Abstract

Objective

To determine whether total exposure to penicillin V can be reduced while maintaining adequate clinical efficacy when treating pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci.

Design

Open label, randomised controlled non-inferiority study.

Setting

17 primary healthcare centres in Sweden between September 2015 and February 2018.

Participants

Patients aged 6 years and over with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci and three or four Centor criteria (fever ≥38.5°C, tender lymph nodes, coatings of the tonsils, and absence of cough).

Interventions

Penicillin V 800 mg four times daily for five days (total 16 g) compared with the current recommended dose of 1000 mg three times daily for 10 days (total 30 g).

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome was clinical cure five to seven days after the end of antibiotic treatment. The non-inferiority margin was prespecified to 10 percentage points. Secondary outcomes were bacteriological eradication, time to relief of symptoms, frequency of relapses, complications and new tonsillitis, and patterns of adverse events.

Results

Patients (n=433) were randomly allocated to the five day (n=215) or 10 day (n=218) regimen. Clinical cure in the per protocol population was 89.6% (n=181/202) in the five day group and 93.3% (n=182/195) in the 10 day group (95% confidence interval −9.7 to 2.2). Bacteriological eradication was 80.4% (n=156/194) in the five day group and 90.7% (n=165/182) in the 10 day group. Eight and seven patients had relapses, no patients and four patients had complications, and six and 13 patients had new tonsillitis in the five day and 10 day groups, respectively. Time to relief of symptoms was shorter in the five day group. Adverse events were mainly diarrhoea, nausea, and vulvovaginal disorders; the 10 day group had higher incidence and longer duration of adverse events.

Conclusions

Penicillin V four times daily for five days was non-inferior in clinical outcome to penicillin V three times daily for 10 days in patients with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci. The number of relapses and complications did not differ between the two intervention groups. Five day treatment with penicillin V four times daily might be an alternative to the currently recommended 10 day regimen.

Trial registration

EudraCT 2015-001752-30; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02712307.

Introduction

Sore throat is a common reason for prescribing antibiotics and accounts for about 11% of all antibiotic prescriptions in primary healthcare in Sweden, which is a low prescribing country. Among approximately 29 consultations per 1000 inhabitants for sore throat in 2013, about two thirds were labelled as tonsillitis, of which 80% received an antibiotic prescription.1 Group A streptococcus is the most common pathogen in acute tonsillitis and is present in about 33% of patients with acute sore throat, but other bacteria and viruses are also potential pathogens.2 3 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) Sore Throat Guideline Group and Swedish guidelines for the management of sore throat focus on patients who are more likely to benefit from antimicrobial treatment.2 4 These patients have a higher symptom burden and an infection caused by group A streptococcus. The recommendation is that antibiotic treatment should be offered to patients with three or four Centor criteria (fever, tender cervical lymph nodes, coatings of the tonsils, and lack of cough) and a positive rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus.2 4 5 In Sweden the recommended treatment regimen for adults is 1000 mg penicillin V three times daily for 10 days.4 This duration of treatment is similar to other countries,2 6 7 but the dosage and total exposure (30 g) are relatively high.6 7 8 The historical reason for antimicrobial treatment is mainly to avoid serious complications such as acute rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis.9 These conditions are currently extremely rare in high income countries.9 Today the main reason for treatment in high income countries is to speed up clinical resolution of symptoms,2 but treatment also prevents rare complications such as peritonsillitis, impetigo, cellulitis, otitis media, and sinusitis.10

According to a Cochrane report from 2012, clinical trials on shorter treatment duration with oral penicillin for streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis are encouraged.9 Moore and colleagues (DESCARTE study) called for randomised controlled trials to confirm if a shorter course of penicillin might be sufficient when symptomatic cure is the goal.11 Increasing overall antimicrobial resistance and the lack of new antimicrobial agents emphasise the importance of correctly using existing antibiotics to their full potential.12 13 A Cochrane review published in 2016 concluded that penicillin is the preferred first line treatment for pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococcus in adults and children.14 This review compared penicillin with broader spectrum antibiotics. A meta-analysis from 2008 stated that clinical success and bacteriological eradication are less likely in patients with group A streptococcus pharyngotonsillitis on a short course of treatment (five to seven days) compared with those on a long course of treatment (10 days). The total daily doses in these studies ranged from 750 to 1600 mg, either twice daily or three times daily.15 However, the inclusion criteria did not always follow current ESCMID guidelines, and the dosing regimens were suboptimal according to current knowledge of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

The efficacy of β lactam antibiotics is dependent on time above the minimum inhibitory concentration of the unbound drug concentration in serum. The most important determinants for time above minimum inhibitory concentration are dose and frequency, and the dosing regimen of 800 mg four times daily provides better target attainment compared with 1000 mg three times daily.13 16 The risk with a shorter regimen might be a lower rate of clinical resolution and microbiological eradication.15 However, reducing the treatment duration could cause fewer side effects, improve patient adherence,17 cause less impact on the human microbiota,18 lower the total antibiotic use, and reduce drug costs for patients and the community. The rationale for a non-inferiority trial design was based on the expectation that non-inferiority of the clinical efficacy of a shorter treatment duration compared with the currently recommended treatment would be sufficient from a clinical perspective. The efficacy of 10 day treatment compared with placebo is previously well documented 19 20 21 and in line with international guidelines. The non-inferiority margin for the primary endpoint was agreed upon by the trial steering committee based on European Medicines Agency guidelines 22 and on the judgment that a difference in the rate of clinical cure up to 10 percentage points is not clinically relevant for non-serious infections.

