Abstract

Immense progress in microscale engineering technologies have significantly expanded the capabilities of in vitro cell culture systems for reconstituting physiological microenvironments that are mediated by biomolecular gradients, fluid transport, and mechanical forces. Here, we examine the innovative approaches based on microfabricated vessels for studying lymphatic biology. To help understand the necessary design requirements for microfluidic models, we first summarize lymphatic vessel structure and function. Next, we provide an overview of the molecular and biomechanical mediators of lymphatic vessel function. Then we discuss the past achievements and new opportunities for microfluidic culture models to a broad range of applications pertaining to lymphatic vessel physiology. We emphasize the unique attributes of microfluidic systems that enable the recapitulation of multiple physicochemical cues in vitro for studying lymphatic pathophysiology. Current challenges and future outlooks of microscale technology for studying lymphatics are also discussed. Collectively, we make the assertion that further progress in the development of microscale models will continue to enrich our mechanistic understanding of lymphatic biology and physiology to help realize the promise of the lymphatic vasculature as a therapeutic target for a broad spectrum of diseases.

Keywords: microfabrication, lymphangiogenesis, lymphatic vessel, interstitial flow, extracellular matrix, vascular engineering, permeability, microfluidic

1. Introduction

A better understanding of how lymphatic vessels develop, grow, and function may be accommodated through the use of controllable experimental systems that mimic living tissue. Along these lines, it is well-appreciated by vascular biologists and physiologists that research in blood vessel angiogenesis and vascular function has benefitted immensely from the development of an impressive breadth of dedicated ex vivo, in vivo, and in vitro bioassays and techniques [1]. However, one can argue that comparable advances have not yet been made for studying lymphatic vessel biology, physiology, and lymphangiogenesis. One major constraint that had impeded progress in lymphatic culture models specifically was that the molecular markers for distinguishing lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) from blood endothelial cells (BECs), such as lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), prospero-related homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PROX-1), and podoplanin, were only recently discovered within the past 20 years [2-5]. Consequently, there is an opportunity to help improve both the quality and availability of in vitro experimental model systems for the application of dissecting important mediators of lymphatic vessel growth and function.

One of the most recent advances in in vitro culture models has been through the design and implementation of microscale culture technologies (e.g. microfluidics) as biomimetic platforms that reconstitute tissue level function in vitro [6]. Microfluidic devices are most commonly fabricated by rapid prototyping of poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS), an optically transparent and gas permeable elastomer [7]. These devices contain networks of micron-scale fluid-filled channels that are similar in size and architecture to lymphatic vessels in vivo [8]. Moreover, microfluidic techniques enable controlled application of fluid flow and wall shear stress to cultured endothelial cells in a platform that can be readily scaled up for high-throughput screening studies [9]. These unique attributes of microfluidic models make them especially versatile for various in vitro, flow-based cell culture experiments [10,11]. Other enabling properties of microfluidics include controllable biomolecular gradients across 3-D scaffolds [12] and spatially-defined cell patterning [13]. These capabilities can be integrated into a single in vitro system that faithfully reconstitutes the mechanical, chemical, cellular, and matrix environments of in vivo physiology.

Here we describe the unique opportunities afforded by microscale culture models for advancing our understanding of lymphatic vessel biology. These microscale models, which are functionally analogous to living tissue, have already been widely adopted for studying blood vessel function and angiogenesis [9,14-19]. However, we argue that comparable progress has not yet been made in the applications of these microscale models for studying the lymphatic microcirculation, although advances to this field are occurring rapidly. To put forth a balanced perspective, we first give a brief introduction on the physiology of lymphatic vessels. Next, we give an overview of the mediators of lymphatic vessel formation and maintenance, with an emphasis on the biomechanical determinants. Subsequently, we provide a critical assessment of the current state of microscale culture models for studying the lymphatic vasculature. The scope of this review is the application of microfluidics for studying: 1) lymphatic vessel barrier function, 2) lymphangiogenesis and 3) interstitial mass transport mediated by lymphatics. Technical challenges and future directions for microfluidic approaches are also discussed. Our intention for this review is to serve not only biologists and physiologists interested in latest technological developments, but also help enable engineers and microtechnologists towards bridging their research with studying lymphatics as it pertains to human health and disease.

2. Lymphatic vessel physiology, function, and lymphangiogenesis

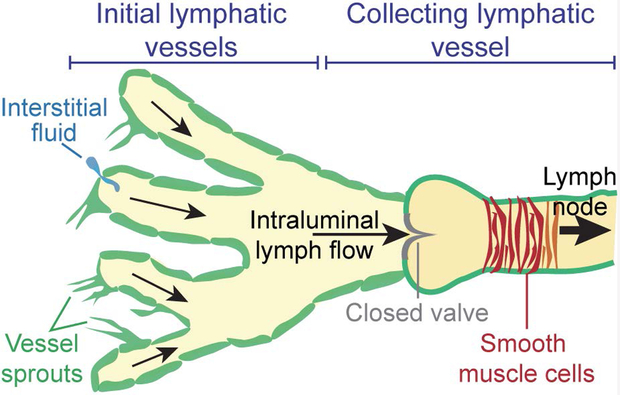

The lymphatic vasculature is comprised of two main elements: 1) the initial lymphatic vessels and 2) the collecting lymphatic vessels (Fig. 1). These two vessel types have distinct and complementary roles towards accomplishing the primary function of lymphatic vasculature, which is to prevent the accumulation of fluid pressure and subsequent edema in tissue [20]. The initial lymphatic vessels (also known as lymphatic capillaries) are small blind-ended vessels of 30 – 80 μm diameter. These vessels are composed of a single layer of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), a discontinuous basement membrane, and are not associated with pericytes [21]. The initial lymphatics are also characterized by unique, button-like, and overlapping cell-cell junctions, which function as primary one-way valves that facilitate absorption of interstitial fluid [22,23]. Fluid entry into the lymphatics is driven largely by pressure gradients and tissue distention that cause the primary valves of the initial lymphatics to be stretched open such that fluid flows along its pressure gradient and into lymphatics [21,22,24]. The interstitial fluid absorbed by the initial lymphatic plexus is converted to lymph and moved towards the collecting lymphatic vessels. Unlike the initial lymphatics, the collecting lymphatic vessels have an intact basement membrane, zipper-like interendothelial junctions, and perivascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [25]. Importantly, the intraluminal valves of the collecting lymphatic vessels prevent back flow, and the contractions by the SMCs propagate lymph fluid towards the lymph nodes where it is eventually returned to blood circulation [26,27].

Figure 1.

Lymphatic vessel anatomy. The initial lymphatic vessels absorb interstitial fluid while the collecting lymphatic vessels lined with smooth muscle cells (SMCs) pump fluid towards the lymph node. Expansion of the lymphatic network occurs by lymphangiogenesis or vessel sprouting.

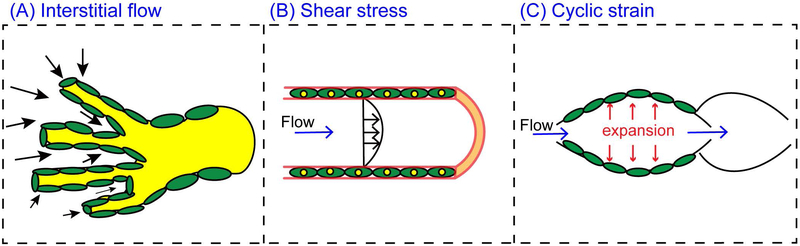

Next, we will discuss the known molecular and biomechanical (Fig. 2) mediators of the lymphatic vasculature that have been studied with various ex vivo, in vivo, and in vitro models.

Figure 2.

Lymphatic mechanobiology. (A) Interstitial flow is driven by the pressure gradient oriented from the interstitium and towards lymphatic vessels. In addition to interstitial flow, lymphatic vessels in vivo are subjected to (B) intravascular shear stress, and (C) circumferential cyclic strain.

2.1. Molecular mediators of lymphatic vessel biology

The expansion of the lymphatic capillary plexus occurs by lymphangiogenesis, which analogous to the angiogenic growth of blood vessel capillaries, entails the extension of endothelial sprouts from pre-existing vessels [28], perfusable lumen formation [29], and associated remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [30,31]. The predominant signaling molecule that governs LEC biology and lymphangiogenesis is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), particularly the VEGF-C and VEGF-D variants [32-35]. Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) VEGFR-3 expressed by LECs with VEGF-C/D drives lymphangiogenesis and the maintenance of new lymphatic vessels [20,36]. Loss of VEGFR-3 function results in the regression of lymphatic vessels [34] with mutated VEGFR-3 being an important predictor for diseases associated with lymphatic dysfunction [36-38]. Moreover, while both VEGF-C and VEGF-D signal through VEGFR-3, distinct receptor-binding specificities and biological activities are emerging between these two VEGF variants [39,40]. Presumably, these findings will have important implications for therapeutic targeting of VEGF-C and/or VEGF-D for controlling lymphangiogenesis.

