Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small non-coding RNAs that play increasingly appreciated roles in gene regulation. In animals, miRNAs silence gene expression by binding to partially complementary sequences within target mRNAs. It is well-established that miRNAs recognize canonical target sites by base-pairing in the 5’region. However, the development of biochemical methods has identified many novel, non-canonical target sites, suggesting additional modes of miRNA-target association. Here, we review the current knowledge of miRNA-target recognition and how new evidence supports or challenges existing models. We also review the process by which microRNA isoforms achieve functional diversification via modulation of target recognition.

1. Overview

The revolutionary discovery that noncoding RNAs function as regulators of gene expression has identified an additional layer of control in the already complex network of gene regulation. MicroRNA (miRNA) is arguably the best-known class of noncoding RNA [1]. Despite their small size (~22 nt), miRNAs have a huge impact on development and disease [2]. Depending on the stringency of the inclusion criteria, the number of human miRNAs ranges from ~500 to ~2000 [3], and it is apparent that nearly all known cellular pathways are subject to miRNA regulation.

MicroRNA biogenesis is reviewed in detail elsewhere [4]. In brief, miRNAs are transcribed from the genome as part of long transcripts called primary miRNA (pri-miRNA). The miRNA-embedded hairpin is cropped from the pri-miRNA by the ribonuclease Drosha in the nucleus and then translocated to the cytoplasm via Exportin-5. This hairpin, termed precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA), is further cleaved by Dicer, resulting in a small RNA duplex. One strand (the miRNA/guide strand) of this duplex is loaded onto Argonaute (Ago) proteins, forming the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and enabling its inhibitory function. Depending on the degree of sequence complementarity between the miRNA and its target, RISC can induce either site-specific cleavage and/or non-cleavage repression of gene expression. While the former is prevalent in plants, the latter is the dominant form of repression in animals and consists of translational inhibition and/or enhanced mRNA degradation [5].

Although the detailed mechanism of miRNA-mediated repression remain elusive, it is clear that the association between RISC and target mRNA is both necessary and often sufficient to trigger the inhibition of target expression. In this regard, RISC functions in a similar way to RNA-binding proteins, with miRNA acting as the RNA-binding domain to provide specificity. Therefore, understanding how RISC-associated miRNAs specifically recognize target sequences is an essential step towards deciphering the function of miRNAs. However, this seemingly simple task is extremely complicated in animals for two reasons: 1) partial pairing is sufficient to induce gene silencing and 2) different regions of a miRNA have variable impacts on the miRNA:target hybridization because of the influence of proteins in the RISC [6]. For example, 7 nucleotides from positions 2 through 8 of the 5’ end of a miRNA (the seed), are crucial for determining target specificity [7].

In this review, we first summarize the current understanding of how the 5’ (seed) region of miRNAs contributes to the canonical model of RISC:target recognition, as well as recent insights into unexpected roles of the 3’ region in noncanonical RISC:target interactions. We then discuss how the specific pairing between RISC and targets can be modulated through the formation of miRNA isoforms (isomiRs), and potential implications for regulation of miRNA function.

2. Role of miRNA 5’ region (seed) in target recognition

Although the first few miRNA target site sequences were revealed by classical genetic approaches, initial insights into miRNA target recognition mainly came from bioinformatic analyses [7]. Known miRNA:target pairing patterns were used to develop algorithms to predict functional target site sequences. The importance of perfect Watson-Crick pairing in the seed region of miRNA target sequences was quickly identified; it alone is sufficient to predict many functional targets. Further studies revealed that the pairing of miRNA position 8 was dispensable in many cases, indicating that the seed region can be as short as a 6mer segment between positions 2 and 7. Interestingly, an adenosine nucleotide (A) was enriched among functional targets in a position across from the first nucleotide of the miRNA, regardless of its identity. Based on these insights, canonical target sites were defined as sequences identified in the 3’UTR with minimal Watson-Crick pairing to miRNA positions 2-7 and having either an additional base-pair at miRNA position 8 (7mer-m8 sites), an A cross from miRNA position 1 (7mer-A1 sites) or both of these features (8mer sites) [7,8]. In other words, canonical target sites are sequences which are able to perfectly pair to the 5’ region of a miRNA (Figure 1A).