This study was initiated after a governmental assignment to the Public Health Agency of Sweden in 2014 to investigate existing antibiotics. Clinicians and experts performed a review of knowledge gaps followed by a structured prioritisation process to select the most needed clinical studies. The overall objective of this trial was to investigate if the total exposure of penicillin V can be substantially reduced while maintaining adequate clinical efficacy. Our hypothesis was that 800 mg penicillin V given four times daily for five days is non-inferior to the current recommended dose of 1000 mg three times daily for 10 days in patients with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococcus.

Methods

This phase IV, randomised controlled, open label, non-inferiority, multicentre study with two parallel groups compared penicillin V 800 mg four times daily for five days with penicillin V 1000 mg three times daily for 10 days.

Study population and procedures

Consecutive patients with sore throat were assessed for inclusion in the study. Inclusion criteria were patients aged 6 years and over with three or four Centor criteria (fever >38.5°C, tender lymph nodes, coatings of the tonsils (for children inflamed tonsils), and absence of cough), and a positive rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus. These criteria have been used in other studies in which the efficacy of the reference treatment has been established.2 23 The Centor criteria and the rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus are well known to primary care physicians in Sweden and have been used for several years in treatment guidelines. Before the start of the study, we did not provide any additional training about the use of Centor criteria or the rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus. The primary healthcare centres used the same rapid antigen detection test that they used in their normal clinical practice.

Patients were not eligible for inclusion when they showed signs of serious illness or had hypersensitivity to penicillins; when they were receiving immunomodulating treatment corresponding to at least 15 mg prednisolone; when they had received antibiotics for pharyngotonsillitis in the past month (relapse); or when they had received any antibiotic treatment within 72 hours of inclusion. We recruited patients from 17 primary healthcare centres in urban and rural regions of Sweden: Skåne, Kronoberg, Västra Götaland, and Södermanland.

Technical information

Patients or their guardians provided signed informed consent. Patients eligible for inclusion were assigned to treatment with penicillin V as an oral tablet, either 800 mg four times daily for five days or 1000 mg three times daily for 10 days. The dosages for children up to 40 kg were adjusted according to weight (10-20 kg: 250 mg per dose, 20-40 kg: 500 mg per dose, irrespective of treatment arm).24 Physicians prescribed penicillin V and the patients or their guardians obtained the drugs from the pharmacy after the inclusion visit. Patients or their guardians were asked to fill in a patient diary until the test of cure visit, which was scheduled five to seven days after the end of antibiotic treatment. We chose a test of cure visit based on last dose and not a fixed day after randomisation so that the duration without antibiotic protection was similar for both treatment groups.

Physicians’ clinical judgment of throat status at inclusion and at the test of cure visit were recorded. Throat swabs for rapid antigen detection test and culture were performed at study inclusion and at the follow-up visit. To reduce the discomfort for children, we accepted a double swab if rotated against the tonsils. We regarded any growth of group A streptococcus as a positive outcome. A physician recorded adverse events in the case report form at the test of cure visit. Start and stop dates for each event were recorded, and the physician’s assessment of intensity and the relation to the study drug. In addition, patients (or their guardians) self reported adverse events and side effects in the patient diary. Regional study nurses made follow-up telephone calls to patients (or their guardians) one month and three months after completion of antibiotic treatment. Throat symptoms, potential relapses or new tonsillitis, and complications were monitored, in addition to adverse events. When patients had complications, we collected details retrospectively from their medical records. Uppsala Clinical Research Center and the Center for Primary Health Care Research performed monitoring according to International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Good Clinical Practice.

Outcomes

The primary non-inferiority outcome was clinical cure five to seven days after the end of antibiotic treatment at the test of cure visit for the per protocol population. Clinical cure was defined as complete recovery without major residual symptoms or clinical findings of pharyngotonsillitis or symptomatic relapse. Secondary outcomes were bacteriological eradication according to the culture taken at test of cure; frequency of relapses one month after first diagnosis (given clinical cure at test of cure); frequency of complications and new pharyngotonsillitis during the three month study period; and patterns of adverse events. In addition, we used patient diaries to assess time to relief of fever and throat symptoms graded on a Likert scale (no symptoms, mild, moderate, and severe symptoms). We evaluated patients’ adherence to the study drugs in terms of number of doses, and intake of analgesics according to patient diaries as exploratory outcomes.

Changes of outcomes

We performed an additional sensitivity analysis to evaluate the outcome at fixed time points after randomisation. Because the physicians assessed clinical cure only at the test of cure visit, this sensitivity analysis was based on the patient answering “yes” to the question “Do you consider yourself or your child cured from the current infection?” in the patient diary. We performed this analysis at five, seven, and nine days after randomisation.

In June 2017, we also introduced an exploratory outcome at the one month telephone follow-up to examine patients’ preferences about the study medication regimen.

Sample size calculation

We assumed 90% clinical recovery in both groups, a power of 85%, a level of significance of 5%, two sidedness, and a non-inferiority margin of 10%, which gave a sample size of 324 patients. Assuming that the primary outcome could not be evaluated in 25% of patients, 432 needed to be included in the study.

