliferation was detected (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

a Validation of Aconitase 2 (ACO2)—miRNA interaction by luciferase reporter system. Upon miR-744-5p mimics—pACO2 co-transfection relative luciferase activity decreased to 63% (p < 0.05) compared to non-targeting (NT) mimics. Additionally, miRNA mimics had no significant effect on the expression of pGL3 control vector. Normalized luciferase activity was calculated after normalizing firefly luciferase activity (pACO2) to renilla luciferase (pRL-TK) activity. Renilla vector is used to normalize between samples and to correct for transfection efficiency. b miRNA mimics effect on cell proliferation. Cell growth was decreased to 94%, 84%, 75% in HeLa and to 83%, 88%, 89% in H295R cells after miR-127-3p, miR-744-5p and miR-127-3p + miR-744-5p transfections, respectively. c miR-127-3p and d miR-744-5p targets based on tissue specific target prediction. Colors indicates significant gene expression alteration in oncocytoma vs. normal tissue (red: overexpression, green: underexpression) (Color figure online)

Discussion

MiRNA and transcriptome profiles of pituitary oncocytomas clearly separated the tumors either from normal tissue or recurrent oncocytoma samples suggesting that these expression profiles are cell type specific. Global downregulation of miRNA expression was detected in SCO and recurrent SCO vs. normal tissue. In a pilot experiment by immunohistochemistry on a slide where both oncocytoma and adjacent normal tissue was available decreased level of DROSHA was detected in oncocytoma compared to normal tissue. However, due to the low sample number, this has to be validated on en extended sample set. Additionally, by investigating the chromosomal localisation of downregulated miRNA regions, 40% of downregulated miRNAs were identified to be located on chromosome 14 at 14q32 (DLK-MEG3) locus. This region has been frequently detected as hypermethylated in tumors including pituitary adenomas [21].

Interestingly, pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes in oncocytomas revealed mainly cell cycle alterations while miRNAs rather influenced metabolic processes. Both carbohydrate (mainly tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle) and lipid metabolism were influenced by miRNAs. Cholesterol metabolism, mitochondrial transport, acetyltransferase activity and cation transmembrane transporter activity were the most significantly dysregulated gene processes and functions where miRNA targets were enriched. After functional annotation clustering we identified a metabolic and a mitochondrial gene cluster.

Because mitochondrial dysfunction by Complex I variants have a major role in oncocytoma pathogenesis, we suggest a central role of miRNAs-mitochondrial Aconitase 2 (ACO2) interaction in both the metabolic and the mitochondrial gene cluster. ACO2 was overexpressed in oncocytomas compared to normal tissue. ACO2 participates in the TCA cycle and the mitochondrial respiratory complexes (Complexes I, II, and III), which facilitate electron transport [22]. It catalyses the interconversion of citrate to isocitrate via cis-aconitate during the second step of the TCA cycle. When the ACO2 were partially silenced, less efficient entrance to the S phase was observed in human fibroblast cells and it resulted in significant impairment of DNA synthesis [23]. Unfortunately, a specific mechanism has not been identified which would clarify the exact role of enzymes participating in glycolysis and TCA cycle on regulation of DNA replication. It seems though, that these metabolic pathways and the control of cell cycle, particularly DNA synthesis, are linked [23]. Germline ACO2 mutations have been described in optic neuropathy with encephalopathy and cerebellar atrophy, and in infantile cerebellar-retinal degeneration [24, 25].