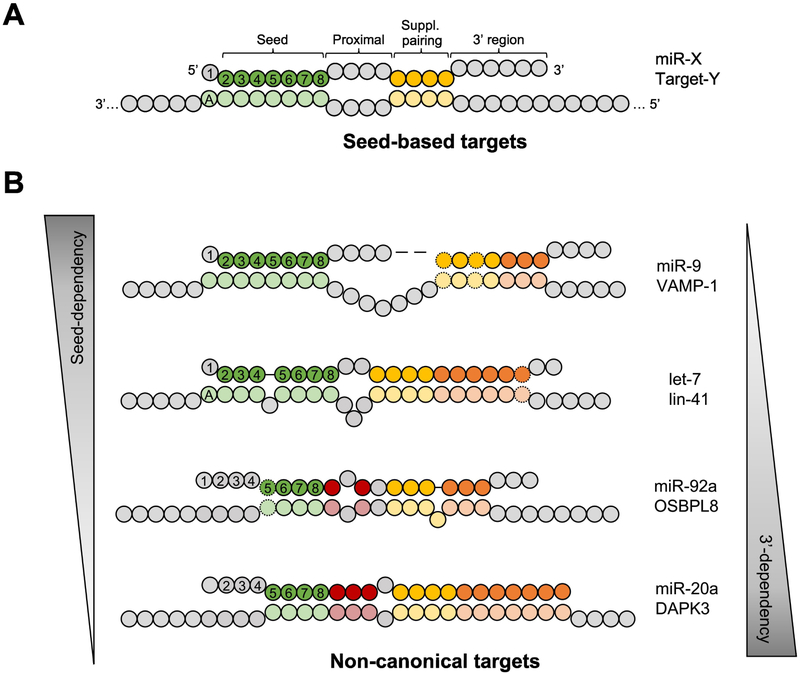

Figure 1. Role of miRNA 5’ and 3’ regions in target recognition.

(A) Illustration of the canonical model for miRNA:target recognition: The seed (nucleotides 2-8) plays a central role, aided by a variable number of nucleotides in the middle referred as the supplementary pairing (nucleotides 13-16), whereas the pairings at proximal and 3’ regions are dispensable. An adenosine nucleotide cross from miRNA position 1 is beneficial. (B) Examples of canonical and non-canonical targets. The seed-dependency is reverse correlated with an extended 3’ pairing. Nomenclature used in these illustrations: nucleotides not involved in any base pairing (grey), paired nucleotides at seed region (green), at seed-proximal region (red), at supplementary region (yellow) and at 3’ region (orange). G:U wobbles are indicated by dashed circles.

The apparent importance of seed pairing determined by computational studies was perfectly explained by later structural insights. miRNA forms a complex with Ago in a unique structural organization where only the seed region is exposed and available to pair with target mRNAs [9]. The first nucleotide of miRNA is inserted inside the Ago protein and does not participate in the hybridization process. Instead, the corresponding nucleotide in the target is recognized by a binding pocket in Ago, which explains the preference of an A at this position [10]. Single-molecule studies further demonstrated how RISC modulates hybridization between miRNA and target sequences by ensuring that the process is initiated by pairing of the seed sequence [11,12]. Finally, the functional importance of the seed region is also supported by evolutionary evidence. Comparing human miRNAs with their orthologs in other species revealed that the seed sequences are highly conserved, with a nucleotide substitution rate substantially lower than that in other parts of miRNAs [3].

3. Role of miRNA 3’ region in target recognition

In contrast to the miRNA 5’ (seed) region, the role of the 3’ region in miRNA-target recognition is less defined. Early evidence arose from reported cases of miRNA repression without perfect pairing in the seed region [13]. In those cases, increased pairing in the 3’ region was observed (Figure 1B). The next line of evidence followed the development of Ago-crosslinking immunoprecipitation and sequencing (CLIP-seq) techniques that allowed for high-throughput identification of endogenous and viral miRNA targets [14,15]. Later, this technique was modified to capture chimeric reads containing both miRNA and target RNA sequences (Table S1). These studies provided compelling evidence of direct physical interactions between miRNAs and many types of non-canonical target sites. Pairings in the seed region present in ~60-80% of the interaction sites whereas extensive pairings in the 3’ region were found in ~30-40% of these interactions [16,17]. Surprisingly, the CLIP analyses also identified interactions that were independent of the seed base-pairing, in which only extensive base-pairing in the 3’ region was observed. For example, miR-92a was found to recognize a target sequence in OSBPL8 mRNA with half of its seed region unpaired (Figure 1B). Experimental validations of CLIP-based miRNA:target interactions using reporter assays showed modest but significant repression [17]. Nonetheless, the overall functional importance of these non-canonical target sites is still in question [18].