Randomisation

We performed randomisation centrally in advance by using a computerised random number generator within fixed blocks (blinded to the investigators) on a one to one basis and stratified by primary healthcare centres. We concealed allocation by distributing sealed opaque randomisation envelopes to the healthcare centres. The local investigators enrolled participants and assigned them to intervention groups by opening the randomisation envelopes in consecutive order. The allocated treatment regimen was open to participants, investigators, study nurses, and outcome adjudicators. The steering committee agreed definitions of outcome measures to guide the outcome adjudicators before unblinding the two study groups. The steering committee also performed correction of data and made all decisions regarding definitions of analysis populations, variables, and coding of incidences while still blinded to the intervention groups.

Statistical methods

Analysis populations were all randomised patients; the modified intention to treat population, defined as every patient who received at least one dose of study drug; and the per protocol population. The per protocol population included patients who met the inclusion criteria and did not fulfil the exclusion criteria; had no major deviations from the study protocol; had taken at least 80% of the study drug doses; had a test of cure evaluation; and had received no other antibiotics before the test of cure evaluation (except for patients who had treatment failures and early relapses).

We presented categorical variables as numbers and percentages, and tested them with Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were presented, unless stated otherwise, as median, minimum, and maximum, and were tested with the Mann-Whitney U test. The primary efficacy variable, clinical cure, was presented as numbers and percentages, and the risk difference between the two treatment arms was presented with an approximate two sided 95% confidence interval.

We performed the analysis for the primary endpoint on the per protocol population, and this was supplemented by the modified intention to treat population. We presented the secondary, supplementary, and subgroup analyses in a similar manner. Supplementary analyses included the modified intention to treat population with missing values imputed as clinical cure or not clinical cure or without imputation; we excluded patients with only telephone follow-up, patients outside the follow-up visit window, and patients who received oral solution by mistake. We performed subgroup analyses for gender, age (<18 years and ≥18 years), and Centor score 3 and 4 for the primary outcome. We presented time to relief of symptoms (sore throat and fever) by using the Kaplan-Meier method and we tested for differences between the two groups using the log rank test. Data were censored at the first day of symptom free recording. Safety was presented for the modified intention to treat population using descriptive statistics. We set the level of significance to 5%, two sided. We did not perform any adjustments for multiple comparisons because of the limited number of tests. All analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).25

Patient and public involvement

Patients included in the study provided self assessment of symptoms, adverse events, and preference of dose regimen. No patients were involved in setting the research question, nor were they involved in developing plans for recruitment, design, or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. The results will be publicly available on the home page of the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

Results

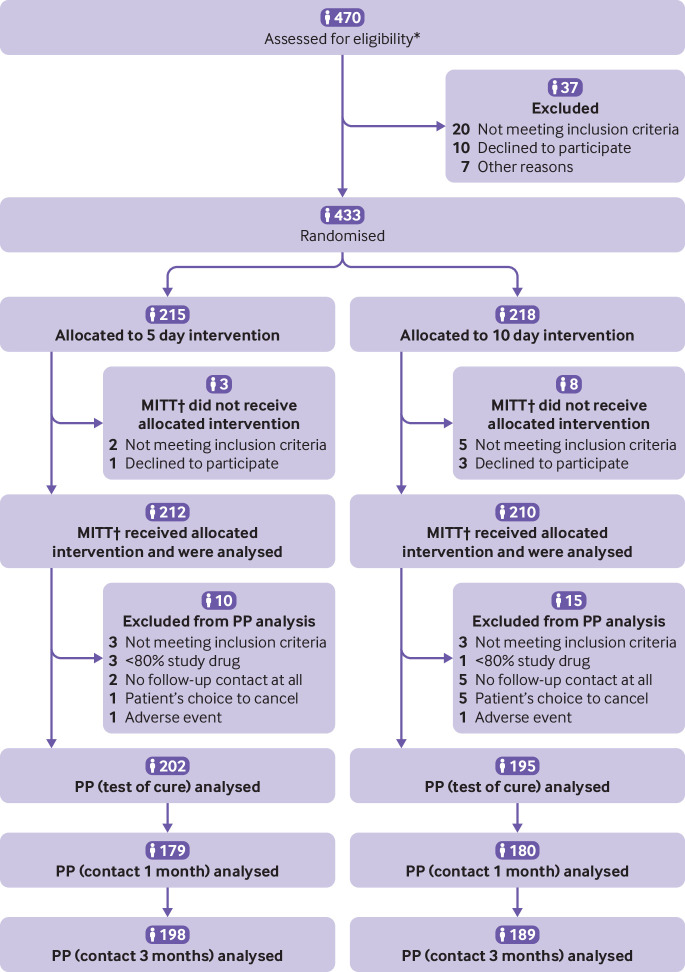

A total of 433 patients were recruited and randomised by 17 primary healthcare centres, with a median of 23 patients (range 1–81) per centre. Patients were recruited between September 2015 and February 2018. The final patient’s last (telephone) follow-up was performed in June 2018. Of the 433 randomised patients, 422 represented the modified intention to treat population and 397 represented the per protocol population. Figure 1 shows the numbers of participants for each intervention group and the reasons for exclusions throughout the study. Demographic and baseline data were comparable between the two intervention groups (table 1).

Fig 1.