It has been described that hypoxia through HIF-1α upregulated ACO2 and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) [26, 27]. Interestingly, in pituitary oncocytoma HIF-1α signalling pathway was not upregulated which is in line with low lactate and LDHA levels [14]. Therefore the cause of ACO2 upregulation should be different in SCO. Our results suggest that downregulated miRNAs have a role in ACO2 overexpression. In literature there was no experimentally confirmed miRNA-ACO2 interaction yet although hypoxia inducible miR-210 inhibited ACO2 activity through downregulation of biogenesis and integrity of iron–sulfur cluster assembly protein (ISCU) [28]. In this current work we validated ACO2 as a target of miR-744-5p by luciferase reporter system. Additionally, both miR-127-3p and miR-744-5p significantly decreased cell proliferation in two independent human cell lines that may suggest their “general tumor suppressor role”. Both on pACO2 activity and cell proliferation the two miRNAs moderate (~ 20%, but significant) effect refers to fine-tuning regulation, a characteristic feature of miRNA activity. We concluded that the tumor suppressor role of miR-127-3p and miR-744-5p can be mediated at least partly through regulation of ACO2.

In addition to targeting ACO2 in pituitary oncocytoma, miR-127-3p was downregulated in gonadotroph pituitary adenomas and glioblastomas too [29, 30]. It has tumor suppressor effect via inhibiting proliferation by targeting KMT5a (Histone-Lysine N-Methyltransferase KMT5A) and ITGA6 (Integrin, Alpha 6) [31, 32]. In pituitary oncocytoma, we found that miR-127-3p by targeting Protein Kinase 2 (PKN2) and Inositol Polyphosphate-5-Phosphatase E (INPP5E) also regulated cell proliferation [33, 34] (Fig. 4c).

Downregulation of miR-744-5p has been described in several tumors including growth hormone (GH) secreting pituitary adenoma, pancreas, ovarian and head-and-neck cancer as well [35, 36]. Its tumor suppressor role was demonstrated by targeting MAP2K4 and BCL2 [35, 37]. In pituitary oncocytoma miR-744-5p also targets ATP1A4 that is involved in carbohydrate metabolism indirectly through participating in carbohydrate digestion and absorption pathway (Fig. 4d). GFRA2 is another overexpressed target of miR-744-5p in SCO. GFRA2 stands for Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) Family Receptor Alpha 2 that is a neurotrophic factor playing key role in the control of neuron survival and differentiation.

Unfortunately, pituitary oncocytomas are extremely rare and there is no available in vitro (cell line) or in vivo (animal) model for this tumor type. Therefore it is not possible to validate the real functional effects of ACO2 overexpression and its targeting miRNAs exactly. However, mRNA and miRNA expression profiles are highly characteristic to each cell type, our data and bioinformatical associations extend the previously described metabolic alterations described in pituitary SCOs and add miRNAs as important players in this pathway.

In summary, our study is the first reporting miRNA expression profile of pituitary oncocytoma. Based on our data we propose that potentially primary changes in miRNA profile may have an important role in shaping the gene expression profile characteristic for oncocytomas. Bioinformatics analysis showed that miRNAs influence cell proliferation, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism that extends earlier reports showing downregulated TCA cycle and enhancement of pentose phosphate and phospholipid synthesis based on tissue metabolome analysis. We propose the central role of miR-744-5p targeting ACO2 in the regulation of TCA cycle in SCO. As previous reports described that Complex I mutations themselves were not sufficient for mitochondrial proliferation we concluded that differentially expressed miRNAs in pituitary oncocytoma have a supplementary role in tumorigenesis and mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolism.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 222 kb) Online Resource 1 Differentially expressed miRNAs in primary and recurrent spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary

Supplementary material 2 (PDF 98 kb) Online Resource 2 Pathway analysis of miRNA regulated genes in pituitary oncocytoma vs. normal tissue by Panther Classification System

Supplementary material 3 (PDF 120 kb) Online Resource 3 Gene Ontology (a Biological Process; b Molecular Function) analysis of significant differentially expressed genes influenced by differentially expressed miRNAs in oncocytoma vs. normal tissue

Supplementary material 4 (PDF 98 kb) Online Resource 4 miRNA regulated genes associated with Cellular and Metabolic process GO terms

Supplementary material 5 (PDF 790 kb) Online Resource 5 a Functional analysis of differentially expressed miRNA in oncocytoma. a GO Biological Process representative term summary after removal of redundant terms. b GO Molecular Function representative term summary after removal of redundant terms. c Metabolic gene cluster identified by GO term Functional annotation. d Mitochondrial gene cluster identified by GO term Functional annotation

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Semmelweis University (SE).