The biological importance of pairing in the 3’ region of miRNAs in defining target specificity was further illustrated by the finding that miRNA families target non-overlapping sets of target sites [16]. Because members of a miRNA family share the same seed sequence, the fact that their target repositories are different indicates that regions other than seed also play a critical role in target recognition. Indeed, it was shown that pairings in the 3’ region contribute to target site specificity of let-7 family members in C. elegans [16]. Therefore, pairing in the miRNA 3’ region not only supports the existence of non-canonical target sequences and expands the regulatory scope of miRNAs, but also gives miRNA families a way to break from their seed redundancy and achieve functional specialization of each member [16,19].

Recently, in vitro assays based on RNA bind-n-seq of AGO2 programmed with different miRNAs have shown that some miRNAs (miR-1,let-7a) exhibit ~70% binding to canonical seed targets while others (miR-124, miR-155), bind to canonical seed targets at a level of only ~40-50% and present unique targets based on the 3’ region pairing [20]. These results indicate that the role of 3’ region pairing could be dynamic and context-dependent, challenging the idea of a “one-fits-all” model in describing all miRNA target recognition patterns.

It was well-established that miRNA target sites located in the 3’UTR are most effective, largely owing to the absence of interference from ongoing translation [21]. Nonetheless, CLIP data revealed frequent interactions (~20-30%) between RISC and targets occurring in the coding sequence (CDS) [16,22]. This controversy was partially explained by a recent finding that in mammalian stem cells pre-mRNAs are targeted by RISC in the nucleus where translation is absent [23]. Interestingly, a class of non-canonical target sites function only in the CDS, repressing translation but not inducing mRNA destabilization [24]. These target sites are characterized by extensive pairing to the 3’ region rather than the seed of the cognate miRNA (e.g. miR-20a:DAPK3) (Figure 1B). The fact that GW182 (an essential factor in the canonical miRNA repression pathway) is dispensable for inhibition of this type of target sites indicates a distinct underlying mechanism.

4. IsomiRs

Until recently, it was thought that each hairpin-shaped pre-miRNA encoded up to two potential mature miRNAs: one from the 5-prime arm (5p strand) and the other from the 3-prime arm (3p strand). However, with the advent of next generation sequencing, we now know that a single miRNA locus can generate multiple distinct miRNA isoforms (isomiRs) that differ in length, sequence composition or both. Depending on the region of heterogeneity, isomiRs can be further categorized into 5’ isomiRs and 3’ isomiRs. The expression of 3’ isomiRs is particularly robust and can be detected by northern blot. In addition, studies have shown that isomiRs can be loaded onto the RISC complex by binding to Ago1 and Ago2 and therefore potentially functional [25].

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that isomiRs possess unique biological roles (Table S2). First, like canonical miRNAs, isomiRs are conserved throughout evolution [26]. Second, biogenesis of isomiRs is tightly regulated. The profile of isomiRs is usually cell-and tissue-specific and can be used as a biomarker to identify many diseases, including cancers [27,28]. Finally, recent reports indicate that naturally existing isoforms have distinct activities in a wide range of biological processes, including regulation of cytokine expression [29], facilitation of virus proliferation [30], promotion of apoptosis [31] and repression of tumor progression [32]. These exciting findings highlight the importance of understanding the biogenesis and function of isomiRs.