Flow diagram according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). *Seven healthcare centres out of 17 filled in a screening list and noted screening failures. †Defined as every patient who received at least one dose of study drug. MITT=modified intention to treat; PP=per protocol

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline data for modified intention to treat population (n=422)* who received five days or 10 days of penicillin V treatment. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | 5 days (n=212) | 10 days (n=210) |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 138 (65.1) | 132 (62.9) |

| Median (range) age (years) | 30.0 (6–73) | 31.0 (3–67) |

| Age group: | ||

| ≤12 | 41 (19.3) | 31 (14.8) |

| 13-17 | 14 (6.6) | 19 (9.0) |

| ≥18 | 157 (74.1) | 160 (76.2) |

| Median (range) weight (kg) | 66.0 (18–116) | 69.5 (12–130) |

| Centor criteria: | ||

| 1-2 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| 3 | 104 (49.1) | 103 (49.0) |

| 4 | 107 (50.5) | 106 (50.5) |

| Fever (≥38.5°C) | 157 (74.1) | 161 (77.0) |

| Tender lymph nodes | 200 (94.3) | 189 (90.9) |

| Coatings of the tonsils | 182 (86.3) | 185 (88.1) |

| Absence of cough | 203 (95.8) | 198 (94.3) |

| Median (range) days of throat pain | 3.0 (1–14) | 3.0 (1–30) |

| Degree of throat pain according to patient: | ||

| Mild | 8 (3.8) | 7 (3.3) |

| Moderate | 79 (37.3) | 81 (38.6) |

| Severe | 125 (59.0) | 122 (58.1) |

| Patient’s general condition: | ||

| Mildly affected | 65 (30.7) | 69 (32.9) |

| Moderately affected | 147 (69.3) | 141 (67.1) |

Includes every patient who received at least one dose of study drug.

Primary outcome

Clinical cure at test of cure evaluation was 89.6% in the five day group (181/202) and 93.3% in the 10 day group (182/195). The study showed that penicillin V 800 mg four times daily for five days was non-inferior to penicillin V 1000 mg three times daily for 10 days in the main analysis population (the per protocol population). The point estimate showed a difference in the rate of clinical cure of −3.7 percentage points (95% confidence interval −9.7 to 2.2) with advantage to the 10 day intervention group. The results of non-inferiority for the five day treatment were supported by supplementary analyses of the modified intention to treat population with imputed values as clinical cure (table 2). We confirmed the results by using supplementary analyses of the modified intention to treat population with imputed values as not clinical cure; and analyses of the per protocol population when we excluded patients with only telephone follow-up (n=14) and patients outside the follow-up visit window (n=17). For two supplementary analyses, modified intention to treat without imputation (n=403) and when patients who received oral solution of penicillin V by mistake (n=7) were excluded, the 95% confidence interval crossed the non-inferiority line (−10.04 to 1.9 and −10.01 to 2.2, respectively). The patients who received oral solution were all clinically cured.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary endpoints for per protocol, modified intention to treat*, and subgroup populations. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Endpoint | 5 days | 10 days | Difference† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint: clinical cure at test of cure: | |||

| PP population (n=397) | 181/202 (89.6) | 182/195 (93.3) | −3.7 (−9.7 to 2.2) |

| MITT population (n=422)‡ | 190/212 (89.6) | 197/210 (93.8) | −4.2 (−9.9 to 1.5) |

| Subgroup analyses: clinical cure at test of cure: | |||

| Men PP (n=142) | 64/72 (88.9) | 66/70 (94.3) | −5.4 (−15.9 to 5.1) |

| Women PP (n=255) | 117/130 (90.0) | 116/125 (92.8) | −2.8 (−10.4 to 4.8) |

| Age <18 years PP (n=101) | 48/53 (90.6) | 46/48 (95.8) | −5.3 (−16.9 to 6.4) |

| Age ≥18 years PP (n=296) | 133/149 (89.3) | 136/147 (92.5) | −3.3 (−10.5 to 4.0) |

| Centor score 3 PP (n=194) | 94/100 (94.0) | 90/94 (95.7) | −1.7 (−9.0 to 5.5) |

| Centor score 4 PP (n=203) | 87/102 (85.3) | 92/101 (91.1) | −5.8 (−15.6 to 4.0) |

| Secondary endpoints (PP): | |||

| Bacteriological eradication at test of cure (n=376) | 156/194 (80.4) | 165/182 (90.7) | −10.2 (−17.8 to −2.7) |

| Relapse within one month (n=359) | 8/179 (4.5) | 7/180 (3.9) | 0.6 (−4.1 to 5.3) |

| Complication by three month follow-up (n=387) | 0/198 (0.0) | 4/189 (2.1) | −2.1 (−4.7 to 0.5) |

| New tonsillitis by three month follow-up (n=386) | 6/197 (3.0) | 13/189 (6.9) | −3.8 (−8.7 to 1.0) |

MITT=modified intention to treat; PP=per protocol.

Includes every patient who received at least one dose of study drug.

5 days−10 days (percentage points).

Missing data (six patients in the five day group and 13 in the 10 day group) imputed as clinical cure.

The sensitivity analysis of the primary endpoint, performed by assessing the patients’ judgment of being cured at five, seven, and nine days after randomisation, showed a faster resolution in the treatment arm with four daily doses compared with patients who received three daily doses (table 3).

Table 3.

Self reported clinical cure according to patient diaries for per protocol population.* Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Self reported clinical cure | 5 days (n=195) | 10 days (n=186) | Difference† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five days after randomisation | 142/164 (86.6) | 112/167 (67.1) | 19.5 (10.1 to 29.0) |

| Missing data | 31 | 19 | — |

| Seven days after randomisation | 122/129 (94.6) | 142/168 (84.5) | 10.0 (2.6 to 17.5) |

| Missing data | 66 | 18 | — |

| Nine days after randomisation | 113/126 (89.7) | 152/167 (91.0) | −1.3 (−8.9 to 6.2) |

| Missing data | 69 | 19 | — |

Based on number of returned diaries (n=381).