While the VEGF-A/VEGFR-2 signaling axis is most commonly associated with blood vessel angiogenesis [41], it also plays a role in lymphangiogenesis [36,42]. For instance, inhibiting VEGFR-2 in adult mice resulted in decreased LEC sprouting, although overall lymphatic function remained intact [43]. Other signaling molecules that play an important role in mediating lymphangiogenesis include angiopoietins, which bind angiopoietin receptors (TIE-1 and TIE-2) and are known stimulators of lymphatic growth [36,42,44]. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) helps regulate endothelial permeability and vascular morphogenesis and is required for normal lymphatic patterning [36,45]. In addition, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) has been shown to induce LEC proliferation, migration, and contributes to lymphangiogenesis [46,47]. Other molecules that that have been identified to regulate lymphangiogenesis include collagen and calcium binding EGF domain-containing protein 1 (CCBE1) [48,49] and platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGF-B) [50].

A number of in vitro studies have focused on probing for the specific functions of signaling molecules. For example, Knezevic et al. formed lymphatic and blood vessel networks to interrogate the effects of VEGF-C and adipose-derived stromal cells (ASC), demonstrating the necessity of cell-cell contact between LECs and ASC to form microvascular networks [51]. In addition, Gibot et al. successfully developed a stable 3-D lumen-containing lymphatic capillary networks by co-culturing LECs with fibroblasts on sheets of tissue-engineered skin substitutes [52]. Using this model, they showed that fibroblast-derived hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and VEGF-C are necessary for enhanced proliferation and tube elongation by lymphatic vessels.

2.2. Lymphatic vessel mechanobiology

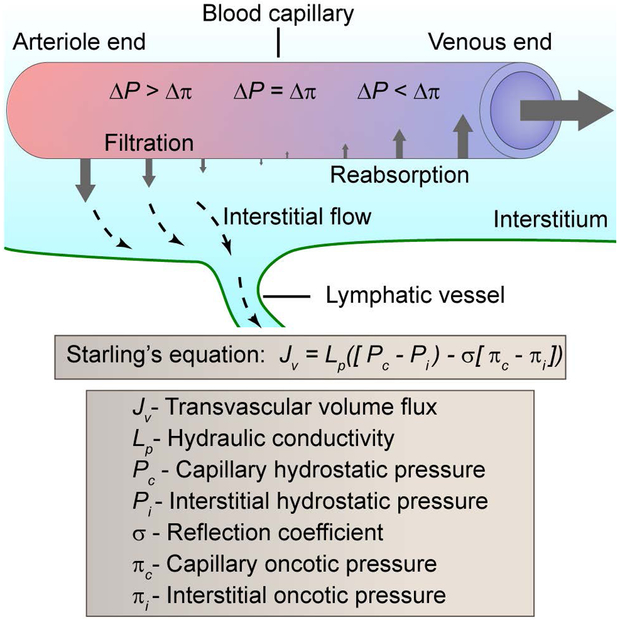

Mechanical stimulation due to interstitial fluid flow or slowly moving convective flow through the tissue interstitium has emerged as a potent mediator of vascular morphogenesis [53,54]. The driving forces for interstitial flow are hydrostatic and osmotic pressure differences between blood vessels, the interstitial space, and lymphatic vessels [55,56] (Fig. 3). These forces (also known as the Starling forces [57]) determine the rate of transendothelial filtration (Fig. 3). The level of interstitial flow is highly dependent on the state of the tissue. For example, under normal conditions, interstitial flow velocities are ~1 μm/s [58] but these levels elevate greatly during inflammatory responses [54]. It is important to note that unlike blood flow, which is driven by a central pump, interstitial flow comprises an open flow loop. Thus, there are numerous challenges to manipulating and accurately measuring interstitial flow in vivo [59]. To this point, much of our current understanding of lymphatic vessel responses to interstitial flow have been obtained with macroscale in vitro 3-D flow chambers, such as radial flow chambers or modified 3-D Boyden chambers (i.e. Transwell filter systems), that were pioneered by the group of Swartz [54,60,61]. These chambers enabled the assessment of the biophysical effects of interstitial fluid flow in 3-D with integration of cellular and molecular analysis in situ.

Figure 3.

Interstitial and transvascular fluid transport. The determinants of interstitial and transvascular transport is governed by Starling’s equation [31]. The hydrostatic pressure gradient (ΔP = Pc − Pi) causes fluid to leave blood vessels (filtration) whereas the oncotic pressure gradient (LΔ = Δc − Δi) causes fluid to enter blood vessels (reabsorption). The level of transvascular volume flux (Jv) scales with the hydraulic conductivity (Lp), which is a function of vessel permeability. Fluid outside of blood vessels moves through the interstitium as interstitial flow that is collected by lymphatic vessels.

In addition to interstitial flow, another important fluid mechanical force in the lymphatic vessel network is intravascular shear stress. LECs are subjected to a wide range of shear stress levels, with typical levels ranging between 4–10 dyn/cm2 [62]. Recently, shear stress has been shown to orchestrate the molecular events that control lymphatic valve formation and stabilization [63-65]. Cyclic strain, or the circumferential expansion of lymphatic vessels, is another mechanical force that is prominent in the lymphatic vasculature [62,66]. The initial lymphatics are subjected to circumferential expansion or contraction due to local tissue stresses, which regulate entry of interstitial fluid through their primary valves [21]. The collecting lymphatics also experience significant cyclic strain levels during the opening and closure of the intraluminal lymphatic valves [62]. Interestingly, it was shown using mathematical modeling that the divergent responses to shear stress and vessel stretch produced two complementary mechanobiological oscillators that are sufficient to control lymphatic pumping and lymph transport [67]. Shear stress induces the release of the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) by LECs while Ca2+-mediated contractions can be triggered by vessel stretch. Impressively, this simple mechanism demonstrated adaptability and autoregulation in lymphatic pumping responses to tissue-level changes in pressure [67]. Nonetheless, further experimental validation may be warranted, for example through the perturbation of the relevant signaling pathways using genetic manipulation or pharmacological inhibitors [68,69].

In accordance with this preceding statement, intravascular shear stress due to lymph flow has also been shown to help drive the genetic program that mediates valve morphogenesis and maturation in the collecting lymphatics [70]. The transcription factors PROX1 and FOXC2 are known to be upregulated and required from the onset of lymphatic valve formation [71,72]. However, a new perspective was put forth by the study by Sabine et al. which elucidated the interplay of PROX1 and FOXC2 with fluid flow in regulating the expression of the gap-junction protein connexin 37 (Cx37) and the activation of calcineurin [63]. Cx37 and calcineurin-dependent signaling were previously shown to be required for lymphatic valve formation [71,73]. Yet, especially intriguing from a mechanotransduction perspective was that time-varying oscillatory shear stress (OSS) and not constant laminar shear stress (LSS) enhanced the expression of FOXC2, Cx37, and calcineurin activation [63]. More recently, OSS was shown to promote lymphatic valve development mediated by canonical Wnt/β-catenin and GATA2 signaling in LECs [65,74,75]. In addition, the role of FOXC2 was further elucidated to promote overlapping intercellular junctions and induce growth arrest in LECs in response to OSS to help promote valve self-organization and stabilization [64]. Collectively, these emerging results suggest that OSS and transient retrograde flow encode specific responses to LECs at the future location of valve leaflets that lead to valve initiation, formation, and maintenance. Despite these significant advancements, a challenge towards a more complete understanding of the mechanisms of force-sensing in LECs is that OSS often regulates molecules that also have flow-independent roles [70]. However, recently the mechanically activated cation channel PIEZO1 [76] was shown to be required for lymphatic valve formation [77], thereby identifying a putative mechanosensor that may be targeted to help enhance lymphatic valve regeneration.

Unlike most ex vivo preparations, many in vitro systems can readily apply controlled levels of dynamic fluid flow. For example, 2-D in vitro flow chambers were used to show that cultured LECs in response to OSS reproduced features of lymphatic valve forming cells such as upregulation of lymphatic valve makers [63-65,75]. In addition, 2-D in vitro microchannel systems are widely used to study LEC monolayer responses to shear stress. Jafarnejad et al. showed that shear-mediated calcium signaling is dependent of the magnitude of applied shear stress, suggesting the importance of dynamic calcium flux in lymphatic mechanotransduction [78]. In a similar experimental setup, Kassis et al. further demonstrated different responses of shear-mediated intracellular calcium signaling in LECs upon simulation with lipoproteins, implicating the negative effect of lipids on lymphatic functions [79]. Other flow chamber models have been developed to study LEC response to shear stress. For example, Breslin et al. used an Electrical Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensor (ECIS) where it was found that LECs dynamically alter their morphology and barrier function in response to changes in shear stress in a Rac1-mediated manner [80]. More recently, Ostrowski et al. developed an impinging flow device capable of exposing LECs to gradient levels of shear stress that varied from 0 to a maximum range of 9–210 dyn/cm2 [81]. In this study, LECs migrated against the flow direction and concentrated at regions of maximum shear stress when at high confluence. However, these same cells at lower density exhibited the opposite behavior by moving with the direction of flow. Using a similar in vitro system, Surya et al. demonstrated that S1P signaling is involved with the collective migration of LECs [82].