4.1. 5’ IsomiRs

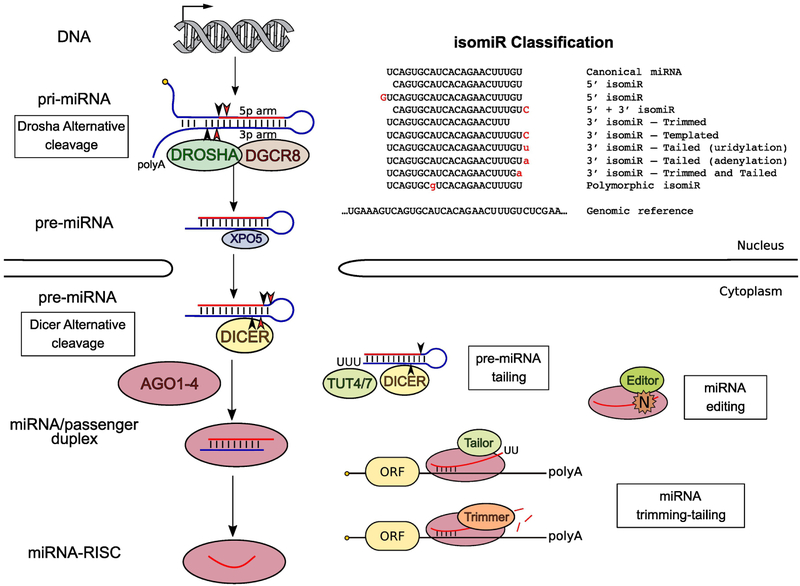

Given that post-maturation sequence modifications at the 5’ end of miRNAs are extremely rare, most 5’ isomiRs arise from imprecise cleavage by either Drosha or Dicer during miRNA biogenesis (Figure 2). Although high throughput methods have revealed that alternative cleavage by Drosha and/or Dicer is a common occurrence [33,34], the underlying mechanisms for this variation are largely unknown. Several studies have shown that deviations from the optimal distances between the expected cleavage site, the basal junction and the apical junction of a pri-miRNA can result in Drosha cleavage at alternative sites [35,36]. Moreover, structural defects in the lower stem that distort the overall helical structure of the pri-miRNA, as well as the absence of a specific interaction between Drosha and a sequence motif in the lower stem, can induce imprecise Drosha cleavage [32,37]. RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA1 have been reported to regulate Drosha cleavage by altering pri-miRNA structure [38]. One might hypothesize that such proteins also impact Drosha alternative cleavage. Similarly, studies of Dicer cleavage site selection have revealed the impacts from the relative position of the loop [39], structural ambiguities, as well as Dicer cofactors such as TRBP [40].

Figure 2. Biogenesis of 5’ and 3’ isomiRs.

5’ isomiRs are generated almost exclusively by imprecise Drosha and/or Dicer processing. Alternative choices of cleavage sites result in isomiRs with a distinct 5’ end from the cognate miRNAs. Imprecise Drosha and/or Dicer processing also contributes to the production of 3’ isomiRs with templated nucleotides (3’ isomiR-Templated). Nonetheless, 3’ isomiRs are mainly produced by post-maturation sequence modifications: trimming and tailing, resulting in 3’ isomiR-Trimmed and 3’ isomiR-Tailed respectively. Note, observed tails on isomiRs from 3p arm can be added at the stage of pre-miRNA and/or mature miRNA. Although less frequent (<1%), some isomiRs contain internal nucleotide(s) different from the genomic sequence (Polymorhic isomiR) due to possible RNA editing events.