5 days−10 days (percentage points).

Results from the subgroup analysis of gender and different age groups did not reveal any differences and were in line with the main analysis population. In patients with Centor score 3, clinical cure differed between the treatment groups by 1.7% (table 2).

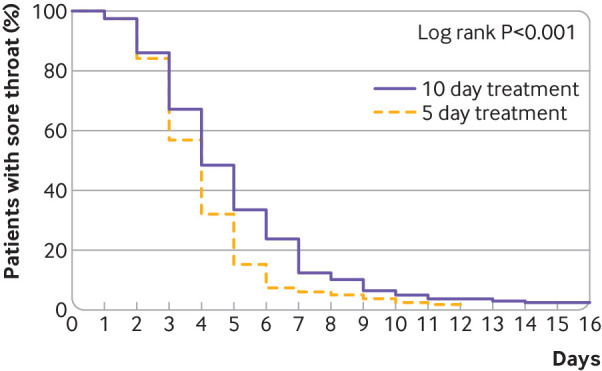

Secondary outcomes

Table 2 shows the results of bacteriological eradication according to the culture taken at the test of cure evaluation (presence of group A streptococcus or not); frequency of relapses one month after first diagnosis; and frequency of complications or new pharyngotonsillitis during the study period. Twelve of the 15 patients who experienced relapses had bacteriological eradication at test of cure, including six out of eight in the five day group and six out of seven in the 10 day group. Only four patients had complications, all in the 10 day group, which all resolved: three were peritonsillitis and one was psoriasis, probably provoked by streptococci. Two of the three patients with peritonsillitis were referred to a specialist for surgery. According to patient diaries, time to first day of relief of sore throat was significantly shorter in the five day group compared with the 10 day group in the per protocol and modified intention to treat populations (P<0.001, log rank test; fig 2). The median time to relief of sore throat was four days after randomisation for both intervention groups. There was no difference between the groups for time to relief of fever recorded in patient diaries (P=0.48, log rank test).

Fig 2.

Time to first day of relief of sore throat according to patient diaries for five day and 10 day groups (per protocol population, n=381)

No serious adverse events were reported during the study. Most of the adverse events recorded on case report forms (assessed by physicians) were judged to be mild or moderate in intensity: 73% (97/132) and 23% (31/132), respectively, in the five day group and 61% (104/170) and 33% (56/170), respectively, in the 10 day group. The adverse events recorded by physicians were mainly diarrhoea, nausea, and vaginal discharge or itching. In all three categories, the 10 day group had higher incidence and longer duration of adverse events (table 4). Self reported adverse events in the patient diary supported the pattern of events recorded by physicians, but with a slightly higher incidence and longer duration of adverse events in both groups (table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse events with possible relation to study drug assessed and registered by physician (modified intention to treat population,* n=422) and self reported from patient diaries (modified intention to treat population,* n=389)†

| Adverse event | 5 days: assessed by physician (n=212) | 5 days: self reported (n=199) | 10 days: assessed by physician (n=210) | 10 days: self reported (n=190) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (%) | Duration (days)‡§ | No (%) | Duration (days)§ | No (%) | Duration (days)‡§ | No (%) | Duration (days)§ | ||||

| Diarrhoea | 34 (16.0) | 2 (2-4) | 51 (25.6) | 2 (1-3) | 44 (21.0) | 3 (2-6) | 66 (34.7) | 2.5 (1-4) | |||

| Nausea or vomiting | 33 (15.6) | 2 (2-4) | 51 (25.6) | 2 (1-3) | 40 (19.0) | 3 (2-5) | 60 (31.6) | 2 (1-4) | |||

| Nausea | 31 (14.6) | 2 (2-4) | — | — | 37 (17.6) | 3 (2-6) | — | — | |||

| Vomiting | 4 (1.9) | — | — | — | 4 (1.9) | — | — | — | |||

| Vaginal itching or discharge¶ | 10 (4.7) | 4 (2-7) | 20 (10.1) | 3 (2-5) | 26 (12.4) | 6 (4-11) | 31 (16.3) | 4 (3-8) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 9 (4.2) | 2 (2-3) | — | — | 6 (2.9) | 3.5 (2-6) | — | — | |||

| Rash | 5 (2.4) | 3 (3-3) | 12 (6.0) | 3 (1-3) | 9 (4.3) | 3 (2-5) | 16 (8.4) | 4 (2-5) | |||

Includes every patient who received at least one dose of study drug.

Adverse events with at least five registrations in physician assessed group or self reported group are presented.

Duration for all reported adverse events; one patient can occur more than once within the same adverse event category. Calculated as stop date minus start date +1. Duration was not calculated for adverse events with missing start or stop dates or if still ongoing at end of study.

Median (interquartile range).

Prevalence of vaginal itching or discharge among women; five day group: 7.2% assessed by physician, 14.5% self reported; 10 day group: 19.7% assessed by physician, 25.4% self reported.

Explorative outcomes

Adherence to the study drug, in terms of number of doses, was high in both groups according to patient diaries, and significantly higher in the five day group. Median adherence was 100% (min-max 65%-100%, interquartile range 1.5%–98.5%) in the five day group (n=199) and 100% (53%-100%, 3.2%–96.8%) in the 10 day group (n=190) (P<0.05). During the telephone follow-up, a proportion of the study patients (n=43 in each treatment group) were asked which of the antibiotic treatments they would prefer if they had the choice. Irrespective of allocated treatment regimen, 63% (54/86) of the patients would prefer to take penicillin V four times a day for five days, and 22% (19/86) would prefer to take the drug three times a day for 10 days. The remaining 15% (13/86) had no preference. According to patient diaries, 84.4% (168/199) of patients in the five day group had taken analgesics for symptom relief for the current infection, with a median duration of 2.0 days (interquartile range 1.0–3.0 days). In the 10 day group the corresponding figures were 83.7% (159/190) with a median duration of 3.0 days (1.0–5.0 days).