Although there is a wealth of evidence that fluid forces affect LEC phenotype, to our knowledge, no study has simultaneously examined the interplay of interstitial flow, luminal shear, and cyclic strain in mediating lymphangiogenesis from an intact vessel with facile experimental manipulation. Microfluidic systems have previously been applied for systematically dissecting the contributions of multiple instructive biophysical and biochemical (or physicochemical) cues on blood vessel angiogenesis (e.g. combined shear stress, interstitial flow, and biomolecular gradients) [16,83,84]. Therefore, we anticipate that future applications of microfluidic models will make comparable advances for studies pertaining to lymphatic vessel mechanobiology. In the next section, we elaborate on the enabling attributes of microfluidic technology.

3. Microfluidic approaches for studying lymphatic vasculature

Many of the key regulators of lymphangiogenesis have been identified in in vivo model systems [85-87]. However, one challenge for studies conducted in vivo is the involvement of confounding inflammatory reactions that are difficult to discriminate from the direct physicochemical effects on LECs [88]. In contrast, microfluidic models are comprised of the necessary 3-D matrix and cell components that are assembled using a microscale “bottom-up” approach to enable exquisite control over the chemical and physical environment such as tuning of ECM properties, spatial patterning of cellular constituents, and specification of biomolecular gradients [6,8]. Therefore, 3-D microfluidic devices permit visualization of lymphatic sprouting, quantification of vessel permeability, and ECM remodeling since they are readily compatible with labeling and imaging techniques such as immunofluorescence, confocal reflectance microscopy, and second harmonic generation imaging. Below we highlight the application of microfluidic technologies in studying three important physiological functions of lymphatics: 1) lymphatic vessel permeability (or barrier function), 2) lymphangiogenesis, and 3) mass transport mediated by lymphatics.

3.1. Quantifying lymphatic vessel barrier function

Regulation of lymphatic barrier function is crucial for optimal lymph formation and transport [80]. Disruptions to lymphatic barrier function is linked to various diseases [89]. For example, malabsorption of dietary fats or lipids by lacteals, or the lymphatic capillaries of the small intestine, can lead to severe clinical pathologies such as intestinal lymphangiectasia [90,91]. In addition, impaired lymphatic barrier function is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes, obesity-associated metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular diseases [20,92,93]. Harvey et al. reported that inactivation of a single allele of Prox1 gene in mice caused adult-onset obesity due to ruptured lymphatic vessels [94]. Moreover, chronic lymphedema, characterized by local accumulation of interstitial fluids due to impaired lymphatic drainage, commonly leads to an abnormal buildup of adipose tissue [95,96]. Lymphatic dysfunction is also involved with the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease, which is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract [97].

Ex vivo approaches using isolated lymphatic vessel segments have been widely used to report values for lymphatic vessel permeability [69,98,99]. However, these measurements have predominantly been in collecting lymphatics. Quantitative permeability values of lymphatic capillaries are not widely reported due to technical difficulties in cannulating this vessel type [100]. Yet, lymphatic capillaries are especially permeable due to their overlapping and discontinuous interendothelial junction structure [21], which also renders these vessels more susceptible to paracellular intravasation by immune and cancer cells [101]. Therefore, microfluidic technology may offer engineering-based approaches for reconstituting lymphatic capillary analogues in vitro and for quantifying vessel permeability in response to external stimuli.

One microfluidic approach for quantifying vessel permeability is to use microchannels that are templated within a semi-porous ECM scaffold such as collagen. This technique was pioneered by the group of Tien where a microchannel is formed by casting collagen housed within a PDMS chamber around a cylindrical needle or rod that is ~100 μm in diameter [15]. Once the scaffold has polymerized, the needle or rod is removed leaving an open cylindrical microchannel that is embedded within the 3-D scaffold. Subsequently, the circular microchannels are seeded with endothelial cells that are allowed to attach and spread on the internal surface to yield a fully endothelialized circular lumen. Using this approach, Tien and colleagues measured changes in the permeability responses of blood endothelium to inflammatory cytokines [15] and cyclic AMP [102]. Moreover, this approach was adapted for the lymphatic endothelium, where unlike the microengineered blood microvessels, many focal leaks were observed in the microengineered lymphatic microvessels [103]. However, treatment of the lymphatic microvessels with cyclic AMP significantly improved barrier function and increased VE-cadherin expression levels at cell-cell borders [103]. Another approach for measuring vessel permeability was demonstrated by Sato et al. where a two-layer microfluidic model with upper and lower channels was separated by a semi-porous membrane [104]. Using this device setup, the vascular permeabilities between co-cultured LECs and BECs was assessed. Moreover, this study assayed for the effects of vascular damage incurred by habu snake venom on blood endothelium permeability and lymphatic return rate.

In addition to probing the effects of biomolecular signaling molecules, microfluidic models have been used to study the role of fluid mechanical forces, such as shear stress, on vessel permeability. However, the findings by the research field have so far focused on blood and not lymphatic vessels. For example, in another study by Tien’s group using the previously described cylindrical microchannel model, it was shown that barrier function of blood endothelium was a function of shear stress levels [105]. Buchanan et al. also used a cylindrical microchannel model that contained a BEC-lined microvessel that was surrounded by MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [106]. This study demonstrated that increasing levels of shear stress ranging from 1–10 dyn/cm2 lowered vessel permeability by counteracting the effects of the pro-angiogenic molecules secreted by the MDA-MB-231 cells. More recently, it was demonstrated in a microfluidic blood vessel bifurcation vessel model that the local flow dynamics due to the branching vessel architecture controlled endothelial permeability in a NO-dependent manner [14]. Nonetheless, these aforementioned microfluidic systems for studying blood microvessels can be readily adapted for the lymphatic vasculature for assessing shear-mediated changes in lymphatic vessel permeability, which may be further warranted due to prior work implicating shear-induced NO release and bioavailability in regulating lymphatic permeability in type 2 diabetic mice [107].

3.2. Investigating the mediators of lymphangiogenesis

Lymphangiogenesis plays an important role in a wide range physiological conditions and pathological complications [108,109]. For example, inflammation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) has been shown to trigger lymphangiogenesis by upregulating VEGF-C by LECs [110]. Increased lymphangiogenesis has been reported in the joints of mice with inflammatory arthritis [111]. The resulting increase in lymphatic vessel density augments macrophage activation and mobilization during immune responses [112]. Patient autopsies revealed that increased lymphangiogenesis often occurs near arterial walls that are subject to inflammation or plaque buildup [113]. These newly formed lymphatic vessels serve to remove the deposited cholesterols and assist in alleviating atherosclerosis [20]. Moreover, recent studies using conditional mouse models have provided novel insights on the therapeutic implications of enhancing lymphatic vessel growth. For instance, it was shown that stimulating cardiac lymphangiogenesis in vivo with VEGF-C improves immune cell clearance and the resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction (MI) [114]. Similarly, kidney specific expression of VEGF-D increased renal lymphangiogenesis, reduced renal immune cell accumulation, and prevented hypertension [115]. Furthermore, lymphangiogenesis is required to mitigate impaired wound healing which is a common complication in diabetic patients [116].

While lymphangiogenesis is essential to coordinate immune responses, increased lymphatic vessel growth may have unfavorable outcomes in certain settings [117]. One such example is increased lymphangiogenesis enhanced immune responses in kidney and corneal transplant rejection [118,119]. In addition, aberrant levels of lymphangiogenesis is common in numerous primary human cancers including melanoma [120], breast [121], lung [122], and head and neck [123,124]. Furthermore, increased lymphangiogenesis, particularly at the margins of primary tumors, is strongly implicated in metastasis through the lymphatic vasculature [125,126]. Elevated expression of VEGF-C and VEGF-D by cancer cells is also correlated with poor prognosis, invasion, and metastasis [32,127]. Additionally, the CCL21/CCR7 chemokine axis induces secretion of VEGF-C by breast cancer cells to promote lymphangiogenesis [128].