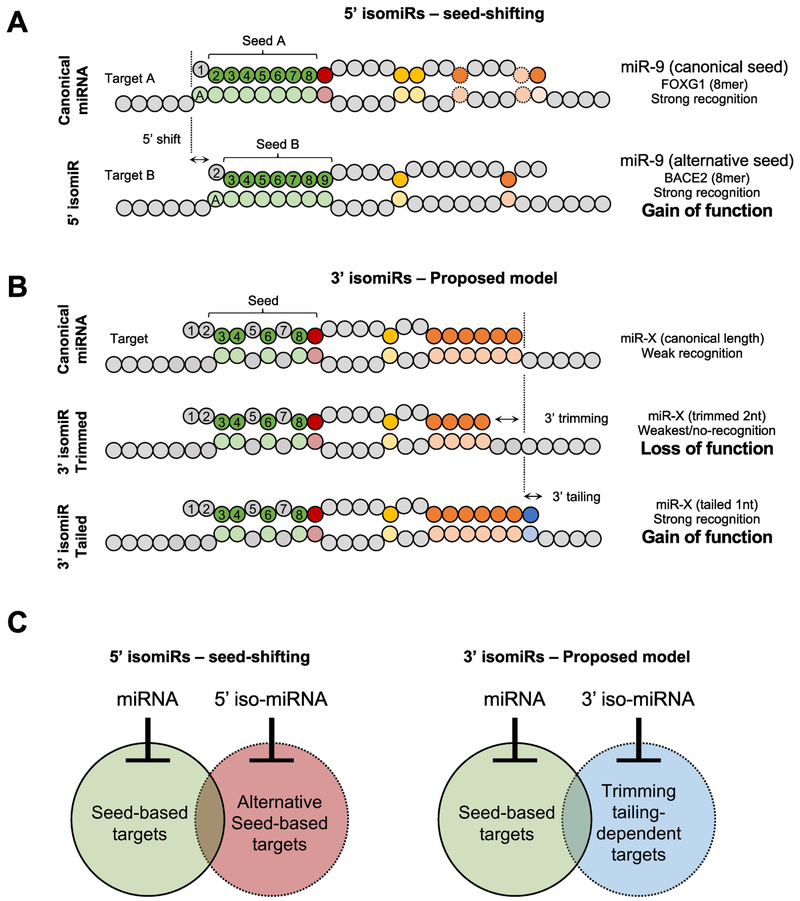

Given that 5’ isomiRs usually have a different start position from which the seed region is defined, it is straightforward to understand that 5’ isomiRs modulate RISC-target interactions by shifting the seed sequences (Figure 3A). This change to seed sequence allows 5’ isomiRs to regulate distinct sets of target genes, thereby conferring unique biological functions to the isomiRs [26,32]. Studies have suggested that in some cases canonical miRNAs and their corresponding 5’ isomiRs could function cooperatively within biological pathways [41]. Moreover, changes in the first nucleotide have also been associated with changes in miRNA half-life, potentially yielding isoforms with differing stabilities [42].

Figure 3. Proposed models for how 5’ and 3’ isomiRs modulate target recognition.

(A) Examples of miR-9 recognizing one of its cognate target (FOXG1) through its canonical seed and recognizing a novel target (BACE2) through its alternative seed of an 5’ isomiR. These examples illustrate how Drosha and Dicer alternative cleavage can generate a gain of function through seed shifting. (B) Proposed model of how 3’ trimming of a miRNA abolishes the recognition of a 3’-pairing-dependent target and how tailing promotes a gain of function in target recognition. (C) Venn diagrams illustrating the impacts of 5’ and 3’ isomiRs on expanding the miRNA repression capabilities.

A major concern regarding the biological function of 5’ isomiRs is that their expression levels are usually much lower than those of the cognate miRNAs. Nonetheless, many 5’ isomiRs have sufficient abundance to cause repression in specific tissues or diseased cells. In low grade glioma (LGG) biopsies, an 5’ isomiR of miR-9 is expressed at a level higher than that of miRNAs with well-established functions such as let-7, miR-30 or miR-21 [32]. Interestingly, although miR-9 is encoded by three paralog genes (pri-miR-9-1, pri-miR-2 and pri-miR-9-3), this 5’ isomiR of miR-9 is generated solely from pri-miR-9-1. Unique structural features of pri-miR-9-1 cause Drosha cleavage at an additional position [32]. Therefore, Drosha-mediated 5’ isomiR production can provide a general mechanism for members of pri-miRNA families to achieve functional specialization. This neofunctionalization is of special interest given that >40% of miRNAs are members of a family, and ~14% are miRNA paralogs with identical mature sequences.

4.2. 3’ IsomiRs

Although alternative choices of cleavage sites by Drosha and Dicer during biogenesis contribute to the production of 3’ isomiRs, the majority are a result of post-maturation modifications that occur almost exclusively at the 3' end of miRNAs [43]. These modifications mainly consist of trimming (exoribonucleases mediated removal of nucleotides), tailing (addition of nucleotides by terminal nucleotidyl transferases) and the combination of both. While isomiRs containing non-templated nucleotides which cannot be mapped back to the genome clearly result from post-maturation modifications, it is otherwise difficult to track the origin of isomiRs [44]. “Templated” isomiRs which differ from cognate miRNAs only in length could be generated either before or after miRNA maturation, making the characterization of these isomiRs challenging (Figure 2).