Discussion

We found that penicillin V four times daily for five days was non-inferior in clinical outcome to penicillin V three times daily for 10 days in patients with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci. The bacterial eradication rate was lower in the five day treatment group, but the time to symptom resolution was shorter. We did not find any statistically significant difference in the number of relapses within one month between the groups. At the last follow-up there were fewer new pharyngotonsillitis cases and fewer complications reported in the five day treatment group. Additionally, there were fewer adverse events and shorter durations of adverse events reported in the five day group.

Comparison with other studies

Previous studies have compared long treatment regimens with short treatment regimens with the same daily dosage.11 19 20 21 23 26 In this study, we took into account that the efficacy of β lactam antibiotics is dependent on time above the minimum inhibitory concentration. A similar total daily dose but more frequent dosing regimen would give longer time above the minimum inhibitory concentration and would be more aggressive, therefore treatment would not need to be as long.13 Interestingly, the sensitivity analysis at fixed time points after randomisation supports the hypothesis that more frequent dosing favours faster resolution of symptoms. However, this difference between the treatment groups equals out towards the test of cure visit, when both groups have been without antibiotic protection for about a week. Therefore, patients with shorter treatment duration might be at slightly higher risk of having an early relapse and need additional antibiotic treatment. It is important to bear in mind that this sensitivity analysis is based on patients’ self assessment of cure rather than physicians’ clinical judgment at test of cure. Additionally, the five day group diaries had a larger portion of missing data than the 10 day group diaries.

The results from our study support the hypothesis that a dosing regimen of 800 mg four times daily for five days is adequate in the treatment of pharyngotonsillitis diagnosed according to current guidelines. This is in line with a previous observational study that suggested no major differences in outcome among patients aged 16 years and older who received five, seven, or 10 days of treatment with penicillin for sore throat, with doses according to UK guidelines.11 However, our results contradict other studies that state 10 days of antibiotic treatment is superior to shorter treatment regimens.15 Another study from the Netherlands found that seven days of penicillin treatment was superior to three days for pharyngotonsillitis in adults, but they used lower penicillin doses (500 mg three times daily).23 For children with sore throat, no benefits were found for treatment with antibiotics for seven or three days compared with placebo; however, one of the inclusion criteria in that study was only Centor score 2 and there was no test for group A streptococcus.26

The evidence shows that antibiotics only have modest benefits in the treatment of sore throat compared with placebo27 and that three to six days of antibiotic treatment in children with pharyngotonsillitis have been shown to have similar efficacy to 10 days of treatment.9 However, 10 days of penicillin V treatment is still recommended in the current European and American guidelines.2 7 The UK guidelines recommend choosing between five days or 10 days of treatment with penicillin V depending on whether bacterial eradication is regarded as clinically important.6 The results of our study contribute additional support for a shorter treatment duration regardless of scoring systems or diagnostic guidelines. Our finding that patients in the five day treatment arm reported a shorter time to relief of symptoms is in line with our current knowledge in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. This finding is also supported by the fact that duration of analgesic use was shorter in the five day group.

The five day regimen was preferred by patients, and patients in this group showed better adherence than the 10 day group despite the more frequent dose regimen. This finding is supported by a previous study that showed a four dose regimen does not reduce adherence compared with a three dose regimen.17 Fewer patients in the five day treatment group achieved bacterial eradication at the clinical follow up (test of cure), which is in line with previous studies.15 It is not clear whether bacterial eradication has clinical relevance because colonisation of group A streptococcus occurs in healthy people and there is the possibility that patients have coinfections with other potential pathogens and so the causative agent is not known. Notably, the relapse rate within one month was similar in the two groups, and the recurrence rate of new pharyngotonsillitis within three months was lower in the five day treatment group. Overall, these results support the argument for penicillin treatment regimens with more frequent dosing.

It is important to consider whether shorter duration of treatment would be appropriate in general or if certain subgroups in particular would benefit. In our study, subgroup analyses indicated that the rate of clinical cure at five to seven days after the end of penicillin treatment was similar in both treatment groups for patients with three Centor criteria. However, the cure rate in patients with four Centor criteria appeared lower in those receiving the shorter treatment regimen (table 2). This is mirrored by the fact that patients with four Centor criteria had a lower rate of clinical cure. Further research is needed to identify patients who would benefit from a longer treatment regimen.