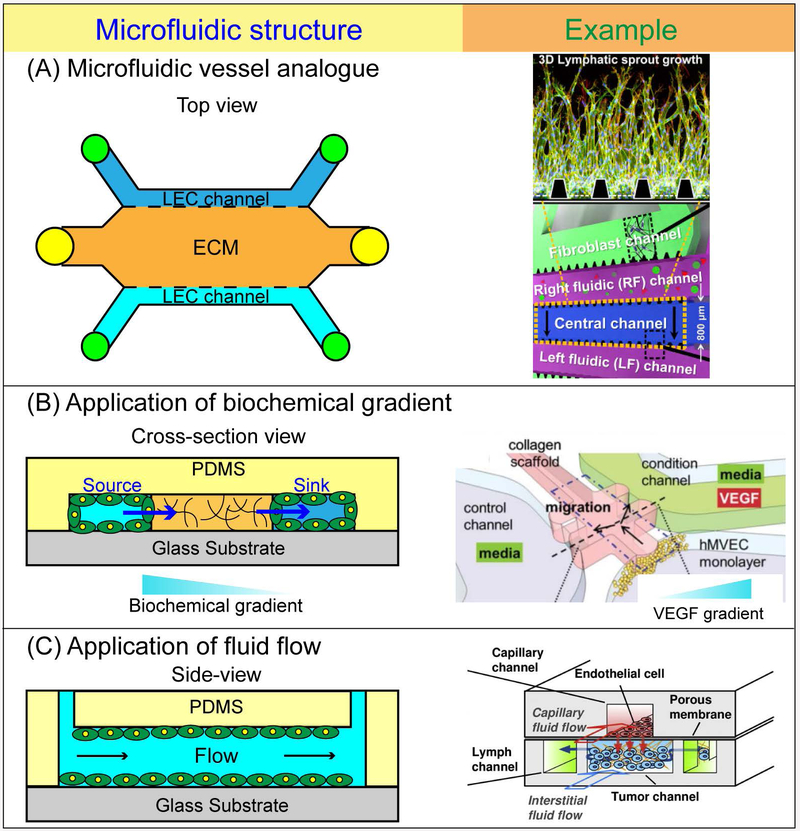

Systematic exploration of the mediators of lymphangiogenesis under controlled culture conditions may help improve our fundamental understanding of the etiology of lymphatic pathologies. To this end, a significant advance in 3-D culture models of lymphangiogenesis was previously reported by Bruyere et al. who developed an ex vivo lymphatic ring assay [88], which was an adaptation of the widely used aortic ring assay for angiogenesis [1]. In addition, the rat mesentery has effectively been used as an ex vivo model for comparing the effects of VEGF-C on lymphatic and blood vessel sprouting density [129], and understanding the role of VEGF-A in increasing the frequency of blood-lymphatic misconnections [130]. However, both the aforementioned lymphatic ring and rat mesentery are static culture models [131]. Consequently, they are not conducive for dynamic control of interstitial pressure gradients, transmural pressure, and intravascular shear stress. Therefore, a better understanding of the complex interplay between molecular, cellular, and fluid mechanical factors during lymphangiogenesis may be achieved with 3-D microfluidic models. One recent advancement was demonstrated by Kim et al. who developed a 5-parallel channel microfluidic model to investigate lymphangiogenesis in vitro when co-cultured with fibroblasts (Fig. 4). This report demonstrated that a cocktail of pro-angiogenic factors that included VEGF-A, VEGF-C, bFGF, and S1P was the most potent of the combinations tested for triggering lymphatic vessel sprouting [132]. Moreover, this study demonstrated that interstitial flow (0.5 – 4 μm/s) selectively augments lymphangiogenesis when applied opposite or against the direction of sprouting. Together, these results suggest that biomolecular factors and interstitial flow cooperate in guiding lymphangiogenesis. It is noteworthy that the outcome described by Kim et al. is similar to what was previously reported with the application of microfluidic systems on the directional bias of blood vessel angiogenesis when interstitial flow is oriented against the direction of sprouting [17,84,133].

Figure 4.

Microfluidic approaches for studying lymphatic vasculature. (A) Schematic of a representative configuration of a microfluidic vessel and corresponding example [128]. The multiple parallel microfluidic channels fully-lined with LECs and laterally adjacent to a localized ECM for which the LECs can undergo sprouting. (B) Application of biochemical gradients and corresponding example [142]. Microfluidic models can be configured such that a sustained biochemical gradient of a signaling molecule (e.g. VEGF) forms from the source channel, across the ECM, and into the sink channel. (C) Controlled application of fluid flow and corresponding example [135]. Microfluidic systems are highly versatile in the nature of fluid flow that can be applied. Therefore, these systems are conducive for studying LEC mechanobiology in response to interstitial flow and laminar shear stress. Microfluidic systems can also be applied to study the effects of drug transport combined with interstitial flow that is representative of the tumor microenvironment.

In a separate study, Chung et al. created a biomimetic tumor microenvironment (TME) model that allowed for simultaneous observation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis while co-cultured with cancer cells and fibroblasts [134]. Choi et al. used a cylindrical 3-D vessel assay that demonstrated that laminar shear stress (2 dyn/cm2) selectively suppresses Notch activation in LECs but not BECs, resulting in an increase in lymphatic sprouting [135]. In a previous microfluidic study, it was shown that laminar shear stress (3 dyn/cm2) suppressed VEGF-A induced blood vessel sprouting [84]. Therefore, the results reported by Choi et al. provide a molecular basis for the divergent shear stress-mediated responses by LECs and BECs as it pertains to lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis [135]. Finally, a recent study by Kamm and colleagues developed a dual cylindrical vessel model to form fully-perfusable and parallel lymphatic and blood microvessels [136]. While the engineered blood microvessel displayed zipper-like junctions, the lymphatic microvessel exhibited both zipper-like and button-like junctions when treated with the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasome. In addition, it was shown that application of a VEGFR-3 inhibitor (SAR131675) suppressed sprouting from the lymphatic vessel when grown as a monoculture. While this aforementioned result was expected, a somewhat surprising outcome was that the effects of inhibiting VEGFR-3 were abrogated when the lymphatic vessel was co-cultured with a blood vessel. The authors attributed this result to MMP secretion by BECs during angiogenesis, which concurrently facilitated lymphangiogenesis. Therefore, this study provided interesting insights on the molecular cross-talk mechanisms that arise during simultaneous angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis.

3.3. Studying the effects of lymphatics on interstitial mass transport

Since the lymphatic circulation mediates tissue fluid balance [20], it is a critical determinant of convective fluid and solute transport in interstitial tissue that is necessary for the distribution of nutrients, waste products, and signaling molecules involved in regulating cell function [55]. In addition, the lymphatic system also has an important role in regulating lipid transport [137]. The attributes of microfluidic models make them readily capable for precise quantitative analysis of the mass transport properties of the interstitium [138]. This principle was recently demonstrated by Thompson et al. where the fluid drainage properties of microengineered blind-ended lymphatic vessels embedded within collagen scaffolds were characterized [139]. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the solute drainage rates were greater in collagen gels that contained lymphatic vessels than in those that had bare channels by preventing solute transport back into the scaffold. Therefore, this study represents a significant step in successfully engineering the fluid absorption functions of the initial lymphatics in vitro.

Other in vitro approaches, such as Transwell filter models, have also paved a way for studying interstitial transport properties of lymphatic endothelium in the settings of cancer metastasis and immune systems [140-142]. Similarly, microfluidic systems have been applied to understand how interstitial mass transport is influenced by functional lymphatics. One example in the context of tumor interstitial transport is a tumor-microenvironment-on-a-chip (T-MOC) model that features distinct blood capillary, interstitial, and lymphatic compartments with independent control of fluid pressure [143]. This system demonstrated that the transport of nanoparticles is significantly hindered when IFP is higher than the capillary pressure, thereby replicating a physiological barrier posed by solid tumors that prevents uniform delivery and diminished efficacy of cancer therapeutics [144]. In another study from the same group, the T-MOC model was used to study the differential responses of breast cancer subtypes to doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles [145] (Fig. 4). While these studies demonstrated the influence of cancer drug transport due to passive drainage to lymphatics, recapitulating the active transvascular mechanisms into these systems would both be an impressive technical achievement and augment the physiological relevance of the described microfluidic systems. Future studies that integrate the capabilities of microfluidics to reconstitute distinct tissue compartments while also incorporating independent control of biomechanical and chemical mediators will help further develop strategies for drug delivery in the lymphatic vasculature.