Although 3' isomiRs are highly prevalent, little is known regarding their biogenesis or function[45]. One of the best-known modifications is 3’ tailing (mainly adenylation and uridylation). A group of Terminal Uridylyl Transferases (TUTs), including TUT4, TUT7, TUT2 and TUT1, are implicated in uridylation or adenylation of the mature miRNAs [45]. It is worth noting that TUT4/7 uridylate pre-miRNAs as well, in turn producing a variety of isomiRs. For 3p miRNAs, it is nearly impossible to separate nucleotides added to pre-miRNA from those added directly to the mature miRNA, adding another layer of complexity to isomiR biogenesis.

The profile of 3’ isomiRs is highly specific among different miRNAs. TUT4/7 are reported to preferentially uridylate miRNAs containing certain sequence motifs in vitro [46]. However, this preference by itself cannot account for all uridylations observed in 3’ isomiRs. One mechanism known to promote 3’ isomiR production is target directed miRNA decay (TDMD), in which highly complementary target RNAs trigger miRNA tailing and trimming, and eventually leads to miRNA degradation [47]. Interestingly, pairing to the 3’ rather than the 5’ region of a miRNA is essential in TDMD: a recent report demonstrated that targets without seed-pairing are more efficient in inducing TDMD [48]. Natural triggers of TDMD could underlie the specificity observed among 3’ isomiRs. For example, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) Cyrano and NREP regulate the abundance of miR-7 [49] and miR-29 [50] respectively via TDMD. In both cases, disrupting such regulation resulted in concurrent changes of 3’ isomiR profiles, miRNA levels and associated phenotypes.

Recent studies suggest that 3’ isomiRs are more than intermediates of miRNA degradation, and function beyond regulating miRNA stability. For example, the profile of 3’ isomiRs (rather than the overall abundance) can be used to distinguish different stages of cancer progression [27,28]. In addition, many 3’ isoforms are reported to have distinct activities compared to the corresponding miRNAs [29–31]. However, different from 5’ isomiRs, 3’ isomiRs share the same seed sequence as their cognate miRNAs and are expected to function similarly. A solution to this apparent paradox may come from revisiting the known principles of miRNA-target interaction: In light of the growing appreciation for the role that the 3’ region of miRNAs plays in target association, it is possible that 3' isomiRs are able to regulate distinct sets of mRNAs from their cognate miRNAs simply due to the sequence heterogeneity at the 3' regions (Figure 3B, C).

5. Future perspective

Our understanding of how genes are regulated by miRNAs in both health and disease has exploded in the past decade. However, it is clear that this new understanding has brought forth many new questions. While a wave of CLIP-seq results revealed many non-canonical target sites and challenged the “seed-centric” model of miRNA-target recognition, a major unresolved question is the extent to which these new interactions possess biological significance. Nonetheless, the importance of pairing regions other than the seed (the 3’ region in particular), is well supported and should not be ignored. In parallel, given that the search for new miRNAs is coming to its end, isomiRs (especially those highly expressed 3’ isomiRs) deserve more attention towards addressing their biological roles. These two apparently different directions are deeply connected. An intriguing hypothesis is that pairing between targets and the 3’ end of miRNAs defines a reciprocal-relationship: it not only triggers 3’ isomiR production via mechanisms similar to TDMD, but also determines the binding ability of these 3’ isomiRs therefore repression of targets (Figure 3B). Further mechanistic studies and structural insights into RISC-target association with a focus on miRNA 3’ region pairing will shed light upon this exciting direction of miRNA research.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mechanistic view of the “seed-centric” model of miRNA-target interaction in animals

New mechanistic insights into miRNA recognition of non-canonical targets

Brief summary of the current understanding of isomiR biogenesis and function

Discussion of how miRNA target recognition can be modulated through the formation of isomiRs