Funding

This work has been funded by Hungarian Scientific Research Grant of National Research, Development and Innovation Office (OTKA PD116093), Semmelweis Research-Innovation Fund (STIA-KF-17) to Henriett Butz and by National Excellence Program to Attila Patócs. Henriett Butz is a recipient of Bolyai Research Fellowship of Hungarian Academy of Sciences and New National Excellence Program of The Ministry of Human Capacities (ÚNKP-18-4-SE-8).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Special issue in honor of Professor Vera Adam-Vizi.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Caimari F, Korbonits M. Novel genetic causes of pituitary adenomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5030–5042. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, et al. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review. Cancer. 2004;101:613–619. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osman M, Wild A. Spindle cell oncocytoma of the anterior pituitary presenting with an acute clinical course due to intraventricular hemorrhage. a case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:894–901. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.903702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mete O, Lopes MB. Overview of the 2017 WHO classification of pituitary tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2017;28:228–243. doi: 10.1007/s12022-017-9498-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matyja E, Maksymowicz M, Grajkowska W, et al. Spindle cell oncocytoma of the adenohypophysis—a clinicopathological and ultrastructural study of two cases. Folia Neuropathol. 2010;48:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg MK, Bharwaj R, Pathak HC, et al. Pituitary oncocytoma presenting as Cushing’s disease. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:759. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.113778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue R, Aoki M, Matsumoto Y, et al. Prolactin-producing pituitary adenoma with atypical spindle cell morphology: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:229. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0655-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covington MF, Chin SS, Osborn AG. Pituicytoma, spindle cell oncocytoma, and granular cell tumor: clarification and meta-analysis of the world literature since 1893. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:2067–2072. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrero-Pérez F, Vidal N, Marengo AP, et al. Posterior pituitary tumours: the spectrum of a unique entity. A clinical and histological study of a large case series. Endocrine. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1774-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MB, Bi WL, Ramkissoon LA, et al. MAPK activation and HRAS mutation identified in pituitary spindle cell oncocytoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37054–37063. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goebel HH, Schulz F, Rama B. Ultrastructurally abnormal mitochondria in the pituitary oncocytoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1980;51:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF01406745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurelac I, MacKay A, Lambros MBK, et al. Somatic complex I disruptive mitochondrial DNA mutations are modifiers of tumorigenesis that correlate with low genomic instability in pituitary adenomas. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:226–238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carelli V, Maresca A, Caporali L, et al. Mitochondria: biogenesis and mitophagy balance in segregation and clonal expansion of mitochondrial DNA mutations. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;63:21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Y, Mao Z-G, Wang X, et al. MicroRNAs and target genes in pituitary adenomas. Horm Metab Res. 2018;50:179–192. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottoni A, Zatelli MC, Ferracin M, et al. Identification of differentially expressed microRNAs by microarray: a possible role for microRNA genes in pituitary adenomas. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:370–377. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butz H, Likó I, Czirják S, et al. MicroRNA profile indicates downregulation of the TGFβ pathway in sporadic non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Pituitary. 2011;14:112–124. doi: 10.1007/s11102-010-0268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes J, Peruzzi PP, Lawler S. MicroRNAs in cancer: biomarkers, functions and therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decmann A, Perge P, Nyíro G, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling in adrenal myelolipoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;1:1. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarlet D, Ertl R, Aurich C, Steinborn R. The orthology clause in the next generation sequencing era: novel reference genes identified by RNA-seq in humans improve normalization of neonatal equine ovary RT-qPCR data. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0142122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tam S, Tsao M-S, McPherson JD. Optimization of miRNA-seq data preprocessing. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16:950–963. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheunsuchon P, Zhou Y, Zhang X, et al. Silencing of the imprinted DLK1-MEG3 locus in human clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2120–2130. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rouault TA, Tong WH. Iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis and human disease. Trends Genet. 2008;24:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konieczna A, Szczepańska A, Sawiuk K, et al. Effects of partial silencing of genes coding for enzymes involved in glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid cycle on the enterance of human fibroblasts to the S phase. BMC Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12860-015-0062-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metodiev MD, Gerber S, Hubert L, et al. Mutations in the tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme, aconitase 2, cause either isolated or syndromic optic neuropathy with encephalopathy and cerebellar atrophy. J Med Genet. 2014;51:834–838. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiegel R, Pines O, Ta-Shma A, et al. Infantile cerebellar-retinal degeneration associated with a mutation in mitochondrial aconitase, ACO2. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, et al. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsui K-H, Chung L-C, Wang S-W, et al. Hypoxia upregulates the gene expression of mitochondrial aconitase in prostate carcinoma cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2013;51:131–141. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan SY, Zhang Y-Y, Hemann C, et al. MicroRNA-210 controls mitochondrial metabolism during hypoxia by repressing the iron-sulfur cluster assembly proteins ISCU1/2. Cell Metab. 2009;10:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang H, Hua D, Zhang J, et al. MicroRNA-127-3p promotes glioblastoma cell migration and invasion by targeting the tumor-suppressor gene SEPT7. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:2261–2269. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Müssnich P, Raverot G, Jaffrain-Rea M-L, et al. Downregulation of miR-410 targeting the cyclin B1 gene plays a role in pituitary gonadotroph tumors. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:2590–2597. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1064207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang P, Mai C, Wei Y, et al. Decreased expression of the mitochondrial metabolic enzyme aconitase (ACO2) is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:552. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan X, Berg N, Lee JW, et al. MicroRNA miR-223 as regulator of innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104:515–524. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR0218-079R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y, Zhu Y, Xu J, et al. PKN2 in colon cancer cells inhibits M2 phenotype polarization of tumor-associated macrophages via regulating DUSP6-Erk1/2 pathway. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:13. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li K-P, Fang Y-P, Liao J-Q, et al. Upregulation of miR-598 promotes cell proliferation and cell cycle progression in human colorectal carcinoma by suppressing INPP5E expression. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:2991–2997. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleemann M, Schneider H, Unger K, et al. MiR-744-5p inducing cell death by directly targeting HNRNPC and NFIX in ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou X, Ye F, Yin C, et al. The interaction between MiR-141 and lncRNA-H19 in regulating cell proliferation and migration in gastric cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1440–1452. doi: 10.1159/000430309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Y, Zubovic L, Yang F, et al. Rbfox proteins regulate microRNA biogenesis by sequence-specific binding to their precursors and target downstream Dicer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4381–4395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 222 kb) Online Resource 1 Differentially expressed miRNAs in primary and recurrent spindle cell oncocytoma of the pituitary

Supplementary material 2 (PDF 98 kb) Online Resource 2 Pathway analysis of miRNA regulated genes in pituitary oncocytoma vs. normal tissue by Panther Classification System

Supplementary material 3 (PDF 120 kb) Online Resource 3 Gene Ontology (a Biological Process; b Molecular Function) analysis of significant differentially expressed genes influenced by differentially expressed miRNAs in oncocytoma vs. normal tissue

Supplementary material 4 (PDF 98 kb) Online Resource 4 miRNA regulated genes associated with Cellular and Metabolic process GO terms

Supplementary material 5 (PDF 790 kb) Online Resource 5 a Functional analysis of differentially expressed miRNA in oncocytoma. a GO Biological Process representative term summary after removal of redundant terms. b GO Molecular Function representative term summary after removal of redundant terms. c Metabolic gene cluster identified by GO term Functional annotation. d Mitochondrial gene cluster identified by GO term Functional annotation