3.4. Limitations

PDMS is the material of choice for microfluidic systems due to its desirable qualities that include ease of fabrication and optical clarity. One advantage of PDMS is the ability to tune the hydrophobic surface properties to become more hydrophilic to improve biocompatibility and biofunctionality using oxygen plasma treatment, surface coating, and silanization [146,147]. However, one important limitation of PDMS is that this material is prone to non-specific absorption of proteins and hydrophobic drug molecules, thereby reducing the effective concentrations delivered to cells [148]. Researchers are addressing this concern using chemical surface modifications [149] or alternative materials [150,151]. While the elastomeric properties of PDMS make it suitable for long-term experimental usage without significant mechanical deformation, the Young’s modulus (a measure of mechanical stiffness) of PDMS is much higher than physiological tissue. The stiffness of PDMS can be modified by adjusting the ratio of basic and curing agent of PDMS which has been shown to regulate cell responses of muscle and nerves [152]. Nonetheless, incorporating natural scaffolds or hydrogels such as collagen or fibrin gels into microfluidic systems can help ensure that the in vitro microtissues that are formed matches the mechanical properties of physiological tissue [153,154]. Recently, 3-D printing of biocompatible polymers has enabled an additive manufacturing approach for constructing in vitro biomimetic scaffolds [155]. Successful integration of established microfabrication techniques with 3-D printing should enable the biofabrication of increasingly more complex lymphatic microenvironments in vitro.

4. Future outlooks

From the lymphatic biologist perspective, the ideal microfluidic device should mimic conditions in living organisms and be easy to assemble. It should also enable the tight control and manipulation of all parameters relevant to lymphatic biology, be scalable to high-throughput analysis, and facilitate the application of standard methods of molecular analysis and live imaging [156]. The immense progress in microfabrication and biological integration has helped bridge this technology gap for organotypic cell-culture studies [6]. Nonetheless, numerous opportunities for technological advancement remain. Microscale culture models are readily amenable for incorporating novel molecular and genetic approaches, force probes, and imaging and detection techniques, which can be cultivated through collaborations with biomedical scientists and physical scientists and engineers. For example, with CRISPR engineered knockout cells becoming commercially available, one can imagine that microfluidic models will help foster the development of more biologically sophisticated disease models for studying lymphatic vessel function. In addition, integration of nanobiosensors into living endothelial cells [19,157] will enable the detection of early-stage molecular signaling and biomechanical mechanisms that mediate lymphatic vessels, which have not yet been fully elucidated, especially at the sub-cellular length scales.

The majority of the studies using microfluidic culture models have so far focused on studying lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic vessel permeability in the context of the initial lymphatic capillaries, with limited insights on the lymphatic pumping mechanisms of the collecting lymphatics invested with perivascular SMCs. This aspect is a notable limitation in lieu of compelling results with isolated lymphatic vessels that demonstrate autoregulatory mechanisms by which fluid is propelled against an adverse pressure gradient [69,158]. Therefore, one could argue that the full pattern of lymphatic vascular remodeling is still beyond the reach of existing microfluidic devices. This outcome is likely a consequence of the “bottom-up” or reductionist approaches that are commonly employed by microfluidic systems that prioritize controlled microenvironments at the expense of biological complexity. However, a possible pathway for microfluidic models to study vascular remodeling of the collecting lymphatic vessels effectively is to adapt a previously described “artery-on-a-chip” platform for probing the role of spatiotemporal heterogeneities in the regulation of small artery tone and function [159]. This platform was developed in response to the wire-myograph method commonly employed by physiologists on isolated lymphatic vessels [160], and allows for loading, precise placement, fixation as well as controlled perfusion and superfusion of a small artery segment. As a result, there may be an opportunity for adapting this microfluidic-based technique for studying structure and function responses of collecting lymphatic vessels in a platform that is scalable for high-throughput with potential for automation and standardization [159]. Moreover, it is known that lymphatic valves frequently form at the bifurcation points of collecting lymphatic vessels [70,161], which correspond to regions of flow separations and disturbances [162]. With the emergence of 3-D microfluidic models featuring branched vessel geometry [14,163,164], these systems may be capable of interrogating the mechanisms of lymphatic valve formation in vitro that is coordinated by local flow dynamics, cell-cell interactions, and ECM remodeling.

In addition, it was previously believed that the brain and central nervous system (CNS) lacked a functional lymphatic system that could aid in immunosurveillance and fluid drainage [165]. However, recent work has revealed that lymphatic vessels do in fact exist in the meninges of the brain [166-168]. These findings have prompted a reassessment of the role of the lymphatic vasculature in the CNS and its involvement in a variety of neuroimmunological disorders. For instance, Kipnis and colleagues showed that meningeal lymphatic vessels play an essential role in draining amyloid-β peptides from cerebrospinal fluids and into cervical lymph node to maintain brain homeostasis [169]. Accumulation of amyloid-β in the brain parenchyma is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease [170]. Therefore, dysfunctional lymphatics in the brain may contribute to Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative disorders. A number of microfluidic blood brain barrier (BBB) models have been developed [171-173]. Thus, with the recent discovery of lymphatic vasculature in the CNS, it is foreseeable that microscale technologies could provide capable and versatile lymphatic-brain analogue systems to serve as neurological disease models.

5. Conclusion

In this review, we, highlight that microfluidic systems are uniquely capable experimental models that are amenable to faithfully recapitulating physicochemical cues of lymphatic microenvironments for quantitatively studying lymphatic barrier function, lymphangiogenesis, and effects of lymphatics on interstitial mass transport. We anticipate that further advancements in microscale culture models will make significant contributions to our mechanistic understanding of lymphatic biology and function to help realize its promise as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular medicine, wound healing, tissue engineering, and oncology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding awarded to J.W.S. from The American Heart Association (15SDG25480000), an NSF CAREER Award (CBET-1752106), The American Cancer Society (IRG-67-003-50), Pelotonia Junior Investigator Award, NHLBI (R01HL141941), and The Ohio State University Materials Research Seed Grant Program, funded by the Center for Emergent Materials, an NSF-MRSEC, grant DMR-1420451, the Center for Exploration of Novel Complex Materials, and the Institute for Materials Research. C.W.C acknowledges funding from the Pelotonia Graduate Fellowship Program. We thank Marcos Cortes-Medina and Alex Avendano for critical review of this manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- ASC

adipose-derived stromal cell

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BEC

blood endothelial cell

- CCBE1

calcium binding EGF domain-containing protein 1

- CNS

central nervous system

- Cx37

connexin 37

- ECIS

Electrical Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensor

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FOXC2

forkhead box protein C2

- HGF

hepatocyte growth factor

- IFP

interstitial fluid pressure

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cell

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

- LSS

laminar shear stress

- LYVE-1

lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- OSS

oscillatory shear stress

- PDGF-B

platelet derived growth factor B

- PDMS

poly(dimethylsiloxane)