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Gu lab for their helpful discussion and critically reading of the manuscript. Authors apologize for any uncited references that were left out due to space limitations. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- [1].Bartel DP, Metazoan MicroRNAs., Cell. 173 (2018) 20–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lin S, Gregory R.l., MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer., Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (2015) 321–333. doi: 10.1038/nrc3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fromm B, Billipp T, Peck LE, Johansen M, Tarver JE, King BL, et al. , A Uniform System for the Annotation of Vertebrate microRNA Genes and the Evolution of the Human microRNAome., Annu. Rev. Genet 49 (2015) 213–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Treiber T, Treiber N, Meister G, Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20 (2019) 5–20.doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gu S, Kay MA, How do miRNAs mediate translational repression?, Silence. 1 (2010) 11. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wee LM, Flores-Jasso CF, Salomon WE, Zamore PD, Argonaute divides its RNA guide into domains with distinct functions and RNA-binding properties., Cell. 151 (2012) 1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bartel DP, MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions., Cell. 136 (2009) 215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kim D, Sung YM, Park J, Kim S, Kim J, Park J, et al. , General rules for functional microRNA targeting., Nat. Genet 48 (2016) 1517–1526.doi: 10.1038/ng.3694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang Y, Sheng G, Juranek S, Tuschl T, Patel DJ, Structure of the guide-strand-containing argonaute silencing complex., Nature. 456 (2008) 209–213.doi: 10.1038/nature07315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schirle NT, Sheu-Gruttadauria J, MacRae IJ, Structural basis for microRNA targeting., Science. 346 (2014) 608–613. doi: 10.1126/science.1258040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chandradoss SD, Schirle NT, Szczepaniak M, MacRae IJ, Joo C, A dynamic search process underlies microrna targeting., Cell. 162 (2015) 96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Salomon WE, Jolly SM, Moore MJ, Zamore PD, Serebrov V, Single-Molecule Imaging Reveals that Argonaute Reshapes the Binding Properties of Its Nucleic Acid Guides., Cell. 162 (2015) 84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Vella MC, Choi E-Y, Lin S-Y, Reinert K, Slack FJ, The C elegans microRNA let-7 binds to imperfect let-7 complementary sites from the lin-41 3’UTR., Genes Dev. 18 (2004) 132–137. doi: 10.1101/gad.1165404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB, Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps., Nature. 460 (2009) 479–486.doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, et al. , Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP., Cell. 141 (2010) 129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Broughton JP, Lovci MT, Huang JL, Yeo GW, Pasquinelli AE, Pairing beyond the Seed Supports MicroRNA Targeting Specificity., Mol. Cell 64 (2016) 320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Helwak A, Kudla G, Dudnakova T, Tollervey D, Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding., Cell. 153 (2013) 654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J-W, Bartel DP, Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs., Elife. 4 (2015). doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brancati G, Großhans H, An interplay of miRNA abundance and target site architecture determines miRNA activity and specificity., Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (2018) 3259–3269. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McGeary SE, Lin KS, Shi CY, Bisaria N, Bartel DP, The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy, BioRxiv. (2018). doi: 10.1101/414763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gu S, Jin L, Zhang F, Sarnow P, Kay MA, Biological basis for restriction of microRNA targets to the 3’ untranslated region in mammalian mRNAs., Nat. Struct.Mol. Biol 16(2009) 144–150. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Loeb GB, Khan AA, Canner D, Hiatt JB, Shendure J, Darnell RB, et al. , Transcriptome-wide miR-155 binding map reveals widespread noncanonical microRNA targeting., Mol. Cell 48 (2012) 760–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sarshad AA, Juan AH, Muler AIC, Anastasakis DG, Wang X, Genzor P, et al. , Argonaute-miRNA Complexes Silence Target mRNAs in the Nucleus of Mammalian Stem Cells., Mol. Cell 71 (2018) 1040–1050.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhang K, Zhang X, Cai Z, Zhou J, Cao R, Zhao Y, et al. , A novel class of microRNA-recognition elements that function only within open reading frames., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25 (2018) 1019–1027. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ameres SL, Zamore PD, Diversifying microRNA sequence and function., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 14 (2013) 475–488. doi: 10.1038/nrm3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tan GC, Chan E, Molnar A, Sarkar R, Alexieva D, Isa IM, et al. , 5’ isomiR variation is of functional and evolutionary importance., Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014) 9424–9435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Telonis AG, Loher P, Jing Y, Londin E, Rigoutsos I, Beyond the one-locus-one-miRNA paradigm: microRNA isoforms enable deeper insights into breast cancer heterogeneity., Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (2015) 9158–9175.doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McCall MN, Kim M-S, Adil M, Patil AH, Lu Y, Mitchell CJ, et al. , Toward the human cellular microRNAome., Genome Res. 27 (2017) 1769–1781.doi: 10.1101/gr.222067.