Despite a slightly higher daily dose of penicillin V in the five day treatment group (3.2 g v 3.0 g in the 10 day treatment), fewer adverse events and shorter duration of adverse events were reported. This finding could be because of shorter exposure to penicillin and might lead to improved adherence if a five day treatment regimen were to be introduced in clinical practice. The four patients who developed complications (three had peritonsillitis and one had psoriasis) were in the 10 day treatment group. We do not know whether complications were avoided in the five day treatment group because of more frequent dosing or whether the three peritonsillitis cases were caused by other infectious agents not treatable with penicillin V. In addition to group A streptococcus, Fusobacterium necrophorum is one of the main agents that causes peritonsillitis.28

The five day treatment almost halved the consumption of antibiotics for this indication, which in theory should cause less effect on the human microbiota.18 29 Shorter exposure time with penicillin might also reduce the risk of developing resistant bacteria, such as pneumococci with non-susceptibility to penicillin, on an individual and community level.30 31 The problem with medicalisation (that is, making people more likely to seek medical care for future illness) should also be weighed against the benefits of treating an otherwise self limiting condition such as uncomplicated pharyngotonsillitis.32

The external validity of the results is considered high because the study had stringent inclusion criteria and included consecutive patients from various regions in a country with a highly developed healthcare system. However, it is important to consider that the results from this study primarily apply to countries where the risk of rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis is low.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study used inclusion criteria in line with current treatment guidelines and dosing regimens according to modern knowledge of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Another strength is that children were included in the study because they are a dominant age group to be treated with antibiotics for respiratory tract infections in primary healthcare.1 33

A limitation of our study is that it was not double blind. Doctors and patients were aware of their treatment arm and so theoretically this could have affected how they reported on the outcome. The risk of performance bias among the clinical assessors was reduced by repeated discussions to agree on common rules on how to evaluate the patients’ clinical status. We selected an open label design for practical reasons owing to the complexity of comparing three doses with four doses using placebo, and also the associated costs; however, a strict randomisation strategy was applied to reduce the risk of selection bias. To ensure that the randomisation envelopes were not opened in advance, regular monitoring visits checked the envelopes were intact. To avoid bias, all cleaning of data was performed on the whole dataset before unblinding the two study groups to the steering committee. As seen in previous studies,10 non-recruitment logs could not be completed by all participating health centres because of time limitations in clinical practice. Another limitation was the lack of information on bacteriological outcome at long term follow-up.

Conclusion

This study showed that penicillin V four times daily for five days was non-inferior in clinical outcome to penicillin V three times daily for 10 days in patients with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci. The number of relapses and complications did not differ between the two intervention groups. Our findings indicate that five days of treatment with penicillin V four times daily might be an alternative to the currently recommended 10 day regimen.

What is already known on this topic

Increasing antibiotic resistance and the shortage of new antimicrobial agents emphasise the importance of optimising the use of existing antibiotics

Pharyngotonsillitis is one of the most common infections in primary healthcare and accounts for a substantial proportion of antibiotic prescribing in Sweden and other European countries

What this study adds

This randomised, open label, multicentre study with non-inferiority design compared a shorter and more frequent treatment regimen with penicillin V to the currently recommended 10 day treatment regimen for pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci

Five days of treatment with penicillin V four times daily was non-inferior in clinical outcome for patients with pharyngotonsillitis caused by group A streptococci and might be an alternative to the currently recommended 10 day regimen

Changing from 10 days to five days of treatment could substantially reduce the total consumption of penicillin V for this indication in countries that follow the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guideline

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients participating in the trial and the study personnel at the participating primary healthcare centres; and the statistician Lina Benson at the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

Participating primary healthcare centres (investigator), regional study nurses and microbiological laboratories: Region Skåne: Löddeköpinge vårdcentral (Anders Wallden); Capio Citykliniken Malmö Limhamn (Ulla Wikström); Sorgenfrimottagningen (Lisa Esbjörnsson Klemendz); Vårdcentralen Lundbergsgatan (Mia Tyrstrup); Vårdcentralen Sjöbo (Mikael Karlsson); Capio Citykliniken Bunkeflo Hyllie (Oskar Smede); regional study nurse Emma Lundström; Labmedicin Skåne. Region Kronoberg: Alvesta vårdcentral (Mattias Rööst); Capio vårdcentralen Hovshaga (Yasir Mahdi); Vårdcentralen Lessebo (Robert Zucconi); Vårdcentralen Strandbjörket (Johanna Sandgren); regional study nurse Catharina Lindqvist; Klinisk mikrobiologi i Växjö.Västra Götalandsregionen: Närhälsan Sandared (Pär-Daniel Sundvall); Närhälsan Fristad (Gudrun Greim); Närhälsan Bollebygd (Helena Kårestedt); Närhälsan Södra Ryd (Karin Rystedt); Närhälsan Billingen (Emma Ottered); Närhälsan Norrmalm (Micael Elmersson); regional study nurse Sofia Sundvall; Klinisk mikrobiologi, Sahlgrenska Universitetssjukhuset and Unilabs AB, Skövde.Region Södermanland: Strängnäs vårdcentral (Per Westberg); Unilabs AB, Eskilstuna.

Contributors: CE, SM, KH, PDS, GSS, CN, and CGG contributed to study conception and design. KH, SM, MT, KR, and PDS acted as investigators or regional investigators and contributed to the acquisition of data. Analysis and interpretation of data was performed by the Public Health Agency of Sweden by CE and GSS in cooperation with KH, MT, PDS, and CN. GSS and MT drafted and contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the work critically for important intellectual content and approval of the final manuscript. KH is the guarantor of the paper. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The study was funded by the Public Health Agency of Sweden. The Healthcare Committee, Region Västra Götaland, funded the salaries for the regional investigator and a doctoral student.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support from the Public Health Agency of Sweden and the Healthcare Committee, Region Västra Götaland for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review board in Lund, 25 June 2015 (reference number 2015/396).

Data sharing: The full trial protocol can be obtained from the authors on request.