- PROX-1

prospero-related homeodomain transcription factor

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- S1P

spingosine-1-phosphate

- SMCs

smooth muscle cells

- T-MOC

tumor-microenvironment-on-a-chip

- TIE

tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 1

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Nowak-Sliwinska P, Alitalo K, Allen E, Anisimov A, Aplin AC, Auerbach R, Augustin HG, Bates DO, van Beijnum JR, Bender RHF, Bergers G, Bikfalvi A, Bischoff J, Bock BC, Brooks PC, Bussolino F, Cakir B, Carmeliet P, Castranova D, Cimpean AM, Cleaver O, Coukos G, Davis GE, De Palma M, Dimberg A, Dings RPM, Djonov V, Dudley AC, Dufton NP, Fendt SM, Ferrara N, Fruttiger M, Fukumura D, Ghesquiere B, Gong Y, Griffin RJ, Harris AL, Hughes CCW, Hultgren NW, Iruela-Arispe ML, Irving M, Jain RK, Kalluri R, Kalucka J, Kerbel RS, Kitajewski J, Klaassen I, Kleinmann HK, Koolwijk P, Kuczynski E, Kwak BR, Marien K, Melero-Martin JM, Munn LL, Nicosia RF, Noel A, Nurro J, Olsson AK, Petrova TV, Pietras K, Pili R, Pollard JW, Post MJ, Quax PHA, Rabinovich GA, Raica M, Randi AM, Ribatti D, Ruegg C, Schlingemann RO, Schulte-Merker S, Smith LEH, Song JW, Stacker SA, Stalin J, Stratman AN, Van de Velde M, van Hinsbergh VWM, Vermeulen PB, Waltenberger J, Weinstein BM, Xin H, Yetkin-Arik B, Yla-Herttuala S, Yoder MC, Griffioen AW. Consensus guidelines for the use and interpretation of angiogenesis assays. Angiogenesis 21: 425–532, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podgrabinska S, Braun P, Velasco P, Kloos B, Pepper MS, Skobe M. Molecular characterization of lymphatic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 16069–16074, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kriehuber E, Breiteneder-Geleff S, Groeger M, Soleiman A, Schoppmann SF, Stingl G, Kerjaschki D, Maurer D. Isolation and characterization of dermal lymphatic and blood endothelial cells reveal stable and functionally specialized cell lineages. J Exp Med 194: 797–808, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerji S, Ni J, Wang SX, Clasper S, Su J, Tammi R, Jones M, Jackson DG. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J Cell Biol 144: 789–801, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breiteneder-Geleff S, Soleiman A, Kowalski H, Horvat R, Amann G, Kriehuber E, Diem K, Weninger W, Tschachler E, Alitalo K, Kerjaschki D. Angiosarcomas express mixed endothelial phenotypes of blood and lymphatic capillaries: podoplanin as a specific marker for lymphatic endothelium. Am J Pathol 154: 385–394, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huh D, Hamilton GA, Ingber DE. From 3D cell culture to organs-on-chips. Trends Cell Biol 21: 745–754, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy DC, McDonald JC, Schueller OJ, Whitesides GM. Rapid Prototyping of Microfluidic Systems in Poly(dimethylsiloxane). Anal Chem 70: 4974–4984, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akbari E, Spychalski GB, Song JW. Microfluidic approaches to the study of angiogenesis and the microcirculation. Microcirculation 24, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moya ML, Hsu YH, Lee AP, Hughes CC, George SC. In vitro perfused human capillary networks. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 19: 730–737, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young EW, Simmons CA. Macro- and microscale fluid flow systems for endothelial cell biology. Lab Chip 10: 143–160, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CW, Cheng YJ, Tu M, Chen YH, Peng CC, Liao WH, Tung YC. A polydimethylsiloxane-polycarbonate hybrid microfluidic device capable of generating perpendicular chemical and oxygen gradients for cell culture studies. Lab Chip 14: 3762–3772, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosadegh B, Huang C, Park JW, Shin HS, Chung BG, Hwang SK, Lee KH, Kim HJ, Brody J, Jeon NL. Generation of stable complex gradients across two-dimensional surfaces and three-dimensional gels. Langmuir 23: 10910–10912, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee SW, Taylor AM, Tu CH, Cribbs DH, Cotman CW, Jeon NL. Patterned cell culture inside microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 5: 102–107, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akbari E, Spychalski GB, Rangharajan KK, Prakash S, Song JW. Flow dynamics control endothelial permeability in a microfluidic vessel bifurcation model. Lab Chip 18: 1084–1093, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. Microvasc Res 71: 185–196, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galie PA, Nguyen DH, Choi CK, Cohen DM, Janmey PA, Chen CS. Fluid shear stress threshold regulates angiogenic sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: 7968–7973, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickerman V, Kamm RD. Mechanism of a flow-gated angiogenesis switch: early signaling events at cell-matrix and cell-cell junctions. Integr Biol-Uk 4: 863–874, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y, Chen J, Craven M, Choi NW, Totorica S, Diaz-Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, Fischbach-Teschl C, Lopez JA, Stroock AD. In vitro microvessels for the study of angiogenesis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 9342–9347, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y, Wang S, Xue X, Xu A, Liao W, Deng A, Dai G, Liu AP, Fu J. Notch signaling in regulating angiogenesis in a 3D biomimetic environment. Lab Chip 17: 1948–1959, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alitalo K The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat Med 17: 1371–1380, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiological reviews 70: 987–1028, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baluk P, Fuxe J, Hashizume H, Romano T, Lashnits E, Butz S, Vestweber D, Corada M, Molendini C, Dejana E, McDonald DM. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med 204: 2349–2362, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendoza E, Schmid-Schonbein GW. A model for mechanics of primary lymphatic valves. J Biomech Eng 125: 407–414, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerli R, Solito R, Weber E, Aglianò M. Specific adhesion molecules bind anchoring filaments and endothelial cells in human skin initial lymphaticsedn, vol. 332001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulte-Merker S, Sabine A, Petrova TV. Lymphatic vascular morphogenesis in development, physiology, and disease. J Cell Biol 193: 607–618, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver G Lymphatic vasculature development. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 35–45, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, Lagutin OV, Lin FJ, Tsai S, Tsai MJ, Samokhvalov IM, Oliver G. Lineage tracing demonstrates the venous origin of the mammalian lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev 21: 2422–2432, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phng LK, Gerhardt H. Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev Cell 16: 196–208, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iruela-Arispe ML, Davis GE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular lumen formation. Dev Cell 16: 222–231, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hynes RO. Cell-matrix adhesion in vascular development. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 5 Suppl 1: 32–40, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiig H, Keskin D, Kalluri R. Interaction between the extracellular matrix and lymphatics: consequences for lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic function. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 29: 645–656, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achen MG, Mann GB, Stacker SA. Targeting lymphangiogenesis to prevent tumour metastasis. Br J Cancer 94: 1355–1360, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joukov V, Pajusola K, Kaipainen A, Chilov D, Lahtinen I, Kukk E, Saksela O, Kalkkinen N, Alitalo K. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. The EMBO Journal 15: 290–298, 1996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makinen T, Jussila L, Veikkola T, Karpanen T, Kettunen MI, Pulkkanen KJ, Kauppinen R, Jackson DG, Kubo H, Nishikawa S, Yla-Herttuala S, Alitalo K. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis with resulting lymphedema in transgenic mice expressing soluble VEGF receptor-3. Nat Med 7: 199–205, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell 140: 460–476, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng W, Aspelund A, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenic factors, mechanisms, and applications. J Clin Invest 124: 878–887, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karkkainen MJ, Ferrell RE, Lawrence EC, Kimak MA, Levinson KL, McTigue MA, Alitalo K, Finegold DN. Missense mutations interfere with VEGFR-3 signalling in primary lymphoedema. Nat Genet 25: 153–159, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Connell FC, Ostergaard P, Carver C, Brice G, Williams N, Mansour S, Mortimer PS, Jeffery S, Lymphoedema C. Analysis of the coding regions of VEGFR3 and VEGFC in Milroy disease and other primary lymphoedemas. Hum Genet 124: 625–631, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Achen MG, Stacker SA. Vascular endothelial growth factor-D: signaling mechanisms, biology, and clinical relevance. Growth Factors 30: 283–296, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davydova N, Harris NC, Roufail S, Paquet-Fifield S, Ishaq M, Streltsov VA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Stacker SA, Achen MG. Differential Receptor Binding and Regulatory Mechanisms for the Lymphangiogenic Growth Factors Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-C and -D. J Biol Chem 291: 27265–27278, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473: 298–307, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coso S, Bovay E, Petrova TV. Pressing the right buttons: signaling in lymphangiogenesis. Blood 123: 2614–2624, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dellinger MT, Meadows SM, Wynne K, Cleaver O, Brekken RA. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 promotes the development of the lymphatic vasculature. PLoS One 8: e74686, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Augustin HG, Young Koh G, Thurston G, Alitalo K. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin–Tie system. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 10: 165, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pham TH, Baluk P, Xu Y, Grigorova I, Bankovich AJ, Pappu R, Coughlin SR, McDonald DM, Schwab SR, Cyster JG. Lymphatic endothelial cell sphingosine kinase activity is required for lymphocyte egress and lymphatic patterning. J Exp Med 207: 17–27, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao R, Ji H, Feng N, Zhang Y, Yang X, Andersson P, Sun Y, Tritsaris K, Hansen AJ, Dissing S, Cao Y. Collaborative interplay between FGF-2 and VEGF-C promotes lymphangiogenesis and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 15894–15899, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuo M, Yamada S, Koizumi K, Sakurai H, Saiki I. Tumour-derived fibroblast growth factor-2 exerts lymphangiogenic effects through Akt/mTOR/p70S6kinase pathway in rat lymphatic endothelial cells. Eur J Cancer 43: 1748–1754, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hogan BM, Bos FL, Bussmann J, Witte M, Chi NC, Duckers HJ, Schulte-Merker S. Ccbe1 is required for embryonic lymphangiogenesis and venous sprouting. Nat Genet 41: 396–398, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bos FL, Caunt M, Peterson-Maduro J, Planas-Paz L, Kowalski J, Karpanen T, van Impel A, Tong R, Ernst JA, Korving J, van Es JH, Lammert E, Duckers HJ, Schulte-Merker S. CCBE1 is essential for mammalian lymphatic vascular development and enhances the lymphangiogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-C in vivo. Circ Res 109: 486–491, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cao R, Bjorndahl MA, Religa P, Clasper S, Garvin S, Galter D, Meister B, Ikomi F, Tritsaris K, Dissing S, Ohhashi T, Jackson DG, Cao Y. PDGF-BB induces intratumoral lymphangiogenesis and promotes lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Cell 6: 333–345, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knezevic L, Schaupper M, Muhleder S, Schimek K, Hasenberg T, Marx U, Priglinger E, Redl H, Holnthoner W. Engineering Blood and Lymphatic Microvascular Networks in Fibrin Matrices. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 5: 25, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibot L, Galbraith T, Kloos B, Das S, Lacroix DA, Auger FA, Skobe M. Cell-based approach for 3D reconstruction of lymphatic capillaries in vitro reveals distinct functions of HGF and VEGF-C in lymphangiogenesis. Biomaterials 78: 129–139, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarbell JM, Demaio L, Zaw MM. Effect of pressure on hydraulic conductivity of endothelial monolayers: role of endothelial cleft shear stress. Journal of applied physiology 87: 261–268, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiig H, Swartz MA. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiological reviews 92: 1005–1060, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swartz MA, Fleury ME. Interstitial flow and its effects in soft tissues. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 9: 229–256, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zamir M, Moore JE Jr., Fujioka H, Gaver DP 3rd. Biofluid mechanics of special organs and the issue of system control. Sixth International Bio-Fluid Mechanics Symposium and Workshop, March 28-30, 2008 Pasadena, California Ann Biomed Eng 38: 1204–1215, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Levick JR, Michel CC. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res 87: 198–210, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chary SR, Jain RK. Direct measurement of interstitial convection and diffusion of albumin in normal and neoplastic tissues by fluorescence photobleaching. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86: 5385–5389, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wiig H, Swartz MA. Interstitial Fluid and Lymph Formation and Transport: Physiological Regulation and Roles in Inflammation and Cancer. 92: 1005–1060, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Helm CL, Fleury ME, Zisch AH, Boschetti F, Swartz MA. Synergy between interstitial flow and VEGF directs capillary morphogenesis in vitro through a gradient amplification mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 15779–15784, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miteva DO, Rutkowski JM, Dixon JB, Kilarski W, Shields JD, Swartz MA. Transmural flow modulates cell and fluid transport functions of lymphatic endothelium. Circ Res 106: 920–931, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zawieja DC. Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphat Res Biol 7: 87–96, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sabine A, Agalarov Y, Maby-El Hajjami H, Jaquet M, Hagerling R, Pollmann C, Bebber D, Pfenniger A, Miura N, Dormond O, Calmes JM, Adams RH, Makinen T, Kiefer F, Kwak BR, Petrova TV. Mechanotransduction, PROX1, and FOXC2 cooperate to control connexin37 and calcineurin during lymphatic-valve formation. Dev Cell 22: 430–445, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sabine A, Bovay E, Demir CS, Kimura W, Jaquet M, Agalarov Y, Zangger N, Scallan JP, Graber W, Gulpinar E, Kwak BR, Makinen T, Martinez-Corral I, Ortega S, Delorenzi M, Kiefer F, Davis MJ, Djonov V, Miura N, Petrova TV. FOXC2 and fluid shear stress stabilize postnatal lymphatic vasculature. J Clin Invest 125: 3861–3877, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cha B, Geng X, Mahamud MR, Fu J, Mukherjee A, Kim Y, Jho EH, Kim TH, Kahn ML, Xia L, Dixon JB, Chen H, Srinivasan RS. Mechanotransduction activates canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling to promote lymphatic vascular patterning and the development of lymphatic and lymphovenous valves. Genes Dev 30: 1454–1469, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sabine A, Saygili Demir C, Petrova TV. Endothelial Cell Responses to Biomechanical Forces in Lymphatic Vessels. Antioxid Redox Signal 25: 451–465, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kunert C, Baish JW, Liao S, Padera TP, Munn LL. Mechanobiological oscillators control lymph flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 10938–10943, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liao S, Cheng G, Conner DA, Huang Y, Kucherlapati RS, Munn LL, Ruddle NH, Jain RK, Fukumura D, Padera TP. Impaired lymphatic contraction associated with immunosuppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 18784–18789, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scallan JP, Davis MJ, Huxley VH. Permeability and contractile responses of collecting lymphatic vessels elicited by atrial and brain natriuretic peptides. J Physiol 591: 5071–5081, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Udan RS, Dickinson ME. The ebb and flow of lymphatic valve formation. Dev Cell 22: 242–243, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norrmen C, Ivanov KI, Cheng J, Zangger N, Delorenzi M, Jaquet M, Miura N, Puolakkainen P, Horsley V, Hu J, Augustin HG, Yla-Herttuala S, Alitalo K, Petrova TV. FOXC2 controls formation and maturation of lymphatic collecting vessels through cooperation with NFATc1. J Cell Biol 185: 439–457, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Srinivasan RS, Oliver G. Prox1 dosage controls the number of lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors and the formation of the lymphovenous valves. Genes Dev 25: 2187–2197, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanady JD, Dellinger MT, Munger SJ, Witte MH, Simon AM. Connexin37 and Connexin43 deficiencies in mice disrupt lymphatic valve development and result in lymphatic disorders including lymphedema and chylothorax. Dev Biol 354: 253–266, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kazenwadel J, Betterman KL, Chong CE, Stokes PH, Lee YK, Secker GA, Agalarov Y, Demir CS, Lawrence DM, Sutton DL, Tabruyn SP, Miura N, Salminen M, Petrova TV, Matthews JM, Hahn CN, Scott HS, Harvey NL. GATA2 is required for lymphatic vessel valve development and maintenance. J Clin Invest 125: 2979–2994, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sweet DT, Jimenez JM, Chang J, Hess PR, Mericko-Ishizuka P, Fu J, Xia L, Davies PF, Kahn ML. Lymph flow regulates collecting lymphatic vessel maturation in vivo. J Clin Invest 125: 2995–3007, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li J, Hou B, Tumova S, Muraki K, Bruns A, Ludlow MJ, Sedo A, Hyman AJ, McKeown L, Young RS, Yuldasheva NY, Majeed Y, Wilson LA, Rode B, Bailey MA, Kim HR, Fu Z, Carter DA, Bilton J, Imrie H, Ajuh P, Dear TN, Cubbon RM, Kearney MT, Prasad RK, Evans PC, Ainscough JF, Beech DJ. Piezo1 integration of vascular architecture with physiological force. Nature 515: 279–282, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nonomura K, Lukacs V, Sweet DT, Goddard LM, Kanie A, Whitwam T, Ranade SS, Fujimori T, Kahn ML, Patapoutian A. Mechanically activated ion channel PIEZO1 is required for lymphatic valve formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: 12817–12822, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jafarnejad M, Cromer WE, Kaunas RR, Zhang SL, Zawieja DC, Moore JE Jr. Measurement of shear stress-mediated intracellular calcium dynamics in human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H697–706, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kassis T, Yarlagadda SC, Kohan AB, Tso P, Breedveld V, Dixon JB. Postprandial lymphatic pump function after a high-fat meal: a characterization of contractility, flow, and viscosity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 310: G776–789, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Breslin JW, Kurtz KM. Lymphatic endothelial cells adapt their barrier function in response to changes in shear stress. Lymphat Res Biol 7: 229–237, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ostrowski MA, Huang NF, Walker TW, Verwijlen T, Poplawski C, Khoo AS, Cooke JP, Fuller GG, Dunn AR. Microvascular endothelial cells migrate upstream and align against the shear stress field created by impinging flow. Biophys J 106: 366–374, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Surya VN, Michalaki E, Huang EY, Fuller GG, Dunn AR. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 regulates the directional migration of lymphatic endothelial cells in response to fluid shear stress. J R Soc Interface 13, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song JW, Daubriac J, Tse JM, Bazou D, Munn LL. RhoA mediates flow-induced endothelial sprouting in a 3-D tissue analogue of angiogenesis. Lab Chip 12: 5000–5006, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Song JW, Munn LL. Fluid forces control endothelial sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 15342–15347, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo R, Janes L, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Alitalo K, Claffey K, Detmar M. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nat Med 7: 192–198, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rutkowski JM, Boardman KC, Swartz MA. Characterization of lymphangiogenesis in a model of adult skin regeneration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1402–1410, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mandriota SJ, Jussila L, Jeltsch M, Compagni A, Baetens D, Prevo R, Banerji S, Huarte J, Montesano R, Jackson DG, Orci L, Alitalo K, Christofori G, Pepper MS. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C-mediated lymphangiogenesis promotes tumour metastasis. EMBO J 20: 672–682, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bruyere F, Melen-Lamalle L, Blacher S, Roland G, Thiry M, Moons L, Frankenne F, Carmeliet P, Alitalo K, Libert C, Sleeman JP, Foidart JM, Noel A. Modeling lymphangiogenesis in a three-dimensional culture system. Nat Methods 5: 431–437, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liao S, Padera TP. Lymphatic function and immune regulation in health and disease. Lymphat Res Biol 11: 136–143, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dixon JB. Mechanisms of chylomicron uptake into lacteals. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1207 Suppl 1: E52–57, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis 3: 5, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jones D, Min W. An overview of lymphatic vessels and their emerging role in cardiovascular disease. Journal of cardiovascular disease research 2: 141–152, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mortimer PS, Rockson SG. New developments in clinical aspects of lymphatic disease. J Clin Invest 124: 915–921, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harvey NL, Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, Johnson NC, Witte MH, Boyd K, Sleeman MW, Oliver G. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet 37: 1072–1081, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harvey NL. The link between lymphatic function and adipose biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1131: 82–88, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rutkowski JM, Markhus CE, Gyenge CC, Alitalo K, Wiig H, Swartz MA. Dermal collagen and lipid deposition correlate with tissue swelling and hydraulic conductivity in murine primary lymphedema. Am J Pathol 176: 1122–1129, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.von der Weid PY, Rehal S, Ferraz JG. Role of the lymphatic system in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 27: 335–341, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ivanov S, Scallan JP, Kim KW, Werth K, Johnson MW, Saunders BT, Wang PL, Kuan EL, Straub AC, Ouhachi M, Weinstein EG, Williams JW, Briseno C, Colonna M, Isakson BE, Gautier EL, Forster R, Davis MJ, Zinselmeyer BH, Randolph GJ. CCR7 and IRF4-dependent dendritic cells regulate lymphatic collecting vessel permeability. J Clin Invest 126: 1581–1591, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scallan JP, Huxley VH. In vivo determination of collecting lymphatic vessel permeability to albumin: a role for lymphatics in exchange. J Physiol 588: 243–254, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ono N, Mizuno R, Ohhashi T. Effective permeability of hydrophilic substances through walls of lymph vessels: roles of endothelial barrier. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1676–1682, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Harney AS, Arwert EN, Entenberg D, Wang Y, Guo P, Qian BZ, Oktay MH, Pollard JW, Jones JG, Condeelis JS. Real-Time Imaging Reveals Local, Transient Vascular Permeability, and Tumor Cell Intravasation Stimulated by TIE2hi Macrophage-Derived VEGFA. Cancer Discov 5: 932–943, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wong KH, Truslow JG, Tien J. The role of cyclic AMP in normalizing the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials 31: 4706–4714, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Price GM, Chrobak KM, Tien J. Effect of cyclic AMP on barrier function of human lymphatic microvascular tubes. Microvasc Res 76: 46–51, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sato M, Sasaki N, Ato M, Hirakawa S, Sato K, Sato K. Microcirculation-on-a-Chip: A Microfluidic Platform for Assaying Blood- and Lymphatic-Vessel Permeability. PLoS One 10: e0137301, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Price GM, Wong KH, Truslow JG, Leung AD, Acharya C, Tien J. Effect of mechanical factors on the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials 31: 6182–6189, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Buchanan CF, Verbridge SS, Vlachos PP, Rylander MN. Flow shear stress regulates endothelial barrier function and expression of angiogenic factors in a 3D microfluidic tumor vascular model. Cell Adh Migr 8: 517–524, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Scallan JP, Hill MA, Davis MJ. Lymphatic vascular integrity is disrupted in type 2 diabetes due to impaired nitric oxide signalling. Cardiovasc Res 107: 89–97, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hirakawa S, Detmar M. New insights into the biology and pathology of the cutaneous lymphatic system. J Dermatol Sci 35: 1–8, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tonnesen MG, Feng X, Clark RA. Angiogenesis in wound healing. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 5: 40–46, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kang S, Lee SP, Kim KE, Kim HZ, Memet S, Koh GY. Toll-like receptor 4 in lymphatic endothelial cells contributes to LPS-induced lymphangiogenesis by chemotactic recruitment of macrophages. Blood 113: 2605–2613, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang Q, Lu Y, Proulx ST, Guo R, Yao Z, Schwarz EM, Boyce BF, Xing L. Increased lymphangiogenesis in joints of mice with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 9: R118, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kataru RP, Jung K, Jang C, Yang H, Schwendener RA, Baik JE, Han SH, Alitalo K, Koh GY. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. 113: 5650–5659, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kholova I, Dragneva G, Cermakova P, Laidinen S, Kaskenpaa N, Hazes T, Cermakova E, Steiner I, Yla-Herttuala S. Lymphatic vasculature is increased in heart valves, ischaemic and inflamed hearts and in cholesterol-rich and calcified atherosclerotic lesions. Eur J Clin Invest 41: 487–497, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vieira JM, Norman S, Villa Del Campo C, Cahill TJ, Barnette DN, Gunadasa-Rohling M, Johnson LA, Greaves DR, Carr CA, Jackson DG, Riley PR. The cardiac lymphatic system stimulates resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 128: 3402–3412, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lopez Gelston CA, Balasubbramanian D, Abouelkheir GR, Lopez AH, Hudson KR, Johnson ER, Muthuchamy M, Mitchell BM, Rutkowski JM. Enhancing Renal Lymphatic Expansion Prevents Hypertension in Mice. Circ Res 122: 1094–1101, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu H, Rahman HNA, Dong Y, Liu X, Lee Y, Wen A, To KH, Xiao L, Birsner AE, Bazinet L, Wong S, Song K, Brophy ML, Mahamud MR, Chang B, Cai X, Pasula S, Kwak S, Yang W, Bischoff J, Xu J, Bielenberg DR, Dixon JB, D’Amato RJ, Srinivasan RS, Chen H. Epsin deficiency promotes lymphangiogenesis through regulation of VEGFR3 degradation in diabetes. J Clin Invest 128: 4025–4043, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liao S, von der Weid P-Y. Inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic dysfunction. Angiogenesis 17: 325–334, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Phillips S, Kapp M, Crowe D, Garces J, Fogo AB, Giannico GA. Endothelial activation, lymphangiogenesis, and humoral rejection of kidney transplants. Hum Pathol 51: 86–95, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Diamond MA, Chan SWS, Zhou X, Glinka Y, Girard E, Yucel Y, Gupta N. Lymphatic vessels identified in failed corneal transplants with neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol: bjophthalmol-2018-312630, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dadras SS, Paul T, Bertoncini J, Brown LF, Muzikansky A, Jackson DG, Ellwanger U, Garbe C, Mihm MC, Detmar M. Tumor lymphangiogenesis: a novel prognostic indicator for cutaneous melanoma metastasis and survival. Am J Pathol 162: 1951–1960, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Skobe M, Hamberg LM, Hawighorst T, Schirner M, Wolf GL, Alitalo K, Detmar M. Concurrent induction of lymphangiogenesis, angiogenesis, and macrophage recruitment by vascular endothelial growth factor-C in melanoma. Am J Pathol 159: 893–903, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Holopainen T, Saharinen P, D’Amico G, Lampinen A, Eklund L, Sormunen R, Anisimov A, Zarkada G, Lohela M, Helotera H, Tammela T, Benjamin LE, Yla-Herttuala S, Leow CC, Koh GY, Alitalo K. Effects of angiopoietin-2-blocking antibody on endothelial cell-cell junctions and lung metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst 104: 461–475, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Patel V, Marsh CA, Dorsam RT, Mikelis CM, Masedunskas A, Amornphimoltham P, Nathan CA, Singh B, Weigert R, Molinolo AA, Gutkind JS. Decreased lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis by mTOR inhibition in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 71: 7103–7112, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhang Z, Helman JI, Li LJ. Lymphangiogenesis, lymphatic endothelial cells and lymphatic metastasis in head and neck cancer--a review of mechanisms. Int J Oral Sci 2: 5–14, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stacker SA, Williams SP, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Fox SB, Achen MG. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic vessel remodelling in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 14: 159–172, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Padera TP, Meijer EF, Munn LL. The Lymphatic System in Disease Processes and Cancer Progression. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 18: 125–158, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mumprecht V, Detmar M. Lymphangiogenesis and cancer metastasis. J Cell Mol Med 13: 1405–1416, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tutunea-Fatan E, Majumder M, Xin X, Lala PK. The role of CCL21/CCR7 chemokine axis in breast cancer-induced lymphangiogenesis. Mol Cancer 14: 35, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sweat RS, Sloas DC, Murfee WL. VEGF-C induces lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in the rat mesentery culture model. Microcirculation 21: 532–540, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Stapor PC, Azimi MS, Ahsan T, Murfee WL. An angiogenesis model for investigating multicellular interactions across intact microvascular networks. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H235–245, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hodges NA, Suarez-Martinez AD, Murfee WL. Understanding angiogenesis during aging: opportunities for discoveries and new models. Journal of applied physiology 125: 1843–1850, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kim S, Chung M, Jeon NL. Three-dimensional biomimetic model to reconstitute sprouting lymphangiogenesis in vitro. Biomaterials 78: 115–128, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Shirure VS, Lezia A, Tao A, Alonzo LF, George SC. Low levels of physiological interstitial flow eliminate morphogen gradients and guide angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 20: 493–504, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]