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jones MR, Quinton LJ, Blahna MT, Neilson JR, Fu S, Ivanov AR, et al. , Zcchc11-dependent uridylation of microRNA directs cytokine expression., Nat. Cell Biol 11 (2009) 1157–1163. doi: 10.1038/ncb1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yamane D, Selitsky SR, Shimakami T, Li Y, Zhou M, Honda M, et al. , Differential hepatitis C virus RNA target site selection and host factor activities of naturally occurring miR-122 3΄ variants., Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (2017) 4743–4755. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yu F, Pillman KA, Neilsen CT, Toubia J, Lawrence DM, Tsykin A, et al. , Naturally existing isoforms of miR-222 have distinct functions., Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (2017) 11371–11385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bofill-De Ros X, Kasprzak WK, Bhandari Y, Fan L, Cavanaugh Q, Jiang M, et al. , Structural Differences between Pri-miRNA Paralogs Promote Alternative Drosha Cleavage and Expand Target Repertoires., Cell Rep. 26 (2019) 447–459.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wu H, Ye C, Ramirez D, Manjunath N, Alternative processing of primary microRNA transcripts by Drosha generates 5’ end variation of mature microRNA., PLoS ONE. 4 (2009) e7566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim B, Jeong K, Kim VN, Genome-wide Mapping of DROSHA Cleavage Sites on Primary MicroRNAs and Noncanonical Substrates., Mol. Cell 66 (2017) 258–269.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ma H, Wu Y, Choi J-G, Wu H, Lower and upper stem-single-stranded RNA junctions together determine the Drosha cleavage site., Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110 (2013) 20687–20692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311639110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Roden C, Gaillard J, Kanoria S, Rennie W, Barish S, Cheng J, et al. , Novel determinants of mammalian primary microRNA processing revealed by systematic evaluation of hairpin-containing transcripts and human genetic variation., Genome Res. 27 (2017) 374–384. doi: 10.1101/gr.208900.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kwon SC, Baek SC, Choi Y-G, Yang J, Lee Y-S, Woo J-S, et al. , Molecular Basis for the Single-Nucleotide Precision of Primary microRNA Processing., Mol. Cell (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Michlewski G, Cáceres JF, Post-transcriptional control of miRNA biogenesis., RNA. 25 (2019) 1–16. doi: 10.1261/rna.068692.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gu S, Jin L, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Zhang F, Valdmanis PN, et al. , The loop position of shRNAs and pre-miRNAs is critical for the accuracy of dicer processing in vivo., Cell. 151 (2012) 900–911. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhu L, Kandasamy SK, Fukunaga R, Dicer partner protein tunes the length of miRNAs using base-mismatch in the pre-miRNA stem., Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (2018) 3726–3741. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cloonan N, Wani S, Xu O, Gu J, Lea K, Heater S, et al. , MicroRNAs and their isomiRs function cooperatively to target common biological pathways., Genome Biol. 12 (2011) R126. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-12-r126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhou L, Lim MYT, Kaur P, Saj A, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Gopal V, et al. , Importance of miRNA stability and alternative primary miRNA isoforms in gene regulation during Drosophila development., Elife. 7 (2018). doi: 10.7554/eLife.38389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gebert LFR, MacRae IJ, Regulation of microRNA function in animals., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20 (2018). doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bofill-De Ros X, Chen K, Chen S, Tesic N, Randjelovic D, Skundric N, et al. , GuagmiR: A Cloud-based Application for IsomiR Big Data Analytics., Bioinformatics. (2018). doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ha M, Kim VN, Regulation of microRNA biogenesis., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15 (2014) 509–524. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Thornton JE, Du P, Jing L, Sjekloca L, Lin S, Grossi E, et al. , Selective microRNA uridylation by Zcchc6 (TUT7) and Zcchc11 (TUT4)., Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (2014) 11777–11791. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fuchs Wightman F, Giono LE, Fededa JP, de la Mata M, Target rnas strike back on micrornas., Front. Genet 9 (2018) 435. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Park JH, Shin S-Y, Shin C, Non-canonical targets destabilize microRNAs in human Argonautes., Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (2017) 1569–1583.doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kleaveland B, Shi CY, Stefano J, Bartel DP, A network of noncoding regulatory rnas acts in the mammalian brain., Cell. 174 (2018) 350–362.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bitetti A, Mallory AC, Golini E, Carrieri C, Carreño Gutiérrez H, Perlas E, et al. , MicroRNA degradation by a conserved target RNA regulates animal behavior., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25 (2018) 244–251. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.