The lead author (KH) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Tyrstrup M, Beckman A, Mölstad S, et al. Reduction in antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections in Swedish primary care: a retrospective study of electronic patient records. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:709. 10.1186/s12879-016-2018-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C, et al. ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline Group Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18(Suppl 1):1-28. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hedin K, Bieber L, Lindh M, Sundqvist M. The aetiology of pharyngotonsillitis in adolescents and adults: Fusobacterium necrophorum is commonly found. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:263 e1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medical Products Agency of Sweden The management of pharyngotonsillitis in outpatient care [Handläggning av faryngotonslliter i öppenvård]. Information från Läkemedelsverket 2012;23:18-66. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making 1981;1:239-46. 10.1177/0272989X8100100304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NICE guideline developing group. Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing 2018. nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84

- 7. Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:1279-82. 10.1093/cid/cis847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiappini E, Regoli M, Bonsignori F, et al. Analysis of different recommendations from international guidelines for the management of acute pharyngitis in adults and children. Clin Ther 2011;33:48-58. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Altamimi S, Khalil A, Khalaiwi KA, Milner RA, Pusic MV, Al Othman MA. Short-term late-generation antibiotics versus longer term penicillin for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(8):CD004872. 10.1002/14651858.CD004872.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD, et al. DESCARTE investigators Antibiotic prescription strategies for acute sore throat: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:213-9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70294-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moore M, Stuart B, Hobbs FR, et al. DESCARTE investigators Influence of the duration of penicillin prescriptions on outcomes for acute sore throat in adults: the DESCARTE prospective cohort study in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e623-33. 10.3399/bjgp17X692333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Theuretzbacher U, Van Bambeke F, Cantón R, et al. Reviving old antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:2177-81. 10.1093/jac/dkv157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mouton JW, Ambrose PG, Canton R, et al. Conserving antibiotics for the future: new ways to use old and new drugs from a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic perspective. Drug Resist Updat 2011;14:107-17. 10.1016/j.drup.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Habraken H, Thorning S, Christiaens T. Different antibiotic treatments for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;9:CD004406. 10.1002/14651858.CD004406.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falagas ME, Vouloumanou EK, Matthaiou DK, Kapaskelis AM, Karageorgopoulos DE. Effectiveness and safety of short-course vs long-course antibiotic therapy for group a beta hemolytic streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:880-9. 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60764-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dagan R, Klugman KP, Craig WA, Baquero F. Evidence to support the rationale that bacterial eradication in respiratory tract infection is an important aim of antimicrobial therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001;47:129-40. 10.1093/jac/47.2.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eide TB, Hippe VC, Brekke M. The feasibility of antibiotic dosing four times per day: a prospective observational study in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2012;30:16-20. 10.3109/02813432.2012.654196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sullivan A, Edlund C, Nord CE. Effect of antimicrobial agents on the ecological balance of human microflora. Lancet Infect Dis 2001;1:101-14. 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gerber MA, Randolph MF, Chanatry J, Wright LL, De Meo K, Kaplan EL. Five vs ten days of penicillin V therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis. Am J Dis Child 1987;141:224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schwartz RH, Wientzen RL, Jr, Pedreira F, Feroli EJ, Mella GW, Guandolo VL. Penicillin V for group A streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis. A randomized trial of seven vs ten days’ therapy. JAMA 1981;246:1790-5. 10.1001/jama.1981.03320160022023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strömberg A, Schwan A, Cars O. Five versus ten days treatment of group A streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial with phenoxymethylpenicillin and cefadroxil. Scand J Infect Dis 1988;20:37-46. 10.3109/00365548809117215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on the choice of the non-inferiority margin, EMEA/CPMP/EWP/2158/99. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Zwart S, Sachs AP, Ruijs GJ, Gubbels JW, Hoes AW, de Melker RA. Penicillin for acute sore throat: randomised double blind trial of seven days versus three days treatment or placebo in adults. BMJ 2000;320:150-4. 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Skoog G, Edlund C, Giske CG, et al. A randomized controlled study of 5 and 10 days treatment with phenoxymethylpenicillin for pharyngotonsillitis caused by streptococcus group A - a protocol study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:484. 10.1186/s12879-016-1813-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2018 [Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

- 26. Zwart S, Rovers MM, de Melker RA, Hoes AW. Penicillin for acute sore throat in children: randomised, double blind trial. BMJ 2003;327:1324. 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(11):CD000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klug TE, Henriksen JJ, Fuursted K, Ovesen T. Significant pathogens in peritonsillar abscesses. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;30:619-27. 10.1007/s10096-010-1130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kouyos RD, Metcalf CJ, Birger R, et al. The path of least resistance: aggressive or moderate treatment? Proc Biol Sci 2014;281:20140566. 10.1098/rspb.2014.0566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guillemot D, Carbon C, Balkau B, et al. Low dosage and long treatment duration of beta-lactam: risk factors for carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. JAMA 1998;279:365-70. 10.1001/jama.279.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guillemot D, Varon E, Bernède C, et al. Reduction of antibiotic use in the community reduces the rate of colonization with penicillin G-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:930-8. 10.1086/432721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Warner G, Gantley M, Kinmonth AL. Reattendance and complications in a randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ 1997;315:350-2. 10.1136/bmj.315.7104.350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bou-Antoun S, Costelloe C, Honeyford K, et al. Age-related decline in antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated respiratory tract infections in primary care in England following the introduction of a national financial incentive (the Quality Premium) for health commissioners to reduce use of antibiotics in the community: an interrupted time series analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018;73:2883-92. 10.1093/jac/dky237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]